Abstract

Graph deep learning models, which incorporate a natural inductive bias for atomic structures, are of immense interest in materials science and chemistry. Here, we introduce the Materials Graph Library (MatGL), an open-source graph deep learning library for materials science and chemistry. Built on top of the popular Deep Graph Library (DGL) and Python Materials Genomics (Pymatgen) packages, MatGL is designed to be an extensible “batteries-included” library for developing advanced model architectures for materials property predictions and interatomic potentials. At present, MatGL has efficient implementations for both invariant and equivariant graph deep learning models, including the Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet), MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet), Crystal Hamiltonian Graph Network (CHGNet), TensorNet and SO3Net architectures. MatGL also provides several pre-trained foundation potentials (FPs) with coverage of the entire periodic table, and property prediction models for out-of-box usage, benchmarking and fine-tuning. Finally, MatGL integrates with PyTorch Lightning to enable efficient model training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful new tool in the materials scientist’s toolkit1,2,3,4. Sophisticated ML models have found their way into a multitude of applications. Surrogate ML models for “instant” predictions of properties such as formation energies, band gaps, mechanical properties, etc.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 have greatly expanded our ability to explore vast chemical spaces for new materials. In addition, Machine learning (ML) has been widely used for parameterizing potential energy surfaces (PESs)14,15,16, enabling the direct prediction of potential energies, forces, and stresses based on atomic positions and chemical species. These ML interatomic potentials (MLIPs)17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 have provided us with the means to parameterize complex PESs to perform large-scale atomistic simulations with unprecedented accuracies.

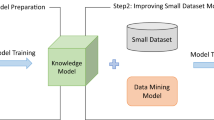

Among ML model architectures, graph deep learning models, also known as graph neural networks (GNNs), utilize a natural representation that incorporates a physically intuitive inductive bias for a collection of atoms28. Figure 1 depicts a typical graph deep learning architecture. In the graph representation, the atoms are nodes and the bonds between atoms (usually defined based on a cutoff radius) are edges. In most implementations, each node is represented by a learned embedding vector for each unique atom type (element). Additionally, some architectures such as the MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet)5 and Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet)29 also include an optional global state feature (u) to provide greater expressive power, for instance, in the handling of multifidelity data30,31. A graph deep learning model is constructed by performing a sequence of update operations, also known as message passing or graph convolutions. In the final layer, the embeddings are pooled and passed through a final MLP layer to arrive at a final prediction. GNNs can be broadly divided into two classes in terms of how they incorporate symmetry constraints. Invariant GNNs use scalar features such as bond distances and angles to describe the structure, ensuring that the predicted properties remain unchanged with respect to translation, rotation, and permutation. Equivariant GNNs, on the other hand, go one step further by ensuring that the transformation of tensorial properties, such as forces, dipole moments, etc. with respect to rotations are properly handled, thereby allowing the use of directional information extracted from relative bond vectors. For a comprehensive overview of different GNN architectures and their applications, readers are referred to recent literature32,33. Given sufficient training data, GNN architectures such as Nequip34, MACE35, Equiformer36 and many others37,38,39 have been shown to provide state-of-the-art accuracies in the prediction of various properties and PESs5,40,41,42. Furthermore, unlike other MLIP architectures based on local-environment descriptors, GNNs have a distinct advantage in the representation of chemically complex systems. The recent emergence of foundation potentials (FPs)29,43,44,45,46,47, i.e., universal MLIPs with coverage of the entire periodic table of elements, is a particularly effective demonstration of the ability of GNNs to handle diverse chemistries and structures.

Vn and En denotes the set of node/atom ({vi}) and edge/bond features ({eij}), respectively, in the nth layer. Some implementations include a global state feature (U) for greater expressive power. Between layers, a sequence of edge (fE), node (fV) and state (fU) update operations are performed. fE, fV and fU are usually modeled using multilayer perceptrons. In the final step, the edges, nodes and state features are pooled (P) and passed through a multilayer perceptron to arrive at a prediction.

At the time of writing, most software implementations of materials GNNs48,49,50 are for a single architecture, built on PyTorch-Geometric51, Tensorflow52 or JAX53. However, recent benchmarks show that the Deep Graph Library (DGL)54 outperforms PyTorch-Geometric in terms of memory efficiency and speed, particularly when training large graphs under the same GNN architectures for various benchmarks54,55. This improved efficiency enables the training of models with larger batch sizes as well as the performance of large-size and long-time-scale simulations.

In this work, we introduce the Materials Graph Library (MatGL), an open-source modular, extensible graph deep learning library for materials science. MatGL is built on DGL, Pytorch and the popular Python Materials Genomics (Pymatgen)56 and Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)57 materials software libraries. MatGL provides a user-friendly workflow for training property models and MLIPs, with data pipelines and Pytorch Lightning training modules designed for the unique needs of materials science. In its present version, MatGL provides implementations of several state-of-the-art invariant and equivariant GNN architectures, including the Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet)29, MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet)5, Crystal Hamiltonian Graph Neural Network (CHGNet)43, TensorNet58 and SO3Net49, as well as pre-trained FPs and property models based on these architectures. To facilitate the use of pre-trained FPs in atomistic simulations, MatGL also implements interfaces to widely used simulation packages such as the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) and the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE). The intent for MatGL to serve as a common platform for the scientific community to collaboratively advance graph deep learning architectures and models for materials science.

Results

In the following sections, we present the MatGL framework, with the manuscript organized as follows: We start with a schematic overview of the core model components, followed by a concise summary of the data pipeline and preprocessing steps. We then introduce the available graph neural network (GNN) architectures for property prediction and the construction of MLIPs. Next, we detail the key components involved in training and deploying these architectures, explaining their integration into MatGL. Additionally, we introduce the simulation interfaces for atomistic simulations and the command-line interface for various applications. Finally, we demonstrate the performance of different GNN architectures on widely used datasets, encompassing both molecular and periodic systems.

MatGL architecture

MatGL is organized around four components: data pipeline, model architectures, model training and simulation interfaces. Figure 2 gives an overview of MatGL architecture, and detailed descriptions of each component are provided in the following paragraphs.

Class names are in italics. MatGL can be broken down into four main components: 1. the data pipeline component preprocesses a set of raw data into graphs and labels; 2. the architecture component build the GNN model using modular layers implemented; 3. the training component utilizes PyTorch Lightning to train either property models or MLIPs; and 4. the simulation components integrates the MatGL models with atomistic packages such as ASE and LAMMPS to perform molecular dynamics simulations.

The first core component introduced is the data pipeline and preprocessing. The MatGL data pipeline consists primarily of MGLDataset, a subclass of DGLDataset, and MGLDataLoader, a wrapper around DGL’s GraphDataLoader. MGLDataset is used for processing, loading and saving materials graph data, and includes tools to easily convert Pymatgen Structure or Molecule objects into directed or undirected graphs, while MGLDataLoader batches a set of preprocessed inputs with customized collate functions for training and evaluation. The main features of MGLDataset and MGLDataLoader are summarized below.

An important feature of MGLDataset is to provide a pipeline for processing graphs from inputs, loading and saving DGL graphs and labels. The commonly used inputs consist of the following items:

-

structures: A set of Pymatgen Structure or Molecule objects.

-

converter: A graph converter that transforms a configuration into a DGL graph.

-

cutoff: A cutoff radius that defines a bond between two atoms.

-

labels: A list of target properties used for training.

Other inputs such as global state attributes and a cutoff radius for three-body interactions are optional depending on the model architecture and applications. The default units for PES properties are Å for distance, eV for energy, eV Å−1 for force, and GPa for stress. MGLDataset also includes the ability to cache pre-processed graphs, which can facilitate the reuse of data for the training of different models. Once the MGLDataset is successfully loaded or constructed, the dataset can be randomly split into the training, validation, and testing sets using the DGL split_dataset method. MGLDataLoader is then used to batch the separated training, validation and optional testing sets for either training or evaluation via PL modules.

Another core component is the set of GNN architectures implemented in the matgl.models package, using different layers implemented in the matgl.layers package. The models and layers are all subclasses of torch.nn.Module, which offers forward and backward functions for inference and calculation of the gradient of the outputs with respect to the inputs via the autograd function. Different models will utilize different combinations of layers, but, where possible, layers are implemented in a modular manner such that they are usable across different models (e.g., the MLP layer implementing a simple feed-forward neural network). MatGL offers various pooling operations, including set2set59, average, and weighted average, to combine atomic, edge, and global state features into a structure-wise feature vector for predicting intensive properties. The pooled structural feature vector is then passed through an MLP for regression tasks, while a sigmoid function is applied to the output for classification tasks.

Table 1 summarizes the GNN models currently implemented in MatGL. The details of the models were already comprehensively described in the provided references, and interested readers are referred to those works. It should be noted that this is merely an initial set of model implementations. In addition, all MatGL models subclass the MatGLModel abstract base class, which specifies that all models should implement a convenience predict_structure method that takes in a Pymatgen Structure/Molecule and returns a prediction.

A key assumption in MLIPs is that the total energy can be expressed as the sum of atomic contributions. For PES models, the graph-convoluted atomic features are fed into either gated or equivariant gated multilayer perceptrons to predict the atomic energies. In addition, we have implemented a Potential class in the matgl.apps.pes package that acts as a wrapper to handle MLIP-related operations. For instance, a best practice for MLIPs is to first carry out a scaling of the total energies, for example, by computing either the formation energy or cohesive energy using the energies of the elemental ground state or isolated atom, respectively, as the zero reference. The Potential class takes care of accounting for the normalization factor in the total energies, as well as computing the gradient to obtain the forces, stresses and hessians. Other atomic properties such as magnetic moments and partial charges can also be predicted at the same time with the Potential class.

For the training module, MatGL leverages the PL framework, which supports different efficient parallelization schemes and a variety of hardware including CPUs, GPUs and TPUs. MatGL provides two different PL modules including ModelLightningModule and PotentialLightningModule for property model and PES model training, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the training workflow for building property models and MLIPs in MatGL. A set of reference calculations including structures and target properties is generated using ab initio methods and experiments. The reference structures are converted into a list of Pymatgen Structure/ Molecule objects, and target properties are stored in a dictionary, where the property names are the keys and corresponding values denote items. These inputs are passed through MGLDataset, followed by splitting the dataset into training, validation, and optional test sets, and then MGLDataLoader to obtain batched graphs, stacked state attributes, and labels. The desired GNN model architecture is initialized with requisite settings such as the number of radial basis functions, cutoff radii, etc. Various algorithms such as Glorot60 and Kaiming61 implemented in Pytorch can also be used to initialize the learnable parameters in GNNs. The PL training framework includes two modules: PotentialLightningModule and ModelLightningModule. The primary difference between them lies in their respective loss functions. In ModelLightningModule, the loss is defined solely as the error between the predicted and target structural properties. In contrast, PotentialLightningModule uses a weighted sum of errors across various PES properties, such as energies, forces, and stresses. It can also optionally include other atomic properties that influence the PES, such as magnetic moments and charges.

The initial raw data includes a list of Pymatgen Structure/Molecule objects, optional global state attributes and labels such as structure-wise and PES properties. These inputs are used to preprocess training, validation and optional test sets containing a tuple of DGL graphs, labels, optional line graphs and state attributes using MGLDataset. These datasets are then fed into MGLDataLoader to create the batched inputs including graphs, state attributes and labels for training and validation. The GNN architecture is initialized with chosen hyperparameters and passed as inputs to PL training modules with training and validation data loaders.

As for performing molecular simulations, MatGL currently provides interfaces to the Atomistic Simulation Environment (ASE) and Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) to perform simulations with Potential models, i.e., MLIPs. For ASE, a PESCalculator class, initialized using a Potential class and state attributes, calculates energies, forces, stresses, and other atomic properties such as magnetic moments and charges for an ASE Atoms object, with the necessary conversion into DGL graphs being handled within the class itself. In addition, a Relaxer class allows users to perform structural optimization with different settings such as optimization algorithms (e.g. FIRE62, BFGS63,64 and Gaussian process minimizer (GPMin)65) and variable cell relaxation for both Pymatgen Structure/Molecule and ASE Atoms objects. Finally, a MolecularDynamics class makes it easy to perform MD simulations under different ensembles with various thermostats such as Berendsen66, Andersen67, Langevin68 and Nosé-Hoover69,70. Additional functionality to compute material properties such as elasticity, phonon analysis and finding minimum energy paths using PESCalculator are available in the MatCalc71 package. An interface to LAMMPS has also been implemented by AdvanceSoft, which utilizes PESCalculator to provide PES predictions for simulations. This interface enables the use of MatGL for a wide range of simulations supported by LAMMPS, including replica exchange72 and grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC)73, etc.

Finally, MatGL offers a command-line interface (CLI) for performing a variety of tasks including model training, evaluation and atomistic simulations. This interface minimizes the user’s effort and time in preparing scripts to run calculations such as property prediction, geometry relaxation, MD, model training, and evaluation.

-

matgl predict. This command is used to perform structure-wise property prediction, such as formation energy and band gap of materials. The prediction requires at least a structure file that can be read using the Structure.from_file method from Pymatgen and a directory that stores the trained property model. Additionally, predictions for multiple structure-wise properties are also supported.

-

matgl relax. This command is used to perform geometry relaxation using the Relaxer class with a trained MLIP. Users can flexibly decide whether to perform variable-cell relaxation and can adjust the maximum allowable force components to define the relaxation criteria. The default optimizer is the FIRE algorithm62, although other optimization algorithms are also available.

-

matgl md. This command is used to perform MD simulations using the MolecularDynamics class. Similar to matgl relax, it also requires a structure and a trained MLIP. Users can customize various simulation parameters, including the step size, ensemble type, number of time steps, target pressure, and temperature. Furthermore, ensemble-dependent settings such as collision probability, external stress, and coupling constants for thermostats can be also adjusted to specific systems.

-

matgl train and matgl evaluate. These commands are used to perform model training and evaluation, including data preprocessing, splitting, setting up the GNN architecture, and configuring Lightning modules. Users only need to provide an input file containing structures and their corresponding target properties, along with the settings for graph construction, GNN architecture, and training hyperparameters. These settings can be modified in the configuration file or specified as input arguments.

Property benchmarks

In the following paragraphs, we benchmark the performance of different GNN architectures, trained on various popular datasets, in terms of accuracy and inference time.

We first compared the performance of various GNN architectures for predicting various properties of the QM9 molecular74 and Matbench bulk crystal75 datasets. The QM9 dataset contains 130,831 organic molecules including H, C, N, O and F. GNN models were trained on the isotropic polarizability (α), free energy (G) and the gap (Δϵ) between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which were computed with DFT with the B3LYP functional.

Table 2 shows the MAE of different GNN architectures. Consistent with previous analyses, MEGNet obtains the highest errors, while other models are comparable. For example, MEGNet achieves validation and test MAEs of 0.037 eV for free energy, while other models reach a range of 0.025–0.027 eV. It should be noted that these experiments aim to demonstrate the capabilities of MatGL with consistent settings. For comparing the best accuracy between different architectures, an extensive search for preprocessing treatments of target properties and hyperparameters, such as learning rate, scheduler, and weight initialization, is required.

For Matbench dataset, we trained four different GNNs on three properties: formation energy (Eform), Voigt-Reuss-Hill bulk modulus (log(Kvrh)), and shear modulus (log(Gvrh)). The datasets contained 132,752, 10,987, and 10,987 crystals, respectively, resulting in a total of 12 property models.

Table 3 reports the MAEs of material properties including formation energy, bulk/shear modulus and bandgap with respect to reference DFT-PBE results. All GNN models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in terms of training, validation and test errors74,76. MEGNet generally obtains the highest MAEs compared to other models. For instance, the calculated validation and test MAEs of MEGNet for formation energy are 0.037 eV atom−1, while other models significantly reduce the error by 40%. The poor performance of MEGNet is attributed to the less informative geometric representation of structures based only on bond distances. Recent studies77 find that distance-only GNNs fail to uniquely distinguish atomic environments, which affects the accuracy of structure-wise properties due to degeneracies caused by the incompleteness of representation. Other models like M3GNet, TensorNet and SO3Net achieve considerably higher accuracy by taking additional geometric information, such as bond angles and relative position vectors, into account. The learning curves for QM9 and Matbench are provided in Supplementary Figs. S1, S2.

We also evaluate the efficiency of different GNNs for property prediction. Table 4 shows the inference time of the test set for the QM9 and Matbench datasets for the different GNN models. MEGNet achieves the shortest inference time with 12 s and 11 s for around 6500 small molecules and crystals although the accuracy is the worst. TensorNet generally achieves the best compromise between accuracy and efficiency, taking less than 15 s for both datasets. M3GNet and SO3Net has the longest inference time for molecules and crystals, respectively. This shows that the SO3Net is slower than M3GNet when the number of neighbors within a spatial cutoff sphere is larger.

PES benchmarks

The following paragraphs summarize the performance of various GNN model architectures in constructing MLIPs using popular large databases such as the ANI-1x78, MPF-2021.2.8 and the recently release Materials Potential Energy Surface (MatPES) dataset v2025.179. The results and benchmarks are presented below.

The first benchmark dataset is ANI-1x78, which contains roughly 5 million conformers generated from 57,000 distinct molecules containing H, C, N, and O for constructing general-purpose organic molecular MLIPs. We also included the Transfer-Learning M3GNet (M3GNet-TL) MLIPs from the pre-training ANI-1xnr dataset80 by adapting the pretrained embedded layer and only optimizing other model parameters for comparison. We noted that the ANI-1xnr dataset encompasses a significantly larger configuration space compared to ANI-1x, owing to the extensive structural diversity obtained from condensed-phase reactions. These reactions include carbon solid-phase nucleation, graphene ring formation from acetylene, biofuel additive reactions, methane combustion, and the spontaneous formation of glycine from early earth small molecules.

Table 5 shows the MAEs of energies and forces computed with different GNNs with respect to DFT. Both M3GNet and TensorNet achieve comparable training and validation MAEs of energies and forces, while SO3Net significantly outperforms them. A similar conclusion can be drawn from the test errors showing that SO3Net achieves the lowest MAE in terms of energies and forces.

The results are consistent with previous findings, indicating that equivariant models are typically more accurate and transferable than invariant models for molecular systems. Moreover, M3GNet-TL reduces the errors in energies and forces by 10–15% compared to M3GNet trained from scratch and also exhibits significantly faster convergence, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The improvements are attributed to the pre-trained embedded layer from ANI-1xnr dataset that covers a greater diversity of local atomic environments.

To further evaluate the extrapolation abilities of GNN models, we compare the energies and forces on the molecules obtained from COMP6 benchmarks with respect to DFT. Figure 4 shows the MAE of energies and forces computed with M3GNet, M3GNet-TL, TensorNet and SO3Net. Both M3GNet and M3GNet-TL perform the worst in terms of energy and force errors above 14 meV atom−1 and 0.14 eV Å−1 on the ANI-MD dataset, which comprises molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories of 14 well-known drug molecules and 2 small proteins. The large errors may be attributed to the poor transferability of MLIPs trained on small molecules to larger ones, as the largest molecule in the training set contains 63 atoms, whereas the molecules in the ANI-MD dataset have 312 atoms. The TensorNet significantly reduces the error of energies and forces to 11 meV atom−1 and 0.1 eV Å−1, while SO3Net further reduces to 2.3 meV atom−1 and 0.044 eV Å−1. This trend can be also found in other benchmark datasets.

To further demonstrate the performance of constructed MLIPs from MatGL with state-of-the-art models, we calculated the energy of two well-known molecules with respect to the dihedral torsion. Figure 5a shows the PES of ethane during torsion. All MLIPs, including reference ANI-1x78 and MACE-Large81, predict the same torsion angles for the maxima and minima of the PESs, while the energy barriers are slightly different. For instance, both ANI-1x and M3GNet predict a higher energy barrier of 0.15 eV, whereas MACE-Large obtains 0.125 eV. SO3Net and TensorNet predict the lowest energy barrier of 0.1 eV. For the case of a more complex di-methyl-benzamide molecule, all the MLIPs provide a similar shape of PESs with respect to different dihedral angles. Still, the predicted barrier heights are different. For example, the ANI-1x model has the largest barrier height of 1.5 eV at 180∘, while both TensorNet and M3GNet considerably underestimate the energy barrier by 0.6 eV. The energy barriers for SO3Net, and MACE-Large range from 0.9 to 1.2 eV.

The second dataset is the manually selected subset of MPF.2021.2.8., which contains all geometry relaxation trajectories from both the first and second step calculations in the Materials Project. The total number of crystal structures is 185,877. Moreover, the isolated atoms of 89 elements were also included in the training set to improve the extrapolability of the final potential. The details of data generation and selection can be found in ref. 82. Here we excluded SO3Net from the benchmarks due to its relatively high sensitivity to noisy datasets, which led to extremely large fluctuations in training errors.

Table 6 shows that CHGNet generally outperforms M3GNet and is noticeably better than TensorNet in terms of energies, forces and stresses. The convergence of validation loss and PES properties was plotted in Supplementary Fig. S4. This can be attributed to the fact that the CHGNet provides additional message passing between angles and edges compared to M3GNet. Moreover, the DFT calculation settings, such as electronic convergence and grid density in reciprocal space, are less strict, resulting in large numerical noise in forces and stresses, which makes the training particularly challenging for equivariant models that are very sensitive to these properties. Furthermore, most structures are crystals without complicated structural diversity, which reduces the strength of equivariant models by providing a more informative representation of complex atomic environments. More detailed benchmarks on structurally diverse datasets with stricter electronic convergence for constructing general-purpose FPs are required in future studies.’ We also performed benchmarks on crystals, particularly focusing on binary systems obtained from the Materials Project database.

The first step is to investigate the performance of GNNs on the geometry relaxation of binary crystals and corresponding energies with respect to DFT. It should be noted that such benchmarks for existing FPs have been reported in recent studies83,84. Figure 6a shows the cumulative structural fingerprint distance between DFT and MLIP relaxed structures using CrystalNN algorithm85, which indicates the similarity between the two structures based on the local atomic environments. Overall, both M3GNet and TensorNet have similar performance in terms of fingerprint distance. CHGNet only shows a modest improvement, with more structures within a distance of about 0.01 compared to M3GNet and TensorNet. Figure 6b shows the cumulative absolute energy errors of MLIPs with respect to DFT. CHGNet predicts that about 60% of structures have an energy difference below 25 meV atom−1. This is comparable to M3GNet and 10% better than TensorNet.

We also compared the predicted bulk modulus with different models. Figure 7 shows the parity plots of bulk modulus computed with FPs and DFT. All models have similar R2 scores and MAEs, reaching 0.8 and 20 GPa. Finally, we computed the heat capacity of binary systems at 300K under phonon harmonic approximation and compared the results with DFT reference data at the PBEsol level obtained from Phonondb. Figure 8 shows that all models are in very good agreement with DFT. A very recent study86 noted a small shift between PBE and PBE-sol on the prediction of phonon properties. Nevertheless, these benchmarks demonstrate that our trained MLIPs can provide a preliminary reliable prediction on material properties by performing geometry relaxations and phonons. These FPs can perform reasonably stable MD simulations across a wide range of systems at low temperatures, as their covered configuration space partially overlaps with relaxation trajectories near the equilibrium region29,43,87.

We have also conducted additional benchmarks of TensorNet trained on the recently developed MatPES dataset79. Here, we are using only the FPs trained on MatPES PBE data only (TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1). These benchmarks include surface energies, vibrational entropies, phonon dispersions, and the structural properties of amorphous materials. These properties are generally derived from structures that are not within the training dataset.

Figure 9 shows the surface energies of fcc Cu and bcc Mo predicted by different MLIPs. The TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 predictions are in excellent agreement with DFT (mostly within 0.1 Jm−2). The custom qSNAP MLIPs88 perform well for fcc Cu surface energies, but exhibit a consistent underestimation of the Mo surface energies. The TensorNet-MPF performs significantly worse for both systems and does not reproduce even the qualitative trends in surface energies between different Miller indices for Mo. This is likely due to well-known deficiencies in the MPF training dataset as discussed by Kaplan et al.79. Figure 10 shows the calculated phonon dispersion and vibration entropy as a function of temperature for silicon (Materials Project ID: mp-149) and gallium oxide (Materials Project ID: mp-1243) from DFT, TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 and custom SNAP and GAP MLIPs. TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 also shows good agreement with DFT and custom MLIPs, including SNAP88 and GAP89. Finally, the structural properties of amorphous Li3PS4 were calculated using TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 and the custom DeepMD potential90. Figure 11 shows that TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 generally agrees with DeepMD in terms of the peak positions of the RDF. The small differences in magnitude may be attributed to the additional Grimme D3 dispersion correction91 and the use of different pseudopotentials. Overall, the above extended benchmarks illustrate that the FPs can be used to study various material properties with reasonably good accuracy.

Radial distribution functions computed with a DeepMD and b TensorNet-MatPES-PBE-v2025.1. The DeepMD data is token from ref. 90.

The reliability of material properties extracted from MD simulations critically depends on the accuracy of trained MLIPs92,93. MatGL provides ASE and LAMMPS interfaces to perform MD simulations, enabling the benchmarking of different GNN architectures42,94. In addition to the accuracy of GNNs, computational efficiency is crucial for large-scale atomistic simulations. We used the above MLIPs to perform MD simulations with 1000 timesteps for scalability tests with a single GPU via ASE and LAMMPS interfaces. Figure 12a shows the computational time for NVT simulations of non-periodic water clusters using ASE, with increasing sizes from 15 to 2892 atoms. SO3Net becomes significantly more demanding than TensorNet and M3GNet when simulating clusters with more than 100 atoms. TensorNet is the most efficient for all cases compared to M3GNet and SO3Net due to its model architecture, which does not require costly three-body calculations and tensor products. With a more scalable and optimized LAMMPS interface, Fig. 12b shows the computational time of NPT simulations for silicon diamond supercells ranging from 8 to 5832 atoms, where each Si atom contains around 70 neighbors within a spatial cutoff of 5 Å. CHGNet achieves the shortest computational time, while the computational cost of M3GNet is the highest. This is likely due to the additional cost of a larger cutoff for counting triplets and three-body interactions. These models can already serve as a “foundation" model for preliminary calculations with reasonably good accuracy. Moreover, building customized MLIPs often requires extensive AIMD simulations to sample the snapshots from the trajectories for training. Such demanding AIMD simulations can be replaced by the FPs with considerably reduced costs82.

Discussion

Graph deep learning has made tremendous progress in atomistic simulations. Here we have implemented MatGL, which covers four major components including data pipelines, state-of-the-art graph deep learning architectures, Pytorch-Lightning training modules, interfaces with atomistic simulation packages, and command-line interfaces.

We also provided detailed documentation and examples to help users become familiar with training their custom models and conducting simulations using ASE and LAMMPS packages in our public Github repository. In addition, we provided several pretrained property prediction models and FPs, which can be used out-of-the-box for organic molecules and materials. With the combination of excellent chemical scalability and large databases, these models empower users to perform simulations across a wide range of applications, speeding up materials discovery by enabling high-throughput screening of hypothetical materials across a large chemical space95,96,97,98. Moreover, users can efficiently train their customized models with significantly faster convergence through fine-tuning from our available pretrained models. For example, our recently developed Dimensionality-Reduced Encoded Clusters with sTratified (DIRECT) sampling method significantly reduces the number of training structures required to cover large configuration spaces generated by high-throughput MD simulations using FPs82. In the GitHub repository, we have provided Jupyter notebook tutorials on fine-tuning FPs for target applications. This fine-tuning procedure can be adapted and combined with high-throughput automation frameworks such as atomate99 for active learning where necessary. Additionally, MatGL allows developers to design their own graph deep learning architectures and benchmark their performance with minimum effort, complimented by the modules available in the library. MatGL has been integrated into various frameworks, including MatSciML100 and the Amsterdam Modeling Suite101, expanding access for researchers in materials science and chemistry to conduct computational studies on a wide range of materials using GNNs. In future work, the efficiency of MLIPs can be further enhanced by integrating multi-GPU support with efficient parallelization algorithms44. Besides, training on massive databases exceeding millions of structures may encounter bottlenecks due to the memory needed to store all graphs and labels. To address this, the lightning memory-mapped database can be utilized to manage such large-scale training with affordable computational resources. Relevant tools for constructing reliable and robust MLIPs-such as uncertainty quantification102,103, active learning workflows104,105, and model interpretability106,107-will also be integrated into MatGL in the near future. We expect that the upcoming version of MatGL will substantially increase the accessible training set size for constructing FPs and enhance the efficiency of large-scale MD simulations, enabling the study of many interesting phenomena in materials science and chemistry.

Methods

Model training

All models were trained using PotentialLightningModule for structure-wise properties and ModelLightningModule for potential energy surfaces (PESs). The optimizer was chosen to be the AMSGrad variant of AdamW with a learning rate of 10−3. The weight decay coefficient was set to 10−5. The cosine annealing scheduler was used to adjust the learning rate during the training. The maximum number of iterations and minimum learning rate were set to 104 and 10−5, respectively. The mean absolute error of predicted and target properties was selected to calculate the loss function. The additional relative importance of energies, forces and stresses (1:1:0.1) was introduced for PES training. The maximum number of epochs was set to 1000, and early stopping was achieved with the patience of 500 epochs. The gradient for model weight updates was accumulated over 4 batches, and the gradient clipping threshold to prevent gradient explosion was set to 2.0. The input settings for the data loaders are listed in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and a complete set of hyperparameters for each model and training module is provided in Supplementary Tables S3–S7. For detailed descriptions of all models, the interested readers are referred to the respective publications.

Benchmark details

For dihedral torsion, the initial structures of ethane and dimethylbenzamide were relaxed using the FIRE algorithm with molecular MLIPs under a stricter force threshold of 0.01 eV Å−1. The conformers for scanning the dihedral angles were generated using RDKit108 at 1∘ intervals, resulting in a total of 359 single-point calculations to produce the PES. As for benchmarks on geometry relaxation, the 20160 initial DFT-relaxed binary crystals were taken from the Materials Project database. All these structures were re-optimized using FPs with variable cell geometry relaxation within a lighter force threshold of 0.05 eV Å-1. The default settings for CrystalNN were employed to measure the similarity between the DFT and MLIP-relaxed structures based on the fingerprints of their local environments. It should be noted that two structures failed during relaxation with CHGNet due to the failed construction of bond graphs caused by unphysical configurations. To benchmark Voigt-Reuss-Hill bulk modulus and heat capacity, a total of 4653 and 1183 binary crystals with available Voigt-Reuss-Hill bulk modulus and heat capacity data were obtained from the Materials Project and PhononDB, respectively. Additional filters were applied to unconverged DFT calculations and unphysical bulk modulus and the remaining 3576 structures finally were analyzed. As for heat capacity, 1183 binary crystals were compared. All predicted properties derived from MLIPs were calculated using ElasticityCalc and PhononCalc from the MatCalc library. The default settings were used, except for a stricter force convergence threshold of 0.05 eV Å-1. Notably, all phonon calculations were completed successfully with the lighter symmetry search tolerance set to 0.1. The surface energy is defined as

where Eslab and Ebulk denotes the surface energy with an exposed (hkl) plane and energy of the bulk structure, respectively. Aslab refers to the cross-sectional area of the slab. The fcc Cu and bcc Mo surfaces were included in this benchmark. All surface and bulk structures were obtained from Materials Project. Only atomic positions were relaxed using MLIPs with the force threshold of 0.01 eV Å−1 and then the relaxed structures were used to calculate the energies. The vibrational entropy and phonon dispersion were calculated using MatCalc interfaced with Phonopy. Silicon in the diamond structure (Materials Project ID: mp-149) and gallium oxide (Materials Project ID: mp-1243) were selected as test systems. The initial structures were relaxed using a stricter force convergence threshold of 0.0001 eV Å−1. Atomic displacements of 0.01 Å were applied to compute the force constants. A 20 × 20 × 20 mesh was used for phonon calculations, with all other settings kept at their default values in MatCalc. Finally, an amorphous structure of Li3PS4 was generated using a melt-and-quench protocol, following the methodology outlined in ref. 90. The initial structure is a 4 × 4 × 3 supercell of β-Li3PS4, consisting of 1152 atoms in total. The system was equilibrated at 1500 K for 100 ps and subsequently quenched to 300 K at a cooling rate of 2.5 K/ps under the NPT ensemble. A subsequent 500 ps production run was conducted to compute the radial distribution function.

Dataset details

All datasets except ANI-1x were randomly split into training, validation and test sets with a ratio of 0.9, 0.05 and 0.05, respectively. Due to the large size of the ANI-1x dataset, only a subset was used for demonstration purposes. We randomly sample the conformations of each molecule with the ratio of 0.2, 0.05, and 0.05 for training, validation and testing. With molecules containing less than 10 conformations, all conformations are included in the training to ensure that every molecule in the ANI-1x dataset is included in the training set. The description of datasets was summarized in the following subsection. The QM9 dataset consists of 130,831 organic molecules including H, C, M, O, F. It is a subset of GDB-17 database109 for isotropic polarizability, free energy and the gap between HOMO and LUMO were calculated using DFT at the level of B3LYP/6-31G. The Matbench dataset consists of 132,752 and 10,987 crystals for formation energy and bulk/shear modulus computed with DFT, respectively. All datasets were generated using the Materials Project API on 4/12/2019. The details can be found in ref. 74. The ANI-1x is the extension of ANI-1 dataset78 by performing active learning based on three different samplings including molecular dynamics, normal mode and torsion. All energies and forces of conformers are calculated using DFT at wB97x/6-31G level. The MPF-2021.2.8 dataset consists of 185,877 configurations sampled manually in the relaxation trajectories of 60,000 crystals from Materials Project. Additionally, 89 different isolated elements were also included in the training set. Finally, the MatPES-PBE-v2025.1 dataset consists of 434,712 structures, providing comprehensive coverage of 89 elements. These structures were sampled from 281 million snapshots generated by high-throughput molecular dynamics (MD) simulations at 300 K, conducted on both unit cells and supercells. A two-step DIRECT sampling approach was developed to ensure robust coverage of the configuration space. Interested readers are referred to ref. 79 for more details.

Data availability

All datasets used in this work are publicly available in the following links: QM9: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.978904.v5Matbench: https://hackingmaterials.lbl.gov/automatminer/datasets.htmlANI-1x: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.c.4712477.v1ANI-1xnr: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22814579COMP6: https://github.com/isayev/COMP6MPF-2021.2.8: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/20230723_figshare_DIRECT_zip/23734134MatPES-PBE-v2025.1: https://matpes.ai/.

Code availability

All implementations are available in MatGL(https://github.com/materialsvirtuallab/matgl). The pretrained models will be provided in the latest released version of MatGL. Detailed examples-including the use of pre-trained models, model training, multi-fidelity learning, and transfer learning are provided in the examples directory of the MatGL repository.

References

Chen, C., Zuo, Y., Ye, W., Li, X., Deng, Z. & Ong, S. P. A critical review of machine learning of energy materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903242 (2020).

Schmidt, J., Marques, M. R. G., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 83 (2019).

Westermayr, J., Gastegger, M., Schütt, K. T. & Maurer, R. J. Perspective on integrating machine learning into computational chemistry and materials science. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 230903 (2021).

Oviedo, F., Ferres, J. L., Buonassisi, T. & Butler, K. T. Interpretable and explainable machine learning for materials science and chemistry. Acc. Mater. Res. 3, 597–607 (2022).

Chen, C., Ye, W., Zuo, Y., Zheng, C. & Ong, S. P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 3564–3572 (2019).

Schmidt, J., Pettersson, L., Verdozzi, C., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Crystal graph attention networks for the prediction of stable materials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7948 (2021).

Gasteiger, J., Groß, J. & Günnemann, S. Directional message passing for molecular graphs. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2020).

Gasteiger, J., Giri, S., Margraf, J. T., Günnemann, S. Fast and uncertainty-aware directional message passing for non-equilibrium molecules. In 35th Conferenceon Neural Information Processing Systems. vol. 9 6790–6802 (NeurIPS, 2021).

Satorras, V. G., Hoogeboom, E., Welling, M. E(n) equivariant graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning. 9323–9332 (ACM, 2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Spherical message passing for 3D molecular graphs. In International Conference on Learning Representations. (ICLR, 2022).

Brandstetter, J., Hesselink, R., van der Pol, E., Bekkers, E. J., Welling, M. Geometric and Physical Quantities improve E(3) Equivariant Message Passing. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2022).

Kaba, S.-O. & Ravanbakhsh, S. Equivariant networks for crystal structures. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS, 2022).

Yan, K., Liu, Y., Lin, Y. & Ji, S. Periodic graph transformers for crystal material property prediction. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS, 2022).

Zhang, Y.-W. et al. Roadmap for the development of machine learning-based interatomic potentials. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 33, 023301 (2025).

Ko, T. W. & Ong, S. P. Recent advances and outstanding challenges for machine learning interatomic potentials. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 998–1000 (2023).

Unke, O. T. et al. Machine learning force fields. Chem. Rev. 121, 10142–10186 (2021).

Schütt, K. T., Sauceda, H. E., Kindermans, P.-J., Tkatchenko, A. & Müller, K.-R. SchNet - a deep learning architecture for molecules and materials. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241722 (2018).

Schütt, K., Unke, O. & Gastegger, M. Equivariant message passing for the prediction of tensorial properties and molecular spectra. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning. 9377–9388 (2021).

Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Thompson, A. P., Swiler, L. P., Trott, C. R., Foiles, S. M. & Tucker, G. J. Spectral neighbor analysis method for automated generation of quantum-accurate interatomic potentials. J. Comput. Phys. 285, 316–330 (2015).

Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Ko, T. W., Finkler, J. A., Goedecker, S. & Behler, J. Accurate fourth-generation machine learning potentials by electrostatic embedding. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 3567–3579 (2023).

Kocer, E., Ko, T. W. & Behler, J. Neural network potentials: a concise overview of methods. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 73, 163–186 (2022).

Ko, T. W., Finkler, J. A., Goedecker, S. & Behler, J. A fourth-generation high-dimensional neural network potential with accurate electrostatics including non-local charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 12, 398 (2021).

Liao, Y.-L. & Smidt, T. Equiformer: equivariant graph attention transformer for 3D atomistic graphs. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (ICLR, 2023).

Battaglia, P. W. et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261 (2018).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Chen, C., Zuo, Y., Ye, W., Li, X. & Ong, S. P. Learning properties of ordered and disordered materials from multi-fidelity data. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 46–53 (2021).

Ko, T. W. & Ong, S. P. Data-efficient construction of high-fidelity graph deep learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 11, 65 (2025).

Han, J. et al. A survey of geometric graph neural networks: Data structures, models and applications. Front. Comput. Sci. 19, 1911375 (2025).

Duval, A. et al. A hitchhiker’s guide to geometric gnns for 3d atomic systems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.07511 (2023).

Batzner, S. et al. E (3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G., Ortner, C. & Csányi, G. MACE: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 11423–11436 (2022).

Liao, Y.-L. & Smidt, T. Equiformer: equivariant graph attention transformer for 3d atomistic graphs. International Conference onLearning Representations (ICLR) https://openreview.net/forum?id=KwmPfARgOTD (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhancing geometric representations for molecules with equivariant vector-scalar interactive message passing. Nat. Commun. 15, 313 (2024).

Frank, J. T., Unke, O. T., Müller, K.-R. & Chmiela, S. A Euclidean transformer for fast and stable machine learned force fields. Nat. Commun. 15, 6539 (2024).

Gasteiger, J., Becker, F. & Günnemann, S. Gemnet: Universal directional graph neural networks for molecules. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 6790–6802 (2021).

Fung, V., Zhang, J., Juarez, E. & Sumpter, B. G. Benchmarking graph neural networks for materials chemistry. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–8 (2021).

Bandi, S., Jiang, C. & Marianetti, C. A. Benchmarking machine learning interatomic potentials via phonon anharmonicity. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 5, 030502 (2024).

Fu, X. et al. Forces are not enough: Benchmark and critical evaluation for machine learning force fields with molecular simulations. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2023).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1031–1041 (2023).

Park, Y., Kim, J., Hwang, S. & Han, S. Scalable parallel algorithm for graph neural network interatomic potentials in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 4857–4868 (2024).

Batatia, I. et al. A foundation model for atomistic materials chemistry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.00096 (2024).

Barroso-Luque, L. et al. Open materials 2024 (omat24) inorganic materials dataset and models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.12771 (2024).

Neumann, M. et al. Orb: a fast, scalable neural network potential. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.22570 (2024).

Pelaez, R. P. et al. TorchMD-Net 2.0: fast neural network potentials for molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 4076–4087 (2024).

Schütt, K. T., Hessmann, S. S. P., Gebauer, N. W. A., Lederer, J. & Gastegger, M. SchNetPack 2.0: a neural network toolbox for atomistic machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 144801 (2023).

Axelrod, S., Shakhnovich, E. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Excited state non-adiabatic dynamics of large photoswitchable molecules using a chemically transferable machine learning potential. Nat. Commun. 13, 3440 (2022).

Fey, M. & Lenssen, J. E. Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch geometric. In Proc. ICLR 2019 Workshop on Representation Learning on Graphs and Manifolds (ICLR, 2019).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: a system for large-scale machine learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Conference on Operating Systems Design and Implementation. USA, p 265–283 (ACM, 2016).

Bradbury, J. et al. JAX: composable transformations of Python+NumPy programs. http://github.com/jax-ml/jax (2018).

Wang, M. Y. Deep graph library: Towards efficient and scalable deep learning on graphs. In ICLR workshop on representation learning on graphs and manifolds (2019).

Huang, X., Kim, J., Rees, B. & Lee, C.-H. Characterizing the efficiency of graph neural network frameworks with a magnifying glass. In 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Workload Characterization (IISWC). pp 160–170 (IEEE, 2022).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment-a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Simeon, G. & De Fabritiis, G. Tensornet: Cartesian tensor representations for efficient learning of molecular potentials. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36 (2024).

Vinyals, O., Bengio, S. & Kudlur, M. Order matters: Sequence to sequence for sets. In: Bengio, Y. & LeCun, Y. (eds.) Proc. 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2016, San Juan, Puerto Rico, May 2–4, 2016, Conference Track Proceedings (2016).

Glorot, X. & Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. pp 249–256 (PMLR, 2010).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). pp 1026–1034 (IEEE, 2015).

Bitzek, E., Koskinen, P., Gähler, F., Moseler, M. & Gumbsch, P. Structural relaxation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170201 (2006).

Broyden, C. G., Dennis Jr, J. E. & Moré, J. J. On the local and superlinear convergence of quasi-Newton methods. IMA J. Appl. Math. 12, 223–245 (1973).

Liu, D. C. & Nocedal, J. On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization. Math. Program. 45, 503–528 (1989).

Garijo del Río, E., Mortensen, J. J. & Jacobsen, K. W. Local Bayesian optimizer for atomic structures. Phys. Rev. B 100, 104103 (2019).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., Van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 (1984).

Andersen, H. C. Molecular dynamics simulations at constant pressure and/or temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 72, 2384–2393 (1980).

Schneider, T. & Stoll, E. Molecular-dynamics study of a three-dimensional one-component model for distortive phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 17, 1302–1322 (1978).

Nosé, S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 52, 255–268 (1984).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Liu, R. et al. MatCalc. https://github.com/materialsvirtuallab/matcalc (2024).

Sugita, Y. & Okamoto, Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 141–151 (1999).

Adams, D. Grand canonical ensemble Monte Carlo for a Lennard-Jones fluid. Mol. Phys. 29, 307–311 (1975).

Dunn, A., Wang, Q., Ganose, A., Dopp, D. & Jain, A. Benchmarking materials property prediction methods: the Matbench test set and automatminer reference algorithm. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 1–10 (2020).

Ramakrishnan, R., Dral, P. O., Rupp, M. & Von Lilienfeld, O. A. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci. Data 1, 140022 (2014).

Wang, A. Y.-T., Kauwe, S. K., Murdock, R. J. & Sparks, T. D. Compositionally restricted attention-based network for materials property predictions. Npj Computational Mater. 7, 1–10 (2021).

Pozdnyakov, S. N. & Ceriotti, M. Incompleteness of graph neural networks for points clouds in three dimensions. Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 3, 045020 (2022).

Smith, J. S., Nebgen, B., Lubbers, N., Isayev, O. & Roitberg, A. E. Less is more: sampling chemical space with active learning. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241733 (2018).

Kaplan, A. D. et al. A foundational potential energy surface dataset for materials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.04070 (2025).

Zhang, S. Exploring the frontiers of condensed-phase chemistry with a general reactive machine learning potential. Nat. Chem. 16, 727–734 (2024).

Kovács, D. P. et al. Mace-off: Shortrangetransferable machine learning force fields for organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 17598–17611 (2025).

Qi, J., Ko, T. W., Wood, B. C., Pham, T. A. & Ong, S. P. Robust training of machine learning interatomic potentials with dimensionality reduction and stratified sampling. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 43 (2024).

Gonzales, C., Fuemmeler, E., Tadmor, E. B., Martiniani, S., Miret, S. Benchmarking of universal machine learning interatomic potentials for structural relaxation. In AI for Accelerated Materials Design (NeurIPS, 2024).

Yu, H., Giantomassi, M., Materzanini, G., Wang, J. & Rignanese, G.-M. Systematic assessment of various universal machine-learning interatomic potentials. Mater. Genome Eng. Adv. 2, e58 (2024).

Pan, H. Benchmarking coordination number prediction algorithms on inorganic crystal structures. Inorg. Chem. 60, 1590–1603 (2021).

Loew, A., Sun, D., Wang, H.-C., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. Universal machine learning interatomic potentials are ready for phonons. npj Comput Mater 11, 178 (2025).

Batatia, I. et al. A foundation model for atomistic materials chemistry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.00096 (2023).

Zuo, Y. Performance and cost assessment of machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 731–745 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Complex Ga2O3 polymorphs explored by accurate and general-purpose machine-learning interatomic potentials. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 159 (2023).

Chen, Z., Du, T., Krishnan, N. A., Yue, Y. & Smedskjaer, M. M. Disorder-induced enhancement of lithium-ion transport in solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 16, 1057 (2025).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Poltavsky, I. et al. Crash testing machine learning force fields for molecules, materials, and interfaces: model analysis in the TEA Challenge 2023. Chem. Sci. 16, 3720–3737 (2025).

Poltavsky, I. et al. Crash testing machine learning force fields for molecules, materials, and interfaces: molecular dynamics in the TEA challenge 2023. Chem. Sci. 16, 3738–3754 (2025).

Bihani, V. et al. EGraFFBench: evaluation of equivariant graph neural network force fields for atomistic simulations. Digit. Discov. 3, 759–768 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Accelerating computational materials discovery with machine learning and cloud high-performance computing: from large-scale screening to experimental validation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20009–20018 (2024).

Ojih, J., Al-Fahdi, M., Yao, Y., Hu, J. & Hu, M. Graph theory and graph neural network assisted high-throughput crystal structure prediction and screening for energy conversion and storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 8502–8515 (2024).

Sivak, J. T. et al. Discovering high-entropy oxides with a machine-learning interatomic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 216101 (2025).

Taniguchi, T. Exploration of elastic moduli of molecular crystals via database screening by pretrained neural network potential. CrystEngComm 26, 631–638 (2024).

Mathew, K. et al. Atomate: a high-level interface to generate, execute, and analyze computational materials science workflows. Computational Mater. Sci. 139, 140–152 (2017).

Miret, S., Lee, K. L. K., Gonzales, C., Nassar, M. & Spellings, M. The open MatSci ML toolkit: a flexible framework for machine learning in materials science. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2023).

te Velde, G. et al. Chemistry with ADF. J. Comput. Chem. 22, 931–967 (2001).

Schwalbe-Koda, D., Hamel, S., Sadigh, B., Zhou, F. & Lordi, V. Model-free estimation of completeness, uncertainties, and outliers in atomistic machine learning using information theory. Nat. Commun. 16, 4014 (2025).

Musielewicz, J., Lan, J., Uyttendaele, M. & Kitchin, J. R. Improved uncertainty estimation of graph neural network potentials using engineered latent space distances. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 20799–20810 (2024).

Podryabinkin, E. V. & Shapeev, A. V. Active learning of linearly parametrized interatomic potentials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 140, 171–180 (2017).

Kulichenko, M. et al. Uncertainty-driven dynamics for active learning of interatomic potentials. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 230–239 (2023).

Park, H., Onwuli, A., Butler, K. T. & Walsh, A. Mapping inorganic crystal chemical space. Faraday Discuss. 256, 601–613 (2025).

Onwuli, A., Hegde, A. V., Nguyen, K. V., Butler, K. T. & Walsh, A. Element similarity in high-dimensional materials representations. Digital Discov. 2, 1558–1564 (2023).

Landrum, G. et al. RDKit: a software suite for cheminformatics, computational chemistry, and predictive modeling. Greg. Landrum 8, 5281 (2013).

RRuddigkeit, L., Van Deursen, R., Blum, L. C. & Reymond, J.-L. Enumeration of 166 billion organic small molecules in the chemical universe database GDB-17. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 2864–2875 (2012).

Tran, R. Surface energies of elemental crystals. Sci. Data 3, 1–13 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was intellectually led by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 (Materials Project program KC23MP). This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility using NERSC award DOE-ERCAP0026371. T.W.Ko also acknowledges the support of the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Schmidt Futures program. We also acknowledged AdvanceSoft Corporation for implementing the LAMMPS interface.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P.O. and S.M. conceived the idea and initiated the research project. T.W.K. led the implementation of major components with support and advice from S.P.O.. T.W.K. also contributed to most of the model training and benchmarking. B.D. contributed to the implementation and training of CHGNet and improved some parts of implementations in MatGL under the guidance of G.C.. M.N. contributed to the preliminary implementation of MEGNet. L.B. helped with the implementation of the CHGNet and graph construction. J.Q. helped with the implementation of graph construction and the training of MLIPs. R.L. contributed to the design of workflow and benchmarking for different GNN models trained by T.W.K., J.Q. and B.D.. A.C.T. performed surface energy calculations and A.R.M. performed the structural analysis of disorder materials. E.L. helped with the implementation of different basis functions. T.W.K. and S.P.O. wrote the initial manuscript and all authors contributed to the discussion and revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.C. and S.P.O. are Editorial Board Members of npj Computational Materials.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, T.W., Deng, B., Nassar, M. et al. Materials Graph Library (MatGL), an open-source graph deep learning library for materials science and chemistry. npj Comput Mater 11, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01742-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01742-y

This article is cited by

-

Combining feature-based approaches with graph neural networks and symbolic regression for synergistic performance and interpretability

npj Computational Materials (2026)

-

A pre-trained deep potential model for sulfide solid electrolytes with broad coverage and high accuracy

npj Computational Materials (2025)

-

MP-ALOE: an r2SCAN dataset for universal machine learning interatomic potentials

npj Computational Materials (2025)