Abstract

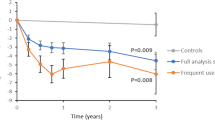

An inverse relationship between physical activity and mortality has been observed in epidemiological surveys, but not in randomized clinical trials. This post hoc, not pre-specified analysis of the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study_2 randomized clinical trial assesses the effect of a physical activity-based counseling intervention on long-term mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. Three hundred physically inactive and sedentary individuals are recruited in three outpatient diabetes clinics in Rome from October 2012 to February 2014. Participants are randomized 1:1 to a Control group receiving standard care and an Intervention group receiving a one-month theoretical and practical counseling targeting both PA and sedentary behavior, each year for 3 years. For this analysis, all-cause and cause-specific mortality are the primary and secondary endpoint, respectively. The vital status is verified on 30 June 2024 and all participants are analyzed. After a 10.3-year follow-up, the number of deaths is significantly lower among Intervention than Control participants (18 vs 35, p = 0.010), mainly due to fewer cancer deaths. Age-and sex-adjusted hazard ratios for mortality are significantly lower in Intervention versus Control participants (0.498 [0.282-0.879], p = 0.016) and between-group differences remain after further adjustment for treatments and baseline cardiometabolic risk profile, major complications, and physical activity and fitness level (0.414 [0.229-0.750], p = 0.004). Limitations include the post hoc type of analysis, a post-trial observational follow-up with no assessment of physical activity and fitness parameters, possible unmeasured confounders, and the non-generalizability to different populations. A behavioral counselling targeting all domains of physical activity and sedentary behavior is associated with reduced long-term mortality risk in people with type 2 diabetes. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01600937.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The raw data are available under restricted access due to the inclusion of confidential information. For strictly research purposes, access can be obtained by the corresponding author (giuseppe.pugliese@uniroma1.it) on reasonable request within 3 months. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Paffenbarger, R. S., Hyde, R. T. Jr, Wing, A. L. & Hsieh, C. C. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of college alumni. N. Engl. J. Med. 314, 605–613 (1986).

Fishman, E. I. et al. Association between objectively measured physical activity and mortality in NHANES. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 48, 1303–1311 (2016).

Moore, S. C. et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 9, e1001335 (2012).

Ekelund, U. et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all-cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 366, l4570 (2019).

Ekelund, U. et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 388, 1302–1310 (2016).

Blair, S. N. et al. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA 262, 2395–2401 (1989).

Myers, J. et al. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 793–801 (2002).

Ruiz, J. R. et al. Association between muscular strength and mortality in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ 337, a439 (2008).

Church, T. S., Earnest, C. P., Skinner, J. S. & Blair, S. N. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297, 2081–2091 (2007).

Celis-Morales, C. A. et al. The association between physical activity and risk of mortality is modulated by grip strength and cardiorespiratory fitness: evidence from 498135 UK-Biobank participants. Eur. Heart J. 38, 116–122 (2017).

Hu, G. et al. Physical activity, cardiovascular risk factors, and mortality among Finnish adults with diabetes. Diab. Care 28, 799–805 (2005).

Church, T. S., LaMonte, M. J., Barlow, C. E. & Blair, S. N. Cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index as predictors of cardiovascular disease mortality among men with diabetes. Arch. Intern. Med. 165, 2114–2120 (2005).

Tancredi, M. et al. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1720–1732 (2015).

Resnick, H. E., Foster, G. L., Bardsley, J. & Ratner, R. E. Achievement of American Diabetes Association clinical practice recommendations among U.S. adults with diabetes, 1999-2002: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diab. Care 29, 531–537 (2006).

Li, G. et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 2, 474–480 (2014).

Gong, Q. et al. Morbidity and mortality after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance: 30-year results of the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 7, 452–461 (2019).

Uusitupa, M. et al. Ten-year mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study-secondary analysis of the randomized trial. PLoS One 4, e5656 (2009).

Lee, C. G. et al. Effect of Metformin and Lifestyle Interventions on Mortality in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diab. Care 44, 2775–2782 (2021).

Look AHEAD Research Group, W. ingR. R. et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 145–154 (2013).

Look AHEAD Research Group. Effects of intensive lifestyle intervention on all-cause mortality in older adults with type 2 diabetes and overweight/obesity: results from the look AHEAD study. Diabetes Care. 45, 1252–1259 (2022).

Balducci, S. et al. Effect of a behavioral intervention strategy on sustained change in physical activity and sedentary behavior in patients with type 2 diabetes: the IDES_2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 321, 880–890 (2019).

Balducci, S. et al. Relationships of changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior with changes in physical fitness and cardiometabolic risk profile in individuals with type 2 diabetes: the Italian diabetes and exercise Study 2 (IDES_2). Diab. Care 45, 213–221 (2022).

O’Connor, E. A., Evans, C. V., Rushkin, M. C., Redmond, N. & Lin, J. S. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 324, 2076–2094 (2020).

Nicolucci, A. et al. Effect of a behavioural intervention for adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle on psychological well-being and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes: the IDES_2 Randomized Clinical Trial. Sports Med. 52, 643–654 (2022).

Watkins, K. W. et al. Effect of adults’ self–regulation of diabetes on quality-of-life outcomes. Diab. Care 23, 1511–1515 (2000).

Teixeira, D. S., Rodrigues, F., Cid, L. & Monteiro, D. Enjoyment as a predictor of exercise habit, intention to continue exercising, and exercise frequency: the intensity traits discrepancy moderation role. Front. Psychol. 13, 780059 (2022).

Middleton, K. R., Anton, S. D. & Perri, M. G. Long-Term Adherence to Health Behavior Change. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 7, 395–404 (2013).

Shea, M. K. et al. The effect of randomization to weight loss on total mortality in older overweight and obese adults: the ADAPT Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 65, 519–525 (2010).

Yu, L. et al. Influence of a diet and/or exercise intervention on long-term mortality and vascular complications in people with impaired glucose tolerance: Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome study. Diab. Obes. Metab. 26, 1188–1196 (2024).

Look AHEAD Research Group, G. reggE. W. et al. Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 4, 913–921 (2016).

Gong, Q. et al. Long-term effects of a randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired glucose tolerance on diabetes-related microvascular complications: the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Diabetologia 54, 300–307 (2011).

Lindström, J. et al. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS): Lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diab. Care 26, 3230–3236 (2003).

Ratner, R. et al. Impact of intensive lifestyle and metformin therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors in the diabetes prevention program. Diab. Care 28, 888–894 (2005).

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3, 866–875 (2015).

Look AHEAD Research Group, W. ingR. R. Long-term effects of a lifestyle intervention on weight and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: four-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 170, 1566–1575 (2010).

Look AHEAD Research Group. Effect of a long-term behavioural weight loss intervention on nephropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a secondary analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 2, 801–809 (2014).

Faulconbridge, L. F. et al. One-year changes in symptoms of depression and weight in overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes in the Look AHEAD study. Obesity 20, 783–793 (2012).

Gregg, E. W. et al. Impact of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on Disability-Free Life Expectancy: The Look AHEAD Study. Diab. Care 41, 1040–1048 (2018).

Harris, T. et al. Physical activity levels in adults and older adults 3-4 years after pedometer-based walking interventions: long-term follow-up of participants from two randomised controlled trials in UK primary care. PLoS Med. 15, e1002526 (2018).

Khunti, K. et al. Promoting physical activity in a multi-ethnic population at high risk of diabetes: the 48-month PROPELS randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 19, 130 (2021).

Andrews, R. C. et al. Diet or diet plus physical activity versus usual care in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: the Early ACTID randomised controlled trial. Lancet 378, 129–139 (2011).

Unick, J. L. et al. Four-year physical activity levels among intervention participants with type 2 diabetes. Med Sci. Sports Exerc 48, 2437–2445 (2016).

Diaz, K. M. et al. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in U.S. Middle-Aged and Older Adults: a national Cohort Study. Ann. Intern Med 167, 465–475 (2017).

Chastin, S. F. M. et al. How does light-intensity physical activity associate with adult cardiometabolic health and mortality? Systematic review with meta-analysis of experimental and observational studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 53, 370–376 (2019).

Matthews, C. E. et al. Accelerometer-measured dose-response for physical activity, sedentary time, and mortality in US adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 104, 1424–1432 (2016).

Lee, I. M. et al. Association of step volume and intensity with all-cause mortality in older women. JAMA Intern Med 179, 1105–1112 (2019).

Saint-Maurice, P. F. et al. Association of daily step count and step intensity with mortality among US Adults. JAMA 323, 1151–1160 (2020).

Ekelund, U. et al. Do the associations of sedentary behaviour with cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer mortality differ by physical activity level? A systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis of data from 850 060 participants. Br. J. Sports Med. 53, 886–894 (2019).

Dempsey, P. C. et al. Physical activity volume, intensity, and incident cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 43, 4789–4800 (2022).

Biswas, A. et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 123–132 (2015).

Balducci, S. et al. The Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study 2 (IDES-2): a long-term behavioral intervention for adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle. Trials 16, 569 (2015).

Di Loreto, C. et al. Validation of a counseling strategy to promote the adoption and the maintenance of physical activity by type 2 diabetic subjects. Diab. Care 26, 404–408 (2003).

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2012. Diab. Care 35, S11–S63 (2012).

Balducci, S. et al. Sustained decreases in sedentary time and increases in physical activity are associated with preservation of estimated β-cell function in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diab. Res. Clin. Pr. 193, 110140 (2022).

Balducci, S. et al. Sustained increase in physical fitness independently predicts improvements in cardiometabolic risk profile in type 2 diabetes. Diab. Metab. Res Rev. 39, e3671 (2023).

Orsi, E. et al. Haemoglobin A1c variability is a strong, independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diab. Obes. Metab. 20, 1885–1893 (2018).

Matthews CE. Calibration of accelerometer output for adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 37, S512–S522 (2005).

Freedson, P. S., Melanson, E. & Sirard, J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 30, 777–781 (1998).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. Compendium of physical activities: classifications of energy costs of human physical activities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc 25, 71–80 (1993).

Blair, S. N. et al. Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. JAMA 273, 1093–1098 (1995).

Stevens, R. J., Kothari, V., Adler, A. I. & Stratton, I. M. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in Type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin. Sci. 101, 671–679 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank the IDES and IDES_2 Investigators for participating in the trials (see Supplementary Information). This work was supported by the Metabolic Fitness Association, Monterotondo (Rome), Italy to SB and the Ministero della Salute grant PNRR-MAD-2022-12375970 funded by the European Union - Next Generation EU - NRRP M6C2 - Investment 2.1 Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research in the NHS to GP. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

S.B., J.H., and G.P. conceived the study. S.B., J.H., M.V., L.M., F.C., M.M., E.C., F.A., A.G., M.S., G.O., S.Z., and G.P. acquired the data. A.N. and G.P. performed the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data. G.P. drafted the manuscript, which was critically revised by all authors, who approved the final version and agree to be accountable for it. S.B., J.H., and G.P. have directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in this manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

SB received personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda; JH received personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim; MV received personal fees from MundiPharma and Novo Nordisk; SZ is an employer of Technogym; AN received grants from Artsana, Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis and personal fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk; GP received personal fees from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dome, Mylan, Sigma-Tau, and Takeda. No other disclosures were reported.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Richard Woodman and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Balducci, S., Haxhi, J., Vitale, M. et al. Effect of a behavioral counseling for adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle on long-term mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: post hoc analysis of the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study_2. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68618-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68618-7