Abstract

Indoles are privileged structural motifs in N-heterocyclic chemistry, while developing a general and facile platform capable of directly transforming commodity chemicals into multi-functionalized indoles persists as an unmet challenge. Herein, we present a photo-driven bifunctional iron-catalyzed strategy for one-pot synthesis of indoles from readily available arylamines and alkanes/carboxylic acids. By leveraging a synergistic combination of iron-based photocatalysis via ligand-to-metal charge transfer pathway and Lewis acid catalysis, the method enables efficient C(sp3)–H activation or decarboxylation followed by sigmatropic rearrangement cyclization under mild conditions. The protocol demonstrates broad substrate scope (152 examples), excellent functional group tolerance, and high yields (up to 95%), facilitating the direct construction of diverse indole scaffolds without pre-functionalization. Notably, the methodology can be successfully applied to the concise and scale-up total synthesis of several pharmacologically relevant indole derivatives, including Iprindole, Mebhydrolin, Melatonin, and A-FABP inhibitor, underscoring its practicality and potential for industrial application in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

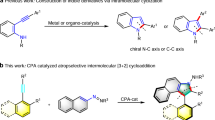

Indoles, as privileged structural motifs in N-heterocyclic chemistry, serve as pivotal building blocks for the construction of natural products1,2,3, agrochemicals, and bioactive pharmaceuticals4,5,6. The enduring pursuit of efficient synthetic routes for indole core construction and functionalization has driven remarkable innovations in modern organic synthesis. Early in 1883, the landmark Fischer indole synthesis was reported, which employs aryl hydrazines and carbonyl compounds to form hydrazones followed by acid-mediated [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement under thermal conditions (Fig. 1a)7. Nevertheless, conventional protocols frequently suffer from operational limitations, including stringent acidic media, narrow substrate scope, and source-restricted substituted arylhydrazine precursors. Over a century of methodological development has yielded a multitude of synthetic approaches8,9,10,11,12, in which one of the most significant developments is demonstrating that aryldiazonium salts can serve as effective precursors for indole synthesis (Fig. 1b). In 2014, Matcha & Antonchick group developed a catalytic protocol for the modular synthesis of C2-CF3CH2-substituted indole derivatives with non-activated olefins, aryldiazonium salts, and sodium triflate13. Subsequently, Xiao group advanced this strategy by photocatalysis to construct trifluoromethylated azo intermediates followed by Brønsted acid-catalyzed cyclization to access indole derivatives14. Apart from the trifluoromethyl-containing scope, organozinc reagents15, alkyl iodides16,17, and dihydropyridine-functionalized alkanes18 have been successfully employed in the construction of azo intermediates with aryldiazonium salts for subsequent indole formation, while some shortcomings, such as the essential pre-activated substrates, fussy multi-step synthesis, and poor atom economy still exist. Given the enduring importance of indoles and the aforementioned limitations, the development of a multifunctional catalytic system to realize integrated indole synthetic paradigms with improved substrate scope and mild conditions remains imperative.

Recent years have witnessed transformative developments in photochemical synthesis as an environmentally benign and atom-economical paradigm for organic transformations. Among these advancements, the photoinduced ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) strategy has emerged as a cutting-edge platform, particularly noted for its efficacy in enabling challenging bond activations and constructions through radical-mediated pathways. Mechanistically, photoexcitation of the LMCT band induces homolytic cleavage of high-valent metal-ligand bonds, generating reactive radical intermediates that drive diverse transformations, such as decarboxylation, C–H functionalization, and β-cleavage processes19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. The strategic implementation of iron-based catalysts in LMCT systems has garnered particular interest, owing to iron’s combination of terrestrial abundance, low toxicity, and simple catalytic system35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45.

These attributes position Fe-LMCT platforms as sustainable alternatives that simultaneously address economic and ecological imperatives in modern synthesis. Importantly, iron catalysts exhibit versatile catalytic capabilities in traditional thermally driven systems46,47,48, including redox catalysis49 and Lewis acid (LA) catalysis50,51. Integrating these multifaceted functions with their emerging photocatalytic competence enables synergistic multi-catalytic processes within a unified system, unlocking broad synthetic potential. Recently, our group pioneered the direct fusion of iron photocatalysis with traditional iron redox catalysis, achieving concurrent alkane C–H activation and stereoselective olefin construction within a single catalytic cycle43. Building upon this foundation, we next attempt to design a Swiss-Army-knife-type catalytic platform integrating iron photocatalysis and iron LA catalysis for addressing the mentioned critical challenges—notably laborious multistep protocols and narrow substrate scope—in indole synthesis (Fig. 1c). This multifunctional system is proposed to simultaneously leverage three consecutive units, including in situ diazotization of anilines, LMCT-driven C–H activation/decarboxylation, and LA-catalyzed cascade cyclization. By orchestrating these mechanistically distinct pathways within one pot, we expect to establish an integrated and streamlined route to various indoles directly from industrial feedstocks.

Building upon our design and research foundation in iron photocatalysis41,42,43,44,45, we herein introduce a photo-induced bifunctional iron-catalyzed strategy that orchestrates the photocatalytic cycle and LA-mediated pathway to replace classical indole synthesis (Fig. 1d). This multifunctional integration protocol enables direct, single-step/one-pot two-step construction of high-value-added indole scaffolds from inexpensive and widely available anilines and alkanes/carboxylic acids, characterized by its ease of operation, mild reaction conditions, high efficiency, low cost, and broad substrate applicability. Notably, the method facilitates the streamlined synthesis of pharmaceutically pivotal indole intermediates—such as Iprindole, Mebhydrolin, Melatonine, etc.—with significantly shortened steps and enhanced efficiency compared to conventional approaches. As a scalable and purification-friendly process, the approach demonstrates a compelling potential for industrial implementation in active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturing.

Results

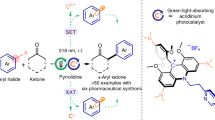

Initially, we explored the feasibility of one-step indole synthesis through photo-induced LMCT-mediated alkane activation, utilizing cyclohexane (1a) and 4-methoxyaniline (1b) as model substrates (Table 1, more details see supplementary Table S1). We were delighted to find that the reaction obtained the desired product 1c in 85% yield with FeCl3·6H2O (0.1 equiv.) as catalyst, tBuONO (1 equiv.), and HBF4 (1.0 equiv.) as diazotization reagents, and MeCN as solvent under N2 and irradiation of 30 W 405 nm LEDs for 12 h (entry 1). The influence of the amount of HBF4 and other protic acids on the yield was systematically examined (entries 1–10), revealing that HBF4 (0.7 equiv.) was optimal with an excellent isolated yield of 95% (entry 5). Moreover, FeCl2·4H2O afforded the product in a competitive yield (entry 11), presumably due to its in-situ oxidation to the active Fe(III) species by tBuONO. Other iron catalysts were investigated but failed to produce indole without chlorides (entries 12–14). Correspondingly, the incorporation of an exogenous chloride source in conjunction with Fe(NO3)3·9H2O was observed to be effective (entry 15), suggesting the chlorine species to be an essential additive for alkane activation. Furthermore, a copper catalyst CuCl2 (entry 16), which has been reported to have similar photocatalytic activity to FeCl352, and a variety of common Lewis acid catalysts (details see Table S1) were evaluated; however, none produced the desired product under the reaction conditions, demonstrating that the iron catalyst exhibits more than one catalytic property in this system. The solvent screening revealed that different solvent choices significantly impacted reaction yields, with DMSO, DCE, and DMF failing to initiate the reaction (entry 17, details see Table S1). Meanwhile, acetone proved to be suitable for this transformation but afforded lower yields than MeCN (entry 18). Various light sources with different wavelengths, including 365 nm, 395 nm, 455 nm, and CFL, were tested next. The results indicated that the reaction efficiency was not as optimal as that achieved with 405 nm LEDs (entries 19–22). In addition, the yield of 1c slightly decreased when the reaction was performed by employing 0.05 equivalent of FeCl3·6H2O (entry 23). Notably, the addition of TBACl to increase the chloride ion concentration resulted in an improved reaction efficiency with a slightly reduced yield (entry 24). Control experiments revealed that no product was observed in the absence of an iron catalyst (entry 25), light (entry 26), or under air (entry 27).

With the optimal reaction conditions for the one-step iron-catalyzed construction of indole skeletons in hand, we proceeded to systematically investigate the reaction scope using diverse alkane and arylamine substrates (Fig. 2). Preliminary investigations employing a series of cycloalkanes (5-, 6-, 7-, 8-, and 12-membered rings; 1c–6c) demonstrated consistently excellent reactivity ( > 90% yields). Notably, cyclooctane (5c) exhibited extraordinary reactivity, and its derived indole product constitutes a pivotal synthetic intermediate for Iprindole, a finding that significantly streamlines the preparation of this pharmacologically important scaffold. When we applied a linear n-pentane instead, only 2° C–H activation products were acquired with no 1° C–H activation observed in this system (7c). We next investigated the substrate scope of this multi-step cyclization reaction with various aniline derivatives. The experimental results demonstrated that structurally diverse substituted anilines could efficiently react with cyclohexane to construct indole frameworks in good to excellent yields (51–95%, 8c–50c). The transformation showed remarkable functional group tolerance, accommodating both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents with high efficiency. Firstly, anilines with electron-donating groups including alkyls (Me, Et, tBu, iPr, 8c–11c) and ethers (OEt, OPh, OCF₃, 12c–14c) performed particularly well (almost around 90%). Moreover, the reaction also exhibited good to excellent compatibility towards various electron-withdrawing groups, including halogens (F, Cl, Br, I, 18c–21c), trifluoromethyl (22c), cyano (24c), esters (COOMe, COOEt, 24c, 25c), carbonyls (Ac, COPh, 26c, 27c), and sulfonyl derivatives (SO2Me, SO2NH2, 28c, 29c). Remarkably, hydroxyl-containing moieties, including phenolic (81%, 16c) and aliphatic alcohol groups (87%, 15c), and drug-relevant sulfamide units (61%, 29c) remain intact without protective strategies, providing a wide chemical space for further diversification. Following steric evaluation revealed that meta-substituted anilines (30c–34c) afforded slightly lower yields (59–73%) relative to their para-substituted counterparts. Multi-substituted substrates performed well regardless of electronic properties, with both mixed electron-donating/withdrawing combinations (35c, 36c, 38c, 41c) and bis-electron-withdrawing systems (37c, 39c, 40c, 42c, 43c) maintaining moderate to good reaction efficiency. Notably, the indole product (48c, 52%) obtained from the reaction of a free carboxylic acid-containing aniline with cycloheptane serves as a key intermediate for A-FABP inhibitors, demonstrating the practical utility of this transformation in medicinal chemistry. Heteroaromatic amines involving quinoline and benzofuran motifs were also compatible, affording the corresponding indole product in moderate yields (49c, 50c). The transformation’s remarkable substrate versatility and functional group tolerance prompted our exploration of its applications in complex molecular settings. Impressively, the commercially available sulfonamide antibiotic Sulfamethazine was directly converted to its corresponding indole derivative (51c) in 65% yield under standard conditions, without requiring protection of the pharmacophoric sulfonamide group. Furthermore, a series of representative natural products and pharmaceutical molecules, including Borneol (52c), DL-Menthol (53c), Carvacrol (54c), Thymol (55c), Naproxen (56c), Propafenone (57c), Vanillylacetone (58c), and Vitamin E (59c), were selected for derivatization studies. These substrates could be readily converted into corresponding arylamines under mild conditions, followed by successful photoinduced cross-coupling and cyclization to afford the desired indole derivatives in good to excellent yields (65–85%). These successful examples not only broaden synthetic access to medicinally relevant indole scaffolds but also provide a general platform for the structural diversification of bioactive natural products and pharmaceuticals through photo-driven C(sp3)–H activation of alkanes. Moreover, we executed a gram-scale synthesis employing 4-methoxyaniline 1b (10.0 g, 81.2 mmol), achieving product 1c in 91.9% isolated yield with no obvious efficiency loss (more details see Fig. S12). To further increase the light utilization efficiency, a well-designed continuous-flow photocatalytic micro-reactor was used, capable to afford similar results to those of the batch reaction with a reduced time and attenuated light irradiation (more details see Fig. S13). This successful scale-up and flow synthesis not only confirms the robustness of our methodology but also highlights its potential for industrial manufacturing applications.

Delightfully, a noticeable advance in constructing the indole skeleton has been achieved through an iron-catalyzed photoredox one-step coupling of alkanes with arylamines, although some limitations, including the difficult activation of the primary C–H bonds of alkanes and the exclusive formation of 2,3-disubstituted indoles, still exist. Meanwhile, carboxylic acids serve as versatile radical precursors due to their advantageous properties: environmental benignity, cost efficiency, general stability in air and moisture, ease of storage and handling, and natural abundance (such as amino acids, fatty acids, etc.). The decarboxylation process exhibits thermodynamic driving force with CO2 as a byproduct, making it a powerful strategy for constructing C–C, C–N, C–O, and C–X bonds53,54,55,56. Significantly, the Fe-LMCT process demonstrates remarkable versatility, proving effective not only for alkane activation but also for facilitating efficient carboxylic acid transformations57,58,59. In order to break through the above limitations and expand the application scope of this bifunctional iron-catalyzed system, we then broadened our focus to include carboxylic acids with wider sources and varieties than alkanes as substrates.

At the outset of our investigation, we selected the reaction between cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (1a′) and 4-methoxybenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate (1b′) as the model system for condition optimization of the decarboxylative indole construction process (more details see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). After systematic investigation of catalysts, ligands, additives, and solvents, we successfully established the following optimal reaction conditions. The combination of FeCl3·6H2O (0.1 equiv.) as an inexpensive photocatalyst as well as a Lewis-acid catalyst, di-(2-picolyl)amine L1 (0.2 equiv.) as the ligand, and DABCO (1 equiv.) and KHSO4 (5 equiv.) as additives in MeCN under 30 W 405 nm LED irradiation provided the target indole product 1c in 88% yield (Table S2, entry 15). Various iron catalysts, including FeBr3, Fe(OTf)3, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, FeSO4·7H2O, and Fe(acac)3, all showed limited activity (entries 35–42). Interestingly, CeCl3 exhibited moderate catalytic efficiency (67% yield, entry 44), while other metal chlorides, including ZrCl4 and CuCl2, presented no activity (entries 45−48). Control experiments established the essential roles of each kind of reaction component for successful transformation (entries 55–59). Furthermore, the stoichiometric ratio between carboxylic acids and aryldiazonium salts critically influenced the reaction outcome, as a molar ratio lower than 2:1 led to diminished yields compared to the optimal conditions (Table S3). Building upon our target to establish a Swiss-Army-knife-type catalytic platform for one-pot synthesis of indoles, we further sought to expand this methodology to a direct one-pot coupling between arylamines and carboxylic acids (Tables S4 and S5). Initial one-step studies revealed limited efficiency, with the transformation yielding only 54% even after extensive condition optimization (Table S4, entry 3). To address this issue, we devised an improved one-pot two-step strategy involving an initial arylamine diazotization at 0 °C and a following iron-catalyzed decarboxylative cyclization in situ without intermediate purification. This optimized protocol significantly promoted the yield of target indole product 1c to 86% (Table S5, entry 2).

With the optimized one-pot two-step protocol established, we next evaluated the reaction scope using various carboxylic acids and arylamines (Fig. 3). The investigation first focused on secondary carboxylic acids. Cyclic substrates involving substituted cyclohexanecarboxylic acids (bearing methyl, propyl, ester, hydroxy, amide, and fluoro groups; 60c–65c) and carbocyclic acids of varying ring sizes (5- to 7-membered rings; 1c, 66c, 67c) were all proved to be effective substrates, affording the corresponding indole products in 68–87% yields. Notably, with 1-methylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid as a substrate, our optimized decarboxylation protocol enabled the robust and efficient construction of a pharmacologically valuable piperidine-fused indole scaffold (68c–70c). This privileged scaffold serves as a versatile synthetic intermediate and has been strategically employed in the concise synthesis of biologically active compounds, such as Dimebolin (69c) and Mebhydrolin (70c). Similarly, a series of secondary carboxylic acids with varying carbon chain lengths (71c–77c, C4–C9) and their phenyl-substituted analogs (78c–82c) efficiently delivered indole frameworks in 74–84% yields. Subsequent investigation of phenylpropanoic acid substrates demonstrated that aromatic analogs bearing diverse substituents (OMe, Cl, Br, I, CN) could be transformed into corresponding indole derivatives (83c–89c) in good yields. Nevertheless, comparative studies revealed a little lower reactivity of general primary carboxylic acids relative to their secondary counterparts. To overcome this obstacle, we developed an optimized protocol (details see Table S6) by modulating the catalyst and additive loading and adjusting the irradiation wavelength to 365 nm. Through condition screening, the reaction efficiency using primary carboxylic acids as the substrate was improved by three times (21% → 61%). Depending on these efforts, linear primary carboxylic acids with different carbon chain lengths (C4–C15) all participated effectively in the reaction, affording C3-substituted indole derivatives (93c–104c) in moderate yields. As the alkyl chain length increased (>C11), the yields showed a slight decrease due to the markedly reduced solubility of acid substrates in MeCN solvent. More propionic acid derivatives bearing diverse functional groups, including alkyl (91c, 92c), halogens (105c, 106c), esters (107c–109c), thioesters (110c), and amides (111c), were also converted to the corresponding indole derivatives in satisfactory yields, showing the excellent functional group compatibility of this method. To evaluate the synthetic utility of this one-pot two-step methodology, we then investigated its application to structurally diverse natural products and bioactive pharmaceutical compounds. The reaction demonstrated remarkable versatility in accommodating various natural fatty acids, including saturated (Lauric acid 113c, Myristic acid 114c, and Palmitic acid 115c) and unsaturated (Oleic acid 116c) variants, as well as the therapeutic agent Azelaic acid (117c), all of which were efficiently converted to their corresponding indole derivatives. The methodology was further extended to primary carboxylic acid derivatives derived from biologically relevant scaffolds and drugs, including Geraniol (118c), Vanillylacetone (119c), Triclosan (120c), Procaine (121c), and Estrone (122c), and the results demonstrated the success of the cross-conjugation between these functional molecules with the indole motif under mild conditions and convenient operation.

Reaction conditions: step 1: b (0.2 mmol), tBuONO (1 equiv.), HBF4 (0.7 equiv.), EtOH (50 μL); step 2: a’ (3 equiv.), FeCl3·6H2O (10 mol%), L1 (20 mol%), DABCO (1 equiv.), KHSO4 (5 equiv.), MeCN (2 mL), N2, rt, 30 W 405 nm LED, 12 h. a4 equiv. of (a’), 20 mol% of FeCl3·6H2O, 1.5 equiv. of DABCO and 30 W 365 nm LEDs were used. Isolated yield.

The seven-membered ring fused with an indole core is known as cyclohepta[b]indole, a privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry. Compounds containing this structural motif exhibit diverse pharmacological activities, including: A-FABP inhibitor, LTB4 inhibitor, SIRT1 inhibitor IV, and anti-tubercular agent60. Building upon these significant medicinal properties, cycloheptanecarboxylic acid was chosen as a model substrate to evaluate the compatibility of the decarboxylative indolization protocol with various aromatic amines, and meanwhile, construct an abundant molecular library for the functionalized cyclohepta[b]indole derivatives (Fig. 4). Gratifyingly, cycloheptanecarboxylic acid exhibited excellent reactivity in this bifunctional iron-catalyzed photoredox system, efficiently affording the corresponding cyclohepta[b]indoles (123c–152c) in moderate to excellent yields (43–84%). This transformation exhibited remarkable versatility by readily accommodating both para- and ortho-substituted aryl amines containing diverse functional groups, including alkyl (123c, 124c), ether (125c–129c), phenolic (128c), alcohol (129c), fluoro (130c, 133c), chloro (131c, 134c), bromo (132c, 135c), trifluoromethyl (136c), nitrile (137c), ester (138c–140c), sulfone (141c), sulfonamide (142c) and carbonyl (143c, 144c). A particularly noteworthy example was the successful application to ester-substituted aniline (139c), as the resulting indole derivatives serve as key intermediates for adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein (A-FABP) inhibitors, underscoring the methodology’s medicinal chemistry relevance. The protocol also proved effective for disubstituted arylamines (145c–147c), enabling access to highly substituted indole scaffolds in competitive yields. 8-Aminoquinoline as a heteroaromatic substrate was tried next, furnishing the corresponding indole in 43% yield (148c). A clear electronic effect was observed in this library, with electron-donating groups presenting enhanced reactivity relative to electron-withdrawing substituents. Furthermore, the methodology successfully incorporated other bioactive motifs from natural products and pharmaceuticals with the valuable cyclohepta[b]indole core, including Borneol (149c), Carvacrol (150c), Thymol (151c), and Naproxen (152c), endowing this molecular library with additional potential value for new drug discovery.

Reaction conditions: step 1: b (0.2 mmol), tBuONO (1 equiv.), HBF4 (0.7 equiv.), EtOH (50 μL); step 2: a’ (3 equiv.), FeCl3·6H2O (10 mol%), L1 (20 mol%), DABCO (1 equiv.), KHSO4 (5 equiv.), MeCN (2 mL), N2, rt, 30 W 405 nm LED, 12 h. Isolated yield. aThe reaction was performed at 50 °C. bThe reaction was performed at 80 °C.

Depending on the convenience, practicality, and great functional group tolerance of our method, we next implemented this Swiss-Army-knife-type catalytic strategy for the route improvement of the total synthesis of four pharmaceutically valuable indole-containing drugs (Fig. 5). Initially, the antidepressant Iprindole61,62 (5d), traditionally prepared via a four-step sequence under harsh reaction conditions, was efficiently synthesized through our streamlined two-step protocol under mild conditions, achieving 75% isolated yield (vs 43% overall yield for the 4-step route) with significantly enhanced operational efficiency. Mebhydrolin63,64 (70d), a clinically used antihistamine for histamine-mediated allergic diseases, was efficiently synthesized via our one-pot decarboxylation/cyclization protocol using commercially available aniline and 1-methylpiperidine-4-carboxylic acid as starting materials. This optimized approach afforded the target compound in 56% total yield, representing a substantial improvement over the conventional multistep synthesis (47% overall yield after four steps) and simultaneously enhancing both operational safety and atom economy. Melatonin65,66 (112c), as an important endogenous compound with multiple biological activities, has been scientifically demonstrated to possess various pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, energy metabolism regulation, skin barrier protection, and glucose metabolism improvement. Although several synthetic routes have been developed for industrial production, these methods are generally limited by their multi-step procedures and toxic reagent usage. In our work, the target molecule was efficiently constructed in just one step from readily available starting materials, achieving a yield of 57% with notably improved synthetic efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Finally, the A-FABP inhibitor 67,68 (139d) acts on a therapeutic target with dual mechanisms of action that regulate fatty acid transport and suppress inflammatory responses. However, its traditional synthetic methods require six laborious steps: hydrolysis, diazotization, reduction, cyclization, esterification, and hydrolysis. In contrast, an innovative synthetic route provided herein could prepare the target molecule in just two steps: initial construction of the indole core via decarboxylation or alkane activation, followed by benzyl protection/hydrolysis to afford the final product. This streamlined protocol achieves a 50% overall yield—nearly doubling the yield compared to traditional methods—while eliminating hazardous diazotization reactions and multiple purification steps, thereby significantly enhancing both synthetic efficiency and operational safety. To further demonstrate the application potential for this methodology, we attempted and smoothly accomplished decagram-scale production of both Iprindole (73.3%) and Melatonin (54.7%), exhibiting scalability and process robustness with minimal yield variation compared to small-scale reactions. This breakthrough strategy effectively addresses critical industrialization challenges through the complete elimination of hazardous diazotization steps while rigorously adhering to green chemistry principles, thereby offering a sustainable and industrially viable solution for large-scale pharmaceutical manufacturing.

To gain insights into the bifunctional iron-catalyzed photoredox indolization pathway, we systematically conducted a series of mechanistic experiments (Fig. 6). Firstly, the radicals produced in the iron-catalyzed system were surveyed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) in the presence of 5,5-dimethyl−1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the spin trapping agent. As shown in Fig. 6a, irradiation of the 1a/FeCl3 ∙ 6H2O/DMPO system generated a sextet signal (AN = 14.51 G, AH = 21.52 G, and g = 2.0053) which was attributable to a carbon-centered radical69. Only a ferric signal could be observed without light, indicating that cyclohexane 1a was activated to a cyclohexyl radical through iron photocatalysis. Furthermore, after the addition of substrate 1b′ into this mixture, a triplet signal (AN = 14.39 G, AH = 14.59 G, and g = 2.0086) ascribed to a nitrogen-centered radical70 was detected instead under irradiation, suggesting the rapid radical-trapping nature between the cyclohexyl radical and 1b′ (more details see Figs. S3 and S4). Assisted by L1 and DABCO, the same carbon-centered and the following nitrogen-centered radicals were both acquired via photoinduced LMCT pathway with cyclohexanecarboxylic acid 1a′ as substrate, demonstrating similar radical generation and capturing processes as 1a (more details see Figs. S5 and S6). Subsequent radical trapping experiments using superstoichiometric 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) produced the adducts of carbon radicals and TEMPO and were verified by GC-MS analysis, further indicating the achievement of radical-mediated C(sp3)–H activation/decarboxylation steps (Fig. 6b, more details see Figs. S1 and S2). Kinetic isotopic effect (KIE) studies with separate kinetic experiments were next carried out to gain insights into the C(sp3)–H cleavage step (Fig. 6c). The KIE values given by KH/KD and PH/PD were measured as 3.10 and 3.19 by using (1) 1a/1a-d12 respectively as substrates or (2) a 1:1 mixture of 1a and 1a-d12 as substrates to produce 1c (more details see SI, part IV, iii). These results implied one of the alkyl C(sp3)–H activation processes to be the “rate-determining step” for this system. Moreover, the quantum yield of the model reaction was calculated as 0.019 (more details see SI, part IV, vii), reflecting that radical chain processes made little contribution in the indole construction strategy.71

To further elucidate the mechanism of the cyclization reaction, we designed and performed a series of control experiments. Initial experiments replacing the in situ diazotization system (aniline/tert-butyl nitrite/HBF4) with pre-formed diazonium salt 1b′ demonstrated efficient indole synthesis using only FeCl3∙6H2O as the catalyst without Brønsted acid additives (Fig. 6d-1). This preliminarily confirmed iron’s dual role beyond photocatalysis: as a Lewis acid catalyst for cyclization. Subsequent substitution of diazonium salts with putative azo intermediates (1g) proceeded smoothly for indole construction under iron-mediated Lewis acid catalysis, with negligible dependence on cyclohexane presence (Fig. 6d-2, 6d-3). Further investigation with hydrazone isomer 1h (double-bond migrated derivative of 1g) also afforded the indolization product in an excellent yield (87%) (Fig. 6d-4). Collectively, these experiments robustly demonstrate iron’s bifunctionality: enabling both photocatalytic C(sp3)–H activation and Lewis acid-driven sigmatropic rearrangement cyclization within a unified system. Building upon these findings, parallel conclusions were substantiated when employing carboxylic acids as alternative substrates to alkanes (Fig. 6e). Through analogous control experiments, we confirmed iron’s dual catalytic functionality in simultaneously enabling photocatalytic decarboxylation and Lewis acid-mediated indolization. Importantly, the acidic (HBF4 and KHSO4) or alkaline (DABCO) additives present in the system were excluded from participating in the cyclization stage. To further elucidate the role of these additives in the decarboxylation regime, we conducted subsequent mechanistic investigations with a pre-synthesized Fe(III)-carboxylate complex [Fe]-1 through Gueŕinot’s method72. As presented in Fig. 6f-1, spectroscopic analysis revealed that complex [Fe]−1 exhibits strong absorption at 405 nm, identifying it as the putative photosensitizer responsible for generating alkyl radicals via a LMCT process (more details see Figs. S8 and S9). Reaction of [Fe]−1 with diazonium salt 1b′ afforded the radical-trapped azo product 1g in a moderate yield (Fig. 6f-2). In this system, stoichiometric Lewis base DABCO masks iron’s Lewis acidity, almost inhibiting the cyclization step. Notably, even excess Brønsted acid KHSO4 failed to promote cyclization under these conditions. Removal of DABCO partially restored iron’s Lewis acidity, resulting in enhanced indolization efficiency (Fig. 6f-3). Further supplementation with FeCl3∙6H2O as an exogenous Lewis acid catalyst quantitatively converted intermediate 1g into the target indole product (Fig. 6f-4). These control experiments definitively establish that: 1. The sigmatropic rearrangement cyclization is exclusively driven by iron’s Lewis acidity; 2. DABCO functions solely to facilitate carboxylate-iron coordination; 3. Brønsted acids primarily mediate diazonium formation and pH modulation. Overall, neither additive participates in the cyclization process, further confirming iron’s dual catalytic functionality as we design.

Integrating our mechanistic investigations with prior literature reports7,41,43,73,74, we propose a plausible bifunctional iron-catalyzed indolization pathway for C(sp3)–H/decarboxylative functionalization via a photoinduced LMCT and Lewis acid-driven mechanism (Fig. 7). In the decarboxylation system, the coordination of the carboxylic acid a′ to Fe(III) species A is proposed to form a Fe(III)−carboxylate complex B (similar to complex [Fe]−1) Photoexcitation of the iron complex B generates its excited state C and renders an intramolecular LMCT event to afford the reduced Fe(II) complex D and a carboxyl radical, which will produce the desired alkyl radical E after CO2 extrusion. When using alkane a as substrate, irradiation of the Fe(III)–Cl complex I gives the excited state II, and a subsequent LMCT generates an intermediate Fe(II) complex III and a highly active chlorine radical IV. A following hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from alkane a to IV results in the same alkyl radical E. The radical E provided by both cycles selectively couples with aryldiazonium salt b′, delivering a highly reactive azo radical cation intermediate F. Within the Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox catalytic cycle, F undergoes facile single-electron transfer (SET) with Fe(II) to afford the neutral Fe(III)−diazene complex G. Sequential tautomerization via intramolecular proton transfer converts G to a hydrazone derivative H and a reactive enamine intermediate I, which subsequently proceeds a Fischer-type [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to afford the diimine intermediate J through iron catalysis. Finally, J undergoes successive isomerization and aromatization-driven cyclization to form hemiaminal intermediate M after releasing Fe(III)-NH3, finally affording the target indole product c.

Discussion

In summary, we have described an integrated strategy of merging iron photocatalysis and iron Lewis acid catalysis for the one-pot synthesis of indoles from arylamines and alkanes or carboxylic acids. This catalytic approach exhibits remarkable efficiency while functioning in a redox-neutral and sustainable manner, thereby obviating the necessity for an external photocatalyst or HAT catalyst. Moreover, the reaction offers operational simplicity, mild reaction conditions, and broad functional group compatibility, establishing a versatile platform for decarboxylation functionalization and alkane activation. The method enables direct access to a wide range of indole derivatives, including late-stage modification and total synthesis of valuable bioactive molecules and drug intermediates, with high efficiency and scalability. Mechanistic studies confirm the dual role of iron in both photocatalytic activation and Lewis acid-mediated sigmatropic rearrangement indolization. This work provides a sustainable and industrially viable approach to indole synthesis, highlighting the potential of iron-based multifunctional catalysis in modern organic synthesis.

Methods

General procedure for one-step indole synthesis using arylamine and alkane

Arylamine b (0.2 mmol), alkane a (10 equiv.), FeCl3·6H2O (10 mol%, 5.4 mg), MeCN (2 mL), tert-butyl nitrite (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv., 20.6 mg), and HBF4 (48 wt% in H2O, 0.7 equiv., 25.6 mg) were added into a 10 mL Schlenk tube with a magnetic stir bar in sequence. The mixture was allowed to stir under N2 with the irradiation of a 30 W 405 nm LED at room temperature for 12 h. Upon completion, the reaction solution was diluted with 25 mL of EtOAc and washed with deionized water. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (PE/EtOAc = 10: 1 – 1: 1) to give the desired product.

General procedure for one-pot two-step indole synthesis using arylamine and carboxylic acid

Arylamine b (0.2 mmol), EtOH (50 μL), and HBF4 (48 wt.% in H2O, 0.7 equiv., 25.6 mg) were added into a 10 mL Schlenk tube with a magnetic stir bar in sequence. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and tert-butyl nitrite (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv., 20.6 mg) was added dropwise. After stirring at 0 °C for 30 min, carboxylic acids a′ (3 equiv. for secondary carboxylic acids and 4 equiv. for primary carboxylic acids), FeCl3·6H2O (10 mol% for secondary carboxylic acids and 20 mol% for primary carboxylic acids), L1 (20 mol%, 8.0 mg), DABCO (1 equiv. for secondary carboxylic acids and 1.5 equiv. for primary carboxylic acids), KHSO4 (1 mmol, 5 equiv., 136.1 mg), and MeCN (2 mL) were added. The mixture was allowed to stir under N2 with the irradiation of a 30 W 405 nm LED at room temperature for 12 h. Upon completion, the reaction solution was diluted with 25 mL of EtOAc and washed with deionized water. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by silica gel flash column chromatography (PE/EtOAc =10: 1 – 1: 1) to give the desired product.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are provided within the paper and its supplementary information files, and are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Chen, F.-E. & Huang, J. Reserpine: a challenge for total synthesis of natural products. Chem. Rev. 105, 4671–4706 (2005).

Heravi, M. M., Rohani, S., Zadsirjan, V. & Zahedi, N. Fischer indole synthesis applied to the total synthesis of natural products. RSC Adv. 7, 52852–52887 (2017).

Liu, X.-Y. & Qin, Y. Indole alkaloid synthesis facilitated by photoredox catalytic radical cascade reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1877–1891 (2019).

Kochanowska-Karamyan, A. J. & Hamann, M. T. Marine indole alkaloids: potential new drug leads for the control of depression and anxiety. Chem. Rev. 110, 4489–4497 (2010).

Thanikachalam, P. V., Maurya, R. K., Garg, V. & Monga, V. An insight into the medicinal perspective of synthetic analogs of indole: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 180, 562–612 (2019).

Heravi, M. M. & Zadsirjan, V. Prescribed drugs containing nitrogen heterocycles: an overview. RSC Adv. 10, 44247–44311 (2020).

Gore, P., Hughes, G. & Ritchie, E. The Fischer indole synthesis. Nature 164, 835–835 (1949).

Humphrey, G. R. & Kuethe, J. T. Practical methodologies for the synthesis of indoles. Chem. Rev. 106, 2875–2911 (2006).

Taber, D. F. & Tirunahari, P. K. Indole synthesis: a review and proposed classification. Tetrahedron 67, 7195–7210 (2011).

Sahu, S., Banerjee, A., Kundu, S., Bhattacharyya, A. & Maji, M. S. Synthesis of functionalized indoles via cascade benzannulation strategies: a decade’s overview. Org. Biomol. Chem. 20, 3029–3042 (2022).

Bugaenko, D. I., Karchava, A. V. & Yurovskaya, M. A. Synthesis of indoles: recent advances. Russ. Chem. Rev. 88, 99–159 (2019).

Inman, M. & Moody, C. J. Indole synthesis–something old, something new. Chem. Sci. 4, 29–41 (2013).

Matcha, K. & Antonchick, A. P. Cascade multicomponent synthesis of indoles, pyrazoles, and pyridazinones by functionalization of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 11960–11964 (2014).

Yu, X.-L., Chen, J.-R., Chen, D.-Z. & Xiao, W.-J. Visible-light-induced photocatalytic azotrifluoromethylation of alkenes with aryldiazonium salts and sodium triflinate. Chem. Commun. 52, 8275–8278 (2016).

Haag, B. A., Zhang, Z.-G., Li, J.-S. & Knochel, P. Fischer indole synthesis with organozinc reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 9513–9516 (2010).

Govaerts, S., Nakamura, K., Constantin, T. & Leonori, D. A halogen-atom transfer (XAT)-based approach to indole synthesis using aryl diazonium salts and alkyl iodides. Org. Lett. 24, 7883–7887 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Transition-metal free C–N bond formation from alkyl iodides and diazonium salts via halogen-atom transfer. Nat. Commun. 13, 7961 (2022).

Angnes, R. A., Potnis, C., Liang, S., Correia, C. R. D. & Hammond, G. B. Photoredox-catalyzed synthesis of alkylaryldiazenes: formal deformylative C–N bond formation with alkyl radicals. J. Org. Chem. 85, 4153–4164 (2020).

Heitz, D. R., Tellis, J. C. & Molander, G. A. Photochemical nickel-catalyzed C–H arylation: synthetic scope and mechanistic investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12715–12718 (2016).

Abderrazak, Y., Bhattacharyya, A. & Reiser, O. Visible-light-induced homolysis of earth-abundant metal-substrate complexes: a complementary activation strategy in photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21100–21115 (2021).

Juliá, F. Ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) photochemistry at 3d-metal complexes: an emerging tool for sustainable organic synthesis. ChemCatChem 14, e202200916 (2022).

Li, C., Kong, X. Y., Tan, Z. H., Yang, C. T. & Soo, H. S. Emergence of ligand-to-metal charge transfer in homogeneous photocatalysis and photosensitization. Chem. Phys. Rev. 3, 021303 (2022).

Chang, L. et al. Resurgence and advancement of photochemical hydrogen atom transfer processes in selective alkane functionalizations. Chem. Sci. 14, 6841–6859 (2023).

Ji, C.-L. et al. Photoinduced late-stage radical decarboxylative and deoxygenative coupling of complex carboxylic acids and their derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202423113 (2025).

Holmberg-Douglas, N. & Nicewicz, D. A. Photoredox-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. Chem. Rev. 122, 1925–2016 (2021).

Dalton, T., Faber, T. & Glorius, F. C–H activation: toward sustainability and applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 245–261 (2021).

Capaldo, L., Ravelli, D. & Fagnoni, M. Direct photocatalyzed hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) for aliphatic C–H bonds elaboration. Chem. Rev. 122, 1875–1924 (2021).

Zhang, J. & Rueping, M. Metallaphotoredox catalysis for sp3C–H functionalizations through hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 4099–4120 (2023).

Hu, A., Guo, J.-J., Pan, H. & Zuo, Z. Selective functionalization of methane, ethane, and higher alkanes by cerium photocatalysis. Science 361, 668–672 (2018).

Wen, L. et al. Multiplicative enhancement of stereoenrichment by a single catalyst for deracemization of alcohols. Science 382, 458–464 (2023).

Campbell, B. M. et al. Electrophotocatalytic perfluoroalkylation by LMCT excitation of Ag(II) perfluoroalkyl carboxylates. Science 383, 279–284 (2024).

Chinchole, A., Henriquez, M. A., Cortes-Arriagada, D., Cabrera, A. R. & Reiser, O. Iron(III)-light-induced homolysis: a dual photocatalytic approach for the hydroacylation of alkenes using acyl radicals via direct HAT from aldehydes. ACS Catal. 12, 13549–13554 (2022).

Li, Q. Y. et al. Decarboxylative cross-nucleophile coupling via ligand-to-metal charge transfer photoexcitation of Cu(II) carboxylates. Nat. Chem. 14, 94–99 (2022).

Lutovsky, G. A., Gockel, S. N., Bundesmann, M. W., Bagley, S. W. & Yoon, T. P. Iron-mediated modular decarboxylative cross-nucleophile coupling. Chem 9, 1610–1621 (2023).

Wang, M., Huang, Y. & Hu, P. Terminal C(sp3)–H borylation through intermolecular radical sampling. Science 383, 537–544 (2024).

Wenger, O. S. Photoactive complexes with earth-abundant metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13522–13533 (2018).

de Groot, L. H., Ilic, A., Schwarz, J. & Wärnmark, K. Iron photoredox catalysis–past, present, and future. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9369–9388 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Controllable C–H alkylation of polyethers via iron photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7612–7620 (2023).

Tu, J.-L., Hu, A.-M., Guo, L. & Xia, W. Iron-catalyzed C.(sp3)–H borylation, thiolation, and sulfinylation enabled by photoinduced ligand-to-metal charge transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7600–7611 (2023).

Cao, Y., Huang, C. & Lu, Q. Photoelectrochemically driven iron-catalysed C(sp3)−H borylation of alkanes. Nat. Synth. 3, 537–544 (2024).

Jin, Y. et al. Convenient C(sp3)–H bond functionalisation of light alkanes and other compounds by iron photocatalysis. Green Chem. 23, 6984–6989 (2021).

Jin, Y. et al. Photo-induced direct alkynylation of methane and other light alkanes by iron catalysis. Green Chem. 23, 9406–9411 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Bifunctional iron-catalyzed alkyne Z-selective hydroalkylation and tandem Z-E inversion via radical molding and flipping. Nat. Commun. 15, 8619 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Selective arene photonitration via iron-complex β-homolysis. JACS Au 4, 4899–4909 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Iron-catalyzed Ipso-nitration of aryl borides via visible-light-induced β-homolysis. ACS Catal. 15, 3306–3313 (2025).

Geraci, A. Baudoin O. Fe-Catalyzed α-C(sp3)−H amination of N-heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202417414 (2025).

Song, G. et al. Light-promoted efficient generation of Fe(I) to initiate amination. ACS Catal. 14, 4968–4974 (2024).

Tang, S.-X., Huang, G.-W., Cheng, J.-K. & Wang, F. meta-Selective C–H amination of aryl amines via protonation-enabled polarity inversion in homolytic aromatic substitution. CCS Chem. 7, 3606–3615 (2025).

Fürstner, A. Iron catalysis in organic synthesis: a critical assessment of what it takes to make this base metal a multitasking champion. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 778–789 (2016).

Riehl, P. S. & Schindler, C. S. Lewis acid-catalyzed carbonyl–olefin metathesis. Trends Chem. 1, 272–273 (2019).

Ludwig, J. R. S. C. S. lewis acid catalyzed carbonyl-olefin metathesis. Synlett 28, 1501–1509 (2017).

Tu, J.-L., Zhu, Y., Li, P. & Huang, B. Visible-light induced direct C(sp3)–H functionalization: recent advances and future prospects. Org. Chem. Front. 11, 5278–5305 (2024).

Jin, Y. & Fu, H. Visible-light photoredox decarboxylative couplings. Asian J. Org. Chem. 6, 368–385 (2017).

Xuan, J., Zhang, Z.-G. & Xiao, W.-J. Visible-light-induced decarboxylative functionalization of carboxylic acids and their derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 15632–15641 (2015).

Varenikov, A., Shapiro, E. & Gandelman, M. Decarboxylative halogenation of organic compounds. Chem. Rev. 121, 412–484 (2020).

Kitcatt, D. M., Nicolle, S. & Lee, A.-L. Direct decarboxylative Giese reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 1415–1453 (2022).

Li, Z., Wang, X., Xia, S. & Jin, J. Ligand-accelerated iron photocatalysis enabling decarboxylative alkylation of heteroarenes. Org. Lett. 21, 4259–4265 (2019).

Fernández-García, S., Chantzakou, V. O. & Juliá-Hernández, F. Direct decarboxylation of trifluoroacetates enabled by iron photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202311984 (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Iron photocatalysis via Brønsted acid-unlocked ligand-to-metal charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 6115 (2024).

Stempel, E. & Gaich, T. Cyclohepta[b]indoles: a privileged structure motif in natural products and drug design. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 2390–2402 (2016).

Talaz, O. & Saracoglu, N. A study on the synthesis of structural analogs of bis-indole alkaloid caulerpin: a step-by-step synthesis of a cyclic indole-tetramer. Tetrahedron 66, 1902–1910 (2010).

Zhu, C., Zhang, X., Lian, X. & Ma, S. One-pot approach to installing eight-membered rings onto indoles. Angew. Chem. 51, 7817–7820 (2012).

Butler, K. V. et al. Rational design and simple chemistry yield a superior, neuroprotective HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10842–10846 (2010).

Li, J., Lai, Z., Zhang, W., Zeng, L. & Cui, S. Modular assembly of indole alkaloids enabled by multicomponent reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 4806 (2023).

Xiong, R. et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of tryptamine salicylic acid derivatives as potential antitumor agents. MedChemComm 10, 573–583 (2019).

Yokoo, H., Ohsaki, A., Kagechika, H. & Hirano, T. Structural development of canthin-5, 6-dione moiety as a fluorescent dye and its application to novel fluorescent sensors. Tetrahedron 72, 5872–5879 (2016).

Barf, T. et al. N-Benzyl-indolo carboxylic acids: design and synthesis of potent and selective adipocyte fatty-acid binding protein (A-FABP) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 1745–1748 (2009).

Dawande, S. G. et al. Rhodium enalcarbenoids: direct synthesis of indoles by rhodium (II)-catalyzed [4+2] benzannulation of pyrroles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4076–4080 (2014).

Buettner, G. R. Spin trapping: ESR parameters of spin adducts 1474 1528V. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 3, 259–303 (1987).

Han, M. et al. Oxygen vacancy boosts nitrogen-centered radical coupling initiated by primary amine electrooxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 33893–33902 (2024).

Simmons, E. M. & Hartwig, J. F. On the interpretation of deuterium kinetic isotope effects in C–H bond functionalizations by transition-metal complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 3066–3072 (2012).

Innocent, M., Lalande, G., Cam, F., Aubineau, T. & Guérinot, A. Iron-catalyzed, light-driven decarboxylative oxygenation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 26, e202300892 (2023).

Blank, O. & Heinrich, M. R. Carbodiazenylation of olefins by radical iodine transfer and addition to arenediazonium salts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 4331–4334 (2006).

Gavelle, S., Innocent, M., Aubineau, T. & Guérinot, A. Photoinduced ligand-to-metal charge transfer of carboxylates: decarboxylative functionalizations, lactonizations, and rearrangements. Adv. Synth. Catal. 364, 4189–4230 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Huihui Wan and Dr. Yuming Sun in the DUT Instrumental Analysis Center for their great help in HRMS analysis. We acknowledge the support of the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2024-MSLH-080 for Y.J.), the National College Student Innovation Training Program (20251014110304 for J.G., 20241014110019 for Y.J.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (DUT24BK042 for Y.J.), and the Young Teachers Incentive Project from the School of Chemistry @DUT (for Y.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J. led this project. L.W. and Y.J. conceived and designed the experiments. L.W., S.L., H.Z., R.X., F.Q., W.H., Z.G., and J.G. performed and analyzed the experiments. L.W., S.L., and Y.J. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Carlos Roque Correia and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Liu, S., Zi, H. et al. Photo-driven bifunctional iron-catalyzed one-pot assembling of indoles from arylamines and alkanes/carboxylic acids. Nat Commun 17, 1469 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68208-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68208-z