Abstract

Single-crystal alloy thin films (SATFs), featuring highly ordered atomic lattices and superior composition-dependent properties, hold great potential for applications including crystal epitaxy, surface catalysis, and energy conversion. However, their scalable synthesis and practical applications have been hindered by the difficulty of achieving wafer-scale single crystallinity, atomic-scale surface flatness, as well as flexible and uniform control of alloy composition. Here, we developed a surface-energy-compensated technique for synthesizing a series of wafer-scale binary and ternary SATFs with sub-nanometer roughness (minimum roughness lower than 0.2 nm) and uniform, controllable elemental composition with a wide range (5 ~ 50 at%). Furthermore, using CuPtNi(111) ternary SATFs as epitaxial substrates, we achieve wafer-scale synthesis of wrinkle-free graphene single crystals exhibiting fine electronic quality, including a uniform sheet resistance of 552 Ω sq−1 with 4.5% deviation, an ultrahigh carrier mobility up to over half a million cm2 V−1 s−1 at 1.7 K, and well-developed quantum plateaus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-crystal metals have long been regarded as a critical pursuit in materials science due to their superior electrical, thermal, and catalytic properties compared to polycrystalline and unalloyed counterparts1,2,3,4,5,6. Especially, the introduction of alloying elements in fabricating single-crystal alloy thin films (SATFs), offers a promising route to design the functional versatility of pure metals, which would highly expand their potentials in applications of crystal epitaxy, surface catalysis, and energy conversion7,8,9,10. For instance, by incorporating alloying metal atoms to tune the catalytic ability and precursor solubility, SATFs have emerged as ideal epitaxial substrates for the ultrafast, low-temperature synthesis of two-dimensional (2D) single-crystals, such as graphene and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN), together with improved thickness controllability and scalability11,12,13,14,15. However, the real applications of SATFs still strictly require wafer-scale single crystallinity, fine compositional tunability and high uniformity of alloying atoms. Despite the recent progress in the fabrication of pure single-crystal metals, e.g. Cu(111), via abnormal grain growth or solid-phase epitaxy mechanism16,17,18, the lack of methods for fabricating SATFs in a controllable and scalable manner still hinders their practical applications.

Additionally, the surface flatness of single-crystal metals and their alloy derivatives is another critical requirement. Surface irregularities, such as atomic steps and strain-induced bunches, can alter the chemical and physical properties of the metal, such as the acceleration of oxidation19, which would hamper the stability and performance essential for applications in semiconductor electronic devices20,21. Moreover, surface flatness of metal substrates is equally important for the quality of epitaxially grown 2D materials22,23. For instance, the rough surface of Cu foils, typically produced from commercial cold-rolled foils, promotes severe wrinkle formation during growth, and also leads to crack formation after post-growth transfer, both of which have become the bottlenecks to the homogeneous quality of as-obtained 2D materials24,25.

Magnetron sputtering of target alloy films primarily with face-centered cubic (FCC) structures onto single-crystal sapphire substrates, followed by annealing-enabled alloying, is commonly employed to fabricate wafer-scale SATFs. Such a method usually exhibits precise control over film composition and thickness26,27,28. However, the inherent symmetry mismatch between the deposited FCC alloy films and the underlying sapphire often induces in-plane twin boundaries (TBs)29,30,31, a commonly observed issue in the fabrication of single-crystal FCC thin films on sapphire (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The presence of TBs leads to the formation of thermal grooves during the following high-temperature annealing and therefore reduces flatness and uniformity32,33. Similar phenomena are frequently observed in the fabrication of single-crystal Cu(111)/sapphire wafers, and the elimination of TBs strictly requires the fine control over both the sputtering and annealing conditions34,35. Such difficulty would be exacerbated by the added complexity of multi-elemental interfaces in metal alloys.

Alternatively, the deposition of alloying metal onto TB-free, single-crystal Cu(111)/sapphire templates followed by alloying via interdiffusion of deposited metal atoms into the Cu bulk can avoid the formation of TBs in the final metal alloy36. However, such an approach suffers from severe dewetting during high-temperature annealing, leading to the emergence of numerous dewetting holes across the film surface37,38,39.

Herein, we demonstrate that the dewetting of alloy film during the annealing process on Cu(111)/sapphire primarily originates from its lateral contraction at TBs, driven by the minimization of surface energy. To address this, we propose a surface-energy-compensated (SEC) strategy, in which the deposition of alloying metals follows the order from high to low surface energy, enabling the facile fabrication of wafer-scale binary and ternary SATFs with sub-nanometer flatness (minimum value below 0.2 nm), and highly uniform, tunable elemental compositions across a wide compositional range (5~50 at%). Wrinkle-free, 4-inch single-crystalline monolayer graphene was successfully grown on ternary SATF, CuPtNi(111), at a low temperature of 850 °C, enabling the wrinkle suppression and enhanced uniformity. As-harvested graphene exhibited exceptional electronic performance, including a uniform sheet resistance of 552 Ω sq−1 with 4.5% deviation, an ultrahigh carrier mobility up to 560,000 cm2 V−1s−1 at 1.7 K, and well-developed quantum plateaus.

Results

Dewetting behavior of alloy thin films

To fabricate ultraflat CuNi(111) as a representative binary SATF, we first investigated the dewetting behavior of a deposited Ni film on a single-crystal Cu(111)/sapphire substrate. 52 nm Ni was deposited onto the Cu(111) with thickness of 500 nm via magnetron sputtering, yielding a final single-crystal Cu90Ni10(111) alloy film with dense dewetting holes after annealing (Fig. 1a). Corresponding electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) characterization at each stage was demonstrated in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 3. Specifically, the as-deposited Ni film is polycrystalline, and contains (111)-oriented grains with two energetically equivalent in-plane orientations rotated by 60°, arising from the symmetry mismatch between the three-fold rotational symmetry of Ni(111) grains and the six-fold rotational symmetry of the underlying Cu(111) surface. During annealing, the deposited Ni film undergoes grain growth and TB formation. Due to the significantly higher surface energy of Ni relative to Cu40,41, dewetting is energetically favored at the regions in the presence of TBs, initiating the formation of dewetting holes. After the alloying process and complete diffusion of Ni into the Cu(111) bulk, such dewetting holes remain on the final CuNi(111) surface.

Schematic illustration (a) and corresponding electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) maps in the [100] direction (b), showing the formation of dewetting holes initiated at twin boundaries in the deposited Ni. c In situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) results during annealing of sputtered Ni on Cu(111), revealing the emergence of Cu90Ni10(111) at around 700 °C. The black dashed lines represented the diffraction peaks of Al2O3(0006), Cu(111), and Ni(111), respectively, while the white dashed line represented the diffraction peak of newly-formed Cu90Ni10(111) alloy. d Representative XRD θ−2θ scans acquired before, during, and after alloy formation. e Temperature-dependent evolution of dewetting hole diameter (blue) and red-channel intensity (red) extracted from in situ optical microscopy (OM) characterization, indicating the onset and progression of dewetting and alloying transition, respectively. Inset: in situ OM image captured at 600 °C. Typical OM images of the annealed Cu90Ni10(111) surface captured at 5× (f) and 20× (g) magnifications, respectively. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) image (h) and corresponding height profile (i) of a dewetting hole along the white dashed line. Cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the ridge of a dewetting hole (j), with the enlarged image at the Cu90Ni10(111)/Al2O3 interface (k). Inset: fast Fourier transform pattern of the region outlined by gray dashed lines.

In situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) and optical microscopy (OM) characterization were conducted to further elucidate dewetting behavior. At early stages of heating, the in situ XRD spectra showed only Cu(111) and Ni(111) diffraction peaks, and a gradually shifting of the corresponding peaks was observed due to the thermal-induced lattice expansion (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 4). The emergence of the CuNi(111) peak at 700 °C indicated the complete formation of CuNi alloy (Fig. 1d). In comparison, dewetting holes were first detected at ~526 °C in the in situ OM and became clearly visible at ~600 °C; further growth of such holes was observed with increasing temperature (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6, Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). Additionally, a distinct color change in the OM images, from silvery-white to yellow, was observed at ~700 °C, corresponding to an increase in the red channel in RGB analysis. Such color changes indicate the dissolution of Ni atoms into Cu(111), and the formation of the CuNi(111) alloy.

Densely distributed dewetting holes were observed in OM images of the final CuNi(111) film after annealing (Fig. 1f, g). Atomic force microscopy (AFM) revealed that these holes exhibited well-defined hexagonal shapes, with depth reaching up to ~550 nm (Fig. 1h and i). Furthermore, lateral diffusion of alloy atoms during the dewetting process created ring-shaped ridges around the hole edges, with a height of ~200 nm. Although a high-resolution aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image did not observe significant lattice distortion in the ridges (Fig. 1j and k), the dense distribution of such dewetting holes over the entire film would severely degrade the flatness and uniformity of the resulting SATFs, hindering subsequent applications.

Suppression of dewetting via surface-energy modulation

Fig. 2a-b illustrates our SEC strategy, in which the surface energy of each deposited metal layer was carefully designed to suppress the dewetting behavior. Specifically, an additional Cu layer with lower surface energy was deposited on top of the pre-deposited metal alloy layer, which would reduce the overall surface energy and therefore hinder the dewetting process. Selective-area deposition of Cu on Ni/Cu(111) was conducted to confirm the contribution of an additional Cu layer to the suppression of the formation of dewetting holes. As demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8, dewetting only occurred in the region without additional Cu, further confirming the effectiveness of our SEC strategy.

Schematic of dewetting process during the fabrication of binary SATFs with high-surface-energy (γ) deposited metal (a), and its suppression via the introduction of a SEC Cu layer with lower γ (b). c Dependence of dewetting hole number of Cu90Ni10(111) on the thickness of the Cu SEC layer. The error bars were obtained from the statistical analysis of 10 independent optical microscopy images acquired at 2.5× magnification for each SEC Cu thickness. d SEC Cu thickness required to suppress the dewetting of Cu90Ni10(111) with various Ni compositions. e Temperature-dependent evolution of dewetting hole diameter (blue) and red-channel intensity (red) extracted from in situ OM characterization, showing complete suppression of dewetting throughout the alloying process. f Cross-sectional STEM image of Cu90Ni10(111) (left) and corresponding energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental maps of Cu and Ni (right), respectively. Cross-sectional STEM images of Cu90Pt10(111) (g) and Cu90Pd10(111) (h) with corresponding EDS elemental maps, respectively. i Schematic illustration of the fabrication of ultraflat CuPtNi(111) with SEC Cu, applicable to both Cu/Ni/Pt/Cu(111) and Cu/Pt/Ni/Cu(111) stacking sequences. j Cross-sectional STEM image of Cu90Pt5Ni5(111) (left) and corresponding EDS elemental maps of Cu, Pt and Ni (right), respectively. 3D elemental distribution (k) and corresponding depth profiles of Cu, Pt, Ni and Al (l) in Cu90Pt5Ni5(111), obtained from time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry results.

Note that further increasing the thickness of the SEC Cu layer would effectively reduce the density of dewetting holes in final CuNi(111) films (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figs. 9–11). For Cu90Ni10, a 60 nm SEC Cu was sufficient to completely suppress dewetting. In addition, higher Ni compositions in final metal alloy usually required thicker SEC Cu layers to prevent dewetting (Supplementary Fig. 12). Such requirement in turn increased the temperature required for the complete alloying between Ni and Cu(111) bulk, as confirmed by in situ XRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 13). In such case, more unalloyed Ni remains on the Cu(111) surface during the entire annealing process, thereby extending the duration in which dewetting occurs. By optimizing the SEC Cu thickness required for each target Ni composition and precisely controlling the deposited Ni thickness, we successfully fabricated ultraflat CuNi(111) films with 5 at%, 10 at%, 20 at%, 30 at%, 40 at%, and 50 at% Ni, all of which were confirmed to be free of dewetting holes (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Figs. 14–18). Furthermore, in situ OM characterization revealed two distinct stages of color contrast evolution (Fig. 2e), corresponding to the sequential alloying of the surface-deposited Ni and SEC Cu layers, and the subsequent diffusion of alloying metals into Cu(111) bulk to completely form the CuNi(111). This observation is also consistent with the in situ XRD results, and further analysis confirms that the SEC Cu thickness plays a critical role in determining the alloying temperature of the sputtered layer and thus the efficiency of dewetting suppression (Supplementary Fig. 19). In addition, almost no dewetting holes were observed throughout the entire in situ annealing process of Cu/Ni/Cu(111) sample (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21, Supplementary Videos 3 and 4), further confirming the contribution of presented strategy to the suppression of dewetting process.

In addition to CuNi(111), dewetting behavior was also observed in other binary SATFs including CuPt(111) and CuPd(111), primarily owing to the higher surface energy of Pt and Pd relative to Cu42, as well as their relatively high temperature for complete alloying, as confirmed by in situ XRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 22). Similarly, the introduction of additional SEC Cu layers effectively suppressed the dewetting of both CuPt(111) and CuPd(111), with higher suppression efficiency achieved for alloys with lower surface energy (Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24). OM observation revealed nearly complete absence of dewetting holes across the final Cu90Pt10(111) and Cu90Pd10(111) films. Moreover, for systems beyond Cu-based alloys, dewetting holes were also observed when annealing deposited Ni on Pt(111), while adding an additional Pt layer on top efficiently suppressed this issue (Supplementary Figs. 25−27), indicating the general applicability of our SEC strategy for fabricating various binary SATFs with high uniformity and flatness.

The detailed atomic structures of the resulting binary SATFs were further characterized by STEM observation (Fig. 2f), in which a clear epitaxial relationship between Cu90Ni10(111) and sapphire(0001) was clearly revealed in the cross-sectional STEM image along the [1\(\bar{1}\)0] direction19. Furthermore, the absence of lattice distortion confirmed the formation of a high-quality, single-crystalline Cu90Ni10(111) film with reduced strain level. Corresponding energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping further verified the uniform elemental distribution of Cu and Ni elements at the atomic scale43. Similar structure features were observed in Cu90Pt10(111) and Cu90Pd10(111) films, both exhibiting highly ordered (111) stacking planes and uniform distribution of Cu, Pt, and Pd elements as evidenced by EDS mappings, with individual elemental atoms clearly resolved (Fig. 2g, h). Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) was employed to evaluate large-area elemental uniformity across the entire film thickness, which exhibited high sensitivity and depth resolution36,44,. Three-dimensional (3D) elemental maps and corresponding depth profiles for single-crystal CuNi(111), CuPt(111), and CuPd(111) films with 10 at% alloying elements all revealed uniform elemental distribution throughout the bulk phase of binary SATFs (Supplementary Fig. 28).

In addition to the binary SATFs, dewetting was also observed in ternary alloys, as exemplified by CuPtNi (Supplementary Fig. 29). Following the same SEC strategy, an ultraflat Cu90Pt5Ni5(111) ternary SATF was successfully fabricated, and both sequential deposition sequences of Pt and Ni were proven effective (Fig. 2i, Supplementary Figs. 30–32, and Supplementary Videos 5 and 6). Consistent with the suppression of dewetting observed in binary SATF results, no dewetting holes were observed during the entire high-temperature annealing. Similarly, the improved crystallinity and compositional uniformity of the resulting Cu90Pt5Ni5(111) ternary SATF were confirmed by cross-sectional STEM, corresponding EDS, and ToF-SIMS characterization (Fig. 2j-l).

Wafer-scale fabrication of binary and ternary SATFs

Enabled by the surface energy modulation mechanism, we further achieved wafer-scale fabrication of binary and ternary SATFs with 10 at% alloying elements on 4-inch Cu(111)/sapphire substrates (Fig. 3a). To confirm their single-crystalline nature, both out-of-plane and in-plane XRD measurements were performed. As shown in Fig. 3b and c, XRD θ−2θ scans demonstrated sharp (111) diffraction peaks corresponding to CuNi(111), CuPt(111), CuPd(111) and CuPtNi(111), respectively, and all corresponding φ scans displayed diffraction peaks with 120° intervals, verifying the absence of in-plane twin structures in as-received (111)-oriented SATFs45,46. EBSD characterization was further conducted to examine the crystal orientation of the receiving SATFs with alloy compositions ranging from 5 at% to 50 at%. Representative EBSD results (Supplementary Figs. 33–36), including the EBSD color maps, inverse pole figures (IPFs), and corresponding pole figures (PFs) confirmed the single crystallinity and the absence of in-plane twinning, consistent with XRD observation.

a Photograph of 4-inch binary and ternary SATF wafers with 10 at% alloying elements. XRD θ−2θ scans (b) and φ (c) scans of the SATFs in (a), respectively. d Comparison of dewetting hole counts in binary and ternary SATFs fabricated with (orange) and without (green) the SEC approach. e Photograph of the entire CuPtNi(111) wafer stitched by 413 OM images at 2.5× magnification. f Distribution of the dewetting hole counts across the 4-inch CuPtNi(111) wafer. Note that statistical analysis was limited to the black-boxed central areas in (e), with wafer edges excluded to minimize potential artifacts in image recognition. g Statistics of surface roughness (Ra) of binary and ternary SATFs across the half wafer. The error bars were obtained from the statistical analysis of 66 AFM images for each wafer, respectively. Inset: Ra mapping. Scale bar: 1 cm. Representative AFM image of the CuPtNi(111) (h) and corresponding height profile (i) along the white dashed line in (h). Cross-sectional STEM image of the CuPtNi(111) surface region (j), and corresponding intensity profile (k) for the (111) plane.

A home-built OM system equipped with an automatic stitching stage was employed to quantitatively probe the distribution of dewetting holes across the entire 4-inch surface of SATFs (Supplementary Figs. 37 and 38, Supplementary Video 7), which were fabricated with and without using the SEC strategy, respectively. In detail, for each 4-inch SATF wafer, a total of 413 OM images were automatically acquired at 2.5× magnification, which would be subsequently stitched to generate a high-resolution, full-wafer reconstructed image. Dewetting holes with unique characteristic morphology and size were then identified and counted via automatically analyzing the contrast of the as-obtained reconstructed OM images. As shown in Fig. 3d, SATFs prepared using the SEC approach exhibited only a few tens of dewetting holes across the entire 4-inch wafer, confirming an obvious reduction by several orders of magnitude compared to wafers fabricated without the SEC strategy (Supplementary Figs. 39–42). Remarkably, the 4-inch single-crystalline CuPtNi(111) wafer exhibited the lowest density of dewetting holes, as evidenced by the stitched OM image and the corresponding statistical analysis (Fig. 3e, f and Supplementary Fig. 43).

The large-area flatness of the receiving binary and ternary SATFs was further verified by using AFM topographic mapping across the entire half-wafer regions (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Figs. 44–49). All binary SATFs exhibited surface roughness (Ra) values below 0.5 nm, with minimum roughness values of 0.303 nm for CuNi(111), 0.341 nm for CuPt(111), and 0.277 nm for CuPd(111), respectively. In particular, the CuPtNi(111) ternary SATF demonstrated an even smoother surface, which can be attributed to the increased energy barrier for plastic slip, as revealed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Supplementary Fig. 50). A representative 10 × 10 μm2 AFM image revealed an Ra of 0.173 nm, and the corresponding height variation exhibited a narrow range of ± 0.5 nm (Fig. 3h and i). A series of AFM images with scanning areas ranging from 50 × 50 μm2 to 1 × 1 μm2 consistently showed Ra values from 0.240 to 0.124 nm, respectively, further confirming the ultraflat surface of CuPtNi(111) film (Supplementary Fig. 49). The atomically flat and undistorted nature of CuPtNi(111) was also evidenced by STEM, in which well-aligned (111) stacking planes with an interplanar spacing of 0.20 nm were clearly observed (Fig. 3j and k). To further evaluate the local strain distribution near the CuPtNi(111) surface, geometrical phase analysis (GPA) was performed. Both the in-plane and out-of-plane strain maps from GPA revealed no obvious variation across the entire surface region (Supplementary Fig. 51)47, indicating that the CuPtNi(111) film maintains a nearly perfect atomic structure with reduced strain level and low density of structural defects.

Growth of wrinkle-free graphene single crystals on CuPtNi(111)

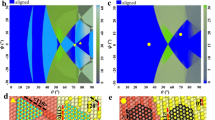

To demonstrate the capability of as-received ultraflat SATFs for the epitaxial growth of 2D materials, wafer-scale single-crystalline graphene was successfully synthesized on various SATFs with 10 at% alloying elements via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) approach. The growth behavior of graphene in terms of quality and growth rate was confirmed to be highly dependent on relative SATF composition and growth temperature (Supplementary Figs. 52 and 53). For instance, the relatively low catalytic activity of Pt limits graphene growth on CuPt(111) surfaces to low rates and high defect densities at lower temperatures48, with defect-free graphene achievable only at elevated temperatures around 1000 °C. In contrast, the high catalytic activity of Ni enables defect-free graphene with full surface coverage over a broad temperature range on CuNi(111); however, the high carbon solubility of Ni leads to the formation of undesirable multilayer graphene flakes. In this regard, in the CuPtNi(111) ternary SATF, the content of Pt and Ni can design the carbon solubility and catalytic ability of entire alloy substrate, which in turn achieves the growth of high-quality, monolayer graphene with high thickness uniformity across a broad window of growth temperature. More importantly, the ability to lower the growth temperature of defect-free graphene would reduce the thermal stress arising from the underlying substrate, and therefore suppress the formation of wrinkles13,14,49, which would otherwise severely degrade the intrinsic properties of graphene. In addition, the surface energy of the alloy substrate also affects its binding energy with graphene, influencing the resulting wrinkle formation (Supplementary Fig. 54). As shown in Fig. 4a, pronounced step-bunching morphology appeared owing to the thermal stress between graphene and the substrate50, and the formation of graphene wrinkles was clearly visible in graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) at 1000 °C. In contrast, when the growth temperature decreased to 850 °C, as-harvested 4-inch graphene film exhibited nearly no observable wrinkles throughout wafer-scale evaluation (Fig. 4b and c, and Supplementary Figs. 55, 56).

AFM images of graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) at 1000 °C (a) and 850 °C (b), respectively. c Temperature-dependent evolution of wrinkle formation in graphene grown on CuPtNi(111), showing complete wrinkle suppression at 850 °C. Note that the total wrinkle length was obtained by summing the wrinkle lengths in 6 representative 10 × 10 μm2 AFM images from randomly selected regions for each growth temperature. d In-plane φ scans of the 4-inch graphene and underlying CuPtNi(111) wafers. e Micro-low-energy electron diffraction patterns of graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) collected at six different positions. f Scanning tunneling microscopy image of graphene on CuPtNi(111) surface. Inset: atomic-resolution image revealing the defect-free honeycomb lattice of graphene. g Photograph of 4-inch transferred graphene wafer. h Statistics of ID/IG of transferred graphene. Inset: ID/IG map. i Stitched OM image of transferred graphene grown at 850 °C (top left), a representative OM image captured at 20× magnification from the region marked by gray dashed box (top right), and corresponding wrinkle identification result (bottom). j Stitched OM image of transferred graphene grown at 1000 °C (top left), a representative OM image captured at 20× magnification from the region marked by gray dashed box (top right), and corresponding wrinkle identification result (bottom).

To further evaluate the crystallinity of the wrinkle-free graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) at 850 °C, in-plane XRD was conducted using an incident X-ray beam nearly parallel to the substrate surface, facilitating the wafer-scale characterization51. As shown in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 57, a sharp graphene(10) diffraction peak at 2θ = 40.51°, accompanied by φ-scan peaks with 60° periodical intervals, confirmed the wafer-scale single-crystalline nature52. Moreover, a 30° rotational offset was observed between the φ-scans of the graphene(10) and CuPtNi(2\(\bar{2}\)0), indicating a clear epitaxial relationship between graphene and CuPtNi(111) substrate with small lattice mismatch (Supplementary Fig. 57). Micro-low-energy electron diffraction (μ-LEED) patterns collected from multiple positions across the wafer showed identical sixfold symmetry and clear Moiré patterns (Fig. 4e)53, confirming the single crystallinity and corresponding epitaxial growth behavior. Such single-crystalline nature of as-received graphene was also supported by selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 58). In addition, scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) image revealed atomically flat CuPtNi(111) terraces and a defect-free graphene lattice54, confirming wrinkle-free morphology of graphene grown on the CuPtNi(111) surface.

After the transfer of 4-inch graphene film onto a SiO2/Si wafer (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 59), Raman mapping revealed a negligible D band and a uniformly distributed full width at half maximum of the 2D band, confirming the defect-free nature and wafer-scale uniformity (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 60)55. Similarly, a stitched OM image of the transferred graphene at 20× magnification was obtained to identify wrinkles based on linear morphology and relatively darker contrast of wrinkled regions. The wrinkle-free characteristics of graphene grown at 850 oC were clearly supported by the reconstructed OM images (Fig. 4i), while a high density of wrinkles was observed in graphene grown at 1000 °C (Fig. 4j).

Properties of single-crystal graphene wafer

To evaluate the electrical performance of the graphene single-crystalline wafer grown on CuPtNi(111), we fabricated graphene devices based on the transfer length method (TLM) over the 4-inch wafer (Fig. 5a)56,57,58, in which 65 die regions were fabricated with each region containing a 6 × 3 array of TLM devices. Specifically, wrinkle-free graphene exhibited highly uniform sheet resistance (Rs) values, with an average value of 552 Ω sq−1 and only 4.5% variation across the entire wafer (Fig. 5b and d). In contrast, the presence of dense wrinkles of graphene grown at 1000 °C strongly influences its electrical properties, with average Rs values of 863 Ω sq−1 and a variation of 13.7% (Fig. 5c and e).

a Photograph of graphene transfer length method (TLM) device arrays fabricated on a 4-inch wafer. Inset: OM image of the TLM device. Scale bar: 100 μm. Sheet resistance distributions extracted from the central TLM arrays for graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) at 850 °C (b) and 1000 °C (c), respectively. Wafer-scale Rs distributions for graphene grown on CuPtNi(111) at 850 °C (d) and 1000 °C (e), respectively. f Transfer curve of the h-BN-encapsulated graphene device measured at 298 K (blue) and 1.7 K (red). Inset: OM image of the measured devices. Scale bar: 10 μm. g The variation in Rxy (red) and Rxx (blue) as a function of magnetic field (B) at 1.7 K. h Rxy (red) and Rxx (blue) as a function of the back gate voltage (Vg) at 1.7 K and 8 T. The quantized Hall plateaus were observed at filling factors ν = 2, 6, 8, 10.

To further probe its intrinsic electrical properties, wrinkle-free graphene single crystals were encapsulated by h-BN flakes, to minimize substrate and adsorbent-induced scattering59,60. Electrical transport measurements at room temperature (298 K) revealed carrier mobilities of 59,756 cm2 V−1 s−1 for holes and 60,296 cm2 V−1 s−1 for electrons, respectively. At 1.7 K, the carrier mobilities increased markedly to 560,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 for holes and ~400,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 for electrons, respectively (Fig. 5f), indicating the high intrinsic electronic quality.

Further analysis of the longitudinal (Rxx) magnetoresistance and Hall (Rxy) resistance at 1.7 K demonstrated an extracted Hall mobility as high as 520,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 (Fig. 5g), comparable to most reported values of mechanically exfoliated graphene61,62,63. Notably, in the Rxx and Rxy magnetoresistance measurements performed at 1.7 K under a fixed magnetic field (B = 8 T), well-defined quantized Hall plateaus and Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations were clearly observed (Fig. 5h), also confirming the high crystalline and electronic quality of the wrinkle-free graphene64,65,66.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a general and scalable strategy for the facile fabrication of wafer-scale, ultraflat SATFs on sapphire. By designing the order of depositing metal layers according to the surface energy, dewetting was successfully suppressed during high-temperature annealing, thereby enabling atomically smooth surfaces (minimum Ra < 0.2 nm) and uniform elemental composition across a wide range (5 ~ 50 at%) of 4-inch binary and ternary SATFs. The as-received CuPtNi(111) can function as ideal catalytic substrates for synthesizing high-quality, single-crystalline graphene wafers at low temperature to avoid the wrinkle formation. As-harvested ultraflat graphene single crystals demonstrate outstanding electrical properties, including a high carrier mobility (560,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 at 1.7 K), uniform sheet resistance (552 Ω sq−1 with 4.5% variation), and well-developed quantum plateaus. The controllable fabrication of SATFs with atomic-scale flatness, and their demonstrated potential for the epitaxial growth of high-quality 2D single crystals, will accelerate fundamental research in metallic materials and provide a strong materials basis for next-generation 2D-based devices.

Methods

Fabrication of TB-free, single-crystal Cu(111)/sapphire templates

Single-crystal sapphire wafers (4-inch, c plane with miscut <0.2°, 650 μm thickness, HELIOS New Materials Co., Ltd) were used as epitaxial substrates for the fabrication of TB-free, single-crystal Cu(111) films. Prior to deposition, sapphire wafers were annealed in O2 for 6 h at 1020 °C to eliminate lattice defects and improve surface morphology. Subsequently, a 500nm-thick Cu film was deposited onto the sapphire substrates by direct current (DC) magnetron sputtering (150 W, room temperature, basal pressure less than 1 × 10−5 Pa, QAM-4 W, ULVAC). The resulting Cu/sapphire wafers were then annealed at 1000 °C under a controlled temperature gradient34, in a flow of 900 sccm Ar and 100 sccm H2 at atmospheric pressure for 30 minutes, to promote the single-crystallization of the Cu(111) film.

Fabrication of binary and ternary SATFs

Ni, Pt, Pd and corresponding SEC Cu layers were sequentially deposited onto the Cu(111) template by DC magnetron sputtering (150 W, room temperature, basal pressure less than 1 × 10−5 Pa, QAM-4 W, ULVAC), with sputtering times adjusted to achieve the desired film thicknesses. Subsequently, the as-deposited alloy wafers were then annealed at 1000 °C under a flow of 1000 sccm Ar and 50 sccm H2 at atmospheric pressure for 30 minutes, enabling complete alloying and the formation of the ultraflat SATFs.

In situ OM observation

In situ OM observations were performed using a high-temperature reactor (Micro-STS1200 system, Units Technology) equipped with a custom-built gas supply system. A transparent quartz window mounted at the top of the reactor enabled real-time OM characterization during the annealing process. Alloy thin film specimens (0.5 × 0.5 cm2) were monitored continuously using 5× and 50× objective lenses (LV150ND, Nikon), respectively, to observe the dewetting and alloying processes under a mixed gas flow of 50 sccm H2 and 50 sccm Ar.

CVD growth of graphene

The SATFs with 10 at% alloying elements were heated to the growth temperature under the flow of 30 sccm H2 and 1000 sccm Ar at atmospheric pressure. The growth temperature of graphene was set to 800, 850, 900, 950, and 1000 °C, respectively. Once the temperature was reached, 50 sccm CH4 (0.1% diluted in Ar) was introduced for graphene growth, while maintaining the H2 and Ar flow rates. After graphene growth, the same gas flow ratios and chamber pressure were maintained during cooling to room temperature.

Transfer of graphene

Polymer-assisted wet transfer method was conducted to transfer graphene onto SiO2/Si substrate. Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) (950 K A4, Microchem Corp.) was spin-coated onto the graphene/SATFs at 2000 r min−1 for 1 min. Subsequently, thermal release tape (TRT) (No.3198MS, Nitto Denko company) was laminated onto the PMMA/graphene/SATF structures as a supporting layer to provide mechanical support for large-area transfer. The graphene was then delaminated from the SATFs via an electrochemical bubbling method. After detachment, the PMMA/graphene film was rinsed and dried before being laminated onto the target SiO2/Si substrate. Finally, PMMA was removed using acetone to yield clean graphene on the SiO2/Si substrate for further characterization.

For the preparation of suspended graphene on commercial TEM grids (R 1.2/1.3, Au, 300 Mesh, Quantifoil), a polymer-free transfer method was employed67. The TEM grid was placed directly onto the surface of graphene/SATFs, a droplet (~5 μL) of isopropanol was applied to enhance the contact between the TEM grid and graphene. The underlying SATFs were then etched using Na2S2O8 solution (0.2 mol/L) to release graphene. After etching, the graphene/TEM grid was rinsed three times with deionized water and air-dried overnight.

Additionally, a terpineol-assisted transfer process was utilized for device fabrication25. First, alpha-terpineol (98% purity, Ark Pharm) was dissolved in n-heptane (10 wt%, Tianjin Concord Technology), and spin-coated onto the graphene/SATFs at 2000 r min−1 for 8 times. Thereafter, PMMA (950 KA4, Microchem Corp) was spin-coated followed by lamination of TRT (No.3198MS, Nitto Denko company). After electrochemical bubbling, the TRT/PMMA/graphene stack was rinsed and dried for 8 hours before being transferred onto the SiO2/Si substrate. The stack structure was placed into an oven at 120 °C for 30 minutes, and PMMA was then removed by tearing TRT on top, exposing a residue-free graphene surface for device fabrication.

Fabrication of graphene TLM devices

The graphene TLM devices were fabricated using standard photolithography techniques to evaluate sheet resistance. Wafer-scale electrode patterning with varying spacings on a 4-inch SiO2/Si wafers was achieved via laser direct writing (Heidelberg MLA-150) using photoresist (AR-P5350). Metal contacts, consisting of a 4 nm Cr adhesion layer and a 36 nm Au layer, were deposited by electron beam evaporation (Angstrom Engineering Nexdep). Following lift-off, the as-grown graphene was transferred onto the patterned electrodes. Additional photolithography and oxygen plasma etching were employed to fabricate the graphene channels and TLM structures. The resulting devices feature multiple metal electrodes spaced at different distances along a single graphene strip, enabling the extraction of sheet resistance through electrical measurements. Electrical characterization was performed using a probe station (Lakeshore CRX-VF) coupled with a semiconductor parameter analyzer (B1500A, Keysight).

To accurately measure the resistance of graphene while eliminating the influence of contact resistance, a four-probe method was employed68. In this configuration, current is sourced through the outer pair of electrodes, while the voltage drop is measured across the inner pair of probes. This geometry ensures that the measured voltage reflects only the voltage drop across the graphene channel, independent of the contact resistances.

The channel resistance Rchannel measured by the four-probe method is given by:

Where Rs is the sheet resistance of the graphene, L is the channel length (distance between contacts), and W is the channel width.

Fabrication of h-BN/graphene/h-BN heterostructure devices

The h-BN/graphene/h-BN heterostructure was fabricated using a dry-transfer technique69. Specifically, a poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) stamp coated with poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) was first employed to pick up exfoliated h-BN flakes from the substrate. Subsequently, the same stamp was used to sequentially pick up a graphene layer via van der Waals interaction between the h-BN and graphene. The resulting h-BN/graphene stack was then aligned and transferred onto a pre-deposited bottom h-BN flake by melting the PPC layer, thereby completing the heterostructure. Following the stack assembly, electron beam lithography was used to define the electrode pattern, and reactive ion etching was employed to selectively etch the h-BN layer on top of the graphene. This was followed by the deposition of 5 nm Cr and 40 nm Au to form edge contacts with the graphene.

Transport measurements

A standard lock-in detection method was employed in a cryostat (Attocube AttoDRY 2100 system), with the temperature ranging from 1.7 to 298 K and a magnetic field of up to 8 T.

Characterization

The crystallinity of Cu(111) and SATFs was characterized by OM (LV150ND, Nikon), SEM (FEI Quattro S, 5 kV), EBSD (AMETEK EDAX DigiView Camera in combination with EDAX’s TEAM, 20 kV), XRD (Bruker D8 ADVANCE, with a Cu Kα radiation, 40 kV and 40 mA, step 0.02°), and in situ XRD (PANalytical Empyrean with a Cu Kα radiation, 40 kV and 40 mA, equipped with Anton Paar HTK 1200 N high-temperature oven chamber, step 0.02°). The single-crystallinity and quality of graphene were evaluated by μ-LEED (SPECS LEEM P90), in-plane XRD (Rigaku SmartLabXE, with a Cu-Kα radiation, 40 kV and 30 mA, grazing incident angle 0.3°, step 0.016° for θ−2θ scans and 0.1° for φ scans), and Raman spectroscopy (Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution with a 532 nm laser). Surface morphology of SATFs and graphene was examined by STM (Scienta Omicron STM), and AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon, with ScanAsyst mode). To investigate elemental distribution and atomic-scale structure, TOF-SIMS (TOF-SIMS 5-100, IONTOF GmbH) and aberration-corrected STEM (JEM-ARM200F NEOARM, 200 kV) were employed. Additionally, cross-sectional specimens were prepared by focus-ion beam milling (FEI Strata DB 235).

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Wu, M. et al. Seeded growth of large single-crystal copper foils with high-index facets. Nature 581, 406–410 (2020).

Jin, S. et al. Colossal grain growth yields single-crystal metal foils by contact-free annealing. Science 362, 1021–1025 (2018).

Karaman, C. O., Bykov, A. Y., Kiani, F., Tagliabue, G. & Zayats, A. V. Ultrafast hot-carrier dynamics in ultrathin monocrystalline gold. Nat. Commun. 15, 703 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Oxidization-temperature-triggered rapid preparation of large-area single-crystal Cu(111) foil. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209755 (2023).

Cui, Z., Wong, A. J.-W., Janik, M. J. & Co, A. C. Cation effects on CO2 reduction catalyzed by single-crystal and polycrystalline gold under well-defined mass transport conditions. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr6465 (2025).

Pérez-Gallent, E., Marcandalli, G., Figueiredo, M. C., Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. M. Structure- and potential-dependent cation effects on CO reduction at copper single-crystal electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16412–16419 (2017).

Yuan, G. et al. Proton-assisted growth of ultra-flat graphene films. Nature 577, 204–208 (2020).

Nguyen, V. L. et al. Layer-controlled single-crystalline graphene film with stacking order via Cu-Si alloy formation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 861–867 (2020).

Jiang, J., Ding, W., Li, W. & Wei, Z. Freestanding single-atom-layer Pd-based catalysts: oriented splitting of energy bands for unique stability and activity. Chem 6, 431–447 (2020).

Yao, J. & Yang, G. 2D layered material alloys: synthesis and application in electronic and optoelectronic devices. Adv. Sci. 9, 2103036 (2022).

Wu, T. et al. Fast growth of inch-sized single-crystalline graphene from a controlled single nucleus on Cu-Ni alloys. Nat. Mater. 15, 43–47 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Ultraflat single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride for wafer-scale integration of a 2D-compatible high-κ metal gate. Nat. Mater. 23, 1495–1501 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Single-crystal, large-area, fold-free monolayer graphene. Nature 596, 519–524 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Epitaxial growth of 6 in. single-crystalline graphene on a Cu/Ni (111) film at 750 °C via chemical vapor deposition. Small 15, 1805395 (2019).

Huang, M. et al. Large-area single-crystal AB-bilayer and ABA-trilayer graphene grown on a Cu/Ni(111) foil. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 289–295 (2020).

Sun, L. et al. Toward epitaxial growth of misorientation-free graphene on Cu(111) foils. ACS Nano 16, 285–294 (2022).

Yao, W. et al. Bottom-up-etching-mediated synthesis of large-scale pure monolayer graphene on cyclic-polishing-annealed Cu(111). Adv. Mater. 34, 2108608 (2022).

Deng, B. et al. Wrinkle-free single-crystal graphene wafer grown on strain-engineered substrates. ACS Nano 11, 12337–12345 (2017).

Kim, S. J. et al. Flat-surface-assisted and self-regulated oxidation resistance of Cu(111). Nature 603, 434–438 (2022).

Camacho, J. M. & Oliva, A. I. Surface and grain boundary contributions in the electrical resistivity of metallic nanofilms. Thin Solid Films 515, 1881–1885 (2006).

Kim, K. et al. Extremely flat metal films implemented by surface roughness transfer for flexible electronics. RSC Adv. 8, 10883–10888 (2018).

Tian, B. et al. Ultraflat Cu(111) foils by surface acoustic wave-assisted annealing. Nat. Commun. 15, 9488 (2024).

Zheng, L. et al. Uniform thin ice on ultraflat graphene for high-resolution cryo-EM. Nat. Methods 20, 123–130 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Folding and fracture of single-crystal graphene grown on a Cu(111) foil. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110509 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Large-area transfer of two-dimensional materials free of cracks, contamination and wrinkles via controllable conformal contact. Nat. Commun. 13, 4409 (2022).

Ha, T. et al. Coherent consolidation of trillions of nucleations for mono-atom step-level flat surfaces. Nat. Commun. 14, 685 (2023).

Kim, S. J. et al. Color of copper/copper oxide. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007345 (2021).

Tang, J. et al. Ultrafast growth of wafer-scale fold-free bilayer graphene. Nano Res. 16, 10684–10689 (2023).

Miller, D. L., Keller, M. W., Shaw, J. M., Chiaramonti, A. N. & Keller, R. R. Epitaxial (111) films of Cu, Ni, and CuxNiy on α-Al2O3(0001) for graphene growth by chemical vapor deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 112 (2012).

Burton, O. J. et al. Integrated wafer scale growth of single crystal metal films and high-quality graphene. ACS Nano 14, 13593–13601 (2020).

Oh, S., Scheu, C., Wagner, T., Tchernychova, E. & Ruhle, M. Epitaxy and bonding of Cu films on oxygen-terminated α-Al2O3(0001). Surf. Acta Mater. 54, 2685–2696 (2006).

Han, G. H. et al. Influence of copper morphology in forming nucleation seeds for graphene growth. Nano Lett. 11, 4144–4148 (2011).

Luo, Z. et al. Effect of substrate roughness and feedstock concentration on growth of wafer-scale graphene at atmospheric pressure. Chem. Mater. 23, 1441–1447 (2011).

Zhu, Y. et al. Controlled growth of single-crystal graphene wafers on twin-boundary-free Cu(111) substrates. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308802 (2024).

Chen, T.-A. et al. Wafer-scale single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayers on Cu(111). Nature 579, 219–223 (2020).

Deng, B. et al. Scalable and ultrafast epitaxial growth of single-crystal graphene wafers for electrically tunable liquid-crystal microlens arrays. Sci. Bull. 64, 659–668 (2019).

Amram, D., Klinger, L. & Rabkin, E. Anisotropic hole growth during solid-state dewetting of single-crystal Au-Fe thin films. Acta Mater. 60, 3047–3056 (2012).

Dierner, M. et al. Influence of Au alloying on solid state dewetting kinetics and texture evolution of Ag and Ni thin films. Surf. Interf. 46, 1–8 (2024).

Herz, A. et al. Solid-state dewetting of Au-Ni bi-layer films mediated through individual layer thickness and stacking sequence. Appl. Surf. Sci. 444, 505–510 (2018).

Wen, Y.-N. & Zhang, J.-M. Surface energy calculation of the fcc metals by using the MAEAM. Solid State Commun. 144, 163–167 (2007).

Liu, H., Valanoor, N., Bogle, K. & Cheng, X. An empirical method for surface energy anisotropy determination in high symmetry crystals. ACS Omega 10, 45278–45289 (2025).

Singh-Miller, N. & Marzari, N. Surface energies, work functions, and surface relaxations of low-index metallic surfaces from first principles. Phys. Rev. B. 80, 235407 (2009).

Gioria, E. et al. CuNi nanoalloys with tunable composition and oxygen defects for the enhancement of the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217888 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Adlayer-free large-area single crystal graphene grown on a Cu(111) foil. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903615 (2019).

Miller, D. L. et al. Giant secondary grain growth in Cu films on sapphire. AIP Adv. 3, 082105 (2013).

Lee, I.-J. et al. Epitaxial growth and characterization of Cu thin films deposited on Al2O3(0001) substrates by magnetron sputtering. Mater. Lett. 299, 130119 (2021).

Hÿtch, M. J., Putaux, J.-L. & Pénisson, J.-M. Measurement of the displacement field of dislocations to 0.03 Å by electron microscopy. Nature 423, 270–273 (2003).

Wang, X., Yuan, Q., Li, J. & Ding, F. The transition metal surface dependent methane decomposition in graphene chemical vapor deposition growth. Nanoscale 9, 11584–11589 (2017).

Zhao, C. & Ding, F. Temperature-dependent graphene wrinkle formation: A theoretical study. Sci. China Mater. 67, 2210–2216 (2024).

Yi, D. et al. What drives metal-surface step bunching in graphene chemical vapor deposition? Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 246101–246105 (2018).

Yu, H. et al. Eight in. wafer-scale epitaxial monolayer MoS2. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402855 (2024).

Taniguchi, T. et al. Revisiting the two-dimensional structure and reduction process of graphene oxide with in-plane X-ray diffraction. Carbon 202, 26–35 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Single-crystal two-dimensional material epitaxy on tailored non-single-crystal substrates. Nat. Commun. 13, 1773 (2022).

Amontree, J. et al. Reproducible graphene synthesis by oxygen-free chemical vapour deposition. Nature 630, 636–642 (2024).

Ferrari, A. C. & Basko, D. M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 235–246 (2013).

Giambra, M. A. et al. Wafer-scale integration of graphene-based photonic devices. ACS Nano 15, 3171–3187 (2021).

Canto, B. et al. Multi-project wafer runs for electronic graphene devices in the European 2D-Experimental Pilot Line project. Nat. Commun. 16, 1417 (2025).

Lee, S. et al. Contact resistivity in edge-contacted graphene field effect transistors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2101169 (2022).

Banszerus, L. et al. Ultrahigh-mobility graphene devices from chemical vapor deposition on reusable copper. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500222 (2015).

Moon, J.-Y. et al. Layer-engineered large-area exfoliation of graphene. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc6601 (2020).

Dean, C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 722–726 (2010).

Wang, L. et al. One-dimensional electrical contact to a two-dimensional material. Science 342, 614–617 (2013).

Ki, D.-K. & Morpurgo, A. F. High-quality multiterminal suspended graphene devices. Nano Lett. 13, 5165–5170 (2013).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Room-temperature quantum Hall effect in graphene. Science 315, 1379–1379 (2007).

Feldman, B. E., Martin, J. & Yacoby, A. Broken-symmetry states and divergent resistance in suspended bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 5, 889–893 (2009).

Gao, X. et al. Integrated wafer-scale ultra-flat graphene by gradient surface energy modulation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5410 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Clean transfer of large graphene single crystals for high-intactness suspended membranes and liquid cells. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700639 (2017).

Pavesi, M., Parisini, A., Calvi, P., Bosio, A. & Fornari, R. Effects of the interface properties on the performance of UV-C photoresistors: gallium oxide as case study. Sensors 25, 345 (2025).

Sun, X. et al. Correlated states in doubly-aligned hBN/graphene/hBN heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 12, 7196 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. T2188101, 52202033, and 52372038), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFA1204900), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 2252064), the Beijing National Laboratory for Molecular Sciences (No. BNLMS-CXTD−202001), and Jiangsu Materials Science Association (No. JSTJ−2024-047). We acknowledge the Electron Microscopy Laboratory of Peking University, China, for the use of JEM-ARM200F NEOARM transmission electron microscopy. We thank the Center for Physicochemical Analysis and Measurement, Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for assistance with XRD characterization. We thank the engineer Chong Guo, Analysis Center, Department of Chemistry, Tsinghua University, for her help with the TOF-SIMS test.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S., S.L., Z.S., and Y.S. contributed equally to this work. Z.L. and K.J. conceived the experiment. Z.L. and K.J. supervised the project. J.S., S.L., Y.S., and G.G. conducted the fabrication of SATFs and CVD growth of graphene. J.S., S.L., Y.S., G.G., S.W., Y.G., D.Z., W.C., and B.Y. took and analyzed the OM, EBSD, AFM, XRD, and SAED data. M.Y.L. and M.X.L. conducted the STM characterization. X.M. conducted the STEM and EDS characterization. W.C. and J.Z. conducted the Raman measurements. S.W. conducted the in-plane XRD characterization. J.S. and Y.S. conducted the transfer of graphene. Z.S., J.L., and L.L. performed device fabrication and electrical measurements. J.S., G.G., and B.J. conducted sheet resistance measurements. A.C. designed the automatic OM system. H.L. and X.S. conducted the DFT calculations. The manuscript was written by Z.L. and K.J. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Libo Gao, Bo Tian, and Meihui Wang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, J., Li, S., Shi, Z. et al. Surface-energy-compensated fabrication of single-crystal alloy films with atomic-scale flatness. Nat Commun 17, 1460 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68196-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68196-0