Abstract

Carbon materials especially with hydrogenation have attracted wide attention for their novel physical and chemical properties and broad application prospects. A systematic theoretical simulation method accurately describing atomic interactions for hydrogen-carbon systems is crucial for the design of carbon-based materials and their industrial applications. Multiphases of hydrogenated carbon materials, from crystal to amorphous, with covalent network and diverse chemical reactions bring huge difficulties to construct a general interatomic potential under various conditions. Here, we demonstrate a transferable active machine learning scheme with separated training of sub-feature spaces and target-oriented finetuning, and construct a general-purpose pre-trained machine learning potential (MLP) for hydrogen-carbon systems. The pre-trained MLP is further efficiently transferred to three target spaces of deposition, friction and fracture with scale reliability. This work provides a robust tool for the theoretical research of hydrogen-carbon systems and a general scheme for developing transferable MLPs in multiphase systems across compositional and conditional complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon materials, which include diverse morphologies such as graphene, diamond, carbon nanotubes, amorphous carbon1,2,3,4, etc., have been widely investigated for their potential applications in various fields spanning electronic devices, energy storage, lubrication and wear resistance, owing to the intrinsic electrical conductivity, thermal stability, mechanical strength and tribological property5,6,7,8. Hydrogen, the most abundant element in nature, has been found to significantly affect the performance of carbon materials9,10,11. Through hydrogenation modification, the superior electrical and tribological properties of carbon materials can be achieved with the alterable band-gap9 and electrostatic repulsion of hydrogen10, while the hydrogen embrittlement can also deprave the adhesion strength and wear resistance of carbon coating11. Establishing a systematic research method for hydrogen-carbon system is crucial for the investigation of optimized design of carbon-based materials and their industrial applications.

Carbon materials generally present in various forms, ranging from crystal to amorphous. The rehybridization of the carbon atoms in the covalent network from sp1 to sp3, could lead to the transition between different carbon materials under certain conditions, e.g., graphite-to-diamond transformation with coherent interfaces during the recovery from static compression2, shear induced mechanical amorphization of diamond12, graphitized transformation of amorphous carbon (a-C) film during friction process8,13, etc. In particular, the amorphization behavior in carbon materials has been widely observed under multiple conditions, e.g., defect existence14, fracture and healing15, friction and wear12,16, etc., and can significantly influence the electrical, mechanical and tribological properties of carbon materials. Accurately capturing the structural evolution and hybrid bonding transformation of amorphous carbon is crucial to investigate the physical and chemical properties of carbon materials. However, it still meets challenges as the existing characterization methods are difficult to quantitatively identify the amorphous nanostructure evolution17.

Theoretical simulations, which can provide atomic-level structural information, have been widely used in performance research and material design of carbon systems. Ab initio molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, with quantum-mechanical calculation of the electronic structure, can accurately describe atomic interactions and chemical bonding reactions in carbon systems18,19,20,21. Nevertheless, the computational expense and unfavorable scaling inherent to the ab initio method preclude its use for complex, large-scale dynamic processes. Instead, empirical potentials are employed, which typically exhibit a functional form based on physical/chemical intuition and convenience. However, these potentials are not always sufficiently flexible to accommodate multiple properties simultaneously22, and they are limited in accuracy and transferability with respect to phase transitions, defective structures, and stress-induced structure evolution in carbon materials21,23,24.

Machine learning (ML) methods, which are capable of fitting functions in high-dimensional spaces without specific parameterized functional forms22, have been introduced to construct interatomic potential with density functional theory (DFT) level accuracy for MD simulations25,26,27,28. Many efforts have been made to develop the machine learning interatomic potential in carbon materials for their complicated structural responses under various environmental conditions27,28,29,30, e.g., growth mechanisms of graphene and carbon nanotube on metal surface27,28, graphite–diamond phase transition29, deposition process of tetrahedral amorphous carbon30. A general machine learning potential for amorphous carbon31 was developed at 2017 which was further extended to describe numerous carbon allotropes32 at 2020. Recently, some efforts were made to describe the atomic interactions for hydrogen-carbon systems33,34, including hydrocarbon molecules, even to hydrogenated amorphous carbon. However, a general interatomic potential aiming at larger scale and various conditions with accurate description of the atomic interactions for hydrogen-carbon systems, including equilibrium and non-equilibrium states35, still needs to be developed systematically.

The development of MLPs hinges on the fundamental aspect: generation of an efficient training dataset that encompasses the full structural and chemical space36. For the hydrogen-carbon systems with multiphases and phase transition processes, the comprehensive coverage of structural and chemical space, including the complex hybridization transitions in covalent networks and active hydrogen chemical bonding reactions37, meets a huge challenge. Especially in the amorphous carbon systems, the atomic chemical environment of each atom can exhibit significant variation. However, considering high-quality ab initio calculations with high computational cost, building a training dataset through exhaustive exploration of the chemical space is intractable.

Active learning, which aims at construction of general-purpose models with minimal scope of training data, can help to select the most informative data from unlabeled structures and provides a possibility to construct the MLPs with more efficient and robust dataset38,39. Uncertainty quantification (UQ) is a centerpiece for active learning to mitigate epistemic uncertainty at extrapolative region, especially for the sampling of some rare events39,40,41. Many UQ schemes have been utilized for the facilitation of active learning, e.g., Bayesian neural networks (BNNs)42, Monte Carlo dropout43, D-optimality44, and neural networks (NN) ensemble38, among which, BNNs and NN ensemble have been widely recognized and promoted to the sampling of rare events with enhanced sampling methods45,46, even though these methods could still lead to high computational cost for large and complex systems41.

In this work, we demonstrate a transferable active machine learning scheme for the hydrogen-carbon systems, covering the multiphases from crystal to amorphous structures, with the strategy of separated pre-training of the sub-feature spaces and the target-oriented finetuning. The dataset with the dimensionality reduction of atomic environments was separated to multiple chemical spaces to improve the training efficiency and transferability of MLP model. The transferability and reliability of the model are inspected under three different conditions: growth of hydrogenated amorphous carbon (a-C:H) film on diamond substrate, shear-induced hybrid bonding transformation and structure distortion in a-C:H during friction process and fracture behavior of crystal and amorphous carbon, all of which showing a DFT-level accurate description of atomic interactions. This transferable active machine learning model can be easily applied to any other conditions in hydrogen-carbon systems with selective target-oriented finetuning. This work provides a general scheme for the development of transferable MLPs across any compositional and conditional complexity.

Results

Transferable machine learning model with pre-training and target-oriented optimization

The training strategy of our transferable MLP model for hydrogen-carbon systems is described below and schematically depicted in Fig. 1. The whole training procedure involved a transferable pre-training process and a finetuning optimization at specific target space, and the training processes were carried out with the neural network architecture via DeePMD-kit package47 (see “Methods”). For the pre-train process, the feature space of hydrogen-carbon systems was separated to three major sub-feature spaces: a-C, a-C:H and crystal space, based on the atomic environmental distribution of data structures (further discussion in Fig. 2) to reduce the interference of complex structure information, improving the efficiency of dataset construction (Supplementary Note 1). The initial structures in the sub-feature space were obtained from Material Project database and the melt quenching process in ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations (Supplementary Note 2). In each sub-feature space, an independent two-stage active learning38,48 workflow with NN ensemble for dataset expansion was conducted with the simulation scale transferring from the order of magnitude 102 to 104 atoms to increase the reliability of MLPs over different length scales. During the parallel active learning process, the MLP-driven MD simulations were conducted under various conditions, e.g., extreme temperatures (from 0.1 to 5000 K), large-range pressures (from 1 to 15 GPa) and structure deformation process (Supplementary Table 1), and the enhanced sampling method49 was also utilized to capture the transition state of chemical reactions (e.g., hydrogen transfer reactions) (see “Methods” for more details). Notably, the secondary sub-feature spaces, in which the structure features are partial intersection, can also be utilized for enhanced training of specific atomic environment, which, in this work, were the bulk, slab and homogeneous/heterogeneous interface structures.

a Schematic visualization of the training strategy of our transferable MLP for hydrogen-carbon system, which concluded a pre-training process for separated sub-feature spaces and the target-oriented finetuning. b Schematic diagram of convergence process of MLP in structure space during active learning workflow. There are three major sub-feature spaces in this work: a-C, a-C:H and crystal space with the data points represented in different shapes in Fig. 1b, while the secondary sub-feature spaces, e.g., bulk phase and different surface states, are not shown in this schematic diagram.

Although the pre-trained MLP model could accurately describe the atomic interactions from crystal to amorphous hydrogen-carbon structures, majorly in the stable state, some complex physical and chemical processes, which might include local high stress state or complex stress field distribution and lead to the distortion of hybrid covalent network and active chemical bonding reactions in hydrogen-carbon systems50, could be beyond the describing ability of the pre-trained model, and the specific model optimization for target space with active learning method was introduced. In this work, we considered three complex physical and chemical processes: deposition, friction and fracture, to evaluate the transferability and scale reliability (from small to large) of our MLP model. Basing on the pre-trained MLP model, the similar two-stage active learning (see “Methods”) was also conducted at each target space. During the iterative active learning, the target processes with various physical and chemical reactions, which could be the rare events for the pre-training dataset, were performed in MD simulations with MLP model (more details in “Methods”). For the deposition target space, considering the influence of substrate scale during the depositing, the melt quenching process, which was widely utilized for emulating the diffusion process of local thermal spike during the deposition51,52,53, was conducted in small-scale active learning rather than the deposition process, and for large-scale MD simulations, the deposition and melt quenching process were both carried out for adequate sampling.

For the local high stress state or complex stress field distribution in large-scale simulations, the high error region and state for pre-trained MLP model could emerge only at certain local structures and timepoints, and the high throughput calculations for large-scale structures filtered from active learning method were inefficient and computational costly. Here we introduced an effective local configuration identification method during active learning in large-scale simulations, in which the local high deviation regions were identified and extracted in a large system for labeling (more details in “Methods”). Basing on the uncertainty quantification of NN ensemble38,48, these local configurations with high atomic force deviation were beyond the capability of the MLP model and could contained the unlearned atomic environment information, which therefore were the efficient sampling for the MLP model.

The convergence process of MLP model during the active learning workflow could be represented by a schematic diagram, as shown in Fig. 1b. During the pre-training process with parallel active learning, the sufficient atomic environment information in each sub-feature space was collected efficiently until the MLP model could accurately describe the subspace independently (colored rectangle in Fig. 1b). When the sub-feature spaces were merged to the full feature space (Supplementary Note 3), the interference of different subspaces to model training should be finetuned with limited active learning finetuning to achieve high accuracy description in full feature space. However, there were still other spaces with high uncertainty (shadow region in Fig. 1b) for pre-trained MLP, e.g., some complex physical and chemical processes, which might include local high stress state or complex stress field distribution. These rare events for pre-training dataset would be further finetuned at target space with the two-stage active learning until the target process could be well described.

The final datasets for pre-training process and three different target spaces were shown in Supplementary Table 1, which contained 29,885 structures with ~9.6 million atoms totally, and was randomly divided into the training set (90%) and the testing set (10%) for the model training and validation test, respectively. Further, a similarity metric of atomic environment, Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP)54,55, and a non-linear dimensionality reduction technique, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP)56, were used to visualize the chemical diversity of atomic environments in our datasets, which we called the SOAP-based UMAP embedding method in the following text, as shown in Fig. 2. About 300 structures in pre-training and target-space datasets including more than 45,000 atomic environments were randomly selected to create the map, in which each point represented an atomic environment, and different colors in Fig. 2 represented the different categories of structures in the insets, and the atomic energy and relative energy error of these atomic environments were shown in the Supplementary Fig. 3. As shown in SOAP-based UMAP map, the atomic environments from target space of friction, deposition, and fracture were partly covered by the sub-feature datasets, which indicated that the pre-trained model was general-purpose and could be applied to various applications. Notably, the atomic environments of amorphous crack structures were also covered by the crystal crack structures, indicating that the information learned from crystal structures could be transferred to related amorphous structures.

Points in this map were the two-dimensional UMAP embedding of high-dimensional SOAP vectors to visualize and compare the atomic environments in our datasets, colored by different categories of the structures, and their related typical configurations were inserted in the gray circles. The typical configurations in target spaces, which were deposition, friction, and fracture space, were highlighted in the gray squares, represented in color of scarlet, yellow, and orange. In all the snapshots inserted, the gray atoms represented the carbon atoms and the light blue atoms represented the hydrogen atoms.

Validation of MLP models: from crystal to amorphous

Firstly, the validation of the pre-trained model was verified in calculating the atomic interactions in crystal hydrogenated carbon systems, as shown in Fig. 3. The bonding energy curves of hydrogen atom at surface of graphene and diamond (Fig. 3a, b) were calculated, showing high accuracy near the equilibrium position compared to DFT method, while a slight deviation at extreme short-distance57 or far away from equilibrium position which needed to be further optimized. Notably, the test configurations for bonding energy of hydrogen atom were not included in the pre-training dataset, indicating the transferability of the pre-trained MLP model. Calculations of energy barriers of hydrogen transfer process and van der Waals interactions between the layers of graphite and hydrogenated graphite in AB stacking mode were also highly consistent with the DFT results with the average error of the energy per atom to be 2.2, 2.3, 5.2 and 2.1 meV/atom, respectively (Fig. 3c–e, g). The total energy change versus the distance between created surfaces was calculated by separating the ideal crystal structure to create new diamond (111) surfaces, which also showed a high consistency between MLP results and DFT calculations with the average error of the energy per atom to be 21.0 meV/atom (Fig. 3f). The MLP results were also compared with other methods and the numerical error were listed (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3). Further, we applied the pre-trained MLP model to the shear-induced diamond-to-graphite transfer process (Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Fig. 5), showing the same structure transformation as the DFT calculations21. The critical shear stresses for the transition process in our work also showed the higher consistency with the DFT results compared with the empirical potentials30 (Supplementary Table 4).

Bonding energy curves of (a) hydrogen atom at graphene surface and (b) hydrogen atom at diamond (100) surface. Energy barriers for (c) hydrogen atom transferring along armchair at graphene surface with distance of 1.1 Å and (d) hydrogen atom transferring along [010] direction at diamond (100) surface with distance of 1.1 Å. The total energy change versus separation distance of (e) layers of graphite in AB stacking mode, (f) decohesion simulations for diamond (111) surface, (g) layers of hydrogenated graphite in AB stacking mode and hydrogenated diamond (111) surfaces. The ‘D’ in (a) and (b) represented the distance between the atomic centers of hydrogen and carbon atoms, in (e), (g), (h) represented the minimum distance between carbon atoms in the out-of-plane direction between adjacent atomic layers, and in (f) represented the separated distance between the created surfaces. The ‘d’ in (c) and (d) represented the distance of atomic centers of hydrogen atom moving in the in-plane direction. The snapshots for different processes were inserted with the gray and blue spheres representing the carbon and hydrogen atoms. The ‘Distance’ axis represented the ‘D’ perpendicular to the surface in (a), (b), (e–h), and the ‘d’ parallel to the surface in (c, d). The Energy error represented the absolute error between DFT and MLP calculations.

The reliability of pre-trained MLP model was further verified for hydrogenated amorphous carbon systems. The properties of amorphous carbon, including the Young’s modulus, bulk modulus and shear modulus, were calculated over a wide scaling of hydrogen content and density (Supplementary Table 5), which also showed the DFT level accuracy, indicating the general adaptability of the pre-trained MLP model in hydrogen-carbon systems, from crystal to amorphous structures. Besides, the same calculations were also conducted in large scale with MLP model to confirm its scale reliability, as shown in Table 1.

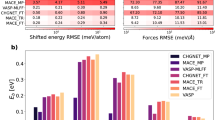

Although the pre-trained MLP model showed the general reliability of the hydrogen-carbon systems, some complex physical and chemical processes including local high stress state or complex stress field distribution could be beyond the describing ability of the pre-trained MLP model, for example, the deposition, friction and fracture processes. After active learning finetuning of the pre-trained MLP model at target spaces, the MLP models presented highest accuracy of the corresponding test datasets (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 5). Notably, the target-oriented finetuning processes could be achieved based on the target datasets with an order of magnitude fewer structures than pre-training datasets for all three different target conditions (Supplementary Table 1), indicating the high transferability of pre-trained MLP model and high efficiency of the target-oriented finetuning process based on the active learning methods. The accuracy of MLP models in target spaces were also evaluated compared with the empirical potentials (Table 3 and Supplementary Note 6), and the relative errors were provided (Supplementary Table 6). Since the Tersoff’s empirical bond order potential is not suitable for deposition of hydrocarbons molecules (C2H2 and CH4 used in this work), the corresponding value in Table 3 is vacant. The MLP models with best performance in three target spaces were tested, respectively, and the orders of magnitude improvement of accuracy were investigated with the computational efficiency comparable with the empirical potentials (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Performance in multi-target conditions and scale reliability

Based on the target-oriented MLP models, we carried out the MD simulations for the three target conditions to evaluate their performance and scale reliability. Firstly, the well-trained MLP model was used for the construction of a-C:H structure via both melt quenching and the deposition process (see “Methods”), as shown in Fig. 4. The radial distribution functions (RDFs) of C–C and C–H in both melting liquid structures and amorphous carbon structures with atoms from 200 to 10,000 showed good agreement with the AIMD simulations (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating the high reliability of MLP models in large scale. Further, the melt quenching process was carried out in large scale (10,000 atoms) to construct the a-C:H with a series of hydrogen content, which also showed consistent RDFs with the structures in small scale AIMD simulations (Fig. 4a). The simulation setting of MLP based MD and AIMD In this way, the ideal a-C:H structures could be constructed in any required scale with our MLP model, overcoming the multi-periodic repeating of the a-C:H in small cell from AIMD simulations. As the a-C:H could be used as the protective and lubricating coating8,20, the growth of a-C:H film on diamond (100) from deposition process was also carried out with the MLP model (see “Methods”). With a gradient area of structure between the substrate and surface, the stable growth of a-C:H was achieved with the almost constant sp3 content, relative density and hydrogen content (shadow area in Fig. 4b), which was also observed in the growth of ta-C with a machine learning potential developed for carbon-only system30. The stable growth structure of a-C:H also showed the DFT level accuracy with the consistent RDFs with the structures in AIMD simulations, as shown in Fig. 4c.

a Radial distribution functions of C–C and C–H in a-C:H with different hydrogen contents constructed with the MLP model for deposition target space and AIMD simulations, respectively, in the same melt quenching process except for timesteps. The RDF was calculated from the configurations in NVT simulations under 300 K for 3 ps. b Atomic configuration of a-C:H film constructed through the deposition process with the MLP model and its properties along the growth direction of film. The gray and blue spheres representing the carbon and hydrogen atoms. The density is the relative value normalized by diamond. c Radial distribution functions of C–C and C–H in a-C:H constructed in AIMD melt quenching process and MLP based deposition process.

In order to evaluate the capability of the target-oriented MLP model to describe the passivated interface in stable friction and the hybrid bonding transformation during the running-in process in hydrogen-carbon systems, the friction tests of hydrogen passivated diamond (111) surface and a-C:H with 30 at.%H were conducted with the MLP model, as shown in Fig. 5. Firstly, the sliding potential surface energy (PES) corrugations ΔE of hydrogen passivated diamond (111) interface with respect to the surface stacking mode with minimum energy was calculated, as well as the corresponding lateral force (Supplementary Note 7). A highly consistent PES corrugations during sliding was observed between MLP and DFT results with the average error of 0.05 meV/Å2 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 9), as well as the lateral force with the average error of 0.24 meV/Å3. The interfacial adhesion of the hydrogen passivated diamond (111) interface was calculated to be 0.37 J/m2, consistent with the DFT results and the previous work58, showing a better performance than other methods (Supplementary Table 7).

a, b Frictional energy landscape of hydrogen passivated diamond (111) interface. a Sliding PES corrugations ΔE calculated by DFT. b The potential profile (ΔE, red) and lateral force (F, blue) along the sliding pathways calculated by DFT and MLP. The step lengths along x ([\(1\bar{1}0\)]) and y ([\(11\bar{2}\)]) axis for the sliding systems are 0.25 Å and 0.435 Å. The inserted snapshots were the bidimensional representations of hydrogen passivated diamond (111) interface and the sliding directions, respectively. The gray and blue spheres representing the carbon and hydrogen atoms. c–e Typical bonding reorganization in friction process of a-C:H with 30 at.%H with target-oriented MLP model. c Snapshots of typical bonding reorganization in MD simulations of friction process with MLP model in friction target space. The black arrows at bottom left represented the direction of x and z axis in MD simulation. The gray and blue spheres represent the carbon and hydrogen atoms. d Change of the hybridization of C3 in the four bonding states of (c). The yellow and green square represented the sp2 bond and sp3 bond area. The MBA and SDBA represented the mean of bond angles and the standard deviation of bond angles (red and blue dot, respectively). e Frequency of sp3 jumping during the friction process.

Then, the MLP based MD simulation was carried out for the friction process of a-C:H with 30 at.%H (see “Methods”), and a typical bonding reorganization process during the friction was extracted with four bonding states, as shown in Fig. 5c–e. As the reliability of dynamic evolution during the friction process was confirmed with the highly consistent evolution curve of energy and friction force with DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 10) and the chemical desorption of hydrocarbons on surface dangling bonds could be well described (Supplementary Fig. 11), we focused on the capability of MLP model to describe the local bonding reorganization and the formation and release of distorted structures during the friction.

As shown in Fig. 5c, the shear-induced C–C bond stretch and twist was observed, followed with the bonding reorganization. The bond angles between central carbon and its surrounding atoms were calculated and the mean value and standard deviation of bond angles for the four target carbon atoms were extracted in four bonding states to investigate the hybrid bonding transformation and the bonding distortion, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 12, the C1 and C2 atom could maintain the sp2 and sp3 hybridization states, respectively, however, with the shear-induced bonding distortion, while the hybrid bonding transformation was observed for C3 and C4 with the release of the distorted bonds. Notably, the hybrid bond shift jumping from sp2-sp3-sp2 was observed (sp3 jumping bridge in Fig. 5d), which significantly released the sp2 bonding twist, indicating the crucial role of hybrid bonding transformation for the release of distorted structures in carbon network. Further, the frequency of sp3 jumping during the friction process was calculated and the occurrence of the jumping event showed the dependence with the friction force during the sliding, as shown in Fig. 5e, indicating a stress-assisted hybrid bonding transformation at the sliding interface. The similar effect of bonding reorganization in a-C:H system including the hybridization transition and hydrogen transfer reactions was also observed in the MLP based large-scale MD simulations for shear-induced structure ordering transformation of a-C:H in our previous work50, indicating the scale reliability of the MLP model.

Finally, the atomic-scale quasi-static fracture and static decohesion MD simulations were carried out with the MLP model for fracture target space (see “Methods”), as shown in Fig. 6a, c. During the propagation of diamond [001] crack front on the (110) plane and graphene in-plane crack front along the zigzag edge, the change of bond length on the site of crack-tip could be well described with DFT level accuracy. The cleavage behavior of other crystal carbon cracks was also well described, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13, consistent with the previous works and DFT results, and the corresponding accuracy plotted in Supplementary Fig. 14 showed the error in the magnitude of 10−2 eV/atom23,26,59. The effect of hydrogen on the diamond [001] crack front on the (110) plane was also tested with acceptable accuracy (Supplementary Fig. 15), and it could be seen that the absorption of hydrogen on the crack edge lead to break of the bond at the crack-tip, which can assist the propagation of the crack. Physically, as the fracture was a process of creating new surfaces, decohesion simulations of diamond and graphene were performed for further validation23,24. The total energy change versus the distance between created surfaces was calculated by separating the ideal crystal structure to create new diamond (110) surfaces or new graphene zigzag edges, and the cohesive stress was the first derivative of total energy curves normalized by the created surface area, which also showed a high consistency between MLP results and DFT calculations (Fig. 6b, d).

Bond length change versus normalized stress intensity factor by the value of fracture toughness (\({{K}_{{\rm{{\rm I}}}}/K}_{{\rm{{\rm I}}}{\rm{C}}}\)): (a) for diamond [001] crack front propagation on the (110) plane and (c) for graphene in-plane crack front propagation along the zigzag edge. The ‘L’ in (a) and (c) represented the distance between the atomic centers on the site of the crack-tip. The energy and force change versus separation distance extrapolated from decohesion simulations: (b) for diamond (110) and (d) for graphene zigzag edge. The ‘D’ in (b) and (d) represented the separated distance between the created surfaces or edges. The snapshots for the processes above were inserted with the gray spheres representing the carbon atoms, and the blue spheres representing hydrogen atoms. Fracture toughness (\({K}_{{\rm{{\rm I}}}{\rm{C}}}\)) extrapolated from the MD simulations: (e) for a-C with different density (2.0–3.2 gcm−3) and (f) for a-C:H with different hydrogen content (10–40 at.%H).

Different from the perfect cleavage and lattice-trapping effect of fracture of crystals, the fracture process zone of amorphous carbon was an ensemble of highly-stressed and distorted atomic environments, with cross-linked carbon networks containing hundreds of atoms at least, and the crack-tip propagated bond by bond. With the fracture-targeted model, we performed fracture simulations of a-C with different density and a-C:H with different hydrogen content to evaluate the fracture toughness (Supplementary Fig. 16). As shown in Fig. 6e, the fracture toughness of a-C increased with density, while for a-C:H, it decreased with hydrogen content. Four specimens with different amorphous structure were used in our simulations for each density and H content. The R curves of each specimen were shown in Supplementary Fig. 17 (Supplementary Note 8), which represent the amplitude of load (i.e., stress intensity factor) versus change of crack length, and the vertical coordinate of the inflection point when the value of crack length turns from zero to positive is the critical stress intensity factor (\({K}_{{\rm{{\rm I}}}{\rm{C}}}\)), i.e., fracture toughness of the specimen60. The range of calculated fracture toughness was in typical range of reported value: 0.8–4.4 \({\rm{MPa}}\sqrt{{\rm{m}}}\)61,62,63, measured by micro-tests of a-C:H. Toughness of hydrogenated structures was significantly lower than pure carbon, indicating that hydrogenation would cause brittleness of a-C11,64, which also needed further investigation.

Discussion

In summary, a transferable machine learning model for the hydrogen-carbon systems from crystal and amorphous structures was demonstrated. The separated training of the sub-feature spaces followed with a target-oriented finetuning was introduced accompanied by the dimensionality reduction of atomic environments for the efficient generation of training datasets with a multi-scale active learning scheme. The training paradigm of the transferable active machine learning model can be concluded as follows: (1) Clarify the structures of the research system and construct the initial datasets. The initial structures can be from the existing datasets, e.g., Material Project database, or a standard scheme for structure construction; (2) Dimensionality reduction of atomic environments in initial datasets and dividing the sub-feature spaces; (3) Training and iterative optimization of the MLP in sub-feature spaces separately with multi-scale active learning scheme; (4) Merging the sub-feature datasets based on the target spaces and building the pre-trained MLP model; (5) Training and iterative optimization of the MLP in target spaces based on the merged pre-training datasets with the target-oriented active learning. This transferable active machine learning paradigm provides a scheme for the development of MLP in any other systems across compositional and conditional complexity.

The transferability and scale reliability of the model was further evaluated at deposition, friction and fracture target spaces, showing the excellent performance. The ideal a-C:H structures could be constructed in any required scale with the deposition-target MLP model, overcoming the multi-periodic repeating of the a-C:H in small cell from AIMD simulations. The shear-induced complex hybrid bonding transformation and structure distortion in carbon network could also be well described with our MLP model as confirmed in friction test. Finally, the cleavage behavior in crystal carbon fracture could be correctly described with our MLP model and the fracture toughness of a-C(:H) was consistent with experimental results. This transferable MLP provides a general model for hydrogen-carbon systems and can be easily expanded to any other target conditions, providing a powerful tool for the theoretical research and atomic understanding of hydrogen-carbon systems.

Methods

Construction of pre-training dataset

The pre-training dataset was constructed with three parts: AIMD based initial dataset, data from active learning in small scale and data from active learning in large scale. The initial dataset (gray part in Fig. 1a) for the zero iteration MLP model before the sampling process with two-stage active learning was constructed under various conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure, cell scaling and shifting) with AIMD simulations (see Supplementary Table 1 for detail setting), and the iterative active learning driven by MLP was further conducted. During the first-stage active learning, the a-C:H structures in small scale (order of magnitude 102 atoms) were considered in the same range of temperature and pressure with NVT and NPT ensemble. The NN ensemble (Strategy of uncertainty quantification in “Methods” for more details) was utilized for the uncertainty quantification of the active learning. The biased MD simulation was performed only in the regions where the uncertainty indicator was low49. The configurations with high deviation of atomic forces in NN ensemble were labeled directly in DFT calculations considering the acceptable computational cost, and then added to the dataset (Refine data in Fig. 1a). For the second-stage active learning, the structures were expanded to the order of magnitude 104 atoms (Scale expansion in Fig. 1a) and only the high deviation regions of atomic forces in a whole configuration were extracted to be labeled in DFT calculations during the active learning. The strategy of labeling region extraction in large-scale active learning would be discussed in the next part.

Strategy of local configuration extraction for large-scale active learning

Taking the friction process as an example, we introduced the strategy of local configuration extraction for large-scale active learning, as shown in Fig. 7. The large-scale MD simulations for friction processes of crystal and a-C(:H) with various densities and hydrogen contents were conducted with the pre-trained MLP model, and the atomic forces in the configurations during the friction were calculated for uncertainty quantification (Strategy of uncertainty quantification in “Methods” for more details). The deviation of atomic force (DAF) between three parallel MLP models were calculated and mapped to the configurations during the friction, as shown in Fig. 7b. The high error regions were extracted as the center of a cubic cell in (12 × 12 × 12) Å with a vacuum of 10 Å (Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Fig. 19), and the structures within the central sphere with a diameter of 7 Å (the dotted circle in Fig. 7c) were fixed to maintain the local atomic environment to be calibrated while the surrounding atoms (the shadow region in Fig. 7c) were fully relaxed in DFT calculation. All the labeled local configurations were added to the datasets for the finetuning of the MLP model at target space.

a Friction evolution with time of self-mated a-C:H with 40 at.%H. b Snapshots of sliding interfacial atomic structure of self-mated a-C:H with 40 at.%H at different timepoints during the friction and the corresponding distribution of atomic force error. The purple and gray atoms represented the carbon atoms and the yellow and light blue atoms represented the hydrogen atoms in the snapshots. c Local high error region extraction and labeling during active learning finetuning. Take the snapshots of sliding interfacial atomic structure at 400 ps as an example. The high error local structures were extracted from large friction system with the high error center fixed and the surrounding atoms were fully relaxed in DFT calculation.

Strategy of uncertainty quantification

In this work, the neural networks (NN) ensemble38,48 was utilized for the uncertainty quantification of the active learning. The MD simulations were conducted with a MLP model, and the atomic forces in the configurations during the simulations were recalculated with other two MLP models, which were trained based on the same pre-training datasets and with same neural network parameters. As the three parallel MLP models shared the same datasets and learning ability, they should have the similar descriptive accuracy for the atomic environment covered in the datasets38 and the high deviation region could contain the unlabeled atomic structures in target space, which should be further finetuned. For the small-scale active learning, the deviation of model (DM) was defined as the maximum standard deviation of the predictions for the atomic forces following the formula (1):

where i is the ith atom in the structure with N atoms, \(\bar{{f}_{i}}\) is the mean atomic force value and the ensemble average 〈…〉 is taken over the ensemble of models38. The configurations with DM above a certain threshold (0.8–2 eV/Å) were extracted for further labeling in DFT calculation. Meanwhile, an upper threshold (3–5 eV/Å) was also introduced, above which the configuration shown high uncertainty and could be unfavorable for DFT convergence and model fitting65. The determination of the thresholds was further discussed in Supplementary Note 10.

For the large-scale active learning, the deviation of atomic force (DAF) between three parallel MLP models were calculated and the deviation of atomic force was defined with the following formula:

where the \({({f}_{i})}_{max }\) and \(\bar{{f}_{i}}\) are the maximum and mean atomic force value calculated with three parallel MLP models, respectively. The similar thresholds (lower threshold (0.8–2 eV/Å) and upper threshold (3–5 eV/Å)) were also defined for the identification of local high error regions. Notably, the DAF of all the atoms in the extracted high error regions should be lower than the upper threshold, not only for the central atoms.

Training of machine learning potentials

The MLPs was trained with neural network architecture via DeePMD-kit package47 to learn the atomic environment information of the structures in training set, which was treated by an environment matrix and an embedding matrix to construct the descriptors and map the atomic structures with atomic forces and energies. The descriptor was set up with both angular and radial atomic configurations, and the embedding and fitting networks both included 3 hidden layers with the neural of (25, 50, 100) and (240, 240, 240) neurons, respectively. In the model, the energy was evaluated in forward propagation, while the atomic force which is the gradient of the potential energy, was calculated in the backward propagation66. The cutoff radius for neighbor researching was set to 7 Å to consider the long-range interaction in hydrogen-carbon system. The starting and final learning rates were set to 1.0 × 10−3 and 1.6 × 10−8, respectively. A total of 5 × 106 steps was set to train the MLP model for each iteration.

Atomic environment mapping

The similarity metric of atomic environment to generate Fig. 2: Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) is a descriptor based on the idea of a local-basis expansion of the atomic neighbor density and subsequent construction of a rotationally invariant power spectrum54. To efficiently capture the atomic neighbor environment of structures, hyper-parameters related to the radial resolution were set to: rcut = 7 Å, nmax = 12, and the angular resolution is determined by lmax = 6. The Gaussian function width σ was proportional to the corresponding rcut by σ = rcut/8. The DScribe python library was used to generate the SOAP descriptors of atoms55. To visualize the similarity between high-dimensional SOAP vectors, the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) was used to reduce the dimension, and represent the similarity of SOAP vectors as the distance between points in a two-dimensional map.

Density functional theory calculations

DFT calculations were performed with Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)67,68. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)69 generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional was used for all hydrogen-carbon systems in this work. The optB86b-vdW exchange–correlation functional70 was utilized to approximately describe the dispersion interaction (van der Waals forces). For the static calculations, high precision (PREC = Accurate) was employed with a plane wave cutoff energy of 600 eV (ENCUT = 600) and no symmetry constraints applied (ISYM = 0). The electronic convergence criterion (EDIFF) was set at 10−6 eV, and the smallest allowed spacing between k points (KSPACING) was set at 0.14 Å−1. Gaussian smearing (ISEAR = 0) was utilized with a smearing width of 0.05 eV (SIGMA = 0.05) to assist in the convergence of the calculations. For the DFT-based (“ab initio”) molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, the k points were set to 1*1*1 for the systems with more than 100 atoms otherwise set to 2*2*2, and the time step was 1 fs. The quenching process adopted micro canonical ensemble (NVE), while the melting and relaxing processed were conducted with regular ensemble (NVT).

MLP based molecular dynamics simulations

The MLP based molecular dynamics simulations were performed with Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)71. The time step of 0.2 fs was used with the Velocity Verlet algorithm to integrate the equations of motion.

NVT/NPT relaxation

Simulations took place in the NVT and NPT ensemble using a Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat with a temperature damping parameter of 0.02 ps. The temperature for relaxation process ranged from 0.1 to 5000 K with the interval of 50 K under 500 K and the interval of 500 K at higher range. The pressure was set from 1 to 15 GPa with the interval of 2 GPa.

Melt quenching process

The NVT ensemble was used for the melt quenching process. The carbon and hydrogen atoms were generated at a series of densities ranging from 1.6 to 3.5 gcm−3 and hydrogen contents ranging from 0 to 40 at.%H in the specific cell lattice and relaxed at a constant temperature of 5000 K for 3 ps, followed by a quenching process with temperature decreasing from 5000 to 300 K within 0.5 ps to obtain the amorphous carbon structures. The quenched structures were further relaxed under temperature of 300 K for 3 ps to improve their stability.

Deposition and growth of a-C:H film

Diamond (100) surface was constructed with the dimension of 28.5 * 28.5 * 15 Å to be the substrate of a-C:H film, and the carbon source for the deposition was set to C2H2 molecules. The bottom two atomic layers were fixed. The remaining region was coupled to Langevin thermostats at a temperature of 300 K except for a cylindrical volume, which centered at the incident direction of C2H2 molecules, and the atoms inside the cylinder could move freely. Periodic boundary conditions were applied along both x and y directions. The incident energy was set to 30 eV per carbon atom. The time interval between two sequential incident was set to 1 ps to achieve full relaxation of substrate and film.

Friction

The structure of a-C:H with 30 at.%H with 432 atoms was constructed for friction process with melt quenching process in AIMD simulation, and the front views of the atomistic model are presented in Supplementary Fig. 10. The models were divided into three parts along the z direction as fixed layer (considered as rigid body), Langevin thermostat layer for the temperature control and free layer where the atoms were free of constraints so that they moved according to the interatomic forces. Periodic boundary conditions were applied to both x and y directions to mimic laterally infinite surface. A constant velocity of 20 m/s was endued to the up fixed layer along the x direction to drive the sliding process.

Fracture

A constant increment of stress intensity factor \(\Delta {K}_{{{\rm{I}}}}=0.05{\rm{MPa}}\sqrt{{\rm{m}}}\) was used for fracture loading (details of the fracture loading method are introduced in Supplementary Note 11), and the results of different increments in Supplementary Fig. 20 showed that the selected \(\Delta {K}_{{\rm{{I}}}}=0.05{\rm{MPa}}\sqrt{{\rm{m}}}\) was proper. The a-C:H plate specimen for fracture simulations were generated by melt quenching with densities ranging from 2.0 to 3.2 gcm−3 and hydrogen contents ranging from 0 to 40 at.%H. The front view of a typical specimen is shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, with 3 nm or 10 nm radius and about 2 nm thickness, containing about 6000–10,000 or 80,000–100,000 atoms. The outmost layer with thickness of about 0.5 nm was set rigid during the simulation, and the atoms within Rfree were fully relaxed at 0.1 K with NVT ensemble after each load step.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science 324, 1312–1314 (2009).

Luo, K. et al. Coherent interfaces govern direct transformation from graphite to diamond. Nature 607, 486–491 (2022).

Utsumi, S. et al. Giant nanomechanical energy storage capacity in twisted single-walled carbon nanotube ropes. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-024-01645-x (2024).

Bhaskaran, H. et al. Ultralow nanoscale wear through atom-by-atom attrition in silicon-containing diamond-like carbon. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 181–185 (2010).

Biswas, C. & Lee, Y. Graphene versus carbon nanotubes in electronic devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 3806–3826 (2011).

Raccichini, R., Varzi, A., Passerini, S. & Scrosati, B. The role of graphene for electrochemical energy storage. Nat. Mater. 14, 271–279 (2015).

Yu, Q. et al. Ion energy-induced nanoclustering structure in a-C:H film for achieving robust superlubricity in vacuum. Friction 10, 1967–1984 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Unraveling the friction evolution mechanism of diamond‐like carbon film during nanoscale running‐in process toward superlubricity. Small 17, 2005607 (2021).

Cahangirov, S., Topsakal, M., Akturk, E., Sahin, H. & Ciraci, S. Two- and one-dimensional honeycomb structures of silicon and germanium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 236804 (2009).

Erdemir, A. Genesis of superlow friction and wear in diamondlike carbon films. Tribol. Int. 37, 1005–1012 (2004).

Shin, D. & Kim, S. Effect of hydrogen embrittlement on mechanical characteristics of DLC-coating for hydrogen valves of FCEVs. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 47 (2024).

Pastewka, L., Moser, S., Gumbsch, P. & Moseler, M. Anisotropic mechanical amorphization drives wear in diamond. Nat. Mater. 10, 34–38 (2011).

Chen, W. & Ma, T. Interfacial tribochemical kinetics: a new perspective on superlubricity of diamond-like carbon films. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 67, 2050–2052 (2024).

Carpenter, C., Ramasubramaniam, A. & Maroudas, D. Analysis of vacancy-induced amorphization of single-layer graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 203105 (2012).

Qiu, K. et al. Self-healing of fractured diamond. Nat. Mater. 22, 1317–1323 (2023).

Kunze, T. et al. Wear, plasticity, and rehybridization in tetrahedral amorphous carbon. Tribol. Lett. 53, 119–126 (2014).

Chu, P. & Li, L. Characterization of amorphous and nanocrystalline carbon films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 96, 253–277 (2006).

Zhang, S. et al. Domino-like stacking order switching in twisted monolayer–multilayer graphene. Nat. Mater. 21, 621–626 (2022).

Dag, S. & Ciraci, S. Atomic scale study of superlow friction between hydrogenated diamond surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 70, 241401 (2004).

Pei, L. et al. Regulating vacuum tribological behavior of a-C:H film by interfacial activity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 10333–10338 (2021).

Chacham, H. & Kleinman, L. Instabilities in diamond under high shear stress. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4904 (2000).

Bartók, A., Kermode, J., Bernstein, N. & Csányi, G. Machine learning a general-purpose interatomic potential for silicon. Phys. Rev. X 8, 041048 (2018).

Pastewka, L., Klemenz, A., Gumbsch, P. & Moseler, M. Screened empirical bond-order potentials for Si-C. Phys. Rev. B 87, 205410 (2013).

Pastewka, L., Pou, P., Pérez, R., Gumbsch, P. & Moseler, M. Describing bond-breaking processes by reactive potentials: Importance of an environment-dependent interaction range. Phys. Rev. B 78, 161402 (2008).

Lin, S. et al. Machine-learning potentials for nanoscale simulations of tensile deformation and fracture in ceramics. npj Comput Mater. 10, 67 (2024).

Yu, M., Zhao, Z., Guo, W. & Zhang, Z. Fracture toughness of two-dimensional materials dominated by edge energy anisotropy. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 186, 105579 (2024).

Zhang, D., Yi, P., Lai, X., Peng, L. & Li, H. Active machine learning model for the dynamic simulation and growth mechanisms of carbon on metal surface. Nat. Commun. 15, 344 (2024).

Hedman, D. et al. Dynamics of growing carbon nanotube interfaces probed by machine learning-enabled molecular simulations. Nat. Commun. 15, 4076 (2024).

Marchant, G., Caro, M., Karasulu, B. & Pártay, L. Exploring the configuration space of elemental carbon with empirical and machine learned interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 131 (2023).

Caro, M., Deringer, V., Koskinen, J., Laurila, T. & Csányi, G. Growth mechanism and origin of high sp3 content in tetrahedral amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 166101 (2018).

Deringer, V. & Csányi, G. Machine learning based interatomic potential for amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 95, 094203 (2017).

Rowe, P., Deringer, V., Gasparotto, P., Csányi, G. & Michaelides, A. An accurate and transferable machine learning potential for carbon. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 034702 (2020).

Faraji, S. & Liu, M. Transferable machine learning interatomic potential for carbon hydrogen systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 22346 (2024).

Ibragimova, R., Kuklin, M., Zarrouk, T. & Caro, M. Unifying the description of hydrocarbons and hydrogenated carbon materials with a chemically reactive machine learning interatomic potential. Chem. Phys. 08194; arXiv:2409.08194 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Exploring the frontiers of condensed-phase chemistry with a general reactive machine learning potential. Nat. Chem. 16, 727–734 (2024).

Qi, J., Ko, T., Wood, B., Pham, T. & Ong, S. Robust training of machine learning interatomic potentials with dimensionality reduction and stratified sampling. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 43 (2024).

Hayashi, K. et al. Tribochemical reaction dynamics simulation of hydrogen on a diamond-like carbon surface based on tight-binding quantum chemical molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C. 115, 22981–22986 (2011).

Zhang, L., Lin, D., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. Active learning of uniformly accurate interatomic potentials for materials simulation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 023804 (2019).

Thaler, S., Doehner, G. & Zavadlav, J. Scalable Bayesian uncertainty quantification for neural network potentials: promise and pitfalls. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 4520 (2023).

Smith, J. et al. Automated discovery of a robust interatomic potential for aluminum. Nat. Commun. 12, 1257 (2021).

Tan, A., Urata, S., Goldman, S., Dietschreit, J. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Single-model uncertainty quantification in neural network potentials does not consistently outperform model ensembles. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 225 (2023).

Vandermause, J. et al. On-the-fly active learning of interpretable Bayesian force fields for atomistic rare events. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 20 (2020).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian approximation: representing model uncertainty in deep learning. Proc. Mach. Learn. 48, 1050 (2016).

Podryabinkin, E. & Shapeev, A. Active learning of linearly parametrized interatomic potentials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 140, 171 (2017).

Molina-Taborda, A., Cossio, P., Lopez-Acevedo, O. & Gabrié, M. Active learning of Boltzmann samplers and potential energies with quantum mechanical accuracy. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 8833 (2024).

Jung, G., Choi, J. & Lee, S. Active learning of neural network potentials for rare events. Digit. Discov. 3, 514 (2024).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & E, W. DeePMD-kit: A deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Jinnouchi, R., Miwa, K., Karsai, F., Kresse, G. & Asahi, R. On-the-fly active learning of interatomic potentials for large-scale atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 6946–6955 (2020).

Zhang, L., Wang, H. & E, W. Reinforced dynamics for enhanced sampling in large atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 124113 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Ultralow-friction at cryogenic temperature induced by hydrogen correlated quantum effect. Small 20, 2400083 (2024).

Marks, N., McKenzie, D., Pailthorpe, B., Bernasconi, M. & Parrinello, M. Ab initio simulations of tetrahedral amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 54, 9703 (1996).

McCulloch, D., McKenzie, D. & Goringe, C. Ab initio simulations of the structure of amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 2349 (2000).

Salinas Ruiz, V. et al. Interplay of mechanics and chemistry governs wear of diamond-like carbon coatings interacting with ZDDP-additivated lubricants. Nat. Commun. 12, 4550 (2021).

Bartók, A., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

Himanen, L. et al. DScribe: Library of descriptors for machine learning in materials science. Comput. Phys. Commun. 247, 106949 (2020).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. Umap: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/ abs/1802.03426 (2018).

Wang, H., Guo, X., Zhang, L., Wang, H. & Xue, J. Deep learning inter-atomic potential model for accurate irradiation damage simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 244101 (2019).

Wolloch, M., Levita, G., Restuccia, P. & Righi, M. C. Interfacial charge density and its connection to adhesion and frictional forces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026804 (2018).

Qamar, M., Mrovec, M., Lysogorskiy, Y., Bochkarev, A. & Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for quantum-accurate large-scale simulations of carbon. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 5151–5167 (2023).

Khosrownejad, S., Kermodw, J. & Pastewka, L. Quantitative prediction of the fracture toughness of amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 023602 (2021).

Jonnalagadda, K., Cho, S., Chasiotis, I., Friedmann, T. & Sullivan, J. Effect of intrinsic stress gradient on the effective mode-I fracture toughness of amorphous diamond-like carbon films for MEMS. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 56, 388–401 (2008).

Schaufler, J., Schmid, C., Durst, K. & Göken, M. Determination of the interfacial strength and fracture toughness of a-C:H coatings by in-situ microcantilever bending. Thin Solid Films 522, 480–484 (2012).

Shin, D. & Jang, D. Crack-tip plasticity and intrinsic toughening in nano-sized brittle amorphous carbon. Int. J. Plast. 127, 102642 (2020).

Tamura, M. & Kumagai, T. Hydrogen permeability of diamondlike amorphous carbons. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 35, 04D101 (2017).

Erhard, L., Rohrer, J., Albe, K. & Deringer, V. Modelling atomic and nanoscale structure in the silicon–oxygen system through active machine learning. Nat. Commun. 15, 1927 (2024).

Lu, D. et al. 86 PFLOPS deep potential molecular dynamics simulation of 100 million atoms with ab initio accuracy. Comput. Mater. Sci. 259, 107624 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dion, M., Rydberg, H., Schröder, E., Langreth, D. & Lundqvist, B. Van der Waals density functional for general geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 246401 (2004).

Thompson, A. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52225502, 52305200), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE, National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFB3410201, 2018YFB0704300), Scientific and Technological Project of Yunnan Precious Metals Laboratory (YPML-20240502088), Key Research and Development Program of Yunnan Province (202203ZA080001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.C. and Z.X. contributed equally to this work. W.C. and T.M. conceived and designed the project. W.C. conducted the construction of the transferable active machine learning scheme, training of MLP models, MD simulations, and DFT calculations. Z.X. conducted the dimensionality reduction of atomic environments in datasets, finetuning of MLP model in fracture target space, and test of empirical interatomic potentials. W.C., Z.X., A.S., and T.M. contributed to the writing, review and editing of the paper. K.W. and L.G. contributed to the discussion and results analysis. W.C., Z.X., and T.M. contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Xu, Z., Wang, K. et al. Transferable machine learning model for multi-target nanoscale simulations in hydrogen-carbon system from crystal to amorphous. npj Comput Mater 11, 119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01629-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01629-y