Abstract

Lipopeptide natural products are essential agents against multidrug-resistant bacteria, but their clinical utility is often constrained by toxicity and resistance. Here, we compare the mechanisms of action of two superficially similar lipopeptide antibiotics: colistin, a last-line treatment for Gram-negative infections, and turnercyclamycins, a new class active against certain colistin-resistant strains. Both antibiotics require lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis, even when LPS transport to the outer membrane (OM) is impaired. Colistin rapidly disrupts both the OM and the cytoplasmic membrane (CM), causing swift bacterial death. Turnercyclamycins, by contrast, act independently of the CM, with delayed OM disruption. Unlike colistin, which binds LPS directly to damage membranes, turnercyclamycins show no measurable LPS binding by calorimetry. Instead, their activity is modulated by different phospholipids, as confirmed by phospholipidomic profiling on whole cells, which identifies alterations in bacterial lipid biosynthesis and membrane homeostasis. These findings support a mechanistically distinct mode of action for turnercyclamycins, which we propose to correlate with their different pharmacological properties and potential therapeutic applications. Our results highlight how subtle structural differences between lipopeptides can lead to major functional divergence, offering a framework for the rational design of next-generation antibiotics with improved safety and efficacy profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The DiSC3(5) microscopy data generated in this study have been deposited in FigShare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30865277). Lipidomics data are available at the NIH Common Fund’s National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR)79 website, the Metabolomics Workbench, https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org where it has been assigned Study ID ST004466. The data can be accessed directly via its Project https://doi.org/10.21228/M84Z8T. This work is supported by NIH grant U2C-DK119886 and OT2-OD030544 grants. All other data are available in the article and its Supplementary files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Naghavi, M. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: a systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 404, 1199–1226 (2024).

WHO, https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/newborn-health/newborn-infections (2025).

Wen, S. C. H. et al. Gram-negative neonatal sepsis in low- and lower-middle-income countries and WHO empirical antibiotic recommendations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 18, e1003787 (2021).

Andrade, F. F., Silva, D., Rodrigues, A. & Pina-Vaz, C. Colistin update on its mechanism of action and resistance, present and future challenges. Microorganisms 8, 1716 (2020).

Trimble, M. J., Mlynárčik, P., Kolář, M. & Hancock, R. E. Polymyxin: alternative mechanisms of action and resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 6, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a025288 (2016).

Ledger, E. V. K., Sabnis, A. & Edwards, A. M. Polymyxin and lipopeptide antibiotics: membrane-targeting drugs of last resort. Microbiology 168, https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001136 (2022).

Lepak Alexander, J., Wang, W. & Andes David, R. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of MRX-8, a novel polymyxin, in the neutropenic mouse thigh and lung infection models against gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01517–e01520 (2020).

Duncan Leonard, R., Wang, W. & Sader Helio, S. In vitro potency and spectrum of the novel polymyxin MRX-8 tested against clinical isolates of gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 66, e00139–00122 (2022).

Bruss, J. et al. Single- and multiple-ascending-dose study of the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of the polymyxin derivative SPR206. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 65, 00739–00721 (2021).

Rodvold, K. A., Bader, J., Bruss, J. B. & Hamed, K. Pharmacokinetics of SPR206 in plasma, pulmonary epithelial lining fluid, and alveolar macrophages following intravenous administration to healthy adult subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0042623 (2023).

Zurawski, D. V. et al. SPR741, an antibiotic adjuvant, potentiates the in vitro and in vivo activity of rifampin against clinically relevant extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01239-17 (2017).

Götze, S. et al. Structure, biosynthesis, and biological activity of the cyclic lipopeptide anikasin. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2498–2502 (2017).

Yamanaka, K. et al. Direct cloning and refactoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1957–1962 (2014).

Bekiesch, P. et al. Viennamycins: lipopeptides produced by a Streptomyces sp. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 2381–2389 (2020).

Miller, B. W. et al. Shipworm symbiosis ecology-guided discovery of an antibiotic that kills colistin-resistant Acinetobacter. Cell Chem. Biol. 28, 1628–1637.e1624 (2021).

Lim, A. L. et al. Resistance mechanisms for Gram-negative bacteria-specific lipopeptides, turnercyclamycins, differ from that of colistin. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e02306–e02323 (2023).

Simpson, B. W. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii can survive with an outer membrane lacking lipooligosaccharide due to structural support from elongasome peptidoglycan synthesis. mBio 12, e03099–03021 (2021).

Huang, H. W. DAPTOMYCIN, its membrane-active mechanism vs. that of other antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1862, 183395 (2020).

Benfield, A. H. & Henriques, S. T. Mode-of-action of antimicrobial peptides: membrane disruption vs. intracellular mechanisms. Front. Med. Technol. 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmedt.2020.610997 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Outer-membrane-acting peptides and lipid II-targeting antibiotics cooperatively kill Gram-negative pathogens. Commun. Biol. 4, 31 (2021).

Stephani, J. C., Gerhards, L., Khairalla, B., Solov’yov, I. A. & Brand, I. How do antimicrobial peptides interact with the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria? Role of lipopolysaccharides in peptide binding, anchoring, and penetration. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 763–778 (2024).

Epand, R. M., Walker, C., Epand, R. F. & Magarvey, N. A. Molecular mechanisms of membrane targeting antibiotics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1858, 980–987 (2016).

Zou, W. et al. Exploring the active core of a novel antimicrobial peptide, palustrin-2LTb, from the Kuatun frog, Hylarana latouchii, using a bioinformatics-directed approach. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 6192–6205 (2022).

Giacometti, A., Cirioni, O., Greganti, G., Quarta, M. & Scalise, G. In vitro activities of membrane-active peptides against Gram-positive and Gram-negative aerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 3320–3324 (1998).

Sabnis, A. et al. Colistin kills bacteria by targeting lipopolysaccharide in the cytoplasmic membrane. eLife 10, e65836 (2021).

Cerny, G. & Teuber, M. Differential release of periplasmic versus cytoplasmic enzymes from Escherichia coli B by polymyxin B. Arch. Mikrobiol. 78, 166–179 (1971).

Schindler, P. R. G. & Teuber, M. Action of polymyxin B on bacterial membranes: morphological changes in the cytoplasm and in the outer membrane of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 8, 95–104 (1975).

Nakajima, K. & Kawamata, J. Studies on the mechanism of action of colistin. IV. Activation of “latent” ribonuclease in Escherichia coli by colistin. Biken J. 9, 115–123 (1966).

Teuber, M. Precipitation of ribosomes from E. coli B by polymyxin B. Naturwissenschaften 54, 71 (1967).

McCoy, L. S. et al. Polymyxins and analogues bind to ribosomal RNA and interfere with eukaryotic translation in vitro. Chembiochem 14, 2083–2086 (2013).

Saugar, J. M. et al. Activities of polymyxin B and cecropin A-melittin peptide CA(1-8)M(1-18) against a multiresistant strain of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 875–878 (2002).

Dwyer, D. J., Kohanski, M. A., Hayete, B. & Collins, J. J. Gyrase inhibitors induce an oxidative damage cellular death pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 91 (2007).

Brochmann, R. P. et al. Bactericidal effect of colistin on planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa is independent of hydroxyl radical formation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43, 140–147 (2014).

Bailey, J. et al. Essential gene deletions producing gigantic bacteria. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008195 (2019).

Elliott, K. T. & Neidle, E. L. Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1: transforming the choice of model organism. IUBMB Life 63, 1075–1080 (2011).

Machovina, M. M. et al. Enabling microbial syringol conversion through structure-guided protein engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 13970–13976 (2019).

Xu, F. et al. Critical role of 3’-downstream region of pmrB in polymyxin resistance in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Microorganisms 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030655 (2021).

Helander, I. M. & Mattila-Sandholm, T. Fluorometric assessment of gram-negative bacterial permeabilization. J. Appl Microbiol. 88, 213–219 (2000).

Muheim, C. et al. Increasing the permeability of Escherichia coli using MAC13243. Sci. Rep. 7, 17629 (2017).

Mood, E. H. et al. Antibiotic potentiation in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria by a synthetic peptidomimetic. ACS Infect. Dis. 7, 2152–2163 (2021).

Heesterbeek, D. A. C. et al. Complement-dependent outer membrane perturbation sensitizes Gram-negative bacteria to Gram-positive specific antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 9, 3074 (2019).

Buttress, J. A. et al. A guide for membrane potential measurements in Gram-negative bacteria using voltage-sensitive dyes. Microbiology 168, https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.001227 (2022).

Boix-Lemonche, G., Lekka, M. & Skerlavaj, B. A rapid fluorescence-based microplate assay to investigate the interaction of membrane active antimicrobial peptides with whole Gram-positive bacteria. Antibiotics 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9020092 (2020).

Strahl, H. & Hamoen, L. W. Membrane potential is important for bacterial cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12281–12286 (2010).

Howe, J. et al. Thermodynamic analysis of the lipopolysaccharide-dependent resistance of Gram-negative bacteria against polymyxin B. Biophys. J. 92, 2796–2805 (2007).

Wouters, C. L. et al. Breaking membrane barriers to neutralize E. coli and K. pneumoniae virulence with PEGylated branched polyethylenimine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1865, 184172 (2023).

Srimal, S., Surolia, N., Balasubramanian, S. & Surolia, A. Titration calorimetric studies to elucidate the specificity of the interactions of polymyxin B with lipopolysaccharides and lipid A. Biochem. J. 315, 679–686 (1996).

Botte, M. et al. Cryo-EM structures of a LptDE transporter in complex with Pro-macrobodies offer insight into lipopolysaccharide translocation. Nat. Commun. 13, 1826 (2022).

Sherman, D. J. et al. Lipopolysaccharide is transported to the cell surface by a membrane-to-membrane protein bridge. Science 359, 798–801 (2018).

Bos, M. P., Tefsen, B., Geurtsen, J. & Tommassen, J. Identification of an outer membrane protein required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the bacterial cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9417–9422 (2004).

Putker, F., Bos, M. P. & Tommassen, J. Transport of lipopolysaccharide to the Gram-negative bacterial cell surface. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 985–1002 (2015).

Wu, T. et al. Identification of a protein complex that assembles lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11754–11759 (2006).

Anderson, M. S., Bulawa, C. E. & Raetz, C. R. The biosynthesis of gram-negative endotoxin. Formation of lipid A precursors from UDP-GlcNAc in extracts of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 15536–15541 (1985).

Williams, A. H. & Raetz, C. R. H. Structural basis for the acyl chain selectivity and mechanism of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13543–13550 (2007).

Lieberman, L. A. Outer membrane vesicles: a bacterial-derived vaccination system. Front. Microbiol. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1029146 (2022).

Reimer, S. L. et al. Comparative analysis of outer membrane vesicle isolation methods with an Escherichia coli tolA mutant reveals a hypervesiculating phenotype with outer-inner membrane vesicle content. Front. Microbiol. 12, 628801 (2021).

Bernadac, A., Gavioli, M., Lazzaroni, J. C. & Raina, S. & Lloubès, R. Escherichia coli tol-pal mutants form outer membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 180, 4872–4878 (1998).

Li, X. et al. The attenuated protective effect of outer membrane vesicles produced by a mcr-1 positive strain on colistin sensitive Escherichia coli. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 701625 (2021).

Few, A. V. The interaction of polymyxin E with bacterial and other lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 16, 137–145 (1955).

Araki, T., Hiroguchi, J., Matsunaga, H. & Kimura, Y. Potentiating effect of lysophosphatidylcholine on antibacterial activity of polymyxin antibiotics. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 33, 1729–1733 (1985).

Imai, M., Inoue, K. & Nojima, S. Effect of polymyxin B on liposomal membranes derived from Escherichia coli lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 375, 130–137 (1975).

Zhao, X. et al. Elucidating the mechanism of action of the Gram-negative-pathogen-selective cyclic antimicrobial lipopeptide brevicidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e00010–e00023 (2023).

Giordano Nicole, P., Cian Melina, B. & Dalebroux Zachary, D. Outer membrane lipid secretion and the innate immune response to Gram-negative bacteria. Infect. Immun. 88, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00920-19 (2020).

Coudray, N. et al. Structure of bacterial phospholipid transporter MlaFEDB with substrate bound. eLife 9, e62518 (2020).

Han, M.-L. et al. Comparative metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal multiple pathways associated with polymyxin killing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mSystems 4, 00149–00118 (2019). 10.1128/msystems.

Mahamad Maifiah, M. H. et al. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses of the synergistic effect of polymyxin–rifampicin combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biomed. Sci. 29, 89 (2022).

Tao, Y. et al. Colistin treatment affects lipid composition of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics 10, 528 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. Polymyxins bind to the cell surface of unculturable Acinetobacter baumannii and cause unique dependent resistance. Adv. Sci. 7, 2000704 (2020).

Wyckoff, T. J. O. & Raetz, C. R. H. The active site of Escherichia coli UDP-N-acetylglucosamine acyltransferase: chemical modification and site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27047–27055 (1999).

Mohan, S., Kelly, T. M., Eveland, S. S., Raetz, C. R. & Anderson, M. S. An Escherichia coli gene (FabZ) encoding (3R)-hydroxymyristoyl acyl carrier protein dehydrase. Relation to fabA and suppression of mutations in lipid A biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32896–32903 (1994).

Zhang, Y.-M. & Rock, C. O. in (eds Ridgway, N. D. & McLeod, R. S.) Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes, Sixth Edition, 73–112 (Elsevier, 2016).

Bertani, B. & Ruiz, N. Function and biogenesis of lipopolysaccharides. EcoSal Plus 8, https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0001-2018 (2018).

Thomanek, N. et al. Intricate crosstalk between lipopolysaccharide, phospholipid and fatty acid metabolism in Escherichia coli modulates proteolysis of LpxC. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2018 (2019).

Gallagher, L. A. et al. Resources for genetic and genomic analysis of emerging pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2027–2035 (2015).

Lewis II, J. S. et al. CLSI M100-Ed35 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Standards. 35th Edition, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2025).

Matyash, V., Liebisch, G., Kurzchalia, T. V., Shevchenko, A. & Schwudke, D. Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1137–1146 (2008).

Koelmel, J. P. et al. LipidMatch: an automated workflow for rule-based lipid identification using untargeted high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 331 (2017).

Xia, J., Sinelnikov, I. V., Han, B. & Wishart, D. S. MetaboAnalyst 3.0—making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W251–W257 (2015).

Sud, M. et al. Metabolomics Workbench: an international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 4, D463–D470 (2016).

Acknowledgements

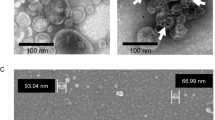

We thank Colin Manoil and Jeannie Bailey, from the University of Washington, for providing us with wild type and knockout mutants of both Acinetobacter baumannii 5075UW and Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1. We would like to thank Matthew Mulvey, from the University of Utah, for supplying E. coli C600. We would also like to thank Basil Mathew of the University of Utah Department of Pathology for worthwhile discussions. We are grateful for the assistance of John Alan Maschek of University of Utah Metabolomics Core for the lipidomic analysis, Xiang Wang of the University of Utah Cell Imaging Core for the fluorescence microscopy experiments, and to Nancy Chandler and David Belnap of the University of Utah Electron Microscopy Core for the transmission electron microscopy experiments. We would like to thank Amy Barrios of the University of Utah for the use of her plate reader for fluorescence spectroscopy experiments. We would also like to acknowledge the help of Debbie Eckert and Michael Kay for assistance in the isothermal calorimetry experiments. Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, National Institutes of Health (NIH R01AI162943). Albebson Lim was also funded by the University of Utah L.S. Skaggs Graduate Student Fellowship provided by the Skaggs Institute for Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L.L. and E.W.S. conceptualized and designed the study. A.L.L. and B.W.M. performed experiments and analyzed data. A.L.L., B.W.M., and E.W.S. wrote the manuscript. A.L.L., B.W.M., M.A.F., M.G.H., L.R.B., and E.W.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. E.W.S. and A.L.L. acquired funding for the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: E.W.S., B.W.M., and M.G.H. have submitted a patent application for turnercyclamycins. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, A.L., Miller, B.W., Fisher, M.A. et al. Differential membrane lipid disruption by lipopeptide antibiotics, colistin and turnercyclamycins. Nat Commun (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68681-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-026-68681-0