Abstract

With increasingly stringent application environments, there is a growing demand for designing and fabricating of promising structural materials. Conventional metallurgical methods typically struggle to produce positive mixing enthalpy alloys with uniform microstructures and consistent properties due to mutual immiscibility and uncontrollable segregation during solidification. To this end, we employ a bottom-up approach to fabricate Cu-50 vol% Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 positive mixing enthalpy composites, utilizing ultrafast high-temperature sintering and instantaneous quenching. The method effectively prevents liquid segregation during the molten state and allows precise control over the size and distribution of the two phases. In addition, incorporated metallic glass particles as the hard phase additives, which can quickly form the localized multi-phase nanocrystals and establish a robust interlocking structure with pure copper during rapid sintering. Upon rapid quenching, the two phases solidify with a tight and conformal interface, while the elemental cross-diffusion and phase separation are mitigated. The mechanical tensile strength of the resulting composite is approximately 8 times greater than that of pure Cu. The wear resistance improves by 40-50 times, and the Vickers hardness increases by a factor of 10. The innovative sintering method provides a feasible pathway for developing and manufacturing of positive mixing enthalpy composite materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For thousands of years, traditional alloy design and development have primarily focused on systems with negative mixing enthalpy1,2. Expanding the compositional range of positive mixing enthalpy alloy systems and controlling the microstructural arrangement of different phases could lead to the development of materials with characteristics previously unseen in alloy materials, offering immense potential3,4. Unlike negative mixing enthalpy alloy systems, which can easily achieve highly uniform solid solution structures5,6,7, positive mixing enthalpy systems face inherent challenges8,9. Due to the immiscibility of metals in the liquid phase and the prolonged heat treatment durations of conventional metallurgical methods, such as suction casting10, vacuum hot pressing11, high-pressure torsion12, or mechanical repetitive rolling13, the resulting positive mixing enthalpy systems tend to have severe phase separation and poor mechanical properties. Moreover, the temperature-dependent thermodynamic driving forces induce variations in elemental segregation kinetics, leading to uncontrolled heterogeneous microstructures of immiscible phases due to the instability of phase separation dynamics14,15. Despite decades of research, precisely controlling elemental segregation to achieve a uniformly distributed biphasic structure remains an unsolved challenge16,17.

To address this issue, introducing intermediate elements has become a widely adopted strategy for inducing stable solid solutions18,19. For instance, adding a third component (e.g., Ni or Co) can reduce the overall mixing enthalpy or stabilize metastable phases, leading to greater elemental mixing and reduced segregation20,21. Nevertheless, the strategy necessitates precise regulation of alloying element stoichiometry and spatial distribution, concurrent maintenance of thermodynamic equilibrium, and interfacial stability across multiphase systems. Alternatively, multiscale structural design and hierarchical heat treatment have also been employed in developing metals with positive mixing enthalpy22. Recent studies, however, have been limited to adding small amounts of positive mixing enthalpy elements (<0.5%) to either promote the precipitation of coherent nanophases (typically confined to phase diagram edges5,6) or form limited solid solutions23,24. While hypoeutectic doping leverages metastable phase diagrams to confine positive-enthalpy elements at grain boundaries, such compositional constraints inherently limit bulk-scale property engineering25,26.

Given these constraints, we herein employ a bottom-up fabrication strategy for positive mixing enthalpy alloys, incorporating precise microstructure regulation to suppress high-temperature phase segregation. Based on the ultrafast high-temperature sintering (UHS) technology27,28, we have introduced an ultrafast cooling system to enable rapid quenching during the final stage of sintering, achieving ultrahigh-temperature rapid sintering and quenching (UHSQ) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Movie 1). Combining ultrahigh heating and quenching rates ensures a stable and controllable liquid-phase window in positive mixing enthalpy systems (Fig. 1a). This approach retains the high heating rate (500–1000 K/s) of the UHS process while providing an enhanced cooling rate (up to 1000 K/s at the sample surface; see Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Movie 2). Specifically, the precursor compact was wrapped in zirconia (ZrO₂) fiber cloth for electrical insulation (Supplementary Fig. 1c), positioned between two carbon felts in an argon atmosphere, rapidly sintered for 10 seconds, and then immediately quenched in high thermal conductivity silicone oil at 243 K (Fig. 1c). Employing the UHSQ technique, we successfully sintered a Cu-50 vol% Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 positive mixing enthalpy composite, denoted as Cu-Fe-based composite. Concurrent ultrafast quenching (~1 s) induces three critical microstructural evolutions: atomic-scale heterogeneity redistribution in metallic glass; dislocation substructure modification in copper; and nanoscale rivet-like interlocking at interfaces arising from differential thermal contraction coefficients. Due to differences in thermal shrinkage coefficient at the closely attached interface, a nanoscale interlocking rivet-like structure is formed, resulting in a highly robust interface (Fig. 1d). The sequential stages of UHSQ processing—including precursor assembly, Joule heating sintering and quenching—are visually documented in Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3. Metallic glasses demonstrate distinct thermal response across their glass transition temperature (Tg): Below Tg, they exhibit the rigidity of crystalline solids while retaining structural metastability; above Tg, viscous flow initiates until crystallization occurs, resulting in the restoration of rigidity29. This complex phase transition behavior enables effective coupling with positive-enthalpy materials when sintering parameters (temperature/time) are precisely regulated. Crucially, at elevated temperatures above Tg, metallic glasses become supercooled liquids with increased fluidity that facilitates interfacial contact30,31. Implementing the paradigm, we fabricated Cu-Fe-based composites (Fig. 1f) with submicron-scale elemental homogeneity, coarsening, and tightly attached phase interfaces. The resulting materials exhibit a yield strength of 684 MPa at room temperature, with a maximum Vickers hardness of 1297 HV and an average hardness of 931 HV. The yield strength was retained at ~290 MPa even at 923 K. This method successfully overcomes the limitations of previous techniques, enabling the fabrication of positive mixing enthalpy composite materials and significantly broadening the boundaries of composite metal synthesis.

a Schematic illustration of the “interface riveting” mechanism. An initially weak contact between immiscible Cu and Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass particles is transformed into a strong, mechanically interlocked physical bond at the interface. b The schematic temperature-time profile of the UHSQ process, characterized by ultrafast heating (500 ~ 1000 K/s), a short sintering plateau at high temperature, and subsequent rapid quenching. c Schematic of the experimental procedure, showing the sample, housed in a ZrO₂ die, being rapidly heated between two carbon electrodes and then quickly submerged into a silicone oil bath for quenching. d Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images reveal rivet-like connections formed by physical deformation between Cu and FeCrMo nanocrystals. e A photographic sequence capturing the key moments of the actual UHSQ process. f The Cu-Fe-based composite pellet with positive mixing enthalpy was prepared by UHSQ sintering.

Results and discussion

Fabrication and microstructural characterization of Cu-Fe-based composites

The exceptional hardness of metallic glass is a significant advantage, but the smooth surface poses challenges for interface attachment32 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Mechanical milling has been proven to be an effective method for enhancing the attachment between phases33. To verify this, we employed high-energy ball milling and observed notable changes in the covering degree between phases as a function of milling time (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 5a). It was evident that Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass precursors subjected to high-energy ball milling exhibited significantly improved interfacial attachment with Cu particles. The continuous milling process not only introduces surface roughening into the Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass itself but also ensures uniform coverage of Cu on the surface of metallic glass particles34, facilitating subsequent connection with the Cu phase during sintering (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Notably, the particle size of Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass remains unchanged during high-energy ball milling. Additionally, the starting Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass particles are generally large, highlighting a potential direction for future optimization by reducing the size of metallic glass particles (Fig. 2d).

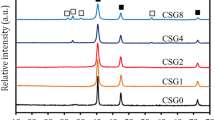

a Representative SEM micrograph showing the morphology of Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass particles. b, c The effect of high-energy ball milling for 1 h and 10 h, respectively, showing the progressive coating of the hard MG particles with ductile Cu to create an ideal precursor. d Statistical size distribution of ball-milled amorphous alloy particles. e XRD patterns and magnified regions of Cu-Fe-based composites fabricated via distinct sintering routes. f Optical micrograph of Cu-Fe-based composite processed by different sintering techniques. UHS and UHSQ methods suppress elemental segregation, with UHSQ further enabling a defect-free interfacial morphology.

To demonstrate the universality of our UHSQ technique, we fabricated Cu-Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 composite materials with a 1:1 volume ratio, where the Fe content reached 27.5%, far exceeding that of conventional Cu-Fe alloys. As a comparison, we also employed various sintering techniques to prepare samples. The XRD patterns of samples prepared via UHS and traditional furnace sintering were similar, displaying pure Cu phases (Fig. 2e left). Notably, in UHSQ specimens quenched within 1 second, weak crystalline peaks emerged (Fig. 2e right), suggesting partial devitrification of the amorphous matrix. In contrast, specimens subjected to a 10-second dwell time prior to quenching achieved near-complete crystallization, restoring the equilibrium Fe–Cr-Mo phase assemblage.

Optical and scanning electron microscopy images (Fig. 2f) demonstrate that conventional sintering (annealing at 1073 K for 2 h in Ar2, followed by annealing at 573 K for 6 h) fails to mitigate elemental segregation in Cu-Fe₅₅Cr₂₅Mo₁₆B₂C₂ positive mixing enthalpy alloys, resulting in phase-separated Cu-rich and Fe-rich coarsened domains. This phenomenon primarily originates from thermocapillary-driven Marangoni convection during liquid-liquid phase separation, as described by the Cahn-Hilliard model35,36. In contrast, UHS leverages ultrafast sintering rates to suppress elemental segregation and control the crystallization of the metallic glass reinforcements. Upon softening, the viscosity of the metallic glass temporarily behaves like an adhesive, tightly bonding the two phases and effectively extending the processing window. UHS is ultimately limited by the intrinsic immiscibility of positive-enthalpy systems and subcritical cooling rates, permitting interfacial phase separation that generates porous weak interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Fig. 7). This interfacial failure is directly linked to the sintering duration; prolonging the high-temperature exposure allows for the severe phase segregation demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 8d. Minimizing the sintering time is therefore critical to kinetically trap the system and suppress elemental segregation (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Remarkably, UHSQ, with its ultrafast cooling rates, refines grain structures while retaining the advantages of UHS. Moreover, UHSQ precisely regulates the devitrification pathway of the amorphous matrix, generating hierarchical microstructures that integrate nanocrystals with high-density lattice defects (Fig. 2f right and Supplementary Fig. 6d). The extreme quenching rate triggers distinct nanoscale architectural interlocking through stress-induced transformation. The microscopic rivet-like architecture at the nanoscale firmly bonds the Cu-Fe interface while constraining the distribution of individual components, resulting in a homogeneous interlocked Cu-Fe-based composite structure (Fig. 3a, b).

a TEM image showing the clean, well-bonded interface between the Cu matrix and the Fe-based reinforcement. b Higher-magnification image of (a), revealing the nanoscale interlocking structure, with corresponding EDS maps showing the distinct phases. c HAADF-STEM analysis of the devitrified reinforcement, revealing a nano-architecture of an Fe–Cr matrix, Mo-rich precipitates, and Fe-rich phase, confirmed by EDS mapping. The plot below quantifies the size distribution of these nanocrystals. d Room temperature tensile engineering stress-strain curves for the composites processed by UHS and UHSQ, compared with a monolithic Cu control sample. e Tensile engineering stress-strain curves at elevated temperature (923 K) for the UHS and UHSQ-processed composites. f, g SEM images of the tensile fracture surface of UHS and UHSQ-processed samples at room temperature. h SEM image showing the distribution of small metallic glass particles in the Cu matrix.

The rapid quenching process induces the formation of a multiscale structure within the Fe-based metallic glass (Supplementary Fig. 9). Bright-field TEM imaging reveals a regular and uniform distribution of nanoscale crystal particles within the metallic glass (Fig. 3c). Figure 3b collectively demonstrates that the Fe₅₅Cr₂₅Mo₁₆B₂C₂ metallic glass devitrifies into a multiphase nanocrystal, in which nanocrystalline Fe–Cr ferrite forms the continuous skeleton of the microstructure. The FCC Fe–Cr matrix surrounds and mechanically pins two secondary constituents, Mo-rich nanocrystals and Fe-rich areas. Bcc Mo-rich nanocrystals populate junctions and grain corners in a quasi-periodic manner, occupying ~14 vol% of the microstructure (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11a, b), surrounding each Mo grain is a shell of bcc Fe ferrite. Notably, the Fe-rich areas contain a mixture of pure Fe, partially retained amorphous phase (Supplementary Fig. 11c, e), and ordered B2 intermetallic phases that contribute to the overall intricate structure (Supplementary Fig. 11d). The complex arrangement indicates an incomplete devitrification process, resulting in a multiphase nanocrystalline structure with retained amorphous pockets. The overall microstructure exhibits a high density of interfaces and structural complexity. This intricate structural architecture, arising from the controlled devitrification of the initial metallic glass, significantly influences the material’s properties. These special nanocrystal structural features are critical for coherent Cu-Fe interfaces with periodic misfit dislocations, which geometrically resemble traditional mortise-tenon interlocking structures. The interlocking of different rivet structures creates a tight interface, with a strong attachment between them (Fig. 3a). Such microstructural control further contributes to the macroscopic uniformity of the composite. Furthermore, at different interface angles, no elemental cross-diffusion is observed, providing clear evidence that this technique effectively controls elemental segregation at the microscopic level (Fig. 3b right). Such unprecedented control over both structural hierarchy and elemental distribution redefines manufacturability limits for immiscible systems.

Multiscale strengthening mechanisms

We systematically compared the mechanical properties of materials processed under different sintering conditions. The optimized UHSQ-processed composites demonstrate a remarkable and comprehensive enhancement of mechanical properties, spanning bulk behavior (tensile and flexural strength) and surface performance (hardness and wear resistance). Using a composite with 50% Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 as an example, the ultimate tensile yield strength reached ~685 MPa, which is 6.5 times higher than pure Cu (Fig. 3d). Remarkably, this strength advantage persists at elevated temperatures, with the composite maintaining 290 MPa yield strength at 923 K (Fig. 3e). For comparison, we prepared control samples (Supplementary Fig. 12) with several key variations: reinforcement content, reinforcement type (pure Fe; Fe-based alloy), and high-temperature performance. All comparisons demonstrated significant improvements in mechanical performance originating from the unique, interlocking Cu-Fe interface, where continuous Cu-rich and Fe-rich phases form interpenetrating networks resembling rivet joints, a structure forged by the UHSQ method. These results emphasize the substantial performance enhancement achieved by UHSQ-processed high-Fe-content positive mixing enthalpy composites, including in high-temperature applications (Supplementary Fig. 13). The improvement is primarily attributed to the high strength of multiphase nanocrystals37.

SEM characterization reveals distinct morphological evolution between the samples prepared by UHS and UHSQ protocols (Fig. 3f, g). UHS-processed specimens exhibited compromised interfacial cohesion (average interfacial gap length: 2.1 ± 0.3 μm), accounting for their inferior mechanical performance (Supplementary Fig. 14). Suboptimal interfacial integrity originates from prolonged thermal relaxation during UHS processing, where thermal expansion mismatch induced interfacial decohesion. In contrast, UHSQ samples displayed tight interfacial bonding. The main reason is that the ultrafast cooling rate prevents the system from reaching equilibrium during the two-phase shrinkage process, enabling a strong attachment of different phases at high temperatures to be maintained at room temperature. The multi-phase nanocrystals formed strong interfaces with Cu, acting as rivets during tensile testing. The high interfacial bonding strength provided by the rivet-like structures is best demonstrated by the material’s failure mechanism. Instead of debonding at the interface, failure occurs via brittle trans-particle fracture, where cracks propagate directly through the reinforcement phase itself (Supplementary Fig. 15). The behavior shows that the interface is stronger than the reinforcement material. The interfacial integrity is also reflected in the bulk mechanical properties shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. While the difference in elastic modulus between the UHS and UHSQ samples contributes to the overall stress-strain response, the strength is predominantly attributed to a multiphase synergistic strengthening mechanism forged by the UHSQ process. The enhancement is not due to a change in intrinsic material stiffness but is a direct reflection of the strengthening effect from the improved interface bonding achieved by rapid quenching.

Fractography of UHSQ specimens revealed a homogeneous distribution of equiaxed dimples in the Cu matrix (Fig. 3g), indicative of good ductility. This structural uniformity is confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of the same fracture regions, which shows no evidence of large-scale elemental segregation (Supplementary Fig. 17). The suppression of elemental diffusion is further corroborated at higher resolution by corresponding SEM and TEM-based EDS line scans performed on cross-sections (Supplementary Fig. 18). Overall, we believe the enhancement in mechanical strength of this structure is manifested at different levels. Macroscopically, the Cu-rich and Fe-rich phases form two distinct interwoven network structures, similar to a rivet configuration, imparting excellent strength and ductility to the sample. For the composite with a 1:1 volume ratio of Cu to Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass, the composite achieves 8.91% tensile ductility, while enhancing the material’s overall strength and performance. Also, UHSQ allows for the adjustment of the Cu-Fe ratio to fine-tune the overall strength and ductility of the composite material. At the microscopic level, a small amount of Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass is dispersed within the Cu phase, creating a dispersion-strengthening effect that further improves mechanical performance (Fig. 3h). Furthermore, at the interface, the Cu-Fe phases bond seamlessly with no gaps, and the distribution of phases is uniform. Additionally, crystallization of the Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass leads to the formation of multi-phase nanocrystals, which exhibit remarkable strength to further enhance the material’s overall performance. The synergistic combination of rivet-like reinforcement and dispersion strengthening offers a clear pathway for further performance optimization, which can be achieved by tailoring particle size and distribution. This multiscale design strategy, which combines macro-architectural control with nanoscale precipitation engineering, provides a viable method for developing high-performance hybrid composites with enhanced properties.

Hardness and wear behavior

As shown in Fig. 4a, composites processed via UHSQ exhibit a significantly higher Vickers hardness than those prepared by UHS or pure Cu, achieving a high and consistent average hardness of 900 HV. The value is approximately three times higher than that of UHS-processed samples and eight times higher than pure Cu (Supplementary Fig. 19). The hardness significantly exceeds the prediction from a simple linear rule of mixtures, indicating powerful synergistic strengthening effects. The origin of this synergy can be understood from the microhardness distribution shown in Fig. 4b. The Fe-based reinforcement contains in-situ formed nanocrystalline intermetallic compounds and possesses a high intrinsic hardness of ~1100 HV, which provides a strong foundation for the composite’s overall performance. Furthermore, the co-continuous, interlocking network architecture imposes a strong mechanical constraint on the softer Cu phase (which has a hardness of only ~90 HV). The constraint is enabled by a robust interface, which exhibits a high average hardness of ~500 HV and ensures efficient load transfer during indentation (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). Significant work hardening occurs in the ductile Cu matrix during deformation, further increasing its contribution to the overall hardness. It is the combination of these effects that results in the composite’s hardness.

a Microhardness profiles measured from the sample surface inwards for the UHSQ-processed composite, UHS-processed composite, and pure Cu. The shaded bands represent the standard deviation of the measurements. b Representative microhardness line scan across the Cu matrix, the Cu-Fe interface, and multi-phase nanocrystals. c The plot of microhardness versus electrical conductivity (% IACS), benchmarking the UHSQ-processed composite against various material classes reported in the literature22,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55. (The colored background regions categorize different material systems: the pale pink region represents Cu-based alloys, the pale cyan region represents metallic glasses and ceramics, and the pale purple region corresponds to the W-Cu alloy family). d Wear test results showing the wear loss rate as a function of friction cycles under a load of 10 MPa and a sliding speed of 500 r/min. e Optical micrographs of the worn surfaces of UHSQ-processed composites with 25 vol% and 50 vol% Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass, showing uniform wear tracks. f High-magnification SEM images tracking the morphology of multi-phase nanocrystals on the wear surface after 15 and 60 minutes of sliding.

We summarized the hardness and electrical conductivity of Cu alloys, ceramic-metal composites, and metallic glasses reported in the literature22,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 (Fig. 4c). The positive mixing enthalpy composites synthesized via UHSQ exhibit superior hardness compared to conventional Cu alloys, approaching the strength of metallic glasses and ceramic-metal composites. The electrical conductivity ranges between 15 and 20% IACS, which is generally superior to metallic glasses or ceramic-metal composites. This property holds significant potential in certain specialized materials, such as the conductive rails of electromagnetic launchers and the tracks of electromagnetic catapult systems, which require conductive materials that possess ultrahigh hardness, heat resistance, and erosion resistance38,39. Moreover, the mechanical properties can be tuned by adjusting the content of Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass. Increasing the proportion improves strength, whereas decreasing it enhances ductility. This tunability highlights the potential for future optimization and broader applications.

We conducted wear tests on UHS and UHSQ-processed samples, which are compared to pure Cu. The tests applied a 10 MPa load, rotated at 500 r/min, with mass loss measured every 5 minutes. Fitted data curves show that UHSQ-processed composites demonstrate 40–50 times higher wear resistance than pure Cu (Fig. 4d). Samples with 25% and 50% Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass clearly exhibited strong Fe-based networks, contributing to greater macroscopic strength (Fig. 4e). Further SEM characterization of UHSQ-processed samples before and after 15 minutes and 60 minutes of wear testing revealed surface changes (Fig. 4f). The multi-phase nanocrystals showed minimal structural degradation, demonstrating their contribution to the enhancement of wear resistance. Strong interfaces and robust attachment also play a critical role in improving tribological performance. Photographic evidence of wear damage under identical test conditions highlights the superior wear resistance of UHSQ-processed composites compared to sintered pure Cu (Supplementary Fig. 22). This study demonstrates an application view of positive mixing enthalpy composite materials. The seamless interlocking architecture with strong interfaces opens substantial possibilities for next-generation sliding electrical contacts, high-load tribological components, and thermally stable conductor substrates. It addresses critical needs in sustainable energy systems, heavy machinery, and aerospace electronics, where concurrent electrical and mechanical robustness is essential.

Our method provides valuable guidance for designing advanced composite materials and highlights the potential of positive mixing enthalpy composites for structural and functional applications. The ability to tailor mechanical properties through compositional adjustments underscores the flexibility and scalability of this approach. In terms of scalability, the process’s fast speed enables high-throughput manufacturing of large-area sheets and coatings, with current capabilities extending to near-centimeter thick bulk components; the primary focus for future scaling is addressing the engineering challenge of uniform quenching in even larger volumes. At its core, the method’s success lies in the microscale rivet-like structure induced by rapid quenching, which produces an unprecedented strengthening effect at the interface. The approach produces homogeneous positive mixing enthalpy composites with a well-balanced structure, successfully controlling phase segregation while preserving both toughness and hardness. The universality of this approach suggests that leveraging its advantages in future material design will significantly expand the boundaries of composite material synthesis and development.

We have developed a bottom-up approach using the UHSQ process to fabricate positive mixing enthalpy composites that uniquely combine the excellent ductility of pure Cu with the ultrahigh strength of hard alloys. The process leverages controlled partial crystallization during rapid heating to accelerate densification, while subsequent rapid quenching is then critical to preserve a key portion of the amorphous phase in the final microstructure. The strength of the composite originates from the robust, rivet-like interlocking interface forged between the Cu matrix and the multi-phase nanocrystals. Our interlocked Cu-Fe-based composite overcomes the traditional strength-ductility trade-off, achieving a good combination of electrical conductivity (15–20% IACS) and ultrahigh hardness (900 HV). This work demonstrates the tremendous potential of positive mixing enthalpy composites for advanced structural and functional applications. Our approach facilitates the development of previously inaccessible immiscible alloy systems. The good balance of properties makes the material highly promising for demanding applications, including advanced mechanical components, aerospace systems, and particularly for electromagnetic propulsion and high-performance tribological components. Ultimately, the UHSQ process preserves the unique properties of the constituent phases, significantly expanding the synthesis boundaries for advanced metallic composites.

Methods

Synthesis

The Cu-coated Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass precursor was prepared by mixing Cu (99%, Aladdin) and metallic glass (99% Yijinxc) in a 1:9 mass ratio using ZrO₂ as the grinding medium. High-energy ball milling was performed for 20 hours. The prepared coated precursor was then mixed with Cu (99%, Aladdin) in a 1:1 volume ratio. After further ball milling for 0.5 hours with ZrO₂ balls, the precursor was retrieved and shaped into a bulk form. Cold isostatic pressing at 250 MPa was employed to prepare a composite billet. Subsequently, the UHSQ technique was applied. The composite billet was wrapped in ZrO₂ fiber cloth, which serves as a high-temperature electrical insulator to prevent short-circuiting between the conductive sample and the carbon heaters. The high temperature of the carbon heater was monitored using a thermal infrared imager (628CH-L25).

Mechanical property characterization

The stress-strain curves at room temperature of the samples were measured with a Shimadzu AGS-X 10 Kg tensile machine operated at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1. An extensometer (RVX-112B) was used to ensure accurate strain reading. The stress-strain curves of the samples at high temperature were measured with an Instron 45582 tensile machine operated at a strain rate of 1 × 10−3 s−1. Specific sample dimensions are provided in Supplementary Fig. 23b. The hardness testing was performed using a Heng Yi MH-31 tester. The nanoindentation tests were performed on an Oxford Instruments Femto-Tools nano indenter, and the specific test locations were selected based on the tensile fracture samples divided into regions at different distances (Supplementary Fig. 23a).

Materials characterization

The metallographic photographs were taken after polishing and grinding using an optical microscope of ZEISS AXIO Imager (A1m), to observe the distribution of metallic glass and Cu. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were taken using a cold field emission scanning electron microscope (SU8220), Zeiss G500 SEM, and Guoyi Quantum SEM5000X to observe the morphology of the sample. The crystal phases were examined by UltimaIV (Rigaku Corporation, Japan) XRD and scanned between 10° and 80° using Cu Kα radiation. A differential scanning calorimeter (DSC-Q200) from TA Instruments was used to monitor and measure the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the Fe55Cr25Mo16B2C2 metallic glass. Furthermore, the detailed microstructures of the interfaces and the corresponding elemental distributions were analyzed using TEM and EDS on an FEI Talos F200X G2 system.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. Additional experimental data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information and from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Podgorsek, A., Jacquemin, J., Pádua, A. & Gomes, M. C. Mixing enthalpy for binary mixtures containing ionic liquids. Chem. Rev. 116, 6075–6106 (2016).

Zhang, W.-T. et al. Frontiers in high entropy alloys and high entropy functional materials. Rare Met. 43, 4639–4776 (2024).

Jiang, S. et al. Ultrastrong steel via minimal lattice misfit and high-density nanoprecipitation. Nature 544, 460–464 (2017).

Gao, J. et al. Facile route to bulk ultrafine-grain steels for high strength and ductility. Nature 590, 262–267 (2021).

An, Z. et al. Negative mixing enthalpy solid solutions deliver high strength and ductility. Nature 625, 697–702 (2024).

Cao, G. et al. Liquid metal for high-entropy alloy nanoparticles synthesis. Nature 619, 73–77 (2023).

Li, X. Negative enthalpy raises strength and ductility. Nat. Mater. 23, 178–178 (2024).

Hsu, W.-L., Tsai, C.-W., Yeh, A.-C. & Yeh, J.-W. Clarifying the four core effects of high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 471–485 (2024).

Sathiyamoorthi, P. & Kim, H. S. High-entropy alloys with heterogeneous microstructure: processing and mechanical properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 123, 100709 (2022).

Chen, Z., Zhang, H. & Lei, Y. Secondary solidification behaviour of AA8006 alloy prepared by suction casting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 27, 769–775 (2011).

Tang, Y. et al. Overcoming strength-ductility tradeoff with high pressure thermal treatment. Nat. Commun. 15, 3932 (2024).

Bachmaier, A., Kerber, M., Setman, D. & Pippan, R. The formation of supersaturated solid solutions in Fe–Cu alloys deformed by high-pressure torsion. Acta Mater. 60, 860–871 (2012).

Kim, W. et al. Texture development and its effect on mechanical properties of an AZ61 Mg alloy fabricated by equal channel angular pressing. Acta Mater. 51, 3293–3307 (2003).

Schottelius, A. et al. Crystal growth rates in supercooled atomic liquid mixtures. Nat. Mater. 19, 512–516 (2020).

Wang, C. P., Liu, X. J., Ohnuma, I., Kainuma, R. & Ishida, K. Formation of immiscible alloy powders with egg-type microstructure. Science 297, 990–993 (2002).

He, J., Zhao, J. Z. & Ratke, L. Solidification microstructure and dynamics of metastable phase transformation in undercooled liquid Cu–Fe alloys. Acta Mater. 54, 1749–1757 (2006).

Prokoshkina, D., Esin, V. A. & Divinski, S. V. Experimental evidence for anomalous grain boundary diffusion of Fe in Cu and Cu-Fe alloys. Acta Mater. 133, 240–246 (2017).

Chen, K. X. et al. Morphological instability of iron-rich precipitates in CuFeCo alloys. Acta Mater. 163, 55–67 (2019).

Moon, J. et al. A new strategy for designing immiscible medium-entropy alloys with excellent tensile properties. Acta Mater. 193, 71–82 (2020).

Jiao, Z. B. et al. Synergistic effects of Cu and Ni on nanoscale precipitation and mechanical properties of high-strength steels. Acta Mater. 61, 5996–6005 (2013).

Velthuis, S. G. E. et al. The ferrite and austenite lattice parameters of Fe–Co and Fe–Cu binary alloys as a function of temperature. Acta Mater. 46, 5223–5228 (1998).

Wu, Y. et al. An overview of microstructure regulation treatment of Cu-Fe alloys to improve strength, conductivity, and electromagnetic shielding. J. Alloy. Compd. 1002, 175425 (2024).

Zhou, B. C. et al. Mechanisms for suppressing discontinuous precipitation and improving mechanical properties of NiAl-strengthened steels through nanoscale Cu partitioning. Acta Mater. 205, 116561 (2021).

Isheim, D., Gagliano, M. S., Fine, M. E. & Seidman, D. N. Interfacial segregation at Cu-rich precipitates in a high-strength low-carbon steel studied on a sub-nanometer scale. Acta Mater. 54, 841–849 (2006).

Cai, P. et al. Local chemical fluctuation-tailored hierarchical heterostructure overcomes strength-ductility trade-off in high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 214, 74–86 (2025).

Xu, D., Wang, X. & Lu, Y. Heterogeneous-structured refractory high-entropy alloys: a review of state-of-the-art developments and trends. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2408941 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. A general method to synthesize and sinter bulk ceramics in seconds. Science 368, 521–526 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Rapid synthesis and sintering of metals from powders. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004229 (2021).

Telford, M. The case for bulk metallic glass. Mater. today 7, 36–43 (2004).

Pan, J. et al. Extreme rejuvenation and softening in a bulk metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

Shimizu, F., Ogata, S. & Li, J. Yield point of metallic glass. Acta Mater. 54, 4293–4298 (2006).

Suryanarayana, C. & Inoue, A. Iron-based bulk metallic glasses. Int. Mater. Rev. 58, 131–166 (2013).

Wang, F. et al. Influence of two-step ball-milling condition on electrical and mechanical properties of TiC-dispersion-strengthened Cu alloys. Mater. Des. 64, 441–449 (2014).

Schroers, J. Processing of bulk metallic glass. Adv. Mater. 22, 1566–1597 (2010).

Elliott, C. M. The Cahn-Hilliard model for the kinetics of phase separation. In Mathematical models for phase change problems 35–73 (Springer, 1989).

Saldi, Z. S. Marangoni driven free surface flows in liquid weld pools. Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands (2012).

Haubold, T., Bohn, R., Birringer, R. & Gleiter, H. Nanocrystalline intermetallic compounds—structure and mechanical properties. in High Temperature Aluminides and Intermetallics 679–683 (Elsevier, 1992).

Fair, H. Advances in electromagnetic launch science and technology and its applications. IEEE Trans. Magn. 45, 225–230 (2009).

Weiming, Lu, J. & Liu, Y. Research progress of electromagnetic launch technology. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 47, 2197–2205 (2019).

Dölling, J., Henle, R., Prahl, U., Zilly, A. & Nandi, G. Copper-based alloys with optimized hardness and high conductivity: research on precipitation hardening of low-alloyed binary CuSc alloys. Metals https://doi.org/10.3390/met12060902 (2022).

Fu, H. et al. Breaking hardness and electrical conductivity trade-off in Cu-Ti alloys through machine learning and Pareto front. Mater. Res. Lett. 12, 580–589 (2024).

Maki, K., Ito, Y., Matsunaga, H. & Mori, H. Solid-solution copper alloys with high strength and high electrical conductivity. Scr. Mater. 68, 777–780 (2013).

Li, Y.-C., Zhang, C., Xing, W., Guo, S.-F. & Liu, L. Design of Fe-based bulk metallic glasses with improved wear resistance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 43144–43155 (2018).

Cheung, T. L. & Shek, C. H. Thermal and mechanical properties of Cu–Zr–Al bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloy. Compd. 434–435, 71–74 (2007).

Zhang, G. et al. Preparation of non-magnetic and ductile Co-based bulk metallic glasses with high GFA and hardness. Intermetallics 107, 47–52 (2019).

He, J. & Schoenung, J. M. A review on nanostructured WC–Co coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 157, 72–79 (2002).

Krell, A. High-temperature hardness of Al2O3-base ceramics. Acta Metall. 34, 1315–1319 (1986).

Balko, J. et al. Nanoindentation and tribology of VC, NbC and ZrC refractory carbides. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 4371–4377 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Hardness of polycrystalline wurtzite boron nitride (wBN) compacts. Sci. Rep. 9, 10215 (2019).

Ban, Y. et al. Properties and precipitates of the high-strength and electrical conductivity Cu-Ni-Co-Si-Cr alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 93, 1–6 (2021).

Han, T. et al. W–Cu composites with excellent comprehensive properties. Compos. Part B: Eng. 233, 109664 (2022).

Duan, Q. et al. Synergistic enhancement of mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of immiscible bimetal: a case study on W–Cu. Engineering 46, 224–235 (2025).

Liu, J.-K., Wang, K.-F., Chou, K.-C. & Zhang, G.-H. Fabrication of ultrafine W-Cu composite powders and its sintering behavior. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 2154–2163 (2020).

Hou, C., Cao, L., Li, Y., Tang, F. & Song, X. Hierarchical nanostructured W-Cu composite with outstanding hardness and wear resistance. Nanotechnology 31, 084003 (2020).

Xiaoyong, Z., Jun, Z., Junling, C. & Yucheng, W. Structure and properties of W-Cu/AlN composites prepared via a hot press-sintering method. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 44, 2661–2664 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 52272249 to C.W., 52201190 to Z. Wu, 22209165 to C.W. and 52222104 to S.L.). Z. Wu acknowledges the financial support from the Scientific Research Innovation Capability Support Project for Young Faculty (no. SRICSPYF-BS2025072), the Guangdong and Hong Kong Universities ‘1 + 1 + 1’ Joint Research Collaboration Scheme, and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2024A1515010964). We sincerely thank Professor Laima Luo from Hefei University of Technology for her support with testing and thank Sheng Peng, Shangshu Wu and Xiao Dong from City University of Hong Kong (Dongguan) for their valuable assistance. We thank Shengquan Fu at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, University of Science and Technology of China, for assistance with the OXFORD Femto-Tools Nano Indenter (installed on CIQTEK Co., Ltd., FESEM5000X) measurements and characterizations. We also thank Dr. Jie Tian from the Material Test and Analysis Lab, Engineering and Materials Science Experiment Center at the University of Science and Technology of China, and Jianliu Huang from Carl Zeiss China for their valuable discussions and technical support with the Zeiss G500 SEM. The TEM work was partially carried out using Scientific Compass (www.shiyanjia.com).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W., Z.W., and S.S. conceived and designed the UHSQ experiments. S.S. conducted the UHSQ sintering experiments, metallographic analysis, mechanical property testing, TEM imaging, and SEM imaging with EDS mapping. S.S. also prepared the samples, performed XRD measurements, and carried out XRD characterization. C.W., S.L., Z.W., X.L., and S.S. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and provided comments on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, S., Wu, Z., Liu, X. et al. Breaking immiscibility barriers: ultrafast sintering of interlocked Cu-Fe-based composites. Nat Commun 17, 1357 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68107-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68107-3