Abstract

In Fabry disease (FD, OMIM #301500), a rare lysosomal storage disorder, the glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor lucerastat acts as substrate reduction therapy. The Phase 3, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-month, randomized clinical trial, MODIFY (NCT03425539), aimed to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of lucerastat in adults with FD with moderate-to-severe neuropathic pain. The single-arm, open-label extension (OLE) (NCT03737214) evaluated the longer-term safety and tolerability of lucerastat over 72 months. Lucerastat 1000 mg twice daily (n = 80), compared with placebo (n = 37), failed to affect neuropathic pain at Month-6, with no significant difference between treatment groups (LSM difference –0.42 [95% CI –1.23, 0.40], p = 0.32) (primary endpoint). In contrast, a decrease in baseline plasma Gb3 was observed at Month-6 in lucerastat-treated participants but not placebo-treated participants (LSM difference –873.53 ng/mL [95% CI –1097.53, –649.53], p < 0.0001; NS due to hierarchical testing). In an unplanned OLE Month-18 interim analysis, the eGFR slope (mL/min/1.73m2/year) in 93 participants with pre- and post-randomization (23-month median lucerastat exposure) eGFR data was –3.50 (–5.04, –1.969) and –1.48 (–2.64, –0.33), respectively. Lucerastat was safe and well tolerated. Lucerastat’s strong pharmacodynamic effect did not translate into an effect on neuropathic pain. The potential effect of lucerastat on renal function requires further investigation (Trial registration NCT03425539, NCT03737214; 2017-003369-85, 2018-002210-12. The studies were sponsored by Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fabry disease (FD; OMIM 301500) is a rare, genetic, X-linked lysosomal storage disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the GLA gene, which encodes the α-galactosidase A (α-GalA) enzyme1. Deficient α-GalA activity results in globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) accumulation in lysosomes within various cell types, leading to nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, skin, eye, renal, cerebrovascular, and cardiac manifestations, which can reduce quality of life and life expectancy1,2. Current treatment strategies for FD in adults target the underlying pathology of the disease (with enzyme replacement therapy [ERT] or pharmacological chaperone therapy), combined with adjunctive therapies to manage symptoms3.

In FD, neuropathic pain is among the first clinical symptoms (together with gastrointestinal symptoms) that interfere with well-being and daily activities. Neuropathic pain usually arises in childhood4 and is the most common (62% of male and 41% of female patients) and disabling clinical manifestation of FD5,6,7. It impacts patients’ QoL and is not adequately managed by conventional pain medications or FD-specific therapies2,8,9. Thus, it is an important target for new treatment options. Subsequently, progressive damage to vital organ systems occurs over several decades, resulting in end-stage renal disease and/or life-threatening cardiovascular or cerebrovascular complications, causing substantial morbidity and premature death10. Despite ERT, neuropathic pain and progressive eGFR loss are reported in adults with FD11. Hence, there is a need for more effective therapeutic approaches.

While neuropathic pain is typically assessed using a validated pain scale completed by the patient, kidney function is commonly assessed by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). In patients with FD, and, depending on the level of kidney involvement, major therapeutic goals are to stabilize or reduce eGFR decline and avoid or delay the progression of chronic kidney disease to end-stage renal disease3.

Lucerastat is an oral glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor under investigation as a substrate reduction therapy (SRT) for the treatment of FD, the principle of which is to reduce Gb3 synthesis and consequently prevent further Gb3 accumulation12,13,14. Results of preclinical and clinical studies showed that lucerastat reduced Gb3 levels in kidneys and dorsal root ganglions of Fabry mice15 and in cultured fibroblasts from individuals with FD regardless of the GLA variant13, was effective for reducing plasma Gb3 in patients with FD on top of ERT12, and was well tolerated in healthy individuals14,16, individuals with renal impairment (including participants with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2)17, and individuals with FD12. With its oral administration, GLA variant-independent mechanism of action, and tolerability in renally impaired individuals, lucerastat has the potential to address some of the unmet needs associated with current therapy options.

MODIFY (NCT03425539), conducted from 8 May 2018 to 2 September 2021, was a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 study to determine the clinical efficacy of lucerastat monotherapy and evaluate its safety and tolerability in adults with FD; its open-label extension (OLE) study (NCT03737214), aims at determining the long-term safety and tolerability of lucerastat for up to 72 months18. The primary objective of MODIFY was to evaluate the effect of lucerastat on neuropathic pain. Secondary objectives included the effects of lucerastat on gastrointestinal symptoms, FD biomarkers, and safety and tolerability. Other prespecified efficacy endpoints included the effect of lucerastat on renal function and cardiac parameters. Here, we report the results from MODIFY and an unplanned interim analysis of the combined MODIFY/OLE when ongoing OLE participants had received lucerastat for ≥12 months.

Results

Patient population and baseline characteristics

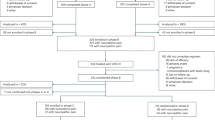

Overall, 182 participants were screened, and 118 were randomized at 49 sites in 14 countries covering North America, Europe, and Australia (Fig. 1). The most common reason for pre-randomization exclusion was not meeting the inclusion criterion of moderate-to-severe neuropathic pain (24% of screened participants). Of the 118 randomized participants, 117 received at least one dose of study treatment, and 109 (92%) completed the 6-month MODIFY study treatment; 107 (91%) enrolled in the OLE, and 78 (67%) were ongoing at the 18-month interim analysis (Fig. 1). Participants’ characteristics were similar across treatment groups at randomization (Table 1). Around half of the participants were male (47%), and the mean (standard deviation [SD]) age at screening was 39.3 (14.1) years (Table 1). More than 80% of participants had the classic FD subtype, and 80% of the 98 participants tested had pathogenic variants non-amenable to treatment with migalastat; genotypes are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

At baseline, 45 (38%) participants switched from ERT, while 72 (62%) were ERT-naïve. Forty (34%) participants were treated with an ACE inhibitor or ARB, and 92 (79%) were treated with at least one pain medication (Table 1).

Demographic and baseline characteristics for participants with versus without renal impairment are shown in Supplemental Table S2.

The eDiary was adequately completed by 112/118 participants (95%). Overall, the mean (SD) baseline modified Brief Pain Inventory short form (BPI-SF3) score was 6.21 (1.49) (Table 1). Supplemental Table S3 provides more details on neuropathic pain characteristics at baseline.

Three participants on lucerastat (4%) and two on placebo (5%) (re-)initiated ERT during MODIFY (all agalsidase beta).

At the interim analysis, the median (Q1, Q3) duration of lucerastat exposure was 23.0 (17.1, 32.8) months for the 114 participants who received at least one dose of lucerastat (in MODIFY and/or OLE), representing 230.4 patient-years of exposure. For most (n = 93) of these participants, pre-randomization eGFR data were available (Supplemental Table S4).

MODIFY: primary and secondary endpoints

Neuropathic pain (primary endpoint), assessed by the modified BPI-SF3 score, was reduced from baseline to Month-6 in both treatment groups (lucerastat and placebo), with a numerically smaller, albeit not statistically significant, reduction with lucerastat versus placebo (least squares mean [LSM] difference −0.42 [95% confidence interval (CI) −1.23, 0.40]) (Fig. 2A).

Change from baseline over time in MODIFY in A neuropathic pain monthly score, B plasma Gb3, C abdominal pain monthly score, and D number of days with diarrhea. Gb3 globotriaosylceramide. The red dotted line represents participants receiving placebo during MODIFY; the solid blue line represents participants receiving lucerastat during MODIFY. The graphs (A–D) include all participants who received at least one dose of study treatment and (for graphs C and D) experienced moderate-to-severe abdominal pain or diarrhea during the 4 weeks prior to randomization. Data are shown as least squares mean (95% CI) change from baseline (A, C, D) or mean (± SE) change from baseline (B). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

On secondary endpoints, there was a reduction in plasma Gb3 in the lucerastat group (LSM of the change from baseline to Month-6 −672.68 ng/mL) compared with an increase in the placebo group (200.84 ng/mL), and a relevant treatment effect was detected (LSM treatment difference in favor of lucerastat versus placebo: −873.53 ng/mL; 95% CI: −1097.53, −649.53; p < 0.0001) (Figs. 2B and 3A). However, this difference cannot be considered statistically significant due to the hierarchical testing strategy. Lucerastat did not reduce abdominal pain (LSM difference 0.31 [95% CI –0.53, 1.16], p = 0.47; Fig. 2C) nor diarrhea (win ratio 1.00 [95% CI 0.57, 1.89], p = 0.90; Fig. 2D) versus placebo.

Change from baseline over time in MODIFY and its OLE in A plasma Gb3, B plasma lysoGb3, and C urine Gb3. Gb3 globotriaosylceramide, lysoGb3 globotriaosylsphingosine, OLE open-label extension. The red dotted line represents participants receiving placebo during MODIFY; the solid blue line represents participants receiving lucerastat during MODIFY and the OLE; the dotted blue line represents participants receiving lucerastat in the OLE. Data are shown as mean (± SE) change from baseline. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

MODIFY: other prespecified efficacy endpoints and post hoc analyses in subgroups

Renal function endpoints

The LSM of the eGFR slope (mL/min/1.73 m2 per month) was +0.26 in the lucerastat group versus +0.08 in the placebo group, corresponding to a change of approximately +3.12 versus +0.96 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year, respectively. The LSM treatment difference was not statistically significant (LSM = 0.19; 95% CI: –0.40, 0.78; p = 0.5313).

The UACR change from baseline was not normally distributed. Thus, an analysis of log-transformed data was performed. This yielded a LSM percentage change difference of +16.2% (95% CI: −23.9, 77.3; p = 0.4875), indicating no difference between treatment groups.

In a post-hoc analysis by sex, no difference in mean eGFR change from baseline between treatment groups was observed, with a slight increase in males and no significant change from baseline in female participants (Supplemental Fig. S1).

In a post-hoc subgroup analysis of participants with impaired renal function at baseline (i.e., screening eGFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2; n = 40), change from baseline to Month-6 in mean eGFR was +3.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the lucerastat group (n = 27), whereas in the placebo group (n = 13) the change was –1.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Supplemental Fig. S2A). There was no observation of note in participants without renal impairment at baseline (n = 77) (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Cardiac endpoints

Values of the echocardiography-based endpoints remained stable from baseline to Month-6.

Rescue pain therapy

The median number of days on significant rescue pain therapy was 0 in both lucerastat and placebo treatment groups, while the mean number of days on significant rescue pain therapy from baseline to Month-6 was numerically smaller with lucerastat than placebo (4.9 days versus 9.5 days, respectively) (Supplemental Table S5).

Fabry disease biomarkers

Plasma lysoGb3 remained stable in the lucerastat group, with an LSM percentage change from baseline to Month-6 of 1.05% (Fig. 3B). In comparison, the LSM percentage change was 26.82% in the placebo group (LSM difference versus placebo = −20.32%, 95% CI: −34.24, −3.45). This translates into differences between lucerastat and placebo for plasma lysoGb3 (LSM difference at Month-6 −5.88 ng/mL [95% CI −11.62, −0.13]). Urinary Gb3 had an LSM percentage change from baseline to Month-6 of −44.64% in the lucerastat group, while the change for placebo was +47.80% (Fig. 3C). This translates into LSM differences between lucerastat and placebo at 6 months of 8.32 µmol Gb3/mol creatinine [95% CI −11.60, −5.04]. Both differences were nominally statistically significant.

In post-hoc analyses by baseline ERT status, the effect of lucerastat versus placebo on plasma Gb3 observed in the overall population was maintained in both ERT-naïve participants and those switching from ERT; a similar effect was observed on urine Gb3 regardless of baseline ERT status (Supplemental Fig. S3A and S3C). An increase in plasma lysoGb3 was observed in patients switching from ERT at baseline to placebo, but not in patients switching to lucerastat at baseline; no between-group difference was observed in patients who were ERT-naïve at baseline (Supplemental Fig. S3B). The results for plasma Gb3, plasma lysoGb3, and urine Gb3 split by ERT status at baseline and sex are shown in Supplemental Fig. S4A–F.

OPEN-LABEL EXTENSION: interim analysis

The effect of lucerastat observed on plasma Gb3 during MODIFY was maintained over time during the OLE. Patients who switched from placebo to lucerastat at Month-6 responded similarly to those randomized to lucerastat in MODIFY (Fig. 3A–C). The results for plasma Gb3, plasma lysoGb3, and urine Gb3 split by ERT status at baseline and sex are shown in Supplemental Fig. S4A–F.

In the overall population (n = 93), the LSM annualized eGFR slope pre-randomization was −3.50 (95% CI −5.04, −1.96) mL/min/1.73 m2 and −1.48 (95% CI −2.64, −0.33) mL/min/1.73 m2 post-randomization (Fig. 4). Similar patterns of a lesser decline after randomization were observed by sex, by amenability to migalastat, in ERT-naïve participants, in participants with renal impairment, and in participants who were classified as deteriorating/fast deteriorating (decline of more than 3 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year) pre-randomization: in participants with renal impairment, the LSM annualized eGFR slope was −6.18 [95% CI −8.68, −3.69] pre-randomization and −1.88 [95% CI –4.03, 0.26] mL/min/1.73 m2) post-randomization, while in participants who were deteriorating/fast deteriorating with an eGFR slope of −9.77 [95% CI −15.42, −4.12] mL/min/1.73 m2 pre-randomization, an eGFR slope of −1.16 [95% CI −6.76, 4.44] mL/min/1.73 m2 was observed post-randomization on lucerastat (Fig. 4). Of note, pre- and post-randomization eGFR slopes were similar for participants without renal impairment who were on ACE inhibitors/ARB at baseline or who switched from ERT (Fig. 4). Overall, 50 participants (54%) had stable eGFR slope (defined as a decline of less than 3 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) prior to randomization, and 70 (75%) while on lucerastat. Twenty-one participants (23%) were fast deteriorating (defined as a decline of at least 5 mL/min/1.73 m2/year) pre-randomization, only 10 (11%) while on lucerastat (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Changes from baseline in eGFR over time in MODIFY and OLE overall and split by sex, ERT status at baseline, and eGFR at baseline are shown in Supplemental Fig. S5A–D.

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, CI confidence interval, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, ERT enzyme replacement therapy, LS least squares. Baseline is the last non-missing value recorded up to and including the MODIFY randomization visit (for participants randomized to lucerastat in MODIFY) or the OLE enrolment visit (for participants randomized to placebo in MODIFY). Data are presented overall and by subgroup comparing lucerastat to historical data from the same participants. The estimation of the covariance matrix was primarily based on “unstructured” covariance structure. In case the mixed model did not converge, it was replaced by the “variance components” structure, followed by the “compound symmetry” structure. Data are shown as least squares mean (95% CI) change from baseline. Source data are provided in the figure.

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate. Renal impairment is defined as baseline eGFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2. The pre-randomization eGFR slope was calculated from serum creatinine measured within 2 years prior to randomization in MODIFY, available for 93 participants. The colors indicate the categories of stable (green; annualized eGFR slope >−3 mL/min/1.73 m2), deteriorating (yellow; ≥−5 and ≤−3 mL/min/1.73 m2), or fast deteriorating (pink/red; <−5 mL/min/1.73 m2). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Cardiac endpoints

In participants with normal left ventricular mass at baseline (n = 70), the average LVMi was maintained in a normal range over the duration of the OLE. In participants with left ventricular hypertrophy (n = 26), no further increases in LVMi were noted during the trial (Supplemental Fig. S6).

Safety outcomes

In MODIFY, the prevalence of AEs was similar in the treatment groups (Table 3). The most commonly reported treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) with a higher frequency with lucerastat than placebo were nausea and diarrhea. TEAEs reported with a higher frequency with placebo than lucerastat were abdominal distension and decreased GFR. Headache and nasopharyngitis were reported by ≥10% of participants in both groups. AEs leading to the premature discontinuation of study treatment were reported in two participants in each group, including gastroenteritis (n = 1) and vomiting (n = 1) in the lucerastat group. In the placebo group, one participant discontinued due to abdominal distension, fatigue, muscle spasms, flushing, gastrointestinal pain, and headache, while another discontinued due to chest pain, pain, fatigue, palpitations, tachycardia, nausea, and tinnitus. SAEs were reported for five participants (6%) in the lucerastat group and one in the placebo group (3%). No SAEs were assessed as related to the study treatment or reported by more than one participant (Supplemental Table S6). No deaths were reported. Analyses of vital signs, physical examination findings, clinical laboratory measurements, and electrocardiographic results did not reveal any clinically relevant effect of lucerastat.

Table 4 shows an overview of AEs occurring or worsening during lucerastat treatment in MODIFY and OLE. The most commonly reported TEAEs were COVID-19, neuralgia, and headache. SAEs reported in more than one participant included atrial fibrillation, transient ischemic attack, and drug withdrawal syndrome (two participants each). There was no sign of inflation of SAEs over time and no pattern in SAEs was observed. There were no deaths and no serious TEAEs related to study treatment during MODIFY or OLE.

Discussion

MODIFY is the largest randomized trial performed in FD to date and included a broad spectrum of participants with FD, including male and female participants, classic and non-classic disease, and participants who were ERT-naïve or were previously on therapy. Compared with placebo, neuropathic pain, abdominal pain, and diarrhea were not reduced after 6 months on lucerastat. Lucerastat-treated participants had lower FD biomarkers (plasma Gb3, plasma lysoGb3, urine Gb3), with decreases maintained over time and when participants switched from ERT to lucerastat. Although the study was not designed to evaluate the impact of lucerastat on renal function (as the duration of the controlled trial was too short), our results, considering both MODIFY and its long-term extension, suggest a possible effect on renal function, especially in populations with higher medical needs, such as decreased renal function at baseline.

The effect of currently approved FD therapies on pain is unclear2,9,19,20,21 and several possible explanations exist for the lack of effect on neuropathic pain at Month-6. Neuropathic pain in FD is not fully understood, with conflicting findings over the role of Gb3 and its derivatives22,23. If Gb3 has a role in neuropathic pain, the inhibition of its synthesis by lucerastat, resulting in lower plasma and urine concentrations, may not have caused sufficient substrate reduction in the dorsal root ganglion in the 6-month treatment period, especially in the 83% of participants with the classic FD phenotype. Plasma lysoGb3 has been hypothesized to be important in Fabry pain22. In this context, the effect of lucerastat on plasma lysoGb3 levels seems less marked than the effect on Gb3 over the 6 months of MODIFY, but the effect may take longer to become apparent and further controlled studies are required. The pain-causing pathology in FD may not be reversible; alternatively, it may be easily reversible, as shown by the improvement in participants receiving placebo.

Although dedicated questionnaires for analyzing Fabry-associated pain have been developed, their suitability to measure therapeutic effects on such a subjective endpoint remains uncertain18,24. The modified BPI-SF3 was validated for use in FD18, and used for the first time in MODIFY to assess differences between placebo and investigative treatment. Notably, there was a larger-than-expected placebo response for neuropathic pain in the present study. Sample size calculations assumed an increased modified BPI-SF3 score in the placebo group (based on a previous study25), whereas the score decreased in both groups. This could be partially due to the Hawthorne effect, in which trial participants respond differently because they know they are being monitored26; alternatively, values gathered in the screening period may have been inflated. Most participants (79%) were taking pain medication at baseline and were permitted to continue the medication during the study. This could not be standardized across participants and, therefore, may have influenced the measurement of neuropathic pain.

Stability or reduction of loss of eGFR slope is a therapeutic goal of FD3. The MODIFY study and its long-term extension were not designed to evaluate the effect of lucerastat on renal function. Nevertheless, the observed data allows hypothecating a potential effect of lucerastat on renal function. During the 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled MODIFY trial, the observation of a potential reversal of eGFR decline in participants with impaired renal function at baseline is intriguing, despite no difference versus placebo in the overall population. The OLE, with a median exposure of 23 months, allows a more accurate evaluation of the eGFR slope post-baseline, and a fair comparison to the 2-year pretreatment eGFR slope in the 93 patients with pre- and post-baseline plasma creatinine values. The observed inflection of the eGFR slope post baseline in the overall population, and singularly in patients with impaired renal function at baseline or whose renal function is fast deteriorating, suggests a potential effect of lucerastat on renal function, which deserves further research.

The mechanism of action of lucerastat on eGFR is assumed to be primarily based on the reduction of lipid inclusions in the kidney cells. A pre-clinical study indicated that lucerastat treatment significantly reduced the storage of α-GalA substrates, including Gb3, in the kidneys of Fabry mouse models after 20 weeks15. In the previous clinical trial in patients with FD, the duration of lucerastat treatment was too short (12 weeks) to make any meaningful conclusion on the effect of lucerastat on renal function12.

In MODIFY, lucerastat reduced plasma Gb3 levels from baseline to Month-6 versus placebo, and data from the OLE showed that this effect was maintained. Phase 3 trials of approved FD therapies have shown significant reductions in plasma Gb3 (agalsidase alfa and agalsidase beta)19,20 and plasma lysoGb3 (migalastat)9. An approximately 20% reduction in Lyso-Gb3 was observed with lucerastat versus placebo in the overall population, mainly driven by an increase in participants randomized to placebo who stopped ERT at baseline, while it remains stable in participants who switched from ERT to Lucerastat. FD trials recruit different patient populations, with some including only male participants with classic FD20 and others having varying proportions of females and late-onset variants19,21. Biomarker levels differ by sex due to the residual enzyme activity in females1, and the assays are not standardized between studies, making it difficult to compare findings.

Lucerastat had no effect overall on LVMi in MODIFY and at the interim OLE analysis. Cardiac data were mainly collected for safety analysis, as the study was considered too short to evaluate changes conclusively over time, and only a few participants had cardiac hypertrophy at baseline. Importantly, there was no worsening of cardiac hypertrophy on lucerastat, as prior long-term studies have shown an increase in myocardial mass/wall thickness of patients with FD over time if untreated or treated late27,28.

MODIFY/OLE are not without limitations. Most participants were white, while FD is pan-ethnic. As lucerastat should prevent substrate accumulation, a longer double-blind treatment period may have yielded different results. The collection of eGFR data pre-randomization was not standardized. Moreover, the number of data points used to estimate historical eGFR pre-randomization was variable between participants, and there was no control group in the OLE.

To conclude, the results of the 6-month MODIFY study in adults with FD indicate no effect of lucerastat on neuropathic pain, abdominal pain, or diarrhea compared with placebo. Nevertheless, lucerastat reduced biomarkers of FD, and these reductions were maintained at the interim analysis of the OLE. The interim analysis, including participants who were treated with lucerastat for a median of 23 months, suggests a positive effect on renal function, although in the absence of a parallel control group, no conclusions can be made. Lucerastat was well tolerated during MODIFY and its OLE. These results are hypothesis-generating and warrant further investigation.

Methods

Study design

Protocols and materials for the studies were approved by Independent Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards (Supplemental Table S7). The studies were conducted in compliance with the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and with the laws and regulations of the countries in which they were performed. Participants provided written informed consent before entry into MODIFY and the OLE, and again at Months 24 and 48 of the OLE.

MODIFY was a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group Phase 3 study to assess the safety and efficacy of lucerastat oral monotherapy in adults with FD. The study was conducted in 49 hospitals in 14 countries in Europe, North America, and Australia. The study comprised a screening period (6–7 weeks) and a double-blind treatment period (6 months) followed by either a safety follow-up (1–3 months) or a multicenter, single-arm OLE study. In the ongoing OLE study, participants receive lucerastat for up to 72 months. Interim analysis of the OLE study was performed when all ongoing participants completed 12 months of open-label treatment, for a total of at least 12 months for those participants originally randomized to placebo and up to at least 18 months, depending on the treatment arm, for those participants originally randomized to lucerastat.

Substantial protocol amendments included a change from a dichotomous-responder based analysis of the primary endpoint to a continuous analysis (agreed with the FDA to overcome recruitment challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic)18, and extension of the OLE from 24 to 72 months in light of the favorable treatment effect on plasma Gb3 and safety profile. Furthermore, the statistical section of the OLE was revised to analyze OLE data in combination with that from MODIFY rather than analyzing OLE data separately.

As the OLE is an open-label, uncontrolled, single-arm extension study to determine the long-term safety and tolerability of oral lucerastat in adult participants with FD, an interim analysis was not prespecified in the OLE protocol. However, standard operating procedures do not preclude interim analysis of open-label uncontrolled long-term trials. Interim reporting is generally accepted and judged necessary by Independent Ethics Committees and Institutional Review Boards to reassess at regular intervals the benefit/risk of an investigational drug given long-term to patients and to publish the results if important signals are observed. Indeed, not performing this analysis might seem unfit in a long-term open-label study, which is positioned to identify the long-term safety, tolerability, and potential signs of prolongation of efficacy signals observed in a placebo-controlled study of a novel molecule. While the interim analysis results of the OLE reported here were added to the Investigator Brochure in February 2023, submitted, and approved by all Independent Ethics Committees and Institutional Review Boards, their dissemination through publication does not need Institutional Review Board review.

Protocols and statistical analysis plans for each study are available (see Supplementary Appendix). Of note, the statistical testing strategy was introduced in Global Protocol Version 4 as a result of FDA requests and advice. The order of the secondary endpoints in the statistical testing strategy (plasma Gb3, abdominal pain, stool consistency) is not identical to the order of the secondary endpoints defined in Global Protocol Version 1 (abdominal pain, stool consistency, plasma Gb3). The reason for testing plasma Gb3 before the GI symptom endpoints is that plasma Gb3 is assessed in the full population (mFAS), whilst the GI symptom endpoints are assessed only on a subset of participants with GI symptoms at baseline (mFAS-GIS).

Participants

Key inclusion criteria for MODIFY were previously described18. Eligible participants were ≥18 years old with a genetically confirmed FD diagnosis. Participants had to report moderate-to-severe neuropathic pain (defined as an average score of ≥4 on the 11-point numerical rating scale [NRS] Modified Brief Pain Inventory short form [BPI-SF3] over the 4 weeks prior to randomization) during the screening period. Eligible participants were either “naïve” (had never received ERT or had not received it for at least 6 months) or “ERT switch” (had been treated with ERT for at least 12 months and agreed to stop ERT at screening).

Participants with other diseases or conditions associated with pain components that could have confounded the assessment of neuropathic pain were excluded. Participants with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration 4 variable equation)29, with any major cardiovascular, kidney, or cerebrovascular medical conditions, or at risk of developing those conditions during the study, were ineligible for MODIFY; those who developed any major cardiovascular, kidney, or cerebrovascular medical conditions during MODIFY, or were at risk of developing them, were ineligible for the OLE study. After randomization in MODIFY, participants had to discontinue study treatment if eGFR was <15 mL/min/1.73 m2. Hence, participants with an eGFR >15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the end of MODIFY could still be eligible to enroll in the OLE. Participants taking angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) had to be on a stable dose for ≥4 weeks before the screening visit. During the trials, initiation or dose adjustments were permitted based on the investigator’s judgment.

Participants could only be reimbursed for expenses incurred in the context of their participation in the trials (e.g., reasonable travel expenses, hotel stay, and, if accepted under local law, loss of earnings).

Randomization and masking

Participants were randomized (2:1) to lucerastat or placebo. Randomization was stratified by sex and ERT status at screening (naïve or ERT switch), and treatment was allocated using a web-based interactive response technology system. Study treatment was provided as identical capsules of 250 mg lucerastat or placebo, and all treatment kits were packaged in the same way. Participants, investigators, site personnel, and sponsor personnel involved in the study conduct were unaware of study treatment allocation. In the event of a medical emergency, investigators were permitted to initiate the unmasking process; no unmasking events occurred in the MODIFY study.

Procedures

Lucerastat and placebo capsules were administered orally twice daily. The starting dose of 1000 mg was adjusted based on eGFR values as previously described17,18. Participants receiving placebo during MODIFY were switched to lucerastat at the beginning of the OLE. The dose was adjusted if a participant’s eGFR crossed boundary thresholds (Supplemental Table S8).

An Individual Pain Management Plan (IPMP) was provided to each participant by the investigator/delegate with customized instructions regarding the use of pain medications during the study. Use of adjuvant pain medication and non-opioid and opioid analgesics was allowed in both studies if medically required, as well as rescue medication in case of unbearable pain. In MODIFY, significant rescue pain therapy was defined as initiation or dose escalation of anti-epileptics, anti-depressants, or opioid analgesic drugs for neuropathic pain, as recorded in the eDiary. Participants were allowed to (re-)initiate and then continue ERT in MODIFY and/or in the OLE study if medically required due to significant FD progression.

Site visits in MODIFY were scheduled at Months 1, 3, 5, and 6 or end of treatment (EOT), with phone calls at Months 2 and 4. Participants who did not enter the OLE were followed up by phone call approximately 1 month after the last dose of study treatment; fertile male participants had a second call 3 months after the last dose of study treatment. In the OLE, visits were scheduled at Months 1, 2, 3, and then every 3 months until EOT, with alternate visits being phone calls. Key measurements and assessments in MODIFY have been previously described18 and are listed in Supplemental Table S9. All patient-reported outcome assessments, collected daily (MODIFY only) or during site visits (MODIFY and OLE), were recorded in an eDiary. The modified BPI-SF3, NRS-11 for abdominal pain, and Bristol Stool Scale (BSS) (see Supplemental Table S10) (which were recorded daily) were validated and agreed with the FDA18.

Plasma and urine samples for the analysis of the biomarkers plasma Gb3, plasma globotriaosylsphingosine (lysoGb3), and urine Gb3 were collected pre-dose at all scheduled visits in MODIFY and the OLE (Supplemental Table S9). Laboratory measurements in MODIFY and its OLE were analyzed centrally using validated liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry assays. Urine Gb3 was normalized by dividing by the independently determined creatinine concentration. Additionally, participants’ serum creatinine values measured within 2 years prior to randomization in MODIFY (e.g., 2 values per year, 6 months apart from each other, irrespective of why serum creatinine was measured) were collected. Serum creatinine values were used to calculate the eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation29. Echocardiography measurements in both studies were assessed through blinded, centralized evaluation.

Safety data (including AEs and serious AEs [SAEs]) were collected throughout the trial from screening in MODIFY up to 30 days after EOT (in MODIFY or OLE, as applicable).

All data were stored in a database.

Outcomes

Supplemental Table S11 lists all study endpoints for MODIFY and its OLE. In MODIFY, the primary endpoint was the change from baseline to Month-6 in neuropathic pain (measured using the modified BPI-SF3 score of “neuropathic pain at its worst in the last 24 h”, range 0–10)18. The secondary endpoints were change from baseline to Month-6 in plasma Gb3, abdominal pain (measured using the NRS-11 score of “abdominal pain at its worst in the last 24 h”, range 0–10), and number of days with diarrhea (measured using the BSS)18. Other prespecified efficacy endpoints included change from baseline to Month-6 in plasma lysoGb3, urine Gb3, and eGFR slope, and use of rescue pain therapy from baseline to Month-618.

In the OLE, the main efficacy endpoints were the annualized eGFR slope and changes from MODIFY baseline in plasma Gb3, plasma lysoGb3, urine Gb3, and left ventricular mass index (LVMi).

AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 24.0).

Statistical analysis

Assuming a within-group standard deviation of 3 points, a two-sided type I error of 5%, and a 2:1 randomization ratio, a sample size of 99 participants would provide 87% power to detect a treatment difference of 2 points between lucerastat and placebo for the primary endpoint of MODIFY. These assumptions are based on data from patients on ERT and placebo in previous studies25,30.

A fixed-sequence statistical testing strategy was pre-specified to test the four null hypotheses of MODIFY, starting with the primary endpoint and continuing with the secondary endpoints (in the order of plasma Gb3, abdominal pain, and days with diarrhea). If a hypothesis in the sequence was not rejected, p-values for the subsequent hypotheses were to be considered exploratory.

In MODIFY, efficacy analyses included all randomized participants who took at least one dose of study treatment. Secondary gastrointestinal endpoints were analyzed on the subset of participants experiencing moderate-to-severe abdominal pain and/or diarrhea during the 4 weeks before randomization. Safety data were analyzed in all participants who received at least one dose of study treatment.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with a factor for treatment group and adjusting for the baseline value and the two stratification factors was used to analyze the primary endpoint and secondary endpoints related to plasma Gb3 and abdominal pain. Missing data were imputed by applying multiple imputation approaches, assuming data are missing at random in the placebo arm but missing not at random in the lucerastat arm (primary endpoint and abdominal pain) or missing at random in both arms (plasma Gb3). The secondary endpoint related to diarrhea was analyzed using rank ANCOVA and win ratio. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of inferences from the main analyses to deviations from its underlying modeling assumptions regarding missing data.

Subgroup analyses were prespecified for the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints for, among others, subgroups based on sex, ERT-treatment status (naïve versus switch), and baseline eGFR. The latter subgroup was initially defined as eGFR <60 versus ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2, but due to the low number of participants in the former category (Table 1), this was redefined as eGFR <90 versus ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2. Subgroup analyses were also performed for other efficacy endpoints, but these were not prespecified and should be interpreted as exploratory analyses. The limitations of post-hoc subgroup analyses are acknowledged31,32.

An unplanned Month-18 interim analysis of the combined MODIFY/OLE was conducted. Pre-randomization and lucerastat (excluding placebo data from MODIFY) annualized eGFR slopes were estimated using linear mixed models, including time (in years) as a fixed effect and a random intercept and random slope effect. Participants with at least two eGFR values to derive a pre-randomization and lucerastat annualized eGFR slope were included in these analyses. Participants were classified as stable (annualized eGFR slope decline of less than 3 mL/min/1.73 m2), deteriorating (annualized eGFR slope decline between 3 and 5 mL/min/1.73 m2), or fast deteriorating (annualized eGFR slope decline of more than 5 mL/min/1.73 m2) based on their pre-randomization and lucerastat eGFR slope3. Annualized eGFR slopes within subgroups of interest were derived by adding the respective subgroup as a main fixed effect as well as its interaction with time to the linear mixed model described above. All available lucerastat eGFR data (also beyond Month 18) in MODIFY/OLE, including early post-baseline values, were used for the eGFR slope analyses, which assumes no acute hemodynamic effect of lucerastat. Annualized eGFR slopes were reported as least squares mean (LSM).

Descriptive analyses of changes from baseline up to Month 18 in biomarkers, echocardiography, and pain-related variables were performed overall and within subgroups of interest.

For participants who (re-)started ERT during MODIFY or OLE, a treatment policy strategy was applied, i.e., all data after (re-)starting ERT were included in the analyses.

SAS® software version 9.4 was used for statistical analysis and reporting of clinical data. An Independent Data-Monitoring Committee (Supplemental Table S12) was established in MODIFY to monitor safety and efficacy.

MODIFY and its OLE are listed on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03425539 Date of registration: 07-Feb-2018, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03425539; NCT03737214 Date of registration: 09-Nov-2018, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03737214) and EudraCT (2017-003369-85 Date of registration [first country, GB]: 16-Apr-2018, https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2017-003369-85/GB/; 2018-002210-12 Date of registration [first country, GB]: 23-Oct-2018, https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2018-002210-12/GB/). Of note, the trials are registered in EudraCT by the competent authority, i.e., these dates do not refer to the date of submission, but to the date posted on the website. MODIFY was registered prior to patient enrollment, and patient enrollment is complete.

Patient and public involvement

A patient survey was conducted via patient organizations (Fabry International Network, Fabry Support & Information Group, National Fabry Disease Foundation) to better understand symptoms of FD and their impact on individuals’ quality of life, as well as to understand perceptions of existing FD treatments. The results were used to inform the design of the Phase 3 study2. The primary and secondary patient-reported outcomes of the present study (neuropathic pain, abdominal pain, and diarrhea) were developed in collaboration with individuals with FD via a concept elicitation and cognitive debrief study18. A plain-language summary is planned to aid dissemination.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

In addition to Idorsia’s existing clinical trial disclosure activities, the company is committed to implementing the Principles for Responsible Clinical Trial Data Sharing jointly issued by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available with this publication (Supplemental Material Appendix A─D). Source data of results included in this article are provided with this paper. After research completion, data will be shared for replication and verification processes with qualified researchers that request access to trial data by submitting a research proposal to the trial sponsor, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. For more information and to submit research proposals, contact clinical-trials-disclosure@idorsia.com.

References

Germain, D. P. Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 5, 30 (2010).

Morand, O. et al. Symptoms and quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: results from an international patient survey. Adv. Ther. 36, 2866–2880 (2019).

Wanner, C. et al. European expert consensus statement on therapeutic goals in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 124, 189–203 (2018).

Hopkin, R. J. et al. Characterization of Fabry disease in 352 pediatric patients in the Fabry registry. Pediatr. Res. 64, 550–555 (2008).

Eng, C. M. et al. Fabry disease: baseline medical characteristics of a cohort of 1765 males and females in the Fabry registry. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30, 184–192 (2007).

Gold, K. F. et al. Quality of life of patients with Fabry disease. Qual. Life Res. 11, 317–327 (2002).

Hoffmann, B. et al. Effects of enzyme replacement therapy on pain and health related quality of life in patients with Fabry disease: data from FOS (Fabry Outcome Survey). J. Med. Genet. 42, 247–252 (2005).

Finnerup, N. B. et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 14, 162–173 (2015).

Germain, D. P. et al. Treatment of Fabry’s disease with the pharmacologic chaperone migalastat. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 545–555 (2016).

Germain, D. P. et al. Consensus recommendations for diagnosis, management and treatment of Fabry disease in paediatric patients. Clin. Genet. 96, 107–117 (2019).

Warnock, D. G. et al. Renal outcomes of agalsidase beta treatment for Fabry disease: role of proteinuria and timing of treatment initiation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, 1042–1049 (2012).

Guérard, N. et al. Lucerastat, an iminosugar for substrate reduction therapy: tolerability, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics in patients with Fabry disease on enzyme replacement. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 103, 703–711 (2018).

Welford, R. W. D. et al. Glucosylceramide synthase inhibition with lucerastat lowers globotriaosylceramide and lysosome staining in cultured fibroblasts from Fabry patients with different mutation types. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 3392–3403 (2018).

Guérard, N., Morand, O. & Dingemanse, J. Lucerastat, an iminosugar with potential as substrate reduction therapy for glycolipid storage disorders: safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 12, 9 (2017).

Welford, R. W. D. et al. Lucerastat, an iminosugar for substrate reduction therapy in Fabry disease: preclinical evidence. Mol. Genet. Metab. 120, S139–S140 (2017).

Mueller, M. S. et al. The effect of the glucosylceramide synthase inhibitor lucerastat on cardiac repolarization: results from a thorough QT study in healthy subjects. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 15, 303 (2020).

Guérard, N., Zwingelstein, C. & Dingemanse, J. Lucerastat, an iminosugar for substrate reduction therapy: pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and safety in subjects with mild, moderate, and severe renal function impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 1425–1431 (2017).

Wanner, C. et al. Understanding and modifying Fabry disease: rationale and design of a pivotal Phase 3 study and results from a patient-reported outcome validation study. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 31, 100862 (2022).

Eng, C. M. et al. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A replacement therapy in Fabry’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 9–16 (2001).

Schiffmann, R. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285, 2743–2749 (2001).

Hughes, D. A. et al. Oral pharmacological chaperone migalastat compared with enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: 18-month results from the randomised phase III ATTRACT study. J. Med. Genet. 54, 288–296 (2017).

Choi, L. et al. The Fabry disease-associated lipid Lyso-Gb3 enhances voltage-gated calcium currents in sensory neurons and causes pain. Neurosci. Lett. 594, 163–168 (2015).

Jabbarzadeh-Tabrizi, S. et al. Assessing the role of glycosphingolipids in the phenotype severity of Fabry disease mouse model. J. Lipid Res. 61, 1410–1423 (2020).

Müntze, J. et al. Patient reported quality of life and medication adherence in Fabry disease patients treated with migalastat: a prospective, multicenter study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 138, 106981 (2023).

Weidemann, F. et al. Patients with Fabry disease after enzyme replacement therapy dose reduction versus treatment switch. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 837–849 (2014).

McCambridge, J., Witton, J. & Elbourne, D. R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 267–277 (2014).

Germain, D. P. et al. Analysis of left ventricular mass in untreated men and in men treated with agalsidase-β: data from the Fabry registry. Genet. Med. 15, 958–965 (2013).

Parini, R. et al. Analysis of renal and cardiac outcomes in male participants in the Fabry outcome survey starting agalsidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy before and after 18 years of age. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 14, 2149–2158 (2020).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612 (2009).

Hoffmann, B. et al. Nature and prevalence of pain in Fabry disease and its response to enzyme replacement therapy–a retrospective analysis from the Fabry Outcome Survey. Clin. J. Pain. 23, 535–542 (2007).

Lagakos, S. W. The challenge of subgroup analyses–reporting without distorting. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1667–1669 (2006).

Wallach, J. D. et al. Evaluation of evidence of statistical support and corroboration of subgroup claims in randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 177, 554–560 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation, and funded the study and medical writing support. All authors were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Medical writing support was provided by Anne Sayers and Carlotta Foletti (Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd) and Melanie Gatt (an independent medical writer) in accordance with Good Publications Practice 2022 and was funded by Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. We thank the patients for their participation and the investigators for their involvement in participant care and contribution to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.N.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. O.G.-A.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. J.B.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. D.P.G.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. P.G.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. A.J.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. V.K.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. K.N.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. C.R.G.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. R.S.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, and writing–review and editing. M.T.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. A.T.-S.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. E.W.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. R.W.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. M.W.: Contributed to investigation and writing–review and editing. M.C.: Contributed to conceptualization and writing–review and editing. A.F.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. L.T.: Contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. M.M.: Contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. M.V.: Contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. C.W.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. D.H.: Contributed to conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.N.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; consulting fees from Amicus, Chiesi, Greenovation, Idorsia, Sanofi-Genzyme, Takeda; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Amicus, Chiesi, Greenovation, Idorsia, Sanofi-Genzyme, Takeda; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Amicus, Chiesi, Greenovation, Idorsia, Sanofi-Genzyme, Takeda. O.G.-A.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; grant support from Idorsia, Sanofi, Protalix, Chiesi, Sangamo, 4DMT for clinical research trials; grant support from Sanofi and Takeda for other investigator-initiated studies; has/will receive(d) consulting fees from Sanofi, Chiesi, Takeda, Uniqure; payment or honoraria for speaker bureaus for Sanofi and Takeda; participation on an advisory board on Fabry disease for Chiesi and Sanofi. J.B.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; research support for clinical trial from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals; research support from AVROBIO, BioMarin Pharmaceutical, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Pfizer, Protalix BioTherapeutics, Sangamo Therapeutics, Sanofi, Takeda, Travere Therapeutics; consulting fees from Chiesi USA and Takeda for advisory boards; speaker honorarium from Fabry Support and Information Group. D.P.G.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; consulting fees from Chiesi, Idorsia, Sanofi, and Takeda; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Chiesi, Sanofi, and Takeda. P.G.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments. A.J.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; research grants from Takeda and Amicus; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Amicus, Chiesi, Takeda, and Sanofi; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Amicus and Chiesi. V.K.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; payment for expert testimony from Sanofi; participation on a Pompe disease advisory board for Sanofi; PI of trials for Protalix and Idorsia. K.N.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; research/clinical trial funding to institution from Sanofi, Takeda, Amicus and Idorsia; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Takeda, Sanofi and Amicus; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Takeda, Sanofi and Amicus. C.R.G.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments. R.S.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments. M.T.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments. A.T.-S.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments. E.W.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; grants or contracts from Sanofi, Idorsia, Chiesi, Protalix, Walking Fish Therapeutics, Spark Therapeutics; consulting fees from Sanofi, Amicus, Chiesi, Protalix, Walking Fish Therapeutics, Spark Therapeutics; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Sanofi, Chiesi, and Natera; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Sanofi, Chiesi, and Protalix. R.W.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employed by Idorsia (the study funder) during the planning and execution of the study; owns stock in Idorsia. M.W.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; contract for research from Chiesi; grants from Takeda, Sanofi and Amicus; IP for Fabry gene therapy and Fabry cardiac biomarkers; consulting fees from Takeda; honoraria for CME presentations from Takeda, Sanofi and Sumitomo; payment for expert testimony from Takeda and Amicus; support for travel expenses from Amicus; participation on advisory boards for Sanofi and Amicus; Chair of the Scientific Committee for the CFDI Registry; Member of the Fabry Outcome Survey Steering Committee for Takeda; Member of the Scientific Committee for the Canadian Symposium on Lysosomal Diseases; Member of the North American Advisory Board for Sanofi; Member of the Scientific Committee for the Fabry Update Meeting. M.C.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd; shareholder of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. A.F.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd; shareholder of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. L.T.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals (Sponsor) at the time of data generation, statistical evaluation, and data interpretation; shareholder of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. M.M.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd; owns stock. M.V.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd; shareholder of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. C.W.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; grant(s) from Boehringer Ingelheim and Sanofi; consultancy fees from Amgen, Amicus, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vifor Pharma, Chiesi, Chugai, Fresenius Medical Care, GSK, Idorsia, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi. D.H.: Medical writing support for the manuscript as declared in the Acknowledgments; consultancy fees for advisory boards from Idorsia, Amicus, Sanofi, Takeda, Chiesi, Freeline, Sangamo; honoraria for speaking from Idorsia, Amicus, Sanofi, Takeda, Chiesi, Freeline, Sangamo; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Amicus, Sanofi, Freeline, Chiesi.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mevlut Dinçer, Ting-Rong Hsu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd at the time of the study: Richard W. D. Welford, Luba Trokan, Markus S. Mueller, Markus Vogler.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nordbeck, P., Goker-Alpan, O., Bernat, J.A. et al. Lucerastat, an oral therapy for Fabry disease: results from a pivotal randomized phase 3 study and its open-label extension. Nat Commun 17, 1534 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68256-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68256-5