Abstract

Critical bone defects, exacerbated by infections, pose significant challenges to bone healing and homeostasis, necessitating the development of dual-functional biomimetics that combine anti-infective and reparative capabilities. The EGaIn holds promise across various disciplines, though its interactions with microbial cells require further elucidation. This investigation evaluates the antimicrobial efficacy of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules against a spectrum of bacterial, employing electron microscopy. Constructs containing 1.5% PEG-EGaIn hinder biofilm-producing bacteria, while 3% concentrations amplify the biocidal effect. Furthermore, the nanocapsules promoted osteogenic differentiation rBMSCs, evidenced by enhanced mineralization and upregulation of key osteogenic genes. In addressing large bone defects, PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar and ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar constructs serve as potential solutions for bone resorption mitigation and osteo-angiogenesis. Bone-remodeling were validated through μ-CT and histomorphometry confirming no evidence of chronic inflammation or fibrosis. In this study, PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules emerge as potent biocide and bone repair, underscoring their potential in combating antibiotic resistance and enhancing bone healing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In clinical practice, bone regeneration is vital for addressing defects resulting from trauma, congenital malformations, and tumor excision. While several current therapeutic strategies are available to treat such defects, nonunion, or the failure of complete defect closure, remains a persistent clinical issue1,2. Additionally, the tissue response to biomaterial implants encompasses a complex array of biological processes, usually marked by inflammatory and wound-healing responses to injury and a foreign body reaction to the implant. The biomaterial’s composition, degradation rate, morphology, size and shape, porosity, surface roughness, and chemistry significantly influence the protein, cellular, and tissue reactions that occur3,4.

Devices fabricated from conventional biomaterials, including metal alloys, synthetic polymers, and bioinert ceramics with a long-standing history of clinical use, often provoke inflammatory and foreign body reactions, leading to fibrous encapsulation of the implant as a protective mechanism. However, persistent inflammation around the implant can, in some cases, interfere with its function. Understanding the in vivo interactions between materials and tissues in a suitable animal model is a critical step in new implant development to ensure that these interactions either improve or do not hinder the implant’s long-term safety and functionality.

The use of antibiotics, like a double-edged sword, has undoubtedly saved countless lives, but over time, they have also contributed to the emergence of bacteria that are resistant to them, significantly diminishing their therapeutic effects. This presents a significant challenge to the world’s medical systems and necessitates the investigation and development of novel, antibiotic-free antibacterial techniques. Recently, there has been a lot of interest in the application of metal-based nanoparticles (NPs) in medicine5,6,7,8. Metals can be made into nanocapsules by nanostructuring them, which modifies their physicochemical properties and gives nanocapsules distinct properties that set them apart from their bulk counterparts. The most extensively researched of them as antibacterial agents are silver nanoparticles9,10,11. When combined with antibiotics, they have antibacterial efficacy against several bacterial groups and have synergistic effects12. Due to their different method of action from conventional antibiotics, metal-based NPs are expected to be effective against bacteria that are resistant to them6,13,14. Although they frequently target numerous pathways, this makes the evolution of resistance more challenging because the bacterium would have to simultaneously develop various defense mechanisms. Antibacterial action is supported by nanoscale particles' capacity to penetrate bacterial cells more deeply and increase the effectiveness of cellular death. They can make pathogenic bacteria toxic by utilizing various antimicrobial mechanisms. As a result, metal-based NPs present a potentially effective remedy for the issue of antibiotic resistance6,15.

Liquid metals (LMs) based on gallium, such as eutectic gallium-indium alloys (EGaIn) and gallium-indium-tin alloys (Galinstan), have excellent potential as incredibly adaptable materials16,17,18. As a multifunctional material, liquid metal offers innovative approaches, possessing characteristics that span both metallic and non-metallic, organic and inorganic mediums. Gallium (Ga), a semi-metal element, has been found to strongly inhibit osteolysis and has been used clinically to treat hypercalcemia related to osteolysis in patients with tumors19,20. Moreover, Ga has a notable affinity for bone tissues undergoing growth or remodeling. Gallium ions released from Ga have been found to promote early osteoblast differentiation21 and might inhibit RANKL-induced osteoclast recruitment by downregulating NFATc1 expression, without compromising the function of osteoblasts22. With its notable chemical compatibility with biological apatite (HAp) and effective antiresorptive action, gallium (Ga) is increasingly recognized as a potential therapeutic agent for localized treatment of bone metastases and osteoporotic defects23,24. While gallium (Ga) plays a significant role in osteoclast differentiation, there is a scarcity of studies focusing on the mechanisms by which Ga suppresses bone resorption. It is termed a “Trojan Horse“ because of its similarity to iron (Fe), particularly in its Ga3+ form, where its ionic radius nearly identical to that of Fe3+ ion25,26. In the bloodstream, Ga3+ can bind to transferrin (Tf) and be transported into cells through the transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) pathway27. Upon internalization, Ga3+ can interfere with iron-dependent metabolic pathways, leading to alterations in cellular functions. This mechanism underlies the antibacterial properties of Ga25,28. Moreover, research has shown that gallium-based liquid metal exhibits no significant cytotoxic effects29,30. Also, there have been few reports and studies on the anti-bacterial performance of bulk LMs and nano dimensions31. Because of its propensity to destroy bacterial membranes, Ga is effective against both types of infections. In bulk form, Ga-LMs have been shown to be effective against planktonic infections by exerting disrupting pressures on bacterial cells and creating Ga3+ ions that impairs cellular processes, resulting in bacterial death32,33,34. Ga-based LMs may potentially be beneficial at the nanoscale for treating biofilm and planktonic illnesses31,33,35,36.

Embedded bacteria known as biofilms can quickly become pathogenic and can evade host defenses37,38. Bacteria within these structures are often engulfed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), which act as a barrier against both host defenses and exogenous antibiotic treatments, encapsulating them. As a result of the heterogeneous communities that make up biofilms39,40, metabolites and genes for antibiotic resistance can be transferred between different types of bacteria, boosting their overall virulence41. Sadly, the formed multicellular structure represents an underappreciated growth state and possess a strong capacity to resist very high concentrations of antimicrobial compounds, which contributes to the chronic wounds' recalcitrance and rising rate of wound infection42,43,44. For this reason, what if one could address all of these issues by engineering a native-like multi-level biomimetic consisting of the basic building blocks that structurally and compositionally resemble to that of natural bone? In addition, develop a “nano-matrix interface’ to improve osteogenic capacity and inhibit bacterial growth? The overarching goal of this study is exactly this, something we have accomplished in our group by aiming to first assess the biocidal ability of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule against a spectrum of Gram-negative and the Gram-positive bacterial and exploring the anti-bacterial mechanism. The antimicrobial assessment revealed significant findings regarding PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules' bactericidal properties. Electron microscopy examination demonstrated notable alterations in bacterial cell morphology following treatment. Furthermore, curated phenotypic analysis elucidated specific nanobiotic mechanisms, revealing dual-action antimicrobial effects against various bacterial species (Mwangi H. Kevin, Yue Qu, Jia-Feng Liu and Xiumei Wang [Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation of PEG-EGaIn Nanocapsules Against Spectrum of Bacteria]). Notably, these nanocapsules exhibited minimal cytotoxicity toward human lung fibroblast (IMR-90) cells in vitro, suggesting potential biocompatibility through Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting and bacterial cytological profiling (BCP)45. In addition, we went step further to investigate the effect of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules’s efficacy on osteogenic differentiation of rBMSCs evoking mineral depositions in vitro, and how to make use of this potential in vivo for bone repair. Compared to unmodified mimetic (ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar in this case), this new biomimetic scaffold PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar led to improved osteoblast differentiation and upregulation of osteogenic genes. Notably, histological staining showed high capacity of the cell-free mimetic implanted in rat calvarium bone defect to promote reossification, with an almost complete bone healing. Therefore, given PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule’s biocidal effect as well as its ability to modulate osteogenesis in a growth factor-free environment and the high bone forming ability intimately linked with it, we believe that we might finally have discovered a potential golden combination for repairing bone tissue.

Therefore, to investigate the role of interfacial potential in antimicrobial activity, we examined the antimicrobial behavior of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules as metal precursors, characterized by a positive surface potential, attributed to Polyethylene glycol (PEG) functioning as a solid support and polymeric stabilizer. Nanocapsules and nanostructured surfaces are widely used to reduce bacterial adhesion in biomedical applications. Specifically, poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) was used as a model substrate matrix capable of hosting the microbes under investigation. PCL was chosen for its cost-effectiveness, biocompatibility, and biodegradability, coupled with a gradual degradation rate, traits that have secured its approval by the Food and Drug Administration. To this end, we aimed to explore how microbial cells interact with the nanocapsule embedded within the PCL framework46,47. While the antibacterial effects of EGaIn metal nanocapsules on different bacterial strains are well-documented (for a review see ref. 48). Also, in another study, we developed and characterized a new bio-inspired intrafibrillar mineral PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar and ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar matrices45. However, while these biomineralized mimetics showed the potential to induce osteogenic differentiation, as well as promising bone defect healing capacity, the knowledge about if these lamellar matrices could trigger osteogenic differentiation is by no means complete. Therefore, we investigated whether both lamellar matrices could promote bone repair in defects that would otherwise not heal. Specifically, we evaluated the efficacy of the PEG-EGaIn metal as a bio-nanocapsule for bone repair in a rat calvarial model when compared to ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar.

Results

The “visual hallmark” approach via FE-SEM allows us to elucidate antibiofilm architecture and physiology at cellular resolution following functionalized PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule treatment.

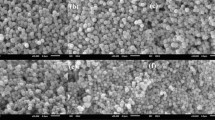

Because Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) is inexpensive, biocompatible, degrades slowly49,50,51, and can bind bacteria from incubation media-factors46,52,53, was selected for the current study. We established the baseline behaviors for the bacteria interacting with PCL (acting as a substratum) (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2). Subsequently, we sought to observe how bacteria would behave differently with the addition of nanocapsule. We used high-resolution field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) for our visual “hallmark“ tool for studying the cellular organization and physiological states of the different strains (i.e., P. aeruginosa (PAO1), S. aureus, E. coli-K12, and susceptibility of ATCC and clinical strains of K. pneumoniae).

E. coli-K12

Representative FE-SEM analysis elucidates significant micromorphological alterations in E. coli K-12 cells subjected to PEG-EGaIn-coated PCL mimetics. At 1.5 wt.%, cells exhibit signs of damage through deep craters and dented surfaces, accompanied by cellular content leakage and aggregated, blebbing membranes (Fig. 1a). Higher concentrations (3 wt.%) provoke intensified membrane depolarization, manifesting as texture abnormalities, blebs, and full membrane rupture, indicating severe cell lysis (Fig. 1b). Noteworthy is the apparent inhibition of cell division at increased exposure, potentially due to nanocapsule interference. Contrarily, unexposed cells on uncoated PCL mimetics preserve standard morphology and structural integrity (Supplementary Figs. 1a, 2a), highlighting the selective impact of PEG-EGaIn coating on E. coli membrane integrity and cellular processes.

a 1.5% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL, b 3% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL. Morphological Changes: (a, b). Asterix = conditioning film deposited onto the PCL-mimetics forming intersecting pore networks covering the entire mimetic framework; Purple arrows and dotted circles = PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules; green arrows= membrane distortion (i.e., telescoping or invaginations) close to the polar and septal regions; pale blue dotted circles = leakage of intracellular contents; Yellow open arrows and dotted circles = abnormal textures (i.e., membrane blebbing and clumping); Orange dotted arrows = Disruption in cell cycle regulation and division (abnormal amitosis), (n = 5).

S. aureus

Staphylococcus aureus subjected to 1.5 wt.% PEG-EGaIn-coated mimetics reveals significant ultrastructural disturbances under FE-SEM (Fig. 2a). Observed morphological anomalies include membrane lysis and clustering displaying similar morphological aberrations to that of the E. coli-K12, alongside cell telescoping or invaginations. Increasing the concentration to 3 wt.% exacerbates damage, causing clumping and the appearance of diverse blisters on the cell surface, culminating in membrane rupture and cellular content leakage (Fig. 2b). Despite notable variations in cell ultrastructure, there was elongation of certain cells and instances of amitosis, indicative of stress-induced morphological adaptations. Control samples, treated with uncoated PCL mimetics, maintain conventional spherical or ovoid shapes (indicating active metabolism)54,55,56 and intact ultrastructures (Supplementary Figs. 1b, 2b). These results underline the disruptive influence of PEG-EGaIn coatings on S. aureus morphology and cellular integrity, evidencing its antimicrobial efficacy.

a 1.5% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL, b 3% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL.Morphological Changes: (a, b). Asterix = conditioning film deposited onto the PCL-mimetics forming intersecting pore networks covering the entire mimetic framework; Purple arrows and dotted circles = PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules; green arrows= membrane distortion (i.e., telescoping or invaginations); pink open arrows and dotted circles = membrane contours displaying blisters or cavitations); pale blue dotted circles = leakage of intracellular contents; Yellow open arrows and dotted circles = abnormal textures (i.e., membrane blebbing and clumping); Orange dotted arrows = Disruption in cell cycle regulation and division (abnormal amitosis) (n = 5).

P. aeruginosa (PAO1)

FE-SEM analyses reveal profound topological changes in P. aeruginosa (PAO1) membranes following interaction with PEG-EGaIn coated-PCL (Fig. 3). Exposure to 1.5 wt.% induces a corrugated, dimpled appearance, indicating membrane-cell wall detachment, alongside dents and perforations that result in cellular content release (Fig. 3a). Higher doses at 3 wt.% significantly reduce bacterial count, manifesting ultrastructural defects like blisters, cavitations, and invaginations, coupled with membrane clumping and cellular aggregate formation (Fig. 3b). These disruptions coincide with compromised cell cycles, pointing towards cellular stress or death, and noticeable leakage, suggestive of osmotic imbalance. Uncoated PCL biofilms retain smooth cellular margins and undamaged structures, underscoring the specific effects of PEG-EGaIn coating (Supplementary Figs. 1c, 2c). Collectively, these findings offer a detailed perspective on the extent of cellular damage inflicted by PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules on P. aeruginosa and highlight its antimicrobial efficacy.

a 1.5% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL, b 3% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL. Morphological Changes: (a, b). Asterix = conditioning film deposited onto the PCL-mimetics forming intersecting pore networks covering the entire mimetic framework; Purple arrows and dotted circles = PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules; green arrows= membrane distortion (i.e., telescoping or invaginations) close to the polar and septal regions;; pink open arrows and dotted circles = membrane contours displaying blisters or cavitations); pale blue dotted circles = leakage of intracellular contents; Yellow open arrows and dotted circles = abnormal textures (i.e., membrane blebbing and clumping); Orange dotted arrows = Disruption in cell cycle regulation and division (abnormal amitosis) (n = 5).

K. pneumoniae: 226 & ATCC strains

Exposure of K. pneumoniae strains to 1.5 wt.% PEG-EGaIn coated-PCL induced severe distortions in bacterial morphology, including rumpling and crater-like lesions on cell membranes, leading to cell death. Abnormal cell division and membrane aggregation were evident, accompanied by compromised Exopolysaccharide (EPS) production and diminished biofilm formation capacity (Fig. 4a-1, b-1 respectively). At 3 wt.%, the nanocapsule exacerbated membrane degradation, inducing roughened surfaces, invaginations, and blistering, indicative of membrane depolarization and cellular integrity breach (Fig. 4a-2, b-2 respectively). Cytoplasmic leakage was observed, confirming the bactericidal potency of PEG-EGaIn-PCL. Biofilm structure was notably absent in treated strains, highlighting disrupted organization and function. In contrast, untreated K. pneumoniae cultures on uncoated PCL maintained regular morphology and intact biofilms, emphasizing the targeted effects of PEG-EGaIn-PCL on bacterial viability and biofilm dynamics (Supplementary Figs. 1d, 2e, respectively).

a1, b1 1.5% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL, a2, b2 3% PEG-EGaIn coated PCL. Morphological Changes: (a1–2) K. pneumoniae ATCC and (b1–2) K. pneumoniae-226. Asterix = conditioning film deposited onto the PCL-mimetics forming intersecting pore networks covering the entire mimetic framework; Purple arrows and dotted circles = PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules; green arrows= membrane distortion (i.e., telescoping or invaginations) close to the polar and septal regions;; pink open arrows and dotted circles = membrane contours displaying blisters or cavitations; pale blue dotted circles = leakage of intracellular contents; Yellow open arrows and dotted circles = abnormal textures (i.e., membrane blebbing and clumping); Orange dotted arrows = Disruption in cell cycle regulation and division (abnormal amitosis), (n = 5).

Liquid metal nanocapsule promotes rBMSCs calcification using live-cell imaging

We further investigated the appropriate treatment dose of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules against rat Bone Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (rBMSCs) (Fig. 5). The 50% cell mortality was confirmed by discrimination of calcein AM/PI staining at respective treatment dosage of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules using fluorescent imaging compared to the untreated (Fig. 5a). To examine the direct effect of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules on rBMSCs viability, the doses (<0.75 g/L) of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule were significantly nontoxic (Fig. 5b) albeit, there was a significant reduction in viability of the cells exposed to 0.85 and 1.0 g/L concentration at each treatment time points. A cytotoxicity test was performed during a 24 h exposure to PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules in accordance with the criteria of the ISO EN 10993 - 5 protocol (the variability value of cells in contact with the nanomaterial must be less than 70% of the negative control to identify cytotoxicity potential). It was observed that when rBMSCs were exposed to PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules at concentrations <0.75 g/L, no toxicity was detected. The results obtained oscillated around 100% of the value to that of untreated cells (Fig. 5d). In contrast, when exposed to concentrations >0.75 g/L, the deviation was significantly lower (indicating a toxic effect).

a Representative merged fluorescent confocal imaging of the treated rBMSCs with PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85, and 1.0 g/L). The cells were stained with Calcein AM and Propidium Iodine (PI) following treatment period (48 h) (n = 6). b Population of live/dead cells presented as a percentage of all counted cells. Data is represented as mean ± SD and values were compared by the repeated measures by one-way AVOVA (n = 4). c CCK-8 assay was performed to determine proliferation rate at different treating time points (1, 3, and 7 d). Data is presented as mean ± SD and significance were compared by the repeated measures by two-way ANOVA test denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001. (n = 6). d CCK-8 assay was performed prior to Live/Dead staining to determine cell viability of rBMSCs treated with gradient series of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85, and 1.0 g/L). Data is presented as mean ± SEM and significance is denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA. Data were normalized with respect to untreated, (n = 4).

This might coincide to the long-term effect of the PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule36,57,58,59. For the subsequent assays, lower doses were chosen as a result. Next, having directly observed how PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule were capable of promoting the proliferation of rBMSCs, we then investigated the involvement of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule in the calcification induction of rBMSCs in conjunction with fluorescent probes to observe live mineralizing rBMSCs. As an intracellular calcium hydroxyapatite (CaP) probe for fluorescent imaging, we used the membrane-impermeable calcium binding fluorescent probe calcein60,61,62. Following the calcification induction with PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule, the pattern of apatite crystallites deposition was detected by calcein staining at the end of each differentiation period at days 7 (Fig. 6a) and 16 (Fig. 6b). This pattern completely overlapped with those observed by phase-contrast, appearing as dense nucleation points that expanded across the indicated time period measured (Fig. 6). LysoTracker Red staining of the mineralizing rBMSCs was used to confirm the fluorescence emission of the calcein-bound mineral deposits63. Lysosomes are involved in a variety of physiological activities, including cellular clearance, bone remodeling, lipid and energy metabolism. Remarkably, there was an overwhelming amount Lyso-Tracker (red staining) intensities in calcifying BMSC regions (Fig. 6a, b), colocalized with calcein labeling (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Fig. 3) at day 16 compared to day 7. This revealed a rapid phase of mineralization when exposed to PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule at concentrations <1.0 g/L, during which the cells deposited mineral over a period of 7–16 days. This pattern is consistent with the currently recognized mechanism of rBMSC osteogenesis, in which the cells pass through several transitional phases before committing to become an osteoblast64.

a, b The cells were cultured with calcein, and stained with Hoechst 33342 and Lysotracker-red at the end of each induction period (days 7 and 16). a Representative confocal live-imaging of the treated cells following calcification induction with gradient series of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules for day7 showed crystalline deposits which produced a particularly distinctive pattern that was easily seen under the phase-contrast as light sheets of nucleation points. b Representative confocal live-imaging following day 16 mineralizing rBMSCs precipitated significant apatite minerals appearing as dense nucleation points that expanded into a continuous matrix. Note the similar pattern of staining visualized by calcein labeling (top-right panel) and lysotracker-red (bottom-right panel); overlap between the phase-contrast (left panel) and merged fluorescent images in composite setting (right panel), scale bars representation 100 μm. Representative pictures are shown, (n = 3).

Osteogenic gene expression of rBMSCs on liquid metal nanocapsule

The next question we addressed was the expression of osteogenic biomarkers at the mRNA level via RT-qPCR which are known to be expressed at different time points during the rBMSCs undergoing osteogenic transdifferentiation (Supplementary Table 1). After induction with PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules, the mineralizing rBMSCs showed significantly higher mRNA expression of all osteogenic markers (Fig. 7). The selected markers were runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), which is associated with activation of osteogenic genes65. In addition, a matrix protein was assessed, Osteocalcin (OCN) which is encoded by bone gamma-carboxyglutamate (Gla) protein (BGLAP), this is a bone-specific protein uniquely secreted by mature osteoblasts and osteocytes and is involved in matrix mineralization by binding to the apatite crystallite66. A matricellular protein, periostin osteoblast specific factor (POSTN), which is involved in preserving bone mass and promoting bone remodeling67. Furthermore, Osteonectin (ON) or SPARC a late osteoblast marker which is associated with metabolic regulation, bone mineralization and calcium ion homeostasis68. Lastly, two other markers involved in the regulation of inorganic phosphate, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALPL) and Ectonucleotide Pyrophosphatase/Phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1) also known as Plasma Cell Membrane Glycoprotein 1 (PC-1)69,70. The expression of ALPL plays a role in bone matrix mineralization. It has been proposed that the activity of TNAP (a tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase/Alpl/Akp2), which is co-expressed with ENPP1/ PC-1 (antagonist regulator) is required to generate the Pi needed for apatite mineralization70,71. The expression of ENPP-1 (potent antagonist in mineralization) is the primary source that regulates extracellular concentrations of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) by mature osteoblast and plays a role in both hard and soft tissue mineralization70,72.

a ON/SPARC b RUNX2 c POSTN d BGLAP/OCN e ENPP1/ PC-1, and f ALPL on rBMSCs following induction with PEG-EGaIn treatments (0.15-, 0.35-, 0.45-, 0.65- and 0.75 g/L) for 7,14, and 21 days. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 6). Data is presented as mean ± SD and significance were compared by the repeated measures by two-way ANOVA test denoted as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data were normalized with respect to gene expression of untreated, (n = 3).

The present study found that PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules treatment induced significant increases in the expressions of RUNX2, and ON (SPARC) after 7 d induction, and an enhancement of mineralization level in the later stages (14- and 21-d induction) (Fig. 7), thus confirming a positive effect of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules on the osteogenic transdifferentiation of rBMSCs in all conditions. ALP, a crucial early-stage matrix mineralization regulator initiated the progress of mineralization at day 7 which later peaked at day 14 and gradually decreased in expression at late-stage (21-d induction) of differentiation. The expression of POSTN was found to be enhanced on day 7 but slight decrease over time was observed on the transdifferentiated rBMSCs from days 14 and 21 (Fig. 7). A similar pattern was observed for the expression of ENPP-1 (PC-1) however, this trend was maintained after 14 days with a slight increase of expression on day 21. The endogenous osteocalcin (BGLAP) expression showed concentrated peaks during intermediate period at day 7 and elevated or late-stage mineralization from day 14 and 21.

Bone formation ability of lamellar mimetics in vivo

The investigation employed a murine preclinical fracture model to explore biomaterial-induced re-ossification and bone remodeling mechanisms Fig. 8a. Using critical-sized calvarial bone defects (Ø 5 mm diameter), we evaluated two distinct matrix treatments: ethanolic-mediated Collagen-Apatite (ethanolic-Col-Ap lamellar) and nano PEG-EGaIn Collagen-Apatite lamellar (PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar) composites45. Post-operatively at 12 weeks Fig. 8b, the ethanolic ColAp lamellar demonstrated proliferation of angiogenic vessels primarily at the defect edges with minimal hematoma and mature vessel growth toward the defect center. Contrarily, the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap lamellar promoted segmented vasculature encased in discrete hematoma near the defect perimeter, suggesting localized blood vessel rupture. Notably, extended blood vessels from the defect margin to the center showcased enhanced density, aligning with advanced bone healing stages and the formation of a complex, interconnected vascular network, characteristic of active remodeling. These outcomes reinforce prior studies noting augmented blood flow amid the remodeling phase of bone healing, shedding light on the dynamic interplay between biomaterial selection and vascularization during skeletal repair73,74.

a, b In vivo rat calvarial regeneration within the rat calvaria critical-size defect. Critical-sized bone defects (ca. 5 mm in diameter) were generated in the calvarium of SD-rat. c Three-dimensional µ-CT images were also examined to determine the microarchitecture and distribution of the newly formed mineralized tissue. Representative scale bars 1 mm. e Quantity analysis of the bone formation (BV/TV, Tb. Th, Tb. N and Tb.Sp). Data are represented as mean ± SEM and significance were compared by the repeated measures by one-way ANOVA test denoted as *P < 0.05 between groups ****P < 0.0001 (BV/TV, Tb. Th and Tb.Sp), **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Tb. N) (n = 4). d–f Histological analysis with Hematoxylin & Eosin and Masson’s Trichrome staining of samples at 12 weeks. Representative scale bars 500 µm (d) and 100 µm (f) (n = 4).

Micro-computed tomography (µ-CT) is acknowledged as gold-standard approach for quantifying bone regenerative efficacy in preclinical models75. At twelve weeks post-implantation, both the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap -lamellar and ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar mimetics prompted significant bone re-ossification, nearly closing the calvarial defects entirely. In contrast, the negative control showed minimal signs of mineralization in the central defect area Fig. 8c. Through the measurement of bone volume to tissue volume (BV/TV) ratios in predefined regions of interest, we critically analyzed the trabecular bone formation Fig. 8e. Complementarily, trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and trabecular number (Tb.N) served as a pivotal benchmarks to assess the quality of newly formed bone75, revealing the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar superior performance over the ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar and the negative control Fig. 8e. Trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), which reflects the distance between bone elements, serves as an inverse indicator of bone quality, with larger values denoting lower bone integrity Fig. 8e. In all of our experiments, the observed performance trend was: PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar > ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar > negative control.

Twelve weeks post-surgical intervention, histological evaluation via Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E)-staining showcased extensive new bone growth adjacent to defect borders across all biomimetic groups, without any evidence of chronic inflammation or fibrous capsule formation Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 4. The PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar group demonstrated superior ossification, characterized by light pink areas in H&E images, with accentuated dense trabecular structures rich in osteocytes, vessels, and bone marrow Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 4a. Conversely, the ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar mimetic showed fibrous tissue integration containing osteoblasts and emerging bone tissue, with bone regeneration proceeded from the marginal rims of the defects toward the center Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 4b. Regenerated bone was encapsulated by osteocytes and blood vessels, illustrating ongoing bone maturation. As expected, the repair kinetics was most delayed in the negative control group Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 4c, where collagen fibers and connective tissue predominantly occupied the central portion of the defect, confirming defects were critical-sized with bone formation confined to the bone-implant junction. The Masson’s trichrome staining corroborated the previous H&E observations. Specifically, the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar group (Fig. 8fa1, a2) presented an extended area of mineralized bone, highlighting its elevated osteoinductive capacity over the ethanolic-mediated Col-HA-lamellar group (Fig. 8f b1-2). In the ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar (Fig. 8f b1-2) group, the mimetic augmented new bone tissue generation (highlighted in light blue) across the entire defect area. In both mineralized matrices, there was an enhanced emergence of mature bone from the defect margins especially in the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar group (Fig. 8fa1, a2) excluding the osteoid bone phase, thereby attesting to their heightened capability to recruit rat bone mesenchymal stem cells (rBMSCs), thereby facilitating superior bone tissue regeneration, notably surpassing the negative control (Fig. 8f c1, c2). These findings underscore the biomimetic superiority of the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar material in promoting bone formation and suggest its potential for advanced bone regenerative therapies.

Discussions

High-resolution electron microscopy (EM) revealed pronounced alterations in bacterial cell membranes and intracellular components post-exposure to functionalized PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules, aligning with our study (Mwangi H. Kevin, Yue Qu, Jia-Feng Liu and Xiumei Wang [Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation of PEG-EGaIn Nanocapsules Against Spectrum of Bacteria]). aligning with BCP and flow cytometry data showing elevated membrane permeability. Conditioning films (CFs), comprising a plethora of biomolecules, exhibit variable compositions influenced by bacterial types and environmental contexts, akin yet distinct from EPS The study avoided detailed CF analysis, acknowledging its complexity and the need for further investigation. Bacterial adherence to materials, notably affected by CFs and PCL-like mimetics, presented challenges in studying adhesion independent of CFs due to dispersion and deposition phenomena, complicating chemical or physical extraction attempts while maintaining substrate integrity and bacterial-free conditions. These findings underscore the significance of advanced imaging techniques in understanding nanocapsule-bacterial interactions and highlight the intricacies involved in analyzing surface-adhesion dynamics in the presence of CFs76,77,78.

Based on our current and previous interrogation on the different microbes against biofunctionalized nanocapsules (Mwangi H. Kevin, Yue Qu, Jia-Feng Liu and Xiumei Wang [Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation of PEG-EGaIn Nanocapsules Against Spectrum of Bacteria]), the results show possible mechanisms: (1) at first, fast bacterial adhesion occurs on the PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule surface due to the zeta potential and electrostatic interaction. (2) polarization and damage of the cell membrane upon contact of bacteria with the nanocapsule. Penetration of Ga ions or PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule or both directly into the cell, and then their effect on the cell with a defective membrane. (3) bacteria contact directly with nanocapsule due positive zeta potential of PEG-EGaIn, so a small concentration of Ga ions is enough to penetrate the cell and destroy it. (4) mechanical damage to bacterial cells when they contact with PEG-EGaIn coated biomimetics.

The present study, for the first time, reveals that PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules, at concentrations <1.0 g/L, significantly enhances the proliferation and osteogenic potential of rBMSCs. Despite extensive research on the toxicity of PEG-EGaIn constituent ions, systematic investigation of the liquid metal alloy’s impact on rBMSCs, particularly relevant for biomedical applications, has been lacking until now. Recognizing that PEG-EGaIn in vivo or in-vitro interaction with cells features a modified surface chemistry due to protein corona binding79, in our experimental conditions, no serious cytotoxicity is observed across changes in concentrations during osteogenic induction of the rBMSCs at early stage of differentiation (at day 2), to later stage (after 21 days) of culture.

Conventional assessments of osteogenic differentiation via Alizarin Red S staining, though informative, entail cell termination and lack dynamic monitoring capability. Live-cell imaging circumvents these limitations, offering real-time visualization of rBMSC calcification in response to PEG-EGaIn treatments, confirming PEG-EGaIn osteogenic efficacy60,80. Co-localization analysis through LysoTracker Red staining corroborated these findings, showcasing high Pearson’s coefficient matches with calcein-bound mineral signals, particularly pronounced at day 16. Moreover, mRNA expression analyses of osteogenic markers (RUNX2, ON/SPARC, ALPL, ENPP1/PC-1, POSTN, BGLAP/OCN) in mineralizing rBMSCs exposed to PEG-EGaIn confirmed upregulated expression profiles at days 7 to 21. Collectively, these data underscore the safety and osteogenic promotion capabilities of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules on rBMSCs, paving the way for innovative regenerative medicine strategies targeting skeletal repair and vascularization. This was further substantiated in vivo via the µ-CT images showcasing the growth of new bone in the damaged bone area. Moreover, µ-CT quantitative analysis reveals that the mimetic composed of PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar have the potential to improve as well as resist external forces compared to the other groups. Based on the histomorphological and Masson images of bone sections, it is evident that the bone tissue in the PEG-EGaIn-Col-Ap-lamellar and ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar matrices appeared to be relatively complete compared to the control group which was inadequate.

Amidst the pursuit for optimal biomaterials to serve as supportive matrices for bone repair, EGaIn nanocapsules present themselves as promising candidates due to their dual capability of stimulating bone reconstruction and combating microbial threats (Fig. 9)36,81.

Microbial presence and its metabolites affecting the orthopedic implant. The PEG-EGaIn nanomaterial targeting to bone infection by destroying and disordering the bacterial membrane. The Col-Ap-lamellar construct containing PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules can enhance bone regeneration by activating skeletal interoception.

Nevertheless, recognizing the complexity of this domain, our study acknowledges several limitations. For example, FESEM though visually informative, lacks the capacity to fully capture the subtle dynamics of cell-substrate and intercellular interactions pertinent to biofilm development. Moreover, despite demonstrating remarkable biocidal efficacy in vitro, necessitates caution as in vivo investigations have not yet been undertaken due to biosafety concerns, underscoring the need for comprehensive evaluations within animal models. Nonetheless, both in vitro and in vivo assays have established the biocompatibility and bone regeneration potential of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules, largely attributed to their unique nanostructural aspects. An inclusion of autologous bone grafts as a reference point in clinical evaluations would provide a meaningful comparison, elucidating the regenerative potential of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule-integrated architectures. Finally, by employing a quantitative multimodal imaging strategy, one could envision this by tracking the sequential stages of osteo-vasculogenesis in vivo. Real-time analysis of neovascularization and bone generation could offer definitive assessments of mimetic efficacy, guiding incremental advancements to accelerate clinical realization.

These advances collectively augment the scientific foundation for liquid metal nanocapsules in biomedical applications, ushering a new era in the innovation of next-generation bio-integrative solutions.

Methods

Materials

poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL, ~80 kDa) and ethanol (200 proof, anhydrous) were obtained from stock on hand and used as received (Sigma Aldrich), 1,4-Dioxane was purchased from Merck Chemicals (Germany), hydrochloric acid (certified ACS Plus) was purchased from Fisher, Polyethylene glycol (molecular weight 35,000 g mol–1, Sigma-Aldrich, Ga shot (99.9999% purity) and In shot (99.9999% purity) were purchased from Indium Corporation and combined to produce EGaIn (25.5 atom % In, 75.5 atom % Ga) as needed. 1-dodecanethiol ((C12SH) ≥ 98%) was purchased from Aladdin.

Fabrication of EGaIn nanocapsules

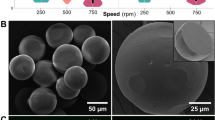

EGaIn nanocapsule was fabricated according to36,82,83 slight modifications were made. A small quantity of EGaIn (0.6 mL) is introduced into a 20 mL, 28 mm OD borosilicate glass vial) with a negligible quantity of halide acid (HCL final concentration of 100 mM) is included in the glass vial to avert the development of an oxide layer. Prior to the start of ultrasonication, 14.4 ml solution containing 64 mM 1-dodecanethiol (C12SH) in ethanol solution were added to allow ligand attachment during the nanocapsule formation process. To produce nanocapsule, the vials were then immersed (approximately half the vial height) into a chilled water bath maintained at 4–10 °C to minimize undesired side effects brought about by the high suspension temperature during ultrasonication. A 3 mm tapered microtip powered by a Sonics and Materials, Inc., VCX 500 ultrasonic processor was then immersed into the open vial (~1 cm from the bottom). The opening between the vial and probe microtip was covered as completely as possible with Parafilm M to aid in solvent retention. Sonication was achieved at a power level of 80% and with a pulse mode (45 s pulses with 15 s delay in between) for <5 min (the actual total sonicating time is 3 min). After beginning ultrasonication, the liquid in the vial was observed to darken, indicating production of EGaIn nanocapsule. To recover purified particle suspensions following ultrasonication, particle suspensions were centrifuged at 800 rpm for 10 min followed by redispersion in fresh ethanol. This process was repeated three times to remove excess unbound thiols. Next, 30 ml of Polyethylene glycol (PEG) was incorporated and ultrasound pulses under the similar conditions for 1 h. Separation of the EGaIn nanocapsules (diameter < 200 nm) was achieved by centrifugation at 6300 × g for 15 min. This supernatant was mixed with four times larger volume of deionised water and centrifuged at 7000 × g for 12 min each time. After the final centrifugation step, the nanocapsule dispersions (ethanol) were stored in capped vials until performing further sample preparation or analysis.

Construction of PEG-EGaIn grafted PCL matrices

Nanocapsule-coated PCL constructs were synthesized using a modified procedure based on the existing approaches84,85. In brief, the pristine solution was 10% (w/v) PCL in 1,4-dioxane and poured into a polystyrene mold (lattice matrices of (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm × 0.6 cm). The resulted PCL film was transferred and stored at – 20 °C overnight and subsequently freeze-dried at − 54 °C for 48 h.

Next, various volumes of the synthesized PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule solutions were poured into the container of the airbrush and sprayed uniformly on the surface of the PCL frameworks. Different volumes of PEG-EGaIn colloidal solution were used to prepare the PEG-EGaIn grafted PCL matrices with various PEG-EGaIn contents: 1.5% wt/vol and 3% wt/vol. Caution was taken to homogeneously disperse the nanocapsules to the PCL matrix without agglomeration. Obtained grafted constructs were transferred and stored at – 20 °C overnight and subsequently freeze-dried under the same conditions as for the PCL constructs.

Finally, the PEG-EGaIn grafted PCL matrices were then shaped into a disc for in vitro microbial evaluations (Ø 5 mm, ht. 0.5 mm).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

laboratory strains: Escherichia coli-K12 (E. coli-K12; M41655), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus-RN4220 (ATCC 35556), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (CGMCC1.12483) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC-43816). Clinical strain: Klebsiella pneumoniae (226) was also used. These microbes were all grown at 37 °C in liquid LB Miller medium for 16 h with shaking (330 rpm) for experimental purposes. Different bacterial strains used for biocidal studies, like Escherichia coli-K12 (E. coli-K12; MG1655) was a kind gift from Professor Yixin Huo at Tsinghua University; Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC-43816) was a kind gift from Professor Jin-ren Zhang at Tsinghua University; the clinical multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains 226 provided from Union Hospital, Beijing, China. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus-RN4220 (ATCC 35556), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (CGMCC1.12483) was a kind gift from Professor Jintao Liu at Tsinghua University. All microorganisms were stored in cryotubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at –80 °C.

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

The P. aeruginosa (PAO1), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (ATCC and 226) and Escherichia coli-K12 (E. coli-K12) were untreated or treated with functionalised PEG-EGaIn nanocapsule and then collected by centrifugation (13,000 g) at 4 °C for 3 min. The pellets were washed twice with sterile PBS, and the bacteria were fixed overnight in a mixture of cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate or cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). The bacteria were then postfixed for 90 min in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M phosphate or cacodylate buffer at room temperature. The samples were washed briefly with deuterated H2O2 and then subjected to two rounds of dehydration in a graded series of ethanol solutions (50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 95, and 100% ethanol). The samples were then treated with a mixture of propylene oxide and Epon epoxy resin (Embed 812, nadic methyl anhydride, poly Bed 812, dodecenylsuccinic anhydride, and dimethylaminomethyl phenol; Electron Microscopy Polysciences). Finally, the samples were embedded in epoxy resin. The epoxy resin-embedded samples were loaded into capsules and polymerized by heating to 38 °C for 12 h and then to 60 °C for 48 h. Sections (1 nm thick) were cut for light microscopy and stained with 1% toluidine blue on a hot plate at 80 °C for 45 s. Ultrathin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Leica EM UC7, USA) and collected on a copper grid. Areas appropriate for thin sectioning were cut into 65-nm sections and stained with saturated 4% uranyl acetate and 4% lead citrate before examination under electron transmission microscopy (TEM) using a (H-7650B, Hitachi, Japan) microscope operated at at 80 kV or in high-resolution electron transmission microscopy (HRTEM) images were obtained on a JEOL 2100 STEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) using a LaB6 electron source at an accelerating voltage of at 80 kV was used for imaging.

The antimicrobial formation assessment

Before the anti-bacterial evaluation, the grafted mimetics were sterilized in 75% ethanol for 5 min and by exposing them to ultraviolet light for 1 h. The pieces were inserted with sterile tweezers in a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate and prewetted overnight in HBSS (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ negative) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Finally, the constructs were treated in growth medium composed of DMEM/F12 and incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C overnight. Successively, the medium was discarded and the constructs were air-dried in a TC flow-hood prior to seeding taking place. The suspension of different bacterial strains to be used to evaluate the anti-infection properties of PEG-EGaIn grafted PCL mimetic cellular population was maintained in liquid culture of Luria Bertani Broth (LB). Prior to this, the diluted bacterial liquid (1 × 107 CFU ml−1) was dropwise added into the PEG-EGaIn grafted PCL mimetic pieces and incubated for 2 h. After the adhesion period, 100 μL LB was added to each placed film pieces on a 96 well plate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under 80–90 rpm orbital shaking in a Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Tecan Spark) or (Tecan Infinite 200 Pro plate reader). PCL matrices housing the different bacteria strains were collected after 8 h and 24 h of incubation under similar conditions. The PCL matrices without inoculum served as negative controls.

High-Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM)

Scanning electron micrographs were obtained using a field-emission gun scanning electron microscope ((FE-SEM), Merlin Compact, Zeiss, Germany) operating at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. For cellular imaging, all specimens were affixed, using 3% glutaraldehyde/formaldehyde, dehydrated in an ethanol series and coated with 10 nm platinum prior to imaging. The resultant images were analyzed using Image J software.

Cell culture

The rBMSCs (Procell, China; CP-R131) were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The growth medium was DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The FBS supplemented in our rBMSCs culture medium was pre-filtered through 0.22 μm membranes to eliminate most of the FBS-originated MVs in the analysis. Cells were kept in culture for no more than 7 passages, and the medium was refreshed every four days.

Live-dead discrimination through confocal microscopy

Cellular viability of the rBMSCs was assessed using a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The rBMSCs (5 × 103 cells/well) were expose to varying concentrations of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15–1.0 g/L) in a 96-well microtitre plate, a protocol modified from ref. 59 was used for 48 h at 37 °C. The visualization of calcein AM (live cells)/Propidium Iodine (PI-dead cells) were obtained using ZEISS LSM900 with Airyscan-2 fluorescent microscope.

Cellular cytotoxicity test

CCK-8 Assay kit (Biosharp, China) was used to detect cells (5 × 103 cells/well) verify the effect of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85 and 1.0 g/L) on rBMSCs under a humidified atmosphere with 95% humidity and 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. Finally, each well was treated with CCK-8 solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions and measured using a spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer EnSpire™ Multimode Plate Reader). Following the incubation, the OD value of each well was measured at 490 nm.

Cell viability assay

The rBMSCs were seeded in 96-well plates (2.5 × 103 cells/well) and exposed to varying concentrations of PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85 and 1.0 g/L) with six plicate wells for each sample. CCK-8 assay (Biosharp, China) was used to detect cell activity and observe cell proliferation after 1, 3, and 7 days of culture. According to manufacturer’s instructions, we examined the cell proliferation measured at 450 nm on a microplate reader (PerkinElmer EnSpire™ Multimode Plate Reader).

Osteogenic differentiation

For the induction of osteogenic differentiation, rBMSCs were used at passage 4–7. Osteogenic cocktail (mineralization medium) was prepared as followed: 10 nM dexamethasone, 3.5 mM beta-glycerol phosphate, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). Following the confluency of rBMSCs (5 × 103 cells) cultured in confocal dishes (Biosharp, China) (n = 6), osteogenic potency of solid PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules (0.15, 0.35, 0.45, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85 and 1.0 g/L), a protocol modified from ref. 59 was used. In short, mineralization medium containing PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules were added during the induction process whereas, mineralizing medium only served as control/untreated. The medium was replaced every 2 or 3 days.

Calcification assessment

For Calcium content of live cells, was determined through a modified procedure based on previously described63,80. In short, cells were exposed to mineralization medium containing PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules during the induction process for days 7 and 14. Calcein (obtained from Sigma Aldrich) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml was directly introduced into the mineralization medium on day 4 of induction. Thereafter, it was added each time the medium was renewed. At the conclusion of each induction phase, the cells, which had either been treated solely with the calcification culture medium or exposed to PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules, were rinsed once with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (1 x HBSS, lacking Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ from Biosharp, China). Subsequently, the cells were stained with either LysoTracker Red DND - 99 at a dilution of 1:10,000 (from Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (from Biosharp) for a duration of 15 min at 37 °C. After staining, the cells were washed three times with HBBS (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ negative) and Live Cell Imaging Solution (from Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the presence of Pro - Long Live Antifade Reagent (from Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Live-cell imaging was performed with the ZEISS LSM900 with Airyscan-2 fluorescent microscope.

Colocalization analysis

Frequency scatter plots and Pearson’s colocalization coefficients86 were obtained with the Mander's coefficient plugin (Tony Collins and Wayne Rasban, Wright Cell Imaging Facility, Toronto, Canada) in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health Bethesda, MD [http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/]). Note that Pearson’s coefficients close to 1 are indicative of reliable colocalization.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNAs from osteogenic rBMSCs were extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extraction of RNA was performed using the phenol-chloroform method and purification was done using the RNeasy Minikit (QIAGEN), in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. The extracted RNA of biological replicates were pooled in groups of 3–4, in order to increase the RNA quantity in each sample, resulting in 4 plicates per condition. RNA purity and quantity were determined using a Nano-Drop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each sample, 1 µg of RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, CA, United States) following manufacturer’s instructions. Amplification of cDNA (250 ng) by qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix for qPCR (Bio-Rad). The melt curve was also performed and analyzed to avoid any contaminations. The relative mRNA levels were obtained using the comparative Ct method and normalized with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Primer sequences for each marker can be found in Table S1.

Surgical proceedings

In this study, 10–12-week-old male wistar rats weighing between 250 and 300 g from the Tsinghua University, Laboratory Animal Resources Center (Ethics Committee; protocol number 21-WXM2) were used. The rats were kept in suitable environmental conditions in terms of light, temperature and nutrition.

The mice were anesthetized using Isoflurane 1–1.5%. Once under a deep plane of anesthesia, the surgical site was prepared by shaving the fur on the top of the head with an electric clipper and cleaning with betadyne solution followed by 70% ethanol (repeated three times). A U-shaped sagittal incision was made in the same direction from left ear to the opposite direction to the right ear. The skin overlying the calvarium was then aseptically dissected and retracted using iris scissors and reflected to expose the surface of the calvarium. Loose adherent connective tissue was gently dissected from the bone surface with sterile forceps under a dissection microscope. Using a 5 mm-diameter inner drill bit (3i Implant Innovations, Inc.), a Ø5 mm-diameter surgical defect was made at the center of the parietal bone, maintaining the integrity of the dura mater. Any debris or bone chips remaining were irrigated with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (1 x HBSS, lacking Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ from Biosharp, China) supplemented with 1000 IU/ml penicillin and 1 mg/ml streptomycin (35 ml/kg). Next, preformed PEG-EGaIn-ColAp-lamellar and ethanolic-mediated Col-Ap-lamellar matrices discs with a diameter of Ø5mm and a height of 1.25 mm were placed in the defect and the skin was closed with sutures. Meloxicam (1 mg/kg, subcutaneous) was administered post-operatively and every 24 h for 3 days to reduce inflammation. Thereafter, daily inspection for signs of distress, or changes in CNS function. Any rat that developed signs of post-surgical stress, or was not moving when stimulated was euthanized through an excessive dose of 2% sodium pentobarbital, 100–120 mg/kg intraperitoneally. Animals were sacrificed as stated previously at indicated time point post-operation for ex vivo end point analysis by micro-CT and histology.

Micro-CT (μ-CT) imaging

To prepare the fixed samples for μCT imaging, we first removed the soft tissue surrounding the skull. The samples were examined with a micro-CT system A Skyscan 1272, a high-resolution 3D X-ray microscope (Bruker, Belgium), with the following acquisition parameters: source voltage and current set at 50 kV and 200 μA respectively, voxel size of 21.7 μm3, scanned in 11-µm slices with a 0.25 mm Al filter and a 0.6 mm rotation step. The scanning was done at 360° with a frame of 5, a resolution of 2016 × 1344, and an acquisition time of ~20 min. A stringent 5 mm diameter region of interest (ROI) was used to assess new bone volume. A smoothing of 3, an artifact ring correction of 17, a beam-hardening correction of 51%, and an image conversion range varying from 0.007 to 0.145. The TRI/3D analysis NRecon software (SkyScan, version 1.8) was used for 3D reconstruction of the regions of interest from the micro-CT images. For standardization, the measurements were made at equivalent sites in all samples.

Histological analysis

H&E staining is a common histological staining that results in the cell nucleus turning blue, keratin, elastic fibers, and fibrin bright red. Slides were put in Hematoxylin (H9627-Sigma) for 7 s, and after washing they were put in Li2CO3 (1.05680-Sigma) for 2 s and then 3 min in eosin (HT110116-Sigma). For dehydration, the specimens were placed in ethanol 90% and 100% for 4 s each. At the end to clarify the tissues, they were placed in xylol and observed with optical microscope. For Masson trichrome staining, specimens underwent dehydration with descending ethanol concentrations, followed by Boen's solution incubation at 56 °C and subsequent washing. Hematoxylin-stained nuclei for 10 min, while Biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin was used next for 10 min. Phosphotungstic-phosphomolybdic acid improved contrast, followed by a final 20-min aniline blue application. Samples were stabilized in 1% acetic acid post-rinsing, dehydrated, and cleared in xylene for optimized viewing. This protocol optimally preserves and highlights tissue characteristics for detailed microscopic examination.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in technical triplicates (n = 3) unless otherwise stated with two independent experiments. We used one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all the biochemical analyses to assess significant differences between timepoints, followed by pair-wise multiple comparison procedure (Tukey’s HSD test or Dunnett’s tests). Experimental data are presented as mean ± SEM if not otherwise specified. The level of significance of p < 0.0001 (****), p < 0.001 (***), p < 0.01 (**), or p < 0.05 (*). The Pearson correction coefficient (PCC) was adopted for the quantification of colocalization following calcifying of rBMSCs exposed to PEG-EGaIn nanocapsules or calcification medium only. Comparison of the different treatment groups for gene expression analysis using qRT-PCR was achieved using two-away ANOVA looking at differences between conditions within each timepoint. Data of new bone formation from µ-CT quantification analysis were expressed as mean ± SD, and one-way ANOVA (Tukey’s HSD test or Šídák's) was performed to assess statistical significance. Microbial confocal assays were performed in tetra plicate. Results were represented as mean ± SEM. Data were statistically computed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). The results of *p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically different.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Any additional requests for information can be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

De Long, W. G. Jr. et al. Bone grafts and bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic trauma surgery. A critical analysis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 89, 649–658 (2007).

Amini, A. R., Laurencin, C. T. & Nukavarapu, S. P. Bone tissue engineering: recent advances and challenges. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 40, 363–408 (2012).

Sheikh, Z., Brooks, P. J., Barzilay, O., Fine, N. & Glogauer, M. Macrophages, foreign body giant cells and their response to implantable biomaterials. Materials 8, 5671–5701 (2015).

Witherel, C. E., Abebayehu, D., Barker, T. H. & Spiller, K. L. Macrophage and fibroblast interactions in biomaterial-mediated fibrosis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 8, e1801451 (2019).

Roope, L. S. J. et al. The challenge of antimicrobial resistance: what economics can contribute. Science 364, eaau4679 (2019).

Slavin, Y. N., Asnis, J., Häfeli, U. O. & Bach, H. Metal nanoparticles: understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 15, 65 (2017).

Wang, L., Hu, C. & Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 12, 1227–1249 (2017).

Turner, R. J. Metal-based antimicrobial strategies. Micro. Biotechnol. 10, 1062–1065 (2017).

Ipe, D. S., Kumar, P. T. S., Love, R. M. & Hamlet, S. M. Silver nanoparticles at biocompatible dosage synergistically increases bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1074 (2020).

Ramalingam, B., Parandhaman, T. & Das, S. K. Antibacterial effects of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles on surface ultrastructure and nanomechanical properties of gram-negative bacteria viz. Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 4963–4976 (2016).

Cavassin, E. D. et al. Comparison of methods to detect the in vitro activity of silver nanoparticles (AgNP) against multidrug resistant bacteria. J. Nanobiotechnol. 13, 64 (2015).

Smirnov, O. et al. Bactericidal activity of Ag nanoparticles biosynthesized from Capsicum annuum pericarps against phytopathogenic Clavibacter michiganensis. Naturwissenschaften 110, 15 (2023).

Ciofu, O., Moser, C., Jensen, P. & Høiby, N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 621–635 (2022).

Høiby, N., Bjarnsholt, T., Givskov, M., Molin, S. & Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35, 322–332 (2010).

Frei, A., Verderosa, A. D., Elliott, A. G., Zuegg, J. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. Metals to combat antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 202–224 (2023).

Yi, L., Jin, C., Wang, L. & Liu, J. Liquid-solid phase transition alloy as reversible and rapid molding bone cement. Biomaterials 35, 9789–9801 (2014).

Ilyas, N., Cook, A. C. & Tabor, C. E. Designing liquid metal interfaces to enable next generation flexible and reconfigurable electronics. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 4, e2505018 (2017).

Wang, L., Lai, R., Zhang, L., Zeng, M. & Fu, L. Emerging liquid metal biomaterials: from design to application. Adv. Mater. 34, e2201956 (2022).

Chitambar, C. R. Medical applications and toxicities of gallium compounds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7, 2337–2361 (2010).

Bonchi, C., Imperi, F., Minandri, F., Visca, P. & Frangipani, E. Repurposing of gallium-based drugs for antibacterial therapy. BioFactors 40, 303–312 (2014).

Kurtuldu, F., Mutlu, N., Boccaccini, A. R. & Galusek, D. Gallium containing bioactive materials: A review of anticancer, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties. Bioact. Mater. 17, 125–146 (2022).

Verron, E. et al. Gallium modulates osteoclastic bone resorption in vitro without affecting osteoblasts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 161–192 (2010).

Strazic-Geljic, I. et al. Gallium, a promising candidate to disrupt the vicious cycle driving osteolytic metastases. Biochem.l Pharmacol. 116, 11–21 (2016).

Gómez-Cerezo, N. et al. The response of pre-osteoblasts and osteoclasts to gallium containing mesoporous bioactive glasses. Acta Biomater. 76, 333–343 (2018).

Goss, C. H. et al. Gallium disrupts bacterial iron metabolism and has therapeutic effects in mice and humans with lung infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaat7520 (2018).

Kaneko, Y., Thoendel, M. J., Olakanmi, O., Britigan, B. E. & Singh, P. K. The transition metal gallium disrupts Pseudomonas aeruginosa iron metabolism and has antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. J. Clin. Investig. 117, 877–888 (2007).

Chitambar, C. R. Gallium and its competing roles with iron in biological systems. Biochim. et. Biophys. Acta 1863, 2044–2053 (2016).

Li, F., Liu, F., Huang, K. & Yang, S. Advancement of gallium and gallium-based compounds as antimicrobial agents. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10, 827960 (2022).

Cheeseman, S. et al. Assessment of the cytotoxicity of nano gallium liquid metal droplets for biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 16584–16593 (2022).

Kim, J. -h., Kim, S., So, J. H., Kim, K. & Koo, H. J. Cytotoxicity of gallium-indium liquid metal in an aqueous environment. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 10, 17448–17454 (2018).

Elbourne, A. et al. Antibacterial liquid metals: biofilm treatment via magnetic activation. ACS Nano 14, 802–817 (2020).

Cheeseman, S. et al. Interactions between liquid metal droplets and bacterial, fungal, and mammalian cells (Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7/2022). Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2270035 (2022).

Cheeseman, S. et al. Broad-spectrum treatment of bacterial biofilms using magneto-responsive liquid metal particles. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 10776–10787 (2020).

Cheeseman, S. et al. Antimicrobial metal nanomaterials: from passive to stimuli-activated applications. Adv. Sci.7, 1902913 (2020).

Pourshahrestani, S. et al. Gallium-containing mesoporous bioactive glass with potent hemostatic activity and antibacterial efficacy. J. Mater. Chem. B 4, 71–86 (2016).

Kurtjak, M., Vukomanović, M., Kramer, L. & Suvorov, D. Biocompatible nano-gallium/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite with antimicrobial activity. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 27, 170 (2016).

Bjarnsholt, T. et al. Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen. 16, 2–10 (2008).

Flemming, H.-C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633 (2010).

Flemming, H. C. et al. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575 (2016).

Nesse, L. L. & Simm, R. Biofilm: a hotspot for emerging bacterial genotypes. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 223–246 (2018).

Mah, T. F. Regulating antibiotic tolerance within biofilm microcolonies. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4791–4792 (2012).

Velnar, T., Bailey, T. & Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 37, 1528–1542 (2009).

Wang, Z., Qi, F., Luo, H., Xu, G. & Wang, D. Inflammatory microenvironment of skin wounds. Front. Immunol. 13, 789274 (2022).

Jacqueline, C. & Caillon, J. Impact of bacterial biofilm on the treatment of prosthetic joint infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, i37–i40 (2014).

Mwangi, K. H. et al. Hierarchical intrafibrillar mineralization co-assembled with EGaIn nanocapsules through a one-step collagen self-assembly approach. Mater. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4MA01186D (2025).

Houshyar, S. et al. Liquid metal polymer composite: Flexible, conductive, biocompatible, and antimicrobial scaffold. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 110, 1131–1139 (2021).

De Cesare, F., Di Mattia, E., Zussman, E. & Macagnano, A. A study on the dependence of bacteria adhesion on the polymer nanofibre diameter. Environ. Sci. Nano 6, 778–797 (2019).

Truong, V. K. et al. Gallium liquid metal: nanotoolbox for antimicrobial applications. ACS Nano 17, 14406–14423 (2023).

Bharadwaz, A. & Jayasuriya, A. C. Recent trends in the application of widely used natural and synthetic polymer nanocomposites in bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 110, 110698 (2020).

Gniesmer, S. et al. Vascularization and biocompatibility of poly(ε-caprolactone) fiber mats for rotator cuff tear repair. PLoS ONE 15, e0227563 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Nanostructured dense collagen-polyester composite hydrogels as amphiphilic platforms for drug delivery. Adv. Sci.8, 2004213 (2021).

Ruckh, T. T. et al. Antimicrobial effects of nanofiber poly(caprolactone) tissue scaffolds releasing rifampicin. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 23, 1411–1420 (2012).

Rumbo, C. et al. Colonization of electrospun polycaprolactone fibers by relevant pathogenic bacterial strains. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 11467–11473 (2018).

Saraiva, B. M. et al. Reassessment of the distinctive geometry of Staphylococcus aureus cell division. Nat. Commun. 11, 4097 (2020).

Reichmann, N. T. et al. SEDS-bPBP pairs direct lateral and septal peptidoglycan synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1368–1377 (2019).

Monteiro, J. M. et al. Cell shape dynamics during the staphylococcal cell cycle. Nat. Commun. 6, 8055 (2015).

Kim, J. H., Kim, S., So, J. H., Kim, K. & Koo, H. J. Cytotoxicity of gallium-indium liquid metal in an aqueous environment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 17448–17454 (2018).

Lim, T., Ring, T. A. & Zhang, H. Chemical analysis of the gallium surface in a physiologic buffer. Langmuir 38, 6817–6825 (2022).

Cheeseman, S. et al. Assessment of the Cytotoxicity of nano gallium liquid metal droplets for biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 16584–16593 (2022).

Uchimura, E. et al. In-situ visualization and quantification of mineralization of cultured osteogenetic cells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 73, 575–583 (2003).

Boskey, A. L. & Roy, R. Cell culture systems for studies of bone and tooth mineralization. Chem. Rev. 108, 4716–4733 (2008).

Yeh, S. A., Wilk, K., Lin, C. P. & Intini, G. In vivo 3D histomorphometry quantifies bone apposition and skeletal progenitor cell differentiation. Sci. Rep. 8, 5580 (2018).

Cai, Y., Wang, X. L., Flores, A. M., Lin, T. & Guzman, R. J. Inhibition of endo-lysosomal function exacerbates vascular calcification. Sci. Rep. 8, 3377 (2018).

Infante, A. & Rodríguez, C. I. Osteogenesis and aging: lessons from mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 9, 244 (2018).

Gaur, T. et al. Canonical WNT signaling promotes osteogenesis by directly stimulating Runx2 gene expression*. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33132–33140 (2005).

Moser, S. C. & van der Eerden, B. C. J. Osteocalcin-a versatile bone-derived hormone. Front. Endocrinol.9, 794 (2018).

Conway, S. J. et al. The role of periostin in tissue remodeling across health and disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 71, 1279–1288 (2014).

Lee, N. K. et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 130, 456–469 (2007).

Nam, H. K., Liu, J., Li, Y., Kragor, A. & Hatch, N. E. Ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase-1 (ENPP1) protein regulates osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39059–39071 (2011).

Ermakov, S. et al. Association of ALPL and ENPP1 gene polymorphisms with bone strength related skeletal traits in a Chuvashian population. Bone 46, 1244–1250 (2010).

Addison, W. N., Azari, F., Sørensen, E. S., Kaartinen, M. T. & McKee, M. D. Pyrophosphate inhibits mineralization of osteoblast cultures by binding to mineral, up-regulating osteopontin, and inhibiting alkaline phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15872–15883 (2007).

Terkeltaub, R. Physiologic and pathologic functions of the NPP nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family focusing on NPP1 in calcification. Purinergic Signal. 2, 371–377 (2006).

Claes, L., Recknagel, S. & Ignatius, A. Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8, 133–143 (2012).

Claes, L. et al. Moderate soft tissue trauma delays new bone formation only in the early phase of fracture healing. J. Orthop. Res. 24, 1178–1185 (2006).

Bouxsein, M. L. et al. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro–computed tomography. J. Bone Mineral Res. 25, 1468–1486 (2010).

Garrett, T. R., Bhakoo, M. & Zhang, Z. Bacterial adhesion and biofilms on surfaces. Prog. Nat. Sci. 18, 1049–1056 (2008).

Chamberlain, A. H. L. The Role of Adsorbed Layers in Bacterial Adhesion. In: Biofilms — Science and Technology. NATO ASI Series, Vol 223 (eds Melo, L. F., Bott, T. R., Fletcher, M. & Capdeville, B). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1824-8_6 (1992).

An, Y. H., Friedman, R. J., Draughn, R. A., Smith, E. A. & John, J. In: Bacterial Adhesion to Biomaterial Surfaces (eds Wise, D. L. et al.). Human Biomaterials Applications, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2487-5_2 (1996).

Ke, P. C., Lin, S., Parak, W. J., Davis, T. P. & Caruso, F. A decade of the protein Corona. ACS Nano 11, 11773–11776 (2017).

Hale, L. V., Ma, Y. F. & Santerre, R. F. Semi-quantitative fluorescence analysis of calcein binding as a measurement of in vitro mineralization. Calcif. Tissue Int. 67, 80–84 (2000).

Wang, M. et al. A 3D printed Ga containing scaffold with both anti-infection and bone homeostasis-regulating properties for the treatment of infected bone defects. J. Mater. Chem. B 9, 4735–4745 (2021).

Lu, H. et al. Dynamic temperature control system for the optimized production of liquid metal nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 6905–6914 (2020).

Yamaguchi, A., Mashima, Y. & Iyoda, T. Reversible size control of liquid-metal nanoparticles under ultrasonication. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 12809–12813 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Superior antibacterial activity of gallium based liquid metals due to Ga(3 + ) induced intracellular ROS generation. J. Mater. Chem. B 9, 85–93 (2021).

Kurtjak, M., Maček Kržmanc, M., Spreitzer, M. & Vukomanović, M. Nanogallium-poly(L-lactide) composites with contact antibacterial action. Pharmaceutics 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16020228 (2024).

Manders, E. M. M., Verbeek, F. J. & Aten, J. A. Measurement of co-localization of objects in dual-colour confocal images. J. Microsc 169, 375–382 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yan Yang and Zhao Cheng Guang at the cell biology for helpful recommendations concerning EM sample preparation. We thank Qian Li and Yue Sun from the Cell Biology Facility in Tsinghua University for technical assistance with the 3DHISTECH automatic slide scanner. We acknowledge financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFC2412300) grant. In addition, we like to thank the support from the Key R&D Program in Shandong Province (No. 2019JZZY011106) grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H.K. and Y.Q. conceptualized the main idea of the project and data curation. P.H. assisted with the animal preparations; T.N. assisted with the histological imaging. M.H.K. and Y.Q. wrote the paper and approved the submitted version. JF.L. and X.W. supervised the project. X.W. contributed clarifications and guidance on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mwangi, K.H., Qu, Y., Hu, P. et al. Microanatomy related biocidal activity at cellular resolution and bone reconstruction potential of PEG EGaIn nanocapsules. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00724-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00724-8