Abstract

At present, the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) is difficult, and there is an urgent need for better diagnostic methods. This study enrolled 136 patients from 2020 to 2021 and collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimens. We used metatranscriptome to analyze the lower respiratory tract microbiome (LRTM) and host immune response. The diversity of the LRTM in LRTIs significantly decreased, manifested by a decrease in the abundance of normal microbiota and an increase in the abundance of opportunistic pathogens. The upregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the LRTIs group were mainly enriched in infection immune response-related pathways. Klebsiella pneumoniae had the most significant increase in abundance in LRTIs, which was strongly correlated with host infection or inflammation genes TNFRSF1B, CSF3R, and IL6R. We combined LRTM and host transcriptome data to construct a machine-learning model with 12 screened features to discriminate LRTIs and non-LRTIs. The results showed that the model trained by Random Forest in the validate set had the best performance (ROC AUC: 0.937, 95% CI: 0.832–1). The independent external dataset showed an accuracy of 76.5% for this model. This study suggests that the model integrating LRTM and host transcriptome data can be an effective tool for LRTIs diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) are an infectious cause leading to more than 3 million deaths a year1,2. Traditional diagnosis of acute respiratory disease from the causative agent is not often available due to the limitations of current microbiological tests in terms of sensitivity, speed, and spectrum. In fact, conventional microbial methods identify a pathogen in only 30-40% of LRTIs cases3. Without reliable diagnosis, clinicians may decide to initiate unnecessary antibiotic treatment, possibly driving the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Another challenge for clinicians is the complex clinical cases. Critically ill patients in the intensive care unit can have simultaneously overlapping clinical features between infections and noninfectious inflammatory conditions4, and severely immunocompromised individuals may present with atypical infection characteristics due to immuno-hyporesponsiveness5.

The conventional model of pathogenesis for LRTIs reflects the assumption that the lungs are sterile. However, results of lung microbiome studies using culture-independent assessment of microbial genomes have shown the pathogenesis of LRTIs is an emergent phenomenon arising from the combination of high microbial biomass, low microbial diversity, and host inflammation that arises from pre-existing homeostasis of biodiversity6,7,8. Another exciting new frontier in infectious disease diagnostics is examining the host response to infection, which offers a diagnostic strategy complementary to pathogen-based diagnostics of acute respiratory infections versus those with noninfectious illnesses already in use9,10.

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) holds promise for overcoming those diagnostic challenges deriving from traditional assessment for identifying pathogens, as well as extending both transcriptional biomarker assays of the immune response and the analysis of the airway microbiome of patients with LRTIs by testing microliter volumes of clinical samples4,11,12. We here combine host transcriptional profiling with the respiratory microbiome using machine learning for better diagnostic accuracy of LRTIs, and then evaluate the performance of this diagnostic model.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This study sequentially enrolled subjects with suspected LRTIs who were admitted to Peking University People’s Hospital between May 2020 and January 2021. This study was approved by the research ethics board at Peking University People’s Hospital (approval no. 2019PHB134). The inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) at least compliance with the clinical definition of LRTIs referring to US Centers for Disease Control/National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) surveillance case definitions (Dataset S1) and identified by at least two-physician adjudication; (2) informed consent and voluntary participation in the study; and (3) having complete clinical data and underwent a flexible bronchoscopy with BALF collected. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) cases with absolute evidence for co-infection with other organs; (2) bronchoscopy couldn’t be performed; (3) pregnant or breastfeeding women; (4) subjects who were unable to cooperate, unwilling to participate, or whose clinical data were incomplete.

Demographic and baseline characteristics, clinical presentation, radiography, and laboratory findings of 136 recruited subjects were investigated for LRTIs diagnosis with the review of electronic medical records. Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were presented as numbers (%), and were analyzed using either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value less than 0.05.

Specimen preparation and mNGS

The BALF specimens from the 136 subjects were collected before antibiotic therapy after admission to the hospital. We mixed residual BALF with DNA/RNA Shield on ice and frozen at −80 °C. We established a mNGS and data analysis protocol including DNA/RNA extraction and purification, library construction, sequencing, and detection bioinformatics analysis. DNA and RNA were extracted from 300 μL of patient BALF mixture using MagMAX™ CORE Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sterile deionized water was extracted alongside the specimens as a negative control, and it was involved in subsequent library construction and sequencing. In order to obtain transcriptional RNA of microbes to show they were alive at the time of sampling, DNA was removed from RNA using DNase (RNase free; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the concentrations of purified RNA were then determined using the Qubit RNA HS (high sensitivity) Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The collected RNA was reverse transcribed to generate cDNA and used to prepare sequencing libraries using the Reverse Transcription Module for NGS Library Prep Kit (Matridx, Hangzhou, China). The final DNA-seq libraries were sequenced using Illumina’s NextSeq 550 System (150-bp paired-end reads). The sterile distilled water as a negative control sample ran through the full process, including specimen preparation and mNGS.

Bioinformatics pipeline

Reads were processed by Trimmomatic(version 0.36) software13 to remove adapters and trim low-quality bases. After trimming the bases with a quality of less than 20, the paired reads with at least 35 bp were considered high-quality sequencing data for further analysis. Firstly, these high-quality sequencing data were mapped on the human reference genome (GRCh38) to divide into host reads (mapped reads) and microbial reads (unmapped reads). Then, unmapped reads were aligned against the SILVA(version 138) database14 using Bowtie2(v2.3.4.3)15 to remove rRNA sequences.

Microbiome analysis

After filtering and rRNA removal, microbial reads were used to carry out species identification and abundance calculations by Kranken2. To decontaminate the data of each sample, the mean of the abundance of all negative control samples (sterile deionized water) was used as the baseline. The microorganisms with an abundance less than ten folds of negative controls’ mean were removed from further analysis. The α diversity of microbial flora was estimated using the vegan package in R. The analysis of differential microorganisms was performed using the edgeR package in R16. And 68 samples whose total read count was greater than 10,00,000 were selected for trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization and testing significance of difference. The Rtsne software17 package was used for t-SNE analysis. At the same time, TMM normalized abundance of microorganisms was used for subsequent correlation analysis and machine learning.

Host transcriptome analysis

The high-quality data were aligned to the human reference genome by STAR (v2.7.8a), and then estimated the read count of the host gene was using featureCounts(v2.0.1)18,19. We analyzed differential expression using DESeq220. First, the samples with a total read count greater than 10,00,000 were selected for normalizing, and then the genes with the absolute value of log2FC greater than 1 and a corrected P-value less than 0.05 were selected as the significantly differentially expressed genes. Mitochondrial genes were removed. The enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package21. Meanwhile, the read count of the gene was used to calculate the transcripts per million (TPM) value as the gene expression for subsequent correlation analysis and machine learning.

Correlation analysis between the microbiome and host transcriptome

We used the TMP expression of the host gene and the TMM normalized abundance of the microbial flora for correlation analysis. The genes and bacterial populations with significant differential expression were selected for correlation analysis and calculated with the Hmisc package in R. Finally, the absolute value of a correlation coefficient greater than 0.5 and a P-value less than 0.05 were selected as the genes and microbes with significant correlation. The microbes correlated with host genes were used to estimate gene expression. Microbial reads were mapped to selected microbes’ reference genomes by using Bowtie2(v2.3.4.3), and then the read count of the microbial genes was estimated using featureCounts(v2.0.1). The read count of microbial genes was normalized to TPM values for further analysis. Correlation analysis between microbial genes and significant differential host genes was performed with the Hmisc package in R. The Network of correlation between genes was visualized by CytoScape (v3.7.1).

Machine learning

For LRTIs samples and non-LRTIs samples, we trained machine learning models for diagnosis prediction. We selected significant differential expressed host genes and microorganisms with significant differential abundance as features for machine learning. The training of the machine learning model was mainly carried out with a caret package in R. First, we parted the data into training set and validate set randomly. Two-thirds of the samples were used as training set for model training, and the remaining one-third were used as validate set. Then, the random forest analysis was used to estimate the importance of features and select the feature set with the best prediction effect. Then the optimized features were used to train three typical machine learning models, including Random Forest, support vector machines (SVM), and artificial neural network (ANN). For the Random Forest model, the caret package was applied to the finetune model using the repeatedcv method, finetune grid set from 4 to 20, and ntree set to 1000. For the SVM model, finetune was also performed by caret package with repeatedcv method, finetune grid set sigma 0.005, 0.01, 0.015, 0.2 and set C 0.55, 0.7, 0.75, 0.9,1, SVM kernel used radial kernel. For the ANN model, mlp function of the RSNNS package was applied to finetune the model by setting learFunc = Std_Backpropagation, maxit = 1000, and learnFuncParams = c(0.1,2.0,0.0001,0.1). Finally, the performance of different models was evaluated, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) and the ROC curve were estimated and drawn using the pROC package22.

Results

Subject baseline characteristics

We retrospectively enrolled 68 subjects with suspected LRTIs who were admitted to Peking University People’s Hospital for machine learning. About 41 subjects were identified as LRTIs, including 28 cases in the training cohort and 13 cases in the validate cohort. Another 27 subjects were identified as non-LRTIs, including 18 cases in the training cohort and 9 cases in the validate cohort. The baseline demographic information, clinical parameters, and laboratory features between LRTIs and non-LRTIs sets were compared with calculated P value on SPSS 26, and given in Table 1 and Dataset S2. We subsequently enrolled another 68 subjects with suspected LRTIs for external validation of the prediction model, which included 45 patients identified as LRTIs and 23 identified as non-LRTIs. The baseline characteristics were also compared on SPSS 26 and listed in detail in Supplementary Table 1 and Dataset S2.

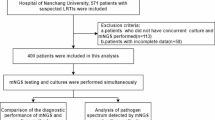

The study schedule was performed according to the flow chart (Fig. 1), including experiment method, microbiome analysis, host transcriptome analysis, and machine learning for building the prediction model.

The RNA sequencing was performed on BALF specimens. The host transcriptome analysis included aligning to the reference genome by STAR, quantifying by RSEM, and analysis of differential expression by DESeq2. The microbiome analysis included the removal of rRNA, estimation of taxonomic abundance by Bracken, and testing the significance of differential abundance of micro-species by edgeR. The 68 cases were used to construct LRTIs diagnosis models. Two-thirds of the samples were used as training cohort, and the remaining one-third were used as validate cohort. We selected host genes with significant differential expression and microbial flora abundance as characteristics to train three typical machine learning models, Random Forest, SVM, and ANN. To further verify the effectiveness of this model, we verified it in an independent dataset of 68 cases.

Differential lower respiratory tract microbiome in LRTIs patients versus non-LRTIs patients

Compared to those with non-LRTIs, the microbiota diversity in BALF of patients with LRTIs was decreased (Fig. 2A and Dataset S3). Differences in the microbiota between samples can be visualized by the t-SNE algorithm, where each point represents one BALF sample. Similar samples are relatively close to each other, thus forming different clusters of microbiota compositions. The microbiota of 68 BALF samples consisted of 5 clusters. All samples in cluster 1 are LRTIs samples, the vast majority of cluster 3 samples (except for one) are LRTIs samples, while the majority of cluster 5 samples are non-LRTIs samples, and the LRTIs and non-LRTIs samples in clusters 2 and 4 are mixed (Fig. 2B). We looked at the species with the highest abundance on top of the t-SNE plot (Fig. 2C). In cluster 5 (mainly non-LRTIs samples), the species with the highest abundance in these BALF samples are Corynebacterium xerosis (n = 12) and Rothia mucilaginosa (n = 1), which are the normal members of the respiratory tract microbiome. The species with the highest abundance in all samples in cluster 1 (all LRTIs samples) is the pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae. The species with the highest abundance in conditional most of the samples in cluster 3 (mainly LRTIs samples) are conditional pathogenic bacteria, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In clusters 2 and 4 (mixed), the normal respiratory flora and pathogenic bacteria were interwoven (Fig. 2C).

A Boxplot of Chao1 index, ACE index, Shannon index, and Simpson index. The p-value was calculated by the Wilcoxon test. B Scatter plot with five sub-groups divided by tSNE analysis. C Dot plot with five sub-groups divided by tSNE analysis, dot size indicated the abundance of species. D Barplot of the differential abundance of micro-species plotted by R, bar present relative abundance of species, error bar present 95% CI and P-value from edgeR was on the right side.

The lower respiratory tract microbiome (LRTM) showed that the abundance of oral and pharyngeal commensal bacteria (Treponema denticola, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Filifactor alocis, Corynebacterium dentalis, Leptotrichia hofstadii, and Actinomyces nasicola) in BALF of the non-LRTIs group was significantly higher than that of LRTIs, while the abundance of opportunistic pathogens (Pneumocystis jirovecii, Corynebacterium striatum, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Human betaherpesvirus 5, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Human coronavirus HKU1, Tropheryma whipplei, Aspergillus fumigatus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella aerogenes, Moraxella catarrhalis, Rhinovirus A, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus/baumannii complex) in the LRTIs group was significantly higher than that of the non-LRTIs group (Fig. 2D and Dataset S4). Pneumocystis jirovecii showed the most significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2D).

Differential host transcriptome in LRTIs patients versus non-LRTIs patients

BALF host transcriptome analysis revealed a total of 649 differentially expressed genes, of which 613 were upregulated and 36 were downregulated in the LRTIs group (Dataset S5). The number of DEGs upregulated in the LRTIs group was significantly higher than that in the non-LRTIs group (Fig. 3A). Host DEGs were classified into three clusters, which are mainly enriched in the immune system, signal transmission, infectious disease: viral and bacterial, signaling molecules and interactions, and other pathways. The DEGs enriched in cluster C’s signaling molecules and interaction pathway were significantly more than those in clusters A and B (Fig. 3A).

A Heatmap of host differential expressed genes, these genes were grouped into three sub-sets, each set presenting different KEGG pathway enrichment indicated by the pie chart. B Network of lineages of genes and KEGG pathways, big nodes present pathways, and small nodes present genes colored by log2 fold change. C Dot plot of DOSE enrichment of host differential expressed genes, each dot presents a significantly enriched disease, and the size of the dot indicates enriched gene number. FDR was applied to the color dot.

The DEGs were further enriched by Gene Ontology (GO) (Dataset S6). The DEGs were mainly enriched in infection-immune-related pathways, especially the upregulated DEGs in the LRTIs group, which were mainly enriched in leukocyte-related pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment results of DEGs showed that the DEGs in the LRTIs group were mainly enriched in cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, NF-kappa B signaling pathway, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, chemokine signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, and Th17 cell differentiation (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Dataset S7). Using clusteProfiler, we performed disease enrichment analysis of DEGs in the DOSE database. The results indicate that DEGs are mainly enriched in lung infection-related diseases, such as pneumonia (Fig. 3C and Dataset S8).

Interaction between active lower respiratory tract microbiome and host genes

The interaction between the host genes and the LRTM plays an important role in LRTIs, therefore, we performed a correlation analysis of the host’s differentially expressed genes and the LRTM. Findings indicated that 42 host genes positively correlated with opportunistic pathogens while displaying a negative correlation with normal flora. In addition, four host genes were negatively associated with conditional pathogenic bacteria but positively linked with normal flora (Fig. 4A and Dataset S9). Several genes affiliated with opportunistic pathogens were tied to infection (IFNGR1, WAS) or inflammation (CSF3R, SIGLEC9). Notably, IFNGR1 demonstrated a strong positive correlation with Human coronavirus HKU1. This gene encodes the ligand-binding chain (alpha) of the gamma interferon receptor, pivotal for antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor responses by activating effector immune cells and enhancing antigen presentation23. A robust positive correlation was identified between SIGLEC9 and Rhinovirus A. SIGLEC9, known as Sialic Acid Binding Ig Like Lectin 9, played a significant role. Furthermore, a correlation analysis was performed between specific microbial genes and differentially expressed host genes, revealing a strong association between the alpha-2-macroglobulin family protein of Klebsiella pneumoniae and the host genes TNFRSF1B, CSF3R, and IL6R. Additionally, the peptide alpha-N acetyltransferase MAK3 of Pneumocystis jirovecii showed a strong relationship with the host’s Myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Fig. 4B and Dataset S10). TNFRSF1B, a member of the TNF-receptor superfamily, mediated most of the metabolic effects of TNF-alpha, while the receptor for granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (CSF3) was crucial for granulocyte maturation. CSF3 played a vital role in the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of neutrophil lineages24. The enrichment analysis of the host transcriptome underscored that soluble DGEs were enriched in leukocyte-related pathways. The soluble IL6 receptor (sIL6R), functioning as an IL6 active agonist, induced pro-inflammatory properties of IL6 and played a key role in chronic inflammatory diseases25. MPO served as part of the host defense system for polymorphonuclear leukocytes and exhibited bactericidal activity against various organisms. In stimulated polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN), MPO catalyzed the production of hypochlorous acid and other toxic intermediates, significantly boosting the microbial activity of PMN26 (Fig. 4).

Discriminate LRTIs and non-LRTIs based on lower respiratory tract microbiome and host response

Currently, there are still many challenges in diagnosing LRTIs. Based on this situation, this study attempted to discriminate LRTIs and non-LRTIs based on LRTM, and host gene expression through machine learning. The random forest model was used to conduct feature engineering on differential LRTM and differentially expressed host gene, and finally, 12 features were selected by training and testing, including 6 optimal LRTM features and 6 optimal host gene features. Then we use these features to train, finetune, and test three classical machine learning models: Random Forest, SVM, and ANN. The results showed that the model trained by Random Forest in the validate set had the best performance (Fig. 5A–C and Dataset S11). The model that integrated LRTM and host gene features (ROC AUC: 0.937, 95% CI: 0.832–1) was superior to the single-use of host gene features (ROC AUC: 0.881, 95% CI: 0.736–1) or LRTM features (ROC AUC: 0.881, 95% CI: 0.731–1) and has the highest accuracy (82.9%), precision (85.7%) and recall (85.7%) (Dataset S11). To further verify the effectiveness of this model, we verified it in another independent dataset of 68 cases (Dataset S2C). The results showed that the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of the model were 95.6%, 39.1%, 75.4%, 81.8%, and 76.5%, respectively (Dataset S12).

A ROC curve of the model in validate set, colored lines present different models include features of human genes and microbes. B ROC curve of the model in validate set, colored lines present different models include only features of human genes. C ROC curve of the model in validate set, colored lines present different models include only features of microbes. D Heatmap of features used in the model.

Further analysis of these features showed that the abundance of most opportunistic pathogens in the LRTIs group was higher than that in the non-LRTIs group, conversely, the abundance of most commensal bacteria in the non-LRTIs group was higher than that in the LRTIs group; host genes CSF3R, NBPF19, AL121985.1, RLF, and TNFRSF14 were up-regulated in LRTIs group, while CICP7 was down-regulated in LRTIs group (Fig. 5D). CSF3R and TNFRSF14 may play important roles in host-related features in LRTIs. TNFRSF14 encodes a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily. The encoded protein plays a role in signaling pathways that activate inflammation and suppressive T-cell immune responses. It binds to glycoprotein D (gD) on the envelope of herpes simplex virus (HSV), mediating its entry into cells.

Discussion

LRTIs have high morbidity and mortality1,2,27. In some cases, LRTIs patients and non-LRTIs were fairly similar in terms of clinical characteristics, despite cases meeting the definition of LRTIs, as our study showed in key clinical characteristics (P > 0.05). In order to solve the challenge of diagnosis, this study used machine learning to integrate host transcriptome and LRTM to distinguish LRTIs and non-LRTIs.

The characteristics and diversity of the respiratory microbiome are closely related to LRTIs. A study of children with LRTIs found that the presence and abundance of Haemophilus spp., Streptococcus pneumoniae, and oral species were closely related to infection28. In contrast, the abundance of potentially beneficial bacteria such as Moraxella, Corynebacterium, Dolosigramum, and Helcococcus spp. were lower in infection cases28. A decrease in the diversity of respiratory microbiota can lead to ecological imbalance, with a high diversity of respiratory microbiota in healthy individuals29. A previous study has found a decrease in fungal diversity in ventilated patients with pneumonia30. This study found a significant decrease in the diversity of respiratory microbiota in the LRTIs group, which is consistent with previous studies. This study also found that the abundance of normal flora (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Corynebacterium dentalis, and Treponema denticola) significantly increased in the non-LRTIs group, while the abundance of opportunistic pathogens, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pneumocystis jirovecii and so on, increased in the LRTIs group. It can be seen that the decrease in the diversity of LRTM and the increase in the abundance of opportunistic pathogens are high-risk factors for LRTIs.

LRTIs are caused by the interaction between microbiota and host characteristics rather than a single microorganism28. Therefore, for LRTIs, we need to focus on both the LRTM and the immune response of the host. This study showed that in the state of infection, the upregulated genes in the host are significantly higher than the downregulated genes, which may be related to pneumonia being a high emergency disease.

This study demonstrated that differentially expressed genes in the LRTIs group were predominantly enriched in pathways related to infection or inflammation. Pathogen invasion triggers the activation of the immune system, cytokines, and intricate signaling pathways involved in LRTIs. Pathogen components like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are recognized by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). With the help of chemokines, immune cells such as neutrophils are recruited to the site of infection or injury to capture and eliminate microbes locally through the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). Simultaneously, transcription factors like NF-kappa B and HIF-1 are activated by upstream signals, leading to the expression of various cytokines, including TNF and IL-17 downstream. These cytokines play a crucial role in mediating communication between immune cells and inflammation during the progression of pneumonia.

The interplay between the human LRTM and the host alveolar epithelial cells and the immune system is intricate and influenced by multiple factors31,32. Genera such as Haemophilus and Moraxella in the LRTM upregulate neutrophils by boosting interleukin-8 (IL-8) production, resulting in airway hyperresponsiveness during respiratory viral infections31. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) serves as a critical inflammatory cytokine in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) pulmonary inflammation, with the ability to independently predict mortality33. The enrichment of Proteobacteria in the LRTM of ARDS patients can lead to an increase in TNF-α levels, while the enrichment of Bacteroidetes is associated with its reduction34. This study also identified a notable positive correlation between opportunistic pathogenic bacteria and genes linked to host infection or inflammation. Further analysis indicated a strong relationship between the alpha-2-macroglobulin family protein of Klebsiella pneumoniae and genes related to host infection or inflammation, such as TNFRSF1B, CSF3R, and IL6R. Additionally, the peptide alpha-N acetyltransferase MAK3 of Pneumocystis jirovecii displayed a strong correlation with the host’s infection-related gene MPO. These findings suggest an interaction between the LRTM and pathways associated with host infection or inflammation in LRTIs, potentially influencing the onset and progression of LRTIs. Further validation through cellular and animal experiments is necessary to confirm these observations.

As mentioned above, LRTIs are not diseases caused by a single microorganism, they are the result of the interaction between the LRTM and the host. In conventional clinical practice, LRTIs are usually initially diagnosed based on the patient’s clinical manifestations, radiography data, and inflammatory indicators. Including the respiratory microbiota and the immune response of the host in the construction model may better help clinicians in the discrimination of LRTIs and non-LRTIs. This study used a random forest algorithm to screen out 12 features (6 each for lung differential microbiota and 6 each for host DEGs) that can effectively discriminate LRTIs and non-LRTIs. Most of these features are related to LRTIs. Therefore, a Random Forest model based on the above two aspects of information is expected to be applied to clinical settings for the precise diagnosis of LRTIs biologically and statistically. This study sample size was relatively small, precision and long-term stability of the model were influenced. Therefore, this model cannot completely replace clinical diagnosis for the limitation of the model, but it can serve as a supporting tool for inexperienced clinicians to make clinical diagnoses. The long-term stability of the model can be improved by recruiting more samples. Meanwhile, adjusting the model’s features to enhance the long-term stability of the model requires updating the features and retraining the model. In addition to the microbiome and host transcriptome features, additional features such as metabolome and serum proteome are incorporated to improve the model’s scalability.

This study has several limitations. Although several key respiratory microbiota and host genes have been found to play important roles in LRTIs, their detailed biological functions have not been further validated. This study employed machine learning to identify features for effectively diagnosing LRTIs. However, there is a need to enhance the long-term stability and scalability of the model.

In summary, this study aimed at the clinical difficulty of LRTIs diagnosis, combined LRTM, and host transcriptome information, and used machine learning to construct a model based on 12 features that can diagnosis LRTIs well, which provides a novel strategy for clinical diagnosis of LRTIs.

Data availability

The data set supporting the results of this article has been deposited under the National Genomics Data Center with the BioProject identifier PRJCA017090.

Change history

04 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00658-1

References

Sanz, F. et al. A composite of functional status and pneumonia severity index improves the prediction of pneumonia mortality in older patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33, 437–444 (2018).

Furman, C. D., Leinenbach, A., Usher, R., Elikkottil, J. & Arnold, F. W. Pneumonia in older adults. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 34, 135–141 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia in adults based on metagenomic next-generation sequencing: a prospective multicenter study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 9, 1003–1015 (2020).

Langelier, C. et al. Integrating host response and unbiased microbe detection for lower respiratory tract infection diagnosis in critically ill adults. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E12353–E12362 (2018).

Di Pasquale, M. F. et al. Prevalence and etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, 1482–1493 (2019).

Dickson, R. P., Erb-Downward, J. R., Martinez, F. J. & Huffnagle, G. B. The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 481–504 (2016).

Dickson, R. P. et al. Analysis of culture-dependent versus culture-independent techniques for identification of bacteria in clinically obtained bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 3605–3613 (2014).

Molyneaux, P. L. et al. Outgrowth of the bacterial airway microbiome after rhinovirus exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 1224–1231 (2013).

Tsalik, E. L. et al. Host gene expression classifiers diagnose acute respiratory illness etiology. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 322ra311 (2016).

Ross, M. H., Zick, B. L. & Tsalik, E. L. Host-based diagnostics for acute respiratory infections. Clin. Ther. 41, 1923–1938 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. Clinical utility of in-house metagenomic next-generation sequencing for the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infections and analysis of the host immune response. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, S416–S426 (2020).

Greninger, A. L. et al. Rapid metagenomic identification of viral pathogens in clinical samples by real-time nanopore sequencing analysis. Genome Med. 7, 99 (2015).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Viualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 323 (2011).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 77 (2011).

van de Wetering, D., de Paus, R. A., van Dissel, J. T. & van de Vosse, E. Functional analysis of naturally occurring amino acid substitutions in human IFN-gammaR1. Mol. Immunol. 47, 1023–1030 (2010).

Dong, F. et al. Identification of a nonsense mutation in the granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor receptor in severe congenital neutropenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 4480–4484 (1994).

Garbers, C. et al. Inhibition of classic signaling is a novel function of soluble glycoprotein 130 (sgp130), which is controlled by the ratio of interleukin 6 and soluble interleukin 6 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42959–42970 (2011).

Furtmuller, P. G., Burner, U. & Obinger, C. Reaction of myeloperoxidase compound I with chloride, bromide, iodide, and thiocyanate. Biochemistry 37, 17923–17930 (1998).

Villar, J. et al. Maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality among pregnant women with and without COVID-19 infection: the INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 817–826 (2021).

Man, W. H. et al. Bacterial and viral respiratory tract microbiota and host characteristics in children with lower respiratory tract infections: a matched case-control study. Lancet Respir. Med. 7, 417–426 (2019).

Man, W. H., de Steenhuijsen Piters, W. A. & Bogaert, D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 259–270 (2017).

Krause, R. et al. Characterisation of candida within the mycobiome/microbiome of the lower respiratory tract of ICU patients. PLoS ONE 11, e0155033 (2016).

Kloepfer, K. M. & Kennedy, J. L. Childhood respiratory viral infections and the microbiome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 152, 827–834 (2023).

Perdijk, O., Azzoni, R. & Marsland, B. J. The microbiome: an integral player in immune homeostasis and inflammation in the respiratory tract. Physiol. Rev. 104, 835–879 (2024).

Meduri, G. U. et al. Inflammatory cytokines in the BAL of patients with ARDS. Persistent elevation over time predicts poor outcome. Chest 108, 1303–1314 (1995).

Dickson, R. P. et al. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16113 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Liam Shaw for feedback on a draft version of this manuscript. This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1304300) and the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission Program (Z191100006619100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and H.C. designed and supervised the study. H.C., T.Q., X.Z., M.Z., S.L., Y.Y., Y.G., Y.Z., C.Z., and X.W. obtained the samples and clinical details. T.Q. assisted in extracting the DNA and performing the experiments. H.C. performed the data analysis. H.C. and T.Q. wrote the paper. All authors read, edited, and approved the final paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Qi, T., Guo, S. et al. Integrating respiratory microbiome and host immune response through machine learning for respiratory tract infection diagnosis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 83 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00548-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00548-y