Abstract

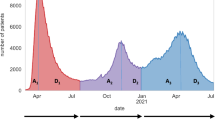

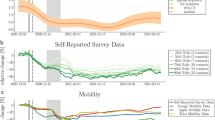

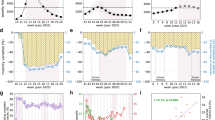

Accurately capturing time-varying human behavior remains a major challenge for real-time epidemic modeling and response. During the COVID-19 pandemic, synthetic contact matrices derived from mobility and behavioral data emerged as a scalable alternative to empirical contact surveys, yet their comparative performance remained unclear. Here, we systematically evaluate synthetic and empirical age-stratified contact matrices in France from March 2020 to May 2022, comparing contact patterns and their ability to reproduce observed epidemic dynamics. While both sources captured similar temporal trends in contacts, empirical matrices recorded 3.4 times more contacts for individuals under 19 than synthetic matrices during school-open periods. The model parameterized with synthetic matrices provided the best fit to hospital admissions and best captured hospitalization patterns for adolescents, adults, and seniors, whereas deviations remained for children across both models. Neither matrix allowed models to fully reproduce serological trends in children, highlighting the challenges both approaches face in capturing their disease-relevant contacts. The weekly update of synthetic matrices enabled smoother reconstructions of hospitalization trends during transitional phases, while empirical matrices required strong assumptions between survey waves. These findings support synthetic matrices as a reliable, flexible, cost-effective operational tool for real-time epidemic modeling, and highlight the need for routine collection of age-stratified mobility data to improve pandemic response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Mobility-driven synthetic contact matrices and SocialCov contact matrices are available at https://github.com/EPIcx-lab/COVID-19/tree/master/mobility_driven_synthetic_contact_matrices. All other data used in the analyses are available at the references cited in the Methods: pre-pandemic contact data12, Google mobility data31, CoviPrev behavioral survey data41, Normalcy Index66, Stringency Index67, French population data70, vaccine uptake71, hospital admission data79, seroprevalence data78.

Code availability

Code of the transmission model is publicly available at https://github.com/EPIcx-lab/COVID-19/tree/master/mobility_driven_synthetic_contact_matrices.

References

Becker, A. D. et al. Development and dissemination of infectious disease dynamic transmission models during the COVID-19 pandemic: what can we learn from other pathogens and how can we move forward? Lancet Digit. Health 3, e41–e50 (2021).

Jit, M. et al. Reflections on epidemiological modeling to inform policy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Western Europe, 2020–23. Health Aff. 42, 1630–1636 (2023).

Funk, S. et al. Nine challenges in incorporating the dynamics of behaviour in infectious diseases models. Epidemics 10, 21–25 (2015).

Bedson, J. et al. A review and agenda for integrated disease models including social and behavioural factors. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 834–846 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science 368, 1481–1486 (2020).

Jarvis, C. I. et al. Quantifying the impact of physical distance measures on the transmission of COVID-19 in the UK. BMC Med. 18, 124 (2020).

Lucchini, L. et al. Living in a pandemic: changes in mobility routines, social activity and adherence to COVID-19 protective measures. Sci. Rep. 11, 24452 (2021).

Wallinga, J., Teunis, P. & Kretzschmar, M. Using data on social contacts to estimate age-specific transmission parameters for respiratory-spread infectious agents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 164, 936–944 (2006).

Mossong, J. et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 5, e74 (2008).

Hoang, T. et al. A systematic review of social contact surveys to inform transmission models of close-contact infections. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass 30, 723–736 (2019).

Mousa, A. et al. Social contact patterns and implications for infectious disease transmission - a systematic review and meta-analysis of contact surveys. eLife 10, e70294 (2021).

Béraud, G. et al. The French connection: the first large population-based contact survey in France relevant for the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS ONE 10, e0133203 (2015).

Prem, K., Cook, A. R. & Jit, M. Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005697 (2017).

Prem, K. et al. Projecting contact matrices in 177 geographical regions: an update and comparison with empirical data for the COVID-19 era. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009098 (2021).

Arregui, S., Aleta, A., Sanz, J. & Moreno, Y. Projecting social contact matrices to different demographic structures. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006638 (2018).

Prem, K. et al. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 5, e261–e270 (2020).

Davies, N. G. et al. Effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 cases, deaths, and demand for hospital services in the UK: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 5, e375–e385 (2020).

Di Domenico, L., Pullano, G., Sabbatini, C. E., Boëlle, P.-Y. & Colizza, V. Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 epidemic in Île-de-France and possible exit strategies. BMC Med 18, 240 (2020).

Munday, J. D., Abbott, S., Meakin, S. & Funk, S. Evaluating the use of social contact data to produce age-specific short-term forecasts of SARS-CoV-2 incidence in England. PLOS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011453 (2023).

Hauser, A. et al. Estimation of SARS-CoV-2 mortality during the early stages of an epidemic: a modeling study in Hubei, China, and six regions in Europe. PLOS Med 17, e1003189 (2020).

Knock, E. S. et al. Key epidemiological drivers and impact of interventions in the 2020 SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in England. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabg4262 (2021).

Marziano, V. et al. Estimating SARS-CoV-2 infections and associated changes in COVID-19 severity and fatality. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 17, e13181 (2023).

Verelst, F. et al. SOCRATES-CoMix: a platform for timely and open-source contact mixing data during and in between COVID-19 surges and interventions in over 20 European countries. BMC Med. 19, 254 (2021).

Munday, J. D. et al. Estimating the impact of reopening schools on the reproduction number of SARS-CoV-2 in England, using weekly contact survey data. BMC Med 19, 233 (2021).

Gimma, A. et al. Changes in social contacts in England during the COVID-19 pandemic between March 2020 and March 2021 as measured by the CoMix survey: a repeated cross-sectional study. PLOS Med. 19, e1003907 (2022).

Coletti, P. et al. CoMix: comparing mixing patterns in the Belgian population during and after lockdown. Sci. Rep. 10, 21885 (2020).

Backer, J. A. et al. Dynamics of non-household contacts during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 in the Netherlands. Sci. Rep. Sci. Rep. 13, 5166 (2023).

Veneti, L. et al. Social contact patterns during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Norway: insights from a panel study, April to September 2020. BMC Public Health 24, 1438 (2024).

Bosetti, P. et al. Lockdown impact on age-specific contact patterns and behaviours, France, April 2020. Eurosurveillance 26, 2001636 (2021).

Soussand, F. et al. Evolution of social contacts patterns in France over the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: results from the SocialCov survey. BMC Infect. Dis. 25, 224 (2025).

Google. COVID-19 Community Mobility Report. COVID-19 Community Mobility Report https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility?hl=en.

Cot, C., Cacciapaglia, G. & Sannino, F. Mining Google and Apple mobility data: temporal anatomy for COVID-19 social distancing. Sci. Rep. 11, 4150 (2021).

Pepe, E. et al. COVID-19 outbreak response, a dataset to assess mobility changes in Italy following national lockdown. Sci. Data 7, 230 (2020).

Besley, T. & Dray, S. Pandemic responsiveness: evidence from social distancing and lockdown policy during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 17, e0267611 (2022).

Oliver, N. et al. Mobile phone data for informing public health actions across the COVID-19 pandemic life cycle. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0764 (2020).

Pullano, G. et al. Underdetection of cases of COVID-19 in France threatens epidemic control. Nature 590, 134–139 (2021).

Di Domenico, L., Goldberg, Y. & Colizza, V. Planning and adjusting the COVID-19 booster vaccination campaign to reduce disease burden. Infect. Dis. Model. 10, 150–162 (2025).

Di Domenico, L., Pullano, G., Sabbatini, C. E., Boëlle, P.-Y. & Colizza, V. Modelling safe protocols for reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Nat. Commun. 12, 1073 (2021).

Di Domenico, L., Sabbatini, C. E., Pullano, G., Lévy-Bruhl, D. & Colizza, V. Impact of January 2021 curfew measures on SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 circulation in France. Eurosurveillance 26, 2100272 (2021).

Di Domenico, L. et al. Adherence and sustainability of interventions informing optimal control against the COVID-19 pandemic. Commun. Med. 1, 1–13 (2021).

Santé publique France. CoviPrev: une enquête pour suivre l’évolution des comportements et de la santé mentale pendant l’épidémie de COVID-19. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/coviprev-une-enquete-pour-suivre-l-evolution-des-comportements-et-de-la-sante-mentale-pendant-l-epidemie-de-covid-19 (2020).

Gimma, A., Wong, K. L., Coletti, P. & Jarvis, C. I. CoMix social contact data (France). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6362893 (2021).

Tran Kiem, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission across age groups in France and implications for control. Nat. Commun. 12, 6895 (2021).

Taube, J. C., Susswein, Z., Colizza, V. & Bansal, S. Characterising non-household contact patterns relevant to respiratory transmission in the USA: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Lancet Digit. Health 7, 100888 (2025).

Shadbolt, N. et al. The challenges of data in future pandemics. Epidemics 40, 100612 (2022).

Davies, N. G. et al. Association of tiered restrictions and a second lockdown with COVID-19 deaths and hospital admissions in England: a modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 482–492 (2021).

Barnard, R. C., Davies, N. G., Jit, M. & Edmunds, W. J. Modelling the medium-term dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in England in the Omicron era. Nat. Commun. 13, 4879 (2022).

Willem, L. et al. SOCRATES: an online tool leveraging a social contact data sharing initiative to assess mitigation strategies for COVID-19. BMC Res. Notes 13, 293 (2020).

Irons, N. J. & Raftery, A. E. Estimating SARS-CoV-2 infections from deaths, confirmed cases, tests, and random surveys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103272118 (2021).

Chinazzi, M. et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 368, 395–400 (2020).

Kraemer, M. U. G. et al. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 368, 493–497 (2020).

Jia, J. S. et al. Population flow drives spatio-temporal distribution of COVID-19 in China. Nature 582, 389–394 (2020).

Kishore, N. et al. Evaluating the reliability of mobility metrics from aggregated mobile phone data as proxies for SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the USA: a population-based study. Lancet Digit. Health 4, e27–e36 (2022).

Delussu, F., Tizzoni, M. & Gauvin, L. The limits of human mobility traces to predict the spread of COVID-19: a transfer entropy approach. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad302 (2023).

Jewell, S. et al. It’s complicated: characterizing the time-varying relationship between cell phone mobility and COVID-19 spread in the US. npj Digit. Med. 4, 1–11 (2021).

Badr, H. S. & Gardner, L. M. Limitations of using mobile phone data to model COVID-19 transmission in the USA. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, e113 (2021).

Pullano, G., Valdano, E., Scarpa, N., Rubrichi, S. & Colizza, V. Evaluating the effect of demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, and risk aversion on mobility during the COVID-19 epidemic in France under lockdown: a population-based study. Lancet Digit. Health 2, e638–e649 (2020).

Loedy, N., Wallinga, J., Hens, N. & Torneri, A. Repetition in social contacts: implications in modelling the transmission of respiratory infectious diseases in pre-pandemic and pandemic settings. Proc. Biol. Sci. 291, 20241296 (2024).

Lloyd-Smith, J. O., Schreiber, S. J., Kopp, P. E. & Getz, W. M. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359 (2005).

Althouse, B. M. et al. Superspreading events in the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2: Opportunities for interventions and control. PLOS Biol. 18, e3000897 (2020).

Adam, D. C. et al. Clustering and superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong. Nat. Med. 26, 1714–1719 (2020).

Davies, N. G. et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat. Med. 26, 1205–1211 (2020).

Viner, R. M. et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adolescents compared with adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 143–156 (2021).

Hogan, A. B. et al. Long-term vaccination strategies to mitigate the impact of SARS-CoV-2 transmission: a modelling study. PLOS Med. 20, e1004195 (2023).

Hu, H., Nigmatulina, K. & Eckhoff, P. The scaling of contact rates with population density for the infectious disease models. Math. Biosci. 244, 125–134 (2013).

The global normalcy index. The Economist https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/tracking-the-return-to-normalcy-after-covid-19 (2021).

Hale, T. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 529–538 (2021).

Kiss, I. Z., Green, D. M. & Kao, R. R. The effect of network mixing patterns on epidemic dynamics and the efficacy of disease contact tracing. J. R. Soc. Interface 5, 791–799 (2008).

Elbasha, E. H. & Gumel, A. B. Vaccination and herd immunity thresholds in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 83, 73 (2021).

INSEE. Estimations de population - Pyramide des âges régionales et départementales. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3696315 (2020).

Santé publique France. Données relatives aux personnes vaccinées contre la Covid-19 (VAC-SI). https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/donnees-relatives-aux-personnes-vaccinees-contre-la-covid-19-1/ (2020).

Borremans, B. et al. Quantifying antibody kinetics and RNA detection during early-phase SARS-CoV-2 infection by time since symptom onset. eLife 9, e60122 (2020).

Gallian, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroprevalence surveys in blood donors before the vaccination campaign, France 2020-2021. iScience 26, 106222 (2023).

Brazeau, N. F. et al. Estimating the COVID-19 infection fatality ratio accounting for seroreversion using statistical modelling. Commun. Med. 2, 1–13 (2022).

Chen, S., Flegg, J. A., White, L. J. & Aguas, R. Levels of SARS-CoV-2 population exposure are considerably higher than suggested by seroprevalence surveys. PLOS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009436 (2021).

Menges, D. et al. Heterogenous humoral and cellular immune responses with distinct trajectories post-SARS-CoV-2 infection in a population-based cohort. Nat. Commun. 13, 4855 (2022).

Peghin, M. et al. The Fall in Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2: a longitudinal study of asymptomatic to critically ill patients up to 10 months after recovery. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59, e01138–21 (2021).

Le Vu, S. et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in France: results from nationwide serological surveillance. Nat. Commun. 12, 3025 (2021).

Santé publique France. Données hospitalières relatives à l’épidémie de COVID-19 (SI-VIC). https://www.data.gouv.fr/datasets/donnees-hospitalieres-relatives-a-lepidemie-de-covid-19.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by: ANR grant DATAREDUX (ANR-19-CE46-0008-03) to V.C.; EU Horizon 2020 grant MOOD (H2020-874850) to V.C., L.D.D.; Horizon Europe grants VERDI (101045989) and ESCAPE (101095619) to V.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C. and L.D.D. conceived and designed the study. V.C., L.D.D., and C.E.S. developed the framework for the synthetic contact matrices. L.D.D. and C.E.S analyzed the data to build the synthetic contact matrices. P.B. and L.O. collected and analyzed the data from the SocialCov survey. L.D.D. developed the code for the comparison. L.D.D. and C.E.S. performed the numerical simulations. L.D.D. analyzed the results. L.D.D., P.B., L.O., and V.C interpreted the results. L.D.D. drafted the article. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the Article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Domenico, L., Bosetti, P., Sabbatini, C.E. et al. Mobility-driven synthetic contact matrices as a scalable solution for real-time pandemic response modeling. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68557-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68557-3