Abstract

Perovskite-type lead-free piezoelectric ceramics allow access to illustrious piezoelectric coefficients (d33) through intricate composition design and experimental modulation. Developing a swift and accurate technology for identifying (K, Na)NbO3 (KNN)-based ceramic compositions with high d33 in exceedingly large “compositional” space will establish an innovative research paradigm surpassing the traditional empirical trial-and-error method. Herein, we demonstrate an interpretable machine learning (ML) framework for quick evaluation of KNN-based ceramics with high d33 based on data from published literature. Specifically, a thorough feature construction was carried out from the global and local dimensions to establish tree regression models with d33 as the target property. Subsequently, the feature-property mapping rules of KNN-based piezoelectric ceramics are further optimized through feature screening. To intuitively understand the correlation mechanisms between ML regression targets and features, the sure independence screening and sparsifying operator (SISSO) method was employed to extract the essential descriptors to explain d33. A straightforward descriptor, \({\text{e}}^{({{NM}}_{\text{B}}-{{MV}}_{\text{B}})}\cdot {ST}/{(I{D}_{\text{A}})}^{2}\), consisting of only four easily accessible parameters, can accelerate the evaluation of a series of novel KNN-based ceramics with high d33 while exhibiting strong theoretical interpretability. This work not only provides a tool for the rapid discovery of high piezoelectric performance in KNN-based ceramics but also offers a data-driven route for the design of property descriptors in perovskites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-performance piezoelectric ceramics are a unique class of functional materials, especially (PbZr1−xTixO3, PZT)-based ceramics, which have been employed extensively in modern electronic devices due to their exceptional piezoelectric coefficients (d33 ≈ 200–1500 pC N−1) and high Curie temperatures (Tc ≈ 90–400 °C)1,2,3,4,5. Exploiting such materials has been a hot spot in the industry-university-research communities for half a century. However, the social ramifications (e.g., cancer6, fetal malformation7, food safety8, etc.) stemming from lead pollution are progressively intensifying. To pursue sustainable development, regions and countries actively promote the research and development (R&D) of lead-free piezoelectric ceramics, and moreover, corresponding legislation and regulations have been enacted or enhanced9,10,11,12,13 (e.g., European exemption for lead-based ceramic products will gradually expire between 2024 and 2026)14. The urgency of R&D on lead-free piezoelectric ceramics is evident. Among numerous lead-free piezoelectric ceramics, potassium sodium niobate [(K, Na)NbO3, KNN]-based ceramics have emerged as one of the most promising alternatives because of their large d33 and good temperature stability15,16. After decades of effort, composition design based on phase boundary engineering has established a robust foundation for optimizing the d33 of KNN-based ceramics. For example, a new KNN-based ceramic with d33 ≈ 550 pC N−1 was obtained by optimizing element content to design new phase boundaries consisting of rhombohedral and tetragonal (R-T) phases15. Tao et al.16 used the nanoscale multiphase coexistence to construct a slush polar state and displayed novel relaxor behavior with frequency dispersion occurring at the phase transition point between different ferroelectric phases, achieving an ultrahigh piezoelectric response (d33 ≈ 650 ± 20 pC N−1). The objective fact is that, due to variable chemical compositions and processing conditions, KNN-based ceramics with high piezoelectric performance usually exist in a vast and complicated combinatorial space. The previous empirical trial-and-error research methodology still exhibits limitations in terms of time consumption and inefficiency, which causes the R&D speed of KNN lead-free ceramics to plummet. Therefore, developing a rapid and convenient technique for evaluating the d33 of KNN-based ceramics with convoluted compositions and process conditions will be crucial to accelerate the discovery of new materials.

Recently, advancements in artificial intelligence and material informatics have achieved remarkable outcomes. Machine learning (ML) is an extraordinary technique for mining the connections between material structures/composition data and performances that makes it possible to accelerate material design. This methodology has been employed to target research on piezoelectric17,18,19,20, crystal structure21, ferroelectric22,23, and inorganic perovskite stability24,25. For instance, based on ML models and graph neural networks, Hu et al.17 applied composition/crystal structure features to predict the piezoelectric modulus of inorganic materials. They predicted the piezoelectric modulus of 12680 materials and reported the top 20 potential high-performance piezoelectric materials (NaNbO3 has the top predicted value of 2.448 C m−2). Yuan and his colleagues compared four feature engineering strategies (i.e., principal component analysis, feature importance ranking based on Gradient Boosting Tree, domain knowledge and elemental compositions) within a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to accelerate material exploration toward large d33 in BaTiO3-based ceramics18. Then, they integrated prediction results and experiments for loop iterative optimization, and the ceramic with the best composition displaying a d33 of ~ 430 pC N−1 was synthesized in the second iteration. Immediately afterward, He et al.20 coupled several feature screen techniques (i.e., Pearson correlation coefficient screening, feature exhaustion and domain knowledge) in seeking the key features describing the d33 of BT-based ceramics. Ultimately, the predicted value (633 ± 70 pC N−1) of the optimal composition ceramic (Ba0.95Ca0.05)(Ti0.9Sn0.1)O3 searched by the SVR model was very close to the experimental value (605 ± 14 pC N−1). Even though using diverse feature engineering techniques to maximize the fitting accuracy of the regression model has proven especially successful in finding compounds with desired properties, the black box effect of ML techniques is criticized frequently in the field of material science for not providing favorable physical insights, which makes the predicted results difficult to trust. Consequently, it is necessary to enhance intuitive interpretability by discussing the connection mechanism between ML models and features. Building upon this foundation, the newly developed sure independence screening and sparsifying operator (SISSO)26 is a potent interpretable ML algorithm. It constructs a very complex feature space via a combination of algebraic and functional operations and then derives a visual mathematical formula or descriptor linearly related to the target variable. SISSO has been applied in diversified investigations, such as identifying the stability of perovskites24 and explaining A-site-driven polarization in binary potassium niobate materials27.

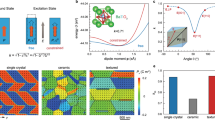

Inspired by the above research, the present work constructs a d33 descriptor development framework integrating feature engineering, ML regression and interpretability technology, intending to reveal the d33 mapping rules of KNN-based ceramics in a broad compositional space, as shown in Fig. 1. We perform comprehensive feature construction for 1113 KNN-based ceramic experimental compositions, incorporating traditional ML regression and an embedded SISSO method to establish a simple d33 descriptor formula. It clarifies how to modulate the compositions of KNN-based ceramics to obtain higher d33 values efficiently. In addition, we build a link between this descriptor and phase boundary theory in KNN-based ceramics, which rationally explains the high d33 caused by multiphase coexistence and is well verified in peer newly synthesized ceramics. This work mines thousands of previously synthesized compositions and structures, not only developing a visual prediction model for the d33 of KNN-based ceramics but also facilitating the search for high-performance inorganic piezoelectric materials from a wider perspective.

The process consists of three primary steps. a Feature construction layer: design two distinct types of feature sets to describe d33 from a global and local perspective based on the typical ABO3-type perovskite crystal structure of KNN-based ceramics, namely XA/B, XA*B and XA, XB. b Feature screening layer: combining feature engineering (PPC screen, feature importance ranking based on the ML model and feature exhaustion) and ML models to optimize the predicting accuracy of d33 while screening the optimal feature set. c SISSO layer: the optimal feature set based on the ML model generates large amounts of complex descriptors through mathematical operations and then executes SIS to sort and reduce the dimensionality of the descriptors while searching for the simplest descriptor.

Results and discussion

Feature construction

KNN-based ceramics have a complex nonlinear relationship between compositions, process parameters and piezoelectric coefficients. Whether the material information covered in the dataset is comprehensive is critical to the accuracy of the ML model. The original data are 1113 KNN-based piezoelectric ceramic samples from 244 published studies, and the information includes chemical composition, sintering temperature and d33 values. All of the gathered samples are prepared using the traditional solid-state reaction method to ensure data comparability and prevent the impact of various process methods on the ML models. Additionally, alkali metals are prone to volatilization under high-temperature sintering conditions, but it is worth noting that the sintering temperature in the dataset is predominantly centered at approximately 1100 °C. We postulate that the volatilization degrees of K and Na metal exhibit a close resemblance and uniformly employ nominal compositions in the literature as the actual compositions.

Considering the large number of latent composition combinations of KNN-based ceramics but the small amount of existing experimental data (1113 samples), the challenge is how to describe material information comprehensively. Therefore, we design two distinct types of feature sets based on the typical ABO3-type perovskite crystal structure of KNN-based ceramics, namely, A-site, B-site combination and A-site, B-site separation (Fig. 1), to account for the mapping relationships between d33 and material compositions from a global and local perspective. The first type of A-site and B-site combination feature construction follows Eqs. (1) and (2):

where \({f}_{i}\) is the mole fraction of the element in the chemical composition and \({X}_{i}\) corresponds to the property of an element, including electron affinity, Pauling electronegativity, atomic radius, and many other features, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Through Eqs. (1) and (2), we combine the elemental properties in Supplementary Table 1 to obtain 62 features, denoted as feature set Φ1. For simplicity, \({X}_{{\rm{A}}/{\rm{B}}}\) is abbreviated as lowercase x, and \({X}_{{\rm{A}}* {\rm{B}}}\) is abbreviated as uppercase X by removing the subscript. The second type of A-site and B-site separation feature construction directly uses \({X}_{{\rm{A}}}\) and \({X}_{{\rm{B}}}\) as features, denoted as Φ2. The tolerance factor (t) and the octahedral factor (μ) describe the stability of perovskites, and the sintering temperature (ST) reflects the parameter in the preparation process of KNN-based ceramics. They are both added to Φ1 and Φ2. Finally, each feature set contains 65 initial features (the dataset details are shown in Supplementary Dataset 1).

Machine learning regression for d 33 and feature screening

In ML models, an excessive number of features can cause dimensional catastrophes in the feature space, which increases computational overhead and induces model overfitting. The number of features was only in single digits in previous studies on perovskite materials19,20,22,28,29. Therefore, we establish ML regression models with d33 as the target property based on the constructed feature sets Φ1 and Φ2 while screening the feature using the smallest cross-validation error as the criterion, involving two steps of Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) screening and the feature exhaustion method (Feature exhaustion refers to traversing all feature subsets in a feature set for ML model training to find the optimal subset).

The previously constructed features are grouped according to |PCC | ≥ 0.85 to determine that the features in each group are highly correlated (the PCC results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), and the grouping situation is displayed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Taking Φ1 as an example, there are seven feature groups in total. Besides, only ten features such as ST, t, division and multiplication of the ratio of valence electrons to nuclear charges of A-site and B-site elements (ven/nc, VEN/NC), the ratio of nuclear electron distance between A-site and the B-site elements (dce), the ratio of first ionization energy of A-site and B-site elements (ei), the ratio of nuclear magnetic moments of A-site and B-site elements (nm), the ratio of pseudopotential core radii between A-site and B-site elements (pcr), the ratio of polarizability of A-site and B-site elements (p) and the ratio of cell parameters in the c direction of A-site and B-site elements (c-c) have low correlation with other features. To filter out the features with the least fitting error in each group, we train three ML models including Extra Tree Regression (ETR), Random Forest Regression (RFR) and Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) individually using each feature, retaining the top three features with the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) in each group. Then, we extract one of the top three features in each group for feature combination. Each ML model traversed 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 2 × 2 = 972 combinations (i.e., seven feature groups in Supplementary Table 2) and retained the feature combination with the lowest RMSE. Eventually, the number of Φ1 features is reduced to 17, comprising ten low correlation features and one feature retained from each of the seven groups (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, the number of Φ2 features is reduced to 11, comprising five low correlation features and one feature retained from each of the six groups (Supplementary Table 3).

To further refine the combination of features that affect d33, feature exhaustion is performed based on the ETR, RFR, and GBR algorithms. Specifically, the training results of all feature subsets in the feature set retained in Φ1 and Φ2 are traversed. The 10-Fold Cross-Validation error (10-CVerror) is used as the evaluation criterion, and the CVerror is calculated as follows:

where k is Cross-Validation folds, equals the number of samples corresponding to Leave-One-Out CV (LOOCV), and RMSE is the root mean square error. The 17 features preserved in Φ1 have a total of \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{17}{\text{C}}_{17}^{i}=131071\) subsets, which requires a significant amount of computing resources. The 11 features preserved in Φ2 only have a total of \(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{11}{\text{C}}_{11}^{i}=2047\) subsets. For this reason, we utilize the Mean Decrease Impurity (MDI) and Permutation Importance (PI) methods embedded within the ML model to rank the importance of the 17 features retained in Φ1. As seen in Supplementary Fig. 3, the ranking results of MDI and PI are almost identical, and we extract the top 11 important features (i.e., red box in each figure) to match the number of features preserved in Φ2. The results of feature exhaustion are shown in Fig. 2a–f, in which the 10-CVerror stabilizes when reaching 6 or 7-tuple features (i.e., red oval mark). Among them, the ETR model trained with the optimal 7-tuple feature combination (denote as Φ3, as shown in Table 1) exhibits the lowest LOOCVerror of ±49 pC N−1 (Fig. 2g). As shown in Table 2, Yuan et al.18 and He et al.20 chose the SVR algorithm to establish an ML model for the d33 values of BT-based ceramics. SVR effectively leverages all available sample information in the context of a small dataset and is able to equilibrate prediction performance and computational efficiency. However, when utilizing a limited number of training samples to forecast the compositions of vast unsynthesized space in material optimization problems, the prediction results readily converge toward local optima, which makes inadequate fitting of sparse samples. As reported in Yuan et al., six data points with d33 values exceeding 400 pC N−1 have large deviations in the predicted values. In this study, 1113 composition samples are gathered to describe the property-structure relationship more comprehensively. The data distribution span of d33 in the original dataset is broader (0 ~ 700 pC N−1, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4) and has an ideal normal distribution. In addition, for a given dataset of K data samples, the training cost generally grows proportionally to K2 for a support vector machine30 and K*log (K) for a regression tree31 (Here, K ≈ 1000, the training cost of the SVR is three orders of magnitude greater than that of the ETR). At this time, ETR offers substantial advantages over SVR because it possesses parallel capability for constructing massive decision trees and exhibits high robustness against noise and outliers in large-scale data. Hence, the LOOCVerror of ±49 pC N−1 is further reduced compared to analogous studies (Table 2).

a–f Feature exhaustion on three ML models (ETR, RFR, and GBR) of 11 retained features based on two types of feature construction. g Model leave-one-out cross-validation results corresponding to the optimal feature set. h, i The performance of the ETR model on the training and test data using the best 7-tuple and 6-tuple feature sets.

To evaluate the predictive ability of the regression model, we use 80% of the data samples for training and 20% for prediction. The predicted d33 by the ETR model with the optimal 7-tuple and 6-tuple features is shown in Fig. 2h, i. The blue dots represent the training set, and the red dots represent the test set, both of which are evenly distributed around the diagonal, indicating that the ETR model has reasonable performance.

SISSO method for d 33

Since the chemical composition and process parameters are major factors determining the d33 of KNN-based ceramics, a useful phenomenological model may evaluate and quantify those factors, further facilitating the search for new compositions with high d33. To create a predictive model that embeds important feature information while maintaining sufficient interpretability for analysis and understanding, we combine the SISSO method with the ML feature screening results from the previous subsection to find the best mathematical descriptor for d33. The features in Φ3 are used as the input features of the SISSO algorithm. Starting from these seven features, the algorithm generated a feature set with 2, 246, 891, 011 candidate features (details provided in the methods). Then, SIS is performed among the high-dimensional candidate features to retain the top 1000 1D features [i.e., SISSO Feature Space (SISSOFS), as listed in Supplementary Dataset 2] that have the highest correlation with d33 values. The ML regression + SIS process in this work can be regarded as a variant of the developed SISSO method. It should be underlined that after adding ML regression while discarding SO, the generated mathematical descriptor for d33 is derived based on the SIS results, not directly output by the SO program.

It can be seen from the SISSOFS that the correlation values between all the features and d33 are between 0.5–0.55, and there is a certain quantitative relationship between them. Through careful observation and statistics, a total of 307 descriptors containing (NMB − MVB) can be found, of which 99 descriptors contain (exp(NMB − MVB)). Subsequently, four simpler descriptors are screened from the SISSOFS according to their complexity:

The subscript represents the relevant ranking in the SISSOFS. Their corresponding distributions with d33 are shown in Fig. 3, exhibiting similar regularities of data distribution. In Fig. 3, 50 samples (red dots) are selected randomly from the 1113 original data samples as the verification set. Among them, 80% are used as the training set (blue dots), while the remaining 20% are designated as the testing set (yellow dots), all of which have consistent variation trends. Due to the omission of the ST in the descriptor, the model fails to recognize samples with the same composition but different ST (Fig. 3a). This leads to longitudinal stacking observed in the mapping points between \({D}_{747}^{1}\) and d33 (i.e., red box). After introducing ST, the data stacking phenomenon disappears, and the distribution becomes more compact (Fig. 3b). Compared with \({D}_{120}^{2}\), \({D}_{258}^{3}\) can reduce one mathematical operation (Fig. 3c) to further eliminate the redundant item MVB. Finally, a simplified d33 descriptor \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) can be obtained (Fig. 3d), which

The blue dots are the training set, the yellow dots are the test set and the red dots are the validation set. a Correspondence plot of the 747th ranked descriptor in the SISSOFS with d33 of each sample, the correlation coefficient (\({D}_{747}^{1}\), d33) = −0.5029. b The descriptor \({D}_{120}^{2}\) ranked 120, and the correlation coefficient (\({D}_{120}^{2}\), d33) = −0.5124. c The descriptor \({D}_{258}^{3}\) ranked 258, and the correlation coefficient (\({D}_{258}^{3}\), d33) = −0.5089. d The description \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) obtained by simplifying (a–c), correlation coefficient (\({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\), d33) = −0.5222.

While maintaining a good data distribution, the linear relationship between the three datasets becomes more pronounced than before.

Extracting physical insights from descriptors

SISSO is an ideal ML method to derive physically intuitive descriptors26. It can be detected from Eq. (9) that the d33 and \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) values show a noticeable inverse trend. To extract the physical insights from \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\), we analyze each parameter in Eq. (9). The mapping relationship between the appointed parameter and \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\), along with the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis, is shown in Fig. 4. A larger NMB value can promote lower d33 values, while higher d33 is more likely to occur around NMB ≈ 5.8 (Fig. 4a). This conclusion is consistent with the SHAP values computed based on the ETR model, where NMB ≈ 5.8 exhibits the strongest positive gain on d33 (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the increasing trend of MVB values is aligned with d33, and the highest SHAP value is observed around MVB ≈ 11.2 (Fig. 4d). Here, NMB is one of the important physical quantities that measures the strength of interaction between nucleons and extranuclear electrons on the B-site. And NMB is highly positively correlated with the electron affinity of B-site elements (EAB) (i.e., PCC(NMB, EAB) = 0.79). Meanwhile, MVB is highly positively correlated with cell parameters of B-site elements in the c direction (CB-c) (i.e., PCC(MVB, CB-c) = 0.98), and their relationships of data distribution are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. Based on the first-principles calculations of KNbO3 by ref. 32, as the c-axis increases, a significant portion of polarization and d33 are contributed by the ferroelectrically active B-site Nb. This is attributed to the strong hybridization of Nb 4d orbitals with O 2p orbitals, as well as the fact that the piezoelectric response of K is highly suppressed by the ionic interaction between K and O. The conclusion of KNbO3 is also available for the KNN system, so the high PCC value between MVB and CB-c (Supplementary Fig. 5b) in KNN-based ceramics justifies the positive gain of MVB on d33. Furthermore, the increase in molar volume generally leads to an increment in the average distance between electrons and atomic nuclei, weakening the interaction force between them and thereby reducing the electron affinity (i.e., MVB goes up and EAB goes down). This establishes the association between NMB and MVB, and the negative gain of NMB on d33 can be explained by CB-c.

Figure 4e, f shows that a smaller IDA value does not favor the attainment of high d33 in KNN-based ceramics, but IDA of approximately 0.065 has a noticeable enhancement trend for d33. It is well known that ionic displacement can cause changes in the electronic structure of crystals with intermediate chemical bonds that can favor ferroelectric phase transitions33. For example, previous studies have demonstrated that KNN ceramics possess higher piezoelectric coefficients and spontaneous polarization than KNbO3 at room temperature34, ascribed to the relatively larger ion displacement from the smaller radius of Na at the A-site (ionic radius of 1.24 Å with a coordination number of 12). Furthermore, Na causes an increased moving space for both themselves and adjacent O, thereby amplifying the ion displacement response under strain conditions34. According to the displacement-type phase transition theory of perovskite ferroelectrics, their electric polarization primarily arises from ionic displacement35. When the temperature is below Tc, the ions undergo displacement to deviate from their central positions, leading to the separation of positive and negative charge centers and the formation of electric dipoles within the unit cell. Therefore, a change occurs in the KNN-based lattice structure. The formation of polarization causes lattice distortion, accompanied by lattice stretching along the polarization direction and relative lattice compression along other directions, ultimately leading to the occurrence of a ferroelectric phase transition. Moreover, it is widely recognized that dense KNN-based ceramics need to be sintered at high temperature, but the optimal sintering temperature fluctuates approximately 1100 °C due to the difference in chemical compositions and the evaporation of alkali metal elements. The extensive samples reveal that the sintering temperature of ~1075 °C significantly contributes to achieving a high d33 value (Fig. 4h).

In essence, taking advantage of a small set of selected representative features based on domain knowledge or scientific strategies, SISSO can offer a direct and brutal approach for improving linear relationships among data and establishing physical descriptors. In the broad KNN-based ceramic composition space, selecting chemical compositions with small NMB, large MVB and IDA can facilitate the design of high d33 values. These chemical parameters are easily obtainable, and using this descriptor (\({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\)) allows for the evaluation of piezoelectric coefficients of ceramics prior to experimentation.

Phase boundary theory in descriptors

It is abundantly clear that pure KNN ceramics undergo a series of structural phase transitions as the temperature increases: TR-O of ~ −123 °C (rhombohedral-orthorhombic) → TO-T of ~ 210 °C (orthorhombic-tetragonal) → Tc of ~ 410 °C (cubic)36,37. Previous research has revealed that when KNN is in a state of multiphase coexistence, the spontaneous polarization orientations of the ferroelectric domains are diversified, and their orientations are consistent during the polarization process. It is easier to obtain high piezoelectric performance at this time compared to the single-phase structure38,39.

Here, we endeavor to establish a connection between the SISSO descriptors (\({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\)) and phase boundary theory of KNN-based ceramics, aiming to further elucidate the mapping relationship between the \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) and d33 values. The corresponding situations between 588 multiphase coexistence of KNN-based ceramic data samples from the original dataset with two-phase or multiphase coexistence and \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) values are illustrated in Fig. 5. The descriptor value intervals corresponding to the readily constructed O-T phase boundary (810, 4270) and R-O phase boundary (1270, 3390) are very wide, and most of them are concentrated in the region with a large \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) value (Fig. 5a, b). The difficult-to-achieve R-T phase boundary (724, 2435) and R-O-T (420, 2160) phase boundary corresponding to the \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) value intervals rapidly shrink and shift to the left. As the \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) values decrease and approach the R-T or R-O-T phase boundaries, the d33 values tend to be higher. This finding is consistent with the conclusion of previous research that the R-T or R-O-T phase boundary exhibits a more significant improvement in the piezoelectric performance of KNN-based ceramics15,16,34,40.

The reliability of the descriptor \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) is validated using 63 newly reported compositions41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 with high d33 (i.e., the red star in Fig. 5) that are not present in the training dataset. As depicted in Fig. 5, these compositions with low \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) values demonstrate excellent d33 values, and their phase boundaries fall within the intervals defined by \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\). This further proves that the descriptor \({D}_{\text{simp}}^{4}\) can be utilized for the prediction and evaluation of compositions with high d33 in KNN-based ceramics.

In summary, we propose an ML model-coupling tactic that enables the quick prediction of d33 values in KNN-based ceramics and the assessment of phase boundaries. The ETR model trained with 1113 data samples in this strategy shows outstanding generalization ability, and the LOOCV error is as low as 49 pC N−1. On the other hand, the embedded SISSO model generates a d33 visualization descriptor (i.e., \({\text{e}}^{({{NM}}_{\text{B}}-{{MV}}_{\text{B}})}\cdot {ST}/{(I{D}_{\text{A}})}^{2}\)), which successfully captures the mixed effect of structure - sintering process - piezoelectric coefficient in KNN-based ceramics. More importantly, this descriptor can construct a rational mathematical predictive model within the category of phase boundary theory, allowing the evaluation of d33 values for unsynthesized compositions with just four simple parameters (i.e., NMB, MVB, ST, IDA). In addition, 63 recently reported compositions of KNN-based ceramics with high d33 values are found to fit with the proposed concept, providing proof for the descriptor. We anticipate that this descriptor has the potential to predict a broader range of compositions, accelerating the research of KNN-based ceramics with high piezoelectricity. This work proposes a highly intuitive and instructive avenue for improving the performance of perovskites, overcoming the low trustworthiness and interpretability caused by the black box effect of traditional ML models. We envision that this strategy holds great potential for performance optimization in other materials as well.

Furthermore, there are limitations in the data based on published literature, including interference from different teams, equipment and operators, which restricts the development of AI4S (AI for Science). In the future, automation-standard platforms integrating high-throughput fabrication, characterization and ML will overcome these limitations and tremendously accelerate the R&D of materials.

Methods

Computer packages used

ML algorithms used in the feature screening layer were all derived from the Python package scikit-learn. Model hyperparameters were optimized using a self-setting grid search method. The relevant Python program execution code was uploaded to Git-Hub (https://github.com/BWMa688/BWMa688/tree/jermyn_dev, including Pearson correlation coefficient calculation, feature importance, feature exhaustion, and model verification).

SISSO was performed using Fortran 90, and Ouyang’s homepage (https://github.com/rouyang2017/SISSO) introduces how to use SISSO for details. In this work, using the mathematical operators \({\hat{{\boldsymbol{H}}}}^{({\rm{m}})}\,\)= {+, −, *, /, −1, sqrt, 2, 3, exp, log, cbrt, |−|} in the input features, a huge feature space (more than 1010) was generated after 3 iterations with a complexity cutoff of 7, improving the linear description of the target. SIS scores each feature with a correlation magnitude (absolute value of the inner product between target attribute and feature) and keeps only the top 1000 ranked (i.e., SISSOFS). The hyperparameters setup for SISSO is listed in Table 3.

ML algorithm principles

The Extra Tree Regression (ETR) algorithm was used to construct the optimal ML model in this study. ETR, proposed by Geurts58, is an ensemble learning algorithm based on Decision Trees (DTs). A DT is a hierarchical structure that consists of root, internal and leaf nodes. Each internal node and leaf node correspond to a feature judgment condition and the target value. The ETR algorithm utilizes the entire dataset to integrate multiple DTs while employing a random selection of data features and splitting values at internal nodes. The accuracy and complexity of the model are enhanced through fine-tuning hyperparameters such as n_estimators (number of decision trees) and min_samples_split (the minimum number of samples required to split an internal node). Finally, the prediction result of the sample is determined by taking the mean value of the leaf node.

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a renowned ML algorithm. The principle of SVR is to ascertain an optimal hyperplane in a high- or infinite-dimensional space that minimizes the margin between it and the sample within the deviation range (\(\pm \,\epsilon\), i.e., decision boundary width) while minimizing the number of samples outside this decision boundary59. SVR effectively extracts relevant information from crucial sample points through decision boundaries, thereby demonstrating superior performance when applied to small-scale dataset. Solving the hyperplane in high-dimensional space poses a significant challenge when training a big dataset using the SVR algorithm, which often results in the algorithm converging to a local optimal solution and leading to a degradation in the accuracy of the model.

Data availability

The source data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information of this article. The dataset (1113 sample data and SISSO data) that supports the results of this study can be obtained form Git-Hub link (https://github.com/BWMa688/BWMa688/tree/jermyn_dev), and is detailed in the methods section. All relevant data are available from the authors.

Code availability

The programming code that supports the results of this study is available in the Methods section of this work. All relevant codes are available from the authors.

References

Yasuyoshi, S. et al. Lead-free piezoceramics. Nature 432, 84–87 (2004).

Kosec, M., Malič, B., Benčan, A. & Rojac, T. In Piezoelectric and Acoustic Materials for Transducer applications (eds Safari, A & Akdoğan, E. K) (Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 2008).

Wang, X. et al. Giant piezoelectricity in potassium–sodium niobate lead-free ceramics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2905–2910 (2014).

Li, F. et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectricity in ferroelectric ceramics by design. Nat. Mater. 17, 349–354 (2018).

Zhi, Z. et al. Doping effects of oxides on 0.06BiYbO3-0.94Pb(Zr0.48Ti0. 52)O3 ternary piezoceramics. Guisuanyan Tongbao 41, 1020–1030 (2022).

Absalon, D. & Slesak, B. The effects of changes in cadmium and lead air pollution on cancer incidence in children. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 4420–4428 (2010).

Takatani, T. et al. Individual and mixed metal maternal blood concentrations in relation to birth size: an analysis of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). Environ. Int. 165, 107318 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Hidden risks from potentially toxic metal(loid)s in paddy soils-rice and source apportionment using lead isotopes: a case study from China. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 158883 (2023).

European Commission. Directive 2002/96/EU of the european parliament and of the council of 27 January 2003 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE). Off. J. Eur. Union 46, 24–38 (2003).

European Commission. Directive 2002/95/EU of the european parliament and of the council of 27 January 2003 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment. Off. J. Eur. Union 46, 19–23 (2003).

European Commission. Directive 2011/65/EU of the european parliament and of the council of 8 June 2011 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 54, 88–110 (2011).

Ministry of Information Industry China. Measures for the administration on pollution control of electronic information products. Ministry of Information Industry China Order No. 39, 2006.

Sher, B., Kuehl, S. & Beth-Jackson, H. Electronic waste recycling act of 2003 (SB 20) solid waste: hazardous electronic waste, U.S. California Senate Bill No. 20, 2003.

Baron, Y. et al. Study to assess requests for a renewal of nine (-9-) exemptions 6(a), 6(a)-I, 6(b), 6(b)-I, 6(b)-II, 6(c), 7(a), 7(c)-I and 7(c)-II of Annex III of Directive 2011/65/EU (Pack 22) – Final Report (Amended Version) (eds Engelkamp, H). 16–18 (Oeko-Institut e.v., 2022).

Wu, B. et al. Giant piezoelectricity and high curie temperature in nanostructured alkali niobate lead-free piezoceramics through phase coexistence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15459–15464 (2016).

Tao, H. et al. Ultrahigh performance in fead-free piezoceramics utilizing a relaxor slush polar state with multiphase coexistence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 13987–13994 (2019).

Hu, J. & Song, Y. Piezoelectric modulus prediction using machine learning and graph neural networks. Chem. Phys. Lett. 791, 139359 (2022).

Yuan, R., Xue, D., Xu, Y., Xue, D. & Li, J. Machine learning combined with feature engineering to search for BaTiO3 based ceramics with large piezoelectric constant. J. Alloy. Compd. 908, 164468 (2022).

Yuan, R. et al. Accelerated discovery of large electrostrains in BaTiO3-based piezoelectrics using active learning. Adv. Mater. 30, 1702884 (2018).

He, J. et al. Accelerated discovery of high-performance piezo catalyst in BaTiO3-based ceramics via machine learning. Nano Energy 97, 107218 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Deep learning-based prediction of contact maps and crystal structures of inorganic materials. ACS Omega. 8, 26170–26179 (2023).

He, J. et al. Machine learning identified materials descriptors for ferroelectricity. Acta Mater. 209, 116815 (2021).

Balachandran, P. V., Kowalski, B., Sehirlioglu, A. & Lookman, T. Experimental search for high-temperature ferroelectric perovskites guided by two-step machine learning. Nat. Commun. 9, 1668 (2018).

Bartel, C. J. et al. New tolerance factor to predict the stability of perovskite oxides and halides. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav0693 (2019).

Tao, Q., Xu, P., Li, M. & Lu, W. Machine learning for perovskite materials design and discovery. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 23 (2021).

Ouyang, R., Curtarolo, S., Ahmetcik, E., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. M. SISSO: a compressed-sensing method for identifying the best low-dimensional descriptor in an immensity of offered candidates. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 083802 (2018).

Oh, S.-H. V., Hwang, W., Kim, K., Lee, J.-H. & Soon, A. Using feature-assisted machine learning algorithms to boost polarity in lead-free multicomponent niobate alloys for high-performance ferroelectrics. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104569 (2022).

Yuan, R. et al. Accelerated search for BaTiO3-based ceramics with large energy storage at low fields using machine learning and experimental design. Adv. Sci. 6, 1901395 (2019).

Yuan, R. et al. A knowledge-based descriptor for the compositional dependence of the phase transition in BaTiO3-based ferroelectrics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 44970–44980 (2020).

Antoine, B., Seyda, E., Jason, W. & Leon, B. Fast kernel classifiers with online and active learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 6, 1579–1619 (2005).

Sani, H. M., Lei, C. & Neagu, D. in Artificial Intelligence XXXV. SGAI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (eds Bramer, M. & Petridis, M.) 191–197 (Springer, 2018).

Shi, J., Grinberg, I., Wang, X. & Rappe, A. M. Atomic sublattice decomposition of piezoelectric response in tetragonal PbTiO3, BaTiO3, and KNbO3. Phys. Rev. B 89, 094105 (2014).

Prosandeev, S. A., Turik, A. V. & Bunin, M. A. Disorder due to a strong correlation of ionic displacements. Ferroelectrics 299, 185–189 (2004).

Tan, Z., Peng, Y., An, J., Zhang, Q. & Zhu, J. Intrinsic origin of enhanced piezoelectricity in alkali niobate‐based lead‐free ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 5262–5270 (2019).

Xing, J. et al. Research progress of high piezoelectric activity of potassium sodium niobate based lead-free ceramics. Acta Physica Sinica 69, 127707 (2020).

Wu, J., Xiao, D. & Zhu, J. Potassium–sodium niobate lead-free piezoelectric materials: past, present, and future of phase boundaries. Chem. Rev. 115, 2559–2595 (2015).

Shirane, G., Newnham, R. & Pepinsky, R. Dielectric properties and phase transitions of NaNbO3 and (Na,K)NbO3. Phys. Rev. 96, 581–588 (1954).

Ahart, M. et al. Origin of morphotropic phase boundaries in ferroelectrics. Nature 451, 545–548 (2008).

Fu, H. & Ronald E, C. Polarization rotation mechanism for ultrahigh electromechanical response in single-crystal piezoelectrics. Nature 403, 281–283 (2000).

Xu, K. et al. Superior piezoelectric properties in potassium-sodium niobate lead-free ceramics. Adv. Mater. 28, 8519–8523 (2016).

Cheng, Y. et al. Hardening effect in lead-free KNN-based piezoelectric ceramics with CuO doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 55803–55811 (2022).

Carreño-Jiménez, B., Reyes-Montero, A. & López-Juárez, R. Complete set of ferro/piezoelectric properties of BaZrO3 and (Ba,Ca)ZrO3 doped KNLNS-based electroceramics. Ceram. Int. 48, 21090–21100 (2022).

Wang, F., Zhang, T., Guo, M. & Zhang, M. Room temperature constructing rhombohedral-tetragonal phase boundary in novel (Bi, Na)(Zr, Ti)O3 modified (K, Na)(Nb, Sb)O3 ceramics: Phase structure, defect and piezoelectric performance. Ceram. Int. 48, 19954–19962 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Utilization of nonstoichiometric Nb5+ to optimize comprehensive electrical properties of KNN-based ceramics. Inorg. Chem. 61, 18660–18669 (2022).

Chae, Y.-G. et al. Ultrahigh performance piezoelectric energy harvester using lead-free piezoceramics with large electromechanical coupling factor. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 1–20 (2023).

Huan, Y. et al. Optimizing energy harvesting performance by tailoring ferroelectric/relaxor behavior in KNN-based piezoceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 11, 935–944 (2022).

Deng, D. et al. Potassium sodium niobate-based transparent ceramics with high piezoelectricity and enhanced energy storage density. J. Alloys Compd. 953, 170081 (2023).

Go, S.-H. et al. Excellent piezoelectric properties of (K, Na)(Nb, Sb)O3-CaZrO3-(Bi, Ag)ZrO3 lead-free piezoceramics. J. Alloy. Compd. 889, 161817 (2021).

He, B. et al. Softening effect of trace Fe-substituted potassium-sodium niobate-based lead-free piezoceramics. J. Alloy. Compd. 909, 164718 (2022).

Jia, P. et al. The achieving enhanced piezoelectric performance of KNN-based ceramics: Decisive role of multi-phase coexistence induced by lattice distortion. J. Alloy. Compd. 930, 167416 (2023).

Batra, K., Sinha, N. & Kumar, B. Effect of Nd-doping on 0.95(K0.6Na0.4)NbO3-0.05(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramics: enhanced electrical properties and piezoelectric energy harvesting capability. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 170, 110953 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Meticulously tailoring phase boundary in KNN‐based ceramics to enhance piezoelectricity and temperature stability. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 105, 5213–5221 (2022).

Xi, K. et al. Effect of a lattice distortion strategy on the phase transition and properties in KNN‐based ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 106, 466–475 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Insight into the evolutions of microstructure and performance in bismuth ferrite modified potassium sodium niobate lead-free ceramics. Mater. Charact. 195, 112474 (2023).

Liu, T., Zheng, Z., Li, Y., Jia, P. & Wang, Y. Improved comprehensive properties induced by multi-phase coexistence in KNN ceramics. Mater. Chem. Phys. 290, 126640 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Enhanced electromechanical response in (K, Na)NbO3-based ferroelectrics by phase boundary and nonstoichiometry engineering. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 155, 107239 (2023).

Lee, M. K., Kim, B. H. & Lee, G. J. Lead-free piezoelectric acceleration sensor built using a (K,Na)NbO3 bulk ceramic modified by Bi-based perovskites. Sensors 23, 1029 (2023).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 63, 3–42 (2006).

Vapnik, V. N. An overview of statistical learning theory. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 10, 988–999 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support of the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFB3807200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52072075, 52102126 and 12104093), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2021J05122, 2021J05123, 2021J06011, 2022J01087, 2023J01259), and Qishan Scholar Financial Support from Fuzhou University (GXRC-20099).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. initiated and supervised the project; B.W.M. conceptualized, collected data, and wrote the manuscript with help and guidance from X.W.; B.S.S. and Z.M.S. conducted the writing review, editing and supervision; C.L.Z., C.L. and M.G. participated in the discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, B., Wu, X., Zhao, C. et al. An interpretable machine learning strategy for pursuing high piezoelectric coefficients in (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3-based ceramics. npj Comput Mater 9, 229 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-01187-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-023-01187-1

This article is cited by

-

PAH101: A GW+BSE Dataset of 101 Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Molecular Crystals

Scientific Data (2025)

-

Machine learning assisted composition design of high-entropy Pb-free relaxors with giant energy-storage

Nature Communications (2025)