Abstract

Membrane nanofiltration provides a sustainable and energy-efficient platform for precise molecular separation. However, highly permselective and chemically stable membrane materials capable of operating under harsh conditions are currently lacking. Here we report a generalizable monomer–solvent dual engineering strategy that enables the one-step synthesis of chemically robust thiazole-linked polycrystalline covalent organic framework (COF) membranes via scalable interfacial polymerization under ambient conditions for ultraselective molecular separation. The fully π-conjugated aromatic skeleton and the spatially exposed heteroatoms on the irreversible thiazole linkages establish a lone-pair electron network, which not only forms an atomic hydration layer to protect the framework but also confers long-range regulation of electrostatic interactions. The thiazole-linked COF membranes exhibit remarkable structural stability in strong acids (e.g., 12 M HCl), good resistance to organic solvents and chlorine, and high pharmaceutical desalination permselectivity, achieving ion/pharmaceutical separation factors up to 690. This versatile thiazole-linked framework structure offers potential for the development of chemically stable aromatic conjugated COF membranes for diverse vital applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precision molecular separation in strongly acidic media is essential for a range of important applications pertinent to acid purification, resource recovery, and wastewater reclamation across renewable energy, chemical, and water industries1,2,3,4,5,6. Compared to existing technologies such as ion exchange and electrodialysis, membrane nanofiltration (NF) offers an attractive platform for sustainable liquid separation due to its high energy efficiency, operational simplicity, and low carbon footprint7,8,9,10,11. However, the application of NF in molecular separation and desalination under strongly acidic conditions is markedly constrained by the scarcity of solvent-processable, permselective, and long-term stable membrane materials.

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are crystalline organic porous polymers composed of covalently linked skeleton units12,13,14,15,16. The topologically ordered pore architecture, tunable chemical microenvironment, and good chemical stability render 2D COFs appealing for membrane separations17,18,19,20. Despite recent advancements in the fabrication of polycrystalline 2D COF membranes, maintaining their intact micro and macroscopic structures under strongly acidic conditions remains a challenge, as local bond scissions and slight stacking disruptions can lead to structural defects and loss of separation selectivity21,22,23,24. The structural instability of COFs fundamentally stems from the inherent dynamics of the connecting bonds and interlayer stacking. For instance, the nucleophilicity of reversible imine bonds makes imine-linked COF membranes highly susceptible to proton-induced framework degradation, while the limited π-conjugation system instigates weak interlayer π–π interactions, which usually result in loosening and slippage of the COF layers21,24,25,26. Pioneering studies have also revealed that specific interactions conferred by heteroatoms on the COF skeleton play a crucial role in transmembrane mass transport of permeates27,28,29,30,31. Unfortunately, heteroatoms on conventional COF skeletons are typically buried within the framework, significantly limiting their accessibility and interaction with solvents and solutes during filtration. We therefore speculate that rational design of the framework linkages to simultaneously enhance bonding strength and stacking stability while fully exposing backbone heteroatoms might be an effective way to improve the chemical stability and separation performance of 2D COF membranes.

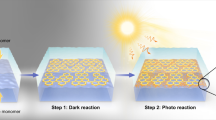

To verify this hypothesis, we propose using thiazole aromatic heterocycles as linking units to construct fully conjugated COFs with low reversible bonding and π-electron-rich aromatic linkages. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations reveal that the thiazole linkage possesses higher intrinsic bond energies of 5.39–9.42 eV (Supplementary Fig. 1), exceeding those of the imine bonds (4.23–7.83 eV) and β-ketoenamine bonds (4.77–8.16 eV). Besides, the fully π-conjugated framework significantly enhances the interlayer π–π stacking efficiency32,33,34. Compared to imine bonds (Fig. 1a), thiazole linkages also promote the spatial exposure of N and S heteroatoms on the framework (Fig. 1b), with a higher degree of exposure than other heterocyclic linkages (Supplementary Fig. 2). These fully exposed heteroatoms are expected to serve as readily accessible active sites to form lone-pair electron networks and localized hydration layers on the thiazole-conjugated skeleton, potentially enhancing its structural stability and modulating transmembrane mass transport (Fig. 1c, d). Unfortunately, the de novo synthesis of structurally intact thiazole-linked polycrystalline COF thin films under mild conditions remains an unsolved challenge, as irreversible conjugated structures often inhibit the self-repair of organic frameworks35,36,37.

a, b Schematic illustration of a heteroatom burial in imine-linked COFs and b exposure of heteroatoms in thiazole-linked COFs. c, d Schematic diagram of the enhanced c separation performance and d acid stability in thiazole-linked COF membranes conferred by the fully π-conjugated structure and heteroatom exposure. e Synthetic routes and chemical structures of thiazole-linked TbBa-azo membrane and imine-linked TbPa membrane. For schematic atoms in (a–c): N (blue) and S (yellow). For ball-and-stick model colors in (c–e): C (grey), S (yellow), N (blue), and H (white).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of thiazole-conjugated TbBa-azo membrane

To overcome the high activation energy barrier of the two-step condensation reaction during thiazole ring formation, we conceived a monomer–solvent dual engineering strategy to promote the interfacial polycondensation of monomers from both thermodynamic and kinetic perspectives. Specifically, this strategy optimizes the reactivity of the monomers, thereby lowering the energy barrier of the thiazole cyclization reaction. Simultaneously, it accelerates the membrane formation kinetics by manipulating monomer diffusion at the interface through a refined solvent environment. The feasibility of this approach was demonstrated by synthesizing a TbBa-azo COF membrane on the mesitylene/water interface using 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxaldehyde (Tb) and 2,5-diamino-1,4-benzenedithiol dihydrochloride (Ba) as framework-building units (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), and then extended to the preparation of other thiazole-linked COF membranes. For comparison, TbPa COF membrane with conventional imine linkages was also prepared using Tb and p-phenylenediamine (Pa) as the monomers (Fig. 1e).

The –SH group adjacent to –NH2 on the benzene ring of the Ba monomer provides several thermodynamic advantages for the in situ formation of the thiazole linkage. As an internal sulfur source, –SH circumvents the traditional high-temperature post-sulfurization reaction (Supplementary Fig. 5). The –SH group is readily deprotonated to form a thiolate anion, which has higher reactivity with imine bond (C = N) intermediate (nucleophilicity index increases from 0.314 to 2.581 e × eV), thereby lowering the activation energy barrier of the thiazole cyclization step (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, the intramolecular S…H–C = N hydrogen bonds (bond length = 2.55 Å) exerted by –SH shorten the distance between the S and the C atoms in the imine bond, further promoting the cyclization reaction by instigating spontaneous spatial anchoring and stabilizing spatial arrangement (Supplementary Fig. 7). On the other hand, we designed a mesitylene/water biphasic solvent system to facilitate the interfacial polycondensation of Ba and Tb from the perspective of reaction kinetics (Fig. 2a). Molecular simulations reveal that the coexistence of –SH and –NH2 groups on the benzene ring endows the Ba molecule with amphiphilicity, inducing an energy trap (ΔE) of 17.34 kJ mol−1 at the interface that drives Ba to undergo self-directed interfacial accumulation (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 8). This interfacial pre-concentration of Ba monomers promotes the formation of TbBa-azo COF membrane by significantly accelerating condensation kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and monomer diffusion monitoring experiments both confirm the self-driven interfacial aggregation behavior of Ba molecules (Supplementary Fig. 9b). In contrast, Pa monomer (a molecular analogous of Ba but containing only the –NH2 groups) exhibits only hydrophilicity, and therefore no amphiphilic equilibrium and molecule accumulation were observed at the mesitylene/water interface (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figs. 9c and 10–14), which lead to retarded nucleation and growth of the corresponding TbPa COF membrane (Supplementary Fig. 9d).

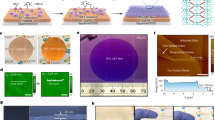

a Schematic illustration of Ba self-aggregation at the mesitylene/water interface. b Potential of mean force (PMF) profile of Ba diffusing from the water phase across the interface into mesitylene. c Monomer-interface distances at different time points during MD simulations (molecule ID 1–8: Ba, molecule ID 9–16: Pa). Chemical and structural characterizations of TbBa-azo membrane: d Cross-sectional (top) and top-surface (bottom) FESEM images. e Top surface 3D AFM image. f FTIR spectra. g 13C ssNMR spectrum. h N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution calculated based on non-local density functional theory (NLDFT). i DFT-optimized unit cell parameters of the AA-stacking model. Top: front view, bottom: top view. Gray shaded regions indicate free volumes in the unit cell. j HRTEM image (left) and the corresponding IFFT (top right) and SAED (bottom right) patterns. k GIMIC map calculated based on DFT-optimized conformation. Black, blue, and red arrows indicate the field direction, internal ring current, and external ring current, respectively. l RDG scatter plot of interlayer stacking interactions in TbBa-azo. Red and blue dots represent attractive and steric repulsion interactions, respectively. The inset visualizes the interaction regions of two stacked layers. For ball-and-stick model colors in (i and k): C (grey), S (yellow), N (blue), and H (white).

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) images show that the TbBa-azo membrane possesses a self-standing, intact structure and a dense, pinhole-free surface with low roughness (Ra = 1.02 nm, Rq = 1.28 nm) (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 15). The disappearance of the absorption peaks corresponding to –CHO (1695 cm−1), –NH2 (3415 cm−1), and –SH (2563 cm−1), along with the appearance of signals for C = N (1629 cm−1) and S–C (678 cm−1) in the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra corroborate the formation of thiazole linkages (Fig. 2f). The strong absorption signals of thiazole and benzene carbons at 100–180 ppm in the 13C solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) spectrum further confirm the chemical characteristics of the TbBa-azo COF skeleton (Fig. 2g). N2 sorption isotherms suggest that the TbBa-azo membrane possesses uniform pores with a diameter of 1.36 nm (Fig. 2h), which well aligns with the simulation value (1.27 nm, Supplementary Figs. 16–20). Further characterization by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Supplementary Fig. 21), Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 22), and ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy (Supplementary Figs. 23–25) further verifies the successful synthesis of thiazole-linked TbBa-azo membrane. Theoretical modeling shows that TbBa-azo adopts a hexagonal lattice (P6/m space group) with an AA-stacking conformation (Fig. 2i). X-ray diffraction (XRD) and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) data are in good agreement with theoretical predictions, where the strong diffractions at 2θ = 4.6° and q = 3.17 nm−1 well match the lattice parameters of the (100) plane in the AA-stacking model (Supplementary Fig. 26). Grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) analysis further confirms that the TbBa-azo membrane predominantly adopts a face-on orientation with the (100) crystal plane pointing upwards (Supplementary Fig. 27). The highly ordered lattice fringes observed in high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image and corresponding inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) pattern confirm the crystallinity of TbBa-azo, while the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern corresponding to the (001) plane indicates an interlayer spacing of 0.376 nm between adjacent COF monolayers (Fig. 2j). Gauge-including magnetically induced current (GIMIC) map displays a significant net diatropic current within the thiazole ring and a net paratropic current outside (Fig. 2k), implying that the thiazole linkages form a fully π-conjugated aromatic network on the TbBa-azo skeleton. Reduced density gradient analysis (RDG) and independent gradient model (IGM) confirm the strong interlayer π–π interactions within TbBa-azo (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. 28).

Spatial exposure of heteroatoms on the TbBa-azo skeleton

In the TbBa-azo membrane, the spatial exposure of heteroatoms on the thiazole linkages is a key structural feature in its design (Fig. 3a). DFT calculations suggest that the exposure angles of N and S atoms in TbBa-azo reach 120.9° and 158.2°, respectively, significantly larger than those of N atom in the imine-linked TbPa (48.1° and 94.9°) (Fig. 3b). As a result, the exposed volume of N and S atoms reaches 526.42 Å3, approximately 5.1 times larger than that of the imine N atom in TbPa (103.22 Å3), signifying the substantially enhanced accessible space around the heteroatoms. Structurally, due to the concealment of the linear imine configuration and the shielding of the adjacent hydrogen atoms on the benzene ring (Fig. 3c), the N atom in the imine bond is partially exposed. Conversely, the rigid five-membered cyclic geometry of the thiazole ring renders the N and S heteroatoms protruding outwards, and their spatial exposure is further amplified due to the absence of adjacent hydrogens. Notably, the enhanced heteroatom exposure in TbBa-azo is a permanent and stable structural feature due to the high bond energy and low binding dynamics of the thiazole linkages (Supplementary Figs. 29–32).

a Schematic illustration of heteroatom exposure in thiazole-linked TbBa-azo and imine-linked TbPa. b Exposure angles (left) and exposure volumes (right) of heteroatoms obtained from angle measurements of DFT-optimized framework models and atoms-in-molecules analysis of the atomic occupied volume, respectively. Yellow and blue colored regions represent the spatial distribution of the atomic occupied volumes of S and N atoms, respectively. c Illustration of the geometric basis of heteroatom exposure in thiazole and imine linkages. d Surface water contact angle, data represent two independent measurements (n = 2) and error bars indicate variability between measurements. e IGM analysis (isosurface value = 0.005) of the N…H–O hydrogen bonds formed between thiazole and H2O molecules, and scatter plot of the IGM analysis. Blue, green, and red represent hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, and steric effects, respectively. f Average number of N…H–O H-bonds formed by TbBa-azo and TbPa obtained from hydration MD simulations. g Average water density distribution in the pore channels of TbBa-azo and TbPa calculated by hydration MD simulations. h LOL analysis of TbBa-azo. The larger the LOL index, the higher the degree of electron localization. i Electrostatic potential mapping of TbBa-azo (left, isosurface value = 0.005) and the lone pair electron network (represented by the blue shaded volume) distributed along N atoms in the pore channels (right, isosurface value = 0.05). j Surface zeta potential as a function of pH. For ball-and-stick model colors in (b, e, g, and i): C (grey), S (yellow), N (blue), and H (white).

Consistent with our hypothesis, the extensively exposed heteroatoms in TbBa-azo also provide a feasible approach to finely tune the pore microenvironment. Contact angle measurements imply that the static water contact angle of the TbBa-azo membrane is much smaller than that of the TbPa membrane (73.5 ± 1.2° vs. 92.2 ± 2.8°) (Fig. 3d, details on the synthesis and characterization of the TbPa membrane refer to Supplementary Figs. 33–40), indicating enhanced atomic-level hydration. The improved water affinity of TbBa-azo is primarily attributed to the strong N…H–O hydrogen bonds formed between the highly exposed N atoms and water molecules (Fig. 3e). MD simulations show that the number of N…H–O hydrogen bonds formed in TbBa-azo is more than twice that in TbPa (53 vs. 25) (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Figs. 41–43). Spatial distribution analysis of water molecules captured in the pore channels further reveals that the number density of H2O around the N atoms in TbBa-azo is substantially larger than that in TbPa (Fig. 3g), which provides a fundamental insight into the enhanced water-capturing ability of the former.

Atomic-level charge quantification indicates that a single TbBa-azo pore window carries a net charge of −3.420 e (Supplementary Figs. 44 and 45), comparable to that of acidic COFs with a high density of ionizable functional groups. This strongly negatively charged pore environment mainly originates from the lone-pair electron network constructed by exposed heteroatoms. Localized orbital locator (LOL) analysis shows that Pauli repulsion between bonding electron orbitals in the framework forces lone pairs of electrons on N/S atoms to orient themselves (LOL index > 0.5, Fig. 3h), while heteroatom exposure further pushes these electrons outward, making them orderly localized within the pores, thus facilitating the formation of a lone pair electron network. Electrostatic potential mapping visualizes a continuous band of −0.063 eV negative potential along N and S atoms (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 46), confirming the formation of the electron network. Interestingly, zeta potential measurements reveal that the TbBa-azo membrane has a slightly more negative potential than TbPa at relatively low pH (pH < 6), while at higher pH values, this difference becomes marginal (Fig. 3j). This suggests that the negative charge induced by heteroatom exposure is primarily achieved by modulating the geometrical accessibility of the electron network. Restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) atomic charge analysis further corroborate this conclusion, showing that the thiazole ring and imine bond have almost identical intrinsic net atomic charge (−0.569 vs. −0.492, Supplementary Fig. 45). Collectively, characterization and molecular simulations confirm that heteroatom exposure effectively modulates the water affinity and charge density of the TbBa-azo pore channel, which provides an effective platform for finely tuning the transmembrane transport of water molecules and solutes.

Heteroatom exposure enables ultraselective molecular separation

The nanofiltration performance of the TbBa-azo membrane was subsequently evaluated and compared with that of the imine-linked TbPa membrane. Notably, the thickness, surface roughness, and mechanical integrity of both membranes are intentionally adjusted to be nearly identical by optimizing the synthesis conditions to eliminate the influence of these factors on filtration performance (Supplementary Figs. 47–54). Pure water permeance of the TbBa-azo membrane reaches 95.8 LMH MPa−1, which is 68.4% higher than that of the TbPa membrane (56.9 LMH MPa−1) (Supplementary Fig. 55), mainly due to the substantially enhanced atomic-level hydration of the TbBa-azo pore channels. The solute retention capabilities of the two membranes were then examined using a series of multidimensionally characterized ions, dye molecules, pharmaceuticals, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as model solutes (Supplementary Figs. 56–58). Compared to TbPa membranes, TbBa-azo membrane shows 1.05–51.8% higher rejection rates for negatively charged molecules and divalent anions (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 59 and 60), while maintaining high water permeance during the filtration of these solutes (Fig. 4a). Moreover, TbBa-azo membrane almost completely rejects dye molecules with molecular weights greater than 461 Da, pharmaceuticals larger than 544 Da, and PFAS above 564 Da, with rejection rates exceeding 99%. PFAS are environmentally persistent and bioaccumulative pollutants, and their widespread presence in drinking water poses a long-term threat to human health. Conversely, TbBa-azo and TbPa exhibit similar rejections for small neutral molecules and monovalent anions, both lower than their rejection rates for negatively charged solutes (Supplementary Figs. 59 and 60). Given that the pore size and thickness of the two membranes are almost identical, the improved permselectivity of the TbBa-azo membrane mainly stems from its π-conjugated skeleton and full exposure of heteroatoms, which simultaneously enhance water permeation and electrostatic repulsion by forming hydrophilic negatively charged networks within the pore channels.

a Water permeance and PFAS rejections of TbBa-azo and TbPa membranes. b Separation selectivity of TbBa-azo membrane for binary mixtures of pharmaceuticals and inorganic salts. c ermselectivity comparison of TbBa-azo membrane with state-of-the-art membranes for pharmaceutical/NaCl separation. Data for reference membranes are taken from previously reported studies (detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 1). d Electron density difference map on X–Y plane between the CRO molecule and heteroatoms in TbBa-azo. Red and blue regions represent the increased and decreased electron density, respectively. e IGM scatter plot of CRO interactions with heteroatoms in TbBa-azo and TbPa, and visualization of the interactions (bottom inset: green isosurface denotes regions of intermolecular interaction). f Schematic diagram of the pharmaceutical/salt separation mechanism governed by the coupling of electrostatic repulsion and size exclusion effects in TbBa-azo membrane. g MD simulation box used to simulate the transport of CRO and NaCl through TbBa-azo membrane. h Visualization of the transport trajectories of Na+, Cl−, and CRO during the MD simulations. i PMF profiles of Na+, Cl−, and CRO transported through the TbBa-azo membrane. All data in (a, b) represent two independent measurements (n = 2) and error bars indicate variability between measurements. For ball-and-stick model colors in (d, e, and g): C (grey), S (yellow), N (blue), H (white), Na (brown), Cl (green), and O (red).

Considering the high pharmaceutical rejections (>99.9%) and the low NaCl retention rate (33.2%) of the TbBa-azo membrane (Supplementary Fig. 60), we further evaluated its performance in pharmaceutical desalination. Separation factors for ceftriaxone (CRO)/NaCl and Vitamin B12 (VB12)/NaCl binary systems reach values of 690.0 and 693.1, respectively (Fig. 4b), outperforming TbPa membrane (<10.7) and other membranes reported to date (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 61, and Supplementary Table 1). TbBa-azo membrane also achieves high separation factors of 54.9–469.6 for binary mixtures of VB12/divalent salts (i.e., VB12/MgCl2, VB12/MgSO4, and VB12/Na2SO4) (Fig. 4b), mixtures that are usually difficult to fractionate by nanofiltration, highlighting the effectiveness of heteroatom exposure in regulating transmembrane mass transport of different solutes to achieve high selectivity.

To gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the high permselectivity in molecular desalination, we further investigated the mass transport behavior of molecules (i.e., CRO) and ions (i.e., Na+ and Cl−) through the TbBa-azo membrane. DFT calculations reveal that organic molecules and salt ions exhibit distinct conformational disorder, molecular size, charge, and functional groups (Supplementary Fig. 62). The localized long-range negative charges in TbBa-azo impart pronounced electrostatic interactions with the permeate, laying the foundation for selective membrane separation. When a CRO molecule is placed within the pore channel of TbBa-azo at a distance of 3 Å from the heteroatoms, the electron density between CRO and heteroatoms decreases significantly (index <0.000 e Å−3) (Fig. 4d), and the electrostatic repulsion energy between CRO and the pore wall reaches 54.5 kJ mol−1, approximately 3.7 times that of TbPa (14.7 kJ mol−1) (Supplementary Figs. 63 and 64). A similar phenomenon was observed with Cl− anion, but the electron density between Na+ and heteroatoms increases (Supplementary Fig. 65), indicating an attractive electrostatic interaction between TbBa-azo and cations. IGM analysis and visualization further indicate that the electrostatic repulsion between TbBa-azo and CRO is significantly stronger than that between TbPa (Fig. 4e), which is consistent with the difference in electron density between the two frameworks. The strong electrostatic interactions present in TbBa-azo have also been observed in the separation of other molecules and salt ions, where negatively charged solutes experience significant repulsion when approaching the heteroatoms, whereas positively charged solutes undergo weak adsorption through polarization-induced attractions (Supplementary Figs. 66–70). Additionally, the repulsion CRO gradually decreases under high ionic strength conditions, further corroborating the proposed charge exposure mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 71).

Interestingly, we also found that heteroatom-induced electrostatic interactions only become significant when the size of the permeate matches the size of the COF pore channels (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 72), culminating in the occurrence of steric sieving selectivity. MD simulations of the separation of the CRO/NaCl binary mixture (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 73) demonstrate that time-resolved snapshots of the Z-axis trajectories indicate that CRO molecules are completely excluded from entering the pores of the TbBa-azo membrane, while Na+ and Cl− ions rapidly permeate rapidly with minimal resistance (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 74). Potential of mean force (PMF) analysis quantified the entry and transport energy barriers of CRO, Na+, and Cl− (Fig. 4i). CRO encounters a huge energy barrier of 31.91 kJ mol−1, which is much higher than the energy barriers of Na+ and Cl− (<10 kJ mol−1), and also significantly higher than the energy barriers for ions transport through the defective TbBa-azo membrane (<13 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Fig. 75). Furthermore, the nearly constant hydration numbers of Na+ and Cl− ions (hydrated radius: 0.33–0.36 nm) across the pore channels further corroborate the facilitated transport of small ions under low transmembrane energy barriers (Supplementary Fig. 76), underscoring the important role of the synergy of electrostatic repulsion and size exclusion mechanisms. Therefore, compared to charge modulation at the molecular scale, heteroatom exposure allows for more precise control over the spatial extent of electrostatic interactions. Local electrostatic repulsion is only significantly activated when the solute approaches these exposed heteroatoms. Consequently, TbBa-azo membrane can effectively retain large pharmaceutical molecules while selectively permeating small salt ions, achieving pharmaceutical/salt selectivity improved compared to previously reported membrane materials38,39,40,41,42.

Ultraselective molecular desalination in strongly acidic media

The chemical and structural stability of TbBa-azo and TbPa membranes under strongly acidic conditions was evaluated by immersing them in 12 M HCl solution for 504 h. FESEM images show that the TbBa-azo membrane maintains its intact morphology without any detectable structural defects, while the TbPa membrane exhibits pronounced macroscopic structural disintegration (Supplementary Fig. 77). Filtration tests further demonstrate that TbBa-azo membrane preserves its water permeance and high rejection of over 99% for Eriochrome black T (EBT) after acid treatment, while the EBT rejection of the TbPa membrane decreases from 99% to 65% accompanied with a sharp increase in water permeance, signifying the well-retained pore structure of the former under strongly acidic conditions (Fig. 5a). In addition, the acid-treated TbBa-azo membrane maintains its structural invariance and good mechanical robustness (Supplementary Figs. 78 and 79). The TbBa-azo membrane also exhibits improved acid resistance compared to other COF and metal–organic framework (MOF) membranes and most polymer membranes reported to date (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 2).

a Rejections of EBT by TbBa-azo and TbPa membranes after soaking in 12 M HCl for different times. Insets: photographs of membranes treated for 0 and 504 h. b Comparison of acid resistance performance of TbBa-azo membrane with state-of-the-art membranes. Data for reference membranes are taken from previously reported studies (detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 2). c Relationship between linkage dissociation energy and linkage dissociation distance. d Stacking separation energy versus the stacking separation distance. Dissociation and separation directions are indicated by the red arrows. e Schematic of the formation of a protective water shell via localized hydration induced by exposed heteroatoms. f Localized hydration near the linkage bonds in TbBa-azo and TbPa obtained from AIMD simulations. g Distribution of water molecules (blue dots) and protons (red dots) in the pore channels of TbBa-azo. h Schematic illustration of salt recovery from acidic pharmaceutical wastewater using TbBa-azo membrane. i Photograph of the recovered NaCl product (top) and TOC data of the feed and filtrate (bottom). For ball-and-stick model colors in (c, d, f, and g): C (grey), S (yellow), N (blue), and H (white). For schematic atoms in (e and h): N (blue), S (yellow), O (red), H (white), and F (purple), respectively.

We believe that the good stability of the TbBa-azo membrane in strong acids stems from its aromatic π-conjugated structure with fully exposed heteroatoms. The thiazole-conjugated skeleton endows the membrane with strong bond strength and interlayer cohesion, with a bond dissociation energy as high as 1024.5 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 5c) and a stacking separation energy up to 171.8 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 5d), significantly exceeding those of the imine-linked TbPa membrane. Furthermore, the enhanced exposure of N and S heteroatoms in TbBa-azo promotes local hydration of water molecules surrounding the thiazole linkages, forming a protective water shell that protects chemical bonds from acid attack while maintaining high water permeance (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Figs. 80 and 81, and Supplementary Table 3). The existence of this protective hydration shell was verified by ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, in which a hydrogen bonding network rapidly formed between water molecules and the exposed heteroatoms in the thiazole linkages within 1.6 ps (Fig. 5f). Membrane hydration simulations further reveal that TbBa-azo captured almost the same number of water molecules in acidic media as in pure water (54 vs. 53 counts, Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 82), corroborating the preferential accumulation of water molecules around the thiazole linkages even in the presence of protons. The resulting hydration shell pulls protons away from the thiazole linkages and drives their distribution toward the center of the pore channel rather than the backbone (Fig. 5g). In contrast, the imine bonds in TbPa failed to form a protective hydration shell (Fig. 5f), and fewer water molecules were captured in acidic media than in pure water (18 vs. 25 counts, Supplementary Fig. 82 and Fig. 3f), approximately 2.9 times fewer than in TbBa-azo, indicating the crucial role of heteroatom exposure in hydration shell formation.

In view of the good acid stability and high NaCl/pharmaceutical selectivity of the TbBa-azo membrane, we challenged its application in pharmaceutical desalination under strong acid conditions (Fig. 5h). The selective separation of pharmaceuticals from inorganic salts facilitates salt recovery and pollutant enrichment, which significantly reduces the chemo-biological inhibition in downstream wastewater treatment processes (e.g., Fenton oxidation and biodegradation), with potential to improve treatment efficiency and lower costs. The simulated wastewater used in the tests features typical high salinity and strong acidity conditions, which were spiked with representative pharmaceuticals (Supplementary Table 4). After secondary filtration through the TbBa-azo membrane, the total organic carbon (TOC) concentration drops from 92.94 to 1.46 mg L−1 (Fig. 5i), and UV–vis spectra show no pharmaceutical residues detected in the filtrate (Supplementary Fig. 83). The overall NaCl/pharmaceuticals separation selectivity reaches 31.8, and 248.1 mg of high-purity NaCl (>99.9%) salt was recovered after neutralization (Fig. 5i), demonstrating the enhanced stability and molecular desalting ability of the TbBa-azo membrane even under strongly acidic conditions.

Discussion

The thiazole aromatic heterocycle has proven to be a versatile structural motif for constructing fully π-conjugated COF structures with high bond energies and strong interlayer interactions. Spatially exposed heteroatoms and lone-pair electron networks aligned along the pore channels enhance the molecular separation permselectivity and acid resistance of the corresponding thiazole-linked COF membranes, as demonstrated by high ion/pharmaceutical selectivity and long-term stability in strong acids. More importantly, this thiazole linkage can be extended to the synthesis of other COF topologies and other interfacial polymerization solvent systems (Supplementary Figs. 84–93), showcasing the versatility of this design strategy. The implemented monomer–solvent dual engineering approach successfully transforms these COF structures into intact COF membranes with good mechanical strength, thermal stability, organic solvent tolerance, acid and chlorine resistance, and antifouling properties (Supplementary Figs. 94–100 and Supplementary Table 5). This work provides a design paradigm for preparing high-performance COF membranes for a variety of important applications under harsh conditions.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

All reagents and solvents were obtained from Yanshen Technology Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou Alpha Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin Bohai Chemical Co., Ltd., and Fuchen (Tianjin) Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. See details in Supplementary Text 1.

Synthesis of COF membranes

The free-standing TbBa-azo membrane was synthesized through liquid-liquid interfacial polymerization (see details in Supplementary Text 2). Briefly, 2,5-diamino-1,4-benzenedithiol dihydrochloride (Ba) was dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Then ultrapure water was added to form an aqueous solution (H2O/DMF = 4/1, v/v). Separately, Tb and nonanoic acid were dissolved in mesitylene. The aqueous and mesitylene solutions were layered in a crystallization dish to form a stable interface and left at room temperature for 3 days, yielding a transparent yellow TbBa-azo membrane at the interface. The membrane was collected, washed, and transferred onto a substrate for characterization. The synthesis procedure for all other COF membranes was identical, and the details can be found in Supplementary Texts 3–5.

Characterization methods

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS50 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). XPS elemental and chemical composition analyses were performed using a Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi system (USA). Carbon-13 solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (13C ssNMR) spectra were collected on a JEOL JNM-ECZ600R/M1 spectrometer. Raman spectra were recorded using a Renishaw Raman spectrometer. Surface morphology of the membrane was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss Sigma 300). Membrane surface topography, roughness, and thickness were measured using an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Dimension ICON, Germany). Surface contact angles were measured with deionized water using the sessile drop method on a Contact Angle Goniometer (Kruss DSA23S, Germany) at room temperature. Surface zeta potential was measured on a SurPASS 3 electrokinetic analyzer (Anton Paar, Austria). N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 apparatus. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was performed on a FEI Talos F200S microscope (Thermo Scientific, USA). Powder XRD analysis was carried out on a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer (Japan). Small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and WAXS) measurements were performed on an Anton Paar SAXSess MC2 instrument. GIWAXS measurements were performed on a Xeuss 2.0 instrument (Xenocs, France). Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted on a TA Instruments Q500. See details in Supplementary Texts 6 and 7.

Nanofiltration performance tests

The nanofiltration (NF) performance of the COF membranes was evaluated at room temperature using a lab-made crossflow NF system and a dead-end filtration setup. The probe solutes tested include inorganic salts, dye molecules, pharmaceuticals, and per- and PFAS. Salt contents were measured using a conductivity meter (SevenCompact™ S230, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). Dyes and pharmaceuticals were quantified using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (UV-1601, Beijing Beifen-Ruili, China). PFAS were quantified using an Xevo TQ-S UPLC-ESI-MS/MS system (Waters Corporation, USA). The TOC of the feed and filtrate was measured using a TOC-L analyzer (Shimadzu, Japan). Unless otherwise specified, all tests were conducted at a pressure of 2 bar with a flow rate of 0.3 L min−1. In each test, the membranes were conditioned at 2 bar for at least 30 min to stabilize the flux before data collection. See details in Supplementary Text 8.

Computational methods

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the potential of mean force (PMF), diffusion behavior of Ba and Pa monomers, layer stacking of COF, hydration behavior within the COF pore channels, transmembrane mass transport, and membrane hydration behavior under acidic conditions were performed using the GROMACS software package version 2020.642. The hydration behavior of water molecules within the COF pore channels and the persistence of thiazole heteroatom exposure were investigated using Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations conducted using CP2K version 2024.143. Meta-dynamics calculations of the driving force for the formation of the protective hydration shell were performed using CP2K version 2024.1 with GFN1-xTB.

All isolated system DFT calculations were performed using ORCA quantum chemistry software version 5.0.344,45. Periodic systems such as the COF unit cells were optimized and subjected to single-point energy calculations using CP2K version 2024.1. Based on the wavefunctions obtained from ORCA and CP2K calculations, additional analyses including electrostatic potential and its area distribution histograms, IGM and IGM based on Hirshfeld partition, reduced density gradient (RDG), nucleophilicity index derived from conceptual DFT, LOL, RESP charges, electron density difference, energy decomposition analysis, transport energy, molecular properties including size dimensions and sphericity, exposure angle, exposure volume derived from atom-in-molecule analysis, linkage bonding energy, and linkage and stacking dissociation energy were conducted using Multiwfn software version 3.8 (dev, 2025-Apr-28)46,47. Gauge-including magnetically induced currents (GIMIC) were calculated using the GIMIC program48,49. The pore size distribution was calculated using Zeo++ version 0.350. To evaluate the transport energy of solutes through the COF pore channels, geometry optimization and single-point energy calculations were performed at the GFN2-xTB level using xTB version 6.7.051. See details in Supplementary Texts 9 and 10.

Data availability

The all data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. Source data for the optimized structures of TbBa-azo and TbPa are present. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Meng, Q.-W. et al. Guanidinium-based covalent organic framework membrane for single-acid recovery. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh0207 (2023).

Wu, D. et al. Engineering bipolar covalent organic framework membranes for selective acid extraction. Angew. Chem. 137, e202503945 (2025).

Liu, X., Lin, W., Bader Al Mohawes, K. & Khashab, N. M. Ultrahigh proton selectivity by assembled cationic covalent organic framework nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202419034 (2025).

Jian, M. et al. Artificial proton channel membrane with self-amplified selectivity for simultaneous waste acid recovery and power generation. ACS Nano 19, 16405–16414 (2025).

Hou, L. et al. Enabling highly selective acid recovery by 3D covalent organic frameworks membrane with sub-nanochannels. J. Membr. Sci. 731, 124242 (2025).

Zhou, L. et al. Covalent organic framework membrane with turing structures for deacidification of highly acidic solutions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2108178 (2022).

Lin, J. et al. Shielding effect enables fast ion transfer through nanoporous membrane for highly energy-efficient electrodialysis. Nat. Wat. 1, 725–735 (2023).

DuChanois, R. M. et al. Membrane materials for selective ion separations at the water–energy nexus. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101312 (2021).

Kim, J., Kim, J. F., Jiang, Z. & Livingston, A. G. Advancing membrane technology in organic liquids towards a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 8, 594–605 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Enabling an ultraefficient lithium-selective construction through electric field–assisted ion control. Sci. Adv. 11, eadv6646 (2025).

Lee, T. H. et al. Microporous polyimine membranes for efficient separation of liquid hydrocarbon mixtures. Science 388, 839–844 (2025).

Côté, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

Tan, K. T. et al. Covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 3, 1 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Carbon dioxide capture from open air using covalent organic frameworks. Nature 635, 96–101 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Reconstructed covalent organic frameworks. Nature 604, 72–79 (2022).

Gruber, C. G. et al. Early stages of covalent organic framework formation imaged in operando. Nature 630, 872–877 (2024).

Bao, S. et al. Randomly oriented covalent organic framework membrane for selective Li+ sieving from other ions. Nat. Commun. 16, 3896 (2025).

Gao, X. & Ben, T. Chiral substrate-induced chiral covalent organic framework membranes for enantioselective separation of macromolecular drug. Nat. Commun. 16, 5210 (2025).

Tang, J. et al. Interface-confined catalytic synthesis of anisotropic covalent organic framework nanofilm for ultrafast molecular sieving. Adv. Sci. 12, 2415520 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Self-standing and flexible covalent organic framework (COF) membranes for molecular separation. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1110 (2020).

Wu, C. et al. Advanced covalent organic framework-based membranes for recovery of ionic resources. Small 19, 2206041 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Solvent-responsive covalent organic framework membranes for precise and tunable molecular sieving. Sci. Adv. 10, eads0260 (2024).

Kang, C. et al. Interlayer shifting in two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12995–13002 (2020).

Yuan, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks for membrane separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2665–2681 (2019).

Qian, C. et al. Imine and imine-derived linkages in two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 881–898 (2022).

Cusin, L., Peng, H., Ciesielski, A. & Samorì, P. Chemical conversion and locking of the imine linkage: enhancing the functionality of covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. 133, 14356–14370 (2021).

Meng, Q.-W. et al. Enhancing ion selectivity by tuning solvation abilities of covalent-organic-framework membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2316716121 (2024).

Lai, Z. et al. Covalent–organic-framework membrane with aligned dipole moieties for biomimetic regulable ion transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2409356 (2024).

Meng, Q.-W. et al. Optimizing selectivity via membrane molecular packing manipulation for simultaneous cation and anion screening. Sci. Adv. 10, eado8658 (2024).

Zheng, S. et al. Quantitative skeletal-charge engineering of anion-selective COF membrane for ultrahigh osmotic power output. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 15777–15786 (2025).

Wu, T. et al. Imine-linked 3D covalent organic framework membrane featuring highly charged sub-1 nm channels for exceptional lithium-ion sieving. Adv. Mater. 37, 2415509 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Synthesis of single-crystalline sp2-carbon-linked covalent organic frameworks through imine-to-olefin transformation. Nat. Chem. 17, 226–232 (2025).

Liu, C.-H. & Perepichka, D. F. Bilayer covalent organic frameworks take a twist. Nat. Chem. 17, 471–472 (2025).

Liu, R. et al. Harvesting singlet and triplet excitation energies in covalent organic frameworks for highly efficient photocatalysis. Nat. Mater. 24, 1245–1257 (2025).

Yan, R. et al. A thiazole-linked covalent organic framework for lithium-sulphur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302276 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Robust thiazole-linked covalent organic frameworks with post-modified azobenzene groups: photo-regulated dye adsorption and separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401895 (2024).

Hou, Y. et al. Rigid covalent organic frameworks with thiazole linkage to boost oxygen activation for photocatalytic water purification. Nat. Commun. 15, 7350 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Metal-incorporated covalent organic framework membranes via layer-by-layer self-assembly for efficient antibiotic desalination. Desalination 600, 118537 (2025).

Zhou, L. et al. Ultrathin cyclodextrin-based nanofiltration membrane with tunable microporosity for antibiotic desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 715, 123504 (2025).

Bai, Y. et al. Microstructure optimization of bioderived polyester nanofilms for antibiotic desalination via nanofiltration. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg6134 (2023).

Guo, Q. et al. Enhancing the interfacial interactions in PVDF/COF composite nanofiltration membranes for efficient antibiotic separation. Composites Communications 58, 102507 (2025).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: An electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: Efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1327 (2018).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Jusélius, J., Sundholm, D. & Gauss, J. Calculation of current densities using gauge-including atomic orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 3952–3963 (2004).

Fliegl, H., Taubert, S., Lehtonen, O. & Sundholm, D. The gauge including magnetically induced current method. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 20500–20518 (2011).

Willems, T. F. et al. Algorithms and tools for high-throughput geometry-based analysis of crystalline porous materials. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 149, 134–141 (2012).

Bannwarth, C. et al. Extended tight-binding quantum chemistry methods. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 11, e1493 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22576109 to G.H.), the Tianjin Applied Basic Research Diversified Investment–Urban Fire Protection Project (Grant No. 24JCQNJC00010 to G.H.), the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation Project (Grant No. 24JCYBJC01550 to G.H.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (040-63253198 to G.H.). Special thanks are also made to other members of the Han Gang Research Lab for their helpful suggestions related to materials characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H. proposed and supervised the project. Y.L. and S.F. designed and conducted the experiments and analyzed the experimental results. Y.L., J.T., and M.T. participated in the membrane structural characterization. Y.L. and S.F. conducted the molecular simulations. Y.L., S.F., F.Z., Z.P., J.Z., and G.H. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Teng Ben, Qi Sun and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, Y., Fang, S., Tang, J. et al. Thiazole-conjugated covalent organic framework membranes enable ultraselective molecular desalination under strongly acidic conditions. Nat Commun 17, 1424 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68171-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68171-9