Abstract

Condense phase molecular systems organize in wide range of distinct molecular configurations, including amorphous melt and glass as well as crystals often exhibiting polymorphism, that originate from their intricate intra- and intermolecular forces. While accurate coarse-grain (CG) models for these materials are critical to understand phenomena beyond the reach of all-atom simulations, current models cannot capture the diversity of molecular structures. We introduce a generally applicable approach to develop CG force fields for molecular crystals combining graph neural networks (GNN) and data from an all-atom simulations and apply it to the high-energy density material RDX. We address the challenge of expanding the training data with relevant configurations via an iterative procedure that performs CG molecular dynamics of processes of interest and reconstructs the atomistic configurations using a pre-trained neural network decoder. The multi-site CG model uses a GNN architecture constructed to satisfy translational invariance and rotational covariance for forces. The resulting model captures both crystalline and amorphous states for a wide range of temperatures and densities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular crystals are an important class of materials widely used in the pharmaceutical1 and electronics industries2,3,4, as well as high-energy-density materials5,6,7. Molecular modeling plays a key role in the development of a fundamental understanding of these materials and the discovery of new ones with desirable properties8,9,10,11,12. While all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) enables an accurate description of the thermo-mechanical and chemical properties of molecular materials, it remains restricted to sub-micron and sub-millisecond scales, limiting the phenomena that can be described. Thus, particle-based, coarse-grain (CG) modeling is central to connecting the microscopic world to mesoscales and atomistics to the continuum13,14,15,16,17,18. In these models, CG particles or beads represent groups of atoms whose dynamics are governed by a potential of mean force of the atoms.

A critical target of CG models is accurate description of the molecular materials’ structural arrangements that can span from crystalline to amorphous configurations depending on the thermodynamic conditions. Accurate CG descriptions of amorphous polymers have contributed significantly to our understanding of glassy physics19,20 and biomolecules15,21,22. Unfortunately, less progress has occurred in CG representations of molecular crystals, where many molecules of interest form open, low-symmetry crystal structures. Most of the available CG models, a CG model for water being a notable exception23, cannot capture both crystal and melt phases and the transformation between them.

For example, multiple CG models17,24,25,26,27,28 have been developed for the high-energy-density material 1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazinane (RDX) using the multiscale coarse-graining (MSCG/FM) approach, which utilized spline functions to match the forces between groups of atoms13,15,17,25,29. These models can capture either the crystalline or the molten state depending on the dataset used to develop them, but for a given model have been unable to describe the structural characteristics of both states correctly. Specifically, for the so-called RDX-T model30, developed by matching the atomistic forces of a mainly liquid phase dataset of RDX, the mechanical properties as well as the structural properties of the amorphous state of RDX can be correctly captured. However, the crystal state for the RDX-T model is captured as an affinely deformed hcp structure rather than the Pbca structure of the reference atomistic model. Moreover, the melt transition is overestimated for the RDX-T model. A more recently developed model, the so-called RDX-TCDD model25, accurately captures the Pbca crystal structure and exhibits plastic deformation processes similar to the reference atomistic model. However, the liquid phase is more structured with peaks in the radial distribution functions matching those observed from the α-RDX crystals.

In this work, we propose a coarse grain model for RDX based on a graph neural network (GNN) that captures both the low-symmetry molecular crystal and amorphous states. GNNs provide a natural representation of molecular structures, with nodes representing atoms (or groups of atoms in CG descriptions) and edges representing interactions and used to share information about the local environment around atoms31,32. Recent work has shown the significant power of GNNs to represent atomistic force fields33,34,35,36,37,38 trained from extensive sets of accurate electronic structure calculations. However, GNNs are only emerging in the field of CG models39,40,41 with no applications to molecular crystals to date. Prior work has shown that CG GNN39 may reproduce free energy surfaces of small biomolecules more accurately than feedforward neural network models such as CGnet42. In addition, GNN-based models have shown transferability across a range of thermodynamic conditions41,43.

One of the main challenges in the development of CG GNN models, or any molecular model based on machine learning, is the generation of appropriate training sets. The development of machine learning interatomic potentials (ML-FFs) often involves an iterative approach, where configurations explored by MD simulations with ML-FFs are added to the dataset to train new generations of ML-FFs. This process is important because it teaches the model about improbable and high-energy configurations that can lead to catastrophic failures if they are not included in the training dataset. Unfortunately, the approach does not translate directly to CG models, as the reconstruction of an atomistic model from a CG model trajectory is not trivial. While CG ML-FFs have been developed for various materials including proteins44, polymer45, water23,46, and ionic liquids41, most are trained on a fixed dataset that is not updated to improve shortcomings of the dataset such as high-energy configurations with low probabilities explored by the CG model. A recent study45 has utilized active learning approach where atomistic configurations of polymers were reconstructed from CG structures by adding hydrogen atoms stochastically satisfying a bond distance and excluded volume requirements. However, this approach is not generalizable to complex molecules. We address this challenge by developing a neural network decoder that reconstructs atomistic configurations from their CG representations, allowing the expansion of the training dataset for iterative training workflow.

In addition, we formulated two custom GNN architectures to describe inter- and intra-molecular interactions of RDX with forces that are invariant to rigid translations and covariant to rigid rotations, which guarantees the conservation of total linear and angular momenta. We trained the model, named CG-GNNFF, on approximately 106 atomistic configurations. CG-GNNFF correctly reproduces the RDX structure for both crystalline and amorphous states at a wide range of temperatures and densities. In addition, the versatility of the model is demonstrated by extrapolating the model to simulations of faceted nanoparticles that were not included in the training dataset.

Results

Coarse grain graph neural network force field model

The CG-GNNFF architecture is shown in Fig. 1. For the RDX molecule, the atomistic configuration is coarse-grained into a 4-site model using the center of masses of the three nitro groups and the triazine ring, as depicted in Fig. 1a. The CG interactions are represented by two distinct graphs \(({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{intra}}},{{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{inter}}})\) and the associated GNNs to describe forces arising from the intra- and inter-molecular interactions of the atoms \(({F}_{{\rm{intra}}},{F}_{{\rm{inter}}})\), respectively. This choice, similar to the approach taken by Ruza et al. 41, was made because the atomistic forces for the intra- and inter-molecular interactions deviate significantly from each other in terms of both the connectivity and the underlying force field.

a An RDX molecule is coarse grained into a 4-site model with 3 nitro and 1 triazine groups. b Inter-molecular graphs are made with connectivity specified between all CG particles within cutoff distances, excluding the beads that are within the same molecule. c Intra-molecular graphs specify connectivity between nitro and triazine groups of an RDX molecule. Message-passing process for (d) inter- and (e) intra-molecular graphs. Node feature, edge feature, direction vector, GNN layer are denoted as h, e, u, and L, respectively. \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{inter}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{{intra}}\) are the output of the GNN.

\({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{inter}}}({{\mathcal{V}}}_{{\rm{inter}}},{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{inter}}},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{{\rm{inter}}})\), illustrated in Fig. 1b, describes inter-molecular interactions via many-body interactions along each pair of particles within a cutoff distance. The nodes \({{v}_{i,{\rm{inter}}}{{\in }}{\mathcal{V}}}_{{\rm{inter}}}\) represent each CG bead and are assigned initial node features (\({h}^{0}\)) corresponding to one-hot vector of two dimensions that indicates whether the node is a nitro or triazine group. The adjacency matrix for \({{\mathscr{G}}}_{{\rm{inter}}}\) was constructed by assigning connectivity between all CG beads within a cutoff distance, excluding the beads within the same molecule. We choose 9 Å as the cutoff to include the first three peaks of the radial distribution function of α-RDX, the ambient density molecular crystal configuration of RDX. The 4-site model with cutoff distance of 9 Å reduces the number of pairwise distance evaluations approximately 150 times compared to an atomistic model with the typical cutoff distance of 16 Å for ambient density RDX. The intramolecular interaction calculations are decreased approximately tenfold. We also note that the particles receive information beyond the cutoff distance through the multiple layers of message-passing processes in the GNN model, and the CG forces include many-body interactions.

The edge features, \({{e}_{{ij},{\rm{inter}}}{{\in }}{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{inter}}}\), were determined as a four-dimensional vector that is a combination of Gaussian basis functions of \({d}_{{ij}}\), the distance between particle i and j. Detailed descriptions of the edge features and Gaussian bases functions are given in Section 1 of the Supplementary Materials (SM).

Lastly, we store a three-dimensional force direction vector (\({u}_{{\rm{inter}}})\) for each edge, which assigns the direction of force between particle i and j, as explained in detail in the Methods “Graph transformer neural network”. Similar to other direct covariant force models38,47, this vector is designed to enforce the rotational covariance of the model and to ensure that there is no abrupt discontinuity of forces at \({r}_{{\rm{cut}}}\), as described in Eq. (1) and explained in more detail in Supplementary Section 6, Supplementary Figure 8. The magnitude of this vector is equal to \({f}_{c}({d}_{{ij}})\), where \({f}_{c}\) is a cutoff function that smoothly decays to 0 at \({r}_{{\rm{cut}}}\), as defined by Behler et al. 48,

Such choice ensures that the force smoothly decays to 0 at \({r}_{{\rm{cut}}}\). Using these input features, we implement four layers of GNN to output the forces on each bead (denoted as L = 0, 1, 2, and 3 in Fig. 1d).

The intra-molecular interaction graph \({{\mathcal{G}}}_{{\rm{intra}}}({{\mathcal{V}}}_{{\rm{intra}}},{{\mathcal{E}}}_{{\rm{intra}}},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{{\rm{intra}}})\) describes covalent interactions between CG particles in terms of many-body forces along nitro and triazine centers, and angular terms centered around the triazine. The node features are identical to those in \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{{\rm{inter}}}.\) The connectivity between the nodes is assigned according to the intramolecular connectivity. We describe stretching, angular, and torsional interactions of the underlying bonded forces of the atoms as a combination of four forces (Fig. 1e). The stretching force between nitro and triazine pairs, denoted as \({F}_{{\rm{str}}}\), are treated by a single graph. The edge features incorporate the distance between nitro-triazine pairs as well as angles associated with nitro-triazine-nitro triplets, as explained in Supplementary Section 1. The force direction vector (\({u}_{{\rm{str}}}\)) is defined as norm(\({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{\rm{N}}-{\rm{T}}}\)), the normalized displacement vector between the nitro-triazine pair.

The angular interaction forces between the three nitro-triazine-nitro triplets (\({F}_{{\rm{ang}}1}\), \({F}_{{\rm{ang}}2},{F}_{{\rm{ang}}3})\) are treated with separate graphs for each triplet. This choice is made to ensure that the node-level GNN output on the nitro groups for each angular interaction are numerically equal. In this case, we can formulate the total torque on the molecule from the intramolecular interactions to conserve the angular momentum with a judicious choice of the force direction vector \(({u}_{{\rm{ang}}})\). Specifically, we define \({u}_{{\rm{ang}}}\) as \({\rm{norm}}({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{N}_{i}-T}\times {{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{T-{N}_{j}})/|{{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{N}_{i}-T}|\) for the edge between nitro particle i and triazine in the nitro i−triazine−nitro j triplet. The edge features are explained in detail in Supplementary Section 1. The final intramolecular force output is equal to the sum of Fstr, Fang1, Fang2, and Fang3. Lastly, the intramolecular forces on the triazine group are not directly obtained from the GNN, but computed as the negative sum of the forces on the three nitro groups to ensure conservation of linear momentum.

Using such architecture, we trained the CG-GNNFF models that make node-level predictions of the CG forces by updating the initial node features \(({h}^{0})\) through message passing processes. For the message passing step, we use the graph transformer model49 described in detail in the Methods “Graph transformer neural network”.

Iterative training procedure

As ML-FFs are agnostic to the underlying physics of the system except for the symmetries incorporated in the representation of molecular structures or model architecture, their performances are highly dependent on the datasets used to train the models. To obtain datasets representative of physically relevant configurations of molecules, we utilized the iterative training procedure depicted in Fig. 2. For the initial training dataset, we performed canonical ensemble (NVT) atomistic simulations of initially crystalline RDX systems at ambient density and temperatures of 250, 500, and 750 K for 100 ps (Fig. 2a). From these atomistic simulations, we extracted 100 configurations at 1 ps intervals and obtained the mean force acting on each of the four CG beads. This is accomplished via constrained NVT simulations, where the centers of mass of the nitro and triazine groups are fixed at their initial positions (Fig. 2b). The mean atomistic forces \(\left\langle {\bf{f}}\right\rangle\) for the training datasets are obtained from 100 snapshots for 10 ps of constrained NVT simulations. We note that these CG forces correspond to the gradients of the potential of mean forces at the thermodynamic conditions used to generate the training dataset. Thus, the underlying potential and resulting forces are temperature dependent, but we make the assumption, to be justified a posteriori, that a single model can capture the temperature range of interest. More details of the atomistic simulations are given in the Methods “Atomistic and CG molecular dynamics”.

a Atomistic NVT simulations are performed for Gen 0. b Constrained atomistic simulations are performed in which the center of mass positions of the nitro and triazine groups are fixed in space. c CG model positions and forces from constrained atomistic simulations are used to train CG-GNNFF. d CG MD simulations with the trained CG-GNNFF are performed. e Decoder is used to reconstruct CG model trajectories into atomistic trajectories. Constrained atomistic simulations on these trajectories are performed to create the next generation of data.

Using the initial training dataset, denoted generation (Gen) 0, we trained a CG-GNNFF (Fig. 2c) and generated new configurations using a coarse-grain MD simulation with a Langevin thermostat (Fig. 2d) at temperatures of 250, 500, and 750 K. More details are included in Methods “Atomistic and CG molecular dynamics”. During the dynamical simulation, the CG model explored configurations not included within the initial training data, whereby accurate extrapolation of forces from the GNN model for these configurations is not guaranteed. Typically, for atomistic ML-FFs50,51 such configurations are added to the training dataset to enhance the models. However, for the CG models, such expansion of the dataset is not trivial as there is no one-to-one correspondence between the CG and atomistic trajectories. While mapping an atomistic to a CG configuration can be computed simply by using the center-of-mass of the group of atoms, the reverse process is a complex one-to-many problem that does not have an analytical solution.

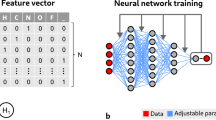

To overcome this challenge, we use a neural network decoder to reconstruct atomistic configurations from the CG model trajectories (Fig. 2e). The decoder is a deep feed-forward neural network whose inputs are a 12-dimensional vector corresponding to the cartesian coordinates of the 4 CG particles of RDX, and whose outputs are a 63-dimensional vector corresponding to the cartesian coordinates of the 21 RDX atoms. The neural network consists of two hidden layers with 12 and 36 nodes in each layer with leaky ReLu activation functions52. The reconstructed atomic positions were adjusted to ensure that the center of masses of the nitro and triazine groups are equal to the CG particle positions. The decoder model was trained on atomistic configurations of the Gen 0 training data. We do not optimize the decoder beyond the Gen 0 dataset, as the current model is sufficient to provide the initial atomistic configurations that are equilibrated through the constrained NVT simulations.

Using the iterative training procedure depicted in Fig. 2, we obtained three generations of datasets with 1.6 million data points. A detailed description of the dataset is given in Supplementary Section 2.

Force prediction accuracy

The intra- and intermolecular GNN models were trained for 3 generations as described in Section 2 of the Supplementary Materials. The model performance for each generation is depicted in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. The force predictions demonstrate significant improvement in accuracy as the model is trained iteratively for Gen 0 and Gen 1. For example, the models trained on Gen 0 data cannot predict the forces exceeding 20 kcal/mol/Å present in Gen 1 data, but the models trained on subsequent generations can accurately capture them. However, training on additional generations after Gen 1 led to small changes in the prediction accuracy of the model. A more detailed description of the generation-dependent force prediction accuracy is given in Supplementary Section 4. The accuracy of the force prediction by the final generation are plotted in Fig. 3. The model performs with equivalent accuracy on both training and test sets, implying that the GNN model captures the underlying relationship between the CG configurations and the forces without overfitting. The force inference displays reasonable accuracies for both inter- (Fig. 3a, b) and intra-molecular (Fig. 3c, d) interactions, with mean absolute errors (MAE) of ~5.3 kcal/(mol \(\cdot\) Å) and ~3.1 kcal/(mol \(\cdot\) Å), respectively.

We also note that the theoretical minimum error of a CG model is limited by the noise in the data as the CG model forces represent the mean force \(\left\langle {\bf{f}}\right\rangle\) from a trajectory of atomistic forces42. This contrasts with the atomistic force fields trained on quantum mechanical data that do not require the calculation of the averages. As each CG configuration represents multiple atomistic configurations, finite sampling leads to uncertainties in the target CG forces. In our case, the average standard deviations of the intra- and inter-molecular forces of the Gen 0 data are 18.43 and 4.76 kcal/(mol \(\cdot\) Å), respectively, over the 100 measurements taken over 10 ps intervals. Using a confidence interval of 95%, the margins of error correspond to 3.6 and 0.9 kcal/(mol \(\cdot\) Å), respectively, for intra- and inter-molecular forces. Such noise in the ground-truth data limits the prediction accuracy of the CG-GNNFF.

Structural properties for bulk simulations

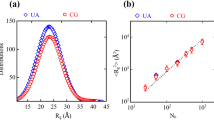

Reproducing the correct structural properties over a wide range of state conditions is a challenging task for CG force fields53. To evaluate the ability of CG-GNNFF to describe the structure of RDX, we first compare the crystalline structures obtained from CG and atomistic simulations at room temperature (300 K) and ambient density (1.8 g/cm3). NVT simulations were performed for 200 ps, and the radial distribution functions of the molecules (gr,mol) over the last 25 ps were computed. The resulting gr,mol along with snapshots are depicted in Fig. 4a, d. From both atomistic and CG simulations, we observe three peaks, P1, P2, P3 at ~4.3, 7.0, and 8.9 Å, respectively. These results demonstrate that the vast majority of molecules maintain the correct spatial group (Pbca) and lattice structures observed from the atomistic simulations, with a few molecules disordered. These results are significant because a previous CG force field for RDX using spline functions30 reported that a 4-site model could not maintain the crystalline configurations above 30 K. Furthermore, with the exception of the recently published RDX-TCDD potential25, many of the CG force fields using 1-site models17,30 led to hexagonally close-packed crystal structures instead of the Pbca space group, which contributes to the discrepancy in plasticity between those CG models and the atomistic model54.

a gr,mol, (b) intramolecular distances between nitro-triazine pairs, (c) intramolecular angles between nitro-triazine-nitro triplets, and (d) overlaying configuration snapshots of the molecules for the atomistic and CG-GNNFF models. The three nearest neighbor peaks from gr,mol (a) are depicted in the snapshot from the [001] perspective.

We further analyze the CG-GNNFF model by comparing to the intramolecular bond distances and angular distributions of the atomistic model. Typically, the RDX conformation is characterized by the out-of-plane bending or wag angle between the N-N bond between the nitro and triazine groups, and the plane formed by the C-N-C atoms in the triazine group55,56,57,58,59. α-RDX molecules consist of two N-N bonds in axial configurations and one bond in an equatorial configuration59. From atomistic trajectories of α-RDX that were converted to CG model center-of-mass representations, we observe intramolecular distances between nitro-triazine pairs in the range of 2.7 to 3.3 Å (Fig. 4b) with a sharp peak at 3.2 Å. In comparison, the CG-GNNFF models lead to broader distributions with peaks observed at 2.5 and 3.3 Å. For the intramolecular angles between the nitro-triazine-nitro triplets, we observe two distinct peaks at 110° and 90° from the atomistic simulations. The CG simulations display a similar peak at 90°, but a broader distribution above 110°.

Several factors may contribute to the broader distribution of the intramolecular configurations for the CG-GNNFF model. First, the CG-GNNFF model is trained on the mean force from atomistic simulations for a given CG configuration. Studies have reported that such mean-force models may underrepresent the frictional forces between molecules because the high-frequency motions of the hydrogen atoms are not explicitly captured41. Second, the stretching between the nitro and triazine group in the atomistic model represents two distinct molecular mechanics: the stiff stretching of the N-N bond whose stretching constant in the atomistic force field is 991.7 kcal/mol/Å, and the displacement of atoms within the groups that adjust their centers-of-masses. As the CG representation does not directly distinguish these two mechanisms, the intramolecular stretching with the CG force field may be softer than the instantaneous stretching of the N-N bonds in the atomistic model. Despite the broader distribution, we find that the CG-GNNFF performs well in describing the structure of RDX for a wide range of conditions as illustrated below.

Next, we evaluate the temperature-dependent structural properties up to 800 K; we will contrast not just the equilibrium structures, but also the kinetics of the process of melting. From the atomistic simulations, we observe that the crystallinity is maintained over the 200 ps for the NVT simulations at temperatures up to 500 K. At 650 K, symmetry breaking and loss of crystalline order becomes evident by the disappearance of the P1 and P3 peaks in gr,mol, as well as from snapshots viewed from [010] and [001] orientations. The CG model displays similar temperature dependence, where at 500 K, we observe that most of the CG particles remain at their lattice positions, although the P1 peak broadens as a few CG particles become slightly disordered. At 800 K, the P1 peak disappears completely resulting in a melt structure with a pair correlation function gr,mol in excellent agreement with the atomistic model. At the intermediate temperature of 650 K, the CG particles become partially disordered, but the P1 peak does not fully disappear within 200 ps, whereas in the atomistic simulations the peak disappears at ~30 ps (time-dependence of the atomistic model is not plotted).

We evaluate the extrapolation capability of the CG-GNNFF model to conditions outside the training dataset and study the structures at high density of 2.16 g/cm3, prepared from NPT atomistic simulations with pressure of 5 GPa (Fig. 6a). The results demonstrate that the crystal structures of both the atomistic and CG models remain in the Pbca space group. The gr,mol peaks decrease from 4.3 Å and 7.0 Å for P1 and P2 at ambient (1.8 g/cm3) density to 4.15 Å and 6.45 Å at 2.16 g/cm3. Such changes are observed from both atomistic and CG simulations, demonstrating that CG-GNNFF can correctly capture density effects.

We also simulated the CG and atomistic models for configurations that were initially amorphous (Fig. 6b). We performed simulations for a range of temperatures (250–750 K) and densities (1.8–2.6 g/cm3), and observe that the gr,mol functions are similar to those obtained from the structures at high temperatures (Fig. 5c) for simulations of initially crystalline configurations, marked by the disappearance of P1 peaks. The CG model captures this structural characteristic of amorphous configurations, as depicted in Fig. 6b.

gr,mol and simulation configuration snapshots at ambient density and varying temperatures (a) 500 K, (b) 650 K, and (c) 800 K for 200 ps simulation times. In the snapshots below the plots in the perspective of the [010] and [001] orientations, red circles indicate the CG particles, while blue circles represent the atomistic model center-of-mass.

a gr,mol of a crystalline structure at density of 2.16 g/cm3. b gr,mol of an initially amorphous sample. c gr,mol obtained from the CG model with raw coordinate input at 300 K and 1.8 g/cm3. For the configuration snapshots shown below the plots for the [010] and [001] orientations, red circles indicate the CG particles, while blue circles represent the atomistic model centers-of-mass.

Finally, we note that the molecular crystal structural properties are highly sensitive to the model formulation. For example, we have also trained a GNNFF model with raw coordinates of the interparticle distances and angles as inputs instead of the descriptors obtained from the Gaussian basis functions. Detailed descriptions of these models are given in Supplementary section 1. The structural properties of the raw GNN model for initially crystalline, room temperature, and ambient density conditions are depicted in Fig. 6c. While the snapshots demonstrate that the majority of molecules are in their lattice positions in the Pbca space group, we see that the P1 peak is less distinct compared to the model with Gaussian basis functions, indicating more disordered molecules compared to results shown in Fig. 4a. This is because the intricate atomistic interactions that determine the structure of molecular crystals are not monotonous functions of the molecular configurations. RDX molecules display polymorphic phases because various interactions including stretching, bending, dihedral, improper dihedral, van der Waals, and coulombic forces of the diverse atoms act with distinct functional forms with respect to the molecular configurations. While in principle GNN can learn to describe these behaviors correctly with raw inputs, we find that guiding the model with Gaussian basis functions designed from the dataset is more beneficial in practice. Such findings demonstrate the intricacy of correctly describing the structure of molecular crystals.

Model performance for faceted nanoparticles

As an additional evaluation of the model performance for conditions outside its training dataset, we simulate the structural properties of faceted nanoparticles (NP) of RDX at varying temperatures. Such simulations require the model to capture free surfaces with asymmetric interaction geometries compared to the bulk systems that the model was trained upon. The faceted NPs were prepared according to the procedure outlined by Li et al.60, with the longest and shortest dimension lengths of 6 nm and 4 nm, respectively. We analyzed the structure of the molecules depending upon their positions and time for temperatures ranging from 300 to 600 K. To analyze surface phenomena, molecules were categorized as belonging to the core if they were within 2 nm of the center-of-mass of the NP, while belonging to the surface otherwise. Importantly, we analyzed not only the equilibrium state at various temperatures, but also the kinetics associated with the melting of the NPs.

Figure 7 compares radial distribution functions for the core and surface molecules and the molecular structures between the atomistic and CG models. As expected, the initially crystalline NPs lose crystallinity as the temperature is increased, where this process initiates at the free surfaces. We observe minor discrepancies between the atomistic and CG models in the core, where molecules of the atomistic model become disordered faster, while the surface molecules remain slightly more crystalline. Specifically, the core remains crystalline at 300 K and 400 K (Fig. 7a, b) for both the CG and atomistic models, with some disorder for the CG model demonstrated by a reduction in sharpness of the P1 peak at 200 ps. At 500 K, the core molecules of the atomistic simulations are partially disordered after 100 ps and completely amorphous after 200 ps (Fig. 7c), as well as at 600 K (Fig. 7d). The CG particles are partially disordered throughout the simulation at 500 K, and up to 100 ps for the 600 K simulations. At 600 K and 200 ps, the core CG particles are completely amorphous, matching the behavior observed from the atomistic simulations. For the surface molecules, the atomistic model leads to a crystalline structure for the duration of the simulation at 300 K, whereas the CG model leads to partially disordered structures at 200 ps (Fig. 7a). Above this temperature, the surface molecules are mostly in amorphous states for both models. Overall, similar to the bulk simulation behavior, we observe that the CG model simulations for the faceted NPs lead to similar but more disordered structures compared to the atomistic model simulations.

Discussion

In this study, we present a CG force field for a molecular crystal that can capture both low-symmetry crystal structures as well as amorphous structures. The GNN force field was formulated to conserve the total linear and angular momentum from the intramolecular interactions that include two- and three-body interactions, which has not been previously considered in direct force prediction models38,47. Gaussian basis functions were designed based on the molecular configurations to emphasize the crystal symmetry. The CG model was iteratively improved by expanding the training dataset through the development of a neural network decoder that reconstructs atomistic model configurations from CG model trajectories.

While the GNN model captures both the crystal and amorphous structures over a wide range of densities and temperatures including the structure of nanoparticles that were not in the training dataset, it also displays few discrepancies with respect to the atomistic models. First, the radial distribution peaks for the crystalline configurations are not as sharp for the CG model indicating more disorder. In addition, we note differences in the dynamics between the two models as demonstrated by the mean squared displacement over time depicted in Supplementary Figure 9. Such deviation is a well-documented phenomenon in previous studies of CG models22,41,61,62,63,64 that could be alleviated through the use of CG model methodologies such as incorporating dissipative particle dynamics or scaling of dynamics as noted by Brennan et al.65. Such differences in dynamics may be responsible for the discrepancies in structures as our observation time is fixed at 200 ps. For example, while the reported melting temperature of RDX is 488 K66, our atomistic 200-ps simulations at 500 K show a rigidly crystalline structure indicating that the structure has not reached its thermodynamically stable configuration in the simulated time frame. Therefore, the discrepancy in structural properties between the atomistic and CG models may be due to the difference in the kinetics of the two models. Overall, we attribute these deficiencies to the design of the CG model. Even for the ideally trained model, the CG model describes the mean force of a group of atoms at ps time scales, whereas the time steps for the CG simulations are in the fs scales. With such data curation protocol, the mean forces are obtained from energy minimized configurations, leading to underrepresentation of energetically unfavorable configurations that may act as energetic barriers against certain configurational transitions. Therefore, the resolution and time-scale of the CG model prevents a precise description of key factors such as frictional forces or details of the rugged free-energy landscape of the molecular crystals.

A key contribution of this study is the use of a decoder for reconstructing atomistic configurations to enhance the training data. Most CG ML force fields do not iteratively expand their training datasets and instead use a single dataset developed using expert knowledge. Previous CG ML potential45 that used an iterative approach reconstructed the atomistic configuration from the CG configurations for simple polymers that cannot be generalized to more complex materials. In contrast, we used an ML decoder that affords several advantages. First, a more accurate reconstruction results in faster equilibration of the subsequent atomistic simulation and reduces the risk of bad contacts between atoms. For example, RDX is a polymorphic molecule with many stable conformations depending on its thermodynamic conditions and other factors such as interaction with other materials67,68. It is difficult to predefine templates or rules accounting for all such cases, while ML models69,70 can learn to generate suitable structures that would require less equilibration. Second, the ML approach is data-driven and the model performance can be improved during the iterative data generation process. Third, the decoders are more generalizable to other complex molecules for which templated or rules-based generation may not be obvious.

Several extensions of the model can be pursued as future work. First, while the potential of mean force is temperature dependent, our model does not explicitly account for the effect of the temperature. However, our work shows that a single model describes the structures between 250 and 800 K. This is consistent with a recent study43 that suggests that a CG-GNNFF model may be more thermodynamically transferable than CG models utilizing multi-scale coarse grain method13 due to the incorporation of many-body effects. Future work should characterize the degradation of accuracy as the model is used away from these thermodynamic conditions. Approaches such as using the thermodynamic condition as inputs to the model41 are also worth pursuing.

Second, the current model is non-reactive and is not suitable for phenomena such as chemical reactions or diffusion of species that are important for energetic materials. In general, CG frameworks17,71 incorporate such phenomena by treating the molecular properties, such as interaction forces, as functions of the chemical composition. For GNNFF, the chemical species can be treated as state variables for each molecule that is used as additional input to the model.

Another possible extension is to use uncertainty quantification to expand the training data. While our data generation is from evenly spaced configurations, recent ML-FFs45,72 have used active learning approaches that prioritize configurations with high uncertainty. In addition, the current model predicts only the mean forces obtained from canonical sampling of the atomistic of the forces. Training the model to predict, in addition, the force distributions may be useful to inform stochastic dynamical approaches like Langevin dynamics but would add to the computational intensity of the model. Finally, the architectural complexity of the model and the associated computational intensity have not been considered in this work and should be considered in future work.

Methods

Graph transformer neural network

The graph transformer neural network49 is used for the CG-GNNFF. In this model, the query (\({q}_{c,i}^{l}\)), key (\({k}_{c,j}^{l}\)), value (\({v}_{c,j}^{l}\)), and edge (\({e}_{c,{ij}}^{l}\)) vectors for the edge between node i and j of GNN layer l is given by,

Here, \(q,{k},{v}\) are vectors with dimension \(H\) equal to the size of the hidden embedding for the layer, while \(W\) and \(b\) are trainable parameters. \(c\) represents the index of the attention head. The multi-headed attention (\({\alpha }_{c,{ij}}^{l})\) is then calculated as,

where \(\left\langle q,k\right\rangle =\exp \left(\frac{{q}^{T}k}{\surd d}\right)\).

Messages for node i are aggregated from all its neighbors (\({\mathscr{N}}\)) according to,

The message passing procedure for the last layer (\(l=L\)) differs from the other layers as it incorporates a force direction vector (\({u}_{{ij}}\), described in “Coarse grain graph neural network force field model”) that specifies the node features partitioning into the force directions. Therefore, the force on each CG bead (\({F}^{{\rm{GNN}}}\)) is determined in the last layer according to

where the index k ∈ (x, y, z) indicates the Cartesian axis of the force. For intermolecular forces, Newton’s third law of motion is enforced by formulating the forces as \({F}_{i,k}^{{\rm{GNN}}}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{c=1}^{C}\sum _{j\in {\mathcal{N}}{{(}}i)}\left[{\alpha }_{c,{ij}}^{l}\left({v}_{c,j}^{l}+{e}_{c,{ij}}^{l}\right)+{\alpha }_{c,{ji}}^{l}\left({v}_{c,i}^{l}+{e}_{c,{ji}}^{l}\right)\right]/2* {u}_{{ij},k}.\)

The hyperparameters of the GNN are the size of the hidden embeddings (H), number of attention heads (C), and number of message passing layers (L). We chose H = 8, C = 5, and L = 4 (inter) and L = 5 (intra) because such hyperparameters led to good accuracy in force prediction and structural properties, while increasing the number of parameters did not lead to a significant increase in the accuracy.

The GNNs were trained with a stochastic gradient descent optimizer with momentum of 0.7 and learning rate of 0.005 for 2000 epochs. The training and test dataset were split 80/20. The loss function was the mean squared error between the GNN output (\({F}_{x}^{{\rm{GNN}}},{F}_{y}^{{\rm{GNN}}},{F}_{z}^{{\rm{GNN}}}\)) and the CG model forces obtained from the atomistic model simulations (\({F}_{x}^{{\rm{CG}}},{F}_{y}^{{\rm{CG}}},{F}_{z}^{{\rm{CG}}}\)).

Atomistic and CG molecular dynamics

Atomistic model simulations of RDX utilized the Smith and Bharadwaj (SB) potential73 that has been shown to accurately capture the structural properties of RDX. Crystalline configurations of RDX were prepared by creating a 3 \(\times\) 3 \(\times\) 3 supercell of α-RDX, whose initial configuration was obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre74. Samples were equilibrated by running isobaric and isothermal (NPT) ensemble simulations for 10 ps, followed by production simulations conducted within the canonical ensemble (NVT). The temperatures ranged from 250 K to 800 K and pressures ranged from 0 to 20 GPa. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat were used. All atomistic simulations were performed with Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator75.

In addition to the crystalline configurations, amorphous structures were prepared following the procedure by Sakano et al.76. First, crystalline samples were heated to 800 K for 200 ps and equilibrated at 800 K for 300 ps at ambient pressure using the NPT ensemble. Next, the simulation cells were deformed under the NVT ensemble to match the densities obtained from NPT simulations of crystalline RDX.

For the CG model simulations, we obtain initial configurations from the center-of-masses of the nitro and triazine groups from the atomistic model trajectories. Langevin dynamics (LD) were utilized to run the NVT simulations. CG simulation codes were written in-lab with Python. The Pytorch Geometric package with necessary modifications for our model was used to build the GNN. The code for the CG simulations is provided in github (https://github.itap.purdue.edu/StrachanGroup/CG_GNNFF).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material includes detailed explanation of the model input features and associated weights, description of the training dataset, employed prior forces, generation dependent force prediction accuracy, hyperparameter testing, numerical test of rotational covariance of forces, and mean squared displacement data.

Data availability

Data used to train and test the CG-GNNFF as well as the best model are available along with the source code at https://github.itap.purdue.edu/StrachanGroup/CG_GNNFF. Additional data is available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes associated with the model training, decoder to reconstruct CG configurations from atomistic trajectories, and Langevin dynamics are available at: https://github.itap.purdue.edu/StrachanGroup/CG_GNNFF.

References

Datta, S. & Grant, D. J. W. Crystal structures of drugs: advances in determination, prediction and engineering. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 42–57 (2004).

Chung, H. & Diao, Y. Polymorphism as an emerging design strategy for high performance organic electronics. J. Mater. Chem. C. 4, 3915–3933 (2016).

Ruzié, C. et al. Design, synthesis, chemical stability, packing, cyclic voltammetry, ionisation potential, and charge transport of [1]benzothieno[3,2- b][1]benzothiophene derivatives. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 4863–4879 (2016).

Liu, K. et al. A wafer-scale van der Waals dielectric made from an inorganic molecular crystal film. Nat. Electron. 4, 906–913 (2021).

Cady, H. H., Larson, A. C. & Cromer, D. T. The crystal structure of α-HMX and a refinement of the structure of β-HMX. Acta Cryst. 16, 617–623 (1963).

Bedrov, D. et al. Molecular dynamics simulations of HMX crystal polymorphs using a flexible molecule force field. J. Comput. Matter Des. 8, 77–85 (2001).

McCrone, W. C. Crystallographic Data. 32. RDX (Cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine). Anal. Chem. 22, 954–955 (1950).

Zhao, L. et al. A novel all-nitrogen molecular crystal N 16 as a promising high-energy-density material. Dalton Trans. 51, 9369–9376 (2022).

Pandey, P. et al. Discovering crystal forms of the novel molecular semiconductor OEG-BTBT. Cryst. Growth Des. 22, 1680–1690 (2022).

Cazorla, C. & Boronat, J. Simulation and understanding of atomic and molecular quantum crystals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035003 (2017).

Proville, L., Rodney, D. & Marinica, M.-C. Quantum effect on thermally activated glide of dislocations. Nat. Mater. 11, 845–849 (2012).

Merchant, A. et al. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 624, 80–85 (2023).

Noid, W. G. et al. The multiscale coarse-graining method. I. A rigorous bridge between atomistic and coarse-grained models. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 244114 (2008).

Wang, W. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Coarse-graining auto-encoders for molecular dynamics. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–9 (2019).

Izvekov, S. & Voth, G. A. A multiscale coarse-graining method for biomolecular systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 2469–2473 (2005).

Webb, M. A., Delannoy, J. Y. & De Pablo, J. J. Graph-based approach to systematic molecular coarse-graining. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1199–1208 (2019).

Moore, J. D. et al. A coarse-grain force field for RDX: Density dependent and energy conserving. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 104501 (2016).

Zhang, L., Han, J., Wang, H. & Car, R. DeePCG: constructing coarse-grained models via deep neural networks. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 034101 (2018).

Salerno, K. M., Agrawal, A., Perahia, D. & Grest, G. S. Resolving dynamic properties of polymers through coarse-grained computational studies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 058302 (2016).

Paul, W. & Smith, G. D. Structure and dynamics of amorphous polymers: computer simulations compared to experiment and theory. Rep. Prog. Phys. 67, 1117–1185 (2004).

Monticelli, L. et al. The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 819–834 (2008).

Marrink, S. J., Risselada, H. J., Yefimov, S., Tieleman, D. P. & De Vries, A. H. The MARTINI Force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 7812–7824 (2007).

Chan, H. et al. Machine learning coarse grained models for water. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–14 (2019).

Izvekov, S., Larentzos, J. P., Brennan, J. K. & Rice, B. M. Bottom-up coarse-grain modeling of nanoscale shear bands in shocked α-RDX. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 10627–10648 (2022).

Izvekov, S. & Rice, B. M. Bottom-up coarse-grain modeling of plasticity and nanoscale shear bands in α-RDX. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 064503 (2021).

Lee, B. H., Sakano, M. N., Larentzos, J. P., Brennan, J. K. & Strachan, A. A coarse-grain reactive model of RDX: Molecular resolution at the μm scale. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 024702 (2023).

Lísal, M., Larentzos, J. P., Avalos, J. B., Mackie, A. D. & Brennan, J. K. Generalized energy-conserving dissipative particle dynamics with reactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 2503–2512 (2022).

Lísal, M., Larentzos, J. P., Sellers, M. S., Schweigert, I. V. & Brennan, J. K. Dissipative particle dynamics with reactions: Application to RDX decomposition. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 114112 (2019).

Ercolesi, F. & Adams, J. B. Interatomic potentials from first-principles calculations: the force-matching method. Europhys. Lett. 26, 583 (1994).

Izvekov, S., Chung, P. W. & Rice, B. M. Particle-based multiscale coarse graining with density-dependent potentials: application to molecular crystals (hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-s-triazine). J. Chem. Phys. 135, 044112 (2011).

Csáji, B. C. Approximation with artificial neural networks. Fac. Sci. Etvs Lornd Univ. Hung. 24, 7 (2001).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2, 359–366 (1989).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 1–18 (2022).

Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–15 (2023).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-Equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–11 (2021).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Gasteiger, J., Groß, J. & Günnemann, S. Directional message passing for molecular graphs. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2020).

Park, C. W. et al. Accurate and scalable graph neural network force field and molecular dynamics with direct force architecture. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–9 (2021).

Husic, B. E. et al. Coarse graining molecular dynamics with graph neural networks. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 194101 (2020).

Fu, X., Xie, T., Rebello, N. J., Olsen, B. D. & Jaakkola, T. Simulate time-integrated coarse-grained molecular dynamics with geometric machine learning. In Transactions on Machine Learning Research (2023).

Ruza, J. et al. Temperature-transferable coarse-graining of ionic liquids with dual graph convolutional neural networks. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 164501 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Machine learning of coarse-grained molecular dynamics force fields. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 755–767 (2019).

Shinkle, E. et al. Thermodynamic transferability in coarse-grained force fields using graph neural networks. arXiv:2406.12112 (2024).

Majewski, M. et al. Machine learning coarse-grained potentials of protein thermodynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 5739 (2023).

Duschatko, B. R., Vandermause, J., Molinari, N. & Kozinsky, B. Uncertainty driven active learning of coarse grained free energy models. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 9 (2024).

Loeffler, T. D., Patra, T. K., Chan, H. & Sankaranarayanan, S. K. R. S. Active learning a coarse-grained neural network model for bulk water from sparse training data. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 5, 902–910 (2020).

Mailoa, J. P. et al. A fast neural network approach for direct covariant forces prediction in complex multi-element extended systems. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 471–479 (2019).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Shi, Y. et al. Masked label prediction: unified message passing model for semi-supervised classification. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence (2021).

Smith, J. S., Nebgen, B., Lubbers, N., Isayev, O. & Roitberg, A. E. Less is more: sampling chemical space with active learning. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241733 (2018).

Yoo, P. et al. Neural network reactive force field for C, H, N, and O systems. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–10 (2021).

Maas, A. L., Hannun, A. Y. & Ng, A. Y. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. Proc. icml 30, 3 (2013).

Ye, H., Xian, W. & Li, Y. Machine learning of coarse-grained models for organic molecules and polymers: progress, opportunities, and challenges. ACS Omega 6, 1758–1772 (2021).

Rice, B. M. A perspective on modeling the multiscale response of energetic materials. AIP Conf. Proc. 1793, 020003 (2017).

Millar, D.I. et al. The crystal structure of β-RDX—an elusive form of an explosive revealed. Chem. Commun. 5, 562–564 (2009).

Millar, D. I. A. et al. Pressure-cooking of explosives—the crystal structure of ε-RDX as determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Chem. Commun. 46, 5662–5664 (2010).

Munday, L. B., Chung, P. W., Rice, B. M. & Solares, S. D. Simulations of high-pressure phases in RDX. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 4378–4386 (2011).

Davidson, A. J. et al. Explosives under pressure—the crystal structure of γ-RDX as determined by high-pressure X-ray and neutron diffraction. CrystEngComm 10, 162–165 (2008).

Choi, C. S. & Prince, E. The crystal structure of cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine. Acta Crystallogr. B 28, 2857–2862 (1972).

Li, C., Hamilton, B. E., Shen, T., Alzate, L. & Strachan, A. Systematic builder for all‐atom simulations of plastically bonded explosives. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 47, e202200003 (2022).

Baron, R., de Vries, A. H., Hünenberger, P. H. & van Gunsteren, W. F. Configurational entropies of lipids in pure and mixed bilayers from atomic-level and coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 15602–15614 (2006).

Roy, D., Patel, N., Conte, S. & Maroncelli, M. “Dynamics in an idealized ionic liquid model,”. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 8410–8424 (2010).

Nielsen, S. O., Lopez, C. F., Srinivas, G. & Klein, M. L. Coarse grain models and the computer simulation of soft materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, R481–R512 (2004).

Depa, P., Chen, C. & JMaranas, J. K. Why are coarse-grained force fields too fast? A look at dynamics of four coarse-grained polymers. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 014903 (2011).

Brennan, J. K. et al. Coarse-grain model simulations of nonequilibrium dynamics in heterogeneous materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 2144–2149 (2014).

Sellers, M. S., Lísal, M. & Brennan, J. K. Free-energy calculations using classical molecular simulation: application to the determination of the melting point and chemical potential of a flexible RDX model. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 7841–7850 (2016).

Wallis, E. P. & Thompson, D. L. Molecular dynamics simulation of conformational changes in gas-phase RDX. Chem. Phys. Lett. 189, 363–370 (1992).

Xu, W. Sen, Zhu, J., Hu, Y. F. & Ji, G. F. Molecular dynamics study on the reaction of RDX molecule with Si substrate. ACS Omega 8, 4270–4277 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Generative coarse-graining of molecular conformations. In Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (2022).

An, Y. & Deshmukh, S. A. Machine learning approach for accurate backmapping of coarse-grained models to all-atom models. Chem. Commun. 56, 9312–9315 (2020).

Avalos, J. B., Lísal, M., Larentzos, J. P., Mackie, A. D. & Brennan, J. K. Generalized energy-conserving dissipative particle dynamics with mass transfer. Part 1: theoretical foundation and algorithm. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 7639–7652 (2022).

Vandermause, J. et al. On-the-fly active learning of interpretable Bayesian force fields for atomistic rare events. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 1–11 (2020).

Smith, G. D. & Bharadwaj, R. K. Quantum chemistry based force field for simulations of HMX. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 3570–3575 (1999).

Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P. & Ward, S. C. The Cambridge structural database. Acta Crystallogr. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 72, 171–179 (2016).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Sakano, M., Hamilton, B., Islam, M. M. & Strachan, A. Role of molecular disorder on the reactivity of RDX. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 27032–27043 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Brenden Hamilton for many insightful discussions and comments. This research was sponsored by the Army Research Laboratory and was accomplished under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-20-2-0189. This work was supported in part by high-performance computer time and resources from the DoD High Performance Computing Modernization Program. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Laboratory, or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.H.L. and A.S. were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. B.H.L was responsible for the model development, investigation, data analysis, and writing original draft. J.P.L. and B.H.L. were responsible for data collection. J.P.L., J.K.B., and A.S. were responsible for supervision. All authors contributed to the writing-review and editing as well as discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, B.H., Larentzos, J.P., Brennan, J.K. et al. Graph neural network coarse-grain force field for the molecular crystal RDX. npj Comput Mater 10, 208 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01407-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01407-2

This article is cited by

-

Coarse-grained machine learning potential for mesoscale multilayered graphene

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Crystal hypergraph convolutional networks

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

DeepEMs-25: a deep-learning potential to decipher kinetic tug-of-war dictating thermal stability in energetic materials

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Unsupervised Graph-GAN model for stress–strain field prediction in a composite

Journal of Materials Science (2025)