Abstract

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is one of the most common diseases contributing to declining fertility globally. Autoimmune dysregulation has been implicated in POI, but the role of B cell and its subsets in immune dysregulation in POI remains unclear. In the current study, we investigated whether disturbances in the distribution and functional characteristics of peripheral B cell subsets are associated with POI and its severity. Our results revealed that POI patients exhibited a higher percentage of total CD19+ B cells, but the proportion of memory B cells (MBCs) and plasmablasts was significantly reduced compared to controls. A notable decrease in interleukin-10 (IL-10) production by B cells was observed, primarily due to a reduction in CD19+CD24hiCD27+ and CD19+CD24hiCD38hi regulatory B cells (Bregs). These alterations correlated with elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and decreased anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and antral follicle count (AFC) levels. However, no significant differences were observed in the suppressive capacity of Bregs on interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) or tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) production by autologous CD4+ T cells in POI patients compared with control women. These findings suggest that B-cell dysregulation may contribute to the immune pathogenesis of POI, providing potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is a growing global public health concern, affecting approximately 10-15% of the population. Among the various contributors to female infertility, premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) stands out due to its adverse impact on reproductive capacity. Characterized by cessation of ovarian function, elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol (E2) deficiency before the age of 40, POI is associated with long-term health implications. These encompass heightened risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD), decreased bone mineral density (BMD), substantially reduced fertility, and an overall decrease in life expectancy1,2. The prevalence of POI is estimated to affect 1-5% of women of reproductive age3. However, POI is highly heterogeneous in etiology and the majority remains to be elucidated4.

Autoimmune disturbance has long been considered to explain approximately 5-30% of POI cases5,6,7. Patients with POI had an increased risk for concomitant autoimmune diseases. Notably, a higher frequency of autoantibody positivity, including thyroid-associated thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) and thyroglobulin antibody (TGAb), and antibodies against steroidogenic enzymes (StCA), such as adrenal cortex autoantibody (AAA), has also been reported in patients with POI8,9,10,11. The existence of dysregulated humoral immunity proposed the possibility of aberrant B-cell responses involved in POI. In addition to producing antibodies, B cells can function as antigen-presenting cells to activate autoreactive T cells and secrete proinflammatory cytokines that exacerbate local inflammation12,13,14. Previous cellular immune imbalances, mainly focusing on T cell responses, have identified deficiencies in regulatory T cells (Tregs) and T helper 22 (TH22), and augmented T helper 1 (TH1) response in patients with POI15,16,17,18. Nevertheless, whether B cell and its subpopulations contribute to the immune disturbance in POI remains poorly defined.

In the context of developmental trajectories, peripheral blood circulating B cells can be classified into five phenotypically distinct subtypes: transitional B (TrB) cells, naïve B cells, class-switched memory B cells (MBCs), non-class-switched MBCs, and circulating plasmablasts, which are mainly characterized by their differential expression of surface markers and by playing distinct roles in the adaptive immune response19,20,21. Aberrant B cell subsets have been implicated in diverse autoimmune disorders and solid tumors23,24,25. In particular, diminished memory B cells and expanded naïve B subpopulations are consistently identified in active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients25,26,27.

Similar to Tregs, regulatory B cells (Bregs) constitute a minor subset of B cells and are important for maintenance of immunological homeostasis and self-tolerance. Human Breg cells are primarily enriched in CD19+CD24hiCD38hi and CD19+CD24hiCD27+ subpopulations. Despite this phenotypic heterogeneity, most Breg subsets produce interleukin-10 (IL-10) in response to engagement of CD40, toll-like receptor agonists and the B cell receptor (BCR), and suppress effector T-cell responses, such as production of inflammatory cytokines interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)26,27. Of note, perturbations in the quantity, phenotype, and functionality of Bregs have been linked to autoimmune diseases, transplant rejection, and malignancies27,28,29,30,31. For instance, diminished frequencies of Bregs have been reported in human patients and mice models of multiple autoimmune diseases32, while adoptive transfer of Bregs could alleviate disease severity in mice models34,35,36. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether there is an alteration in either the quantity or the function of Bregs in POI patients.

In the current study, we comprehensively characterized disturbances in B cell subsets in patients with POI and established a correlation between aberrations in B cell subsets and disease severity. Our data could provide new insights into autoimmune pathogenesis and clues for novel therapeutic interventions for patients with POI.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 66 patients with POI and 78 control women with normal ovarian reserve were recruited. The mean age at recruitment of the study cohort was 32 (30, 35) years. No differences in age, BMI, age at menarche, duration of infertility, or thyroid function were found between the two groups (all p > 0.05). As expected, there was a significant increase in the levels of FSH and LH but a decline in E2, AMH, and AFC in patients with POI compared to control women (all p < 0.05). The baseline and reproductive characteristics of all participants are summarized in Table 1.

Alterations of B cell subsets in patients with POI

To investigate the association of B cell disturbance with POI, circulating total B cells and B cell subsets were characterized by flow cytometry on PBMCs (Fig. 1A). Compared to the control women (n = 63), patients with POI (n = 51) exhibited a significantly higher percentage of total CD19+ B cells [4.65 (3.36, 6.37) % vs. 7.94 (5.22, 11.00) %, p < 0.0001]. We then further identified distinct B subsets by assessing the expression of specific cell surface markers, including IgD, CD27, CD38, and CD24. These subsets encompassed CD19+IgD+CD27- naïve B cells, CD19+CD24hiCD38hi TrB cells, CD19+IgD-CD27+ class-switched MBCs, CD19+IgD+CD27+ non-class-switched MBCs, and CD19+CD24-CD38+ plasmablasts19,20,21. We observed notable alterations in the distribution of B subsets within the B cell population between the two groups (35 Controls vs. 23 POI). Specifically, the proportions of class-switched MBCs [24.00 (18.50, 27.70) % vs. 19.00 (13.00, 23.50) %, p = 0.0112], non-class-switched MBCs [11.90 (10.30, 16.30) % vs. 10.10 (7.45, 14.80) %, p = 0.0337] and plasmablasts [1.26 (0.92, 2.02) % vs. 0.93 (0.67, 1.18) %, p = 0.0176] were significantly decreased. No significant differences were detected in the proportions of naïve B cells [58.50 (49.20, 63.70) % vs. 67.70 (59.40, 74.00) %, p = 0.5120] and TrB cells [4.81 (3.70, 6.00) % vs. 4.94 (3.69, 9.56) %, p = 0.3828] between the two groups (Fig. 1B).

A Representative flow cytometry plots depicting total B cells in peripheral blood of POI patients, with corresponding statistical analysis illustrating changes in B cell number and proportion. B Flow cytometry-based analysis showing distribution of B cell subsets in POI patients, with a statistical chart demonstrating relative proportions of these subsets. Total B cells: control (n = 63), POI (n = 51); other subsets: control (n = 35), POI (n = 23). Total B cells, transitional B cells, and plasmablasts were compared by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test; naïve B cells, class-switched and non-class-switched MBCs by Dirichlet regression. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001.

Decreased percentage but not suppressive function of Bregs in patients with POI

We next evaluated whether there was a numerical defect in Bregs in patients with POI (Fig. 2A). We observed a significant decrease in the proportion of IL-10-competent CD19+ B10 cells (CD19+IL-10+) within the peripheral B cell subsets of POI patients [0.43 (0.26, 0.54) % vs. 0.26 (0.18, 0.43) %, p = 0.0234]. Additionally, the percentages of CD19+CD24hiCD27+ Bregs and CD19+CD24hiCD38hi Bregs were significantly lower in POI patients (n = 28) compared to controls (n = 28) [13.65 (9.63, 18.50) % vs. 6.00 (3.35, 8.66) %, p < 0.0001; 3.55 (2.48, 4.55) % vs. 2.24 (1.52, 3.45) %, p = 0.0020] (Fig. 2B).

A Representative flow cytometry plots and statistical analyses showing B10 cell distribution in peripheral blood from POI patients and controls. B Representative flow cytometry plots and statistical analyses showing proportions of CD19+CD24hiCD27+ Bregs and CD19+CD24hiCD38hi Bregs in POI patients and controls. C Schematic of T cell and CD19+CD24hiCD27+ Breg co-culture experiment, with evaluation of Breg immunosuppressive function. B10 cells: control (n = 24), POI (n = 22); Bregs: control (n = 28), POI (n = 28); CD4+ T cells: control (n = 15), POI (n = 15). B10 cells and CD4+ T cells were compared by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test; Bregs were compared by two-tailed Student's t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

To assess whether the functional activity of Bregs might be altered in patients with POI, we isolated CD19+CD24hiCD27+ Bregs from PBMCs derived from individuals with POI (n = 15) and control women (n = 15), and co-cultured with autologous CD4+ T cells to evaluate their impact on T cell inflammatory cytokine production, including IFN-γ and TNF-α. We observed no significant differences in the proportions of CD4+IFN-γ+ [5.45 (1.15, 6.21) % vs. 1.76 (0.95, 4.29) %, p = 0.2017] and CD4+TNF-α+ T cells [32.2 (12, 58) % vs. 30.2 (7.55, 56.7) %, p = 0.4299] between POI patients and controls (Fig. 2C). These findings suggest that Bregs represent intact suppressive capacity on T cell inflammatory responses, although with decreased quantity in patients with POI.

Association between B cell subsets and ovarian reserve of POI

To assess whether the B-subset disturbance in POI patients is related to disease severity, we performed correlation analyses between proportions of distinct B subpopulations and ovarian reserve markers. We found that the proportion of CD19+ B cells exhibited a positive correlation with the basal FSH level (r = 0.3903, p < 0.0001) and negative correlations with the serum AMH level (r = -0.4353, p < 0.0001) and AFC (r = -0.3029, p = 0.0016). The basal AMH level was positively correlated with the proportion of class-switched memory B cells (r = 0.4703, p = 0.0003) (Fig. 3A). Additionally, the proportion of CD19+CD24hiCD27+ Bregs demonstrated a negative correlation with the basal FSH level (r = -0.4160, p = 0.0016), but a positive correlation with the serum E2 level (r = 0.4249, p = 0.0021), AMH level (r = 0.4575, p = 0.0007) and AFC (r = 0.4979, p = 0.0002). Meanwhile, the proportion of CD19+CD24hiCD38hi Bregs also showed a positive correlation with the serum AMH (r = 0.4009, p = 0.0036) (Fig. 3B). Consequently, the aberrations observed in peripheral B cells and Breg subsets in POI were significantly associated with a diminished ovarian reserve.

A Correlation analysis illustrating relationships between B cell subset proportions and ovarian reserve indicators. B Correlation analysis examining association between Breg cell ratio and ovarian reserve indicators. Spearman's correlation analysis was used. Sample sizes are indicated in each figure. The n values vary across analyses due to missing clinical hormone data from some donors, rather than selective inclusion or exclusion of samples.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively characterized disturbances in peripheral B cell subsets in patients with POI, and found significantly increased total B cells compared to control women. For the B-subset distribution, there were reduced percentages of MBCs and plasmablasts in patients with POI, although with no difference in naïve and TrB population between the two groups. Additionally, we found decreased quantity in Bregs but with intact suppressive capacity on T cell inflammatory responses in POI patients. Notably, the dysregulated B cell subsets showed significant correlations with a decline in ovarian reserve. Collectively, our preliminary data indicated that the abnormal peripheral B cell subsets distribution might be related to the proinflammatory microenvironment in POI, which provides new evidence of autoimmune imbalance in POI.

Autoimmune dysregulation emerges as a pivotal contributor to the pathogenesis of POI. Systemic inflammatory conditions exert an adverse influence on follicular dynamics, resulting in a perturbation of ovarian homeostasis5,37,38. B cells play crucial regulatory functions in the systemic and local immune response. In addition to antibody production, they contribute to inflammation by secreting inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), while simultaneously exerting a suppressive effect on excessive inflammation through the secretion of IL-10 and the metabolism of extracellular ATP to ADP39,40,41,42. While prior research has predominantly centered on T cell-related immune irregularities, such as the imbalance between TH1 and Tregs15,16,43, the role of B cell subsets in POI remains unclear. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the distribution, phenotypic characteristics, and functional dysfunctions of B cell subsets in POI patients. We report herein for the first time the comprehensive characterization of peripheral B cells in individuals affected with POI. In the majority of autoimmune diseases, B cells are generally considered to be pathogenic because of their capacity to secrete autoantibodies. Prior studies in the 1990s consistently reported an increased proportion of B cells in the peripheral blood of POI patients34,40,44. In line with earlier findings, our study reaffirms the observation of an elevated proportion of total peripheral B cells in POI patients. The increased B cells in peripheral blood may be due to their autoreactive nature and augmented expansion, thereby substantiating the notion that POI falls within the category of autoimmune endocrine disorders. However, B cell expansion could also reflect hormonal changes, particularly estrogen deficiency, which is known to affect B cell maturation, activation, and survival45,46. Therefore, further mechanistic studies are warranted to clarify whether these alterations are secondary to hormonal imbalance or part of an autoimmune process contributing to ovarian dysfunction.

Of note, the specific distribution and functional implications of B cell subsets in the peripheral milieu of individuals with POI have remained inadequately elucidated. Our findings revealed an overall increase in circulating B cells in POI patients. This expansion occurred despite significant reductions in memory B cells and plasmablasts, while naïve and transitional B cell populations remained largely unchanged. Given that naïve B cells represent the predominant subset in peripheral blood, even a modest and statistically non-significant increase in their proportion may contribute disproportionately to the observed overall elevation in total B-cell percentage. Moreover, the observed reduction in both subsets of MBCs, despite an overall increase in total B proportions, indicated a functional impairment that preferentially affects in these memory B populations. MBCs are essential for maintaining long-term immune surveillance, and their reduction in POI parallels findings in other autoimmune diseases, such as SLE. The decline of MBCs has been reported to be associated with an activated phenotype, enhanced migratory capacity toward CXCR4 ligands, and increased autoreactivity47. Although a significant positive correlation between the proportion of class-switched MBCs and AMH levels was observed, the functional phenotypes of MBCs were not available in our study and further exploration is warranted in POI patients. These observations collectively imply a plausible association between dysregulated B cell subsets and both ovarian reserve function and the severity of POI. These results provide novel insights into the immunological underpinnings of POI, underscoring the relevance of abnormalities in B cell subsets concerning the disease’s severity.

The delicate balance between pathogen-induced effector functions and endogenous tolerance-mediating mechanisms is of vital importance to the integrity of immune response. So far, maintenance of this immune balance has been mainly attributed to Tregs48. Human Bregs are also important for maintenance of immunological homeostasis and self-tolerance, particularly they inhibit the differentiation of proinflammatory cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells in a dose- and contact-dependent manner49. Consistent with reports in other autoimmune diseases like SLE and systemic sclerosis (SSc)50,51, we found that Bregs are numerically deficient in patients with POI. Consistent with previous reports22,35, we analyzed IL-10 production within total CD19⁺ B cells, as IL-10 competence serves as the most reliable functional indicator of regulatory activity regardless of phenotypic heterogeneity. Although the CD19+CD24hiCD27+ and CD19+CD24hiCD38hi subsets are enriched for Bregs, they are not phenotypically exclusive. Functionally, the CD19+CD24hiCD27+ subset was used as a Breg-enriched population to evaluate overall suppressive capacity in co-culture with autologous CD4⁺ T cells. Although IL-10-producing B10 cells were reduced in patients with POI, the overall suppressive function of this Breg-enriched population remained intact. These results suggest that the reduction in IL-10 competence may not necessarily translate to a loss of the capacity to suppress T-cell-derived inflammatory cytokine responses.

Here, we not only identified a substantial reduction in IL-10 production by B cells in POI patients, but also pinpointed a reduced proportion of two predominant Breg subsets: CD19+CD24hiCD27+ and CD19+CD24hiCD38hi Bregs. Notably, both Breg subsets exhibited a significant association with diminished ovarian reserve function. While Bregs retained their ability to suppress T cell inflammatory responses, the overall reduction in proportion in POI patients may result in an insufficient counterbalance to the proinflammatory environments driven by other immune cells, such as TH1, TH17 or activated B cells, which are known to be autoreactive and proinflammatory52,53. Our previous studies and others have identified augmented TH1 response and deficiency in Tregs in patients with POI15,16,17. Here, we confirmed our previous data that decreased IL-10 level in periphery in POI patients, and our current study thus added Bregs as a new cellular source of dysregulated inhibitory cytokines in POI. The combined effect of decreased quantity of immune regulatory populations, Tregs and Bregs, might cooperatively contribute to the disruption of immune tolerance and trigger augmented TH1 proinflammatory responses in patients with POI15,16,17. Further studies to elucidate the functional relevance of the decreased Breg proportion with ovarian dysfunction in vivo, such as Breg depletion using anti-CD20 antibodies or genetic mouse models with IL-10-specific knockout in CD19+ B cells, are warranted.

Our comprehensive characterization of peripheral B cell subsets in a well-defined cohort of POI patients provides detailed insights into immune alterations that have not been extensively studied in this population. The significant correlations between dysregulated B cell subsets and diminished ovarian reserve further suggest an important role of immune dysfunction in POI pathophysiology. Furthermore, the specific alteration in B subsets could serve as potential biomarkers or targets for therapeutic intervention. Specifically, tracking these B subset shifts may provide insights into immune dysregulation in POI, offering potential for earlier detection, especially in women at risk for ovarian insufficiency. Further research in B-cell-directed therapies or efforts in Breg cell engineering to enhance their specificity, stability, and functional activity may open new avenues for personalized management of POI, especially for those with an autoimmune component53,54.

There remain some limitations in our study. First, the sample size for individual B cell subsets was relatively small, which might result in a high risk of a Type II error. Second, we did not have the alteration in the absolute counts of B subsets, further studies on both the proportion and absolute counts will enhance the interpretation the comprehensive immune profiles in patients with POI. Third, we did not extensively investigate whether the B abnormalities are causative factors or consequences of POI. A longitudinal study within a large POI population would allow us to observe the trajectory of relevant indicators in correlation with disease severity. Additionally, it is possible that some patients have undiagnosed or subclinical autoimmune conditions that also affect the observed B cell alterations. However, we have excluded the most common ones that are contaminated with POI in our cohort. Lastly, while POI is increasingly recognized as an inflammatory condition, our study specifically focused on IL-10 and B cell subsets. Nonetheless, the precise mechanism linking these altered B cell populations, and other cytokine pathways, and the subsequent deterioration of ovarian reserve function remains to be fully elucidated and represents a critical avenue for future investigation.

In conclusion, our study presents compelling evidence supporting the existence of B-subset abnormalities in patients with POI, which might contribute to immune dysregulation and exhaustion of ovarian reserve. Our results also shed further light on new insights into autoimmune pathogenesis and clues for novel therapeutic interventions for patients with POI. Further validation in a larger, independent population of individuals with idiopathic POI is warranted to comprehensively elucidate the aberrant B cell profile in POI patients.

Methods

Human subjects

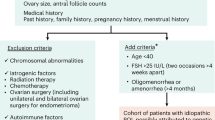

The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Center for Reproductive Medicine, Shandong University, and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating volunteers prior to sample collection. A total of 144 women, including 66 patients with POI and 78 control women, were recruited from the Center for Reproductive Medicine, Shandong University, China, between April 2021 and September 2023. Inclusion criteria for the POI group involved oligo/amenorrhea for at least four months, and a basal serum FSH > 25 IU/L (on two occasions with an interval of more than one month) prior to the age of 402,33. Control participants had regular menstrual cycles and FSH levels < 10 IU/L, seeking infertility treatment for tubal obstruction or male factors. Exclusion criteria included chromosomal abnormalities, known gene mutations, history of ovarian surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, recurrent spontaneous abortions, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and hormone therapy within the preceding three months. Autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis, SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, allergic purpura, Addison’s disease, and autoimmune thyroiditis, were routinely checked. Participants with known autoimmune diseases and positivity for autoimmune antibodies (TPOAb, TGAb, AAA), were also excluded. A flow chart depicting the participant recruitment and assays is provided in Supplemental Fig. 1, and detailed baseline characteristics are in Table 1.

Hormone measurement and pelvic ultrasonography

Peripheral blood samples were collected from all participants, either on days 2-4 of the menstrual cycle or randomly in instances of infrequent menstruation. Endocrine hormones, including levels of FSH, luteinizing hormone (LH), E2, and total testosterone were quantified through a chemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Kangrun Biotech). The coefficients of variation for both intra-assay and inter-assay precision were < 10%. The most recent values of hormone measurement before or at patient recruitment were used for patient characteristics and correlation analysis. Transvaginal ultrasonography was routinely performed, and antral follicle count (AFC) was determined as the number of bilateral follicles (2–10 mm in diameter) in the early follicular phase.

Human Cell Isolation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque (MP Biomedicals, USA) gradient centrifugation. B cell subsets, and autologous CD4+ T cells were sorted by a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Pharmingen) based on their expression of CD3, CD4 or CD19, CD24, and CD27. Dead cells were excluded using 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (BD Pharmingen). Sorting purity of both subsets was routinely > 95%.

Cell culture and in vitro stimulations

PBMCs were cultured at a concentration of one million cells per milliliter in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were stimulated for 48 hours with recombinant human CD40L (1 μg/mL, R&D Systems) plus CpG ODN 2006 (10 μg/mL, InvivoGen) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Brefeldin A (10 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) was added for the last 5 h along with phorbol myristate acetate (50 ng/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (1 µg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Isolated human cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Zombie Yellow or Aqua Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend, USA) was used to exclude dead cells from flow cytometric analysis. For cell-surface staining, we incubated a total of 106 cells per sample with combinations of CD19-Alexa Fluor 700 (Biolegend), CD38-FITC, CD24-Super Bright 645, IgD-PerCP-eFluor 710, and CD27-Super Bright 780 (Invitrogen) in staining buffer (PBS and 1% FBS) for 15 min at room temperature in the absence of light. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with Cell Activation Cocktail (BioLegend) at 37 °C for 4 h, followed by fixation and permeabilization using the Fixation/Permeabilization buffer solution (BD Biosciences) at 4 °C for 20 min. Cells were stained for detection of intracellular cytokines with IL-10-eFluor 660 mAbs (Invitrogen). Stained cells were acquired using an LSR Fortessa cell analyzer (BD Biosciences) and the data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Version 10.6.1, BD Biosciences, USA).

B-cell functional assays

The CD19+CD24hiCD27+ B cells were stimulated with CpG at a concentration of 10 μg/mL, in combination with CD40L at a concentration of 1 μg/mL, for a duration of 24 h. The CD3+CD4+ T cells were cultured either alone (106 cells/mL) or co-cultured with CD40L/CpG-stimulated B cells (1:1) in 96-well plates coated with CD3 monoclonal antibody (1 μg/mL) for 72 hours. Cell Activation Cocktail was added for the last 5 h. Cells were surface-stained, permeabilized, stained for detection of intracellular cytokines with IFN-γ-Brilliant Violet 711, TNF-α-PE (Biolegend), and IL-10-eFluor 660 mAbs (Invitrogen), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical analyses using PASS v15.0.13 (NCSS, USA), SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc., USA), R Studio, and GraphPad Prism 9 (San Diego, USA). Based on data from previous studies34,35,36, we calculated the effect size (Cohen’s d) to be 0.866. With a significance level (α) set at 0.05, a sample size of 106 participants (Controls = 53, Patients = 53) was determined to be sufficient to achieve a statistical power of 0.80.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for assessing normality. Baseline characteristics that followed a normal distribution [age, LH, progesterone (P), testosterone (T), and free thyroxine (T4)] were analyzed by the two-tailed Student’s t-test, and are presented as mean ± SEM. Non-normally distributed variables [body mass index (BMI), age at menarche, duration of infertility, FSH, E2, prolactin (PRL), AMH, AFC, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and free triiodothyronine (T3)] were compared using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, and are expressed as median (quartile). Among these, naïve B cells, class-switched MBCs, non-class-switched MBCs, and CD19+IgD⁻CD27⁻ cells constitute compositional data and were therefore analyzed using Dirichlet regression implemented with the DirichletReg package in R. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between immune indicators and ovarian reserve biomarkers. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Faubion, S. S., Kuhle, C. L., Shuster, L. T. & Rocca, W. A. Long-term health consequences of premature or early menopause and considerations for management. Climacteric : J. Int. Menopause Soc. 18, 483–491 (2015).

Webber, L. et al. ESHRE Guideline: management of women with premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. (Oxf., Engl.) 31, 926–937 (2016).

Li, M. et al. The global prevalence of premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Climacteric : the Journal of the International Menopause Society 26, https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2022.2153033 (2023).

Ford, E. A., Beckett, E. L., Roman, S. D., McLaughlin, E. A. & Sutherland, J. M. Advances in human primordial follicle activation and premature ovarian insufficiency. Reproduction 159, R15–R29 (2020).

Kirshenbaum, M. & Orvieto, R. Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) and autoimmunity-an update appraisal. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 2207–2215 (2019).

Petríková, J. & Lazúrová, I. Ovarian failure and polycystic ovary syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 11, A471–A478 (2012).

Silva, C. A. et al. Autoimmune primary ovarian insufficiency. Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 427–430 (2014).

Hsieh, Y. T. & Ho, J. Y. P. Thyroid autoimmunity is associated with higher risk of premature ovarian insufficiency-a nationwide Health Insurance Research Database study. Hum. Reprod. 36, 1621–1629 (2021).

Bensing, S., Giordano, R. & Falorni, A. Fertility and pregnancy in women with primary adrenal insufficiency. Endocrine 70, 211–217 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Association between thyroid autoimmunity and the decline of ovarian reserve in euthyroid women. Reprod. Biomed. Online 45, 615–622 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. Identification of patients with primary ovarian insufficiency caused by autoimmunity. Reprod. Biomed. Online 35, 475–479 (2017).

Sharata, E. E. et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian injury and protective strategies. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s archives of pharmacology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-025-04550-9 (2025).

Mauri, C. & Bosma, A. Immune regulatory function of B cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 30, 221–241 (2012).

Gupta, P., Chen, C., Chaluvally-Raghavan, P. & Pradeep, S. B Cells as an immune-regulatory signature in ovarian cancer. Cancers 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11070894 (2019).

Jiao, X. et al. Treg deficiency-mediated TH 1 response causes human premature ovarian insufficiency through apoptosis and steroidogenesis dysfunction of granulosa cells. Clin. Transl. Med. 11, e448 (2021).

Kobayashi, M. et al. Decreased effector regulatory T cells and increased activated CD4+ T cells in premature ovarian insufficiency. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 81, e13125 (2019).

Liu, D. et al. Adoptive transfers of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs partially alleviate mouse premature ovarian insufficiency. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 87, 887–898 (2020).

Zhang, W. et al. The T(H) 22-mediated IL-22 deficiency associated with premature ovarian insufficiency. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 89, e13685 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. The dynamic profile and potential function of B-cell subsets during pregnancy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18, 1082–1084 (2021).

Lin, W. et al. Circulating plasmablasts/plasma cells: a potential biomarker for IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 19, 25 (2017).

Rouers, A. et al. CD27(hi)CD38(hi) plasmablasts are activated B cells of mixed origin with distinct function. iScience 24, 102482 (2021).

de Mol, J., Kuiper, J., Tsiantoulas, D. & Foks, A. C. The dynamics of B cell aging in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 12, 733566 (2021).

Szabó, K., Papp, G., Szántó, A., Tarr, T. & Zeher, M. A comprehensive investigation on the distribution of circulating follicular T helper cells and B cell subsets in primary Sjögren’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 183, 76–89 (2016).

Nocturne, G. & Mariette, X. B cells in the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren syndrome. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 14, 133–145 (2018).

Yurasov, S. et al. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 201, 703–711 (2005).

Iwata, Y. et al. Characterization of a rare IL-10-competent B-cell subset in humans that parallels mouse regulatory B10 cells. Blood 117, 530–541 (2011).

Kalampokis, I., Yoshizaki, A. & Tedder, T. F. IL-10-producing regulatory B cells (B10 cells) in autoimmune disease. Arthritis Research & Therapy 15 S1, https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3907 (2013).

Braza, F. et al. A regulatory CD9(+) B-cell subset inhibits HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation. Allergy 70, 1421–1431 (2015).

Jansen, K. et al. Regulatory B cells, A to Z. Allergy 76, 2699–2715 (2021).

Ma, L., Liu, B., Jiang, Z. & Jiang, Y. Reduced numbers of regulatory B cells are negatively correlated with disease activity in patients with new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 33, 187–195 (2014).

Sorrentino, R. et al. B cells contribute to the antitumor activity of CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide in a mouse model of metastatic lung carcinoma. Am. J. Respiratory Crit. Care Med. 183, 1369–1379 (2011).

Aharoni, R. et al. Glatiramer acetate increases T- and B -regulatory cells and decreases granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 345, 577281 (2020).

Chen, Z. J., Tian, Q. J. & Qiao, J. Chinese expert consensus on premature ovarian insufficiency]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 52, 577–581 (2017).

Hoek, A. et al. Analysis of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, NK cells, and delayed type hypersensitivity skin test in patients with premature ovarian failure. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 33, 495–502 (1995).

van Kasteren, Y. M. et al. Incipient ovarian failure and premature ovarian failure show the same immunological profile. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 43, 359–366 (2000).

Verma, P., A, K. S., Shankar, H., Sharma, A. & Rao, D. N. Role of trace elements, oxidative stress and immune system: a triad in premature ovarian failure. Biol. trace Elem. Res. 184, 325–333 (2018).

Boots, C. E. & Jungheim, E. S. Inflammation and human ovarian follicular dynamics. Semin. Reprod. Med. 33, 270–275 (2015).

Harris, B. S., Steiner, A. Z., Faurot, K. R., Long, A. & Jukic, A. M. Systemic inflammation and menstrual cycle length in a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Obstetrics Gynecol. 228, 215.e1–215.e17 (2023).

Chekol Abebe, E. et al. The role of regulatory B cells in health and diseases: a systemic review. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 75–84 (2021).

Hoek, A., Schoemaker, J. & Drexhage, H. A. Premature ovarian failure and ovarian autoimmunity. Endocr. Rev. 18, 107–134 (1997).

Shen, P. & Fillatreau, S. Antibody-independent functions of B cells: a focus on cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 441–451 (2015).

Zhang, F. et al. Specific Decrease in B-Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Enhances Post-Chemotherapeutic CD8+ T Cell Responses. Immunity 50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.010 (2019).

Liu, P. et al. Dysregulated cytokine profile associated with biochemical premature ovarian insufficiency. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 84, e13292 (2020).

Ho, P. C., Tang, G. W., Fu, K. H., Fan, M. C. & Lawton, J. W. Immunologic studies in patients with premature ovarian failure. Obstet. Gynecol. 71, 622–626 (1988).

Grimaldi, C. M., Cleary, J., Dagtas, A. S., Moussai, D. & Diamond, B. Estrogen alters thresholds for B cell apoptosis and activation. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 1625–1633 (2002).

Kasibante, J., Brown, T. T., Lake, J. E. & Abdel-Mohsen, M. Estrogen modulation of B cell immunity: implications for HIV control and therapeutic strategies. Compr. Physiol. 15, e70050 (2025).

Rodriguez-Bayona, B., Ramos-Amaya, A., Perez-Venegas, J. J., Rodriguez, C. & Brieva, J. A. Decreased frequency and activated phenotype of blood CD27 IgD IgM B lymphocytes is a permanent abnormality in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 12, R108 (2010).

Blair, P. A. et al. CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Immunity 32, 129–140 (2010).

Catalán, D. et al. Immunosuppressive mechanisms of regulatory B cells. Front. Immunol. 12, 611795 (2021).

Matsushita, T., Hamaguchi, Y., Hasegawa, M., Takehara, K. & Fujimoto, M. Decreased levels of regulatory B cells in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with autoantibody production and disease activity. Rheumatology 55, 263–267 (2016).

Mauri, C., Gray, D., Mushtaq, N. & Londei, M. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10-producing B cells. J. Exp. Med. 197, 489–501 (2003).

Cui, D. et al. Changes in regulatory B cells and their relationship with rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Clin. Exp. Med 15, 285–292 (2015).

Shang, J., Zha, H. & Sun, Y. Phenotypes, functions, and clinical relevance of regulatory B cells in cancer. Front Immunol. 11, 582657 (2020).

Stensland, Z. C., Cambier, J. C. & Smith, M. J. Therapeutic Targeting of Autoreactive B Cells: why, how, and when? Biomedicines 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9010083 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in the current study. We would like to acknowledge the support provided by Tao Yan from the Flow Cytometry Facility for cell sorting, as well as our funders. Funding for this work came in part from the Mingcheng Innovation Postdoctoral Research Fund of the Gusu School, Nanjing Medical University (GSBSHKY202401). We also acknowledge support from the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024QH161). This project was also funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022MH009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Y.L. and K.R. contributed to the design research studies. Y.S.L., H.B.Z., C.J.W., P.X.S., S.T.M., Y.J.D., W.Z.Z., and J.T.Z. conducted experiments; P.X.S., S.T.M., Y.J.D., and W.Z.Z. collected the clinical samples; C.J.W. and P.X.S. contributed to acquisition of hormones and sonography; Y.S.L., H.B.Z., C.J.W., P.X.S., S.T.M., and Y.J.D. contributed to flow cytometry; P.X.S., S.T.M., and W.Z.Z. contributed to the cell culture; Y.S.L. and H.B.Z. analyzed and interpreted the data; Y.S.L., H.B.Z., N.Y.L., and K.R. drafted the manuscript and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Zhu, H., Wang, C. et al. Peripheral B cell alteration in patients with premature ovarian insufficiency. npj Aging 12, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00302-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-025-00302-4