Abstract

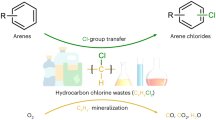

Chlorine, a crucial basic chemical, is primarily produced by the electrolysis of chloride-containing brines, a highly energy-intensive process with a substantial carbon footprint. Notably, concentrated chloride-containing brines, e.g., acidic wastewater, desalination wastewater, seawater, possess significant osmotic energy, which can be harnessed using membrane-based diffusion cells. Considering this, we here present a spontaneous chlorine production method by using the inherent energy and chloride ions present in these brines. The method is first demonstrated with simulated acidic wastewater because in industry, diffusion cells are already widely used to recycle waste acid. Sulfonated covalent-organic framework membranes are employed to facilitate the diffusion of protons and reject multi-valent cations, purifying acid and avoiding side reactions on the anodes. Consequently, our method simultaneously recovers acid, produces hydrogen and chlorine without consuming external energy. We also validate the general applicability of the method with simulated desalination wastewater. Since our method is compatible with the diffusion-based industrial processes, it holds significant promise for facile, scalable implementation. We also expect the method to be extended for the spontaneous production of other crucial chemicals such as ammonia from nitrate-containing brines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chlorine (Cl2) is a base chemical for our modern industry. Each year, tens of millions of tons of chlorine are consumed1,2. Over 95% of chlorine is produced by the electrolysis of chloride-containing brines, consuming around 100–200 TWh of electricity each year, which accounts for a few percent of the world’s electricity generation3. During the last decades, great efforts have been made to increase the energy efficiency of the chlorine production process, e.g., by developing anode materials to improve the charge yield4. Such efforts experienced limited success, since the charge yield of the current chlorine production process is already >95%.

We note that the two crucial elements of the chlorine production process are the energy and chloride ions, and both elements naturally exist in many brines, e.g., seawater, desalination wastewater, industrial waste acid, and pharmaceutical wastewater. The concentrated Cl− ions in these brines create high osmotic potential when discharged into lower salinity water (river water, lake water, etc.), which can be harvested to generate electricity5,6,7. For example, over 50 billion tons of desalination wastewater are discharged annually, typically with a Cl− concentration exceeding 1 M8. Each ton releases osmotic energy of over 0.2 kWh when mixed with seawater, meaning that the desalination wastewater could generate ~10 TWh of electricity per year9. This is sufficient to produce up to 4.5 million tons of chlorine using the Cl− ions in the brine. The mixing of seawater and river water releases even more energy, although the harvesting is also more challenging5,6. In addition, millions of tons of industrial waste acid containing concentrated Cl− ions are generated each year10. Although these brines contain much less energy in total, they present a high possibility for scalable chlorine production, since in our current industry, waste acid is often recycled using the diffusion dialysis process11, whose set-up is identical to that of the osmotic power generation that also utilizes the diffusion of protons. In fact, previous studies in our group and other groups have demonstrated the integration of osmotic energy harvesting and water treatment or resource (e.g., acid) recovery processes12,13,14,15,16,17. All these facts suggest that chlorine could be massively produced from brines without consuming external energy.

Considering this, we here demonstrate how chlorine can be spontaneously produced from chloride-containing brines, including simulated industrial waste acid and desalination wastewater (schematically illustrated in Fig. 1). We noticed that when industrial waste acid is used, the chlorine production may suffer from the reduction of heavy metal ions on the anode. This problem is addressed by using a covalent-organic framework (COF) membrane, which allows fast proton transport and rejects heavy metal ions. To sustain the chlorine production and couple the transport of the protons, we leveraged the reversible electrochemical reaction of Ag/AgCl electrodes to selectively extract Cl− ions from the waste acid12,13,18. The system not only produces chlorine but also recycles acid as a valuable chemical product, as well as generating hydrogen during the electrolysis of HCl. The hydrogen and chlorine production rates reached approximately 150 L m−2 h−1 and could be continuously sustained for at least 7 days. Furthermore, we demonstrated the general applicability of our method by showing the chlorine production from simulated desalination waste brines.

a In the conventional chlor-alkali system, the electrolysis of concentrated brine requires a continuous supply of external electrical power to produce chlorine. b The spontaneous chlorine production system, in contrast, operates without external electrical power. The integrated system consists of multiple units connected in series. Acidic wastewater containing concentrated protons and Cl− ions was used. The protons and Cl− ions selectively migrate from the feed reservoirs containing waste acid to the permeate reservoirs containing lower-concentration recovered acid through the proton-selective membranes and Ag/AgCl electrodes, respectively. On the Ag/AgCl electrodes, electrochemical reactions occur, consuming Cl− in the feed reservoirs and releasing Cl− in the permeate reservoirs, effectively transporting Cl−. The electrochemical reactions and the proton diffusion generate an electrical potential. As a result, on the leftmost anode, chlorine is spontaneously produced, and on the rightmost cathode, spontaneous hydrogen evolution occurs.

Results

Design of the system

As shown in Fig. 1a, the conventional chlor-alkali industry uses a cation ion exchange membrane to electrolyze concentrated brine for chlorine production. This process relies on a continuous supply of electrical energy, leading to significant power consumption. In contrast to the conventional chlor-alkali industry, which requires external electrical power, our system operates spontaneously and does not rely on energy input (Fig. 1b).

The system consists of serially connected units for power generation. Each unit is a two-compartment electrochemical cell whose feed reservoir was filled with waste acid, and the permeate reservoir was filled with fresh acid recovered from the waste acid. For practical relevance, the waste acid contained various heavy metal ions (e.g., Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+) and pollutants (tetracycline hydrochloride, levofloxacin hydrochloride). The reservoirs were connected to Ag/AgCl electrodes and separated by proton-selective COF membranes. As protons diffuse from the waste acid reservoir to the fresh acid reservoir, the same number of electrons would flow through the electrodes to maintain charge balance. This induces the reversible electrochemical reaction, AgCl + e− ⇌ Ag + Cl−. The net outcome is that both protons and Cl− are ions that are selectively transported from the waste acid reservoir to the fresh acid reservoir, generating electricity and recovering acid. By periodically switching the electrodes and refreshing the reservoirs, the system could be continuously operated12,13,18.

To produce chlorine, the left-most electrode illustrated in Fig. 1 was switched to a graphite electrode, and the right-most electrode was a Pt electrode. Note that when the waste acid contains contaminants that can be easily oxidized, the waste acid in the left-most reservoir should be exchanged with the recycled pure acid. For many industrial waste acids, there is no such problem since the heavy metal ions are typically already oxidized. During the chloride production, the recycled protons are reduced on the Pt electrodes, generating hydrogen, which is also a high-value product. In this system, the chlorine evolution reaction (CER) and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) are spatially isolated, avoiding the safety problem caused by the mixing of gases.

High proton selectivity of the membrane

To ensure the purity of the recycled acid and thus suppression reduction of the metal ions on the HER electrode, the membrane should have high proton selectivity. Commercial ion-exchange membranes used to recycle acid typically only have a selectivity of up to a few tens. Our previous work demonstrated that a device made of TpPa–SO3H, a covalent-organic framework material with dense sulfonic groups, exhibits high proton selectivity against all other chemical species19. The sulfonic groups form hydrogen bonding networks with the help of water molecules and thus enable fast proton hopping. Here, we fabricated the material as a membrane (Fig. 2a) by casting its monomer solutions (1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol in n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone and 2,5-diaminobenzenesulfonic acid in dimethyl sulfoxide) on a glass substrate and allowed them to evaporate (Supplementary Fig. 1). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showed the crack-free surface (Supplementary Fig. 2). The thickness of the membrane was typically 10 μm (Fig. 2a, inset). The homogeneity of the surface was also suggested by the uniform distribution of C, N, O, and S elements (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR), Raman, and solid-state carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) confirmed the chemical structure of the TpPa–SO3H (Supplementary Fig. 4). Transmission electron microscope (TEM) revealed the 3.49 Å interlayer spacing (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 5). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the membrane exhibited a strong peak at 4.9° (Fig. 2c). Thanks to the abundant sulfonic groups on the COF pores, the membrane carries negative surface charge and exhibited hydrophilicity (Supplementary Fig. 6), which is favored for fast proton transport. Additionally, it displayed high thermal stability and high resistance to both acidic and alkaline conditions (Supplementary Fig. 7), some other properties important for practical use.

a Optical image of the synthesized TpPa–SO3H COF membrane. Inset: cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy image, showing a membrane thickness of approximately 10 µm. The experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results. b Transmission electron microscopy image of the membrane, showing the interlayer spacing. The experiments were repeated three times independently with similar results. c Measured and simulated X-ray diffraction pattern of the membrane, confirming the COF structure. Inset: molecular structure of the TpPa–SO3H COF. d Schematic illustration of the set-up to measure the selectivity of the membrane using the diffusion dialysis method. e Concentration of permeated protons and various metal ions (Al3+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+) in response to diffusion time. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. f Magnified view of time-dependent concentration of metal ions. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. g Calculated proton selectivity against various metal ions. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. h, i UV-Vis absorbance spectra of tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH) (h) and levofloxacin hydrochloride (LFH) (i) in the feed and permeate reservoirs, suggesting the almost perfect rejection of organic pollutants by the membrane. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The selectivity of the membrane was assessed with diffusion dialysis experiments using a two-compartment electrochemical cell, since the osmotic power was generated by the diffusion of protons in our work. As shown in Fig. 2d, the feed reservoir was filled with a complex solution containing protons (0.1 M) and various cations, including Al3+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, each cation having a concentration equal to that of the protons. The permeate reservoir was initially filled with deionized (DI) water. The permeability of protons was measured by continuously recording the pH value of the permeate reservoir, and the those of metal cations were measured by recording their concentrations with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). During 150 min of diffusion, the proton concentration in the permeate reservoir increased almost linearly with time, allowing us to easily calculate the permeability by fitting the data points with a line (Fig. 2e). The permeabilities of metal cations were dramatically lower than that of the protons. Magnified view in Fig. 2f suggests that the diffusion of metal cations also followed the linear behavior. The H+/Al3+, H+/ Mn2+, H+/Fe3+, H+/Co2+, H+/Ni2+, H+/Cu2+, and H+/Zn2+ selectivities were calculated to be 673, 248, 3767, 224, 228, 201, and 225, respectively (Fig. 2g), far superior to commercial ion-exchange membranes. To understand the proton/heavy metal ion selectivity performance, we further conduct characterization of the TpPa–SO3H membrane’s pore size or its high heavy metal ion adsorption capacity (Supplementary Figs.8, 9). The low N2 adsorption volume and limited heavy metal ion adsorption capacity suggest the presence of small pores. In real industrial waste acid, the concentration of metal cations is typically much lower than that of protons. This means that in the permeate reservoir, the metal cation concentration would be negligible, avoiding side reactions on the HER electrode, such as metal ion deposition (Supplementary Fig. 10).

In practice, the wastewater may also contain organic pollutants. Our membrane can almost completely block them since they have a much larger size than the metal cations. Using tetracycline hydrochloride and levofloxacin hydrochloride as model pollutants (100 ppm for each in the feed reservoir), we conducted diffusion experiments and detected none of them in the permeate reservoir after 12 h using a ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Fig. 2h, i).

Co-transport of Cl− and proton, and its importance for continuous operation and high transport rate

To ensure the continuous operation of the system, the Cl− ions and protons must transport at the same rate from the waste acid reservoir to the recycled acid reservoir, since otherwise the charge balance would break down. However, they should not transport together through the membranes so as not to cancel the net ionic current. The effective transport of Cl− ions was realized by the reversible electrochemical reaction of Cl− ions with the electrodes (Fig. 3a). The membrane, on the other hand, only allows the transport of protons while rejecting Cl− ions. This is crucial to increasing the performance of the system. The Cl− reaction creates a redox potential while the selective diffusion of protons creates an additional diffusion potential, and these potentials can add up, enhancing the power generation performance and increasing the transport rate of protons and Cl− ions (Supplementary Fig. 11).

a Schematic illustration of selective proton transport across the COF membrane and effective Cl− transport via Ag/AgCl electrodes. b Concentration of the permeated protons and Cl− ions over time, tested using a two-compartment electrochemical cell with Ag/AgCl electrodes inserted (inset), confirming their synchronized transportation. Feed reservoir contained 5 M HCl. Permeate reservoir contained DI water. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. c Optical images of the Ag/AgCl electrodes, demonstrating the reversible redox electrode reactions. Feed reservoir contained 5 M HCl. Permeate reservoir contained 0.5 M HCl. d XRD patterns of the Electrode A and Electrode B, confirming that their surfaces were covered with Ag and AgCl, respectively. e Cycling test. The electrodes were switched every 10 min. In each cycle, the transferred charge across the electrodes maintained almost the same, confirming the high reversibility of the electrochemical reaction. Insert: schematic diagram of the test setup. f The coupled transport of Cl− via the electrodes maintains the charge balance and generates additional electrical potential, which in turn enhances the transport rate. The proton transport in the presence of the Ag/AgCl electrodes was much higher than that without the presence of Ag/AgCl electrodes. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. Insert: schematic diagram of the test setup. g I–V curves obtained at varying HCl concentration ratios (concentration of the permeate reservoir fixed at 0.01 M HCl). Intercept on the voltage axis (shown in shadings) is the opposite of the open-circuit voltage (VOC). h Theoretical maximum open-circuit voltages (redox potential contributed by Cl− + diffusion potential contributed by protons) and measured open-circuit voltage in response to HCl concentration ratio, confirming the importance of the co-transport of protons and Cl−, as well as the almost perfect proton selectivity of the membrane against anions. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As a verification of the effective Cl− transport through the electrodes, we inserted a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes in a two-compartment cell. The feed reservoir contained 5 M HCl, and the permeate reservoir contained DI water. The concentration of protons and Cl− in the permeate reservoir was then measured with time. Fig. 3b shows that Cl− concentration increased linearly with time and maintained the same with that of the protons throughout the experiment to satisfy the charge balance requirement.

As the redox reactions proceed, the Cl on the cathode would be gradually depleted, and the anode would be covered by excess AgCl, hindering further Cl− transport. To sustain the reaction, the anode and cathode Ag/AgCl can be switched. As a verification, we used a two-compartment cell whose feed reservoir was filled with 5 M HCl and the permeate reservoir with 0.5 M HCl. Electrode B (Fig. 3c, now inserted in the permeate reservoir) turned white after 30 min, due to the consumption of AgCl on the electrode (Supplementary Fig. 12). However, after we switched the electrodes for the two reservoirs, Electrode B turned black again in 30 minutes, while the other electrode (Electrode A) turned white, suggesting the reversibility of the reaction. The XRD patterns confirmed that electrode A was entirely converted to Ag, while Electrode B displayed strong AgCl peaks (Fig. 3d).

Indeed, after each electrode switching, the ion transport performance can be recovered. As a verification, we tested two-compartment cells containing 5 M /0.5 M NaCl or 5 M/0.5 M HCl. For both cases, we switched the electrodes every 600 s and measured the transferred charges by recording the ionic current with time (Supplementary Fig. 13). Fig. 3e shows that the transferred charge in each cycle kept almost the same, confirming the stability in repeated tests. For HCl, the amount of the transferred charge is larger than that for NaCl due to the higher permeability of protons. Furthermore, in a 100-cycle test, the performance can still be robustly maintained with periodic electrode regeneration (Supplementary Fig. 14).

The diffusion of protons generates a diffusion potential, Ediff, and the electrochemical reaction of Cl− generates a redox potential Eredox. These potentials can add up, which in turn also facilitates the transport of protons and Cl−. To confirm so, we used the 5 M HCl and 0.5 M NaCl solutions to fill the feed and permeate reservoirs, respectively. Fig. 3f shows that without Ag/AgCl electrodes inserted, the proton permeability was 29.6 mol m−2 h−1. However, with electrodes inserted into the reservoirs, it increased significantly to 90.4 mol m−2 h−1. Such permeability is at least 1 to 2 orders of magnitude higher than common commercial ion-exchange membranes20, and is enabled by the fast proton hopping on hydrogen-bonded networks of the membrane, as we demonstrated in our previous work19. The Cl− would have the same permeability as required by the charge balance.

Based on the Nernst equation, we can calculate the total electrical potential as,

where R, T, F, t+ and a represent the gas constant, temperature, Faraday constant, cation transference number and activity of ions, respectively. The subscript feed and perm denote the feed reservoir and permeate reservoir, respectively. E can be measured as the open-circuit voltage (VOC) of the power generator, and the maximum E is reached when the proton selectivity of the membrane against anions is perfect, i.e., t+ = 1.

We then varied the afeed/aperm by varying the concentration ratio of the feed reservoir and permeate reservoir from 5 to 100 and measured the VOC by recording sweeping current-voltage curves. Fig. 3g, h show that the measured values agreed well with the theoretical maximum values, confirming the synergistic role of Ediff and Eredox, as well as the almost perfect proton selectivity (Supplementary Fig. 15).

In many previous osmotic power generation works, the selective transport of Cl− ions was carried out by anion-exchange membranes (set-up illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 16)21. However, these membranes have low Cl− selectivity against protons, significantly limiting the osmotic power generation performance. Supplementary Fig. 17 shows that when a commercial anion-exchange membrane was used to transport Cl−, the generated potential was much lower than that when Ag/AgCl electrodes were used.

Power generation performance

Obviously, the osmotic power generation performance determines the chlorine generation performance. A high osmotic power density requires high proton permeability and high proton/anion selectivity, which our membrane already has. To assess the power density, we used a two-compartment cell and established a variety of concentration ratio, ranging from 5 to 500, by filling feed reservoir with 5 M HCl and the permeate reservoir with different concentrations of HCl (Supplementary Fig. 18). The test area (S) of the membrane was set at 7 mm2, larger than most of the previous osmotic power generation membranes. Then we measured current (I) with an external load of varying resistance (R) to calculate the output power density (P)22,23,24, P = I 2R/S (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 19). The maximum P (Pmax) is typically reached at a moderate R. Fig. 4b shows that Pmax increased with the decrease of the concentration ratio when the concentration ratio is larger than 10, due to the increasing current (Supplementary Fig. 20) induced by the decreasing reservoir resistance of the permeate reservoir. For a lower concentration ratio, Pmax decreased due to the lower Voc (Supplementary Fig. 21). The maximum Pmax reached 55 W m−2 at the moderate concentration ratio of 10. Meanwhile, the high output power density could be maintained for over 15 days without obviously decreasing (Supplementary Fig. 22).

a Power density as a function of external resistance at varying HCl concentration ratios. b Maximum output power densities obtained at varying HCl concentration ratios. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. Insert: schematic diagram of the power generation setup. c Comparison of the maximum output power density with previously reported membranes (see also Supplementary Data 1). d Power density as a function of external resistance before and after introducing heavy metal cations (100 mM for each cation) into the feed reservoir. e Concentration of heavy metal ions in the permeate reservoir after 20 min of power generation and corresponding ion permeation rate, confirming the negligible metal ion leakage. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent tests. Insert: H+ and Cl− permeation rate estimated from the current. f Output power density before and after introducing organic pollutants (100 ppm tetracycline hydrochloride and 100 ppm levofloxacin hydrochloride) into the feed reservoir, showing that organic pollutants do not significantly affect power output. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We note that previous studies often tested a microscopic area23, which obviously has limited practical relevance. It is known that an extremely small area usually results in artificially increased Pmax23,25. For a fairer comparison with previous studies, we tested a range of membrane areas (Supplementary Fig. 23). In all cases, the Pmax was significantly higher than those of the previous osmotic generators obtained at the same test are22,23,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Data 1). This highlights the advantage of the high proton permeability and selectivity of the membrane, as well as the advantage of generating osmotic power with acidic water.

To put the results into the content of practical application, we added heavy metal ions, including Al3+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+, 100 mM for each cation, into the feed reservoir to simulate real waste acid. We found that Pmax did not decrease. Instead, it creased to 67 W m−2 possibly due to the elevated conductivity of the feed reservoir (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 24). Importantly, the concentration of the heavy metal ions in the permeate reservoir was at least 4 orders of magnitude lower than that of the protons, confirming the negligible metal ion leakage (Fig. 4e). We also added tetracycline hydrochloride and levofloxacin hydrochloride (100 ppm for each) into the feed reservoir. Still, Pmax did not decrease (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 25).

Two positively charged organic pollutants, Rhodamine B and Crystal Violet, were used to further evaluate the anti-fouling capability of the membrane (Supplementary Fig. 26). The transport of pollutants was also almost completely blocked, making the membrane anti-fouling (Supplementary Fig. 27).

Spontaneous chlorine production

In this work, we used a Pt electrode for the HER and a graphite electrode for the CER due to its high acid resistance. Before the chlorine production experiments, we assessed the performance of the electrodes using a conventional three-electrode system. As shown in Fig. 5a, the Pt electrode required -0.15 V vs. the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) to reach a current density of 100 mA cm−2 for the HER in 0.5 M HCl, whereas the graphite electrode required 1.54 V vs. RHE to drive the CER at the same current density in 5 M HCl. We further performed a two-electrode electrolysis test, and the I-V characteristic curve indicates that a voltage of 1.68 V is required to attain a current density of 100 mA cm−2, which aligns with the polarization curve obtained from the three-electrode setup (Fig. 5b). The slight deviation may be attributed to the osmotic potential and membrane resistance contributed by the TpPa–SO3H membrane.

a Polarization curves (three-electrode configuration) showing the electrochemical performance: platinum (Pt) electrode in 0.01 M HCl (blue), platinum electrode in 0.5 M HCl (orange), and graphite electrode in 5 M HCl (light blue). Shadings represent the working electrode potential at a current density of 100 mA cm−2. Inset: schematic diagram of a three-electrode system. b Two-electrode polarization curve tested with graphite (anode) and Pt (cathode) electrodes. The shading shows a cell voltage of approximately 1.68 V at a current density of 100 mA cm−2. Inset: schematic diagram of a two-electrode system. c Faradaic efficiency of chlorine evolution reaction at various current densities. Error bars represent the standard deviation from four independent tests. d Optical image of the device composed of 18 serially connected power generation units for spontaneous chlorine and hydrogen production. e Linear correlation between total VOC and the number of units. Inset: schematic diagram for VOC measurement (f, g). Produced volume of H2 (f, orange circles) and Cl2 (g, blue line) in response to time. h Long-term stability test over seven days, showing robust current density (orange line) and hydrogen production rates (blue squares). i Comparison of electricity consumption and associated carbon emissions between our method (red, ~0 consumption and emissions) and traditional chlorine production methods. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Chlorine production often suffers from the competition between oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and CER, which affects the faradaic efficiency (FE). However, we note that OER is highly unfavorable in the extremely low-pH environments (Supplementary Fig. 28). Indeed, we quantified the produced Cl2 using the iodometric titration method at various current densities to calculate the FE51,52. The results, presented in Fig. 5c, showed a high FE of 98.4% for the CER at 10 mA cm−2. Even at a very high current density of 100 mA cm−2, the FE reached 90.7%.

Equation 1 tells us that each osmotic power generation unit can produce a maximum of 0.184 V when 5 M/0.5 M HCl was used for chlorine production. This means that 8 units are required to initiate the spontaneous production of chlorine. Considering the electrochemical overpotential, internal resistance voltage drops, we tested serially connected units from 8 to 18 (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 29). Then, the terminal electrodes of the serial osmotic generators were replaced with a graphite electrode and a Pt electrode. The Ag/AgCl electrodes of the feed and permeate reservoirs were switched every 600 s for continuous operation. The hydrogen generated on the Pt electrode was collected using the water drainage method, while the chlorine production rate was calculated from the ionic current data. Obviously, the Voc of the system increased linearly with the number of units in series, reaching 2.95 V when the unit number was 18 (Fig. 5e), resulting in an enhanced chlorine production rate. When the number of units were lower, the reaction was either slower or could not be initiated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 30, the average current density was 36.8 mA cm−2, meaning that the FE would be larger than 97 % (the FE at 50 mA cm−2). Figure 5f, g show that the hydrogen and chlorine production rate reached ~154 L m−2 h−1 along with nearly 100% HER Faraday efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 31). Such a production rate can be maintained for at least 7 days (Fig. 5h).

To evaluate the system’s sensitivity, we tested various feed solution concentrations. As the concentration ratio increases, the power density increases gradually. For a fixed concentration ratio, the power density increases with the increase of concentration due to the reduced reservoir resistance (Supplementary Figs. 32, 33). We also investigated the relationship between the membrane proton selectivity and system performance. The results show that membranes with high proton/Cl− selectivity exhibit superior energy conversion performance and increased chlorine production rates (Supplementary Figs. 34, 35). Furthermore, the high proton/heavy metal ion is critical for sustained operation, as inadequate rejection led to rapid side reactions at the cathode (Supplementary Fig. 36).

Extending to other chloride-containing brines

Obviously, all chloride-containing brines can be used to harvest the osmotic energy and produce chlorine if a brine with lower salinity is readily available. For the waste acid, the lower salinity brine is the recycled acid. For other brines, natural water could be used as the low salinity brine. For example, the waste brines of the desalination plant have higher salinity (typically > 1 M Cl−) than seawater, and they are often discharged into seawater, providing the foundation for osmotic power generation (Supplementary Fig. 36).

We found that a high power density of > 6 W m−2 can be achieved using simulated waste desalination brine generated by the membrane distillation method (5 M NaCl)9 and simulated seawater (0.5 M NaCl) using a TpPa–SO3H membrane (Supplementary Fig. 37). When combined with industrial waste heat, the power density could be further improved to 8.4 W m−2(Supplementary Fig. 38). The power density is lower than that in Fig. 4c, due to the fact that our membrane was optimized for proton transport. For chlorine production, we used the dimensionally stable anode (DSA) electrode as the anode, which was widely used in the chlor-alkali industry because of its good stability and chlorine selectivity. The high selectivity of the electrode was further confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 39. The chlorine and hydrogen production rates of the integrated system reached approximately 12 L m−2 h−1, which is lower than that produced using waste acid, but confirms the versatility of our spontaneous chlorine production method (Supplementary Fig. 40).

Discussion

We demonstrated the spontaneous chlorine production from waste brines by utilizing their abundant Cl− ions and the osmotic energy carried by the ions. Compared to traditional chlorine production, our method requires no electricity input and thus has almost no carbon emission considering that the carbon emission of chlorine production primarily comes from the energy consumption (Fig. 5i, Supplementary Table 1), while also significantly reducing production cost (see Supplementary Note 1). Owing to its high compatibility with the industrial diffusion-dialysis processes used for waste acid recovery, we expect our method to be widely deployable.

The modular design of our system allows scalable applications by connecting multiple units in series or parallel (Supplementary Fig. 42). Further improvements could be achieved by reducing electrode spacing53 and automating the electrode switching13. Regarding chlorine handling, we can seal the anode compartment and maintain a slight negative pressure to prevent chlorine leakage, ensuring both safety and directed transport to storage units54. This work used a reported membrane for the demonstration of general applicability, but novel membranes could enhance the performance. Obviously, further improvement of the chlorine generation performance could be realized by engineering the osmotic energy generation membranes6,50,55, or by optimizing electrode catalysts56,57,58,59. Beyond chlorine production, we expect that our method can also be used for the spontaneous production of other chemicals with brines, e.g., electrochemical synthesis of ammonia from nitrate-containing brines60,61, contributing to the reduction of the carbon emission of some chemical engineering industries.

Methods

Preparation of the TpPa–SO3H membrane

0.064 g (0.304 mmol) 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol (Tp) and 0.086 g (0.456 mmol) 2,5-diaminobenzenesulfonic acid (Pa-SO3H) were dissolved in 3 mL N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), respectively. After sonication at room temperature for 20 min, the two solutions were mixed and stirred thoroughly. Then the mixture was sonicated for 20 min to remove the solution bubble. The mixed solution was cast onto a clean glass slide (10 cm × 10 cm) and kept on the heating plate at 60 °C for 3 days to form the TpPa–SO3H. The self-standing COF membranes could peel off from the glass slides by put into water. The membrane was washed thoroughly with NMP, DMSO and deionized water to remove residual monomer fragments before it dried in the oven at 60 °C. Then the membrane was cut into various sizes for further characterization and tests.

Preparation of the Ag/AgCl electrode

The Ag/AgCl electrode was fabricated via a chemical oxidation method. Silver plates (8 mm × 30 mm) were immersed in sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 min, during which hypochlorite reacted with the silver surface to form a layer of silver chloride. The initially bright silver plates turned glossy gray upon conversion. Following the reaction, the electrodes were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to remove residual hypochlorite. The resulting Ag/AgCl electrodes were then used for subsequent tests.

Material characterization

Scanning electron microscopic images were taken with a Hitachi S-4800 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. The nanosheets were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM F200). Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were carried out in the 2θ range of 3° to 40° at room temperature using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffraction diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5147 Å). The surface chemical properties were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR, Bruker Vertex 70 v), Raman spectrometry (Nicolet5700) and X-ray photoelectron spectrum (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-Alpha). The solid-state 13C NMR spectra were recorded on an AVANCE Ⅲ HD 500 MHz NMR spectrometer with cross-polarization magic angle-spinning (CP-MAS). The absorption spectra were recorded on Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-3900, Japan). The contact angles of the membranes were measured by a Contact Angle Surface Analyzer (LSA 100) at room temperature. The Anton Paar SurPASS is used to determine the Zeta potential of the membrane surface. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a STA8000 thermogravimetric analyzer under a N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

Diffusion experiment

To investigate the ion transport behavior, the Ion selectivity tests were performed by concentration-driven diffusion using a self-made H-type device. The COF membrane was tightly mounted between two reservoirs, with one reservoir filled with 10 mL electrolyte feed solution and the other reservoir filled with 10 mL deionized water as the starting permeate solution. The concentration of cations was measured by Inductively Coupled Plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent 7850), the proton concentration was measured with a pH meter (LAQUA F-71) and the other anion concentrations were determined by Ion Chromatography (IC, ECO).

Adsorption of heavy metal ions and positively charged pollutants

The adsorption of heavy metal ions by TpPa–SO3H membranes was carried out using a 50 mL mixed solution containing 0.001 M of each metal ion: Al³⁺, Mn²⁺, Fe³⁺, Co²⁺, Ni²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Zn²⁺. A known mass of the TpPa–SO3H membrane was immersed in the initial metal ion solution. The system was maintained under magnetic stirring at 600 rpm for 12 h to facilitate the adsorption process. Following this, the concentration of metal ions in the solution was measured to determine the extent of metal ion adsorption onto the membrane. The amount of metal ions adsorbed was calculated using the following formula:

where Q represents the adsorption capacity (mg/g), V is the volume of the solution (mL), c0 is the initial concentration of metal ions (mg/L), ct is the concentration after adsorption (mg/L), and m is the mass of the TpPa–SO3H membrane (g).

The adsorption experiments for positively charged organic pollutants were performed similarly, using 50 ppm solutions of Rhodamine B and Crystal Violet, respectively, as model pollutants. The adsorption process was conducted under the same experimental conditions as described for the heavy metals, with a stirring speed of 600 rpm for 12 h. After adsorption, the concentrations of Rhodamine B and Crystal Violet in the solution were quantified by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, allowing for the determination of the adsorption capacity of the TpPa–SO3H membrane.

Osmotic energy conversion setup

The COF membrane was placed between two reservoirs. A pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes (8 mm × 40 mm) were employed as the work electrode. The effective test area for energy harvesting was 7.06 mm2 if without further explanation. The VOC and ISC were measured from the I-V curve tests, and the sweep voltage was from −1 V to 1 V. The equivalent circuit of the experimental setup can be represented by Supplementary Fig. 11, VOC, Eredox, Ediff, and Rmem represent the measured potential, the redox potential generated by the unequal potential drop at the electrode-solution interface and the diffusion potential contributed by the ion-selective membrane, and the internal resistance of the membrane, respectively. The measured VOC actually consists of two parts (i.e., Eredox and Ediff). In our work, the salt bridges were used to eliminate the redox potential of the system. Then, the corresponding output power density can be calculated as P = I2R/S, where I, R, and S represent ion current, load resistance and effective testing membrane area, respectively. All the osmotic power generation tests were carried out by Source Meter (Keithley 2450).

For a given concentration ratio, the cation transference number (t+) can be calculated as

where R, T, z, F, γ, cH and cL represent the gas constant, temperature, charge valent, Faraday constant, activity coefficient of ions, high and low ion concentrations, respectively. The activity coefficients used in the calculation are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Measurement of redox potential and diffusion potential

The experimental setup is shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. The measurements were performed using Ag/AgCl reference electrodes under a controlled environment. The system comprised two compartments separated by either a solution interface (for redox potential measurement) or a commercial anion exchange membrane (AEM) (for diffusion potential measurement). The compartments were filled with electrolyte solutions of varying concentrations to establish concentration gradients.

The redox potential of the Ag/AgCl electrode and the diffusion potential of the AEM were determined by recording the I–V curve. The potential was scanned over a range of −1 V to +1 V using a Source Meter (Keithley 2450), with the Ag/AgCl reference electrodes serving as both the working and reference electrodes in high and low-concentration electrolyte solutions. The intercept of the I–V curve on the voltage axis was recorded as the redox potential of the electrode or the osmotic potential of the AEM.

Electrochemical hydrogen evolution and chlorine evolution evaluation

The performance of electrodes was tested on an electrochemical workstation instrument (Biologic SP-300). The experimental setup is based on a conventional three-electrode system, with the working electrode (WE) (Pt, graphite or DSA), while the counter electrode (CE) was a graphite rod. The reference electrode (RE) used in this study was an Ag/AgCl electrode with a salt bridge contain the statured KCl solution. The effective area of the working electrode is 7.06 mm2. The polarization curves were obtained by employing a scanning rate of 10 mV s−1. All the recorded potentials of the polarization curves in this study were without conducting iR compensation and converted to reverse hydrogen electrode (RHE) values based on equation:

Two-electrode electrolysis and faradaic efficiency evaluation

The two-electrode electrolysis and faradaic efficiency evaluation were performed on the Source Meter (Keithley 2450). Within the H-type electrolytic cell, the working electrode (Graphite or DSA) was connected with the anode, while the counter electrode (Pt) was connected with the cathode. The “Voltage sweep” method was conducted to obtain the I–V characteristic curve with the scanning rate of 10 mV s−1.

The faradaic efficiency of chlorine was determined through iodometric titration. First, 50 mL of electrolyte was added to the electrolytic cell. Then the electrolyte was purged with N2 for 10 min. Following this, the “Current bias” method was conducted to maintain the current density from 10 to 100 mA cm-2. After 100 s of tests, the obtained Cl2 was trapped by the immediate addition of an excess amount of potassium iodide (\({{Cl}}_{2}+3{I}^{-}\to {I}_{3}^{-}+{2{Cl}}^{-}\)), and the solution was kept to attain equilibrium. The obtained amount was determined by performing Iodometric titration versus 0.1 mM Na2S2O3 (\({I}_{3}^{-}+2{S}_{2}{O}_{3}^{2-}\longrightarrow 3{I}^{-}+{S}_{4}{O}_{6}^{2-}\)) to calculate the chlorine production in the experiment. The calculation method for chlorine faradaic efficiency was:

Integrated device performance evaluation

In the spontaneous chlorine and hydrogen production system with simultaneous acidic wastewater recovery, a varying number of pairs of units, each equipped with TpPa–SO3H membranes, were connected in series with Ag/AgCl electrodes. Graphite and Pt electrodes were used at both terminals, forming a fully integrated osmotic energy-driven device for chlorine and hydrogen production. 5 M HCl aqueous solution and 0.5 M HCl aqueous solution were injected into each pair of cells to simulate an acidic wastewater recovery system.

For the desalination brine-seawater system, 30 pairs of units were connected similarly, with DSA and Pt electrodes at the respective terminals to generate chlorine and hydrogen. The electrolytes at both ends consisted of 5 M NaCl (pH = 2) and 1 M NaOH, respectively. Additionally, each pair of cells was injected with a 5 M NaCl aqueous solution and a 0.5 M NaCl aqueous solution to simulate a membrane distillation brine-seawater system.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All the raw data relevant to the study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Statista. Market volume of chlorine worldwide from 2015 to 2022, with a forecast for 2023 to 2030 (in million metric tons). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1310477/chlorine-market-volume-worldwide/ (2024).

Zeradjanin, A. R. The era of stable electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 458–459 (2023).

Kermeli, K. & Worrell, E. Energy efficiency and cost-saving opportunities for the chlor-alkali industry. (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, 2025).

Karlsson, R. K. & Cornell, A. Selectivity between oxygen and chlorine evolution in the chlor-alkali and chlorate processes. Chem. Rev. 116, 2982–3028 (2016).

Macha, M. et al. 2D materials as an emerging platform for nanopore-based power generation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 588–605 (2019).

Siria, A. et al. New avenues for the large-scale harvesting of blue energy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0091 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 622–639 (2021).

Jones, E. et al. The state of desalination and brine production: a global outlook. Sci. Total. Environ. 657, 1343–1356 (2019).

Tufa, R. A. et al. Progress and prospects in reverse electrodialysis for salinity gradient energy conversion and storage. Appl Energ. 225, 290–331 (2018).

Agrawal, A. & Sahu, K. K. An overview of the recovery of acid from spent acidic solutions from steel and electroplating industries. J. Hazard. Mater. 171, 61–75 (2009).

Zhang, C. et al. Diffusion Dialysis For Acid Recovery From Acidic Waste Solutions: Anion Exchange Membranes And Technology Integration. Membr. (Basel) 10, 169 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Spontaneous lithium extraction and enrichment from brine with net energy output driven by counter-ion gradients. Nat. Water 2, 1091–1101 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Lithium extraction from brine through a decoupled and membrane-free electrochemical cell design. Science 385, 1438–1444 (2024).

Liang, Q. R. et al. Efficient osmosis-powered production of green hydrogen. Nat. Sustain 7, 628–639 (2024).

Xia, J. et al. Light-augmented multi-ion interaction in mxene membrane for simultaneous water treatment and osmotic power generation. ACS Nano 17, 25269–25278 (2023).

Huang, T. et al. Two-dimensional sodium channels with high selectivity and conductivity for osmotic power generation from wastewater. ACS Nano 17, 17245–17253 (2023).

Jian, M. et al. Artificial proton channel membrane with self-amplified selectivity for simultaneous waste acid recovery and power generation. ACS Nano (2025).

Katan, T. et al. Silver-silver chloride electrodes - surface morphology on charging and discharging. J. Electrochem. Soc. 121, 757–764 (1974).

Li, Q. et al. Covalent organic framework interlayer spacings as perfectly selective artificial proton channels. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 63, e202402094 (2024).

Loza, S. et al. Comparative study of different ion-exchange membrane types in diffusion dialysis for the separation of sulfuric acid and nickel sulfate. Membr. (Basel) 13, 396 (2023).

Rastgar, M. et al. Harvesting blue energy based on salinity and temperature gradient: challenges, solutions, and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 123, 10156–10205 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Advancing osmotic power generation by covalent organic framework monolayer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 622–628 (2022).

Pan, S. et al. Toward scalable nanofluidic osmotic power generation from hypersaline water sources with a metal-organic framework membrane. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 62, e202218129 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Artificial sodium channels for enhanced osmotic energy harvesting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 28038–28048 (2023).

Gao, J. et al. Understanding the giant gap between single-pore- and membrane-based nanofluidic osmotic power generators. Small 15, e1804279 (2019).

Cao, L. et al. An ionic diode covalent organic framework membrane for efficient osmotic energy conversion. ACS Nano 16, 18910–18920 (2022).

Xiao, T. et al. High-performance osmotic energy harvesting enabled by the synergism of space and surface charge in two-dimensional nanofluidic membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 673, 365–372 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Mechanically strong MXene/Kevlar nanofiber composite membranes as high-performance nanofluidic osmotic power generators. Nat. Commun. 10, 2920 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Oxidation promoted osmotic energy conversion in black phosphorus membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13959–13966 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Unlocking osmotic energy harvesting potential in challenging real-world hypersaline environments through vermiculite-based hetero-nanochannels. Nat. Commun. 15, 608 (2024).

Ding, L. et al. Bioinspired Ti(3) C(2) T(x) MXene-based ionic diode membrane for high-efficient osmotic energy conversion. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 61, e202206152 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. All-natural 2D nanofluidics as highly-efficient osmotic energy generators. Nat. Commun. 15, 3649 (2024).

Su, Y. et al. Flexible UiO-66-(COOH)2 metal-organic framework membranes for salinity gradient power generation. Chem. Eng. J. 476, 146649 (2023).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Highly selective and high-performance osmotic power generators in subnanochannel membranes enabled by metal-organic frameworks. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe9924 (2021).

Cao, L. et al. Giant osmotic energy conversion through vertical-aligned ion-permselective nanochannels in covalent organic framework membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12400–12409 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Improved ion transport in hydrogel-based nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 2097–2104 (2020).

Bian, G. et al. Anti-swelling gradient polyelectrolyte hydrogel membranes as high-performance osmotic energy generators. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 60, 20294–20300 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Improved osmotic energy conversion in a heterogeneous membrane boosted by a three-dimensional hydrogel interface. Nat. Commun. 11, 875 (2020).

Hao, J. et al. A euryhaline-fish-inspired salinity self-adaptive nanofluidic diode leads to high-performance blue energy harvesters. Adv. Mater. 34, e2203109 (2022).

Chang, C.-W. et al. Space charge enhanced ion transport in heterogeneous polyelectrolyte/alumina nanochannel membranes for high-performance osmotic energy conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 2867–2875 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. High-performance ionic diode membrane for salinity gradient power generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12265–12272 (2014).

Zhou, S. et al. Interfacial super-assembly of ordered mesoporous silica-alumina heterostructure membranes with ph-sensitive properties for osmotic energy harvesting. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 13, 8782–8793 (2021).

Li, Z. Q. et al. Light-enhanced osmotic energy harvester using photoactive porphyrin metal-organic framework membranes. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 61, e202202698 (2022).

Cheng, H. et al. Electrokinetic energy conversion in self-assembled 2d nanofluidic channels with Janus nanobuilding blocks. Adv. Mater. 29, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201700177 (2017).

Safaei, J. et al. Vacancy engineering for high-efficiency nanofluidic osmotic energy generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2669–2678 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Bio-inspired nanocomposite membranes for osmotic energy harvesting. Joule 4, 247–261 (2020).

Yu, C. et al. A smart cyto-compatible asymmetric polypyrrole membrane for salinity power generation. Nano Energy 53, 475–482 (2018).

Hou, Q. et al. Commercial nafion membranes for harvesting osmotic energy from proton gradients that exceed the commercial goal of 5.0 W/m(2). ACS Nano 18, 12580–12587 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Ion-concentration-hopping heterolayer gel for ultrahigh gradient energy conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13191–13200 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Power generation by reverse electrodialysis in a single-layer nanoporous membrane made from core-rim polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 307–312 (2020).

Lim, T. et al. Atomically dispersed Pt-N(4) sites as efficient and selective electrocatalysts for the chlorine evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 11, 412 (2020).

Zhao, S. X. et al. Selective electrosynthesis of chlorine disinfectants from seawater. Nat. Sustain 7, 148–157 (2024).

Nagai, N. Existence of optimum space between electrodes on hydrogen production by water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 28, 35–41 (2003).

O’Brien, T. F. et al. Handbook of Chlor-Alkali Technology. (2005).

Chen, S. et al. Imparting ion selectivity to covalent organic framework membranes using de novo assembly for blue energy harvesting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9415–9422 (2021).

Xiao, M. et al. Self-adaptive amorphous CoO(x)Cl(y) electrocatalyst for sustainable chlorine evolution in acidic brine. Nat. Commun. 14, 5356 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Engineering the coordination environment of ir single atoms with surface titanium oxide amorphization for superior chlorine evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c13834 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. CO(2)-mediated organocatalytic chlorine evolution under industrial conditions. Nature 617, 519–523 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Ultrafast synthesis of IrB(1.15) nanocrystals for efficient chlorine and hydrogen evolution reactions in saline water. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 64, e202414021 (2025).

Suryanto, B. H. R. et al. Challenges and prospects in the catalysis of electroreduction of nitrogen to ammonia. Nat. Catal. 2, 290–296 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Nitrate electroreduction: mechanism insight, in situ characterization, performance evaluation, and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6720–6733 (2021).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22272194), QIBEBT/SEI/QNESL (S202303), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2021YQ12), the Key R&D Project of Shandong Province (2022CXGC010302), Shandong Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. SDCX-ZG-202303046) and the Post-Doctoral Applied Research Project of Qingdao (No. QDBSH20220202048). The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT to correct language errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. and J.G. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. C.Z., Q.L., and S.P. carried out the material synthesis, characterization and performance tests. C.Z., M.L., and B.Z. performed the data analysis. C.Z. wrote the manuscript. The project was mainly supervised by J.G., with help from L.J. J.G. revised the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hao Li, Qilei Song and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, C., Li, Q., Li, M. et al. Spontaneous chlorine production from chloride-containing brines. Nat Commun 17, 1433 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68181-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68181-7