Abstract

Rhizobial nitrogen fixation in legumes provides spillover benefits to neighbouring plants such as pasture grasses. Generally, it is understood to be unidirectional between plant functional groups, providing a benefit from legumes to grasses. We question whether bidirectional complementarity also exists in terms of exploiting the wider soil nutrient pool. We test this hypothesis using soil cores with their component vegetation assemblages sampled from a hill country pasture in South Island, New Zealand. The soil was deficient in key essential elements: P, S, B, Mo and Ni. Facilitation from grasses to clovers was evident; legume–grass mixtures procured more nutrients from the soil than when either species was growing alone. When grasses and clover grow together in unfertilized grassland, more nitrogen is procured by the plant community, and other limiting plant nutrients in the soil are better exploited. Coexistence with grasses is favourable to clovers in terms of soil biogeochemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Mid-altitude grasslands (approximately 400–1,000 m above sea level, with slopes >15°) account for around 18% of the total land area of New Zealand1. This pastoral hill country farmland was converted from forests, mostly in the past few centuries, and contributes substantially to the economy2. Vegetation productivity and stocking rates are constrained by a hot and dry summer climate combined with nutrient-poor, low-pH, shallow soils. Steeper slopes are prone to erosion, and typically only about 10–20% of this land is sufficiently flat to be cultivated for crops. Grazing herbage consists largely of introduced exotic species with some remnants of native grasses and shrubs. Native species are less productive, and nitrogen-fixing forbs are almost entirely absent from the indigenous flora3. Pastoral farming is reliant on over-sowing with seeds of more productive introduced grasses and legumes, and top-dressing with fertilizers and lime. The latter is prohibitively expensive due to the large expanse of this landscape and its difficult trafficability that requires the use of aircraft. Opportunities to establish productive pasture, such as ryegrass–white clover swards, are restricted; hardier drought-tolerant perennial grasses tend to proliferate. Pasture management aims to improve forage quality by increasing the prevalence of annual and perennial legumes, rather than relying on vegetation dominated by hardier grasses of less forage value4,5. Stock (mostly sheep) productivity and health are markedly improved by increasing the establishment, productivity and persistence of naturalized nitrogen-fixing plants. The hill country environment as described provides the template for this study.

We question whether we properly understand the mutualism between grasses and clovers (Trifolium spp.) in terms of soil biogeochemistry. It is well known that nitrogen fixed by legumes can be utilized by grasses or other companion plants6. Nitrogen fixation can be substantially constrained by soil acidity and a limiting supply of key nutrients such as phosphorus, especially without fertilizer intervention. It has become clearer recently that multiple-nutrient constraints widely impact primary productivity in grasslands7,8. Plant species differ in their ability to acquire key nutrients. For example, P is obtained through symbiotic mycorrhizal associations9 or through root adaptations to resource partitioning of this element10. Other plants, including grasses, can secrete organic acids (phytosiderophores) that mobilize deficient chemical elements (for example, Fe, Zn, Cu and Mn) in soil11. Competition for resources is more extensively studied than are the mutual benefits that may be derived from the coexistence of different plant species or functional groups, although the temporal and spatial advantages of plants growing together are well known12,13,14. Belowground functional traits in plants are recognized to be important for nutrient uptake, but interactions between root systems and possible complementarity between species are poorly understood15. However, there would be an obvious advantage to a plant of sharing limiting soil resources with a neighbouring species if there were a reduced metabolic cost to both16.

In the present study, we hypothesize that clovers benefit from the presence of companion grasses in terms of procuring essential nutrients, and this relationship is not limited to the spillover of nitrogen from clovers that is subsequently exploited by grasses. We aim to determine whether complementarity between legume and grass rhizospheres is bidirectional in nutritional terms and more substantial than we currently realize. We extracted 200 soil cores with their component plant assemblages from a hill country sheep station to investigate how the soil pool of nutrients was exploited. The cores were maintained as experimental microcosms in a controlled-environment growth chamber that simulated historic ambient temperature and sunlight conditions without limiting water availability. The study had three objectives: (1) to evaluate existing small-scale variability of nutrient mobility and uptake, (2) to investigate whether grasses modify the nutrient content of clovers and (3) to explore the extent to which the manipulation of key soil nutrients modifies the nutrition of clover–grass assemblages. Three separate experiments were designed to pursue these objectives.

Clovers produced more aboveground biomass than grasses in all soils below pH 7, growing significantly better in the more acidic soils, where yields were double those of grasses (Supplementary Fig. 1). There was an effect of soil pH on the mobility and uptake of nutrients (Fig. 1). The optimal pH for the uptake of most nutrients was in the range of 5–6.5, but analyses of these cores indicated that there is considerable small-scale spatial variability across the sampling site both below and above this pH range (Fig. 2). Nutrient concentrations in pore water tended to be higher in lower-pH soil cores for six elements (P, S, Fe, Ni, B and Zn). Except for B, this was reflected in foliar concentrations of the same elements in clover or grasses or in both. Foliar concentrations of Mo were unique in this dataset, substantially declining in lower-pH cores. Three elements (P, Mo and Ni) were at significantly higher foliar concentrations in grasses than in clovers, and five elements (K, Ca, Mg, Zn and B) were in much higher concentrations in clover foliage. Manganese concentrations in soil pore water varied in the opposite direction to concentrations in foliage, which may be a result of the plants readily taking up this element through non-specific transporters17 and depleting mobile forms of this element in the soil. We have found previously that pore water data collected from rhizon samplers can be variable and unreliable depending on pathways of water flow through the soil, which can produce a rapid flush into the sampler or a slow seepage, thus providing differing amounts of time to accumulate solutes. A range of complex interactions occur in the rhizosphere that are likely to be critical to the mobilization of nutrients and to accessing discrete resources from the same soil volume13, which undoubtedly play an important role in grassland productivity7,18.

Mass uptake of each nutrient from the soil into the foliage of clovers and grasses growing in cores across the soil pH range (means, n = 5).

Nutrient concentrations in the foliage of clovers (mg kg−1, n = 5) and grasses (mg kg−1, n = 5) and in soil pore water (mg l−1, n = 3) across the pH range of the soil cores. The right y axes are for pore water. Shading indicates standard deviations about the means. The points are means.

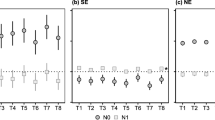

In the second experiment, clovers were competitively dominant in terms of yield when growing in mixed-species assemblages with grasses and appeared to be the main beneficiary of coexistence. Growing as single species, the yield of clovers was approximately double that of grasses and did not significantly differ in the presence of grasses (Fig. 3). Conversely, grass yield was reduced by approximately half when growing in mixtures. Clover had higher foliar concentrations of the major nutrients N, P, K, S and Ni when growing in combination with grasses (Fig. 4). Clovers but not grasses acquired more N when growing in combination, and there was no evidence of N spillover to grasses. Grasses benefited by growing together with clovers through higher foliar concentrations of only Cu and Ni. Potassium, Ca, Mn and B concentrations in grasses were significantly lower when they grew with clovers. Soil pore water contained higher Fe concentrations in cores with only grasses and higher Zn concentrations in cores with clover–grass mixtures (Supplementary Fig. 2). When these data are analysed using mass balance (Fig. 5), mixed-species assemblages extracted significantly larger quantities of three elements (P, S and Fe) from soil than when either grasses or clovers were growing alone. This is largely explained by the increased combined biomass in mixed-species assemblages and by lower yields of grasses in mixture. However, differences in foliar nutrient concentrations between clovers and grasses also contribute substantially to quite different exploitation of the nutrient content of the soil cores. When growing as single species, clovers captured more of 9 of the 13 elements than grasses. Grasses were more efficient than clovers at procuring only Mo from the soil, which is a particularly critical element for N fixation in legumes19.

Biomass yields of clovers and grasses growing either alone or in a mixed-species assemblage (mean + s.d., n = 10). The uppercase letters show significant differences (P < 0.05) between clovers; the lowercase letters show significant differences between grasses. The data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following log transformation where data were not normally distributed.

Nutrient concentrations in the foliage of clovers and grasses according to whether they were growing alone (solid boxes) or in mixed-species assemblages (striped boxes) (n = 10). The asterisks show significant differences (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The box plots show the upper quartile, median and lower quartile from top to bottom (stars inside the boxes are means; points outside the boxes were excluded from the statistical analysis as outliers; whiskers indicate data range). The data were analysed using one-way ANOVA following log transformation where data were not normally distributed.

Total uptake of nutrients from soil cores that supported clovers or grasses growing either alone or in mixed-species assemblages (n = 10). The asterisks show significant differences (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The box plots show the upper quartile, median and lower quartile from top to bottom (stars inside the boxes are means; points outside the boxes were excluded from the statistical analysis as outliers; whiskers indicate data range). The data were analysed using one-way ANOVA following log transformation where data were not normally distributed.

In the third experiment, adding nutrients to the soil cores had a negligible effect on plant yield, except adding P (Fig. 6). We interpret this finding as a failure to apply the fertilizers early enough in the growth season when the plants were entering their most productive phase of the growth cycle. Nevertheless, the manipulation of key soil nutrients using fertilizer to improve the productivity of clover–grass assemblages has been well described previously in the field situation6,7,20,21 and may have added little to the present findings in relation to unfertilized pasture.

Biomass yield of mixed clover–grass assemblages after fertilizing the soil cores with sulfur (+S), molybdenum (+Mo), manganese (+Mn) or phosphorus (+P). The fertilizers were applied twice, after the first and second harvests (n = 10; third harvest, n = 5). The open bars (R) are for the reference cores (n = 10; third harvest, n = 5) without fertilizer amendment. The asterisk shows a significant difference (*P < 0.05). The red x’s indicate the means; the diamonds indicate data points excluded from the statistical analysis as outliers. The box plots show the upper quartile, median and lower quartile from top to bottom. The data were analysed using one-way ANOVA following log transformation where data were not normally distributed.

Contrary to the field situation in the high country, clovers were significantly more productive than grasses in the microcosms (apart from cores with soil pH >7). In the field, there is no doubt that grasses generally tend to become dominant without proactive management of grazing and fertility. This is largely a consequence of low rates of naturalization of clovers and the inability of both annual and perennial clovers to withstand summer drought without going to seed. The moisture conditions that were maintained in the soil cores favoured the clovers over the more drought-tolerant perennial grasses. The present experimental work did not realistically match the field situation in terms of simulating typical moisture deficits, but it was considered more important to maintain suitable conditions for plant growth. Modelling the effect of soil moisture deficit on nutrient cycling requires more work.

While soil nutrient analysis data have drawn attention to deficiencies of P, S, B, Mo and Ni in these acid soils, the biogeochemical complexities of nutrient mobility within the rhizosphere makes the prediction of key deficient elements less straightforward22. Nevertheless, many of the findings of the present study are explained by existing knowledge of nutrient mobility in soils and plants. For example, S, Fe and Zn were at higher concentrations in pore water at lower pH, and this was reflected in plant tissue concentrations. This would be expected for the two metals that are more soluble in acid conditions and enter plants through passive flow. Low concentrations in pore water may simply reflect plant uptake and depletion of the labile soil pool; for example, the lowest concentrations of Mn in pore water occurred alongside high concentrations in foliage. Foliar Mn is known to be closely associated with P acquisition in the rhizosphere17. Other pore water concentrations are less easy to explain, and the reliability of the pore water data is likely to be questionable. For example, soluble phosphate and the availability of this element to plants are the highest at pH 6–7 (ref. 23), but this is not reflected in the data in the present study. Boron is known to be the most available under neutral-pH conditions in soils and is readily leached at low pH, but, like Ni, its apparent lack of correlation with soil pH may be indicative of the very low soil concentrations of these elements. At higher pH, pore water concentrations of five other elements (K, Ca, Mg, Mn and Mo) appeared to be generally more labile.

Our data do not elucidate the exact processes of the interaction between clovers and grasses, and more detailed mechanistic studies are required to guide further thinking and experimentation. Interactions between different nutrients within the rhizosphere undoubtedly played a large role in our findings. The main reason for adding lime to hill country soils is to increase the mobility and availability of Mo to clovers to increase N fixation23. Hydrogen ions and organic acids released by roots acidify rhizosphere soil. One effect of this is to decrease soil redox potential, reducing oxidized materials and increasing the solubility of Fe and Mn24. Phytosiderophore exudation from grass roots is part of a rhizosphere priming effect that stimulates organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling25,26. The uptake of K is mainly determined by the characteristics of the root system and root exudates27 but also involves Ca2+ and other secondary messengers18. The production of root exudates can be a response to environmental stress, including nutrient stress26. Magnesium improves nitrogen use efficiency, although basic research on Mg nutrition is lacking28. Exudates released by grasses are known to enhance the activity of soil microorganisms that accelerate the oxidation of S, allowing more available forms of S to be utilized by plants. Microorganisms play a major role in sulfur oxidation in soil, such as by mineralizing organic S2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Clearly, mechanistic explanations are complex and require more detailed study.

In terms of the complementarity of species, there is an obvious advantage to a plant of acquiring a limiting soil resource at reduced metabolic cost16. Clovers acquired higher concentrations and quantities of all nutrients (apart from Ni and Mo) than grasses. Grasses were better than clovers at procuring Mo from soil, even though the Mo requirement of clovers is likely to be greater22. Molybdate is the predominant form of Mo available to plants, but there is little knowledge of how plants access molybdate from the soil solution and redistribute it within the plant. We know that its availability is strongly dependent on soil pH and organic compounds in soil colloids30. Furthermore, phytosiderophore release by grass roots that occurs under Fe, Zn, Mn and Cu deficiencies is thought to be an adaptive response to enhance the acquisition of micronutrient metals31,32. We speculate that there are important mutually beneficial rhizosphere interactions between grasses and clovers within which Mo is likely to play a key role. More nitrogen was procured by clovers, but not grasses, when clovers were growing in mixture. An explanation for this may be that the growth cycle of grasses was already advanced at the onset of the experimental work. The grasses were not in an early stage of seasonal growth and may have had limited demand for N. This was also our best explanation for the failure of a selective herbicide to kill the grasses.

Our hypothesis that clovers benefit from the presence of grasses is supported by the fact that clover had higher foliage concentrations of the major nutrients N, P, K and S when growing in combination with grasses, procuring significantly larger quantities of P, S and Fe from soil than when either were growing alone. The latter is a combination of improved plant nutrition and higher yields. Many earlier studies have shown that mixed plant assemblages result in higher overall plant biomass33 and extract more nutrients from the soil than monocultures34. This is generally explained by better spatial exploitation of the soil by different root architectures35,36. The present findings indicate more positive mutually beneficial interactions most likely involving a rhizosphere priming effect26,37 of grasses that benefits clovers. This study reports the nutritional benefits of mixed communities of grasses and clovers in a field situation, showing that grasses enhance the ability of clovers to procure limiting plant nutrients. Chemical communication that has evolved in the rhizosphere of mixed plant communities is poorly understood, even in the context of the nitrogen cycle38. The findings of the present study show that grasses provide an advantage by enhancing N fixation by clovers, also increasing the mobility and uptake of other major nutrients and trace elements. Recognized deficiencies of P, S, Mg, B, Mo and Ni in these soils, to a significant extent, are mitigated by rhizosphere interactions that occur between grasses and clovers. This plays an important role in the interplay of key elements that are modified by and modify the physicochemistry of soil, nutrient lability and plant uptake.

Enhanced exploitation of soil chemistry probably has wider relevance to other low-input forms of agriculture22 and to providing research pathways to build science-based evidence relating to regenerative agriculture39. We conclude that more attention is required towards enhancing diversity rather than attempting to simplify species assemblages in grassland pastures. Clovers and grasses have different, complementary functional roles. Advancing this knowledge through further research could also help optimize the use of fertilizer amendments in pasture farming systems. We suggest that future work could identify root exudates of monocot and dicot combinations using rhizoboxes fitted with suction cups; the deployment of planar optodes in such rhizoboxes may reveal the spatial locations of root interactions. This knowledge may be used to determine optimal plant species combinations for pasture management. Our findings in this paper support other studies that have argued that maintaining and re-establishing plant diversity could be a way to manage temperate grasslands40 towards sustainable intensification41 as well as to combat grassland degradation42.

Methods

Study site

Soil cores were extracted from a 1,607 ha high country sheep farm (Mt Grand Station) situated in Hawea, Central Otago, on South Island, which has a continental-type climate of hot, dry summers and cold winters10. The soils are derived primarily from metamorphic schists and loess and are defined as Pallic Yellow Grey Earths. They are acidic (typically pH 5.5) with lower concentrations of P, S, B, Mo and Ni than typical soils elsewhere in New Zealand (Supplementary Table 1). They are also deficient in Na, which is an essential element for stock but not for plants. Annual rainfall is 703 mm with high annual and seasonal variability5. The station supports <2 stock units of sheep per ha that probably harvest <3 t of dry matter per ha across the whole landscape (D. Lucas, personal communication).

The sampling location was an approximately 400 m2 area of mixed grass–legume pasture on a mid-altitude (700 m), north-facing (sunny aspect), moderately steep (20–30°) hillside slope within a 65 ha grazed pasture block. White clover (Trifolium repens L.) and subterranean clover (T. subterraneum L.) have been periodically sown at this location, but the vegetation has a larger component of adventive and naturalized grasses and forbs; in an earlier study of the same sampling area, Maxwell et al.5 identified 4 other species of clovers, 11 species of grasses and 4 other forb species. There is also a very small component of native grasses (Rytidosperma spp.). The sampling area is largely below the altitude and too heavily grazed for native tussocks to form a significant component of the vegetation, although remnants of one lower-altitude tussock grass (Poa cita) and a native woody shrub (Discaria toumatou) are established in patches adjacent to the sampling location.

Experimental procedure

A total of 202 cores were randomly collected (10 cm in diameter, 15 cm deep, 1.2 l) using a soil corer in the spring month of September when sward height was approximately 3–5 cm. The core samples were inserted into polythene sleeves of slightly larger dimensions (15 cm in diameter, 20 cm deep, 3.5 l). The gap surrounding the cores was packed with perlite, and they were then transferred into a growth chamber set as near as possible to the current day/night temperatures, sunlight hours and light intensity recorded at the same time of year at Mt Grand. The environmental conditions in the chamber were modified with time accordingly. Soil moisture was carefully maintained in the microcosms by regular watering in equal amounts to prevent the cores from either drying out or becoming saturated: approximately 20 ml of water was added twice weekly during a three-month period. We considered this deviation from field conditions to be justified to maintain plant growth and nutrient mobility in soil and plants during the experimental period.

Cores selected for the experimental work were those that contained approximately equal amounts of grasses and clovers. The experimental cores were then further selected and grouped in accordance with the objectives of the three experiments. At the outset, the vegetation in all cores was clipped to 2 cm above the soil surface. Three separate experiments were designed as follows:

-

(1)

pH and nutrient mobility. Soil pH was measured in every core using a surface probe attached to a HANNA HI 99121 pH meter for surface pH. The cores were then divided into a range of six pH intervals: 4.5–4.99 (n = 10), 5.0–5.49 (n = 61), 5.5–5.99 (n = 52), 6.0–6.49 (n = 33), 6.5–6.99 (n = 34) and >7.0 (n = 12). Five replicates were collected from each of the six pH ranges. Soil pore water rhizon samplers (5 cm porous samplers with female luers, Rhizosphere Research Products) were inserted into three cores randomly selected at each pH interval. They were positioned diagonally at approximately 20° to sample pore water between depths of 5 and 10 cm. Soil pore water was then collected after one month in the growth chamber. Aboveground vegetation was harvested from the cores by hand clipping to 2 cm after three months in January, then dried and weighed. Nutrients were analysed separately in the foliage of grasses and clovers, each bulk sampled from each core.

-

(2)

Grasses and the nutrient content of clovers. A further 30 cores were selected within the pH range 5.2–5.7. Either grasses or clovers were selectively removed from ten cores each. Both a selective herbicide and careful hand removal were tested in a preliminary trial, before settling on the latter. The additional ten cores were left with a mixture of grasses and clovers; we selected those with an approximately equal ratio of clovers and grass. Five soil pore water rhizon samplers were inserted as above into the cores of each treatment. Harvest and analyses followed those described above.

-

(3)

Amendment of soil fertility. One of four nutrients (P, S, Mn and Mo) was added to the microcosms at approximately standard rates of fertilizer application that would typically be used in the hill country. Salts of each element (0.58 g (NH4) H2PO4, 513 kg ha−1; 0.0037 g Na2MoO4·2H2O, 3.3 kg ha−1; 0.6 g MnSO4·3H2O, 530 kg ha−1; and 0.15 g S, 135.4 kg ha−1) were dissolved in 10 ml of water. Pots with similar pH values (range 5.7–6.7) and comparable ratios of legumes and grass were selected, and herbage was clipped at 2 cm before the nutrients were added. Yield was measured twice, at two-month intervals.

Analytical procedure

The soil and plant samples were dried at 25 °C/65 °C and ground (2 mm), then prepared for analysis by Analytical Services at Lincoln University and RJ Hill Laboratories Limited, Hamilton, following the standard procedures, and N was determined using an Elementar Rapid Max N Elemental Analyser. The other elements in plant and water samples were determined using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry facility at Canterbury University. Nutrients in foliage are expressed in terms of both foliage concentrations (mg kg−1) and mass balance (concentration × dry weight of foliage). For statistical analysis, data not normally distributed were log-transformed before analysis. Differences between means were determined using one-way ANOVA, with a post-hoc Fisher’s least significant difference test. All analyses were conducted using Minitab Statistical Software (Minitab, LLC), v.19.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are available through https://data.lincoln.ac.nz/. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Agricultural and Horticultural Land Use (StatsNZ, 2021); https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/agricultural-and-horticultural-land-use

Thom, E. R. Hill Country Symposium Grassland Research and Practice Series No. 16 (New Zealand Grassland Association, 2016).

Wardle, P. Vegetation of New Zealand (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991).

Maxwell, T. M. R., Moir, J. L. & Edwards, G. R. Grazing and soil fertility effect on naturalized annual clover species in New Zealand high country. Rangel. Ecol. Manage. 69, 444–448 (2016).

Maxwell, T., Moir, J. & Edwards, G. Influence of environmental factors on the abundance of naturalised annual clovers in the South Island hill and high country. J. N. Z. Grassl. 72, 165–170 (2010).

Nölke, I., Tonn, B., Komainda, M., Heshmati, S. & Isselstein, J. The choice of the white clover population alters overyielding of mixtures with perennial ryegrass and chicory and underlying processes. Sci. Rep. 12, 1155 (2022).

Fay, P. A. et al. Grassland productivity limited by multiple nutrients. Nat. Plants 1, 15080 (2015).

Zhang, W., Maxwell, T. M. R., Robinson, B. & Dickinson, N. Legume nutrition is improved by neighbouring grasses. Plant Soil (in the press).

Smith, S. E. & Read, D. J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (Academic Press, 2008)

Phoenix, G. K., Johnson, D. A., Muddimer, S. P., Leake, J. R. & Cameron, D. D. Niche differentiation and plasticity in soil phosphorus acquisition among co-occurring plants. Nat. Plants 6, 349–354 (2020).

Lambers, H., Clements, J. C. & Nelson, M. N. How a phosphorus-acquisition strategy based on carboxylate exudation powers the success and agronomic potential of lupines (Lupinus, Fabaceae). Am. J. Bot. 100, 263–288 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Long-term increased grain yield and soil fertility from intercropping. Nat. Sustain. 4, 943–950 (2021).

Homulle, Z., George, T. & Karley, A. Root traits with team benefits: understanding belowground interactions in intercropping systems. Plant Soil 471, 1–26 (2021).

Burrows, C. J. Processes of Vegetation Change (Unwin Hyman, 1990).

Fornara, D. & Tilman, D. Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation. J. Ecol. 96, 314–322 (2008).

Lynch, J. P., Strock, C. F., Schneider, H. M., Sidhu, J. S. & Ajmera, I. Root anatomy and soil resource capture. Plant Soil 466, 21–63 (2021).

Lambers, H., Wright, I. J., Caio, G. & Pereira, P. J. Leaf manganese concentrations as a tool to assess belowground plant functioning in phosphorus-impoverished environments. Plant Soil 461, 43–61 (2021).

Liu, G. & Martinoia, E. How to survive on low potassium. Nat. Plants 6, 332–333 (2020).

Anke, M. & Seifert, M. The biological and toxicological importance of molybdenum in the environment and in the nutrition of plants, animals and man. Part 1: molybdenum in plants. Acta Biol. Hung. 58, 311–324 (2007).

Gylfadóttir, T., Helgadóttir, Á. & Høgh-Jensen, H. Consequences of including adapted white clover in northern European grassland: transfer and deposition of nitrogen. Plant Soil 297, 93–104 (2007).

Maxwell, T. M. L. R. Ecology and Management of Adventive Annual Clover Species in the South Island Hill and High Country of New Zealand. PhD thesis, Lincoln Univ. (2013).

Li, C. et al. Syndromes of production in intercropping impact yield gains. Nat. Plants 6, 653–660 (2020).

McLaren, R. G. & Cameron, K. C. Soil Science: Sustainable Production and Environmental Science (Oxford Univ. Press, 1996).

Chang, X., Duan, C. & Wang, H. Root excretion and plant resistance to metal toxicity. J. Appl. Ecol. 11, 315–320 (2000).

Puschenreiter, M., Gruber, B. & Wenzel, W. W. Phytosiderophore-induced mobilization and uptake of Cd, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb and Zn by wheat plants grown on metal-enriched soils. Environ. Exp. Bot. 138, 67–76 (2017).

Lu, J. Y. et al. Rhizosphere priming effects of Lolium perenne and Trifolium repens depend on phosphorus fertilization and biological nitrogen fixation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 150, 108805 (2020).

Wang, L., Chen, F. & Wan, K. Y. Research progress and prospects of plant growth efficiency and its evaluation. Soils 42, 164–170 (2010).

Tian, X. Y. et al. Physiological and molecular advances in magnesium nutrition of plants. Plant Soil 468, 1–17 (2021).

Wainwright, M. Sulfur oxidation in soils. Adv. Agron. 37, 349–376 (1984).

Kaiser, B. N., Gridley, K. L., Ngaire Brady, J., Phillips, T. & Tyerman, S. D. The role of molybdenum in agricultural plant production. Ann. Bot. 96, 745–754 (2005).

Khobra, R. & Singh, B. Phytosiderophore release in relation to multiple micronutrient metal deficiency in wheat. J. Plant Nutr. 41, 679–688 (2018).

Erenoglu, B., Eker, S., Cakmak, I., Derici, R. & Römheld, V. Effect of iron and zinc deficiency on release of phytosiderophores in barley cultivars differing in zinc efficiency. J. Plant Nutr. 23, 1645–1656 (2000).

Chen, C., Chaudhary, A. & Mathys, A. Nutritional and environmental losses embedded in global food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 160, 104912 (2020).

Nyfeler, D., Huguenin-Elie, O., Suter, M., Frossard, E. & Lüscher, A. Grass–legume mixtures can yield more nitrogen than legume pure stands due to mutual stimulation of nitrogen uptake from symbiotic and non-symbiotic sources. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 140, 155–163 (2011).

Zhang, C., Postma, J. A., York, L. M. & Lynch, J. P. Root foraging elicits niche complementarity-dependent yield advantage in the ancient ‘three sisters’ (maize/bean/squash) polyculture. Ann. Bot. 114, 1719–1733 (2014).

Ghestem, M., Sidle, R. C. & Stokes, A. The influence of plant root systems on subsurface flow: implications for slope stability. BioScience 61, 869–879 (2011).

Huo, C., Luo, Y. & Cheng, W. Rhizosphere priming effect: a meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 111, 78–84 (2017).

Coskun, D., Britto, D. T., Shi, W. & Kronzucker, H. J. How plant root exudates shape the nitrogen cycle. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 661–673 (2017).

Grelet, G. et.al. Regenerative Agriculture in Aotearoa New Zealand: Research Pathways to Build Science-Based Evidence and National Narratives (Landcare Research New Zealand, 2021).

Sergei Schaub, R. F. et al. Plant diversity effects on forage quality, yield and revenues of semi-natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 11, 768 (2020).

Brooker, R. W. et al. Improving intercropping: a synthesis of research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. N. Phytol. 206, 107–117 (2015).

Bardgett, R. D. et al. Combatting global grassland degradation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 720–735 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research team are grateful to the Miss E. L. Hellaby Indigenous Grasslands Research Trust for grant funding to support Z.W. for his PhD stipend and operational funds. Special thanks also to S. Stephen, B. Richards, E. Huang, L. Hassall and R. Cresswell for practical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the planning and execution of the project and to manuscript preparation. Z.W. carried out the practical work and data analysis as part of his PhD programme supervised by N.D., T.M. and B.R. N.D. and Z.W. are responsible for the final manuscript draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Rafael Clemente, Chris Anderson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Supplementary Data 1

Data for Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Data 2

Data for Supplementary Fig. 2.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Processed data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Processed data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Processed data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Processed data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Processed data for Fig. 5.

Source Data Fig. 6

Processed data for Fig. 6.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Z., Maxwell, T., Robinson, B. et al. Grasses procure key soil nutrients for clovers. Nat. Plants 8, 923–929 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01210-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-022-01210-1

This article is cited by

-

Rice varietal intercropping mediates resistance to rice blast (Magnaporthe Oryzae) through core root exudates

BMC Plant Biology (2025)

-

Legume content estimation from UAV image in grass-legume meadows: comparison methods based on the UAV coverage vs. field biomass

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Invasive weed disrupts facilitation of nutrient uptake in grass-clover assemblage

Soil Ecology Letters (2024)

-

Companion species mitigate nutrient constraints in high country grasslands in New Zealand

Plant and Soil (2023)