Abstract

Underwater tasks such as ocean exploration and emergency rescue demand advanced wearable sensors. However, multifunctional underwater sensors capable of integrating self-powered signal transmission, effective thermal-moisture regulation, and multi-signal decoupling remain unreported. Here, we present a three-dimensional multi-functional thermoelectric device composed of highly porous polyurethane foam coated with a waterproof conductive layer made from single-walled carbon nanotubes, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate, and waterborne polyurethane. Hydrogen bonding between the sulfonate groups in poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate and the -NH groups in waterborne polyurethane enhances water resistance (contact angle of 112°) and mechanical durability under repeated compression (20,000 cycles), while achieving an ultra-fast response time of 40 ms. The device exhibits high breathability (406 mm s−1) owing to its porous three-dimensional architecture. Additionally, it enables precise temperature sensing with a resolution of 0.05 K and a response time of 400 ms. Importantly, it successfully decouples temperature and strain signals in underwater environments. Leveraging its waterproof and signal-decoupling capabilities, we further demonstrate a fully integrated underwater monitoring and interaction system encompassing sensing hardware and decision-making logic. This work represents a significant advancement in wearable underwater electronics and offers another perspective for reliable, real-time human-machine interaction in aquatic settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Underwater exploration plays a vital role in enhancing marine ecosystem understanding, optimizing ocean resource management, and revealing the complexities of aquatic environments. However, the dynamic and unpredictable nature of underwater conditions poses significant risks to divers. To address these challenges, recent breakthroughs in flexible wearable sensor technology for real-time physiological monitoring have provided critical support for safe underwater operations1,2,3,4,5. To prevent accidents and ensure timely, effective responses in emergencies, it is essential to develop flexible wearable sensors capable of continuously and accurately monitoring physiological parameters such as body temperature, motion, and respiration6,7,8,9. These sensors convert external stimuli, such as mechanical forces or temperature changes, into electrical signals for real-time health monitoring. However, most of these devices rely on external power sources or require frequent recharging, which is a major limitation for underwater applications. To overcome this, self-powered technologies based on multi-modal signal fusion have emerged as a key solution10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. By integrating and analyzing tri-modal data (respiration, temperature and motion), these systems enable precise physiological assessments and real-time responses without external power dependency18.

Among self-powered underwater sensors, triboelectric-based sensors have attracted considerable attention for their ability to generate electrical signals by harvesting mechanical energy from environmental stimuli such as pressure and motion19,20,21,22,23. For example, Hou et al. developed a self-powered underwater sensor based on a T-shaped triboelectric nanogenerator capable of simultaneously detecting both normal and tangential forces on submerged objects. Underwater, the sensor demonstrated response times of 50 ms for normal force and 150 ms for tangential force24. Zou et al. introduced a bioinspired stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator for underwater sensing and energy harvesting in human motion monitoring. After more than 50,000 stretching cycles, the device maintained stable output performance, demonstrating good durability and reliability25. However, triboelectric-based sensors often suffer from reduced efficiency and stability in high-humidity environments, necessitating encapsulation. This not only impedes heat and moisture exchange with the body, affecting wearability, but also limits integration with fabrics worn close to the skin. Furthermore, because triboelectric sensors rely on mechanical motion to generate power, they cannot operate continuously underwater without external mechanical input. Additionally, they typically support only single-parameter monitoring, making it difficult to meet the multi-dimensional sensing demands of complex underwater environments.

In contrast, thermoelectric-based sensors can directly convert low-grade waste heat from the human body and surrounding environment into electrical energy, offering a more sustainable and reliable solution for underwater applications26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. For example, Chen et al. developed flexible thermoelectric thin films based on Bi2Te3 that achieved a power factor (S2σ) of 18.5 μW cm−1 K−2 at room temperature, demonstrating high thermoelectric performance37. After 1000 bending cycles, the performance degradation was only about 2%, indicating high reliability and flexibility. Yang’s team fabricated high-performance p-type ultrathin flexible thermoelectric devices with a maximum normalized power density of ~30 μW cm−2 K−2 38. However, most of these studies have focused on improving material-level thermoelectric performance, with limited attention to practical adaptability in real-world scenarios39,40. Moreover, their single-modality sensing capability restricts their potential in multi-dimensional physiological monitoring41. To overcome these limitations, elastic thermoelectric sensors with dual-mode temperature-pressure sensing capabilities have emerged as a promising research direction. These sensors can measure temperature via the Seebeck effect and pressure via the piezoresistive effect, allowing decoupled sensing of both signals42,43,44,45,46,47. For instance, Tian et al. fabricated a layered porous composite aerogel using carbon nanotubes and MXene combined with reinforced cellulose nanofibers, enabling dual-mode thermoelectric-piezoresistive sensing48. Similarly, Chen et al. developed a dual-mode sensor with decoupled thermoelectric and resistive responses using commercial melamine foam49. However, such porous materials tend to absorb water and swell in high-humidity or underwater environments, leading to a reduction in Seebeck coefficient (S). Although hydrophobic coatings (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane, PDMS) can suppress water absorption, they severely reduce breathability and compromise wearing comfort. As a result, applications in underwater environments remain largely unexplored, particularly in terms of practical performance metrics such as multi-modal signal decoupling, wearing comfort, and environmental adaptability. Systematic research in these areas is still lacking.

Here, we propose a thermoelectric polyurethane foam (TEPUF) characterized by waterproof, high elasticity, and a unique ability to decouple temperature and strain sensing. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT: PSS) is used as the core conductive material due to its high electrical conductivity (σ) and environmental stability50. The formation of a hydrogen-bonding network with waterborne polyurethane (WPU) imparts superior waterproof performance (water contact angle of 112°) and enhances the mechanical properties of the highly porous polyurethane foam (PUF) substrate. These features ensure that the thermoelectric device maintains stability over 20,000 compression cycles and exhibits an ultrafast strain response time of 40 ms, even in underwater environments. The device also demonstrates appealing temperature sensing performance, with a resolution of 0.05 K and a response time of 400 ms, enabling accurate, real-time transmission of thermal stimuli. In addition, the three-dimensional (3D) porous structure of the PUF offers high breathability (406 mm s−1), facilitating efficient heat and moisture exchange between the body and the environment. Notably, the decoupling of the Seebeck and piezoresistive effects in the PUF enables the device to maintain stable voltage output even under large deformations of up to 60%. Building on this, we developed a smart glove for underwater interaction by integrating a support vector machine (SVM)-based machine learning model, achieving 100% accuracy in recognizing complex sign language gestures. Furthermore, thermoelectric modules can be embedded in face masks and joints to construct a synergistic monitoring system capable of wirelessly tracking divers’ motion, respiratory rate, and body temperature. These signals are processed via logic circuits, enabling independent sensing and fusion analysis of tri-modal data to provide real-time feedback on a diver’s physiological condition.

Results

To enable multi-modal monitoring of underwater human physiological signals, we developed a wearable underwater monitoring system based on a distributed sensor network. By coordinating the acquisition and fusion of respiratory, body temperature, and motion signals, the system enables comprehensive assessment of physiological states (Fig. 1). Flexible sensor nodes are strategically deployed on key body areas (Fig. 1a) to capture respiratory rate, temperature gradients, and swimming posture, forming a multi-dimensional physiological sensing matrix. We select device placement based on the most suitable body regions for accurately capturing breathing, motion, and body temperature signals. For respiratory monitoring, the device is integrated into the mask to directly interact with airflow and precisely detect breathing rhythms. For motion sensing, devices are positioned at key joints (e.g., knees and wrists) to effectively capture limb movements. For body temperature monitoring, placement on the chest (close to the heart and major blood vessels) enables accurate tracking of core temperature changes. This placement strategy is supported by existing studies, which highlight the importance of sensor positioning in improving signal acquisition quality and enhancing recognition accuracy51,52,53. At the core of this system lies the innovative sensor architecture (Fig. 1b): the TEPUF features a multi-modal decoupling structure achieved through material design and structural engineering, ensuring signal independence, environmental robustness, and user comfort. Specifically, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs)34 and PEDOT: PSS are chosen as thermoelectric fillers, and sulfonate groups on the PSS chains form hydrogen bonds with the -NH groups in WPU to create an interpenetrating network (Figure S1). This design ensures uniform filler dispersion while the hydrophobic chains in WPU provide a barrier effect that contributes to stable waterproofing. TEPUF features a unique 3D porous architecture with high porosity, forming substantial internal static air volume (Figure S2). The presence of axial pores facilitates efficient heat diffusion, contributing to its ultralow thermal conductivity (~0.0445 W m−1 K−1). Under elastic deformation, the pore walls come into contact, increasing conductive pathways and thereby reducing electrical resistance. Thus, the 3D porous PUF substrate overcomes traditional encapsulation limitations, maintaining out-of-plane temperature gradients under high breathability and offering sufficient elasticity for strain sensing, thus enabling physical decoupling of temperature and motion signals. A key breakthrough of this system is its multi-modal signal fusion and alert response mechanism. Inspired by recent advancements in AI-driven multi-modal wearable sensing systems, several notable studies have demonstrated the integration of intelligent algorithms with advanced sensing materials. For example, Kim et al. developed high-performance piezoelectric yarns coupled with a convolutional neural network (CNN) to accurately classify human motion activities in real time51. Similarly, Xu et al. integrated soft, stretchable triboelectric sensors with artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) technology to effectively identify and classify human behaviors and postures52. Thus, to ensure independent processing and accurate transmission of respiration, temperature, and strain signals, we employed a machine learning algorithm to classify, encode, and decode the signals based on distinct physiological states, converting them into identifiable binary outputs (Fig. 1c). Specifically, the original multi-modal signals are first temporally aligned and structured into a unified two-dimensional feature matrix. To eliminate numerical scale differences across different modalities, z-score standardization is applied to all features, ensuring numerical stability and improved convergence efficiency during model training. For the classification model, an SVM with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel is employed due to its effectiveness in handling non-linear data. To optimize model performance, 5-fold cross-validation is used in combination with a grid search across a predefined parameter space to identify the optimal hyperparameter configuration. These binary codes are then input into logic circuits, enabling real-time feedback on the user’s physiological status via an integrated alert system (Fig. 1d). Notably, compared to recently reported wearable multifunctional thermoelectric devices, our TEPUF sets benchmarks in key performance metrics, including waterproofing, breathability (measured at 100 Pa, 25 °C), sensitivity, temperature response time, strain response time, and long-term durability (Fig. 1e)54,55,56,57,58. Furthermore, when compared to state-of-the-art underwater sensing systems, TEPUF demonstrates superior underwater durability, faster response time, and the ability to sense multiple modalities simultaneously (Fig. 1f)59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68.

a Schematic of the underwater wearable monitoring system. b Schematic of the multi-functional sensor array for temperature, pressure, and stimulus decoupling (∆T: temperature difference; ∆P: pressure difference). c Schematic of the multi-modal signal fusion and classification for physiological monitoring. d Schematic of the binary coding and logic element design for signal processing. e Comparison of performance metrics of this work with other wearable multi-functional thermoelectric devices54,55,56,57,58. f Comparison of the response time and stability of this work with other underwater sensing systems59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68.

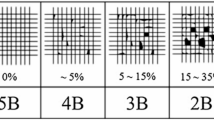

To address the limitations of traditional underwater sensors, such as mechanical brittleness and limited environmental adaptability, the fabricated TEPUF is extremely lightweight, so much so that it can rest atop a foxtail grass plume without bending the delicate strands. Under external pressure, TEPUF also exhibits high resilience, fully recovering its original shape after 90% compression (Fig. 2a), indicating its low density and strong elasticity. Compared to bare PUF, TEPUF shows significantly enhanced compressive strength (Figure S3), attributed to reinforcement from the conductive SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU coating and the high porosity of the PUF matrix. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images reveal that PUF has a 3D porous structure, which facilitates the penetration and adhesion of the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU conductive fillers (Figure S4a). As shown in Figure S4b, the PUF surface becomes rougher after treatment with the conductive solution. This roughness arises from strong chemical compatibility between WPU and the polyurethane-based PUF, allowing for substantial intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces between the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU coating and the PUF framework. These interactions ensure the conductive coating adheres firmly to the PUF skeleton, forming efficient and stable waterproof conductive pathways. These pathways are uniformly coated with the PEDOT layer and SWCNTs network, ultimately forming a robust waterproof conductive network (Figure S4c). As demonstrated in Figure S5, TEPUF can function underwater (in ultrapure water) as a conductive wire to light up a small bulb. The brightness of the bulb increases with applied pressure, indicating TEPUF’s high waterproofing and conductivity. Because air permeability and water resistance in foam materials are typically inversely related, achieving an optimal balance between these properties remains a fundamental challenge in materials design. To address this, we tuned the ratio of WPU to SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS to balance breathability and waterproofing. As shown in Figure S6, the WPU-free sample (0:2) exhibits high air permeability (527 mm s−1 at 100 Pa), but its hydrophilic surface readily absorbs water, making it unsuitable for humid or underwater environments (Figure S7a). In contrast, the thick 2:2 coating provides good waterproofing (Figure S7b) but drastically reduces air permeability to 9.97 mm s−1, compromising wearer comfort and device practicality. The 1:2 WPU:SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS ratio offers the optimal balance, achieving high air permeability (406 mm s−1) and strong water resistance, with a water contact angle of 112°. Furthermore, the water contact angle remains nearly unchanged after 25 min, confirming that the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU coating significantly enhances water resistance (Fig. 2b). Extended water immersion tests further support this: after 8 h of soaking, no detachment of conductive material was observed, and the water contact angle remained stable (Figure S8). In addition to water resistance, TEPUF also resists common liquids such as coffee, milk, tea, and ink (Figure S9). Importantly, TEPUF exhibits high breathability, meeting the requirements for wearable electronics (Fig. 2c).

a Elasticity and lightweight properties of TEPUF. b Water contact angle over time. c Comparison of breathability (PUF: polyurethane foam; SWCNTs: single-walled carbon nanotubes; PEDOT: PSS: poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate; WPU: waterborne polyurethane). d Relative changes in Seebeck coefficient (S) and resistance (R) of TEPUF under different humidity levels (ΔS: S rate of change; S0: initial Seebeck coefficient; ΔR: R rate of change; R0: initial resistance; T0: ambient temperature). e Minimum temperature response curve of TEPUF. f Temperature response time of TEPUF. g Response and recovery times of TEPUF under compressive strain. h Relative changes in S and R of TEPUF after different numbers of compression cycles. i S and R of TEPUF under varying compressive strains. Data shown are mean ± S.E.M. of three independent measurements (n = 3).

In addition to its waterproofing and breathability, TEPUF also exhibits good thermoelectric temperature-sensing capabilities. As shown in Figure S10, under ambient conditions (relative humidity of 60% and ambient temperature (T0) of 24 °C), the temperature difference (ΔT) across the TEPUF displays a linear relationship with the output thermoelectric voltage. From the slope of the fitted curve, the S is calculated to be 38.24 μV K−1, with a high linear correlation of 99.9%. Remarkably, due to its waterproof nature, TEPUF maintains nearly identical thermoelectric performance underwater, with an S value of 35.79 μV K−1. Furthermore, we evaluated the rate of change in S and resistance (R) under varying relative humidity levels (40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%) and in underwater conditions. Remarkably, these variations were negligible (Fig. 2d). After 8 h of water immersion, TEPUF retained a stable S compared to similar materials without WPU, further validating its robust performance (Figure S11). To verify the self-powered temperature sensing ability of TEPUF underwater, a small temperature gradient was applied, producing a thermoelectric voltage of 2.02 μV. From this, the minimum detectable ∆T was determined to be 0.05 K, indicating high temperature resolution (Fig. 2e). The ability of the sensor to recognize temperature signals was further evaluated by applying a series of ∆T values ranging from 0 to 25 K, resulting in a linear voltage increase from 0 to 0.95 mV, highlighting its potential as a self-powered temperature sensor (Figure S12). This was further confirmed by exposing the top surface of TEPUF to hot and cold objects. Contact with a hot object led to a rapid positive thermoelectric voltage response, while contact with a cold object produced a negative response (Figure S13). The device exhibited a fast response time of 400 ms under a ∆T of 3 K, surpassing that of recently reported devices (Fig. 2f). Additionally, under a ∆T of 2 K, TEPUF showed a stable voltage response over a 5000-second cycle (Figure S14), demonstrating considerable durability and reliability for practical applications. To further understand the internal temperature sensing mechanism, we employed finite element analysis (FEA) to visualize the temperature and potential distribution within the sensor (Figure S15). A 3D porous model of TEPUF was constructed based on SEM images, and simulations were performed under ∆Ts of 5, 10, and 15 K. The results showed a proportional increase in output voltage with applied thermal gradients, indicating a strong correlation between ∆T and voltage, and confirming the potential of TEPUF as a high-precision temperature sensor. Importantly, when compared to state-of-the-art thermoelectric temperature sensors, TEPUF demonstrates leading performance in both minimum temperature detection and response time, representing one of the highest-performing thermoelectric devices reported to date (Figure S16)5,54,55,56,57,69,70.

The inherently interconnected porous network of TEPUF endows it with high piezoresistive properties, making it highly promising for underwater wearable monitoring applications. TEPUF exhibits consistent compressive R changes under low humidity, high humidity, and underwater conditions, primarily due to the formation of a robust waterproof conductive network (Figure S17). Water immersion tests further confirm that WPU plays a key role in maintaining stable piezoresistive signals underwater (Figures S18 and S19). We further investigated the underwater piezoresistive performance of TEPUF. As shown in Figure S20, stress-strain curves were obtained under 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% compressive strain. The sensor shows no significant hysteresis or fatigue, retaining high R sensitivity and recovery capability. During dynamic compression and release cycles, the closing and reopening of the porous structure enhance the piezoresistive effect. The deformation process during compression can be divided into three stages: an initial linear stage, where the 3D pores undergo elastic deformation; a gradual transition stage, where larger internal pores begin to collapse; and a final rapid growth stage at high strain, where the structure becomes denser and volume decreases significantly. During compression, the reduction in pore size increases contact areas, forming additional conductive pathways (Figure S21). As a result, the R change confirms that TEPUF exhibits high pressure sensitivity across a wide strain range (20 ~ 80%) (Figure S22). The change in R with strain is typically quantified using the gauge factor (GF), defined as GF = (ΔR/R0) / strain (ΔR: R rate of change; R0: initial resistance). The GF during compression can be categorized into three regions: A, B, and C. When strain exceeds 60%, the GF reaches a peak value of ~1.1, which aligns with the equivalent R model we previously described (Figure S23). Moreover, TEPUF exhibits a fast response and recovery time of just 40 ms and 50 ms, respectively, under large deformation, fully meeting the real-time requirements of wearable devices (Fig. 2g). Mechanical stability and durability are critical metrics for wearable sensors. TEPUF maintains consistent signal intensity regardless of compressive strain or frequency (Figures S24 and S25). To visualize the deformation behavior of TEPUF under external force, we conducted in-situ SEM observations and FEA. The in-situ SEM series captures the complete evolution of the structure from 0% to 80% compression and subsequent unloading (Figure S26). Upon unloading, the structure nearly returns to its original configuration, demonstrating fully reversible deformation. This confirms that TEPUF possesses high elasticity and cyclic stability under repeated compression, with the porous skeleton exhibiting near-complete rebound and recoverability. Consistent with these observations, the FEA results further support TEPUF’s mechanical robustness. The simulated stress distribution map reveals that stress is primarily concentrated along the TEPUF skeleton, particularly at junctions and curved regions, identifying the skeleton as the main load-bearing component. This stress localization within the structural framework contributes to TEPUF’s high structural stability and mechanical resilience. Furthermore, 20,000 underwater compression cycles were conducted to assess long-term fatigue R (see Movie S1). Throughout repeated loading, the sensor retained stable pressure-sensing performance, confirming its durability and long-term reliability for practical applications (Figure S27). Similarly, the σ–ε curves exhibit minimal plastic deformation over repeated cycles, indicating considerable elastic recovery (Figure S28), and the stress-strain response exhibits marked nonlinearity, with low hysteresis loss and high elastic rebound during cyclic compression hallmarks of hyper-elasticity. TEPUF consistently returns to its original shape after repeated loading and effectively withstands cyclic mechanical stress. Figure S29 further shows only a slight decrease in maximum stress over 20,000 cycles. Notably, after 20,000 cycles, the elastic recovery remains as high as 92%, while the energy dissipation coefficient decreases to 0.41. These results highlight TEPUF’s good mechanical performance in underwater environments. Unlike traditional gel-structured materials71,72, TEPUF dissipates energy through intrinsic viscoelastic deformation and the recovery of its porous architecture. Importantly, TEPUF lacks hierarchical interfaces, eliminating the risk of interlayer delamination or failure commonly seen in multilayer systems. Its coherent skeleton provides robust mechanical support, while the continuous porous structure ensures structural uniformity and long-term cyclic stability. Thus, even after 20,000 compression cycles, the R and S of TEPUF remained unchanged, indicating that the 3D porous architecture provides reliable structural support (Fig. 2h). Meanwhile, SEM imaging after 20,000 compression cycles shows that TEPUF retains a clearly visible and well-defined pore network, with no signs of surface or interfacial collapse (Figure S30). The pore spacing remains uniform, and the framework structure is intact, indicating good macroscopic stability after repeated deformation. Microscopic observations further reveal smooth, continuous surfaces without cracks, faults, or localized collapse. These findings confirm the mechanical robustness of the material and validate the effectiveness and practicality of our structural design strategy. To explore the coupling between internal R and output voltage during dynamic operation, we evaluated the S under various compression strains (Fig. 2i). Remarkably, the S remains unaffected by mechanical deformation, which supports further study of thermoelectric voltage and R behavior under dynamic conditions.

To investigate the decoupling capability of TEPUF, we conducted a series of experiments involving both independent and simultaneous stimuli. We examined the electrical response of the sensor under different conditions. First, the baseline current-voltage (I-V) characteristics of TEPUF were recorded (Figure S31a). When mechanical pressure was applied, the 3D porous structure of TEPUF was compressed, reducing the gaps between pores and increasing the contact area of the conductive materials, thereby enhancing internal pathways. According to the modified Ohm’s law (R = ΔV / ΔI) (ΔV: V rate of change; ΔI: I rate of change), this led to a decrease in R and a noticeable shift in the I-V curve (Figure S31b). When a ΔT was applied, the I-V curve shifted to the left without a change in slope, indicating that temperature variation had no effect on the pressure-induced signal output (Figure S31c). Additionally, under a constant ΔT, the thermoelectric voltage output followed S × ΔT, confirming that the internal R of the sensor remained unaffected by temperature changes during thermoelectric voltage generation. Subsequently, when compressive stress was applied again, the I-V curve shifted accordingly, indicating that R changes were solely influenced by mechanical pressure (Figure S31d).

To improve experimental accuracy, we conducted continuous measurements across multiple gradients. Under a fixed ΔT, increasing the applied pressure led to a steeper slope in the I-V curves; however, the curves consistently intersected the origin, indicating that the temperature sensing performance remained stable and unaffected by external pressure (Figure S32). As shown in Figure S33, when the temperature gradient across the sensor varied (−2, 0, 2 K), the I-V curves of the uncompressed TEPUF exhibited horizontal shifts. The x-axis intercepts closely matched the calculated Seebeck voltages (V = S × ΔT), while the slope remained unchanged across ΔT values, confirming stable current output. These results demonstrate that the thermoelectric effect enables precise temperature sensing without interference from pressure-induced current signals. We subsequently subjected TEPUF to a temperature-controlled compression tester in an underwater environment to systematically investigate its behavior under varying pressures and ΔTs (Figure S34). Figure S34a provides a schematic of the experimental setup. As shown in Figure S34b, when ΔT is varied under fixed compressive strains, the relative resistance change (∆R/R0) is primarily governed by mechanical strain, with ΔT having a negligible impact. As a result, the resistance–strain curves at different ΔTs nearly overlap. Conversely, Figure S34c shows that when compressive strain is varied under fixed ΔT, the thermoelectric output voltage increases linearly with ΔT, while remaining largely unaffected by mechanical strain. In addition, we systematically benchmarked device behavior across multiple ΔT magnitudes, from ultra-small to comparatively large, under different compressive strains (Figures S35-S37). Across all ΔT levels, the thermal-electrical pathway and the mechanical response remain decoupled, with no observable cross-talk between thermoelectric output and strain-induced effects. These results clearly demonstrate that the system achieves independent regulation and effective decoupling of thermal and mechanical signals. No observable interference is detected between the thermoelectric voltage and piezoresistive responses. This confirms the system’s capability for precise, dual-channel sensing and highlights its significant advantages in managing complex multi-physical signals in dynamic environments. Overall, these observations confirm that the Seebeck and piezoresistive effects in TEPUF are fully decoupled.

To further demonstrate the decoupling capability of the sensor, we designed a five-stage stimulus sequence (Fig. 3a). In the initial stage, no pressure or ΔT was applied, and both V and R remained stable. In the second stage, pressure was applied without a ΔT, resulting in a significant drop in R while V remained unchanged. In the third stage, both pressure and a ΔT were applied; R continued to decrease, and V increased significantly. In the fourth stage, pressure was reduced while maintaining the ΔT, leading to a sharp increase in R with no change in V. Finally, both pressure and ΔT were gradually removed, returning the R and V to their initial values. This process confirms that TEPUF can simultaneously detect ΔTs and mechanical strain independently. In addition, we simulated the above process using a multi-physics framework (Fig. 3b). The simulation shows that stress propagates primarily along the foam skeleton, with localized concentrations at skeletal junctions, confirming that the skeleton is the main load-bearing structure at the contact interface. These results clarify the mechanical response mechanism, which is jointly influenced by the foam’s geometric deformation and the stiffness of its skeleton. Moreover, under a constant temperature difference, the thermoelectric potential field remains stable despite variations in external pressure. This simulation outcome aligns well with our experimental observations, demonstrating that external pressure has minimal impact on the thermoelectric output. We have also added experimental data and simulation for thermal-mechanical decoupling at the micro-volt level (Figures S38 and S39). The same result was obtained. Furthermore, we conducted additional 2D simulations to obtain a more detailed understanding of the deformation behavior of the foam. The results show that as compressive strain increases, the initially open cells progressively deform into flattened shapes. The pore walls move closer together and eventually press against each other under load, transitioning from an open-cell geometry to a flattened-cell structure at higher strains (Fig. 3c and S40). The pore size decreases continuously with strain, and the simulations indicate that deformation is accommodated primarily through elastic bending of the cell walls rather than permanent collapse, an intrinsic characteristic of the foam hyperelastic response. Even at high strain, the porous scaffold remains intact, enabling the foam to fully recover its original shape upon unloading. This retention of porous structure under substantial compression directly supports the material’s elastic rebound and long-term cyclic durability. In parallel, we performed a voltage-distribution simulation under a temperature difference of ΔT = 12 °C (Fig. 3d and S41). The resulting potential field remains uniform and unchanged even under large compressive strains, confirming that the thermoelectric signal is unaffected by mechanical loading. These combined observations strongly validate the device design principle of decoupling thermal and mechanical signals, ensuring accurate and independent multi-physical sensing. The decoupling performance of TEPUF was further evaluated in practical scenarios. When the device was repeatedly compressed by a heat source, R changed systematically due to the piezoresistive effect (Figure S42), while V increased as expected from the Seebeck effect. This confirms that the two signals in the device are monitored independently without mutual interference. Similarly, when compressed by a cold source, the R exhibited the same trend, but the V decreased accordingly (Figure S43). In summary, TEPUF exhibits good water resistance, dual-mode sensing capabilities, and signal decoupling performance.

a Under simultaneous changes in temperature and pressure. b FEA (finite element analysis) of potential and stress in TEPUF under different ΔTs and compressive strains. c 2D (two-dimensional) FEA of TEPUF stress under different compressive strains. d 2D FEA of the potential of TEPUF at ∆T = 12 °C under different compressive strains.

Underwater resource exploration primarily relies on diving operations. However, in the absence of an effective underwater monitoring system, unforeseen events can pose serious, life-threatening risks, especially when timely intervention is not possible. Recent advances in face-mask technology have introduced innovative materials and design strategies aimed at enhancing both protection and functionality73,74. As shown in Fig. 4a, we developed a device consisting of a 3×3 pixel dual-mode sensor array, which is integrated into the diver’s mask to monitor breathing conditions under various physiological states. One end of the device is positioned near the lips, while the other end is securely attached to the surface of the mask. The end near the lips serves as the sensing region, while the part in contact with the mask acts as a temperature reference. During breathing, airflow induces temperature fluctuations within the device, leading to changes in thermoelectric output voltage. As shown in Figure S44, it is a schematic diagram of this test setup. By analyzing the rate and amplitude of these voltage signals, different breathing states associated with distinct physiological conditions can be identified. Under normal breathing, the voltage signal shows a moderate frequency (12 cycles per min) with minimal fluctuations of about 1.3 mV, indicating a stable physiological state (Figure S45). In contrast, during deep breathing, the frequency decreases (6 cycles per min), and the voltage amplitude nearly doubles to around 2.5 mV (Figure S46). During rapid breathing, the frequency increases (over 20 cycles per min), but the voltage amplitude gradually diminishes, signaling potential hypoxia (Figure S47). Moreover, the device can distinguish between mouth and nasal breathing. When the diver breathes through the nose, the output voltage is relatively low, ~0.4 mV (Figure S48). As shown in Fig. 4b, we quantified the dynamic pressure generated by the breathing airflow. The system supports long-term respiratory monitoring, capturing real-time changes in breathing patterns. Meanwhile, we found that regardless of changes in respiratory status, the resistance remained essentially constant. Furthermore, we performed a wide-range simulation experiment using a ventilator simulator to mimic human respiration at different pressures while simultaneously monitoring the V and R. The results show that at ΔT = 0 K, neither the resistance nor the voltage exhibits any measurable change under varying respiratory pressures (Figure S49). This demonstrates that the mechanical pressure generated during breathing induces only a negligible effect on the resistance response of the device. Therefore, using the voltage signal to monitor respiratory activity is both reliable and robust. Importantly, it also provides early warnings in cases of asphyxia (Figure S50). In such events, the normal fluctuating voltage signal disappears and is replaced by a flat line, which triggers an alert on a connected mobile device. Additionally, by integrating the device into a diver’s chest, real-time body temperature monitoring is enabled. As shown in Fig. 4c, when the ambient temperature changes from ambient temperature (T0 = 25 °C), a corresponding voltage is generated. Using the relation ∆T = ∆V / S, the temperature change and thus the real-time temperature can be calculated. As demonstrated in Fig. 4d, any variation in external temperature leads to a corresponding voltage shift, allowing accurate, real-time temperature monitoring via voltage readout. We also found that, regardless of changes in body temperature, the resistance remained essentially constant. This further confirms the decoupling of temperature and pressure signals in our device. In addition to sensing capabilities, the device also performs well in energy harvesting. When worn on different parts of the body, it generates distinct open-circuit voltages: ~2.24 mV on the wrist (Figure S51a), 1.23 mV on the knee (Figure S51b), and 1.56 mV on the elbow (Figure S51c). These results demonstrate the device’s effectiveness in harvesting body heat and its sensitivity to localized thermal gradients. Moreover, our sensor exhibits high spatial resolution, capable of distinguishing signal intensities across different regions. For small contact areas, pressure signals peak at the center and decay radially, indicating strong central focusing and edge attenuation (Figures S52a and S52c). As the contact area increases, the pressure field becomes more uniform, although edge signals remain slightly lower than those at the center (Figures S52b and S52d). A similar spatial gradient is observed in the temperature maps (Figures S52e and S52f). With a localized heat source, temperature peaks sharply at the center, while surrounding regions show moderate rises. Expanding or shifting the heat source smooths the temperature distribution and reduces edge amplitudes. These findings confirm that our sensor can accurately resolve subtle spatial variations in both pressure and temperature, a capability that is especially critical for high-precision subsea monitoring and wearable applications.

a Schematic diagram of underwater temperature sensing mechanism. b Changes in V and R during long-term respiratory monitoring using devices worn by divers. c Relationship between V and T (temperature) and the change of R under static conditions (ΔT: T rate of change). d Real-time T monitoring and the change of R. e Under different finger bending angles and the change of V (ΔV: V rate of change; V0: initial voltage). f Under different wrist bending angles and the change of V. g Confusion matrix showing 100% recognition accuracy for finger and wrist motion gestures: (Ⅰ) Need to share oxygen, (Ⅱ) Low oxygen, (Ⅲ) Ear pressure imbalance, (Ⅳ) OK, (Ⅴ) UP, (Ⅵ) STOP.

In addition, as a resistive sensor designed for underwater wearable applications, conventional sensors often suffer from signal inaccuracies due to interference from skin contact, water, and temperature fluctuations. However, our TEPUF effectively shields against such interference during R measurements, ensuring robust and reliable performance. To demonstrate its versatility, we designed a multi-functional sensor based on TEPUF (Figure S53). To evaluate its effectiveness in underwater environments, we mounted the sensor on the knee, finger joints, and wrist to accurately distinguish various movement amplitudes via the piezoresistive effect (Figs. S54, 4e, f). Meanwhile, we find that the output voltage remained stable regardless of the movement. Furthermore, we developed a smart glove capable of converting finger motion signals into electronic outputs, enhancing interaction and communication for underwater operators. As shown in Figure S55, compression strain sensors were integrated into the glove’s joints, allowing pressure changes during finger and wrist movements to be captured and transmitted to a personal computer for performance analysis. By integrating signals from multiple points on the hand, the smart glove not only addresses the inherent challenges of underwater interaction but also introduces a remote communication approach. Figure S56 illustrates several complex hand gestures, including need to share oxygen, low oxygen, and ear pressure imbalance. These specific meanings are conveyed through different combinations of finger and wrist movements. The signals collected by the smart glove can be interpreted by analyzing motion patterns of the fingers to decode the intended sign language. To ensure accurate recognition of these gestures, we designed and implemented a machine learning model based on SVM to classify and identify complex sensor signals with high precision. We also developed an SVM-assisted gesture training strategy to improve recognition reliability. Ultimately, the model achieved 100% classification accuracy across multiple independent test datasets (Fig. 4g). This approach demonstrates the effectiveness of TEPUF in minimizing environmental interference and highlights its strong potential for real-time, accurate underwater sensing and communication applications.

To construct a multi-modal underwater risk warning system, we developed an underwater safety monitoring platform based on multi-modal signal fusion, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Leveraging the self-powered, signal-decoupling capabilities of the TEPUF device, the system can simultaneously capture dynamic changes in the diver’s motion, breathing patterns, and body temperature. This enables a comprehensive real-time assessment of physiological conditions and provides early warnings of potential underwater health risks. Ergonomically designed sensor arrays are deployed on the legs and arms to monitor joint deformations, allowing accurate recognition of activity patterns such as freestyle swimming (periodic strain waveforms), treading water (high-frequency, small-amplitude oscillations), and drowning (irregular, intense deformation) (Fig. 5a-c). Additionally, a TEPUF device is positioned inside the diving mask to enable real-time monitoring of various breathing patterns (Fig. 5d). Each type of physical activity affects body heat differently, which is captured through monitoring temperature changes across three stages (up, slow descent, or fast descent) accompanied by consistent voltage responses (Fig. 5e). To distinguish whether this V signal is a thermoelectric signal rather than being affected by the hydrovoltaic effect, we discussed the main influencing factors of the hydrovoltaic effect75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82. The experimental results show that under all test conditions, whether still or dynamic water flow, different humidity, single droplet impact, or seawater, the output voltage of the TEPUF samples is close to baseline levels, with no significant additional potential generation detected (Figures S57-S61). Therefore, we are convinced that our device can accurately capture thermoelectric signals underwater. To integrate and analyze these signals, the collected data is wirelessly transmitted to a computer. An alarm system algorithm then converts the input signals into logical formats, encoding each sensing module (motion, respiration, and temperature) as a two-bit binary signal (Figure S62 and see Table S1 for specific encoding). These binary signals are passed into a custom logic circuit for further processing. To streamline logic circuit design, we first generated intermediate signals for each condition using Boolean algebra, which were then used for subsequent logic combinations (see Table S2). A value of 1 indicates a high signal, and 0 indicates a low signal. Based on these intermediate signals, Karnaugh maps were constructed (Fig. 5f). The output follows this logic: if two or more green signals are received, the output is a green light; if two or more yellow signals are received, the output is a yellow light, and if two or more red signals are received, the output is a red light. Accordingly, we designed a complete circuit diagram (Figure S63). To validate the accuracy of the circuit, we simulated different scenarios. For green-light validation, we mimicked a diver in a safe state performing freestyle swimming with normal breathing. The inputs included two green signals, and the circuit correctly output a green light (Fig. 5g). Conversely, red-light validation simulated a diver entangled in seaweed, showing signs of drowning and respiratory distress. The inputs included two red signals, and the circuit accurately triggered a red light warning (Fig. 5h). This monitoring system offers a critical solution for real-time diver tracking and significantly enhances diver safety by enabling early detection and response to potential hazards during underwater exploration.

R changes caused by leg and arm movements (a) during freestyle swimming, b while treading water, and (c) during a drowning scenario. d Respiratory monitoring. e Body temperature monitoring. f Karnaugh map and corresponding physical display. g Schematic illustration of freestyle swimming. h Schematic illustration of a diver entangled in seaweed.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a TEPUF-based underwater monitoring device, with its core innovation rooted in a material–structure–algorithm co-design strategy that addresses key challenges in underwater sensing, including breathability, washability, and dynamic signal decoupling. Our analysis integrates a multiscale framework with two-dimensional finite-element simulations, which collectively clarify how the material composition and porous architecture synergistically enable the desired structure–property relationships. The incorporation of the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU composite coating allows the device to maintain highly stable electromechanical performance over 20,000 compression cycles, while delivering an ultrafast strain-response time of 40 ms, substantially faster than that of conventional flexible sensors (>100 ms). The thermoelectric component also demonstrates temperature-sensing capability, achieving a detection resolution of 0.05 K and a response time of 400 ms, enabling real-time monitoring of body temperature in dynamic underwater environments. Additionally, the 3D porous PUF structure provides exceptional breathability (406 mm s−1), far exceeding that of traditionally encapsulated sensors, and ensures efficient thermal and moisture exchange between the wearer and the surrounding environment.

Through a physically decoupled design based on the Seebeck and piezoresistive effects, the device can independently output temperature and pressure signals even under high compressive strain, effectively eliminating signal interference caused by underwater dynamic coupling. Building upon this capability, we developed a smart-glove system integrated with a support vector machine (SVM) model, achieving 100% recognition accuracy in underwater gesture-classification tests. Furthermore, a multimodal monitoring platform deployed on face masks and joint regions enables simultaneous measurement of respiratory rate, motion posture, and body temperature. With integrated logic-circuit processing, the system performs tri-modal signal fusion and provides early-warning functionalities to enhance diver safety.

Unlike conventional studies that focus solely on maximizing thermoelectric performance, our approach adopts a usability-first design philosophy. We ensure that the device provides adequate thermoelectric functionality while directly addressing practical challenges (including breathability, washability, and compatibility with complex human motion) through innovative material and structural integration. This work therefore establishes another paradigm for advancing wearable self-powered technologies from laboratory prototypes toward real-world ocean-environment applications.

Methods

Materials

PEDOT: PSS (1.3 wt% dispersed in water, conductive grade) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The SWCNTs dispersion (diameter = 1 ~ 2 nm, dispersed in water) was obtained from Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and anhydrous ethanol (99.5%) were supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (China). Commercial WPU was purchased from Shenzhen Jitian Chemical Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Commercial PUF with 97% porosity was provided by Shenzhen Canghao Industrial Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). All chemicals and materials were used as received without further purification.

Fabrication of TEPUF

First, PEDOT: PSS and DMSO (5 wt%) were added to deionized water and stirred at room temperature for 1 h to prepare the PEDOT: PSS solution. The SWCNTs dispersion was mixed with deionized water at a 2:1 ratio and sonicated for 30 min. The SWCNTs and PEDOT: PSS solutions were then combined and further sonicated for 1 h to ensure uniform dispersion. Subsequently, WPU was added to the mixture in ratios of 0:2, 1:2 and 2:2 respectively, and ultrasonically treated for 20 min to obtain suspensions of SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU in different ratios. Finally, the PUF was immersed in the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU dispersion, sonicated for 30 min, and dried at 80 °C for 1 h to yield the SWCNTs/PEDOT: PSS/WPU@PUF composite (TEPUF).

Fabrication of the TEPUF sensor array

Each TEPUF unit was fabricated as a cylinder with a height of 0.5 cm and a base diameter of 0.3 cm. A total of nine TEPUF blocks with identical dimensions were prepared. To minimize the influence of contact R, two thin copper electrodes (0.2 mm in diameter) were attached to the top and bottom surfaces of each TEPUF using silver adhesive. These TEPUF units were then interconnected to form the complete sensor array.

Characterizations and performance evaluation

The morphology and microstructure of the samples were examined using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Hitachi SU-8010). The water contact angle was characterized by a contact angle measuring instrument (KINO SL200KS). Strain performance was evaluated using a universal testing machine (CTM2050, Xieqiang Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., China). Air permeability was measured with a YG461G automatic fabric air permeability tester. Thermal images of the samples were captured using an infrared camera (Fotric 226, China). Washability tests were conducted by stirring the samples in deionized water at 1000 rpm for various durations. To measure the thermoelectric performance, a semiconductor Peltier module connected to a programmable linear DC power supply (Keysight E3634A) was used to generate different temperature gradients, and the Seebeck voltage was recorded using a DAQ970A data acquisition system (Keysight Technologies). All sensing signals from the devices were collected using a Keithley 2450 source meter. All the tests were conducted in standard laboratories. FEA of the dual-mode temperature-pressure sensing performance of TEPUF was conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 software (see details in Supplementary Information). The tests in this section have obtained the written informed consent of all volunteers.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, D. et al. Multi-heterojunctioned plastics with high thermoelectric figure of merit. Nature 632, 528–535 (2024).

Jia, B. et al. Pseudo-nanostructure and trapped-hole release induce high thermoelectric performance in PbTe. Science 384, 81–86 (2024).

Karthikeyan, V. et al. Three dimensional architected thermoelectric devices with high toughness and power conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 14, 2069 (2023).

Lee, B. et al. High-performance compliant thermoelectric generators with magnetically self-assembled soft heat conductors for self-powered wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5948 (2020).

Zhang, F., Zang, Y., Huang, D., Di, C. -a. & Zhu, D. Flexible and self-powered temperature–pressure dual-parameter sensors using microstructure-frame-supported organic thermoelectric materials. Nat. Commun. 6, 8356 (2015).

Yang, J.-S. et al. Interference-free nanogap pressure sensor array with high spatial resolution for wireless human-machine interfaces applications. Nat. Commun. 16, 2024 (2025).

An, B. W., Heo, S., Ji, S., Bien, F. & Park, J.-U. Transparent and flexible fingerprint sensor array with multiplexed detection of tactile pressure and skin temperature. Nat. Commun. 9, 2458 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Approaching intrinsic dynamics of MXenes hybrid hydrogel for 3D printed multimodal intelligent devices with ultrahigh superelasticity and temperature sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 3420 (2022).

Clevenger, M., Kim, H., Song, H. W., No, K. & Lee, S. Binder-free printed PEDOT wearable sensors on everyday fabrics using oxidative chemical vapor deposition. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj8958 (2021).

Pan, X. et al. Quantifying the interfacial triboelectricity in inorganic-organic composite mechanoluminescent materials. Nat. Commun. 15, 2673 (2024).

Dong, C. et al. High-efficiency super-elastic liquid metal based triboelectric fibers and textiles. Nat. Commun. 11, 3537 (2020).

Li, T. et al. High-performance poly(vinylidene difluoride)/dopamine core/Shell piezoelectric nanofiber and its application for biomedical sensors. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006093 (2021).

Huang, L. et al. Fiber-based energy conversion devices for human-body energy harvesting. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902034 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Fully inkjet-printed Ag2Se flexible thermoelectric devices for sustainable power generation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2141 (2024).

Ding, T. et al. Scalable thermoelectric fibers for multifunctional textile-electronics. Nat. Commun. 11, 6006 (2020).

Yang, C.-Y. et al. A high-conductivity n-type polymeric ink for printed electronics. Nat. Commun. 12, 2354 (2021).

Du, M. et al. A polymer film with very high Seebeck coefficient and overall thermoelectric properties by secondary doping, dedoping engineering and ionic energy filtering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2411815 (2025).

Shi, X.-L., Li, N.-H., Li, M. & Chen, Z.-G. Toward efficient thermoelectric materials and devices: advances, challenges, and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 125, 7525–7724 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. An intelligent self-powered life jacket system integrating multiple triboelectric fiber sensors for drowning rescue. InfoMat 6, e12534 (2024).

Han, X., Che, P., Jiang, L. & Heng, L. Self-powered slippery surface with photo-enhanced triboelectric signal for waterproof wearable sensor. Nano Energy 118, 109026 (2023).

Yang, W. et al. Self-Powered Interactive Fiber Electronics with Visual–Digital Synergies. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104681 (2021).

Dong, K., Peng, X. & Wang, Z. L. Fiber/fabric-based piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators for flexible/stretchable and wearable electronics and artificial intelligence. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902549 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. A perceptual and interactive integration strategy toward telemedicine healthcare based on electroluminescent display and triboelectric sensing 3D stacked device. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402356 (2024).

Hou, Y. et al. Self-powered underwater force sensor based on a T-shaped triboelectric nanogenerator for simultaneous detection of normal and tangential forces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305719 (2023).

Zou, Y. et al. A bionic stretchable nanogenerator for underwater sensing and energy harvesting. Nat. Commun. 10, 2695 (2019).

Shi, X.-L. et al. Advances in flexible inorganic thermoelectrics. EcoEnergy 1, 296–343 (2023).

Chen, Y.-X. et al. Deviceization of high-performance and flexible Ag2Se films for electronic skin and servo rotation angle control. Nat. Commun. 15, 8356 (2024).

He, X. et al. Multifunctional, wearable, and wireless sensing system via thermoelectric fabrics. Engineering 35, 158–167 (2024).

Ding, Z. et al. Ultrafast response and threshold adjustable intelligent thermoelectric systems for next-generation self-powered remote iot fire warning. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 242 (2024).

He, X. et al. Continuous manufacture of stretchable and integratable thermoelectric nanofiber yarn for human body energy harvesting and self-powered motion detection. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 137937 (2022).

Sun, Q., Du, C. & Chen, G. Thermoelectric materials and applications in buildings. Prog. Mater. Sci. 149, 101402 (2025).

Lu, X. et al. Swift assembly of adaptive thermocell arrays for device-level healable and energy-autonomous motion sensors. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 196 (2023).

Wang, L., Moshwan, R., Yuan, N., Chen, Z.-G. & Shi, X.-L. Advances and challenges in SnTe-based thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 37, 2418280 (2025).

Zhou, S. et al. Advances and outlooks for carbon nanotube-based thermoelectric materials and devices. Adv. Mater. 37, 2500947 (2025).

Li, L., Hu, B., Liu, Q., Shi, X.-L. & Chen, Z.-G. High-performance AgSbTe2 thermoelectrics: advances, challenges, and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409275 (2024).

Shi, X.-L. et al. Weavable thermoelectrics: advances, controversies, and future developments. Mater. Futures 3, 012103 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Nanobinders advance screen-printed flexible thermoelectrics. Science 386, 1265–1271 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. Flexible thermoelectrics based on ductile semiconductors. Science 377, 854–858 (2022).

Moshwan, R. et al. Advances and challenges in hybrid photovoltaic-thermoelectric systems for renewable energy. Appl Energ. 380, 125032 (2025).

Liu, Q.-Y. et al. Advances and challenges in inorganic bulk-based flexible thermoelectric devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 150, 101420 (2025).

Shi, X.-L. et al. Advancing flexible thermoelectrics for integrated electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 9254–9305 (2024).

He, X. et al. Layer-by-layer self-assembly of durable, breathable and enhanced performance thermoelectric fabrics for collaborative monitoring of human signal. Chem. Eng. J. 490, 151470 (2024).

Zhu, S. et al. A highly robust, multifunctional, and breathable bicomponent fibers thermoelectric fabric for dual-mode sensing. ACS Sens 9, 5520–5530 (2024).

He, X. et al. Highly stretchable, durable, and breathable thermoelectric fabrics for human body energy harvesting and sensing. Carbon Energy 4, 621–632 (2022).

He, X. et al. Stretchable thermoelectric-based self-powered dual-parameter sensors with decoupled temperature and strain sensing. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 60498–60507 (2021).

He, X. et al. Three-dimensional flexible thermoelectric fabrics for smart wearables. Nat. Commun. 16, 2523 (2025).

Yang, L. et al. Thermoelectric porous laser-induced graphene-based strain-temperature decoupling and self-powered sensing. Nat. Commun. 16, 792 (2025).

Tian, L. et al. High-performance bimodal temperature/pressure tactile sensor based on lamellar CNT/MXene/Cellulose nanofibers aerogel with enhanced multifunctionality. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2418988 (2025).

Chen, Z. et al. Decoupled temperature–pressure sensing system for deep learning assisted human–machine interaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411688 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Achieving high thermoelectric properties in PEDOT:PSS/SWCNTs composite films by a combination of dimethyl sulfoxide doping and NaBH4 dedoping. Carbon 196, 718–726 (2022).

Kim, D. et al. High-performance piezoelectric yarns for artificial intelligence-enabled wearable sensing and classification. EcoMat 5, e12384 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. AIoT-enhanced health management system using soft and stretchable triboelectric sensors for human behavior monitoring. EcoMat 6, e12448 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Muscle-inspired anisotropic aramid nanofibers aerogel exhibiting high-efficiency thermoelectric conversion and precise temperature monitoring for firefighting clothing. Nano-Micro Lett. 17, 214 (2025).

He, Y., Lin, X., Feng, Y., Luo, B. & Liu, M. Carbon nanotube ink dispersed by chitin nanocrystals for thermoelectric converter for self-powering multifunctional wearable electronics. Adv. Sci. 9, 2204675 (2022).

He, X. et al. Waste cotton-derived fiber-based thermoelectric aerogel for wearable and self-powered temperature-compression strain dual-parameter sensing. Engineering 39, 235–243 (2024).

Fu, Y. et al. Ultraflexible temperature-strain dual-sensor based on chalcogenide glass-polymer film for human-machine interaction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313101 (2024).

Cui, Y. et al. Highly stretchable, sensitive, and multifunctional thermoelectric fabric for synergistic-sensing systems of human signal monitoring. Adv. Fiber Mater. 6, 170–180 (2024).

Gao, X.-Z. et al. Self-powered resilient porous sensors with thermoelectric poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) and carbon nanotubes for sensitive temperature and pressure dual-mode sensing. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 14, 43783–43791 (2022).

Shi, P., Wang, Y., Wan, K., Zhang, C. & Liu, T. A waterproof ion-conducting fluorinated elastomer with 6000% stretchability, superior ionic conductivity, and harsh environment tolerance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2112293 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. A structural gel composite enabled robust underwater mechanosensing strategy with high sensitivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201396 (2022).

Ge, D. et al. Mass-producible 3D hair structure-editable silk-based electronic skin for multiscenario signal monitoring and emergency alarming system. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305328 (2023).

Gong, Y. et al. A mechanically robust, self-healing, and adhesive biomimetic camouflage ionic conductor for aquatic environments. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305314 (2023).

Ni, Y. et al. Flexible MXene-based hydrogel enables wearable human–computer interaction for intelligent underwater communication and sensing rescue. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301127 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Fatigue-resistant conducting polymer hydrogels as strain sensor for underwater robotics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305705 (2023).

Jiang, X. et al. Anti-swelling gel wearable sensor based on solvent exchange strategy for underwater communication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2400936 (2024).

Li, A. et al. All-paper-based, flexible, and bio-degradable pressure sensor with high moisture tolerance and breathability through conformally surface coating. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2410762 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Self-powered underwater pressing and position sensing and autonomous object grasping with a porous thermoplastic polyurethane film sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315648 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Yao, A. & Raffa, P. Transparent, highly stretchable, self-healing, adhesive, freezing-tolerant, and swelling-resistant multifunctional hydrogels for underwater motion detection and information transmission. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2407529 (2024).

Li, F. et al. Printable and stretchable temperature-strain dual-sensing nanocomposite with high sensitivity and perfect stimulus discriminability. Nano Lett. 20, 6176–6184 (2020).

Park, H. et al. Microporous polypyrrole-coated graphene foam for high-performance multifunctional sensors and flexible supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1707013 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. A universal interfacial strategy enabling ultra-robust gel hybrids for extreme epidermal bio-monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301117 (2023).

Wang, G. et al. Supramolecular zwitterionic hydrogels for information encryption, soft electronics and energy storage at icy temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater, 35, 2505048 (2025).

Xiao, R., Yu, G., Xu, B. B., Wang, N. & Liu, X. Fiber Surface/Interfacial Engineering on Wearable Electronics. Small 17, 2102903 (2021).

Deng, W. et al. Masks for COVID-19. Adv. Sci. 9, 2102189 (2022).

Yin, J., Zhang, Z., Li, X., Zhou, J. & Guo, W. Harvesting Energy from Water Flow over Graphene? Nano Lett. 12, 1736–1741 (2012).

Zhang, Z. et al. Emerging hydrovoltaic technology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1109–1119 (2018).

Yin, J., Zhou, J., Fang, S. & Guo, W. Hydrovoltaic energy on the way. Joule 4, 1852–1855 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Sparking potential over 1200 V by a falling water droplet. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi2993 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Hydrovoltaic energy from water droplets: device configurations, mechanisms, and applications. Droplet 2, e77 (2023).

Hu, T., Zhang, K., Deng, W. & Guo, W. Hydrovoltaic effects from mechanical–electric coupling at the water–solid interface. ACS Nano 18, 23912–23940 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Hybrid hydrovoltaic electricity generation driven by water evaporation. Nano Res Energy 3, e9120110 (2024).

Deng, W. et al. Collective electricity generation over the kilovolt level from water droplets. Nano Lett. 25, 7457–7464 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232023A-05), the grant (52373069) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Chang Jiang Scholars Program. This work was financially supported by the Australian Research Council, HBIS-UQ Innovation Centre for Sustainable Steel project, and QUT Capacity Building Professor Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-G. C., X.H. Q. and L.M. W. supervised the project and conceived the idea. W.D. L., X.-L. S. and X.Y. H. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. W.D. L. and S.Y. Z. performed the sample preparation, structural characterization, and thermoelectric property measurements. W.D. L., Z. L. and C.Z. L. conducted the finite element simulations and machine learning computation. W.D. L., M. L., X.Y. W., D. Z. and H.N. Z. analyzed the data. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ben Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Shi, XL., He, X. et al. A waterproof and ultra-elastic thermoelectric foam for underwater human signal detection. Nat Commun 17, 1294 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68055-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68055-y