Abstract

Dental plaque is a complex oral biofilm responsible for periodontal diseases. Bacterial biofilms are often regulated by Quorum Sensing (QS) mediated by N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs). While their presence and roles in oral microbiota have been debated, emerging evidence suggests AHLs influence oral biofilm development. AHLs are detectable in a microbial community derived from human dental plaque cultured under 5% CO2 but not under anaerobic conditions. Manipulating QS in this community via AHL lactonases enriched commensals and pioneer colonizers under 5% CO₂, whereas in anaerobic conditions exogenous AHLs promoted late colonizers. QS disruption reduced biofilm formation, enhanced sucrose fermentation to lactate, and altered metabolic profiles of the community depending on the lactonase substrate specificity. Our findings highlight the importance of AHL-mediated QS in oral biofilm development and suggest its differential roles under aerobic versus anaerobic conditions. Targeting QS may offer a novel strategy for managing oral biofilms and preventing periodontal disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell-density-dependent bacterial communication system mediated by small diffusible signaling molecules called autoinducers (AI)1,2. There are three major types of AIs:(i) AI-1 (N-acyl homoserine lactones or AHLs)3,4,5; (ii) AI-26,7,8,9 consisting of 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentandedione (DPD) derivatives10; and (iii) autoinducing peptides (AIPs), specific to Gram-positive bacteria11. AIs are typically secreted into the environment and can re-enter the cells either by passive diffusion in the case of AI-13 or via active transport for AI-2 and AIPs6,12,13. During re-entry, AIs bind to their target receptors on the membrane (AI-2; AIPs) or in the cytoplasm (AI-1) regulating the expression of numerous genes2. Indeed, QS can regulate up to 26% of the bacterial genome14. By controlling gene expression, QS regulates several bacterial behaviors such as biofilm formation, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance15,16. These behaviors are critical for bacterial adaptation to varying ecological niches, often characterized by hostile environmental conditions and inconsistent nutrient availability17.

Dental plaque is a complex oral biofilm adhering to the tooth surface, and is composed of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic members of oral microbiota18. The core microbiome of the human oral cavity is normally comprised of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, archaea, protozoa, and viruses19,20 that inhabit distinct ecological niches in unique oral environments such as gingival sulcus, tongue, cheek, soft and hard palates, throat, saliva, and teeth21,22. The bacterial taxonomic diversity in the oral cavity includes about 700 species belonging to 185 genera and 12 phyla23,24. The healthy oral microbiome is dominated by Gram-positive commensal bacteria such as Streptococcus and Actinomyces ssp. with high propensity for fermentation.25,26,27. Abrupt ecological changes and alterations of host-associated innate and adaptive immunity in the oral cavity can cause dysbiosis. Dysbiosis is characterized by an increased prevalence of anaerobic Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria with high proteolytic activity, such as Porphyromonas28, often leading to the development of periodontal diseases25,26,27.

Dental plaque formation is characterized by asynchronous spatial and temporal colonization of the tooth surface requiring interactions between several groups of bacteria29,30,31. Interbacterial interactions are hypothesized to depend in part on QS-dependent regulation of cellular metabolism, physiology, secretion, virulence, motility, attachment, and cooperativity/competition32,33. AI-2 and AIPs are known to be important in the development of oral biofilms. Many dental plaque colonizers were shown to produce and/or respond to AI-2,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Gram-positive pioneer colonizers like oral Streptococcus species can utilize AIPs42,43,44,45. Hence, AI-2/AIP-mediated QS appears to be the primary mode of signaling and regulation that contributes to the formation and development of oral biofilms including dental plaque33. The potential role of AI-1/AHL-based QS in the development of dental plaque and other oral biofilms remains elusive. In fact, AHLs were long undetected in cultures of pathogenic oral microbiota36,46,47. Given the lack of identified AHL synthases and receptor homologs in plaque pathogens, AHLs have been considered to make an insignificant contribution to oral biofilm formation48,49.

This paradigm may be ripe for change. Various types of AHLs are found in human saliva samples50,51,52. Sources include the AHL-producing Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas putida53, Enterobacter54, Klebsiella pneumoniae55, Citrobacter amalonaticus56 and Burkholderia57, found on tongue surfaces and within dentine caries. Certain strains of the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis also possess AHL synthase/receptor homologs58,59 and produce small quantities of AHLs in both axenic and multispecies cultures52. Indeed, putative AHL biosynthetic genes exist in oral microbial genomes60. Metagenomic analysis of human dental plaque revealed a high abundance of AHL-synthase (HdtS), receptor homologs and Quorum Quenching (QQ) enzymes61. Muras and colleagues have recently shown50,52,61 that while exogenously added AHLs promote the growth of pathogens in oral communities, AHL-degrading QQ enzymes inhibit oral biofilm formation and alter their microbial composition.

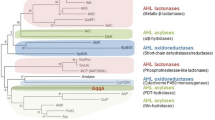

Yet, the specific role(s) of AHL-mediated QS in oral communities remain unclear. To increase our understanding of the importance of AI-1, one strategy is to apply different AHL signals and AHL-degrading lactonases onto oral microbial communities grown under different oxygen conditions and evaluate their effects. Lactonases are QQ enzymes that hydrolyze the lactone ring of AHLs and disrupt AHL-mediated QS62,63,64,65. We have previously characterized a variety of lactonases, including SsoPox from the Phosphotriesterase-like Lactonase (PLL) family66,67,68 and GcL from the Metallo-β-Lactamase (MLL) family69. Interestingly, these two lactonases exhibit distinct, yet overlapping substrate specificities: SsoPox preferentially degrades long-chain AHLs (C8 or longer)68 and GcL is a generalist lactonase with broad substrate specificity69. This distinction is important because AHLs mainly vary by the length and decoration of their acyl chain, and these changes in chemical structure modulate signal specificity65,70,71,72,73. These chemically diverse AHLs are produced and sensed by a variety of bacteria. Therefore, the use of these enzymes may capture signal-specific changes to the oral community. Lactonases reduce the pathogenicity of Gram-negative bacterial species both in vitro74,75 and in vivo76,77,78,79. Lactonases hydrolyze AHLs and therefore quench AHL-dependent QS signaling pathways. QQ downregulates networks of genes, responsible for the production of virulence factors and enzymes that contribute to phenotypes commonly associated with pathogenicity such as antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, host colonization and tissue damage. The substrate preference of lactonases correlates with distinct proteome profiles, virulence factor expression, antibiotic resistance profiles, and biofilm formation16,80,81.

In this study, we investigated the importance of AHL-signaling in biofilms and planktonic cultures of a model human supragingival-origin plaque community82,83 under both aerobic (5% CO2 atmosphere) and anaerobic conditions. AHLs were detected in plaque community cultures using a plasmid-based AHL biosensor and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS). We also evaluated the effects of exogenous AHLs of varying acyl chain lengths (C6 and C12) and QQ lactonases (SsoPox and GcL) with distinct substrate preference on the microbial composition of the plaque community. In response to these treatments, changes in microbial composition and population structure of the community were observed using 16S rRNA sequencing. Additionally, lactonase treatment under 5% CO2 conditions altered biofilm formation, increased the propensity of the biofilms to ferment sucrose to lactate and altered the ability of the community to utilize various carbon sources. Our observations from this study suggest that AI-1/ AHL-based QS is crucially important in determining the pathogenic profile of the oral microbiome.

Results

AHLs are present in supragingival plaque community cultures under CO2 atmosphere but not under anaerobic conditions

Oxygen availability critically affects oral biofilm development and the progression of cariogenic and periodontal diseases84,85. Indeed, oral biofilms experience rapid and continuous changes in oxygen levels, among other physio-chemical changes, which impact the microbial composition of the oral microbiota86,87,88. The oral cavity is normally highly aerobic due to continuous delivery of oxygen through air exposure and the circulatory system. Early (thin) biofilms ( < 100 µm thick) allow rapid oxygen diffusion85, but as plaque matures and thickens, oxygen diffusion becomes limited, creating microaerophilic and hypoxic conditions that favor cariogenic facultative anaerobes such as Streptococcus mutans89,90. Given that AHLs were previously reported in anaerobic co-cultures of Porphyromonas gingivalis with Streptococci52 - two bacteria commonly found in dental plaque – we hypothesized that supragingival plaque communities could produce AHLs in an oxygen-dependent manner.

We investigated the presence of AHLs in a previously characterized oral microbial community derived from the pooled supragingival plaque of five healthy human volunteers82,83 using HPLC-MS analysis. C6-HSL was detected in the supragingival plaque biofilm community cultured under 5% CO2 (Fig. S1A, G) but not in anaerobic cultures (Fig. S1B, G). C6-HSL was present at lower levels in the culture media (Fig. S1C, G), confirming community production rather than medium contamination. C4-HSL was detected in cultures grown under 5% CO2 (Fig. S2A, G) and anerobic conditions (Fig. S2B, G) but was also present in the culture media (Fig. S2C, G), preventing reliable assignment of this compound to community production. Neither C6-HSL nor C4-HSL was detected in saliva samples (Fig. S1D, G; S2D, G, respectively). Despite optimization efforts, our extraction procedure (see methods) was ineffective for longer-chain AHLs, suggesting that additional AHLs beyond C6-HSL may have been present but undetectable due to poor extraction yields.

To further validate AHL presence, we used a PluxI-GFP based plasmid biosensor, which detects AHLs in the 10 nM to 1 μM range, to evaluate the AHL content of these cultures. The biosensor successfully detected and quantified pure AHL standards (C6-HSL; Fig. S3), confirming its functionality. Consistent with HPLC-MS results, the biosensor detected AHLs in supragingival plaque communities grown under 5% CO2, with signals equivalent to approximately 100 nM of C6-HSL (Fig. 1). No AHLs were detected in anaerobic cultures (Fig. S4), confirming the oxygen-dependent nature of AHL production in these communities.

Cell-free culture supernatants of 6 biological replicates of plaque community cultures treated with lactonases 5A8 (inactive lactonase mutant), SsoPox, or GcL were incubated with E. coli AHL biosensor strain JM109 pJBA132. The resulting GFP fluorescence is indicated as relative fluorescence units (RFU) per unit OD600nm of biosensor cultures on the left Y-axis. The equivalent C6-HSL concentration for the corresponding RFU/OD600 values as shown on the right Y-axis was extrapolated from the standard curve of the biosensor response against C6-HSL in Fig. S3 and is only represented as an indication, since the used biosensor is broad spectrum and the reading may be a reflection of many different produced AHLs. Results represent the mean and standard deviation of 6 biological replicate cultures for each lactonase treatment. As each of the cell-free supernatants of 6 biological replicate cultures of the plaque community for all lactonase treatments was further incubated with 6 biological replicates of biosensor cultures, each data point on this graph represents the mean of the 6 biosensor replicates. Statistical significance of all treatments compared to the control (5A8) was calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction and significance values are indicated as - ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05.

To further validate these results, we treated samples with lactonases SsoPox and GcL. Both lactonases significantly decreased biosensor signals: SsoPox reduced signals by 86% (~13.7 nM of C6-HSL equivalent) and GcL by 49% (~50.8 nM of C6-HSL equivalent) (Fig. 1). These reductions confirm that detected signals represent genuine AHL activity rather than biosensor artifacts.

It should be noted that the C6-HSL equivalent concentration values serve as indicative estimates only. Since the biosensor can detect C6-C12 HSLs91 and may recognize multiple AHLs produced by the community beyond C6-HSL, these values may not reflect precise concentrations. The absence of AHLs under anaerobic conditions aligns with previous observations in other anaerobic biofilms92,93, likely indicating that AHL production ceases under these conditions, although alternative explanations, such as extracellular AHL lactonases or acylases secretion cannot be excluded.

CO2 atmosphere conditions affect the population structure of supragingival plaque community

Although supragingival plaque microbial population structure has been previously well documented94,95,96, the effects of varying oxygen conditions on the community remain unclear. This question is particularly relevant because oxygen levels vary dramatically within dental plaque and decrease sharply with increasing thickness97. To address this gap, we analyzed the microbial population structures of a supragingival-origin plaque communities using V4 amplicon sequencing under either 5% CO2 or anaerobic conditions.

The 5% CO2 and anaerobic communities exhibited distinct beta diversity patterns, as demonstrated by clear clustering separation in PCoA using Bray-Curtis distances (Fig. 2A). Statistical analysis confirmed significantly greater differences between oxygen treatment groups compared to within-group variations (ANOSIM: R = 1, p = 0.003 for biofilm samples; R = 1, p = 0.006 for planktonic samples), indicating that oxygen availability is a major driver of community structure.

A Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances of both biofilm and planktonic plaque communities. B Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) of biofilm dental plaque communities. The bar graph of LDA scores shows the taxa (OTU: Operational Taxonomic Unit) with a statistical difference (Wilcoxon test: p < 0.004) between 5% CO2 and anaerobic communities (Only taxa meeting a LDA significant threshold > 4 are shown).

To identify the taxa responsible for discriminating between oxygen conditions, we applied Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) analysis98 to biofilm samples (Fig. 2B). This analysis revealed that four nested taxa characterized the 5% CO2 community, while nine nested taxa distinguished the anaerobic community. Under 5% CO2 conditions, the discriminating taxa are mainly Gram-positive bacteria, including Abiotrophia, Schaalia (formerly known as Actinomyces), a member of Lactobacillales order, and Streptococcus. In contrast, the anaerobic community was mainly characterized by Gram-negative bacteria, including Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Haemophilus, and Veillonella.

Broader analysis of community composition revealed striking differences in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial distribution between oxygen conditions. Under anaerobic conditions, Gram-positive taxa (including Streptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Parvimonas and Gemella) comprised 32% of total read abundance in both anaerobic biofilm and planktonic plaque communities, while Gram-negative taxa (Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Haemophilus, and Veillonella) represented 42% (Fig. S5A).

Conversely, under 5% CO2 conditions, Gram-negative taxa (Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Veilonella) represented less than 5% of the communities (Fig. S5B). Planktonic cells from both culture conditions exhibited similar oxygen-dependent patterns (Fig. S6). Additional analysis of biological variability (Fig. S7) and taxon-specific abundance patterns across samples (Fig. S8) further support these LEfSe-derived trends.

Notably, neither the 5% CO2 nor anaerobic microbial populations contained many taxa reported to produce AHLs, with P. gingivalis being the primary exception52. Most identified microbes have been reported to produce alternative signaling molecules such as AI-2 and/or AIPs36,46,47,49,99,100,101. This observation suggests that the observed differences in AHL levels between oxygen conditions may result from oxygen gradient effect102,103,104,105 on AHL production rather than changes in AHL-producing species abundance. This interpretation aligns with a previous report showing that oxygen availability can reduce AHL production in species such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, thereby affecting signal concentration and effectiveness106.

AHL signal disruption by lactonases increased the abundance of commensals and early colonizers in supragingival plaque community

To examine the importance of AHL signaling in microbial population structure, we used quorum quenching (QQ) to disrupt AHL signaling and analyzed community changes through 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We employed two lactonases with different substrate specificities: GcL (broad spectrum AHL degrading enzyme69) and SsoPox (preferentially degrades long-chain AHLs68).

Biofilm and planktonic communities under 5% CO2 showed markedly different microbial compositions regardless of lactonase treatment, as demonstrated by distinct clustering patterns in PCoA analysis (Fig. S7A). Certain core taxa were consistently observed across all samples and treatments, including Streptococcus, member of the order Lactobacillales, and Actinomyces – all of which are Gram-positive commensals and early colonizers of oral biofilms107,108. Notably, Abiotrophia was exclusively detected in the planktonic communities and was absent from biofilm communities across all treatments (Fig. 3A and S8A).

Lactonase treatments produced subtle but measurable alterations in the composition of the planktonic microbial communities under 5% CO2 conditions. Key taxa showed varying abundance levels between treatments: Streptococcus increased from 51.5% (control 5A8) to 53.7% (GcL) and 63.3% (SsoPox). Other taxa also showed changes in abundance levels, such as Lactobacillales (23.0% in the control 5A8, 24.0% in GcL and 21.8% in SsoPox); Actinomyces (7.2% in the control 5A8, 9.7% in GcL and 6.5% in SsoPox); Abiotrophia (11.5% in the control 5A8, 8.5% in GcL and 9.3% in SsoPox).(Fig. 3A and S8A). Individual lactonase treatments of planktonic communities did not produce statistically robust differences compared to control (GcL vs. 5A8: AMOVA: p = 0.371; ANOSIM: R = 0.255; p = 0.007*; SsoPox vs. 5A8: AMOVA: p = 0.143; ANOSIM: R = 0.191, p = 0.081). However, when analyzed collectively, lactonase-induced population changes were statistically significant (AMOVA: p = 0.047*; ANOSIM: R = 0.305; p = 0.003*; Tables S1 and S2). Alpha diversity analysis revealed that SsoPox lactonase treatment significantly reduced community diversity compared to control (t-test: p = 0.013) and GcL lactonase (t-test: p = 0.031) (Table S3, Fig. 3B, C).

A Average relative abundance of the bacteria taxa at the genus level. “Others” represent taxa comprising less than 5% of the total relative abundance per sample. B Alpha diversity (Shannon index) of the biofilm community colored by treatment (gray: SsoPox 5A8 (control); blue: SsoPox; pink: GcL). C Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances of the plaque biofilm community. D Alpha diversity (Shannon index) of the planktonic community colored by treatment (gray: SsoPox 5A8 (control); blue: SsoPox; pink: GcL). Differences in the alpha diversity metrics by treatments were tested for by using a student’s t-test, and significance values are indicated as ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05. E Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances of the planktonic dental plaque community.

AHL signal disruption had substantially more significant effects on biofilm microbial population compared to planktonic communities under 5% CO2. Both lactonase treatments significantly altered biofilm community composition compared to control (AMOVA: p = 0.002*, ANOSIM: R = 1, p = 0.002* (GcL); AMOVA: p = 0.002*, ANOSIM: R = 0.733, p = 0.002* (SsoPox); Table S1 and S2).

At the genus level, treatment with GcL significantly increased the average relative abundance of Lactobacillales (from ~17.0% to ~21.6%) and Actinomyces (from~11.2% to ~12.1%) compared to control (Wilcox test, p < 0.01). SsoPox treatment also produced significant community changes, increasing Lactobacillales (~18.9%) and Streptococcus (~54.7%) while decreasing Actinomyces (~9.6%) relative to control (Wilcox test, p < 0.01; Fig. S9A). Collectively, both lactonase treatments increased the total relative abundance of commensal and early colonizer Gram-positive taxa (Lactobacillales, Actinomyces, and Streptococcus) by approximately 6%, from ~77.2% in control to ~83% in treated samples. Alpha diversity (Shannon index) was significantly reduced by both lactonase treatments compared to control (GcL: t-test p = 0.013; Ssopox: t-test p = 0.00083; Table S3, Fig. 3B, C).

Community composition (beta diversity) showed distinct clustering patterns between treatments in PCoA analysis based on Bray-Curtis distance for both biofilm and planktonic communities. In biofilm communities, GcL and SsoPox treatments formed separate clusters, both distinct from the control and from each other. In planktonic communities, GcL-treated samples clustered near control, while SsoPox-treated samples formed a distant, separate cluster (Fig. 3D, E). These differences are statistically significant for both community types (biofilm: AMOVA: p < 0.001*, ANOSIM: R = 0.83, p < 0.001*; planktonic: AMOVA: p = 0.018, ANOSIM: R = 0.51, p = 0.01*; Table S1 and S2). The stronger effect on biofilm communities (ANOSIM R = 0.83) compared to planktonic (ANOSIM R = 0.51) highlights the particular importance of AHL signaling in sessile communities.

Comparing the two lactonase treatments revealed substrate preference specific effects. In biofilm communities, GcL treatment produced higher relative abundances of Actinomyces (12.1% vs. 9.6%) and Lactobacillales (21.6% vs. 18.9%) compared to SsoPox treatment, while SsoPox treatment resulted in higher Streptococcus abundance (54.7% vs. 49.6%) (Fig. S9A). Interestingly, these differences were not observed in planktonic communities (Fig. S9B), despite significant beta diversity differences between treatments (AMOVA: p = 0.018*; ANOSIM: R = 0.515, p = 0.01*, Table S1 and S2). The differential effects of GcL and SsoPox treatments may reflect their distinct AHL degradation preference68,69.

The observation that both lactonases mostly affected Gram-positive bacteria (Lactobacillales, Actinomyces, and Streptococcus) – which generally do not use AHL-mediated QS – suggests indirect effects. While some Gram-positive bacteria can produce4 and respond to AHLs109, our analysis revealed no notable changes in other minor taxa that could account for major shifts observed. Minor taxa comprised only approximately 4.1% of the GcL-treated community and 8% of the SsoPox-treated community. AHL disruption could alter the abundance and/or metabolism of AHL-sensing bacteria, which subsequently influences other community members. Alternatively, these enzymes could, in addition to their high AHL-degrading activity, affect the Gram-positive bacteria present in the community directly, through yet unidentified mechanisms.

Exogenous AHLs increased the abundance of late colonizers in anaerobic cultures of supragingival plaque community

Since no endogenous AHLs were detected under anaerobic conditions, we investigated whether exogenous AHL addition could influence community composition in these oxygen-limited environments. We treated anaerobic supragingival plaque communities with two different AHLs – C6-HSL and C12-HSL- and analyzed their effects on both planktonic and biofilm populations (Fig. 4A and S7B).

Similar to our observations under 5% CO2 conditions, both biofilm and planktonic communities maintained distinct microbial compositions under anaerobic conditions regardless of AHL treatment (Fig. S7B). AHL treatments did not significantly alter alpha diversity in either biofilm or planktonic anaerobic samples (Fig. 4B, C), suggesting that overall community complexity remained stable despite compositional changes.

A Average relative abundance of the bacteria taxa at the genus level. “Others” represent taxa comprising less than 5% of the total relative abundance per sample. B Alpha diversity (Shannon index) colored by treatment (purple: DMSO (control); orange: C6-HSL, green: C12-HSL). Differences in the alpha diversity metrics by treatments were tested for by using a Student’s t-test, and significance values are indicated as - ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05. C Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances of the biofilm dental plaque communities. D Alpha diversity (Shannon index) of the planktonic community colored by treatment (purple: DMSO (control); orange: C6-HSL; green: C12-HSL). Differences in the alpha diversity metrics by treatments were tested for by using a Student’s t-test, and significance values are indicated as - ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05. E Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distances of the planktonic dental plaque community.

Beta diversity analysis revealed that AHL addition significantly altered the biofilm community structure (AMOVA: p < 0.001*; ANOSIM: R = 0.54, p < 0.001*) but did not significantly affect the planktonic populations (AMOVA: p = 0.126; ANOSIM: p = 0.071) (Fig. 4D, E; Tables S4 and S5). This pattern mirrors the greater responsiveness of biofilm communities observed in the lactonase experiments, reinforcing the importance of AHL signaling in sessile communities.

A notable finding was the complete absence of Haemophilus in AHL-treated samples, while this commensal Gram-negative bacterium comprised ~5.3% of control biofilms (Fig. 4A and S8B). Haemophilus is known for its potential positive immunomodulatory effects110,111, making its elimination under AHL treatment potentially significant for oral health.

The two AHL molecules produced distinct effects on anaerobic biofilm composition. C12-HSL treatment decreased the relative abundance of Fusobacterium (from ~16.5% in control to ~16.0%) while increasing Porphyromonas abundance (from ~7.0% to ~7.7%) (Wilcox test: p = 0.0043) (Fig. S9C). C6-HSL treatment resulted in significant increase in both Porphyromonas (from ~7.0% in control to~7.6%) and Veillonella (from 8.5% in control to ~8.8%) (Wilcox test: p = 0.015, Fig. S9C). These changes, while numerically modest, represent statistically significant shifts in key bacterial populations associated with periodontal pathogenesis.

In contrast to the statistically significant changes observed on biofilms, planktonic communities showed minimal response to AHL treatment. The only significant change observed was an increase in Streptococcus abundance following C12-HSL treatment (~9.1%) compared to C6-HSL (~8.7%) and control treatment (~8.6%) (Wilcox test: p = 0.026, Fig. S9D). No other significant taxonomic differences were detected between control and AHL-treated anaerobic planktonic cultures.

The observed changes suggest that anaerobic supragingival plaque communities remain responsive to AHL signals despite not producing detectable levels of these molecules. The increase in Porphyromonas and Veillonella, both late colonizers associated with periodontal disease, suggest that AHL signaling may promote the establishment of pathogenic communities in oxygen-limited environments. The differential effects of C6-HSL and C12-HSL indicate that the specific chemical structure of AHL molecules determines their biological impact on communities, with each promoting distinct taxonomic shifts. The preferential effects on biofilm versus planktonic communities further emphasize the importance of AHL signaling in sessile oral biofilm development. This finding suggests that AHL signals produced in more aerobic regions of dental plaque may diffuse to anaerobic zones and influence community assembly, potentially contributing to the transition from healthy commensal communities to pathogenic late colonizer-dominated biofilms characteristic of periodontal disease. Both AHLs112, and oxygen113 diffuse from the periphery of a biofilm to its center. However, diffusing oxygen is rapidly consumed by the aerobic bacteria at the periphery leading to anoxic conditions in the center of the biofilm113.

Lactonase-induced changes on in vitro biofilms of supragingival plaque community alter its phenotypic and functional traits

To assess the physiological relevance of lactonase-induced community composition changes, we investigated their effects on key functional characteristics of supragingival biofilms grown under 5% CO2 conditions.

Lactonase treatments differentially affected the biofilm-forming capacity of supragingival plaque communities (Fig. 5A). SsoPox treatment significantly reduced biofilm biomass by ~57.3% compared to control (~0.93 mg vs. ~2.18 mg; t-test: p = 0.0008). In contrast, GcL treatment showed a non-significant trend toward increased biomass (~2.78 mg vs ~2.18 mg, representing a ~27.5% increase; t-test: p = 0.08).

Biofilms of supragingival plaque community grown in 5% CO2 atmosphere in the presence of indicated lactonases [5A8 (inactive lactonase), SsoPox, and GcL; 200 μg/mL] were either A heat dried in a SpeedVac or B resuspended in peptone-buffered water and incubated with 0.2% sucrose under anaerobic conditions for 4 h for lactate production. The biofilm cells were subsequently removed by centrifugation, and lactate was quantified in the cell-free supernatants using Amplite® Colorimetric L-Lactate Assay Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. A The total mass of the dried biofilm per lactonase treatment is shown. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of dry weights of 6 biological replicates of plaque biofilms, shown as individual data points. B The amounts of lactate produced per unit OD600nm of supragingival plaque biofilms grown with indicated lactonases (absolute amounts shown in Fig. S10) are normalized to the control (5A8) and represented as % of control. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of 6 biological replicates of plaque biofilm incubated with sucrose. As each biological replicate was further assayed twice for lactate measurement, each data point represents the mean of two technical replicates. The annotated number at the inside-bottom of each bar represents the mean value. Statistical significance of all treatments compared to the control (5A8) was calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-tests with Welch’s correction and significance values are indicated as - ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05.

We also evaluated the ability of lactonase-pretreated biofilms to ferment D-sucrose to L-lactate under anaerobic conditions (Fig. 5B and S10). This fermentation assay specifically tested whether community changes affected cariogenic potential, as lactate production from sucrose is a key mechanism in tooth decay. Both lactonase treatments significantly enhanced lactate production compared to controls. SsoPox-pretreated biofilms produced 1.27 mM lactate (a 33.6% increase over the 0.95 mM control; t-test: p = 0.01), while GcL-pretreated biofilms showed an even more pronounced effect, producing 1.84 mM lactate (a 92.5% increase; t-test: p = 0.0002). These results indicate that lactonase-induced changes enhanced the fermentative capacity of the community.

To comprehensively assess functional changes, we measured the ability of lactonase-pretreated biofilms to utilize various carbon sources using Biolog EcoPlates (Fig. 6). This analysis revealed lactonase-specific alterations in metabolic capacity.

Biofilms of supragingival plaque community grown in 5% CO2 atmosphere in the presence of indicated lactonases [5A8 (inactive lactonase), SsoPox and GcL; 200 μg/mL] were washed, resuspended in peptone-buffered water at an OD600nm of 0.2, and incubated in Biolog EcoPlates under 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C for 24–48 h. The time course absorbance was recorded (OD590 and OD750) and the Area-Under-the-Curve (AbsAUC) or endpoint values (OD590-750) determined, representing metabolic utilization of carbon sources, as explained in the Methods section. The mean AbsAUC values of 3 replicates were normalized to the control (5A8) and represented as % carbon source utilization compared to control (5A8). Differences were observed for utilization of Tween-20 [A 5A8 vs Sso; C 5A8 vs GcL] and Tween-80 [B 5A8 vs Sso; D 5A8 vs GcL] by the plaque biofilms. SsoPox W263I (Sso) treated plaque biofilms (2 replicates) metabolized N-acetyl-D-Glucosamine (NAG) while 5A8 treated plaque biofilms (3 replicates) did not, as represented by mean and standard deviation of endpoint (OD570-750) reads at 24 h (E) and 48 h (F). One biofilm replicate (out of 3) grown with SsoPox that failed to metabolize NAG was deemed an outlier and excluded from analysis. The annotated number at the inside-bottom of each bar represents the mean value. Statistical significance of all treatments compared to the control (5A8) was calculated using unpaired two-tailed t-tests and significance values are indicated as - ***p < 0.0005, **p < 0.005 and *p < 0.05.

Lactonase treatments significantly altered the utilization of three specific substrates - Tween-20, Tween 80 and N-acetyl-D-Glucosamine (NAG) – while leaving other tested carbon sources unaffected. The two lactonases produced opposite effects on Tween utilization: SsoPox treatment reduced the community’s ability to grow on Tween-20 by 6.3% (Fig. 6A; t-test: p = 0.0018) and Tween-80 by 17% (Fig. 6B; t-test: p = 0.02), compared to control. Conversely, GcL treatment enhanced growth on Tween-20 by 10% (Fig. 6C; t-test: p = 0.039) and on Tween-80 by 15.9% (Fig. 6D; t-test: p = 0.0004), compared to control. A striking difference emerged in NAG metabolism. SsoPox-pretreated biofilms successfully metabolized NAG within 24 hours and continued this activity through 48 hours (Fig. 6E, F), while control biofilms showed no detectable NAG utilization. This enhanced NAG metabolism capacity was not observed with GcL treatment.

These findings show that lactonase-induced changes in supragingival plaque community composition produce substantial alterations in the biofilm’s functional phenotypic characteristics. The differential effects between SsoPox and GcL treatments align with their distinct impacts on community structure (Fig. 3 and S9), supporting the hypothesis that their different AHL preference may drive specific community reorganization patterns. The magnitude of functional changes, particularly the near-doubling of lactate production with GcL treatment and the acquisition of NAG metabolism with SsoPox, illustrates how relatively modest shifts in community composition can dramatically alter collective metabolic capabilities. This relationship between community structure and function has important implications for understanding how QS disruption might influence oral health outcomes, as these metabolic changes could affect both cariogenic potential and biofilm establishment dynamics.

Discussion

The oral microbiome comprises 11 core genera consistently found across samples, with several present at low abundance levels (<2%)102. Supragingival dental plaque has a well-characterized microbial population structure94,95,96,103,107,108, beginning with pioneer and early colonizers (primarily Streptococci, Lactobacillales and Actinomyces) whose abundance is an indicator of a healthy oral microbiota. Subsequent colonizers include Capnocytophaga, Eikenella, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Campylobacter, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Treponema denticola - some of which are well documented periodontal pathogens. Most of these taxa are not known to produce AHLs (with the exception of P. gingivalis52) but have been reported to produce alternative signaling molecules such as AI-2 and/or AIPs36,46,47,49,109,110,111.

The roles of AHL signaling in oral communities have remained elusive, with the presence of AHLs itself being contested52. Previous studies using Escherichia coli, Chromobacterium violaceum and Vibrio harveyi biosensors failed to detect AHLs in anaerobic axenic cultures of key Gram-negative pathogens36,46. Our study demonstrates AHLs detection in supragingival-origin plaque community cultured under 5% CO2 conditions using both HPLC-MS and a biosensor system, while these signals remain undetectable under anaerobic conditions. This finding aligns with observations in environmental biofilms where AHL concentration gradient coincide with oxygen gradients92. Anaerobic conditions may down-regulate QS systems and AHL production, as documented in Pseudomonas aeruginosa93. This relationship between oxygen levels and AHL production is particularly relevant for understanding oral biofilms, where oxygen concentrations vary during growth and within sessile communities84,85,89,90,104,105. Consequently, AHLs functions may differ based on spatial location within the plaque.

The significance of AHL signaling in oral communities is further demonstrated by the differential effects of exogenous AHLs and lactonase-mediated quorum-quenching (QQ) under varying oxygen conditions. Under 5% CO2, where AHLs are detectable, signal disruption via QQ lactonases significantly altered microbial composition and diversity of supragingival plaque biofilm communities. Interestingly, despite undetectable AHL levels under anaerobic conditions, these communities remained responsive to exogenous AHLs, suggesting operational signal reception systems. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that AHL supplementation can increase the abundance of periodontal pathogens such as Fusobacterium and Porphyromonas50. In our study, both C6-HSL and C12-HSL increased the relative abundance of Porphyromonas, providing strong evidence that AHL signaling plays a critical role in plaque community maintenance under both anaerobic and more aerobic conditions.

Our work reveals that AHL signaling specifically affects critical microbes for plaque establishment and oral health. Lactonase treatments increased the abundance of commensals and early colonizers (e.g., Lactobacillales, Streptococcus, Actinomyces), without significantly affecting known AHLs producers or detectors. This aligns with prior research showing lactonases can influence Gram-positive bacteria114,115,116, suggesting broader effects beyond AHL-mediated QS disruption, direct or indirect. It also echoes earlier reports in which lactonases were reported to reduce cariogenic and periodontal biofilms and the abundance of periodontal pathogens under anaerobic conditions52,61,103,117. These findings suggest that AHL disruption favors growth of bacterial taxa associated with healthy oral microbiota. Importantly, we found that community population structure changes depended on the lactonase used. Because we used two lactonases with distinct AHL substrate preference, it suggests that community structure could be manipulated with different AHL signals quenchers.

Diverse AHL signals have been detected in oral biofilms52,61,117, and our exogenous addition experiments highlight their importance. In anaerobic cultures, both C6-HSL and C12-HSL increased Porphyromonas abundance. C6-HSL increased Veillonella abundance, while C12-HSL decreased Fusobacterium levels. In addition, AHL treatments eliminated Haemophilus, a commensal Gram-negative bacterium with potential immunomodulatory benefits110,111, which was present in control samples. While individual abundance appeared modest, their cumulative effect significantly altered community, potentially reflecting collective changes in minor taxa. Overall, AHL presence favored late-colonizing periodontal pathogens in dental plaque communities, with community changes depending on the chemical structure of the added AHLs.

Our findings suggest an intriguing possibility: although anaerobic communities do not produce detectable levels of AHLs, they remain responsive to these signals. This implies that periodontal pathogenic community emergence may depend on specific QS signaling molecules produced in more aerobic spatial locations of dental plaque, potentially diffusing to influence anaerobic colonizers. While our use of 16S V4 region sequencing captured broad community-level changes, it limited taxonomic resolution. Future metagenomic approaches may better identify AHL producers and reveal more subtle diversity patterns between treatments.

QQ lactonases also modulated the physiological characteristics of the aerobic supragingival plaque community, significantly reducing biofilm formation. This reduction could stem from increased Streptococci abundance relative to Actinomyces, altering the complex molecular interactions governing the co-aggregation and dental attachment of Streptococci and Actinomyces in plaque biofilm formation118,119. Lactonase treatment also altered the community’s ability to metabolize N-acetyl-D-Glucosamine (NAG). Some oral Streptococci species, like Streptococcus mutans, can metabolize NAG120 to ammonia and increase acid tolerance. It is likely that SsoPox treatment increased the abundance of NAG-metabolizing species of Streptococci in the plaque biofilms.

Additionally, lactonase-treated plaque biofilms exhibited enhanced fermentation capability, correlating with increased abundance of Lactobacilli - oral acidogenic bacteria capable of fermenting sucrose to lactate121,122. Sucrose availability in oral biofilms typically increases Firmicutes (including Lactobacilli) abundance123,124. While some Streptococci125 and Actinomyces126 ferment sucrose to lactate, others are alkali-producers, and disruption of this balance in oral biofilms can lead to cariogenic diseases123,125. Although increased lactate production can damage oral health through acid-mediated decay and is strongly regulated in oral biofilms127, it is noteworthy that lactonase-induced fermentation remained within ranges typical of periodontal biofilms (0.2 – 2 mM lactate produced in a 3 h fermentation run)50, substantially below levels produced by cariogenic biofilms (4.2 – 9.4 mM)50.

Taken together, our observations indicate that lactonase-mediated changes in population structure significantly alter the functional phenotypes and biological activities of supragingival-original plaque community biofilms. These results underscore the importance of AHL-signaling in oral biofilm development and maintenance. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms by which AHL-based QS and lactonases finely modulate community structure and function.

Methods

Reagents

Chemicals, including antibiotics were of reagent grade or superior and were sourced from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA) or Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). N-butyryl-L-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL; item code #10007898), N-hexanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C6-HSL; #10007896), and N-dodecanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C12-HSL; #10011203) were purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI) and dissolved in 100% DMSO just before use. Biolog EcoPlates™ (#1506) were purchased from Biolog Inc. (Hayworth, CA). Amplite™ Colorimetric L-Lactate Assay Kit (#13815) was procured from AAT Bioquest, Inc (Pleasanton, CA). Peptone Buffered Water (PBW) used in some experiments had the following composition – Bacto-Peptone 10 g/L, NaCl 5 g/L, KH2PO4 1.5 g/L, Na2HPO4 3.5 g/L, pH 7.0.

Lactonase production and purification

The E. coli strain BL21 Star™ (DE3) was used to produce the following lactonases – (i) An inactive SsoPox mutant 5A8 (hereafter referred to as 5A8)128, (ii) SsoPox W263I mutant (hereafter referred to as SsoPox)68, and (iii) wild-type GcL with an N-terminal Strep-Tag II™ (hereafter referred to as GcL)69. Purification was performed as previously described69,81. All lactonase preparations used in this study were made in buffer (PTE) composed of 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM CoCl2, sterilized by passing through a 0.2 μm filter, and stored at 4°C until use. The inactive lactonase 5A8 is used as a control in all experiments that use active lactonases SsoPox and GcL, to account for potential utilization of these enzymes as nutrients by the microbial community on which they are being tested. Since 5A8 is inactive and only differs from SsoPox by a few mutations, any observed changes in the microbial community and its phenotypic functions between this 5A8 control and treatments can be attributed solely to the AHL degradation activity of the active lactonases.

In vitro culturing of an oral microbial community derived from human supragingival plaque

We used a previously described representative supragingival plaque community (dental plaque)82,83 obtained from healthy human volunteers, as a model system to assess production of AHLs and their role in community composition. For the experiments described here, frozen 10% glycerol stock of dental plaque community was used to inoculate a modified saliva-supplemented SHI medium, that is composed of 25% SHI medium129 and 75% of sterile human saliva, and incubated overnight (~18 h) at 37°C under 5% CO2 (we sometimes referred to 5% CO2 as “aerobic” for simplicity) or anaerobically (10% H2, 10% CO2 and 80% N2). Overnight cultures were then diluted into fresh modified SHI medium at a final OD600nm = 0.1 and incubated at 37 °C in saliva-coated 6-well polystyrene culture plates (Corning, NY) for 18 h, as previously described83. Cultures grown under 5% CO2 atmosphere contained 200 μg/mL lactonases - 5A8 (inactive lactonase; control), SsoPox or GcL. Anaerobic cultures contained DMSO (0.1%; control), 10 μM C6-HSL or 10 μM C12-HSL. All treatments had 6 biological replicates.

Collection and sterilization of saliva was done as previously described130. Briefly, whole saliva was collected by expectoration into tubes on ice followed by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 4 °C at 4000 x g (Beckman SX4750 rotor) to remove large debris and bacterial aggregates. The supernatants were then decanted, and the planktonic bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 x g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. These supernatants were next collected and sterilized by passing through a 0.2 μ filter. Sterilized collections were pooled from at least three healthy volunteers. All protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards from the University of Minnesota (STUDY00016289). Sterile saliva was mixed with SHI medium at 75:25 proportions of saliva to SHI medium.

Detection of AHLs using biosensors

The biosensor plasmid pJBA13291 contains a gfp(ASV) reporter gene under the transcriptional regulation of an AHL-responsive luxI promoter. pJBA132 was transformed into E. coli strain JM109 (Promega; Madison, WI). This biosensor can detect and quantify C6 - C12 AHLs in the range of 10 nM–1 µM91. A titration was performed with pure C6-HSL, the AHL molecule detected in culture samples using HPLC-MS (Fig. S3). JM109 harboring pJBA132 was routinely cultured in Miller’s Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (BD Difco, 244610) or LB-agar plates (BD Difco, #244510), supplemented with 10 μg/mL tetracycline. An overnight culture of the biosensor strain derived from a single colony was diluted 1:100 into fresh LB broth supplemented with 10 μg/mL tetracycline and grown in a shaker incubator at 37 °C and 225 rpm. At 2 hours, cultures reach an early exponential phase of growth. Cell-free culture supernatants of the supragingival-origin oral plaque community were mixed with biosensor cultures at a ratio of either 1:4 or 1:5 and dispensed at a total volume of 200 μL per well (6 replicates) in specialized 96-well microplates designed for measuring fluorescence and optical density simultaneously (Grenier Bio-OneTM #655906, non-binding opaque black 96-well microplate with μClear™ Film Bottom). For the blank control, sterile, uninoculated modified SHI media was mixed with biosensor cultures at a similar dilution. The microplates were covered with a lid and incubated in a microplate shaker incubator (Titramax 1000 from Heidolph instruments) at 37 °C and 300 rpm for 3 hours. GFP fluorescence (Excitation: 485 nm. Emission: 528 nm; Gain 75) and OD600nm were measured in a BioTek Synergy HTX microplate spectrophotometer. The data were represented as the ratio of arbitrary relative fluorescence units (RFUs) to the OD600nm of the biosensor culture [RFU/OD600nm]. The “blank” was regarded as the mean RFU/OD600nm of 6 replicates of “media-only” control and subtracted from the RFU/OD600mn of all other results. After the subtraction of blank values, the RFU/OD600nm was adjusted for dilution. To estimate the AHL concentrations detected by the biosensor, we used a standard curve determined with C6-HSL (Fig. S3). For the biosensor standard curve, varying concentrations (1 nM–1 mM in 1 log10 fold increments) of C6-HSL freshly prepared in DMSO (2 µL) was diluted 1:100 to excite the exponentially growing biosensor strain culture (198 µL). Data was recorded as above and represented as the mean and error of RFU/OD600nm of 6 replicates to generate the standard curve.

Liquid phase AHL extraction for LC-MS

We used a modified liquid phase extraction (LPE) protocol for AHLs adapted from Parga et al. 202361. Human saliva, culture media (75% human saliva and 25% SHI media), and cell-free culture supernatants of the supragingival-origin plaque community grown under 5% CO2 or anaerobic conditions were subjected to organic LPE. Briefly, 0.5 mL of the saliva or culture supernatant was acidified by addition of 50 µL 12.1 N hydrochloric acid, to promote stability of AHLs, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min followed by centrifugation (17,000 x g/10 min) to remove debris. The supernatant was extracted twice with two equal volumes of ethyl acetate followed by two equal volumes of dichloromethane. For each extraction, the mixture was vortexed vigorously for 2 min followed by centrifugation at 14,000 x g /1 min to separate the aqueous phase from organic phase. For ethyl acetate and dichloromethane extractions, the upper and lower organic phases were collected, respectively, and pooled into a single tube. The organic extracts were subjected to gentle drying at room temperature under a stream of nitrogen gas. This LPE protocol was validated with cell-free spent media of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 (cultured in LB media at 37 °C, 250 rpm for 24 h) and standard AHLs, and was found to be effective at extracting short chain AHLs (C4-C6). However, despite our optimization efforts, the protocol is unable to efficiently extract long-chain AHLs, such as 3-oxo C12 HSL that is produced by PA14 (data not shown). Therefore, long-chain AHLs were not detected in any samples extracted with this method.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS)

The analysis was performed by the University of Minnesota Center for Metabolomics and Proteomics. The dried extracts were reconstituted in 25 μL 50:50:0.1, LC-MS grade water: acetonitrile (ACN): formic acid (FA), vortexed for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min. Each sample was transferred to an autosampler vial, and 1 μL was injected. Prepared samples were analyzed via chromatographic separation in-line with mass spectrometry. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using the Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RS UHPLC platform fitted with a Phenomenex Gemini NX 2 × 150 mm, 5 μm, C18 column heated at 40 °C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Buffer A was water, 0.1% formic acid and buffer B was 100% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid. The samples were separated with the following gradient: 1% B 0–1 min., 100%B at 15 min, and 100% B maintained to 18 min before equilibration to 1% B. For all separations, the column was in-line with a HESI source mounted to a Q Exactive™ Quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The spray voltage was 3.4 kV in positive polarity mode, sheath gas flow was 50, auxiliary gas flow was 8, Slens RF was 50 V, probe heater was 400 °C, and the heated capillary was maintained at 320 °C. The orbitrap was set to acquire MS1 mass spectra from 70–750 m/z with a resolution of 70,000 at 200 m/z, an automatic gain control (AGC) of 1.0E6, and a max injection time of 50 ms. For MS2 tandem mass spectra a targeted inclusion list of m/z values was imported with fragmentation by higher-energy collisional dissociation, normalized collision energy of 30, a detector setting of 17.5 k resolution, AGC 2e5 ions, isolation window of 1.0 m/z, and a 200 ms maximum injection time was used. The samples were compared to an in-house fragmentation and retention time library of the N-acyl homoserine lactone molecules of interest (C4-C16 HSLs and their 3-oxo derivatives).

DNA extraction and 16S sequencing

Total microbial DNA from biofilms and planktonic cells of dental plaque cultures was extracted using DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen; Germantown, MD). After the recommended quality control procedures, the DNA was submitted for sequencing of the V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA genes at the University of Minnesota’s Genomics Center (UMGC) to capture the broad community changes between treatments. Additionally, the V4 region offers a good balance between read length and taxonomic resolution as well as providing consistent amplification across a broad range of bacteria taxa131.

Bacterial community processing

16S rRNA amplicon sequences were processed with Mothur v.1.41.1132. Forward and reverse reads were merged into contigs and filtered with defined criteria as previously described133. Briefly, any removed sequences were based upon ambiguous bases longer than 300 bp and homopolymers ≥ 8 nucloetides. The processed sequences were then aligned against the SILVA database v.132.4, subject to a 2% pre-cluster134. UCHIME was used to remove chimera within sequences135. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were classified at 97% sequence similarity using the average-neighbor algorithm and against the Ribosomal Database Project v.18136. The collapsed taxon table was converted to relative abundance using the phyloseq package in RStudio. Alpha diversity metrics (Good’s coverage, Sob, Shannon, Chao, ACE, and Simpson) were calculated using the normalized OTU table, and Bray-Curtis similarities matrices were used for beta diversity comparisons in Mothur v.1.41.1132.

Biofilm Weight Measurement

An overnight culture (37 °C, 5% CO2) of supragingival-origin plaque community in modified SHI media was inoculated into fresh modified SHI media at a working OD600nm of 0.15. The inoculated media was split into three 50 mL Falcon™ centrifuge tubes (Corning) and lactonases 5A8, SsoPox or GcL (200 μg/mL final) were added to a final volume of 25 mL. The inoculated media and lactonase mix were then dispensed into the wells of three sterile UV-treated 6-well Clear Flat Bottom TC-treated Cell Culture Plates (Corning) – 4 mL per well, for a total of 6 replicates, per lactonase treatment. These plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere for 22 h. The biofilms produced after 22 h were susceptible to physical shear and dislodgement and were handled with extreme caution (the reason why we did not opt for more traditional methods of biofilm quantitation such as crystal violet staining). The media supernatant with the planktonic cells was aspirated carefully. The biofilms were washed gently twice with 2 mL Peptone Buffered Water (PBW) to remove any adherent planktonic cells. The biofilms were then vigorously dislodged from the wells using 1 mL PBW and collected in a 15 mL Falcon™ centrifuge tubes (Corning). This process was repeated 4 times to ensure dislodgement and collection of all remaining biofilm. The harvested biofilm was centrifuged at 6000 x g for 10 min. The biofilm pellets were resuspended into 1 mL PBW, transferred to 1.7 mL Eppendorf microcentrifuge tubes, washed three times with fresh 1 mL PBW to remove residual culture media (centrifuged at 6000 x g for 5 min in between washes), and finally resuspended evenly into 1 mL PBW. 200 μL of the biofilm suspensions were saved separately for later sucrose fermentation assays. The remaining biofilm suspensions were centrifuged at 6000 x g for 10 min, and the pellets were dried at 45 °C for 30 minutes using a SpeedVac (Eppendorf Vacufuge® Plus). The dry weights of the biofilms were subsequently determined using an analytical balance (Sartorius Practum®) for biomass quantitation.

Sucrose fermentation, lactate production and quantification assays

150 μL of the saved biofilm suspensions from the previous section were diluted with 300 μL fresh PBW with sucrose added to a final concentration of 0.2% w/v. These mixtures were incubated in an anaerobic chamber at 37 °C for 4 h followed by centrifugation (16,000 × g /10 min) to pellet the biofilm. 200 μL of the cell-free supernatants were carefully transferred to fresh 1.7 mL microcentrifuge tubes and were used for quantitation of L-lactate using the Amplite™ Colorimetric L-Lactate Assay Kit (AAT Bioquest), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were set up in duplicates for each supernatant and in triplicates for the lactate standards (0–1 mM) in 96-well flat-bottom microplates (Sarstedt; # 82.1581.001). Absorbance data (OD575nm/OD605nm) were collected kinetically using a BioTek Synergy HTX microplate spectrophotometer at 1 min intervals for 30 min at room temperature to determine possible absorbance saturation. The 30 min endpoint absorbance (OD575nm/OD605nm) was used for standard curve determination and all subsequent quantitation of L-lactate, as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The remaining biofilm suspensions from the previous section were diluted to 10% using fresh PBW and used for determining OD600nm values using a BioTek Synergy HTX microplate spectrophotometer. The final lactate quantitation was multiplied by 3 to account for the dilution of biofilm into PBW (150 μL biofilm suspension + 300 μL PBW) and then normalized to per unit OD600nm value of the biofilm suspension.

Phenotypic Assays with Biolog EcoPlates™

EcoPlates™ from Biolog (https://www.biolog.com/products/community-analysis-microplates/ecoplate/) were used to establish community-level physiological profiling of microbial communities. Each 96-well EcoPlate contains 31 carbon-source assays in triplicate and can be used to observe the metabolization of carbon sources by bacteria. Each well is supplemented with a proprietary tetrazolium redox dye that is reduced to purple-colored formazan products (λabs 590 nm) due to NADH production (a sensitive indicator of respiration) by metabolically active cells137,138. This colorimetric reaction was monitored and recorded by a spectrophotometer at specific time intervals to generate a kinetic response curve mirroring microbial metabolization of the carbon sources that can be further quantitated into parameters such as lag, slope, and area under the curve139. Supragingival-origin plaque biofilms were cultured with lactonases, washed and harvested similarly as described in the previous “Biofilm Weight Measurement” section. The biofilm suspensions were diluted to a final OD600nm of 0.2 in 12 mL PBW, and 100 μL was dispensed into each of the 96 wells of the EcoPlates. Separate EcoPlates were used for biofilms grown with different lactonases. The EcoPlates were sealed under 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C (after 2 h of gas-exchange) with gas-impermeable membranes (Applied Biosystems, #4360954) and then incubated in a BioTek Synergy HTX or BioTek Epoch 2 microplate spectrophotometer at 37 °C for 24 h. OD590nm (absorbance of formazan, as discussed earlier) and OD750nm (for cell turbidity) were measured for each well every 10 min. The difference in absorbance [OD590nm – OD750nm] values plotted against the time of incubation corresponds to the carbon-source metabolization. The area-under-the-curve (AbsAUC) of the “difference in absorbance” plot against incubation time, calculated with the BioTek Gen5 (v3.14) software corresponds to the total carbon metabolization over 24 h. The EcoPlates were then transferred to a 37 °C incubator for another 24 h, to enable measurement of 48-h endpoint read of (OD590nm – OD750nm) values. As we have only 2 BioTek Plate readers at our disposal, each experiment was limited to 2 EcoPlates (and by extension, 2 lactonase treatments). Therefore, 5A8 vs SsoPox and 5A8 vs GcL experiments were done on two subsequent days. For N-acetyl-D-Glucosamine, metabolic activity was only observed in biofilms grown with SsoPox and therefore, endpoint reads of (OD590nm – OD750nm) at 24 h and 48 h were used for quantitative comparison. For the rest of the carbon sources metabolized by the plaque biofilm, metabolic activity was observed in all treatments, and AbsAUC over 24 h was used for quantitative comparisons.

Graphing and statistical analysis

Beta diversity comparisons, principal-coordinate and Lefse analyses were performed using Mothur v1.41.1132. Differences in beta diversity between samples were analyzed using analysis of similarity (ANOSIM)140 and analysis of molecular variances (ANOVA)141. LEfSe employs the non-parametric factorial Kruskal-Wallis sum-rank test for classes and the pairwise Wilcoxon-test for comparing subclasses across different classes, taking biological variability into its consideration during its analysis process98. Student’s t-test142 was performed in R to calculate the differences in alpha diversity metrics, and Wilcoxon test142 was used for the differences in OTU-level abundances between samples. Ggplot2 package in R was used to visualize the taxa abundances and diversities in bacterial communities between the samples143. The statistical analyses incorporate biological variation with detailed quantitative data on the relative abundance for each taxon across all experimental replicates. Krona pie chart tool in Galaxy (https://github.com/marbl/Krona/wiki) was also used for visualization of Mothur results. The results from the biosensor experiments were processed, analyzed, and graphed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 8. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests with or without Welch’s correction were used for determining statistical significance and calculated using GraphPad Prism. The HPLC-MS data was visualized, processed and graphed with Skyline v24.1 (https://skyline.ms/project/home/software/Skyline/begin.view).

Language editing

Large Language Model Claude Sonnet 4.0 (Anthropic, USA) was used to improve the clarity of some portions of the manuscript.

Data availability

Raw 16S sequencing reads were deposited to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA1083492 under the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1083492. All the raw experimental data and analysis for this study are available at: https://osf.io/927gt/?view_only=31415fd9d658466ab7f54b2beeebb232.

Code availability

The code used to process and analyze the data in this study is available at: https://github.com/maibeauclaire/dental_plaque_microbiome and archived at Zenodo under https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15758214. The code is shared under the MIT license.

References

Miller, M. B. & Bassler, B. L. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 165–199 (2001).

Williams, P. Quorum sensing, communication and cross-kingdom signalling in the bacterial world. Microbiology 153, 3923–3938 (2007).

Papenfort, K. & Bassler, B. L. Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.14, 576–588 (2016).

Biswa, P. & Doble, M. Production of acylated homoserine lactone by gram-positive bacteria isolated from marine water. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 343, 34–41 (2013).

Zhang, G. et al. Acyl homoserine lactone-based quorum sensing in a methanogenic archaeon. ISME J.6, 1336–1344 (2012).

Pereira, C. S., Thompson, J. A. & Xavier, K. B. AI-2-mediated signalling in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 156–181 (2013).

Nichols, J. D. et al. Temperature, not LuxS, mediates AI-2 formation in hydrothermal habitats. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 173–181 (2009).

Surette, M. G., Miller, M. B. & Bassler, B. L. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, and Vibrio harveyi: a new family of genes responsible for autoinducer production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1639–1644 (1999).

Zhao, L. et al. Staphylococcus aureus AI-2 quorum sensing associates with the KdpDE two-component system to regulate capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 78, 3506–3515 (2010).

Chen, X. et al. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415, 545–549 (2002).

Monnet, V., Juillard, V. & Gardan, R. Peptide conversations in Gram-positive bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 42, 339–351 (2016).

Le, K. Y. & Otto, M. Quorum-sensing regulation in staphylococci-an overview. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1174 (2015).

Slamti, L. & Lereclus, D. Specificity and polymorphism of the PlcR-PapR quorum-sensing system in the Bacillus cereus group. J. Bacteriol. 187, 1182–1187 (2005).

Liu, H. et al. Quorum sensing coordinates brute force and stealth modes of infection in the plant pathogen Pectobacterium atrosepticum. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000093 (2008).

Mukherjee, S. & Bassler, B. L. Bacterial quorum sensing in complex and dynamically changing environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 371–382 (2019).

Sikdar, R. & Elias, M. H. Evidence for complex interplay between quorum sensing and antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0126922 (2022).

Montgomery, K. et al. Quorum sensing in extreme environments. Life 3, 131–148 (2013).

Seneviratne, C. J., Zhang, C. F. & Samaranayake, L. P. Dental plaque biofilm in oral health and disease. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 14, 87–94 (2011).

Human Microbiome Project, C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012).

Zaura, E. et al. Defining the healthy “core microbiome” of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 9, 259 (2009).

Dewhirst, F. E. et al. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5002–5017 (2010).

Willis, J. R. & Gabaldon, T. The human oral microbiome in health and disease: from sequences to ecosystems. Microorganisms 8, 308 (2020).

Perera, M. et al. Emerging role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis: a review with special reference to perio-pathogenic bacteria. J. Oral. Microbiol. 8, 32762 (2016).

Zhao, H. et al. Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 11773 (2017).

Belda-Ferre, P. et al. The oral metagenome in health and disease. ISME J. 6, 46–56 (2012).

Hajishengallis, G., Darveau, R. P. & Curtis, M. A. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 717–725 (2012).

Marsh, P. D. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv. Dent. Res. 8, 263–271 (1994).

Mohanty, R. et al. Red complex: Polymicrobial conglomerate in oral flora: A review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 8, 3480–3486 (2019).

He, X. et al. Adherence to streptococci facilitates Fusobacterium nucleatum integration into an oral microbial community. Micro. Ecol. 63, 532–542 (2012).

Kolenbrander, P. E. et al. Bacterial interactions and successions during plaque development. Periodontol. 2000 42, 47–79 (2006).

Sakanaka, A. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum metabolically integrates commensals and pathogens in oral biofilms. mSystems 7, e0017022 (2022).

Bramhachari P. V. et al. Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation by Oral Pathogenic Microbes in the Dental Plaques: Implication for Health and Disease. In: Bramhachari P. V., editor. Implication of Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation in Medicine, Agriculture and Food Industry. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. p. 129–140.

Wright P. P., Ramachandra S. S. Quorum sensing and quorum quenching with a focus on cariogenic and periodontopathic oral biofilms. Microorganisms. 10 (2022).

Cuadra-Saenz, G. et al. Autoinducer-2 influences interactions amongst pioneer colonizing streptococci in oral biofilms. Microbiology 158, 1783–1795 (2012).

McNab, R. et al. LuxS-based signaling in Streptococcus gordonii: autoinducer 2 controls carbohydrate metabolism and biofilm formation with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 185, 274–284 (2003).

Burgess, N. A. et al. LuxS-dependent quorum sensing in Porphyromonas gingivalis modulates protease and haemagglutinin activities but is not essential for virulence. Microbiology 148, 763–772 (2002).

Rickard, A. H. et al. Autoinducer 2: a concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 1446–1456 (2006).

Fong, K. P. et al. Intra- and interspecies regulation of gene expression by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans LuxS. Infect. Immun. 69, 7625–7634 (2001).

Merritt, J. et al. Mutation of luxS affects biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 71, 1972–1979 (2003).

Jang, Y. J. et al. Autoinducer 2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum as a target molecule to inhibit biofilm formation of periodontopathogens. Arch. Oral. Biol. 58, 17–27 (2013).

Jang, Y. J. et al. Differential effect of autoinducer 2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum on oral streptococci. Arch. Oral. Biol. 58, 1594–1602 (2013).

Petersen, F. C., Pecharki, D. & Scheie, A. A. Biofilm mode of growth of Streptococcus intermedius favored by a competence-stimulating signaling peptide. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6327–6331 (2004).

Senadheera, D. & Cvitkovitch, D. G. Quorum sensing and biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 631, 178–188 (2008).

Perry, J. A., Cvitkovitch, D. G. & Levesque, C. M. Cell death in Streptococcus mutans biofilms: a link between CSP and extracellular DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 299, 261–266 (2009).

Senadheera, D. et al. Inactivation of VicK affects acid production and acid survival of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6415–6424 (2009).

Frias, J., Olle, E. & Alsina, M. Periodontal pathogens produce quorum sensing signal molecules. Infect. Immun. 69, 3431–3434 (2001).

Whittaker, C. J., Klier, C. M. & Kolenbrander, P. E. Mechanisms of adhesion by oral bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50, 513–552 (1996).

Guo, L., He, X. & Shi, W. Intercellular communications in multispecies oral microbial communities. Front. Microbiol. 5, 328 (2014).

Huang, R., Li, M. & Gregory, R. L. Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm. Virulence 2, 435–444 (2011).

Muras A. et al. Short-Chain N-Acylhomoserine Lactone Quorum-sensing molecules promote periodontal pathogens in in vitro oral biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86 (2020).

Kumari, A., Pasini, P. & Daunert, S. Detection of bacterial quorum-sensing N-acyl homoserine lactones in clinical samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391, 1619–1627 (2008).

Muras, A. et al. Acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing in the oral cavity: a paradigm revisited. Sci. Rep. 10, 9800 (2020).

Chen, J. W. et al. N-acyl homoserine lactone-producing Pseudomonas putida strain T2-2 from human tongue surface. Sensors 13, 13192–13203 (2013).

Yin, W. F. et al. Long chain N-acyl homoserine lactone production by Enterobacter sp. isolated from human tongue surfaces. Sensors 12, 14307–14314 (2012).

Yin, W. F. et al. N-acyl homoserine lactone production by Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from human tongue surface. Sensors 12, 3472–3483 (2012).

Goh, S. Y. et al. Quorum sensing activity of Citrobacter amalonaticus L8A, a bacterium isolated from dental plaque. Sci. Rep. 6, 20702 (2016).

Goh, S. Y. et al. Unusual multiple production of N-acylhomoserine lactones a by Burkholderia sp. strain C10B isolated from dentine caries. Sensors 14, 8940–8949 (2014).

Wu, J., Lin, X. & Xie, H. Regulation of hemin binding proteins by a novel transcriptional activator in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 191, 115–122 (2009).

Chawla, A. et al. Community signalling between Streptococcus gordonii and Porphyromonas gingivalis is controlled by the transcriptional regulator CdhR. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 1510–1522 (2010).

Aleti G. et al. Identification of the bacterial biosynthetic gene clusters of the oral microbiome illuminates the unexplored social language of bacteria during health and disease. mBio. 10 (2019).

Parga, A. et al. The quorum quenching enzyme Aii20J modifies in vitro periodontal biofilm formation. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1118630 (2023).

Billot, R. et al. Engineering acyl-homoserine lactone-interfering enzymes toward bacterial control. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 12993–13007 (2020).

Elias, M. & Tawfik, D. S. Divergence and convergence in enzyme evolution: parallel evolution of paraoxonases from quorum-quenching lactonases. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 11–20 (2012).

Remy, B. et al. Interference in bacterial quorum sensing: a biopharmaceutical perspective. Front. Pharm. 9, 203 (2018).

Sikdar, R. & Elias, M. Quorum quenching enzymes and their effects on virulence, biofilm, and microbiomes: a review of recent advances. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 18, 1221–1233 (2020).

Elias, M. et al. Structural basis for natural lactonase and promiscuous phosphotriesterase activities. J. Mol. Biol. 379, 1017–1028 (2008).

Hiblot, J. et al. Characterisation of the organophosphate hydrolase catalytic activity of SsoPox. Sci. Rep. 2, 779 (2012).

Hiblot, J. et al. Differential active site loop conformations mediate promiscuous activities in the lactonase SsoPox. PLoS One 8, e75272 (2013).

Bergonzi, C. et al. The structural determinants accounting for the broad substrate specificity of the quorum quenching Lactonase GcL. Chembiochem 20, 1848–1855 (2019).

Liao, L. et al. An aryl-homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signal produced by a dimorphic prosthecate bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7587–7592 (2018).

Wellington, S. & Greenberg, E. P. Quorum sensing signal selectivity and the potential for interspecies cross talk. mBio 10, e00146–19 (2019).

Brameyer, S. & Heermann, R. Specificity of Signal-Binding via Non-AHL LuxR-Type Receptors. PLoS One 10, e0124093 (2015).

Grandclement, C. et al. Quorum quenching: role in nature and applied developments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 86–116 (2016).

Guendouze, A. et al. Effect of Quorum Quenching Lactonase in Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Comparison with Quorum Sensing Inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 8, 227 (2017).

Lopez-Jacome, L. E. et al. AiiM lactonase strongly reduces quorum sensing controlled virulence factors in clinical strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated From Burned Patients. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2657 (2019).

Bijtenhoorn, P. et al. A novel metagenomic short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence on Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 6, e26278 (2011).

Hraiech, S. et al. Inhaled lactonase reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing and mortality in rat pneumonia. PLoS One 9, e107125 (2014).

Stoltz, D. A. et al. Paraoxonase-2 deficiency enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing in murine tracheal epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L852–L860 (2007).

Utari, P. D. et al. PvdQ Quorum Quenching Acylase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of pulmonary infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8, 119 (2018).

Mahan, K. et al. Effects of signal disruption depends on the substrate preference of the Lactonase. Front. Microbiol. 10, 3003 (2019).

Remy, B. et al. Lactonase specificity is key to quorum quenching in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 11, 762 (2020).

Hall, J. W. et al. An intramembrane sensory circuit monitors sortase A-mediated processing of streptococcal adhesins. Sci. Signal 12, eaas9941 (2019).

Saavedra, F. M. et al. In vitro physicochemical characterization of five root canal sealers and their influence on an ex vivo oral multi-species biofilm community. Int Endod. J. 55, 772–783 (2022).

Kenney, E. B. & Ash, M. M. Jr. Oxidation reduction potential of developing plaque, periodontal pockets and gingival sulci. J. Periodontol. 40, 630–633 (1969).

Marquis, R. E. Oxygen metabolism, oxidative stress and acid-base physiology of dental plaque biofilms. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15, 198–207 (1995).

Burne, R. A. Oral streptococci products of their environment. J. Dent. Res 77, 445–452 (1998).

Kolenbrander, P. E. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev. Microbiol. 54, 413–437 (2000).

Rosier, B. T. et al. Historical and contemporary hypotheses on the development of oral diseases: are we there yet? Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4, 92 (2014).

Ahn, S. J. et al. Changes in biochemical and phenotypic properties of Streptococcus mutans during growth with aeration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2517–2527 (2009).

Ahn, S. J. & Burne, R. A. Effects of oxygen on biofilm formation and the AtlA autolysin of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6293–6302 (2007).

Andersen, J. B. et al. gfp-based N-acyl homoserine-lactone sensor systems for detection of bacterial communication. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 575–585 (2001).

Flemming, H. C. et al. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575 (2016).

Lee, K. M. et al. Anaerobiosis-induced loss of cytotoxicity is due to inactivation of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 79, 2792–2800 (2011).

de Jesus, V. C. et al. Characterization of Supragingival Plaque and Oral Swab Microbiomes in Children With Severe Early Childhood Caries. Front. Microbiol. 12, 683685 (2021).

Espinoza, J. L. et al. Supragingival Plaque Microbiome Ecology and Functional Potential in the Context of Health and Disease. mBio 9, e01631–18 (2018).

Rabe, A. et al. Impact of different oral treatments on the composition of the supragingival plaque microbiome. J. Oral. Microbiol. 14, 2138251 (2022).

Mangal, U., Kwon, J. S. & Choi, S. H. Bio-interactive zwitterionic dental biomaterials for improving biofilm resistance: characteristics and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9087 (2020).