Abstract

Magnetic skyrmions are potential candidates for high-density storage and logic devices because of their inherent topological stability and nanoscale size. Two-dimensional (2D) Janus transition metal chalcogenides (TMDs) are widely used to induce skyrmions due to the breaking of inversion symmetry. However, the experimental synthesis of Janus TMDs is rare, which indicates that the Janus configuration might not be the most stable MXY structure. Here, through machine-learning-assisted high-throughput first-principles calculations, we demonstrate that not all MXY compounds can be stabilized in Janus layered structure and a large proportion prefer to form other configurations with lower energy than the Janus configuration. Interestingly, these new configurations exhibit a strong Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI), which can generate and stabilize skyrmions even under a strong magnetic field. This work provides not only an efficient method for obtaining ferromagnetic materials with strong DMI but also a theoretical guidance for the synthesis of TMDs via experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the most typical chiral magnetic structures, magnetic skyrmions have been regarded as promising candidates for future spintronic devices1,2,3. Microscopically, the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI), which favors canted spin configurations, plays an essential role in the formation of skyrmions. The existence of DMI is generally believed to require both magnetism and strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC), as well as a system with broken inversion symmetry4,5. Several materials with DMI have been found, such as MnSi, FeGe, BaTiO3/SrRuO3 superlattices and 2D Janus transition metal chalcogenides (TMDs)6,7,8. Among them, 2D Janus TMDs are an archetypal class of graphene analogs in which one atomic layer is replaced by other atoms. This unique structure breaks the inversion symmetry and is considered as an excellent carrier for generating skyrmions9,10. Several Janus skyrmion systems have been widely studied theoretically, such as CrXTe (X = S,Se)11, MnXY (X,Y = S, Se, Te, X ≠ Y)12,13 and VXSe (X = S,Te)14. These works highlight the possibility of tuning basic magnetic parameters and even inducing distinct spin textures in Janus magnets.

While the number of theoretical studies on Janus TMDs continues to increase, experimental characterization efforts are lacking. To date, only two syntheses have focused on Janus MoSSe and WSSe15,16, while no other successful syntheses of Janus chalcogenide systems have been reported. One of the possible reasons for the lack of experimental data is that the Janus configuration might not be more stable than the other MXY configurations. Previous works have focused only on the ordered layered arrangement of atoms9, while other arrangements of X and Y atoms have not yet been considered. Thus, previous theoretical works are insufficient to guide experimental synthesis. Searching for 2D Janus materials that can be synthesized requires us to clarify whether the Janus structure is the most stable structure among all the possible AXY structures at the same atomic ratio.

Generally, finding the most stable structure requires high-throughput calculations. However, the computational cost is high. This is especially true when the number of structure candidates is large. For example, searching for the optimal structure for one type of MXY with a 4 × 4 × 1 supercell requires tens of thousands of computational tasks, and the calculation time for each task using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)17,18 is 3 hours with a 96-core node. Thus, it is necessary to determine an efficient way to reduce the computational cost. An alternative way to overcome this time-consuming problem is to introduce machine learning techniques. Finding the optimal structure from different atom arrangements is similar to that from different defect positions or doping positions, and several works have successfully used machine learning methods to determine the distribution of defects or doped atoms18,19,20,21,22,23. These works suggested that machine learning methods can be used to construct surrogate models and assist in time-consuming Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

In this work, we constructed massive possible structures for 2D MXY TMDs and compared their energies calculated from DFT. A machine learning method, i.e., the support vector regression method, is adopted to accelerate this process. The Janus structure has the lowest energy in only a few chemical compositions, while most other chemical compositions favor two anti-Janus structures. Although some TMDs do not possess a Janus structure, a considerable DMI still exists among them. Furthermore, based on the magnetic exchange parameters calculated from DFT, we obtained richer spin textures than Janus structures by spin dynamic simulation and successfully predicted skyrmions in those structures.

Results

Lattice structure of Janus TMDs

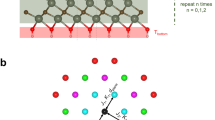

Janus TMDs have two main polytypes depending on the arrangement of chalcogen atoms24. As the transition metal atom is bonded with the six nearest chalcogen atoms, a triangular prism or octahedron can be formed; the left one is termed 1T-phase, and the right one is termed 2H-phase, with space groups P-3m1 (space group 164) and P-6m2 (space group 187), as shown in Fig. 1a and b, respectively. The stabilities of the 1T-phase and 2H-phase in 2D TMDs have been discussed in the literature9,11,12,14,25,26,27,28,29,30. Therefore, we fixed the phase of 2D TMDs while searching for the configurations with the lowest energy. To verify our hypothesis that the Janus structure has the lowest energy among the structures with the same components (i.e., a 1:1 ratio of chalcogen atoms), we selected 11 transition metals, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Ni, Zr, Nb, Hf, W, Re, and Pd. We started our simulation with a unit cell, which does not have a disordered arrangement of atoms. Our calculated ground states are consistent with those of previous studies9,11,12,14,25,26,27,28,29,30. Next, we constructed 2 × 2 × 1, 3 × 3 × 1 and 4 × 4 × 1 supercells and generated all possible irreducible structures via disorder software31. With increasing size, the number of irreducible structures increases greatly. A 2 × 2 × 1 supercell produces ten possible structures, while a 3 × 3 × 1 supercell contains more than 500 structures. When the size of the supercell reaches 4 × 4 × 1, the number of structures exceeds tens of thousands. Such a large number makes it unrealistic to determine the most stable structure by calculating all of their energies. Thus, it is necessary to use machine learning to assist this computational process.

SVR assisted DFT calculations for screening new structures

Here, we employed the support vector regression (SVR) method to predict the energy of each structure instead of performing DFT calculations, as shown in Fig. S16 in the Supplemental Material. For each type of MXY, we performed the following procedure to obtain the structure with minimum energy. First, we trained the SVR model with 100 random structures and predicted 20 structures with the lowest energy. Then, we used DFT calculations to verify these predictions. If the energy sequence of these 20 structures from the DFT results does not agree with the SVR model, we add 100 more structures, which are predicted by the SVR model to have the lowest energy, to the training data. Once the DFT results provide an energy sequence similar to that of the SVR model, we stop the loop and obtain the structure with the lowest energy. The locations of the X and Y atoms are regarded as descriptors, and the structures with the lowest energy are obtained through the above procedure. We first verified the effectiveness of this procedure on CrSeTe, whose energies of all the possible structures were obtained from DFT calculations. Fig. 2a–c show the comparison between the predictions from the SVR model and DFT calculations, while the training data increase from 200 to 400. With increasing training data, the SVR model becomes increasingly accurate. The energy sequences of the different structures from the SVR predictions are almost the same as those from the DFT calculations, especially in the low-energy region. Furthermore, with the increasing of training data from 300 to 400, the most stable structure predicted with SVR model remain unchanged. Subsequently, we examined the energy sequence in the low energy region and calculated R2 for the 20 points predicted to have lowest structures. Fig. 2d shows the energy sequence in the low-energy region predicted with the SVR model and its comparison with DFT calculations. The R2 for these 20 points is larger than 0.9. Thus, we can regard our predicting procedure is converged. The SVR model successfully predicted the most stable structure of CrSeTe and the energy comparison between the prediction from SVR model and DFT calculations for other magnetic materials can be found in Fig. S17-S22 and Table S4 in the Supplemental Material. These results demonstrate that the SVR model is sufficient for identifying the most stable structure of MXY. The computational cost was reduced from thousands to 400, which significantly accelerated our investigation of MXY materials.

The training sets of a–c are 200, 300 and 400, respectively. d Twenty structures with the lowest energy predicted with the SVR model and their comparison with DFT calculations. The energy difference on the most stable structure is 0.00378 eV/unit cell, and the R for test sets is 0.8714. The energy sequence predicted by the SVR model is similar to that predicted by DFT calculations, which indicates that we have found the most stable structure of CrSeTe.

Based on machine-learning-assisted high-throughput calculations, we obtained the most stable structure of MXY (M=Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Ni, Zr, Nb, Hf, W, Re, Pd; X, Y = S, Se, Te). The most stable structure does not require atoms to be arranged in layers, and in addition to the Janus structure, there are two alternative structures that can have the lowest energy. We named the newly discovered structures “anti-Janus” due to the opposite atomic stacking method. The Janus structures exhibit order in the out-of-plane z-direction, while the anti-Janus structures exhibit in-plane order. In this work, we used Structure I (S1) to represent the Janus structure, while the anti-Janus structures are represented by Structure II (S2) and Structure III (S3). S2 and S3 in the 1-T phase are illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. The S2 and S3 atoms in the 2-H phase are illustrated in Fig. 3c, d. The X atoms are clearly arranged alternately with the Y atoms, which is different from the Janus structure.

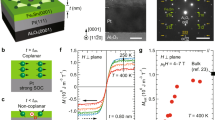

The energies of MXY in the S1, S2 and S3 structures are shown in Fig. 4, and they are divided into three categories according to the ground state. The color represents the energy relative to the ground state. The Janus structure (S1) has the lowest energy only in TiXY, ZrXY, and CrXY (X, Y = S, Se, Te, X ≠ Y), while either the S2 or S3 structure is the ground state in the other systems. The energy differences between different structures range from 0 to 0.5 eV/unit cell. Although we have predicted that the ground state of WSSe is an S3 structure, the energy difference between the Janus structure and ground state is less than 0.1 eV/unit cell. Thus, it is still possible to synthesize these materials in Janus structures. The energy differences between the Janus structure and ground state in HfSSe and HfSeTe are also less than 0.1 eV/unit cell, which means that they can also be synthesized in experiments.

Spin dynamics of Janus and anti-Janus structure

After we obtained the ground state of different MXY compounds, we focused on their magnetic properties and calculated their electronic band structures. In Figs. S1-S11, all the electronic band structures are illustrated along the symmetry lines of the Brillouin zone (BZ). Ferromagnetism only exists in eight systems (e.g., CrSTe, CrSeTe, VSSe, VSTe, VSeTe, MnSSe, MnSTe, and MnSeTe). The electronic band structures of the magnetic system are illustrated in Figs. S1 and S2. The spin-up and spin-down bands are distinguished in different colors. It should be noted that the conduction band in these systems crosses the Fermi level, which indicates a clear metallic state. Moreover, the spin-up and spin-down bands of CrSeTe behave as conductors and inductors, respectively, which indicates that CrSeTe is a half-metal. The narrow gap between the valence band and conduction band in MnSSe indicates that MnSSe is a semimetal, as shown in Fig. S2d. The systems without magnetic field are illustrated in Figs. S3-S9. We also calculated the total and partial spin-polarized density of states (DOS) of the magnetic MXY, as shown in Fig. 5, which confirms that the magnetism of these structures mainly originates from the Mn-d, Cr-d and V-d orbitals. The ground states of all these magnetic structures are ferromagnetic order states, and the details are shown in Fig. S11.

Solid magnetic behavior is beneficial for skyrmions; thus, we only focused on magnetic systems. To explore the magnetic properties of these three structures, we calculated the parameters of the following Hamiltonian model, which describes the spins of magnetic atoms in the hexagonal structure:

where Si (Sj) is the unit vector representing the orientation of the spin of the i-th (j-th) site, and <i, j> refers to nearest-neighbor magnetic atom pairs. \({D}_{{ij}}\), \(J\) and \(K\) are the parameters for the DMI, Heisenberg exchange coupling and single-ion anisotropy, respectively. The last term is the Zeeman interaction, where \(\mu\) and \(B\) represent the magnetic moment of the magnetic atoms and the external magnetic field, respectively. Note that we have only considered the first nearest-neighboring interaction of the magnetic atomic pairs. According to Moriya’s symmetry rules4,5, the Dzyaloshinskii –Moriya vector can be written as \({{\boldsymbol{d}}}_{{ij}}={d}_{{||}}({\boldsymbol{z}}\times {{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{ij}})+{d}_{\perp }{\boldsymbol{z}}\), where \({\boldsymbol{z}}\) is the unit vector normal to the plane, and \({{\boldsymbol{u}}}_{{ij}}\) is the unit vector points from site i to site j. \({d}_{{||}}\) is the in-plane microscopic DMI component, and \({d}_{\perp }\) is the out-of-plane component. The contribution of \({d}_{\perp }\) to the Néel skyrmions is negligible; hence, we only evaluate the values of \({d}_{{||}}\). The DMI for one magnetic atom from the nearest six magnetic atoms is equal to \(\pm \frac{3}{2}{d}_{{||}}\) (the sign ± corresponds to the left-hand or right-hand spin-spiral configuration, as shown in Fig. 1a). For a 4 × 1 × 1 supercell with four magnetic atoms, we have \({E}_{L}-{E}_{R}=4\times \left[\frac{3}{2}{d}_{{||}}-\left(-\frac{3}{2}{d}_{{||}}\right)\right]\). The in-plane component can be derived as \({d}_{{||}}=\,\frac{{E}_{L}-{E}_{R}}{12}\)32. This spin spiral approach is effective for calculating the DMI in ferromagnetic/heavy-metal (FM/HM) heterostructures, such as Co/Pt32 and Fe/Ir(111)33 thin films, and B20-type chiral magnets, such as FeGe34. Its disadvantage lies in the fact that spin spiral calculations rely on the spiral state with collective spin rotations, and one must consider several spirals with different wavelengths to obtain the DMI beyond the nearest neighbors, which is often very cumbersome35. The specific method used to calculate J and K is described in the Supplemental Material.

In the present work, the results of the previous magnetic Janus systems are reproduced, as shown in Table 1, and the magnetic parameters of the corresponding lowest energy S2 and S3 are calculated, as shown in Table 2. Notably, MnSTe-S2 and MnSeTe-S2 still have strong DMI, and the magnitudes of the DMIs reach 4.86 and 4.21 meV, respectively, which are even greater than those of the Janus configuration. After confirming the stability of MnXY-S2 by their phonon spectrum (Fig. 6), we analyzed the contributions of different atoms to the spin–orbit coupling. The atomic-layer-resolved localization of the DMI associated SOC energy for Janus MnXY and MnXY-S2 are shown in Fig. 7. MnXY-S2 enhanced the contribution from Te atoms to spin–orbit coupling and led to a stronger DMI. The DMI values obtained in this work are comparable to those of many state-of-the-art FM/HM heterostructures with chiral spin textures, e.g., Co/Pt (∼3.0 meV)32 and Fe/Ir(111) (∼1.7 meV)33 thin films. Therefore, it is possible to realize chiral spin textures in MnXY-S2 monolayer structures.

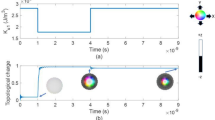

To further verify the aforementioned scenario, spin dynamics simulations based on the magnetic parameters extracted from DFT were performed for the MnXY-S2 case. For MnSTe-S2, our simulations reveal that the coexistence of helical domains and a small number of skyrmions occurs under zero magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 8a, demonstrating a rich spin texture. More importantly, we found that the application of an external magnetic field can induce a large number of skyrmions, as in many magnetic systems with skyrmions36,37,38. Applying a field shrinks the helical domains and causes the size and quantity of skyrmions to first peak and then decrease until the external magnetic field is large enough to annihilate the magnetic state into a single domain. Compared with that of the anti-Janus structure, the spin texture of the Janus MnSTe is relatively monotonous at zero field, and the critical magnetic field for the annihilation of skyrmions is relatively small, as shown in Fig. 8b. The skyrmions in Janus MnSTe almost disappear as the external magnetic field reaches 3 T, while in MnSTe-S2, skyrmions still exist even when the external magnetic field is as large as 10.0 T. A similar scenario can also be seen in MnSeTe, as shown in Fig. S10. The critical magnetic field of MnSeTe-S2 is above 5.0 T, and at the same time, a skyrmions bag phenomenon occurs at 0 T. Meanwhile, to verify that skyrmions are stable rather than metastable, we obtained the magnetic textures of MnSeTe through Monte Carlo simulations. As shown in Fig. S13, the results of both are almost identical, proving the stability of skyrmions. These results indicate that the ground states of MnSTe and MnSeTe are more suitable for spin-orbitronic devices under intense magnetic fields that rely on magnetic skyrmions than Janus MnSTe and MnSeTe.

Discussion

In summary, we present machine-learning-assisted high-throughput calculations to explore the ground-state configuration of MXY compounds and search for TMDs with strong DMIs. Not all configurations can be stabilized in the Janus layered configuration, and two anti-Janus structures (S2 and S3) can have a lower energy state. This result can be used to explain why 2D Janus TMDs materials are difficult to synthesize experimentally and to guide future works on synthetic TMDs. Next, we predicted 8 TMDs, and the comparison of the energies of different magnetic orders indicated that all of them had ferromagnetic metallic states. The DMI coefficients are obtained via first-principles calculations, and we find that the DMI in S2 is even larger than that in the Janus configuration. Spin dynamics simulations indicate that the anti-Janus structure has a richer spin texture in the absence of an external magnetic field, and skyrmions still exist under strong external magnetic fields. The present work provides an effective way to discover 2D magnets with strong DMI and suggests two anti-Janus ferromagnetic materials that are desirable for spin-orbitronic and memory devices.

Methods

First-principles calculations

All first-principles calculations were performed within the framework of spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)17,18. The electron-core interaction is described by the projected augmented wave (PAW) method39,40,41. The exchange correlation effects are treated with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)42. To address the strong on-site Coulomb interaction of 3d metals, we employed the GGA + U method in all calculations43. The U values were tested for all the compounds by comparing the resulting magnetic moment with those obtained by the Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE) hybrid functional43,44. For most of the cases, we find that U = 2.2 eV for Mn, U = 2.4 eV for Cr and U = 1.3 eV for V yield magnetic moments in good comparison with the HSE, details in Table S1-S3. Additionally, we also tested the band structure comparison with HSE, as shown in Fig. S14. The energy cutoff for plane wave expansion is set to 500 eV, and a Γ-centered 20 × 20 × 1 k-point mesh is adopted for Brillouin zone integration. All the structures are simulated by a slab model with a 20 Å vacuum layer. An energy convergence of 10−6 eV is used, and the structures are fully relaxed until the Hellmann–Feynman forces on all atoms are less than 10−3 eV/Å. In the subsequent calculations, 9 × 9 × 1 and 7 × 7 × 1 k-points are used for the 2 × 2 × 1 and 3 × 3 × 1 supercells, respectively.

Support vector regression

As a type of support vector machine (SVM), SVR was introduced by Corinna Cortes in 199545. The aim of SVR is to find a hyperplane that can minimize the total deviation between sample points and the hyperplane, and only the deviation of sample points out of the decision boundary is considered. The hyperplane in this work can be written as:

where \({\boldsymbol{x}}\) is the feature of our problem. In this work, we select the coordinates of the X or Y atoms in MXY as features, and \(f\left({\boldsymbol{x}}\right)\) is the energy of the structure. Our regression problem can be transformed into finding the minimum of:

where \(\left|\left|{\boldsymbol{\omega }}\right|\right|\) is the L2 norm of \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}\), \(C\) is the penalty coefficient, and \(l\) is the \(\epsilon\)-insensitive loss function, which can be written as:

After introducing slack variables \({\xi }_{i}\) and \({\hat{\xi }}_{i}\) to Eq. (3), it can be rewritten as:

s.t. \(f\left({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}\right)-{y}_{i}\le \epsilon +{\xi }_{i}\), \({y}_{i}-f\left({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}\right)\le \epsilon +{\hat{\xi }}_{i}\), \({\xi }_{i}\ge 0\), \({\hat{\xi }}_{i}\ge 0\).

To solve the objective function, we introduced Lagrange multiplier method. The Lagrange multiplier coefficients are \({\alpha }_{i}\), \({\hat{\alpha }}_{i}\), \({\mu }_{i}\), \({\hat{\mu }}_{i}\). The formula of Lagrange function can be written as:

The partial derivatives of Lagrange function to \({\boldsymbol{\omega }}{\boldsymbol{,}}\,b\), \({\xi }_{i}\) and \({\hat{\xi }}_{i}\) are zero, and we can have:

With the above equations, we can transfer the origin issue into a dual problem, and we can have:

In nonlinear problems, SVR applies a kernel function to map the nonlinear regression to a higher latitude space. The SVR regression equation can be written as:

where K is the kernel function, and Here, Gaussian kernel function \(K\left({x}_{i},{x}_{j}\right)=\exp \left(-\frac{{{||}{x}_{i}-{x}_{j}{||}}^{2}}{2{\sigma }^{2}}\right)\) is used.

Spin dynamic simulations

Using the magnetic parameters determined by first-principles calculations, we performed spin dynamics simulations using the VAMPIRE package to simulate the steady state and dynamics of the magnetization textures46. During the simulation, we use a 100 × 100 supercell with periodic boundary conditions, and the size of the supercell is large enough to eliminate finite-size effects. An external magnetic field is applied in the z-direction from 0 T to 10 T.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of the work is in the manuscript’s main text and Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The central codes used in this paper are VASP and VAMPIRE. Source code of machine learning used in this work can be achieved via: https://github.com/Jingtong-Zhang/SVR-code-for-MXY-materials.

References

Yu, X. Z. et al. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat Mater. 10, 106–109 (2011).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science. 323, 915–919 (2009).

Bogdanov, A. N. & Yablonskii, D. Thermodynamically stable “vortices” in magnetically ordered crystals. The mixed state of magnets. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 95, 178 (1989).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 4, 241–255 (1958).

Wang, L. et al. Ferroelectrically tunable magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin oxide heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 17, 1087–1094 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Robust formation of skyrmions and topological hall effect anomaly in epitaxial thin films of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 117202 (2013).

Gallagher, J. et al. Robust zero-field skyrmion formation in FeGe epitaxial thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 027201 (2017).

Yagmurcukardes, M. et al. Quantum properties and applications of 2D Janus crystals and their superlattices. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 011311 (2020).

Fukuda, M., Zhang, J., Lee, Y.-T. & Ozaki, T. A structure map for AB 2 type 2D materials using high-throughput DFT calculations. Mater. Adv. 2, 4392–4413 (2021).

Cui, Q. et al. Strain-tunable ferromagnetism and chiral spin textures in two-dimensional Janus chromium dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B. 102, 094425 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Very large Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in two-dimensional Janus manganese dichalcogenides and its application to realize skyrmion states. Phys. Rev. B. 101, 184401 (2020).

Yuan, J. et al. Intrinsic skyrmions in monolayer Janus magnets. Phys. Rev. B. 101, 094420 (2020).

Qi, S., Jiang, J. & Mi, W. Tunable valley polarization, magnetic anisotropy and Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in two-dimensional intrinsic ferromagnetic Janus 2H-VSeX (X = S, Te) monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 23597–23608 (2020).

Lu, A.-Y. et al. Janus monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 744–749 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Anomalous behavior of 2D Janus excitonic layers under extreme pressures. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002401 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp Mater Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Lourenço, M. P. et al. An adaptive design approach for defects distribution modeling in materials from first-principle calculations. J Mol Model. 26, 1–12 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. DeepTMC: A deep learning platform to targeted design doped transition metal compounds. Energy Stor. 45, 1201–1211 (2022).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Tao, Q., Xu, P., Li, M. & Lu, W. Machine learning for perovskite materials design and discovery. NPJ Comput. Mater. 7, 23 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 3564–3572 (2019).

Shi, W. & Wang, Z. Mechanical and electronic properties of Janus monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 30, 215301 (2018).

Han, Y.-t et al. Strain-tunable skyrmions in two-dimensional monolayer Janus magnets. Nanoscale. 15, 6830–6837 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Chemical welding on semimetallic TiS2 nanosheets for high-performance flexible n-type thermoelectric films. ACS Appl. Mater. 9, 42430–42437 (2017).

Rehman, S. U. et al. Computational insight of ZrS2/graphene heterobilayer as an efficient anode material. Appl. Surf. Sci. 551, 149304 (2021).

Wu, N. et al. Strain effect on the electronic properties of 1T-HfS2 monolayer. PHYSICA E. 93, 1–5 (2017).

Miao, N.-X., Lei, Y.-X., Zhou, J.-P. & Hassan, Q. U. Theoretical and experimental researches on NiS2 nanocubes with uniform reactive exposure facets. Mater. Chem. Phys. 207, 194–202 (2018).

Wang, Y., Li, Y. & Chen, Z. Not your familiar two dimensional transition metal disulfide: structural and electronic properties of the PdS 2 monolayer. J. Mater. 3, 9603–9608 (2015).

Lian, J.-C. et al. Algorithm for generating irreducible site-occupancy configurations. Phys. Rev. B. 102, 134209 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. Anatomy of dzyaloshinskii-moriya interaction at Co/Pt interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 267210 (2015).

Dupé, B., Hoffmann, M., Paillard, C. & Heinze, S. Tailoring magnetic skyrmions in ultra-thin transition metal films. Nat. Commun. 5, 4030 (2014).

Grytsiuk, S. et al. Ab initio analysis of magnetic properties of the prototype B20 chiral magnet FeGe. Phys. Rev. B. 100, 214406 (2019).

Yang, H., Liang, J. & Cui, Q. First-principles calculations for Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 43–61 (2023).

Boulle, O. et al. Room-temperature chiral magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 449–454 (2016).

Soumyanarayanan, A. et al. Tunable room-temperature magnetic skyrmions in Ir/Fe/Co/Pt multilayers. Nat. Mater. 16, 898–904 (2017).

Moreau-Luchaire, C. et al. Additive interfacial chiral interaction in multilayers for stabilization of small individual skyrmions at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 444–448 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B. 49, 14251 (1994).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Aryasetiawan, F. & Lichtenstein, A. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: the LDA+ U method. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 9, 767 (1997).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Evans, R. F. et al. Atomistic spin model simulations of magnetic nanomaterials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 26, 103202 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project (Grant No. 2022YFB3807601) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12302207, 12272338 and 12192214). Y.Z. acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 12102157) and computational support from the Center for Computational Science and Engineering of Lanzhou University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and Y.Z. conceived and supervised this project. P.H., J.Z., S.S. and Y.Z. carried out the calculation and analysis of the result. P.H. and J.Z. wrote the paper. P.H. and J.Z. are listed as co-first author. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41524_2024_1419_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Materials for Machine learning assisted screening of two dimensional chalcogenide ferromagnetic materials with Dzyaloshinskii Moriya interaction

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, P., Zhang, J., Shi, S. et al. Machine learning assisted screening of two dimensional chalcogenide ferromagnetic materials with Dzyaloshinskii Moriya interaction. npj Comput Mater 10, 232 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01419-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01419-y