Abstract

Many cellular functions rely on multiprotein complexes and their stoichiometric assembly. Reducing the levels of individual complex components can perturb this process and induce corrective stress responses. In addition to local outcomes, cellular stress in one tissue can induce long-distance responses in other tissues. Here, we used muscle-targeted RNAi to examine the systemic stress responses induced by muscle-specific genetic perturbation of four distinct multiprotein complexes: the sarcomere, mitochondrial respiratory complex I, proteasome, and VCP (valosin-containing protein) complex. Muscle-specific disruption of these four complexes produced largely overlapping transcriptional adaptations in the central nervous system (CNS), and these responses were centered on the upregulation of many proteases and peptidases. Testing in a retinal model of Huntington’s disease demonstrated that several stress-induced proteases limit the accumulation of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates during aging, indicating that these proteases protect from pathogenic proteins. We next examined whether the myokine Amyrel is a possible mediator of this stress-initiated muscle-to-CNS signaling because of its previously reported role in inducing protease expression. Consistent with this model, Amyrel expression was transcriptionally induced in muscle by perturbation of each of the four multiprotein complexes. Moreover, experimental upregulation of Amyrel in muscle reduced the amount of pathogenic huntingtin-polyQ aggregates in the retina. Taken together, these findings indicate that Amyrel and protective proteases improve CNS proteostasis following the perturbation of multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle. Thus, this study provides insight into a muscle-to-CNS signaling axis that conveys information on the stress status of multiprotein complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The activity of multiprotein complexes ensures many cellular functions1,2,3,4. Consequently, homeostatic systems have evolved to balance the stoichiometric expression and co-translation of protein complex components, their coordinated import into organelles and subcellular compartments, and their ordered assembly to form functional protein complexes5,6,7,8. Disruption of any of these steps leads to the accumulation of unassembled components and subcomplexes9,10, which can perturb proteostasis because of their instability in the unassembled state and interference with the function of other endogenous proteins11,12,13,14,15.

Several stress responses can be induced by disruption of multiprotein complexes and mitigate specific insults to proteostasis16. For example, RNAi for components of mitochondrial complex 1, one of the largest cellular complexes (~45 components)17, leads to defective complex assembly and the consequent induction of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt)18,19. This stress response maintains proteostasis by inducing the expression of mitochondrial proteases and chaperones that prevent the interaction of misfolded unassembled proteins with native mitochondrial proteins and/or promote their degradation20,21,22. Whereas the UPRmt responds to the specific needs of maintaining proteostasis within mitochondria, equivalent unfolded protein responses guard proteostasis in the cytoplasm (heat shock response, UPR) and the endoplasmic reticulum (UPRER)16,23. Apart from these well-known stress responses, different adaptive and maladaptive changes are induced when other cellular functions or compartments are perturbed. For example, besides the broadly-acting integrated stress response24, tailored responses have been described following the perturbation of lysosomes25, components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system26,27,28,29,30, ribosomes31, peroxisomes32, the nuclear and plasma membranes33,34,35, the nucleolus36,37, and the Golgi apparatus38. In summary, many specialized responses are induced by the targeted perturbation of diverse cellular components.

In addition to local effects, homeostatic systems that monitor cellular fitness can also mount systemic responses that lead to consequent adaptations in other tissues39,40,41,42. For example, perturbation of proteostasis in germline stem cells influences the organization of mitochondria and the aggregation of pathogenic proteins in somatic tissues in C. elegans43. Although the systemic induction and propagation of stress responses likely represent a general phenomenon that invests all tissues, some tissues/organs have emerged for their capacity to trigger systemic stress signaling. Among them, skeletal muscle influences organismal behaviors, aging, and metabolism via muscle-released signaling factors known as myokines44,45,46,47,48, which can be induced by exercise but also in response to cellular stress and nutrients49,50,51,52,53. Several myokines that signal to the brain were previously found to cross the blood brain barrier (e.g., IL6) whereas others may indirectly benefit the brain by signaling to the brain endothelium (e.g., GDF11)44,45,46,47,48.

Unique features of skeletal muscle that may underlie its contribution to inter-tissue crosstalk are its contractile capacity and the resulting mechanical stress54,55,56,57, which is a prominent driver of protein misfolding and perturbation of proteostasis58,59,60,61,62. In agreement with this view, experimental interventions that challenge muscle proteostasis were found to induce systemic stress responses that regulate protein quality control across tissues27. For example, proteasome stress in skeletal muscle induces the expression of the amylase enzyme Amyrel, which increases the circulating levels of maltose, a disaccharide that can act as a chemical chaperone and as a signaling molecule27. Muscle-specific induction of Amyrel improves proteostasis in the brain and retina during aging, and this action depends on the transcriptional induction of protective chaperones and proteases via maltose transporters of the SLC45 family27. Interestingly, maltose preserves proteostasis and neuronal function also in human brain organoids27, suggesting that its neuroprotective function could be conserved in humans. Another example of muscle-initiated stress signaling consists of the observation that expression of a misfolding-prone protein in skeletal muscle leads to systemic upregulation of the chaperone Hsp90 in C. elegans63. However, it is only partly understood how such systemic stress responses originating from skeletal muscle can influence organismal aging and the progression of age-related degenerative diseases in other tissues.

Here, we utilized Drosophila skeletal muscle to define the stress responses induced by genetic perturbation of distinct molecular complexes, and for assessing the systemic impact of muscle stress signaling. Surprisingly, we find that a conserved stress response is induced locally in muscle and systemically in the central nervous system (CNS) following the perturbation of multiprotein complexes located in distinct subcellular compartments and organelles of skeletal muscle. This long-distance adaptive signaling relies on the transcriptional induction of several proteases and peptidases, many of which can degrade pathogenic proteins. Moreover, we identify Amyrel as a secreted factor that is commonly induced by RNAi for components of different multiprotein complexes and that improves proteostasis in the central nervous system (CNS). Altogether, our study elucidates a long-range muscle-to-CNS signaling axis that communicates information regarding the status of multiprotein complexes.

Results

Muscle-specific RNAi for components of diverse multiprotein complexes triggers a largely overlapping transcriptional response in skeletal muscle which is centered on protease induction

To determine the local stress responses induced by perturbation of multiprotein complexes, we have used the UAS/Gal4 system and transgenic RNAi to target core components of key protein complexes in Drosophila skeletal muscle (Fig. 1a). Specifically, the following complex components were knocked down via RNAi: Prosβ5 (homologous to human PSMB5, proteasome 20S subunit beta 5), which is part of the catalytic core of the proteasome64,65,66; VCP (also known as Ter94 in Drosophila), which is mutated in inclusion body myopathy and is a core constituent of the VCP complex necessary for ERAD (endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation) and for the degradation of subunits of multiprotein complexes67,68,69; ND-75 (homologous to human NDUFS1), which is a component of the mitochondrial respiratory complex 1, one of the largest multiprotein complexes10,17; and tropomyosin 1, which is a contractile protein of the sarcomere70.

a RNA-seq from thoraces (which consist primarily of skeletal muscle) and heads (which are enriched for the CNS, i.e. retinas and brains) from flies with muscle-specific perturbation of multiprotein complexes, obtained via transgenic RNAi for key complex components, i.e. Prosb5 for the proteasome, VCP/TER94 for the VCP complex, ND-75 for complex I of the electron transport chain, and tropomyosin 1 (Tm1) for the sarcomere. For each condition, n = 3 biological replicates (each consisting of tissues from ~30 male flies per sample) were compared to a control GFPRNAi. All RNA-seq samples were normalized by control whiteRNAi. Muscle-specific perturbation of multiprotein complexes was obtained by driving the transgenic RNAi lines in skeletal muscle by using the Mhc-Gal4 driver. See also Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Dataset 1. b Overview of the Gene Ontology (GO) categories that are consistently over-represented among the genes that are significantly upregulated and downregulated in skeletal muscle following muscle-specific Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi but not GFPRNAi. Proteolysis (corresponding to proteases and peptidases) is the main common category that is consistently upregulated in response to RNAi for components of multiprotein complexes. See also Supplementary Fig. 2. c qRT-PCR validation of target gene knockdown (mean ± SEM and n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, unpaired two-tailed t-test) and volcano plots that display the gene expression changes induced in skeletal muscle in response to RNAi-mediated perturbation of multiprotein complexes. The x-axis reports the log2 fold changes in stressRNAi vs. control whiteRNAi whereas the y-axis reports a significance score, i.e.-log10(P-value). Proteases (red) regulated with logratio > 1 and P < 0.05 (but having P < 0.01 for at least one of the genotypes) are indicated (the same proteases are also shown in the GFPRNAi plot although not significantly regulated by GFPRNAi). d Regulation of protease clans, as retrieved from the MEROPS database. The average protease gene logratio is indicated for all proteases in each clan for each RNAi intervention, control GFPRNAi, and on average for the stress-inducing RNAi interventions (Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi). All Drosophila proteases listed in the MEROPS database were considered for this analysis. e Proteolysis (i.e., proteases and peptidases) is the GO category that is consistently over-represented among upregulated genes in the CNS in response to muscle-specific Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi but not GFPRNAi. See also Supplementary Fig. 2. f Volcano plots that display the gene expression changes induced in the CNS in response to muscle-specific Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi. Proteases (red) regulated with logratio > 1 and P < 0.05 (but having P < 0.01 for at least one of the genotypes) are indicated (the same proteases are shown for GFPRNAi albeit not significantly regulated). g The average gene expression increases for several protease clans in the CNS in response to muscle-specific Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi (but not GFPRNAi). The differential regulation of aspartic, cysteine, metallo, mixed-type, and serine proteases is indicated.

For these studies, a Mhc-Gal4 line that drives transgenic UAS-RNAi expression specifically in skeletal muscles was used71, and knockdown of the levels of the target mRNAs was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1a–c). Subsequently, RNA-seq of Drosophila thoraces (which consist primarily of skeletal muscle) determined the transcriptional changes associated with RNAi-mediated perturbation of the components of multiprotein complexes listed above. We also analyzed the transcriptional changes induced by a control GFPRNAi, and the RNA-seq resulting from each RNAi intervention was normalized to a control whiteRNAi (Fig. 1b, c).

Significant transcriptional changes (P < 0.05) were cross-compared to determine the degree of similarity and differences in the stress responses induced by RNAi for different complex components. This analysis pinpointed an unanticipatedly high similarity in the transcriptional changes triggered by the knockdown of different complex components (located in distinct cellular compartments) but not by a control GFPRNAi. Specifically, ND-75RNAi, which induces the UPRmt 19, led to transcriptional changes that are highly related (r = 0.90) to those induced by Prosβ5RNAi, which induces proteasomal stress27. RNAi for the sarcomeric protein Tropomyosin 1 (Tm1) also led to similar transcriptional changes as found in response to ND-75RNAi and Prosβ5RNAi (r > 0.87). Likewise, the transcriptional stress response induced by Ter94/VCPRNAi was overall related (albeit to a lower extent, r = 0.51–0.57) to that induced by ND-75RNAi, Prosβ5RNAi, and Tm1RNAi. Conversely, there was a lower or minimal correlation between the gene expression changes induced by Tm1RNAi, Ter94/VCPRNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Prosβ5RNAi vs. those induced by control GFPRNAi (r = 0.09–0.36) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Next, we examined the gene ontology (GO) categories that are modulated by the perturbation of multiprotein complexes. Several categories were enriched among the genes significantly modulated by Tm1RNAi, Ter94/VCPRNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Prosβ5RNAi but not by GFPRNAi (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, GO categories that were concordantly modulated by different RNAi interventions included regulators of proteolysis, hormone binding, and lipase activity for upregulated genes, whereas lipid synthesis was consistently enriched among the genes that are significantly downregulated by Tm1RNAi, Ter94/VCPRNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Prosβ5RNAi but not by GFPRNAi (Fig. 1b, c).

Proteolysis was the major GO term that was enriched among upregulated genes: this category consisted primarily of proteases and peptidases. On this basis, we next examined whether protease modulation is part of the transcriptional response to RNAi for components of multiprotein protein complexes and found it to be the case. Specifically, several proteases/peptidases were significantly upregulated by RNAi for Prosβ5, VCP, ND-75, and Tm1 (normalized by control whiteRNAi) but not by GFPRNAi (Fig. 1c). These results therefore indicate that protease induction is a common response induced by perturbation of different multiprotein complexes. We next examined whether specific clans of proteases (as classified by the MEROPS database72,73) are differentially modulated by stress. Analysis of the average protease gene regulation (log2 fold-changes for all members of each protease clan) indicates that proteases from diverse families are transcriptionally upregulated by perturbation of multiprotein complexes, with higher average expression detected for metalloproteases and mixed-type proteases, whereas aspartic, cysteine, and serine proteases are less modulated (Fig. 1d).

Altogether, these analyses indicate a convergence in the transcriptional stress responses induced in muscle by RNAi for components of different multiprotein complexes located in distinct cell compartments. Specifically, similar gene expression changes (including protease/peptidase upregulation) were caused by targeting complexes located in the nucleus and cytoplasm (proteasome), endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (VCP complex), mitochondria (respiratory complex 1), and the cytoplasm (sarcomere). In summary, these analyses indicate a remarkable similarity in the gene expression changes induced by perturbation of different molecular complexes (Fig.1, Supplementary Dataset 1, and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2), including the induction of proteases that belong to several classes.

Muscle-specific RNAi for components of diverse multiprotein complexes induces long-distance transcriptional upregulation of proteases in the CNS

Several studies in model organisms indicate that local perturbation of homeostasis in one tissue leads to the induction of a stress response not only locally but also systemically in distant tissues39,40,41,42. To this purpose, we have examined the transcriptional changes in the heads (which are enriched for CNS tissues, i.e. retinas and brains) of flies with muscle-specific perturbation (obtained via RNAi) of multiprotein complexes (Fig. 1e, f and Supplementary Dataset 1).

GO terms that were enriched among the upregulated genes included proteolysis and associated categories (peptidase S1 and carboxypeptidase) and also chitin metabolism and metal-binding (Fig. 1e). Collectively, this transcriptional profiling indicates that the induction of proteases and peptidases is a core response that is commonly induced by the muscle-specific perturbation of multiprotein complexes not only locally in muscle but also distantly in the CNS (Fig. 1f). Specifically, further analyses indicate that several proteases and peptidases are transcriptionally induced in the CNS by muscle-specific Prosβ5RNAi, Ter94/VCPRNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi but not by control GFPRNAi. Analysis of the protease clans that are most highly modulated in the CNS indicated a partially divergent response compared to skeletal muscle (Fig. 1g). In particular, while mixed-type proteases were the clan most highly induced on average in both skeletal muscle and the CNS, metalloproteases were highly induced in the muscle but not in the CNS and, conversely, aspartic proteases were induced in the CNS but not in muscle (Fig. 1d, g). Collectively, these findings indicate that both local and systemic transcriptional responses induced by the perturbation of multiprotein complexes in muscle are centered on the induction of proteases.

RNAi screening indicates a protective role for some stress-induced proteases in the degradation of a model aggregation-prone protein (huntingtin-polyQ) in the retina

Proteases and peptidases constitute a superfamily of proteins that localize to different organelles and compartments74,75. Mitochondrial proteases have important roles in mitochondrial proteostasis74,75 whereas cytosolic proteases maintain protein quality control during aging76 and can partially compensate for proteasome dysfunction77,78,79,80. Proteases can also degrade pathogenic proteins, as found for the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (Psa), which degrades mutant tau81 and pathogenic huntingtin with polyglutamine tract expansion which causes Huntington’s disease82,83. However, other proteases can promote neurodegeneration by generating huntingtin and tau fragments with increased pathogenicity84,85,86,87.

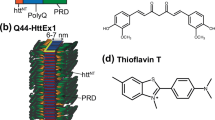

On this basis, we have used a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease88 to determine whether the proteases that are induced in the CNS upon muscle-specific stress constitute a pathogenic or, conversely, a protective response that degrades a model aggregation-prone protein, i.e. huntingtin with poly-glutamine expansion. Specifically, 235 RNAi lines targeting 77 stress-induced proteases and controls were driven with the UAS/Gal4 system and the GMR-Gal4 driver in Drosophila retinas that express Htt-Q72-GFP (Fig. 2a), a GFP-tagged exon 1 of huntingtin with poly-glutamine expansion88,89, which is a known target of proteases82,83. Previous studies with this model reported the progressive, age-dependent accumulation of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates that can be optimally examined after aging for 30 days at 29 °C76,88,90,91. On this basis, the average area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates was quantified for each RNAi at this timepoint by using CellProfiler, starting from fluorescence images obtained from 5 retinas of 5 distinct flies. Subsequently, we examined the z-score (which indicates the deviation of each RNAi from the cumulative mean of all values) to identify RNAi interventions that substantially differ (either by increasing or decreasing) the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates compared to the other RNAi interventions. Because we utilized RNAi lines from different collections that may differ in their genetic background, we examined separately the results obtained from the screen of RNAi lines from the BDSC (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center), NIG (Japanese National Institute of Genetics), and the GD and KK collections from the VDRC (Vienna Drosophila Resource Center). Global representation of the RNAi screen data indicated that several proteases greatly affected the Htt-Q72-GFP aggregate area, with some RNAi lines increasing and others decreasing Htt-polyQ aggregates (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Dataset 2). For example, compared to control mcherryRNAi, knockdown of εTry (homologous to the human serine proteases PRSS1/2/3) increased the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates, indicating that this protease normally contributes to the degradation of pathogenic Htt-polyQ. Conversely, RNAi for yip7 (homologous to the human chymotrypsin proteases CTRB2 and CTRL) reduced the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates, indicating that this protease has an opposite role, i.e. normally promotes the accumulation of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates (Fig. 2b). While this RNAi screen uncovered proteases that increase and others that decrease the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates, the phenotypes observed following protease knockdown were more striking for interventions that increased huntingtin-polyQ aggregates. Specifically, by applying a z-score cut-off of −3.5 and +3.5, there was only 1 protease knockdown (yip7RNAi) that reduced the area of protein aggregates with z-score < −3.5, whereas there were 27 proteaseRNAi that increased the area of protein aggregates with z-score > +3.5. Comparison to negative controls for each RNAi collection (i.e., mcherryRNAi, vRNAi, and yRNAi) further confirmed that RNAi for these proteases increases the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates (apart from yip7RNAi, which decreases it), as also observed with PsaRNAi (Fig. 2c, d), which is used as positive control because Psa knockdown was previously found to impede the degradation of pathogenic huntingtin in mice82,83 and Drosophila76. Although it is well known that not all RNAi lines work efficiently in Drosophila92, in some cases there were multiple RNAi lines from different collections targeting the same gene that acted consistently, i.e. increased the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates: this was the case for the knockdown of CG8560 (3 lines), Jon25Bi (3 lines), Jon25Biii (3 lines), and CG17109 (2 lines). Importantly, these and the other proteases that strikingly affected the area of huntingtin-polyQ (Fig. 2c, d) are evolutionarily conserved (Supplementary Dataset 3), suggesting that they may also play a role in the degradation of pathogenic huntingtin in humans. In summary, RNAi screening of stress-induced proteases identifies a predominant role of these proteases in reducing the accumulation of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates, as inferred from the observation that their knockdown increases the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates.

a Outline of the experimental strategy that was utilized to test the function of stress-induced proteases. Female flies that express an aggregation-prone pathogenic Htt-Q72-GFP in the retina with GMR-Gal4 were crossed with 235 RNAi lines targeting 77 proteases that are induced in the CNS by perturbation of multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle (Fig. 1). During aging (e.g., from 2 to 30 days), there is a progressive accumulation of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates in the Drosophila retina. Imaging of GFP specks in the eyes from 5 flies/group at 30 days is followed by automated image analysis to quantify the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates. See also Supplementary Datasets 2–3. b Overview of the RNAi screen results. The area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates for each RNAi intervention is displayed based on its divergence from the mean values of the population (z-score). The results obtained with RNAi lines from different collections (BDSC, NIG, VDRC GD and KK) are presented separately. Knockdown of stress-induced proteases in the retina indicates that several proteases influence the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates. However, with a threshold of −3.5 and +3.5 z-scores, there is only one proteaseRNAi (yip7RNAi) that reduces huntingtin-polyQ aggregates whereas many proteaseRNAi interventions increase Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates (e.g., εTryRNAi) compared to controls (e.g., mcherryRNAi), indicating that these stress-induced proteases are necessary to preserve protein quality control. Z-scores (c) and fold changes (d) in the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates. The most striking proteaseRNAi interventions are displayed alongside negative controls (mcherryRNAi, vRNAi, yRNAi) and positive controls (PsaRNAi). The graph in (d) displays the mean ± SEM with n = 5 retinas/group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). See also Supplementary Dataset 4.

Protective stress-induced proteases reduce oligomeric huntingtin-polyQ in the retina

Western blot is a common method to examine huntingtin-polyQ aggregation. In particular, previous studies reported that Htt-Q72-GFP is detected as a monomer in both detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions but also as insoluble oligomers/aggregates that accumulate in the stacking gel76,88,91. On this basis, we next utilized western blots to analyze the detergent-soluble and detergent-insoluble fractions obtained from 30 heads/sample of flies that express Htt-Q72-GFP in the retina concomitantly with RNAi for a protective stress-induced protease or controlRNAi. Probing with anti-GFP antibodies identified Htt-Q72-GFP monomers (~55 kDa, that were detected in both the soluble and insoluble fractions) and high-molecular-weight oligomers/aggregates (>250 kDa), which were detected in the stacking part of the gel utilized for the analysis of insoluble fractions. In addition, myosin was utilized as a loading control.

Consistent with findings from previous studies76,82,83, PsaRNAi driven concomitantly with Htt-Q72-GFP in retinas increased the amount of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates detected in the stacking gel relative to the control mcherryRNAi (Fig. 3a, b). Comparable outcomes were observed via the western blot analysis of detergent-insoluble fractions derived from fly heads with RNAi targeting stress-induced proteases (Fig. 3a, b), which also displayed an increase in huntingtin-polyQ aggregates as evidenced by microscopy (Fig. 2). Specifically, most RNAi lines targeting stress-induced proteases increased the insoluble levels of Htt-Q72-GFP protein oligomers/aggregates that are not resolved by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3a, b), whereas the soluble and insoluble levels of monomeric Htt-Q72-GFP were typically not affected. However, the knockdown of yip7/CG6457 reduced the levels of insoluble Htt-Q72-GFP monomers and aggregates (Fig. 3a, b), consistent with the immunofluorescence analysis that indicates that Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates decrease in response to yip7RNAi (Fig. 2c, d). Together, these results indicate that proteases induced in the CNS in response to muscle-specific stress largely consist of protective proteases that can degrade a model aggregation-prone protein, i.e. Htt-Q72-GFP.

a Western blots of detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions from heads of 30-day-old flies that express Htt-Q72-GFP in the retina concomitantly with either a proteaseRNAi or a controlRNAi. Probing with anti-GFP antibodies indicates that GFP-tagged huntingtin-polyQ is detected as a monomer (~60 kDa) in detergent-soluble fractions, and both as a monomer and as high-molecular-weight oligomers/aggregates (>250 kDa; detected in the stacking gel) in insoluble fractions. Myosin is utilized as loading control; around 30 heads per sample were employed for these analyses. b Quantitation indicates that knockdown of most of these stress-induced proteases increases the amount of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates; mcherryRNAi and PsaRNAi were utilized as negative and positive controls, respectively. The full scans of western blots are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

The myokine Amyrel is induced in muscle by perturbation of multiple multiprotein complexes and reduces Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates in the retina

We previously found that induction of proteasome stress in muscle increases the levels of several secreted factors (i.e., myokines), including the amylase Amyrel, which in turn promotes protein quality control in the brain and retina during aging via maltose/SLC45 signaling and the transcriptional upregulation of chaperones and proteases27.

Considering the important role of this stress-induced muscle-secreted factor in systemic signaling and its capacity to increase protease expression in the CNS27, we next examined whether Amyrel is generally induced by perturbation of additional multiprotein complexes apart from the proteasome. To this purpose, we examined the RNA-seq data (Fig. 1) and determined that Amyrel expression increases in skeletal muscle in response to knockdown of Prosβ5, VCP, ND-75, and Tm1 compared to control whiteRNAi and GFPRNAi and to no transgene expression (Fig. 4a). These findings indicate that Amyrel is transcriptionally induced by the RNAi-mediated perturbation of multiple multiprotein complexes.

a Amyrel mRNA levels (FPKM levels) increase in skeletal muscles upon knockdown of components of multiprotein complexes (Prosb5RNAi, VCP/TER94RNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi) compared to controls (GFPRNAi, whiteRNAi, and no transgene). For each condition, n = 3 biological replicates (each consisting of tissues from ~30 male flies per sample) were examined. The graph displays the mean ± SEM. P-values (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) were obtained from the statistical analysis of RNA-seq data. b Epifluorescence imaging of flies with CD2-GFP expression driven by Mhc-LexA-GAD indicates that this line drives transgene expression specifically in skeletal muscle and not in the retina and brain. c qRT-PCR analysis of Amyrel mRNA levels in response to LexA-responsive Amyrel transgene expression (green) induced by Mhc-LexA-GAD compared to controls (gray). The graph displays the mean ± SD and n = 3 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 (unpaired two-tailed t-test). d Analysis of aggregates of GFP-tagged huntingtin-polyQ in the retinas of flies at 30 days of age. Expression of the UAS-Htt-Q72-GFP transgene is driven in the retina with GMR-Gal4, whereas an independent binary expression system (LexA/LexAop) is utilized to induce Amyrel expression in skeletal muscle with the Mhc-LexA-GAD driver. This analysis indicates that Amyrel induction in skeletal muscle (green) reduces the accumulation of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates in the retina compared to isogenic controls (gray). The graph displays the mean ± SEM and n = 24 and n = 37 retinas, respectively; **P < 0.01 (unpaired two-tailed t-test).

On this basis, and because of the known role of Amyrel in upregulating the expression of protective proteases in the CNS27, we next examined whether Amyrel induction in skeletal muscle can influence Htt-Q72 aggregation in the retina. Because the Htt-Q72-GFP transgene is driven in the retina via the UAS/Gal4 system93, we generated tools for transgenic expression in skeletal muscle with another binary expression system, i.e. the LexA/LexAop94. Specifically, we utilized a ~4.4 kb Mhc promoter sequence to generate a Mhc-LexA-GAD fly line, which expresses the transcriptional activator LexA-GAD specifically in the thoracic flight muscle but not in the brain or retina, as evidenced by monitoring the fluorescence of a LexA-responsive transgene that expresses CD2-GFP (Fig. 4b). On this basis, we next utilized Mhc-LexA-GAD to drive Amyrel expression in skeletal muscle (with the LexA-responsive LOT-Amyrel) while concomitantly driving Htt-Q72-GFP expression in the retina with the UAS/Gal4 system. In response to Amyrel upregulation in skeletal muscle (as assessed by qRT-PCR, Fig. 4c), there was a significant decline in the area of Htt-Q72-GFP aggregates in the retina (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these results indicate that Amyrel is a muscle-derived signaling factor that contributes to the reduction of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates in the retina in response to the perturbation of multiple multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Proteases are one of the largest superfamilies in the human genome, and its >600 members play important roles in regulating cell function and in maintaining homeostasis across cell compartments95,96. Following the discovery of bacterial proteases and related mitochondrial proteases that preserve mitochondrial function in higher organisms97, subsequent studies have demonstrated important signaling functions of proteases in many other cell compartments74,75,95. Moreover, proteases contribute to preserving protein quality control during aging76 and to regulating most (if not all) aspects of aging75. As part of these important processes, proteases were found to cooperate with other proteolytic systems (i.e., the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome systems) in degrading misfolded and aggregation-prone proteins and for compensating for a decline in proteasome function77,78,79,80.

In a previous study, we found that moderate perturbation of proteasome function in skeletal muscle (via RNAi for components of the catalytic core of the proteasome) induces a local proteasome stress response that, via C/EBP transcription factors, maintains muscle proteostasis via the transcriptional upregulation of proteases27. Interestingly, a long-distance stress response is also elicited in the brain and retina following the muscle-specific perturbation of the proteasome, and such systemic response (mediated by the myokine Amyrel) preserves CNS proteostasis during aging via the upregulation of chaperones and protective proteases in neurons27,50.

Besides proteasome stress, other types of unfolded protein responses (UPRs; and more generally stress responses) are known to be activated following specific insults to organelle function16. These specialized stress responses implement tailored adjustments to re-establish cellular homeostasis or rewire cellular function as a coping mechanism16. Despite the diverse outcomes that are induced by each specialized stress response16, disrupting different parts of the same pathway (like the ubiquitin-proteasome system) can also activate diverse responses viz., the proteasome stress response (boosting proteasome gene expression), the ubiquitin stress response (maintaining free ubiquitin levels), and the UBA1/E2 stress response28, which boosts peroxisomal protein import (a process that critically relies on ubiquitination) in cells in which there are lower levels of the initiating components of the ubiquitination cascade (i.e., the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBA1 and E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes)26. Therefore, a unifying general principle of stress responses is the specific induction of tailored adaptive and maladaptive changes that are consequent to the original insult.

In this manuscript, we have examined the transcriptional changes that are induced locally in skeletal muscle and systemically in the CNS following the genetic RNAi-mediated perturbation of different multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle. Apart from the proteasome, we have targeted components of the VCP complex, mitochondrial complex I, and the sarcomere and found that, despite differences in the categories of modulated genes, there is a common upregulation of proteases in response to these diverse insults (Fig. 1). Specifically, proteases and peptidases (i.e., “proteolysis” GO term) constitute the top category that is upregulated by Prosβ5RNAi, VCPRNAi, ND-75RNAi, and Tm1RNAi but not by control GFPRNAi. Interestingly, the transcriptional upregulation of distinct proteases occurs in skeletal muscle and the CNS, indicating that both local and systemic responses are induced following the perturbation of multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle (Fig. 1). Therefore, these results indicate that knockdown of core components of distinct multiprotein complexes triggers a similar stress response, which is centered on protease induction both cell-autonomously and cell-non-autonomously.

The similar trend of protease upregulation that is observed following the perturbation of different multiprotein complexes is at odds with the specialized transcriptional responses that are typically observed following distinct challenges16. Possibly, protease induction may commonly occur in response to the perturbation of distinct multiprotein complexes because knockdown of complex components may impair the assembly (or challenge the stability) of multiprotein complexes. In turn, this could lead to the accumulation of unassembled complex subunits, which may also be prone to misfolding in their unassembled state. In this condition, the burden for the proteasome would increase and result in the induction of compensatory mechanisms. While we did not observe transcriptional upregulation of proteasome components (a stereotypical response to proteasome inhibition)28, proteases were previously found to compensate for the proteasome77,78,79,80 and therefore may provide a mechanism for impeding the accumulation of unassembled complex components that are prone to misfolding.

To test the hypothesis that stress-induced proteases are indeed protective, we examined their capacity to degrade an aggregation-prone protein, huntingtin-polyQ. Interestingly, previous studies had demonstrated that the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (Psa) can protect from Huntington’s disease by promoting the degradation of huntingtin-polyQ by acting in cooperation with the ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome systems82,83. In line with these previous studies, Psa is also protective in Drosophila, where it reduces the amount of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates and heterogeneous aggregates of insoluble poly-ubiquitinated proteins76. Our analysis indicates that many of the proteases that are induced by muscle stress are protective in the CNS. Specifically, knockdown of these proteases increases the age-related accumulation of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates, as evidenced by microscopy and biochemical analyses (Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, these findings suggest that protease induction may represent a backup mechanism to cope with the accumulation of unassembled and therefore misfolding-prone complex components. Apart from pathogenic huntingtin, it is possible that stress-upregulated proteases may also protect against other aggregation-prone proteins such as mutant tau.

Interestingly, this response is induced not only locally in muscle but also systemically in the CNS, even though the original insult (i.e., knockdown of components of multiprotein complexes) is confined to skeletal muscle. Presumably, this systemic stress response is part of an organismal adaptation that senses a challenge in a tissue (skeletal muscle) and forecasts that the same challenge may spread to or occur in other tissues (such as the CNS). On this basis, this systemic control mechanism induces an adaptive stress response outside of the tissue where the original insult was located, presumably to instigate protective mechanisms that can impede cellular damage and loss of homeostasis once the challenge spreads or occurs in a distant tissue or organ. Interestingly, cellular stress (including various forms of unfolded protein responses similar to those that were induced experimentally in this study)58,59,60,61,62 physiologically occurs in skeletal muscle in response to contraction98,99. Exercise is indeed a major metabolic and mechanical challenge for many muscle cell compartments and associated multiprotein complexes54,55,56,57, such as the mitochondria and sarcomere, but also for the proteasome and VCP complex that are tasked with extracting and replacing damaged components of the sarcomere and ER, and for general protein turnover and proteostasis67,68,69. Therefore, the protective systemic stress response observed in this study may physiologically occur during muscle contraction and related processes and may provide a basis for understanding why exercise protects from the onset and progression of many diseases that affect the CNS100,101. Interestingly, some proteases can have protective roles in neurodegeneration by degrading pathogenic proteins or by modulating signaling pathways that protect from neurodegeneration, but others can conversely aggravate disease pathogenesis by generating protein fragments with increased toxicity75. Therefore, a key outcome of perturbing multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle is the reshaping of protease expression that occurs in the CNS, which leads to a protective profile that can reduce neurodegeneration. Proteases may also contribute to the systemic transmission of information from skeletal muscle to the brain during exercise. In particular, exercise induces the expression and secretion of the lysosomal protease cathepsin B, which is needed for improving neurogenesis in the CNS following exercise in mice and humans102. Therefore, proteases may play important roles in skeletal muscle (to adapt the local proteostasis to the mechanical stress and protein unfolding associated with exercise), in the brain (to anticipate a stress response for a forthcoming insult), and even in transmitting such information from skeletal muscle to the brain, as observed for cathepsin B.

However, multiple muscle-secreted factors (i.e., myokines) are remodeled by muscle cell stress and exercise51,52, and may therefore play a role in muscle-to-brain signaling and in inducing protective protease expression in the CNS. We previously found an important role of the amylase enzyme Amyrel and the ensuing maltose/SLC45 maltose transporter signaling in preserving protein quality control in the brain and retina in response to proteasome stress in skeletal muscle27. Since protease induction in the CNS is a key outcome of Amyrel/maltose/SLC45 muscle-to-brain signaling27, here we tested whether Amyrel is induced by perturbation of multiple multiprotein complexes and found it to be the case (Fig. 4). Furthermore, experimental upregulation of Amyrel in muscle reduces huntingtin-polyQ aggregates in the retina (Fig. 4), indicating that Amyrel is a muscle-derived signal that transmits information on the status of multiprotein complexes from skeletal muscle to the brain. While SLC45 maltose transporters are primarily expressed in neurons, scRNA-seq data indicate that they are also expressed in subsets of glial cells (Supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting that this pathway may regulate proteostasis in other cell types in the brain apart neurons.

A muscle-to-CNS signaling axis is initiated by perturbation of multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle and induces protective proteases that degrade a model aggregation-prone protein (huntingtin-polyQ) in the central nervous system (CNS). This muscle-to-brain communication is mediated at least in part by the myokine Amyrel.

In summary, we have identified a local and systemic stress response resulting in the upregulation of protective proteases and that is commonly induced by knockdown of components of multiple multiprotein complexes (Fig. 5). Many of the stress-induced proteases protect from the accumulation of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates in the retina, suggesting that this systemic stress response may prevent neurodegenerative diseases. The evolutionarily conserved myokine Amyrel contributes to this muscle-to-brain signaling and decreases disease progression in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease. Together, these findings indicate that diverse insults on protein homeostasis result in an unexpected convergence in the induction of protective proteases, suggesting that this response might be harnessed to improve proteostasis and reduce neurodegeneration.

Methods

Fly husbandry and fly stocks

Flies were maintained at 25 °C with 60% humidity under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle in tubes containing cornmeal/soy flour/yeast-based food. The food was replaced every 2–3 days. All experiments were conducted using male flies. The fly stocks utilized in the RNAi screen are reported in Supplementary Dataset 2 and were obtained (as indicated) from the BDSC (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, BL#), NIG (Japanese National Institute of Genetics), and the GD and KK collections from the VDRC (Vienna Drosophila Resource Center, v#). Additional fly stocks that were utilized include the following: GFPRNAi (BL#41552), whiteRNAi (BL#33623), Prosb5RNAi (BL#34810), ND-75RNAi (BL#33911), Tm1RNAi (BL#38232), TER94/VCP RNAi (#v24354), pLOT-CD2-GFP94, GMR-Gal4;UAS-HttQ72-GFP88, and Mhc-Gal445,71. Schemes were drawn with BioRender.

Analysis of huntingtin-polyQ aggregates

For the RNAi screen, 20 GMR-Gal4;UAS-Htt72Q-GFP virgin females were mated with 5 UAS-RNAi male flies. Male progenies were collected and reared at 25 °C (25 flies/tube) until ready for imaging at 30 days post-eclosion. At this age, pathogenic huntingtin-72Q-GFP protein aggregates were visualized by using a Zeiss SteREO Discovery.V12 epifluorescence microscope under consistent exposure time and imaging settings. Grayscale images of entire retinas were captured and subsequently analyzed using CellProfiler 3.0.0 (cellprofiler.org103) with an automated pipeline to quantify the total area of protein aggregates (huntingtin-polyQ speckles). All analyses were performed on male flies aged for 30 days at 25 °C, with identical conditions applied to all experimental and control groups within each experiment. The accumulation of huntingtin-72Q-GFP protein aggregates occurs progressively during aging, as previously demonstrated76. The results from each experimental group were compared to those of the corresponding negative control RNAi line from the same RNAi stock collection. Specifically, data from Bloomington RNAi stocks were compared to mcherryRNAi (BL#35785), and RNAi lines for the germline-specific tbrd-1 and tbrd-3 genes were utilized as additional controls (BL#55658 and BL#63672). An RNAi line (BL#36764) for the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (Psa) was utilized as a positive control, as previously done76. RNAi lines from the NIG-Fly collection were compared to vermillionRNAi from the same collection (#2155R-2). The VDRC RNAi stocks from the GD and KK sets were compared to vermilionRNAi (vRNAi, #v3349) and to yellowRNAi (yRNAi, #v106068), respectively.

Establishment of Mhc-LexA-GAD and pLOT-Amyrel fly strains

The Mhc-LexA-GAD construct was obtained by utilizing the previously reported plasmid for LexA-GAD expression94 and a ~4.4 kb promoter (2 L:16764289,16768681) upstream of Mhc, a region that includes the 5’-UTR and that partially corresponds to the Mhc promoter region used in previous studies104,105. The pLOT plasmid94 was used to clone the Amyrel coding sequence downstream of the LexA-GAD responsive sequence LexAop. The plasmids were injected into the w1118 background to obtain transgenic flies.

Preparation of detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions

Detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions were prepared according to the procedures that were previously described90,91,106. Specifically, heads were dissected from 30 male flies per sample and homogenized in a bullet blender with 0.5-mm zirconium oxide beads (Next Advance #ZROB05) for 5 min in 100 µL ice-cold PBS (Gibco, #10010023) with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, #X100-5ML) containing protease inhibitors (Roche, #11697498001) and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, #4906845001). The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min and 90 µL supernatant was collected for each sample (detergent-soluble fraction). The remaining pellet was washed in 400 µL ice-cold PBS with 1% Triton X-100 through two rounds of centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, the pellets were resuspended in 100 µL RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, #9806) containing 8 M urea (Sigma, #U5378) and 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Sigma, #L4509) and homogenized for 5 min. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min and 90 µL supernatant was collected (detergent-insoluble fraction).

Western blot analysis of detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions

Triton X-100 soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed by western blot. To this purpose, the samples were heated to 95 °C for four minutes with SDS-Blue loading buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, #7722) and DTT (Cell Signaling Technology, #1425S), and analyzed by 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Mini-PROTEAN TGX pre-cast gels; Bio-Rad, #4561096). Western blots were probed sequentially with rabbit anti-GFP primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, #2956) and HRP-linked anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:2000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, #7074), then with rat anti-myosin primary antibodies (1:10,000 dilution, Babraham Institute Enterprise) and HRP-linked anti-rat secondary antibodies (1:5000 dilution for the insoluble fraction and 1:2000 dilution for the soluble fraction; Cell Signaling Technology #7077) in 5% skim milk powder in TBST (tris-buffered saline with Tween 20). The anti-GFP antibody was used to measure the levels of GFP-tagged huntingtin-polyQ, and the anti-myosin antibody was used as a loading control. The image analysis of western blots was done with the ImageJ software. The full scans of western blots are provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted as previously described48,76,107. Total RNA was isolated from Drosophila thoraces (primarily composed of skeletal muscle) and heads (enriched for brains and retinas) dissected from typically ~30 male flies per replicate using TRIzol (ThermoFisher #15596026). cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad #1708840). qRT-PCR was carried out with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad #170-8885) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR system. Expression levels were normalized to tubulin84B levels, and relative quantification was performed using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method. The following oligonucleotides were used:

Amyrel: 5’-CTCACAACTCCCGTCCCTTC-3’ and 5’-CCTCGGAGAATCGGAACTCG-3’

Prosb5: 5’-GGAGGAAGAGCAAAAAGGGCT-3’ and 5’-TTAAGGTTGTGCAGGGGGTTC-3’

Ter94/VCP: 5’-CCCAACCGACTGATTGTGGA-3’ and 5’-TCATGCGGATCTTCTCGTCG-3’

Tropomyosin 1 (Tm1): 5’-AAGTCGCGGATAACTCCGAA-3’ and 5’-GTCCTTGTCGACTTTCATCGC-3’

ND-75: 5’-GGTCTGTCAAAGCAAAATCCGA-3’ and 5’-TGGCCATCTGATGTGTGGG-3’

Tubulin84B: 5’-GCTGTTCCACCCCGAGCAGCTGATC-3’ and 5’-GGCGAACTCCAGCTTGGACTTCTTGC-3’

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was prepared from Drosophila thoraces (degutted) and heads, and RNA sequencing was done as previously described48,76,107,108. Three biological replicates per group were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Reads were aligned to the Drosophila melanogaster reference genome (BDGP5) using the STAR aligner (v2.5.3a)109. Gene-level counts were obtained using HTSeq (v0.6.1p1)110 and the BDGP5 GTF release 75. Normalization factors were calculated using the TMM method111. Differential expression analysis was performed with precision weights estimated via the voom function112 in the limma package in R v3.2.3113. The RNA-seq data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are accessible with the identifier GSE299453. Correlation values were calculated in Excel. GO term analysis was done with DAVID114, and the information on protease clans was retrieved from the MEROPS database72,73.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data of gene expression changes induced in the muscle and CNS by the muscle-specific perturbation of multiprotein complexes is reported in Supplementary Dataset 1 and was deposited to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and is accessible with the identifier GSE299453. The RNAi screen for stress-induced proteases is provided in Supplementary Dataset 2. The homology of stress-induced proteases is reported in Supplementary Dataset 3. Additional source data are provided in Supplementary Dataset 4.

References

Marsh, J. A. & Teichmann, S. A. Structure, dynamics, assembly, and evolution of protein complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84, 551–575 (2015).

Pereira-Leal, J. B., Levy, E. D. & Teichmann, S. A. The origins and evolution of functional modules: lessons from protein complexes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361, 507–517 (2006).

Perica, T. et al. The emergence of protein complexes: quaternary structure, dynamics and allostery. Colworth Medal Lecture. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 475–491 (2012).

Whitty, A. Cooperativity and biological complexity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 435–439 (2008).

Ahnert, S. E., Marsh, J. A., Hernandez, H., Robinson, C. V. & Teichmann, S. A. Principles of assembly reveal a periodic table of protein complexes. Science 350, aaa2245. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2245 (2015).

Levy, E. D. & Teichmann, S. Structural, evolutionary, and assembly principles of protein oligomerization. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 117, 25–51 (2013).

Natan, E. et al. Cotranslational protein assembly imposes evolutionary constraints on homomeric proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 279–288 (2018).

Wells, J. N., Bergendahl, L. T. & Marsh, J. A. Co-translational assembly of protein complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 1221–1226 (2015).

Ghezzi, D. & Zeviani, M. Human diseases associated with defects in assembly of OXPHOS complexes. Essays Biochem. 62, 271–286 (2018).

Lazarou, M., Thorburn, D. R., Ryan, M. T. & McKenzie, M. Assembly of mitochondrial complex I and defects in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 78–88 (2009).

Balch, W. E., Morimoto, R. I., Dillin, A. & Kelly, J. W. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319, 916–919 (2008).

Douglas, P. M. & Dillin, A. Protein homeostasis and aging in neurodegeneration. J. Cell Biol. 190, 719–729 (2010).

Klaips, C. L., Jayaraj, G. G. & Hartl, F. U. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 217, 51–63 (2018).

Labbadia, J. & Morimoto, R. I. The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem 84, 435–464 (2015).

Quiros, P. M., Mottis, A. & Auwerx, J. Mitonuclear communication in homeostasis and stress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 213–226 (2016).

Kourtis, N. & Tavernarakis, N. Cellular stress response pathways and ageing: intricate molecular relationships. EMBO J. 30, 2520–2531 (2011).

Hirst, J. Mitochondrial complex I. Annu. Rev. Biochem 82, 551–575 (2013).

Copeland, J. M. et al. Extension of Drosophila life span by RNAi of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Curr. Biol. 19, 1591–1598 (2009).

Owusu-Ansah, E., Song, W. & Perrimon, N. Muscle mitohormesis promotes longevity via systemic repression of insulin signaling. Cell 155, 699–712 (2013).

Jovaisaite, V., Mouchiroud, L. & Auwerx, J. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response, a conserved stress response pathway with implications in health and disease. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 137–143 (2014).

Munch, C. The different axes of the mammalian mitochondrial unfolded protein response. BMC Biol. 16, 81 (2018).

Shpilka, T. & Haynes, C. M. The mitochondrial UPR: mechanisms, physiological functions and implications in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 109–120 (2018).

Veatch, J. R., McMurray, M. A., Nelson, Z. W. & Gottschling, D. E. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to nuclear genome instability via an iron-sulfur cluster defect. Cell 137, 1247–1258 (2009).

Pakos-Zebrucka, K. et al. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 17, 1374–1395 (2016).

Settembre, C. et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 31, 1095–1108 (2012).

Hunt, L. C. et al. An adaptive stress response that confers cellular resilience to decreased ubiquitination. Nat. Commun. 14, 7348 (2023).

Rai, M. et al. Proteasome stress in skeletal muscle mounts a long-range protective response that delays retinal and brain aging. Cell Metab. 33, 1137–1154.e1139 (2021).

Rai, M., Hunt, L. C. & Demontis, F. Stress responses induced by perturbation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Trends Biochem. Sci. 50, 175–178 (2025).

Hanna, J., Meides, A., Zhang, D. P. & Finley, D. A ubiquitin stress response induces altered proteasome composition. Cell 129, 747–759 (2007).

Park, S., Kim, W., Tian, G., Gygi, S. P. & Finley, D. Structural defects in the regulatory particle-core particle interface of the proteasome induce a novel proteasome stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36652–36666 (2011).

Steffen, K. K. et al. Yeast life span extension by depletion of 60s ribosomal subunits is mediated by Gcn4. Cell 133, 292–302 (2008).

Kim, J. et al. Peroxisomal import stress activates integrated stress response and inhibits ribosome biogenesis. PNAS Nexus 3, 429 https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae429 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. ATR mediates a checkpoint at the nuclear envelope in response to mechanical stress. Cell 158, 633–646 (2014).

Malhas, A., Saunders, N. J. & Vaux, D. J. The nuclear envelope can control gene expression and cell cycle progression via miRNA regulation. Cell cycle 9, 531–539 (2010).

Thibault, G. et al. The membrane stress response buffers lethal effects of lipid disequilibrium by reprogramming the protein homeostasis network. Mol. cell 48, 16–27 (2012).

Boulon, S., Westman, B. J., Hutten, S., Boisvert, F. M. & Lamond, A. I. The nucleolus under stress. Mol. Cell 40, 216–227 (2010).

James, A., Wang, Y., Raje, H., Rosby, R. & DiMario, P. Nucleolar stress with and without p53. Nucleus 5, 402–426 (2014).

Reiling, J. H. et al. A CREB3-ARF4 signalling pathway mediates the response to Golgi stress and susceptibility to pathogens. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1473–1485 (2013).

Dillin, A., Gottschling, D. E. & Nystrom, T. The good and the bad of being connected: the integrons of aging. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 26, 107–112 (2014).

Taylor, R. C., Berendzen, K. M. & Dillin, A. Systemic stress signalling: understanding the cell non-autonomous control of proteostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 211–217 (2014).

Wang, L., Karpac, J. & Jasper, H. Promoting longevity by maintaining metabolic and proliferative homeostasis. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 109–118 (2014).

Galluzzi, L., Yamazaki, T. & Kroemer, G. Linking cellular stress responses to systemic homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 731–745 (2018).

Calculli, G. et al. Systemic regulation of mitochondria by germline proteostasis prevents protein aggregation in the soma of C. elegans. Sci. Adv. 7, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg3012 (2021).

Demontis, F., Patel, V. K., Swindell, W. R. & Perrimon, N. Intertissue control of the nucleolus via a myokine-dependent longevity pathway. Cell Rep. 7, 1481–1494 (2014).

Demontis, F. & Perrimon, N. FOXO/4E-BP signaling in Drosophila muscles regulates organism-wide proteostasis during aging. Cell 143, 813–825 (2010).

Gutierrez-Monreal, M. A. et al. Targeted Bmal1 restoration in muscle prolongs lifespan with systemic health effects in aging model. JCI Insight 9, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.174007 (2024).

Katewa, S. D. et al. Intramyocellular fatty-acid metabolism plays a critical role in mediating responses to dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 16, 97–103 (2012).

Robles-Murguia, M. et al. Muscle-derived Dpp regulates feeding initiation via endocrine modulation of brain dopamine biosynthesis. Genes Dev. 34, 37–52 (2020).

Rai, M. & Demontis, F. Systemic nutrient and stress signaling via myokines and myometabolites. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 85–107 (2016).

Rai, M. & Demontis, F. Muscle-to-brain signaling via myokines and myometabolites. Brain Plast. 8, 43–63 (2022).

Pedersen, B. K. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 383–392 (2019).

Pedersen, B. K., Akerstrom, T. C., Nielsen, A. R. & Fischer, C. P. Role of myokines in exercise and metabolism. J. Appl Physiol. 103, 1093–1098 (2007).

Demontis, F., Piccirillo, R., Goldberg, A. L. & Perrimon, N. The influence of skeletal muscle on systemic aging and lifespan. Aging Cell 12, 943–949 (2013).

King, J. S., Veltman, D. M. & Insall, R. H. The induction of autophagy by mechanical stress. Autophagy 7, 1490–1499 (2011).

Akimoto, T. et al. Skeletal muscle adaptation in response to mechanical stress in p130cas-/- mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 304, C541–C547 (2013).

Morton, J. P., Kayani, A. C., McArdle, A. & Drust, B. The exercise-induced stress response of skeletal muscle, with specific emphasis on humans. Sports Med. 39, 643–662 (2009).

Kayani, A. C., Morton, J. P. & McArdle, A. The exercise-induced stress response in skeletal muscle: failure during aging. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 33, 1033–1041 (2008).

Cordeiro, A. V. et al. High-intensity exercise training induces mitonuclear imbalance and activates the mitochondrial unfolded protein response in the skeletal muscle of aged mice. Geroscience 43, 1513–1518 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. The unfolded protein response mediates adaptation to exercise in skeletal muscle through a PGC-1alpha/ATF6alpha complex. Cell Metab. 13, 160–169 (2011).

Hart, C. R. et al. Attenuated activation of the unfolded protein response following exercise in skeletal muscle of older adults. Aging 11, 7587–7604 (2019).

Hentila, J. et al. Autophagy is induced by resistance exercise in young men, but unfolded protein response is induced regardless of age. Acta Physiol. 224, e13069, https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13069 (2018).

Ogborn, D. I., McKay, B. R., Crane, J. D., Parise, G. & Tarnopolsky, M. A. The unfolded protein response is triggered following a single, unaccustomed resistance-exercise bout. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 307, R664–R669 (2014).

van Oosten-Hawle, P., Porter, R. S. & Morimoto, R. I. Regulation of organismal proteostasis by transcellular chaperone signaling. Cell 153, 1366–1378 (2013).

Collins, G. A. & Goldberg, A. L. The logic of the 26S proteasome. Cell 169, 792–806 (2017).

Schmidt, M. & Finley, D. Regulation of proteasome activity in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 13–25 (2014).

Wojcik, C. & DeMartino, G. N. Analysis of Drosophila 26 S proteasome using RNA interference. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6188–6197 (2002).

Piccirillo, R. & Goldberg, A. L. The p97/VCP ATPase is critical in muscle atrophy and the accelerated degradation of muscle proteins. EMBO J. 31, 3334–3350 (2012).

van den Boom, J. & Meyer, H. VCP/p97-mediated unfolding as a principle in protein homeostasis and signaling. Mol. Cell 69, 182–194 (2018).

Meyer, H. & Weihl, C. C. The VCP/p97 system at a glance: connecting cellular function to disease pathogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 127, 3877–3883 (2014).

Rassier, D. E. Sarcomere mechanics in striated muscles: from molecules to sarcomeres to cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 313, C134–C145 (2017).

Schuster, C. M., Davis, G. W., Fetter, R. D. & Goodman, C. S. Genetic dissection of structural and functional components of synaptic plasticity. II. Fasciclin II controls presynaptic structural plasticity. Neuron 17, 655–667 (1996).

Rawlings, N. D., Barrett, A. J. & Finn, R. Twenty years of the MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D343–D350 (2016).

Rawlings, N. D. et al. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D624–D632 (2018).

Gottesman, S., Wickner, S. & Maurizi, M. R. Protein quality control: triage by chaperones and proteases. Genes Dev. 11, 815–823 (1997).

Rai, M., Curley, M., Coleman, Z. & Demontis, F. Contribution of proteases to the hallmarks of aging and to age-related neurodegeneration. Aging Cell, e13603 https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13603 (2022).

Jiao, J. et al. Modulation of protease expression by the transcription factor Ptx1/PITX regulates protein quality control during aging. Cell Rep. 42, 111970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111970 (2023).

Geier, E. et al. A giant protease with potential to substitute for some functions of the proteasome. Science 283, 978–981 (1999).

Glas, R., Bogyo, M., McMaster, J. S., Gaczynska, M. & Ploegh, H. L. A proteolytic system that compensates for loss of proteasome function. Nature 392, 618–622 (1998).

Lipinszki, Z. et al. A novel interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome system and serine proteases during Drosophila development. Biochem. J. 454, 571–583 (2013).

Wang, E. W. et al. Integration of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway with a cytosolic oligopeptidase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 9990–9995 (2000).

Karsten, S. L. et al. A genomic screen for modifiers of tauopathy identifies puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase as an inhibitor of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Neuron 51, 549–560 (2006).

Bhutani, N., Venkatraman, P. & Goldberg, A. L. Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase is the major peptidase responsible for digesting polyglutamine sequences released by proteasomes during protein degradation. EMBO J. 26, 1385–1396 (2007).

Menzies, F. M. et al. Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase protects against aggregation-prone proteins via autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet 19, 4573–4586 (2010).

Basurto-Islas, G., Grundke-Iqbal, I., Tung, Y. C., Liu, F. & Iqbal, K. Activation of asparaginyl endopeptidase leads to Tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17495–17507 (2013).

Miller, J. P. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases are modifiers of huntingtin proteolysis and toxicity in Huntington’s disease. Neuron 67, 199–212 (2010).

Sevalle, J. et al. Aminopeptidase A contributes to the N-terminal truncation of amyloid beta-peptide. J. Neurochem. 109, 248–256 (2009).

Zhang, Z. et al. Cleavage of tau by asparagine endopeptidase mediates the neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 20, 1254–1262 (2014).

Zhang, S., Binari, R., Zhou, R. & Perrimon, N. A genomewide RNA interference screen for modifiers of aggregates formation by mutant Huntingtin in Drosophila. Genetics 184, 1165–1179 (2010).

Kazantsev, A., Preisinger, E., Dranovsky, A., Goldgaber, D. & Housman, D. Insoluble detergent-resistant aggregates form between pathological and nonpathological lengths of polyglutamine in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11404–11409 (1999).

Curley, M. et al. Transgenic sensors reveal compartment-specific effects of aggregation-prone proteins on subcellular proteostasis during aging. Cell Rep. Methods, 100875, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100875 (2024).

Hunt, L. C. et al. The ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2D maintains a youthful proteome and ensures protein quality control during aging by sustaining proteasome activity. PLoS Biol. 23, e3002998 (2025).

Sopko, R. et al. Combining genetic perturbations and proteomics to examine kinase-phosphatase networks in Drosophila embryos. Dev. Cell 31, 114–127 (2014).

Brand, A. H. & Perrimon, N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415 (1993).

Lai, S. L. & Lee, T. Genetic mosaic with dual binary transcriptional systems in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 703–709 (2006).

Lopez-Otin, C. & Bond, J. S. Proteases: multifunctional enzymes in life and disease. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30433–30437 (2008).

Quesada, V., Ordonez, G. R., Sanchez, L. M., Puente, X. S. & Lopez-Otin, C. The Degradome database: mammalian proteases and diseases of proteolysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D239–D243 (2009).

Quiros, P. M., Langer, T. & Lopez-Otin, C. New roles for mitochondrial proteases in health, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 345–359 (2015).

Hargreaves, M. & Spriet, L. L. Skeletal muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Nat. Metab. 2, 817–828 (2020).

Egan, B. & Zierath, J. R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 17, 162–184 (2013).

Okonkwo, O. & van Praag, H. Exercise effects on cognitive function in humans. Brain Plast. 5, 1–2 (2019).

Voss, M. W. et al. Exercise and hippocampal memory systems. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 318–333 (2019).

Moon, H. Y. et al. Running-induced systemic cathepsin B secretion is associated with memory function. Cell Metab. 24, 332–340 (2016).

Carpenter, A. E. et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7, R100 (2006).

Wassenberg, D. R. 2nd, Kronert, W. A., O’Donnell, P. T. & Bernstein, S. I. Analysis of the 5’ end of the Drosophila muscle myosin heavy chain gene. Alternatively spliced transcripts initiate at a single site and intron locations are conserved compared to myosin genes of other organisms. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 10741–10747 (1987).

Osterwalder, T., Yoon, K. S., White, B. H. & Keshishian, H. A conditional tissue-specific transgene expression system using inducible GAL4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12596–12601 (2001).

Rai, M. et al. Analysis of proteostasis during aging with western blot of detergent-soluble and insoluble protein fractions. STAR Protoc. 2, 100628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100628 (2021).

Hunt, L. C. et al. Circadian gene variants and the skeletal muscle circadian clock contribute to the evolutionary divergence in longevity across Drosophila populations. Genome Res. 29, 1262–1276 (2019).

Graca, F. A. et al. Progressive development of melanoma-induced cachexia differentially impacts organ systems in mice. Cell Rep. 42, 111934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111934 (2023).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Law, C. W., Chen, Y., Shi, W. & Smyth, G. K. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 15, R29. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29 (2014).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Huang, D. W. et al. The DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol. 8, R183. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Light Microscopy facility and the Hartwell Center for Bioinformatics and Biotechnology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. We further thank Dr. Tzumin Lee for LexA-GAD and pLOT plasmids, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Japanese National Institute of Genetics, and the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center for fly stocks. Work in the Demontis lab is supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG075869). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Research at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is supported by the ALSAC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R., H.J.E.B., C.-L.C., and A.P. did the experimental analyses, with help from M.C.; D.F. analyzed RNA-seq data; F.D. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. The following authors contributed equally to this work: M.R., H.J.E.B., C.-L.C., and A.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rai, M., Baddeley, H.J.E., Chuang, CL. et al. Perturbation of multiprotein complexes in skeletal muscle induces protective proteases in the CNS that degrade pathogenic proteins. npj Aging 11, 97 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00288-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00288-z