Abstract

Breast cancer (BCa), a leading malignancy among women, is characterized by morphological and molecular heterogeneity. While early-stage, hormone receptor, and HER2-positive BCa are treatable, triple-negative BCa and metastatic BCa remains largely untreatable. Advances in sequencing and proteomic technologies have improved our understanding of the molecular alterations that occur during BCa initiation and progression and enabled identification of subclass-specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Despite the availability of abundant omics data in public repositories, user-friendly tools for multi-omics data analysis and integration are scarce. To address this, we developed a comprehensive BCa data analysis platform called MammOnc-DB (http://resource.path.uab.edu/MammOnc-Home.html), comprising data from more than 20,000 BCa samples. MammOnc-DB facilitates hypothesis generation and testing, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic targets identification. The platform also includes pre- and post-treatment data, which can help users identify treatment resistance markers and support combination therapy strategies, offering researchers and clinicians a comprehensive tool for BCa data analysis and visualization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BCa) is one of the most common cancers in women worldwide. Since the mid-2000s, the incidence of BCa has increased by approximately 0.5% annually1. The etiology of BCa involves factors such as genetic predisposition, lifestyle changes, and aging2. Genetic mutations, familial history, demographic variables, medical background, and modifiable risk factors such as obesity, alcohol intake, and smoking are involved in its development3,4,5. BCa tumors are classified into distinct subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+, and TNBC), characterized by expression levels of estrogen and progesterone receptors, and HER2 expression in tumor cells. The hormone receptor-expressing BCa as well as HER2-positive tumors have viable treatment options4,6. Early-stage BCa is considered curable; however, despite significant progress in diagnosis and treatment, advanced/metastatic stage is associated with high mortality. Although BCa initially responds to treatments, may eventually, can recur and develop therapy resistance7,8. However, the heterogeneity of BCa poses a substantial challenge in diagnosis and treatment, requiring precision medicine to address the diverse molecular subtypes involved9.

With the availability of high-throughput technologies from advanced molecular profiling, such as next-generation sequencing and mass spectrometry, researchers can evaluate specific biomarkers and molecular signatures associated with tumor subtypes and identify potential therapeutic targets10. Although data from next-generation sequencing have shed light on the molecular evolution of BCa, it is necessary to understand and process these molecular data with clinical information to enhance the capability of precision medicine and precision targeting approaches11. Although large amounts of data are available in public repositories, there are opportunities to develop user-friendly resources that allow cancer researchers to leverage the data effectively.

Large-scale cancer “Omics” data, generated using various techniques such as microarray, bulk RNA-seq, scRNA-seq, ChIP-seq, and MS/MS data for genetic, epigenetic, and proteomic data, are archived in numerous public repositories. From the perspective of a researcher with limited bioinformatics support, performing an in-depth analysis of the volume of genomic and proteomic data available for BCa is challenging. A focused and comprehensive web resource that provides integrative analysis, including data for metastatic BCa and response to BCa treatments, will be useful. Recognizing unmet need and opportunities to develop a comprehensive resource facilitating BCa data analysis and visualization, we developed the MammOnc-DB, a user-friendly portal for integrative analysis and visualization of BCa data.

MammOnc-DB incorporates data that were collected, curated, and integrated from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus. In addition, we utilized Proteomics Identifications Database (PRIDE) and ProteomeXchange to obtain proteomic data. MammOnc-DB also contains multi-omics data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), the METABRIC, Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), and Sweden Cancerome Analysis Network – Breast (SCAN-B) Consortium. Our data procurement and processing included multi-omics studies that included data for normal breast tissue, primary BCa tissue, and metastatic BCa samples, with associated clinical information. In addition, we included data on BCa patients treated with various therapies.

Using MammOnc-DB, researchers can access multi-omic and multiple publicly available BCa datasets. It provides information and enables users to analyze the expression of genes (mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs) and proteins in primary and metastatic BCa along with available normal samples and across tumor subgroups based on tumor stage, tumor grade, race, molecular subtype, histological subtype, or other available clinicopathologic features. By utilizing MammOnc-DB to identify differentially expressed genes, one can identify the top differentially expressed genes associated with specific clinical features. Additional options include Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and evaluation of epigenetic changes. Users can download high-resolution graphics depicting expression profiles and patient survival information in various forms.

The MammOnc-DB enables researchers to utilize high-throughput BCa omics data to identify potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for BCa. Furthermore, in silico validation of selected genes using the independent studies integrated into this platform. With subgroup-specific data analysis, one can identify gene alterations in subsets of BCa, allowing the development of hypotheses and testing the underlying biology for this dysregulation. In the future, our goal is to populate the MammOnc-DB platform with additional data as they become available.

Results

Figure 1 provides an overview of MammOnc-DB, and Supplementary Table 1 lists the currently available studies within the MammOnc-DB. Step-by-step explanation of data analysis and formatting is available in Supplementary Note 1.

The MammOnc-DB homepage allows users to select the type of omics they are interested in, such as gene expression, protein expression, and gene regulation, through the menu bar. Additionally, the platform also contains a tutorial page to assist users in using the portal effectively

The functionality of MammOnc-DB extends to various types of analysis, which are described in the following sections.

Heatmap facilitating identification of top differentially expressed genes

The gene expression page of MammOnc-DB features a left panel that allows users to identify genes that are either over or under-expressed in a dataset (Fig. 2A). For instance, if a user selects “TNBC” under “SCAN-B” in Panel 1, they will be directed to a dedicated page that displays the over-expressed and under-expressed genes in the form of a heatmap. Figure 2B shows a heatmap representing the top 25 genes that are over- or under-expressed, comparing non-TNBC tumors (n = 8332) and TNBC (n = 874) tumors in the SCAN-B dataset. This page allows users to identify up to the top 250 over-or under-expressed genes in the dataset. Moreover, by clicking on the gene name in the chosen study, users can access expression information about each gene in that study. Additionally, our portal offers the option of identifying over and under-expressed lncRNAs and miRNAs using heatmap (Supplementary Fig. 1).

A Users can switch between RNA-seq and scRNA-seq data. In Panel 1, users can access a compilation of studies, along with relevant clinical characteristics, allowing for the examination of over-expressed and under-expressed genes. Panel 2 allows users to assess the expression of genes of interest across various studies. B Heatmap generated from Panel 1 of the gene expression page. The Heatmap shows the top over-expressed and under-expressed genes in the SCAN-B dataset, comparing non-TNBC and TNBC tumors.

Identifying the expression pattern of a queried gene across different datasets with subgroup classifications

Using Panel 2 on the gene expression page, users can search for their specific gene of interest and determine whether it is related to protein-coding, miRNA, or lncRNA across a range of datasets and analyze their expression patterns in relation to various clinicopathologic features (Fig. 2A). In the gene expression page, users have the option to select between “bulk RNA-sequencing” or “scRNA-seq” data, enabling them to input their gene of interest and choose a study from the available choices (Fig. 3A). MammOnc-DB currently offers 20 studies for bulk RNA-seq (TCGA-BRCA, SCAN-B, ABiM_405, ABiM_100, OSLO2EMIT0, GSE58135, GSE142731, GSE183947, GSE100925, GSE47462, GSE184196, GSE122630, GSE163882, GSE130660, GSE99630, GSE68359, GSE131276, GSE209998, GSE173661, and GSE96058), two microarray (METABRIC and Van de Vijver et al.), two microarray compendium datasets (Creighton breast tumor compendium and Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy compendium), five scRNA-seq studies (Qian et al., Gao et al., Wu et al., Azizi et al., and Griffiths et al.,), and one snRNA-seq (Bhat-Nakshatri et al.,) which are categorized into primary, metastatic, and treatment-related studies of BCa.

A Users can explore genes of interest by entering their names into the text box and selecting from available studies. Upon submission, users are redirected to an intermediate page listing links to analyze expression and survival associations. B Box-whisker and jitter plots illustrating PSAT1 expression in subgroups of the METABRIC study, including ER Status, PR Status, and PAM50 and Claudin subtypes, and lists additional available classifications. C Bar plot depicting the gene effect score of PSAT1 in multiple breast cancer cells using data from DepMap. D Kaplan–Meier plots showing the association between PSAT1 expression and patient survival in the METABRIC dataset.

For example, the PSAT1 gene was typed in the text box, “protein-coding” was the gene type and the “METABRIC” study was selected. Clicking the “Submit” button leads them to an intermediate page displaying the gene name, analysis types, and external links to additional resources (Fig. 3A). Clicking on the “Expression” button directs users to the expression page, where box and jitter plots with corresponding p-values for various categories are presented, with the statistical analysis being an unpaired Welch t-test. Figure 3B shows a boxplot that illustrates the expression pattern of PSAT1 in the METABRIC study. It compares ER Negative (n = 429) and ER (n = 1445), positive patients, showing a statistically significant with a p-value less than 0.001. Users can also visualize the results in terms of jitter plots by clicking the button. Examples of PSAT1 expression in METABRIC, based on PR Status, and PAM50 and Claudin subtype are shown as jitter plots in Fig. 3B. Data from additional studies and classifications for different genes are represented in Supplementary Fig. 2.

The DepMap button at the bottom allows users to access a comprehensive dataset consisting of 40 BCa cell lines and their corresponding gene effect scores. These scores are derived from CRISPR knockout screens conducted by Dempster et al.12. This feature allows users to assess the impact of gene knockout in each cell line. An example of PSAT1 gene knockout and the associated gene effect score in various breast cancer cell lines are depicted as a bar plot in Fig. 3C.

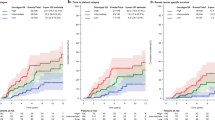

In addition to analyzing gene expression, users can utilize the “Survival” button to perform Kaplan–Meier analysis for their genes of interest. The survival profile of PSAT1 in the METABRIC dataset shows that higher expression of PSAT1 was significantly associated with poor survival (p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 3D. Supplementary Fig. 3 present additional multivariate Kaplan-Meier plots of lncRNA (PCAT1) and miRNA (hsa-mir-7706) from TCGA dataset.

Furthermore, users can retrieve scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data through the gene expression section, allowing them to discern expression patterns within various clusters visualized as UMAP, violin plots, and ridge plots (see Fig. 4). An illustration of the expression pattern of ARID5B in Azizi et al., is provided as an example, displaying UMAP, violin plots, and ridge plots, comparing its expression in different subclasses of T cells. Additional studies and classifications are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4.

A Users can input a gene of interest and select from available studies. B Expression of ARID5B across various T cell clusters from Azizi et al. 72 study. The expression is visualized using UMAP, violin plot, and ridge plot, providing insights into the gene’s expression patterns in distinct T cell clusters.

Analyzing the expression patterns of target proteins across various datasets and patient subgroups

Users can determine the expression pattern of a specific protein by utilizing the protein expression page in MammOnc-DB. This page was designed similarly to the gene expression page. Users can input the name of the gene of interest for the available studies (CPTAC, Tommaso De Marchi et al., (PXD01431), Goming et al., (PXD018830), and Anurag M et al.,) and the protein expression results were observed through a box and jitter plot format (Fig. 5A). An illustrative example of TK1 expression is shown in Fig. 5B, which displays the total and phosphoprotein expression of TK1 in relation to various clinical features. Additional studies and classifications are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Transcription factor binding site analysis: ChIP-seq data exploration

Processed ChIP-seq datasets are incorporated into MammOnc-DB to evaluate histone modifications, Transcription factor binding (GATA3, FOXA1), and ER ligand treatment in different breast cancer BCa cell lines (GSE85158, GSE165280, GSE178253, GSE117941, and GSE178373). To facilitate interpretation, ChIP-seq results are presented in an interactive genome visualization format. Users can enter a specific gene and observe the binding of markers in either the promoter or gene body regions (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B shows a graphical representation of ChIP-seq results in MammOnc-DB. The figure displays the binding patterns of ER bound to different ligands (Tamoxifen, E2, GD 0927, and GNE 274) at STK11 genomic locations in the MCF7 cell line, providing a visual depiction in the IGV.

Case studies have also been included and are available in Supplementary Note 2.

Discussion

Large-scale cancer omics data have been generated due to advancements in high-throughput technologies, including sequencing techniques and a reduction in the cost of sequencing. Omics data are critical for understanding the molecular changes and mechanisms underlying breast cancer development and progression, which can help to identify biomarkers and therapeutic targets. To maximize the utility of publicly available multi-omics data, there is a need to develop an easy-to-use web portal that enables researchers and clinicians to perform comprehensive analyses of these data and visualize them. Data collection, processing, and analysis require dedicated effort from experts in various fields, including pathology, computational biology, and statisticians.

We created MammOnc-DB platform to explicitly focus on BCa-related omics data analysis and visualization. While our previous effort UALCAN provides pan-cancer data analysis13,14, MammOnc-DB incorporates transcriptomics and proteomics data from various consortia and public repositories. This platform utilizes bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq), single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq), ChIP-seq, and mass spectrometry (MS) data. Bulk RNA-seq provides a comprehensive view of gene expression patterns across tumor tissues, offering a broad understanding of the transcriptional landscape. Conversely, scRNA-seq explores the heterogeneity of cells, uncovering distinctive cell populations within tumors. This level of analysis is essential for identifying rare cell types, elucidating tumor progression, and mapping cellular lineage connections. Additionally, scRNA-seq data can unveil specific transcriptional profiles of individual cell types, which may be obscured in bulk RNA-seq data, facilitating a more accurate identification of potential therapeutic targets and biomarkers. ChIP-seq enables the discovery of DNA-protein interactions and epigenetic changes, shedding light on the regulatory processes governing gene expression. This approach is necessary for understanding the impact of transcription factors and other regulatory proteins on the advancement of BCa. In addition, MS investigations unveil the proteomic profile, outlining protein levels, modifications after translation, and interactions between proteins. By combining these sets of data, a holistic understanding of the molecular changes in BCa can be achieved.

Integrating multi-omics data in MammOnc-DB allows users to conduct in-silico analysis and validation of target genes that are specific to various tumor subgroups. This functionality facilitates hypothesis generation based on available data. Moreover, the platform serves as a tool for discovering new biomarkers crucial for early detection, prognosis, and prediction of responses to treatment. By analyzing pre- and post-treatment data, researchers and clinicians can identify markers that indicate therapy response, which could guide clinical decision-making. Incorporating gene expression, gene regulation, and protein data enhances the reliability of the identified biomarkers.

Despite the advancements and the potential of MammOnc-DB, limitations should be acknowledged. Due to the lack of access to raw data, different normalization methods were present in the processed data, which could introduce variability and affect the comparability and interpretation of the results. Since MammOnc-DB relies on publicly available datasets, there is a potential for bias introduced by the selection and representation of these datasets.

Some of the recent efforts provide valuable insights into methodologies for surface target discovery or the development of online platforms. Schettini et al., describes an in silico approach to identifying breast cancer subtype-specific cell surface antigens, focusing on selecting safe and effective targets for CAR-T cell therapies and antibody-drug conjugates15. Another study explores the expression of antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) targets and the data can be explored at TNMPLOT (https://tnmplot.com)16. CARTAR (https://gmxenomica.github.io/CARTAR/) is a web tool to identifying potential targets for CAR-T cell therapies. This study explores the use of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics for mapping cell populations and identifying high-precision, targetable antigens17. While resources such as cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/)18,19,20, UCSC Xena (https://xena.ucsc.edu/)21, and GEPIA2 (https://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/)22, are widely used for cancer genomics research, MammOnc-DB distinguishes itself through its comprehensive multi-omics integration and subgroup-specific focus. In addition, MammOnc-DB incorporates primary and metastatic breast cancer data alongside preclinical models such as drug-treated cell lines and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), making it uniquely suited for identifying biomarkers specific to therapy response and resistance. Moreover, most major resources primarily rely on datasets like TCGA or microarray data, with limited inclusion of proteomic and epigenetic information. MammOnc-DB addresses this gap by integrating gene expression, regulation, and protein data, enhancing the reliability of biomarkers identified. These comparisons show MammOnc-DB’s unique contributions within the landscape of target discovery tools.

We will maintain platform dynamics by integrating into MammOnc-DB additional molecular datasets, such as DNA copy number alterations, DNA methylation data from Illumina arrays, and information on transcription factors binding using ChIP-Seq data. Further, we will include additional datasets as they become available. Furthermore, we intend to analyze and include spatial transcriptomics data from public repositories. We expect to be responsive to user’s needs and suggestions when possible and will upgrade MammOnc-DB as appropriate. In summary, MammOnc-DB will serve as a valuable resource for BCa researchers and clinicians, enabling them to explore the diverse multi-omics data related to BCa and facilitating discoveries of BCa biomarkers and targets.

Methods

TCGA, CPTAC, SCAN-B, METABRIC, and CCLE data analysis

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provides data on genomics and transcriptomics for various cancers. We downloaded RNA-sequencing data from Genomics Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) related to TCGA Breast cancer (BRCA). As TCGA provided level-3 data, we did not perform data processing. In addition, we downloaded methylation data from TCGA BRCA using the DownloadMethylationData() function from TCGA-assembler (https://ccte.uchicago.edu/TCGA-Assembler/index.php). The unwanted column information in the data was removed by using ProcessMethylation450Data(). When CpG sites corresponded to more than one gene, average methylation values were calculated using CalculateSingleValueMethylationData().

We also obtained processed transcriptomic data from studies such as SCAN-B, ABiM_405, ABiM_100, OSLO2-EMIT023,24,25,26, Creighton Breast Tumor Compendium27,28, Van de Vijver et al.29, Neo-adjuvant Chemotherapy Response Compendium dataset30, and METABRIC dataset31 through literature search. These studies included gene expression values along with the patient clinical features.

From the Human Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and DepMap portal (https://depmap.org/portal/download/all/), CRISPR knockout screens of BCa cell lines were obtained as gene-effect scores from Achilles and Sanger’s SCORE project. In this study, the scores were normalized so that nonessential genes had a median score of 0, while independently identified common essential genes have a median score of -1. Gene Effect scores were inferred using Chronos12. The integration of the Broad and Sanger datasets followed the methodology outlined by Pacini et al., with the exception that quantile normalization was omitted32.

In addition, we downloaded the BCa proteomics data from Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) from Proteomics Data Commons (https://proteomics.cancer.gov/programs/cptac). The integration and analysis of these data have been previously reported33,34. In summary, protein expression values downloaded from the CPTAC data portal were log2 normalized for each sample. Z-values for each protein in each sample were then calculated as the number of standard deviations from the median across samples.

RNA-seq Data Analysis

We procured raw data from NCBI GEO for GSE5813535, GSE14273136, GSE18394737, GSE10092538, GSE4746239, GSE184196 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE184196), GSE12263040, GSE16388241, GSE13066042, GSE9906343, GSE6835944, and GSE13127645. The raw data from NCBI GEO were downloaded using fastq-dump function from SRA Toolkit (https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools). The adapter sequences in the downloaded fastq files were trimmed and quality checked by Trim Galore (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore). The trimmed files were mapped to hg38 genome by using the HISAT2 (https://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/) alignment tool, followed by bam conversion and sorting by SAMTools46. The gene counts from the bam files were obtained by using HTseq-counts function47. The gene counts were converted either to FPKM or to RPKM by using R or the Python package, respectively (https://github.com/AAlhendi1707/countToFPKM). When raw data were not available for studies such as GSE20999848, GSE173661 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE173661), and GSE9605826, we procured the processed data and performed downstream analysis. The statistical analysis was conducted with an unpaired welch t-test.

Gene expression array data analysis

For the “Creighton Breast Tumor Compendium” dataset27,28 of nine separate breast tumor expression profiling datasets for survival analysis, gene transcription profiling datasets (all on Affymetrix U133 array, A set, and all with DMFS as an outcome measure) were obtained from previous studies (Loi, GEO:GSE6532; Wang, GEO:GSE2034; Desmedt, GEO:GSE7390; Miller, GEO:GSE3494; Schmidt, GEO:GSE11121; Zhang, GEO:GSE12093; Minn, GEO:GSE2603 and GEO:GSE5327, Chin, http://cancer.lbl.gov/breastcancer/data.php. Genes within each dataset were first normalized to standard deviations from the median; samples from the Loi dataset that were also represented in Desmedt were excluded from Loi. When multiple gene array probe sets referenced the same gene, the probe set with the highest average variation across samples for the nine datasets was selected to represent the gene.

For the chemotherapy response expression compendium dataset30, we previously assembled a compendium of eight different public breast cancer expression datasets49,50,51,52,53,54,55, involving gene expression profiling of pre-treatment breast tumor biopsies from patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, with patient response recorded at the end of treatment. The compendium, representing 1240 tumor expression profiles, involved all datasets being generated using the same Affymetrix gene array platform. We normalized the expression values within each dataset in the same manner as described above for the Creighton dataset.

Proteomics data analysis pipeline

The output files from PRIDE were converted to raw format using msConvert56. We obtained raw files for studies such as PXD01243157 and PXD01883058 from PRIDE. MaxQuant and Andromeda search engines were used to process the downloaded MS/MS data, with reference to Homo sapiens UniProt proteome (UP000005640)59. The MaxQuant parameters were set based on the proteolytic enzyme used, fixed and variable modifications, quantification approach, and data acquisition method. To perform downstream statistical analysis, the output files from MaxQuant analysis were used as input files for Perseus60. NA values were eliminated from the resulting file, considering the condition that the row should have only three or fewer values. Additionally, the values were log-normalized for further analysis. In addition, we also downloaded processed gene level proteomics data from Anurag M et al., research article61.

ChIP-seq data analysis

The data associated with GSE8515862, GSE16528063, GSE17825364, GSE11794165, and GSE17837366 studies were downloaded from NCBI GEO using the fastq-dump from SRAToolkit (https://github.com/ncbi/sra-tools). The quality of the raw data was assessed by FastQC (https://github.com/s-andrews/FastQC), followed by removing the adapter sequences using Trim Galore (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore). The human reference (hg38) was used for alignment with trimmed reads, using BWA mem14. Duplicate reads were identified using Picard (https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard), followed by merging the technical replicates using SAMtools46. The obtained bam files were converted to bed and bigwig files using BamToBed and bamCoverage tools67. Peak calling was performed (NarrowPeaks for transcription factors and Broad Peaks for histone modification) with input DNA or IgG as controls, using MACS268.

scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data analysis

The processed data for BCa single-cell sequencing were downloaded from the Curated Cancer Cell Atlas (https://www.weizmann.ac.il/sites/3CA/)69. We procured associated data and meta files for studies by Qian et al. 70, Gao et al. 71, Azizi et al. 72, Wu et al. 73, and Griffiths et al. 74. For Bhat-Nakshatri et al. study, we procured the data from CZ CELLxGENE (https://cellxgene.cziscience.com/)75. Using the Seurat R package, we filtered the cells to have at least 1000 genes in each barcode76. These filtered cell counts were normalized, batch-corrected using Harmony, and annotated based on the available clinical features77.

Data formatting and visualization

We integrated genomic, proteomic, and epigenetic studies into a user-friendly web resource built using PERL CGI. The data analysis results were depicted via interactive visualizations using public and in-house Java script libraries, and Python Flask applications.

Using R and PERL scripts, gene expression matrix files from RNA-seq and scRNA-seq studies and protein expression matrix files from proteomic studies were categorized based on tumor grade, tumor stage, patient’s age, patient’s race, nodal metastasis status, molecular subtype, treatment, and other associated categories.

Categorized and formatted data files were utilized to generate various graphical outputs such as heatmaps, box plots, jitter plots, Kaplan–Meier curves, UMAP plots, and violin plots as representations that address heterogeneity by comparing gene/protein expression along with various clinical features in each dataset. ChIP-seq results highlighting epigenetic modifications near the gene region are displayed as IGV plots.

Visualization of differentially expressed genes

Heatmap visualization was employed to visualize the most differentially expressed mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs, and proteins in various BCa datasets. To compile a list of the top 250 genes that exhibited either over-expression or under-expression in each subtype, we initially identified genes with FPKM values that displayed significant differences (p values < 0.05). From this initial selection, we considered only genes with a median FPKM value of 1 or higher. Finally, the genes were ranked based on the ratio of the mean FPKM values in tumor samples to the mean FPKM values in normal samples. To generate an interactive heatmap illustrating the top over- and under-expressed genes in a dataset, we utilized the Highcharts library from JavaScript (http://www.highcharts.com/).

Visualization of individual gene expression patterns

Box and Jitter plots were employed to depict the expression levels of the genes in normal samples, primary breast tumors, metastatic breast tumors, and various treatment groups, along with the associated clinical characteristics. The Highcharts library from JavaScript was used to generate the visualizations representing the interquartile range (IQR), including minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, and maximum values, utilizing the data obtained from data formatting.

Visualization of scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq based gene expression

The techniques utilized for visualizing single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq data included UMAP, violin plots, and ridge plots. These visualizations were generated using Python, with pandas (https://pandas.pydata.org/) for data manipulation and Plotly (https://plotly.com/python/) for creating the plots. This approach allowed the display of gene expression patterns across various cell types and the representation of clustering outcomes. The resulting images were stored and presented through HTML embedding, allowing for interactive exploration and analysis of the single-cell RNA sequencing data.

Survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier curves

Patient survival data and gene or protein expression data from each dataset were utilized to create Kaplan-Meier survival plots. A Perl script developed in-house was employed to generate input files for survival analysis, which included details such as patient id, survival time (days/months), patient vital status (alive or deceased), and sample categories such as high-expression and low/medium-expression groups. Patient categorization for survival analysis was performed as previously described in Chandrashekar et al. 78. In addition, we also added 5 year and 10 year KM survival plots to this portal using the described method. To conduct multivariate analyses, clinical features such as race, sex, subtype, and grade, among others, were considered in relation to the expression and survival information. The “survival” and “survminer” packages in R were utilized for univariate and multivariate survival analyses, and statistical significance was assessed using log-rank tests (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html). Finally, in-house JavaScript Kaplan-Meier plots were created for genes in the dataset for which survival information was available.

Visualization of ChIP-seq data

To facilitate the interactive visualization of data from ChIP-seq analysis, the MammOnc-DB platform incorporated the “igv.js” JavaScript developed by the IGV team (https://github.com/igvteam/igv.js/) for peak calling. Bigwig files and broadpeak/narrowpeak files from ChIP-seq data analysis were loaded to igv.js to generate IGV plots.

Web server configuration

MammOnc-DB operates on a CentOS server that has 72 cores (Intel® Xeon® CPU E2–2699 v3 @ 2.30 GHz), 98 GB of RAM, and 22 TB HDD. To provide users with a seamless experience, the user interface of MammOnc-DB was created using PERL-CGI hosted on the Apaches webserver (https://httpd.apache.org/).

Data availability

The pre-processed data in this portal are available in the designated references. The processed data may be made available by the corresponding author to researchers on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this portal is not publicly available but may be made available by the corresponding author to researchers on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 12–49 (2024).

Łukasiewicz, S. et al. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies-an updated review. Cancers 13, 4287 (2021).

Harbeck, N. et al. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 5, 66 (2019).

Loibl, S., Poortmans, P., Morrow, M., Denkert, C. & Curigliano, G. Breast cancer. Lancet 397, 1750–1769 (2021).

Sun, Y. S. et al. Risk factors and preventions of breast cancer. Int J. Biol. Sci. 13, 1387–1397 (2017).

Provenzano, E., Ulaner, G. A. & Chin, S. F. Molecular classification of breast cancer. PET Clin. 13, 325–338 (2018).

Agostinetto, E., Gligorov, J. & Piccart, M. Systemic therapy for early-stage breast cancer: learning from the past to build the future. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 763–774 (2022).

Burguin, A., Diorio, C. & Durocher, F. Breast cancer treatments: updates and new challenges. J. Pers. Med. 11, 808 (2021).

Tsimberidou, A. M., Fountzilas, E., Nikanjam, M. & Kurzrock, R. Review of precision cancer medicine: evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat. Rev. 86, 102019 (2020).

Ahmed, Z. Practicing precision medicine with intelligently integrative clinical and multi-omics data analysis. Hum. Genom. 14, 35 (2020).

Naithani, N., Sinha, S., Misra, P., Vasudevan, B. & Sahu, R. Precision medicine: concept and tools. Med J. Armed Forces India 77, 249–257 (2021).

Dempster, J. M. et al. Chronos: a cell population dynamics model of CRISPR experiments that improves inference of gene fitness effects. Genome Biol. 22, 343 (2021).

Chandrashekar, D. S. et al. UALCAN: an update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 25, 18–27 (2022).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595 (2010).

Schettini, F. et al. Identification of cell surface targets for CAR-T cell therapies and antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. ESMO Open 6, 100102 (2021).

Bosi, C. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of antibody-drug conjugate targets and putative predictors of treatment response. Eur. J. Cancer 195, 113379 (2023).

Hernandez-Gamarra, M. et al. CARTAR: a comprehensive web tool for identifying potential targets in chimeric antigen receptor therapies using TCGA and GTEx data. Brief. Bioinf. 25, bbae326 (2024).

Cerami, E. et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2, 401–404 (2012).

Gao, J. et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal 6, pl1 (2013).

de Bruijn, I. et al. Analysis and visualization of longitudinal genomic and clinical data from the AACR project GENIE biopharma collaborative in cBioPortal. Cancer Res. 83, 3861–3867 (2023).

Goldman, M. J. et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 675–678 (2020).

Tang, Z., Kang, B., Li, C., Chen, T. & Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W556–w560 (2019).

Staaf, J. et al. RNA sequencing-based single sample predictors of molecular subtype and risk of recurrence for clinical assessment of early-stage breast cancer. NPJ. Breast Cancer 8, 94 (2022).

Saal, L. H. et al. The Sweden Cancerome Analysis Network - Breast (SCAN-B) Initiative: a large-scale multicenter infrastructure towards implementation of breast cancer genomic analyses in the clinical routine. Genome Med. 7, 20 (2015).

Aure, M. R. et al. Integrative clustering reveals a novel split in the luminal A subtype of breast cancer with impact on outcome. Breast Cancer Res. 19, 44 (2017).

Brueffer, C. et al. Clinical value of RNA sequencing-based classifiers for prediction of the five conventional breast cancer biomarkers: a report from the population-based multicenter sweden cancerome analysis network-breast initiative. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2, https://doi.org/10.1200/po.17.00135 (2018).

Creighton, C. J. The molecular profile of luminal B breast cancer. Biologics 6, 289–297 (2012).

Kessler, J. D. et al. A SUMOylation-dependent transcriptional subprogram is required for Myc-driven tumorigenesis. Science 335, 348–353 (2012).

van de Vijver, M. J. et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1999–2009 (2002).

Creighton, C. J. Gene expression profiles in cancers and their therapeutic implications. Cancer J. 29, 9–14 (2023).

Pereira, B. et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11479 (2016).

Pacini, C. et al. Integrated cross-study datasets of genetic dependencies in cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 1661 (2021).

Chen, F., Chandrashekar, D. S., Varambally, S. & Creighton, C. J. Pan-cancer molecular subtypes revealed by mass-spectrometry-based proteomic characterization of more than 500 human cancers. Nat. Commun. 10, 5679 (2019).

Monsivais, D. et al. Mass-spectrometry-based proteomic correlates of grade and stage reveal pathways and kinases associated with aggressive human cancers. Oncogene 40, 2081–2095 (2021).

Varley, K. E. et al. Recurrent read-through fusion transcripts in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 146, 287–297 (2014).

Saleh, M. et al. Comparative analysis of triple-negative breast cancer transcriptomics of Kenyan, African American and Caucasian Women. Transl. Oncol. 14, 101086 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Identification of five cytotoxicity-related genes involved in the progression of triple-negative breast cancer. Front Genet 12, 723477 (2021).

Cassetta, L. et al. Human tumor-associated macrophage and monocyte transcriptional landscapes reveal cancer-specific reprogramming, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Cancer Cell 35, 588–602.e510 (2019).

Brunner, A. L. et al. A shared transcriptional program in early breast neoplasias despite genetic and clinical distinctions. Genome Biol. 15, R71 (2014).

Bownes, R. J. et al. On-treatment biomarkers can improve prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 21, 73 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Machine learning models based on immunological genes to predict the response to neoadjuvant therapy in breast cancer patients. Front Immunol. 13, 948601 (2022).

Turnbull, A. K. et al. Unlocking the transcriptomic potential of formalin-fixed paraffin embedded clinical tissues: comparison of gene expression profiling approaches. BMC Bioinforma. 21, 30 (2020).

Barakat, T. S. et al. Functional dissection of the enhancer repertoire in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 23, 276–288.e278 (2018).

Mohammed, H. et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERα action in breast cancer. Nature 523, 313–317 (2015).

Wahdan-Alaswad, R. S. et al. Thyroid hormone enhances estrogen-mediated proliferation and cell cycle regulatory pathways in steroid receptor-positive breast Cancer. Cell Cycle, 1–20, (2023).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Garcia-Recio, S. et al. Multiomics in primary and metastatic breast tumors from the AURORA US network finds microenvironment and epigenetic drivers of metastasis. Nat. Cancer 4, 128–147 (2023).

Horak, C. E. et al. Biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide followed by ixabepilone or Paclitaxel in early-stage breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 19, 1587–1595 (2013).

Iwamoto, T. et al. Gene pathways associated with prognosis and chemotherapy sensitivity in molecular subtypes of breast cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 103, 264–272 (2011).

Hatzis, C. et al. A genomic predictor of response and survival following taxane-anthracycline chemotherapy for invasive breast cancer. Jama 305, 1873–1881 (2011).

Shen, K. et al. Cell line derived multi-gene predictor of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a validation study on US Oncology 02-103 clinical trial. BMC Med. Genom. 5, 51 (2012).

Korde, L. A. et al. Gene expression pathway analysis to predict response to neoadjuvant docetaxel and capecitabine for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 119, 685–699 (2010).

Prat, A. et al. Research-based PAM50 subtype predictor identifies higher responses and improved survival outcomes in HER2-positive breast cancer in the NOAH study. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 511–521 (2014).

Miyake, T. et al. GSTP1 expression predicts poor pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 103, 913–920 (2012).

Adusumilli, R. & Mallick, P. Data conversion with ProteoWizard msConvert. Methods Mol. Biol. 1550, 339–368 (2017).

Gomig, T. H. B. et al. High-throughput mass spectrometry and bioinformatics analysis of breast cancer proteomic data. Data Brief. 25, 104125 (2019).

De Marchi, T. et al. Proteogenomic workflow reveals molecular phenotypes related to breast cancer mammographic appearance. J. Proteome Res. 20, 2983–3001 (2021).

Tyanova, S., Temu, T. & Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 11, 2301–2319 (2016).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 (2016).

Anurag, M. et al. Proteogenomic markers of chemotherapy resistance and response in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 12, 2586–2605 (2022).

Franco, H. L. et al. Enhancer transcription reveals subtype-specific gene expression programs controlling breast cancer pathogenesis. Genome Res. 28, 159–170 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Hotspot ESR1 mutations are multimodal and contextual modulators of breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 82, 1321–1339 (2022).

Hosseinzadeh, L. et al. The androgen receptor interacts with GATA3 to transcriptionally regulate a luminal epithelial cell phenotype in breast cancer. Genome Biol. 25, 44 (2024).

Guan, J. et al. Therapeutic ligands antagonize estrogen receptor function by impairing its mobility. Cell 178, 949–963.e918 (2019).

Furman, C. et al. Covalent ERα antagonist H3B-6545 demonstrates encouraging preclinical activity in therapy-resistant breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 21, 890–902 (2022).

Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Gavish, A. et al. Hallmarks of transcriptional intratumour heterogeneity across a thousand tumours. Nature 618, 598–606 (2023).

Qian, J. et al. A pan-cancer blueprint of the heterogeneous tumor microenvironment revealed by single-cell profiling. Cell Res. 30, 745–762 (2020).

Gao, R. et al. Delineating copy number and clonal substructure in human tumors from single-cell transcriptomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 599–608 (2021).

Azizi, E. et al. Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell 174, 1293–1308.e1236 (2018).

Wu, S. Z. et al. A single-cell and spatially resolved atlas of human breast cancers. Nat. Genet. 53, 1334–1347 (2021).

Griffiths, J. I. et al. Serial single-cell genomics reveals convergent subclonal evolution of resistance as early-stage breast cancer patients progress on endocrine plus CDK4/6 therapy. Nat. Cancer 2, 658–671 (2021).

Bhat-Nakshatri, P. et al. Single-nucleus chromatin accessibility and transcriptomic map of breast tissues of women of diverse genetic ancestry. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03011-9 (2024).

Satija, R., Farrell, J. A., Gennert, D., Schier, A. F. & Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 495–502 (2015).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019).

Chandrashekar, D. S. et al. UALCAN: a portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia 19, 649–658 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the UAB Department of Pathology, and the UAB Heersink School of Medicine. S.V. and U.M. were supported by funding from U54 CA118948. C.J.C. was supported by grant CA125123. Dr. SV received support from Breast Cancer Research Foundation of Alabama (BCRFA) and U54 CA118948. We thank Harshith Kadaiah for the technical support. We thank Dr. Donald Hill from UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center for the help in editing this manuscript and Israel Ponce-Rodriguez for support in maintenance of MammOnc-DB server. We thank High-Charts (https://www.highcharts.com/) for the graphic scripts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Santhosh Kumar Karthikeyan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Darshan S. Chandrashekar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Snigdha Sahai: Validation. Sadeep Shresta: Writing – review & editing. Ritu Aneja: Writing – review & editing. Rajesh Singh: Writing – review & editing. Celina Kleer: Writing, discussions– review & editing. Harikrishna Nakshatri: Writing, discussions– review & editing. Sidharth Kumar: Writing, discussions– review & editing. Steve Qin: Writing, discussions– review & editing. Upender Manne: Writing, discussions– review & editing. Chad J. Creighton: Resources, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Sooryanarayana Varambally: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karthikeyan, S.K., Chandrashekar, D.S., Sahai, S. et al. MammOnc-DB, an integrative breast cancer data analysis platform for target discovery. npj Breast Cancer 11, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00750-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00750-x

This article is cited by

-

Sanguinarine and Doxorubicin Inhibit Heat Shock Protein HSPA5 and Trigger ER Stress in Breast Cancer

Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics (2025)

-

Variable roles of miRNA- and apoptosis-linked genes in invasive breast cancer: expression patterns, clinicopathological associations, and prognostic significance

Molecular Biology Reports (2025)