Abstract

The functionality of ferroelectrics is often constrained by their Curie temperature, above which depolarization occurs. Lithium (Li) is the only experimentally known substitute that can increase the Curie temperature in ferroelectric niobate-based perovskites, yet the mechanism remains unresolved. Here, the unique phenomenon in Li-substituted KNbO3 is investigated using first-principles density functional theory. Theoretical calculations show that Li substitution at the A-site of perovskite introduces compressive chemical pressure, reducing Nb–O hybridization and associated ferroelectric instability. However, the large off-center displacement of the Li cation compensates for this reduction and further enhances the soft polar mode, thereby raising the Curie temperature. In addition, the stability of the tetragonal phase over the orthorhombic phase is predicted upon Li substitution, which reasonably explains the experimental observation of a decreased orthorhombic-to-tetragonal phase transition temperature. Finally, a metastable anti-phase polar state in which the Li cation displaces oppositely to the Nb cation is revealed, which could also contribute to the variation of phase transition temperatures. These findings provide critical insights into the atomic-scale mechanisms governing Curie temperature enhancement in ferroelectrics and pave the way for designing advanced ferroelectric materials with improved thermal stability and functional performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectric materials are crucial for applications such as actuators, sensors, and memory devices1,2,3,4, each requiring distinct material properties. For instance, a high piezoelectric coefficient is required for actuators and sensors5,6,7, while stable, low-field switchable polarization is critical for non-volatile memory devices8,9. However, many of these properties are temperature-sensitive, with the Curie temperature (TC) being particularly important: above TC, ferroelectricity is lost due to depolarization, potentially leading to malfunctions. It is particularly challenging for high-temperature applications, such as sensors or actuators in nuclear reactors and oil drilling10, where stability of properties at elevated temperatures is critical11,12,13,14,15,16. Consequently, increasing TC has become a significant research focus in ferroelectrics.

The paraelectric-ferroelectric phase transition is often described by Landau’s phenomenological theory and soft-mode theory. Upon cooling down from the TC, the single-well Landau free energy curve becomes a double-well or triple-well curve, depending on whether it is a first-order or second-order phase transition, which is usually referred to as the ferroelectric instability in soft-mode theory17. The formation of spontaneous polarization is mainly due to the freezing (known as softening) of the relative displacement of cation and anion (known as optical mode) in ferroelectric perovskite at Γ point. Away from Γ point (e.g., M, R, or X), more complex polar structures may emerge, e.g., antiferroelectric and ferrielectric18,19. Intuitively, combining different cations and anions would result in different paraelectric-ferroelectric phase transition behavior, as the soft polar mode strongly depends on the interaction among these ions20,21. It has been explained based on the competition between the long-range dipole-dipole and short-range interaction22.

There are few existing experimental methods that can effectively raise TC in ferroelectrics, with one common strategy being to incorporate a perovskite with an inherently high TC into the matrix system, forming a solid solution. Li substitution in potassium sodium niobate (KNN) is a prime example of this approach, demonstrated by Saito et al. in 200423. It is worth mentioning that KNN has been highly recognized for its technological importance in the potential replacement of commercial lead-containing piezoelectric materials, i.e., lead zirconate titanate24. Li remains the only experimentally known substitute for increasing the TC of KNN25. Machado et al. discovered a similar effect in the molecular dynamics simulation of KNbO3 based on the shell model, noting a large off-center displacement of Li as a key factor in raising TC26, but without giving a deeper insight into the physical origin. Recently, Li et al. re-investigated the enhanced TC and hardening effect in Li-substituted sodium niobate induced by annealing at slightly below TC27, first reported by Kimura et al. in the early 2000s28,29. Despite these investigations, no existing physical model fully explains these behaviors.

In this work, we investigate the mechanisms behind the TC enhancement in Li-substituted KNbO3, as a representative system of KNN, utilizing first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Our study focuses on the energy variations caused by the interplay between A-site and B-site displacements and changes in the chemical environment due to Li substitution at the A-site. We then summarize the impact of Li substitution on TC from multiple perspectives, aiming to clarify the origins of the observed increase. Experimental characterizations of materials are also provided to validate the simulation results.

Results

Increased Curie temperature in Li-substituted KNbO3

The preparation of KNbO3 ceramics using conventional sintering methods is challenging due to limited densification and high sensitivity to moisture30. High porosity in sintered ceramics can often result in measurement artifacts and even electrical breakdown under low electric fields31. In this study, high-quality KNbO3 and Li-substituted KNbO3 (5 mol% of Li) ceramics were prepared using hot pressing. Figure 1 presents a comprehensive experimental comparison of these hot-pressed samples.

a XRD measurement at room temperature. The signal from the secondary phase is marked with asterisks (*). b SEM back-scattered electron (BSE) image of as-sintered Li-substituted KNbO3 sample. The scale bar is 5 μm. c Temperature-dependent relative permittivity measured at 10 kHz. d Raman spectra measured at room temperature. Symbols T, B, and S represent translational, bending, and stretching modes.

As revealed by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern in Fig. 1a, the KNbO3 sample exhibits a pure perovskite structure with an orthorhombic symmetry (Amm2)32 and no impurity phase is detected. The Li-substituted KNbO3 sample also possesses a similar orthorhombic crystal structure but is accompanied by a slight non-perovskite secondary phase. A quick peak fitting analysis performed on the perovskite 200 pc peak around 45° suggests that both samples have very similar lattice parameters, though Li-substituted KNbO3 seems slightly smaller (see Fig. S1 and Tables S1, S2). A similar trend can be found in Li-substituted (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 ceramic33.

The hot-pressed Li-substituted KNbO3 ceramics exhibit significantly low porosity compared to ceramics prepared via conventional sintering, as demonstrated in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image in Fig. 1b. The back-scattered electron (BSE) signal shows contrast among certain grains, which likely correspond to the secondary phase evidenced in the XRD pattern. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (see Fig. S2) indicates that the brighter regions in the BSE image are potassium-deficient. XRD and SEM analyses suggest that the solid solubility of Li in the KNbO3 matrix is limited, leading to the formation of the secondary phase. For reference, the solid solubility of Li in (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3 ceramic is close to 8 mol%33 and up to 12 mol% in NaNbO334, which seems slightly higher than KNbO3. The variation of solid solubility likely originates from the difference in chemical nature between the Li cation and original A-site cations, where a smaller difference allows a higher solubility.

Figure 1c shows the temperature-dependent relative permittivity of both samples, revealing two significant peaks at ~402 °C and ~215 °C. The first peak corresponds to the ferroelectric tetragonal-to-paraelectric cubic phase transition (TC) while the second peak corresponds to the ferroelectric orthorhombic-to-ferroelectric tetragonal phase transition (TO-T). Li substitution increases TC to ~440 °C, while TO-T decreases to 193 °C. The temperature-dependent dielectric loss can be found in Figure S3.

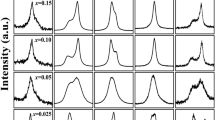

Figure 1d and S4 present the Raman spectra of both samples, showing significant overlap, which suggests a similar crystal structure and vibrational mode behavior. Based on the phonon spectrum of cubic KNbO3 (Fig. 2a), five Raman-active modes can be approximately identified at various wavenumbers. These include one stretching mode and three bending modes of the NbO6 octahedron, as well as one translational mode involving the relative motion of NbO6 against A-site atoms (K and Li) arranged from higher to lower wavenumbers. The peak coexistence in certain modes can be attributed to orthorhombic distortion in the crystal structure. Li substitution does not induce significant peak shifts of bending or stretching modes, indicating that the eigenvectors (representing atomic displacements) in these modes are largely unaffected. However, the spectral shape near the translational mode shows notable distortion, suggesting that NbO6 exhibits different translational motions against A-site atoms between the pure KNbO3 and Li-substituted KNbO3. Unfortunately, the strong background signal at low wavenumbers hinders further analysis. Additional characterization details for both samples are provided in the supplemental file (Fig. S5, S6).

Phonon spectra of pm-3m cubic phase (a) KNbO3 and b LiNbO3. Symbols P, AP, and Tri correspond to the polar mode, anti-phase polar mode, and trigonal mode, respectively. c Schematics of the displacement directions of ions in polar (P) and anti-phase polar (AP) modes in LiNbO3. Please note that the vectors do not reflect real displacement magnitude.

Ferroelectric instability and soft polar mode

From the phonon spectra of KNbO3 (denoted as KNO) shown in Fig. 2a, it is shown that there is an imaginary mode with a frequency of −7.05 THz at Γ point, which corresponds to the soft polar mode that causes the ferroelectric instability. In this polar mode, which is an optical mode, the K and Nb cations move in the direction opposite to the O anion. However, there are three imaginary modes at Γ point for LiNbO3 (denoted as LNO), i.e., −2.01, −4.62, −7.43 THz. Akin to KNbO3, the imaginary mode at −7.43 THz corresponds to the typical polar mode. Interestingly, the imaginary mode at −2.01 THz also corresponds to a polar mode, but the displacement vector of the Li cation becomes anti-phase to that of the Nb cation, herein denoted as anti-phase polar mode. The difference between the two modes is illustrated in Fig. 2c. Lastly, the imaginary mode at −4.62 THz should correspond to the structural instability leading to the experimentally observed ferroelectric phase in trigonal crystal structure35. The detailed eigendisplacements in each mode are in the supplemental file (Table S3–S6). Only the polar (and anti-polar) mode at Γ point is investigated herein because the four experimentally known phases, i.e., cubic Pm-3m, tetragonal P4mm, orthorhombic Amm2, and rhombohedral R3m, are barely associated with other high-symmetry points.

B-site driven ferroelectric instability

By constructing a 2x2x2 cubic pm-3m supercell, a certain number of K cations is homogenously replaced with Li cations to achieve different Li concentrations, including 0%, 12.5%, 50%, 87.5%, and 100%, named KNO, KLN125, KLN500, KLN875, and LNO, respectively (see Fig. S7 for atomic configurations). Although the Li concentrations modeled in our simulations exceed these experimental solid solubility limits, the qualitative trends revealed by the simulations remain relevant for understanding experimental observations.

To elucidate the ferroelectric behavior, it is essential to separately analyze the off-center displacements of the B-site and A-site cations, as they can contribute to ferroelectric instability in distinct ways. It is noted that the lithium substitution results in relaxed cubic structures with atoms slightly shifted from the high-symmetry positions, but the shift magnitude is tiny (see Table S7–S11). Therefore, these relaxed structures are still considered as the paraelectric phase. Figure 3 illustrates the energy variation associated with off-center displacements of B-site and A-site cations for structures with varying Li concentrations. In Fig. 3a, the energy variation of the polar mode by exclusively considering the off-center displacement of B-site cations is calculated. The resulting double-well energy profile indicates ferroelectric instability. As the Li concentration increases, the depth of the energy wells decreases, suggesting a reduction in ferroelectric instability.

a Energy variation as a function of the off-center displacement of the B-site cation in different compositions. b The energy variation as a function of the off-center displacement of the A-site cation with pre-fixed B-site cation displaced to ~0.1 Å in KLN125. P and AP correspond to polar and anti-phase polar modes, respectively.

According to Landau’s phenomenological theory, the simulated smaller energy difference between the saddle point (paraelectric phase) and the minimum point (ferroelectric phase) should lead to a lower TC, which intuitively appears contradictory to the experimental result. This apparent discrepancy highlights the need for further investigation into the compensating mechanisms that contribute to the experimentally observed increase in TC with Li substitution.

Compressive chemical pressure induced by Li

Ferroelectric instability is typically related to hybridization among cations and anions32, which can be analyzed through the Born effective charges (BEC)36. The BEC of all elements in different compositions are summarized in Table 1. In the KNO structure, the BECs of Nb and O ions deviate strongly from their nominal values of +5 and −2, respectively, highlighting strong hybridization. In contrast, the BECs of K and Li remain close to their nominal values of +1, indicating predominantly ionic behavior. Further details on this topic can be found in our previous work32. As the Li concentration increases, the slightly reduced BECs of Nb and O ions, reflecting a weaker Nb–O hybridization, can reasonably explain the observation of diminished ferroelectric instability in Fig. 2a.

Interestingly, the BECs of the K and Li cations remain nearly unchanged, suggesting that these cations do not directly influence the chemical bonding in these compositions. However, due to the smaller ionic radius of Li (1.13 ± 0.17 Å by extrapolation on existing data, see Table S12) compared to K (1.64 Å)37, Li substitution is expected to shrink the unit cell, generating compressive stress often referred to as chemical pressure38. The calculated unit cell volume as a function of Li concentration, summarized in Table 2, aligns well with this expectation and corroborates chemical intuition.

Inspired by this volume variation, we further examine the influence of the compressive chemical pressure induced by Li on BECs. Hydrostatic compression was applied to the unsubstituted KNO structure by manually changing the supercell size to mimic the chemical pressure, and the resulting BECs are presented in Table 3. Under increasing compressive stress, the BECs of Nb and O decrease slightly, whereas those of K remain nearly unchanged. This indicates that compressive stress can indeed influence the Nb–O hybridization, a finding consistent with experimental observations that applied compressive stress lowers TC39. Inferring from this, we believe that reduced ferroelectric instability driven by B-site atoms originates from the compressive chemical pressure induced by Li.

A-site driven ferroelectric instability

Phonon spectra comparisons between KNO and LNO reveal that the Li cation exhibits a substantially larger off-center displacement than the K cation (Fig. 2). To further explore this behavior, we simulated the off-center displacements of the A-site cations in the KLN125 structure while pre-fixing the Nb cations at an off-center displacement of ~0.1 Å with minimized energy. The results, shown in Fig. 3b, provide several notable insights.

First, the energy minimum for the K cation is near zero, indicating a limited tendency for off-center displacement. However, it shows a slightly positive value due to coupling with the off-center Nb cation. Second, the Li cation exhibits two distinct energy minima corresponding to enormous off-center displacements compared to K. On the positive side, a deep energy well of approximately 0.016 eV/f.u. is observed, while on the negative side, a shallower energy well of approximately 0.002 eV/f.u. is present. The coexistence of these minima can be related to two distinct polar modes in the phonon spectrum of LNO, occurring at −2.01 THz and −7.43 THz, respectively.

Impact on T C

Clarity emerges when the interplay between the A-site and B-site contributions is considered. This substantial off-center displacement of the Li cation not only compensates for the reduced energy depth observed in the B-site-cation-determined energy curve but also deepens the energy well further. In Fig. 4a, the energy differences between the paraelectric and ferroelectric phases across various compositions are calculated, revealing a nearly linear amplification with increased Li concentration. Figure 4b illustrates a schematic representation of the energy curve’s evolution with Li substitution. The pronounced off-center displacement of the Li cation deepens the overall energy well, thus requiring greater thermal energy for the system to transition from the ferroelectric phase to the paraelectric phase. Namely, the enhanced soft polar mode, which deepens the energy well, contributes directly to an increase in TC.

Notably, trigonal LNO exhibits an exceptionally high TC~1500 K40. The energy difference between the paraelectric and ferroelectric phases in LNO is calculated to be 520 meV/f.u., nearly nine times higher than that in KNO (58 meV/f.u.), which corresponds to an experimentally observed TC~700 K41. These findings demonstrate that examining the energy curve variations induced by chemical substitution provides a robust qualitative framework for predicting changes in TC. The near-linear relationship between energy difference and Li concentration also facilitates TC prediction for interpolated compositions, especially those within the solid solubility limit.

Impact on T O-T

Intriguingly, while the TC increases with Li substitution, TO-T decreases. Typically, phase transition temperatures follow a similar trend, as observed under externally applied pressure39. To understand this peculiarity, we analyzed the enhanced ferroelectric instability caused by the off-center displacement of the Li cation along polarization vectors corresponding to different phases: <001> for tetragonal, <011> for orthorhombic, and <111> for rhombohedral.

Figure 5 shows the energy variation as a function of the off-center displacement of the Li cation in cubic KLN125 along these directions. Notably, Li can displace significantly further along <001> (~0.9 Å) than along <011> and <111> (~0.6 Å), where the larger displacement also contributes to a deeper energy well. The result suggests Li substitution preferentially stabilizes the tetragonal phase over the orthorhombic and rhombohedral phases. Figure 5b1–b4 depict the environment of an A-site atom in a perovskite structure. While the B-site atom usually coordinates with 6 O anions, the A-site atom coordinates with 12 O anions. Thus, A-site usually has a larger space intrinsically. The smaller ionic radius of Li compared to K allows it to move further off-center, but its displacement is constrained along certain directions. For instance, Li can collide with the O anions at shorter distances along <011> and <111> directions. This behavior contrasts with pure KNbO3, where K remains near the center, contributing minimally to phase stability. The result suggests that the stabilization of the tetragonal phase over the orthorhombic phase is the main reason for the decreased TO-T upon Li substitution. It is also noted that the tetragonality increases with Li substitution, as shown in Table S13.

a Energy variation as a function of the off-center displacement of the Li cation in cubic KLN125 along different directions. b1 A schematic of the Li cation surrounded by the nearest O anions and K cations. Schematics of the Li cation displaced along b2 < 001>, b3 < 011>, and b4 < 111> directions. The displacement vector is referenced based on the displacements with the lowest energy shown in a and amplified 3 times for illustration. Some nearest atoms along the displacement are also displayed in these figures to guide the eye.

Analogous to PbTiO3, ferroelectric tetragonal phase is also energetically favorable. In this case, Pb exhibits a large off-center displacement in the tetragonal phase42, due to the strong hybridization between Pb and O43. In contrast, Ba in BaTiO3 exhibits a small off-center displacement, akin to K in KNbO342, allowing orthorhombic and rhombohedral phases to exist at lower temperatures44. We also noted that the interplay between A-site and B-site driven ferroelectricity was also investigated in the (Ba, Ca)(Ti, Zr)O3 ferroelectric solid solution45,46. Such evidence suggests that the displacement of the A-site cation is as crucial as that of the B-site cation in determining phase stability in ferroelectric perovskites.

Metastable anti-phase polar state

The anti-phase displacement between the Li and Nb cations is evident in the LNO phonon spectrum and also reflected in the double minima of the Li-displacement energy curve for KLN125 (Fig. 3b). The anti-phase polar mode in KLN125 was further relaxed under tetragonal symmetry, resulting in a higher-energy anti-phase polar structure (52 meV/f.u.) compared to the polar structure, as shown in Fig. 6a. It is hypothesized that the anti-phase polar structure may serve as an intermediate state between the polar and paraelectric structures.

a Relaxed configurations of paraelectric phase, ferroelectric phase with polar and anti-phase polar modes in KLN125. Transition path of the polarization switching between the ferroelectric phase with positive polarization and the ferroelectric phase with negative polarization (b) via paraelectric phase and c via anti-phase polar phase in KLN125.

To test this hypothesis, the polarization switching transition path via the paraelectric structure was calculated using the nudged elastic band method (Fig. 6b). The results show that an energy barrier of 284 meV/f.u. is required for polarization switching through the ideal paraelectric structure. Interestingly, two additional shoulders near the energy barrier suggest the existence of a previously unconsidered intermediate structure along the transition path. To explore this, the polarization switching path via the anti-phase polar structure was examined (Fig. 6c).

In the normalized transition path (0 to 0.5), a small energy barrier corresponds to the Li cation switching from positive to negative off-center displacement, while the other ions remain nearly fixed. From 0.5 to 1, the polarization switching is primarily driven by off-center displacements of the Nb and O ions. The maximum energy barrier for switching via the anti-phase polar structure is 226 meV/f.u., notably lower than the 284 meV/f.u. required for the transition through the paraelectric structure, indicating the anti-phase polar structure is energetically favorable as an intermediate state. The results also suggest that the anti-phase polar structure could exist near 180° domain walls where the polarization reversal occurs.

Although the anti-phase polar structure is metastable, it is suggested that it could be observed experimentally under certain conditions, e.g., located at domain walls stabilized by neighboring domains, applied electric field, or other specific thermodynamic conditions. However, its stability is highly sensitive to ambient thermal energy, as the reverse transition energy barrier from the anti-phase polar structure to the in-phase polar structure is only 17 meV/f.u., rendering it volatile under standard conditions. Stabilizing the anti-phase polar structure at room temperature could theoretically result in a lower TC.

Discussion

In summary, the impact of Li substitution on the enhanced TC in KNbO3 was investigated using DFT calculations and validated with experimental characterization. While the ferroelectric instability contributed by Nb–O hybridization diminishes with increasing Li concentration due to compressive chemical pressure, the pronounced off-center displacement of the Li cation compensates for this reduction. This displacement deepens the energy well, thereby reinforcing ferroelectric instability and leading to a predicted increase in TC in Li-substituted KNbO3. Additionally, the large displacement of the Li cation preferentially stabilizes the tetragonal phase over the orthorhombic phase, resulting in a decrease in TO-T. Another intriguing finding is the identification of a metastable anti-phase polar state in Li-substituted KNbO3. During polarization switching, the independent motion of the Li and Nb cations is energetically more favorable than their simultaneous displacement. Under specific conditions, this metastable anti-phase polar state could manifest, potentially changing TC. These results provide valuable insights into the fundamental mechanisms behind the increased TC in ferroelectric niobate-based perovskites, offering a clear framework for materials engineering and the design of high-performance ferroelectric materials for high-temperature applications.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of ceramic samples

The pure KNbO3 and Li-substituted KNbO3 (K0.95Li0.05NbO3) ceramic samples are prepared using hot pressing to ensure high density. K2CO3 (>99%, Sinopharm), Li2CO3 (>99%, Sinopharm), and Nb2O5 (>99.99%, Sinopharm) are used as the raw powders and ball-milled for 24 h before calcination at 930 °C for 4 h via the conventional solid-state reaction route. The calcined powder is hot-pressed for 2 h under a uniaxial pressure of 30 MPa at 920 °C. The hot-pressed sample is cut and polished, before annealing at 880 °C in the air atmosphere for 12 h.

The crystal structures of the final products are characterized using XRD with Cu Kα radiation (D/max2500, Rigaku) with a 2θ step of 0.02°. The Raman spectra are measured using Raman spectroscopy (HR800, HORIBA) with an excitation wavelength of 633 nm at 5 random spots in each ceramic sample to ensure consistency. The final spectra are averaged from all measurements and normalized according to the highest peak for qualitative comparison, where the original data can be found in the supplemental file. SEM (JSM-6460LV, JEOL) is used to characterize the morphology of sintered ceramics. The temperature-dependent dielectric properties are measured using an impedance analyzer (TH2827, Changzhou Tonghui Electronic Co). For this measurement, the samples are coated with silver paste and annealed at 600 °C for 30 min to form electrodes.

First-principles calculations

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculation is performed using VASP software. Generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhofer (PBE) exchange-correlation function is used. The valence electrons considered in four types of elements are 3s23p64s1 (K), 1s22s1 (Li), 4s24p65s14d4 (Nb), and 2s22p4 (O). Plane-wave cutoff energy is set to 500 eV. The convergence criteria for energy and force are set to 10–6eV and 0.005 eV/Å, respectively. Γ-center K-point meshes with a spacing of 0.12 Å-1 are created for all calculated structures.

The phonon spectra are calculated using the finite displacement method, and the non-analytical term correction is implemented using PHONOPY47. A 3x3x3 supercell is created for phonon calculation. The software automatically estimates band connection with 101 sampling points along each path. The born effective charges are calculated using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT). The compressive strain is introduced by fixing the unit cell parameters manually, where the resulting stress is read from the software calculation output. The transition paths are computed using the climbing nudged elastic band (c-NEB) method based on the VASP transition state theory (VTST) tool48. Visualization of atomic configurations in figures is achieved by using VESTA49.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhou, X. et al. Lead-free ferroelectrics with giant unipolar strain for high-precision actuators. Nat. Commun. 15, 6625 (2024).

Guo, J. et al. A freestanding ferroelectric thin film-based soft strain sensor. J. Materiomics 11, 100830 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Silicon‐compatible ferroelectric tunnel junctions with a SiO2/Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 composite barrier as low‐voltage and ultra‐high‐speed memristors. Adv. Mater. 36, 2211305 (2024).

Qi, H. et al. High-entropy ferroelectric materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 355–356 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. Low-field-driven large strain in lead zirconate titanium-based piezoceramics incorporating relaxor lead magnesium niobate for actuation. Nat. Commun. 15, 9024 (2024).

Qiu, C. et al. Transparent ferroelectric crystals with ultrahigh piezoelectricity. Nature 577, 350–354 (2020).

Go, S.-H. et al. 001]-texturing of (K, Na)NbO3-based piezoceramics with a pseudocubic structure and their application to piezoelectric devices. J. Materiomics 10, 632–642 (2024).

Hellenbrand, M., Teck, I. & MacManus-Driscoll, J. L. Progress of emerging non-volatile memory technologies in industry. MRS Commun. 14, 1–9 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. A stable rhombohedral phase in ferroelectric Hf(Zr)1+xO2 capacitor with ultralow coercive field. Science 381, 558–563 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Recent progress in bismuth-based high Curie temperature piezo-/ferroelectric perovskites for electromechanical transduction applications. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 26, 101016 (2022).

Dong, Y. et al. Review of BiScO3-PbTiO3 piezoelectric materials for high temperature applications: fundamental, progress, and perspective. Prog. Mater. Sci. 132, 101026 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Piezoelectric properties of BiFeO3 exposed to high temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2314807 (2024).

Hua, Y. et al. Broad temperature plateau for high piezoelectric coefficient by embedding PNRs in single‐phase KNN‐based ceramics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2414348 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Giant electric field‐induced strain with high temperature‐stability in textured KNN‐based piezoceramics for actuator applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214643 (2023).

Zheng, T. et al. Compositionally graded KNN‐based multilayer composite with excellent piezoelectric temperature stability. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109175 (2022).

Cen, Z. et al. Improving high-field strain and temperature stability on KNN-based ceramics sintered in reducing atmosphere via defect engineering. J. Materiomics 10, 1165–1175 (2024).

Dove M. T. Introduction to lattice dynamics: Cambridge University Press; (1993).

Yu, Z. et al. Room-temperature stabilizing strongly competing ferrielectric and antiferroelectric phases in PbZrO3 by strain-mediated phase separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 3438 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Finite-temperature properties of the antiferroelectric perovskite PbZrO3 from a deep-learning interatomic potential. Phys. Rev. B 110, 054109 (2024).

Ghosez, P. et al. Lattice dynamics of BaTiO3, PbTiO3, and PbZrO3: A comparative first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 60, 836–843 (1999).

Zhang, H. et al. Tuning the energy landscape of CaTiO3 into that of antiferroelectric PbZrO3. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140304 (2023).

Ghosez, P., Gonze, X. & Michenaud, J.-P. Coulomb interaction and ferroelectric instability of BaTiO3. Europhys. Lett. 33, 713–718 (1996).

Saito, Y. et al. Lead-free piezoceramics. Nature 432, 84–87 (2004).

Thong, H.-C. et al. Technology transfer of lead-free (K, Na)NbO3-based piezoelectric ceramics. Mater. Today 29, 37–48 (2019).

Li, J.-F. et al. (K, Na)NbO3‐based lead‐free piezoceramics: fundamental aspects, processing technologies, and remaining challenges. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96, 3677–3696 (2013).

Machado, R., Sepliarsky, M. & Stachiotti, M. Off-center impurities in a robust ferroelectric material: Case of Li in KNbO3. Phys. Rev. B 86, 094118 (2012).

Li, C.-B.-W. et al. Thermally induced domain reconfiguration in ferroelectric alkaline niobate. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2204421 (2022).

Kimura, M. et al. Piezoelectric properties of metastable (Li, Na)NbO3 ceramics. Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Symposium on Applications of Ferroelectrics ISAF 2002; 2002: IEEE, (2002).

Kimura, M. et al. Piezoelectric properties of alkaline niobate perovskite ceramics. Trans. Mater. Res. Soc. Jpn. 29, 1049 (2004).

Kakimoto, K.-i., Masuda, I. & Ohsato, H. Lead-free KNbO3 piezoceramics synthesized by pressure-less sintering. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25, 2719–2722 (2005).

Birol, H., Damjanovic, D. & Setter, N. Preparation and Characterization of KNbO3 Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 88, 1754–1759 (2005).

Thong, H.-C., Xu, B. & Wang, K. Distinctive Nb–O hybridization at domain walls in orthorhombic KNbO3 ferroelectric perovskite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 052902 (2022).

Guo, Y., Kakimoto, K.-i. & Ohsato, H. Phase transitional behavior and piezoelectric properties of (Na0.5K0.5)NbO3–LiNbO3 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 4121–4123 (2004).

Dixon, C. A. & Lightfoot, P. Complex octahedral tilt phases in the ferroelectric perovskite system LixNa1−xNbO3. Phys. Rev. B 97, 224105 (2018).

Gopalan, V., Dierolf, V. & Scrymgeour, D. A. Defect–domain wall interactions in trigonal ferroelectrics. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37, 449–489 (2007).

Ghosez, P., Michenaud, J.-P. & Gonze, X. Dynamical atomic charges: The case of ABO3 compounds. Phys. Rev. B 58, 6224–6240 (1998).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Found. Crystallogr. 32, 751–767 (1976).

Lin, K. et al. Chemical pressure in functional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 5351–5364 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Phase transition of potassium sodium niobate under high pressures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 012904 (2023).

Gopalan V., et al. Handbook of Advanced Electronic and Photonic Materials and Devices: Elsevier. p. 57–114; (2001)

Fontana, M. et al. Infrared spectroscopy in KNbO3 through the successive ferroelectric phase transitions. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 17, 483–514 (1984).

Warren, W. et al. Pb displacements in Pb(Zr, Ti)O3 perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 53, 3080–3087 (1996).

Kuroiwa, Y. et al. Evidence for Pb-O covalency in tetragonal PbTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 217601 (2001).

Zhang, J. et al. Structural phase transitions and dielectric properties of BaTiO3 from a second-principles method. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134117 (2023).

Amoroso, D., Cano, A. & Ghosez, P. First-principles study of (Ba, Ca)TiO3 and Ba(Ti, Zr)O3 solid solutions. Phys. Rev. B 97, 174108 (2018).

Amoroso, D., Cano, A. & Ghosez, P. Interplay between Ca- and Ti-driven ferroelectric distortions in (Ba, Ca)TiO3 solid solutions from first-principles calculations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 092902 (2019).

Togo, A. et al. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 35, 353001 (2023).

Sheppard, D. et al. A generalized solid-state nudged elastic band method. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 074103 (2012).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. W2433118) and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. IS24026). Fang-Zhou Yao appreciates the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U22A20254). Yan Wei appreciates the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82225012, 82430033). Shi-Dong Wang appreciates the support from Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Nos. JQ24049, L222066). We sincerely appreciate the insightful discussion with our colleague, Dr. Yi-Xuan Liu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. conducted first-principles analysis and was a primary contributor to the manuscript preparation. X.C. and Z.X. prepared the samples and carried out the experimental characterizations. F.Y., M.Z., H.Z., and B.X. contributed to the analysis of the investigation and provided valuable suggestions for improving the manuscript. Y.W. and S.W. oversaw funding acquisition, while KW supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thong, HC., Yao, FZ., Cai, XX. et al. Increased Curie temperature in lithium substituted ferroelectric niobate perovskite via soft polar mode enhancement. npj Comput Mater 11, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01584-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01584-8

This article is cited by

-

Beyond phase boundaries: atomic mechanisms governing structure and property variations in (K, Na)NbO3-based ferroelectrics

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Enhanced structural, dielectric, ferroelectric, and piezoelectric properties of lead-free (1-x) Bi0.5Na0.25K0.25TiO3–(x)LiSbO3 ceramics for next-generation piezoelectric applications

Emergent Materials (2025)