Abstract

Rapid urbanization and dense populations in metropolitan areas increase the risk of tick-borne disease transmission. We profiled 139 RNA libraries of 1697 adult ticks belonging to Haemaphysalis longicornis, Haemaphysalis concinna, Dermacentor silvarum, Dermacentor sinicus, and Rhipicephalus sanguineus, field-collected in the Hebei region. Among 179 viral species, four human pathogens (a novel Bandavirus dabieense genotype, Orthonairovirus nairobiense, Thogotovirus thogotoense, and Xue−Cheng virus) were identified, highlighting potential emerging tick-borne disease threats. Four viruses infecting animals (Lagovirus europaeus, Ovine parvovirus, canine parvovirus, and Psittaciform Parvoviridae sp.) were discovered for the first time in ticks, suggesting the role of ticks as a potential reservoir. Hebei bunya-like virus 1, Dandong tick virus 1, and Zhejiang mosquito virus 3 were genetically closely related to mosquito-associated viruses, suggesting a potential transmission route for these viruses through both mosquitoes and ticks. The diverse tick virome in metropolitan surroundings contained potential human and animal pathogens, highlighting the need for proactive surveillance of emerging tick-borne viruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tick-borne pathogens have presented an increasing threat to human health1, and the continuous emergence of tick-borne human pathogenic viruses has caused a global public health concern2. However, these viral pathogens might be a small portion of the composition of tick-borne viruses. Investigation of tick virome is essential not only to understand the profile of tick-associated viruses, but also to identify viral pathogens for the early alert of potential emerging tick-borne diseases. Furthermore, nonpathogenic viruses might have a role in vector competence and modulate the infection outcomes of pathogenic viruses, although they do not directly infect humans and animals. Meta-transcriptomic sequencing has led to the discovery of an increasing number of unrecognized viruses and has revealed significant viral diversity within tick samples from various regions in recent years3,4,5,6,7,8, highlighting the necessity for more extensive investigation on tick viromes in different ecological regions.

Mainland China harbors a remarkable diversity of tick species and tick-borne viruses, with substantial regional variation in tick communities. Tick viromes are highly diverse7, often showing genus-specific patterns and strong associations with ecological and geographical landscapes8,9. Over the past decade, at least 11 emerging tick-borne viral diseases have been reported in China10, underscoring their growing significance as a major public health threat, with China’s rapid economic development and accelerating urbanization further exacerbating this concern. This process inevitably creates suburban environments more conducive to tick survival, through the encroachment on forested areas and farmland, as well as the protection of existing green spaces. Meanwhile, urbanization and economic development around these metropolitan areas likely increased opportunities for human-animal contact, thereby promoting the transmission of tick-borne pathogens between humans and animals11. Despite these high-risk dynamics, the viral diversity of ticks in these metropolitan surroundings remains poorly characterized.

The surroundings of the two major northern Chinese metropolises, Beijing and Tianjin, have unique geographical and ecological environment features. Therefore, conducting a tick virome survey in this region and understanding the distribution of viruses across different tick species were of particular importance for the early warning and prevention of tick-borne pathogen transmission risks. In this study, we collected ticks from the region surrounding Beijing and Tianjin metropolis, and conducted meta-transcriptomic sequencing to understand the viral composition of different tick species and the diversity of viromes, to explore undefined tick-borne viruses, and to identify potential tick-borne viral pathogens that pose a threat to humans and animals.

Results

Overview of tick virome diversity

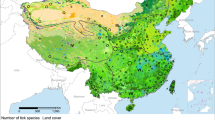

Five tick species, including Haemaphysalis longicornis, Haemaphysalis concinna, Dermacentor silvarum, Dermacentor sinicus, and Rhipicephalus sanguineus were collected in the Hebei region surrounding Beijing and Tianjin metropolises (Fig. 1). Among 1697 ticks, H. longicornis was the dominant tick species (80.91%, 1373), followed by D. silvarum (11.79%, 200), H. concinna (6.13%, 104), R. sanguineus (1.00%, 17), and D. sinicus (0.18%, 3).

Three to 22 of ticks were grouped into different pools by species, sex, collection site, and blood-feeding status (Supplementary Table 1), and total RNA was extracted from each pool. A total of 139 RNA libraries, involving 1697 adult ticks, were constructed for metatranscriptome sequencing. A total of 6.07 × 109 clean paired-end reads, 100–150 bp in length, were generated from the sequencing after quality control. The percentage of viral reads per library ranged from 0.04% to 19.91%, with an interquartile range of 0.31% to 2.67% (Fig. 2a). The number of viruses detected in tick samples was positively correlated with the relative abundance of viral reads (Spearman correlation test, r = 0.5196, P < 0.01). We estimated the virome diversity at the viral family level in the metatranscriptome data among three tick species. The results revealed that the α-diversity of the virome, qualified by the Shannon index, was significantly higher in H. longicornis and H. concinna ticks than that in D. silvarum (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001). While there was no significant difference between H. longicornis and H. concinna, the two species in the genus Haemaphysalis (Fig. 2b). The viromes were distinctive among H. longicornis, H. concinna, and D. silvarum based on t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) (Fig. 2c).

a Virus abundance (top) and the number of identified viruses with genome sequences (bottom). b The viral α-diversity of H. longicornis, H. concinna, and D. silvarum was assessed. Shannon index was calculated, multiple comparisons were performed by bilateral Kruskal-Wallis test, and P-values were adjusted by Bonferroni method. c Beta diversity analysis of virome compositions across H. longicornis, H. concinna, and D. silvarum using t-SNE.

The normalized abundance of viral species in tick pools was estimated to further clarify the virome diversity among different tick species (Supplementary Fig. 1). The prevalence with 95% Confidence interval (CI) (Supplementary Table 2) and normalized abundance of viral families varied greatly among different tick species. A total of 20 viral families among the positive-sense single-stranded RNA (ssRNA(+)) viruses were identified, with Flaviviridae, Hepeviridae, and Botourmiaviridae being the major families. Viruses in the family Flaviviridae were primarily found in D. silvarum ticks with quite high abundance, those in the family Hepeviridae were widely present in H. longicornis ticks, and those in the family Botourmiaviridae were prevalent and abundant in H. longicornis and R. sanguineus ticks. Among the 11 negative-sense ssRNA (ssRNA(-)) virus families, Arenaviridae, Nairoviridae, and Phenuiviridae families of the Bunyavirales order were the most common, with high abundance across the different tick species. Among the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses, Totiviridae was prevalent, with high abundance in D. silvarum ticks. Regarding the DNA viruses, most viral reads belonged to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, with relatively few reads belonging to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses. Additionally, reads that could not be classified into any known viral families were detected in most samples.

Evolutionary and genomic characterization of tick-associated viruses

The reads were assembled de novo into 28,427 contigs, with an average of 205 contigs per library. Through de novo assembly, a total of 781 metatranscriptome-assembled genomes (MAGs), including 659 complete and 122 nearly complete genomes of viruses were generated, which were subsequently used for downstream analysis and deposited in GenBank (Supplementary Table 3).

Among the 781 MAGs in this study, 382 belonged to ssRNA(+) viruses and were classified into 120 viral species (Fig. 3a), including 61 known and 59 previously undefined viruses (Supplementary Table 4). The 61 known ssRNA(+) viruses belonged to 9 viral families (Iflaviridae, Flaviviridae, Virgaviridae, Caliciviridae, Tombusviridae, Deltaflexiviridae, Mitoviridae, Botourmiaviridae, and Narnaviridae), order Hepelivirales, superclades of Solemoviridae-Tombusviridae, and Hepeviridae-Matonaviridae. Of the newly recognized 59 viral species, 59 fell into Flaviviridae, Hypoviridae, Yadokariviridae, Mitoviridae, Botourmiaviridae, and Narnaviridae families. While the other two viruses fell outside all known viral families in the phylogenies, which were categorized into the putative Solemoviridae-Tombusviridae superclade. The two viruses in superclades were identified from H. concinna, one called Hebei luteovirus showed 86.38% amino acid (aa) identity of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) to Cheeloo luteovirus 28, and the other called Hebei solemo-like virus had 78.12% aa similarity of RdRp to Xinjiang tick-associated virus 1 (GenBank accession number ON408203). Additionally, six newly recognized viruses belonged to the Erysiphe necator-associated species, which were grouped as RNA viruses under the unclassified Riboviria members.

a Phylogenetic analysis of RdRp protein from ssRNA(+) viruses. b Phylogenetic analysis of RdRp protein from ssRNA(-) viruses. c Phylogenetic analysis of RdRp protein from dsRNA viruses. d Phylogenetic analysis of the non-structural replicase proteins in ssDNA viruses. e Phylogenetic analysis of RdRp protein from ormycovirus. The red pentagrams indicate a novel virus in this study. The color of the circle represents the species of tick. Tip are color-coded based on the tick species from which the viral sequences were collected: dark blue (H. longicornis), light blue (H. concinna), pink (D. silvarum), yellow (D. sinicus), and green (R. sanguineus). The circle represents a sequence, while the triangles represent multiple sequences.

A total of 291 MAGs belonged to 31 ssRNA(-) viruses, among which 26 were known, and six were newly identified species (Fig. 2b). The 26 known ssRNA(-) viruses were distributed in seven viral families (Phenuiviridae, Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Mymonaviridae, Chuviridae, and Orthomyxoviridae), and Discoviridae-Peribunyaviridae virus. A novel virus named Hebei Phenui-like virus was in the family Phenuiviridae, which only shared 31.29% aa similarity in RdRp with the closest virus Diaporthe gulyae goukovirus 112. The newly identified Hebei mymona-like virus belonged to the family Mymonaviridae, the RdRp sequence of which had 78.80% aa identity with its closest relative Sanya Mymon tick virus 17. Two novel viruses, Hebei Aspi-like virus 1 and Hebei Aspi-like virus 2 fell into the family Aspiviridae, and shared 82.27% and 58.46% aa identities of RdRp with Plasmopara viticola-associated mycoophiovirus 5 (GenBank accession number MN585281) and Diaporthe gulyae ophiovirus 112, respectively. Hebei bunya-like virus 1 and Hebei bunya-like virus 2 had 34.14% and 57.08% aa similarities to Kristianstad virus (GenBank accession number LC772156) and Ixodes scapularis-associated virus-6 (GenBank accession number MG256514), respectively.

A total of 88 MAGs were derived from 19 dsRNA viruses, involving 11 known and eight newly recognized viruses (Fig. 3c). The 11 known viruses belonged to three families (Totiviridae, Partitiviridae, and Sedoreoviridae). Notably, we assembled four more segments for Beijing Reovi Tick Virus 1 in the family Sedoreoviridae. Our previous study identified only one viral protein (VP1) encoding the putative RdRp7, which shared 99.73% aa similarity with that of Beijing Reovi Tick Virus 1 detected in this study. The four additional segments of Beijing Reovi Tick Virus 1 could be assigned to the genus Orbivirus with corresponding names of VP3, VP4, VP5, and non-structural replicase (NS1)13. Its VP3 shared 50.29% aa identity with St Croix River virus (SCRV). VP4 exhibited 53.97% aa identity with SCRV, VP5 showed 55.93% identity with SCRV, and NS1 displayed 50.29% aa identity with SCRV. Beijing Reovi tick virus 1 showed a close evolutionary relationship with other members in Orbivirus genus.

The eight undefined dsRNA viruses were primarily distributed across four families, Totiviridae, Partitiviridae, Birnaviridae, and Alternaviridae. In the Totiviridae family, Hebei toti-like virus 1 exhibited 81.71% aa similarity to Totiviridae sp. from Rhipicephalus turanicus7, while Hebei toti-like virus 2 showed 62.73% aa similarity to Totiviridae sp. from grassland soil14. In the Partitiviridae family, phylogenetic analysis revealed that Hebei partiti-like virus 1 had 45.29% RdRp aa identity to Tuatara cloaca-associated durna-like virus-9, which was found in Sphenodon punctatus from New Zealand in 202115. Hebei partiti-like virus 2 had 83.42% RdRp aa identity to the closest viral relative Discula destructiva virus 216. Hebei partiti-like virus 3 and Hebei partiti-like virus 4 had RdRp aa similarities of 85.46% and 68.88% to Colletotrichum eremochloae partitivirus 1 from Macrophomina phaseolina17 and Macrophomina phaseolina partitivirus 2 from Colletotrichum eremochloae18 (GenBank accession number MT035912), respectively. A novel virus was assigned to the proposed Alternavirus genus within Alternaviridae family, named Hebei alternavirus, showing 67.24% RdRp aa identity with the closest known relative Fusarium oxysporum alternavirus 119 (GenBank accession number NC_079109). Notably, the RNA genome of Hebei alternavirus contained four ORFs (segment dsRNA1, dsRNA2, dsRNA3 and dsRNA4). Within the family Birnaviridae, a novel virus named Hebei birna-like virus 1 exhibited an identity <75.55% with other members of birnaviruses based on RdRp.

Four MAGs belonged to three known ssDNA viruses in the family Parvoviridae (Fig. 3d), including Ovine parvovirus, canine parvovirus (CPV), and Psittaciform parvoviridae sp. Additionally, 16 MAGs belonged to six novel viruses in ormycovirus (Fig. 3e). Hebei tick virus 3, Hebei tick virus 4, Hebei tick virus 10, and Hebei tick virus 11, alongside other members of the gammaormycovirus clade, shared 87.14%-90.91% aa similarity with Fusarium culmorum ormycovirus 1. Hebei tick virus 12 belonged to alphaormycovirus and shared 12.98%-14.17% aa similarity with Downy mildew lesion-associated ormycovirus 620. Hebei tick virus 9 exhibited less than 6.85% aa similarity with any of the three clades. Phylogenetic analysis positioned it between the betaormycovirus and alphaormycovirus clades (Fig. 3e).

In summary, the 781 MAGs were classified into 179 virus species, including 100 known viruses from 21 families and 79 novel viruses, 62 of which belonged to 13 currently established viral families and the other 17 viruses fell outside all known viral families (Fig. 4) in the phylogenies and were grouped into ‘superclades’ by using a previously adopted tactic8, highlighting the extensive virome diversity in ticks within this region.

Viruses with known or potential pathogenicity to humans

Notably, four viruses with known or potential pathogenicity to humans were identified in this study (Supplementary Fig. 2). Bandavirus dabieense is the causative agent of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), which was previously named SFTS virus21. We identified two MAGs, which were genetically closest to, but distinct from the six known genotypes of Bandavirus dabieense on the phylogenetic tree constructed based on RdRp (Fig. 5a). We then compared their genome sequences with the known six known genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 3). The segment L of the two MAGs shared 99.71% aa similarity with each other, and over 98.51% with the six genotypes21,22,23,24. The segment M had 98.60% aa similarity with each other, and 94.69%-95.43% to the known genotypes. The nonstructural protein possessed 98.63% aa similarity with one another, and 92.15–94.88% to the known genotypes. The nucleoprotein possessed 100% aa similarity with one another, and 98.78–99.18% to the known genotypes. According to identity and phylogeny, the two strains of viruses should be a new genotype of Bandavirus dabieense, pathogenicity of which to humans deserves further investigation.

a Phylogenetic relationship of segment L RdRp gene nt sequences of Bandavirus dabieense. b Phylogenetic relationship of segment L of Orthonairovirus. c Phylogenetic relationship of PB1 protein of Thogotovirus. The dark blue circle represents a sequence from H. longicornis, while the dark blue and light blue triangles represent multiple sequences from H. longicornis and H. concinna, respectively.

Seventeen MAGs in this study belonged to five viral species of the genus Orthonairovirus (Fig. 5b), two of which have been reported to cause human infections. We identified Orthonairovirus nairobiense (NSDV) in H. longicornis and found that it exhibited 96.72% aa similarity of RdRp to the strain from H. longicornis in Liaoning Province of northeastern China (GenBank accession number OQ581155). Xue−Cheng virus (XCV) is a recent emerging human pathogen25, which was identified in H. concinna, and demonstrated 98.46% aa similarity of RdRp to the strain MDJ138 isolate from a patient in China25. In addition, Orthonairovirus huangpiense, Shanxi tick virus 2, and Henan tick virus were detected in this study. Although the three viruses have no clear evidence of pathogenicity, their evolutionary similarity to the known pathogenic Orthonairovirus (Fig. 5b) suggests a potential risk of undiscovered zoonotic diseases.

Three viruses belonged to the family Orthomyxoviridae, including the human-pathogenic Thogotovirus thogotoense in Thogotovirus genus, Qingyang Ortho tick virus 1, and Yanbian Ortho tick virus 1 in Quaranjavirus genus. Thogotovirus thogotoense in this study shared 99.28–99.72% aa identity of RdRp with each other and 97.13% with the TIGMIC_2 strain identified in H. longicornis from China7. All the Thogotovirus thogotoense strains detected from different regions of China, such as Hebei, Shanxi, Shandong, and Guangdong provinces were clustered in the same clade (Fig. 5c), indicating their close evolution in China.

Viruses with known or potential pathogenicity to animals

Notably, we identified the Rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (Lagovirus europaeus, RHDV) for the first time in a H. longicornis tick sample. The complete genome of the virus in this study was 7392 bp in length, with a gene structure typical of the Lagovirus. Phylogenetic analysis based on the VP60 indicated that the RHDV strain in H. longicornis tick was clustered with RHDV2 strains from various animals, and shared 99.48% aa identity to the genetically closest strain isolated from a fatal rabbit from China26 (Fig. 6a), therefore, we named it RHDV2 strain Hebei_106. When we conducted the phylogenetic analysis based on the NS protein, the strain Hebei_106 was clustered with European brown hare syndrome virus (Lagovirus europaeus, EBHSV) strains, sharing 97.26% aa identity with the EBHSV NP1192 strain discovered in European hare (Lepus europaeus) from Poland (GenBank accession number MK440617) (Fig. 6b). This suggested that strain Hebei_106 was a recombinant virus. The recombination analysis identified the recombination breakpoint in the genomic RdRp-VP60 junction, located at position 5340 bp (Fig. 6c).

a Phylogenetic relationship in the genus Lagovirus based on VP60 protein. b Phylogenetic relationship in the genus Lagovirus based on ORF1 protein except VP60. c Genome structure and recombination analysis of the RHDV2 strain. The horizontal axis represents the nt position of the genome, whereas the vertical axis represents the similarity to the two putative parental strains. The green plot indicates the closest major parent, EBHSV strain NC_002615, donor of the NS genes, whereas the orange plot indicates RHDV2 MT505389 strain, the closest minor parent, donor of the VP60 gene. A window size of 400 bp with a step size of 20 bp was used.

Three ssDNA viruses have been known to primarily infected domestic and wild animals, and were detected from ticks in this study (Fig. 7a). We successfully assembled a complete 5501 bp genome sequence of Ovine parvovirus from H. longicornis, the NS1 aa identity of which was 94.56% to that of strain from an infected sheep in China (GenBank accession number PQ274849). CPV that infects canines was identified in H. longicornis and R. sanguineus ticks, and shared 100% aa identity of NS1 to a strain previously identified in an infected domestic dog from China27. Psittaciform parvoviridae sp. previously detected from the orange-bellied parrot (Neophema chrysogaster) in Australia, was first identified in R. sanguineus ticks, showing 99.64% aa similarity in the NS128.

a Family Parvoviridae based on NS1. b Hebei bunya-like virus 1 based on RdRp protein. c Dandong tick virus 1 based on RdRp protein. d Zhejiang mosquito virus based on RdRp gene 3. The color of the circles represents the tick species, dark blue for H. longicornis, pink for D. silvarum, and green for R. sanguineus. The names of viruses infecting humans and mosquito-related viruses from the NCBI database are highlighted in red and cyan, respectively.

Mosquito-related viruses in ticks

Phylogenetic analysis suggested that Hebei bunya-like virus 1 and Dandong tick virus 1 were related to viruses carried by mosquitoes within Bunyavirales (Fig. 7b–d). A novel virus, Hebei bunya-like virus 1, was identified in H. longicornis, H. concinna, and D. silvarum ticks. The virus shares 34.14% aa similarity with Kristianstad virus, previously identified in Culex mosquitoes from Japan (GenBank accession number LC772156). Dandong tick virus 1 exhibited 99.53% aa identity to previously identified from H. longicornis in Liaoning (GenBank accession number ON872556), and clustered together with mosquito-related viruses29. Unlike other Narnaviridae viruses, Zhejiang mosquito virus 3 not only had an ORF encoding RdRp on the negative strand but also encoded an ORF on the reverse complementary strand. Previously, this virus was only found in mosquitoes30, but in this study, we discovered Zhejiang mosquito virus 3 strain Hebei_035 in D. silvarum for the first time, shared nt identities ranging from 95.85% to 97.91% with previously reported strains in the RdRp gene. Phylogenetic analysis showed that Zhejiang mosquito virus 3 formed two distinct clusters, one clade containing Chinese tick-related and mosquito-related viruses, and another clade comprising Australian mosquito-related viruses (Fig. 7d). This finding indicated that Zhejiang mosquito virus 3 strains may have diverged during evolution across different geographic regions. Although mosquitoes were the primary host, the emergence of ticks as a new host suggested a potential transmission route for these viruses through both mosquitoes and ticks.

Discussion

This study focused on the Hebei region surrounding Beijing and Tianjin metropolises of northern China and performed metatranscriptomic sequencing on tick samples collected in the field. From 139 tick pools, we successfully assembled 781 viral sequences belonging to 179 viral species, 79 of which were newly identified, significantly enriching the global knowledge of tick-associated viromes and complementing existing viral taxonomy. Several tick-borne viruses with potential transmission risks were identified, emphasizing the importance of studying viral diversity in urbanized regions. These findings provide critical targets for the monitoring and early warning of urban pathogens in the region and expand the catalog of previously undescribed viruses.

In this study, four human-pathogenic viruses were detected, including Bandavirus dabieense, NSDV, XCV, and Thogotovirus thogotoense. Genetic evolutionary analysis identified a novel genotype of Bandavirus dabieense in H. longicornis, indicating changes in the phylogenetic evolution and genetic diversity of this virus. The emergence of the new genotype may pose potential threats to human and animal health, and its pathogenicity warrants close attention31. The emerging tick-borne diseases caused by the human-infecting viruses in the genus Orthonairovirus of the family Nairoviridae have continuously emerged in recent years, and have become an increasingly serious health threat worldwide32. NSDV, which has long been known to cause sheep disease, was reported to infect humans in India33, and human cases have been continuously identified since then34. The first identification of NSDV from ticks in this region highlighted its potential threat to public health, providing critical data to support enhanced surveillance of tick infections in this region for effective prevention of human infections. XCV has recently emerged as a human pathogen and has been detected in H. concinna and H. japonica ticks, in the region where infected patients are identified, suggesting the potential of the two Haemaphysalis tick species as vectors for XCV25. In this study, we identified XCV in H. concinna, suggesting the virus may be extensively distributed. H. concinna is known to parasitize tens of birds35, which can facilitate the spread of ticks and tick-borne pathogens over long distances, suggesting the possible wide dissemination of XCV. Extensive investigations of ticks and animals are needed to better understand XCV global distribution. Human infections with Thogotovirus thogotoense have been identified in Spain36. Although no cases have been reported in China, the virus has been present in H. longicornis and H. qinghaiensis in various regions7. The detection of the Thogotovirus thogotoense in H. longicornis indicates that its transmission vectors might be limited to ticks in the genus Haemaphysalis, which should be targeted for possible infections with this virus. These findings underscore the need for strengthened surveillance of both human-pathogenic and potentially zoonotic tick-borne viruses in the metropolis surroundings, and highlight the importance of implementing targeted prevention and control strategies to mitigate their public health impact.

RHDV belongs to the genus Lagovirus (family Caliciviridae, order Picornavirales) and causes lethal disease in leporids. The genus Lagovirus also includes the EBHSV37, but neither RHDV nor EBHSV has been reported in any tick. RHDV2, a highly lethal variant of RHDV, has caused disease outbreaks in domestic and wild rabbits globally38,39,40. Our study provides the first detection of RHDV2 in ticks, and recombination analysis indicates that the RHDV2 strain identified in H. longicornis is a recombinant strain. A previous study has suggested that the outbreak of RHDV2 in mainland China may have been linked to imported semen40. However, the detection of RHDV2 in H. longicornis in the region suggests potential tick transmission, supporting the hypothesis of virus circulation within the ecosystem rather than an external importation. H. longicornis might act as a vector, increasing the risk of cross-species infections, particularly in regions with rapid economic development, active trade, and high population density, highlighting the critical need for continuous monitoring. Although the pathogenicity of the recombinant RHDV2 to animals needs further investigation, the possibility of viruses in the genus Lagovirus should not be ignored.

This study leveraged the metatranscriptomic approach to extend virome research, which previously focused primarily on RNA viruses, by identifying three ssDNA viruses: Ovine parvovirus, CPV, and Psittaciform parvoviridae sp. CPV is a fatal pathogen in dogs, with morbidity rates as high as 100% and mortality rates reaching 91%41. Additionally, Psittaciform parvoviridae sp. was detected in D. silvarum ticks in this study, with sequence alignment revealing two mutations (D26N and F52D) in the NS1 protein of this virus. This study significantly expanded our understanding of the genetic diversity, host range, and evolution of DNA viruses and underscored the significant role of metatranscriptomics in viral discovery.

However, one limitation of this study is that multiple ticks with the same sex and sampling site were combined into a single sequencing library. As a result, we were unable to characterize the virome at the level of individual ticks, and viruses present at low abundance may have been missed. In summary, this study filled a critical gap in tick virome research in the region, revealing the extensive viral diversity associated with ticks, with up to 44.13% of potential novel viruses detected in the metropolitan surroundings. These findings enriched the global virosphere and provided a solid foundation for viral diversity research and public health interventions. The detection of viruses infective to both humans (e.g., novel genotype of Bandavirus dabieense, Thogotovirus thogotoense, NSDV, XCV) and livestock (RHDV2, CPV, OPV, and Psittaciform parvoviridae sp.) highlights the urgent need for sustained, region-specific surveillance of tick-borne diseases. Conducting in-depth virome studies in of tick-borne diseases. Our virome analysis of metropolitan peripheries, such as those surrounding Beijing and Tianjin, reveals the coexistence of diverse tick-associated viruses and their potential for spillover, thereby providing critical evidence to guide targeted monitoring, risk assessment, and the development of locally tailored public health interventions. In particular, sustained surveillance and research on tick vectors, will help identify the potential risks of viral transmission and provide a scientific basis for addressing emerging infectious diseases.

Methods

Sample collection

In 2023, tick samples were collected in the Hebei region surrounding Beijing and Tianjin metropolises of northern China (Fig. 1). Ticks were collected from domestic animals or by dragging a standard 1 m2 flannel flag over vegetation. The longitude and latitude of each collection site were recorded. Each tick was morphologically identified to species, gender, and developmental stage by an entomologist (Yi Sun)42. Adult ticks were pooled based on species, sex, collecting sites, and blood-feeding status. R software (v4.4.1) was used to display the spatial distribution of tick samples.

RNA extraction and sequencing library preparation

In brief, ticks were ground in liquid nitrogen using a pre-cooled mortar, and the homogenate was lysed using prepared RNeasy Lysis buffer (RLT solution). The lysate was then directly transferred to a 2 mL collection tube and centrifuged at ≥8000 g (≥10,000 rpm) for 30 seconds, and the supernatant was retained. Total RNA from the supernatant was extracted using the modified AllPrep DNA/RNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The extracted RNA was quantified using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer, and RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2200 (Agilent, Santa Clara, California, USA). Ribosomal RNA was removed using the RiBo-Zero Gold rRNA Removal Kit (Human/Mouse/Rat) (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA), depleting both eukaryotic and prokaryotic rRNA. The remaining RNA was fragmented into about 250–300 bp fragments and reverse transcribed to generate double-stranded cDNA. Metatranscriptomic libraries were then constructed, followed by quality control and sequencing. Library quantification was performed using Qubit fluorometry and qPCR, while fragment size distribution was assessed with a bioanalyzer. Libraries that passed quality assessment were pooled according to effective concentration and desired sequencing depth, and subsequently sequenced. RNA libraries were prepared according to the standard Illumina protocol and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform at NovoGene Co., Ltd.

Quality control and diversity of virome

The low-quality reads were removed from raw sequencing data using AfterQC (v2.3.3)43. Clean reads were then obtained and mapped to different tick genomes using Bowtie2 (v2.3.5.1)44 to remove reads related to tick genomes. Kraken2 (v2.1.2)45 was employed to map the remaining reads, excluding the tick genome, to the NCBI nucleotide (nt) sequence database. The calculated correlation between the number of detected RNA viruses and viral read abundance was calculated using Spearman correlation test. The abundance of each viral family was quantified as reads per million mapped reads (RPM). Using the Vegan package (v2.6-4) to compare virome diversity in relation to different tick species and compute the Shannon index for each sample46. Data visualization was carried out using the ggplot2 package in R, and differences in viral diversity among major tick species were assessed using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Assembly and annotation of viral contigs

Viral sequences were assembled using Trinity (v2.13.2)47. All assembled sequences were compared with the NCBI non-redundant protein database using Diamond BLASTx (v2.0.13)48 and the NCBI nt sequence database using blastn (v2.12.0+)49. The assembled contigs were annotated based on the best BLAST match (E < 1 × 10−5), and viral contigs were selected for downstream analysis.

Viruses were classified according to the standards of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV, https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/). For viruses lacking established classification criteria, those with a sequence similarity greater than 90% in the RdRp) for RNA viruses or in conserved replicase protein for DNA viruses, compared to known viral species were classified as the same species50,51,52. Conversely, if the similarity was below 90%, the virus was considered a newly identified virus species. The names of all putative novel viral species were defined8,9. For viruses assignable to a genus but representing new species within that genus, names were derived from the location of discovery followed by the genus name. For novel viruses identified to the level of order or family but not at the genus, they were named using the location of discovery followed by the family (or order) prefix and the suffix “-like virus”. For viruses that could not be clearly assigned to a specific order, they were named based on the location of discovery, followed by “tick virus”. Novel viral genomes were validated by examining read coverage and continuity using Bowtie2 (v2.3.5.1).

Analyses of phylogenetic and recombination

The aa sequences of the conserved RdRp protein for RNA viruses, and replicase protein for DNA viruses were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database, and aligned using MAFFT (v7.490)53. The alignments were trimmed using TrimAI (v1.4)54, and the best-fit aa or nucleotide substitution model was determined based on the multiple sequence alignment. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in IQ-TREE (v2.2.2.3)55. The phylogenetic trees were visualized using the ggtree package56 in R, with the midpoint set as the root. The recombination in viral genome sequences was analyzed using SimPlot (v3.5.1) software57.

Data availability

The metagenomic data are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (SRR29721438-SRR29721576) under Bioproject PRJNA1132387, and the viral assembled genomes are available in the GenBank with the accession numbers PQ150489-PQ150637, PQ150640-PQ150641, PQ167992, PQ180391-PQ181006, PQ206367-PQ206373, PQ268477-PQ268478, PQ268456-PQ268458, and PV157291.

Code availability

No original code was used in this study. All data analysis was performed using publicly available software/tools.

References

Parola, P. & Raoult, D. Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32, 897–928 (2001).

Zhou, H., Xu, L. & Shi, W. F. The human‑infection potential of emerging tick‑borne viruses is a global public health concern. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 21, 215–217 (2023).

Harvey, E. et al. Extensive diversity of RNA viruses in Australian ticks. J. Virol. 93, e01358–18 (2019).

Wille, M. et al. Sustained RNA virome diversity in Antarctic penguins and their ticks. ISME J. 14, 1768–1782 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Viromes and surveys of RNA viruses in camel-derived ticks revealing transmission patterns of novel tick-borne viral pathogens in Kenya. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 10, 1975–1987 (2021).

Xu, L. et al. Tick virome diversity in Hubei Province, China, and the influence of host ecology. Virus Evol. 7, veab089 (2021).

Ni, X. B. et al. Metavirome of 31 tick species provides a compendium of 1,801 RNA virus genomes. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 162–173 (2023).

Ye, R. Z. et al. Virome diversity shaped by genetic evolution and ecological landscape of Haemaphysalis longicornis. Microbiome 12, 35 (2024).

Tian, D. et al. Virome specific to tick genus with distinct ecogeographical distribution. Microbiome 13, 57 (2025).

Wu, Y. F. et al. Emerging tick-borne diseases in mainland China over the past decade: a systematic review and mapping analysis. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 59, 101599 (2025).

Uspensky, I. Tick pests and vectors (Acari, Ixodoidea) in European towns, introduction, persistence and management. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 5, 41–47 (2014).

Wu, C. F. et al. Mycovirome of Diaporthe helianthi and D. gulyae, causal agents of Phomopsis stem canker of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Virus Res. 351, 199521 (2025).

Attoui, H. et al. Complete sequence characterization of the genome of the St Croix River virus, a new orbivirus isolated from cells of Ixodes scapularis. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 795–804 (2001).

Starr, E. P., Nuccio, E. E., Pett-Ridge, J., Banfield, J. F. & Firestone, M. K. Metatranscriptomic reconstruction reveals RNA viruses with the potential to shape carbon cycling in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25900–25908 (2009).

Waller, S. J. et al. Cloacal virome of an ancient host lineage - The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) - Reveals abundant and diverse diet-related viruses. Virology 575, 43–53 (2022).

Rong, R. et al. Complete sequence of the genome of two dsRNA viruses from Discula destructiva. Virus Res. 90, 217–224 (2002).

Gilbert, K. B., Holcomb, E. E., Allscheid, R. L. & Carrington, J. C. Hiding in plain sight: new virus genomes discovered via a systematic analysis of fungal public transcriptomes. PLoS One 2019 14, e0219207 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Divergent RNA viruses in Macrophomina phaseolina exhibit potential as virocontrol agents. Virus Evol. 7, veaa095 (2020).

Wen, C. et al. Molecular characterization of the first Alternavirus identified in Fusarium oxysporum. Viruses 13, 2026 (2021).

Forgia, M. et al. Three new clades of putative viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases with rare or unique catalytic triads discovered in libraries of ORFans from powdery mildews and the yeast of oenological interest Starmerella bacillaris. Virus Evol. 8, veac038 (2022).

Yu, X. J. et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1523–1532 (2011).

Yoshikawa, T. et al. Phylogenetic and geographic relationships of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China, South Korea, and Japan. J. Infect. Dis. 212, 889–898 (2015).

Fu, Y. et al. Phylogeographic analysis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from Zhoushan Islands, China: implication for transmission across the ocean. Sci. Rep. 6, 19563 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Ecology of the tick-borne Phlebovirus causing severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in an endemic area of China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004574 (2016).

Zhang, M. Z. et al. Human infection with a novel tickborne Orthonairovirus species in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 200–202 (2025).

Hu, B. et al. Emergence of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus 2 in China in 2020. Vet. Med Sci. 7, 236–239 (2020).

Wang, H. L. et al. Isolation and sequence analysis of the complete NS1 and VP2 genes of canine parvovirus from domestic dogs in 2013 and 2014 in China. Arch. Virol. 161, 385–393 (2016).

Klukowski, N., Eden, P., Uddin, M. J. & Sarker, S. Virome of Australia’s most endangered parrot in captivity evidenced of harboring hitherto unknown viruses. Microbiol Spectr. 12, e0305223 (2024).

Feng, Y. et al. A time-series meta-transcriptomic analysis reveals the seasonal, host, and gender structure of mosquito viromes. Virus Evol. 8, veac006 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Association of virome dynamics with mosquito species and environmental factors. Microbiome 11, 101 (2023).

Cui, H. et al. Global epidemiology of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in human and animals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 48, 101133 (2024).

Zhou, H., Xu, L. & Shi, W. F. The human-infection potential of emerging tick-borne viruses is a global public health concern. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 215–217 (2023).

Dandawate, C. N., Work, T. H., Webb, J. K. & Shah, K. V. Isolation of Ganjam virus from a human case of febrile illness, a report of a laboratory infection and serological survey of human sera from three different states of India. Indian J. Med. Res. 57, 975–982 (1969).

Krasteva, S., Jara, M., Frias-De-Diego, A. & Machado, G. Nairobi sheep disease virus, a historical and epidemiological perspective. Front Vet. Sci. 7, 419 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. An integrated data analysis reveals distribution, hosts, and pathogen diversity of Haemaphysalis concinna. Parasit. Vectors 17, 92 (2024).

Lledó, L., Giménez-Pardo, C. & Gegúndez, M. I. Epidemiological study of thogoto and dhori virus infection in people bitten by ticks, and in sheep, in an area of Northern Spain. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 17, 2254 (2020).

Le, P. Proposal for a unified classification system and nomenclature of lagoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 98, 1658–1666 (2017).

Hall, R. N. et al. Emerging rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDVb), Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 2276–2278 (2015).

Toh, X. Y. et al. First detection of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV2) in Singapore. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, 1521–1528 (2022).

Qi, R. B. et al. The outbreak of rabbit hemorrhagic virus type 2 in the interior of China may be related to imported semen. Virol. Sin. 37, 623–626 (2022).

Chen, S. B. et al. Global distribution, cross-species transmission, and receptor binding of canine parvovirus-2, risks and implications for humans. Sci. Total Environ. 930, 172307 (2024).

Huang, B. & Shen, J. Morphological taxonomic map of animal and poultry parasites in China, Beijing (2006).

Chen, S. F. et al. AfterQC, automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinforma. 18, 80 (2017).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 257 (2019).

Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.6-4. https://libraries.io/cran/vegan (2022).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+, architecture and applications. BMC Bioinforma. 10, 421 (2009).

Shi, M. et al. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature 540, 539–543 (2016).

Shi, W. Q. et al. Trafficked Malayan pangolins contain viral pathogens of humans. Nat. Microbiol 7, 1259–1269 (2022).

Ye, R. Z. et al. Towards tick virome and emerging tick-borne viruses: Protocols, challenges and perspectives. iMetaOmics 2, e70022 (2025).

Rozewicki, J., Li, S., Amada, K. M., Standley, D. M. & Katoh, K. MAFFT-DASH, integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W5–w10 (2019).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl, a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE, a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Yu, G., Lam, T. T., Zhu, H. & Guan, Y. Two methods for mapping and visualizing associated data on phylogeny using ggtree. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 3041–3043 (2018).

Samson, S., Lord, É. & Makarenkov, V. SimPlot++, a Python application for representing sequence similarity and detecting recombination. Bioinformatics 38, 3118–3120 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant no.: 2023YFC2305901), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant no.: BX20240215, 2025M770754).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-C.C., L.-Z., X.-M.C., R.-Z.Y. designed and supervised the research. W.-Y.G., X.X., X.-M.C., T.-H.W., Y.-T.L., and J.W collected samples. W.-Y.G., Y.-T.L., Y.S., L.-Y.X., and T.-H.W. prepared materials for sequencing. W.-Y.G., R.-Z.Y., N.J., J.-F.J., and X.-M.C. set up the database. W.-Y.G., Y.-Y.L., and R.-Z.Y. performed genome analysis and interpretation. W.-Y.G. and R.-Z.Y. prepared figures and tables. W.-C.C. and W.-Y.G. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, W., Xia, X., Wang, T. et al. Diverse virome and potential pathogens in five tick species from metropolis surroundings of Beijing and Tianjin, China. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 12, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00878-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-025-00878-5