Abstract

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) often neglect long-range interactions, such as electrostatic and dispersion forces. In this work, we introduce a straightforward and efficient method to account for long-range interactions by learning a hidden variable from local atomic descriptors and applying an Ewald summation to this variable. We demonstrate that in systems including charged and polar molecular dimers, bulk water, and water-vapor interface, standard short-ranged MLIPs can lead to unphysical predictions even when employing message passing. The long-range models effectively eliminate these artifacts, with only about twice the computational cost of short-range MLIPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) can learn from reference quantum mechanical calculations and then predict the energy and forces of atomic configurations quickly, allowing for a more accurate and comprehensive exploration of material and molecular properties at scale1,2. Most state-of-the-art MLIP methods use a short-range approximation: the effective potential energy surface experienced by one atom is determined by its atomic neighborhood. This approximation implies that the total energy is the sum of atomic contributions, which also makes the MLIPs scale linearly with system size.

The short-range MLIPs, however, neglect all kinds of long-range interactions, such as Coulomb and dispersion. Although short-range potentials may be sufficient to describe most properties of homogeneous bulk systems3, they may fail for liquid-vapor interfaces4, dielectric response5,6, dilute ionic solutions with Debye-Hückel screening, and interactions between gas phase molecules7.

There has been a continuous effort to incorporate long-range interactions into MLIPs. One can include empirical electrostatics and dispersion baseline corrections4,8,9, but for many systems, such baseline is not readily available. Another option is to predict effective partial charges to each atom, which are then used to calculate long-range electrostatics10,11,12,13,14,15. For example, the fourth-generation high-dimensional neural network potential (4G-HDNNPs)11 predicts the electronegativities of each nucleus and then use a charge equilibration scheme16 to assign the charges. 4G-HDNNPs are trained directly to reproduce atomic partial charges from reference quantum mechanical calculations, although partial charges are not physically observable and their values depend on the specific partitioning scheme used13. In a similar vein, the deep potential long-range (DPLR)17 learns maximally localized Wannier function centers (MLWFCs) for insulating systems, and the self-consistent field neural network (SCFNN)12 predicts the electronic response via the position of the MLWFCs. Message passing neural networks (MPNNs)18,19,20,21 employ a number of graph convolution layers to communicate information between atoms, thus capturing long-range interaction up to the local cutoff radius times the number of layers. However, if parts of the system are disconnected on the graph, e.g. two molecules with a distance beyond the cutoff, the message passing scheme does not help. Another class of methods is to learn the long-range descriptors and interactions in the reciprocal space with learnable frequency filters22,23. Finally, a very interesting approach is the long-distance equivariant (LODE) method7,24, which uses local descriptors to encode the Coulomb and other asymptotic decaying potentials (1/rp) around the atoms, and a related, density-based long-range descriptors25.

Here, we propose a simple method, the Latent Ewald Summation (LES), for accounting for long-range interactions of atomistic systems. The method is general and can be incorporated into most existing MLIP architectures, including potentials based on local atomic environments (e.g. HDNNP26, Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP)27, Moment Tensor Potentials (MTPs)28, atomic cluster expansion (ACE)29) and MPNN (e.g., NequIP19, MACE30). In the present work, we combine LES with Cartesian atomic cluster expansion (CACE) MLIP31. After describing the algorithm, we benchmark LES on selected molecular and material systems.

Results

Theory

For a periodic atomic system, the total potential energy is decomposed into a short-range and a long-range part, i.e. E = Esr + Elr. As is standard in most MLIPs, the short-range energy is summed over the atomic contribution of each atom i,

where Eθ is a multilayer perceptron with parameters θ that maps the invariant features (B) of an atom to its short-range atomic energy. B can be any invariant features used in different MLIP methods, including those based on local atomic environment descriptors such as ACE29, atom-centered symmetry functions26, smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP)32, or any latent invariant features in MPNNs.

For the long-range part, another multilayer perceptron with parameters ϕ maps the invariant features of each atom i to a hidden variable, i.e.

The structure factor S(k) of the hidden variable is defined as

where k = (2πnx/Lx, 2πny/Ly, 2πnz/Lz) is a reciprocal vector of the orthorhombic cell, and ri is the Cartesian coordinates of atom i. The long-range energy is then obtained using an Ewald summation form that best captures the electrostatic potential (1/r)33:

where σ is a smearing factor which we typically set to 1 Å with justifications in the Methods, k = ∣k∣ is the magnitude, and kc is the maximum cutoff. q can be multi-dimensional, in which case the total long-range energy is aggregated over contributions from different dimensions of q after the Ewald summation.

The LES method can be interpreted in two ways. First, the hidden variable q is analogous to the environmental-dependent partial charges on each atom. This implies that the method is at least as expressive as those explicitly based on learning partial atomic charges, as it would yield the same results if q replicated the partial charges. Additionally, q can be multidimensional, potentially enhancing expressiveness further. Unlike partial charges, q is not constrained by requirements such as charge neutrality or correct charge magnitudes. As the Ewald summation in Eq. (4) omits the k = 0 term, a non-zero net q does not cause energy divergence issues. Physically, this means the tinfoil boundary condition is applied. In addition, Eq. (4) omits the self-interaction term present in the regular Ewald summation for long-range charge interactions. This is because the Elr here does not need to correspond to a physical electrostatic potential, and the self-interaction term is short-ranged and can be included in the Esr components. The second interpretation of LES is as a mechanism that allows atoms far apart in the simulation box to communicate their local information. In this sense, LES is related to the recent Ewald-based long-range message passing method, which facilitates message exchange between atoms in reciprocal space23.

Example on molecular dimers

We benchmark the LES method on the binding curves between dimers of charged (C) and polar (P) molecules at various separations in a periodic cubic box with a 30 Å edge length. The dataset7, originally from the BioFragment Database34, includes energy and force information calculated using the HSE06 hybrid density functional theory (DFT) with a many-body dispersion correction. We selected one example from each of the three dimer classes (CC, CP, PP), derived from the combination of the three monomer categories. Figure 1 shows a snapshot of each example.

For each class, the upper panel shows a snapshot of the system with the charge states indicated, the middle panel shows the parity plot for the force components, and the lower panel shows the binding energy curve, which is the potential energy difference between the dimer, and two isolated and relaxed monomers. The root mean square errors (RMSE) for the energy and force components of the test sets are shown in the insets.

The goal of this benchmark is to evaluate whether the MLIP models can extrapolate dimer interactions at larger separations based on training data from smaller distances. For each molecular pair, the training set consists of 10 configurations with dimer separation distances between approximately 5 Å and 12 Å, and the test set includes 3 configurations with separations between approximately 12 Å and 15 Å.

For each molecular pair, we trained a short-range (SR) model using CACE with a cutoff rcut = 5 Å, 6 Bessel radial functions, c = 8, \({l}_{\max }=2\), \({\nu }_{\max }=2\), Nembedding = 3, and one message passing layer (T = 1). It should be noted that this setting of the “SR” model already achieves a perceptive field of 10 Å through the message passing layer, which is quite typical for current MPNNs. In comparison, more traditional MLIPs based on local atomic descriptors typically use a cutoff of around 5 or 6 Å, making them even more short-ranged.

In the long-range (LR) model, the short-range component Esr used the same CACE setup, while the long-range component Elr employed a 4-dimensional hidden variable computed from the same CACE B-features and utilized Ewald summation (Eq. (4)) with σ = 1 Å and a k-point cutoff of kc = 2π/3. It is important to fit both energy and forces for these datasets, as fitting only to a few energy values may result in models that accurately predict binding energy but perform poorly on forces.

Figure 1 shows that the LR MLIPs outperform the SR MLIPs in all cases. Furthermore, SR models fail to adequately capture the training data, as indicated by the flattening of the binding curves and the large discrepancies between some predicted and true forces (gray symbols in Fig. 1). The primary limitation of the SR models is that molecules separated by distances beyond the MLIP cutoff exist on independent atomic graphs, rendering the message-passing layers ineffective for communication between the dimers. Direct comparison of the accuracy of the present LR models with the LODE method [7] is challenging, as different training protocols were used in ref. [7], and LODE depends significantly on the choice of the potential exponent p for each dimer class. However, based solely on RMSE values, the LR models presented here appear to be more accurate. For example, in the CC class, the energy RMSE is 15.5 meV, compared to approximately 0.1 eV for LODE with the optimal choice of p.

Example on molten NaCl

Molten bulk sodium chloride (NaCl) presents non-negligible long-range electrostatic interactions. The dataset from ref. 25 contains 1014 structures (80% train and 20% validation) of 64 Na and 64 Cl atoms. Table 1 compares the root-mean-square percentage error (RMSPE) using different methods. rcut = 6 Å were used for all models except for the LODE flexible (7 Å). The CACE-LR models use 6 Bessel radial functions, c = 12, \({l}_{\max }=3\), \({\nu }_{\max }=3\), Nembedding = 3, zero (T = 0) or one message passing layer (T = 1), a 4-dimensional q, σ = 1 Å and a k-point cutoff of kc = 2π/3 in Ewald summation. The details for the other models are in ref. 25. We also trained hybrid models incorporating long-range electrostatics via element-dependent fixed charges on Na and Cl ions, with the remaining energy and forces fitted to short-ranged CACE T = 0 potentials. One model utilized nominal charges of 1e/-1e for Na/Cl ions, while another employed optimized fixed charges of 0.65e/−0.65e for Na/Cl ions.

Table 1 shows that the short-ranged models, including SOAP27,32,35, MACE30T = 0, and CACE T = 0 exhibit the highest errors. The simple baseline model using nominal fixed charges (CACE + fixed q = 1e) performs worse than the short-range models. However, after optimizing the fixed charge values through training, the CACE + fixed q=0.65e model demonstrates improved accuracy. Other long-ranged models, including LODE7,24 with different settings, a density-based long-range model25, and CACE-LR outperform the purely SR methods. MACE30 with message passing (T = 1), especially the one using equivariant features, also achieves accurate results, as message passing increases the effective perceptive field. Overall, CACE-LR models, with and without message passing (T = 0 and T = 1), obtain the best accuracy.

Example of bulk water

As an example application to dipolar fluids, we applied the LES method to a dataset of 1593 liquid water configurations, each containing 64 molecules36. The dataset was calculated using revPBE0-D3 DFT. For the CACE representation, we used a cutoff of rcut = 5.5 Å, 6 Bessel radial functions with c = 12, \({l}_{\max }=3\), \({\nu }_{\max }=3\), Nembedding = 3, and no message passing (T = 0) or one message passing layer (T = 1). For the long-range component, we used a 4-dimensional q, a maximum cutoff of kc = π, and σ = 1 Å in the Ewald summation.

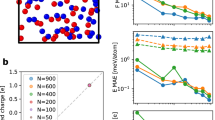

The learning curves in Fig. 2 demonstrate that message passing significantly improves the accuracy of MLIPs, consistent with previous studies19,30. The LR component further reduces the error for both models without a message-passing layer (T = 0) and with a message-passing layer (T = 1). The improvement is particularly notable in the T = 0 scenario. For the T = 1 models, the LR component results in a smaller reduction in errors, probably because the T = 1 SR models already capture atomic interactions up to 11 Å. Nevertheless, the T = 1 LR model demonstrates greater efficiency in learning with fewer data. We also compared the inference speeds of these models during molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, as detailed in the Methods section.

Learning curves of energy (E) and force (F) mean absolute errors (MAEs) on the bulk water dataset36, using short-range (SR) or long-range (LR) models and with or without massage passing layers (T = 0 or T = 1).

To investigate how message passing and long-range interactions affect predicted structural properties, we performed MD simulations of bulk water with a density of 1 g/mL at 300 K using each model. The upper panel of Fig. 3 shows the oxygen-oxygen (O-O) radial distribution function (RDF) computed with different MLIPs. All computed O-O RDFs are indistinguishable and in excellent agreement with the experimental results of the X-ray diffraction measurements37. This suggests that local representations are sufficient to accurately predict the RDFs of bulk liquid water, consistent with previous findings3.

The experimental O-O RDF at ambient conditions was obtained from ref. 37.

We then investigated the effect of long-range interactions on the dielectric properties of water by computing the longitudinal component of the dipole density correlation function6, \(\langle {\widetilde{m}}_{z}^{\star }(k){\widetilde{m}}_{z}(k)\rangle\), where \(\widetilde{m}\) is the Fourier transform of the molecular dipole density and k = kz is along the z-axis. The dipole correlation function at the long-wavelength limit can be used to determine the dielectric constant of water12.

As shown in Fig. 4, while the dipole density correlation functions predicted by different MLIPs are in excellent agreement for most values of k, discrepancies emerge at long wavelengths. Specifically, the results from short-ranged models sharply increase as k → 0. This divergence has also been observed in previous studies comparing the SR and LR models6,12. The divergence of the T = 0 short-ranged MLIP appears at a k value corresponding to a real length scale of approximately 11 Å, while the T = 1 SR model diverges at about 16 Å. Interestingly, these length scales, where divergence occurs, exceed the effective cutoff radius, suggesting that SR MLIPs may partially describe long-range effects beyond their cutoffs in a mean-field manner. When comparing the two SR MLIPs, the message passing layer delays the onset of divergence at small k values but does not eliminate it. In this scenario, only true LR models can adequately describe the dielectric response.

Example on interfacial water

It is widely recognized that short-range MLIPs fall short in describing interfaces4,12. To demonstrate the efficacy of the LES method for interfaces, we used a liquid-water interface dataset from ref. 4, computed with the revPBE-D3 functional. This data set contains approximately 17,500 training configurations, and was used to train a short-ranged DeePMD model17 combined with a long-range electrostatic baseline employing charges taken from an empirical water force field4. From these, we selected a small subset of 500 liquid-vapor interface configurations, each containing 522 water molecules.

We employed the same settings for fitting the MLIPs as used for the bulk water dataset. The learning curves for forces are shown in Fig. 5. The energy errors are very low, reaching less than 0.1 meV/atom in mean absolute error (MAE) for all models using only 50 training configurations. The force errors are also small, ranging from about 14 meV/Å to 27 meV/Å in MAE when trained on 90% of the dataset. The learning behavior is similar to that observed in the bulk water case: both message passing and long-range interactions enhance the accuracy of the MLIPs.

Learning curves on the liquid-vapor water interface dataset4 using the short-range (SR) and long-range (LR) models with no message passing (T = 0) or one message passing layers (T = 1).

For each of the T = 0 SR, T = 0 LR, T = 1 SR, and T = 1 LR models, we trained three MLIPs using different random splits of 90% for training and 10% for testing. We then simulated the liquid-vapor interface at 300 K using both a thinner slab (Fig. 6a) and a thicker slab of about double the thickness (Fig. 6d). The resulting density profiles of the water slabs are shown in Fig. 6b, e. All SR and LR models predict similar density profiles, and for the thinner slab, all models accurately reproduce the density profiles of the reference DFT water data.

a shows a snapshot of the thinner water slab configuration, b shows the water density profile, and c shows average cosine (c) the average \(\cos (\theta )\) for the angle formed by the water dipole moment and z-axis. DFT results are from ref. 4. d, e and f show the snapshot, the water density, and \(\langle \cos (\theta )\rangle\) for the thicker water slab, respectively.

In addition to density profiles, we evaluated the orientational order profiles, shown in Fig. 6c, f, by computing the angle, θ, between the dipole orientation of water molecules and the z-axis. For each model, the three different fits of MLIPs provide slightly different predictions, and the variances are larger for the SR models compared to the LR models. At the interfaces, water molecules tend to form a dipole layer, which is screened by subsequent layers, ensuring that the bulk does not exhibit net dipole moments4. However, without long-range interactions, this screening effect is not adequately captured, leading to extended dipole ordering into the bulk as seen in the T = 0 SR model. The introduction of message passing (T = 1 SR model) alleviates this issue at least for the thinner slab, but it also introduces an artifact: dipole ordering in the bulk along the opposite direction for the thicker slab. In contrast, on average and with smaller variance between different fits, the LR models recover the correct orientational order profiles, effectively capturing the screening effect and accurately representing the physical polarization behavior at the liquid-vapor interfaces.

Discussion

The current LES method can be extended in a number of ways. The form of the Ewald summation in Eq. (4) was selected to best capture the electrostatic potential (1/r), which dominates long-range interactions. It remains unclear what is the effect of not directly accounting for other decaying potentials. Different forms can be used to capture other decaying potentials 1/rp with different p components. For examples, to best capture the London dispersion (1/r6), one can use33,38.

where b2 = σ2k2/2, and \({\rm{erfc}}\) denotes the complimentary error function. Currently, the hidden variable q is a rotational invariant, and it may be extended to adopt a vector or tensor form to capture the dipole and multiple moments on an atom.

The relation between LES and the LODE method7,24 is worth exploring. The key difference is the ordering of local and global interactions. In LES, the hidden variable qi is determined by the local atomic environment-dependent features Bi of atom i, reflecting the nearsightedness principle: partial atomic charges depend mainly on local environments, similar to the short-range approximation in standard MLIPs. Although, it should be pointed out that such locality approximation remains empirical rather than systematic. These local q then interact globally via the Ewald summation to determine the global long-range energy. In contrast, in LODE7,24 the potential field (e.g. electrostatic potential and other 1/rp decaying potentials) generated by all the atoms in the system is calculated in the reciprocal space via Ewald summation, and such field near a central atom i up to some cutoff radius is then projected onto a set of basis functions to form the LODE descriptors. Finally, the short-range descriptors and the LODE descriptors of atom i are used to predict its energy. The density-based long-range descriptors25 are similar to LODE, but the global atomic density itself is used instead of the field. Comparing the formulisms of both, LES uses local descriptors to predict global long-range energy, while LODE uses global field to inform local descriptors. To the best of our knowledge, there is no straightforward mathematical connections between the LES and LODE formulisms, particularly considering the non-linearity introduced by the multilayer perceptron in LES that predicts qi from Bi (Eq. (2)). Physically speaking, LES encodes the long-range interation between a pair of far-away atoms via Gaussian smeared charges on the atoms. LODE is more flexible in the sense that the form of the interaction between the far-away atoms is not prescribed and is encoded in the long-range field descriptors to inform atomic energies. In principle, LES can be modified to be more similar with LODE: the LES hidden variable qi of an atom i can be concatenated with the local descriptors Bi used to predict its atomic energy, although we have not tested how such procedure would influence that accuracy.

LES also shares similarities with the recently proposed Ewald-based long-range message-passing method23, as both utilize structure factors. While LES directly determines the long-range energy from the structure factor of a hidden low-dimensional variable (Eq.(4)), the Ewald message-passing method23 employs a learnable frequency filter to map the structure factor of atomic descriptors to real space. This mapping generates a long-range message for each atom that is used to update atomic descriptors during the message-passing step. LES can thus be interpreted as a minimalist version of Ewald message-passing, with only one long-range message-passing layer, compressed message dimension, fixed frequency filter, and simplified readout. Such minimalist design makes the model light-weight and allows for easier physical interpretation.

In summary, we present a simple and general method, the Latent Ewald Summation (LES), for incorporating long-range interactions in atomistic systems. Unlike many existing LR methods, LES does not require user-defined electrostatic or dispersion baseline corrections4,8,9, does not rely on partial charges or Wannier centers during training10,11,12,13,14,15, and does not utilize charge equilibration schemes16. Moreover, LES shows best accuracy compared to other long-range methods and message passing neutral networks in the example on molten salt.

Our results demonstrate that the LR model effectively reproduces correct dimer binding curves for pairs of charged and polar molecules, long-range dipole correlations in liquid water, and dielectric screening at liquid-vapor interfaces. In contrast, standard short-ranged MLIPs, even when utilizing message passing, often yield unphysical predictions in these contexts. These challenges are common in atomistic simulations of molecules and materials, particularly in systems like water, which is ubiquitous in nature and essential to biological processes. Moreover, long-range effects are crucial in aqueous solutions, organic electrolytes, and other interfacial systems.

We anticipate that the LES method will be widely adopted in atomistic modeling: while many bulk material properties can be accurately modeled using short-ranged potentials, phenomena driven by electrostatic forces and dielectric responses may require explicit treatment of long-range interactions. In the example of water, while the SR and the LR models predict the same RDFs, they produce dramatically different dipole correlation functions. Meanwhile, the long-range MLIP incurs only a modest computational cost, roughly double that of the short-range version (see Methods). Furthermore, the LES method can be easily integrated into other MLIP frameworks, such as HDNNP26, ACE29, GAP27, MTPs28, DeePMD17, NequIP19, MACE30, etc.

Methods

Implementation

We implemented the LES method as an Ewald module in CACE, which is written using PyTorch. The code is available in https://github.com/BingqingCheng/cace. The current implementation of the Ewald summation should in principle, follow an overall scaling of \({\mathcal{O}}({N}^{3/2})\)39, with N being the number of atoms. The implementation of the code can be further optimized using algorithms with \({\mathcal{O}}(N\log (N))\) scaling employing techniques with the charges interpolated to a 3D grid such as the Particle-Particle Particle-Mesh method39. The MD simulations can be performed in the ASE package, but the LAMMPS interface implementation is currently absent.

Selection of the smearing factor σ

For a system of point charges, the Ewald summation expression in Eq. (4) implies that the long-range energy corresponds to the electrostatic energy of Gaussian distributed charges with σ being the standard deviation, while the short-range term needs to account for the difference between the Gaussian charges and the point charges. The value of the smearing factor σ needs to be a fraction of the real-space cutoff radius rrut in order to effectively eliminate the short-range error40. Meanwhile, a larger σ makes the Ewald series in k (Eq. (4)) more converged and avoids a high reciprocal space cutoff kc. and its optimal choice has been extensively discussed in the literature40. Combining these considerations, σ values in the rough range of 0.5 Å and 2 Å are reasonable choices. We tested the choice of σ on the bulk water dataset, with same settings as before and no message passing layer. Figure 7 shows that σ = 1 Å in this case leads to the lowest error, although the differences in outcome between various σ choices are quite small.

Energy (E) and force (F) mean absolute errors (MAEs) on the bulk water dataset36 with difference values of the smearing factor σ, using short-range models without massage passing.

Benchmark of inference speed

We benchmarked short- and long-range CACE water models with and without message passing for MD simulations of liquid water using a single Nvidia L40S GPU with 48 GB of memory. Figure 8 illustrates the time required per MD step. All models, with and without LR or message passing, exhibit favorable scaling. SR models support simulations with up to approximately 30,000 atoms on a single GPU, while LR models handle around 10,000 atoms due to the higher memory demands of the Ewald routine, which may still be optimized. LR models run at roughly half the speed of SR models. It may be sufficient to use a lower k-point cutoff in the LR model to further increase the speed.

MD of bulk water

For each MLIP, we performed NVT simulations of bulk water at 1 g/mL and 300 K to compute the RDF shown in Fig. 3. The simulation cell contained 512 water molecules, with a time step of 1 femtosecond, using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. The total simulation time was 300 ps.

To compute the longitudinal component of the dipole density correlation function for each model, we performed an NVT simulation of 2048 water molecules at 1 g/mL and 300 K in an elongated simulation box with a z-dimension of 99.3 Å. The simulation time for this system was 200 ps.

To compute the dipole density correlation functions, we calculated the dipole moment of each water molecule, assuming that hydrogen atoms and oxygen atoms have charges of + 0.4238e and − 0.8476e, respectively. This assumption only affects the absolute amplitude of the correlation function in Fig. 4, without altering the relative scale.

MD of water liquid-vapor interfaces

For the NVT simulations of the thinner slab at 300 K, we used a simulation cell with dimensions (25.6Å, 25.6Å, 65.0Å), containing 522 water molecules. The thicker slab system had dimensions (24.8Å, 24.8Å, 120.0Å), containing 1,024 water molecules. In both cases, the width of the water slab was less than half the total width of the cell. For the thinner slab, each independent NVT simulation lasted for about 400 ps. One run using T = 1 SR model became unstable after about 280 ps and we discarded the unstable portion. For the thicker slab, each run lasted for about 600 ps. One simulation using the T = 1 SR model became unstable after about 250 ps, and we only used the stable portion for the analysis.

Data availability

The training scripts, trained CACE potentials, and MD input files are available at https://github.com/BingqingCheng/cace-lr-fit.

Code availability

The CACE package is publicly available at https://github.com/BingqingCheng/cace.

References

Keith, J. A. et al. Combining machine learning and computational chemistry for predictive insights into chemical systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 9816–9872 (2021).

Unke, O. T. et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Yue, S. et al. When do short-range atomistic machine-learning models fall short? J. Chem. Phys. 154, 034111 (2021).

Niblett, S. P., Galib, M. & Limmer, D. T. Learning intermolecular forces at liquid–vapor interfaces, J. Chem. Phys. 155, (2021).

Rodgers, J. M. & Weeks, J. D. Interplay of local hydrogen-bonding and long-ranged dipolar forces in simulations of confined water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 19136–19141 (2008).

Cox, S. J. Dielectric response with short-ranged electrostatics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 19746–19752 (2020).

Huguenin-Dumittan, K. K., Loche, P., Haoran, N. & Ceriotti, M. Physics-inspired equivariant descriptors of nonbonded interactions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 9612–9618 (2023).

Lee, J. G., Pickard, C. J. & Cheng, B. High-pressure phase behaviors of titanium dioxide revealed by a δ-learning potential, J. Chem. Phys. 156, (2022).

Unke, O. T. et al. Spookynet: Learning force fields with electronic degrees of freedom and nonlocal effects. Nat. Commun. 12, 7273 (2021).

Unke, O. T. & Meuwly, M. Physnet: A neural network for predicting energies, forces, dipole moments, and partial charges. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 3678–3693 (2019).

Ko, TszWai, Finkler, J. A., Goedecker, S. & Behler, J. örg A fourth-generation high-dimensional neural network potential with accurate electrostatics including non-local charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 12, 398 (2021).

Gao, A. & Remsing, R. C. Self-consistent determination of long-range electrostatics in neural network potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 1572 (2022).

Sifain, A. E. et al. Discovering a transferable charge assignment model using machine learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 4495–4501 (2018).

Gong, S. et al. Bamboo: a predictive and transferable machine learning force field framework for liquid electrolyte development, arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07181 (2024)

Shaidu, Y., Pellegrini, F., Küçükbenli, E., Lot, R. & de Gironcoli, S. Incorporating long-range electrostatics in neural network potentials via variational charge equilibration from shortsighted ingredients. npj Computational Mater. 10, 47 (2024).

Rappe, A. K. & Goddard III, W. A. Charge equilibration for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. 95, 3358–3363 (1991).

Zhang, L. et al. A deep potential model with long-range electrostatic interactions, J. Chem. Phys. 156, (2022).

Schütt, K. et al. Schnet: A continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions, Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, (2017).

Batzner, S. et al. E (3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Deng, B. et al. Chgnet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Haghighatlari, M. et al. Newtonnet: A newtonian message passing network for deep learning of interatomic potentials and forces. Digit. Discov. 1, 333–343 (2022).

Yu, H., Hong, L., Chen, S., Gong, X. & Xiang, H. Capturing long-range interaction with reciprocal space neural network, arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.16684 (2022)

Kosmala, A., Gasteiger, J., Gao, N. & Günnemann, S. Ewald-based long-range message passing for molecular graphs, Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. pp. 17544–17563 (PMLR, 2023)

Grisafi, A. & Ceriotti, M. Incorporating long-range physics in atomic-scale machine learning, J. Chem. Phys. 151, (2019).

Faller, C., Kaltak, M. & Kresse, G. Density-based long-range electrostatic descriptors for machine learning force fields. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 21 (2024).

Behler, J. örg & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. ábor Gaussian approximation potentials: The accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: A class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multiscale Model. Simul. 14, 1153–1173 (2016).

Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G., Ortner, C. & Csányi, G. ábor Mace: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 11423–11436 (2022).

Cheng, B. Cartesian atomic cluster expansion for machine learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 157 (2024).

Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. ábor On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

Williams, D. E. Accelerated convergence of crystal-lattice potential sums. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A: Cryst. Phys., Diffr., Theor. Gen. Crystallogr. 27, 452–455 (1971).

Burns, L. A. et al. The biofragment database (BFDB): An open-data platform for computational chemistry analysis of noncovalent interactions, J. Chem. Phys. 147, (2017).

Jinnouchi, R., Karsai, F. & Kresse, G. On-the-fly machine learning force field generation: Application to melting points. Phys. Rev. B 100, 014105 (2019).

Cheng, B., Engel, E. A., Behler, J. örg, Dellago, C. & Ceriotti, M. Ab initio thermodynamics of liquid and solid water. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 1110–1115 (2019).

Skinner, L. B., Benmore, C. J., Neuefeind, J. C. & Parise, J. B. The structure of water around the compressibility minimum. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 214507 (2014).

Chen, Zhuo-Min, Çağin, T. & Goddard III, W. A. Fast ewald sums for general van der waals potentials. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1365–1370 (1997).

Toukmaji, A. Y. & Board Jr, J. A. Ewald summation techniques in perspective: a survey. Comput. Phys. Commun. 95, 73–92 (1996).

Kolafa, J. & Perram, J. W. Cutoff errors in the Ewald summation formulae for point charge systems. Mol. Simul. 9, 351–368 (1992).

Acknowledgements

B. C. thanks David Limmer for providing the water slab dataset, and Carolin Faller for the NaCl dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C. designed and performed the study, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no Competing Non-Financial Interests but the following Competing Financial Interests: B.C. has an equity stake in AIMATX Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, B. Latent Ewald summation for machine learning of long-range interactions. npj Comput Mater 11, 80 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01577-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01577-7

This article is cited by

-

Neural network potentials with effective charge separation for non-equilibrium dynamics of ionic solids: a ZnO case study

npj Computational Materials (2026)

-

Machine learning of charges and long-range interactions from energies and forces

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Machine learning and data-driven methods in computational surface and interface science

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Machine learning interatomic potential can infer electrical response

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

Deep-learning atomistic semi-empirical pseudopotential model for nanomaterials

npj Computational Materials (2025)