Abstract

Osteomyelitis, an infection of bone, is traditionally treated with long-term, systemic, high-dose antibiotics, which can lead to kidney and liver damage and accelerate the development of antibiotic resistance. Localized delivery may mitigate these risks by delivering antimicrobial(s) directly to the site of infection. Herein, innately antimicrobial chitosan hydrogel (CH) containing polylactic acid (PLA) microparticles, each loaded with fosfomycin antibiotic, was used to combat a biofilm-forming strain of Staphylococcus aureus. This dual CH + PLA biomaterial treatment mitigated S. aureus in planktonic and biofilm form in vitro, and in a clinically relevant, implant-associated rat model of chronic osteomyelitis. Notably, only the CH + PLA biomaterial treatment led to a reduction in bone defect area, plasma haptoglobin level, and bacterial burden in bone and soft tissue, compared to hydrogel only. Local treatment of osteomyelitis with the chitosan+microparticle vehicle loaded with fosfomycin mitigated S. aureus pathogenesis and may serve as an effective alternative to systemic antibiotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteomyelitis (OM), an infection of the bone, is most commonly caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)1 and is typically treated with high-dose antibiotic regimens—either intravenously or orally—over extended periods of time. Extended, high-dose intravenous or oral antibiotic administration can become toxic to the liver and/or kidneys2 and can exacerbate the global issue of antibiotic resistance3. The treatment of OM is particularly challenging against biofilm forming strains of bacteria and in dense cortical bone canaliculi4. Localized antibiotic delivery may circumvent these risks by enabling the availability of high concentrations of antibiotic only at the site of infection and improving the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles5. Gold standard local delivery of antibiotic via poly(methyl-methacrylate) (PMMA) cement mechanically supports the bone while the infection is being cleared6 but can contribute to antibiotic resistance by presenting sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations for extended periods of time7 due to incomplete release of the loaded antibiotic8. PMMA cements are also non-degradable, requiring a second surgery to remove the material. Notably, the use of PMMA for infection management has decreased over time, down from 90% in 2006 to less than 40% in 20177.

Alternatives to PMMA for local delivery of antibiotics include polymeric hydrogels and micro/nanoparticles which are easily fabricated, injectable, and degradable. These polymers can also be intrinsically antimicrobial (e.g., chitosan), and provide a more complete release of loaded antimicrobial agent compared to PMMA9. Chitosan is derived from deacetylated chitin, a naturally occurring amino-polysaccharide, and can be formulated as a hydrogel or micro/nanoparticle carrier for antibiotics or other bioactive molecules10. Previous studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial effects of chitosan against bacterial species such as Escherichia coli11 and S. aureus12,13. Chitosan hydrogels can be created by combining chitosan with beta-glycerophosphate, a neutralizing and biocompatible salt, which stabilizes the chitosan in solution through hydrogen bonding. The breaking of these bonds through an increase in temperature causes the solution to act as a thermosensitive, reverse-phase hydrogel1. We have recently demonstrated antimicrobial efficacy of chitosan hydrogels loaded with fosfomycin against S. aureus in vitro13. Others have reported the efficacy of chitosan hydrogels loaded with vancomycin in reducing bacterial burden14,15,16.

Polylactic acid (PLA) is an FDA-approved biodegradable and biocompatible polyester17 which is degraded by simple hydrolysis of its ester bonds. One study reported higher microbial inhibition by electrospraying vancomycin in polylactic-co-glycolic acid nanoparticles compared to free vancomycin18, suggesting biodegradable polymeric materials could be effective as an antibiotic reservoir. Further, vancomycin loaded in chitosan nanoparticles and mesoporous silica nanoparticles and on the surface of nanohydroxyapatite each resulted in increased microbial inhibition and extended vancomycin release compared to free vancomycin14,15,16.

Fosfomycin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic which has demonstrated efficacy against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains19. Although fosfomycin is not a commonly used antibiotic20,21, it is FDA approved for treating uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women22. Importantly, due to fosfomycin’s distinctive mechanism of action—being metabolized by the cell and interfering with the first step of peptidoglycan synthesis23—cross resistance with other common antibiotics, such as methicillin or vancomycin, has not been reported21. Fosfomycin has also demonstrated better tissue penetration than vancomycin, which may enhance treatment of osteomyelitis in the canaliculi19,24.

We have demonstrated fosfomycin (FOS) loaded in chitosan hydrogel (CH) maintained its bioactivity and exhibited slower diffusion than FOS through water, a surrogate measure of hindered release13. Further, by adjusting the FOS concentration, properties of the hydrogel system were tunable. For example, increasing FOS concentration decreased the gelation temperature and increased the antimicrobial inhibition in Kirby-Bauer and planktonic assays13. In this study, to prolong the antimicrobial effects of the FOS-loaded CH in a chronic, implant-associated rat model of osteomyelitis, PLA microparticles containing FOS (PLA-FOS) were loaded into blank CH (CH + PLA-FOS) or into FOS-loaded CH (CH-FOS + PLA-FOS). Our hypothesis was CH containing both free FOS and PLA-FOS microparticles (CH-FOS + PLA-FOS) would have the greatest reduction in bacterial load compared to the CH-FOS and CH + PLA-FOS groups.

Results

Microparticle area characterization

Figure S1 shows the comparison between the 1-, 5-, and 10-second pulse-rest times. The 5-second pulse-rest method was used for all subsequent experiments, as it resulted in the smallest variation in particle size. For the 5-second group, two histograms are reported: (i) the summed area of the all the particles in the bin expressed as a percent of the total area of all particles, and (ii) the number of particles in each bin expressed as a percent of the total number of particles (Fig. 1A). Average ± standard deviation of microparticle area was 6529 ± 6025 µm2. A representative image of the microparticles in a glass dish is shown at 100× magnification (Fig. 1B).

A Histogram showing the distribution of the percent of total microparticle area and percent of microparticle count. Area percent is the summed area of the microparticles in each bin, and count percent is the number of microparticles in each bin, each expressed as percentages of the total area/count. The average ± standard deviation of microparticle area was 6529 ± 6025 µm2 (n = 4). B Representative image of the microparticles (scale bar = 500 μm).

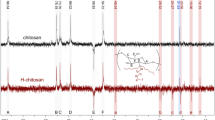

Composition and bioactivity of fosfomycin microparticles

Through EDS analysis, the distribution of elemental phosphorus—indicative of fosfomycin antibiotic—on the surface of and within the microparticles appeared homogeneous (Fig. 2A). Following suspension and dissolution of microparticles in a series of solvents to remove fosfomycin or PLA from the particles, the resulting solutions were placed on a lawn of S. aureus. The antimicrobial activity of FOS from both the surface and interior of the microparticles demonstrates the bioactivity of the FOS was not altered by the microparticle fabrication process. Notably, the zone of inhibition (ZOI) from surface FOS was roughly three times the ZOI from interior FOS, and the sum of surface FOS and interior FOS was approximately equivalent to the control FOS (same dose as theoretically delivered via particles) (Fig. 2B).

A Uniform phosphorus signal from the surface and interior of a representative PLA-FOS microparticle suggests a homogenous distribution of FOS on and within the microparticles (scale bar = 30 µm). B Maintenance of FOS bioactivity after microparticle fabrication. The zone of inhibition (ZOI) of FOS on the surface of the microparticles (surface FOS) was three-fold greater compared to the ZOI of FOS in the interior of the microparticles (interior FOS). The negative controls (right of the dotted line) showed no inhibition from PLA alone or from groups which had been dissolved in acetone, indicating no residual acetone in the surface FOS or interior FOS groups (n = 6, *p < 0.05).

Modified Kirby-Bauer antimicrobial effects

After applying 10 μL of each treatment to a lawn of S. aureus, all treatments resulted in statistically different zones of inhibition (ZOIs) after 24 h (Fig. 3). CH only produced the smallest ZOI as it was the only group without FOS, followed by CH + PLA-FOS, where all the FOS had been loaded within the PLA microparticles, and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, where the FOS had been split equally between PLA microparticles and CH hydrogel. The second largest ZOI was from CH-FOS which had the antibiotic loaded in only the hydrogel, and the largest ZOI was from the positive control PBS-FOS, as none of the antibiotic was contained in any biomaterial.

Planktonic antimicrobial effects

After treatment of planktonic S. aureus with 20 μL of CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, PBS-FOS, or PBS for 24- or 48-h, all groups containing both CH and FOS exhibited a reduction in bacteria from 24- to 48-h (Fig. 4). At the 48-h timepoint, antimicrobial efficacy of these groups was greater than that of the CH and PBS-FOS groups. All groups had lower CFU counts than the PBS negative control at both timepoints.

A reduction in bacteria from 24 to 48 h was observed for the groups containing both CH and FOS. These groups were also lower at the 48-h timepoint than CH and PBS-FOS groups. The PBS negative control was higher than all other groups at 24- and 48-h. a = different than CH, b = different than CH-FOS, c = different than CH + PLA-FOS, d = different than CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, e = different than PBS-FOS, and # = different than 24-h (n = 8, p < 0.05).

Biofilm antimicrobial effects

After treatment of biofilm with 100 μL of CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, PBS-FOS, or PBS, a reduction in CFU was observed for all groups containing both CH and FOS at both 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5). The antimicrobial effect for CH, CH + PLA-FOS, and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS decreased from 24 to 48 h. CH only was more antimicrobial than the PBS negative control at the 48-h timepoint.

A reduction in CFU for all groups containing both CH and FOS was observed at both the 24- and 48-h timepoints. The CH only, CH + PLA-FOS, and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS groups decreased in counts from 24 to 48 h. The CH only group was lower than the PBS control group at 48 h. a = different than CH, b = different than CH-FOS, c = different than CH + PLA-FOS, d = different than CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, and # = different than 24-h (n = 6–8, p < 0.05).

Radiographic analyses

The defect area was measured longitudinally through day 35 via X-ray imaging. Defect area increased for all groups over time, with the groups containing CH and FOS plateauing on day 21, while the CH group continued to increase through day 35 (Fig. 6). On day 35, the defect area for the CH group was larger than that for CH-FOS and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS.

Defect area increased throughout the study, with the groups containing CH and FOS plateauing at day 21, while the CH group continued to increase through day 35. At day 35, defect area for the CH group was larger than CH-FOS and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS groups. a = different than CH, # = different than day 8, % = different than day 14, & = different than day 21, and a = different than CH (n = 11, p < 0.05).

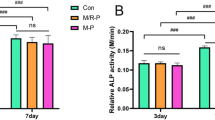

Plasma haptoglobin analysis

Haptoglobin concentration was quantified from plasma collected on days -1, 8, 10, 14, 21, 28, and 35. Haptoglobin peaked on day 8 for all three groups containing FOS but peaked on day 10 for the CH only group (Fig. 7A). Levels for all groups began decreasing by day 10. Since there was no interaction between treatment group and time, the timepoints post treatment application were pooled for overall treatment comparisons. With timepoints pooled, a reduction in haptoglobin concentration was observed in all FOS containing groups compared to blank CH (Fig. 7B).

A Haptoglobin concentrations peaked on day 10 and were subsequently reduced through day 35. # = different than day 8, $ = different than day 10, and % = different than day 14. B When the timepoints were pooled, all groups containing CH and FOS were significantly lower than the CH control group. a = different than CH (n = 10–11, p < 0.05).

Bacterial load in bone and soft tissue

At 35 days post-infection (28 days post-treatment), bacteria in bone and soft tissue were enumerated. Bacterial load in bone was lower in all groups containing CH and FOS compared to the CH only group (Fig. 8A). Bacterial load in the surrounding soft tissue was lower in the CH-FOS + PLA-FOS group compared to CH only (Fig. 8B).

Discussion

Given the dire need for alternative treatment strategies for localized delivery of antibiotics in bone infection, the objective of this study was to engineer a biomaterials-based, composite hydrogel-microparticles approach for treating S. aureus osteomyelitis. Specifically, we evaluated whether the antimicrobial efficacy of a chitosan hydrogel (CH) containing fosfomycin (FOS) antibiotic would be enhanced based on where the FOS was loaded into the biomaterial: either directly into the hydrogel, into polylactic acid (PLA) microparticles loaded within the hydrogel, or halved between the CH and PLA microparticles. As FOS is hydrophilic, and other hydrophilic antibiotics such as metronidazole have exhibited a burst release from chitosan hydrogels25, we employed PLA microparticles as a secondary reservoir for FOS. As the FOS bioactivity results suggest more of the FOS was located on the surface rather than in the interior of the microparticles, a burst release of FOS from the microparticles (and the CH) likely occurred. Unfortunately, our attempts to quantify the release of FOS in the eluant in vitro and in urine (which is the main excretion pathway for FOS) during the in vivo study were unsuccessful. Nonetheless, the CH (and PLA microparticle) system is expectedly extending the release of FOS and potentially protecting FOS from hydrolysis, as evidenced by the delayed (48- but not 24-h) reduction in CFU for the three groups containing both CH and FOS in the planktonic antimicrobial assay, an effect not observed in the CH or PBS-FOS controls.

We have demonstrated the antimicrobial effects of chitosan hydrogels against Gram-positive bacteria in vitro13. Others have shown antimicrobial effects of chitosan hydrogels in vivo in a dermal wound model against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria26,27,28,29. In this work, the addition of FOS to the hydrogel directly, through the addition of PLA-FOS microparticles, and split equally between both vehicles increased the antimicrobial efficacy compared to blank CH in both in vitro and in vivo studies. The distribution of FOS on the surface of and within the microparticles appeared homogenous from EDS analysis. While there was significantly more antimicrobial activity from FOS on the surface than from FOS in the interior, importantly, the microparticle fabrication process did not alter the bioactivity of FOS on the surface of or within the microparticles. FOS must possess an epoxide ring to be biologically active23. However, the degradation product FOS impurity A1,2-dihydroxy-propyl-phosphonic acid, is similar in structure to β-GP30. Therefore, even when FOS cannot inhibit bacteria due to the missing ring, FOS can strengthen the CH, most likely through ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions13, which may slow gel degradation and prolong the availability of the remaining FOS at the site of infection.

In the modified Kirby-Bauer diffusion antimicrobial assay, the PBS-FOS group expectedly had the largest zone of inhibition (ZOI). Also unsurprisingly, the two groups which contained FOS in the CH had the next largest ZOIs. While the chitosan does not bind the FOS directly, we have shown previously that CH slows the diffusion of FOS from the CH matrix13. FOS can be degraded by acids, bases, or nucleophiles, which means chitosan could catalytically degrade the FOS. However, our previous work with this CH-FOS hydrogel showed less than 5% of the FOS reacted with the chitosan, which is most likely covalent attachment of FOS to the amine in the chitosan13. Conversely, the blank CH group had the smallest zone of inhibition, likely due to its higher molecular weight compared to FOS as well as its hydrogel form, both of which likely slowed the diffusion of the CH through the agar gel. FOS is soluble at neutral pH, while chitosan dissolves in acidic solutions. As the modified Kirby-Bauer assay was performed at a neutral pH, likely little to no soluble chitosan was present, suggesting the chitosan did not diffuse, but acted on the S. aureus only where the CH was placed initially. Notably, the two groups containing PLA-FOS microparticles—and especially the group with FOS loaded only in the microparticles—had smaller ZOIs compared to the CH-FOS group, suggesting a more impeded release of FOS from the microparticles than from the CH.

In contrast to the modified Kirby-Bauer agar plate assay, which revealed a large difference between the CH and PBS-FOS groups at 24 h, this effect was abrogated in the planktonic and biofilm assays, likely due to the differing mechanisms of action of chitosan and FOS. Chitosan in solution has been shown to act as a flocculant, causing bacteria to aggregate and preventing bacterial spread through the solution31. This may explain why CH performed as well as FOS in the planktonic assay but not on an agar plate. Further, while chitosan directly disrupts cell membrane integrity causing permeabilization of the membrane32,33,34, FOS must be metabolized to inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis23. Chitosan’s flocculate action may also interfere with proteins responsible for quorum sensing such as AgrB (accessory gene regulator B) and AgrC by sterically hindering the membrane bound receptors from their signaling molecules35. In our prior work, bacterial enumeration on agar plates was difficult likely due to chitosan’s flocculate action and/or interference with the cell membrane13, an effect which was not observed with Petrifilm™ used in this study, as the culture was compressed instead of sheared to enumerate. As most of the FOS and soluble CH/PLA are removed through centrifugation, and the resulting pellet is then diluted 100- to 1000-fold, an antimicrobial effect from any small amount of residual treatment is expected to be negligible.

Notably, the antimicrobial properties of CH and FOS were additive in the planktonic and biofilm assays, as all three groups containing CH and FOS had lower CFU than the groups with either CH or FOS alone. Interestingly, this effect was delayed in the planktonic assay (48 h) but was observed at both 24 and 48 h in the biofilm assay. This additive effect of CH and FOS as early as 24 h on biofilm may be due in part to chitosan’s ability to emulsify with common oils, breaking down polysaccharides and extracellular DNA in biofilm32,36,37,38. This emulsion may have also accelerated the release of FOS from the CH, further contributing to the additive effect at 24 h in the biofilm. By interacting with the DNA double helix, chitosan has also been shown to interfere with protein expression32, which would be a significant benefit when fighting biofilm forming bacteria. Further, chitosan is known to disrupt bacterial quorum sensing39,40, which may have caused the bacteria to shift from a quiescent to an active state and/or maintained them in an active state. Either way, an increase in metabolic activity would likely have increased the effectiveness of FOS—since FOS must be metabolized to inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis—as shown with the lower CFU in the combined CH + FOS groups, compared to the CH or FOS only groups, in both the planktonic and biofilm assays. This may also explain why the CH, but not the PBS-FOS, was more effective against biofilm at the 48-h time point compared to blank PBS, as the CH group may have been in a more metabolically active state41, possibly exhausting nutrients more rapidly. Alternatively, in the biofilm assay, the disruption of the biofilm matrix and/or interference with quorum sensing may have contributed to the increase in CFU between 24 and 48 h for the CH + FOS groups. More investigation is needed to understand the antimicrobial mechanisms of this antibiotic-hydrogel system and to leverage other antibiotics or antimicrobial agents42.

Since the chitosan hydrogel + PLA microparticle delivery systems for FOS antibiotic were effective at mitigating S. aureus in vitro, CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS groups were challenged in a rat femoral implant-associated chronic osteomyelitis model. As expected with chronic osteomyelitis, the area of the defect, as a measure of the extent of osteolysis, increased through day 21 for all four groups. However, for the three groups containing FOS, defect area plateaued at day 21, a timeframe which suggests the adaptive immune response, together with the antibiotic, was able to mitigate further osteolysis43. Conversely, defect area for the blank CH group increased throughout the study and at day 35 was greater than CH-FOS and CH-FOS + PLA-FOS. Even with the limitation of only 2D radiographic images, we were able to detect differences in our treatments by adapting a novel analysis method which quantifies defect area based on grayscale thresholding44. Leveraging more readily accessible imaging modalities such as radiography (as compared to micro-computed tomography) expands the measurable outcomes for future orthopedic research.

Haptoglobin functions to sequester hemoglobin and is upregulated in the presence of inflammation45. It was chosen as the acute phase protein of interest in this study due to its demonstrated utility for tracking inflammation and infection in rats46. The haptoglobin results here suggest a normal immune response to the biomaterial treatments, with haptoglobin levels in the groups containing FOS peaking slightly sooner (day 8) than the CH only group (day 10), at which point it was continually reduced in all groups following treatment through the end of the study at day 35, despite infection persistence. While no effect of treatment was observed at an individual time point, when the time points were pooled, all groups containing FOS exhibited significantly lower haptoglobin concentrations compared to CH only. It is possible the treatments suppressed other proinflammatory markers in addition to haptoglobin; multiplex testing is needed to explore these effects. While the objective of this study was to assess the effects of biomaterial delivery vehicle on infection mitigation, the lack of an infection only (i.e., no treatment) group is a limitation of the study. Nonetheless, baseline haptoglobin levels before the infection surgery were included in the statistical analyses, to account for initial biological variability among animals.

The reductions in defect area and haptoglobin levels in the three chitosan hydrogel delivery systems for fosfomycin were corroborated by the terminal (day 35) CFU quantification. Compared to blank chitosan hydrogel, the three FOS-containing groups reduced the bacterial load in bone. Notably, only CH-FOS + PLA-FOS—which had fosfomycin loaded in both the hydrogel and microparticles—reduced the bacterial load in soft tissue, compared to blank chitosan hydrogel. Compared to the CH only group, a 1.12 and 1.04 log10 reduction in bone and soft tissue, respectively, were observed, which are below the clinically significant difference of 3 log10 reduction47,48. Nonetheless, the reduction in CFU may be the result of an initial burst release of FOS (presumably from the CH and PLA surface) to slow infection progression, along with an extended availability of FOS at the site of infection (presumably from the PLA interior). The degradation timeframe of PLA is reportedly on the order of weeks17, a timeframe similar to most antibiotic treatment regimens49. An initial release of FOS from CH and the microparticle surface would have supported the early immune response to infection, while a more extended release/availability from the interior of the microparticles may have helped bridge the gap between the innate and adaptive immune responses. Likely, the groups containing FOS reduced inflammation by reducing the severity of the infection. Indeed, fosfomycin has been shown to reduce inflammation in a lung trauma model50. Herein, we have confirmed that FOS is located on the interior and exterior of the PLA microparticles and retains its bioactivity following microparticle fabrication, so we expect FOS would have reduced inflammation also in our osteomyelitis model. As additive antimicrobial effects of CH and FOS were observed in vitro, suggesting the CH biomaterial system had a protective/retention effect on FOS, CH and FOS in combination may have also affected the virulence and phenotype (AgrB and/or AgrC proteins) of the bacteria, facilitating immune function in vivo. Additional testing with repeated applications of CH with or without FOS could elucidate this effect. A limitation of the study is the absence of a gold standard treatment of (high concentration) antibiotic only, whether via intravenous delivery or through intraperitoneal injections51, which would better represent the clinical management of chronic osteomyelitis.

In conclusion, fosfomycin antibiotic in chitosan hydrogel and PLA microparticles mitigated S. aureus in planktonic and biofilm form in vitro, and in a clinically relevant, implant-associated rat model of chronic osteomyelitis. Notably, only the biomaterial system with fosfomycin loaded in both hydrogel and microparticles led to a reduction in defect area, haptoglobin level, and bacterial burden in bone and soft tissue, compared to the blank chitosan hydrogel. The development and characterization of multifunctional antimicrobial therapeutics such as these will improve targeted treatment of these challenging, recalcitrant infections.

Methods

Materials

Chitosan powder with low molecular weight (viscosity of 39 cps 1% chitosan in 1% acetic acid) and a degree of deacetylation of 95.5% was sourced from blue water crab shell (Sigma-Aldrich, #448869, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was prepared from tablets (Sigma-Aldrich, P4417, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Fosfomycin disodium salt (FOS) was sourced from MP Biomedicals, LLC, #151876 (Santa Ana, CA, USA). Beta-glycerol phosphate pentahydrate (β-GP) was sourced from EMD Millipore Corp, #35675 (Temecula, CA, USA). Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was sourced from Supelco Titripur®, #1.09057.1000 (Kenilworth, NY, USA). Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) #211059 and DifcoTM Agar Bacteriological #214530 were purchased from BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) as used in previous studies13. 3MTM Petrifilm™ Aerobic Count Plates were purchased from 3MTM. Polylactic acid (PLA) PLA prime NAT 4060D was purchased from Jam Plast Inc. Hexafluoro isopropanol (HFP) #003409 was purchased from Oakwood Chemical. Dimethyl formamide (DMF) 227056-2L was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Deionized water (DI H2O) was produced using a reverse osmosis filter system (Durastill USA).

Polylactic acid microparticle fabrication

For the creation of polylactic acid (PLA) microparticles loaded with fosfomycin (FOS), 5.2 mL of HFP was quickly added to 600 mg of FOS in a glass vial under continuous stirring. Immediately, 100 μL of DI H2O was added to the solution. Once it was clear, 600 μL of DMF was added dropwise, making sure the FOS did not precipitate. 600 mg of PLA pellets were then added to the solution to create a 1:1 mass ratio of PLA:FOS, which was stirred overnight. The PLA-FOS solution was poured onto a 140 mm diameter Petri dish, creating a thin layer of solution, and dried on a hot plate on low heat (60–80 °C set temperature) overnight. Once the PLA-FOS was completely dry, it was scrapped into a coffee grinder inside a dry (relative humidity <10%) hood and ground for 60 seconds total (cycles of 1-, 5-, or 10-second grinding, with a 1-, 5-, or 10-second rest, respectively). The ground material was then filtered through an 80-mesh funnel to collect similarly sized microparticles. The microparticles were stored in a desiccator chamber for up to six months prior to use.

Loading of chitosan hydrogel with fosfomycin

Chitosan hydrogel (CH) fabrication methods were the same as previously published13, except the hydrochloric acid and chitosan powder concentrations were doubled to 0.2 M and 4% w/v, respectively. Either 69.4 mg fosfomycin (FOS) or 138.8 mg PLA-FOS (1:1 mass ratio) was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. 36 μL of this solution was then added to 464 μL of the CH solution in a 1 mL Luer Lock syringe to make a 5 mg/mL FOS treatment for in vitro assays. A second syringe was prepared in the same manner, all solutions were mixed via a dual-syringe system, and the syringes were stored at 4 °C for up to 24 h before use. For the in vivo study, the concentration of FOS was increased from 5 mg/mL to 333 mg/mL, yielding a 50 mg dose in the rat (~200 mg/kg). This dose delivered intraperitoneally in a rat has reportedly a similar plasma concentration as human plasma concentrations following intravenous administration51. This higher concentration was achieved by syringe mixing 2.4 mL chitosan solution with 0.2 mL of PBS, then mixing with either 832 mg FOS, 1668 mg PLA-FOS, or 416 mg FOS and 832 mg PLA-FOS (see Table 1 for resultant concentrations). The resulting solution was separated into 1 mL syringes and incubated overnight prior to use in vivo.

Area characterization of fosfomycin-loaded PLA microparticles

Approximately 100 mg of PLA-FOS microparticles (n = 4) were collected and imaged (Keyence VHX 7000). Due to the microparticles’ hygroscopic nature, imaging was performed within one minute after removal from the desiccator. The images were converted to binary using Otsu’s threshold method52, and microparticle area based on number of pixels was calculated using a custom Python script which detects the boundary of the microparticle and counts the number of pixels within the boundary region. The area of the first 500 microparticles starting from the top left of each image were considered as technical replicates53, as the default method in the Python OpenCV package. This was performed on 1-, 5-, and 10-second pulse-rest time particles.

SEM-EDS imaging of fosfomycin-loaded PLA microparticles

Morphology and chemistry of the PLA-FOS microparticle surface and interior were analyzed by adhering a small amount of microparticles onto carbon tape and sputter coating with platinum for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (JEOL JSM-6500F FESEM with an Oxford X-max 50 EDS and Inca Crystal EDS software). To image the interior of the microparticles, three microparticles greater than 40 µm in diameter were selected at random and embedded in LR White resin with catalytic accelerant. The resin was allowed to set overnight and was sectioned at 20 µm using an ultramicrotome with a fresh glass blade. Sections were placed on an aluminum peg with a drop of 100% ethanol to flatten the section, sputter coated with platinum, and imaged.

Bioactivity of fosfomycin on and within PLA microparticles in a modified Kirby-Bauer antimicrobial assay

To evaluate the bioactivity of FOS after fabrication of the PLA-FOS microparticles, PLA-FOS was suspended in PBS (50 mg/mL FOS) and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected to obtain the FOS located on the surface of the microparticles (surface FOS). FOS powder suspended in PBS (50 mg/mL) served as a positive control (control FOS). PLA pellets in PBS functioned as a negative control (PLA PBS). To expose the FOS from the interior of the particles, the remaining pellet from the PLA-FOS group was dissolved in acetone and centrifuged, and the supernatant was discarded. Any remaining acetone was evaporated from the resulting pellet, which was then dissolved in PBS to yield the remaining FOS (interior FOS). To ensure the methods resulted in complete acetone removal, the Control FOS and PLA PBS groups were also subjected to the centrifugation and acetone evaporation steps (FOS acetone and PLA acetone, respectively).

All samples were prepared and placed onto agar plates within 2 h of the initial particle suspension. As previously described3,13, Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth was used to expand a single colony of ATCC 6538 Staphylococcus aureus with green fluorescent protein chromosomally integrated (ATCC 6538-GFP) overnight at 37 °C. The culture was spread onto BHI agar plates (prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol) to create a lawn of S. aureus. Ten µL of the Surface FOS, Interior FOS, Control FOS, PLA PBS, FOS Acetone, and PLA Acetone (n = 6) was placed onto a lawn of S. aureus. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the elliptical zone of inhibition was calculated by measuring the major and minor diameters of the zone of inhibition.

Modified Kirby-Bauer antimicrobial assay

Using the same method as in the section “Bioactivity of fosfomycin on and within PLA microparticles in a modified Kirby-Bauer antimicrobial assay”, lawns of S. aureus were treated with 10 μL of CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, or PBS-FOS at the concentrations listed in Table 1 (n = 6). Groups were distributed equally across plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the elliptical zone of inhibition was calculated by measuring the major and minor diameters of the zone of inhibition. This assay functions as a high throughput antimicrobial assay, with the efficacy of treatments dependent on their ability to diffuse through the agar.

Planktonic antimicrobial assay

A culture of ATCC 6538-GFP S. aureus (OD600 of 0.2) was centrifuged and resuspended in fresh glucose supplemented BHI broth as previously reported13 but without additional sodium chloride, as NaCl was not necessary for consistent bacterial enumeration with Petrifilm™. 20 µL of CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, PBS-FOS, or PBS negative control were placed into a 24-well plate (concentrations as reported in Table 1, n = 8); then, 500 µL of resuspended culture was gently placed in each well. Plates were cultured for 24- or 48-h at 37 °C at 150 rpm (Corning® LSETM 6790 shaking incubator) before all content in each well was collected, centrifuged, and resuspended in 1 mL PBS. Each sample was serially diluted and plated in triplicate on 3 M™ Petrifilm™ Aerobic Count Plates.

Biofilm antimicrobial assay

40 µL of a culture of ATCC 6538-GFP S. aureus (OD600 of 0.2) was combined with 500 µL of fresh glucose BHI and added to a 24-well plate. The plate was statically incubated at 37 °C for 24-h before the glucose supplemented BHI was removed, the biofilm washed, 100 μL of CH, CH-FOS, CH + PLA-FOS, CH-FOS + PLA-FOS, PBS-FOS, and PBS was added to each well (n = 6–8), and 500 μL of fresh glucose supplemented BHI was added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24- or 48-h before the well contents were collected, serially diluted, and plated in triplicate on 3 M™ Petrifilm™ Aerobic Count Plates.

Chronic osteomyelitis model

All animal procedures were approved by Mississippi State University’s IACUC, #20-153. As described previously, osteomyelitis was established in 13-week-old female CD rats (Charles River Labs) using a 00-90 × 1/4” stainless steel screw coated in 5 × 104 colony forming units (CFU) of ATCC 6538-GFP S. aureus placed in the mid-diaphysis of the femur after drilling a bicortical defect with a 65 gauge drill bit (day 0)3. After 7 days, the screw was removed, the defect was debrided with a 53-gauge drill bit, and treatment was applied (150 µL, n = 11): CH alone, CH-FOS (50 mg), CH + PLA-FOS (50 mg), or CH-FOS + PLA-FOS (25 mg in CH, 25 mg in PLA). Surgeons were blinded to treatments, and treatments were randomized. Longitudinal radiographic imaging and blood collection were performed for 28 days post-treatment. At day 35, infected limbs were harvested for bacterial enumeration in bone and soft tissue.

The animals were monitored twice daily for weight loss, lameness, and surgical site dehiscence, as well as for pain using the rodent grimace scale. Early euthanasia criteria were weight loss over 15% from starting weight, non-resolving lameness or femur fracture, non-resolving dehiscence, and non-resolving grimace scale score. No animals in this study met any of these criteria.

Area of defect quantification

Radiographs of the infected femur were taken on days −1, 8, 14, 21, 28, and 35 (relative to infection, day 0) using an AMI HTX (n = 11). A custom Python script was used to improve the contrast and minimize interference by soft tissue inflammation. Specifically, the contrast was increased until the fibula of the infected limb was barely visible, to minimize any effect of swelling or inflammation on interpretation of the radiographs. As a result of this thresholding, the contrast value was equivalent within each time point and varied slightly across time points. As described in Geiger et al.44, defect area was defined as the darker region on the bone, which we observed to be ~5 to 15 grayscale levels darker on a 256-level scale. The operator was blinded to the treatment groups.

Plasma haptoglobin analysis

200 µL of blood was collected on days −1, 1, 3, 6, 8, 10, 14, 21, 28, and 35 via tail venipuncture and stored in heparin-coated vacutainers on ice. The plasma was separated by centrifuging the samples at 4000 rpm for 8 min (Jouan A14), transferred to clean microcentrifuge tubes, and stored at −80 °C until the end of the study. Haptoglobin in plasma was analyzed via a rat haptoglobin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA, Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc.) following the manufacturer’s protocol (n = 11).

Bacterial load in bone and soft tissue

Rats were euthanized on day 35 via CO2 inhalation, and the femur and surrounding soft tissue were collected using aseptic technique for CFU quantification. The bone and soft tissue were separated and placed into pre-weighed 50 mL tubes containing 10 mL of PBS. The tissue was crushed (bone) or minced (soft tissue), homogenized, and vortexed before the remaining solution was collected, serially diluted, and plated in triplicate on Petrifilm™ (n = 11).

Statistical analyses

All data were statistically analyzed in SAS 9.4 (English) using analysis of variance (ANOVA), repeated measures ANOVA, or mixed model analysis, all with Tukey’s multiple comparisons corrections. Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation except for microparticle count and area, which are presented as histograms. FOS bioactivity data was analyzed without transformation. The Kirby-Bauer data was square root transformed to meet normality and homoscedasticity assumptions. The planktonic and biofilm data were log transformed to meet normality and homoscedasticity assumptions; analysis included well-plate as a random effect, and time and treatment as fixed effects, as all samples were independent. Defect area was analyzed by including surgeon and cohort as random effects and time as an unstructured covariate. Haptoglobin concentration was log transformed to meet normality and homoscedasticity assumptions and analyzed by including baseline concentration as a fixed covariate, surgeon and cohort as random effects, and time as an unstructured covariate. CFU data was log-transformed to meet normality and homoscedasticity assumptions; tissue weight was included as a fixed covariate, and surgeon and cohort as random effects.

Data availability

All data will be provided with the supplemental information in a CSV file.

Code availability

Code is available on Zenodo.org. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16899224.

References

Chenite, A. et al. Novel injectable neutral solutions of chitosan form biodegradable gels in situ. Biomaterials 21, 2155–2161 (2000).

Harbarth, S., Pestotnik, S. L., Lloyd, J. F., Burke, J. P. & Samore, M. H. The epidemiology of nephrotoxicity associated with conventional amphotericin B therapy. Am. J. Med. 111, 528–534 (2001).

Cobb, L. H. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 modified bacteriophage for treatment of Staphylococcus aureus induced osteomyelitis and soft tissue infection. PLoS ONE 14, e0220421 (2019).

Mesy Bentley, K. L. et al. Emerging electron microscopy and 3D methodologies to interrogate Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in murine models. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 376–388 (2021).

Stebbins, N. D., Ouimet, M. A. & Uhrich, K. E. Antibiotic-containing polymers for localized, sustained drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 78, 77–87 (2014).

Orthopedic Devices Branch, Division of General, Restorative, and Neurological Devices, Office of Device Evaluation. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Bone Cement - Class II Special Controls Guidance Document for Industry and FDA. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/guidance-documents-medical-devices-and-radiation-emitting-products/polymethylmethacrylate-pmma-bone-cement-class-ii-special-controls-guidance-document-industry-and-fda#top (2002).

Schwarz, E. M. et al. Adjuvant antibiotic-loaded bone cement: concerns with current use and research to make it work. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 227–239 (2021).

Wall, V., Nguyen, T. H., Nguyen, N. & Tran, P. A. Controlling antibiotic release from polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. Biomedicines 9, 26 (2021).

Bistolfi, A., Ferracini, R., Albanese, C., Vernè, E. & Miola, M. PMMA-based bone cements and the problem of joint arthroplasty infections: status and new perspectives. Materials 12, 4002 (2019).

Elieh-Ali-Komi, D. & Hamblin, M. R. Chitin and Chitosan: Production and Application of Versatile Biomedical Nanomaterials. Int J. Adv. Res. 4, 411–427 (2016).

Tan, H., Ma, R., Lin, C., Liu, Z. & Tang, T. Quaternized chitosan as an antimicrobial agent: antimicrobial activity, mechanism of action and biomedical applications in orthopedics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 1854–1869 (2013).

Tan, H. et al. The use of quaternised chitosan-loaded PMMA to inhibit biofilm formation and downregulate the virulence-associated gene expression of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus. Biomaterials 33, 365–377 (2012).

Tucker, L. J. et al. Physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of thermosensitive chitosan hydrogel loaded with fosfomycin. Mar. Drugs 19, 144 (2021).

Tao, J. et al. Injectable chitosan-based thermosensitive hydrogel/nanoparticle-loaded system for local delivery of vancomycin in the treatment of osteomyelitis. IJN 15, 5855–5871 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Application of vancomycin-impregnated calcium sulfate hemihydrate/nanohydroxyapatite/carboxymethyl chitosan injectable hydrogels combined with BMSC sheets for the treatment of infected bone defects in a rabbit model. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23, 557 (2022).

Sungkhaphan, P. et al. Antibacterial and osteogenic activities of clindamycin-releasing mesoporous silica/carboxymethyl chitosan composite hydrogels. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210808 (2021).

Farah, S., Anderson, D. G. & Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—a comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 107, 367–392 (2016).

Booysen, E. et al. Antibacterial activity of vancomycin encapsulated in poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles using electrospraying. Probiotics Antimicro. Prot. 11, 310–316 (2019).

Dijkmans, A. C. et al. Fosfomycin: pharmacological, clinical and future perspectives. Antibiotics 6, 24 (2017).

Michalopoulos, A. S., Livaditis, I. G. & Gougoutas, V. The revival of fosfomycin. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 15, e732–e739 (2011).

Raz, R. Fosfomycin: an old—new antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 4–7 (2012).

Monurol - Food and Drug Administration. 11 p. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov (2018).

Silver, L. L. Fosfomycin: mechanism and resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 7, a025262 (2017).

Masters, E. A. et al. Staphylococcus aureus cell wall biosynthesis modulates bone invasion and osteomyelitis pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 723498 (2021).

Ren, Y., Zhao, X., Liang, X., Ma, P. X. & Guo, B. Injectable hydrogel based on quaternized chitosan, gelatin and dopamine as localized drug delivery system to treat Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 105, 1079–1087 (2017).

Aliakbar Ahovan, Z. et al. Thermo-responsive chitosan hydrogel for healing of full-thickness wounds infected with XDR bacteria isolated from burn patients: In vitro and in vivo animal model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 4475–4486 (2020).

Wang, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, C., Wang, Y. & Fan, T. Recent development of chitosan-based biomaterials for treatment of osteomyelitis. J. Polym. Eng. 44, 542–558 (2024).

Tao, F. et al. Chitosan-based drug delivery systems: From synthesis strategy to osteomyelitis treatment—a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 251, 117063 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Osteogenic and anti-inflammatory potential of oligochitosan nanoparticles in treating osteomyelitis. Biomater. Adv. 135, 112681 (2022).

Betbeder, D., Klaebe, A., Perie, J. & Baltz, T. Anti-trypanosomal compounds. I. In vivo and in vitro activity of inhibitors of glycolysis in trypanosomes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 25, 549–555 (1990).

Tan, Y., Han, F., Ma, S. & Yu, W. Carboxymethyl chitosan prevents formation of broad-spectrum biofilm. Carbohydr. Polym. 84, 1365–1370 (2011).

Chen, Y. et al. Application of functionalized chitosan in food: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 235, 123716 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Mechanism of antimicrobials immobilized on packaging film inhabiting foodborne pathogens. LWT. 169, 114037 (2022).

Raafat, D., Von Bargen, K., Haas, A. & Sahl, H. G. Insights into the mode of action of chitosan as an antibacterial compound. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 3764–3773 (2008).

Yang, R., Li, H., Huang, M., Yang, H. & Li, A. A review on chitosan-based flocculants and their applications in water treatment. Water Res. 95, 59–89 (2016).

Wang, X. Y., Wang, J., Rousseau, D. & Tang, C. H. Chitosan-stabilized emulsion gels via pH-induced droplet flocculation. Food Hydrocoll. 105, 105811 (2020).

Aranaz, I. et al. Chitosan: an overview of its properties and applications. Polymers 13, 3256 (2021).

Kim, S. Y., Kim, M. & Kim, T. J. Regulation of σB-dependent biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus through strain-specific signaling induced by diosgenin. Microorganisms 11, 2376 (2023).

Nag, M. et al. Functionalized chitosan nanomaterials: a jammer for quorum sensing. Polymers 13, 2533 (2021).

Rubini, D. et al. Extracted Chitosan Disrupts Quorum Sensing Mediated Virulence Factors in Urinary Tract Infection Causing Pathogens. Pathogens and Disease. 77, https://academic.oup.com/femspd/article/doi/10.1093/femspd/ftz009/5364546 (2019).

Felipe, V. et al. Chitosan disrupts biofilm formation and promotes biofilm eradication in Staphylococcus species isolated from bovine mastitis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 126, 60–67 (2019).

Rittershaus, E. S. C., Baek, S. H. & Sassetti, C. M. The normalcy of dormancy: common themes in microbial quiescence. Cell Host Microbe. 13, 643–651 (2013).

Murphy, K. M., Weaver, C., Berg, L. J. & Janeway, C. Janeway’s Immunobiology 10th edn, 800 (W.W. Norton & Company, 2022).

Geiger, M., Blem, G. & Ludwig, A. Evaluation of ImageJ for relative bone density measurement and clinical application. J. Oral. Health Craniofac. Sci. 1, 012–021 (2016).

Wang, Y., Kinzie, E., Berger, F. G., Lim, S. K. & Baumann, H. Haptoglobin, an inflammation-inducible plasma protein. Redox Report. 6, 379–385 (2001).

Gautreaux, M. A., Tucker, L. J., Person, X. J., Zetterholm, H. K. & Priddy, L. B. Review of immunological plasma markers for longitudinal analysis of inflammation and infection in rat models. J. Orthop. Res. 40, 1251–1262 (2022).

Sakoulas, G. et al. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 2398–2402 (2004).

MacGowan, A., Rogers, C., Holt, H. A., Wootton, M. & Bowker, K. Assessment of different antibacterial effect measures used in in vitro models of infection and subsequent use in pharmacodynamic correlations for moxifloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46, 73–78 (2000).

Patini, R. et al. The effect of different antibiotic regimens on bacterial resistance: a systematic review. Antibiotics 9, 22 (2020).

Yildiz, I. E. et al. The protective role of fosfomycin in lung injury due to oxidative stress and inflammation caused by sepsis. Life Sci. 279, 119662 (2021).

Poeppl, W. et al. Assessing pharmacokinetics of different doses of fosfomycin in laboratory rats enables adequate exposure for pharmacodynamic models. Pharmacology 93, 65–68 (2014).

Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 9, 62–66 (1979).

Bradski, G. Open Source Computer Vision (OpenCV). https://docs.opencv.org/4.x/index.html (Intel, 2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Priddy Lab for their assistance with the animal studies. We would also like to thank Drs. Betsy Swanson, Bridget Willeford, Aumbriel Schwirian, Trey Howell, Marc Seitz, Barbara Kaplan and Mississippi State University (MSU) Laboratory Animal Resources and Care staff for their help with development of the animal model and care of the animals. We thank the Institute for Imaging and Analytical Technology (I2AT) at Mississippi State University for their imaging services and technical support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through MSU’s Veterinary Medicine Research Scholars program (T35OD010432) and the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) in Pathogen-Host Interactions (P20GM103646), as well as the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-21-1-0193). Funding was also provided by MSU’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Undergraduate Research Scholars Program, Office of Research and Economic Development Undergraduate Research Program and the Shackouls Honors College Provost Scholarship Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.T.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization, supervision. X.J.P.: Methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization. J.M.D.: Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft. B.E.R.: Methodology, investigation, writing—original draft. M.A.G.: Methodology, investigation, data curation. L.B.P.: Conceptualization, validation, investigation, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tucker, L.J., Person, X.J., DiFiore, J.M. et al. Dual chitosan hydrogel and polylactic acid microparticle delivery system reduces Staphylococcal osteomyelitis and soft tissue infection. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 11, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00840-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00840-5