Abstract

The identification of the ground state phases of a chemical space in the convex hull analysis is a key determinant of the synthesizability of materials. Online material databases have been instrumental in exploring one aspect of the synthesizability of many materials, namely thermodynamic stability. However, the vibrational stability, which is another aspect of synthesizability, of new materials is not known. Applying first principles approaches to calculate the vibrational spectra of materials in online material databases is computationally intractable. Here, a dataset of vibrational stability for ~3100 materials is used to train a machine learning classifier that can accurately distinguish between vibrationally stable and unstable materials. This classifier has the potential to be further developed as an essential filtering tool for online material databases that can inform the material science community of the vibrational stability or instability of the materials queried in convex hulls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A major challenge in materials science is determining whether a material can be successfully synthesised. New hypothesised materials are being continuously added to a growing number of online material databases such as: MaterialsProject.org1, which currently hosts more than 140,000 inorganic crystals; the AFLOW.org2 with over 3.5 million; the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)3 with over 560,000, and the C2DB4 with over 3000 two-dimensional (2D) materials. The presence of these hypothesised materials has greatly expanded the applicability of the material databases; some of these materials have been predicted to be potential candidates for applications in many areas such as photonics5, medicine6,7,8 superconductivity9, energy10,11 and programmable materials12. However, many of the hypothesised materials are not synthesizable13 and one should apply ’synthesizability filters’ before attempting to synthesise these materials. A key synthesizability filter provided in these databases for each material is the energy above the convex hull EH, which indicates how likely a material is to exist in nature, or to be synthesised. Values for EH lower than 100 meV are typically perceived as an indication of the thermodynamic stability of the material14, and this filter has been central to several reports that outlined material synthesis pathways14,15,16.

However, to ascertain the possibility of synthesis of a material, or its possible existence in nature, another criterion must be fulfilled: the material’s vibrational stability17. Vibrationally unstable materials are those whose vibrational dispersion possesses imaginary phonon modes, and therefore does not exist on a minimum in the system’s potential energy surface. Materials could possess very low EH values, yet be vibrationally unstable. Examples of those materials are LiZnPS4 (mp-11175) with EH = 0 meV, SiC (mp-11713) with EH = 3 meV and Ca3PN (mp-11824) with EH = 0 meV, where EH values are obtained from the MaterialsProject database for each material labelled by its material ID, and the vibrational instability is provided by the dataset of ref. 18. Thus, convex hull information cannot be taken at face value; ideally, a given materials database should provide a filter that indicates both vibrational and thermodynamic stability, regardless of a low EH value. Such a filter would enhance the applicability of, as well as the confidence in, materials databases, but at present, this filter is not available.

The realisation of this ideal scenario is, however, practically challenging because of the enormous computational cost of calculating the vibrational spectra of materials using density functional theory (DFT), as the periodic supercell inherent to the calculation becomes larger18. However, if a sufficiently large dataset of vibrational stability was available, then a classification machine learning (ML) model can be trained on the data for the prediction of the vibrational stability of any material. ML can provide a massive speed-up in the calculation time, as well as a large reduction in the computational resources required. Our goal in this work is to explore the relationships between the structure of inorganic crystals and their vibrational stability using ML approaches for the rapid discovery of new classes of stable inorganic crystals. While there has been only one preprint that has reported an attempt to address this problem using ML (limited to 2D materials)19, there have been several reports on using ML to solve a related problem: predicting the vibrational properties, such as the entropy, using ML. Legrain et al.13,20 and ref. 21 reported on the successful prediction of the vibrational properties of vibrationally stable materials by applying ML.

Applying ML requires data, and a number of datasets of vibrational spectra for materials have been published, but they represent only a small fraction of materials available in online databases. Petretto et al.18 published the vibrational dispersion, as well as quantities that are calculated based on the vibrational dispersion, for a subset of 1521 semiconductors in MaterialsProject.org using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT). The number of materials that are vibrationally unstable in their dataset is 232 (~15%). Choudhary et al.22 identified 21% of 5015 materials in the JARVIS-DFT database23 as unstable using DFPT. Using the finite difference method for the vibrational calculations, a database of ~10 K materials is available at the phonopy website (http://phonondb.mtl.kyoto-u.ac.jp/), but the authors did not make the output of the phonon calculations text-retrievable. Here, we generate a dataset of vibrational stability of ~3100 materials from MaterialsProject using a workflow that involves the application of the finite difference method, and we have made the results available in a Github repository https://github.com/sheriftawfikabbas/crystalfeatures/tree/master/vibrational_stability. We train ML classification models using this data to accurately predict which materials are most likely stable/unstable. These ML models bring the advantage of predicting the vibrational stability within a few seconds, which is orders of magnitude faster than performing such calculations from first principles.

Results and discussion

Classification model

The results of training our classification model on the pristine dataset are displayed in Table 1. As the number of data points for the unstable class was only about half of that of the stable class, the classification performance for the unstable class is lower, with f1-score values lower than 0.6. The distribution of the data is, therefore, insufficient for obtaining accurate classification for both classes of materials.

As the dataset was divided into train folds, synthetic data was introduced into train folds using the SMOTE and mixup methods. The model was trained on the augmented train folds. We note that no synthetic data were added to the test fold as it is used to evaluate the trained model. The classification accuracy measures (precision, recall, and f1-score) were then calculated for the test fold. Figure 1 provides an outline of the process used to train and test our ML model.

After training the model on a single training fold, the model was then evaluated on the test set. Average/maximum scores for precision, recall, and f1-score are reported for both classes. The evaluation of all five models on test sets are shown in Table 2.

The synthetic data helped to increase the number of unstable data points, which led to better performance of the model. The average recall score for the unstable class increased from 42 to 68%, while the average f1-score increased from 53 to 63%. Moreover, the mean AUC score across the fivefolds was 0.73 (Fig. 2), which means that the model overall is performing well. The minority f1-score of 63% that was achieved by the model is significant, considering the limited information on the minority class and the challenging nature of the problem.

Model calibration

When using imbalanced training sets, ML models may sometimes not be well calibrated, i.e. the class distribution of the model predictions may not match the distribution of ground truth class labels. We examined the calibration of the model on each of the test folds by comparing the percentage of ground truth labels for unstable/stable with the percentage of the predicted label for unstable/stable and report the average percentages across fivefolds in Table 3. For the unstable class, the average number of data points are 32%, while our model predicts 36% of the data points as unstable on average across fivefolds. Similarly, for stable materials, the average number of data points are 68%, while our model predicts 64% of the data points as stable (on average) across fivefolds. The difference in distribution between the true labels and predicted labels is less than 5%, and therefore our model is considered well-calibrated. There are many other methods to evaluate model calibration during classification tasks, such as the calibration approach mentioned in ref. 24.

Model calibration ensures that the predicted class distribution is similar to the actual class distribution in the dataset. For our problem here, it means that the model prediction rate for stable materials is similar to what is found in the dataset. As shown in Table 3, the difference between the model prediction and true distributions is only around ~4%, which means that our model predictions closely follow the true class distribution. Model calibration is especially useful when synthetic samples are added to the training set during model building and also sometimes when a model puts different weighting on different classes.

Evaluation of the model at different confidence levels

One of the important features of ML is to understand and quantify the expected capability and variance in the performance of our ML models on unseen data. ML models usually achieve this by computing an uncertainty (confidence) measure in their predictions. Using this confidence measure, we assessed the effectiveness of our RF model at different confidence levels. We measured the confidence according to the procedure in the Supplementary Methods section of the Supplementary Information. We found that the performance of the model improved as its operation was restricted to increased confidence levels from 0.50 to 0.65. Using the model in the regime of 0.65 or higher confidence level, its average recall increased to 0.71, average precision increased to 0.70 and the average f1-score increased to 0.70 for the unstable class. Even in this regime, the model covered around 65% of data points for the model. Supplementary Table 2 summarises the performance of the model across fivefolds at different threshold values.

Feature importance

Some of the feature categories were more important than others for predicting the stability of the material. During each iteration, the RF model was trained on the training fold and the feature importance score was calculated. Based on the feature importance score, the top 30 features were identified. A new RF model (with the same hyperparameters as the original RF model) was then fitted using these selected 30 features, and using the same training data as previously used. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, the average classification scores for both models (the first using all 1145 features and the other using only the selected 30 features) were similar, suggested that the top 30 features carry almost all of the predictive information. Further analysis of the top 30 important features for each fold, shown in Fig. 3, indicates that the BACD and ROSA features were the most significant features, followed by the SG features. Some of the features, such as std_average_anionic_radius and metals_fraction were present in all the fivefolds and therefore were considered significant in predicting the stability of the material. The importance of certain descriptors across the fivefolds can be seen by displaying the top features based on the number of occurrences across the fivefolds, and by averaging the feature score of each of the 30 elements across the fivefolds (Fig. 3).

Thus, the classification model has demonstrated its ability to detect a fine material property and vibrational stability, with reasonable accuracy. Apart from being able to detect unstable materials from within the plethora of hypothetical materials very efficiently, detecting the onset of imaginary frequencies is of importance to several other applications in material science. For example, it can be applied for determining the ideal strength of a material, which is the amount of strain at which the material undergoes phase transformation25,26,27,28. With a carefully designed training set of molecular structures, finding molecules with imaginary frequencies from many possible configurations can assist in the discovery of transition states of reactions29,30. Detecting crystal instabilities can also assist in determining polar materials that are likely to be ferroelectric31.

Model limitations

The present ML training was based on sampling materials based on the size of the lattice. While our samples spanned a large diversity of materials, the limitation on lattice size has resulted in restricting the statistical distribution of our dataset within ranges that are different from the statistical distributions of the larger set of materials in MaterialsProject. Given that ML models are derived from data, their predictive performance is dependent on the distribution of the data used for training. Therefore, using the trained ML models to extrapolate the vibrational stability of arbitrary materials might not yield accurate results. To improve the accuracy of the model for extrapolation, the training set must be expanded to include a material with larger numbers of atoms in their unit cells. The approach described in this work provides a framework for achieving this goal.

To sum up, we established a machine learning workflow for building classification models that can predict the vibrational stability of a material. Given that the proportion of unstable materials is always much smaller than the number of stable materials, our workflow involved the application of statistical methods for balancing the dataset. Using random forest classifiers that were trained on several material features, including rapid one-shot ab initio descriptors and basic atom-based and crystal descriptors, the accuracy of determining whether a material is stable was demonstrated to be reasonable. The accuracy was further improved when the model performance was evaluated at different confidence levels. The models trained in this work are, therefore, able to discern the fine feature of phonon instability in crystal systems and can therefore be utilised as a filter in online material databases to assist in the high-throughput screening of synthesizable materials.

Methods

Featurization is the process of transforming data into numerical values (vectors or tensors) that distinguishes between different materials. These numerical values can be referred to as features, descriptors, or fingerprints. The choice of features/descriptors has a major impact on the model performance and generalisability. The most challenging aspect of applying ML to inorganic crystal databases is the development of a descriptor vector that can uniquely describe each material and can be rapidly calculated. In this work, we utilise the following features: symmetry functions (G)32, basic atomic properties descriptors (BACD), and rapid one-shot ab initio descriptors (ROSA). These features were introduced in ref. 33 and were demonstrated to accurately predict a range of material properties. These descriptors are provided in Supplementary Table 1 of the Supplementary Information.

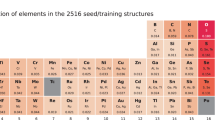

Given that the ML method must be driven by a carefully curated dataset, and that the present dataset of ref. 18 is restricted to semiconducting materials in which only 15% are vibrationally unstable, a key task of the current work is to create a larger set of materials for training the ML models. Therefore, we constructed a dataset of all materials in MaterialsProject that have 4 atoms or less in the unit cell. For the 4-atom unit cells, we restricted our dataset to materials with a bandgap >0.5 eV. We call this dataset the MPStability dataset. The MPStability dataset in this work includes 3112 materials, among which are metals, semiconductors, and insulators. For all materials with a single atom in the unit cell, we perform the subsequent vibrational calculations for the 3 × 3 × 3 supercells, and for materials with more than one atom in the unit cell, we use 2 × 2 × 2 supercells.

We calculated the vibrational stability for these materials by using the finite difference method. The displacement structures for each material were generated using the phonopy code34, and then we calculated the atomic forces for each displacement structure using DFT, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)35. The plane wave pseudopotential approach was adopted with a cut-off energy of 520 eV. The generalised gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)36 functional was used, and the PAW pseudopotentials, as supplied by VASP, were implemented. A 10 × 10 × 10 mesh was used to perform k-point sampling under the Monkhorst-Pack scheme37. The electronic self-consistent calculation was performed with an energy tolerance of 10−5 eV.

The force matrix for each material was then calculated using the phonopy code, after which the vibrational density of states (VDOS) was calculated in a q-mesh of size 8 × 8 × 8. The vibrational instability of a material is determined by the presence of a significant density of imaginary phonons in the VDOS. The python implementation of this procedure is provided in the Github link.

The finite difference method compares well with the DFPT method, as was reported in ref. 22. For our dataset, we confirmed that this is the case by comparing our calculated VDOS with those calculated by ref. 18. For the materials that are common in both datasets (248 materials), there is only a ~4% discrepancy in the identification of stable/unstable materials. We have provided the comparative VDOS plots for these materials in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The materials were classified into stable/unstable classes by training ML classifier models. The dataset consists of 3112 data points (982 unstable and 2130 stable) and 1147 features. The target property (vibrational stability) is labelled by values 1 (stable) and 0 (unstable). The features of the materials were divided into:

-

ROSA features: 218

-

Symmetry functions: 600

-

SG Features: 230

-

Atomic Features: 97

For each material, the ROSA features are obtained by performing a single step of the DFT electronic structure optimisation loop (the self-consistent field iteration) and then extracting the resulting eigenvalues of the electronic Hamiltonian and the total energies. For more details, please refer to ref. 33. The symmetry functions are translationally-invariant features based on the structure’s geometry. Symmetry group (SG) features are generated by hot-coding the symmetry group of the material into 230 columns. The atomic features are composed of descriptive statistics of the properties of the elements within the material.

We used random forest (RF) and gradient boosting (GB) classifiers for this classification task. The RF model performed slightly better than the GB model and therefore was used for further ML tasks. The classification model was trained using fivefold stratified cross-validation, in which the dataset was divided into five stratified splits during each iteration and four splits were used to train the model while the fifth split is used to test the model. To improve the model performance for the unstable class, we systematically introduced ’synthetic data’ in the training set to increase the number of unstable materials, using the following two approaches:

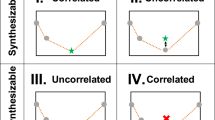

Synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE)

SMOTE38 is one of the most widely used approaches to balancing data. It operates by choosing a random example from the minority class and then finds k (typically k = 5) nearest neighbours (based on a distance measure e.g. Euclidean distance) for that example (Fig. 4a). A randomly selected neighbour is chosen from the k nearest neighbours and a synthetic example is created at a randomly selected point between the two points in feature space. This approach is effective because new synthetic examples from the minority class are created that are plausible, i.e. that are relatively close in feature space to existing examples from the minority class.

Mixup technique

The second approach, which is a more recent method and is becoming more widely used in the ML community, is called the mixup technique39. In this method, data points from each of the stable and unstable classes are randomly chosen from a subset of the generated samples (Fig. 4b). The features of the stable data point are multiplied by a parameter, λ, while the features of the unstable data point are multiplied by (1 – λ). Since our goal is to synthesise additional data for the minority (unstable) class, we should use a small value of λ. Any value of lambda below 0.5 may be possible, but to ensure realistic unstable materials, and a smaller value would be preferred. Hence, we restricted the range of lambda between 0 and 0.2. Subsequently, both features were added together. The purpose of this step is that the new hybrid data point would be closer to the unstable class. Since this new data point is a hybrid of both classes, it is not hard-labelled as unstable. To generate the label for this new hybrid data point, the VDOS data was used. Similarly to feature generation, the energy values of the randomly selected stable and unstable data points were linearly combined with λ and (1 – λ) weights. If the combined energy graph had a negative energy peak, the label for the hybrid data point was assigned as ’unstable’ otherwise it was set to ’stable’.

Data availability

The trained random forest model and the calculated vibrational stability of the materials in the dataset are available in our Github repository: https://github.com/sheriftawfikabbas/crystalfeatures/tree/master/vibrational_stability.

Code availability

The python code to generate the descriptors used in this work is available in our Github repository: https://github.com/sheriftawfikabbas/crystalfeatures.

References

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Curtarolo, S. et al. AFLOWLIB.ORG: a distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 58, 227–235 (2012).

Kirklin, S. et al. The open quantum materials database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. NPJ Comput Mater. 1, 15010 (2015).

Haastrup, S. et al. The computational 2D materials database: high-throughput modeling and discovery of atomically thin crystals. 2d Mater. 5, 042002 (2018).

Zhou, J., Huang, B., Yan, Z. & Bünzli, J.-C. G. Emerging role of machine learning in light-matter interaction. Light Sci. Appl 8, 84 (2019).

Hook, A. L., Alexander, M. R. & Winkler, D. A. in Clemens A. Van Blitterswijk, Jan De Boer (eds.) Tissue Engineering Ch. 8 (Elsevier, 2014).

Mikulskis, P., Alexander, M. R. & Winkler, D. A. Toward interpretable machine learning models for materials discovery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 1, 1900045 (2019).

Epa, V. C. et al. Modelling human embryoid body cell adhesion to a combinatorial library of polymer surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 20902–20906 (2012).

Isayev, O. et al. Materials cartography: representing and mining materials space using structural and electronic fingerprints. Chem. Mater. 27, 735–743 (2015).

Tabor, D. P. et al. Accelerating the discovery of materials for clean energy in the era of smart automation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 5–20 (2018).

Thornton, A. W. et al. Materials genome in action: identifying the performance limits of physical hydrogen storage. Chem. Mater. 29, 2844–2854 (2017).

Xue, D. et al. Accelerated search for materials with targeted properties by adaptive design. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 (2016).

Legrain, F. et al. Vibrational properties of metastable polymorph structures by machine learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model 58, 2460–2466 (2018).

Aykol, M., Dwaraknath, S. S., Sun, W. & Persson, K. A. Thermodynamic limit for synthesis of metastable inorganic materials. Sci. Adv. 4, 1–8 (2018).

Sun, W. et al. The thermodynamic scale of inorganic crystalline metastability. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600225 (2016).

Aykol, M. et al. Network analysis of synthesizable materials discovery. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Malyi, O. I., Sopiha, K. V. & Persson, C. Energy, phonon, and dynamic Stability criteria of two-dimensional materials. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 11, 24876–24884 (2019).

Petretto, G. et al. High-throughput density-functional perturbation theory phonons for inorganic materials. Sci. Data 5, 1–12 (2018).

Manti, S., Svendsen, M. K., Knøsgaard, N. R., Lyngby, P. M. & Thygesen, K. S. Predicting and machine learning structural instabilities in 2D materials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.08091 (2022).

Legrain, F., Carrete, J., van Roekeghem, A., Curtarolo, S. & Mingo, N. How chemical composition alone can predict vibrational free energies and entropies of solids. Chem. Mater. 29, 6220–6227 (2017).

Tawfik, S. A., Isayev, O., Spencer, M. J. S. & Winkler, D. A. Predicting thermal properties of crystals using machine learning. Adv. Theory Simul. 3, 1900208 (2020).

Choudhary, K. et al. High-throughput density functional perturbation theory and machine learning predictions of infrared, piezoelectric, and dielectric responses. NPJ Comput. Mater. 6, 64 (2020).

Choudhary, K. et al. The joint automated repository for various integrated simulations (JARVIS) for data-driven materials design. NPJ Comput. Mater. 6, 173 (2020).

Vaicenavicius, J. et al. Evaluating model calibration in classification. In 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 3459–3467 (PMLR, 2019).

Clatterbuck, D. M., Krenn, C. R., Cohen, M. L. & Morris, J. W. Phonon instabilities and the ideal strength of aluminum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 135501 (2003).

Yang, C. et al. Phonon instability and ideal strength of silicene under tension. Comput. Mater. Sci. 95, 420–428 (2014).

Isaacs, E. B. & Marianetti, C. A. Ideal strength and phonon instability of strained monolayer materials. Phys. Rev. B 89, 184111 (2014).

Li, T. Ideal strength and phonon instability in single-layer MoS. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235407 (2012).

Garrett, B. C. & Truhlar, D. G. Generalized transition state theory. Bond energy-bond order method for canonical variational calculations with application to hydrogen atom transfer reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 4534–4548 (1979).

Bruice, T. C. & Lightstone, F. C. Ground state and transition state contributions to the rates of intramolecular and enzymatic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res 32, 127–136 (1999).

Garrity, K. F. High-throughput first-principles search for new ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 97, 024115 (2018).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 1–4 (2007).

Tawfik, S. A. & Russo, S. P. Naturally-meaningful and efficient descriptors: machine learning of material properties based on robust one-shot ab initio descriptors. J. Cheminform 14, 78 (2022).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Zhang, H., Cisse, M., Dauphin, Y. N. & Lopez-Paz, D. mixup: beyond empirical risk minimization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.09412 (2017).

Acknowledgements

S.A.T. recognises the support of the Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from Deakin University. This work was supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council (ARC) under the Centre of Excellence scheme (project number CE170100026). This work was supported by computational resources provided by the Australian Government through the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI) National Facility and the Pawsey Supercomputer Centre, under the NCMAS scheme. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility located at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A.T. conceived the project and performed the ab initio calculations. M.R. and S.G. performed the machine learning work. S.V. and T.R.W. provided resources and project oversight and supervision. S.P.R. provided resources and assisted in the conceptualisation. S.A.T., M.R., S.G., S.V., and T.R.W. wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript and the Supplementary Information.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tawfik, S.A., Rashid, M., Gupta, S. et al. Machine learning-based discovery of vibrationally stable materials. npj Comput Mater 9, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00943-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00943-z