Abstract

Biological clocks aim to estimate the physiological state of an organism, or of specific organs or systems, from the perspective of aging. The inferred individual age acceleration is presumably linked to increased mortality and morbidity risks. Here, we introduce a cognitive aging clock based on a battery of five tests (sensomotor arithmetic, sensomotor mirror letter, 1-back, campimetry and the Stroop), capturing sensory and verbal perception, working memory, and decision-making in the context of cognitive conflict. The developed LightGBM machine learning model has the cognitive age MAE of 7.6 years. SHAP analysis yields the overall and individualized interpretations of accelerated aging. In particular, we demonstrate the dominant contribution of Stroop and campimetry test variables to cognitive age. The cognitive age is accelerated in the patients with dementia, whereas moderate cognitive impairment also shows the acceleration trend, but lacks statistical significance. MoCA test score is negatively associated with cognitive age deviation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global rise in life expectancy presents the challenge of extending both the duration and quality of an individual’s physical, social, and functional capacities. Given the highly personalized and variable rates of aging, the concept of “biological age” has emerged a measure tied to the functional state of organs and systems, rather than chronological age1. The cognitive state is a key indicator of healthy aging, primarily defined by memory, attention, executive thinking, and motor responses. Cognitive decline is driven by age-related changes in the brain at both cellular and systemic levels2, resulting in a progressive deterioration of mental abilities. This decline varies significantly across individuals and accelerates with advancing age3,4. Accelerated degradation of cognitive abilities can be a marker of the development of degenerative brain diseases5. Consequently, the ability to assess cognitive functions and, in particular, the cognitive age of a person can help identify early signs of neurodegeneration and serve as a fundamental basis for the development of new diagnostic approaches.

There are many approaches to predict brain age. One of the most promising techniques relies on the analysis of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images assisted by machine learning and artificial intelligence tools6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In particular, a simple fully convolutional network (SFCN) architecture was implemented to predict brain age based on 3D brain images with minimal preprocessing6. The mean absolute error (MAE) of the prediction based on data from people aged 44–80 years was just 2.14 years. Other studies obtained competitive values of brain age, the MAE varying in the range of 2.2–4.6 years11,12. Despite the high accuracy in predicting a person’s age based on MRI data, the magnetic resonance imaging method can’t yet be widely used to determine the onset of degenerative diseases. Electroencephalogram signals (EEG) were also used to estimate brain age13,14,15,16. In particular, EEG recordings during sleep were used to develop the brain age model, which revealed a connection between accelerated brain aging and sleep disturbances, cf. insomnia13,14. The brain clocks had MAE of 4.6 and 5.4 years, respectively.

Psychophysiological and cognitive tests offer a low-cost, online-use adapted alternative for assessing human cognitive functions and determining brain age. Numerous studies have proposed various screening tests to explore functional changes in the brain by evaluating memory, temporal and spatial orientation, as well as mathematical ability17,18,19,20,21,22. Although cognitive decline is a typical consequence of aging, the rate and extent of these changes vary considerably between specific functions and individuals. Therefore, developing batteries of cognitive tests, increasing the amount of data derived from participants’ performance, and training artificial neural networks (ANN) and machine learning (ML) models is a promising approach for detecting cognitive impairment at different stages. To date, ML tools have been extensively applied to psychophysiological and cognitive tests for classification, clustering, and regression problems, in particular, to predict cognitive age21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

Recently, we have introduced a cognitive clock model based on the 3 tests: sensorimotor tests (arithmetic, mirror letters) and color campimetry28. The Arithmetic test assesses the speed and accuracy of sensorimotor responses, in particular, the efficiency of manipulating schematic knowledge based on examination of simple arithmetic expressions. The mirror letters test also infers sensorimotor responses, focusing on recognition of the spatial features of objects. The Color Campimetry test estimates the accuracy of color discrimination, the correctness of object shape recognition, and the efficiency of working memory. Instructively, the study revealed associations between the accelerations of cognitive and epigenetic ages28. The MAE of the model was 8.62, comparable with MRI- and EEG-based models (with characteristic MAE = 3–7 years). The major limitation of the model was the limited sample size of 118 participants. A broader spectrum of evaluated cognitive processes remained a challenge.

Here, we develop a cognitive age model based on artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms that integrates and evaluates the perception of sensory and verbal information, as well as its processing by working memory. In addition to the previously used 3 tests, we implement the 1 Back by Color test that determines the efficiency of working memory and errors in color recognition, and the Stroop test that grasps the speed and accuracy of recognizing words denoting color, the speed and accuracy of recognizing the color of objects, and the efficiency of cognitive control in the context of a cognitive conflict between the verbal and sensory image of color. The resulting 5-test model is coined Cognitive-Age-V. To our knowledge, neither 1 Back by Color nor Stroop tests have been employed in cognitive age models before, although their relevance to characterizing brain aging and cognitive impairment is widely accepted31,32,33,34,35,36. Remarkably, we find a strong association of the performance of the Stroop test with chronological age and show that an AI-based cognitive age model can be built on the Stroop test alone (Cognitive-Age-I model, MAE = 8.9 years with bias correction). We rebuilt the cognitive age model based on the 3 original tests28 using the novel dataset of 1814 participants (Cognitive-Age-III model, MAE = 9.1 years with bias correction) and demonstrate the efficiency of Cognitive-Age-V (MAE = 7.6 years with bias correction).

Results

Cognitive-Age-III model

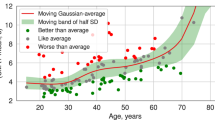

Our previous paper introduced the Cognitive Clock that was developed using a dataset of only 118 subjects aged 19–85 years and achieved the MAE of 8.62 years using the support vector machine (SVM) method28. Another key limitation was a significant systematic error in estimating the cognitive age of younger and older subjects. Here, we expanded the dataset to 1814 subjects aged 20–85 (General group, Section “Methods”) and implemented a special procedure of bias correction (Section “Bias correction”). For comparison, we trained the ML model on subset of features similar to those used in ref. 28 (subset III, cf. Section “Feature subsets”). The best performance was achieved using the LightGBM model, reducing the test set MAE to 7.4 years without bias correction. However, after bias correction, the MAE increased to 9.1 years (Fig. 1a, b, Cognitive-Age-III model). Instructively, the models optimized for different criteria, zero cognitive age bias or a minimal MAE, can differ substantially. The former approach is strongly preferred, as it eliminates spurious age acceleration in both younger and older participants while yielding more interpretable results in disease contexts.

Panel rows corresponds to optimal models for three models: a, b Cognitive-Age-III based on 2 sensomotor tests and campimetry; c, d Cognitive-Age-I based on Stroop test; (e, f): Cognitive-Age-V based on 3 sensomotor, campimetry and Stroop tests. Left column (a, c, e): prediction of chronological age by models for train and test samples; black line corresponds to the diagonal of the first quarter. Right column (b, d, f): distribution of age deviations of best model.

Cognitive-Age-I model

To expand the range of assessed age-related changes in brain function and enhance the Cognitive Age model’s performance, we incorporated the Stroop test (ST) and 1-back test (SM 1back) in the test battery, targeting components of the executive function (EF)37,38,39. EF encompasses cognitive processes involved in the general goal-directed action mechanisms37. EF is divided into separate skills, including inhibition, updating, and shifting, which may operate either collaboratively or independently depending on task demands37. Specifically, the Stroop test measures the inhibition function under conflicting stimuli, whereas the n-back test assesses the updating function supported by working memory. Association of EF with age has been demonstrated in a number of neuropsychological test results38,39 and MRI findings40,41.

Notably, Stroop test indicators demonstrate strong correlations with both age and age-related diseases31,32,33,34,35,36. Previous research has shown that incongruent error rate in the Stroop Task Switching better discriminates between healthy aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) than any other 18 cognitive tasks in the psychometric battery31. To specifically evaluate this test’s predictive power for cognitive age, we developed a model using Stroop test results exclusively.

It is important to note that previous studies primarily focused on the total time to complete trial blocks, while neglecting quantitative measures of error rates and test-specific switching effect31. However, these parameters prove quite powerful, as the test performance reflects both the ability and the speed of the brain to process information. Therefore, we incorporated sensorimotor indicators that characterize the test in dynamics in the feature subsets (I) and (V). Besides, we computed Pearson and Kendall correlation coefficients between the cognitive indices and stimuli numbers to take into account the changes in responses during the test. We similarly analyzed difference series between adjacent stimulus responses. While correlations features were filtered out later during the feature selection process, the statistics of adjacent stimuli responses were included to the final model (Fig. 2), (Supplementary Table S1: Selected features).

The resulting MAE of the best Cognitive-Age-I model trained on (I) turned out to be 7.1 years without bias correction and 8.9 years after correction (Fig. 1c, d, Cognitive-Age-I). Its performance is superior to the Cognitive-Age-III, based on the 3 previously considered tests.

Cognitive-Age-V model

The best performance was achieved by the model built on the feature subset (V) that incorporated the cognitive quantifiers from all 5 tests: 3 sensomotor tests on color and shape memorizing (SM 1-back), arithmetic correctness (SM arithmetic) and mirror letters check (SM letters), together with the Stroop and campimetry tests, cf. Section “Feature subsets”. Detailed description of tests provided in Supplementary Materials, sec. Description of cognitive tests. The interface and sample stimuli of the corresponding tests on the online platform are displayed in Supplementary Figs. S1–S5. To improve the robustness and interpretability of the model we implemented an iterative feature selection procedure (Section “Data preprocessing”) that resulted in the subset of 23 features, employed in the model. Hyperparameter tuning was performed on validation subsets using CV 5-fold independently for each subset of features using Optuna framework42. In result, the LightGBM architecture outperformed the other models in terms of MAE on the test set, and yielded 6.6 years before and 7.6 years after bias correction (Fig. 1e, f, Cognitive-Age-V). The summarizing results for top-3 models are presented in Table 1. Overall, Cognitive-Age-V outperforms both the Cognitive-Age-III and Cognitive-Age-I models, having MAE 7.6, 9.1 and 8.9 after bias correction, respectively. The same is observed for the models before bias correction, cf. Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S6. These results underscore the value of comprehensive cognitive assessment through the 5-test battery.

General properties of the Cognitive-Age-V model

Interpretation of the cognitive age estimation is essential for understanding the relevance of particular tests to determining cognitive status, the contribution of assessed cognitive functions to cognitive age deviations, the general evaluation of age-dependent cognitive decline.

Since the implemented machine learning models are nonlinear, inferring the impact of the selected features (cognitive quantifies) to the output of the model (prediction of cognitive age) is non-trivial. Here we rely on the SHAPley value analysis. More specifically, to extract the general contribution of features to the cognitive age model, we define the group of young subjects (under 30 years), and compare it to the remaining older subjects to calculate SHAP values. We find that all 5 tests contribute to the cognitive age estimation. However, 9 out of 23 features are quantifiers of the Stroop test and 8 out of 23 stand for the campimetry test. Besides, these features are characterized by the higher average SHAP values, that gives evidence of the higher importance of the Stroop and campimetry tests for the cognitive age. The 12 most informative features of the Cognitive-Age-V model as indicated by the SHAP global explainability are shown in Fig. 2.

These features can be scrutinized as activity indicators for the cognitive modules of “fluid intelligence” (biologically determined) and “crystallized abilities” (experience-dependent and associated with learning). Accordingly, the following 7 features quantify “fluid intelligence”:

-

1.

The first quartile of the sensorimotor reaction time in the Stroop test task (true color);

-

2.

The first quartile of the sensorimotor reaction time in the Stroop test task (color);

-

3.

The minimum time to complete the task in the direct task of the campimetry test;

-

4.

The third quartile of the motor reaction time in the 1-back test;

-

5.

The median value of the number of shades in the direct task of the campimetry test;

-

6.

The average value of the number of shades in the inverse task of the campimetry test;

-

7.

First quartile of task execution time in the direct task of the campimetry test.

It is instructive to note that the majority of top-significant features according to the SHAP analysis and related to “fluid intelligence” come from the tests that involve color recognition: the speed of sensorimotor reaction in the Stroop test in contexts with and without cognitive conflict, as well as the threshold value and the time of solving the direct color discrimination task in the campimetry test and the motor reaction time in the 1-back task by color.

"Crystallized abilities” are represented in the list by 5 features only:

-

1.

First quartile of sensorimotor reaction time in the Stroop test task (mono);

-

2.

The average of the sensorimotor reaction time in the Stroop test task (mono);

-

3.

First quartile of motor reaction time in a task with arithmetic expressions;

-

4.

Third quartile of sensorimotor reaction time in the Stroop test task (true text);

-

5.

Minimum motor reaction time in a task with arithmetic expressions;

These findings correspond well to the previously characterized dynamics of age-dependent changes in cognitive processes. In particular, the two trends were identified in the meta-analysis of longitudinal, cross-sectional and pseudo-longitudinal studies of cognitive functions: a linear decrease in the basic indicators from 20 to 80 years and a gradual increase with the saturation around 60 years and a subsequent decrease by 80 years43. The first trend is associated with fluid cognitive functions, that are dominated by biological factors. The second trend is characteristic of crystallized abilities, including aggregated skills and memories that are based on the accumulated general knowledge, such as derived from reading comprehension, math, science, historical information, and vocabulary.

The analysis of SHAP values also highlights sex-specific differences (Fig. 3). In particular, the time of motor reactions in all sensorimotor tests contribute to the cognitive aging of women stronger than for men. Incidentally, some studies indeed report more pronounced age-related changes in human motor cortical stimulus-response characteristics for women44,45. At the same time, the timing of the direct task in the campimetry test makes a higher contribution to the men’s cognitive age.

The SHAP plot illustrating the global sex-specific contribution of the cognitive quantifiers to cognitive age deviations according to the Cognitive-Age-V model. Red bars represent female subjects, blue bars represent male subjects. The star symbol (⋆) indicated statistical difference between males and females according to the Mann–Whitney test adjusted by Benjamini–Yekutieli p-value <0.05.

Personalized interpretation of cognitive age deviation

The overall spread of differences between age and cognitive age is due to the heterogeneity of population and individual aging trajectories. Technically, the deviation of the estimated cognitive age from the chronological age occurs because cognitive abilities are mismatched with results expected by the model for the particular age. Indeed, personalized interpretation of cognitive test results, and, most importantly, cognitive age deviation is vital to identify and further address individual deficiencies. As a rule of thumb, detecting the alarming cases of cognitive accelerations or decelerations relies on MAE as the threshold of significance46. Deeper insights can be obtained by applying local explainability of the model in terms of SHAP values, as we exemplify, characterizing the contribution of particular cognitive quantifiers to the cognitive age deviation.

Examples of local explanations for individual cognitive age deviation using SHAP on the test datasets are presented on the Fig. 4 for positive, negative acceleration, and normal aging. Individual SHAP plots present the top 9 features produced by LightGBM in descending order according to the SHAP values of all predictions. These plots show the positive or negative association of each feature with the predicted outcome, with the absolute SHAP value for each feature displayed on the left.

Figure 4a elucidates the acceleration of the cognitive aging of a 47-year old female. This SHAP profile of cognitive functions illustrates an acceleration of cognitive age by +18 years. SHAP plot indicates that color discrimination in campimetry test and sensorimotor reaction times of the Stroop tests have proved to be the main determinants of the result. Such changes can be interpreted as manifestations of a deficit in the engram comparison function on the working memory platform in closed neural circuits, including areas of the basal ganglia, neocortex, thalamus, hippocampus, and dopaminergic structures47.

SHAP waterfall plot illustrating the contribution of the cognitive quantifiers to cognitive age deviation individually per subject. The panels corresponds to the 3 representative subjects: a female, chronological age 47 years, cognitive age 65 years, cognitive age deviation +18.19 years; b female, chronological age 47 years, cognitive age 37 years, cognitive age deviation −10.48 years; c male, chronological age 48 years, cognitive age 49 years, cognitive age deviation +0.2 years.

Figure 4b reveals factors that contribute to the deceleration of cognitive aging of a 47-year old female with a cognitive age of 37 years. This SHAP profile of cognitive functions illustrates a specific heterochrony of age-related changes, resulting in the negative cognitive age deviation of −10 years. Here, the lead contributor is the superior performance during the Stroop test that, in particular, could be due to the stable efficiency of color vision and decision-making mechanisms. Mild age-related deficits are manifested only in color discrimination (campimetry tests), which may indicate the influence of the limbic system on color discrimination functions during the tests.

The third example Fig. 4c corresponds to the case, when the Cognitive-Age-V of the participant coincides with its chronological age, in other words, the test battery performance matches an age norm. Decomposition of the results in the SHAP plot provides an insight in maintaining the balance. Here a slight positive contribution to accelerated aging is made by the time of passing the campimetry and Stroop tests, whereas the qualitative characteristics of these tests, as well as the motor reaction in the arithmetic test, on the contrary, show a slight negative cognitive age deviation.

Both the global and local explanations of cognitive age and cognitive age deviation (e.g. Figs. 2 and 4) indicate the prevailing importance of the Stroop test indexes (more specifically, sensorimotor reaction time in tasks true color and color) to the prediction of the model.

Age-related dynamics of feature contributions

Finally, the longitudinal changes in absolute and relative contributions of features to the cognitive age were assessed across ages from 30 to 80 compared to the young group (under 30 years) Supplementary Figs. S7–S10. Two main patterns of age related dynamics was uncovered. For some features, the SHAP values increase monotonously with age and their relative importance remains almost constant. However, some features demonstrate a strongly non-linear age dependence. For example, the number of shade sharpening steps in the campimetry task keeps an almost constant relative contribution until about 50 years. Then up to 80 years it starts gradually increasing from ≈ 2% to ≈ 6%. Decision taking time quantifiers in the Stroop test for both matched and conflicting color and text increase their influence on model results over time from roughly 15% to 20% (cf. Supplementary Fig. S9.). Negative correlations are also found, e.g. the motor reaction in 1-back test shows decline with age in its contribution to the cognitive age from ≈12% to ≈4%. The findings indicate the different age-related dynamics of changes in the characteristics of color discrimination, motor reactions and decision-making time.

The color discrimination function depends on both the number and functionality of the retinal photoreceptors. Although the sensitive period of development of the visual sensory system occurs after birth, since the visual analyzer does not receive stimulation, unlike other sensory systems, the maturation processes of the rod-cone apparatus of the retina are determined to a greater extent by the genetic program than by environmental factors48. The maturation processes of the retina in humans end around 2 years of age and it remains in a relatively stable state until age 50, then the age-related changes begin both in the optical system of the eye and in the properties of the neural network of the visual system (62). Below 50 years, the color discrimination function remains an individual and fairly stable characteristic, and after 50 it begins to make a greater contribution to age-related characteristics, since its decline with age is part of general age-related changes and increasingly correlates with age. In addition, the possibilities of compensation by training the color discrimination function are limited.

Age-related changes in motor reactions in the 1-back color test have the opposite dynamics by contribution cognitive age. For motor reactions it depends on the maturation and age-related changes in the central zones of movement control (premotor zones of the frontal cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brain stem and spinal cord), the state of peripheral nerve fibers49 as well as the musculoskeletal system that performs movement50. At a younger age, when the anatomical, physiological and biochemical state of the executive apparatus of movement (muscles, ligaments, joints and bones) is at the peak of its development, a higher speed of motor responses is largely an age characteristic. With age, the speed of motor reactions is increasingly influenced by both environmental factors (nutrition, environmental and geographical factors, etc.) and the possibility of compensating motor function as a result of training and maintaining an active lifestyle. Thus, with age, the speed of the motor response becomes an individual characteristic and makes an increasingly smaller contribution to determining age-related changes.

Decision-making time in the contexts of the Stroop test, where the goal is to respond to the perceptual image of color for both matched and conflicting color-text conditions, increases its influence on model outcomes over time from ~15% to 20%. This phenomenon can be attributed to the two key factors. First, age-related changes in color vision, as described earlier, play a significant role. Second, the Stroop test engages a multi-component neural system that involves: attention control - focusing and distributing attention51; working and long-term memory - their interaction and functions in the context of semantic and perceptual image processing52; semantic and perceptual processing and their integration53,54. The performance of this multi-component system in tasks requiring the processing of color-related information is strongly influenced by age-related changes, both in younger individuals and more prominently in older populations. These age-related effects become increasingly pronounced over time, underscoring the critical role of aging.

Neurodegeneration and cognitive age deviation

Further, we investigated the influence of non-supervised conditions and the presence of neurodegenerative diseases on the performance on the Cognitive-Age-V model. In addition to the General group used for model development, we recruited the four groups of participants aged 60–85 years, coined Control, Healthy, MCI, and Dementia, who passed the tests under the supervision of an assistant, who ensured that all basic recommendations for the test setup are met Section “Study design”. Participants in both the Control and Healthy groups were apparently healthy and those in the latter also passed the MoCA test with a score greater than 25. MCI and Dementia group participants had respective diagnoses Section “Study design”. Besides, the age-matched group “General Old” was selected from the test subgroup of the General group.

The mean cognitive age deviations in the General Old, Control, Healthy, MCI and Dementia groups were −2.55, −0.25, −0.76, 7.57 and 15.43 years, respectively. The one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in cognitive age deviations between the groups, F(4, 134) ≈ 5.59, p ≈ 0.00034 (Methods section, Section “Statistical analysis”). Post hoc comparisons using Tukey’s HSD showed a statistically significant pairwise difference between the Dementia and General Old groups (p ≈ 0.0005), Dementia and Control groups (p ≈ 0.0041), Dementia and Healthy groups (p ≈ 0.0095), see Fig. 5. In contrast, similar pairwise tests did not reveal significant differences for the MCI group (p ≈ 0.31), despite its higher mean cognitive age deviations (7.57). No significant pairwise differences were found between the General, Control and Healthy groups (p > 0.7).

a Cognitive age deviations across 5 groups (age 60–85): General Old – test set of participants from web site; Control – controlled group of subjects who completed the test on site under same conditions; Healthy – subjects with no diagnosed neurodegenerative diseases; MCI – subjects diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment; Dementia – subjects diagnosed with dementia. One-way ANOVA test was applied with post-hoc Tukey HSD test: (**) p < 0.01, (***) p < 0.001. b Dependence plot between general scores of the MoCA test and corresponding cognitive age deviations obtained using Cognitive-Age-V model. Blue line corresponds to the linear regression.

Additionally, we examined the relationship between cognitive age deviation and MoCA test scores in the Healthy, MCI, and Dementia groups. The predictive linear regression model for MoCA scores based on age delta was statistically significant, F(1, 26) ≈ 11.79, p ≈ 0.002. The linear regression coefficient was −0.21 (SE ≈ 0.061), with t(26) ≈ −3.43, p ≈ 0.002, ρ ≈ −0.56, R2 ≈ 0.31.

Discussion

We developed a novel cognitive age model, coined Cognitive-Age-V, which integrates results of 5 test batteries. For the first time, this includes both the 1-Back by Color and Stroop tests, gold standard measures for assessing cognitive control and working memory. The Cognitive-Age-V battery requires ~20 min to complete, needs only a standard desktop computer with mouse, and achieves a mean absolute error (MAE) of 7.6 years in predicting chronological age on the test dataset. The implemented test batteries employ specific rules for target stimulus selection, engaging six cognitive functions at varying complexity levels: visual processing, selective attention, sensorimotor coordination, verbal instruction comprehension, decision-making, and action execution. Notably, color recognition plays a central role in the Color Campimetry, 1-Back by Color, and Stroop tests. Working memory efficiency is primarily assessed in the 1-Back by Color and Color Campimetry tests, while explicit memory proves critical for generating correct responses in both the Mirror Letters and Stroop tests. Remarkably, we find that the patients with dementia manifest a statistically significant positive cognitive age deviation of 15.43 years (p ≈ 0.0033). Moreover, the preliminary results obtained for MCI patients are promising for the future studies based on larger cohorts. MoCA test score is negatively correlated with the cognitive age deviation.

The perceptual and cognitive functions addressed in this study are particularly susceptible to age-related decline and deterioration associated with age-related diseases. Human color recognition ability, supported by color vision function, exhibits significant age-dependent variations. Existing studies report age-related changes in both the eye’s optical system and the sensory networks responsible for converting optical signals into color perception55,56. This general deterioration in color discrimination primarily stems from reductions in foveal cone density57. Across all age groups, individuals demonstrate greater difficulty discriminating between blue and green hues compared to distinguishing red from yellow. This challenge becomes progressively more pronounced with advancing age. During the aging process, the ocular lens selectively absorbs increased amounts of short-wavelength light (~410 nm) due to progressive accumulation of yellow chromophores. This reduction in blue light transmission represents an early manifestation of cataract formation and induces a functional “blue blindness.” This phenomenon is empirically observable in the shifting color palettes of aging artists, who tend to use progressively more blue pigments in their later works58. The use of warm, high-contrast colors (such as yellow, orange, and red) in home environments can enhance object visibility and facilitate daily activities for older adults. Many seniors report improved nighttime visibility when using red lighting in dark areas (e.g., hallways or bathrooms) compared to conventional night lights59.

The cognitive control and working memory functions, typically evaluated through Stroop and 1-back tests, respectively, exhibit marked age-related decline. This contrasts sharply with schematic knowledge manipulation processes, which remain relatively preserved in advanced age4,60,61. Cognitive control governs goal-directed behavior regulation. Substantial evidence links this function to frontal lobe activity, particularly in the prefrontal cortex. Notably, cognitive control impairments closely resemble the clinical manifestations of “frontal syndrome” (or “dysexecutive syndrome”), which is characterized by disruptions in voluntary behavior control. The cognitive control functions represent relatively recent phylogenetic and ontogenetic developments that mediate top-down, rule-based behavioral regulation. Differential psychology studies demonstrate that cognitive control measures strongly correlate with fluid intelligence metrics, the capacity for solving novel problems that is distinct from crystallized intelligence (i.e., the structured knowledge acquired through formal education)62. From a physiological perspective, age-related cognitive decline in normal aging is typically attributed to progressive neuronal loss and the deterioration of neural connections, following the reverse order of their ontogenetic development. Notably, while fluid cognitive abilities demonstrate measurable decline, crystallized abilities remain preserved, a dissociation that obscures straightforward assessment of aging effects and necessitates specialized cognitive testing63.

The presented Cognitive-Age-V clock not only estimates the cognitive age deviation but implements Explainable AI methods that enable the decomposition of age calculation results into individual test-specific contributions. Such targeted interpretation of the accelerated decrease in cognitive functions relative to normal age-related changes opens the perspective of conducting early and quantitative detection of changes associated with diseases that cause morphological changes and dysfunctional disorders, such as Alzheimer and Parkinson’s diseases, diabetes melitus, hypertension, obesity, hypoxic brain injury, obstructive sleep apnea, clinical depression, bipolar disorder, alcoholism, and head trauma64,65.

Limitations of the study include the possible influence of momentary well-being, accumulated fatigue, lack of sleep, and other casual factors that did not reflect their long-term cognitive status, but could have influenced the performance of participants during the test. The other confounding factors are the difference in the perception of the task instructions between the participants and the potential previous experience with some of the tests from the battery, hence, pre-training effects. Variations in the level of light and color characteristics of computer displays might have introduced disturbances as well. Other limitations include the potential influence of participants’ sex, education level, demography, and computer literacy, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Although the train set could include patients with diseases/disorders, the results for patients diagnosed with dementia and MCI show a positive cognitive age deviation, i.e. this limitation did not significantly affect the outcome. The limited size of the healthy, dementia and MCI diagnosed groups that were assessed in the supervised conditions could affect generalizability of the results and need to be enlarged in future studies.

In summary, the presented results establish the AI-based cognitive biological clock that can effectively and rapidly estimate the cognitive age of an individual, interpret the age deviation from the chronological age in terms of particular cognitive quantifiers, demonstrate sensitivity to dementia and correlation with MoCA test results. Future research should include comparative studies of Cognitive-Age-V with other cognitive clocks derived from EEG and MRI data6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Additionally, investigating associations between Cognitive-Age-V and various epigenetic clocks could reveal valuable insights, particularly in identifying DNA methylation-based predictors of cognitive age deviation28,66,67. Longitudinal data collection and analysis will be essential for advancing our understanding of personalized cognitive aging trajectories. A critical next step involves evaluating the sensitivity of the Cognitive-Age-V model across the spectrum of disorders associated with cognitive impairment. Given its low cost and ease of administration, this cognitive assessment shows promise as a potential screening tool for early detection of cognitive decline prior to clinical manifestation. Future studies should investigate intra-individual versus inter-individual variability through longitudinal repeated measurements.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local ethical committee of Nizhny Novgorod State University (protocol №3 dated 28 May 2024). Informed consents were obtained from all participants after detailed explanation of the study.

The cognitive age models were built based on the group that included 1814 participants of both sexes, aged 20–85 years (729 males and 1085 females, mean age and SD: 47.23 ± 13.13, cf. Supplementary Fig. S12 for more details) hereinafter referred to as the “General group”, see the pipeline in Fig. 6. These participants were invited to pass the tests on the web platform https://dpm-ageing.unn.ru/en/cognitive-age-calculator-v3/ by broad public advertisement. No specific selection criteria were applied. Before the assessment, the participants gave their informed consent. The test required a desktop computer equipped with a mouse and an Internet connection. To test the presence of the computer mouse, the participant had to scroll the mouse wheel. The display width had to be greater than 1000 device-independent pixels, which was automatically tested.

The scheme includes 11 blocks that briefly describe the steps of the pipeline: Data collection (Section “Study design”), Data preprocessing (Section “Data preprocessing”), Feature subsets (Section “Feature subsets”), Building regression models (Section “Machine-learning models”), Model selection (Section “Model selection and evaluation”), Best feature selection (Section “Feature selection”), Model training (Section “Feature selection”), Bias correction (Section “Bias correction”), Model assessment (Section “Model selection and evaluation”), Global explanation (Section “Model explainability”), Local explanation (Section “Model explainability”).

The participants from the General group were free to choose the time and place to carry out the task, and the surroundings, the presence of an assistant or the physical condition of the participants were not controlled. However, participants received the following recommendations on the desktop screen before starting the test: “Take the test in daylight, make sure that the monitor is not illuminated by external light sources, there is no glare, and all colors are distinguishable. Taking tests requires concentration and normal reaction speed, so make sure you have had enough sleep and that nothing distracts you from taking the test”. At the beginning of each of the 5 tests, written instructions explaining the coming task appeared on the screen. The participants had a single attempt to complete the test without practice trials. The sequence of the tests remained identical for all participants.

The test battery builds on previous work on Cognitive Clock28 which included 2 sensorimotor tests (SM arithmetic, SM letters) and one campimetry test (CM). Sensorimotor tests (SM) measure the sensorimotor response and determine the degree of preservation of brain regions, spatial and selective attention resources, as well as the ability to predict and learn68. Computer color campimetry measures the color difference function and quantifies subjective psychophysiological responses. This technology infers some characteristics of object color and shape perception, as well as estimates on the level of working memory and attention, as well as the emotional stress of the participants28.

Two new tests are introduced: the Stroop test and the sensorimotor test 1-back (SM 1back). The SM 1back sensorimotor test is based on the n-back test and assesses age-related changes in working memory69. The Stroop test mainly characterizes the inhibitory control of the participant70. Existing studies of older adults demonstrate a decrease in the cognitive processes served by frontostriatal systems, including the ability to suppress responses to auditory and visual stimuli71,72,73 and the ability to perform working memory tasks. In particular, it was conjectured that age-related changes in cognition occur primarily in the decline of inhibitory control of attention and behavioral control systems74. Altogether, the battery of tests included 3 sensorimotor tests (SM arithmetic, SM letters, SM 1back), campimetry test (CM), and Stroop test (ST), which allow us to characterize the change in psychophysiological reactions of participants from the perspective of age-related decline.

For an additional external validation, we recruited the following four groups of participants aged 60–85 years that passed the tests under the supervision of an assistant, who ensured that the computer desktop displayed recommendations, described in the above, are fulfilled, and briefly informed the participants on the nature of the tests.

-

Control group: included 45 apparently healthy participants with age 63.81 ± 3.57 years (mean ± SD), without applying an additional assessment.

-

Healthy group: included 15 apparently healthy participants with age 67.83 ± 4.26 years (mean ± SD), who also took the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test75 and obtained a score greater than 25.

-

Moderate cognitive impairment (MCI) group: included 7 participants with age 72.00 ± 8.14 years (mean ± SD) diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment.

-

Dementia group: included 6 participants with age 69.83 ± 5.98 years (mean ± SD) diagnosed with dementia.

MCI and Dementia groups were formed based on the clinical records of the outpatient clinic. In particular, the files contained patient complaints about memory, attention, executive or other cognitive dysfunction, results of the neurological clinical assessment, neuropsychological screening using MoCA, appropriate laboratory tests, and brain neuroimaging (Computer Tomography or MRI). Inclusion criteria were signed voluntary informed consent, objective signs of MCI or mild to moderate dementia. The exclusion criteria were refusal to participate in the study, neuroimaging sign of focal brain injury, severe decompensated somatic pathology, severe aphasia, and severe dementia. Cognitive impairment was assessed as MCI (a minor neurocognitive disorder) or dementia (a major neurocognitive disorder) according to the relevant general criteria76,77,78. The MoCA score of 25 cutoff was used as an additional signature for the MCI and dementia screening.

Furthermore, we formed an age-matched 60–85 years “General Old” group from the test set part (20%) of the General group that was used at the model development step. It included 66 participants with age 66.40 ± 5.03 years (mean ± SD).

Data preprocessing

The raw data are time series of cognitive indices, based on the completion of the test battery. The statistics of cognitive indices manifest broad distributions, often multimodal28. They are transformed into cognitive quantifiers such as the average, minimum, and maximum values, standard deviation, median, first, and third quartiles of the cognitive indices, and the average number of errors.

In addition, we calculate the same descriptive statistics for the time series of differences between the values of a current and preceding responses to a stimulus. Pearson and Kendal correlation values between the value of a cognitive index and the respective stimulus number are computed. These characteristics quantify changes in the participant’s performance during the test, affecting the reaction times and frequency of errors. This in turn provides a way to assess the level of individual adaptation to unfamiliar cognitive tasks and the fatigue effect due to the testing79.

Feature subsets

Statistical descriptors that are further used as features for machine learning models are grouped in 3 subsets, according to the relevance to the Cognitive Age models III, I and V. The first set of features (III) includes 64 cognitive quantifiers derived from SM arithmetic, SM letters, and CM cognitive tests implemented in ref. 28. The second set (I) includes 132 cognitive quantifiers obtained specifically from the Stroop test (ST). The third set (V) includes 303 cognitive quantifiers, obtained from 5 tests (CM, SM arithmetic, SM letters, SM 1back, ST). The full list of cognitive quantifiers and the corresponding indices is presented in Supplementary Table S1 (Cognitive test indices, Cognitive test sets, Cognitive quantifiers).

Machine-learning models

The data were preprocessed by subtracting the mean and normalizing by the standard deviation for each quantifier. We examined the following machine learning models from the scikit-learn package80: Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, Linear regression, k-Nearest Neighbors, the multilayer perceptron (MLP), the gradient boosting models AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting, and the Bayesian regression model BayesianRidge; and the gradient boosting model LightGBM (Light Gradient-Boosting Machine) from the LightGBM package81. Regression models were trained to predict the chronological age of the subject.

Model selection and evaluation

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test subsets as follows: 65% (1179), 15% (273) and 20% (362) of participants, respectively. Model hyperparameter selection was performed using the optuna optimization framework42. The quality of the model was evaluated by the 5-fold cross-validation (CV). Data were divided into five equal parts, taking into account the equal age distribution between groups using the Stratified K-Fold algorithm82. Stratification was performed by grouping participants by age into 6 bins: [20, 30), [30, 40), [40, 50), [50; 60), [60; 70), [70, 85). MAE averaged over CV folds was used as a measure of model quality, following previous studies15,16,17,18,26,27,28. The main advantage of this measure is sharing units with predicted variable (years) and, hence, the simplicity of interpretation.

Feature selection

Dimensionality reduction of the feature space was applied to avoid overfitting during training and to extract the most important features. Consequently, we used F-test, iterative stepwise selection, and Shapley value-based selection83 that allows quantifying the contribution of each feature to the model output. The best result was obtained by iterative stepwise selection, keeping 23 features out of 303. The Cognitive-Age-V model was then trained on the selected features listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Selected features). Finally, the selected model with the best hyperparameters is evaluated in the test set.

Bias correction

Age prediction models based on data of different origin (MRI, EEG, ECG - electrocardiography signals) often produce a bias overestimating the predicted age for young people and underestimating the age for older people6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. This happens because the minimum of the loss function in the training step is achieved on a biased curve rather than centered along the bisector. In result, the negative correlation between the age delta (the difference between chronological age and predicted age, also coined cognitive age deviation) and chronological age is frequent in regression models, also independent of the age range of the dataset84. Several approaches for bias correction were implemented6,8,10,85. The procedure usually suffers from data leakage due to using the chronological age of the participants, the variable that is to be estimated by the model itself6,10.

We propose a method that is free from this drawback. The first step is to fit the dependence between the age predicted by the model and the chronological age by means of the linear regression based on the training subset data:

where PAge is the result of the machine learning model, Age is the chronological age, αtrain, βtrain are estimated parameters of the linear regression. Then we apply a linear transform to the predicted age for the i-th subject

so that the slope and intercept of the linear regression to the adjusted data become equal 1 and 0, respectively. The resulting Corrected PAge is referred to hereinafter as cognitive age. The scheme of transformation for particular subject is provided in Supplementary Fig. S11. In particular, we find that αtrain = 0.6044 and βtrain = 18.7. Note, that is always remains possible to compute the originally predicted age based on the corrected value. We stress that the data leakage is avoided since the chronological age from the validation, internal or external test datasets is not used in the correction procedure.

Although bias correction generally increases the model variance, the need for consistent interpretation of the output as biological age justifies this trade-off, as systematic over- or under-estimation could yield misleading results. To further validate the bias removal algorithm, we assessed the average age deviation across different external control groups: General, Control, Healthy, MCI and Dementia (Supplementary Table S4). In the MCI and dementia groups, representing cases of accelerated cognitive aging, the corrected cognitive age deviations are, as expected, positive (7.57 and 15.43), whereas the uncorrected values misleadingly align with the norm (−5.2 and 0.41). Similarly, the corrected values for the Control and Healthy groups show near-zero mean age deviations (−0.25 and −4.09), while the uncorrected deviations were strongly negative (−6.69 and −10.71), which might have falsely suggested exceptional cognitive health. Thus, bias correction yields more physiologically plausible estimates for both healthy and diseased individuals.

Model explainability

We calculate SHAP values (Shapley additive explanations) to identify the contribution of individual features in the final model Cognitive-Age-V with applied bias correction. For that, we select the group of subjects under 30 years from the training set and use it as the background set in the SHAP algorithm for the global explanation of the model. The SHAP values for the subjects in the test set are calculated using the Permutation Explainer83. The feature importance is defined as its average absolute SHAP value based on the test set.

Local explainability (the contribution of a particular feature to the cognitive age estimation for a particular person) was implemented by computing SHAP values of the cognitive age deviation of a person compared to the background subset of 250 subjects with the matched average chronological age. Since chronological age must be used to compute cognitive age deviations for the SHAP procedure, a special masker was applied to exclude its interference with SHAP values by choosing the background group participants with close but not identical age.

This approach allows for a consistent estimate of the contribution of cognitive quantifiers to the accelerated or decelerated aging of cognitive functions of the person.

Statistical analysis

The group comparison was performed using the one-way ANOVA test. Before the analysis, the normality of data was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05) and the homogeneity of the variances using Levene’s test (p > 0.05). Post hoc comparisons were performed with Tukey’s HSD to identify specific group differences. Statistical significance threshold was set to p < 0.05.

The dependence between cognitive age deviation and MoCA was examined by the linear regression analysis. The residual distribution was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05). The regression coefficient, standard errors, t-value, and p-value were used to interpret the strength and significance of the dependence. In addition, the Pearson correlation coefficient ρ and the coefficient of determination R2 were reported.

Statistical analysis was performed using the ‘stats’ module of ‘scipy’ (1.16.0) package.

Data availability

The test dataset and the code with API call for reproducing results of the Cognitive age clock are publicly available on GitHub at https://github.com/mike-live/cognitive-clock-v-paper.

References

Nie, C. et al. Distinct biological ages of organs and systems identified from a multi-omics study. Cell Rep. 38, 110459 (2022).

Blazer II, D. G. Cognitive aging: what we fear and what we know. Perspect. Biol. Med. 60, 569–582 (2017).

Singh-Manoux, A. et al. Obesity phenotypes in midlife and cognition in early old age: the Whitehall II cohort study. Neurology 79, 755–762 (2012).

Salthouse, T. A. When does age-related cognitive decline begin? Neurobiol. aging 30, 507–514 (2009).

Condado, J. G. N. et al. NeuropsychBrainAge: A biomarker for conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 15, e12493 (2023).

Peng, H., Gong, W., Beckmann, C. F., Vedaldi, A. & Smith, S. M. Accurate brain age prediction with lightweight deep neural networks. Med. Image Anal. 68, 101871 (2021).

Ning, K. et al. Improving brain age estimates with deep learning leads to identification of novel genetic factors associated with brain aging. Neurobiol. Aging 105, 199–204 (2021).

Baecker, L. et al. Brain age prediction: a comparison between machine learning models using region-and voxel-based morphometric data. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 2332–2346 (2021).

Gómez-Ramírez, J., Fernández-Blázquez, M. A. & González-Rosa, J. J. Prediction of chronological age in healthy elderly subjects with machine learning from MRI brain segmentation and cortical parcellation. Brain Sci. 12, 579 (2022).

de Lange, A.-M. G. & Cole, J. H. Commentary: Correction procedures in brain-age prediction. NeuroImage 26, 102229 (2020).

Joo, Y. et al. Brain age prediction using combined deep convolutional neural network and multi-layer perceptron algorithms. Sci. Rep. 13, 22388 (2023).

Lombardi, A. et al. Brain age prediction with morphological features using deep neural networks: Results from predictive analytic competition 2019. Front. Psychiatry 11, 619629 (2021).

Yook, S. et al. Predicting brain age based on sleep EEG and DenseNet. In 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 245–248 (IEEE, 2021).

Nygate, Y. et al. 543 EEG-based deep neural network model for brain age prediction and its association with patient health conditions. Sleep 44, A214–A214 (2021).

Engemann, D. A. et al. A reusable benchmark of brain-age prediction from M/EEG resting-state signals. Neuroimage 262, 119521 (2022).

Khayretdinova, M. et al. Predicting age from resting-state scalp EEG signals with deep convolutional neural networks on TD-brain dataset. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1019869 (2022).

Anokhin, A. P. et al. Age-related changes and longitudinal stability of individual differences in ABCD Neurocognition measures. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 54, 101078 (2022).

LaPlume, A. A., Anderson, N. D., McKetton, L., Levine, B. & Troyer, A. K. When I’m 64: age-related variability in over 40,000 online cognitive test takers. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 77, 104–117 (2021).

West, R. & Alain, C. Age-related decline in inhibitory control contributes to the increased Stroop effect observed in older adults. Psychophysiology 37, 179–189 (2000).

Jia, X. et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 21, 1–13 (2021).

Nagumo, R. et al. Automatic detection of cognitive impairments through acoustic analysis of speech. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 17, 60–68 (2020).

Youn, Y. C. et al. Detection of cognitive impairment using a machine-learning algorithm. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 14, 2939–2945 (2018).

De Marco, M., Beltrachini, L., Biancardi, A., Frangi, A. F. & Venneri, A. Machine-learning support to individual diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment using multimodal MRI and cognitive assessments. Alzheimer Dis. Associated Disord. 31, 278–286 (2017).

Kang, M. J. et al. Prediction of cognitive impairment via deep learning trained with multi-center neuropsychological test data. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 1–9 (2019).

Khan, T. & Jacobs, P. G. Prediction of mild cognitive impairment using movement complexity. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 25, 227–236 (2020).

Statsenko, Y. et al. Predicting age from behavioral test performance for screening early onset of cognitive decline. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 661514 (2021).

Anatürk, M. et al. Prediction of brain age and cognitive age: quantifying brain and cognitive maintenance in aging. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 1626–1640 (2021).

Krivonosov, M. et al. A new cognitive clock matching phenotypic and epigenetic ages. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 364 (2022).

Garcia-Gutierrez, F. et al. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia with machine learning-aided neuropsychological assessment using feature engineering and genetic algorithms. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 37, https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5667 (2022).

Revathi, A. et al. Early detection of cognitive decline using machine learning algorithm and cognitive ability test. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 4190023 (2022).

Hutchison, K. A., Balota, D. A. & Ducheck, J. M. The utility of Stroop task switching as a marker for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol. aging 25, 545 (2010).

Cohn, N. B., Dustman, R. E. & Bradford, D. C. Age-related decrements in stroop color test performance. J. Clin. Psychol. 40, 1244–1250 (1984).

Comalli Jr, P. E., Wapner, S. & Werner, H. Interference effects of Stroop color-word test in childhood, adulthood, and aging. J. Genet. Psychol. 100, 47–53 (1962).

Ward, N., Hussey, E., Alzahabi, R., Gaspar, J. G. & Kramer, A. F. Age-related effects on a novel dual-task Stroop paradigm. PloS One 16, e0247923 (2021).

Madden, D. J. & Whiting, W. L. Age-related changes in visual attention. Adv. Cell Aging Gerontol. 15, 41–88 (2003).

Bryan, J. & Luszcz, M. A. Measurement of executive function: considerations for detecting adult age differences. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 22, 40–55 (2000).

Miyake, A. & Friedman, N. P. The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Curr. Directions Psychological Sci. 21, 8–14 (2012).

Belghali, M., Statsenko, Y. & Laver, V. Stroop switching card test: brief screening of executive functions across the lifespan. Aging, Neuropsychol. Cognit. 29, 14–33 (2022).

Idowu, M. I. & Szameitat, A. J. Executive function abilities in cognitively healthy young and older adults-A cross-sectional study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 976915 (2023).

Buckner, R. L. Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron 44, 195–208 (2004).

Lacreuse, A., Raz, N., Schmidtke, D., Hopkins, W. D. & Herndon, J. G. Age-related decline in executive function as a hallmark of cognitive ageing in primates: an overview of cognitive and neurobiological studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190618 (2020).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2623–2631 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2019).

Salthouse, T. A. Selective review of cognitive aging. J. Int. Neuropsychological Soc. 16, 754–760 (2010).

Smith, A. E., Sale, M. V., Higgins, R. D., Wittert, G. A. & Pitcher, J. B. Male human motor cortex stimulus-response characteristics are not altered by aging. J. Appl. Physiol. 110, 206–212 (2011).

Pitcher, J. B., Ogston, K. M. & Miles, T. S. Age and sex differences in human motor cortex input–output characteristics. J. Physiol. 546, 605–613 (2003).

Ladejobi, A. O. et al. The 12-lead electrocardiogram as a biomarker of biological age. Eur. Heart J. Digital Health 2, 379–389 (2021).

Silkis, I. Mechanisms of the Interdependent Influences of the Prefrontal Cortex, Hippocampus, and Amygdala on the Functioning of the Basal Ganglia and the Selection of Behavior. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 45, 729–742 (2015).

O’Brien, K. M. B., Schulte, D. & Hendrickson, A. E. Expression of photoreceptor-associated molecules during human fetal eye development. Mol. Vis. 9, 401–409 (2003).

Clark, B. C. & Taylor, J. L. Age-related changes in motor cortical properties and voluntary activation of skeletal muscle. Curr. Aging Sci. 4, 192–199 (2011).

Roberts, S. et al. Ageing in the musculoskeletal system. Acta Orthop. 87, 15–25 (2016).

Burgoyne, A. P., Tsukahara, J. S., Mashburn, C. A., Pak, R. & Engle, R. W. Nature and measurement of attention control. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2369–2402 (2023).

Entel, O. & Tzelgov, J. When working memory meets control in the stroop effect. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 46, 1387–1406 (2020).

Besner, D. & Young, T. On the relationship between spatial attention and semantics in the context of a stroop paradigm. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 86, 1521–1530 (2024).

Periáñez, J. A., Lubrini, G., García-Gutiérrez, A. & Ríos-Lago, M. Construct validity of the stroop color-word test: Influence of speed of visual search, verbal fluency, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and conflict monitoring. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 36, 99–111 (2021).

Moya, F. J., Brigatti, L. & Caprioli, J. Effect of aging on optic nerve appearance: a longitudinal study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 83, 567–572 (1999).

Forrester, J. Aging and vision. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 81, 809–810 (1997).

Keunen, J., Van Norren, D. & Van Meel, G. Density of foveal cone pigments at older age. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 28, 985–991 (1987).

Duncan, G., Wormstone, I. M. & D Davies, P. The aging human lens: structure, growth, and physiological behaviour. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 81, 818–823 (1997).

Grunwald, J. E., Piltz, J., Patel, N., Bose, S. & Riva, C. E. Effect of aging on retinal macular microcirculation: a blue field simulation study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 34, 3609–3613 (1993).

Craik, F. I. & Bialystok, E. Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 131–138 (2006).

Salthouse, T. A. Mediation of adult age differences in cognition by reductions in working memory and speed of processing. Psychological Sci. 2, 179–183 (1991).

Glisky, E. L. et al. Differences between young and older adults in unity and diversity of executive functions. Aging Neuropsychol. Cognit. 28, 829–854 (2021).

Murman, D. The impact of age on cognition. Semin. Hearing 36, 111–121 (2015).

Harada, C. N., Love, M. C. N. & Triebel, K. L. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 29, 737–752 (2013).

von Schnehen, A. et al. Sensorimotor Impairment in Aging and Neurocognitive Disorders: Beat Synchronization and Adaptation to Tempo Changes. J Alzheimer’s Disease. 100, 945–959 (2024).

Maddock, J. et al. DNA methylation age and physical and cognitive aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 75, 504–511 (2020).

Xu, X. DNA methylation and cognitive aging. Oncotarget 6, 13922–13932 (2015).

Polevaya, S. et al. Event-related telemetry of heart rate for personalized remote monitoring of cognitive functions and stress under conditions of everyday activity. Sovremennye Tehnologii V. Med. 11, 109–114 (2019).

McMillan, K. M., Laird, A. R., Witt, S. T. & Meyerand, M. E. Self-paced working memory: validation of verbal variations of the n-back paradigm. Brain Res. 1139, 133–142 (2007).

Dempster, F. N. The rise and fall of the inhibitory mechanism: Toward a unified theory of cognitive development and aging. Dev. Rev. 12, 45–75 (1992).

Sweeney, J. A., Rosano, C., Berman, R. A. & Luna, B. Inhibitory control of attention declines more than working memory during normal aging. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 39–47 (2001).

Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A. & Sweeney, J. A. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 75, 1357–1372 (2004).

Luna, B., Velanova, K. & Geier, C. F. Development of eye-movement control. Brain Cognit. 68, 293–308 (2008).

Connelly, S. L. & Hasher, L. Aging and the inhibition of spatial location. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 19, 1238 (1993).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Winblad, B. et al. Mild cognitive impairment–beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the international working group on mild cognitive impairment. J. Intern. Med. 256, 240–246 (2004).

Sachdev, P. et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 28, 206–218 (2014).

Jack Jr, C. R. et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 535–562 (2018).

Becker, S. T., Vonthein, R., Volpe, N. J. & Schiefer, U. Factors influencing reaction time during automated kinetic perimetry on the Tubingen computer campimeter. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 2633–2638 (2005).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

James, G. et al. An Introduction to Statistical Learning, vol. 112 (Springer, 2013).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems vol. 30, 4765–4774 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Liang, H., Zhang, F. & Niu, X. Investigating Systematic Bias in Brain Age Estimation with Application to Post-traumatic Stress Disorders. Tech. Rep. (Wiley Online Library, 2019).

Le, T. T. et al. A nonlinear simulation framework supports adjusting for age when analyzing BrainAGE. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 317 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation (grant No 139-15-2025-004 dated 17.04.2025, agreement identifier 000000C313925P3X0002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K., T.K., M.I., T.S., S.P., E.K., V.G. wrote the main manuscript text. M.I., S.P. and C.F. designed the experiment and the research. M.K., T.K. built ML models, prepared figures, made statistical and SHAP analysis, prepared the cognitive age calculator web-platform. T.S., S.P., E.K., V.G. conduct the cognitive test assessment, explained and analyzed the model. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krivonosov, M.I., Khabarova, T.A., Kondakova, E.V. et al. Cognitive aging clock based on Explainable artificial intelligence. npj Aging 11, 105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00289-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00289-y