Abstract

Iontronic power source harnesses ion-electron coupling effect for energy conversion, offering great potential in wearable electronics and bioelectronics. However, its limited power density and insufficient current hinder the progress toward commercialization. Here we report an iontronic electricity generator based on intrinsic asymmetric interfaces and controllable energy-release, which reaches a maximum volumetric power density of up to 3680 W m-3, area power density of 18.4 W m-2, and peak current of more than 5 A. Cycling power generation is ascribed to reversible electron-coupled ion-oscillation at interface. Synergistically, the intrinsic asymmetric interfaces facilitate ion-electron coupling interaction, and the energy-release gate optimizes the energy conversion pathway, thus ensuring giant power output. The developed generator shows large-scale manufacturability and good flexibility. These exceptional performances in iontronic power source not only offer useful paradigms for wearable electronics, but also indicate a strategy and direction into high-power energy conversion from low-grade environmental source.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iontronics have attracted increasing attention with the ever-growing advancement of human-machine interaction1,2. Unlike conventional electronics that rely on electrons as charge carriers, iontronics integrate electron-ion charge transport and signal exchange at interfaces, enabling diverse functionalities3,4. Such versatility has driven the development of iontronic devices, including transistors5,6,7, sensors8,9, memristors10,11, and power generators. Among them, iontronic power generator (IPG) enables the conversion of natural energy into electricity, making it essential for self-sustaining devices and bioelectronic applications12,13,14. IPG can form asymmetric ion/electron interfaces within ion gradient in response to external stimuli such as light, heat and mechanic force, driving ion diffusion and ion-electron interaction across asymmetric interfaces15,16,17,18. Thus, the induced asymmetric interfaces serve as the backbone for charge transport and energy conversion in IPGs.

Over the past decade, various strategies have been developed to enhance the responsive asymmetry of interfaces, including designing multiscale hierarchical architectures19,20, engineering heterogeneous device structures21,22,23, and developing highly sensitive functional materials24. These advancements have significantly improved power-generation performance. Beyond stimulus-induced asymmetric ion-electron interfaces, intrinsic asymmetric ion-electron interfaces naturally exist in biological systems and play a crucial role in efficient bioelectricity generation, as exemplified by heterogeneous charged lipids25,26. In light of this, the direct construction of intrinsic asymmetric iontronic-interfaces (IAIs) provides an alternative approach for achieving artificial high-performance power generation.

We find that a pair of nanostructured materials with different ionizable functional groups and interface polarity in an electrolyte, naturally acquires distinct surface charge and ions at the interfaces. This enables controllable construction of IAIs without the need for external stimuli. Previously, IAIs have been utilized in asymmetric electrochemical supercapacitors or primary volta cell, enhancing energy storage density or enabling disposable power supply27,28. However, IAIs for sustainable and high-power energy generation have yet to be reported. Achieving reversible and efficient ion/electron migration based on simply asymmetric two-electrode configuration, without specific stimulus or pre-charging process, remains a challenge.

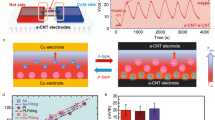

Design principle for reversible power generation

Herein, we report a reversible iontronic power generation by adopting IAIs and controllable energy-release gate (Fig. 1). The IAIs are composed of capacitive electrode pairs featured with oppositive surface charges and considerable intrinsic capacitances (Ci), contributing to sufficiently inherent pre-storage of reversely charged ions at interfaces in a charge-free manner. The energy-release gate is designed with an on-off switch, which can be triggered by various environmental energy sources such as light, heat, or force. Cycling power generation mainly relies on reversible interfacial-ion oscillation, assisted by dissolved oxygen-mediated interfacial redox reaction during on-off switching of energy-release gate. As a result, the asymmetric-electrodes based power generator (AEPG) is capable of chemically driven re-generation and energy storage based on ion-electron coupling effect, enabling the energy conversion from waste low-grade chemical energy into electric output. Importantly, the chemical energy of oxygen and water molecules, a ubiquitous resource in ambient environment, could provide a sustainable energy source for this process. In general, the IAIs facilitate ion-electron coupling interaction, and the energy-release gate optimizes the energy conversion pathway, synergistically ensuring giant electric output. The cycling AEPG can supply an ultra-high peak current and power density of up to 5 A and 3680 W m−3, the highest value among other sorts of typical IPGs reported to date.

Schematic illustration of the power-generating process through reversible interfacial-ion oscillation mediated by interfacial redox reaction. The AEPG is composed of IAIs and controllable energy-release gate. The IAIs facilitate ion-electron coupling interaction, and the energy-release gate optimizes the energy conversion pathway, synergistically ensuring giant electric output.

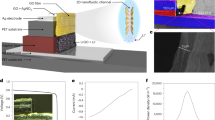

Construction and characterizations of intrinsic asymmetric iontronic-interfaces (IAIs)

In principle, asymmetric material pairs are suitable for the construction of IAIs. The nanostructured MnO2 and titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx) MXene emerge as representative candidates, attributed to the following advantages: 1) opposite surface charges and surface polarities, 2) engineered nanostructures that enable intrinsic ion pre-storage at interface, 3) solution processability for scalable fabrication.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) indicate that nanostructured MnO2 is composed of uniform nanoparticles with size of in range of several hundred nanometers (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). The MXene nanosheets were synthesized by selectively etching method29. The lateral size of MXene nanosheets is 1 ~ 3 μm as determined by TEM (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a−c). The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of MXene nanosheets exhibits hexagonal symmetry, confirming the crystalline nature of hexagonal phase (Supplementary Fig. 2d). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) demonstrates the presence of Mn-OH functional groups on the surface of MnO2 nanoparticles, along with −F/O/OH functional groups on MXene nanosheets (Supplementary Fig. 3). As result, the distinct ionizable functional groups contribute to the differentiation in interfacial polarity and surface charge characteristics between the MnO2 and MXene materials.

a SEM image of MnO2 nanoparticles. b TEM image of the MXene nanosheets. c SEM image of assembled porous MXene film on cellulose scaffold. All the results for (a–c) were repeated independently at least three times. d Zeta potential of MnO2 and MXene films in NaCl aqueous solution (200 mM). e, f Relative surface potentials of MnO2 (e) and MXene (f). g Comparison of UPS spectra of MnO2 and MXene films. h −Z” as a linear function of \(\frac{1}{2\pi f}\) for Ci analysis. i Schematics of asymmetric iontronics interfacial properties of surface charge and ion adsorption.

The MnO2 nanoparticles and MXene nanosheets demonstrate superior solution processability. Flexible MnO2 film is readily fabricated by blade-coating, and paper-like MXene film is prepared by dip-coating onto an interconnected cellulose scaffold (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 4). Proton-acid treatment30 can enhance the ambient stability of MXene films by suppressing water and oxygen intercalation (Supplementary Fig. 5). The as-prepared MnO2 and MXene films both exhibit porous nanostructures, which facilitate interfacial interactions and ion transport (Supplementary Fig. 6 and 7).

Furthermore, we analyze the interfacial properties of IAIs. Zeta potential testing indicates that MnO2 and MXene films are positively and negatively charged, respectively, as a result of surface functional group dissociation (Fig. 2d). Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) testing shows surface potential difference between MnO2 (~120 mV) and MXene film (~−285 mV, Fig. 2e and f). The work functions of MnO2 (4.5 eV) and MXene film (4.1 eV) are determined by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS, Fig. 2g). These results consistently confirm the reverse surface charge characteristic of the two materials, resulting in an intrinsic potential difference. Benefiting from distinct surface charge and porous nanostructures, the interfaces of MnO2 and MXene are capable for spontaneously storing sufficient interfacial ion based on electric double layer (EDL) effect, thereby facilitating natural formation of IAIs. To further quantify the intrinsic ion storage at interface, we introduce a parameter of intrinsic interfacial capacitance (Ci), which can be measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)31 (see the Methods section for details):

where f and Z” represents frequency and imaginary parts impedance, respectively. The low-frequency response in EIS can reflect the capacitive characteristics of interface, which are related to ion adsorption and accumulation at interface. As shown in Fig. 2h, the Ci of MnO2 and MXene (2 × 2 cm2) is 62 and 83 mF, respectively, demonstrating substantial ion accumulation at interface. Therefore, the interfaces of MnO2 and MXene demonstrate clear iontronic asymmetry and significant intrinsic storage, validating the available construction of IAIs (Fig. 2i).

Electric output performance of asymmetric-electrodes based power generator (AEPG)

The AEPG device adopts a sandwich structure, consisting of IAIs separated by an ultrathin cellulose membrane and immersed in an aqueous NaCl electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 8). Due to interfacial asymmetry of IAIs, the intrinsic electrode potential (Eintrinsic) of MnO2 electrode (~ 0.48 V) versus to Ag/AgCl reference electrode obviously exceeds that of MXene (~0.04 V) at pristine state (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The AEPG unit (2 × 2 cm2) featured with low internal resistance (~4 Ω), can generate open-circuit voltage (Voc) and short-circuit current (Isc) peak of up to 0.45 V and 30 mA (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 9b). The AEPG device retains ~46% of its initial current after cycling power generation for 280 h, underscoring its repeated electricity-generating capability (Supplementary Fig. 10). Both interfacial asymmetry and Ci are essential for achieving high-performance electric output. For instance, symmetric electrode pairs exhibit negligible Voc and Isc. The asymmetric MnO2-graphite or MXene-graphite device renders a minimal Isc alongside considerable Voc as result of low Ci of graphite (1.9 μF cm−2, Supplementary Fig. 11). In contrast, MnO2-MXene AEPG offers superior Voc and Isc, outperforming other devices. Diverse potential-asymmetric electrode pairs can be harnessed to construct IAIs, and corresponding AEPGs deliver favorable performance, elucidating the power-generating universality (Supplementary Fig. 12).

a Comparison of the Voc and Isc of devices (2 × 2 cm2) with symmetric or asymmetric electrode pairs. b Voltage evolution of AEPG after prolonged short-circuiting discharge. c, Voltage-time curve during repeatedly discharging/re-generating cycles. The discharging current was set to 100 μA. d Current-time curve of AEPG device without energy-release gate. Upon switching gate-on, the APEG device continuously keeps discharged state. Inset is an enlargement of time ranging from 18 to 54 s. e Electric energy density output of AEPG without gate. f, Current-time curve of AEPG device with gate. g Electric energy density output of AEPG with gate.

The AEPG delivers cyclic electric output without pre-charging from an external electric power. After the completed release of pre-stored energy through prolonged short-circuiting discharge, the AEPG recovers to its initial voltage (~0.45 V) at re-off state, validating its inherent regenerative property (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 13). Moreover, the AEPG can be discharged in a tunable constant-current manner. Upon discharging to 0 V, the full-discharged AEPG repeatedly recovers its voltage at the re-off state, further affirming re-generating behavior (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 14).

Relying on an intermittent cyclic power generation mode, the AEPG undergoes cycles of regeneration, energy storage, and periodic energy output during discharge. This mode inspires the design of an environment-triggered energy-release gate, facilitating the device to achieve an adaptive and environmentally compatible intermittent operation. The energy-release gate can be implemented through a stimuli-responsive on/off switch, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 15. To verify its effectiveness, we systematically compare the current and electric energy output characteristics of the device with and without the energy-release gate. In the absence of an energy- release gate, the device generates continuous current output upon triggering on-state, but the current rapidly drops from 30 mA to 0.015 mA within ~1 min (Fig. 3d). Correspondingly, the output energy curve exhibits a plateau, with the output electricity energy density approaching a limited value of 16.5 J m−2 ( ~ 115 h, Fig. 3e), exhibiting disposable power supply. In contrast, the AEPG with energy-release gate affords intermittent cyclic current signals (Fig. 3f). The output energy density exhibits a linear accumulation with the increasing cycles, reaching up to 543 J m−2 ( ~ 115 h, Fig. 3g), which is ~33 times higher than that of device without energy-release gate. The result reveals that energy-release gate is available for optimizing energy conversion pathway and essential to giant electric output. In the lack of an energy-release gate, the generated energy of device is unable for accumulation, leading to continuous but weak current output that is practically unusable. In essence, the energy-release gate enables physicochemical interface modulation, which allows ions to be stored at the interface and then collectively released, thereby optimizing energy conversion pathway. The paradigm of slow harvesting and collective release, provides an alternative route for achieving giant conversion from low-grade energy.

The electrode nanostructure facilitates interfacial ion adsorption owing to its high specific surface area, thus ensuring high current output (Supplementary Fig. 16). The AEPG operates reliably over a wide temperature range (0 to 60 oC, Supplementary Fig. 17) and shows good compatibility with hydrogel electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 18). The AEPG operates in various electrolytes, with performance differences arising from variations in ion mobility (Supplementary Fig. 19a). The generated voltage varied slightly with the ion concentration, while the current signal exhibited increasing variation with ascending concentration owing to enhanced Ci and ion migration (Supplementary Fig. 19b). On the account of the influence of separator thickness on device resistance, the current output of AEPG was visibly decreased with increasing spacing (Supplementary Fig. 19c and d). Different recovery time has an effect on electric output, because AEPG requires an adequate recovery period to return to its initial state (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Validation of the electricity-generating mechanism

The underlying mechanism of AEPG can be ascribed to reversible ion migration mediated by redox reactions at asymmetric ion/electron coupled interfaces, thereby integrating chemical energy harvesting, interfacial storage, and electrical conversion within a simple two-electrode configuration (Fig. 4a). Specifically, reversible electricity generation in AEPG proceeds through three distinct states: original, discharging, and re-generating. In the original state, MnO₂ and MXene films inherently exhibit opposite surface charges and selectively adsorb counter-ions through functional group ionization, resulting in IAIs formation. Upon triggering gate-on for discharging, interfacial ions are released away from interfaces through the internal circuit. Meanwhile, the electrons flow through external circuit and excess electronic charge accumulates at electrode surfaces. Prior studies have demonstrated that interfacial redox reaction could induce charge transfer to power electricity generation and even drive spontaneous catalysis32,33,34,35,36. On this basis, accumulated electric charge can be transferred by spontaneous interfacial redox reaction during the regeneration process, leading to ion re-adsorption and energy regeneration in AEPG. Through reversible ion/electron coupling, the AEPG achieves cyclic power generation. Unlike air self-charging batteries that rely on bulk ion insertion/extraction37,38,39, the AEPG operates via interfacial ion migration. In contrast to conventional IPGs with simultaneous energy generation and discharge, the AEPG decouples these processes. The harvested environmental energy is stored then released collectively, contributing to unprecedent performance output (Supplementary Fig. 21).

a Schematic illustration of the proposed working principle on cycling power generation. b Schematic diagram of in-situ EQCM testing. The f0, μ, and ρ, A represents the resonant frequency of the fundamental mode, shear modulus, density of the crystal, and area of the gold disk, respectively. c The Δm of MnO2 and MXene electrodes versus time during power generation. d Electrode potential evolution of MnO2 and MXene electrodes during discharging/regenerating cycles. e Contour-type in situ Raman spectra of electrode material during cycling electricity generation. f Time-dependent dissolved oxygen concentration. g Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy of electrode pair with/without power generation.

Above-mentioned mechanism is further supported by experimental and theorical results related to interfacial ion migration and electron transfer. Electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) monitors trace-level mass change (Δm) through frequency change (Δf), enabling real-time tracking of ionic fluxes at interface (Fig. 4b). Upon discharging, a significant decrease in electrode mass is observed, signifying the expulsion of interfacial ion from interface (Fig. 4c). In the re-generating state, the electrode mass increases and returns to its initial value due to the ion re-migration to interface. The periodic variation in the electrode mass provides strong evidence for the reversible ion migration at interface during cycling power generation. Kinetic Monte Carlo simulation further uncovers reversible ion migration, which is modeled by electrode pairs with opposite charges (Supplementary Fig. 22). Simulated ion distribution at interfaces renders reversible variation during cyclic power generation, coinciding with the experimental results (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Along with interfacial ion-oscillation, the electrode potential exhibits dynamically reversible fluctuations during electricity generation (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 24). Cyclic voltammogram curves of electrode display a notably rectangular shape within the scanning window corresponding to fluctuated range, devoid of discernible redox peaks, elucidating their capacitive property and reliable electrochemical stability (Supplementary Fig. 25). In-situ Raman spectra illustrate that the characteristic peaks of MnO2 and MXene electrodes remain no discernible variation during cycling electricity generation, demonstrating their stable phase structure characteristics (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 26). The morphological microstructure and chemical composition of the electrodes display negligible change after energy generation cycles, as verified by SEM and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy results (Supplementary Fig. 27 and 28).

In the re-generating process, the accumulated interfacial charge could initiate interfacial redox reaction, which plays a critical role in ion re-adsorption and energy regeneration. Interfacial charge transfer consumes dissolved oxygen or yields reactive oxygen intermediates (e.g., hydroxyl radical)34,38,40. To validate this mechanism, dissolved oxygen concentration in the electrolyte is monitored during cycling electricity generation using dissolved oxygen meter (Supplementary Fig. 29a). The concentration of dissolved oxygen decreases obviously after repeated electricity generation, indicating oxygen consumption during re-generating process (Fig. 4f). The consumption amount of oxygen correlates positively with the transferred charge (Supplementary Fig. 29b). When oxygen into the electrolyte is inhibited, the AEPG device fails to recover its voltage, whereas vigorous stirring greatly enhances oxygen mass transport and leads to rapid regeneration (Supplementary Fig. 30a and b). The spontaneity of the interfacial redox reaction is confirmed using a galvanic-like cell configuration, where the observed cell voltage (~0.2 V) indicates that dissolved oxygen-mediated interfacial electron transfer could be thermodynamically favorable (Supplementary Fig. 30c and d). Above results coherently corroborates the significant role of dissolved oxygen in mediating interfacial charge transfer.

EPR spectroscopy is employed to detect hydroxyl radical (·OH) during re-generating process, using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent40,41,42. As shown in Fig. 4g, no visible signal is detected on the MXene electrode prior to power generation. In contrast, the quadruplet DMPO-·OH (1:2:2:1) characteristic peaks appears during power generation, evidencing hydroxyl radical formation. Meanwhile, no DMPO-trapped radical signals are detected at the MnO2 electrode either before or after power generation. Therefore, the observed dissolved O2 consumption and •OH formation can verify the presence of the interfacial reaction, which mediates interfacial charge transfer and supplies the driving force for reversible ion migration and energy regeneration.

In the energy conversion process of AEPG, low-graded chemical energy derived from interfacial redox reaction could serve as the energy input. This input is harvested and stored at EDL interfaces as an intermediate state, and ultimately converted into electrical energy. The energy conversion efficiency of APEG is estimated to be about 23% (Supplementary Fig. 31, see the Supplementary Note 1 for details)

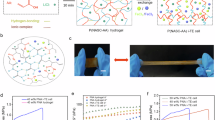

Scalable manufacturability and integration of flexible AEPGs

Due to the excellent solution processability of MnO2 nanoparticles and MXene nanosheets, they can be formulated into an ink, enabling scalable and industry-compatible manufacture. By utilizing continuous roll-to-roll coating and dip-coating techniques, the large-scale production of MnO2 and MXene films becomes feasible with low cost, paving the way for practical applications (Supplementary Fig. 32 and 33 and Supplementary Video 1). A roll of electrode materials with a length of up to 4.5 m is displayed in Fig. 5a. AEPGs with different sizes are feasible with ease and exhibits favorable electricity-generating performance (Supplementary Fig. 34). The generated Isc of AEPG increase linearly with the device area, verifying the scaling current output of AEPG. Unprecedently, a large-area AEPG, comparable in size to A4 paper, delivers an Isc of more than 5 A, representing the highest value among other sorts of typical IPGs reported to date (Fig. 5b and d, Supplementary Table 1). By integration in series, the Voc of AEPGs increases proportionally with the number of units, reaching around 6 V with 13 units (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 35). Previously reported IPGs exhibit low current density and limited performance-scalability, primarily due to the bottleneck in achieving synchronized stimulus-response behavior over large areas, which significantly constrains overall current output43. The complicated processing of device manufacture further hinders its feasibility for large-scale applications44. Strikingly, the AEPG enables a linearly scalable output, attributed to its high current density, scalable manufacturability and innovative working mechanism.

a Photograph of a MnO2 electrode roll with a length of up to 4.5 m and width of 9 cm. b Plot of Isc with various device area of AEPGs. c Plot of Voc with various serial number of AEPG units. d Systematic comparison of Isc in this work with other types of IPGs reported previously. The detailed data and references are listed in Supplementary Table S1. e Volumetric power density of APEG versus variable electric resistance. f Current retention with different bending cycles. Inset is photographs of bending AEPG.

Benefiting from foldable traits of materials, the scalable AEPG device can be further transformed into miniaturized and portable reconfiguration by using stacking strategy, which fully exploit vertical space. A tiny bulk of monolithic device (2 cm × 2 cm × 5 mm) supplies an Isc of ~143 mA, a giant area power density of 18.4 W m−2, and a volumetric power density of up to 3680 W m−3 with a load resistance of 5 Ω, prior to that of reported IPGs (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 36). Additionally, the AEPG is highly flexible and durable under repeated mechanical deformations (Supplementary Fig. 37). Even after bending for 1000 cycles, AEPG still maintains 95% current level (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Video 2), which make them highly suitable for powering wearable and flexible electronics that require high resiliency to various deformations.

Application demonstration for AEPG

As depicted in Fig. 6a, we developed a self-powered smart textile capable of on-demand electricity supply, intelligent luminescence display and real-time environmental sensing. The system integrates AEPGs with circuit design to function as a self-powered power source. The architecture primarily consists of AEPGs for electricity generation, a body-coupled energy-release gate driven by sorts of human motions (e.g., breathing, walking, arm movement), a power manager module for energy storage and circuit boosting, and a microcontroller for signal transmission, all of which can be woven within the fabric (Fig. 6b–d and Supplementary Fig. 38). The electric output of AEPGs is stored in a commercial lithium-ion battery and subsequently converted to a standardized 5 V output through a custom-designed booster circuit, enabling sufficient charging of various wearable electronics, such as smart telephone (Fig. 6e–g and Supplementary Fig. 39).

a Schematics illustration of smart wearable textile for achieving Internet of Things (IoT) system. b Photograph of smart wearable textile integrated with self-powered supply, body-coupled energy-release gate, indicator light, ambient sensor, and display textile. c Photograph showing self-powered supply system on the inside surface of the clothing. d Schematic of the circuit design of the self-powered smart textile. e The voltage–time curve of lithium-ion battery with a capacity of 30 mA h charged by integrated AEPG. f Standardized voltage of the self-powered supply system. g Photo of smart telephone charged by self-powered supply system. h Photograph of smart textile for intelligent display and environment monitoring (i.e., temperature and relative humidity). Electroluminescent textile for intelligent display is operated driven by self-powered supply system.

A flexible fiber-base electroluminescent indicator light is seamlessly integrated into clothing and efficiently powered by the integrated AEPGs. The intelligent luminescence display enhances self-visibility, thereby ensuring safer navigation in low-light conditions (Fig. 6h, Supplementary Fig. 40 and Supplementary Video 3). In addition, an ambient sensor, activated by self-powered supply system, enables real-time detection of atmospheric temperature and relative humidity. The collected data is transmitted to a microcontroller chip, which further relays the information to the textile display (Supplementary Fig. 41a). This real-time monitoring allows users to effortlessly track outdoor climate conditions, enhancing environmental awareness. This on-body interactive system could be particularly beneficial for individuals with conditions such as cerebrovascular disease or peripheral neuritis, who may have impaired sensitivity to environmental temperature and humidity (Supplementary Fig. 41b). By improving environmental perception, the system provides timely feedback and appropriate wear guidance, enhancing user comfort and safety.

Discussion

In summary, we have developed a facile strategy to achieve giant power generation by integrating naturally asymmetric iontronic-interfaces with a controllable energy-release gate. The asymmetric interfaces facilitate ion-electron coupling interaction, and environment-compatible gate optimizes the energy conversion pathway. Based on reversible interfacial ion migration mediated by interfacial redox reaction, the AEPG delivers an ultrahigh peak current and volumetric power density of up to 5 A and 3680 W m-3, respectively. Unlike conventional IPGs with simultaneous energy generation and discharge, our AEPG can decouple discharging and re-generating steps and implement “slow harvesting then collective energy-release” paradigm, thus leading to unprecedent performance output. Through continuous solution-coating techniques compatible with industrial production, large area flexible AEPGs can be mass-produced and endure repeated bending for thousands of cycles. The proof-of-concept application demonstration of AEPGs in self-powered smart textiles underscores their practical potential. This work paves the way for interface engineering strategies toward next-generation high-power iontronic power sources.

Methods

Preparation of MXene nanosheets dispersion

MXene dispersion was synthesized through etching method. Typically, 3.2 g of LiF (Sigma Aldrich) was added to 40 mL HCL solution (Sigma Aldrich, 9 mol L−1) under magnetic stirring. 2.0 g of MAX powder (Jilin 11 technology Co., Ltd., 400 mesh) was slowly added to the mixture. Then the solution was stirred at 45 °C for 36 h. After reaction, 100 mL of deionized water was added to terminate the reaction. The accordion-like MXene product was washed with deionized water for several cycles by centrifugation (2000 g, 5 min) until the supernatant became neutral. The resulting sediments were dispersed into deionized water, and sonicated for 15 min to accomplish exfoliation. Next, the solution was centrifuged at 1250 g for 30 min to remove the impurities. The purified Ti3C2Tx dispersion was further concentrated by centrifugation (2000 g, 45 min). Finally, the sediments were dispersed into deionized water to obtain 20 mg mL−1 MXene nanosheets dispersion.

Preparation of MnO2 slurry

Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, Mw~275000, 10 g) was dissolved in 500 mL N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Aladdin) to obtain uniform solution. Then ball-milling MnO2 nanoparticles (1.6 g), Super-P carbon black (Super P, 0.2 g) and 10 mL PDVF solution were mixed by a planetary mixer at 330 g for 10 min (DAC 330-100 SE, FlackTek SpeedMixer). Finally, the uniform MnO2 slurry was obtained.

Fabrication of AEPG device

The MnO2 film were fabricated by continuous blade-coating. The MnO2 slurry was coated on graphite foil and dried at 90 oC to remove NMP solvent. The MXene electrode were obtained by dipping coating. The cellulose paper (thickness of 0.15 mm) was dipped into 20 mg mL−1 MXene dispersion and dried at 60 oC. The as-prepared Mxene membrane is soaked into 0.1 M HCl for 10 min and washed by deionized water. Proton-acid treatment can remove extrinsic intercalants and enhance interlayer interactions, thereby improving the ambient stability of MXene by limiting the intercalation of H2O and O2 in the open air. Next, the as-prepared MnO2 and MXene films, and cellulose separator were stacked in a sandwich-type configuration with electrolyte addition (0.2 mol L−1 NaCl aqueous solution).

Electric measurements

The performance of electricity generation testing was carried out on a Keithley 2612B (Keithley Instruments, Cleveland, OH.). The circuit parameter for recording Voc was set current to 0 nA. The circuit parameter of testing Isc was set voltage of 0 V. It should be noted that, for large-area AEPG devices, the device resistance is very small, and the resistance of measurement leads becomes non-negligible. In this case, the measured current signal corresponds to that under a finite load due to voltage division between the internal and lead resistance. Accordingly, the actual Isc was obtained by correcting the measured values with consideration of the voltage division. The SW-520D, KSD9700, XH-M131, MKA50202 on/off switches served as gate, which could be induced by mechanic force, heat, light, and magnetism stimulus, respectively. The electrode potential and cyclic voltammogram curve were tested on a CHI 760D electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, Inc) by using a three-electrode electrochemical system. The investigated electrode, Pt foil, and saturated Ag/AgCl electrode was working electrode, counter electrode, and referenced electrode, respectively. The Ci was measured by electrochemical impedance (EIS) spectra. In the EIS test, the initial potential, frequency range and alternating current amplitude was set to Voc, 0.1 Hz − 100 kHz and 5 mV, respectively.

In situ EQCM test

EQCM test was carried out by the use of the CHI440C (CH Instruments, Inc). The electrode material of MnO2 or Mxene was coated onto quartz crystal served as investigated electrode. The EQCM test allows for simultaneous recording of both Voc and Δf of the quartz crystal. The EQCM cell was placed on a vibration-isolated probe station to minimize mechanical disturbances and enclosed within a metal shielding box to eliminate electromagnetic interference.

Experiments on human participants

All experiments were approval by the Institutional Review Board of Tsinghua University (approval no. 20220227). All human participants gave written and informed consent before participation in the studies.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) were conducted by using a Sirion-200 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Corporation, USA). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) were carried out on JEM-100Plus (JEOL, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were taken on a Bruker AXS D2 PHASER diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation source (Bruker Corporation, Germany). X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were obtained on an ESCALAB 250 photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) with an Al Kα source. In situ Raman spectra were measured on a LabRAM HR Evolution Raman microscope with a 532 nm laser (HORIBA Jobin Yvon, France).

Kinetic Monte Carlo simulation

The kinetic Monte Carlo simulation was conducted by using N-Fold Way (NFW) algorithm. The rate of a diffusional hop was written as:

where ΔE, D0, kB and T refer to energy change induced by hop, frequency factor, Boltzmann constant, and temperature, respectively. The total energy of our coarse grain model was written as:

where α is denoted as a scaling factor, the former term is used to describe the interaction between ions. Za is the charge quantity of the ath ions or electrodes (1e or −1e for ions and ±3e or ±1e for electrodes). The dc ensures that the coulomb attraction is sufficiently weak to be broken by kinetic energy (kBT). The dc and α were assumed 1 μm and 0.01 eV∙μm e−2 in the coarse grain model. Due to the differing Fermi levels of electrode pairs, electrons may transfer between electrode pairs, potentially disrupting charge neutrality at each electrode at gate-on state. Harmonic energy term (i.e., the second term) was employed to depict the physics wherein electrons transfer between two electrodes to minimize energy. The energy penalty arising from deviation from charge neutrality would hinder further electron transfer in the final stage. Eventually, the entire system reaches an equilibrium state. The second term, Kb is pre-factor (2 eV e−2), and Zref is a constant and equals to the average charge quantity of electrodes sites.

In the kinetic Monte Carlo simulations, the charge numbers of electrode pairs change based on \(\left(\frac{{2*P}_{f}}{1+\exp \left(-\frac{{t}_{s}}{{t}_{{sc}}}\right)}-{P}_{f}\right)\bullet ({N}_{f}-{N}_{i})\), where Pf is the final electron recovery proportion, ts is the simulation time and \({t}_{{sc}}\) is the characteristic time, and Nf and Ni are the final and initial charge numbers of electrodes, respectively. The distribution evolution of ions is mainly focused.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, W. et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 382, 559–565 (2023).

Yang, C. & Suo, Z. Hydrogel iontronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 125–142 (2018).

Wei, D., Yang, F., Jiang, Z. & Wang, Z. L. Flexible iontronics based on 2D nanofluidic material. Nat. Commun. 13, 4965 (2022).

Hou, Y. & Hou, X. Bioinspired nanofluidic iontronics. Science 373, 628–629 (2021).

Kim, H. J., Chen, B., Suo, Z. & Hayward, R. C. Ionoelastomer junctions between polymer networks of fixed anions and cations. Science 367, 773–776 (2020).

Xing, Y. et al. Integrated opposite charge grafting induced ionic-junction fiber. Nat. Commun. 14, 2355 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Tan, C. M. J., Toepfer, C. N., Lu, X. & Bayley, H. Microscale droplet assembly enables biocompatible multifunctional modular iontronics. Science 386, 1024–1030 (2024).

He, Y. et al. Creep-free polyelectrolyte elastomer for drift-free iontronic sensing. Nat. Mater. 23, 1107–1114 (2024).

Zhu, P. et al. Skin-electrode iontronic interface for mechanosensing. Nat. Commun. 12, 4731 (2021).

Dobashi, Y. et al. Piezoionic mechanoreceptors: force-induced current generation in hydrogels. Science 376, 502–507 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Scalable integration of photoresponsive highly aligned nanochannels for self- powered ionic devices. Sci. Adv. 10, eads5591 (2024).

Xiao, K., Jiang, L. & Antonietti, M. Ion transport in nanofluidic devices for energy harvesting. Joule 3, 2364–2380 (2019).

Yang, F. et al. Vertical iontronic energy storage based on osmotic effects and electrode redox reactions. Nat. Energy 9, 263–271 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. A microscale soft ionic power source modulates neuronal network activity. Nature 620, 1001–1006 (2023).

Li, X., Li, R., Li, S., Wang, Z. L. & Wei, D. Triboiontronics with temporal control of electrical double layer formation. Nat. Commun. 15, 6182 (2024).

Schroeder, T. et al. An electric-eel-inspired soft power source from stacked hydrogels. Nature 552, 214–218 (2017).

Han, C.-G. et al. Giant thermopower of ionic gelatin near room temperature. Science 368, 1091–1098 (2020).

Peng, P. et al. Photochemical iontronics with multitype ionic signal transmission at single pixel for self-driven color and tridimensional vision. Device 3, 100574 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Moisture adsorption-desorption full cycle power generation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2524 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Nature-inspired interfacial engineering for energy harvesting. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 218–233 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Bilayer of polyelectrolyte films for spontaneous power generation in air up to an integrated 1,000 V output. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 811–819 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Power generation from ambient humidity using protein nanowires. Nature 578, 550–554 (2020).

Duan, P. et al. Moisture-based green energy harvesting over 600 hours via photocatalysis-enhanced hydrovoltaic effect. Nat. Commun. 16, 239 (2025).

Shen, D. et al. Moisture-enabled electricity generation: from physics and materials to self-powered applications. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003722 (2020).

Latorre, R. & Hall, J. E. Dipole potential measurements in asymmetric membranes. Nature 264, 361–363 (1976).

Gurtovenko, A. A. & Vattulainen, I. Lipid transmembrane asymmetry and intrinsic membrane potential: two sides of the same coin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5358–5359 (2007).

Wu, M. et al. Arbitrary waveform AC line filtering applicable to hundreds of volts based on aqueous electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Commun. 10, 2855 (2019).

Tian, Z. et al. Printable magnesium ion quasi-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors for flexible solar-charging integrated units. Nat. Commun. 10, 4913 (2019).

Alhabeb, M. et al. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 29, 7633–7644 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Pristine titanium carbide MXene films with environmentally stable conductivity and superior mechanical strength. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 19069963 (2020).

Lockett, V., Sedev, R. & Ralston, J. Differential capacitance of the electrical double layer in imidazolium-based ionic liquids: influence of potential, cation size, and temperature. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 7486–7495 (2008).

Lee, J. K. et al. Spontaneous generation of hydrogen peroxide from aqueous microdroplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19294–19298 (2019).

Lee, J. K. et al. Condensing water vapor to droplets generates hydrogen peroxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 30934–30941 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Solid-liquid interface charge transfer for generation of H2O2 and energy. Nat. Commun. 16, 1692 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for direct oxidation of methane under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202403114 (2024).

Wang, Z., Dong, D., Tang, W. & Wang, Z. L. Contact-electro-catalysis (CEC). Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 4349–4373 (2024).

Zhang, C. Charge with air. Nat. Energy 5, 422 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. A chemically self-charging aqueous zinc-ion battery. Nat. Commun. 11, 2199 (2020).

Yan, L. et al. Chemically self-charging aqueous zinc-organic battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15369–15377 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for the degradation of organic pollutants using pristine dielectric powders. Nat. Commun. 13, 130 (2022).

Zhao, R. et al. Spontaneous formation of reactive redox radical species at the interface of gas diffusion electrode. Nat. Commun. 15, 8367 (2024).

Li, H. et al. A contact-electro-catalytic cathode recycling method for spent lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 1137–1144 (2023).

Huang, Y., Cheng, H. & Qu, L. Emerging materials for water-enabled electricity generation. ACS Mater. Lett. 3, 193–209 (2021).

Liu, R., Wang, Z., Fukuda, K. & Someya, T. Flexible self-charging power sources. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 870–886 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFB4609100 to L.Q.), Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Disciplines Breakthrough Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (JYB2025XDXM201), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22035005 to L.Q., T2596012, 52090032, 52350362 to H.C.). Sincere thanks go to Prof. Tianling Ren’s group for their generous support in experiments and comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Q. initiated and guided the research. H.W. designed and performed the experiments. L.Q. and H.W. wrote and revised the manuscript. F.L. and J.L. conducted the theoretical calculation. J.D., Y.W., T.H., Q.L., Q.Z. and H.C. gave advice on experiments. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript. L.Q. supervised the entire project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Tae Gwang Yun, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Dang, J., Wang, Y. et al. Intrinsic asymmetric iontronic-interfaces for giant power generation. Nat Commun 17, 1384 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68135-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68135-z