Abstract

The prognostic value of nuclear features based on tumor-associated collagen signatures (TCMF2) is still unclear. In this paper, we extracted and quantified the TCMF2 from 941 invasive breast cancer patients in H&E images. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression were used to build a TCMF2-score. The univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses showed that the TCMF2-score is an independent prognostic factor with an advantage in the prognosis of early-stage invasive breast cancer. When the TCMF2, the microscopic features of TACS-based collagen (TCMF1) and the tumor-associated collagen signatures (TACS) were combined, they showed better accuracy in patient stratification than the clinical model (CLI) or the model based on TACS + TCMF1. Our results identify that TCMF2 improves the performance of the TACS-based prediction model, and the TACS-based full model (TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2) may help us stratify patients more accurately and provide more appropriate adjuvant therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive breast cancer (IBC) is the most common malignancy affecting women’s health in the world1. The tumor microenvironment is an important factor affecting the clinical prognosis of breast cancer, in which the extracellular matrix (ECM), especially collagen, has a profound influence on breast cancer prognosis2,3,4,5,6. As an important component of ECM, collagen maintains the integrity and function of normal tissue6,7,8,9. When the tumor cells infiltrate into the stroma, the stroma structure changes, which is characterized by degradation, redeposition, crosslinking, and stiffening of the stromal collagen10,11. Thanks to recent technological advances, it is now possible to observe the morphologic changes of collagen by using second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging. Three tumor-associated collagen signatures (TACS1-3) have been observed in three-dimensional imaging of tumors in situ12. These rearrangements of collagen are considered markers of breast cancer progression, of which TACS 3 is considered to be associated with a poor disease-free survival rate (DFS) of breast cancer5. On this basis, we further found five new TACS (TACS4-8) in invasive breast cancer, in which TACS 5, 6 and 8 are associated with poor prognosis, and TACS 4 and 7 are associated with good prognosis3. Furthermore, we extracted the corresponding microscopic features of TACS-based collagen (TCMF1) and found that TCMF1 is more suitable for identifying low-risk patients, while TACS is more suitable for identifying high-risk patients4.

It is known that ductal hyperplasia may eventually develop into invasive breast cancer after undergoing ductal carcinoma in situ13, which is the result of coordination among tumor cells, stromal cells, and stromal collagen12,14,15,16,17,18. This progressively aberrant progression of breast cancer is paralleled by increasing progressive changes in nuclear features19,20,21. Changes in nuclear morphological profiles, including nuclear shape, size, or arrangement, have been proven to be a useful marker of cancer prognosis and beneficial for the selection of adjuvant therapies for different types of cancer22,23,24,25,26,27. Excitingly, with the digital development of pathology slides, several histomorphometric image analysis approaches have been developed to quantitatively characterize the changes in nuclear morphological profiles, thereby achieving more accurate risk stratification for patients. For example, Herrera-Espiñeira et al. found that malignant breast lesions can be accurately diagnosed from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images by measuring the shape, direction, and texture of breast cancer nuclei with computers28. Lu et al. constructed the oral cavity histomorphometric-based image classifier using a machine learning classifier and found that the local nuclear morphologic heterogeneity was associated with poor prognosis of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma25. Soon after, they also found that nuclear shape and orientation features from H&E images can predict survival in early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers22. In addition, Dalla et al. developed a computerized analysis method to reflect the orientation of neoplastic elements and showed that quantification of the irregularities in the orientation of nuclei was helpful in distinguishing grades of superficial papillary bladder carcinoma29. The nuclear shape, architecture and orientation features captured by morphometric-based image classifier have also been shown to be useful in predicting recurrence in node-negative gastric adenocarcinoma22,23. This begs the question of whether the nuclear features surrounding TACS can provide additional complementary information to the prognostic model of TACS and TCMF1 and provide patients with a more accurate prognosis of risk and recurrence. Fortunately, computer-based analysis of digital pathology images provides a possibility for this evaluation. The graph-based algorithm captures the spatial architecture of nodes via connected edges. The quantitative features extracted from these nuclear graphs include Delaunay Triangulation, Voronoi, Minimum Spanning Tree, and Nearest Neighbors, which summarize the distance between nuclei. The quantitative features extracted by this method proved to be useful in distinguishing prostate cancer histopathology with different Gleason grades24. Similarly, using these graph-based approaches for assessing nuclear architecture, we extracted 179 microscopic nuclear features of the tumor cells and connective cells surrounding TACS1-8 and defined them as the corresponding TACS-based nuclear feature (TCMF2), which includes 26 morphological features and 153 spatial distribution features. Studies have shown that the behavior of stromal cells is the main initial culprit leading to collagen remodeling and abnormal ECM. They can indirectly affect cancer cells through abnormal ECM. Furthermore, under the condition of abnormal ECM, the strong nuclear deformation and the resulting DNA damage may be a possible trigger for a more aggressive phenotype of breast cancer30, which suggests that the changes in nuclear morphology surrounding the abnormal ECM (e.g., TCMF2 around TACS), particularly at the boundary between tumors and normal tissue (e.g., around TACS4, 5, and 6), may inform prognosis of breast cancer. However, the prognostic value of TCMF2 is still unclear, which may bring new supplementary information on the prognosis of TACS.

In this study, we used multiphoton microscopy (MPM), which can identify signals from two-photon excited fluorescence and SHG, to locate TACS and TCMF1 from 941 patients with invasive breast cancer. Then, under the location of the MPM images, the digitized multi-regional TACS-based H&E images were obtained, and Hover-Net was subsequently used to segment, classify, extract, and quantify the TCMF2 in H&E images (Fig. 1). This multi-regional nuclear feature can provide additional prognostic information for the predictive model of TACS, helping us more accurately stratify patients.

TACSs were visually examined on MPM images and calculated the TACS-score. The TCMF1 was extracted from SHG images and LASSO regression was used to calculate the TCMF1-score. The TCMF2 was extracted from digitized H&E images and LASSO regression was used to calculate the TCMF2-score. Then, the three scores were combined for a series of prognostic analyses.

Results

Identification of TACS-based nuclear features and construction of the prognostic model

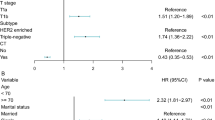

Our previous results suggested that TACS-score and TCMF1-score are powerful independent prognostic biomarkers of breast cancer3,4. To clarify the prognostic value of TCMF2, we performed the LASSO regression on the 179 candidate TCMF2 features in the training cohort and captured 17 robust TCMF2 features associated with prognosis (Supplementary Fig. S1a and Supplementary Table S1). We found that multiple TACS patterns might be present in one patient and one TACS pattern might exist in multiple patients. When one TACS pattern exists in multiple patients, variations of some TCMF2 features might exist among patients. In contrast, when multiple TACS patterns existed in one patient or when one TACS pattern existed in multiple regions of one patient, the variation of the TCMF2 features might be small among the ROIs. Figure 2 shows a multivariate association of 17 TCMF2 features with DFS. TCMF2-19 and TCMF2-167 were risk factors for DFS, while TCMF2-18, TCMF2-22, TCMF2-62, TCMF2-112 and TCMF2-165 were protective factors for DFS (Supplementary Table S1). The results suggested that changes in the TCMF2, especially the morphological features and the spatial distribution of connective cells, may play a role in the recurrence of breast cancer. An ensemble of the 17 robust TCMF2 features remained with individual coefficients, which were integrated to build a TCMF2 prognostic signature (TCMF2-score) (Supplementary Fig. S1b). A correlation network involving the 17 robust TCMF2 and the TCMF2-score in the training cohort was shown in Supplementary Fig. S1c. To better understand the biological concepts, we performed K-means clustering (k = 2) on the samples based on the 17 nuclear features. The resulting scatter plot, visualized after PCA reduction, colors each point by its sample-level cluster assignment. According to the expression pattern of TCMF2 features, two different groups in the samples were revealed (Cluster 1 and Cluster 2) (Supplementary Fig. S2). To explain the biological meaning of the changes in the combination patterns of TCMF2 between clusters, we conducted heat map visualization (Supplementary Fig. S3) and examined the centroid values of all 17 features within each cluster (Supplementary Table S2). The table of centroid values provides a basis for interpreting the distinct biological states represented by each cluster. The result of the heatmap revealed that two clusters exhibited opposite expression patterns in TCMF2 feature values. Cluster 1 showed a combination of abnormally high expression of TCMF2-64, TCMF2-115, TCMF2-116 and TCMF2-167, along with abnormally low expression of TCMF2-19, TCMF2-22, TCMF2-29 and TCMF2-160. In contrast, Cluster 2 displayed relatively moderate TCMF2 feature expression levels, close to the average, but with low expression of TCMF2-64, TCMF2-115, TCMF2-116 and TCMF2-167, and high expression of TCMF2-19, TCMF2-22, TCMF2-29 and TCMF2-160 (a pattern exactly opposite to that of Cluster 1). The opposite TCMF2 feature expression patterns between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 revealed two biologically distinct populations.

The TCMF2-score is a robust prognostic tool for breast cancer

TCMF2-score for each patient was calculated in three cohorts, and patients were divided into low- and high-risk groups according to the cutoff value in the training cohort (Supplementary Fig. S1d). Subsequently, the risk curve and scatter plot were generated to display the risk score and the DFS status of each breast cancer patient. The risk coefficient and recurrence rate in the low-risk group were lower than those in the high-risk group (Fig. 3a, b). The color bar of the heatmap also showed the relationship between the risk scores and DFS, i.e., a lower risk score was associated with a better prognosis, while a higher risk score was associated with a worse prognosis, not only in the training cohort but also in the internal and external validation cohorts (Fig. 3c). Figure 3d shows the distribution of DFS in the low- and high-risk groups in three cohorts. As expected, a higher TCMF2-score was significantly correlated with shorter DFS. The medians and interquartile range (IQR) of DFS in the low-risk group were 77.0 (IQR 64.75–84.0) months in the training cohort, 76.0 (IQR 62.0–84.0) months in the internal validation cohort and 80.0 (IQR 66.25–81.0) months in the external validation cohort, respectively, while those in the high-risk group were 51.0 (IQR 21.0–82.0) months in the training cohort, 63.0 (IQR 21.0–80.0) months in the internal validation cohort and 59.0 (IQR 24.0–80.0) months in the external validation cohort, respectively.

a Distribution of TCMF2-score in the training cohort. b The scatter plot of the patient disease-free survival overview in the training cohort. c The heatmap showed the relationship between the TCMF2-score and DFS in three cohorts. d Distribution of DFS in the low- and high-risk groups in three cohorts. e Kaplan–Meier survival analysis based on TCMF2-score demonstrated that patients with higher TCMF2-score exhibited worse 5-year DFS in three cohorts. P values were calculated using the log-rank test. f ROC analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of the 5-year DFS for the TCMF2-score in three cohorts.

The correlation analysis also showed that the TCMF2-score had a significant negative correlation with the DFS, indicating that the DFS gradually decreased with an increasing TCMF2-score (Supplementary Fig. S4). Surprisingly, there was a relatively clear boundary at 5 years in the three cohorts (Fig. 3c). The bar longer than 5 years was mostly blue with a good prognosis, while the bar shorter than 5 years was mostly red with a poor prognosis, which suggested that 5 years was a key time node for disease-free survival in breast cancer. Therefore, the Kaplan–Meier method was employed for the 5-year survival analysis in the low- and high-risk groups. As shown in Fig. 3e, the result demonstrated that patients with higher TCMF2-score exhibited worse 5-year DFS in the three cohorts. The 5-year DFS in the low-risk group was 85.9% (95% CI, 80.6–91.2%) in the training cohort, 80.0% (95% CI, 73.9–86.1%) in the internal validation cohort, and 89.0% (95% CI, 82.9–95.1%) in the external validation cohort. By comparison, the 5-year DFS in the high-risk group was relatively shorter than that in the low-risk group, and the 5-year DFS in the high-risk group was 41.1% (95% CI, 34.0–48.2%) in the training cohort, 53.3% (95% CI, 45.9–60.7%) in the internal validation cohort and 48.7% (95% CI, 40.7–56.7%) in the external validation cohort. The predictive ability of the TCMF2-score for the 5-year DFS was measured according to the ROC curve analysis, and a relatively satisfactory result was obtained in three cohorts (Fig. 3f).

The univariate Cox analysis revealed that the TCMF2-score was significantly associated with DFS in the training, internal and external validation cohorts (Table 1, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). When all risk factors were adjusted by multivariate Cox regression analysis, the TCMF2-score was also retained as an independent prognostic factor for DFS in all three cohorts (Table 1, Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

TCMF2-score improves the predictive performance of TACS

When TCMF2 was combined with TACS and TCMF1, the AUC of TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 was better than the model based on CLI, TACS + TCMF1 or TCMF2 in three cohorts (Fig. 4), showing better predictive performance (Supplementary Table S5). Supplementary Table S6 showed the risk stratification of TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 based on clinical characteristics in three cohorts, highlighting its general applicability. We combined all cohorts into 941 patients to conduct a subgroup analysis classified by clinical variables. The result showed that the predictive ability of the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model was generally good for all patients. Especially for patients in the early stage (tumor size ≤2 cm, nodal status negative, stage I at diagnosis), the improvement of its predictive ability was more prominent (Supplementary Table S7). Unsurprisingly, the HR of the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model was also higher than that of the model based on CLI, TACS + TCMF1 or TCMF2 in three cohorts (Fig. 5). In addition, the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model showed a better prediction accuracy than the model of TACS + TCMF1. Among a total of 941 patients, the predictive accuracy of the model based on TACS + TCMF1 was 78.9%. After combining with TCMF2, the predictive accuracy of the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 prognostic model was increased to 82%.

When the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model was combined with the CLI model based on clinical variables such as age, molecular subtype, tumor size, nodal status, clinical stage, histological grade, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, the full model (CLI + TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2) achieved the best prognostic performance and further stratifies the low- and high-risk patients with prominent HR (Figs. 4, 5 and Supplementary Fig. S5) in the three cohorts. The AUC of the full model was 0.926, 0.912 and 0.887 in the training, internal validation and external validation cohorts, respectively, which was the highest predictive performance among the five types of prediction models.

Clinical applications

A clinically applicable nomogram incorporating the TCMF1 signature, TCMF2 signature, TACS signature various independent clinical risk factors based on multivariate Cox analysis with stepwise selection was established in the training cohort (Supplementary Fig. S6a). The calibration curve of the nomogram demonstrated positive agreement between prediction and observation in the three cohorts (Supplementary Fig. S6b).

The decision curve analysis of the CLI model, TACS + TCMF1 model, TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model and CLI + TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model was also shown in Supplementary Fig. S6c. We found that after adding prognostic information about TCMF2, the full model (CLI + TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2) achieved the highest net benefit among the four parameters.

The correlation between TCMF2 and TCMF1

Canonical correlation analysis also assessed the correlation between 17 robust TCMF2 features and the 8 morphological features of TCMF131. In the canonical correlation analysis on morphological features of collage and the morphological features of connective cells (the first category in TCMF2), two canonical functions with significant differences were extracted from the training cohorts, one from the internal validation cohort and one from the external validation cohort, respectively (Supplementary Table S8). The result unveiled that in the forming U1, eccentricity (TCMF2-18) is the most dominant subdimension compared with other variables, while the collagen proportionate area (Y1) is the most important subdimension in the forming of V1, showed that the collagen proportion area is positively related to the eccentricity of connected cells since the pairs of variables are characterized by standardized canonical coefficients with the same signs. The same results also exist in both internal and external validation cohorts. In the canonical correlation analysis on morphological features of collage and spatial distribution of all cells (the second category in TCMF2), one canonical function with significant differences was extracted from the training, internal validation and external validation cohort, respectively (Supplementary Table S9). The result unveiled that in the forming U1, the feature of the “disorder of distance to 7 nearest neighbors” (TCMF2-62) is the main dominant subdimension compared with other variables, while the feature of “collagen fiber number” (Y2) is the most important subdimension in the forming of V1, showing that the collagen fiber number is positively related to the feature of “disorder of distance to 7 nearest neighbors”. In the canonical correlation analysis on morphological features of collage and spatial distribution of tumor cells (the third category in TCMF2), no canonical function with significant differences was extracted in either the training, internal validation, or external validation cohort. In addition, in the canonical correlation analysis on morphological features of collage and spatial distribution of connective cells (the fourth category in TCMF2), although two canonical functions with significant differences are extracted from the training and internal validation cohort respectively, no canonical function with significant difference is extracted from the external validation cohorts, indicating that the canonical functions extracted from the training and internal validation cohorts were not stable (Supplementary Table S10). These results, namely the eccentricity of connected cells was positively correlated with the collagen proportion area and the disorder of distance to 7 nearest neighbors of all cells (tumor cells and connective cells) was positively correlated with the collagen fiber number, not only in the training cohort but also in the internal and external validation cohorts, indicate that the changes in TCMF1 were synergistic with the changes in TCMF2 during breast cancer progression.

Discussion

Breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease. Overt phenotypic differences between individuals can help explain their varying susceptibilities to diseases, the ways in which they manifest diseases and the large differences in response to the same standardized treatment32. The success of precision medicine relies on an accurate assessment of the prognosis and risk stratification for each patient. Although traditional prognostic methods, such as stage or molecular subtype, can meet the requirements of prognostic judgment and treatment decisions for most patients, overtreatment or undertreatment is prevalent in patients in the middle zone. Therefore, how to improve the accuracy of patient stratification has been a huge challenge for clinicians.

Currently, some multigene assays provide significant information on tumor heterogeneity, which provides practical clinical solutions for undertreatment or overtreatment33,34. Different from the multigene assays, our study reflects tumor heterogeneity and predicts tumor development outcomes based on the ECM, where tumor progression is always accompanied by collagen changes in the ECM. Based on this, we used the MPM technology and proposed the concepts of TACS (macroscopic pattern of collagen), TCMF1 (microscopic signature of collagen fibers) and TCMF2 (microscopic signature of nuclear) with collagen patterns as the core. Together, they constitute complete TACS-based prognostic information from the target region. Similar to TACS and TCMF1, TCMF2 is also an independent prognostic factor and has superior stratification ability in patients with early-stage IBC, especially in patients with tumor size ≤ 2 cm, negative lymph nodes, and stage I at diagnosis (Supplementary Table S7). This may be related to the fact that information from cells and collagen communicates with each other to promote the formation of macroscopic TACS patterns in the early stages of the disease. Our research has demonstrated the strong prognostic ability of TCMF2, which is superior to other clinical variables (Supplementary Fig. S7). When TCMF2 was combined with TACS + TCMF1, TCMF2 provided the information from cells, and TACS + TCMF1 provided the information from collagen. This complete information, based on TACS, improves the prognostic accuracy of the individual model.

Traditionally, nuclear shape and architecture are extracted from the whole digital H&E image. However, averaging the whole digital H&E data may lose important information about tumor heterogeneity, especially for those with strong regional characteristics. We believe that the changes in nuclear features only near the TACS may more accurately reflect the relationship between cells and collagen fibers. The results are also convincing that only the morphology feature and spatial distribution of the connective cells, not those of the tumor cells, were significant risk factors for DFS in the prognosis of TCMF2. The development of tumors is associated with increased stiffness in the ECM and nuclear remodeling of connected cells (mostly fibroblasts)35,36. Langevin et al. found that the mechanical contraction force on the connecting cells generated by the increased stiffness in the ECM may lead to nuclear remodeling, and the nuclear remodeling and loss of nuclear concavity can further influence cell differentiation, chromatin remodeling, histone acetylation and gene expression37,38,39,40. Moreover, the changes in cell shape, driven by gene expression and/or mechanical forces, can promote breast cancer progression by a “shape-gene network“41. In addition, differences in the spatial distribution of nuclear between the benign tissue of recurrent patients and non-recurrent patients have also been demonstrated24. Our research results also confirmed this point (Fig. 2). Consistent with Langevin’s results, our results also found that an increase in the convex area of connective cells was associated with poor prognosis. Furthermore, the average number of nearest neighbors within a 30 pixel radius, a nuclear feature that reflects the variance in spatial proximity of connective cells, has also been found to be associated with poor prognosis, which further confirmed from the side that changes in the morphology and spatial distribution of connective cells near TACS may play a more important role than tumor cells in promoting the formation of TACS patterns and cancer progression.

To understand the relationship between TCMF1 and TCMF2, a multivariate perspective is examined. We found that the eccentricity of connective cells (mostly fibroblasts) was positively correlated with the collagen proportion area. Eccentricity is a measure of how elongated the nuclear are. The increase in eccentricity reflects a shift in cell shape from round to fusiform42,43,44. The nuclear deformation can alter protein production, including collagen45,46. Similarly, in this paper, the nuclear deformation of connective cells correlates with the formation of collagen fibers. Furthermore, the disorder of distance to 7 nearest neighbors of all cells (tumor cells and connective cells), a nuclear feature that reflects the nuclear architectural disorder, was positively correlated with the collagen fiber number, suggesting that tumor cells may have invaded the TACS region and thus led to the intermixing of multiple cells. The shape and spatial arrangement of the TASC-based nucleus store retrievable information about the early changes in TACS. Therefore, TCMF2 can supplement some information on TACS-based cell heterogeneity to improve the prognostic accuracy of TACS. As for why TCMF2 can identify patients with high and low risks, we hypothesize that within TACS regions, there exist two distinctly opposite combinatorial expression patterns of TCMF2 features between patients with high-risk and low-risk groups. The biological functions of the abnormally expressed feature values in Cluster 1 were primarily associated with alterations in stromal cell morphology (reduced size and softer texture) and changes in their spatial distribution (increased dispersion or localized clustering), accompanied by enhanced tumor cell aggregation and an overall increase in cell density. The feature pattern of Cluster 1 is both coordinated and extreme, potentially representing a biologically active and specific state, depicting a landscape of tumor microenvironment (TME) remodeling characterized by activated stromal cells and proliferating tumor cells. This feature pattern of Cluster 1 may be associated with poor prognosis. In contrast, the majority of feature values in Cluster 2 fluctuate relatively subdued and close to the average level, without forming a highly consistent pattern, potentially indicating a more quiescent and conservative cellular state. This feature pattern of Cluster 2 is often associated with a more favorable prognosis. This demonstrates that the prognostic power of our model stems from distinct biological processes represented by the composite patterns of these features.

The biggest advantage of our study is the establishment of collagen multi-patterns by MPM, which provides a guarantee for the accurate identification of macroscopic collagen patterns. Under this premise, we simultaneously targeted segments and classified nuclear only in multi-region collagen images to obtain the relevant information on the formation of collagen, while discarding the interference of cell information in irrelevant regions. This is different from the traditional approach of segmenting and classifying nuclear in whole H&E images. This study extends our previous studies on TACS and TCMF1 to TACS-based cells and highlights the importance of connective cells during collagen morphological changes. By extracting and quantifying the targeted features of TCMF2, it may be helpful to shed important light on the underlying biological pathways that drive tumorigenesis. In addition, our study possesses significant clinical translational value. Firstly, the addition of TCMF2 information enhances the prognostic stratification ability of TACS, enabling the identification of high-risk patients who may benefit from more aggressive or tailored treatments. Secondly, the instruments used to acquire TACS, TCMF1, and TCMF2 features are highly compatible with standard histology, allowing implementation without disrupting routine histological workflows in future prospective studies. Third, compared to the high sample quality requirements and substantial costs associated with multigene assays, the TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 model imposes lower demands on samples. Routine paraffin-embedded sections are sufficient for the model detection. Furthermore, samples used for model detection are suitable for storage, transportation, and retesting. This low-cost detection method endows the models with strong potential for clinical popularization, particularly in developing cities with relatively limited economic resources, where they effectively bridge the gap left by the impracticality of multi-gene testing due to its high cost. With in-depth research on machine learning-based automated classification of TACS, these models are expected to enable automated clinical analysis and quantification, thereby facilitating their clinical translation in these cities. We acknowledge that our manual, hypothesis-driven ROI selection strategy, while essential for targeting biologically relevant microstructures based on our current understanding, may introduce an element of subjectivity. However, we posit that this approach strengthens the model’s ability to capture specific biological signals rather than general tissue features. Although the field of view is limited, the limited field of view is a trade-off for achieving high-resolution analysis of specific collagen features. Our multi-ROI sampling approach, where the number of ROIs is dictated by the tumor’s inherent biological heterogeneity, is designed to counter this limitation and provide a more representative profile of the tumor microenvironment. While a more scalable approach than manual annotation is needed for broader clinical application, the manually selected ROI dataset at this stage will serve as a high-quality training set for developing automated machine learning or deep learning algorithms in subsequent work. This will facilitate the potential integration of a future automated tool into the digital pathology workflow, enabling efficient and robust whole-slide analysis. We also acknowledge that the retrospective nature of our study is an inevitable limitation. For this reason, we included as many datasets as possible for rigorous validation. We have to acknowledge the fact that sampling bias can only be reduced, but not eliminated. Therefore, a large-scale, multi-center prospective cohort study is necessary before clinical translation to validate our model, which would confirm its robustness and generalizability.

In summary, this study demonstrated that TCMF2 is an independent prognostic factor, and the TACS-based full model (TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2) may help us stratify patients more accurately and provide more appropriate adjuvant therapy.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Approval Number: 2020KJT010) and Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital (Approval Number: KY2020-11). Due to the nature of retrospective study, the need for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujian Medical University Union Hospital and Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and research participants, material, or data have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 941 patients were used to analyse, including 689 patients from Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, who were randomly divided into the training cohort (355 cases) and the internal validation cohort (334 cases), and 252 patients from Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital as the external validation cohort (Supplementary Fig. S8). The sample inclusion criteria were: (1) patients had pathologically confirmed IBC without distant metastasis and underwent surgical resection; (2) patients were not treated with preoperative therapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy). The baseline characteristics of the patients in the three cohorts are shown in Supplementary Table S11.

Sample preparation

Two serial sections (5 μm) were obtained from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue biospecimens. One for H&E stained and whole-slide images were digitized at ×40 magnification using a digital whole-slide scanner (VM1000, Motic). Another deparaffinized and unstained section was used for MPM imaging using a commercial laser-scanning microscope (LSM 880, Zeiss, Germany) at ×20 magnification.

TACS-related signatures establishment

The quantitative scheme of TACS1-8 and TCMF1 has been described in detail in the previously published paper3,4. Simply, according to the size of samples, 7–20 non-overlapping regions containing TACS are marked on H&E images, and each region is approximately 2.8 mm × 2.8 mm. Subsequently, the TACS1-8 pattern of all marked regions was confirmed on the MPM images by three independent reviewers who did not know the pathological outcomes (Supplementary Fig. S9)3. Next, a region of interest (ROI) with a field of approximately 150 μm × 150 μm was identified from each TACS pattern in the SHG image (Supplementary Fig. S9). A total of 142 microscopic collagen features (8 morphological features and 134 texture features) were extracted and quantified using MATLAB 2016b. For each patient, all ROIs from each patient were averaged. After the data were normalized, the most robust microscopic features were screened to form the TCMF1-score4.

The extraction of TCMF2 was performed on the digitized H&E image. To accurately obtain the most biologically relevant organizational structures, which encompass the defined collagen spatial features and represented critical sites of tumor-stromal interaction and tumor heterogeneity, for each patient, an ROI with a field of 180 μm × 180 μm was intercepted from each TACS pattern. This is the minimum size to fully show the unique spatial structure of TACS1-847. All ROI were visually inspected as part of the preprocessing pipeline. Regions exhibiting gross artifacts (e.g., tissue folds, tears, staining artifacts, pen marks), scanner/focus problems, or poor tissue coverage were identified and excluded. The corresponding ROIs were manually checked and only well-aligned ROIs with clear tumor-stroma boundaries were selected to ensure the colocalization of TACS regions from H&E images with those on MPM images. The intercepted ROI included half of the tumor tissue and half of the stroma tissue near the TACS (Supplementary Fig. S9), enabling it to simultaneously accommodate information on TACS patterns, tumor cells, and stromal cells. Hover-Net was used to simultaneously segment and classify nuclear in H&E images (Supplementary Fig. S10)32. Based on the results of nuclear segmentation and classification, corresponding features were extracted and quantified from two types of cells, one was tumor cells and the other was connective cells, which included fibroblasts, endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, fibers, and adipocytes. The extracted TCMF2 includes: (1) Morphological features: A total of 26 morphological features, such as area, perimeter, main axis length, minor axis length, eccentricity, convex area, orientation, equiv diameter, solidity, extent, compactness, ellipse_X and ellipse_Y were extracted from tumor cells and connective cells respectively to capture shape-related disorders in the local cluster regions around TACS (Supplementary Table S12). (2) Spatial distribution features: A total of 153 spatial distribution features, with 36 features from the Voronoi Diagrams, 24 features from the Delaunay Triangles, 12 features from the Minimum Spanning Trees, and 81 features from Nearest Neighbors, were extracted from tumor cells, connective cells and all cells (tumor cells and connective cells) aimed to capture the nuclear architectural disorder in TACS regions indicating more aggressive tumor behaviors (Supplementary Table S13).

Hover-Net outputs (nuclear masks and cell-type labels) were post-processed to remove small debris and correct overlapping segmentations. All ROIs were visually inspected and any ROI showing poor segmentation or severe misclassification was excluded from downstream feature extraction. For each patient, all ROIs were averaged. After the data were normalized, the most robust nuclear features were screened by LASSO regression model analysis to form TCMF2-score, whose linear combination formula was weighted by their respective Cox regression coefficients.

Statistical analysis

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm combined with the Cox survival model was used to analyze the association between each TCMF2 feature and DFS in the training cohort. The R package “glmnet” was used to perform the LASSO Cox regression model analysis and to screen the most robust TCMF2 feature. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted using the prcomp() function in R to extract the most important variation patterns in the TCMF2 feature. Cluster analysis was then performed on the standardized original data using the K-means algorithm via the kmeans() function in R to identify the intrinsic and unknown population structure in the data. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to measure the correlation between the screened features and 5-year DFS. The features screened by LASSO regression were linearly combined to form the TCMF2-score. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was applied to calculate the relative weight of each score (TACS-score, TCMF1-score, TCMF2-score, CLI-score), and then the scores and their relative weights were linearly combined to establish a comprehensive prognosis score (TACS + TCMF1, TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 and CLI + TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2). A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the sensitivity and specificity of comprehensive prognosis scores. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was measured to assess the prognostic accuracy. All scores, including TACS-score, TCMF1-score, TCMF2-score, CLI-score, TACS + TCMF1, TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2 and CLI + TACS + TCMF1 + TCMF2, were developed in the training cohort and then applied to internal and external validation cohorts. In this study, the training cohort and the internal validation cohort came from a hospital in southern China, while the external validation cohort came from another hospital in northern China, 2900 km away, making their data strictly separated. The survival net benefits of scores were estimated with decision curve analysis (DCA). The maximum Youden index (J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) from the ROC curve was used to find the optimal cutoff value and separate patients into low-risk and high-risk groups in the training cohort, and then, the same cutoff value was applied to the validation cohorts. This data-driven approach aims to find the cutoff that best balances the model’s ability to correctly identify both high-risk groups (sensitivity) and low-risk groups (specificity), rather than relying on an arbitrary or subjective value. The predictive accuracy of the TCMF2-score and comprehensive prognosis scores was analyzed in the training cohort, and validated in internal and external validation cohorts.

Our primary endpoint was 5-year DFS. We calculated the DFS as the time from the date of diagnosis to the first recurrence of the disease, the date of death, the date last known to have no evidence of disease or the date of the most recent follow-up.

5-year DFS was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test, and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated using a univariate Cox regression analysis. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis were used for choosing independent predictors, and a nomogram was established by the independent predictors to generate a comprehensive indicator for assessing 5-year DFS. The performance of the nomogram was evaluated via discrimination and calibration. A concordance index (C-index) was calculated via a bootstrap method with 1000 resamples. The patient population was about 20 events per variable in this study, which well surpassed the minimum of 10 events per variable (EPV) to obtain a reliable prediction model (a generally accepted rule of thumb). All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values of less than 0.05 were deemed significant. Statistical analyses were done in R (version 4.0.5) and SPSS (version 25.0).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Hu, D. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in breast cancer: challenges and opportunities. Cancer Commun. 42, 401–434 (2022).

Xi, G. et al. Large-scale tumor-associated collagen signatures identify high-risk breast cancer patients. Theranostics 11, 3229–3243 (2021).

Xi, G. et al. Computer-assisted quantification of tumor-associated collagen signatures to improve the prognosis prediction of breast cancer. BMC Med. 19, 273 (2021).

Conklin, M. W. et al. Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1221–1232 (2011).

Gole, L. et al. Quantitative stain-free imaging and digital profiling of collagen structure reveal diverse survival of triple negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 42 (2020).

Nissen, N. I., Karsdal, M. & Willumsen, N. Collagens and cancer associated fibroblasts in the reactive stroma and its relation to cancer biology. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 115 (2019).

Keely, P. J., Wu, J. E. & Santoro, S. A. The spatial and temporal expression of the α 2 β 1 integrin and its ligands, collagen I, collagen IV, and laminin, suggest important roles in mouse mammary morphogenesis. Differentiation 59, 1–13 (1995).

Conklin, M. W. & Keely, P. J. Why the stroma matters in breast cancer: insights into breast cancer patient outcomes through the examination of stromal biomarkers. Cell Adhes. Migr. 6, 249–260 (2012).

Maller, O. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages drive stromal cell-dependent collagen crosslinking and stiffening to promote breast cancer aggression. Nat. Mater. 20, 548–559 (2021).

Acerbi, I. et al. Human breast cancer invasion and aggression correlates with ECM stiffening and immune cell infiltration. Integr. Biol. 7, 1120–1134 (2015).

Tan, Z. et al. Mapping breast cancer microenvironment through single-cell omics. Front. Immunol. 13, 868813 (2022).

Lakhani, S. R. The transition from hyperplasia to invasive carcinoma of the breast. J. Pathol. 187, 272–278 (1999).

Binnewies, M. et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 24, 541–550 (2018).

Kenny, T. et al. Patient-derived interstitial fluids and predisposition to aggressive sporadic breast cancer through collagen remodeling and inactivation of p53. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 5446–5459 (2017).

Provenzano, P. P. et al. Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 4, 38 (2006).

Xu, S. et al. The role of collagen in cancer: from bench to bedside. J. Transl. Med. 17, 309 (2019).

Wen, S. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-derived IL32 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis via integrin β3-p38 MAPK signaling. Cancer Lett. 442, 320–332 (2019).

Mariuzzi, G. M. et al. Quantitative study of ductal breast cancer progression. Morphometric evaluation of phenotypical changes occurring in benign and preinvasive epithelial lesions. Pathol. Res. Pract. 190, 1056–1065 (1994).

Ruiz, A., Almenar, S., Callaghan, R. C. & Llombart-Bosch, A. Benign, preinvasive and invasive ductal breast lesions. A comparative study with quantitative techniques: morphometry, image- and flow cytometry. Pathol. Res. Pract. 195, 741–746 (1999).

Mommers, E. C. et al. Nuclear cytometric changes in breast carcinogenesis. J. Pathol. 193, 33–39 (2001).

Lu, C. et al. Nuclear shape and orientation features from H&E images predict survival in early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Lab Investig. 98, 1438–1448 (2018).

Ji, M. Y. et al. Nuclear shape, architecture and orientation features from H&E images are able to predict recurrence in node-negative gastric adenocarcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 17, 92 (2019).

Lee, G. et al. Nuclear shape and architecture in benign fields predict biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer patients following radical prostatectomy: preliminary findings. Eur. Urol. Focus. 3, 457–466 (2017).

Lu, C. et al. An oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma quantitative histomorphometric-based image classifier of nuclear morphology can risk stratify patients for disease-specific survival. Mod. Pathol. 30, 1655–1665 (2017).

Nakashima, Y. et al. Nuclear atypia grading score is a useful prognostic factor in papillary gastric adenocarcinoma. Histopathology 59, 841–849 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. Prediction of recurrence in early stage non-small cell lung cancer using computer extracted nuclear features from digital H&E images. Sci. Rep. 7, 13543 (2017).

Herrera-Espiñeira, C., Marcos-Muñoz, C. & López-Cuervo, J. E. Diagnosis of breast cancer by measuring nuclear disorder using planar graphs. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 19, 519–523 (1997).

Dalla, P. P. et al. Grading in superficial papillary bladder carcinoma, with an emphasis on nuclear orientation. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 18, 305–308 (1996).

Riedl, P. et al. Phenotype switching of breast cancer cells upon matrix interface crossing. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 15, 24059–24070 (2023).

Graham, S. et al. Hover-Net: simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images. Med. Image Anal. 58, 101563 (2019).

Goetz, L. H. & Schork, N. J. Personalized medicine: motivation, challenges, and progress. Fertil. Steril. 109, 952–963 (2018).

Giuliano, A. E. et al. Breast cancer-major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 67, 290–303 (2017).

Vissio, E. et al. Integration of Ki-67 index into AJCC 2018 staging provides additional prognostic information in breast tumours candidate for genomic profiling. Br. J. Cancer 122, 382–387 (2020).

Bera, K., Kiepas, A., Zhang, Y., Sun, S. X. & Konstantopoulos, K. The interplay between physical cues and mechanosensitive ion channels in cancer metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 954099 (2022).

Butcher, D. T., Alliston, T. & Weaver, V. M. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 108–122 (2009).

Langevin, H. M. et al. Tissue stretch induces nuclear remodeling in connective tissue fibroblasts. Histochem. Cell Biol. 133, 405–415 (2010).

Kim, Y. B. et al. Cell adhesion status-dependent histone acetylation is regulated through intracellular contractility-related signaling activities. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28357–28364 (2005).

Titus, L. C., Dawson, T. R., Rexer, D. J., Ryan, K. J. & Wente, S. R. Members of the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex are required for maintaining proper nuclear envelope structure and pore complex localization. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 1072–1087 (2010).

McKinley, K. L. et al. Cellular aspect ratio and cell division mechanics underlie the patterning of cell progeny in diverse mammalian epithelia. Elife 7, e36739 (2018).

Sailem, H. Z. & Bakal, C. Identification of clinically predictive metagenes that encode components of a network coupling cell shape to transcription by image-omics. Genome Res. 27, 196–207 (2017).

Rangamani, P. et al. Decoding information in cell shape. Cell 154, 1356–1369 (2013).

Tocco, V. J. et al. The nucleus is irreversibly shaped by motion of cell boundaries in cancer and non-cancer cells. J. Cell Physiol. 233, 1446–1454 (2018).

Woodley, J. P., Lambert, D. W. & Asencio, I. O. Understanding fibroblast behavior in 3D biomaterials. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 28, 569–578 (2022).

Thomas, C. H., Collier, J. H., Sfeir, C. S. & Healy, K. E. Engineering gene expression and protein synthesis by modulation of nuclear shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 1972–1977 (2002).

Wang, K. et al. Nanotopographical modulation of cell function through nuclear deformation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 5082–5092 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. Teamwork quality and health workers burnout nexus: a new insight from canonical correlation analysis. Hum. Resour. Health 20, 52 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of Chen lab for their suggestions and critical feedback. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82572282, 82171991, 81700576), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2024J02013, 2024J01624, 2023J01504, 2023J011125).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. (Jianhua Chen), S.X. (Shuoyu Xu) and J.C. (Jianxin Chen) conceived the idea and supervised the study. Z.L., G.X., and L.Z. performed multiphoton imaging. D.K., J.M., W.G., F.F., Q.Z., and C.W. were responsible for sample collection and preparation. J.C., Z.L., S.X., L.L., L.Q., X.H., and S.X. (Shunwu Xu) conducted data analysis. J.C. (Jianhua Chen), Z.L., and J.C. (Jianxin Chen) interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the article and approved the final submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Kang, D., Wang, C. et al. Prognostic value of nuclear features based on tumor-associated collagen signatures in breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 11, 148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00860-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-025-00860-6