Abstract

Auditory gamma stimulation is a promising non-invasive neuromodulation technique for cognitive decline, with preclinical studies demonstrating therapeutic effects in Alzheimer’s disease models. However, translating these findings into human trials has produced variable outcomes, suggesting a need to examine factors influencing efficacy. In a systematic review of 62 studies on healthy and cognitively impaired populations, we identified 16 characteristics that may affect the response to stimulation. Outcomes reported included improved cognition, slower progression of brain atrophy, and changes in functional connectivity. Optimal stimulation frequency varied across individuals, indicating that personalised approaches may be valuable. Importantly, animal-model findings regarding amyloid clearance and reduced neuroinflammation were not consistently replicated in human studies, nor did neurophysiological responses reliably predict cognitive or biological effects. Significant methodological diversity was evident, with 32 neurophysiological measures employed, highlighting a need for standardisation. Future research should prioritise consensus on outcome measurement and explore individualised intervention strategies to better assess therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia currently affects an estimated 57 million individuals worldwide, with projections indicating a rise to 75 million by 2030 and 152 million by 20501. While pharmacological treatments for dementia are on the rise, they have yet to provide effective solutions for all individuals, prompting increased interest in alternative approaches such as non-invasive brain stimulation. Among the various causes of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounts for 60–80% of cases and is characterised by distinct alterations in neural gamma oscillatory dynamics2,3 including impaired cross-frequency coupling, and disruptions in network-level gamma coherence4.

Gamma oscillations (30–80 Hz) arise primarily from interactions between fast-spiking parvalbumin-expressing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic interneurons and excitatory pyramidal neurons and support both local processing and interareal coherence5,6,7,8. Measured by electroencephalography (EEG)9 or magnetoencephalography (MEG)10, these oscillations contribute to essential cognitive functions including attention, visual processing, working memory, reasoning, and executive function11,12,13,14, while disruptions in gamma activity have been implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders15,16,17,18,19.

Brain oscillations can be modulated through repetitive stimulation, a process known as entrainment, which aligns oscillations to an external rhythm20. Given the link between aberrant gamma oscillations and cognitive dysfunction3,21, entrainment is proposed to improve cognition by restoring normal gamma activity22 and enhancing neural processing efficiency23. Various non-invasive methods have been employed to induce gamma entrainment, including transcranial electrical or magnetic stimulation24,25 and sensory stimulation, such as flickering light (visual)26 or periodic clicks (auditory)27, with sensory methods offering superior comfort and ease of use28,29. Research has found that gamma entrainment via these means has been associated with enhanced performance in motor processes30, perception31, attention32, and memory33,34 in healthy individuals. Importantly, gamma oscillations and the cognitive functions they support are disrupted in AD, suggesting that gamma entrainment may represent a potential therapeutic to restore aberrant oscillatory activity and, thus, the associated cognitive processes16.

Consequently, the potential of sensory gamma entrainment as a therapeutic for cognitive decline in dementia, specifically in AD, is rapidly gaining traction. In a seminal study, Iaccarino et al.35 demonstrated that visual entrainment of 40-Hz oscillations in the hippocampus of AD mouse models significantly reduced amyloid-beta (Aβ) levels, a hallmark of AD pathology36,37, and activated microglia, suggesting enhanced amyloid clearance through increased endocytosis and reduced amyloidogenesis38,39. Subsequent studies using 40-Hz sound and light stimulation have largely corroborated these findings, showing not only reduced Aβ deposition extending beyond the sensory cortices40,41 but also broader neuroprotective effects, including improved synaptic function, enhanced neuronal integrity, reduced inflammation and reversal of deficits in long-term potentiation, which is critical for learning and memory42,43.

The promising results from animal studies have catalysed a surge of clinical trials exploring the therapeutic potential of gamma entrainment in AD. While preclinical models demonstrate reductions in amyloid pathology and neuroinflammation35,42,43, translating these findings to humans has proven to be more complex. A recent review examines the differences between preclinical and clinical findings, noting that while animal models show robust effects on pathology and cognition, clinical trials demonstrate mixed outcomes, with only modest effects observed to date in some human studies44. The precise mechanisms by which sensory stimulation interacts with neural oscillations and AD pathology require further investigation and likely vary across brain regions and disease stages.

One explanation for the inconsistent replication of neuroprotective effects of sensory gamma stimulation in humans may stem from individual and group differences in responsiveness to neuromodulation45. Factors such as neurotransmitter balance, brain state, age, and sex influence the response to electrical neuromodulation46,47, with neuroanatomical and neurophysiological variability significantly predicting its efficacy48. Indeed, age has been associated with changes in evoked gamma and altered neural dynamics, possibly reflecting structural brain changes and shifts in neurotransmitter function49,50,51. Importantly, both electrical and magnetic neuromodulation have been shown to elicit stronger neural effects in younger individuals, with comparatively attenuated responses observed in older populations52,53. Similarly, sex differences in brain structure and functions, including greater cortical thickness54, hormonal fluctuations55, and variations in neurotransmitter levels56, may contribute to stronger and more synchronised gamma oscillations in females compared to males57,58.

Importantly, disease-related factors may influence gamma oscillations and the neuromodulatory response. AD, in particular, has been associated with reduced gamma power and synchronisation at rest59,60,61. While neuromodulatory techniques have demonstrated improvements in cognitive performance in mild cognitive impairment (MCI)62,63, one review highlights that, across diverse gamma neuromodulation approaches, clinical research in AD remains limited, with small-sample trials reporting variable but some positive cognitive outcomes64. Variable outcomes of neuromodulation may relate to atrophic changes which progressively increase with disease severity65. Damage to white matter tracts in late-stage neurodegeneration66 impairs signal propagation, even with successful entrainment in localised regions67. It may therefore be important to consider individual differences in the context of disease stage when applying neuromodulatory interventions to patients with AD.

Consequently, personalised approaches have been applied in some neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), where parameters are adjusted to maximise efficacy for each individual68. Yet, the influence of individual differences on treatment outcomes with sensory gamma entrainment remains largely unexplored.

This systematic review examines whether specific groups and/or individuals exhibit distinct responses to auditory gamma stimulation to consider how these variations may influence downstream cognitive and biological effects, with a view towards preventing cognitive decline. There is a notable gap in the literature bridging preclinical and clinical findings in sensory stimulation, with limited exploration of individual variability in human studies. Understanding both individual and group-level factors is essential, especially as research on sensory gamma entrainment for neurodegeneration rapidly expands. As auditory stimulation appears the most effective sensory modality for entrainment when delivered alone, we focus our search on auditory stimulation, including studies that incorporate simultaneous visual stimulation (audiovisual) which has been shown to enhance the entrainment response69,70.

To address this knowledge gap, our review has three objectives. First, to examine how individual characteristics influence the effectiveness of auditory (and audiovisual) gamma stimulation for entrainment in the healthy population and the associated effects on cognition and behaviour. Second, evaluate how the efficacy and outcomes of auditory gamma stimulation differs between neurological conditions associated with cognitive decline and healthy populations. Finally, explore how individual characteristics interact with clinical conditions in response to auditory gamma stimulation to influence therapeutic outcomes.

Results

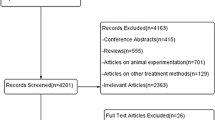

The initial search retrieved 3,754 records from the databases included and 94 records from the clinical trial registers (Fig. 1). Following limits and the removal of duplicate records, the database search was reduced to 1209 reports. This search was reconducted one month before data extraction for inclusion in the final sample to capture any newly added records and resulted in an additional seven records, amounting to 1310 records for screening. At this stage, the manual citation searching and AI search were conducted, yielding an additional 21 records for screening. Following title screening, abstracts and full texts of 336 records were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 76 met the inclusion criteria: 14 were clinical trials that were either ongoing or available only as abstracts (included in Supplementary Data 6) to highlight current studies investigating auditory gamma stimulation as an intervention for neurological conditions associated with cognitive decline. The remaining 62 studies were included in the main synthesis.

*Other reasons for exclusion included insufficient information reported for data extraction, duplication of studies under different titles (e.g., preprint and published version), and clinical conditions outside the scope of the current review, such as psychiatric disorders or loss of consciousness. **Papers were also excluded where the full text could not be retrieved despite searching across databases and other online sources.

Reasons for exclusion included non-human samples, records without data included (e.g. review papers), designs using a different sensory modality or frequency band for stimulation, studies with outcome measures not relevant to the topics at hand, studies investigating the influence of an external factor (e.g. stimulus intensity) on the entrainment response, duplication of studies under different titles (e.g. preprint and published version), and clinical conditions outside the scope of the current review (e.g. psychiatric disorders). Sixteen records were additionally excluded as they consisted of a conference abstract only, meaning quality assessment could not be conducted, and many overlapped with later published articles included in the review. Across the 62 studies included in the main synthesis, a total of 2179 participants were examined. Sample sizes ranged from four to 181 participants. Study designs comprised 11 observational, 43 experimental, two longitudinal, and six clinical trials. Participant ages ranged from three months to 75 years.

Four key themes emerged from the studies selected for data extraction: Theme 1) individual differences affecting the entrainment response in healthy populations, and sub-theme 1a) neurodevelopmental conditions affecting entrainment (Table 1 (Supplementary Data 1), Table 1a (Supplementary Data 2) respectively); Theme 2) clinical conditions affecting the entrainment response (Table 2, Supplementary Data 3); Theme 3) cognitive and biological effects of entrainment in healthy and clinical populations (Table 3, Supplementary Data 4); Theme 4) optimisation of stimulation frequency in healthy and clinical populations (Table 4, Supplementary Data 5). Outcome measures in Themes 1, 1a, 2, and 4 comprise neurophysiological measures of entrainment, typically EEG measures, with a note included where MEG was instead (Tables 1, 1a, 2, and 4). While studies investigating gamma stimulation in individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions do not strictly fall under our predefined categories of healthy individuals or those with cognitive decline, there was no strong rationale to exclude them. In line with the growing recognition that ADHD and ASD represent neurodevelopmental differences rather than inherently “unhealthy” conditions, we treated these populations as reflecting trait-level variability relevant to entrainment. They have been included as a sub-theme of Theme 1. Outcome measures for Theme 3 comprise measures of cognitive function including task performance or clinical assessments, and measures of biological change, including both neurobiological measures (e.g., brain atrophy, functional connectivity) and physiological responses (e.g., sleep quality, adverse events) (Table 3). Stimulation protocol details are provided in the tables.

One additional table (Supplementary Data 6) has been included as part of the supplementary material (S3) to highlight the current clinical trials investigating auditory gamma stimulation as an intervention for neurological conditions with cognitive decline. A final judgement for overall risk of bias as per the appropriate quality assessment tool (AXIS, RoB 2, or ROBINS-I) has been included in each table with the full quality assessments found in the Supplementary Material (S4, Supplementary Data 7, 8, and 9, respectively). Across all included studies, 48 were judged to be at low risk of bias, 12 at moderate risk, and 2 at high risk. The two high-risk studies were characterised by limited information about the participant sample and insufficient statistical reporting; they were included in the tables for completeness but were not used to inform the interpretation of the results. Table of entrainment measures and definitions provided in Table 5.

Twenty-four of the articles retrieved investigated the effect of different traits on gamma-band entrainment responses (Table 1, Table 1a)71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94. Nine of these specifically examined the association between age and entrainment71,78,79,82,83,86,90,91,93. While infants did not exhibit a 40-Hz response when measured by AMFR91, power at 40 Hz was found to increase linearly from age five and stabilise in early adulthood, with concomitant increases in amplitude variability86. Another study reports that power, PLF, and CFC increased from ages eight to 16 years before decreasing between 20 and 2282. A linear decline in evoked amplitude and PLI with age was reported, though their total intensity measure remained unaffected71. ITPC was found to increase with age78,79, while ERF78 and STP decreased79. Contextual factors moderated the effects of age, whereby quiet conditions increased 40-Hz amplitude in younger adults compared to older adults93, while attention significantly enhanced 40-Hz amplitude in older adults but not children90. One study found no effects of age on entrainment83.

Other traits identified included processing speed, where reaction time (RT) was negatively correlated with PLI and ERSP at individual optimal gamma entrainment frequencies and at 40 Hz, indicating that subjects with better gamma synchronisation were faster to execute behavioural responses74. Attention appeared to enhance the entrainment response, as SNR improved when participants were instructed to attend to the 40-Hz stimuli92, while GFS weakened when participants were distracted from the auditory input85. However, one study found no effect of attention on ITC or energy80.

Neuroanatomical differences were also linked to variations in entrainment, with increased cortical thickness associated with increased PLV and ITPC75, and myelination in the right cerebellum corresponding to increased PLV76. Long-term lifestyle factors were also associated with variability, such as musical training, which showed some association with larger PLVs at 40 Hz77, and shortening of ASSR phase, but no change in amplitude84, and chronic cannabis use, which was associated with reduced gamma power81.

Stable traits such as handedness and sex revealed reduced PLI and ERSP of 40 Hz in left-handed females compared to right- and left-handed males72. Variable physiological states, such as the current phase of the menstrual cycle73 and GABAergic neuronal inhibition87 affected PLI and amplitude, and total power, of the gamma-band response, respectively. Moreover, emotional arousal, induced via emotional video clips, affected entrainment response, with stronger ASSRs found (measured by PtP and ERSP) in positive compared to neutral or negative emotional states88.

Importantly, of all traits studied, none were found to affect the neural response to the extent that entrainment could not be achieved, with the exception of age in very young children, though this was only observed when measured by AMFR.

Five studies explored how neurodevelopmental conditions, including ASD, ADHD, and dyslexia, affect entrainment79,95,96,97,98. Higher phase coherence and SNR were reported in individuals with dyslexia97, however, another study found minimal differences between dyslexic and control groups when assessing SNR, PLV, IHPS, and coherence95. Adults with ASD demonstrated reduced 40-Hz power and ITC96. Older adults with ASD also showed reduced ITPC, but this was not found in younger adults with ASD79. Those with ADHD showed reduced amplitude with 40-Hz stimulation only in the pre-medication condition and not after receiving their daily stimulant medication98.

Of the seven articles retrieved examining the effect of clinical conditions on the entrainment response, all but one focused on dementia, including MCI, AD, and non-AD dementia99,100,101,102,103,104,105. The remaining study investigated the entrainment response, as measured by phase and RMS power, among patients with lesions affecting the midbrain or temporal lobe106. All studies were successful in inducing gamma entrainment in dementia patients to some degree, as determined by ASSR threshold, power, amplitude, PLV, and PAC. ASSR thresholds105, power101,103, and amplitude103 were significantly higher in AD compared to controls, with ASSR thresholds and power also significantly elevated in AD patients relative to MCI101,105. Improved neural synchronisation and connectivity in MCI and AD patients, indexed by PLV, between intraregional and interregional sites were found, with the strongest effects shown in MCI patients99. Interestingly, one feasibility study102 found that the entrainment response was spread across multiple areas in a cognitively normal participant group but concentrated around frontal regions in mild AD (measured by PSD and coherence), possibly reflecting disease-related changes in sensory stimulation response.

However, Lahijanian et al.100 claimed that a sufficient standard of entrainment was achieved for only a subset of their study’s participants, based on their proposed definition of the ‘entrained’ brain; a peak frequency amplitude response at the stimulation frequency at least three standard deviations above the mean amplitude response in a range of adjacent frequencies. The authors additionally found that higher theta power (4 – 8 Hz) at rest predicted quality of entrainment in dementia patients, indexed by an averaged z-score value of the 40-Hz component’s amplitude, an example of an individual difference influencing the neural response within a clinical population.

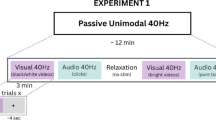

Seventeen papers of those retrieved outlined downstream cognitive and biological effects of auditory gamma stimulation102,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122. Eight of these were single-stimulation session studies examining cognitive effects in healthy individuals, reporting mixed findings on cognitive outcomes107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114. Forty-hertz binaural beat (BB) stimulation improved RT without increasing errors on an attention task109, enhanced both accuracy and RT on visuospatial and verbal working memory tasks107, and reduced false responses on the flanker task (even when there was no evidence of entrainment as indexed by absolute power)113. Further, 60-Hz BB stimulation reduced intrusion errors on word recall and digit span tasks112. Conversely, some studies found no effects on cognitive performance including word recall accuracy, digit span accuracy, RT108, auditory comprehension accuracy110, visual threshold, and visual spatial memory task accuracy111, or the error rate and RT of an attention network task114.

Nine studies retrieved employed chronic entrainment (one-hour daily sessions over several weeks or months), demonstrating some improvements across cognitive and biological outcomes102,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122. These included maintenance or enhancement of functional abilities and cognitive scores (assessed by ADCS-ADL, MMSE, face-name association task, MoCA, BoCA)102,115,116,119, reductions in brain atrophy and white matter loss observed using MRI102,115,118,120, enhanced functional connectivity measured by fMRI102,117, and improved sleep quality and daily rhythmicity102,116. In cognitively healthy participants with either sleep problems or a diagnosis of insomnia, interventions were associated with improved sleep quality and increased functional connectivity (fMRI), particularly within the hippocampus and default-mode network121,122.

The outcomes of chronic gamma stimulation appeared to vary across disease stages of AD. For individuals with MCI, a reduction in overall and regional white matter atrophy, decreased myelin content loss, particularly in the entorhinal region, and slower rates of atrophy in the corpus callosum were observed with daily gamma stimulation sessions over a six-month period118,120. Further, increased functional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus was reported in patients with MCI, when daily stimulation was applied for only eight weeks117. Improved performance on a face-name association task, reduced brain atrophy and loss of functional connectivity were observed in mild AD when stimulation was applied daily for three-months102. One study reported stability in outcomes with no significant improvements or declines in cognitive or biological measures in MCI or mild AD following daily stimulation for six months119. While fewer significant results were observed for moderate AD, some studies found a reduced rate of decline in cognitive measures and functional abilities, and reduced night-time activity following daily stimulation for six months115,116. No studies observed a significant difference in Aβ levels (measured by amyloid-PET and cerebrospinal fluid).

Mild adverse events (AE) were commonly reported across studies115,116,117,121,122, including headache, dizziness, and tinnitus. One moderate (chest irritation) and one severe (dementia exacerbation) AE were also reported116.

Nine studies of those retrieved used a range of stimulation frequencies to determine the optimal frequency for inducing entrainment in the given sample, according to different attributes of the brain response123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131. The stimulation frequency producing maximal gamma entrainment varied considerably between studies of adults alone, from 37 Hz124 to 48 Hz128 measured by PLI and EFR respectively. In children, one study indicated that the optimal entrainment frequency is around 36 Hz measured by EFR130. Among younger adults (19-35 years), optimal entrainment frequencies as determined by different measures were 37 Hz (PLI)124, 38 Hz (EFR, RMS amplitude)131, 40 Hz (amplitude)127, 40 Hz (AMFR, SNR)129, 40 Hz (ITC, ERSP)126, 41.5 Hz (PLI, ERSP)123, 45 Hz (ITC, energy)125, and 48 Hz (amplitude)128. In adults up to age 45, one study indicated that the strongest response was observed with stimulation at 46 Hz (EFR, RMS amplitude)131. No studies investigated optimal entrainment frequency in adults older than 45.

This search retrieved 14 clinical trial registry entries from ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP, 10 of which are ongoing (See Supplementary Materials S3, Supplementary Data 6). Where results of a clinical trial have been published, the corresponding reference has been included in the final column of Supplementary Data 6.

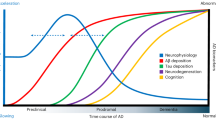

To synthesise the findings, we developed a schematic model (Fig. 2) illustrating the key factors identified in the review as influencing auditory gamma entrainment.

Individual differences (blue) (biological, cognitive, and lifestyle traits) and clinical factors (pink) (conditions involving cognitive decline and disease stage) both directly affect entrainment outcomes (orange). Individual differences may also influence the severity of clinical outcomes, which in turn further shape entrainment responses. Moreover, some individual and clinical factors may shift the gamma frequency at which entrainment is most effective, highlighting the potential need for personalised stimulation approaches (green). Together, these domains underscore the multifactorial nature of variability in auditory gamma entrainment.

Discussion

This systematic review examined responses to and effects of auditory (and audiovisual) gamma stimulation across healthy and clinical populations, identifying 16 distinct characteristics that appear to influence entrainment across studies. We aimed to elucidate how individual differences and clinical conditions may affect gamma entrainment and its associated cognitive and biological outcomes. Our findings suggest several promising patterns in the data, though the field would benefit from improved methodological standardisation to strengthen future research, particularly with respect to entrainment measurement in clinical populations. Below, we summarise the main findings and implications of the review.

A principal challenge encountered in this review is the considerable heterogeneity in methods used to measure entrainment, notably with techniques developing over time, reflecting a fragmented understanding of ‘effective’ entrainment. Our analysis revealed 32 different terms used to quantify entrainment, many of which overlap in methodological terms (see Table 5). These metrics fall into several broad categories: phase consistency, amplitude, power, coupling, coherence, and event-related responses.

The divergence in methodological approaches poses a significant barrier to cross-study comparisons, as the chosen quantification method may influence the interpretation of neural entrainment outcomes. As a result of this methodological heterogeneity, it becomes challenging to determine whether observed differences represent genuine variations in neural synchronisation or artefacts of the measurement technique employed. This underscores the need to work toward a consensus on entrainment metrics in future research.

The lack of consensus in entrainment metrics extends beyond academic discourse; it also has significant implications for the clinical translation of sensory gamma stimulation interventions. In several studies targeting populations with MCI and AD, elevated gamma power and amplitude were reported101,103,105. However, the mere presence of power in a given frequency band does not necessarily imply the presence of an oscillation at that frequency, as evoked potentials or muscle and eye-movement artefacts, for example, will yield power in multiple frequency bands even in the absence of oscillations132. Importantly, no study investigating entrainment outcomes in clinical cohorts in this review looked at metrics of phase. As such, studies evaluating entrainment efficacy in clinical cohorts relying solely on power and amplitude metrics may potentially overlook critical aspects of oscillatory dynamics that may be essential for accurately capturing entrainment. For instance, a study using phase-locking indices might detect significant entrainment where another using power-based measures might not, even when analysing the same underlying neural data.

This issue becomes especially pertinent in clinical applications. Reliance on a single entrainment measure, such as amplitude or power, risks excluding patients who may demonstrate entrainment via alternative indices, such as phase synchronisation. Indeed, while some studies have excluded ‘non-entrained’ participants based solely on a 40-Hz-specific amplitude criterion100, others have documented cognitive benefits even in the absence of significant power increases113, indicating that entrainment might not be fully captured by power metrics alone. If participants are to be excluded on the basis of ‘entrainability’, it is essential that the operational definition and measurement of entrainment are rigorously validated. These discrepancies highlight the importance of moving toward a unified, consensus-based approach to measuring entrainment – one that more comprehensively captures its dynamics in clinical populations and enhances translational insights into neurocognitive function. This is especially important considering the growing number of clinical trials employing gamma stimulation in clinical populations, as evidenced by this review (S3).

Nonetheless, important individual differences in auditory gamma entrainment were found. Of the 16 differences identified by our search as influencing the entrainment response, eight were biological in nature, including myelin content, cortical thickness, the excitation/inhibition balance, baseline theta power, sex, menstrual phase, handedness, and age. Cognitive performance measures - indexing processing speed, attention, and emotional arousal - as well as lifestyle factors such as cannabis use and musical training, appear to further modulate entrainment. In addition, neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD, ASD, and dyslexia have been associated with altered patterns of auditory gamma entrainment.

Although no single trait consistently predicted individual differences in auditory gamma entrainment, age emerged as one of the most frequently examined characteristics, which is particularly relevant for interventions in cognitive decline. However, the wide range of entrainment metrics used across studies made it difficult to compare studies directly. Some studies reported increased oscillatory power with age; for example, one study observed a linear increase from childhood through middle adulthood86. Given evidence of age-related changes in GABAergic function133,134, which is responsible for the generation and modulation of gamma oscillations135,136, increased gamma power observed with advancing age may reflect changes in inhibitory neural circuits137. However, the concurrent decline in PLI found in 20- to 58-year-olds71 could indicate reduced precision in neural synchrony. It could be that while the overall signal intensity may be preserved or even elevated, the fine-tuning of neural timing may become less effective with age. Notably, older adults were underrepresented in the studies reviewed. Nonetheless, these patterns underscore the need to distinguish between entrainment metrics; while higher power is often interpreted as indicative of stronger entrainment, in ageing populations, it may instead reflect compensatory activity or normal age-related shifts in cerebral network function138.

Understanding these inter-individual differences is likely to be important for optimising auditory gamma stimulation as a therapeutic tool. If future research can clarify their influence on the neural response, it may become feasible to adapt stimulation protocols to individual profiles, thereby maximising therapeutic outcomes. However, until the field reaches consensus on how entrainment is measured, drawing firm conclusions about the role of these individual differences will remain challenging.

Importantly, although 40 Hz remains the most commonly used frequency for auditory gamma stimulation, evidence from this review suggests that the optimal frequency for entrainment may vary between individuals. Several studies report stronger entrainment responses at frequencies ranging from 37 to 48 Hz123,124,125,128,131 across different age groups. Age-related variation appears particularly relevant, with some findings indicating that older adults respond more effectively to lower gamma frequencies139, an effect that may be especially important in dementia. In support of this, reduced GABA levels in ageing have been linked to lower peak gamma frequencies for entrainment140. It has also been proposed that the optimal entrainment frequency for humans may differ from that in animal models26. These findings raise questions about the widespread reliance on 40 Hz and suggest that fixed-frequency stimulation protocols may not fully capture individual variability in neural dynamics, which could influence efficacy.

Compounding this issue is the diversity of metrics used to determine optimal entrainment frequency. Consequently, the optimal frequency for entrainment identified using one measure may not correspond to that determined by another, leading to inconsistencies across studies. Moreover, while preliminary evidence from recent studies suggests a possible relationship between real-time 40-Hz EEG activity and subsequent cognitive improvements69, it remains unclear whether stimulating at a theoretically ‘optimal’ entrainment frequency would in fact confer greater therapeutic benefits. Establishing a potential link between entrainment strength and clinical outcomes, therefore, represents a key objective for future investigations.

The review further highlights a complex relationship between entrainment and the neurobiological substrates of cognitive function – a relationship which remains underexplored. In clinical populations, namely MCI or AD, increased gamma power and amplitude have been associated with cognitive decline101,103,105. Such increases may reflect compensatory mechanisms or a state of neuronal hyperexcitability in AD141,142,143. It is possible that measures of phase synchronisation could offer a particularly sensitive index of entrainment and may prove more sensitive to disease progression, thereby providing additional mechanistic insight. In this review, a positive correlation was observed between cortical thickness and PLV and ITPC in healthy participants75. Accordingly, these phase-based measures may be expected to decline with the brain atrophy characteristic of AD, in which cortical thickness is reduced144. However, none of the reviewed studies incorporated phase measures in clinical cohorts. Beyond cognitive function, our review also found little investigation of disease-specific factors that might shape the response to stimulation, despite indications that therapeutic benefits may depend on the stage of neurodegeneration145. Neural circuits may exhibit progressively attenuated responses to external stimulation with increasing disease severity, in a manner less readily captured by power measures, suggesting a need to characterise responsiveness across the course of neurodegeneration, to identify stages of diminishing neuroprotective effects.

In extension of this concern, where dementia patients are excluded for not meeting amplitude-based criteria for entrainment100, there is typically little consideration given to possible explanations for non-entrainment. This selective exclusion ensures the attributes or processes underlying subthreshold or absent entrainment, as determined by a singular metric, will remain understudied. Given the growing number of clinical trials in cognitive decline and auditory gamma stimulation, some of which require EEG evidence of entrainment for inclusion, it is increasingly important to develop a better understanding of the neurophysiological determinants of entrainment to expand its clinical utility.

Nevertheless, emerging evidence from cognitive and biological outcomes suggests that sensory gamma entrainment may have the potential to influence aspects of cognitive decline, with reported improvements in daily functioning, sleep quality, brain atrophy, connectivity, and cognitive performance. However, these benefits are not uniformly reported, and no study has yet demonstrated a significant change in amyloid levels – a finding that contrasts with preclinical rodent work. This discrepancy may reflect species-specific neurobiology or differences in stimulation parameters, such as duration. Chronic stimulation appears more effective than single-session exposure, and the reviewed studies indicate that longer-term stimulation may be necessary for robust cognitive and biological effects. Collectively, these findings point to the therapeutic promise of auditory gamma stimulation while exposing the current methodological narrowness: a broader range of strategies for both inducing gamma entrainment and quantifying its neurophysiological impact must be explored to realise its full potential.

It is also important to note that most long-term clinical studies in this review reported mild AE such as headaches, dizziness, and tinnitus115,116,117,122. Future research should prioritise the development of less obtrusive sensory gamma stimulation methods, particularly for vulnerable populations who require prolonged treatment, such as individuals with AD, for whom exposure to intense visual and auditory stimuli potentially limits feasibility and long-term adherence to stimulation-based interventions.

While this systematic review provides an overarching view of existing research on auditory gamma entrainment, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, there were minor discrepancies between the registered PROSPERO protocol and the final review. Specifically, the search strategy was expanded to include manual and AI-assisted searches, the inclusion criteria were broadened to encompass grey literature and neurodevelopmental conditions, and risk of bias assessment tools were adapted post hoc. These modifications were made to enhance completeness and methodological rigour, but they represent deviations from the original protocol and should be considered when interpreting the review. Second, the use of AI-assisted tools to support the literature search and broaden coverage remains an emerging approach that has not yet been standardised, which may limit reproducibility and hinder exact replication by other researchers. Third, the search was restricted to English and French publications, which may have introduced a degree of selection bias by excluding potentially relevant studies published in other languages. Beyond these methodological issues, the included studies varied considerably in design, sample size, stimulation protocols, outcome measures, and definitions of effective entrainment, which made synthesis challenging. The broad range of entrainment measures further complicates comparability, as does the difficulty of separating associations from experimental conditions, especially where multiple traits were studied simultaneously. Some ambiguity also emerged in distinguishing between stable traits and more context-dependent influences – such as attention – within the variables reviewed. For consistency, we included only those factors generalisable to intrinsic individual differences, although the contribution of external influences, such as stimulation parameters or contextual factors, remains important for future investigation.

We suggest that future research would benefit from prioritising the use of PLI as the primary metric for assessing auditory gamma entrainment. Phase-based measures are arguably the most direct measure of entrainment, defined as alignment of oscillations to an external rhythm20. PLI offers several advantages in comparison to other measures: it directly quantifies the temporal alignment of neural responses to external stimuli, is less susceptible to confounding from amplitude fluctuations, and may be more robust to noise80,146,147,148. Phase-based measures may also demonstrate greater reliability than power-based metrics149. Other indices, such as power or coherence, may provide complementary information on signal magnitude and network-level interactions, or even be more appropriate for certain research questions. Nonetheless, because phase synchronisation most directly captures the temporal alignment of neural responses, we propose that it serves as the principal, albeit not exclusive, metric for assessing entrainment.

Adopting a unified metric of entrainment would not only facilitate more rigorous cross-study comparisons but also enhance the translational potential of auditory gamma stimulation and entrainment interventions more broadly. With a consistent approach to measurement, it would become feasible to conduct meta-analyses capable of identifying robust predictors of therapeutic response and informing the development of tailored intervention strategies. Establishing such a consensus will be essential if auditory gamma stimulation is to progress from a promising experimental approach to a potentially clinically reliable intervention.

Several critical gaps in the literature warrant further investigation. First, there is a pressing need to determine whether a causal relationship exists between the degree of entrainment and the cognitive and biological outcomes reported in both healthy and cognitively impaired populations. Second, the field must address if the efficacy of auditory gamma stimulation declines as neurodegenerative disease progresses. Clarifying the pattern of stage-dependent efficacy will be essential for informing early intervention strategies and identifying patient populations most likely to benefit from gamma stimulation therapies. Third, systematic exploration of individualised stimulation protocols - including frequency tuning - is warranted. As evidence accumulates that optimal entrainment parameters may vary between individuals, future studies should evaluate the comparative benefits of personalised versus standard stimulation approaches. Demonstrating the feasibility and efficacy of tailored protocols would represent a significant advancement in the clinical application of auditory gamma stimulation.

Finally, there is a need to investigate the long-term effects of chronic auditory gamma stimulation. Extended treatment durations may be required to elicit demonstrable cognitive and neurobiological benefits observed in preclinical models, which have not yet been replicated in human studies. However, long-term studies must also carefully consider the comfort and safety of sustained stimulation, particularly for vulnerable populations. Future research should support the development of more tolerable stimulation methods to improve feasibility and adherence.

In summary, this systematic review has highlighted both the promise of and challenges endemic to the field of auditory gamma stimulation. The evidence indicates that individual differences, spanning biological, cognitive, lifestyle, and neurodevelopmental factors, play a role in shaping neural responses to auditory stimulation. Moreover, while preliminary findings suggest that auditory gamma stimulation may confer cognitive and biological benefits in neurological conditions with associated cognitive decline, the heterogeneity in measurement techniques and stimulation protocols complicates the interpretation of these findings.

To advance the field, we recommend the following:

-

1.

Consensus on entrainment metrics: Prioritise the use of PLI as the core metric of auditory gamma entrainment, supplemented by complementary measures, such as power or coherence.

-

2.

Causal investigations: Design experimental studies that manipulate entrainment parameters to determine whether the degree of neural synchronisation causally influences the observed cognitive/biological outcomes.

-

3.

Personalised protocols: Evaluate the benefits of individualised stimulation frequencies and tailored intervention strategies in comparison to standardised protocols.

-

4.

Early intervention focus: Identify patterns of disease progression associated with attenuated responsiveness to auditory gamma stimulation, thereby informing patient selection and optimal timing of intervention.

-

5.

Long-term studies: Conduct longitudinal research to evaluate the effects of chronic stimulation on both efficacy and tolerability, particularly in vulnerable populations.

By addressing these priorities, future research can overcome the limitations imposed by methodological heterogeneity and advance the clinical translation of sensory gamma stimulation into a highly impactful intervention for cognitive decline. In doing so, the field will not only deepen our understanding of neural synchronisation mechanisms but also contribute to the development of personalised, evidence-based treatment strategies for neurological disorders.

Methods

The systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines150 and the study’s pre-registered protocol on PROSPERO: CRD42024590002.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted on 1/10/2024 (updated on 26/11/2024) using the following electronic databases on the Ovid platform: MEDLINE, Embase, and APA PsycInfo. Additional searches were performed on ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organisation International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) to reduce evidence selection bias151. Databases were searched from their inception up until November 2024. An example of the terms and combinations applied to search within titles, abstracts, and/or keywords in the relevant databases is as follows: (gamma or “high-frequency” or “high frequency” or “40 Hz” or 40 Hz or “40-Hz” or “gamma-band” or “gamma band”). The full list of search terms and combinations for each database is provided in Supplementary Materials (S1). The search was restricted to studies conducted with human subjects and available in English or French.

Eligibility criteria

The review focused on studies utilising gamma-frequency auditory stimulation for the entrainment of gamma oscillations, whether applied independently or in conjunction with visual stimulation. Studies were included if they involved healthy individuals or individuals diagnosed with neurological conditions associated with cognitive decline, such as AD or MCI. Eligible studies were required to report EEG measures of entrainment, cognitive outcomes, or biological changes. Additionally, animal studies were excluded to align the review’s scope with the focus on human populations and translational applicability. Grey literature (non-peer-reviewed sources), including clinical trial registry entries and journal articles in preprint, were included in the records maintained, so as to minimise publication bias and provide an overview of ongoing research in the rapidly growing field152.

Data selection

In accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines150,153, two authors (EB and ADB) independently screened all titles and abstracts retrieved from the database search. The selected papers were cross-checked to confirm agreement, with any discrepancies resolved by a third author (GM). Full texts of the remaining articles were assessed against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine their eligibility for review. A manual reference list search of 10 highly relevant papers was then conducted, and artificial intelligence (AI) tools were employed to identify studies that may have been missed by the initial search (See S2 for the detailed list).

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted by authors EB and ADB from studies meeting the inclusion criteria and deemed eligible for review. The following information was retrieved: author(s), publication date, country, study design, population, sample size, percentage female, mean age, trait (or clinical condition(s) for clinical studies), stimulation modality, stimulation frequency, experimental paradigm (conditions and/or task), comparison group, outcome measures (measures of entrainment or cognitive/biological effects including neurobiological and physiological responses), and main findings of relevance. Data extraction was recorded using Microsoft Excel (Version 16.66.1).

Risk of bias

Two authors (EB and ADB) independently evaluated the risk of bias and quality for each study. For observational studies, the appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS)154 (Supplementary Data 7) was employed, while the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2)155 (Supplementary Data 8) or Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies - of Intervention (ROBINS-I)156 (Supplementary Data 9) tools were used for randomised controlled trials (RCT) or non-randomised trials of interventions respectively. Discrepancies in quality assessments were resolved through consensus discussion between the authors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

WHO. Dementia. World Health Organisation https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (2025).

Garre-Olmo, J. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Rev. Neurol. 66, 377–386 (2018).

Mably, A. J. & Colgin, L. L. Gamma oscillations in cognitive disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 52, 182–187 (2018).

van den Berg, M., Toen, D., Verhoye, M. & Keliris, G. A. Alterations in theta-gamma coupling and sharp wave-ripple, signs of prodromal hippocampal network impairment in the TgF344-AD rat model. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1081058 (2023).

Buzsáki, G. & Schomburg, E. W. What does gamma coherence tell us about inter-regional neural communication?. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 484–489 (2015).

Bosman, C. A., Lansink, C. S. & Pennartz, C. M. A. Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1982–1999 (2014).

Uhlhaas, P. J., Roux, F., Rodriguez, E., Rotarska-Jagiela, A. & Singer, W. Neural synchrony and the development of cortical networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 72–80 (2010).

Marzetti, L. et al. Brain functional connectivity through phase coupling of neuronal oscillations: a perspective from Magnetoencephalography. Front. Neurosci. 13, 964 (2019).

Berger, H. Ü ber das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. Arch. F.ür. Psychiatr. Nervenkrankh. 87, 527–570 (1929).

Cohen, D. Magnetoencephalography: Detection of the Brain’s Electrical Activity with a Superconducting Magnetometer. Science 175, 664–666 (1972).

Müller, M. M., Gruber, T. & Keil, A. Modulation of induced gamma band activity in the human EEG by attention and visual information processing. Int. J. Psychophysiol. J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 38, 283–299 (2000).

Lisman, J. Working memory: the importance of theta and gamma oscillations. Curr. Biol. CB 20, R490–R492 (2010).

Chuderski, A. & Andrelczyk, K. From neural oscillations to reasoning ability: Simulating the effect of the theta-to-gamma cycle length ratio on individual scores in a figural analogy test. Cogn. Psychol. 76, 78–102 (2015).

Tarullo, A. R. et al. Gamma power in rural Pakistani children: Links to executive function and verbal ability. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 26, 1–8 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Gamma oscillations in schizophrenia: Mechanisms and clinical significance. Brain Re.s 1413, 98–114 (2011).

Traikapi, A. & Konstantinou, N. Gamma oscillations in Alzheimer’s disease and their potential therapeutic role. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 782399 (2021).

van Diessen, E., Senders, J., Jansen, F. E., Boersma, M. & Bruining, H. Increased power of resting-state gamma oscillations in autism spectrum disorder detected by routine electroencephalography. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 265, 537–540 (2015).

Hughes, J. R. Gamma, fast, and ultrafast waves of the brain: their relationships with epilepsy and behavior. Epilepsy Behav. EB 13, 25–31 (2008).

Dor-Ziderman, Y. et al. High-gamma oscillations as neurocorrelates of ADHD: A MEG crossover placebo-controlled study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 137, 186–193 (2021).

Lakatos, P., Gross, J. & Thut, G. A new unifying account of the roles of neuronal entrainment. Curr. Biol. 29, R890–R905 (2019).

Başar, E. A review of gamma oscillations in healthy subjects and in cognitive impairment. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 90, 99–117 (2013).

Guan, A. et al. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: Mechanism and treatment. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 962957 (2022).

Schmid, D. G. Prospects of cognitive-motor entrainment: an interdisciplinary review. Front. Cogn. 3 (2024).

Maiella, M. et al. Simultaneous transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation boost gamma oscillations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 12, 19391 (2022).

Moisa, M., Polania, R., Grueschow, M. & Ruff, C. C. Brain Network Mechanisms Underlying Motor Enhancement by Transcranial Entrainment of Gamma Oscillations. J. Neurosci. 36, 12053–12065 (2016).

Lee, K. et al. Optimal flickering light stimulation for entraining gamma waves in the human brain. Sci. Rep. 11, 16206 (2021).

Gautam, D. et al. Click-train evoked steady state harmonic response as a novel pharmacodynamic biomarker of cortical oscillatory synchrony. Neuropharmacology 240, 109707 (2023).

Bjekić, J. et al. The subjective experience of transcranial electrical stimulation: a within-subject comparison of tolerability and side effects between tDCS, tACS, and otDCS. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 18, 1468538 (2024).

Black, R. D. & Rogers, L. L. Sensory neuromodulation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 14 (2020).

Nowak, M. et al. Driving Human Motor Cortical Oscillations Leads to Behaviorally Relevant Changes in Local GABAA Inhibition: A tACS-TMS Study. J. Neurosci. J. Soc. Neurosci. 37, 4481–4492 (2017).

Laczó, B., Antal, A., Niebergall, R., Treue, S. & Paulus, W. Transcranial alternating stimulation in a high gamma frequency range applied over V1 improves contrast perception but does not modulate spatial attention. Brain Stimul. 5, 484–491 (2012).

Hopfinger, J. B., Parsons, J. & Fröhlich, F. Differential effects of 10-Hz and 40-Hz transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) on endogenous versus exogenous attention. Cogn. Neurosci. 8, 102–111 (2017).

Javadi, A.-H., Glen, J. C., Halkiopoulos, S., Schulz, M. & Spiers, H. J. Oscillatory Reinstatement Enhances Declarative Memory. J. Neurosci. J. Soc. Neurosci. 37, 9939–9944 (2017).

Hoy, K. E. et al. The effect of γ-tACS on working memory performance in healthy controls. Brain Cogn. 101, 51–56 (2015).

Iaccarino, H. F. et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature 540, 230–235 (2016).

Bai, W., Xia, M., Liu, T. & Tian, X. Aβ1-42-induced dysfunction in synchronized gamma oscillation during working memory. Behav. Brain Res. 307, 112–119 (2016).

Verret, L. et al. Inhibitory Interneuron Deficit Links Altered Network Activity and Cognitive Dysfunction in Alzheimer Model. Cell 149, 708–721 (2012).

Solé-Domènech, S., Cruz, D. L., Capetillo-Zarate, E. & Maxfield, F. R. The endocytic pathway in microglia during health, aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 32, 89–103 (2016).

Bamberger, M. E. & Landreth, G. E. Microglial interaction with β-amyloid: Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Microsc. Res. Tech. 54, 59–70 (2001).

Hu, J. et al. Sensory gamma entrainment: Impact on amyloid protein and therapeutic mechanism. Brain Res. Bull. 202, 110750 (2023).

Shen, Q. et al. Gamma frequency light flicker regulates amyloid precursor protein trafficking for reducing β-amyloid load in Alzheimer’s disease model. Aging Cell 21, e13573 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Gamma-patterned sensory stimulation reverses synaptic plasticity deficits in rat models of early Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 58, 3402–3411 (2023).

Adaikkan, C. et al. Gamma entrainment binds higher-order brain regions and offers neuroprotection. Neuron 102, 929–943.e8 (2019).

Blanco-Duque, C., Chan, D., Kahn, M. C., Murdock, M. H. & Tsai, L.-H. Audiovisual gamma stimulation for the treatment of neurodegeneration. J. Intern. Med. 295, 146–170 (2024).

Lobo, T., Brookes, M. J. & Bauer, M. Can the causal role of brain oscillations be studied through rhythmic brain stimulation?. J. Vis. 21, 2 (2021).

Krause, B. & Cohen Kadosh, R. Not all brains are created equal: the relevance of individual differences in responsiveness to transcranial electrical stimulation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8, 25 (2014).

Katz, B. et al. Individual differences and long-term consequences of tDCS-augmented cognitive training. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 1498–1508 (2017).

Zanto, T. P. et al. Individual differences in neuroanatomy and neurophysiology predict effects of transcranial alternating current stimulation. Brain Stimul. 14, 1317–1329 (2021).

Bañuelos, C. et al. Prefrontal Cortical GABAergic dysfunction contributes to age-related working memory impairment. J. Neurosci. 34, 3457–3466 (2014).

Luebke, J. I., Chang, Y.-M., Moore, T. L. & Rosene, D. L. Normal aging results in decreased synaptic excitation and increased synaptic inhibition of layer 2/3 pyramidal cells in the monkey prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 125, 277–288 (2004).

Murty, D. V. P. S. et al. Gamma oscillations weaken with age in healthy elderly in human EEG. NeuroImage 215, 116826 (2020).

Alawi, M., Lee, P. F., Deng, Z.-D., Goh, Y. K. & Croarkin, P. E. Modelling the differential effects of age on transcranial magnetic stimulation induced electric fields. J. Neural Eng. 20, 026016 (2023).

Guerra, A. et al. The effect of gamma oscillations in boosting primary motor cortex plasticity is greater in young than older adults. Clin. Neurophysiol. 132, 1358–1366 (2021).

van Pelt, S., Shumskaya, E. & Fries, P. Cortical volume and sex influence visual gamma. NeuroImage 178, 702–712 (2018).

Rudroff, T., Workman, C. D., Fietsam, A. C. & Kamholz, J. Response Variability in Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Why Sex Matters. Front. Psychiatry 11, 585 (2020).

Hädel, S., Wirth, C., Rapp, M., Gallinat, J. & Schubert, F. Effects of age and sex on the concentrations of glutamate and glutamine in the human brain. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 38, 1480–1487 (2013).

Williams, L. M. et al. Neural synchrony and gray matter variation in human males and females: an integration of 40 Hz gamma synchrony and MRI measures. J. Integr. Neurosci. 04, 77–93 (2005).

Güntekin, B. & Başar, E. Brain oscillations are highly influenced by gender differences. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 65, 294–299 (2007).

Herrmann, C. S. & Demiralp, T. Human EEG gamma oscillations in neuropsychiatric disorders. Clin. Neurophysiol. 116, 2719–2733 (2005).

Stam, C. J. et al. Generalized Synchronization of MEG Recordings in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence for Involvement of the Gamma Band. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 19, 562 (2002).

Koenig, T. et al. Decreased EEG synchronization in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 165–171 (2005).

Jones, K. T., Ostrand, A. E., Gazzaley, A. & Zanto, T. P. Enhancing cognitive control in amnestic mild cognitive impairment via at-home non-invasive neuromodulation in a randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 13, 7435 (2023).

Jones, K. T. et al. Gamma neuromodulation improves episodic memory and its associated network in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Neurobiol. Aging 129, 72–88 (2023).

Shu, I.-W., Lin, Y., Granholm, E. L. & Singh, F. A Focused Review of Gamma Neuromodulation as a Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s Spectrum Disorders. J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 9, e240001 (2024).

Anderkova, L., Eliasova, I., Marecek, R., Janousova, E. & Rektorova, I. Distinct Pattern of gray matter atrophy in mild Alzheimer’s disease impacts on cognitive outcomes of noninvasive brain stimulation. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 48, 251–260 (2015).

Cedres, N. et al. The interplay between gray matter and white matter neurodegeneration in subjective cognitive decline. Aging 13, 19963–19977 (2021).

Park, Y. et al. White matter microstructural integrity as a key to effective propagation of gamma entrainment in humans. GeroScience https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01281-2 (2024).

Schoisswohl, S. et al. Heading for personalized rTMS in Tinnitus: reliability of individualized stimulation protocols in behavioral and electrophysiological responses. J. Pers. Med. 11, 536 (2021).

Sahu, P. P., Lo, Y.-H. & Tseng, P. 40 Hz sensory entrainment: Is real-time EEG a good indicator of future cognitive improvement?. Neurol. Sci. 45, 1271–1274 (2024).

Martorell, A. J. et al. Multi-sensory Gamma Stimulation Ameliorates Alzheimer’s-associated pathology and improves cognition. Cell 177, 256–271.e22 (2019).

Griškova-Bulanova, I., Dapsys, K. & Valentinas, M. Does brain ability to synchronize with 40 Hz auditory stimulation change with age?. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 73, 564–570 (2013).

Melynyte, S. et al. 40 Hz auditory steady-state response: the impact of handedness and gender. Brain Topogr. 31, 419–429 (2018).

Griškova-Bulanova, I., Griksiene, R., Korostenskaja, M. & Ruksenas, O. 40 Hz auditory steady-state response in females: When is it better to entrain?. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 74, 91–97 (2014).

Griškova-Bulanova, I. et al. Responses at individual gamma frequencies are related to the processing speed but not the inhibitory control. J. Pers. Med. 13, 26 (2023).

Schuler, A.-L. et al. Auditory driven gamma synchrony is associated with cortical thickness in widespread cortical areas. NeuroImage 255, 119175 (2022).

Larsen, K. M., Thapaliya, K., Barth, M., Siebner, H. R. & Garrido, M. I. Phase locking of auditory steady state responses is modulated by a predictive sensory context and linked to degree of myelination in the cerebellum. 2023.06.08.23291140 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.08.23291140 (2023).

Zhang, L., Peng, W., Chen, J. & Hu, L. Electrophysiological evidences demonstrating differences in brain functions between nonmusicians and musicians. Sci. Rep. 5, 13796 (2015).

Arutiunian, V., Arcara, G., Buyanova, I., Gomozova, M. & Dragoy, O. The age-related changes in 40 Hz Auditory Steady-State Response and sustained Event-Related Fields to the same amplitude-modulated tones in typically developing children: A magnetoencephalography study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 5370–5383 (2022).

De Stefano, L. A. et al. Developmental Effects on Auditory Neural Oscillatory Synchronization Abnormalities in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 13, 34 (2019).

Alegre, M. et al. Effect of reduced attention on auditory amplitude-modulation following responses: a study with chirp-evoked potentials. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 25, 42 (2008).

Skosnik, P. D. et al. The Effect of Chronic Cannabinoids on Broadband EEG Neural Oscillations in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 2184–2193 (2012).

Cho, R. Y. et al. Development of Sensory Gamma Oscillations and Cross-Frequency Coupling from Childhood to Early Adulthood. Cereb. Cortex 25, 1509–1518 (2015).

Johnson, B. W., Weinberg, H., Ribary, U., Cheyne, D. O. & Ancill, R. Topographic distribution of the 40 Hz auditory evoked-Related potential in normal and aged subjects. Brain Topogr. 1, 117–121 (1988).

Bosnyak, D. J., Eaton, R. A. & Roberts, L. E. Distributed Auditory Cortical Representations Are Modified When Non-musicians Are Trained at Pitch Discrimination with 40 Hz Amplitude Modulated Tones. Cereb. Cortex 14, 1088–1099 (2004).

Griškova-Bulanova, I., Pipinis, E., Voicikas, A. & Koenig, T. Global field synchronization of 40 Hz auditory steady-state response: Does it change with attentional demands?. Neurosci. Lett. 674, 127–131 (2018).

Rojas, D. C. et al. Development of the 40 Hz steady state auditory evoked magnetic field from ages 5 to 52. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117, 110–117 (2006).

Toso, A. et al. 40 Hz Steady-State Response in Human Auditory Cortex Is Shaped by Gabaergic Neuronal Inhibition. J. Neurosci. 44 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Emotional Arousal and Valence Jointly Modulate the Auditory Response: A 40-Hz ASSR Study. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 29, 1150–1157 (2021).

Horwitz, A. et al. Brain responses to passive sensory stimulation correlate with intelligence. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 201 (2019).

Herdman, A. T. Neuroimaging evidence for top-down maturation of selective auditory attention. Brain Topogr. 24, 271–278 (2011).

Lorenzini, I. et al. Neural processing of auditory temporal modulations in awake infants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 154, 1954–1962 (2023).

Roth, C. et al. The influence of visuospatial attention on unattended auditory 40 Hz responses. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 370 (2013).

Ross, B. & Fujioka, T. 40-Hz oscillations underlying perceptual binding in young and older adults. Psychophysiology 53, 974–990 (2016).

Horwitz, A. et al. Passive double-sensory evoked coherence correlates with long-term memory capacity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 598 (2017).

Lizarazu, M. et al. Neural entrainment to speech and nonspeech in dyslexia: Conceptual replication and extension of previous investigations. Cortex 137, 160–178 (2021).

Seymour, R. A., Rippon, G., Gooding-Williams, G., Sowman, P. F. & Kessler, K. Reduced auditory steady state responses in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 11, 56 (2020).

Granados Barbero, R., de Vos, A., Ghesquière, P. & Wouters, J. Atypical processing in neural source analysis of speech envelope modulations in adolescents with dyslexia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 54, 7839–7859 (2021).

Wilson, T. W., Wetzel, M. W., White, M. L. & Knott, N. L. Gamma-frequency neuronal activity is diminished in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a pharmaco-MEG study. J. Psychopharmacol. 26, 771–777 (2012).

Lahijanian, M., Aghajan, H. & Vahabi, Z. Auditory gamma-band entrainment enhances default mode network connectivity in dementia patients. Sci. Rep. 14, 13153 (2024).

Lahijanian, M., Aghajan, H., Vahabi, Z. & Afzal, A. Gamma Entrainment Improves Synchronization Deficits in Dementia Patients. 2021.09.30.462389 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.30.462389 (2021).

van Deursen, J. A., Vuurman, E. F. P. M., van Kranen-Mastenbroek, V. H. J. M., Verhey, F. R. J. & Riedel, W. J. 40-Hz steady state response in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 24–30 (2011).

Chan, D. et al. Gamma frequency sensory stimulation in mild probable Alzheimer’s dementia patients: Results of feasibility and pilot studies. PLOS ONE 17, e0278412 (2022).

Osipova, D., Pekkonen, E. & Ahveninen, J. Enhanced magnetic auditory steady-state response in early Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 117, 1990–1995 (2006).

Shao, H., Shao, H. & Wang, W. Neural mechanisms underlying brain gamma entrainment after periodic auditory stimulation at Gamma Frequency. Int. J. Pharma Med. Biol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijpmbs.13.1.14-18 (2024).

Shahmiri, E. et al. Effect of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease on auditory steady-state responses. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 8, 299–306 (2017).

Spydell, J. D., Pattee, G. & Goldie, W. D. The 40 hertz auditory event-related potential: Normal values and effects of lesions. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. Potentials Sect. 62, 193–202 (1985).

Wang, L., Zhang, W., Li, X. & Yang, S. The Effect of 40 Hz binaural beats on working memory. IEEE Access 10, 81556–81567 (2022).

Chaieb, L., Wilpert, E. C., Hoppe, C., Axmacher, N. & Fell, J. The impact of monaural beat stimulation on anxiety and cognition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 251 (2017).

Engelbregt, H., Meijburg, N., Schulten, M., Pogarell, O. & Deijen, J. B. The effects of binaural and monoaural beat stimulation on cognitive functioning in subjects with different levels of emotionality. Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 15, 199–207 (2019).

Kim, J., Kim, H.-W., Kovar, J. & Lee, Y. S. Neural consequences of binaural beat stimulation on auditory sentence comprehension: an EEG study. Cereb. Cortex 34, bhad459 (2024).

Hsiung, P.-C. & Hsieh, P.-J. Forty-Hertz audiovisual stimulation does not have a promoting effect on visual threshold and visual spatial memory. J. Vis. 24, 8 (2024).

Manippa, V., Filardi, M., Vilella, D., Logroscino, G. & Rivolta, D. Gamma (60 Hz) auditory stimulation improves intrusions but not recall and working memory in healthy adults. Behav. Brain Res. 456, 114703 (2024).

Engelbregt, H., Barmentlo, M., Keeser, D., Pogarell, O. & Deijen, J. B. Effects of binaural and monaural beat stimulation on attention and EEG. Exp. Brain Res. 239, 2781–2791 (2021).

Leistiko, N. M., Madanat, L., Yeung, W. K. A. & Stone, J. M. Effects of gamma frequency binaural beats on attention and anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 43, 5032–5039 (2024).

Hajós, M. et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy estimate of evoked gamma oscillation in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurol. 15, 1343588 (2024).

Cimenser, A. et al. Sensory-Evoked 40-Hz Gamma oscillation improves sleep and daily living activities in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 746859 (2021).

He, Q. et al. A feasibility trial of gamma sensory flicker for patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 7, e12178 (2021).

Da, X. et al. Noninvasive Gamma sensory stimulation may reduce white matter and Myelin Loss in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s. Dis. 97, 359–372 (2024).

McNett, S. D. et al. A Feasibility Study of AlzLife 40 Hz sensory therapy in patients with MCI and Early AD. Healthcare 11, 2040 (2023).

Da, X. et al. SpectrisTM treatment preserves corpus callosum structure in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurol. 15, 1452930 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. 40HZ photoacoustic interventions combined with blue light improve brain function and sleep quality in a healthy population. 2023.05.22.23290180 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.22.23290180 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Study on Gamma sensory flicker for Insomnia. Int. J. Neurosci. 135, 1023–1033 (2024).

Parciauskaite, V. et al. Individual Resonant Frequencies at Low-Gamma Range and Cognitive Processing Speed. J. Pers. Med. 11, 453 (2021).

Mockevičius, A. et al. Extraction of Individual EEG Gamma Frequencies from the Responses to Click-Based Chirp-Modulated Sounds. Sensors 23, 2826 (2023).

Artieda, J. et al. Potentials evoked by chirp-modulated tones: a new technique to evaluate oscillatory activity in the auditory pathway. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115, 699–709 (2004).

Tada, M. et al. Global and Parallel Cortical Processing Based on Auditory Gamma Oscillatory Responses in Humans. Cereb. Cortex 31, 4518–4532 (2021).

Pastor, M. A. et al. Activation of human cerebral and cerebellar cortex by auditory stimulation at 40 Hz. J. Neurosci. 22, 10501–10506 (2002).

Zaehle, T., Lenz, D., Ohl, F. W. & Herrmann, C. S. Resonance phenomena in the human auditory cortex: individual resonance frequencies of the cerebral cortex determine electrophysiological responses. Exp. Brain Res. 203, 629–635 (2010).

Aoyagi, M. et al. Optimal modulation frequency for amplitude-modulation following response in young children during sleep. Hear. Res. 65, 253–261 (1993).

Poulsen, C., Picton, T. W. & Paus, T. Age-related changes in transient and oscillatory brain responses to auditory stimulation during early adolescence. Dev. Sci. 12, 220–235 (2009).

Poulsen, C., Picton, T. W. & Paus, T. Age-Related Changes in Transient and Oscillatory Brain Responses to Auditory Stimulation in Healthy Adults 19–45 Years Old. Cereb. Cortex 17, 1454–1467 (2007).

Henao, D., Navarrete, M., Valderrama, M. & Le Van Quyen, M. Entrainment and synchronization of brain oscillations to auditory stimulations. Neurosci. Res. 156, 271–278 (2020).

Gao, F. et al. Edited magnetic resonance spectroscopy detects an age-related decline in brain GABA levels. NeuroImage 78, 75–82 (2013).

Zuppichini, M. D. et al. GABA levels decline with age: A longitudinal study. Imaging Neurosci. 2, 1–15 (2024).

Bartos, M., Vida, I. & Jonas, P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 45–56 (2007).

Brown, J. T., Davies, C. H. & Randall, A. D. Synaptic activation of GABAB receptors regulates neuronal network activity and entrainment. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 2982–2990 (2007).

Barr, M. S. et al. Age-related differences in working memory evoked gamma oscillations. Brain Res 1576, 43–51 (2014).

Bakhtiari, A. et al. Power and distribution of evoked gamma oscillations in brain aging and cognitive performance. GeroScience 45, 1523–1538 (2023).

Park, Y. et al. Optimal flickering light stimulation for entraining gamma rhythms in older adults. Sci. Rep. 12, 15550 (2022).

Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Edden, R. A. E., Jones, D. K., Swettenham, J. B. & Singh, K. D. Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 8356–8361 (2009).

Palop, J. J. & Mucke, L. Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 777–792 (2016).

Targa Dias Anastacio, H., Matosin, N. & Ooi, L. Neuronal hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s disease: what are the drivers behind this aberrant phenotype?. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 1–14 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Enhanced Gamma Activity and Cross-Frequency Interaction of Resting-State Electroencephalographic Oscillations in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 243 (2017).

Evans, M. C. et al. Volume changes in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: cognitive associations. Eur. Radiol. 20, 674–682 (2010).

Adaikkan, C. & Tsai, L.-H. Gamma Entrainment: Impact on Neurocircuits, Glia, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 43, 24–41 (2020).

Aydore, S., Pantazis, D. & Leahy, R. M. A note on the phase locking value and its properties. NeuroImage 74, 231–244 (2013).

Cohen, M. X., Wilmes, K. A. & van de Vijver, I. Cortical electrophysiological network dynamics of feedback learning. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 558–566 (2011).

Lowet, E., Roberts, M. J., Bonizzi, P., Karel, J. & Weerd, P. D. Quantifying Neural Oscillatory Synchronization: A Comparison between Spectral Coherence and Phase-Locking Value Approaches. PLOS ONE 11, e0146443 (2016).

McFadden, K. L. et al. Test-Retest Reliability of the 40 Hz EEG Auditory Steady-State Response. PLOS ONE 9, e85748 (2014).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. & PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6, e1000097 (2009).

Drucker, A. M., Fleming, P. & Chan, A.-W. Research Techniques Made Simple: Assessing Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews. J. Invest. Dermatol. 136, e109–e114 (2016).

Paez, A. Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. J. Evid. -Based Med. 10, 233–240 (2017).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021).

Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C. & Dean, R. S. Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open (2006).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343, d5928 (2011).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355, i4919, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919 (2016).

van Noordt, S., Desjardins, J. A., Team, T. B. & Elsabbagh, M. Inter-trial theta phase consistency during face processing in infants is associated with later emerging autism. Autism Res 15, 834–846 (2022).

Li, S., Hong, B., Gao, X., Wang, Y. & Gao, S. Event-related spectral perturbation induced by action-related sound. Neurosci. Lett. 491, 165–167 (2011).

Abdul-Latif, A. A., Cosic, I., Kumar, D. K., Polus, B. & Da Costa, C. Power changes of EEG signals associated with muscle fatigue: the root mean square analysis of EEG bands. in Proceedings of the 2004 Intelligent Sensors, Sensor Networks and Information Processing Conference, 2004. 531–534 https://doi.org/10.1109/ISSNIP.2004.1417517 (2004).

Cohen, L. Time-frequency distributions-a review. Proc. IEEE 77, 941–981 (1989).

Levi, E. C., Folsom, R. C. & Dobie, R. A. Amplitude-modulation following response (AMFR): Effects of modulation rate, carrier frequency, age, and state. Hear. Res. 68, 42–52 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This systematic review was funded by Shanda, Tianqiao, and Chrissy Chen Institute, the Medical Research Council (MRC: MR/N013182/1), and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR: NIHR304904). The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. conducted the full systematic review procedure and was responsible for the initial manuscript writing and further editing. ADB conducted the full systematic review procedure and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. SHW assisted with data extraction verification and consistency checks. A.K. contributed to manuscript editing and refinement. GM resolved discrepancies in screening and data extraction between E.B. and A.D.B. and was heavily involved in manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions