Abstract

The physical/chemical properties undergo significant transformations in the different states arising from phase transition. However, due to the lack of a dynamic perspective, transitional mesophases are largely underexamined, constrained by the high resource burden of first principles. Here, using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations empowered by the machine-learning potential, we proffer an innovative paradigm for phase transition: regulating the thermal transport properties via the transitional mesophase triggered by a uniaxial force field. We investigate the mechanical, electrical, and thermal transport properties of the two-dimensional carbon allotrope of Janus-graphene with strain-engineered phase transition. Notably, we found that the transitional mesophase significantly suppresses the thermal conductivity and induces strong anisotropy near the phase transition point. Through machine-learning-driven MD simulations, we achieved high-precision atomic-level simulations of Janus-graphene. The results show that thermal vibration-induced intermediate amorphous or interfacial phases induce strong and anisotropic interfacial thermal resistance. The investigation not only endows us with a novel perspective on mesophases during phase transitions but also enhances our holistic comprehension of the evolution of material properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phonons represent the quantization of lattice vibrations, and their dynamics play a pivotal role in heat conduction. When a material is subjected to external fields, such as high temperature1,2, high pressure3,4, or mechanical strain5,6,7, these factors affect the interactions between atoms or molecules in the lattice, leading to changes in the crystal structure. In certain cases, these crystals can transition from one structural configuration to another, or even transform into an amorphous state, a phenomenon commonly referred to as a phase transition. Occasionally, an additional intermediate state or structure appears during the phase transition, known as the “transitional intermediate phase.” This intermediate phase refers to the structural state that exists under specific conditions when the system transitions from one phase to another. In this study, the “transitional intermediate phase” denotes the intermediate state or structure that arises during the phase transition between two different carbon monolayers, exhibiting some structural features similar to the system both before and after the phase transition. Throughout these complex transformations, the behavior of phonons, driven by thermal vibrations, can be profoundly influenced by factors such as lattice distortions, resulting in intricate and subtle characteristics. Despite extensive research in both theoretical and experimental domains5,8,9,10, many questions remain unresolved regarding the intricate interplay between phonons and phase transitions. This becomes particularly evident when considering the complex interactions generated by external force fields.

To investigate the phonon transport properties of materials, the standard approach predominantly relies on the first-principles method combined with the phonon Boltzmann transport equation (BTE, see Method for details)11,12,13. This approach holds a distinct advantage by obviating the need for experimental data or empirical parameters, rendering it particularly valuable when examining complex or less familiar materials. The crux of this approach lies in the utilization of interatomic force constants (IFCs), which encode crucial information pertaining to atomic interactions. Typically, these IFCs are derived from the material’s zero Kelvin (0 K) crystal structure via the finite-displacement-difference method14. The method involves introducing small displacements in the lattice and then calculating the corresponding energy changes, resulting in IFCs. This approach finds common implementation in open-source phonon BTE solvers such as ShengBTE14, Alamode15, and Phono3py16. However, this paradigm primarily hinges on the static 0 K crystal structure and fails to capture the dynamic structural transformations occurring at finite temperatures. Nonetheless, as the temperature rises, the atoms cease to remain in a static state and engage in more intricate dynamic interactions. This means that the phonon BTE method cannot accurately describe the complex atomic motion and changes in phonon properties during lattice phase transitions. Therefore, the method may be limited near phase transitions.

Compared to first-principles methods, molecular dynamics (MD) methods rely on Newton’s laws of motion and can simulate the motion trajectories of atoms and molecules over time. The computational cost of this method is relatively low, making it suitable for studying large-scale systems such as polymers17,18, magic angle systems19,20, and phase transitions21. It also offers unique advantages in simulating system evolution at finite temperature conditions. However, one of the challenges in MD simulations lies in the accuracy and reliability of the potential function. The potential function is used to mathematically describe the interactions between atoms, and its precision directly determines the accuracy of the simulation results. Traditional potential functions are often based on empirical parameterization, which leads to imprecise descriptions of complex molecular systems, and only qualitative results can be obtained. Fortunately, the rapid development of machine-learning technology in recent years has introduced a revolutionary approach to MD simulations, addressing this challenge. Machine learning technology enables researchers to construct highly accurate potential functions based on extensive first-principles calculated training data22, facilitating large-scale simulation research on complex systems. This method allows us to simulate intermolecular interactions more accurately, and describe complex phase transition phenomena quantitatively.

In this study, we developed a general neuroevolution potential using machine-learning techniques to explore the geometry, mechanical, electronic, and thermal properties of the novel 2D carbon allotrope that we proposed23, Janus-graphene, under uniaxial strain. Utilizing the machine-learning potential-empowered MD simulations, we propose an innovative paradigm for phase transition: regulating the thermal transport properties via the transitional mesophase triggered by a uniaxial force field. Our findings reveal that the crystal structure of Janus-graphene produces transitional intermediate phases before the static phase transition threshold due to finite temperature, which significantly suppresses thermal conductivity and enhances anisotropy. Our advanced machine-learning potential-driven MD simulations provide fresh insights into the thermal conduction behavior of systems undergoing phase transitions.

Results and discussion

Workflow for developing machine-learning potentials

In order to elucidate the physical mechanism, machine-learning techniques are used to develop machine-learning potential functions that can accurately describe the atomic interactions of Janus-graphene. As shown in Fig. 1a, the workflow for developing interatomic potential functions involves several key steps, including density functional theory (DFT), active learning, farthest-point sampling, and neural network techniques, and ultimately culminating in their application to MD simulation. The initial crystal structure of Janus-graphene was optimized using the conjugate gradient approach within the framework of DFT, allowing the desired structure to be produced at relatively low energy and confined states. Subsequently, a variety of initial structures were customized for the initial DFT sampling using strain, perturbation, bending, etc., providing an initial approximation of the potential function. This step is highly adaptable and can be tailored to suit specific simulation requirements. For broader applications, extended unified or universal potential functions24,25,26 are generally necessary to cover a wide range of scenarios and meet the generalization requirements, whereas rough potential functions may fall short in this regard. Here, extended MD simulations are conducted to cover various relevant application scenarios and generate new extrapolation structures that improve the generality of the underlying potential functions. To explore a sufficiently rich phase space while avoiding data redundancy, an active learning approach is implemented to screen the dataset, with an error threshold established to determine if the structure’s energy and force satisfy the precision. An extensive and all-encompassing dataset spans the range of applied MD simulations, allowing for the effective utilization of the machine-learning networks’ potential interpolation capabilities. However, redundant datasets will increase the difficulty of machine-learning latent network fitting in a large data network. Hence, we classify the data according to its characteristics and then select the distance from the latent space of the descriptor in the dataset to sample and filter the data, i.e., farthest-point sampling. Ultimately, the filtered dataset serves as the training set input for the machine-learning network to fit, thereby producing interatomic potential functions suitable for MD simulations.

a Workflow illustrating the development of machine-learning potential functions. b The number of configurations is obtained by different sampling methods, including pure AIMD, on-the-fly, and on-the-fly combined with the farthest-point sampling (FPS) method. c The convergence of loss function with respect to the number of training steps. d Root mean square error (RMSE) of energy in meV/atom, force in meV/Å, and virial force in meV/atom for the training set and the test set. Distribution of the e training set including 1925 configurations and f test set including 19,216 configurations based on principal component (PC) analysis technology, where PC1 and PC2 represent the two largest principal components. g Comparison of Phonon dispersions between the machine-learning potential (MLP) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

On-the-fly and farthest-point sampling

The machine-learning potential undergoes training using an extensive dataset derived from first-principles calculations. This training process enables it to replicate first-principles accuracy in MD simulations and to discern dynamic effects at finite temperatures. For constructing machine-learning potential, a complete dataset can ensure a reasonable phase space description and guarantee the accuracy of MD simulations, which means to judge whether it fully covers the actual application scenario of MD simulation. These datasets should ideally encompass a wide range of simulation scenarios. In our case, MD simulations were conducted under uniaxial and biaxial strains ranging from -2% to 25%. The simulations employed a Nosé-Hoover thermal bath controlled NVT ensemble, with strain intervals of 1% and temperature values at 50, 200, 350, 500, 650, and 800 K. Each temperature point was simulated for 10,000 steps, using a time step of 3 fs. However, the dataset generated after extensive simulations involving multiple strains and temperatures became unwieldy, consuming substantial computational resources. Consequently, we employed an on-the-fly model combined with active learning to screen the dataset. This approach utilized Bayesian algorithms to establish relationships between atomic positions and forces, and Bayesian error estimates to gauge prediction accuracy27,28. After estimating the prediction error, the current step could be dynamically assessed to determine whether it should be directly predicted by the machine-learning force field or computed by DFT through the defined error threshold. The supplementary Fig. S5 vividly shows the sampling situation during the simulation process taking 300 K as an example. The black one is estimated by the Bayesian method, and the red one is the final sampled structure calculated by DFT. As shown in Fig. 1b, without screening, pure ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) calculations would demand 28 × 6 × 2 × 10,000 = 3,360,000 DFT calculations using the same time and step size. In contrast, the on-the-fly mode reduced the requirement to just 19,216 DFT calculations. By adopting the on-the-fly mode, we ultimately obtained 19,216 DFT configurations, achieving a two-order-of-magnitude reduction in data calculations compared to pure AIMD.

Recognizing the potential for configurations to share similar relationships, we further refined the dataset by employing the farthest processing sampling strategy, utilizing the active learning package PYNEP from NEP29, which yielded a final training set comprising 1925 configurations. Farthest-point sampling is inspired by the work of Janet et al.30, and is based on the pre-trained neuroevolution potential model that uses distances d in the latent space to provide good quantitative uncertainty. In an \({N}_{{des}}\)-dimensional descriptor space, the distance d is measured by Euclidean distance, which can be expressed as:

where, \(P=\left({p}_{1},\,{p}_{2},\ldots ,{p}_{n}\right)\) and \(Q=\left({q}_{1},\,{q}_{2},\ldots ,{q}_{n}\right)\) represent the average descriptor vectors of two structures. The farthest-point sampling method effectively screened the data, alleviating the challenges associated with machine-learning fitting, and its effectiveness has been demonstrated in prior study31. Subsequently, the neural network was employed to fit the training set of 1925 frames using an evolutionary strategy, and the remaining data served as the test set for assessing the accuracy of the fitting. Figure 1c reveals the convergence relationship between the loss function and the number of evolution steps in the evolution process. After 105 steps, the loss functions for all phases obviously began to converge. The convergence result of 5 × 105 iterations was selected as the final potential function. Further, the fitting results of the machine-learning potential for the energy, force, and virial of both the training and test sets are extracted for comparison with the DFT results, as shown in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. S1a–f. The root means square errors (RMSE) of the energy, force, and virial for the test set are 26.60 meV/atom, 336.16 meV/Å and 78.48 meV/atom, respectively, which are nearly identical to the results for the training set (31.72 meV/atom, 283.30 meV/Å and 120.22 meV/atom), revealing good fitting results for atomic configurations outside of the training set. The energy RMSE of ~30 meV/atom and the force RMSE of ~300 meV/Å were found to be slightly larger. There are two reasons for the relatively large RMSE here: (1) Carbon atoms have very strong bonding ability and are very sensitive to force. Slight atomic perturbation will cause large forces, so the RMSE is larger than that of the general system. Similar large errors can still be found in other carbon potentials24[,32 since the RMSE error is relative. (2) Near the equilibrium state (such as 0 K after optimization), the force RMSE is almost zero, so the RMSE may vary by tens of meV. However, here, we are targeting complex working conditions, such as large strains and phase changes, which lead to large stress changes. Therefore, the size of RMSE is relatively large. For example, the RMSE of the neural network potential function trained by Li et al.33 for amorphous silicon (190 meV/A) is significantly higher than that of crystalline silicon (46 meV/A). Similarly, the RMSE of the empirical SW potential function for amorphous silicon (850 meV/A) is also significantly higher than that of crystalline silicon (200 meV/A).

Based on principal component (PC) analysis, the two largest and most important principal components are selected as PC1 and PC2 to further visualize the training set. As shown in Fig. 1e and f, the descriptor space of the training set is more evenly distributed than that of the test set, and their sample space ranges are almost the same. This means that the farthest-point sampling method ensures relatively uniform sampling of the sample space and reduces the redundancy of similar structures compared to the initial dataset. In addition, we calculated the phonon dispersion based on the screened structures and compared it with the DFT simulation to evaluate its accuracy. As shown in Fig. 1g, the phonon dispersion under machine-learning potential is in good agreement with the DFT fitting results, indicating that it can accurately describe the relevant physical properties.

Static phase transition properties

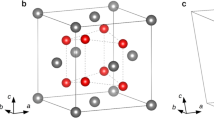

Intriguingly, by using a unified machine-learning potential, we discover unconventional geometric phase transitions in Janus-graphene induced by uniaxial force fields. Schematic diagrams of the atomic crystal transitions of Janus-graphene before and after phase transition under uniaxial strain can be found in Fig. 2a, where representative examples of 0% and 13% strain are used to depict the initial phase and final phase before and after the phase transition. Janus-graphene, as the initial phase, has an asymmetric buckled structure consisting of four-, six-, and eight-carbon-membered rings. When the buckled structure is subjected to a 10% uniaxial stress field, it flattens and undergoes a transformation into a planar carbon structure characterized by four-, five-, six-, and ten-carbon-membered rings, i.e., a two-dimensional carbon allotrope, as reported by Borlido et al. in ref. 34. Mechanically, this geometric phase transition results in a shift in the auxetic behavior from a negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) to a positive Poisson’s ratio (PPR). As shown in Fig. 2b, NPR behavior means that when the material is stretched, its lattice length in the orthogonal direction will expand, while PPR will shrink in the opposite direction. Earlier studies have demonstrated that the transition from NPR to PPR is confined to non-phase transition regions, arising from the inherent geometric strain response35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. This nascent manifestation of phase transition-induced Poisson’s ratio transformation introduces novel concepts and paradigms for the regulation of Poisson’s ratio.

a Schematic diagram of the uniaxial force field and transformation of atomic structure. Before and after 10% strain represent the initial and final phases, respectively. b Schematic diagram of the transition from negative (NPR) to positive (PPR) Poisson’s ratio behavior. Comparison of c strain, d Poisson’s ratio, and e stress at 0 K. f Bandgap evolution from semiconductor to semimetal due to strain-engineered phase transition. The transition of the electronic band structures g before and h after the phase transition.

The large contrast in Poisson’s ratio can be derived from the strain dependence before and after the phase transition, which is further determined by the lattice constant. Strain is usually defined as the change in the deformation of the crystal lattice relative to the initial state, and can be used to describe the deformation of the crystal. For a lattice with a lattice constant of L0, after applying a tensile or compressive stress in a certain direction, the lattice constant becomes L. Thus, the strain \(\varepsilon\) is

Further, Poisson’s ratio ν is defined as:

where \({{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) is the forced strain of the material along the force direction, and \({{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon }}}_{{\boldsymbol{y}}}\) is the responsive strain of the material perpendicular to the force direction. In Fig. 2c, “MLP with poisson” and “MLP without poisson” represent considering the Poisson effect and not considering the Poisson effect, respectively, which shows the impact of the Poisson effect on accuracy [More details can be found in Supplementary S1]. Intriguingly, a significant variation in the lattice constant before and after the phase transition becomes evident, as illustrated in Fig. 2c. In the initial phase, the carbon structure exhibits auxetic properties, where the response strain along the orthogonal direction increases with the application of uniaxial strain. In contrast, the final phase of the carbon structure displays contrasting non-auxetic properties, characterized by a decrease in response strain with increasing applied strain. Consequently, the initial Poisson’s ratio is negative, but following the phase transition, it undergoes an abrupt change, becoming positive, as depicted in Fig. 2d, thereby showcasing a switching effect. Due to this unique geometric rearrangement, the mechanical properties of the material change significantly. During this process, the planar conjugated bonds in the final phase strengthen the atomic bonding, resulting in a higher maximum resistive stress than the initial phase, as shown in Fig. 2e. Overall, it is found that the results of response strain, Poisson’s ratio and stress calculated by machine-learning potential are in good agreement with those calculated by the DFT method. The description of stress and strain by the empirical potential function usually has a large error, and may even have an opposite trend. The high consistency also shows the high accuracy of our fitted machine-learning potential.

Geometric phase transitions induce alterations in the electronic properties of Janus-graphene, as illustrated by the strain-dependent electronic structure presented in Fig. 2f. In the initial phase, the crystal structure exhibits a moderately wide energy bandgap where the valence band maximum (VBM) does not overlap with the conduction band minimum (CBM). With gradually increasing strain, the bandgap of the material also rises slightly. However, when the strain reaches 10%, a sudden electronic phase transition is observed: the VBM and CBM begin to overlap, displaying metallic properties. In-depth orbital evolution unveils the microscopic mechanism underlying this shift in electronic properties. As depicted in Fig. 2g, the VBM and CBM of the initial phase are predominantly populated by pz orbitals, resulting in an energy gap and demonstrating semiconductor characteristics with an indirect bandgap. Yet, following the phase transition, the pz orbitals of the VBM and CBM give rise to tilted anisotropic Dirac points along the high-symmetry point path S–Y, as shown in Fig. 2h. This restoration of planar conjugated π bonds leads to the creation of electron conduction channels, akin to graphene, and manifests semi-metallic properties. Consequently, the transformation from semiconducting to semi-metallic electrical characteristics is a consequence of orbital evolution driven by the phase transition. Notably, such changes in electrical characteristics are not confined to strain engineering control. Rather, the transformation observed in Janus-graphene primarily arises from alterations in the material’s atomic geometry, which affects the crystal structure and thus affects the band structure and orbital characteristics.

Dynamically suppressed thermal conductivity and the emerging anisotropy

The geometric and mechanical properties of machine-learning potential-driven MD align well with the results from DFT theory under static conditions. However, this alignment overlooks the kinetic effects present at finite temperatures, which lead to anomalous thermal transport properties. By solving the phonon BTE, the thermal conductivity changes gradually with strain until the phase transition threshold (10% strain) [Fig. 3a]. Interestingly, MD revealed abnormally suppressed heat transfer [Fig. 3b] and anisotropy reversal [Fig. 3c]. As shown in Fig. 3a, the average thermal conductivity in the orthogonal direction of Janus-graphene, as a function of strain, was computed using both the phonon BTE and equilibrium molecular dynamics (EMD, see Method for details) methods43,44. The κBTE/κMD ratio was employed to quantify the disparities in thermal conductivity between the phonon BTE method and the EMD method at room temperature. Remarkably, the thermal conductivities obtained through the EMD method at strain levels ranging from 5% to 10% are significantly lower than those derived from the phonon BTE method, with the lowest point observed at 7% strain.

a Strain-dependent normalized average thermal conductivity in different directions. b Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity and c anisotropy at 300 K for 0% and 7% strains. Thermal conductivity along d x and e y directions for 7% strain calculated by homogeneous non-equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations. “In-plane” (“out-of-plane”) refers to the thermal conductivity contributed by the vibration phonons in the direction parallel (perpendicular) to the x–y plane. “Total” refers to the sum of the thermal conductivity contributed by the “in-plane” and “out-of-plane” vibration phonons. Temperature distribution in non-equilibrium molecular dynamics along f x and g y directions for 7%. The bottom of sub-figures f and g are snapshots of the structure after molecular dynamics simulation, corresponding to the temperature distribution. The color represents the degree of deformation, with pure red and blue representing the configuration before and after the phase transition.

Furthermore, representative temperature-dependent thermal conductivities at 0% and 7% strain are extracted in Fig. 3b. More details about the calculation of EMD can be found in Supplementary Note S2 and Figs. S2–4. At 0% strain, thermal conductivities calculated by both the phonon BTE and EMD methods are isotropic, and the results obtained through both methods are in close agreement. At 300 K, the thermal conductivities along the x (y) direction, as calculated by the phonon BTE and EMD methods, are 121 (123) and 121 (124) W/mK, respectively. More details about the calculation of the phonon BTE method are found in Supplementary Notes S3 and Fig. S5. However, at 7% strain, the EMD results diverge significantly from the phonon BTE results. Specifically, the thermal conductivities along the x (y) directions, as computed by the phonon BTE and EMD methods, are 91.64 (104.58) and 60.54 (15.66) W/mK, respectively. Another noteworthy change is the anisotropic flipping observed in the results obtained through the EMD method at 7% strain, which contrasts with the findings of the phonon BTE method. Anisotropy of thermal conductivity is defined as the ratio of thermal conductivity along the y-axis to the x-axis. As depicted in Fig. 3c, at 300 K, the anisotropy derived from EMD simulations at 7% strain is 0.26, whereas the anisotropy obtained through the phonon BTE method is 1.14. This suggests that the EMD-based approach yields reversed anisotropy, with higher conductivity along the y-axis than the x-axis, indicating an opposing trend to the phonon BTE method.

Furthermore, the homogeneous non-equilibrium molecular dynamics (HNEMD, see the Method for details) method31 also captures this phenomenon, as depicted in Fig. 3d and e. At room temperature, the thermal conductivities computed using the HNEMD method are 61.19 ± 6.35 and 15.01 ± 1.44 W/mK for the x-axis and y-axis, respectively, which are closely aligned with the EMD results but remain considerably lower than those obtained through the phonon BTE method. Intriguingly, the significant anisotropy observed can be attributed to the interplay between out-of-plane and in-plane phonon vibrational modes. The in-plane phonon modes contribute significantly more to thermal conductivity along the x-axis than the out-of-plane phonon modes, whereas the out-of-plane phonon modes dominate along the y-axis.

Correspondingly, anisotropy can also be reflected in the non-equilibrium characteristics of the non-equilibrium molecular dynamics (NEMD, see Method for details) in different directions, as shown in Fig. 3f and g. A good energy conservation process can be found in Supplementary Fig. S6, revealing the stability of the NEMD simulations. Under the same temperature difference, they temperature difference distribution along the y-axis is more uneven, making it more difficult for heat flow to pass through. As shown in the right inset of Fig. 3f, the heat current along the y-axis is weaker than that along the x-axis under the same temperature difference, indicating a higher thermal resistance. Correspondingly, the anisotropy can also be reflected in the size effect from ballistic transport to diffusive transport based on the spectral heat current (SHC) method combined with NEMD and HNEMD methods, as shown in the left inset of Fig. 3f, where the thermal conductivity along the x-axis is higher than that along the y-axis.

Insights into transitional mesophases

Prior to reaching the phase transition point at 10%, the MD-based multi-method captures substantial differences and even opposing results when compared to the static phonon BTE results. These differences are manifested as markedly suppressed and anisotropic thermal conductivities. To elucidate this dynamic process, we employ the radial distribution function (RDF) under different strains to uncover information related to the material’s periodic structure, coordination number, molecular arrangement, and order/disorder state. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the RDF depicts the average distribution of atoms in relation to the center of the reference carbon atom within a specified distance. In the absence of strain, the uneven bond length distribution of C-C covalent bonds in the initial phase (Janus-graphene) results in prominent RDF peaks at radial distances of approximately 1.35 and 1.48 Å. However, as the strain exceeds 10%, the RDF becomes predominantly concentrated at radial distances of approximately 1.42 Å, signifying the transition to a planar carbon allotrope with a more uniform bond length distribution. Notably, a transitional RDF peak, displaying concurrent small-strain intensity and large-strain unimodal characteristics, emerges within the 5%–10% strain region preceding the phase transition point. This observation suggests that the structural and interaction characteristics of the material may undergo variations within the strain range preceding the phase transition point, leading to the tuning of geometric parameters, including interatomic distances and bond angles. Moreover, the dynamic process is further elucidated by changes in the MD and DFT potential, as depicted in Fig. 4b. DFT models posit that the phase transition abruptly occurs at the 10% strain point, resulting in a sudden drop in potential energy. However, the actual kinetic process reveals an intermediate transition state where potential energy asymptotically changes with the strain progression. In this transition state, the geometric structure of certain carbon atoms undergoes reorganization within the material, while other segments of the system adapt to internal stress to maintain their structural integrity. This phenomenon explains the presence of the transitional RDF peak. To further investigate whether the system has reached equilibrium, we performed longer dynamics simulations for a typical structure of 7%. Specifically, we performed a 200 ns dynamics simulation for a strain of 7% and plotted its potential energy versus time, as shown in Fig. S8. The results show that the energy remains very stable in the simulation, with no noticeable drift. This suggests that the system has reached equilibrium under these strain conditions.

a Radial distribution functions at different strains. b Variation of potential energy with strain. c Comparison of phonon dispersion at 0% and 13% strain. d Phonon vibrational density of states (VDOS) along z direction of states for 0%, 7%, and 13% strains. e Phonon participation rate for 0%, 7%, and 13% strains. f Frequency-dependent thermal conductivity at 0% and 7% strain. The insert is the mode-level thermal conductivities along the x- and y-axes at 7% strain. g Interfacial phases and thermal resistance model in the transitional mesophase.

The suppression of thermal conductivity during geometric rearrangement can be qualitatively explained through the phonon mismatch model45,46. As depicted in Fig. 4c, there is a notable frequency mismatch between the initial and final phases of the acoustic phonons, particularly at low frequencies. In the transition phase, the coexistence of the initial phase and the final phase configuration leads to irregularities inside the lattice, which affects the propagation of phonons. The vibrational phonon density of states reveals that this transitional phase’s irregularities cause a progressive reduction in the intensity of low-frequency phonon modes, while the intensity of high-frequency phonon modes gradually increases, as shown in Fig. 4d. When low-frequency phonons shift towards higher frequencies, the primary pathway for heat conduction may change, thereby impacting the material’s thermal conductivity. The pronounced lattice distortion within the transitional phase affects the lattice’s periodicity, leading to phonon scattering and localization, which is reflected in the phonon participation rate, as shown in Fig. 4e. At the transition stage (7% strain), the lower phonon participation rate means that the phonons are localized and contribute less to thermal conduction. Finally, the thermal conductivity contributing at low frequencies is significantly suppressed, as shown in Fig. 4f. We use a schematic diagram of the thermal resistance (similar to the concept of resistance) model to intuitively demonstrate this phenomenon. As shown in Fig. 4g, this interface morphology gives rise to three distinct contributions to thermal resistance: thermal resistance 1 (TR 1) from the initial phase, thermal resistance 2 (TR 2) from the final phase, and interface-like thermal resistance 3 (ITR 3). The results obtained from NEMD simulations illustrate the intuitive connection between these three thermal resistances, as shown in Fig. 3f and g, where the volumetric strain clouds reveal the interface-like morphology in the system, with dark red and blue atoms leaning towards the final and initial phases respectively. Furthermore, the temperature distribution under 7% strain exhibits strong anisotropy. The unevenly distributed interface phase is marked by the dotted line along the y-axis [Fig. 3g] leads to irregular temperature differences, inducing an obvious temperature jump when the x-axis temperature distribution is uniform [Fig. 3f]. Hence, the coupling between ITR 3, TR 1, and TR 2 in the transition phase leads to restricted heat conduction, thereby reducing the overall thermal conductivity. Note that the interface’s morphology exhibits a high degree of orientation due to the influence of uniaxial strain, resulting in a relatively uniform temperature distribution along the x-axis compared to the y-axis. This phenomenon signifies anisotropy in the thermal resistance distribution, offering an explanation for the thermal conductivity’s anisotropic behavior.

In summary, we harnessed machine-learning techniques to develop extended neuroevolution interatomic potential functions for strain engineering in a novel 2D carbon structure, Janus-graphene. Utilizing this potential function, we delved into the behavior of Janus-graphene under applied uniaxial strain, revealing an unconventional phase transition phenomenon. At 0 K and approximately 10% strain, the crystal structure underwent a phase transition, resulting in abrupt changes in static geometry, mechanical properties, and electronic structure. Additionally, the system’s mechanical strength significantly increased after the phase transformation, breaking the auxetic effect and transforming the semiconductor into a semimetal simultaneously.

To gain insights into this anomalous thermal transport behavior, advanced machine-learning potential-driven MD simulations captured the dynamic evolution process. We proffer an innovative paradigm for phase transition: regulating the thermal transport properties via the transitional mesophase triggered by a uniaxial force field. The formation of interfacial phases introduces coupling effects between different structural properties and dynamic behaviors, thereby introducing additional resistance to heat conduction. These groundbreaking insights shed light on thermal transport behavior and underscore the importance of dynamic effects in shaping material characteristics. Moreover, this study serves as a significant reference for the development and research of thermal management technologies in the realm of micro-nano scale heat transfer, offering inspiration for the design of novel materials and the optimization of their heat transfer properties.

Note that in recent years, many significant results have been obtained in experimental research on the growth of carbon materials. These studies can provide useful references for our work. For example, Toh et al. synthesized polycrystalline carbon monolayers in 202047. Fan et al. synthesized biphenylene in 202148. Hou et al. synthesized fullerene monolayers in 202249. These experimental results demonstrate the growth techniques and structural characteristics of different carbon monolayers, providing important background information for our theoretical research. In addition, Yang et al. recently demonstrated experimentally how to use inhomogeneous strain to explore the thermal conductivity of materials50. These research results not only provide us with an important experimental basis but also point out the direction for our theoretical research on carbon materials.

Methods

Density functional theory

The DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package51 (VASP) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional. The interaction between valance electrons and ion cores was described by the projector augmented wave52 (PAW) method. A vacuum layer of 20 Å was chosen to prevent the interlayer interactions. A kinetic energy cutoff of 1000 eV was used for the plane waves, and the energy and force were required to converge to 10-5 eV and 10-4 eV/Å, respectively. When constructing the train set, we used a supercell with a lattice constant of a = b = 16.45 Å (containing 108 atoms) as our initial modeling dataset. A Brillouin zone mesh of 3 × 3 × 1 was used to ensure energy sampling.

Phonon Boltzmann transport equation

By solving the phonon BTE, the thermal conductivity can be obtained as14,53:

where \({\tau }_{\lambda \alpha }\), \({C}_{\lambda }\), \({{\rm{\nu }}}_{\lambda \alpha }\), and \(V\) are the phonon relaxation time, specific heat capacity, group velocity for the \(\lambda\) mode phonon along the \(\alpha\) direction, and the crystal volume, respectively. The IFCs can be obtained from finite difference calculations based on Taylor expansion of the potential energy E:

where the coefficients \({\Phi }_{{ij}}^{\alpha \beta }\), \({\Phi }_{{ijk}}^{\alpha \beta \gamma }\), and \({\Phi }_{{ijkl}}^{\alpha \beta \gamma \delta }\) correspond to the second-order, third-order, and fourth-order force constants, respectively, and \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\), \(\delta\) and \(i\), \(j\), \(k\), \(l\) are direction and atom indices respectively. More details on the phonon BTE can be found in Supplementary Note S2 and some previous studies54,55.

Machine-learning potential

To accurately describe the interatomic interactions, we employed the state-of-the-art neuroevolution potential (NEP) approach30. The site energy of atom i is taken as a function of a descriptor vector with Ndes components,\({U}_{i}\left(q\right)={U}_{i}\left({\left\{{q}_{v}^{i}\right\}}_{v=1}^{{N}_{{des}}}\right)\). In NEP, a feed-forward neural network with a single hidden layer of Nneu neurons is used:

where w(0), w(1), b(0), and b(1) are the weight and bias parameters to be optimized during the training process. More details can be found in refs. 29,56.

Thermal conductivity from molecular dynamics

In the EMD method, the thermal conductivity can be calculated via the Green-Kubo formula43,44

where kB, V, and T are the Boltzmann constant, volume and temperature. The \(\left\langle {J}_{\alpha }({t}^{{\prime} }){J}_{\alpha }(0)\right\rangle\) represents the heat current autocorrelation function as a function of the correlation time \({t}^{{\prime} }\). For each system, we have performed 40 independent EMD runs, each with a production time of 1 ns.

In the HNEMD method, an external driving force (with a parameter Fe) is applied to drive the system out of equilibrium, and the thermal conductivity can be calculated as31:

where t, V, and T are, the time, the volume of the simulation box, and the temperature of the system, respectively. 〈J(t)〉is the average non-equilibrium heat current, \({F}_{e}=\) 0.0005 Å-1 is the driving force applied.

The frequency-dependent phonon properties can be obtained from the spectral thermal conductance G(\(\omega\)) in the ballistic regime and the spectral thermal conductivity \(\kappa\)(\(\omega\)) in the diffusive regime as calculated from NEMD and HNEMD simulations, respectively. For details, see Ref. 31. Then one can define the spectral phonon mean free path as \(\lambda \left(\omega \right)\) as

Based on the above spectral quantities, one can obtain the length-dependent spectral thermal conductivity via31

where L is the system length in the transport direction. All MD simulations were performed using graphics processing units molecular dynamics (GPUMD)57.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kasprzak, M. et al. High-temperature silicon thermal diode and switch. Nano Energy 78, 105261 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Wu, K. & Fu, Q. A structured phase change material with controllable thermoconductive highways enables unparalleled electricity via solar-thermal-electric conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109255 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Anomalous thermal transport under high pressure in boron arsenide. Nature 612, 7940 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Dong, Z.-Y., Hsieh, W.-P., Goncharov, A. F. & Chen, X.-J. Thermal conductivity of materials under pressure. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 5 (2022).

Liu, H., Qin, G., Lin, Y. & Hu, M. Disparate strain dependent thermal conductivity of two-dimensional penta-structures. Nano Lett. 16, 3831 (2016).

Parrish, K. D., Jain, A., Larkin, J. M., Saidi, W. A. & McGaughey, A. J. Origins of thermal conductivity changes in strained crystals. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235201 (2014).

Lindsay, L. et al. Phonon thermal transport in strained and unstrained graphene from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 89, 155426 (2014).

Yuan, K., Zhang, X., Tang, D. & Hu, M. Anomalous pressure effect on the thermal conductivity of ZnO, GaN, and AlN from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 98, 144303 (2018).

Zhang, F. et al. Atomic-scale observation of reversible thermally driven phase transformation in 2D In2Se3. ACS Nano 13, 8004 (2019).

Lu, Q. et al. Bi-directional tuning of thermal transport in SrCoOx with electrochemically induced phase transitions. Nat. Mater. 19, 6 (2020).

Ward, A. & Broido, D. A. Intrinsic phonon relaxation times from first-principles studies of the thermal conductivities of Si and Ge. Phys. Rev. B 81, 085205 (2010).

Omini, M. & Sparavigna, A. An iterative approach to the phonon Boltzmann equation in the theory of thermal conductivity. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 212, 101 (1995).

Ward, A., Broido, D. A., Stewart, D. A. & Deinzer, G. Ab initio theory of the lattice thermal conductivity in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 80, 125203 (2009).

Li, W., Carrete, J., Katcho, N. A. & Mingo, N. ShengBTE: a solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 1747 (2014).

Tadano, T., Gohda, Y. & Tsuneyuki, S. Anharmonic force constants extracted from first-principles molecular dynamics: applications to heat transfer simulations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 225402 (2014).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2023).

Barrat, J.-L., Baschnagel, J. & Lyulin, A. Molecular dynamics simulations of glassy polymers. Soft Matter 6, 3430 (2010).

Lin, F., Xiang, Y. & Shen, H.-S. Temperature dependent mechanical properties of graphene reinforced polymer nanocomposites—a molecular dynamics simulation. Compos. Part B: Eng. 111, 261 (2017).

Cheng, Y. et al. Magic angle in thermal conductivity of twisted bilayer graphene. Mater. Today Phys. 35, 101093 (2023).

Mandal, S., Maity, I., Das, A., Jain, M. & Maiti, P. K. Tunable lattice thermal conductivity of twisted bilayer MoS 2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 13860 (2022).

Shi, J. et al. Double-shock compression pathways from diamond to BC8 carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 146101 (2023).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Yu, L. et al. Janus graphene: a two-dimensional half-auxetic carbon allotrope with a nonchemical Janus configuration. Phys. Rev. B 109, L121402 (2024).

Rowe, P., Deringer, V. L., Gasparotto, P., Csányi, G. & Michaelides, A. An accurate and transferable machine learning potential for carbon. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 034702 (2020).

Li, M., Cao, G., Luo, Y., Sheng, C. & Liu, H. Predicting the lattice thermal conductivity of alloyed compounds from the perspective of configurational entropy. Npj Comput Mater. 8, 75 (2022).

Deringer, V. L., Caro, M. A. & Csányi, G. A general-purpose machine-learning force field for bulk and nanostructured phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 11, 5461 (2020).

Jinnouchi, R., Lahnsteiner, J., Karsai, F., Kresse, G. & Bokdam, M. Phase transitions of hybrid perovskites simulated by machine-learning force fields trained on the fly with Bayesian inference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 225701 (2019).

Cui, C. et al. On-the-fly machine learning potential accelerated accurate prediction of lattice thermal conductivity of metastable silicon crystals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 033803 (2023).

Fan, Z. et al. GPUMD: a package for constructing accurate machine-learned potentials and performing highly efficient atomistic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 114801 (2022).

Friederich, P. et al. Machine learning dihydrogen activation in the chemical space surrounding Vaska’s complex. Chem. Sci. 11, 4584 (2020).

Fan, Z., Dong, H., Harju, A. & Ala-Nissila, T. Homogeneous nonequilibrium molecular dynamics method for heat transport and spectral decomposition with many-body potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 064308 (2019).

Qian, C., McLean, B., Hedman, D. & Ding, F. A comprehensive assessment of empirical potentials for carbon materials. APL Mater. 9, 061102 (2021).

Li, R., Lee, E. & Luo, T. A unified deep neural network potential capable of predicting thermal conductivity of silicon in different phases. Mater. Today Phys. 12, 100181 (2020).

Borlido, P., Steigemann, C., Lathiotakis, N. N., Marques, M. A. L. & Botti, S. Structural prediction of two-dimensional materials under strain. 2D Mater. 4, 045009 (2017).

Yu, L., Qin, Z., Wang, H., Zheng, X. & Qin, G. Half-negative Poisson’s ratio in graphene+ with intrinsic Dirac nodal loop. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100790 (2022).

Yu, L. et al. Emerging negative Poisson’s ratio driven by strong intralayer interaction response in rectangular transition metal chalcogenides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 610, 155478 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. The consistent behavior of negative Poisson’s ratio with interlayer interactions. Mater. Adv. 3, 4334 (2022).

Yu, L., Yan, Q. & Ruzsinszky, A. Negative Poisson’s ratio in 1T-type crystalline two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 8, 15224 (2017).

Qin, Z., Qin, G. & Hu, M. Origin of anisotropic negative Poisson’s ratio in graphene. Nanoscale 10, 10365 (2018).

Qin, G. & Qin, Z. Negative Poisson’s ratio in two-dimensional honeycomb structures. Npj Comput Mater. 6, 51 (2020).

Pan, J. et al. Auxetic two-dimensional transition metal selenides and halides. Npj Comput Mater. 6, 154 (2020).

Jiang, J.-W. & Park, H. S. Negative Poisson’s ratio in single-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 5, 4727 (2014).

Kubo, R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570 (1957).

Green, M. S. Markoff random processes and the statistical mechanics of time‐dependent phenomena. ii. irreversible processes in fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 22, 398 (2004).

Song, Q. & Chen, G. Evaluation of the diffuse mismatch model for phonon scattering at disordered interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 104, 085310 (2021).

Lumpkin, M. E., Saslow, W. M. & Visscher, W. M. One-dimensional Kapitza conductance: Comparison of the phonon mismatch theory with computer experiments. Phys. Rev. B 17, 4295 (1978).

Toh, C.-T. et al. Synthesis and properties of free-standing monolayer amorphous carbon. Nature 577, 199 (2020).

Fan, Q. et al. Biphenylene network: a nonbenzenoid carbon allotrope. Science 372, 852 (2021).

Hou, L. et al. Synthesis of a monolayer fullerene network. Nature 606, 507 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Suppressed thermal transport in silicon nanoribbons by inhomogeneous strain. Nature 629, 1021 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab inito molecular dynamics for metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Han, Z., Yang, X., Li, W., Feng, T. & Ruan, X. FourPhonon: an extension module to ShengBTE for computing four-phonon scattering rates and thermal conductivity. Comput. Phys. Commun. 270, 108179 (2022).

Yu, L.-F. et al. Realizing ultra-low thermal conductivity by strong synergy of asymmetric geometry and electronic structure in boron nitride and arsenide. Rare Met 42, 210 (2023).

Wei, D.-H. et al. Insight into vertical piezoelectric characteristics regulated thermal transport in van der Waals two-dimensional materials. Rare Met. 43, 770 (2023).

Fan, Z. et al. Neuroevolution machine learning potentials: combining high accuracy and low cost in atomistic simulations and application to heat transport. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104309 (2021).

Fan, Z., Chen, W., Vierimaa, V. & Harju, A. Efficient molecular dynamics simulations with many-body potentials on graphics processing units. Comput. Phys. Commun. 218, 10 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52006057), National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFB2408100), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (No. CSTB2022NSCQ-MSX0332), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos. 531119200237), and the State Key Laboratory of Advanced Design and Manufacturing for Vehicle Body at Hunan University (Grant No. 52175013). This work is supported by Hunan Provincial Innovation Foundation for Postgraduate CX20240396. H.W. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51906097). Z.Q. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.12274374). The numerical calculations in this paper have been done on the supercomputing system of the E.T. Cluster and the National Supercomputing Center in Changsha. L.Y. is supported by Hunan Provincial Innovation Foundation For Postgraduates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Q. supervised the project. L.Y. performed all calculations, analyses, and writing. K.D. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Q.Y. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Y.Z. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Z.F. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. X.Z. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. H.W. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Z.Q. wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Dong, K., Yang, Q. et al. Dynamic mesophase transition induces anomalous suppressed and anisotropic phonon thermal transport. npj Comput Mater 10, 280 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01442-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01442-z

This article is cited by

-

Prediction of thermal conductivity in CALF-20 with first-principles accuracy via machine learning interatomic potentials

Communications Materials (2025)