Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) multiferroics have attracted increasing interests in basic science and technological fields in recent years. However, most reported 2D magnetic ferroelectrics are based on the d-electron magnetism, which makes them rather rare due to the empirical d0 rule and limits their applications for low magnetic phase transition temperature. In this work, we demonstrate that the ferroelectricity can coexist with the p-electron-induced ferromagnetism without the limitation of d0 rule and metallicity in a family of stable 2D MXene-analogous oxynitrides, X2NO2 (X = In, Tl). Remarkably, the itinerant character of p electrons can lead to the strong ferromagnetic metallic states. Furthermore, a possible magnetoelectric effect is manifested in a Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure through the interface engineering. Our findings provide an alternative possible route toward 2D multiferroics and enrich the concept of ferroelectric metals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiferroic materials integrating spontaneous ferroelectric and magnetic long-range orders1,2,3,4 have aroused great interests in recent decades as they not only offer a vigorous platform for discovering emergent phenomena in condensed-matter physics2,5, such as skyrmions6 and electromagnons7, but also have transformative technological potential8 in the high-density non-volatile memory devices, owing to multiple logic states9 and magnetoelectric effects4,8,10. Although electronic polarization and magnetization can be tightly coupled together within macroscopic electrodynamics, in a sense, they are typically incompatible in a single-phase material, which makes multiferroic materials highly scarce5,11. Commonly, the d orbitals occupied by the unpaired electrons, which give rise to magnetic moments, suppress the ferroelectric distortion12 that usually requires empty d orbitals (so-called d0 rule)8,11. To bypass this limitation, several mechanisms have been proposed in single-phase multiferroics8, including lone pair ferroelectricity (FE) + d-electron magnetism (e.g. BiFeO3)13, d0 FE + f-electron magnetism (e.g. strained EuTiO3)14, geometrically driven multiferroics (e.g. YMnO3)2, charge-ordering driven FE (e.g. Fe3O4)8, and spin-ordering driven FE (e.g. TbMnO3)15. However, the independent origins of FE and magnetism in type-I multiferroics within these strategies result in the extremely weak magnetoelectric effect3,5,11, while the FE order induced by magnetic spirals in type-II multiferroics is usually accompanied by small electric polarization (~10−2 μC(cm)−2) and low Curie temperature2,3,5,8, which severely hinder their practical applications. Hence, alternative mechanisms for the design of multiferroics that can work above room temperature and hold strong magnetoelectric coupling are urgently needed in fundamental physics and applications8.

Recently, two-dimensional (2D) multiferroics16,17,18,19,20 are the rising stars since the confirmation of 2D ferroelectrics (e.g. α-In2Se3)21 and magnetic van der Waals (vdW) materials (such as CrI3 and Fe3GeTe2 monolayer)22. Compared with conventional multiferroics, 2D counterparts with different properties, such as no surface dangling bonds23 and atomic thickness20, are promising for the miniaturization of devices and ultra-high-speed storage24. Actually, a number of 2D multiferroics have been reported theoretically or experimentally, including type-II multiferroics (Hf2VC2F2 MXene)19 and type-I multiferroics ((CrBr3)2Li monolayer20, CuCrP2S618, and VOX2 (X = Cl, Br, I)16,17). As expected, their magnetism originates from d electrons and the magnetic transition temperatures are usually low. As a matter of fact, p orbitals can also induce high-temperature ferromagnetism, namely d0 magnetism25, which has been verified in many systems such as nitrogen-doped graphene26 and carbon-doped ZnO27, but are rarely involved in 2D multiferroics within conventional mechanisms yet. Whether the intrinsic ferroelectricity can coexist and interact with the p-orbital ferromagnetism beyond the d0 rule or not in 2D crystal has still been under debate.

In this work, we report an alternative route for 2D multiferroics without the d0-rule requirement within a family of stable 2D MXene-analogous oxynitrides, X2NO2 (X = In, Tl). We show that these materials represent a class of p-orbital multiferroic metals, where the ferroelectricity and intrinsic ferromagnetism can stem from the same N ion. We demonstrate that the spin-polarized N-2px/2py electrons show an itinerant character, which can give rise to the metallicity and the strong ferromagnetism with a high Curie temperature. Interestingly, the intrinsic and strain-induced ferroelectricities driven by the offset displacement of N ion are predicted in Tl2NO2 and In2NO2 monolayers, respectively. Therefore, the X2NO2 monolayers may belong to the long-sought-after ‘ferroelectric metals’, which was proposed by Anderson et al. in 196528 and confirmed in the bulk LiOsO329 and bilayer WTe230 recently. Furthermore, a magnetoelectric effect is predicted in a Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure via the interface interaction.

Results and discussion

Atomic structures and stability

Recent observations of ferroelectricity in 2D In2Se321 as well as magnetic properties in N-doped In2O331 have raised the possibility of multiferroelectricity in two-dimensional oxynitrides, which motivated us to design a family of 2D oxynitrides X2NO2 (X = In, Tl). Firstly, to investigate the most stable atomic structures of the X2NO2 (X = In, Tl) monolayers, we considered 53 possible structural configurations (Supplementary Fig. 1, 2) reported by Ding et al.32, including fcc, FE-ZB′, and FE−WZ′ phases. The lattice parameters and formation energy of each structure are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–4. For the Tl2NO2 monolayer, the FE−WZ′ phase (Supplementary Tables 1, 2) with the symmetric stacking sequence of O–Tl–N–Tl–O is the most stable structure for its lowest formation energy (0.279 eV per atom), which is slightly lower than those of the FE–ZB′ (0.280 eV per atom) and fcc phases (0.295 eV per atom). Such value is much smaller than that of the successfully synthesized silicene (0.744 eV per atom)33, implying a good stability and possible fabrication of the Tl2NO2 monolayer. In contrast, the U24 phase with the asymmetric stacking sequence of N–In–O–In–O has the lowest formation energy (−0.499 eV per atom) for the In2NO2 monolayer (Supplementary Tables 3, 4), while its fcc phase has the lowest formation energy (−0.493 eV per atom) among structures with a symmetric stacking sequence of O–In–N–In–O. As the formation energies of U24 and fcc phases for the In2NO2 monolayer are negative and quite close to each other, both could be synthesized using the atomic layer-by-layer molecular-beam epitaxy deposition techniques, by which the sequences of atomic layers (N–In–O–In–O and O–In–N–In–O) may be precisely controlled34. In addition, the FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ In2NO2 monolayers show similar energy, slightly higher than that of the fcc phase. Similar results can be obtained by using the DFT-D3 method35, which accounts for the vdW interactions (Supplementary Table 5). It can be found that an attainable in-plane biaxial tensile strain larger than 2.6 % can trigger a phase transition from fcc to FE-ZB′ for In2NO2 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, c). Hence, applying biaxial tensile strain may be an effective method to stabilize the FE-ZB′ In2NO2 monolayer. However, for the Tl2NO2 monolayer, the FE−WZ′ phase is always more energetically stable than the fcc and FE−ZB′ phases under the attainable tensile strain (Supplementary Fig. 3b, d). Although the FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ phases are evidently quasi-degenerate in energy for the X2NO2 monolayers, they could be stabilized separately because of the sizable energy barriers between them36 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

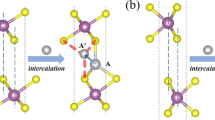

All the fcc, FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ phases consist of five triangular-lattice atomic layers with a vertical stacking in the sequence of O–X–N–X–O (Fig. 1a–c). The centrosymmetric fcc phase with a point group of D3d shares a similar structural characteristic with the synthesized oxygen-functionalized MXene37, in which each central nitrogen atom equivalently bonds with the surrounding 6 metal atoms. Interestingly, in both FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ phases, the off-center nitrogen atom coordinates tetrahedrally with four adjacent X atoms, forming three long X–N bonds and a short X–N bond oriented vertically (Supplementary Table 6). This results in a polar noncentrosymmetric structure with C3v symmetry, similar to the case of 2D ferroelectric In2Se321,32. Evidently, the inversion symmetry has been broken, and thus a vertical spontaneous polarization may be expected in these two phases.

The calculated phonon dispersions (Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 5) and the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD)38 simulations conducted for a 5 × 5 supercell (Supplementary Fig. 6) confirm that noncentrosymmetric FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ X2NO2, as well as centrosymmetric fcc In2NO2, possess not only good dynamical stability at 0 K, but also thermodynamical stability up to 300 K. However, the centrosymmetric fcc Tl2NO2 monolayer is not dynamically stable as there are two obvious imaginary optical phonon modes at Γ point, indicating spontaneous symmetry breaking in Tl2NO2 monolayer. We also explored the feasibility of the monolayer Al2NO2 and Ga2NO2 by the phonon dispersion spectra (Supplementary Fig. 5). We see that most of these structures (except fcc Al2NO2) are unlikely to be stable because of the obvious imaginary-frequency phonon modes. It is worth noting that the FE-ZB′ and FE−WZ′ phases for the X2NO2 (X = Al, Ga, In, and Tl) monolayers become more stable with the increase of the atomic number of X (Al → Tl). Furthermore, the mechanical stability of X2NO2 monolayer was also determined by calculating the elastic constants, \({C}_{11}={C}_{22}\), \({C}_{12}\), and \({C}_{66}=({C}_{11}-{C}_{12})/2\) within the standard Voigt notation after considering the symmetry of 2D hexagonal crystals (see details in Supplementary Note 1)39. We show that all thermodynamically stable monolayers meet the Born–Huang criteria39,40 for 2D hexagonal crystal system, i.e. \({C}_{11} \,>\, \left|{C}_{12}\right|\) and \({C}_{11} \,>\, 0\), indicating their mechanical stabilities (Supplementary Table 7). The calculated in-plane Young’s moduli of X2NO2 monolayers, which are comparable with 2D hexagonal Si41, as well as Poisson’s ratio and ideal tensile strength, manifest their superior mechanical properties (more details can be found in Supplementary Note 1). In summary, all these results indicate that the stable and metastable phases of X2NO2 (X = In, Tl) monolayers are experimentally feasible. As the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer is the most stable structure, we will focus on it in the following parts unless otherwise stated.

Magnetic and ferroelectric properties

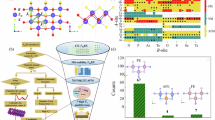

We proceed to focus on the magnetic and electronic properties of the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer. Although the d and f shells of the Tl ion are full, the electron spin polarization can be found in the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer with a total magnetic moment of about 1.06 μB per unit cell (Supplementary Table 1). Subsequently, the magnetic ground state was determined by estimating the energies of three possible magnetic configurations, including collinear ferromagnetic (FM), collinear stripe antiferromagnetic (sAFM), and the 120° noncollinear antiferromagnetic (yAFM) spin orders19 (Supplementary Fig. 9). The FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer is found to prefer a ferromagnetic ordering with a sizable exchange energy (defined as Eex = EsAFM − EFM, where EsAFM and EFM are the energies of sAFM and FM states, respectively) of 128.92 meV per N atom (Supplementary Table 8). The noncollinear yAFM state is unstable as it has the highest energy among these three magnetic configurations. We also find this FM ground state to be robust with the in-plane biaxial tensile strain even up to 6% (Supplementary Fig. 10). The local magnetic moment for N ion is about 0.6 μB. Interestingly, the O ion carries a local magnetic moment of 0.2 μB in the top surface layer, but nearly zero in the bottom surface layer (Supplementary Table 9), which shows an asymmetric spin density distribution. Unsurprisingly, there is no notable magnetic moment on the Tl ions, in accord with the full-filled d and f electrons. The spin-resolved band structure (Fig. 2a) and the projected density of states (PDOS) (Supplementary Fig. 11) at the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)42 level reveal that the N-2px/2py orbitals are significantly spin-polarized, which is consistent with the spin density distributions (Fig. 2b), where the majority of spin density is found on the N atoms and a very small amount of it is found on the O atoms in the top surface layer. Furthermore, the spin-down bands around the Fermi level are mainly contributed by the N-2p and O-2p orbitals and show a similar metallic feature with the ferromagnetic transition metals induced by the itinerant d electrons, which coincides with the non-integer value of the magnetic moment. Moreover, one can find this itinerant ferromagnetic character to be relatively robust against the spin orbital coupling (SOC) (Supplementary Fig. 12) and biaxial in-plane tensile strain even up to 6% from band structures using the PBE (Supplementary Fig. 13) and Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof hybrid (HSE06) functional43 (Supplementary Fig. 14).

a The spin-polarized band structure (left) and the element-resolved PDOS (right) at PBE level for FE−WZ′ X2NO2 monolayer near the Fermi level, which is set to zero. Γ (0, 0, 0), M (1/2, 0, 0), and K (1/3, 1/3, 0) are the highly symmetric points in reciprocal space. b Top and side views of the spin charge density for sAFM and FM FE−WZ′ X2NO2 monolayers. The isovalue is 0.1 electron per Å3. Spin-up and spin-down electrons are colored as cyan and orange, respectively. c Angle-dependent magnetic anisotropic energy with the magnetic moments lying on xy, xz, and yz planes. The energies for the case of the spin along the easy magnetization planes (xy/xz) are set to zero. The angles between the spin vector and the x, y, and z axes are shown in the inset. d The temperature dependence of the magnetic moment M (in red) and specific heat (in violet) of the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer.

To further understand the origin behind this strong ferromagnetism and metallicity, we plot the band structure and the density of states (DOS) without considering the spin polarization (Supplementary Fig. 15) and find a relatively flat band mainly contributed by the N-2p orbitals along the Γ-M line near the Fermi level and a sharp peak of DOS at the Fermi level. The DOS at the Fermi level D(EF) equals 5.03 states per eV per N atom and the Stoner parameter I is about 0.97 eV. Thus, they meet the Stoner criterion for a stable ferromagnetic state44, D(EF)I > 1, which coincides with the positive exchange energy. This suggests that the relatively localized N-2p electrons, serving as itinerant electrons, can give rise to strong ferromagnetism and metallic feature. A similar mechanism has been reported in the hole-injected ZnO44. Taken together, these results show that the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer is evidently a promising candidate for 2D ferromagnetic metal based on the d0 magnetism. As such p-orbital ferromagnetism in this stable single-phase material is intrinsic and undoped, it should be strong and experimentally feasible in contrast to the impurity-induced ones.

In practical applications, the high magnetic anisotropy is desirable for the high-density magnetic storage, as it can lift the Mermin–Wagner restriction45 in 2D systems and stabilize the long-range magnetic ordering against the thermal fluctuations. Therefore, the angle-dependent magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE) in the xz, yz, and xy planes were calculated by considering the SOC effect. One can see that the MAE of 2D FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 possess the uniaxial anisotropy, which is a common feature of the hexagonal structures46 (Fig. 2c). Specifically, the total energy varies significantly with the magnetization direction in the xz and yz planes, but is isotropic in the xy plane. Such strongly angle-dependent MAE along the z-direction has also been reported in other 2D magnetic materials, e.g. Fe3GeTe246. In contrast to Fe3GeTe2 and CrI3, which have been confirmed as Ising ferromagnets with the out-of-plane easy axis45,46,47, FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 exhibits an easy magnetic xy plane with a MAE up to about 166 μeV per N atom. Importantly, the MAE of FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 is much larger than those of some classical magnetic metals (in the order of μeV per atom)48 and comparable to those of CrGeTe3 monolayers (220 μeV per f.u.)49.

Another key parameter to characterize the robustness of the ferromagnetic ordering is the Curie temperature TC. Although numerous 2D magnetic materials have been unveiled recently, 2D ferromagnetic ordering with a TC above room temperature (~300 K) has been scarcely reported. For the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer, the considerable exchange energy may lead to a high TC. The Curie temperature is evaluated to be 332 K within the mean field approximation by using \({T}_{{\rm{C}}}=\frac{2\triangle E}{{3k}_{{\rm{B}}}}\), where \(\triangle E=\frac{{E}_{{\rm{ex}}}}{3}\) means the average exchange energy for each spin coupling interaction and \({k}_{{\rm{B}}}\) is Boltzmann’s constant50. As the total magnetic moment is very close to 1 μB, we also performed the Monte Carlo simulations based on the Heisenberg model to obtain a TC more precisely (more details can be found in Supplementary Note 2). From the temperature-dependent magnetic moment and specific heat (Fig. 2d), the estimated Curie temperature is 415 K. Therefore, the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer might be a potential ferromagnetic metal working above room temperature. Additionally, the strong ferromagnetism, as well as the robust metallic feature, can also be found in FE−ZB′ X2NO2 and FE−WZ′ In2NO2 monolayers (see more details in Supplementary Figs. 10–14, Supplementary Figs. 17–21, and Supplementary Table 9).

In addition to ferromagnetism, ferroelectricity can also be anticipated in the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer. Taking the fcc phase as a reference, the mirror symmetry with respect to the xy plane is evidently broken in the FE−WZ′ phase by the off-center displacement of the magnetic N atom. Such a structural distortion can be attributed to the imaginary optical phonon modes at Γ point of fcc phase (Fig. 1a), which commonly induces a symmetry-lowering phase transition according to the soft mode theory12. From the electrostatic potential along the z-direction (Fig. 3a), one can find a vacuum level difference (ΔΦ) of 0.75 eV (Table 1) between the top and bottom surfaces, which indicates the existence of the intrinsic out-of-plane dipole moment. The calculated out-of-plane electric dipole moment (pe) using the method suggested by Ding et al.32 is about 0.045 eÅ (Table 1), which corresponds to an out-of-plane spontaneous polarization of 6.6 pC m−1 in the 2D unit (P2D) or 1.3 μC(cm)−2 in the 3D unit (P3D) (if the thickness is taken to be 5.2 Å). This value has the same order of magnitude as that of α-In2Se332 and is larger than those of some 2D materials with out-of-plane FE, such as d1T MoS2 (0.18 μC(cm)−2)51 and 2D Hf2VC2F2 (0.27 μC(cm)−2)19. The electric polarization is also confirmed by the asymmetric spatial distribution of charge density difference between FE−WZ′ and fcc phases (Fig. 3b). Clearly, the dipoles lying in the xy plane shows a threefold rotational symmetry and thus the net in-plane electric polarization is zero, which is consistent with the nature of C3v symmetry.

a Electrostatic potential curve of the relaxed monolayers along the z-direction. The electrostatic potential difference (ΔΦ) is defined as the vacuum level difference between the top and bottom surfaces. b Top and side views of charge density differences between FE-WZ′ and fcc Tl2NO2 (left), and between FE-ZB′ and fcc In2NO2 (right). Green, yellow, and violet colors denote depleted charge, accumulated charge, and electric polarization, respectively. The isovalue is 1 electron per Å3. c The minimum energy pathway in the polarization reversal process for FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer. d Minimum energy pathway as a function of the in-plane biaxial tensile strain (from 0% to 5%) in the structural transition between two states with opposite electric polarization (P and −P) for the FE-ZB′ In2NO2 monolayer. The transformation proceeds through a centrosymmetric structure in which the polarization is zero.

Note that the position of the central N atom has two values, corresponding to two equivalent structures with the same energy but opposite electric polarizations pointing upward and downward. The minimum energy pathway connecting these two structures (Fig. 3c) shows that the polarization reversal process may go through a centrosymmetric paraelectric phase and the activation barrier (Ebarrier) is about 0.65 eV per unit cell, comparable to those of some recently reported 2D ferroelectrics52 and bulk Td-WTe2 (0.70 eV per f.u.)53. Such a barrier implies a high phase transition temperature. According to classical electromagnetic theory, the electrical field cannot switch the polarization in a polar metal because of the electron screening effects arising from the conduction electrons54. But the situation may be different for the metallic FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 monolayer, in which the out-of-plane motion of electrons is restricted, so that the out-of-plane ferroelectricity could be switched by an electric field54. In this sense, the FE−WZ′ Tl2NO2 may be considered as a ferroelectric metal.

Similarly, the out-of-plane polarization can also exist in the FE−ZB′ In2NO2 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 22) and is calculated to be 2.75 μC(cm)−2 (Table 1). But note that FE−ZB′ In2NO2 is not a ferroelectric material because the centrosymmetric fcc phase is more stable in energy and thus the double-well potential16 is lacking. However, we find a strain-induced ferroelectricity in the FE−ZB′ In2NO2. Figure 3d shows the activation barriers in the polarization switching processes under different in-plane biaxial tensile strain. Remarkably, the centrosymmetric structure in the center of the minimum energy pathway gradually becomes unstable in energy with increasing strain. Evidently, two ferroelectric ground states with opposite electric polarizations can be found at the minima of the potential energy well under the biaxial tensile strain not less than 1%. Additionally, the classical double-well potential can be found when the biaxial tensile strain is up to 5%. Furthermore, the activation barrier gets its maximum value of 0.14 eV under the biaxial strain of 4% and the corresponding electric polarization is about 2.79 μC(cm)−2 (Table 1). We also calculated the phonon spectra of the fcc and FE−ZB′ In2NO2 monolayers under the strain of 4%. One can find apparent imaginary optical frequency modes occurring in the fcc phase but not in FE−ZB′ phase (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating a strain-induced structural instability of the fcc phase. Such imaginary-frequency modes activate a symmetry-lowering phase transition from the fcc to FE−ZB′ phase, in which the off-center displacement of the magnetic N ion occurs. Therefore, the FE−ZB′ In2NO2 monolayer could be tuned to be a ferroelectric metal by strain engineering. The changes of the total magnetic moments along the minimum energy pathways are shown in Supplementary Fig. 23. We find that the magnetic moments of the centrosymmetric paraelectric phases are slightly smaller than those of the corresponding ferroelectric phases.

Magnetoelectric effect in Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure

The coupling between the magnetic order and ferroelectric order, namely, the magnetoelectric effect, provides a way for the electric-field control of spin states and the magnetic-field control of charge states. It seems that there is no SOC-induced magnetoelectric coupling in FE-WZ’ Tl2NO2 monolayer because the easy plane is independent of the direction of electric polarization (Fig. 2c). However, we notice that the spin density of oxygen ions can be transferred between the top surface layer and the bottom surface layer (Fig. 2b) when the polarization is switched back and forth, which may introduce a magnetoelectric coupling through the interface effect.

Here, we propose 2H-WTe2 to be an ideal substrate for FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2, as the 2H phase WTe2 monolayer has a small lattice mismatch (~1%) with the FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2. Six different stacking configurations (Supplementary Fig. 24) of the FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2/WTe2 vdW heterostructure were considered in our calculations. To simulate the epitaxial growth process of FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2 on WTe2, we fixed the lattice constant of FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2 to match WTe2 during the structural optimization. The AA1 pattern (Fig. 4a) with the polarization directions pointing upward is the most stable configuration as it has the lowest binding energy (Supplementary Fig. 25). Remarkably, when the polarization is switched from downward to upward, the magnetic moment of AA1 decreases from 0.95 μB to 0.9 μB, accompanied by the reduction of the interlayer distance and binding energy (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26), which suggests an enhanced interaction between two layers. To understand this result, the charge density differences in spin-up and spin-down channel were calculated (Fig. 4a, b), which can be defined as55 \(\rho ={\rho }_{{{\rm{tot}}}}-{\rho }_{{\rm{T}}{{\rm{l}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}-{\rho }_{{\rm{WT}}{{\rm{e}}}_{2}}\), where \({\rho }_{{{\rm{tot}}}}\), \({\rho }_{{\rm{T}}{{\rm{l}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\), and \({\rho }_{{\rm{WT}}{{\rm{e}}}_{2}}\) are the electron densities of the heterostructure, isolated FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2 and isolated WTe2, respectively. We can see that the electrons could transfer from 2H-WTe2 to FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2, regardless of the polarization (downward or upward). However, when the polarization is switched from pointing downward to pointing upward, the transfer of spin-down electrons is significantly increased (Fig. 4a, b), which may lead to the redistribution of electrons in spin-up and spin-down channels in FE-WZ’ Tl2NO2 and the reduction of the total magnetic moment.

a, b The charge density differences in spin-up and spin-down channels for Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure with polarization directions pointing (a) upward and (b) downward. Red, wathet, gray, orange, and green spheres denote O, N, Tl, Te, and W atoms, respectively. The green arrows denote the direction of polarizations. The interlayer distance is donated by d. (c, d) The spin-resolved band structure of the Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure with polarization directions pointing (c) upward and (d) downward. The orange and violet lines indicate the spin-up and spin-down bands contributed by Tl2NO2 monolayer, respectively. The sizes of the red and green dots represent the weights of spin-up and spin-down states contributed by the WTe2 monolayer, respectively.

This spin-down electron transfer is also confirmed in the band structures (Fig. 4c, d). Obviously, the spin-down states around K point from FE-WZ′ Tl2NO2 and 2H-WTe2 are hybridized near the Fermi level in the band structure of Tl2NO2/WTe2 with an ‘up’ polarization (Fig. 4c), in contrast to the situation with a ‘down’ polarization (Fig. 4d). This result implies a possible electric-field control of spin states in the Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructure via the interface effect.

In summary, an possible strategy to design two-dimensional multiferroics without the d0-rule requirements has been reported in a family of stable 2D MXene-analogous oxynitrides, X2NO2 (X = In, Tl). Distinct from all previous cases, the ferroelectricity and intrinsic p-orbital ferromagnetism can stem from the same ion, which naturally circumvents the incompatibility between ferroelectricity and magnetism usually seen in d-electron based multiferroics. The strong ferromagnetic metallic states might be maintained above room temperature owing to the relatively localized nature of the itinerant 2p states. Furthermore, the charge transfer between Tl2NO2 and WTe2 in their heterostructure can lead to an electric-field control of spin states. Our findings may pave an alternative way to the design of the 2D multiferroics and the discovery of ferroelectric metals.

Methods

Computational details

Our density functional theory calculations56 were carried out using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package code57. The electron-ion interaction was treated by the projector augmented wave method58. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof version of the generalized gradient approximation was used for the exchange-correlation functional42. The Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof hybrid functional (HSE06) was employed to obtain accurate electronic band structures43. To avoid the interaction between the periodic images, a vacuum region more than 15 Å along the z-direction was set. The plane-wave cutoff energies were set as 520 eV. Meanwhile, for the Brillouin zone sampling, a 16 × 16 × 1 and 10 × 10 × 1 Γ-centered Monkhorst–Pack k point mesh were used for the PBE and HSE06 calculations, respectively59. The convergence criterion for energy was set to 10−8 eV and ionic relaxation was carried out with a force tolerance of 0.001 eVÅ−1. The dipole correction60 was adopted for the calculation of the out-of-plane electric dipole moment32. The phonon spectra were calculated using a linear response approach61 with the PHONOPY code62. To investigate the thermodynamic stability of the monolayers, AIMD simulations were carried out using the canonical ensemble38 with a 5 × 5 × 1 supercell at 300 K with a time step of 1 fs. The climbing image nudged elastic band method63 was implemented to obtain the energy barriers in the structural transitions. The SOC effect was also considered in band structure calculations, which yields no significant effect. The formation energy of X2NO2 monolayers is described as \({E}_{{\rm{f}}}={(E}_{{{\rm{X}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}-2{\mu }_{{\rm{X}}}-{\mu }_{{\rm{N}}}-2{\mu }_{{\rm{O}}})/5\), where \({E}_{{{\rm{X}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\) is the total energy and \({\mu }_{{\rm{X}}}\), \({\mu }_{{\rm{N}}}\), and \({\mu }_{{\rm{O}}}\) are chemical potentials determined by the most stable X crystal, gas phase N2, and O2, respectively. The vdW interaction between Tl2NO2 and WTe2 monolayers was described by the DFT-D3 method35. The binding energies of the Tl2NO2/WTe2 heterostructures can be defined as55 \({E}_{{\rm{b}}}={E}_{{\rm{tot}}}-{E}_{{\rm{T}}{{\rm{l}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}-{E}_{{\rm{WT}}{{\rm{e}}}_{2}}\), where \({E}_{{\rm{tot}}}\), \({E}_{{\rm{T}}{{\rm{l}}}_{2}{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}}\), and \({E}_{{\rm{WT}}{{\rm{e}}}_{2}}\) are the energies of the heterostructure, Tl2NO2, and WTe2, respectively. To estimate the Curie temperature, the Monte Carlo simulations based on the Heisenberg model were performed using MCSOLVER64.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All non-commercial numerical codes to reproduce the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schmid, H. Multi-ferroic magnetoelectrics. Ferroelectrics 162, 317–338 (1994).

Wang, K. F., Liu, J. M. & Ren, Z. F. Multiferroicity: the coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 58, 321–448 (2009).

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Meier, D. & Trassin, M. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16046 (2016).

Vaz, C. A. F., Hoffman, J., Ahn, C. H. & Ramesh, R. Magnetoelectric coupling effects in multiferroic complex oxide composite structures. Adv. Mater. 22, 2900–2918 (2010).

Dong, S., Liu, J.-M., Cheong, S.-W. & Ren, Z. Multiferroic materials and magnetoelectric physics: symmetry, entanglement, excitation, and topology. Adv. Phys. 64, 519–626 (2015).

Seki, S., Yu, X. Z., Ishiwata, S. & Tokura, Y. Observation of skyrmions in a multiferroic material. Science 336, 198–201 (2012).

Takahashi, Y., Shimano, R., Kaneko, Y., Murakawa, H. & Tokura, Y. Magnetoelectric resonance with electromagnons in a perovskite helimagnet. Nat. Phys. 8, 121–125 (2012).

Spaldin, N. A. & Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 18, 203–212 (2019).

Gajek, M. et al. Tunnel junctions with multiferroic barriers. Nat. Mater. 6, 296–302 (2007).

Fiebig, M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 38, R123–R152 (2005).

Dong, S., Xiang, H. & Dagotto, E. Magnetoelectricity in multiferroics: a theoretical perspective. Natl Sci. Rev. 6, 629–641 (2019).

Hill, N. A. Why are there so few magnetic ferroelectrics? J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 6694–6709 (2000).

Wang, J. et al. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science 299, 1719–1722 (2003).

Lee, J. H. et al. A strong ferroelectric ferromagnet created by means of spin–lattice coupling. Nature 466, 954–958 (2010).

Kenzelmann, M. et al. Magnetic Inversion Symmetry Breaking and Ferroelectricity in TbMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 087206 (2005).

Ai, H., Song, X., Qi, S., Li, W. & Zhao, M. Intrinsic multiferroicity in two-dimensional VOCl2 monolayers. Nanoscale 11, 1103–1110 (2019).

Xu, C. et al. Electric-field switching of magnetic topological charge in type-i multiferroics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 037203 (2020).

Lai, Y. et al. Two-dimensional ferromagnetism and driven ferroelectricity in van der Waals CuCrP2S6. Nanoscale 11, 5163–5170 (2019).

Zhang, J.-J. et al. Type-II multiferroic Hf2VC2F2 mxene monolayer with high transition temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9768–9773 (2018).

Huang, C. et al. Prediction of intrinsic ferromagnetic ferroelectricity in a transition-metal halide monolayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 147601 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Out-of-plane piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity in layered α-In2Se3 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 17, 5508–5513 (2017).

Li, H., Ruan, S. & Zeng, Y.-J. Intrinsic Van Der Waals magnetic materials from bulk to the 2D limit: new frontiers of spintronics. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900065 (2019).

Feng, X., Ma, X., Sun, L., Liu, J. & Zhao, M. Tunable ferroelectricity and antiferromagnetism via ferroelastic switching in an FeOOH monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 13982–13989 (2020).

Chu, J. et al. 2D polarized materials: ferromagnetic, ferrovalley, ferroelectric materials, and related heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004469 (2021).

Coey, J. M. D. d0 ferromagnetism. Solid State Sci. 7, 660–667 (2005).

Fu, L. et al. Graphitic-nitrogen-enhanced ferromagnetic couplings in nitrogen-doped graphene. Phys. Rev. B 102, 094406 (2020).

Pan, H. et al. Room-temperature ferromagnetism in carbon-doped ZnO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 127201 (2007).

Anderson, P. W. & Blount, E. I. Symmetry considerations on martensitic transformations: “ferroelectric” metals? Phys. Rev. Lett. 14, 217–219 (1965).

Shi, Y. et al. A ferroelectric-like structural transition in a metal. Nat. Mater. 12, 1024–1027 (2013).

Fei, Z. et al. Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336–339 (2018).

Shen, L., An, Y., Cao, D., Wu, Z. & Liu, J. Room-temperature ferromagnetic enhancement and crossover of negative to positive magnetoresistance in N-doped In2O3 films. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 26499–26506 (2017).

Ding, W. et al. Prediction of intrinsic two-dimensional ferroelectrics in In2Se3 and other III2-VI3 van der Waals materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 14956 (2017).

Shao, X. et al. Electronic properties of a pi-conjugated Cairo pentagonal lattice: Direct band gap, ultrahigh carrier mobility, and slanted Dirac cones. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085437 (2018).

Putzky, D. et al. Strain-induced structural transition in DyBa2Cu3O7−x films grown by atomic layer-by-layer molecular beam epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 072601 (2020).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Ai, H., Ma, X., Shao, X., Li, W. & Zhao, M. Reversible out-of-plane spin texture in a two-dimensional ferroelectric material for persistent spin helix. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 054407 (2019).

Anasori, B., Lukatskaya, M. R. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Maździarz, M. Comment on ‘The Computational 2D Materials Database: high-throughput modeling and discovery of atomically thin crystals’. 2D Mater. 6, 048001 (2019).

Mouhat, F. & Coudert, F.-X. Necessary and sufficient elastic stability conditions in various crystal systems. Phys. Rev. B 90, 224104 (2014).

Andrew, R. C., Mapasha, R. E., Ukpong, A. M. & Chetty, N. Mechanical properties of graphene and boronitrene. Phys. Rev. B 85, 125428 (2012).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Peng, H. et al. Origin and enhancement of hole-induced ferromagnetism in first-row d0 semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017201 (2009).

Huang, B. et al. Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit. Nature 546, 270–273 (2017).

Zhuang, H. L., Kent, P. R. C. & Hennig, R. G. Strong anisotropy and magnetostriction in the two-dimensional Stoner ferromagnet Fe3GeTe2. Phys. Rev. B 93, 134407 (2016).

Deng, Y. et al. Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional Fe3GeTe2. Nature 563, 94–99 (2018).

Halilov, S. V., Perlov, A. Y., Oppeneer, P. M., Yaresko, A. N. & Antonov, V. N. Magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy in cubic Fe, Co, and Ni: applicability of local-spin-density theory reexamined. Phys. Rev. B 57, 9557–9560 (1998).

Zhuang, H. L., Xie, Y., Kent, P. R. C. & Ganesh, P. Computational discovery of ferromagnetic semiconducting single-layer CrSnTe3. Phys. Rev. B 92, 035407 (2015).

Kan, M., Adhikari, S. & Sun, Q. Ferromagnetism in MnX2 (X = S, Se) monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 4990–4994 (2014).

Shirodkar, S. N. & Waghmare, U. V. Emergence of ferroelectricity at a metal-semiconductor transition in a 1T monolayer of MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 157601 (2014).

Gao, W. & Chelikowsky, J. R. Prediction of intrinsic ferroelectricity and large piezoelectricity in monolayer arsenic chalcogenides. Nano Lett. 20, 8346–8352 (2020).

Sharma, P. et al. A room-temperature ferroelectric semimetal. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax5080 (2019).

Luo, W., Xu, K. & Xiang, H. Two-dimensional hyperferroelectric metals: a different route to ferromagnetic-ferroelectric multiferroics. Phys. Rev. B 96, 235415 (2017).

Obeid, M. M., Bafekry, A., Ur Rehman, S. & Nguyen, C. V. A type-II GaSe/HfS2 van der Waals heterostructure as promising photocatalyst with high carrier mobility. Appl. Surf. Sci. 534, 147607 (2020).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Bengtsson, L. Dipole correction for surface supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. B 59, 12301–12304 (1999).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Liu, L., Chen, S., Lin, Z. & Zhang, X. A symmetry-breaking phase in two-dimensional FeTe2 with ferromagnetism above room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 7893–7900 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) from Macau SAR (0081/2019/AMJ, 0102/2019/A2, and 0154/2019/A3). The DFT calculations were performed at the High Performance Computing Cluster (HPCC) of the Information and Communication Technology Office (ICTO) at the University of Macau. The Monte Carlo simulations were carried out on TianHe-2 at LvLiang Cloud Computing Center of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.P. conceived the idea and supervised the project. H.A. carried out first-principles calculations and conducted Monte Carlo simulations. H.A., H.P., and K.H.L. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript together.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41524_2022_737_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Information for Ferroelectricity Coexisted with p-Orbital Ferromagnetism and Metallicity in Two-Dimensional Metal Oxynitrides

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ai, H., Li, F., Bai, H. et al. Ferroelectricity coexisted with p-orbital ferromagnetism and metallicity in two-dimensional metal oxynitrides. npj Comput Mater 8, 60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00737-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00737-3

This article is cited by

-

Stoner instability-mediated large magnetoelectric effects in 2D stacking electrides

npj Computational Materials (2024)