Abstract

Rice roots develop aerenchyma, which transports oxygen from shoots to roots, facilitating adaptation to waterlogged conditions. This oxygen oxidizes ferrous ions into ferric compounds, forming iron plaque that mitigates iron toxicity. However, the molecular mechanisms linking aerenchyma and iron plaque formation remain poorly understood. Here we identified a rice mutant (AZ1302) defective in both aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, with the causal mutation mapped to the PHYTOENE SYNTHASE 2 (OsPSY2) gene. CRISPR–Cas9-induced psy2 mutants exhibited reduced levels of carotenoid-derived hormones, strigolactones and abscisic acid, in roots. In psy2 mutants, exogenous application of strigolactones rescued aerenchyma formation, while abscisic acid restored iron plaque deposition, providing evidence for distinct hormonal regulatory functions in the two processes. These findings revise the current understanding by dissociating the roles of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, establishing a role for OsPSY2 in integrating hormonal signalling to drive root plasticity and offering new insights into plant adaptation under environmental stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a staple cereal crop that sustains over half of the global population, and its growth and productivity are highly sensitive to environmental fluctuations. The ability of rice roots to modify their architecture in response to stress, known as root plasticity, is essential for adapting to challenges such as nutrient imbalances1 and water availability extremes2. Rice roots adapt to environmental stress through vital mechanisms such as the formation of aerenchyma and the deposition of iron plaque. Deciphering the molecular mechanisms of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation could offer new strategies to enhance stress resilience and improve rice resilience in challenging agroecological conditions.

Most plants struggle to survive under waterlogged conditions due to oxygen deprivation and mineral toxicity. However, rice has evolved specialized root adaptations that allow it to thrive in waterlogged environments. One key adaptation is the formation of aerenchyma, a channel-like structure in the roots that facilitates oxygen transfer from the shoots to the roots, enabling tolerance of anoxic conditions3. Another critical adaptation is the oxidation of ferrous ions (Fe2+) at the root surface, thereby causing the formation of reddish-brown ferric compounds known as iron plaque. This iron plaque not only protects rice from iron toxicity by sequestering excess Fe2+ on the root surface4 but also plays a role in regulating nutrient availability5 and interactions with soil microbes6. These observations suggest a functional relationship between aerenchyma formation and iron plaque deposition, as aerenchyma enhances oxygen transport to the roots, which is essential for the oxidative processes leading to iron plaque formation7. Despite its importance, the specific role of aerenchyma in facilitating iron plaque formation remains speculative and poorly understood.

Aerenchyma formation is a constitutive feature of rice roots but can be enhanced by various environmental and physiological factors, including waterlogging8, hypoxia or ethylene9, and auxin signalling10. Ethylene activates respiratory burst oxidase homologue isoform H, which produces reactive oxygen species in the cortical cells11. When reactive oxygen species levels exceed the scavenging capacity of metallothioneins, programmed cell death occurs in cortical cells, leading to the creation of air spaces that form the aerenchyma12. The oxygen transported via aerenchyma to the root surface plays a pivotal role in oxidizing Fe2+ to Fe3+, driving the formation of iron plaque. However, despite extensive research on aerenchyma formation, its direct involvement in iron plaque deposition remains untested.

For this purpose, we investigate a mutagenized population of the indica cultivar IR64 and identify PHYTOENE SYNTHASE 2 (OsPSY2) as a key regulator of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in rice roots through genetic mapping of a mutant impaired in these traits. We demonstrate that OsPSY2 modulates the biosynthesis of strigolactones (SLs) and abscisic acid (ABA), which positively regulate aerenchyma formation and iron plaque deposition, respectively. Our results highlight the distinct regulation of these two traits, providing crucial insights into how rice adapts to waterlogged conditions and mitigates iron toxicity.

Results

A locus on chromosome 12 governs aerenchyma and iron plaque

Iron plaque formation on rice roots was observed under lowland cultivation conditions but was markedly reduced in upland conditions (Fig. 1a). To elucidate the genetic mechanism controlling iron plaque formation, we screened mutants from a sodium azide (NaN3) induced mutagenized population of the IR64 cultivar in excess iron conditions. On the basis of visual observations, the mutants ‘413’, ‘419’, ‘654’ and AZ1302 exhibited reduced iron plaque formation specifically in adventitious roots. In contrast, iron plaque was not clearly detectable in the seminal roots of either wild-type or mutant plants (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Among these mutants, AZ1302 displayed additional impairments in radial oxygen loss (ROL) (Fig. 1d) and aerenchyma formation (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 1c), warranting detailed genetic investigation. Comparative phenotypic analysis between IR64, which retains normal aerenchyma formation, ROL and iron plaque formation, and AZ1302, which lacks these traits, confirmed developmental and physiological disruptions in the mutant. The AZ1302 mutant does not show major growth or developmental abnormalities of shoots, including tillering ability (Fig. 1f).

a, Comparison of iron plaque formation in rice roots under two distinct cultivation systems. b, Visualization of iron plaque formation in three-week-old IR64 and AZ1302 mutant roots after the iron plaque induction assay for a week. The red arrowheads indicate iron plaque in adventitious roots. Scale bar, 2 cm. c, Enlarged images of adventitious roots, focusing on iron plaque deposition in IR64 but not in the AZ1302 mutant. Scale bars, 1 mm. d, Visualization of ROL via methylene blue staining. A deeper blue colour signifies a higher ROL. Scale bar, 2 cm. e, Representative cross-sections from the middle of adventitious roots of three-week-old plants, exhibiting the difference in aerenchyma formation. Scale bars, 50 µm. f, Plant morphology of IR64 and the AZ1302 mutant at the mature stage. Scale bar, 20 cm. All experiments were repeated three independent times with similar results.

To identify the locus corresponding to the defective iron plaque phenotype of AZ1302, we crossed AZ1302 reciprocally with Nipponbare, a japonica cultivar that is genetically distant from AZ1302 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). The F1 progenies from both crosses displayed wild-type phenotypes for both iron plaque formation (Extended Data Fig. 2) and aerenchyma formation (Extended Data Fig. 2c). The F2 population was segregated into a 3:1 ratio of wild type (408 plants) to mutant (121 plants) (χ2 = 0.05 < χ20.05,1 = 3.84), consistent with a single recessive gene controlling the mutant phenotype in AZ1302. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis of the F2 population identified a single QTL on chromosome 12 associated with the inhibition of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The logarithm of odds (LOD) score plots pinpointed the candidate gene to a 471-kb interval between markers AX-123173361 (26.68 Mb) and AX-123173380 (27.16 Mb) on chromosome 12. Sequence analysis revealed 33 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) within this interval (ORF1–ORF33) (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

A mutation in OsPSY2 disrupts aerenchyma and iron plaque formation

Sequence alignment of the predicted ORFs in the mapped region identified a single functional mutation in the AZ1302 mutant relative to its wild type IR64. A C-to-T single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was detected at the splice donor site between the second exon and intron of OsPSY2 (Os12g0626400), potentially causing splicing variation (Fig. 2a). The primers were designed specifically to detect normal splicing, intron retention and exon skipping (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and sequencing were performed to analyse splicing patterns. In IR64, only normal splicing was observed. The AZ1302 mutant, however, showed a different splicing variant. Analysis of the AZ1302 mutant revealed normal splicing alongside two aberrant splicing events. One event was intron retention, where the second intron was retained. The other was exon skipping, which led to the loss of the second exon (Fig. 2b). Both intron retention, introducing an early stop codon, and exon skipping were predicted to truncate the OsPSY2 protein in AZ1302.

a, Detection of a C-to-T functional SNP in the splice donor site of the OsPSY2 gene in the mapped region of the AZ1302 mutant, possibly causing splicing defects that ultimately generate truncated proteins through intron retention and exon skipping. b, The RT-PCR assay to confirm the effect of the C-to-T SNP on splicing variations in the AZ1302 mutant. The full, uncropped gel image is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. c, Inhibition of aerenchyma formation in response to carotenoid biosynthesis inhibitors (norflurazon and dichlormate) in IR64 (n = 5 roots). The middle regions of approximately 7-cm-long roots were used for aerenchyma visualization and quantification. The data are shown as means ± s.e. P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. d, Representative root cross-sections in response to norflurazon and dichlormate treatment. Scale bars, 50 µm. e, Visualization of iron plaque formation in IR64 in response to norflurazon and dichlormate treatments. Scale bar, 2 cm. The red arrowheads indicate iron plaque. f, Magnified views of adventitious roots demonstrating the inhibition of iron plaque formation in response to norflurazon and dichlormate treatments. Scale bar, 1 mm. In ½ Kimura B solution, 0.1 µM norflurazon or 10 µM dichlormate was added, while the same concentration of DMSO was added in the control. The treatment was performed on two-week-old plants, and analysis was performed on three-week-old plants. All experiments were repeated three independent times with similar results.

OsPSY2 encodes phytoene synthase, a key enzyme in the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway13. To investigate the potential link of carotenoid biosynthesis to both aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, we examined the effect of carotenoid biosynthesis inhibitors on aerenchyma and iron plaque formation. Specifically, we treated IR64 with norflurazon and dichlormate and then evaluated the phenotypes. The inhibitors resulted in a reduction of both aerenchyma (Fig. 2c,d) and iron plaque formation (Fig. 2e,f), further supporting the role of carotenoids in regulating these phenotypes. The results strongly suggested OsPSY2 as the candidate gene for the aerenchyma and iron plaque formation phenotypes, prompting us to subsequently perform functional validation studies.

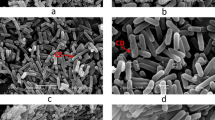

To confirm the regulatory function of OsPSY2 in aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, we used clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) with CRISPR-associated nuclease 9 (Cas9) technology to generate psy2 mutants in the Kitaake background (Fig. 3a). Four single guide RNAs targeting the first exon (two guides), the first intron and the fifth exon were used to create three independent knockout lines for OsPSY2. The psy2-1 line harboured a 1-bp deletion in the first exon, a 13-bp deletion, a 3-bp deletion and a T-to-A SNP in the first intron; and a 23-bp deletion in the fifth exon. The psy2-2 line carried a 3-bp deletion in the first intron and a 4-bp deletion in the fifth exon. The psy2-3 line had a 2-bp deletion in the first exon, a 3-bp deletion in the first intron and a 12-bp deletion in the fifth exon (Extended Data Fig. 3d). All three lines are predicted to encode truncated proteins (of 130, 319 and 137 amino acids, respectively). The psy2 mutants did not exhibit obvious growth or developmental effects in shoots (Fig. 3a). The psy2 mutants exhibited significant reduction of aerenchyma at both the two-week-old and three-week-old stages under hydroponic conditions (Fig. 3b,c and Extended Data Fig. 4a) and reduced iron plaque formation (Fig. 3d,e), with the reduction of aerenchyma consistent across the apical, middle and basal root regions. Iron plaque extracts from psy2 mutant roots showed reduced Fe (Fig. 3f) and Mn content (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Unlike wild-type roots, which formed additional layers of iron plaque outside the epidermis, the psy2 mutants showed a reduction in iron plaque formation. This was demonstrated using laser ablation (LA) inductively coupled plasma (ICP) MS analysis of root cross-sections (Fig. 3g,h and Extended Data Fig. 4c,d). The phenotypic similarities between the psy2 mutants and the AZ1302 mutant suggest that OsPSY2 is the causative gene underlying the defective aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in the AZ1302 mutant.

a, The morphology of CRISPR–Cas9-induced psy2 mutants at the maturity stage. Kitaake and the psy2 mutants exhibit comparable overall growth, with no noticeable differences in plant height or vigour. Scale bar, 20 cm. b, Representative cross-sections taken from the middle of 7-cm-long adventitious roots in three-week-old plants, exhibiting reduction in aerenchyma in psy2 mutants. Scale bars, 50 µm. c, Aerenchyma (%) at 1–2 cm, 3–4 cm and 5–6 cm from the tips of 7-cm-long adventitious roots in three-week-old plants. The data are shown as means ± s.e. (n = 5 root sections). d, Comparison of root systems after the iron plaque induction assay in three-week-old plants. The red arrowheads indicate the region of the adventitious root with obvious reddish iron plaque. Scale bar, 2 cm. e, Magnified views of adventitious roots, illustrating the difference in capacity to form iron plaque in Kitaake and the psy2 mutants. Scale bar, 1 mm. f, Quantification of iron in dithionite-citrate-bicarbonate (DCB) extract. The data are shown as means ± s.e. (n = 5 roots). DW, dry weight. g,h, Visualization of iron in root cross-sections via LA-ICP-MS in control (g) and excess iron (h) conditions. Scale bars, 100 µm. The P values in c and f were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. The experiments were repeated three (a–f) and two (g,h) independent times with similar results.

Besides aerenchyma and iron plaque, psy2 mutants under control conditions did not exhibit other obvious phenotypes except reduced ROL (Extended Data Fig. 4e,f). However, the psy2 mutants displayed reduced root length and increased root dry weight (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b) when grown in excess iron conditions. There was no change in root number, density of lateral roots, shoot length or shoot dry weight (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Additionally, the chlorophyll content was reduced in the psy2 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 5e). The Fe content in roots (Extended Data Fig. 5f), shoots (Extended Data Fig. 5g) and brown rice in the psy2 mutants was unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 5h). The overexpression of OsPSY2 was conducted in an AZ1302-like recombinant inbred line exhibiting reduction in iron plaque and aerenchyma formation (Extended Data Fig. 6a). OsPSY2 overexpression restored both iron plaque (Extended Data Fig. 6b) and aerenchyma formation (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d), further confirming OsPSY2 as a key regulator of these processes. PSY2 overexpression significantly increased root length, root number and shoot length, while lateral root density remained unchanged (Extended Data Fig. 6e–h). These results suggest that OsPSY2 positively regulates adventitious root growth, root number and shoot elongation, but not lateral root formation.

OsPSY2 is expressed in young adventitious roots

To analyse the expression pattern of OsPSY2, Kitaake plants were transformed with GUS reporter constructs driven by the OsPSY2 promoter. Staining with X-Gluc revealed GUS activity in young adventitious roots (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b), which are the primary sites differentiating wild-type and mutant plants in terms of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation. Cross-sectional analysis of stained roots showed that OsPSY2-promoter-driven GUS was predominantly expressed in vascular tissues (Extended Data Fig. 7c). This suggested that OsPSY2 expression in adventitious roots is critical for regulating both aerenchyma and iron plaque development. Additionally, GUS activity was higher in shoots, mainly leaf sheaths (Extended Data Fig. 7d,e). Similar to roots, OsPSY2 was highly expressed in vascular tissues (Extended Data Fig. 7f). The GUS activity indicated OsPSY2 expression in panicles and spikelets (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h). This expression pattern indicates that carotenoid biosynthesis mediated by OsPSY2 may influence physiological and developmental processes in rice.

OsPSY2 mutation disrupts carotenoid biosynthesis, affecting SLs and ABA

To uncover the molecular mechanisms underlying OsPSY2-regulated aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, we quantified carotenoids and carotenoid-derived phytohormones in Kitaake and psy2 mutants. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) followed by quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MS) indicated that the phytoene (Fig. 4a) and β-carotene (Fig. 4b) levels in the roots are significantly lower in the psy2 mutants than in the wild type.

a,b, Quantification of phytoene content (a) and β-carotene content (b) in three-week-old plants (n = 3 biological repeats). c, Quantification of ABA content in roots in three-week-old plants (n = 5 plants’ roots). ABA quantification was performed after excess iron treatment for a week. FW, fresh weight. d,e, Quantification of 4DO (d) and 4-oxo-MeCLA (e) content in roots (n = 6). f–j, Quantification of 9-oxo-carlactone (Oxo-CL) (f), carlactone +30 (CL+30) (g), 4-oxo-MeCLA (h), 4DO (i) and orobanchol (Oro) (j) content in root exudates (n = 6). SL quantification was performed after phosphorus deficiency treatment for a week. All data are shown as means ± s.e., and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

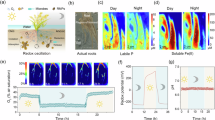

SLs and ABA are key hormones synthesized downstream of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway (Extended Data Fig. 8a). In psy2 mutants, the disruption of the rate-limiting step in this pathway leads to significant reductions in both ABA and SL levels. ABA content in psy2 mutant roots was consistently lower under control (Extended Data Fig. 8b) and excess iron conditions (Fig. 4c) than in the wild type. Similarly, SLs such as 4-deoxyorobanchol (4DO) and methyl 4-oxocarlactonoate (4-oxo-MeCLA) were markedly reduced in psy2 mutant roots (Fig. 4d,e), which was independent of the content of apocarotenoid zaxinone (Extended Data Fig. 8c), an endogenous negative SL biosynthesis regulator in rice14. Root exudates from the mutants also exhibited diminished levels of multiple SLs, including oxo-carlactone (Fig. 4f), 4-oxo-19-OH-CL (Fig. 4g), 4-oxo-MeCLA (Fig. 4h), 4DO (Fig. 4i) and orobanchol (Fig. 4j). The reduction in SL exudation significantly decreased Striga germination, suggesting that OsPSY2 could be a potential target to reduce Striga susceptibility in rice (Extended Data Fig. 8d). These results highlight the critical role of carotenoid biosynthesis, mediated by PSY2, in maintaining hormonal profiles essential for rice root development and function.

SL and ABA regulate aerenchyma and iron plaque, respectively

To identify the hormones responsible for regulating aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, synthetic SL GR24 and ABA were exogenously supplied to wild-type and mutant plants under hydroponic conditions. The ABA treatment enhanced iron plaque in Kitaake, while it restored it in psy2 mutants; however, GR24 did not influence iron plaque formation in psy2 mutants (Fig. 5a–c and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b). The ABA treatment did not affect aerenchyma formation, while both racemic (rac)-GR24 and (+)-GR24 restored it in psy2 mutants at both the two-week-old and three-week-old stages (Fig. 5d–f and Extended Data Fig. 9c,d).

a, Enhancement of iron plaque formation in Kitaake roots treated with ABA, but not with (rac)-GR24. Scale bars, 1 mm. b, Restoration of iron plaque in psy2 roots by ABA treatment, but not (rac)-GR24 treatment. Scale bars, 1 mm. c, Quantification of Fe in DCB extracts. The data are shown as means ± s.e. (n = 4 biological repeats). Different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 according to two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s test. d, Aerenchyma (%) at 3–4 cm and 5–6 cm from the tips of 7-cm-long adventitious roots in three-week-old plants in response to ABA and (rac)-GR24 treatment. The aerenchyma in psy2-3 responded similarly to both (rac)-GR24 and (+)-GR24 (Extended Data Fig. 9d). The data are shown as means ± s.e. (n = 3 root cross-sections). The P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. e,f, Representative cross-sections taken from the middles of Kitaake (e) and psy2 mutant roots (f) after ABA and GR24 treatment. Scale bars, 50 µm. All experiments were repeated three independent times with similar results.

In addition, GR24 and ABA had contrasting effects on root development. The GR24 treatment led to a reduction in both root dry weight and shoot length, while root length was differentially affected, showing an increase in the wild type but a decrease in the psy2 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 9e–g). ABA promoted root hair elongation, but its influence on root hair density varied. A reduction in root hair density was observed in the wild type, while an increase occurred in the psy2 mutants (Extended Data Fig. 9h,i). These findings demonstrate that SLs specifically regulate aerenchyma formation, while ABA specifically governs iron plaque formation, both of which are downstream of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway.

Genetic and chemical disruption of the SL and ABA pathways distinctly alters aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in roots. The SL biosynthetic pathway mutants d17 and d10 and the SL signalling mutant d14 (Extended Data Fig. 10a) exhibited shorter root length (Extended Data Fig. 10b). A significant reduction in aerenchyma formation was observed in SL mutants at 2–3 cm and 4–5 cm from the tips in same-length roots (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d) without inhibition of iron plaque formation (Extended Data Fig. 10e). This phenotype further supports critical roles of SLs in aerenchyma formation. We also performed ABA pathway inhibition with ABA Antagonist1 (AA1) treatment15. AA1 preferentially affected iron plaque deposition in Kitaake (Extended Data Fig. 10f), further demonstrating the essential role of ABA in iron plaque deposition.

Discussion

Aerenchyma has been known as a key regulator of iron plaque formation in rice roots16, with both being induced by excess iron17. However, our findings indicate that the aerenchyma in the root is neither necessary nor sufficient for iron plaque formation. The NaN3-induced mutants with normal aerenchyma but impaired iron plaque formation further support this finding. Furthermore, this study provides a critical understanding of the distinct hormonal regulation of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in rice, uncovering the roles of SLs and ABA as downstream effectors of carotenoid biosynthesis. The specificity of hormonal regulation was evident, as GR24 did not affect iron plaque formation, and ABA failed to influence aerenchyma formation in psy2 mutants. Moreover, the reduction of aerenchyma in SL biosynthesis and signalling mutants genetically confirms SLs’ role in aerenchyma formation. Besides, SLs and ABA regulate the development of adventitious roots18 and root hairs19, respectively. These findings emphasize the distinct yet complementary roles of SLs and ABA in root plasticity. SLs are central to aerenchyma development, facilitating oxygen transport under anoxic conditions, while ABA regulates iron plaque deposition, protecting roots from iron toxicity. Both pathways are tightly linked to carotenoid biosynthesis, mediated by OsPSY2, as a critical upstream regulator. In the psy2 mutants, which lack extensive aerenchyma, ABA treatment restores iron plaque formation, possibly by activating an oxidation mechanism involved in Fe2+ oxidation20.

PSY is involved in the first step of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway21. Mutations in the genes encoding phytoene synthase exhibited similar effects as mutations in subsequent steps such as the reduction in carotenoids, SLs22 and ABA23 content. Unlike mutations in other steps, the presence of three OsPSYs with varied expression and regulatory patterns13 prevented severe growth and developmental effects such as dwarfism and high tillering in psy2 mutants. OsPSY2 may act in a tissue-specific manner, and SL levels in nodes and shoots were not measured, so local biosynthesis may remain unaffected in psy2 mutants. SLs and aerenchyma are reduced to a much greater extent in a psy2, potentially due to phosphorus starvation treatment24 and exclusive evaluation of adventitious roots, respectively. The pleiotropic regulation of root hair growth by OsPSY2 and restoration by ABA in psy2 mutants suggest the involvement of profuse root hairs in oxidizing Fe2+ to form iron plaque.

While our results provide significant insights, SL and ABA biosynthesis are regulated in multiple steps. Future studies on genes directly regulating either SLs or ABA should aim to provide more comprehensive insights into the specific genes involved and their possible interactions. The assessment of iron plaque formation in ABA biosynthesis and signalling mutants will further confirm the role of ABA and independent regulation of iron plaque. This study reveals a specific role of OsPSY2 in coordinating aerenchyma formation and iron plaque deposition, but the rice genome encodes multiple PSY homologues13. Their potential contributions to root plasticity and stress adaptation remain largely unexplored. Future investigations into the functional redundancy or divergence among PSY paralogues could provide deeper insights into how rice fine-tunes carotenoid-derived hormone biosynthesis in response to environmental cues. Such studies may uncover novel regulatory modules that enhance plant adaptability to fluctuating soil conditions.

Additionally, investigations into other NaN3-induced iron plaque mutants with normal aerenchyma formation will provide broader and more detailed insights into the underlying mechanisms. Besides rhizosphere signalling25, SLs are known to interact with other hormonal pathways including ethylene26, a well-known regulator of inducible aerenchyma27. The effects of SLs and ABA may be mediated through interactions with other hormone signalling pathways to play critical roles in root development. Further research should explore whether these regulatory mechanisms operate independently or in a coordinated manner to control constitutive and inducible aerenchyma formation in rice adventitious roots.

Aerenchyma formation enhances tolerance of waterlogging28 and drought stress29, while iron plaque constitutes a barrier to elements such as As30,31, Cd32,33, Cr34, Pb35, Se36 and Si37 by adsorbing them. Despite forming in response to toxic iron38, iron plaque acts as an iron reservoir32 through organic-acid-mediated dissolution32 and acts as a significant carbon sink in rice fields39. Taken together, understanding the molecular and hormonal regulation of these root traits presents new opportunities to enhance stress resilience and optimize nutrient management in rice and other crops. Our findings highlight strategies to modify root traits for agronomic benefits and assess the conservation of regulatory pathways in other species, particularly in waterlogged and iron-toxic soils.

Methods

Plant materials

NaN3 mutant lines in the IR64 rice variety background were developed and self-pollinated for over 15 generations by the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute (Wufeng, Taichung, Taiwan, ROC)40. Among the 1,888 mutant lines, the AZ1302 mutant was identified as exhibiting inhibited aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in adventitious roots. To map the gene responsible for these phenotypes, AZ1302 was crossed with Nipponbare, a polymorphic parent, to produce F1 progenies and an F2 mapping population. The early-flowering Kitaake cultivar41 was used for the generation of CRISPR–Cas9-induced mutants and promoter–GUS reporter lines. For the generation of overexpression lines, an AZ1302-like recombinant inbred line (Nipponbare × AZ1302 F6) predominantly exhibiting SNPs similar to Nipponbare was used.

Growth conditions

Seeds were disinfected with 50% sodium hypochlorite (J. T. Baker Inc.) for 15 min and subsequently cleaned three times with water. The disinfected seeds were kept on moistened filter paper and incubated in darkness at 30 °C for five days. Three days after germination, the seedlings were transferred to 1/2 Kimura B nutrient solution (pH 4.75)42. For the iron plaque induction assay, two-week-old seedlings were treated with 360 µM FeSO4·7H2O for one week, with the nutrient solution refreshed every alternate day. The formation of iron plaque was visualized as a reddish coloration after one week of excess Fe treatment.

To assess tillering ability, the plant materials were cultivated in a paddy field at Agricultural Experimental Station, National Chung Hsing University, Wufeng Township, Taichung, Taiwan. The fertilization rate was 125 kg ha−1 N, 75 kg ha−1 P2O5 and 50 kg ha−1 K2O. Seedlings were individually transplanted at a density of 30 plants per plot with a spacing of 30 cm × 15 cm.

Root tissue embedding, sectioning and imaging

The tissues were fixed in 3% (w/v) agarose, and 80-µm sections were prepared using a vibratome microtome (VT1200S, Leica Microsystem GmbH). To assess the aerenchyma of SL mutants, root segments were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde prepared in 1× PBS (pH 6.9) under vacuum at room temperature for 1 h, and the fixed roots were embedded in 5% (w/v) agarose. The cut sections were visualized under a light microscope, and the proportion of aerenchyma was quantified using ImageJ software (v.1.43u, US National Institutes of Health)43. For representative imaging of cell wall structures, sections were stained overnight with 0.1% (v/v) SR2200 (ref. 44). Confocal imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 710 inverted confocal microscope equipped with a 405-nm laser line for excitation; emission signals were collected between 430 and 500 nm to detect the blue fluorescence emitted by SR2200. To determine the length and density of root hairs, root segments from the apical, middle and basal regions were imaged at ×10 and ×20 magnifications, respectively. Measurements of root hair density and length were also performed using ImageJ.

Evaluation of ROL

Qualitative evaluation of ROL in the whole roots was performed with methylene blue, which becomes bluish in the presence of oxygen45. A 0.1% (w/v) agar was prepared, and 13 mg l−1 methylene blue was added to the cooled solution. The blue solution was decolourized by 130 mg l−1 sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4) (Merck KGaA) to a colourless solution. The solution was transferred into a clear plastic case with compartments measuring 4.5 cm long, 1 cm wide and 15 cm high. The plants were held in such a way that the root–shoot junction was approximately 2 cm below the surface of the solution. The roots were immersed in the prepared solution for 60 min at ambient temperature.

Gene mapping

DNA was isolated from both parental lines and the F2 population (n = 126) by employing the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). The Affymetrix rice 44K SNP array, which includes 44,100 SNPs evenly distributed throughout the rice genome, with approximately one SNP every 10 kb, was employed for genotyping46. Genotypes were analysed using Axiom Analysis Suite through the Best Practice Workflow (Thermo Fisher)47.

QTL IciMapping v.4.2 with inclusive composite interval mapping was employed to identify the QTL associated with iron plaque formation48,49. Markers with over 10% missing data were omitted from further analysis. The remaining markers were categorized using a LOD score threshold of 3, ordered using the k-Optimality algorithm (LOD 2-OptMAP) and rippled with a window size of 5 Mb. Recombination frequencies were converted to centimorgans (cM) using the Kosambi function, and QTL were mapped with parameters set at a step size of 1.0 cM and a PIN value of 0.001. A 1,000-permutation test was performed to estimate the QTL LOD threshold at a 95% confidence level. The additive effects and phenotypic variance explained for each QTL were also calculated.

RT-PCR analysis

The extraction of total RNA from 21-day-old adventitious roots and third leaves was conducted using a Total RNA Mini Kit (Plant) (Geneaid Biotech Ltd). Complementary DNA was synthesized from the isolated RNA with iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). RT-PCR was conducted to amplify full-length coding sequences, intron retention and exon skipping using specific primers. OsUBC2 served as the internal control for RT-PCR (Supplementary Data 1).

Exogenous carotenoid biosynthesis inhibitor treatment

Norflurazon and dichlormate were used to inhibit carotenoid biosynthesis through the inhibition of phytoene desaturase50 and ζ-carotene desaturase51, respectively. Stock solutions of 1 mM norflurazon (LGC Group) and 10 mM dichlormate (LGC Group) were prepared in DMSO. Two-week-old plants were treated with 0.1 µM norflurazon and 10 µM dichlormate, which were incorporated into 1/2 Kimura B solution. The visualization of aerenchyma and iron plaque was performed in three-week-old plants.

Knockout and overexpression assays

Four guide RNAs targeting the PSY2 gene were designed for generating CRISPR–Cas9 mutants. The oligonucleotide sequences for generating the single guide RNAs are provided in Supplementary Data 2. The CRISPR–Cas9 expression vector pYLCRISPR–Cas9Pubi-H was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 and subsequently transformed into calli derived from the japonica rice variety Kitaake (wild type). Three independent homozygous psy2 mutant lines free of the Cas9 transgene (T3 generation) were obtained, and the mutations were verified by sequencing using primer pairs flanking the target sites (Supplementary Data 1). Aerenchyma and iron plaque formation, ROL, root and shoot length, and root and shoot dry weight were assessed.

For the overexpression of PSY2, the entire coding DNA sequence of the PSY2 gene was amplified from Kitaake using RT-PCR. The pZmUBI::PSY2 expression vector was constructed in the backbone of vector pMHb7Fm21GW-UBIL and introduced into Agrobacterium. This construct was transformed into calli of Kitaake, CRISPR–Cas9-induced psy2 mutants and the Nipponbare × AZ1302 F6 recombinant line (a Nipponbare-like line carrying the PSY2 gene from AZ1302). Two independent transgenic lines exhibiting higher OsPSY2 expression were obtained, and aerenchyma and iron plaque formation was assessed.

Elemental analyses

The elemental concentration in iron plaque, roots, shoots and brown rice was assessed via ICP optical emission spectrometry (PerkinElmer Inc.). A DCB solution was applied to extract iron plaque surrounding the roots52. Roots after DCB extraction, shoots and grains were cleaned sequentially with ddH2O, 10 mM CaCl2 and ddH2O again, each for 20 min. After cleaning, the tissues were dried at 70 °C for three days. Approximately 1 ml of HNO3 was added to the weighed tissues in Teflon tubes and allowed to stand at room temperature overnight. The following day, 0.5 ml of H2O2 was added and held at room temperature for 30 min before microwave digestion using a MARS 6 PFAS Extraction system (CEM Corporation). After digestion, the solution was transferred into a 15-ml tube, and 8.5 ml of 2% HNO3 was added. The solution was filtered using 0.45-µm filters into new 15-ml tubes and stored until elemental analysis was conducted.

To visualize Fe in the roots, fresh roots from 28-day-old plants were carefully washed and dried using filter paper. Root segments taken at 3–4 cm from the tip were fixed in 2% agarose and cut into 200-μm transverse sections with a vibrating blade microtome (VT1200S, Leica Microsystem GmbH). These sections were mounted on double-sided tape affixed to microscope glass slides and set to dry at room temperature. The spatial scattering of 56Fe within the root sections was mapped using a quadrupole ICP mass spectrometer (Agilent 7800; Agilent Technologies), connected to a laser ablation system (NWR 266; ESI). Ablation was conducted with a Nd:YAG laser (266-nm wavelength), using a 5-µm spot size and a cycle frequency of 50 Hz. Argon carrier gas transported the ablated material to the ICP mass spectrometer. Data processing was performed using IOLITE v.3.65 software (Iolite Softwares Private Limited), and the 13C+ signal served as an internal normalization standard to mitigate signal variations caused by differences in tissue density.

Expression pattern analysis

The spatial distribution of PSY2 gene expression was assessed using a promoter–GUS reporter system. A 1,917-bp region upstream of the PSY2 start codon (ATG) was amplified via PCR using the Nipponbare cultivar’s genomic DNA (Supplementary Data 1). The amplified promoter region was cloned into the binary vector pGWB3 (ref. 53). A p35S::GUS construct served as a positive control. Both constructs were transformed into the Kitaake background.

Roots and shoots of transgenic plants aged three weeks were subjected to GUS staining using buffer (2 mM X-Gluc, 2 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 2 mM K4Fe(CN)6·3H2O, 50 mM NaHPO4 buffer (pH 7.2), 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100) at 37 °C. The pPSY2::GUS transgenic plants were stained for up to two days, while the p35S::GUS plants were stained overnight. Chlorophyll was decolourized using 95% ethanol, and stained tissues were photographed. Cross-sections of the tissues were visualized and imaged under a light microscope.

Quantification of carotenoids in root tissues

For carotenoid extraction, 19-day-old plants were treated with 10 µM dichlormate for 48 h to partially inhibit β-carotene biosynthesis to obtain the quantification of phytoene as well as β-carotene51. Freeze-dried samples (100 mg) were homogenized using liquid nitrogen and transferred into 2-ml Eppendorf tubes. The powdered samples were mixed with 1 ml of ethanol containing 1 mg ml−1 butylated hydroxy anisole (Sigma Aldrich) to prevent the oxidation of carotenoids. After vortexing, the samples were sonicated on an ice bath for 15 min using Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner (Marshall Scientific) and centrifuged at 4 °C at 1,800 g for 5 min. After 200 µl of supernatant was collected, the extraction was repeated twice more, and 1 ml and 800 µl of supernatants were collected in the subsequent extraction. The collected supernatants were kept in darkness at −20 °C before further processing.

Carotenoids were identified and quantified using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UPLC system (Agilent Technologies) coupled online to an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source of an Agilent 6545 XT quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The samples were separated using a YMC Carotenoid column (3 μm, 2.0 × 150 mm, YMC Co., Ltd). The column temperature was 30 °C. The mobile phases were methanol:water (9:1, v/v; eluent A) and isopropanol:methanol (7:3, v/v; eluent B). The flow rate was 0.3 ml min−1. The instrument was operated in positive full-scan mode (m/z of 100–1,500). Chromatogram acquisition, detection of mass spectral peaks and their waveform processing were performed using Agilent Qualitative Analysis v.10.0 and Agilent MassHunter Pro1finder v.B.10.00 software.

Quantification of ABA in root tissues

To determine ABA content, 100 mg of fresh root tissue was harvested in 2-ml Eppendorf tubes. Liquid nitrogen was employed to grind the samples into a fine powder, which was then mixed in 500 µl of extraction solution (2-propanol/H2O/HCl, 2:1:0.002) spiked with an internal standard (50 µl of methanol containing 2 ng of d6-ABA). The tubes were agitated for 30 min at 4 °C. Next, 1 ml of dichloromethane was added to each tube, followed by another round of agitation for 30 min at 4 °C. After mixing, the tubes were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C, resulting in plant debris separating the two liquid phases. The lower phase (500 µl) was carefully collected and dried using Labconco CentriVap Benchtop Vacuum Concentrators (Fisher Scientific).

The dried extracts were dissolved in 100 µl of 80% methanol and subjected to vortexing for 5 min and then centrifugation at 13,200 g at 4 °C for 10 min. The resuspended samples were subjected to analysis using UPLC (Waters) coupled online to the Waters Xevo TQ-XS triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters). The sample (in duplicate with 5 μl per injection) was separated with a Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm particle size, 2.1 × 100 mm). The column was operated at 30 °C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1. The mobile phase comprised a gradient elution system of aqueous solution with 0.1% acetic acid and methanol with 0.1% acetic acid. Multiple reaction monitoring in negative mode was employed to monitor the characteristic MS transitions for ABA (m/z, 263 → 153) and d6-ABA (m/z, 269 → 159). Data were acquired and processed using MassLynx v.4.2 and TargetLynx software (Waters).

Quantification of SLs in root exudates and roots

SLs present in root exudates were collected and quantified using an established protocol24. Briefly, phosphorous deficiency treatment was conducted on two-week-old plants for seven days, and the media containing exudates were collected. Root exudates enriched with 2 ng of GR24 were loaded onto a preconditioned C18-Fast Reversed-SPE column 500 mg/3 ml (Grace) with 3 ml of methanol and subsequently 3 ml of water. The column was washed with 3 ml of water, followed by elution of SLs twice with 2 ml and 3 ml of acetone. The SL-containing fractions were concentrated to approximately 500 μl of an aqueous solution and then extracted with 1 ml of ethyl acetate. For LC-MS/MS analysis, the enriched SL organic fraction (750 μl) was vacuum-dried, resuspended in 100 μl of acetonitrile:water (25:75, v:v) and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter.

SLs from roots were extracted following the procedure described by Wang et al.14. Lyophilized and ground rice roots (25 mg) were spiked with 2 ng of GR24. Two separate extractions were performed with sonication using a Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner (Marshall Scientific), each using 2 ml of ethyl acetate for 15 min. Each extraction was followed by centrifugation at 1,800 g for 8 min at 4 °C. The obtained supernatants were pooled and vacuum-dried. The residual SLs were resuspended in 50 μl of ethyl acetate, mixed with 2 ml of hexane and loaded onto a 500 mg/3 ml silica SPE column (Grace). Then, 3 ml of hexane was passed through the column, and SLs were eluted with 3 ml of ethyl acetate. The eluates were vacuum-dried, resuspended in 150 μl of acetonitrile:water (25:75, v:v) and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter for LC-MS/MS analysis. Quantification of SLs was conducted on a UHPLC-Triple-Stage Quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Altis) following established procedures54.

Bioassay for Striga hermonthica seed germination

Striga seed germination was assessed by following a published method55. Briefly, Striga seeds were preconditioned at 30 °C under moist conditions for ten days. 50 µl of root exudates collected from Kitaake and psy2 mutants were treated with Striga seeds. Subsequently, the seeds were incubated at 30 °C in the dark for another two days. The germinated and non-germinated seeds were counted with a binocular microscope, and the germination rate was determined.

Exogenous ABA and GR24 treatment

Stock solutions of 25 mM (rac)-GR24 (PhytoTech Labs, Inc.), 10 mM (+)-GR24 (US Biological) and 250 µM ABA (Merck KGaA) were prepared in DMSO. For treatment, 11-day-old hydroponically grown plants were transferred to 1/2 Kimura B solution containing 0.01 µM ABA or 5 µM GR24, with DMSO serving as the control. The treatments were continued for ten days. For iron plaque induction, excess iron treatment was done on 14-day-old plants as mentioned previously. Aerenchyma and iron plaque formation was observed in two-week-old and three-week-old plants. The DCB solution was applied to extract iron plaque surrounding the newly emerged adventitious roots. Root dry weight, root length, shoot length, root hair density and root hair length were also measured.

Genetic and chemical disruption of the SL and ABA pathways

The SL biosynthesis mutants d17 and d10, with disruption in the conversion from 9-cis-β-carotene to carlactone56, and the SL signalling mutant d14 (ref. 57) were used to assess the role of SLs in aerenchyma and iron plaque formation. The wild-type Shiokari and the mutants were grown for three weeks, and aerenchyma in the adventitious roots was visualized at 2–3 cm and 4–5 cm from the root tips. To determine the function of the ABA pathway in iron plaque formation, the specific ABA signalling inhibitor AA1 was applied15. Wild-type (Kitaake) plants were treated with 1 µM AAl at the ten-day-old stage, and excess Fe treatment was applied to two-week-old plants. The iron plaque phenotype was examined at the three-week-old stage.

Data analysis and visualization

If not otherwise stated, the data were analysed and visualized using R v.4.1.3 (ref. 58). The normality of the data and the homogeneity of their variance were determined via the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. P values were calculated for two-tailed t-tests. For multiple comparisons between genotypes and treatments, two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was conducted. For data not meeting the assumptions of normality and/or homogeneity of variance, Welch’s t-test and the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Dunn test were conducted.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The plant materials used in this research can be provided upon request, with associated fees to cover sterilization, pathology screening for obtaining a phytosanitary certificate and adherence to seed import regulations specific to the destination country. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, Y. et al. A root system architecture regulator modulates OsPIN2 polar localization in rice. Nat. Commun. 16, 15 (2025).

Hazman, M. & Brown, K. M. Progressive drought alters architectural and anatomical traits of rice roots. Rice 11, 62 (2018).

Magneschi, L. & Perata, P. Rice germination and seedling growth in the absence of oxygen. Ann. Bot. 103, 181–196 (2009).

Matthus, E. et al. Loci, genes, and mechanisms associated with tolerance to ferrous iron toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 2085–2098 (2015).

Li, J., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, W. Biochemical mechanisms underlying iron plaque-mediated phosphorus accumulation and uptake in rice roots. Sci. Total Environ. 929, 172331 (2024).

Chan, C. S., Dykes, G. E., Hoover, R. L., Limmer, M. A. & Seyfferth, A. L. Gallionellaceae in rice root plaque: metabolic roles in iron oxidation, nutrient cycling, and plant interactions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 89, e0057023 (2023).

Awasthi, S., Chauhan, R., Srivastava, S. & Tripathi, D. The journey of arsenic from soil to grain in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1007 (2017).

Jackson, M. B. & Armstrong, W. Formation of aerenchyma and the processes of plant ventilation in relation to soil flooding and submergence. Plant Biol. 1, 274–287 (1999).

Colmer, T. D., Cox, M. C. H. & Voesenek, L. A. C. J. Root aeration in rice (Oryza sativa): evaluation of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and ethylene as possible regulators of root acclimatizations. N. Phytol. 170, 767–778 (2006).

Yamauchi, T., Tanaka, A., Tsutsumi, N., Inukai, Y. & Nakazono, M. A role for auxin in ethylene-dependent inducible aerenchyma formation in rice roots. Plants 9, 610 (2020).

Yamauchi, T. et al. An NADPH oxidase RBOH functions in rice roots during lysigenous aerenchyma formation under oxygen-deficient conditions. Plant Cell 29, 775–790 (2017).

Evans, D. E. Aerenchyma formation. N. Phytol. 161, 35–49 (2004).

Welsch, R., Wüst, F., Bär, C., Al-Babili, S. & Beyer, P. A third phytoene synthase is devoted to abiotic stress-induced abscisic acid formation in rice and defines functional diversification of phytoene synthase. Genes Plant Physiol. 147, 367–380 (2008).

Wang, J. Y. et al. The apocarotenoid metabolite zaxinone regulates growth and strigolactone biosynthesis in rice. Nat. Commun. 10, 810 (2019).

Ye, Y. et al. A novel chemical inhibitor of ABA signaling targets all ABA receptors. Plant Physiol. 173, 2356–2369 (2017).

Sebastian, A. & Prasad, M. N. Trace element management in rice. Agronomy 5, 374–404 (2015).

Das, S., Tyagi, W., Rai, M. & Yumnam, J. S. Understanding Fe2+ toxicity and P deficiency tolerance in rice for enhancing productivity under acidic soils. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 33, 97–117 (2017).

Sun, H. et al. A strigolactone signal is required for adventitious root formation in rice. Ann. Bot. 115, 1155–1162 (2015).

Wang, T. et al. Abscisic acid regulates auxin homeostasis in rice root tips to promote root hair elongation. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1121 (2017).

Yang, X.-J. et al. The class III peroxidase gene OsPrx24 is important for root iron plaque formation and benefits phosphorus uptake in rice plants under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Plant Soil 448, 621–646 (2020).

Fraser, P. D. et al. Evaluation of transgenic tomato plants expressing an additional phytoene synthase in a fruit-specific manner. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1092–1097 (2002).

Zhou, H. et al. HIGH-TILLERING AND DWARF 12 modulates photosynthesis and plant architecture by affecting carotenoid biosynthesis in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 1212–1224 (2021).

Fang, J. et al. Mutations of genes in synthesis of the carotenoid precursors of ABA lead to pre-harvest sprouting and photo-oxidation in rice. Plant J. 54, 177–189 (2008).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Protocol for characterizing strigolactones released by plant roots. STAR Protoc. 3, 101352 (2022).

Wang, J. Y., Chen, G.-T. E., Braguy, J. & Al-Babili, S. Distinguishing the functions of canonical strigolactones as rhizospheric signals. Trends Plant Sci. 29, 925–936 (2024).

Cheng, X., Ruyter-Spira, C. & Bouwmeester, H. The interaction between strigolactones and other plant hormones in the regulation of plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 199 (2013).

Justin, S. H. F. W. & Armstrong, W. Evidence for the involvement of ethene in aerenchyma formation in adventitious roots of rice (Oryza sativa L.). N. Phytol. 118, 49–62 (1991).

Pedersen, O., Sauter, M., Colmer, T. D. & Nakazono, M. Regulation of root adaptive anatomical and morphological traits during low soil oxygen. N. Phytol. 229, 42–49 (2021).

Fonta, J. E., Giri, J., Vejchasarn, P., Lynch, J. P. & Brown, K. M. Spatiotemporal responses of rice root architecture and anatomy to drought. Plant Soil 479, 443–464 (2022).

Lee, C.-H., Hsieh, Y.-C., Lin, T.-H. & Lee, D.-Y. Iron plaque formation and its effect on arsenic uptake by different genotypes of paddy rice. Plant Soil 363, 231–241 (2013).

Wu, C. et al. The effect of silicon on iron plaque formation and arsenic accumulation in rice genotypes with different radial oxygen loss (ROL). Environ. Pollut. 212, 27–33 (2016).

Sebastian, A. & Prasad, M. N. Iron plaque decreases cadmium accumulation in Oryza sativa L. and serves as a source of iron. Plant Biol. 18, 1008–1015 (2016).

Zhou, P. et al. Iron-based nanomaterials reduce cadmium toxicity in rice (Oryza sativa L.) by modulating phytohormones, phytochelatin, cadmium transport genes and iron plaque formation. Environ. Pollut. 320, 121063 (2023).

Zandi, P. et al. Speciation and distribution of chromium (III) in rice root tip and mature zone: the significant impact of root exudation and iron plaque on chromium bioavailability. J. Hazard. Mater. 448, 130992 (2023).

Li, F.-L. et al. Combined effect of rice genotypes and soil characteristics on iron plaque formation related to Pb uptake by rice in paddy soils. J. Soils Sediments 16, 150–158 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Iron plaque effects on selenium and cadmium stabilization in Cd-contaminated seleniferous rice seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 22772–22786 (2023).

Martín-Esquinas, A. & Hernández-Apaolaza, L. Rice responses to silicon addition at different Fe status and growth pH: evaluation of ploidy changes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 163, 296–307 (2021).

Mahender, A., Swamy, B. P. M., Anandan, A. & Ali, J. Tolerance of iron-deficient and -toxic soil conditions in rice. Plants 8, 31 (2019).

Wei, L. et al. Visualization and quantification of carbon ‘rusty sink’ by rice root iron plaque: mechanisms, functions, and global implications. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 6711–6727 (2022).

Wang, C.-S., Tseng, T.-H. & Lin, C.-Y. Rice biotech research at the Taiwan Agricultural Research Institute. Asia Pac. Biotech. N. 6, 950–956 (2002).

Kim, S. L., Choi, M., Jung, K.-H. & An, G. Analysis of the early-flowering mechanisms and generation of T-DNA tagging lines in Kitaake, a model rice cultivar. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 4169–4182 (2013).

Huang, G., Ding, C., Li, Y., Zhang, T. & Wang, X. Selenium enhances iron plaque formation by elevating the radial oxygen loss of roots to reduce cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 398, 122860 (2020).

Collins, T. J. ImageJ for microscopy. BioTechniques 43, S25–S30 (2007).

Musielak, T. J., Schenkel, L., Kolb, M., Henschen, A. & Bayer, M. A simple and versatile cell wall staining protocol to study plant reproduction. Plant Reprod. 28, 161–169 (2015).

Shiono, K. et al. Abscisic acid is required for exodermal suberization to form a barrier to radial oxygen loss in the adventitious roots of rice (Oryza sativa). N. Phytol. 233, 655–669 (2022).

Tung, C.-W. et al. Development of a research platform for dissecting phenotype–genotype associations in rice (Oryza spp.). Rice 3, 205–217 (2010).

Pavan, S. et al. Recommendations for choosing the genotyping method and best practices for quality control in crop genomewide association studies. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00447 (2020).

Li, H., Ye, G. & Wang, J. A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics 175, 361–374 (2007).

Meng, L., Li, H., Zhang, L. & Wang, J. QTL IciMapping: integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 3, 269–283 (2015).

Bartels, P. G. & Watson, C. W. Inhibition of carotenoid synthesis by fluridone and norflurazon. Weed Sci. 26, 198–203 (1978).

Burns, E. R., Buchanan, G. A. & Carter, M. C. Inhibition of carotenoid synthesis as a mechanism of action of amitrole, dichlormate, and pyriclor 1. Plant Physiol. 47, 144–148 (1971).

Zhang, Q. et al. Water managements limit heavy metal accumulation in rice: dual effects of iron-plaque formation and microbial communities. Sci. Total Environ. 687, 790–799 (2019).

Nakagawa, T. et al. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41 (2007).

Chen, G.-T. E. et al. Disruption of the rice 4-DEOXYOROBANCHOL HYDROXYLASE unravels specific functions of canonical strigolactones. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2306263120 (2023).

Jamil, M., Kanampiu, F. K., Karaya, H., Charnikhova, T. & Bouwmeester, H. J. Striga hermonthica parasitism in maize in response to N and P fertilisers. Field Crops Res. 134, 1–10 (2012).

Chen, G. E., Wang, J. Y., Jamil, M., Braguy, J. & Al-Babili, S. 9-cis-β-Apo-10′-carotenal is the precursor of strigolactones in planta. Planta 256, 88 (2022).

Wang, J. Y., Lin, P. Y. & Al-Babili, S. On the biosynthesis and evolution of apocarotenoid plant growth regulators. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 109, 3–11 (2021).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from Academia Sinica (AS-SS-113-01) and NSTC (NSTC-113-2313-B-001-009-MY3) Taiwan to K.-C.Y. and the Competitive Research Grant 2024 (CRG2024) to S.A.-B. We thank W.-S. Liao for performing mutant screening. We thank the Plant Tech Core Facility of the Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center at Academia Sinica for the assistance with CRISPR vector construction. We also thank L.-Y. Kuang and S.-M. Chen from the Transgenic Plant Core Facility at Academia Sinica for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation services. For UPLC–MS analysis, we acknowledge T.-H. Chang, G.-M. Lin and the Metabolomics Core Facility of the Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center at Academia Sinica for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K.S. and K.-C.Y. conceptualized the project and developed the methodology. I.-C.T. and C.-H.H. performed the elemental analysis. C.-Y.L. and M.T. conducted the carotenoid and ABA quantification. J.Y.W., M.J. and S.A.-B. conducted the SL quantification. K.-C.Y., C.-S.W. and S.A.-B. acquired the resources. Y.Z. and I.B. conducted the aerenchyma assessment of the SL mutants. Y.Z. and L.B. conducted the iron plaque induction assay in the SL mutants. J.K.S. and K.-C.Y. wrote the paper. J.K.S., K.-C.Y. and J.Y.W. created the figures and visualizations. K.-C.Y. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Bing Wang, Takaki Yamauchi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Screening of iron plaque and aerenchyma mutant.

a, Visualization of roots in 3-week-old plants after iron plaque induction assay, conducted by treating 360 µM FeSO4.7H2O for a week. The IR64 cultivar developed iron plaque whereas mutants ‘413’, ‘419’, ‘654’, and AZ1302 were screened as iron plaque mutant lines. Red arrowheads indicate iron plaque forming adventitious roots. Scale bars, 2 cm. b, Magnified view of adventitious roots, revealing iron plaque formation. Scale bars, 1 mm. c, Representative cross-sections taken from the middle of an adventitious roots of 3-week-old IR64 and screened iron plaque mutant lines. Scale bars, 50 µm. All experiments were repeated at three independent times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Phenotyping of Nipponbare, AZ1302 mutant and their F1 progenies.

a, Morphology of aerenchyma and iron plaque mutant AZ1302, Nipponbare wild type and their F1 progenies in mature stage. All the plants were cultivated in paddy field following normal agronomic practice. Scale bars, 20 cm. b, Rice root system in 3-week-old plants after iron plaque induction assay. Red arrowheads indicate iron plaque forming adventitious roots. Scale bars, 2 cm. c, Representative cross-section taken from the middle of a 7 cm-long adventitious root of 3-week-old plants. Scale bars, 50 µm. All experiments were repeated at three independent times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 3 The gene regulating iron plaque was mapped in chromosome 12 and PSY2 was identified as a candidate gene.

a, Gene mapping of iron plaque phenotype in the F2 population, indicating one mutant gene on chromosome 12 is responsible for defective iron plaque in AZ1302 mutant. The X-axes indicate genetic distance and y-axes indicate logarithm of odds (LOD) score. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the LOD threshold value. The vertical dotted lines separate chromosomes. b, Identification of 33 candidate open reading frames (ORFs) in the mapped region. c, Designing of primer pairs to detect full length CDS, intron retention, exon skipping and normal splicing variants. d, Chromatogram of selected site of OsPSY2 showing mutations in psy2 mutants. The chromatogram in left, middle and right shows mutations in first exon, first intron and fifth exon respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Iron plaque is inhibited in psy2 mutants.

a, Root aerenchyma (%) in psy2 mutants. Aerenchyma in 5 cm-long adventitious roots was measured at 1-2 cm and 3-4 cm from the tip in 2-week-old plants (n = 5 root sections). b, Quantification of Mn in DCB extract (n = 5 roots). DW, dry weight. In (a) and (b), data are shown as means ± SE and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. c-d, Roots in control (c) and excess iron (d) conditions used for LA-ICP-MS. Red arrowhead indicates root epidermis. Scale bars, 100 µm. e, Roots in control conditions. Scale bars, 2 cm. f, Radial oxygen loss (ROL) assay using methylene blue staining. The intensity of the blue corresponds ROL. Scale bars, 2 cm. Experiments were repeated at three (a, b, e) and two (c, d, f) independent times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Root and shoot phenotypes of psy2 mutants.

a-g, Measurement of root length (n = 10 roots) (a), root dry weight (n = 5 roots) (b), root number (n = 5 roots) (c), density of lateral roots (LRs) (n = 5 roots) (d), shoot length (n = 10 roots) (e), shoot dry weight (n = 5 roots) (f) and chlorophyll content (n = 5 shoots) (g). h-i, Iron content in roots (h) and shoots (i) (n = 4 biological repeats). Measurements were done in 3-weeks-old plants including excess iron treatment for a week. j, Iron content in brown rice cultivated in paddy field under waterlogging conditions (n = 5 biological repeats). All data are shown as means ± SE and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Overexpression of PSY2 in iron plaque and aerenchyma defective AZ1302-like-RIL line.

a, Plant morphology in tillering stage. Scale bars, 20 cm. b, Restoration of iron plaque in AZ1302-like RILs after overexpression (OE) of OsPSY2. Red arrowheads indicate iron plaque forming adventitious roots. Scale bars, 2 cm. c, Root aerenchyma (%) in AZ1302-like RILs and OE lines. Aerenchyma in 7 cm-long adventitious roots was measured at 1-2 cm, 3-4 cm and 5-6 cm from the tip (n = 4 root sections). d, Representative root cross section taken from a middle of a 7 cm-long adventitious roots demonstrating restoration of aerenchyma formation in PSY2-OE lines. Scale bars, 50 µm. e-h, Root length (n = 5) (e), root number (n = 5) (f), density of lateral roots (n = 3) (g), and shoot length (n = 5) (h) of OE lines. Measurements were done in 3-weeks-old plants including excess iron treatment for a week. In (c), (e), (f), (g) and (h), data are shown as means ± SE and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Experiments were repeated at three independent times (a-d) with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Analysis of OsPSY2 promoter activity in roots.

a-h, GUS staining of transgenic rice seedlings in whole roots (scale bars, 2 cm) (a), young adventitious roots (scale bars, 2 cm) (b), adventitious roots’ cross section (scale bars, 50 µm) (c), whole shoots (scale bars, 2 cm) (d), leaf sheath (scale bars, 2 mm) (e), leaf sheath’s cross section (scale bars, 50 µm) (f), panicle (scale bars, 2 cm) (g), and spikelet (scale bars,1 mm) (h). The experiment was performed in 3-weeks-old rice seedlings grown in ½ Kimura B solution or flowering stage. All experiments were repeated at three independent times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 8 ABA and strigolactone biosynthesis and Striga germination.

a, Involvement of phytoene synthase in carotenoid biosynthesis pathway that ultimately produce ABA and strigolactones. b, Root ABA content in Kitaake and psy2 mutants in 3-week-old plants grown under control conditions (n = 5). c, Quantification of zaxinone content (n = 6). d, Striga germination bioassay (n = 6). The GR24 was used as a positive control. Values represent means ± SE and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test in (b), (c) and (d).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Effect of ABA and GR24 treatment.

a-b, Iron plaque induction assay in Kitaake (a) and psy2-3 mutant (b) in response to ABA and (rac)-GR24 treatment. Red arrowheads indicate iron plaque forming adventitious roots. Scale bars, 2 cm. c, Aerenchyma (%) in response to ABA and (rac)-GR24 treatment in 5 cm-long adventitious roots of 2-week-old plants at 1-2 cm and 3-4 cm from the tip (n = 4 root cross sections). d, Aerenchyma (%) in response to (+)-GR24 treatment in 7 cm-long adventitious roots of 3-week-old plants at 3-4 cm and 5-6 cm from the tip (n = 4 root cross sections). In (c) and (d), data are shown as means ± SE and P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. e-g, Root length (e), root dry weight (f), and shoot length (g) in response to ABA and (rac)-GR24 treatment. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 5 roots). h-i, Root hair density (h) and Root hair length (i). Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 9 roots). Different letters in (e), (f) and (g) indicate significant differences at P < 0.05, as determined by two way analysis of variance followed by Tukey test. Measurements in (e), (f), (g), (h), and (i) were conducted in 3-week-old plants. Different letters in (h) and (i) indicate significant differences at P < 0.05, as determined by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn test.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Inhibition of aerenchyma and iron plaque formation via disruption of strigolactone biosynthesis/signaling and ABA signaling respectively.

a, Strigolactone (SL) biosynthesis and signaling pathway illustrating the role of D17, D10 and D14. b, Root length SL biosynthesis and signaling mutants. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 5 roots). P values were obtained using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. c, Aerenchyma (%) in 7 cm-long adventitious roots of 3-week-old SL mutants at 2-3 cm and 4-5 cm from the tip. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 15 root cross sections). P values were obtained using the Welch’s t-test. d, Representative root cross section demonstrating reduction in aerenchyma in SL mutants. Scale bars, 100 µm. e, Iron plaque induction in SL mutants. Scale bars, 1 cm. f, Inhibition of iron plaque formation in Kitaake roots in response to ABA Antagonist 1(AA1). Red arrowheads indicate iron plaque forming adventitious roots. Scale bars, 2 cm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data 1 and 2.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Fig. 5

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Source data for QTL mapping.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Source data for statistics and figures.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Source data for statistics and figures.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shrestha, J.K., Lin, CY., Wang, J.Y. et al. Carotenoid biosynthesis drives root plasticity through aerenchyma and iron plaque formation in rice. Nat. Plants 12, 179–190 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02170-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02170-y