Abstract

Floquet engineering provides a versatile platform for realizing and manipulating diverse exotic topological phases inaccessible in equilibrium. Under the irradiation of circularly or elliptically polarized light, the sizable spin-orbit couplings in group-IV Xene materials (e.g., silicene, germanene, stanene) lead to topological phase transitions (TPT) from quantum spin Hall (QSH) to quantum anomalous Hall (QAH) states, governed by spin-degeneracy broken with band closing and reopening process in one of the spin components. Fascinatingly, a large gapped (≥35 meV) QAH effect with a Chern number C = ± 2 can be introduced under a wide range of laser parameters, lifting limitations of conventional atomic building blocks to achieve long-range magnetism and enabling Chern-insulating behaviors above room temperature. A complex phase diagram for such TPTs is predicted. This work addresses transitions between two-dimensional QSH and QAH states via Floquet engineering, which will stimulate experimental realization of above-room-temperature QAH in group-IV Xenes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Floquet engineering of band structures under the irradiation of periodic light imports a prominent approach to achieving abundant novel topological phenomena1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The ability to continuously tune photon energy and laser intensity without inducing sample damage enables versatile manipulation of band structures, offering a promising platform for both theoretical investigations and experimental explorations. This method finds extensive use in modulating band topology. Examples include varying the type of semimetal phases in bulk black phosphorus4,5 and in ferromagnetic (FM) MnBi2Te46, opening the gapless Dirac cone in the surface state of three-dimensional topological insulators (TI)7, offering and manipulating effective mass terms in two-dimensional Chern insulators8, modulating concrete Chern numbers in monolayer magnets9,10, inducing anomalous Hall effect into graphene as demonstrated experimentally11, and beyond. Noteworthily, most of the above tunability is unavailable in topological materials in the ground state, manifesting Floquet engineering as a bright employment in freely pursuing novel topological characters.

Quantum anomalous Hall (QAH) effect is not an exception, which is expected to be manipulated by Floquet engineering9,19. As one of the most profound manifestations of band topology that can be directly verified via transport measurement, the QAH effect attracts numerous attentions in recent years20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Characterized by dissipationless spin-polarized edge states robust to impurity-related disturbances, the QAH state provides a multifunctional research platform for axion insulators, Majorana fermions, topological quantum computation, and topological magnetoelectric effects28,29,30,31,32. Great efforts have been spent to increase its working temperatures, i.e., by enhancing the magnetic critical temperatures24,25,28,29,33,34,35,36,37,38, and by enlarging the Chern-insulating gaps39,40,41,42. Despite significant efforts, the zero-field QAH conductance has only been experimentally realized at the highest temperature up to 1.4 K33 in the intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te46,29,30,32,33,34,35,39,41,42,43,44, highlighting the challenges in achieving higher-temperature operation. In the meantime, optimizing the global gaps in materials manifests a complicated designing dilemma due to the non-monotonic evolving performance of magnetic Zeeman splitting41,42. As discussed earlier, the non-equilibrium states excited by the periodic laser fields provide a powerful approach to achieve high-temperature QAH states, especially in those non-magnetic insulating materials without the limitation for intrinsic long-range magnetism. Floquet engineering of topological properties has been broadly investigated and discussed theoretically1,12,13,14,45,46,47,48,49, yet its advancement in realistic materials remains in a much slower pace2.

In this work, we systematically investigate the group-IV Xenes including silicene, germanene, and stanene, as prototypical two-dimensional (2D) materials to achieve topological phase transitions (TPT) between quantum spin Hall (QSH) and QAH states using circularly polarized light (CPL) or elliptically polarized light (EPL), via band closing-reopening process in one of the spin components. By fine-tuning laser parameters, the strength of spin-orbit coupling (SOC) governs the phase-transition conditions. For silicene and germanene, an exceptionally large global gap (≥35 meV) with the Chern number C = ±2 is easily achieved at a moderate laser intensity and a wide range of optical parameters. These effects are manifested by the zero-order bands reshaped by interacting with replica bands. Moreover, reversing the chirality of the light induces the reversal of Chern numbers. Our findings not only predict QSH-QAH phase transitions in the most widely studied two-dimensional (2D) group-IV Xene films50,51, but also provide a highly feasible and practical strategy for achieving above-room-temperature QAH states in experiment.

Results

Theoretical models and derivations

Crystallized as a hexagonal structure, group-IV (carbon-group) Xene possesses the simplest 2D structure but plentiful novel physics adjacent to their K(\({K}^{{\prime} }\)) valleys. Distinct from graphene that manifests a semi-metallic character, the sizable SOC strength in silicene, germanene, and stanene, plays a vital role in determining the electronic band gap at the K(\({K}^{{\prime} }\)) valley, rendering a QSH state (Z2 = 1), among all of which the time reversal symmetry T maintains. In the concept of Floquet engineering, the incidence of a polarized laser pulse may break time reversal symmetry T and govern the TPTs.

We first consider right-handed CPL (R-CPL) with the direction of incidence perpendicular to the film. We set the vector potential of laser field \({\boldsymbol{A}}={A}_{0}\left(\cos \omega t,{\bf{i}}\sin \omega t,0\right)\), where ω is the frequency of the light, t stands for the time. The ground state of the Dirac cone without including spin degree of freedom (i.e., two-band model) can be described as: \({H}_{{\rm{ground}}}({\boldsymbol{k}})=\hslash {v}_{{\rm{F}}}({k}_{x}{\sigma }_{x}+{k}_{y}{\sigma }_{y})\), where ℏ, vF and σx,y denote the reduced Planck constant, Fermi velocity, and Pauli matrices, respectively. The photon absorption and emission processes create multiple replica bands with infinite orders, and the Peierls substitution (\({\boldsymbol{k}}\to {\boldsymbol{k}}+\frac{e{\boldsymbol{A}}}{\hslash c}\), c is the velocity of light) involves laser field in the Hamiltonian. Only picking up the band-orders of − 1, 0 and 1, by setting \(\tilde{A}=\frac{{v}_{F}e{A}_{0}}{c}\) and ignoring the second-order interactions, the Floquet-Bloch theory provides the six-band Hamiltonian as:

Then, this Hamiltonian can either be solved straightforwardly by diagonalization or be analyzed approximately by Magnus expansion (\({H}_{{\rm{F}}}({\boldsymbol{k}})={H}_{0,0}({\boldsymbol{k}})+\frac{[{H}_{0,-1}({\boldsymbol{k}}),{H}_{0,1}({\boldsymbol{k}})]}{\hslash \omega }+O(\frac{1}{{\omega }^{2}})\))1,52,53. In the latter, the folding process into the two-band Hamiltonian of zero-order bands results in:

The second term in the right-hand side of Eq. (2) is the effective mass term induced by CPL, with η as +1 (− 1) for R-CPL (L-CPL). Further derivations provide the induced Chern number as +1 or − 1 under the irradiation of R-CPL or L-CPL, respectively. The amplitude (A0) and photon energy (E = ℏω) co-contribute to the final effective mass term (and thus the valley gap size): \(\tilde{m}\propto \frac{{A}_{0}^{2}}{\hslash \omega }\). Detailed theoretical derivations related to above results are shown in Supplementary Note 1. For computational process, we implement ten-order expansion of zero-order bands into the tight-binding Hamiltonian obtained from maximally localized Wannier function54,55,56, with more details expounded in Methods.

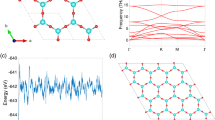

Considering the presence of sizable SOC effects, each band splits into two spin-resolved ones, thereby expanding the two-band model described in Eq. (2) into a more complex four-band model. Hence, in the QAH regime, the Chern number correspondingly doubles to either +2 or − 2. The valley-gap opening induced by SOC shifts the onset of QAH states to a finite value of A0, and the enhanced effective mass term initially compensates the gap under QSH regime, undergoes a TPT into a Chern-insulating state following a band gap closure, and subsequently exhibits a quadratic increase in the gap relative to A0. Figure 1 illustrates this QSH-QAH phase transition irradiated by R-CPL [red incident arrow depicted in Fig. 1b] and L-CPL [blue incident arrow depicted in Fig. 1c], one of chiral edge state reversing its chirality and aligning parallel to the other.

a Top view of monolayer Xenes with two opposite chirality of edge states, in which the red and blue square loops with opposite arrows stand for the chiral edge states with positive and negative chirality, respectively. b and c are corresponding to the conditions under the irradiation of R-CPL and L-CPL separately. In each subfigure, the large light-red and light-blue arrows located in the top-left corner stand for the incidence of R-CPL and L-CPL. The gray balls stand for Si, Ge, or Sn atoms.

Light-induced QSH-QAH Transition on Silicene

In the following, we mainly focus on the light-induced modifications of zero-order bands. First, for silicene, its weak SOC strength sustains a valley gap (1.4 meV) at ground state, requiring relatively weak laser-intensity to realize QAH states. Notably, the local density of state (LDOS) patterns projected onto the Y edge serve as the most direct method for edge state characterization and topological phase verification. Figure 2 displays the outcomes for silicene irradiated by R-CPL with SOC. Similarly, we also present the results without considering the spin degree of freedom in Supplementary Fig. 1.

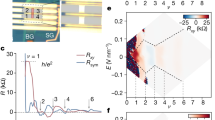

a shows the whole Brillouin-zone LDOS patterns of silicene under the irradiation of R-CPL with the laser-amplitude of 200 V/c. The two white horizontal dashed lines denote the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band of the 2D bulk phase, with the gap indicated as 147 meV. b–d denote zoom-in LDOS patterns around the K(\({K}^{{\prime} }\)) valleys with the laser amplitude varying as 0 V/c, 20 V/c, and 36 V/c sequentially, with the zoom-in zones encapsulated by yellow frames in subfigure a. In the center of d, the further zoom-in pattern exhibits the detailed nature of the edge state, corresponding to the yellow-dashed frame zone within the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap. The white vertical line separates LDOS patterns near the two valleys in each subfigure. The colors that from blue, white to red stand for the enhancement of LDOS values, while the red curves are edge states. e measures the AHC evolutions along with the energy level and the laser amplitude.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a–d, by projecting the 2D bulk states along with edge states onto the Y edge under the irradiation of R-CPL with ℏω = 1.0 eV, a graphene-like behavior is observed. This indicates a topological phase transition (TPT) from a semimetallic state (at 0 V/c) to a Chern insulator (at finite laser amplitude), where the Chern number is +1 in the latter phase. Adding back spin degree of freedom with SOC initiates almost no reformation into the aforementioned physical phenomena, except that the gapless point for TPT is shifted to 20 V/c [Fig. 2c]. In the QAH regime, the weak SOC strength of Si makes the two chiral edge states almost degenerate, with their distinction only becoming apparent in the further zoom-in local density of states (LDOS) pattern shown in the middle of Fig. 2d. AHC curves also verify the Chern number as +2 (\({\sigma }_{xy}=+\frac{2{e}^{2}}{\hslash }\)) [Fig. 2e], maintaining exceptional large global gaps under moderate laser amplitudes. With the photon energy fixed to 1.0 eV, quantum AHC plateau grows beyond 100 meV when A0 rises above 162 V/c. Markedly, the global gap of the whole system is distinctly determined by the energy gap at \(K({K}^{{\prime} })\) valleys at moderate laser amplitudes [see Fig. 2a].

Spin-resolved band structures of silicene (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicate that the illumination of CPL lifts the spin degeneracy, with the two valley gaps being determined by only one of the spin components. Germanene and stanene behaves similarly (Supplementary Fig. 3), amplifying the spin splitting as the laser intensity or SOC effect enhances. For silicene, within the QAH regime, an almost negligible valley-polarized nature is observed (Supplementary Fig. 4). This behavior is consistent with the characteristic that chiral edge states connect the valence band at the K valley to the conduction band at the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley [Fig. 2a]. Enhancing the laser amplitude to even a large regime (300–600 V/c) ruins the global gap of silicene, stemming from the band overlapping around the Γ point (Supplementary Fig. 5). Moreover, replacing R-CPL by L-CPL results in symmetric response characteristics while inducing a sign reversal of the Chern number to − 2 in the QAH phase (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). In contrast, linearly polarized light (LPL) fails to import effective mass term into the model after band renormalization (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Optical Phase Diagrams for Beyond-room-temperature Chern Insulators

Without the requirement of magnetization, the valley gaps (0 - 200 V/c) solely govern the working temperatures of the light-induced QAH state, with the inter-band mixing at other momentum effectively prevented. Figure 3 presents a comprehensive evolution of Chern numbers and valley gaps as a function of photon energy (ℏω), laser amplitude (A0), the eccentricity of polarized light (ϵ) and the incident angle (θ) in silicene. The following analysis further establishes the equivalent relationship among the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap, K valley gap and the global gap at moderate laser amplitudes. Hereinafter, we will refer to the evolution of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gaps as representative of both the valley and global gaps in the phase diagrams illustrated in Fig. 3e–h. Initially, selecting ℏω successively from 1.0 eV to 5.0 eV, we sequentially outline \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap developments in Fig. 3a and observe the zoom-in region of small-gap regime (0–10 meV) in Fig. 3b. All five characteristic curves demonstrate a consistent trend of an initial gap decrease, a gapless region, and a subsequent gap increase. Significantly, the increase in ℏω retards the critical threshold for the emergence of QAH state. In the QAH regime, the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap increases approximately quadratically with the laser amplitude, which corresponds to the effective mass term described in Eq. (2). Negligible difference can be observed between the two valley gaps [Fig. 3c], confirming the indistinguishable valley-degeneracy lifting induced by both the SOC effect and light illumination.

a \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap evolutions with various photon energies under the irradiation of R-CPL. b The zoom-in part of a within the black dashed frame shown in (a). c The comparison between \({K}^{{\prime} }\) (blue curve) and K (red curve) valley gaps evolving with the laser amplitude, depicted at ℏω = 1.0 eV and 2.0 eV. d The comparison of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gaps contributed by two separate spins (purple and olive curves) as a function of laser amplitude, depicted at ℏω = 1.0 eV and 2.0 eV. e Contour distributions of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap by varying the photon energy (along x axis) and the laser amplitude (along y axis) under the incident of R-CPL. The colors from blue, green, yellow to red, the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap increases, with the maroon region stands for the \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap above 35 meV. f exhibits the low-amplitude region of e (within the yellow frame, ≤ 50 V/c), in which the maroon region is related to the gap above 5 meV. The white dashed curve sitting in the center of the blue zone displays the QSH-QAH phase-transition boundary. The right-bottom (left-top) part divided by this boundary is denoted with “C = 0” ("C = + 2''). g Similar contour distributions of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap under the irradiation of right-handed EPL with various eccentricities (shown as ϵ2, along x axis). The maroon region stands for the gap above 5 meV. h Similar contour distributions of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap under the irradiation of R-CPL with various incident angles (θ, long x axis). The maroon region stands for the gap above 5 meV.

However, the evolution of energy gaps contributed by the two spin components exhibits an opposite trend: “spin 1” undergoes a band closing-reopening process, while “spin 2” monotonically increases without band closure [Fig. 3d]. The band of “spin 1” reverses its chirality after the band closure, resulting in a change of the Chern number from 0 to +2, consistent with the illustration in Fig. 1.

The presence of spatial inversion symmetry prohibits the breaking of valley degeneracy, which in turn limits the potential emergence of other Chern numbers. By choosing a vdW-layered substrate, spatial inversion symmetry is eliminated and the topological features are preserved (see Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). For instance, silicene grown on monolayer Sb2Se3 has the potential to create Chern numbers of ± 1 within a narrow range of light intensity. Furthermore, the illumination of multi-frequency light does not introduce additional Chern numbers, maintaining an immediate transition from 0 to ± 2, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 12.

To provide a more comprehensive view of the entire diagram, Fig. 3e illustrates the distribution of \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gaps as a function of ℏω (along the x axis) and A0 (along the y axis). The top-left region colored by maroon corresponds to gaps exceeding 35 meV, which is associated with an electronic excitation temperature of ≥406 K. Remarkably, for the lowest value of ℏω (0.2 eV), selecting a laser amplitude up to 200 V/c avoids any overlap with band states located at other momenta. Consequently, replacing this distribution with the global gap maintains its overall shape. These findings underscore the persistence of QAH states beyond room temperature across a broad range of laser field parameters.

Decreasing the laser vector potential to a regime below 50 V/c and the energy gap into 0–5 meV range, as encapsulated by a yellow frame in Fig. 3e, a zoom-in gap distribution is depicted in Fig. 3f. The gap values exceeding 5 meV also concentrate in the top left region. Meanwhile, a distinct blue zone, representing gaps near zero, appears around the white dashed curve indicated in Fig. 3f. This illustrates the evolution of the TPT point in relation to the photon energy, which follows a square-root relationship, aligning well with theoretical predictions [see Supplementary Fig. 13a]. It is intuitive to conclude that the left-top (right-bottom) part divided from the white dashed curve represents the Chern insulating (trivial insulating) phases with “C=+2” ("C=0”).

The eccentricity and the incident angle of the light are also critical factors. For right-handed EPL, its eccentricity is characterized by ϵ, offering the effective mass term as \(\Delta {M}^{{\prime} }=\sqrt{1-{\epsilon }^{2}}\Delta M\), in which ΔM is induced under the perpendicular irradiation of R-CPL. If ϵ is approached to 1 (0), \(\Delta {M}^{{\prime} }\) is approximated to 0 (ΔM), relating to the irradiation of LPL (R-CPL). Thus, the TPT points adhere to the relationship \({A}_{{\rm{TPT}}}\propto \frac{1}{\root{4}\of{1-{\epsilon }^{2}}}\), with the contour distributions illustrated in Fig. 3g, by substituting the photon energy with the square of the eccentricity (ϵ2). The TPT curve fits well with theoretical models [Supplementary Fig. 13b]. Analogously, varying the incident angle (θ) provides the effective mass term: \(\Delta {M}^{{\prime} }=\cos \theta \Delta M\) and the TPT point as: \({A}_{{\rm{TPT}}}\propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{\cos \theta }}\), with the contour distribution revealed in Fig. 3h. In like manner, the evolution of the TPTs aligns well with theoretical predictions [Supplementary Fig. 13c]. Notably, when the light is incident parallel to the sample (θ = 90°), no effective mass term is introduced, resulting in a completely fixed band structure. The parallel component of A adversely affects the phase modulation characteristics induced by light-matter interactions.

Similar behaviors of germanene and stanene

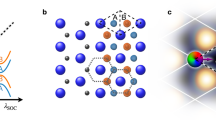

Exhibiting similar structures and electronic properties, Floquet engineering of germanene and stanene also demonstrates analogous behaviors. The enhancement of SOC strength in germanene and stanene makes the two chiral edge states significantly more distinguishable [Fig. 4a and f] compared to those in silicene. Markedly, the TPT points shift to higher laser amplitude as either the SOC strength or the photon energy increases. For stanene, the TPT point exceeds 300 V/c when the photon energy rises above 1.0 eV [Fig. 4b and g]. Akin to silicene, in germanene and stanene, the valley degeneracy lifting is minimal; however, the spin degeneracy is quickly broken, with the gap difference increasing as the laser intensity or SOC strength increases [Fig. 4c, d, h and i]. Germanene also exhibits remarkable characteristics as a large gapped Chern insulator, as indicated in the maroon zone (≥35 meV) of Fig. 4e, also characterized by Chern number as +2 [Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 14]. It’s Γ-point gap declines unhurriedly, same to that of silicene (Supplementary Fig. 15). Unfortunately, for stanene, the valence band at Γ point intrudes into the global gap before the TPT point is reached, undermining its potential for large gapped QAH state (Supplementary Fig. 16). The phase diagram displayed in Fig. 4j characterizes the evolution of QSH-QAH TPT points for stanene as a function of photon energy, but entirely obscured within metallic phase (gray-color zone) invaded by Γ-based valence states.

a LDOS pattern of germanene at the optical parameters of ℏω = 1.0 eV and A0 = 200 V/c. The zoomed-in pattern in the middle position highlights the comprehensive properties of the chiral edge state (encapsulated by yellow dashed frame at \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap). b \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley gap evolutions of germanene with various photon energies. The comparisons between the gaps of c two valleys, d two spins (at \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valley) of germanene evolving with the laser amplitude, depicted at ℏω = 1.0 eV. e Contour distribution of the global gaps by varying the photon energy (along x axis) and the laser amplitude (along y axis). The maroon region is related to the gaps above 35 meV. The white dashed curve performs as the QSH-QAH phase-transition boundary. f–j are similar to a–e, but for the condition of stanene. In (f), the laser amplitude is 280 V/c; in (j), gray region denotes the metallic phase.

Moreover, employing HSE06 functional57 instead of PBE58 verifies the robustness of all the aforementioned Floquet engineered topological phases, but with a larger ground-state gap of silicene (2.02 meV) and germanene (32.5 meV), and accordingly, a higher laser intensity of TPT point, concretely shown in Supplementary Figs. 17, 18.

Discussion

According to previous relative explorations, six cycles of periodic light facilitate Floquet engineering of bands4,59. We select the highest light frequency and intensity (ℏω = 4.0 eV, A0 = 200 V/c) from the phase diagram, which supports Chern insulating gaps exceeding 35 meV. Multiplying by six periods, the fluence amounts to approximately 0.013 J/cm2, which is significantly lower than the bond-damaging threshold of Si or Ge (0.050 J/cm2)60. Consequently, we expect that our optical parameters can avoid significant laser damage of the sample.

In this work, silicene and germanene exhibit remarkable potential for exceptional large-gapped (≥35meV), above room-temperature QAH states via Floquet engineering by CPL, manifesting the superiority compared to the previous building-blocks grown on magnetic substrates61,62,63,64. The irradiation of CPL or EPL, coupled with the SOC effect, induces a QSH-QAH TPT in silicene, germanene, and stanene, driven by the chirality-reversing within one of the spin components. Furthermore, an increase in eccentricity and incident angle negatively impacts the tunability described above, resulting in a retardment of TPT points toward a higher laser amplitude regime, and then, totally undermines the governability when the eccentricity achieves 1 (becoming LPL) or the incident angle arrives at 90° (parallel to the sample). Free from the constraints of complex traditional building blocks, Floquet engineering of the aforementioned group-IV Xenes offers the most practical and accessible pathway towards QAH-related novel quantum physics in the future.

Methods

Ground state computational details

Ground states of silicene, germanene and stanene were obtained via utilizing first-principle computational methods implemented by Vienna ab initio simulation (VASP)65, which is assisted by constructing a tight-binding Hamiltonian (TBH). For mesh grids of k points, 11 × 11 × 1 was adopted in relaxation and self-consistence computations of silicene, germanene and stanene. Among the above three group-IV Xenes, we adopted the criterion of structural optimization: Hellmann-Feynman force on each atom being smaller than 0.001 eV/Å. Similarly, for the electron energy convergence criterion, 1.0 × 10−7 eV was selected among relaxation, self-consistence and band structure computations. We mainly employed Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional to extract their ground states58, and prepared Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof (HSE)06-functional-based57 ground states to check the robustness of the outcomes mentioned in this work. For all four aforementioned systems, we added a vacuum layer of at least 15 Å to mimic two-dimensional behaviors66. Due to the monolayer structural nature, no van der Waals (vdW) correction was imposed. For the structural relaxation step, no SOC effect was involved; meanwhile, for self-consistence and band computation steps, the SOC effect was implemented.

Adding optical fields

In order to acquire the excited states illuminated by periodic optical fields, firstly, we applied Wannier90 package to build TBH of all the aforementioned three group-IV Xenes based on maximally localized Wannier function54,55,56. After obtaining ground-state TBHs, we implement our group-made code to execute Fourier transform into the reciprocal-lattice-based Hamiltonian, carrying out Peierls substitution4: \({\boldsymbol{k}}\,\to {\boldsymbol{k}}+\frac{e{\boldsymbol{A}}}{\hslash c}\), then made inverse Fourier transform to real-space-based Hamiltonian. We chose the value of equally divided points as 101 among one cycle for major investigations, and 51 for fast positioning of topological phase transition (TPT) points. In the code, we incorporated perturbations from higher-order side bands into the zero-order bands through a Magnus expansion approach4,52,53 up to ten orders:

After obtaining the Floquet engineered TBH, finally we adopted Green’s function method via WannierTools package67 to observe the topological feature of edge-states, Berry curvature distributions, anomalous Hall conductance (AHC) and Chern numbers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this work are available from the manuscript's main text and Supplementary Information. The additional data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The group-developed codes that implement the optical field are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The ground state computations have been performed by VASP, Wannier90, WannierTools and PHONOPY codes which can be requested from the corresponding developers.

References

Liu, H., Cao, H. & Meng, S. Floquet engineering of topological states in realistic quantum materials via light-matter interactions. Prog. Surf. Sci. 98, 100705 (2023).

Zhan, F. et al. Perspective: Floquet engineering topological states from effective models towards realistic materials. Quantum Front. 3, 21 (2024).

Bao, C., Tang, P., Sun, D. & Zhou, S. Light-induced emergent phenomena in 2d materials and topological materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 33–48 (2022).

Liu, H., Sun, J.-T., Cheng, C., Liu, F. & Meng, S. Photoinduced nonequilibrium topological states in strained black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 237403 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Pseudospin-selective floquet band engineering in black phosphorus. Nature 614, 75–80 (2023).

Fan, S. et al. Circularly polarized light irradiated ferromagnetic MnBi2Te4: A possible ideal Weyl semimetal. Phys. Rev. B 110, 125204 (2024).

Qin, F., Lee, C. H. & Chen, R. Light-induced half-quantized Hall effect and axion insulator. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075435 (2023).

Zhu, T., Wang, H. & Zhang, H. Floquet engineering of magnetic topological insulator mnbi 2 te 4 films. Phys. Rev. B 107, 085151 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Floquet engineering of the orbital Hall effect and valleytronics in two-dimensional topological magnets. Mater. Horiz. 11, 3819–3824 (2024).

Zhan, F. et al. Floquet engineering of nonequilibrium valley-polarized quantum anomalous Hall effect with tunable Chern number. Nano Lett. 23, 2166–2172 (2023).

McIver, J. W. et al. Light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 38–41 (2020).

Usaj, G., Perez-Piskunow, P. M., Foa Torres, L. E. F. & Balseiro, C. A. Irradiated graphene as a tunable floquet topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115423 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Floquet engineering of magnetism in topological insulator thin films. Electron. Struct. 5, 024002 (2023).

Vogl, M., Rodriguez-Vega, M., Flebus, B., MacDonald, A. H. & Fiete, G. A. Floquet engineering of topological transitions in a twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayer. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014310 (2021).

Ji, R. et al. Controllable Weyl nodes and Fermi arcs in a light-irradiated carbon allotrope. Phys. Rev. B 108, 205139 (2023).

Wan, X., Ning, Z., Xu, D.-H., Wang, R. & Zheng, B. Photoinduced high-chern-number quantum anomalous hall effect from higher-order topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 109, 085148 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Tunable topological states in stacked Chern insulator bilayers. Nano Lett. 23, 2839–2845 (2023).

Zhan, F. et al. Floquet valley-polarized quantum anomalous Hall state in nonmagnetic heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. B 105, L081115 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in nonmagnetic bismuth monolayer with a high Chern number. Materials Horizons (2025).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a quantum hall effect without landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the” parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988).

Yu, R. et al. Quantized anomalous Hall effect in magnetic topological insulators. Science 329, 61–64 (2010).

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Weng, H., Yu, R., Hu, X., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Quantum anomalous hall effect and related topological electronic states. Adv. Phys. 64, 227–282 (2015).

Mogi, M. et al. Magnetic modulation doping in topological insulators toward higher-temperature quantum anomalous Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107 (2015).

Ou, Y. et al. Enhancing the quantum anomalous Hall effect by magnetic codoping in a topological insulator. Adv. Mater. 30, 1703062 (2018).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

He, K., Wang, Y. & Xue, Q.-K. Topological materials: quantum anomalous Hall system. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 329–344 (2018).

Zhang, D. et al. Topological axion states in the magnetic insulator MnBi2Te4 with the quantized magnetoelectric effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 206401 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Robust axion insulator and Chern insulator phases in a two-dimensional antiferromagnetic topological insulator. Nat. Mater. 19, 522–527 (2020).

Tang, X.-Y. et al. Intrinsic and tunable quantum anomalous Hall effect and magnetic topological phases in XYBi2Te5. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075117 (2023).

Xu, Z., Duan, W. & Xu, Y. Controllable chirality and band gap of quantum anomalous hall insulators. Nano Lett. 23, 305–311 (2022).

Deng, Y. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator MnBi2Te4. Science 367, 895–900 (2020).

Ge, J. et al. High Chern number and high-temperature quantum Hall effect without Landau levels. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 1280–1287 (2020).

Gong, Y. et al. Experimental realization of an intrinsic magnetic topological insulator. Chin. Phys. Lett. 36, 076801 (2019).

You, J.-Y., Zhang, Z., Gu, B. & Su, G. Two-dimensional room-temperature ferromagnetic semiconductors with quantum anomalous hall effect. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 024063 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. High-temperature quantum anomalous Hall insulators in lithium-decorated iron-based superconductor materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 086401 (2020).

Li, Z., Han, Y. & Qiao, Z. Chern number tunable quantum anomalous hall effect in monolayer transitional metal oxides via manipulating magnetization orientation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 036801 (2022).

Otrokov, M. M. et al. Highly-ordered wide bandgap materials for quantized anomalous hall and magnetoelectric effects. 2D Mater. 4, 025082 (2017).

Grutter, A. & He, Q. Magnetic proximity effects in topological insulator heterostructures: Implementation and characterization. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 090301 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Realization of semimagnetic and magnetic topological insulators via topological surface states floating. Phys. Rev. B 109, 155427 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Universally optimizable strategy for magnetic gaps towards high-temperature quantum anomalous hall states via magnetic-insulator/topological-insulator building blocks. Phys. Rev. B 111, 075106 (2025).

Li, J. et al. Intrinsic magnetic topological insulators in van der Waals layered MnBi2Te4-family materials. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw5685 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Tunable interlayer magnetism and band topology in van der Waals heterostructures of MnBi2Te4-family materials. Phys. Rev. B 102, 081107 (2020).

Oka, T. & Kitamura, S. Floquet engineering of quantum materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 387–408 (2019).

Rudner, M. S. & Lindner, N. H. Band structure engineering and non-equilibrium dynamics in floquet topological insulators. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 229–244 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Theoretical understanding of photon spectroscopies in correlated materials in and out of equilibrium. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 312–323 (2018).

Giovannini, U. D. & Hübener, H. Floquet analysis of excitations in materials. J. Phys.: Mater. 3, 012001 (2020).

Rodriguez-Vega, M., Vogl, M. & Fiete, G. A. Low-frequency and Moiré–Floquet engineering: A review. Ann. Phys. 435, 168434 (2021).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801 (2005).

Molle, A. et al. Buckled two-dimensional xene sheets. Nat. Mater. 16, 163–169 (2017).

Bukov, M., D’Alessio, L. & Polkovnikov, A. Universal high-frequency behavior of periodically driven systems: from dynamical stabilization to floquet engineering. Adv. Phys. 64, 139–226 (2015).

Blanes, S., Casas, F., Oteo, J.-A. & Ros, J. The Magnus expansion and some of its applications. Phys. Rep. 470, 151–238 (2009).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Computer Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Qiu, G. et al. Ultrafast laser-shock-induced confined metaphase transformation for direct writing of black phosphorus thin films. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704405 (2018).

Sokolowski-Tinten, K. et al. Femtosecond x-ray measurement of ultrafast melting and large acoustic transients. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 225701 (2001).

Li, Z., Zhang, J., Hong, X., Feng, X. & He, K. Multimechanism quantum anomalous Hall and Chern number tunable states in germanene (silicene, stanene)/MBi2Te4 heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 109, 235132 (2024).

Xue, F. et al. Valley-dependent multiple quantum states and topological transitions in germanene-based ferromagnetic van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 109, 195147 (2024).

Yao, Y.-T., Xu, S.-Y. & Chang, T.-R. Atomic scale quantum anomalous Hall effect in monolayer graphene/MnBi2Te4 heterostructure. Mater. Horiz. 11, 3420–3426 (2024).

Hong, X. & Li, Z. Designing guidance for multiple valley-based topological states driven by magnetic substrates: Potential applications at high temperatures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04569 (2025).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Tkatchenko, A. & Scheffler, M. Accurate molecular van der Waals interactions from ground-state electron density and free-atom reference data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 073005 (2009).

Wu, Q., Zhang, S., Song, H.-F., Troyer, M. & Soluyanov, A. A. WannierTools: An open-source software package for novel topological materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 224, 405–416 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Hang Liu and Dr. Hui Zhou for helpful discussions, and Dr. Hang Liu for technical supports. The numerical calculations have been performed on the supercomputing system in the Huairou Materials Genome Platform. This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12025407 and No. 12450401), National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFA1400201), and Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. YSBR-047 and No. XDB33030100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. L. undertook the majority works of computations and data processing. H. C. and Z. L. built the basic theoretical models and derivations. S. M. made the chief guidance for this work and provided the Fund supporting. The paper was written by Z. L., H. C. and S. M. All authors contributed to the discussions and analyses of the data, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Cao, H. & Meng, S. Light-induced above-room-temperature Chern insulators in group-IV Xenes. npj Comput Mater 11, 160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01662-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01662-x