Abstract

The phase transition process in magnetic materials entails novel physical properties closely linked to electron distribution and energy states. However, the absence of an electron-scale calculation method for magnetic transition states hinders accurate description of electronic state changes. This paper presents a calculation method for magnetic phase transition string transition states, integrating excited state calculation with magnetic confinement. Using the ferromagnetic to antiferromagnetic phase transition in FeRh alloy as a case study, we demonstrate precise calculation of phase transition energy barrier and their influence on magnetic moment due to charge distribution. The method achieves high accuracy and reveals the interplay between lattice and magnetic coupling during magnetic phase transitions as well. This breakthrough not only sheds light on the fundamental mechanisms underlying magnetic phase transitions but also sets a precedent for future research in magnetic condensed matter physics, providing invaluable insights into the interplay between electron, lattice and magnetization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic materials frequently manifest multiple magnetic phases, wherein these distinct phases may interconvert under specific temperature or external physical fields. The phenomenon of magnetic phase transition holds considerable importance due to its broad spectrum of potential applications, including magnetic refrigeration1, which exploits such transitions to absorb or release heat, magnetic field sensors reliant on the magnetostrictive effect, and spin electronic devices2 that capitalize on the interplay between magnetic phase transitions and various physical fields. Given that the genesis of atomic magnetic moments stems from the distribution of electrons exhibiting diverse spin states, elucidating magnetic phases at the electronic scale assumes paramount significance in comprehending both the nature of magnetic phases and the processes governing phase transitions. Moreover, numerous non-trivial effects arising from electronic states in magnetic materials underscore the necessity of garnering electronic information pertaining to magnetic phases. With the density function theory, it is not difficult to perform first-principles calculations for complex magnetic states like spin spiral3 and skyrmion4,5. However, first-principles calculations elucidating magnetic phase transitions is still elusive up to now. Existing transition methodologies primarily operate at either the atomic scale or a mesoscopic scale delineated by micromagnetics, encompassing approaches such as the noncollinear extension of the Alexander-Anderson (NCAA) model6, the geodesic nudged elastic band (GNEB) method7, and other variations of the nudged elastic band (NEB) technique8,9,10.

The prevailing first-principle methodologies for scrutinizing phase transition processes predominantly cater to crystal structure transitions. These methodologies can be categorized into two principal classes: surface walking algorithms11,12,13 and interpolation algorithms14,15,16,17. Surface walking algorithms necessitate solely the final phase transition state as input to explore transition states, albeit their convergence performance tends to be suboptimal for multicomponent systems. Noteworthy surface walking methodologies encompass the gentlest ascent method18,19, the dimer method13,20, the optimization-based shrinking dimer (OSD) dynamics21, and so on. Compared to surface walking algorithms, interpolation algorithms exhibit greater robustness. The basic idea of interpolation algorithms involves the insertion of a series of intermediate states between the initial and final states of the phase transition, followed by iterative calculations of these intermediate states to achieve convergence. Notably, the NEB15,17 and the string method22,23,24 stand out as widely employed transition state calculation techniques within interpolation algorithms. Both approaches evolve the transition path based on the potential gradient. The primary distinction lies in NEB’s reliance on an additional parameter, k, to delineate the spring force linking states along the path, whereas the string method employs an intrinsic arc-length parameterization. Selecting an appropriate value for the spring force parameter k in NEB poses a nuanced challenge and can potentially impact the resultant transition path. In contrast to NEB, the string method offers a parameter-free parameterization and lends itself more readily to extension in situations when the energy landscape is rough. In the context of first-principle magnetic phase transition calculations, a natural inclination is to adapt the NEB or string method to magnetic systems. However, a significant impediment arises from the absence of precise calculations pertaining to magnetic excited states. Consequently, the gradient of potential essential for evolving the transition path in magnetic systems remains elusive.

The lacking of electronic scale transition state methods has become a constraint in the study of magnetic phase transitions. In response to this situation, combined with our inhouse magnetic constrained program which called DeltaSpin, we have developed a magnetic string method that can calculate magnetic transition states at the electronic scale. The basic idea is the same as the general string method, which is to make the phase transition path evolve along the gradient of the potential to find the minimum energy path. The key is how to obtain the potential energy surface of the magnetic system. The strategy we used is the first principle magnetic constrained calculation which is conducted by DeltaSpin. We demonstrate this method by taking the calculation of antiferromagnetism-ferromagnetism(AFM-FM) magnetic phase transition in FeRh alloy as an example. It has been found that FeRh alloy exhibits an AFM-FM phase transition at around 350K25,26 in experiments. Since the transition temperature is around room temperature and the phase transition can be triggered by multiple applied fields27,28, FeRh alloy stands out for the more promising applications comparing to other magnetic phase transition materials. It is also the reason why we choose FeRh as a platform to illustrate our magnetic phase transition method. The transition path and energy barrier of the magnetic phase transition of FeRh have been obtained. We further do an electronic structure and phonon calculation for magnetic transition states to analyze electronic and lattice dynamic contribution to this phase transition.

Results

Magnetic string method

The magnetic string method we developed is based on a assumption that the most possible phase transition path should be the minimum energy path between the initial and final states of the system. Suppose the magnetic potential energy of the system is V(x, m), and the phase transition path is γ = φ(x, m), where x = (x1, x2, . . . ) represents the coordinates of the atoms and m = (m1, m2, . . .) represents the magnetic moments of the atoms. According to the definition of minimum energy path, the phase transition path γ should satisfy the condition that the normal component along γ of the gradient of the potential energy is zero, as show in Eq. (1):

When Eq. (1) is not satisfied, the curve γ will continuously evolve under the drive of the potential energy at a velocity v(x, m) = − ∇ V(φ(x, m))⊥. It should be noted that the velocity of the curve evolution is always along the normal direction of the curve. That is because the tangential component of the velocity only moves points along the curve and does not influence the evolution of the curve itself. And then we can get the dynamic equation of curve evolution:

In the above discussion, the implicit assumption is that the system continuously changes from the initial state to the final state. But for magnetic phase transition, the transition states are some discrete states. In order to describe the distribution of the discrete states on the phase transition path, it is necessary to add a Lagrange multiplier term to the dynamic Eq. (2). The new curve evolution dynamics equation is:

where λ is a parameter, \(\hat{\tau }\) is the unit tangential component of the curve. As mentioned earlier, the tangential component of velocity does not affect the evolution of the curve. Therefore, the added Lagrange multiplier term only influences the distribution of transition states on the phase transition path and has no effect on the evolution of the phase transition path under potential energy. According Eq. (3), it is need to project the gradient of the potential energy function along the normal direction of the curve. However, the projection operation often reduces the accuracy of calculations. We introduce a transformation to avoid the projection, which transforms Eq. (3) to Eq. (4) using the relationship ∇ V(φ(x, m)) = ∇ V(φ(x, m))⊥ + ∇ V(φ(x, m))∥.

where \(\bar{\lambda }=\lambda +| \nabla V{(\varphi (x,m))}^{\parallel }|\) and ∇ V(φ(x, m))∥ represents the tangential component along γ of the gradient of the potential energy. The Eq. (4) is the final dynamic equation of curve evolution which we use in the calculation.

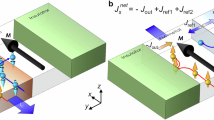

In the practical implements, the calculation of the magnetic transition path can be divided into three steps, which is shown in Fig. 123. First, we need to have a previous string, and in the first iteration it is generated randomly. In the second step, the previous string will be moved along the gradient of the potential which is shown in Eq. (4) to get the evolved string. In order to achieve the effect of evolution along the potential energy gradient, it needs to do two DFT calculations. One is a magnetic constrained calculation, the other is a special static calculation which performs only one or two electronic steps starting with the wave function obtained from the previous. The wave function of magnetic constrained calculation can represent the potential surface of the system, and the few electronic steps calculation is equivalent to evolve the system along the gradient of the potential. The medium images of the evolved string are usually not uniformed so that it will miss some information of the potential surface. To overcome this shortcut, the evolved string need be reparameterized in the final step. The reparameterization is also a requirement of the Lagrange multiplier term in Eq. (4). Since the Lagrange multiplier term is used to determine the distribution of medium images on the phase transition path, the effect is equivalent to reparameterization. The method we used to reparameterize the string is equal distance distribution. (The detail of reparameterization can be seen in the Method part). The reparameterized string will become the previous string in the next iteration. When the reparameterized string is the same as the last iteration, the loop will be terminated and the string obtained is the final phase transition path. In practical calculations, the convergence of the string is judged by the maximum energy difference between the corresponding magnetic configurations of the front and back loops. The convergence criterion is 5 × 10−3eV/atom in our calculation of transition states for FeRh.

a The evolution process of the string. The previous string is randomly generated in the first iteration with the fixed initial and final state. The evolved string is obtained by evolving the previous string under the gradient of potential. The reparameterized string is generated by redistributing media states in evolving string and will become the previous string in the next iteration; b The calculation flow of the magnetic string method. The detailed instruction is displayed in right box.

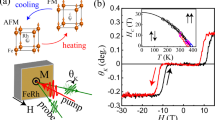

Magnetic transition states of FeRh

The AFM-FM magnetic phase transition states of FeRh have been calculated using the magnetic string method and DeltaSpin. Figure 2 shows the energy of transition states and corresponding magnetic configuration along the transition path. The images denote different magnetic transition states. Image No.1 is the initial AFM state, and image No.11 is the final FM state. The blue ball in the inner pictures denotes Fe atom, and the white is Rh atom. The red arrow denotes the magnetic moment localized on the atom. Our results clearly illustrate the evolution process of magnetic moment during the phase transition. For Fe atoms, there are two kinds of magnetic moment evolution. One is that the magnetic moments will deviate a small angle to the equilibrium position, and then go back in the final. It is opposite to the intuition that the magnetic moment will contain the same direction during the phase transition since the initial and final state for these Fe atoms is totally the same as each other. The other kind of magnetic moment evolution is the direction will completely flip, but the magnitude will maintain around the same value during the transition. For Rh atoms, the magnetic moments will gradually increase during the transition, and rotate to the direction paralleling with Fe atoms in the final state. According to Fig. 2, the energy barrier of the phase transition is ΔE = 0.035 eV/atom. Using the relationship E = kBT, we can estimate the corresponding transition temperature Ttransition = 406.16K, which matches reasonably with the experimental results \({T}_{transition}^{exp}=340-370K\)25,26. As mentioned above, the initial path(the previous string in the first iteration) is generated randomly. In order to check the influence of the initial path on the results, two independent initial paths have been generated. The results of the another initial path are very similar to the previous, including the evolution of the magnetic moments and the energy barrier which is \(\Delta {E}^{{\prime} }=0.033eV/atom\)(the corresponding transition temperature \({T}_{transition}^{{\prime} }=382.95K\)).

The images denote different magnetic transition states. Image No.1 is the initial AFM state, and image No.11 is the final FM state. Insert pictures demonstrate the magnetic configuration of different transition states. The blue ball denotes Fe atom, and the white is Rh atom. The red arrow denotes the magnetic moment localized on the atom. The energy barrier (which is calculated using image No.1 and image No.9) is ΔE = 0.035 eV/atom.

Electronic structure of transition states

Figure 3 shows the differential charge density between the magnetic transition states during the AFM-FM phase transition of FeRh. The differential charge density here refers to the difference of charge density between the same system but in different states. According to the results, the electrons of Rh atoms in axis directions will decrease during the transition, but that in diagonal direction will increase. Combining with the orientation of the orbital of d electrons, we can know that the electrons in eg orbital of Rh atoms will decrease, while the electrons in t2g orbital will increase. Since the net magnetic moment in the Rh atom emerges during the phase transition, it corresponds to a low-spin to high-spin (LS-HS)29 transition. Therefore, we can say that the charge transfer from eg to t2g is associated with the LS-HS transition. This phenomena can also be found in other alloy materials30. In addition to the direction of charge transfer, the change trend of the magnitude of charge transfer can also be obtained from Fig. 3c–f. From image No.5 to image No.8, the magnitude of charge transfer between adjacent images becomes larger and larger. However, from image No.8 to image No.9, the magnitude of charge transfer declines sharply, especially for Rh atoms, of which the charge density remains basically unchanged. Since the image No.8 and image No.9 are similar to the final state in energy level and magnetic structure, both states can be characterized by HS state. And the result of Fig. 3f can be understood that the charge transfer from eg to t2g is very small between the two HS states.

Phonon of transition states

We have calculated the phonon spectra for different magnetic transition states during the AFM-FM phase transition, as shown in Fig. 4. There exists imaginary frequency at X point for AFM (image No.1) state, which is consistent with the earlier theoretical calculations31. The imaginary frequency at X point will disappear during the phase transition, and a similar increase in phonon frequency can also be found at K and U point. All these results show that the acoustic phonon of the lowest energy becomes hardening during the phase transition. Given that this acoustic mode corresponds to an isotropic vibration, it suggests that the FM state exhibits a significantly greater preference for isotropic vibrations than the AFM state. This outcome is quite intuitive. In the FM state, all iron atoms are equivalent to one another(the same applies to rhodium atoms) in terms of both lattice structure and magnetic properties. While for the optical modes, the situation becomes more complex. There is no evident trend of change during the phase transition. A more detailed analysis is reserved for future research. It should be noted that for G point, the imaginary frequency emerges in image No.9 but disappears in FM (image No.11) state. It can be understood that the image No.9 is the highest energy state along the transition path.

Discussion

Before concluding our study, we briefly highlight two limitations of our magnetic string method. First, since the magnetic constrained calculations become very challenging when inducing ionic relaxation, the lattice change is not yet considered in our method. As a result, the method is not suitable for the magnetic phase transition accompanied by obvious lattice distortions. The second limitation is inherited from DFT calculation. Because current DFT can not describe strongly correlated electron systems reasonably, the magnetic phase transition of strongly correlated electron systems is excluded from our method.

However, even having some limitations mentioned above, the magnetic string method shows remarkable superiority to the current magnetic phase transition methods, such as magnetic NEB and NCAA model. Most of the current magnetic NEB methods are based on atomic scale molecular dynamics simulations with Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equations as the dynamic equations, which are completely lacking the electronic scale information. Our magnetic string method is based on DFT magnetic constrained calculations, which can give detailed electronic scale information of the phase transition path. This is the mainly superiority of the magnetic string method over the traditional magnetic NEB. NCAA is a model Hamiltonian method, which is parameter dependent and rely on the accuracy of the model to construct Hamiltonian. The magnetic string method requires only the magnetic configurations of the initial and final states of the phase transition, with no other adjustable parameters that have an impact on the results. And constructing Hamiltonian artificially is avoided, since our method is based on the first principle calculations.

To summarize, we have developed a magnetic string method that can calculate magnetic transition states at the electronic scale. Using the AFM-FM phase transition in FeRh alloy as a case study, we demonstrate a precise calculation of phase transition energy barrier and their influence on magnetic moment due to charge distribution. This method will be a powerful tool to investigate the interplay between electron and magnetization in materials, and we expect it to shed light on the fundamental mechanisms underlying magnetic phase transitions.

Methods

Reparameterization in magnetic string method

The method we used to reparameterize the string is equal distance distribution. The detailed process is as follows. First, the distance between the medium images and the initial state is calculated. The distance is defined by the length of a functional curve \(r=\frac{\theta }{\beta }(b-a)+a\), where a, b are the magnitudes of the magnetic moments of the initial and final states, β is the angle between the magnetic moments of the initial and final states, and θ is the angle between the magnetic moments of the medium images and the initial state. Then, taking the distances as the independent variable and the corresponding magnetic configurations of medium images as the dependent variable, a one-dimensional function is obtained using the usual interpolation algorithm (such as Python’s iterp1d() function). Finally, using equally spaced distances as input to the interpolation function obtained above, the output magnetic configuration is the reparameterized string.

Density functional calculations

All calculations in this work are first principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT)32,33,34. Under the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), DFT can provide a reasonable description for many systems. When the studied system contains transition metal elements, due to the strong Coulombic interaction between d or f electrons, the GGA+U35 method often provides a more accurate description of the system. The U represents the on site Coulomb interaction, which is an approximation of the strong Coulomb interaction between electrons. However, according to the results of ref. 36, the GGA+U method may cause the instability of the like face centered cubic structure, which is a metastable state of FeRh found in experiments. Therefore, the GGA+U method is not suitable for the FeRh system, and we have not used it in our calculations.

The program used for the first principles calculations is Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)32,33,34. The magnetic constrained DFT calculations have been performed using the self-adaptive spin-constraining algorithm DeltaSpin37, which has been implemented as a loadable module for VASP. The magnetic constrained calculations in DeltaSpin is achieved by optimizing the Lagrange term in the Hamiltonian. By adding the optimization of the Lagrange multiplier λ to the electronic step loop of the ordinary DFT calculation, it is able to adaptively find the optimal λ to achieve more accurate convergence to the target magnetic moment. The root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the obtained and target magnetic moments is used to evaluate the convergence of the magnetic constrained calculation in DeltaSpin. For common magnetic materials, the RMSE can be up to 10−5μB ~ 10−4μB. In our calculation, the RMSE is around 10−4μB. More detailed instructions of DeltaSpin algorithm can be found in ref. 37.

All calculations use the GGA exchange correlation functions with the PBE (the parameterization of Perdew, Burke, and Enzerhof) pseudopotential38. The interactions between ions and electrons are described using the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method39,40. The energy cutoff of the plane wave basis vector is 550 eV. The convergence criterion for electronic steps is 10−4 eV. For the magnetic phase transition calculation, a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell is used, and the Brillouin zone is sampled using the Monkhorst Pack k-point mesh of a 4 × 4 × 4 grid. It should be noted that the small volume change during the transition has not been taken into account.

Phonon calculations

The phonon spectrum of transition states are computed using the finite difference method implemented in the PHONOPY code41,42. In order to distinguish the magnetic structure of different transition states, the unitcell uses a 4 atoms fcc-like structure. A 3 × 3 × 3 supercell is used to calculate the harmonic and force constants.

Data availability

All the relevant data discussed in the present paper are available from the authors on request. Spin-constrained calculations were conducted with the DeltaSpin code (https://github.com/caizefeng/DeltaSpin).

References

Franco, V., Blázquez, J., Ingale, B. & Conde, A. The magnetocaloric effect and magnetic refrigeration near room temperature: materials and models. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 42, 305–342 (2012).

Marti, X. et al. Room-temperature antiferromagnetic memory resistor. Nat. Mater. 13, 367–374 (2014).

Yoshida, Y. et al. Conical spin-spiral state in an ultrathin film driven by higher-order spin interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 087205 (2012).

Kitchaev, D. A., Schueller, E. C. & Van der Ven, A. Mapping Skyrmion stability in uniaxial lacunar spinel magnets from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 101, 054409 (2020).

Haldar, S., von Malottki, S., Meyer, S., Bessarab, P. F. & Heinze, S. First-principles prediction of sub-10-nm skyrmions in pd/fe bilayers on rh(111). Phys. Rev. B 98, 060413 (2018).

Bessarab, P. F., Uzdin, V. M. & Jónsson, H. Calculations of magnetic states and minimum energy paths of transitions using a noncollinear extension of the Alexander-Anderson model and a magnetic force theorem. Phys. Rev. B 89, 214424 (2014).

Bessarab, P. F., Uzdin, V. M. & Jónsson, H. Method for finding mechanism and activation energy of magnetic transitions, applied to skyrmion and antivortex annihilation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 196, 335–347 (2015).

Dittrich, R. et al. A path method for finding energy barriers and minimum energy paths in complex micromagnetic systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 250, 12–19 (2002).

Paz, E., Garcia-Sanchez, F. & Chubykalo-Fesenko, O. Numerical evaluation of energy barriers in nano-sized magnetic elements with lagrange multiplier technique. Phys. B Condens. Matter 403, 330–333 (2008).

Thiaville, A., García, J. M., Dittrich, R., Miltat, J. & Schrefl, T. Micromagnetic study of Bloch-point-mediated vortex core reversal. Phys. Rev. B 67, 094410 (2003).

Cerjan, C. J. & Miller, W. H. On finding transition states. J. Chem. Phys. 75, 2800–2806 (1981).

Banerjee, A., Adams, N., Simons, J. & Shepard, R. Search for stationary points on surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 89, 52–57 (1985).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. A dimer method for finding saddle points on high dimensional potential surfaces using only first derivatives. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 7010–7022 (1999).

Elber, R. & Karplus, M. A method for determining reaction paths in large molecules: application to myoglobin. Chem. Phys. Lett. 139, 375–380 (1987).

Mills, G. & Jónsson, H. Quantum and thermal effects in h2 dissociative adsorption: evaluation of free energy barriers in multidimensional quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 1124–1127 (1994).

Ayala, P. Y. & Schlegel, H. B. A combined method for determining reaction paths, minima, and transition state geometries. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 375–384 (1997).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Crippen, G. & Scheraga, H. Minimization of polypeptide energy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 144, 462–466 (1971).

E, W. & Zhou, X. The gentlest ascent dynamics. Nonlinearity 24, 1831–1842 (2011).

Olsen, R. A., Kroes, G. J., Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. Comparison of methods for finding saddle points without knowledge of the final states. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 9776–9792 (2004).

Zhang, L., Du, Q. & Zheng, Z. Optimization-based shrinking dimer method for finding transition states. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 38, A528–A544 (2016).

E, W., Ren, W. & Vanden-Eijnden, E. String method for the study of rare events. Phys. Rev. B 66, 052301 (2002).

Peters, B., Heyden, A., Bell, A. T. & Chakraborty, A. A growing string method for determining transition states: comparison to the nudged elastic band and string methods. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 7877–7886 (2004).

E, W., Ren, W. & Vanden-Eijnden, E. Simplified and improved string method for computing the minimum energy paths in barrier-crossing events. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 164103 (2007).

Annaorazov, M. et al. Alloys of the ferh system as a new class of working material for magnetic refrigerators. Cryogenics 32, 867–872 (1992).

Shirane, G., Nathans, R. & Chen, C. W. Magnetic moments and unpaired spin densities in the Fe-Rh alloys. Phys. Rev. 134, A1547–A1553 (1964).

Feng, Z., Yan, H. & Liu, Z. Electric-field control of magnetic order: from FeRh to topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 5, p1–p14 (2018).

Ju, G. et al. Ultrafast generation of ferromagnetic order via a laser-induced phase transformation in FeRh thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 197403 (2004).

Weiss, R. J. The origin of the ‘invar’ effect. Proc. Phys. Soc. 82, 281–288 (1963).

Entel, P., Hoffmann, E., Mohn, P., Schwarz, K. & Moruzzi, V. L. First-principles calculations of the instability leading to the invar effect. Phys. Rev. B 47, 8706–8720 (1993).

Belov, M. P., Syzdykova, A. B. & Abrikosov, I. A. Temperature-dependent lattice dynamics of antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic phases of ferh. Phys. Rev. B 101, 134303 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and mott insulators: Hubbarduinstead of stoneri. Phys. Rev. B 44, 943–954 (1991).

Aschauer, U., Braddell, R., Brechbühl, S. A., Derlet, P. M. & Spaldin, N. A. Strain-induced structural instability in FeRh. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014109 (2016).

Cai, Z., Wang, K., Xu, Y., Wei, S.-H. & Xu, B. A self-adaptive first-principles approach for magnetic excited states. Quantum Front. 2, p1–p9 (2023).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 35, 353001 (2023).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, p1–p21 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51790494 and 12088101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.X. conceived and instructed the research. Under the guidance of B.X., W.T. and Y.L. developed the magnetic string method, and W.T. performed the theoretical calculations and data analysis. W.T. and B.X. wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, W., Li, Y. & Xu, B. Simulating magnetic transition states via string method in first principle calculation. npj Comput Mater 11, 130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01603-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01603-8