Abstract

Auxin, as a vital phytohormone, is enriched in the vascular cambium, playing a crucial role in regulating wood formation in trees. While auxin’s influence on cambial stem cells is well established, the molecular mechanisms underlying the auxin-directed development of cambial derivatives, such as wood fibres, remain elusive in forest trees. Here we identified a transcription factor, AINTEGUMENTA-like 5 (AIL5)/PLETHORA 5 (PLT5) from Populus tomentosa, that is specifically activated by auxin signalling within the vascular cambium. PLT5 regulated both cell expansion and cell wall thickening in wood fibres. Genetic analysis demonstrated that PLT5 is essential for mediating the action of auxin signalling on wood fibre development. Remarkably, PLT5 specifically inhibits the onset of fibre cell wall thickening by directly repressing SECONDARY WALL-ASSOCIATED NAC DOMAIN 1 (SND1) genes. Our findings reveal a sophisticated auxin–PLT5 signalling pathway that finely tunes the development of wood fibres by controlling cell wall thickening.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. The GenBank accession numbers of the P. tomentosa genes are as follows: PLT5a (OR250663), PLT5b (OR250664), IAA9 (MH345700), ARF5.1 (MH352401), SND1-A1 (OR514110) and UBQ (PQ155116). The AspWood datasets are available in the supplementary data of ref. 39 (https://academic.oup.com/plcell/article/29/7/1585/6099151). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

van Dam, J. E. G. & Gorshkova, T. A. in Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences (ed. Thomas, B.) 87–96 (Elsevier, 2003).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320, 1444–1449 (2008).

Ragauskas, A. J. et al. The path forward for biofuels and biomaterials. Science 311, 484–489 (2006).

Fukuda, H. Signals that control plant vascular cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 379–391 (2004).

Esau, K. Vascular Differentiation in Plants (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1965).

Larson, P. R. The Vascular Cambium: Development and Structure (Springer-Verlag, 1994).

Turner, S., Gallois, P. & Brown, D. Tracheary element differentiation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 407–433 (2007).

Gray-Mitsumune, M. et al. Expansins abundant in secondary xylem belong to subgroup A of the alpha-expansin gene family. Plant Physiol. 135, 1552–1564 (2004).

Majda, M. et al. Elongation of wood fibers combines features of diffuse and tip growth. New Phytol. 232, 673–691 (2021).

van Leeuwen, M. et al. Assessment of standing wood and fiber quality using ground and airborne laser scanning: a review. For. Ecol. Manage. 261, 1467–1478 (2011).

Dubey, N., Purohit, R. & Mohit, H. in Wood Polymer Composites: Recent Advancements and Applications (eds Mavinkere Rangappa, S. et al.) 137–160 (Springer, 2021).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Snd1 transcription factor-directed quantitative functional hierarchical genetic regulatory network in wood formation in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell 25, 4324–4341 (2013).

Chen, H. et al. Hierarchical transcription factor and chromatin binding network for wood formation in black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa). Plant Cell 31, 602–626 (2019).

Zhong, R., Lee, C. & Ye, Z. H. Functional characterization of poplar wood-associated NAC domain transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 152, 1044–1055 (2010).

Ohtani, M. et al. A NAC domain protein family contributing to the regulation of wood formation in poplar. Plant J. 67, 499–512 (2011).

Zhong, R., McCarthy, R. L., Lee, C. & Ye, Z. H. Dissection of the transcriptional program regulating secondary wall biosynthesis during wood formation in poplar. Plant Physiol. 157, 1452–1468 (2011).

Zhao, Y., Sun, J., Xu, P., Zhang, R. & Li, L. Intron-mediated alternative splicing of wood-associated NAC transcription factor1b regulates cell wall thickening during fiber development in populus species. Plant Physiol. 164, 765–776 (2014).

Takata, N. et al. Populus Nst/Snd orthologs are key regulators of secondary cell wall formation in wood fibers, phloem fibers and xylem ray parenchyma cells. Tree Physiol. 39, 514–525 (2019).

Luo, L. & Li, L. Molecular understanding of wood formation in trees. For. Res. 2, 5 (2022).

Sundberg, B., Uggla, C. & Tuominen, H. in Cell and Molecular Biology of Wood Formation (eds Savidge, R. et al.) 169–188 (BIOS Scientific Publishers, 2000).

Snow, R. Activation of cambial growth by pure hormones. New Phytol. 34, 347–360 (1935).

Gouwentak, C. A. Cambial activity as dependent on the presence of growth hormone and the non-resting condition of stems. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 44, 654–663 (1941).

Tuominen, H., Puech, L., Fink, S. & Sundberg, B. A radial concentration gradient of indole-3-acetic acid is related to secondary xylem development in hybrid aspen. Plant Physiol. 115, 577–585 (1997).

Uggla, C., Mellerowicz, E. J. & Sundberg, B. Indole-3-acetic acid controls cambial growth in Scots pine by positional signaling. Plant Physiol. 117, 113–121 (1998).

Spicer, R., Tisdale-Orr, T. & Talavera, C. Auxin-responsive Dr5 promoter coupled with transport assays suggest separate but linked routes of auxin transport during woody stem development in Populus. PLoS ONE 8, e72499 (2013).

Uggla, C., Moritz, T., Sandberg, G. & Sundberg, B. Auxin as a positional signal in pattern formation in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9282–9286 (1996).

Bhalerao, R. & Fischer, U. Auxin gradients across wood – instructive or incidental? Physiol. Plant. 151, 43–51 (2014).

Brackmann, K. et al. Spatial specificity of auxin responses coordinates wood formation. Nat. Commun. 9, 875 (2018).

Han, S. et al. Bil1-mediated Mp phosphorylation integrates Pxy and cytokinin signalling in secondary growth. Nat. Plants 4, 605–614 (2018).

Shi, D., Lebovka, I., Lopez-Salmeron, V., Sanchez, P. & Greb, T. Bifacial cambium stem cells generate xylem and phloem during radial plant growth. Development 146, dev171355 (2019).

Smetana, O. et al. High levels of auxin signalling define the stem-cell organizer of the vascular cambium. Nature 565, 485–489 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Auxin response Factor7 integrates gibberellin and auxin signaling via interactions between Della and Aux/Iaa proteins to regulate cambial activity in poplar. Plant Cell 34, 2688–2707 (2022).

Makila, R. et al. Gibberellins promote polar auxin transport to regulate stem cell fate decisions in cambium. Nat. Plants 9, 631–644 (2023).

Nilsson, J. et al. Dissecting the molecular basis of the regulation of wood formation by auxin in hybrid aspen. Plant Cell 20, 843–855 (2008).

Xu, C. et al. Auxin-mediated Aux/Iaa-Arf-Hb signaling cascade regulates secondary xylem development in Populus. New Phytol. 222, 752–767 (2019).

Zheng, S. et al. Two MADS-box genes regulate vascular cambium activity and secondary growth by modulating auxin homeostasis in Populus. Plant Commun. 2, 100134 (2021).

Kucukoglu, M., Nilsson, J., Zheng, B., Chaabouni, S. & Nilsson, O. Wuschel-related Homeobox4 (Wox4)-like genes regulate cambial cell division activity and secondary growth in Populus trees. New Phytol. 215, 642–657 (2017).

Dai, X. et al. Cell-type-specific Ptrwox4a and Ptrvcs2 form a regulatory nexus with a histone modification system for stem cambium development in Populus trichocarpa. Nat. Plants 9, 96–111 (2023).

Sundell, D. et al. Aspwood: high-spatial-resolution transcriptome profiles reveal uncharacterized modularity of wood formation in Populus tremula. Plant Cell 29, 1585–1604 (2017).

Aida, M. et al. The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119, 109–120 (2004).

Galinha, C. et al. PLETHORA proteins as dose-dependent master regulators of Arabidopsis root development. Nature 449, 1053–1057 (2007).

Mahonen, A. P. et al. PLETHORA gradient formation mechanism separates auxin responses. Nature 515, 125–129 (2014).

Roszak, P. et al. Cell-by-cell dissection of phloem development links a maturation gradient to cell specialization. Science 374, eaba5531 (2021).

Crawford, K. M. & Zambryski, P. C. Plasmodesmata signaling: many roles, sophisticated statutes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 382–387 (1999).

Crawford, K. M. & Zambryski, P. C. Non-targeted and targeted protein movement through plasmodesmata in leaves in different developmental and physiological states. Plant Physiol. 125, 1802–1812 (2001).

Wu, X. et al. Modes of intercellular transcription factor movement in the Arabidopsis apex. Development 130, 3735–3745 (2003).

Yadav, R. K. et al. Wuschel protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Genes Dev. 25, 2025–2030 (2011).

Zhou, J., Wang, X., Lee, J. Y. & Lee, J. Y. Cell-to-cell movement of two interacting at-hook factors in Arabidopsis root vascular tissue patterning. Plant Cell 25, 187–201 (2013).

Nole-Wilson, S. & Krizek, B. A. DNA binding properties of the Arabidopsis floral development protein aintegumenta. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 4076–4082 (2000).

Yano, R. et al. CHOTTO1, a putative double APETALA2 repeat transcription factor, is involved in abscisic acid-mediated repression of gibberellin biosynthesis during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 151, 641–654 (2009).

Teale, W. D., Paponov, I. A. & Palme, K. Auxin in action: signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 847–859 (2006).

Vanneste, S. & Friml, J. Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell 136, 1005–1016 (2009).

Pinon, V., Prasad, K., Grigg, S. P., Sanchez-Perez, G. F. & Scheres, B. Local auxin biosynthesis regulation by PLETHORA transcription factors controls phyllotaxis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1107–1112 (2013).

Du, Y. & Scheres, B. PLETHORA transcription factors orchestrate de novo organ patterning during Arabidopsis lateral root outgrowth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11709–11714 (2017).

Lee, K. H., Du, Q., Zhuo, C., Qi, L. & Wang, H. Lbd29-involved auxin signaling represses NAC master regulators and fiber wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 181, 595–608 (2019).

Johnsson, C. et al. The plant hormone auxin directs timing of xylem development by inhibition of secondary cell wall deposition through repression of secondary wall NAC-domain transcription factors. Physiol. Plant. 165, 673–689 (2019).

Lloyd, G. & Mccown, B. H. Commercially-feasible micropropagation of mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, by use of shoot-tip culture. Comb. Proc. Int. Plant Prop. Soc. 30, 421–427 (1980).

Fu, X. et al. Cytokinin signaling localized in phloem noncell-autonomously regulates cambial activity during secondary growth of Populus stems. New Phytol. 230, 1476–1488 (2021).

Jia, Z., Sun, Y., Yuan, L., Tian, Q. & Luo, K. The chitinase gene (Bbchit1) from Beauveria bassiana enhances resistance to Cytospora chrysosperma in Populus tomentosa Carr. Biotechnol. Lett. 32, 1325–1332 (2010).

Ma, X. et al. A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol. Plant 8, 1274–1284 (2015).

Fan, D. et al. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis in Populus in the first generation. Sci Rep. 5, 12217 (2015).

Xie, X. et al. CRISPR-Ge: a convenient software toolkit for crispr-based genome editing. Mol. Plant 10, 1246–1249 (2017).

Engler, C., Gruetzner, R., Kandzia, R. & Marillonnet, S. Golden gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS ONE 4, e5553 (2009).

Zhu, Q. L., Yang, Z. F., Zhang, Q. Y., Chen, L. T. & Liu, Y. G. Robust multi-type plasmid modifications based on isothermal in vitro recombination. Gene 548, 39–42 (2014).

Liu, Q. et al. Hi-TOM: a platform for high-throughput tracking of mutations induced by CRISPR/Cas systems. Sci. China Life Sci. 62, 1–7 (2019).

Sang, X. C. et al. CHIMERIC FLORAL ORGANS1, encoding a monocot-specific MADS box protein, regulates floral organ identity in rice. Plant Physiol. 160, 788–807 (2012).

Yang, H. et al. A companion cell-dominant and developmentally regulated H3k4 demethylase controls flowering time in Arabidopsis via the repression of FLC expression. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002664 (2012).

Hellens, R. P. et al. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1, 13 (2005).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. Mega7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Fu, L. et al. How trees allocate carbon for optimal growth: insight from a game-theoretic model. Brief. Bioinform. 19, 593–602 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank V. L. Chiang and W. Li (Northeast Forestry University, China), H. Lu (Beijing Forestry University, China), and Y. Zhang (Southwest University, China) for helpful comments. This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFD2200204 to K.L.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271906 to C.X. and 32201579 to X.F.) and the Opening Project of State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding (K2022102 to C.X.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.X. and K.L. conceived the research and designed the experiments. S.L., X.F., Y.W., X.D., L. Luo, D.C., C.L. and J.H. performed the experiments. C.X., S.L. and X.F. analysed the data. C.F. and R.W. conducted the modelling and contributed to the statistical analysis. C.X. and K.L. prepared the manuscript. L. Li contributed to the revision of the manuscript and provided valuable comments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Yka Helariutta and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

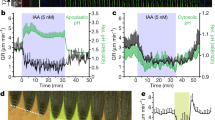

Extended Data Fig. 1 Phenotypes of secondary xylem, DF cell layers and wood fibres in WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics.

a, Quantification of secondary xylem cell layer number at the 7th, 8th and 9th internodes of 3-month-old WT and WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics (#2 and #3). b, c, Observation (b) and quantification (c) of DF phenotypes on the cross-sections of the 8th internodes of 3-month-old WT and WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics (#2 and #3). d, percentage of DF cell layer number compared to the total number of secondary xylem cell layers. e, Cellular morphology of fibres isolated from the 10th internodes of 3-month-old WT and WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics (#2 and #3). In b and e, cross-sections (b) and fibre cells (e) were stained with toluidine blue. In b, the DSX domains are indicated in yellow. In a and c, cell layer measurements for secondary xylem (a) and DF (c) were obtained from 10 radial cell files in cross-sections of the 7th, 8th and 9th internodes. In d, the percentage was calculated from the data of total secondary xylem cell layer number (a) and DF cell layer number (c). Each biological replicate included 5 cross-sections, with 6 biological replicates (independent plants) analyzed for WT and each transgenic line. The data for all 30 cross-sections across 6 replicates are shown in boxes and whisker plots, with boxes indicating the median and 5th to 95th percentile, and whiskers representing the data range excluding outliers. One-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett test for pairwise comparison was performed to evaluate significant differences between WT and transgenic lines. The average values of 5 cross-sections from a biological replicate were used for statistical analyses (n = 6). **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. VC: vascular cambium; Ph: phloem; SXy: secondary xylem. Scale bars: 30 μm (b) and 100 μm (e).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Identification of PLT5a and PLT5b genes from the transcriptome datasets of IAA9m-overexpressing P. tomentosa lines.

a, Network diagram of the genes that are repressed by IAA9m overexpression and specifically expressed in vascular cambium. Transcriptome data of 35Spro:IAA9m are sourced from our previous study35. The data of genes specifically expressed in vascular cambium are from AspWood database39. The network is constructed with Gephi software. Ca, cambium; Down, down-regulated genes by IAA9m overexpression. The numbers in the diagram represent the number of genes in different clusters. b, Enrichment of GO terms of the genes that are down-regulated by IAA9m overexpression and specifically expressed in vascular cambium. c, Venn diagram of the transcription factors (TFs) that are down-regulated by IAA9m overexpression and specifically expressed in vascular cambium versus those identified as vascular cambium-specific (VCS) TFs38. d, The families of 15 identified vascular cambium specific TFs that are responsive to auxin. The number of identified members from each family is indicated. e, The phylogenetic analysis of PLT proteins from Arabidopsis and poplar. The PLT5 homologs are indicated in red. In (b), the Chi-square test of independence is employed to evaluate the significance of difference between the expected frequencies of genes annotated with GO terms and their observed frequencies.

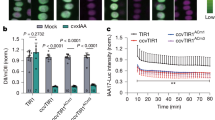

Extended Data Fig. 3 ARF5 directly targets PLT5a to activate its expression.

a, Distribution of predicted auxin response factor (ARF) TF-binding sites within the promoter of PLT5a and ChIP-qPCR analyses. b, The binding capacity of ARF5.1 protein to the PLT5a promoter fragment (PLT5apro-III) examined by EMSA assays. c, Luciferase-based effector-reporter assays of ARF5.1-activated PLT5a expression in transiently transfected tobacco leaf cells. d, Quantification of luciferase activities. In c and d, PLT5apro-Im and PLT5apro-IIIm indicate the promoter regions of PLT5a with impaired binding sites of ARF5.1 proteins generated by site-directed mutagenesis. In a and d, data are shown as mean ± S.D.; dots represent the values from independent biological replicates (n = 3). Student’s t-test (two-tailed) was performed to evaluate significant differences. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. In b, the experiments were repeated independently three times, with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Phenotypes of DF cell layers and wood fibres caused by plt5a plt5b double mutations and WOX4apro:PLT5a transgene.

a, Anatomical sections of the 7th, 8th and 9th internodes of 3-month-old WT, plt5a plt5b mutants (#4 and #5) and WOX4apro:PLT5a transgenics (#1 and #2). b, Quantification of DF cell layer number at the 7th, 8th and 9th internodes of WT, mutant and transgenic lines corresponding to (a). c, Cellular morphology of fibres isolated from the 10th internodes of 3-month-old WT, plt5a plt5b mutants (#4 and #5) and WOX4apro:PLT5a transgenics (#1 and #2). d and e, The length (d) and width (e) of fibres isolated from the 10th internodes of WT, mutant and transgenic lines corresponding to (c). In a and c, cross-sections (a) and fibre cells (c) were stained with toluidine blue. In a, DSX domains are indicated in yellow. In b, average values for DF cell layers were determined from 10 radial cell files from cross-sections of the 7th, 8th and 9th internodes, with 5 cross-sections per biological replicate. Date from 6 biological replicates (independent plants) were analyzed, encompassing 30 cross-sections in total. Boxes and whisker plots represent these values. In d and e, 25 fibre cells isolated were quantified for each biological replicate. Six biological replicates (independent plants). The values from all 150 fibre cells from 6 biological replicates were included in box and whisker plots. In b, d and e, boxes show the median and 5th to 95th percentile, and whiskers represent the value range excluding outliers. One-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett test for pairwise comparison was performed to evaluate significant differences between WT and mutant or transgenic lines. The average values of 5 cross-sections (b) or 25 fibre cells (d, e) from a biological replicate were used for statistical analyses (n = 6). **, P < 0.01. DF, developing fibre; SXy, secondary xylem; VC, vascular cambium. Scale bars, 30 μm (a) and 100 μm (c).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cell wall thickness of developing fibres affected by PLT5.

a, SEM analyses of DF cell layers at the DSX domain of the 8th internodes from 3-month-old WT, plt5a plt5b mutants (#4 and #5) and WOX4apro:PLT5a transgenics (#1 and #2). b, SEM analyses of developing fibre cells at the DSX domain of the 8th internodes from 3-month-old WT and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP (#1) and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP×3 (#1) transgenics. c, Quantification of cell wall thickness of the 1st to 5th DF cell layers at the DSX domain of WT and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP×3 (#1) transgenics. d, SEM analyses of DF cell layers at the DSX domain of the 8th internodes from 3-month-old WT and WOX4apro:IAA9m (#3), PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP > > WOX4apro:IAA9m (#1) and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP×3 > >WOX4apro:IAA9m (#2) transgenics. In c, cell wall thickness between neighboring DF cell layers was measured in 10 radial cell files per biological replicate. Data from 6 biological replicates (independent plants) for WT and transgenic lines were analyzed, including 60 radial cell files in total. Boxes represent the median and 5th to 95th percentile, while whisker plots indicate the range excluding outliers. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test for pairwise comparison was used to assess differences between WT and transgenic lines. Average values from 10 radial cell files per replicate were used for statistical analysis (n = 6). n.s., not significant. The numbers in red (a, b and d) indicate the developing fibre cell layers. CW, cell wall. Scale bars: 15 μm (a), (b) and (d).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Morphology and length distribution of fibre cells in different developmental classes for plt5a plt5b and WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics.

a and b, cellular morphology (a) and length quantification (b) of fibre cells isolated from the 10th internodes of 3-month-old WT, plt5a plt5b mutants and WOX4apro:IAA9m transgenics classified into four categories. In a, fibres were stained with toluidine blue. In b, the length of isolated fibres was measured using ImageJ software. A total of 72 fibre cells from 3 biological replicates (independent plants) were measured. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Scale bars, 100 μm (a).

Extended Data Fig. 7 The fitness of growth equation to the cell wall thickness that changes with increasing fibre cell layers.

a and b, The fitness of growth equation to cell wall thickness that changes with increasing fibre cell layers in the 8th internodes of plt5a plt5b (#4) mutants and WOX4apro:PLT5a (#1) transgenics (a) and WOX4apro:IAA9m (#3) and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP >>WOX4apro:IAA9m (#1) transgenics (b). Dots denote observations of cell wall thickness at different layers. The timing of inflection point tI is indicated in each case.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Expression levels of SND1 genes in IAA9m- and PLT5-associated transgenic lines assayed by qRT-PCR.

a and b, Expression levels of SND1-A1, SND1-A2, SND1-B1 and SND1-B2 in stems of WOX4pro:IAA9m transgenics (a), plt5a plt5b mutants, PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP and PLT5apro:PLT5a-YFP×3 transgenics (b). The 8th internodes of 3-month-old WT and transgenic lines were collected for RNA extraction followed by qRT-PCR assays. Data are shown as mean ± S.D. from 3 biological replicates (independent plants); n = 3. One-way ANOVA analysis followed by Dunnett test for pairwise comparison was performed to test significant differences among WT and mutant or transgenic lines. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 9 ChIP-qPCR and effector-reporter assays of PLT5-bindiing capacity to SND1-A2/B1/B2 promoters.

a, b and c, Distribution of predicted PLT5a-binding sites within the promoter of SND1-A2 (a), SND1-B1 (b) and SND1-B1 (c) and ChIP-qPCR analysis for the promoter of SND1-A2 (a), SND1-B1 (b) and SND1-B1 (c). d, f and h, Luciferase-based effector-reporter assays of PLT5a-suppressed SND1-A2 (d), SND1-B1 (f) and SND1-B2 (h) expression in transiently transfected tobacco leaf cells. e, g and i, Quantification of luciferase activity of PLT5a-suppressed SND1-A2 (e), SND1-B1 (g) and SND1-B2 (i) expression in transiently transfected tobacco leaf cells. In d to i, SND1-A2pro-Im, SND1-B1pro-Im and SND1-B1pro-IIm indicate the promoter regions of SND1-A2, SND1-B1 and SND1-B2 with impaired binding sites of PLT5a proteins generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Data are shown as mean ± S.D.; dots represent the values from independent biological replicates (n = 3). Student’s t-test (two-tailed) was performed to evaluate significant differences. **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Phenotypes of DSX and wood fibres caused by SND1-A1 and PLT5a-associated transgenes.

a, Anatomical sections of the 8th internodes of 3-month-old WT and 35Spro:SND1-A1 (#2), WOX4apro:PLT5a (#1) and 35Spro:SND1-A1 > > WOX4apro:PLT5a (#2) transgenics. b, Cellular morphology of fibres isolated from the 10th internodes of 3-month-old WT and 35Spro:SND1-A1 (#2), WOX4apro:PLT5a (#1) and 35Spro:SND1-A1 > > WOX4apro:PLT5a (#2) transgenics. c, d, The length (c) and width (d) of fibres isolated from the 10th internodes of WT and transgenic lines corresponding to (b). e, The percentages of four classes of fibres cells isolated from the 10th internodes of WT and transgenic lines corresponding to (b). f, SEM analyses of DF cell layers at the DSX domain of the 8th internodes from 3-month-old WT and 35Spro:SND1-A1 (#2), WOX4apro:PLT5a (#1) and 35Spro:SND1-A1 > > WOX4apro:PLT5a (#2) transgenics. In a and b, cross-sections (a) and isolated fibre cells (b) were stained with toluidine blue. In a, the DSX domains are indicated in yellow. In c and d, 25 fibre cells isolated from the 10th internodes were quantified for each biological replicate. Six biological replicates (independent plants) were analyzed for WT and transgenic lines. The box and whisker plots represent values from 150 fibre cells across 6 biological replicates, with boxes showing the median and 5th to 95th percentile, and whiskers indicating the range excluding outliers. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used to assess significant differences between WT and transgenic lines. Statistical analyses were based on the average values of 25 fibre cells per biological replicate (n = 6). **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; n.s., not significant. The numbers in red (f) indicate DF cell layers at DSX domain. DSX, developing secondary xylem; Ph, phloem; SXy, secondary xylem; VC, vascular cambium. Scale bars, 30 μm (a), 100 μm (b) and 15 μm (f).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–16.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Supplementary Data 1

Statistical source data for supplementary figures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Unprocessed gels.

Source Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed gels.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Fu, X., Wang, Y. et al. The auxin–PLETHORA 5 module regulates wood fibre development in Populus tomentosa. Nat. Plants 11, 580–594 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-01931-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-01931-z

This article is cited by

-

Declining wood density

Nature Plants (2025)