Abstract

We study a doped transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) monolayer in an optical microcavity. Using the microscopic theory, we simulate spectra of quasiparticles emerging due to the interaction of material excitations and a high-finesse optical mode, providing a comprehensive analysis of optical spectra as a function of Fermi energy and predicting several modes in the strong light-matter coupling regime. In addition to exciton-polaritons and trion-polaritons, we report polaritonic modes that become bright due to the interaction of excitons with free carriers. At large doping, we reveal strongly coupled modes corresponding to excited trions that hybridize with a cavity mode. We also demonstrate that the increase of carrier concentration can change the nature of the system’s ground state from the dark to the bright one. Our results offer a unified description of polaritonic modes in a wide range of free electron densities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDC) represent a class of two-dimensional (2D) materials with remarkable optical properties. They are direct bandgap semiconductors with hexagonal Brillouin zone, with two nonequivalent valleys at the K and K\({}^{\prime}\) points1,2,3. Due to large spin-orbit interaction, they experience spin-valley locking, which opens the way for spin and valleytronic applications4. Moreover, the direct bandgap type and relatively large effective masses of electrons and holes lead to the formation of robust bright excitons5. Due to large exciton binding energy, they dominate an optical response of TMDC materials even at room temperature6,7. Also, thanks to peculiar Coulomb interaction screening in 2D8,9,10 TMDC excitons have a non-Rydberg energy spectrum11. Combined with the remarkable compatibility of these materials with various semiconductor/dielectric platforms, this makes them promising candidates for the development of various nanophotonic components12, including logic circuits13,14, phototransistors15, and light sensors16 as well as light-producing and harvesting devices 17,18. Studies of defects in TMDC monolayers and increased confinement also led to efficient single-photon emitters19,20.

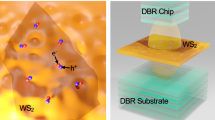

One of the perspective fields of the application of TMDC monolayers is polaritonics. Exciton-polaritons are hybrid light-matter quasiparticles formed due to the strong coupling (SC) between excitons and a tightly-confined optical mode (reviewed in21). Possible realizations include coupling to photonic crystal cavities, surface plasmons, nanoparticle resonances, open fiber cavities, and planar microcavities based on distributed Bragg reflectors (see the full polariton panorama in22. In this configuration, a plethora of quantum collective phenomena is observed at surprisingly high temperatures, which include polariton lasing23,24,25 and emergent polariton fluid behavior26, and nontrivial polariton lattice dynamics27,28,29,30,31. These phenomena pave the way for ultrafast polariton-based nonlinear optical integrated devices32,33,34,35,36.

The strong light-matter coupling regime is achieved when the exciton-photon coupling, characterized by the vacuum Rabi splitting Ω, overcomes losses, Ω > κ, γ21. The latter stem from the finite transmittance of the photonic cavity mirrors (κ) and a finite non-radiative lifetime of the excitons (γ). TMDC monolayers are very promising in this context. Indeed, as compared to conventional semiconductor materials, TMDC excitons have substantially higher binding energies. This makes the resulting TMDC polariton stable even at room temperatures and provides high optical oscillator strengths37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45.

The interaction of excitons with free electron gas, which can be present in a TMDC monolayer due to external doping, substantially modifies its optical response. The position of the excitonic line is shifted due to the effects of the bandgap renormalization46,47,48,49,50. In addition, complimentary screening and effects of Pauli blocking change the structure of excitons, making them less compact and reducing the corresponding oscillator strength and Rabi splitting51. Other absorption peaks appear due to the brightening of an intervalley exciton52. The interaction between excitons and an electron gas leads to the appearance of Fermi sea based quasiparticles being trions4,53,54,55,56,57 or exciton polarons58,59,60,61,62. The presence of such quasiparticles can qualitatively modify the light-matter coupling and completely reshape the polaritonic spectrum63,64. Moreover, various nonlinear effects62,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73 arise from the phase-space filling as well as exciton-exciton and exciton-electron scattering, which offer a route towards polariton condensation74 and the emergence of spontaneous coherence in monolayers strongly coupled to light75.

Here, we develop the quantitative microscopic theory for exciton-polariton states in TMDC monolayers with different doping levels. We consider a TMDC monolayer placed in an optical microcavity (Fig. 1). We solve the three-body problem by exact diagonalization of the Hamiltonian in a three-particle basis set52,76,77,78,79,80, where an eigenmode solution is available at small and high free electron concentrations. We observe that an additional dressed-exciton mode appears at small doping, apart from the dominant exciton and trion polariton contributions. Qualitatively, its formation can be explained as a result of the brightening of an intervalley exciton in the presence of a Fermi sea, where free electrons contribute an additional momentum necessary for the optical recombination of the intervalley exciton hole with the doping electron. This couples strongly to the cavity mode and leads to a spectrum with multi-mode hybridization. We also observe a strongly modified optical response at large doping at high frequencies, attributing it to the exotic excited-trion state. Our work lays the solid background for understanding the spectrum of TMDC monolayer excitations at the strong light-matter coupling.

Results

Single-particle states

We start by describing the microscopic theory for polaritons in the electron-doped transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. We consider a generic description valid for different TMDC materials. In our calculations, we use MoS2 as an example. First, we calculate the single-particle states of a single TMDC monolayer. For this, we use the massive Dirac model81 that is well suited to describe the single-particle band structure in the vicinity of K and \({K}^{\prime}=-K\) points of the Brillouin zone. The massive Dirac Hamiltonian reads as (ℏ = 1)

where Δ is the bandgap, vF is the Fermi velocity, kx,y are the electron crystal momentum component, τ takes into account for the valley degrees of freedom and λc,v are the SOC (spin-orbit coupling) constants. In addition, \({\hat{\sigma }}_{x,y,z}\) are pseudospin Pauli matrices acting in the band subspace, \({\hat{\sigma }}_{\pm }=({\hat{\sigma }}_{x}\pm i{\hat{\sigma }}_{y})/2\) are raising and lowering operators, while \({\hat{s}}_{0},{\hat{s}}_{z}\) are identity and spin Pauli Z matrix in the electron spin subspace, respectively. The role played by the SOC is included in the last term of Eq. (1).

We note that the Hamiltonian (1) matches the density functional theory calculations at low energies2,82. Specifically, trions are formed by the states near the K and \({K}^{\prime}\) points and the contribution from states away from the corners of the Brillouin zone are negligible52. Despite the relative simplicity, the model captures all relevant phenomena, including the interplay between the spin and the valley degrees of freedom.

To account for the effects of the dielectric environment, we introduce the bandgap dependence on the substrate and monolayer properties. The bandgap renormalization enters as the scissor shift δ for the bandgap Δ = Δ0 + δ that modifies the bare monolayer bandgap Δ0. The Fermi velocity is then adjusted as \({v}_{F}=\sqrt{{{\Delta }}/2m}\) to preserve the effective mass amplitude83. For the case of MoS2 we consider the effective masses of electrons and holes to be 0.52 m0 (m0 is the free electron mass), bandgap Δ0 of 2.087 eV, λc of 1.41 meV, λv of 74.6 meV, the bulk dielectric constant ε0 of 14, the dielectric thickness of 6 Å, and scissor operator δ equal to 0.64 eV.

Many-particle states

We introduce the interaction between electrons and holes and diagonalize the many-body three-particle Hamiltonian. In TMDC monolayers, the intravalley interaction is described by the screened potential in the Rytova–Keldysh form8,84,85. The Fourier transform of the screened Coulomb between particles in the same valley reads W(q) = V(q)/[ε+(1 + r0q)], where V(q) = 2πe2/q is the bare Coulomb potential in 2D, and q is the magnitude of exchanged wavevector. We use the average substrate permittivity ε+ = (ε2 + ε1)/2 and the screening length r0 = ε0d/286,87. The screened Coulomb potential for the intervalley processes reads W(q) = V(q)/(ε+ + ε0)88. We neglect the wetting layer, vacuum spacing between the monolayer and substrate, which otherwise will modify the potential88,89.

We define the vacuum state \(\left|\oslash \right\rangle\) as a the Fermi sea at temperature T = 0 K and zero doping, which corresponds to empty conduction bands and filed valence bands76. Within the \(\left|\oslash \right\rangle\) configuration, we denote an electron creation operator as \({a}_{c}^{{\dagger} }\) a hole creation operator \({\hat{b}}_{v}^{{\dagger} }={\hat{a}}_{v}\), with c being a conduction band index and v being a valence band index. Finally, we define operators \({\hat{T}}_{\nu }^{{\dagger} }\) (\({\hat{T}}_{\nu }\)) that create (annihilate) trion states \(\left|\nu \right\rangle\) with two electrons in the conduction band (labeled as c1,2) and a hole in the valence band (labeled as v). The corresponding basis is spanned by linear superpositions

with c1,2 referring to the conduction band and \({A}_{\nu ,{c}_{1}{c}_{2}v}\) being amplitudes determined by matrix diagonalization (see Methods). At this point, we stress that the introduced three-body operator can describe both a tightly bound state of two electrons and holes, as well as an electron-hole pair (exciton) in the presence of another electron. We note that the described basis can also be seen as introducing exciton-polarons, where repulsive polarons correspond to excitons dressed by the electron gas, and attractive polaronic modes correspond to trions90. The trion and polaron pictures can be used interchangeably, and we use the former to stress that the binding between particles leads to localized dipole moment and enhancement of strong light-matter coupling.

Using the generalization of the Tamm–Dancoff approach52,76,77,78,79,80, we decompose the full many-body Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}\) in the three-particle state basis and solve the corresponding eigenvalue problem (see Methods for the details).

We obtain the set of low-energy eigenstates and corresponding energies to high precision, which allows describing the optical properties of the system. To classify the states in a trionic basis, we look at the product τsz, with \(\tau ={\tau }_{{c}_{1}}+{\tau }_{{c}_{2}}-{\tau }_{v}\) being the total valley index and \({s}_{z}={s}_{z}^{{c}_{1}}+{s}_{z}^{{c}_{2}}-{s}_{z}^{v}\) being the total spin index. The total spin sz, in general, can have magnitudes 1/2 and 3/2. We restrict our analysis to sz = ± 1/2 spin projections as states that participate in optical recombination processes and neglect spin-3/2 states. The case ∣szτ∣ = 1/2 is a necessary condition for the trion state to be bright. In the numerical procedure, we also account for the symmetries stemming from the conservation of total spin sz and total momentum \({{{\bf{k}}}}={{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{{c}_{1}}+{{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{{c}_{2}}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{v}\).

We model the presence of doping by introducing Pauli blocking by an excessive electron charge through k-space discretization. The k-space grid is arranged as a mesh of N × N points, with the area of the primitive cell being \({{{\Omega }}}_{0}={a}^{2}\sqrt{3}/2\). The doping density can be introduced as n = gvgs/(Ω0N2), where gs and gv are the spin and valley degeneracies, respectively. The corresponding Fermi energy is equal to EF = ℏ2δk2/2m, where \(\delta k=4\pi /(\sqrt{3}aN)\) is the interval between k-points, and a is a lattice constant for the hexagonal lattice. As a result, we can write the relationship between the Fermi energy and the real-space doping level as \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=4{\pi }^{2}{\hslash }^{2}n/(\sqrt{3}{g}_{v}{g}_{s}m)\). Note that the relationship between EF and n is different from the canonical one EF = 2πℏ2n/(gvgsm) corresponding to a circular Fermi surface. The described approach allows obtaining both trion and exciton states in the presence of doping from the three-particle Hamiltonian, and in the zero doping limit (N → ∞) recovers the results from the Bethe-Salpeter equation for the excitonic states52. Therefore, we treat trionic and dressed excitonic states on equal footing and study polaritonic modes in the broad range of doping levels. Note, in the presence of doping the Fermi sea changes, with filling the conduction band up to the Fermi energy. In the following we refer to the Fermi sea as the generic electronic distribution of the sample. However, the definition of vacuum \(\left|\oslash \right\rangle\) does not change, and we continue referring to that as the Fermi sea at zero doping.

Together with eigenenergies of quasiparticles in the TMDC monolayer, we obtain the eigenstates and access various system observables. Specifically, we calculate dipole matrix elements Dν = 〈ν∣d∣c〉 for optical transitions from the three-body state ν to the single electron state c assuming a zero momentum electron-hole pair optical recombination76. Dipole moments are labeled by the corresponding band and read

where dvc is the single-particle dipole matrix element for bands v and c, and \({\delta }_{c,{c}_{1}}\) is a Kronecker delta. It should be noted that from the above expression, it follows that trions with a finite moment also have a coupling with optical cavity mode. However, in our work, based on the assumption of zero temperature, we have calculated trions only with a moment equivalent to the moment of the centers of the K and \({K}^{\prime}=-K\) valleys80.

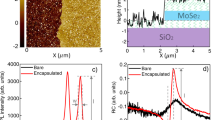

We present the results for a TMDC monolayer (MoS2) in the case of far-detuned optical mode (Fig. 2). The three-particle states are obtained by solving Eq. (9) at different levels of doping, i.e., Fermi energy EF. In Fig. 2a, we plot the first 64 eigenenergies as a function of EF. We observe two dominant sets of modes at low energies for both spin-valley indices τsz = + 1/2 and τsz = − 1/2. The lowest set is attributed to trion-bound states. Trion energies, at around 2.15 eV at small free electron concentrations (EF = 2.93 meV), decrease sublinearly with increasing EF to 2.1 eV at large concentrations. With the increasing doping level, the redshift of the trion line can be attributed to the increase of the excitonic polarizability, which is necessary for the binding of an additional electron. The size of the markers denotes the magnitude of dipole moments and shows the gradual growth of the trion oscillator strength. We also estimated the expected sizes for trions at ~2.1 eV from their charge distributions, which range from 3.0 to 3.5 nm, depending on the doping. As expected, the excitonic modes, which are located ~25 meV above trions, reveal opposite behavior with respect to trions, as they have the largest optical dipole moment at low concentrations. At the same time, with increasing EF we observe gradual redistribution of the oscillator strength between different excitonic modes as well as their blueshifts (Fig. 2a), which can be attributed to the effects of screening and Pauli blocking51,59. We also note the appearance of a higher-lying band of states that gain significant optical dipole moments.

a Doping dependence of the transition energy for three-body states shown by blue circle-shaped markers spin-valley index τsz = −1/2 and (b) by τsz = +1/2. The size of each marker is proportional to its optical oscillator strength. We label the emergent modes as excitons, trions, and excited trions. c The absorption spectrum of an MoS2 monolayer. The purple curve shows the absorption spectrum in the limit of zero doping level, where a single peak corresponds to 1s exciton. The blue curve corresponds to the absorption spectrum of three-particle states with τsz = −1/2 at the level of doping equal to EF = 10.56 meV. The red curve shows the same dependence for τsz = +1/2 three-particle states.

To plot the photoluminescence (PL) in the weak coupling regime, we assign the finite lifetime for each quasiparticle and plot the PL spectrum as a set of Lorentzians (Fig. 2b). Choosing a large doping limit, we observe the strong trion mode, the shifted exciton peak, and an additional brightened quasiparticle at 2.155 eV80. Additionally, we note that together with a radiative process for trions, one can account for non-radiative effects coming from Auger recombination. While in general these are difficult to calculate as they rely on multiparticle scattering, guided by results in GaAs and accounting for increased binding, we estimate the associated linewidth to be ~1 meV at 1011 cm−2 electron concentrations91.

Quasiparticle properties

To understand the nature of quasiparticles, we plot the charge distribution for different states (Fig. 3). This plot shows the contributions of single-particle states with different k into the full three-particle wavefunction for four many-body states. All states in Fig. 3 are bright because all four quasiparticles have direct electron-hole pairs with equal spins. The first state in Fig. 3a represents the trion state, which can be seen from the symmetrical conduction bands occupation. The latter manifests the equivalence between two electrons in the three-particle state.

We show the distribution of various τsz = +1/2 trionic states at EF = 10.56 meV: a -- trion state (attractive polaron), b -- indirect exciton state, c -- direct exciton state (repulsive polaron) and d -- potential excited trion state. The radii of the circles are proportional to the distribution of the charge density of the three-particle state. Energies of each state are indicated in the title of panels. All four states are bright. Both excitons states exhibit Pauli blocking effect, which is observable at the top of the valence band.

The second state in Fig. 3b represents the momentum-indirect exciton state. Indeed, we observe a fully localized exciton-state for electron and hole being in K\({}^{\prime}\) and K valleys, respectively, while the quasi-free electron is located in the K-valley (described by small charge density spreading in the reciprocal space). We also note a signature of Pauli-blocking in the valence band occupation at K point. The Pauli blocking effect is present in the conduction band, however, this cannot be observed in the diagrams of the trion charge density distribution as there is a doping charge that occupies the self-blocked space. The third state, shown in Fig. 3c, is the direct exciton with the Pauli-blocking signature in the valence band occupation, plus quasi-free electron in the same valley. Finally, the fourth state in Fig. 3d energetically is located above three previous states but does not exhibit Pauli blocking signature in the valence band occupation and has an s orbital-like occupation. It features the charge distribution that corresponds to trion modes. We thus conclude that it is an optically active 2s trion state, which was experimentally observed92. We have shown only a few states, which correspond only to the τsz = + 1/2 states. However, there are much more optically active three-particle states. For example, there are at least three optically active fully symmetrical trion states93. We anticipate similar behavior for the indirect/direct excitons and the excited trion states.

Light-matter coupling

Next, we consider a planar photonic microcavity system with a doped monolayer of TMDC placed in the antinode (Fig. 1). Confined cavity photons tuned in resonance with TMDC modes will couple strongly to excitonic and trionic optical transitions, resulting in a polaritonic spectrum with substantial modifications. To describe TMDC polaritons at increasing doping, we use the diagrammatic approach that allows treating light-matter coupling in a general form. We note that recently the question of non-perturbative ab initio simulations of exciton-polariton in TMDCs was addressed in94, where the authors concentrated on two-body complexes. Green’s function approach was also used to study trions and exciton-trion-polaritons in TMDC monolayers, emphasizing low-energy excitations57,95,96,97. Finally, diagrammatic techniques were also used in69 focused on describing the qualitative effects of enhancing polariton-electron scattering and building a corresponding analytical theory. Distinctly from other works, in our considerations, we study the full spectrum of quasiparticles emerging at non-zero doping and analyze polaritonic spectra at varying cavity detuning.

Let us consider bare cavity photons and their coupling to TMDC excitations enabled by a non-zero dipole moment. The approach is applicable to both exciton-like and trion-like modes as long as their dipole moments have a projection on the electric field of the cavity mode. We note that in the low density regime, the strong coupling is mostly coming from the excitonic modes, while trions become increasingly relevant at high doping. While in general, one can consider the bare Green’s function of cavity photons G0(ω, q) with wavevector q, in practice, we are interested in 0D open cavities39,63 and fiber cavities58, where only q → 0 mode is considered (and thus assume small photon momenta in the following discussion). We obtain the polaritonic Green’s function by dressing the photonic Green’s function with relevant excitation in the system. Specifically, we assume a cavity photon with momentum q ≈ 0 is converted into an electron-hole pair with zero center-of-mass momentum while coupling to an electron with some wavevector k > kF. This process is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 4, where multiple absorption and re-emission of a cavity photon lead to the mode hybridization98,99. Notably, this is a non-perturbative approach where the dressed propagator can be found exactly by solving the corresponding Dyson equation. In the algebraic form, the solution reads

where

with ωcav being the resonant frequency of a cavity at normal incidence, γcav the broadening of the photonic linewidth due to a finite transmission coefficient of the cavity mirrors. The self-energy Σ(ω) describes material excitations and accounts for the interaction vertices defined by the strength of light-matter interaction. It reads

where Ων are Rabi frequencies of transitions, ϵν are their resonant frequencies, and γν are non-radiative broadenings, depending on the quality of a sample. In total, we account for d = 64 transitions coming from the exact diagonalization and presented in Fig. 2a. The broadenings are chosen based on typical experimentally achievable parameters.

The bare cavity photon propagator (thin wavy curve) is dressed via multiple absorption and re-emission processes by TMDC excitations (Σ). The dressed cavity photon Green’s function is depicted by a thick wavy curve. The solution of this diagrammatic equation is written in Eq (4) in the algebraic form.

The light-matter interaction is defined by the optical dipole moments of transitions and the amplitude of the electric field (or vector potential) for the cavity mode. The associated Rabi frequencies are

where A is the cavity area, and Dν are dipole matrix elements of the transitions given by Eq. (3).

We note that in the single-particle picture, the oscillator strength of an individual electron-hole excitation is independent of the number of atoms, while the free electron-hole band-to-band excitations scales with the number of atoms in the sample. However, a bound exciton captures a macroscopic fraction of the free particle excitation spectral weight100,101. As a result, the optical transition dipole matrix element of the bound exciton becomes proportional to the square root of the number of atoms or area of the sample. In reality, the photon wavelength or the exciton coherence determine the relevant length scale and hence the dipole matrix element. We implicitly assumed that the sample size is smaller than both the photon wavelength and trion coherence length. Similarly, our calculations of the transition dipole of strongly bound trions gives the superradiant factor \(\sqrt{A}\) in the dipole matrix element Dν in Eq. (7). Thus, the final result for the Rabi frequency does not depend on the sample area A. At the same time, we find that trion transition dipole scales with the carrier density n as \(\sqrt{n}\), which is consistent with the measurements of trions in two-dimensional quantum wells102.

An important consequence of cavity photon dressing by TMDC excitations corresponds to hybridization of exciton and trion-dominant modes, as can be seen from the modification of poles of G(ω) for couplings ∣Ων∣ that dominate broadenings γν. The imaginary part of G(ω) then represents the absorption spectrum of the polaritonic system (up to scaling constant)99. In the next section, we proceed to calculate the polaritonic spectrum at different cavity mode frequencies and discuss the results.

Cavity polariton setup

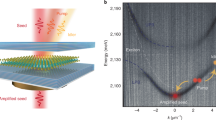

We consider a cavity polariton setup (see the sketch in Fig. 1) where excitons and trions couple to a single cavity mode with a tunable frequency. The system can be conveniently realized in open or fiber cavities39,63, where 0D cavity resonance can be shifted by cavity length change with a piezodrive, which allows coupling to excitations at energies ~2 eV and resulting anticrossing of various modes. Using the developed theory and extensive numerical calculations, we present polaritonic spectra for varying TMDC doping. We concentrate on the gated MoS2 monolayer case and cover a broad range of densities. It is convenient to present the doping level using the Fermi energy EF for the free electron gas. We start with an intrinsic value of EF = 2.92 meV and move up to larger doping levels up to EF = 29.3 meV. We plot the absorption spectra of the polaritonic system in Fig. 5, showing its modification at increasing EF. Here we assume mode broadening of γ = 1 meV being characteristic to modern setups63. Due to light-matter coupling with several modes simultaneously, we observe several distinct polaritonic modes with separate anticrossings.

Absorption is shown as a function of detuning for increasing Fermi energy (left-to-right). We consider σ+ polarization for the cavity mode. Color bars define the intensity in arbitrary units. In all the spectra, from low (3.26 meV) to high (29.34 meV) Fermi energy, we see the emergence of trion modes at ~2.1 eV with considerable Rabi splitting (~10 meV), being significantly larger than the broadening γ = 1 meV. The exciton-polariton features the appearance of the additional mode inside the polaritonic gap. The additional splitting at high free electron concentration is attributed to the higher-order trion state.

At low doping in (Fig. 5a), we observe two clear anticrossings between the cavity mode and three-body excitations, corresponding to bound trions and 1s exciton states renormalized by the interaction with free electrons69,95. While the excitonic response dominates at higher energies, we note the significant oscillator strength for the low-energy trion modes and a clear sign of anti-crossing. Taking the lowest bright trion (attractive polaron) as an example, we check that the effective Rabi energy for this mode (Eq. (7)) is equal to 4.2 meV at EF = 3.26 meV, being larger than 1 meV broadening. At the same time, we note that due to our system’s multi-mode structure, the splitting between modes has to be estimated directly from the spectrum, as we show later in Fig. 6.

a Trion polariton energy splitting as a function of the square root of electron density (red circles and blue curve). We confirm the linear increase of splitting at low densities EF ≤ 16.5 meV (cf. orange line). However, at large free electron densities, we see the growth becomes sublinear in \(\sqrt{{n}_{e}}\). b Intensity profile for polaritonic spectrum at large doping (EF = 29.34 meV). The cavity mode energy is tuned to 2.11 eV, being in resonance with the trion mode. The first two consecutive peaks correspond to trion-polaritons, with the Rabi splitting of 18 meV.

At intermediate doping in (Fig. 5b, c), the most pronounced effects are: (1) the increase of trion-polariton splitting; (2) qualitative change of exciton-polariton coupling. For point (1), we track the energy splitting at resonant detuning and plot it as a function of the square root of the Fermi energy (and electron concentration), \(\sqrt{{E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}\). There is a known linear scaling of the trion-polariton splitting64,91,102,103, and we confirm the expected scaling at small and intermediate doping levels (see details in Fig. 6a). Specifically, we show how the trion energy splitting grows, comparing numerical results (red circles and blue curve in Fig. 6a) with the linear scaling (Fig. 6a, yellow line). For point (2), we note the qualitative SC change due to the brightening of the intervalley exciton mode, which becomes possible at the finite doping as optical recombination of an exciton hole with a doping electron becomes allowed with increased EF52. As this mode is located at the middle of the polariton gap, the anticrossing takes shape characteristic to dipolaritons — hybrid three-mode quasiparticles that arise from strong coupling of direct excitons to photons and tunneling coupling between indirect and direct excitons104,105,106. This anticrossing features flat dependence on the cavity mode energy (Fig. 5c, d). This feature enriches the polaritonic spectrum, which was overlooked in the previous theoretical analysis62,95.

As doping level grows to the point when Fermi energy becomes of the order of trion binding energy, i.e., EF ~ 20 meV, additional polaritonic modes emerge from excitonic modes dressed by the Fermi sea. We observe several modes that gain the oscillator strength at EF = 10.56 meV (in Fig. 5e, see spectral features at around 2.18 eV. These are attributed to the excited trion states, as follows from the charge distribution analysis presented below and in Fig. 3. Results obtained from our microscopic theory in the large doping limit have several remarkable features (Fig. 5f). The trion splitting is large in absolute values and reaches 18 meV value at EF = 29.34 meV (see spectrum cross-section in Fig. 6b). At resonance with the trion mode, the cross-section shows two dominant peaks and weakly coupled excitonic modes at higher energies. The splitting shows a sublinear dependence with \(\sqrt{{E}_{F}}\), which can be attributed to the increase of the role of the effects of the Pauli blocking and redistribution of the oscillator strength. However, we stress that strong coupling to trions remains at all doping levels.

An essential consequence of strong coupling in MoS2 monolayers is the qualitative change of the ground state properties. The three-body quasiparticles of a bare monolayer include four trionic modes, with the optically spin-forbidden dark mode being energetically favorable (see Fig. 7a), which is composed of a spin-triplet electron-hole pair and a spin-singlet electron-electron pair93. Qualitatively, this ground state corresponds to the suppressed photoluminescence from an uncoupled system. Similar physics is observed in carbon nanotubes, where tightly bound excitons have zero optical dipole moments107. The situation changes dramatically when the TMDC monolayer is placed in the optical cavity, where strong coupling modifies energies and redistributed dipole moments (Fig. 7b). In this case, a pair of polariton modes formed from the bright trion, and the lower one can go beyond the energy of a dark trion uncoupled to light, as shown in Fig. 1. This situation resembles the ground state brightening that can happen for carbon nanotubes embedded in a microcavity108. As a consequence, the ground state of the system now becomes optically active.

We observe the qualitative change of the ground state due to strong light-matter coupling. a Doping dependence of trion energies (y axis) and their dipole moment (circle size). The lowest trion mode is dark (orange dashed line) for the uncoupled case, which leads to suppression of the photoluminescence. b Doping dependence of trion polaritons in MoS2 monolayer, where cavity mode is tuned close in energy to trion modes. The cavity-modified ground state is bright, thus enabling efficient photoluminescence from the system. The cavity mode is at E0 = 2.14 eV and we consider linear polarization.

Discussion

We have developed a microscopic theory that describes strong light-matter coupling in doped TMDC monolayers in a wide range of free electron concentrations. The theory involves a numerical calculation of a set of three-body excitations, which are then coupled non-perturbatively to the cavity mode. We have calculated polariton spectra using this approach, revealing the rich structure of the emerging composite light-matter quasiparticles. Our results confirm the robust nature of trion polaritons that holds in a large range of electron concentrations. At intermediate doping levels, we observe the three-mode structure of exciton-polaritons, where the presence of the additional mode in the middle of the polariton gap changes the anticrossing behavior qualitatively. Also, we predict that in polaritonic samples with large doping, the oscillator strength of the excited trion state becomes significant and may drive the system into a strong coupling regime with exotic charge distribution. Finally, we have demonstrated that increasing the electron concentration changes the nature of the system’s ground state from dark to bright. Our results are crucial for building electrically tunable nonlinear polaritonic devices based on 2D materials.

Methods

Excitons Wannier Equation

To calculate the energy spectrum and wavefunctions of many-body state we use the generalization of the Tamm–Dancoff approach52,76,77,78,79,80. We start by decomposing the full many-body Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}\) in the three-particle state basis (Eq. (2)). Next, we solve the corresponding eigenvalue problem. In the trion basis, the full many-body Hamiltonian consists of several parts, \(\hat{H}={\hat{H}}_{0}+{\hat{H}}_{c,c}+{\hat{H}}_{c,v}\), with \({\hat{H}}_{0}\) being the free-electron Hamiltonian, \({\hat{H}}_{c,c}\) the Coulomb coupling between electrons, and \({\hat{H}}_{c,v}\) the Coulomb coupling between electrons and holes. Explicitly, these terms read

where \({W}_{{a}^{\prime}{b}^{\prime}}^{ab}=W({{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{a}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{{a}^{\prime}})\langle {a}^{\prime}| a\rangle \langle b| {b}^{\prime}\rangle\) and \({V}_{{a}^{\prime}{b}^{\prime}}^{ab}=V({{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{a}-{{{{\bf{k}}}}}_{{a}^{\prime}})\langle {a}^{\prime}| a\rangle \langle b| {b}^{\prime}\rangle\) are screened and bare Coulomb matrix elements, respectively. εc,v are free particle energy terms for the conduction (c) and the valence (v) band.

Being eigenstates of the full many-body Hamiltonian, one can find the elements of A by solving the eigenvalue problem

where matrix elements \({H}_{{c}_{1}{c}_{2}v}^{{c}_{1}^{\prime}{c}_{2}^{\prime}{v}^{\prime}}\) are described in52.

A direct solution of Eq. (9) is an extremely challenging task due to the high dimensionality of the trion Hamiltonian, which is proportional to \({N}_{v}{N}_{c}^{2}{N}_{k}^{2}\), where Nv is a number of valence bands, Nc is a number of conduction bands, and Nk is a number of k-points. For the converged calculations, the linear dimensions of the Hamiltonian matrix are more than ~106 states. In the case of two-body exciton Hamiltonian, the dimensionality scales significantly slow as NvNcNk. However, the trion Hamiltonian matrix is sparse, with about 1% of the nonzero matrix elements. Therefore, we use the Arnoldi algorithm109, which is implemented in ARPACK110, for obtaining low-energy eigenstates.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All the codes were implemented using home-built programs, which use standard open-source software packages.

References

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Kormányos, A. et al. k ⋅ p theory for two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. 2D Mater. 2, 022001 (2015).

Miwa, J. A. et al. Electronic structure of epitaxial single-layer mos2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 046802 (2015).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 12, 207 (2012).

Splendiani, A. et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 10, 1271 (2010).

Steinleitner, P. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast exciton formation in a monolayer of WSe2. Nano Lett. 17, 1455 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Colloquium : excitons in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 021001 (2018).

Keldysh, L. V. Coulomb interaction in thin semiconductor and semimetal films. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 29, 658 (1979).

Glazov, M. M. & Chernikov, A. Breakdown of the static approximation for free carrier screening of excitons in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Status Solidi 255, 1800216 (2018).

Hüser, F., Olsen, T. & Thygesen, K. S. How dielectric screening in two-dimensional crystals affects the convergence of excited-state calculations: Monolayer mos2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 245309 (2013).

Chernikov, A. et al. Exciton binding energy and nonhydrogenic rydberg series in monolayer ws2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 076802 (2014).

Xia, F., Wang, H., Xiao, D., Dubey, M. & Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899 (2014).

Radisavljevic, B., Whitwick, M. B. & Kis, A. Integrated circuits and logic operations based on single-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 5, 9934 (2011).

Wang, H. et al. Integrated circuits based on bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nano Lett. 12, 4674 (2012).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497 (2013).

Perkins, F. K. et al. Chemical vapor sensing with monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 13, 668 (2013).

Feng, J., Qian, X., Huang, C.-W. & Li, J. Strain-engineered artificial atom as a broad-spectrum solar energy funnel. Nat. Photonics 6, 866 (2012).

Pospischil, A., Furchi, M. M. & Mueller, T. Solar-energy conversion and light emission in an atomic monolayer p–n diode. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 257 (2014).

Flatten, L. C. et al. Microcavity enhanced single photon emission from two-dimensional WSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 191105 (2018).

Baek, H. et al. Highly energy-tunable quantum light from moiré-trapped excitons. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba8526 (2020).

Kockum, A. F., Miranowicz, A., Liberato, S. D., Savasta, S. & Nori, F. Ultrastrong coupling between light and matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 19 (2019).

Basov, D. N., Asenjo-Garcia, A., Schuck, P. J., Zhu, X. & Rubio, A. Polariton panorama. Nanophotonics 10, 549 (2020).

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose–einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409 (2006).

Schneider, C. et al. An electrically pumped polariton laser. Nature 497, 348 (2013).

Ballarini, D. et al. Macroscopic two-dimensional polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 215301 (2017).

Carusotto, I. & Ciuti, C. Quantum fluids of light. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 299 (2013).

Askitopoulos, A. et al. Polariton condensation in an optically induced two-dimensional potential. Phys. Rev. B 88, 041308 (2013).

Ohadi, H. et al. Spin order and phase transitions in chains of polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 067401 (2017).

Gao, T. et al. Controlled ordering of topological charges in an exciton-polariton chain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 225302 (2018).

Mietki, P. & Matuszewski, M. Spontaneous formation of spin lattices in semimagnetic exciton-polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195303 (2018).

Kyriienko, O., Sigurdsson, H. & Liew, T. C. H. Probabilistic solving of np-hard problems with bistable nonlinear optical networks. Phys. Rev. B 99, 195301 (2019).

Liew, T., Shelykh, I. & Malpuech, G. Polaritonic devices. Phys. E Low. Dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 43, 1543 (2011).

Ohadi, H. et al. Spontaneous spin bifurcations and ferromagnetic phase transitions in a spinor exciton-polariton condensate. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031002 (2015).

Kyriienko, O. & Liew, T. C. H. Exciton-polariton quantum gates based on continuous variables. Phys. Rev. B 93, 035301 (2016).

Askitopoulos, A. et al. All-optical quantum fluid spin beam splitter. Phys. Rev. B 97, 235303 (2018).

Opala, A., Ghosh, S., Liew, T. C. & Matuszewski, M. Neuromorphic computing in ginzburg-landau polariton-lattice systems. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064029 (2019).

Schwarz, S. et al. Two-dimensional metal–chalcogenide films in tunable optical microcavities. Nano Lett. 14, 7003 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Strong light–matter coupling in two-dimensional atomic crystals. Nat. Photonics 9, 30 (2014).

Dufferwiel, S. et al. Exciton–polaritons in van der waals heterostructures embedded in tunable microcavities. Nat. Commun. 6, 8579 (2015).

Lundt, N. et al. Monolayered MoSe 2 : a candidate for room temperature polaritonics. 2D Mater. 4, 015006 (2016).

Schneider, C., Glazov, M. M., Korn, T., Höfling, S. & Urbaszek, B. Two-dimensional semiconductors in the regime of strong light-matter coupling. Nat. Commun. 9, 2695 (2018).

Zhang, L., Gogna, R., Burg, W., Tutuc, E. & Deng, H. Photonic-crystal exciton-polaritons in monolayer semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 9, 713 (2018).

Stührenberg, M. et al. Strong light–matter coupling between plasmons in individual gold bi-pyramids and excitons in mono- and multilayer WSe2. Nano Lett. 18, 5938 (2018).

Yankovich, A. B. et al. Visualizing spatial variations of plasmon–exciton polaritons at the nanoscale using electron microscopy. Nano Lett. 19, 8171 (2019).

Gonçalves, P. A. D., Stenger, N., Cox, J. D., Mortensen, N. A. & Xiao, S. Strong light–matter interactions enabled by polaritons in atomically thin materials. Adv. Optical Mater. 8, 1901473 (2020).

Ugeda, M. M. et al. Giant bandgap renormalization and excitonic effects in a monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 13, 1091 (2014).

Chernikov, A., Ruppert, C., Hill, H. M., Rigosi, A. F. & Heinz, T. F. Population inversion and giant bandgap renormalization in atomically thin WS2 layers. Nat. Photonics 9, 466 (2015).

Chernikov, A. et al. Electrical tuning of exciton binding energies in monolayer ws2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 126802 (2015).

Withers, F. et al. Light-emitting diodes by band-structure engineering in van der waals heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 14, 301 (2015).

Raja, A. et al. Coulomb engineering of the bandgap and excitons in two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 15251 (2017).

Shahnazaryan, V., Kozin, V. K., Shelykh, I. A., Iorsh, I. V. & Kyriienko, O. Tunable optical nonlinearity for transition metal dichalcogenide polaritons dressed by a fermi sea. Phys. Rev. B 102, 115310 (2020).

Zhumagulov, Y. V., Vagov, A., Senkevich, N. Y., Gulevich, D. R. & Perebeinos, V. Three-particle states and brightening of intervalley excitons in a doped mos2 monolayer. Phys. Rev. B 101, 245433 (2020).

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrical control of neutral and charged excitons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1474 (2013).

Singh, A. et al. Trion formation dynamics in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 93, 041401 (2016).

Courtade, E. et al. Charged excitons in monolayer WSe2 : experiment and theory. Phys. Rev. B 96, 085302 (2017).

Lundt, N. et al. The interplay between excitons and trions in a monolayer of MoSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 031107 (2018).

Rana, F., Koksal, O. & Manolatou, C. Many-body theory of the optical conductivity of excitons and trions in two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085304 (2020).

Sidler, M. et al. Fermi polaron-polaritons in charge-tunable atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Phys. 13, 255 (2016).

Efimkin, D. K. & MacDonald, A. H. Many-body theory of trion absorption features in two-dimensional semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 95, 035417 (2017).

Ravets, S. et al. Polaron polaritons in the integer and fractional quantum hall regimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 057401 (2018).

Chang, Y.-C., Shiau, S.-Y. & Combescot, M. Crossover from trion-hole complex to exciton-polaron in n-doped two-dimensional semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 98, 235203 (2018).

Tan, L. B. et al. Interacting polaron-polaritons. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021011 (2020).

Emmanuele, R. P. A. et al. Highly nonlinear trion-polaritons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 11, 3589 (2020).

Kyriienko, O., Krizhanovskii, D. N. & Shelykh, I. A. Nonlinear quantum optics with trion polaritons in 2d monolayers: Conventional and unconventional photon blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 197402 (2020).

Shahnazaryan, V., Iorsh, I., Shelykh, I. A. & Kyriienko, O. Exciton-exciton interaction in transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115409 (2017).

Barachati, F. et al. Interacting polariton fluids in a monolayer of tungsten disulfide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 906 (2018).

Kravtsov, V. et al. Nonlinear polaritons in a monolayer semiconductor coupled to optical bound states in the continuum. Light. Sci. Appl. 9, 56 (2020).

Stepanov, P. et al. Exciton-exciton interaction beyond the hydrogenic picture in a mose2 monolayer in the strong light-matter coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 167401 (2021).

Li, G., Bleu, O., Parish, M. M. & Levinsen, J. Enhanced scattering between electrons and exciton-polaritons in a microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 197401 (2021).

Li, G., Bleu, O., Levinsen, J. & Parish, M. M. Theory of polariton-electron interactions in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 103, 195307 (2021).

Bastarrachea-Magnani, M. A., Camacho-Guardian, A. & Bruun, G. M. Attractive and repulsive exciton-polariton interactions mediated by an electron gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 127405 (2021).

Denning, E. V., Wubs, M., Stenger, N., Mork, J. & Kristensen, P. T. Quantum theory of two-dimensional materials coupled to electromagnetic resonators. Phys. Rev. B 105, 085306 (2022).

Denning, E. V., Wubs, M., Stenger, N., Mork, J. & Kristensen, P. T. Cavity-induced exciton localisation and polariton blockade in two-dimensional semiconductors coupled to an electromagnetic resonator. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, L012020 (2022).

Anton-Solanas, C. et al. Bosonic condensation of exciton–polaritons in an atomically thin crystal. Nat. Mater. 20, 1233 (2021).

Shan, H. et al. Coherent light emission of exciton-polaritons in an atomically thin crystal at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 12, 6406 (2021).

Deilmann, T., Drüppel, M. & Rohlfing, M. Three-particle correlation from a many-body perspective: trions in a carbon nanotube. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 196804 (2016).

Drüppel, M., Deilmann, T., Krüger, P. & Rohlfing, M. Diversity of trion states and substrate effects in the optical properties of an MoS2 monolayer. Nat. Commun. 8, 2117 (2017).

Torche, A. & Bester, G. First-principles many-body theory for charged and neutral excitations: trion fine structure splitting in transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 100, 201403 (2019).

Tempelaar, R. & Berkelbach, T. C. Many-body simulation of two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy of excitons and trions in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 10, 3419 (2019).

Zhumagulov, Y. V., Vagov, A., Gulevich, D. R., Junior, P. E. F. & Perebeinos, V. Trion induced photoluminescence of a doped MoS2 monolayer. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 044132 (2020).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Zollner, K., Junior, P. E. F. & Fabian, J. Strain-tunable orbital, spin-orbit, and optical properties of monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 100, 195126 (2019).

Waldecker, L. et al. Rigid band shifts in two-dimensional semiconductors through external dielectric screening. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 206403 (2019).

Rytova, N. S. The screened potential of a point charge in a thin film. Mosc. Univ. Phys. Bull. 3, 18 (1967).

Cudazzo, P., Tokatly, I. V. & Rubio, A. Dielectric screening in two-dimensional insulators: implications for excitonic and impurity states in graphane. Phys. Rev. B 84, 085406 (2011).

Berkelbach, T. C., Hybertsen, M. S. & Reichman, D. R. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045318 (2013).

Cho, Y. & Berkelbach, T. C. Environmentally sensitive theory of electronic and optical transitions in atomically thin semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 97, 041409 (2018).

Florian, M. et al. The dielectric impact of layer distances on exciton and trion binding energies in van der waals heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 2725 (2018).

Shahnazaryan, V., Kyriienko, O. & Rostami, H. Exciton routing in the heterostructure of a transition metal dichalcogenide monolayer on a paraelectric substrate. Phys. Rev. B 100, 165303 (2019).

Glazov, M. M. Optical properties of charged excitons in two-dimensional semiconductors. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 034703 (2020).

Ramon, G., Mann, A. & Cohen, E. Theory of neutral and charged exciton scattering with electrons in semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 67, 045323 (2003).

Arora, A. et al. Excited-state trions in monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 167401 (2019).

Zhumagulov, Y. V., Vagov, A., Gulevich, D. R. & Perebeinos, V. Electrostatic control of the trion fine structure in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.11800 (2021).

Latini, S., Ronca, E., Giovannini, U. D., Hübener, H. & Rubio, A. Cavity control of excitons in two-dimensional materials. Nano Lett. 19, 3473 (2019).

Rana, F. et al. Exciton-trion polaritons in doped two-dimensional semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 127402 (2021).

Rana, F., Koksal, O., Jung, M., Shvets, G. & Manolatou, C. Many-body theory of radiative lifetimes of exciton-trion superposition states in doped two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 103, 035424 (2021).

Koksal, O. et al. Structure and dispersion of exciton-trion-polaritons in two-dimensional materials: experiments and theory. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033064 (2021).

Levinsen, J., Li, G. & Parish, M. M. Microscopic description of exciton-polaritons in microcavities. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 033120 (2019).

Kyriienko, O. & Shelykh, I. A. Intersubband polaritonics revisited. J. Nanophotonics 6, 1 (2012).

Hanamura, E. Rapid radiative decay and enhanced optical nonlinearity of excitons in a quantum well. Phys. Rev. B 38, 1228 (1988).

Perebeinos, V., Tersoff, J. & Avouris, P. Radiative lifetime of excitons in carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 5, 2495 (2005).

Rapaport, R. et al. Negatively charged quantum well polaritons in a GaAs/AlAs microcavity: an analog of atoms in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1607 (2000).

Rapaport, R., Cohen, E., Ron, A., Linder, E. & Pfeiffer, L. N. Negatively charged polaritons in a semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B 63, 235310 (2001).

Cristofolini, P. et al. Coupling quantum tunneling with cavity photons. Science 336, 704 (2012).

Kyriienko, O., Kavokin, A. V. & Shelykh, I. A. Superradiant terahertz emission by dipolaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 176401 (2013).

Rosenberg, I. et al. Strongly interacting dipolar-polaritons. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat8880 (2018).

Perebeinos, V., Tersoff, J. & Avouris, P. Scaling of excitons in carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 257402 (2004).

Shahnazaryan, V. A., Saroka, V. A., Shelykh, I. A., Barnes, W. L. & Portnoi, M. E. Strong light-matter coupling in carbon nanotubes as a route to exciton brightening. ACS Photonics 6, 904 (2019).

Arnoldi, W. E. The principle of minimized iterations in the solution of the matrix eigenvalue problem. Q. Appl. Math. 9, 17 (1951).

Lehoucq, R. B., Sorensen, D. C. & Yang, C. Arpack users guide: solution of large scale eigenvalue problems by implicitly restarted arnoldi methods (1997).

Center for Computational Research, University at Buffalo; http://hdl.handle.net/10477/79221.

Acknowledgements

Y.V.Z. is grateful to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) SPP 2244 (Project-ID 443416183) for the financial support. The work of D.R.G. related to the numerical calculation of the structure of three-body states was supported by Russian Science Foundation (project 20-12-00224). I.A.S. acknowledges support from Icelandic Research Fund (project “Hybrid polaritonics”) and Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR, joint RFBR-DFG project No. 21-52-12038). S.C. and O.K. acknowledge the support from UK EPSRC New Investigator Award under the Agreement No. EP/V00171X/1. V.P. acknowledges support from the Vice President for Research and Economic Development (VPRED) at the University at Buffalo, SUNY Research Seed Grant Program, and the Center for Computational Research at the University at Buffalo111.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.V.Z. performed numerical calculations of trion spectra, with contributions from V.P. and D.R. G.S.C. performed calculations for polaritonic spectra and prepared the figures. I.A.S. formulated the original idea of the work. O.K., I.A.S., and V.P. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript, with crucial contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhumagulov, Y.V., Chiavazzo, S., Gulevich, D.R. et al. Microscopic theory of exciton and trion polaritons in doped monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. npj Comput Mater 8, 92 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00775-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00775-x

This article is cited by

-

Room-temperature spin-layer locking of exciton–polariton nonlinearities in a WS2 microcavity

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Theory of magnetotrion-polaritons in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2024)

-

Interspecies exciton interactions lead to enhanced nonlinearity of dipolar excitons and polaritons in MoS2 homobilayers

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Two-dimensional coherent spectroscopy of trion-polaritons and exciton-polaritons in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides

AAPPS Bulletin (2023)