Abstract

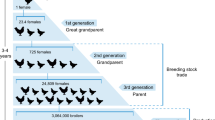

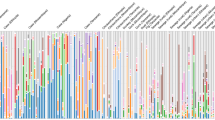

The bacterial accessory genome, comprised of plasmids, phages, and other mobile elements, underpins the adaptability of bacterial populations. Pangenome (core and accessory) analysis of pathogens can reveal epidemiological relatedness missed by using core-genome methods alone. Employing a k-mer-based Jaccard Index approach to compute pangenome relatedness, we explore the population structure and epidemiology of Salmonella enterica serotype Hadar (Hadar), an emerging zoonotic pathogen in the United States (U.S.) linked to both commercial and backyard poultry. A total of 3384 U.S. Hadar genomes collected between 1990 and 2023 are analyzed here. Hadar populations underwent substantial shifts between 2019 and 2020 in the U.S., driven by the expansion of a lineage carrying a previously uncommon prophage-like element. Phylogenetic and pangenomic relatedness, coupled with epidemiological data, suggest this lineage emerged from extant populations circulating in commercial poultry, with subsequent dissemination into backyard poultry environments. We demonstrate the utility of pangenomic approaches for mapping vertical and horizontal diversity and informing complex dynamics of zoonotic bacterial pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that all genomic data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available through NCBI and Enterobase using accession numbers listed within the paper and its supplementary information files available through Figshare. Epidemiological data is available within supplementary information files. Some human patient information collected as part of routine public health surveillance or through supplementary standardized questionnaires are not publicly available due to data privacy laws; deidentified data are available on request by contacting pulsenet@cdc.gov, per data sharing policies. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Arnold, B. J., Huang, I. T. & Hanage, W. P. Horizontal gene transfer and adaptive evolution in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 206–218 (2021).

Jagadeesan, B. et al. The use of next generation sequencing for improving food safety: translation into practice. Food Microbiol 79, 96–115 (2019).

Leeper, M. M. et al. Evaluation of whole and core genome multilocus sequence typing allele schemes for Salmonella enterica outbreak detection in a national surveillance network. PulseNet USA. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1254777 (2023).

Castillo-Ramírez, S. Beyond microbial core genomic epidemiology: towards pan genomic epidemiology. Lancet Microbe 3, e244–e245 (2022).

Liu, C. M. et al. Using source-associated mobile genetic elements to identify zoonotic extraintestinal E. coli infections. One Health 16, 100518 (2023).

Mcnally, A. et al. Combined analysis of variation in core, accessory and regulatory genome regions provides a super-resolution view into the evolution of bacterial populations. PLoS Genet 12, e1006280 (2016).

Guillier, L. et al. AB_SA: accessory genes-based source attribution – tracing the source of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium environmental strains. Microb. Genom. 6, mgen000366 (2020).

Batz, M. B. et al. Recency-weighted statistical modeling approach to attribute illnesses caused by 4 pathogens to food sources using outbreak data, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 214–222 (2021).

Beshearse, E. et al. Attribution of illnesses transmitted by food and water to comprehensive transmission pathways using structured expert judgment, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 182–195 (2021).

Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration. Foodborne illness source attribution estimates for Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157, and Listeria monocytogenes – United States, 2022. GA and D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. (2024).

Commichaux, S. et al. Assessment of plasmids for relating the 2020 Salmonella enterica serovar Newport onion outbreak to farms implicated by the outbreak investigation. BMC Genomics 24, 165 (2023).

Pan, H. et al. Comprehensive assessment of subtyping methods for improved surveillance of foodborne Salmonella. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e02479–02422 (2022).

Peñil-Celis, A. et al. Mobile genetic elements define the non-random structure of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi pangenome. mSystems 9, e0036524 (2024).

Brandenburg, J. M. et al. Salmonella Hadar linked to two distinct transmission vehicles highlights challenges to enteric disease outbreak investigations. Epidemiol. Infect. 152, e86 (2024).

Stapleton, G. S. et al. Multistate outbreaks of salmonellosis linked to contact with backyard poultry-United States, 2015-2022. Zoonoses Public Health 71, 708–722 (2024).

Nichols, M. et al. Salmonella illness outbreaks linked to backyard poultry purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: United States, 2020. Epidemiol. Infect. 149, e234 (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data Summary: Persistent Strain of Salmonella Hadar (REPTDK01) Linked to Backyard Poultry and Ground Turkey. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/php/data-research/reptdk01.html (2024).

The NCBI Pathogen Detection Project [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/(2016).

Fasano, A. et al. Vibrio cholerae produces a second enterotoxin, which affects intestinal tight junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 5242–5246 (1991).

Liu, F., Lee, H., Lan, R. & Zhang, L. Zonula occludens toxins and their prophages in Campylobacter species. Gut Pathog. 8, 43 (2016).

Mahendran, V. et al. Examination of the effects of Campylobacter concisus zonula occludens toxin on intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages. Gut Pathog. 8, 18 (2016).

Di Pierro, M. et al. Zonula occludens toxin structure-function analysis. Identification of the fragment biologically active on tight junctions and of the zonulin receptor binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19160–19165 (2001).

Rathore, A. S., Choudhury, S., Arora, A., Tijare, P. & Raghava, G. P. S. ToxinPred 3.0: an improved method for predicting the toxicity of peptides. Comput. Biol. Med. 179, 108926 (2024).

2016 Salmonella Outbreak Linked to Live Poultry in Backyard Flocks. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/live-poultry-05-16/index.html (2024).

Kaldhone, P. R. et al. Evaluation of incompatibility group I1 (IncI1) plasmid-containing Salmonella enterica and assessment of the plasmids in bacteriocin production and biofilm development. Front. Vet. Sci. 6, 298 (2019).

Foley, S. L., Kaldhone, P. R., Ricke, S. C. & Han, J. Incompatibility group I1 (IncI1) plasmids: their genetics, biology, and public health relevance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 85, e00031–00020 (2021).

Nichols, M. et al. Preventing human Salmonella infections resulting from live poultry contact through interventions at retail stores. J. Agric. Saf. Health 24, 155–166 (2018).

Behravesh, C. B., Brinson, D., Hopkins, B. A. & Gomez, T. M. Backyard poultry flocks and salmonellosis: a recurring, yet preventable public health challenge. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 1432–1438 (2014).

Galán-Relaño, Á et al. Salmonella and salmonellosis: an update on public health implications and control strategies. Animals 13, 3666 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Summary: persistent strain of Salmonella Infantis (REPJFX01) linked to chicken. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/php/data-research/repjfx01.html (2024).

Hassan, R., Buuck, S. & Noveroske, D. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections linked to raw turkey products — United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 68, 1045–1049 (2019).

Ribot, E. M., Freeman, M., Hise, K. B. & Gerner-Smidt, P. PulseNet: entering the age of next-generation sequencing. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 16, 451–456 (2019).

Tolar, B. et al. An overview of PulseNet USA databases. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 16, 457–462 (2019).

Mcmillan, E. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance genes, cassettes, and plasmids present in Salmonella enterica associated with United States food animals. Front. Microbiol. 10, 832 (2019).

Zhou, Z., Alikhan, N. F., Mohamed, K., Fan, Y. & Achtman, M. The EnteroBase user’s guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res 30, 138–152 (2020).

Achtman, M. et al. Genomic diversity of Salmonella enterica -The UoWUCC 10K genomes project [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 5, 223 (2021).

Yoshida, C. E. et al. The Salmonella in silico typing resource (SISTR): an open web-accessible tool for rapidly typing and subtyping draft Salmonella genome assemblies. PLoS One 11, e0147101 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. SeqSero2: Rapid and improved Salmonella serotype determination using whole-genome sequencing data. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e01746–01719 (2019).

Noll, N., Molari, M., Shaw, L. P. & Neher, R. A. PanGraph: scalable bacterial pan-genome graph construction. Microb. Genom. 9, mgen001034 (2023).

Carattoli, A. et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903 (2014).

Garcillán-Barcia, M. P., Redondo-Salvo, S., Vielva, L. & De La Cruz, F. MOBscan: automated annotation of MOB relaxases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2075, 295–308 (2020).

Cury, J., Abby, S. S., Doppelt-Azeroual, O., Néron, B. & Rocha, E. P. C., Identifying conjugative plasmids and integrative conjugative elements with CONJscan., in Horizontal Gene Transfer: Methods and Protocols, F. de la Cruz, Editor. Springer US: New York, NY. 265–283 (2020).

Néron, B., et al. MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes. Peer Commun. J. 3, e28 (2023).

Redondo-Salvo, S. et al. COPLA, a taxonomic classifier of plasmids. BMC Bioinforma. 22, 390 (2021).

Redondo-Salvo, S. et al. Pathways for horizontal gene transfer in bacteria revealed by a global map of their plasmids. Nat. Commun. 11, 3602 (2020).

Schwengers, O. et al. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genom. 7, 000685 (2021).

Bortolaia, V. et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 3491–3500 (2020).

Robertson, J. & Nash, J. H. E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb. Genom. 4, e000206 (2018).

Tagg, K. A. et al. Azithromycin-resistant mph(A)-positive Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi in the United States. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 39, 69–72 (2024).

Li, C. et al. The spread of pESI-mediated extended-spectrum cephalosporin resistance in Salmonella serovars—Infantis, Senftenberg, and Alachua isolated from food animal sources in the United States. PLoS One 19, e0299354 (2024).

Webb, H. E. et al. Genome sequences of 18 Salmonella enterica serotype Hadar strains collected from patients in the United States. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 11, e0052222 (2022).

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. & Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proc. Intern. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 3, 361–362 (2009).

Wang, R. H. et al. PhageScope: a well-annotated bacteriophage database with automatic analyses and visualizations. Nucleic Acids Res 52, D756–D761 (2024).

Wishart, D. S. et al. PHASTEST: faster than PHASTER, better than PHAST. Nucleic Acids Res 51, W443–W450 (2023).

Page, A. J. et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31, 3691–3693 (2015).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Lanza, V. F., Baquero, F., De La Cruz, F. & Coque, T. M. AcCNET (Accessory Genome Constellation Network): comparative genomics software for accessory genome analysis using bipartite networks. Bioinformatics 33, 283–285 (2016).

Bergsma, W. A bias-correction for Cramér’s V and Tschuprow’s. T. J. Korean Stat. Soc. 42, 323–328 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge state and local public health departments and laboratories for isolation and sequencing of Hadar genomes included in this analysis. The authors thank FDA colleagues Olgica Ceric, Beilei Ge, Claudine Kabera, as well as University of Minnesota Professor Timothy Johnson, for their valuable expertise. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Contract No. 75D30123P18303 to FdlC). This work was also supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (PID2020-117923GB-I00 to FdlC and MPGB). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Agencies within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (CDC, FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (FSIS, APHIS), or the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., G.S.S., M.K.S., K.B., M.P.G.B. and F.dlC.–Conceptualization. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., G.S.S., Z.E., M.L., J.Y.K., M.S., C.L., B.H., B.R.M.S., D.M., S.M., K.M., J.H., J.M.W., J.M.B. and K.B.–Data collection. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., G.S.S., M.S., C.L., B.H., B.R.M.S., K.B. and U.D.–Data curation. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., M.K.S., S.R.S., M.P.G.B. and Fdl.C.–Methodology. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., M.K.S., S.R.S., and M.P.G.B.–Analysis. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., M.K.S., S.R.S., M.P.G.B. and Fdl.C.–Visualization. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., G.S.S., K.B., M.P.G.B. and Fdl.C.– Writing - original draft. K.A.T., A.P.C., H.E.W., G.S.S., Z.E., M.L., J.Y.K., M.S., G.T., C.L., B.H., B.R.M.S., M.K.S., D.M., S.M., K.M., J.H., J.M.W., C.S., J.M.B., S.S., K.B., J.P.F., U.D., S.R.S., M.P.G.B. and Fdl.C.–Writing - review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tagg, K.A., Peñil-Celis, A., Webb, H.E. et al. Pangenome dynamics and population structure of the zoonotic pathogen Salmonella enterica serotype Hadar. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68026-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68026-3