Abstract

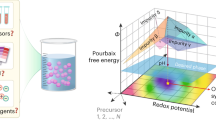

In this work, using the SCAN functional, we develop a simple method on top of the Materials Project (MP) Pourbaix diagram framework to accurately predict the aqueous stability of solids. We extensively evaluate the SCAN functional’s performance in computed formation enthalpies for a broad range of oxides and develop Hubbard U corrections for transition-metal oxides where the standard SCAN functional exhibits large deviations. The performance of the calculated Pourbaix diagram using the SCAN functional is validated with comparison to the experimental and the MP PBE Pourbaix diagrams for representative examples. Benchmarks indicate the SCAN Pourbaix diagram systematically outperforms the MP PBE in aqueous stability prediction. We further show applications of this method in accurately predicting the dissolution potentials of the state-of-the-art catalysts for oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predicting aqueous stability of solids is of central importance to materials development for electrochemical applications such as fuel cells, electrolyzers, and Li-air batteries1,2,3,4. The electrode potential-pH (aka. Pourbaix) diagram maps the most stable species in an aqueous environment and has become an invaluable tool in evaluating aqueous stability. Hansen et al.1 developed the concept of surface Pourbaix diagram to identify the most stable surface of metal cathodes under the operating conditions of oxygen reduction reaction. Persson et al.2 proposed an efficient scheme unifying the Gibbs free energies of ab initio calculated solids and the experimental aqueous ions for the Pourbaix diagram construction. The advent of large computational material databases (e.g., the Materials Project (MP)) has enabled high-throughput screening of materials of interest in terms of their aqueous stability3,4,5,6. Nevertheless, aqueous stability screening based on the current implementation of the MP Pourbaix diagram2,5 leads to some unexpected inaccuracies. One example is selenium dioxide (SeO2), which is incorrectly predicted to be stable in acid and water7. This qualitative inconsistency occurs in that the corrected formation energy of SeO2 is an outlier in the MP data, exhibiting a large error (1.18 eV per formula unit). In the MP, a correction of 1.40 eV/O2 is used for oxide compounds to calibrate the error in calculated formation energy, arising from the overestimated O2 binding energy in the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional8. Though this approach significantly improves the accuracy of computed formation energies and phase diagrams overall, large deviations can persist for many compounds like selenium (See Supplementary Fig. 1), which may affect predicted positions of equilibrium lines on the pourbaix diagram.

Since the spread of this error, even when systematically correcting formation energies, may have an impact on the positioning of aqueous phase equilibria, improving the overall accuracy of the physical methods to calculate formation energy of solids can significantly improve the reliability of aqueous stability prediction. Recently, the strongly constrained and appropriately normed (SCAN) functional has demonstrated such an improvement accuracy in both energetics and geometries9,10,11,12. Specifically, Zhang et al.12 demonstrated that the formation energies of 196 binary compounds using the SCAN functional reduce the mean absolute error (MAE) to 0.1 eV/atom, halving that of the PBE functional. This remarkable improvement is attributed to its satisfaction of all known exact constraints applicable to a semilocal functional9,10. The SCAN functional still has difficulties in accurately predicting the formation energy for transition-metal compounds due to the self-interaction error12.

In this work, using the SCAN functional, we developed an approach that modifies the MP Pourbaix diagram construction to predict the aqueous stability of solids. The SCAN functional with Hubbard U corrections is used to improve performance in calculated formation energy for transition-metal oxides (TMOs). When compared to the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram, SCAN-computed Pourbaix diagrams systematically improve the accuracy of aqueous stability predictions, and therefore enable an avenue to more reliably screen materials by this figure of merit in high-throughput computations.

Results

Formation enthalpy of oxides

Though Zhang et al.12 investigated the formation enthalpy of 196 binary compounds using the SCAN functional, only 46 compounds are oxides, and most importantly, some oxides of technologically relevance (e.g., IrO2 and RuO2, both are popular oxygen evolution reaction (OER) catalysts) are not included in their benchmarking. In this work, we benchmark against a more comprehensive dataset of 114 binary oxides to demonstrate the performance of the SCAN functional in formation enthalpy calculations, which are particularly important in considerations of aqueous stability. However, the SCAN functional still performs poorly in calculated formation enthalpies for 3d TMOs (MAE = 0.205 eV/atom) due to self-interaction errors12,13. Using the MP methods, outlined in refs. 8,14, we developed a set of Hubbard U corrections to aid the SCAN functional to accurately calculate formation enthalpies for TMOs (TM = V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo) (Supplementary Table 1). These TMOs for Hubbard U corrections were selected by following the MP convention and TMOs studied in this work refer to these seven classes of TM oxides specifically8,14. We note that anion corrections from the standard suite of MP corrections8 are omitted in our approach because the SCAN functional has a very small error in the calculated O2 binding energy (5.27 eV vs. experimental 5.12–5.23 eV15,16). All PBE functional data used in this paper were retrieved from the MP5,17,18.

Figure 1 presents calculated formation enthalpies (ΔHcalc) of 114 binary oxides using the PBE(+U), SCAN, and SCAN(+U) functionals. The MAE of ΔHcalc for PBE(+U), SCAN, and SCAN(+U) are 0.182, 0.094, and 0.072 eV/atom, respectively. The inset figure shows ΔHcalc of TMOs using PBE+U, SCAN, and SCAN+U functionals. The non-U-corrected SCAN functional yields an MAE of 0.156 eV/atom in ΔHcalc and larger than 0.084 eV/atom of PBE+U. Whereas, SCAN+U significantly reduces the MAE of ΔHcalc from 0.156 to 0.025 eV/atom and is also smaller than PBE+U. In addition, SCAN+U using the U fitted to binary TMOs performs well on ternary systems, achieving an MAE of 0.053 eV/atom on a benchmark of 47 ternary TMOs (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Validation

We first benchmark our method by validating the calculated Pourbaix diagram of three examples of Ti, Ta, and Se with respect to their experimental Pourbaix diagram. Since the construction of Pourbaix diagrams depends on the species included, we here use consistent species for direct comparison between experiment and computation. The primary difference between computed and experimental Pourbaix diagrams is that the chemical potentials of solids in the computed Pourbaix diagram are calculated using the SCAN(+U) functional instead of experimental data. For theoretical Pourbaix diagrams, we use experimental thermodynamic data of aqueous ions according to the integration scheme of Persson et al.2. To further validate the accuracy of our method in aqueous stability predictions, we also generate a SCAN calculated Pourbaix diagram by computing and including all materials in the given composition space from the MP (termed “complete Pourbaix diagram”) to compare with the MP PBE results. This complete Pourbaix diagram serves as a valuable tool to predict the stability of a material with untabulated thermodynamic data. The experimental chemical potentials of solids and aqueous ions are from refs. 19,20,21.

Figure 2a shows the calculated Pourbaix diagram for Ti using the SCAN functional. Compared to the experimental diagram (Fig. 2b), the solid and aqueous stability regions are extraordinarily well-represented. The Ti Pourbaix diagram presented in the literature2,22 is generally constructed without TiH2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, where an excellent agreement between our calculated and experimental results is achieved as well. The inclusion of TiH2 will considerably reduce the stability region of Ti2+ in the conventional Ti Pourbaix diagram (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 2c), Ti2O7 becomes the stable phase instead of the TiO\({}_{2}^{2+}\) in extremely oxidative environments (E > 2.0 V), which is consistent with experiment23,24. In the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 2d), the predicted stability region of Ti2+ is much larger than that in the experimental diagram and TiO2 dissolves to TiO\({}_{2}^{2+}\) instead of being oxidized to Ti2O7 at high potentials (E > 2.0 V) in acid.

a–d Ti, e–h Ta, and i–l Se. SCAN and EXP. are Pourbaix diagrams generated with energies of the same species calculated using the SCAN functional and from experimental thermodynamic tables, respectively. SCAN (All) and MP PBE are the SCAN and PBE calculated Pourbaix diagrams by including all materials in the given composition space from the Materials Project, respectively. The PBE data were retrieved from the Materials Project14,17,18. Regions with solid are shaded in lake blue. The water stability window is shown in red dashed line.

Figure 2e shows the calculated Ta Pourbaix diagram using the SCAN functional, which is consistent with the experimental results in Fig. 2f. Tantalum pentoxide, Ta2O5, is barely reactive in aqueous solution and often serves as a catalyst or catalyst stabilizer for oxygen evolution in both acid and base because of its high aqueous stability25,26. We note that when adding the aqueous ion TaO\({}_{2}^{2+}\) in the Pourbaix diagram generation procedure (Supplementary Fig. 4), Ta2O5 dissolves to TaO\({}_{2}^{2+}\) in acid, contradicting experimental observations25,26. This is because Ta2O5 is corroded in concentrated hydrofluoric or alkaline media27. Some care has to be taken when screening aqueous stable materials for electrocatalysis, where dilute concentrations are commonly used in experiment. In the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 2g), high-valence tantalum oxides (e.g., Ta2O7) and tantalum hydrides (e.g., TaH2) are predicted to be stable under highly oxidative and reductive environments, respectively. Similar results are also observed in the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 2h).

In the above two examples, we have verified that our method makes predictions which have similar high qualitative accuracy as MP PBE2,5. Next, we present an example where our results are significantly different from MP PBE. Figure 2i shows the calculated selenium Pourbaix diagram using the SCAN functional, which closely reflects the experimental diagram, shown in Fig. 2j. The complete Pourbaix diagram using the SCAN functional is also the same as the experimental diagram (Fig. 2k). There is only one solid region (Se metal) in the SCAN calculated and experiment diagrams. In the MP PBE scheme, selenium oxides (SeO2, Se2O5, SeO3, SeO4) are overstabilized in acid and appear prominently in the Pourbaix diagram, shown in Fig. 2l. This overstabilization results from the MP anion correction scheme, which overcorrects the calculated formation enthalpies of selenium oxides. For example, the MP anion correction shifts the PBE calculated formation enthalpy of SeO2 from −2.111 to −3.515 eV/fu (ΔH\({}_{\exp }\) = −2.334 eV/fu).

3d metal (Mn/Fe/Co/Ni) Pourbaix diagram

By applying U corrections on top of O2 correction8,14, the MP PBE scheme provided the state-of-the-art computational 3d metals (M = Mn/Fe/Co/Ni) Pourbaix diagrams (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the scheme resulted in qualitative and quantitative inaccuracies when predicting the aqueous stability for metal (oxy)hydroxides and hydrides. This is because the affine corrections of the MP scheme may over- or undercorrect certain classes of materials or reference hydrogen chemical potentials in order to fix systematic errors in oxides. SCAN’s accuracy in predicting the underlying thermochemistry makes affine corrections largely unnecessary, meaning that more accurate Pourbaix diagrams can likely be constructed using the simpler methodology herein going forward.

a–d Mn, e–h Fe, i–l Co, and m–p Ni. SCAN and EXP. are the Pourbaix diagrams generated with energies of the same species calculated using the SCAN functional and from experimental thermodynamic tables, respectively. SCAN (All) and MP PBE are the SCAN and PBE calculated Pourbaix diagrams by including all materials in the given composition space from the Materials Project, respectively. The PBE data were retrieved from the Materials Project14,17,18. Regions with solid are shaded in lake blue. The water stability window is shown in red dashed line.

Figure 3 presents the calculated and experimental 3d metal (M = Mn/Fe/Co/Ni) Pourbaix diagrams. In general, the predicted solid and aqueous ion regions in the SCAN calculated diagrams are consistent with the experimental results. A notable difference is that the relative regions of stable species in the SCAN calculated diagrams are slightly different from those in experimental diagrams. This difference can be attributed to the uncertainties of the SCAN+U functional in calculating redox reactions energies of M2+ → M3+ → M4+. Overall, the calculated Pourbaix diagrams using the SCAN+U functional show better agreement with the experimental diagrams than MP PBE results (Fig. 3). A detailed discussion of each 3d metal Pourbaix diagram is presented.

Mn

In Fig. 3a, the stability region of Mn(OH)2 is slightly broader than that in the experimental diagram (Fig. 3b), resulting in the absence of Mn(OH)+. In the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3c), MnOOH appears in the stability regions of Mn2O3 and MnO2, which is in line with the experimental observations28 that MnOOH is synthesized at low temperature (<70 °C) around pH = 11 and transforms to Mn2O3 and MnO2 at high temperature.

Fe

In Fig. 3e, the solid and aqueous ions regions are well predicted by our method, compared to the experimental diagram, shown in Fig. 3f. In the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3g), FeOOH shows up in the Fe2O3 stability region. In experiment, FeOOH is found at low temperature and transforms to Fe2O3 after thermal treatment29,30. Moreover, high-valence iron oxides (FeO3, Fe4O13) and iron hydrides are found to be stable under extremely oxidative and reductive environments, respectively.

Co

In Fig. 3i, the stability regions of solids and aqueous ions are in good agreement with the experimental diagram (Fig. 3j). Similar to iron results, in the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3k), high-valence cobalt oxides and cobalt hydrides are found to be stable under extremely oxidative and reductive environments, respectively. The MP PBE results (Fig. 3l) shows large deviations from the experimental diagram, which is likely because of the inaccurate chemical potential of HCoO\({}_{2}^{-}\) used (See Supplementary Table 2).

Ni

Compared to the experimental Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3m), the relatively large stability region of Ni(OH)2 results in the absence of Ni3O4 in the calculated Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3n). In the complete Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 3o), NiOOH appears in the regions of Ni2O3 and Ni3O4, which is in line with the experimental observations that nickel oxyhydroxides often form instead of nickel oxides in solution31,32. The stability regions of solids and aqueous ions predicted by the MP PBE are in excellent agreement with the experiment diagram, except for the absence of nickel (oxy)hydroxides (Fig. 3p).

Applications

In this section, we showcase applications of our method in accurately predicting the aqueous stability of catalysts for electrocatalysis. IrO2 and RuO2 are the state-of-the-art electrocatalysts for OER in acidic media. The typical OER working conditions in acid are pH = 0 or 1 and potentials of 1.23–2.0 V. Singh et al.33 proposed that the aqueous stability can be quantitatively evaluated by computing the material’s Gibbs free energy difference (ΔGpbx) with respect to the stable domains in the Pourbaix diagram as a function of pH and potential. We will use this concept to evaluate the aqueous stability of IrO2 and RuO2 at OER working conditions.

Figure 4a, b shows the calculated Ir Pourbaix diagram and the Pourbaix decomposition free energy of IrO2 from the potential 0 to 2.0 V at pH = 0, respectively. We find that at pH = 0, IrO2 transforms to IrO3 at the potential of 1.55 V and IrO3 dissolves to IrO\({}_{4}^{-}\) at the potential of 1.60 V, which is consistent with the experimental observations that IrO2 dissolves at potentials of 1.50– 1.60 V in OER34,35,36. In experiment, the formation of high-valence iridium oxides, e.g., IrO3 is commonly regarded as the origin of instability of IrO2 during OER35,37. Based on the density functional theory (DFT) calculated phase diagram (Supplementary Fig. 5), IrO3 is predicted to be highly unstable in the SCAN functional with a decomposition energy of 159 meV/atom, whereas it is predicted be stable in the PBE functional. Considering that IrO3 is only detected as an intermediate species during OER in experiment35,37, we argue that the SCAN functional may give a reasonable phase stability for IrO3. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, the experimental Pourbaix diagram from Pourbaix’s atlas19 severely overestimates the OER stability region of IrO2 (1.23–1.87 V), while the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram seriously underestimates the stability region of IrO2 (1.23–1.24 V).

a, c Ir and Ru Pourbaix diagram generated with aqueous ion concentrations 10−6 M at 25 °C, respectively. b, d Pourbaix decomposition free energy ΔGpbx of IrO2 and RuO2 from the potential 0–2.0 V, respectively. The projection of ΔGpbx onto the potential axis highlights the stable species at the corresponding regions.

Figure 4a shows the calculated Ru Pourbaix diagram. There are only two solid regions, Ru and RuO2. In acid, the ruthenium metal is severely corroded, forming Ru3+, and RuO2 has also a narrow stable region. In experiment, it is generally believed that RuO2 exists in the form of hydrated oxide, RuO2⋅mH2O (1 ≤ m ≤ 2) and could be oxidized or reduced into amorphous Ru2O5 and Ru(OH)3⋅H2O, respectively21. Figure 4b shows the calculated Pourbaix decomposition free energy of RuO2 as a function of potentials at pH = 1. We observe that RuO2 dissolves to H2RuO5 at 1.34 V, which is in line with the experimental results that RuO2 has a dissolution onset potential of 1.37 V in 0.1 M H2SO434. In the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram (Supplementary Fig. 7), RuO4 is predicted to be stable from 0.92 to 2.0 V. Experiments indicate that RuO4 is unstable and readily dissolves in aqueous solution by forming H2RuO521.

Discussion

Distinct from the MP method2, the chemical potential of liquid water in this work is evaluated by using the gas-phase H2O at 0.035 bar, since at this pressure the gas-phase H2O is in equilibrium with liquid water at 298.15 K38. Using SCAN, this results in a very accurate ΔGf = −2.461 eV/fu without any affine corrections. In the MP framework of Pourbaix diagram construction, the chemical potential of hydrogen is corrected such that experimental Gibbs free formation energy of water is exactly replicated by construction. We use a chemical potential of −3.66 eV/atom for hydrogen, equal to half of the Gibbs free energy of hydrogen gas computed using the SCAN functional. We therefore regard the errors in the Gibbs free energy of formation for (oxy)hydroxides and hydrides as those of the SCAN functional itself, instead of from applied hydride corrections (e.g., 0.7–0.8 eV/H2) in the standard PBE functional2,39.

In the reaction energy calculation, we neglect the zero-point energy (EZPE) and the integrated heat capacity from 0 to 298.15 K (δH) for both solids and gases by assuming that the differences in these quantities between reactants and products are negligible at room temperature. Previous studies in the literature show that EZPE and δH of solids and gases are comparable39,40,41, but we note that estimation of EZPE and δH is possible, albeit expensive, with phonon or molecular dynamics calculations, and a systematic approach towards these that can further improve our approach merits a study in its own right.

In conclusion, by building on the MP Pourbaix diagram framework, we have developed a simple method to accurately predict the aqueous stability of solids. Benchmark results show that the calculated Pourbaix diagram using the SCAN functional improves the accuracy of predicted aqueous stability in a large number of cases of interest compared to the MP PBE results. We have also demonstrated the applications of this method in quantitatively predicting the dissolution potential of the state-of-the-art OER catalysts in acid, for which both the experimental and/or the MP PBE predictions show large deviations. Our approach enables reliably searching materials in terms of their aqueous stability for electrochemical applications.

Methods

Density functional theory

The spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) within the projector-augmented wave method42,43. The SCAN functional9 was used for all structural relaxations and energy calculations. A plane wave energy cutoff of 520 eV was used, and the electronic energy and atomic forces were converged to within 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively. The Brillouin zone was integrated with a k-point density of at least 1000 per reciprocal atom5. We followed the MP selection of TMOs (M = V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Mo) for Hubbard U corrections8,14,44. Note that the U correction for tungsten (W) oxides was not considered in this work due to the poor convergence of SCAN calculations. Different magnetic configurations were only considered for Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni TMOs in the Pourbaix diagram construction. All crystal structure manipulations and data analysis were carried out using the Pymatgen software package17.

Pourbaix diagram

All the Pourbaix diagrams were constructed using the MP method developed by Persson2 as implemented in Pymatgen17. In the MP method, the stable domains on the Pourbaix diagram are determined based on the knowledge of all possible equilibrium redox reactions in the chemical composition of interest. In an aqueous medium under a given pH (−log[H+]) and potential (E), the following redox reaction occurs:

At equilibrium, the Gibbs free energy change (ΔGrxn) of this reaction can be related to E using the Nernst equation

where \(\Delta {G}_{{\rm{rxn}}}^{{\rm{o}}}\) is the Gibbs free energy change of the reaction at standard conditions, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature. a is the activity coefficient. The most stable species in aqueous solutions can be therefore determined by minimizing (ΔGrxn + nFE) across all possible reactions under certain pH and applied potential.

The chemical potential of a material under standard conditions can be expressed as

where EDFT is the DFT calculated total energy, EZPE is the zero-point energy, δH is the integrated heat capacity from 0 to 298.15 K, and TS0 is the entropy contribution at the standard conditions. For gas-phase species, the DFT total energy was evaluated by a molecule in a 15 × 15 × 15 Å box; S0 data were collected from the experimental thermodynamic database45. For solid phase species, the entropy contribution was neglected since it was very small compared to the gas species. The EZPE and δH for both solid and gas species were neglected by assuming that these energies have similar contributions between species and therefore cancel out in reaction energies.

The chemical potentials of aqueous ionic species were obtained from experimental data with a correction of the referenced solid phase energy difference between DFT calculations and experiments (μsolid–solid)

The experimental formation Gibbs free energy of referenced solid and aqueous ions was collected from refs. 19,20,21.

Energy correction

In the MP PBE Pourbaix diagram construction, there are four primary corrections (anion correction, U correction for TMOs, hydroxide/peroxide correction, and water correction) applied to calibrate the calculated chemical potential of solids. Specifically, an energy correction of 1.40 eV/O2 was used for oxide compounds (See Supplementary Fig. 1). The Hubbard U correction was adopted for selected TMOs5,8. The hydroxides correction was used to calibrate the errors in calculated formation energy of hydroxides. The water correction was to adjust the total energy of water in order to reproduce the chemical potential of water2. In the SCAN Pourbaix diagram construction, only the Hubbard U correction was used for selected TMOs.

Data availability

All data necessary to support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information. Further data and codes can be made available from Z.W.

References

Hansen, H. A., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. Surface Pourbaix diagrams and oxygen reduction activity of Pt, Ag and Ni(111) surfaces studied by DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 3722–3730 (2008).

Persson, K. A., Waldwick, B., Lazic, P. & Ceder, G. Prediction of solid-aqueous equilibria: scheme to combine first-principles calculations of solids with experimental aqueous states. Phys. Rev. B 85, 1–12 (2012).

Montoya, J. H., Garcia-Mota, M., Nørskov, J. K. & Vojvodic, A. Theoretical evaluation of the surface electrochemistry of perovskites with promising photon absorption properties for solar water splitting. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 2634–2640 (2015).

Singh, A. K., Montoya, J. H., Gregoire, J. M. & Persson, K. A. Robust and synthesizable photocatalysts for CO2 reduction: a data-driven materials discovery. Nat. Commun. 10, 443 (2019).

Jain, A. et al. Formation enthalpies by mixing GGA and GGA+U calculations. Phys. Rev. B 84, 45115 (2011).

Guo, X. et al. Design principles for aqueous Na-ion battery cathodes. Chem. Mater. 32, 6875–6885 (2020).

National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 24007, Selenium dioxide, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Selenium-dioxide (2020).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B 73, 195107 (2006).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Sun, J. et al. Accurate first-principles structures and energies of diversely bonded systems from an efficient density functional. Nat. Chem. 8, 831–836 (2016).

Kitchaev, D. A. et al. Energetics of MnO2 polymorphs in density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 93, 045132 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Efficient first-principles prediction of solid stability: towards chemical accuracy. npj Comput. Mater. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-018-0065-z (2018).

Perdew, J. P. & Zunger, A. Self-interaction correction to density-functional approximations for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5048–5079 (1981).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the Materials Project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Pople, J. A., Head-Gordon, M., Fox, D. J., Raghavachari, K. & Curtiss, L. A. Gaussian-1 theory: a general procedure for prediction of molecular energies. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 5622–5629 (1989).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, W. Comment on-generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 890 (1998).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Ong, S. P. et al. The Materials Application Programming Interface (API): a simple, flexible and efficient API for materials data based on REpresentational State Transfer (REST) principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 97, 209–215 (2015).

Pourbaix, M. Atlas of electrochemical equilibria in aqueous solutions 2nd edn (National Association of Corrosion Engineers, 1998).

Wagman, D. D. et al. Selected values of chemical thermodynamic properties (United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, 1966). NBS technical note.

Rard, J. A. Chemistry and thermodynamics of ruthenium and some of its inorganic compounds and aqueous species. Chem. Rev. 85, 1–39 (1985).

Pley, M. & Wickleder, M. S. Two crystalline modifications of RuO4. J. Solid State Chem. 178, 3206–3209 (2005).

Kong, D.-S. & Wu, J.-X. An electrochemical study on the anodic oxygen evolution on oxide film covered titanium. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, C32 (2008).

Shi, X. et al. Understanding activity trends in electrochemical water oxidation to form hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–12 (2017).

Hwang, H. et al. Electro-catalytic activity of RuO2-IrO2-Ta2O5 mixed metal oxide prepared by spray thermal decomposition for alkaline water electrolysis. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 16, 4405–4410 (2016).

Xiao, W. et al. High catalytic activity of oxygen-induced (200) surface of Ta2O5 nanolayer towards durable oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Energy 25, 60–67 (2016).

Deblonde, G. J., Chagnes, A., Bélair, S. & Cote, G. Solubility of niobium(V) and tantalum(V) under mild alkaline conditions. Hydrometallurgy 156, 99–106 (2015).

Sharma, P. K. & Whittingham, M. S. The role of tetraethyl ammonium hydroxide on the phase determination and electrical properties of γ-MnOOH synthesized by hydrothermal. Mater. Lett. 48, 319–323 (2001).

Musić, S., Krehula, S. & Popović, S. Thermal decomposition of β-FeOOH. Mater. Lett. 58, 444–448 (2004).

Ristić, M., Musić, S. & Godec, M. Properties of γ-FeOOH, α-FeOOH and α-Fe2O3 particles precipitated by hydrolysis of Fe3+ ions in perchlorate containing aqueous solutions. J. Alloys Compd. 417, 292–299 (2006).

Hoppe, H.-W. & Strehblow, H.-H. XPS and UPS examinations of passive layers on Ni and FE53Ni alloys. Corros. Sci. 31, 167–177 (1990).

Beverskog, B. & Puigdomenech, I. Revised Pourbaix diagrams for nickel at 25-300 ∘C. Corros. Sci. 39, 969–980 (1997).

Singh, A. K. et al. Electrochemical stability of metastable materials. Chem. Mater. 29, 10159–10167 (2017).

Cherevko, S. et al. Oxygen and hydrogen evolution reactions on Ru, RuO2, Ir, and IrO2 thin film electrodes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes: a comparative study on activity and stability. Catal. Today 262, 170–180 (2016).

Kasian, O., Grote, J.-P., Geiger, S., Cherevko, S. & Mayrhofer, K. J. J. The common intermediates of oxygen evolution and dissolution reactions during water electrolysis on iridium. Angew. Chemie Int. Edition 57, 2488–2491 (2018).

Geiger, S. et al. The stability number as a metric for electrocatalyst stability benchmarking. Nat. Catal. 1, 508–515 (2018).

Pearce, P. E. et al. Revealing the reactivity of the iridium trioxide intermediate for the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Chem. Mater. 31, 5845–5855 (2019).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Zeng, Z. et al. Towards first principles-based prediction of highly accurate electrochemical Pourbaix diagrams. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 18177–18187 (2015).

Lany, S. Semiconductor thermochemistry in density functional calculations. Phys. Rev. B 78, 1–8 (2008).

Huang, L.-F. & Rondinelli, J. M. Reliable electrochemical phase diagrams of magnetic transition metals and related compounds from high-throughput ab initio calculations. npj Mater. Degrad. 3, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-019-0088-z (2019).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Linstrom, P. J. & Mallard W. G. NIST chemistry WebBook (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 2020). https://doi.org/10.18434/T4D303. NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69.

Kubaschewski O., Alcock C. B. & Spencer P. J. Materials thermochemistry 6th edn (Pergamon Press, 1993).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Toyota Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and J.K.N. designed the study. Z.W. performed the calculations, developed the code, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. X.G. contributed to the code development and data analysis. J.M. contributed to data analysis. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Guo, X., Montoya, J. et al. Predicting aqueous stability of solid with computed Pourbaix diagram using SCAN functional. npj Comput Mater 6, 160 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00430-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00430-3

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling the role of Fe and Ni in oxygen evolution reaction on pentlandite using three generations of computational surface models

npj Computational Materials (2026)

-

Synthesis of liquid nitrogenous fertilizer via a nitrogen conversion balance

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

Boosting the durability of RuO2 via confinement effect for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Effect of ionic-bonding d0 cations on structural durability in barium iridates for oxygen evolution electrocatalysis

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Nonprecious and long-term stable MOF@POM superstructure-derived electrocatalyst for water oxidation reaction

Science China Chemistry (2025)