Abstract

We present an efficient implementation of the Zero Static Internal Stress Approximation (ZSISA) within the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation framework to compute anisotropic thermal expansion and elastic constants from first principles. By replacing the costly multidimensional minimization with a gradient-based method that leverages second-order derivatives of the vibrational free energy, the number of required phonon band structure calculations is significantly reduced: only six are needed for hexagonal, trigonal, and tetragonal systems, and 10–28 for lower-symmetry systems to determine the temperature dependence of lattice parameters and thermal expansion. This approach enables accurate modeling of anisotropic thermal expansion while substantially lowering computational cost compared to standard ZSISA method. The implementation is validated on a range of materials with symmetries from cubic to triclinic and is extended to compute temperature-dependent elastic constants with only a few additional phonon band structure calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding thermal expansion and elastic properties at varying temperatures and pressures is essential for predicting the thermomechanical behavior of crystalline materials in diverse applications. Except for the cubic crystallographic system, thermal expansion is inherently anisotropic, meaning it differs along various lattice directions. For the monoclinic and triclinic systems, the angle(s) will also change with temperature. This directional dependence plays a crucial role in material performance and the design of advanced devices. In certain cases, expansion may be negative or nearly zero along one direction while remaining positive along others, a key factor in controlling thermal stability and phase transitions1,2,3. First-principles methods, particularly those based on density functional theory (DFT)4,5, have been extensively used to compute volumetric thermal expansion. However, accurately capturing anisotropic thermal expansion remains computationally demanding, as it requires evaluating free energy derivatives along multiple independent lattice directions.

The quasiharmonic approximation (QHA)6,7,8,9 is a well-established approach for modeling temperature-dependent material properties in solids with weak anharmonicity. This method accounts for changes in phonon frequencies due to lattice expansion while neglecting direct phonon-phonon interactions. QHA assumes that phonons remain harmonic, non-interacting, and primarily governed by lattice parameters and equilibrium atomic positions. Within this framework, the total free energy, including harmonic phonon contributions, is expressed as a function of both lattice parameters and internal atomic positions at a given temperature. Minimizing this free energy for different temperatures provides insights into how these structural degrees of freedom evolve with temperature and pressure.

QHA has been widely used to predict thermal expansion by tracking the temperature-dependent evolution of lattice parameters and to compute elastic constants10,11,12 through the evaluation of free energy under applied strains. The approach enables the study of temperature-dependent mechanical properties and anisotropic lattice responses, making it a powerful tool for exploring thermoelastic behavior in a wide range of materials. The QHA Gibbs free energy consists of the phonon contribution, the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) energy at zero temperature, and the enthalpic term associated with external pressure. For metals, an additional correction accounts for the electronic free energy. Notably, even at absolute zero, the phonon free energy remains nonzero due to quantum zero-point motion.

Recent advances in first-principles techniques have enabled highly accurate phonon spectrum calculations, facilitated by methods such as density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)13,14,15,16 and the finite displacement method17. The reliability of these techniques has made high-throughput phonon calculations feasible, establishing QHA as a robust tool for predicting temperature-dependent thermodynamic and mechanical properties, provided that higher-order anharmonic effects remain minimal18,19,20.

The computational cost of phonon spectra calculations remains a key limitation of QHA, making it significantly more demanding than the direct minimization of the BO energy to determine equilibrium lattice parameters and atomic positions. This challenge is particularly relevant for materials with low symmetry, where thermal expansion depends on multiple independent structural degrees of freedom. In contrast, for cubic systems, where volume is the only free parameter and all internal atomic positions are fixed by symmetry, QHA simplifies to a one-dimensional optimization problem requiring relatively few phonon calculations. For lower-symmetry structures, including tetragonal, rhombohedral, hexagonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic crystals, thermal expansion becomes more complex as multiple lattice parameters evolve independently with temperature. Additionally, internal atomic positions, which are not fully constrained by symmetry, must be determined. Precisely accounting for these effects within QHA poses significant computational challenges and frequently requires further approximations.

One widely adopted approach is the zero static internal stress approximation (ZSISA), introduced by Allan and colleagues in 199621,22,23. ZSISA reduces computational complexity of the QHA by assuming that internal atomic positions can be determined solely by minimizing the BO energy at each fixed lattice configuration, rather than performing a full free energy (including vibrational contributions) minimization. By enforcing the condition that atomic forces vanish in the BO energy landscape, ZSISA introduces only second-order errors in neglected thermal internal stresses. While this approximation is effective for predicting macroscopic thermal expansion, its accuracy in describing temperature-dependent internal atomic displacements is more limited, particularly at high temperatures or in systems where zero-point energy effects are significant24,25. Despite these limitations, ZSISA remains a widely used approach for modeling anisotropic thermal expansion in QHA studies, particularly in uniaxial systems such as the wurtzite structure, where only two lattice degrees of freedom need to be considered8,12,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33.

For low-symmetry crystals such as orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic structures, the application of the ZSISA model becomes impractical due to the exponentially increasing computational cost of phonon spectrum calculations. Even in uniaxial systems, determining the temperature and pressure dependence of elastic constants and thermal expansion at high temperatures and pressures using ZSISA remains computationally very expensive12. This is because, to accurately capture high-pressure effects, the lattice undergoes significant changes, requiring multiple QHA calculations for different volumes. Consequently, researchers often resort to the volume-constrained zero static internal stress approximation (v-ZSISA)34 to manage these computational challenges. In this approach, the volume is treated as the primary degree of freedom, while all other structural parameters are optimized at a fixed volume.

Within the v-ZSISA framework, phonon spectra are typically computed for only seven to twelve different volumes35, significantly fewer than in a standard ZSISA approach, where free energy sampling across all degrees of freedom leads to an exponential increase in computational effort. Due to its reduced computational cost, most QHA studies in the literature rely on this approximation17,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. However, while v-ZSISA provides reasonable predictions for the temperature and pressure dependence of volumetric expansion, its accuracy in capturing anisotropic thermal expansion is considerably limited, often failing to align with experimental results25.

Various approximations have been introduced to reduce the computational cost associated with QHA. One such approach is the linear Grüneisen method9, which simplifies the problem by expanding the Born-Oppenheimer energy to second order and the phonon free energy to first order in the parameters being optimized. Unlike ZSISA and v-ZSISA, which reduce the effective dimensionality of the problem, the linear Grüneisen method maintains the full parameter space but achieves a more manageable scaling. This method estimates the derivative of the phonon free energy with respect to geometric parameters, such as volume, using Grüneisen parameters42, requiring only a limited number of phonon calculations, typically twice the number of parameters considered. While effective for predicting zero-point lattice expansion and its contribution to zero-point renormalization of the band gap energy in cubic and hexagonal materials33, the approach is inherently limited to the low-temperature regime (below the Debye temperature). At higher temperatures, its thermal expansion predictions become inaccurate, asymptotically saturating rather than continuing to increase as in QHA.

In our previous work43, we introduced new intermediate methods bridging v-ZSISA and the linear Grüneisen approach by applying a Taylor expansion to the vibrational free energy while keeping the BO energy calculations exact. Since BO energy computations are significantly cheaper than phonon calculations, this strategy reduces computational cost without introducing unnecessary approximations. The most straightforward improvement over the linear Grüneisen method is to retain the full BO energy while using a minimal-order Taylor expansion for the phonon free energy.

We proposed three variants: v-ZSISA-E∞Vib1, v-ZSISA-E∞Vib2, and v-ZSISA-E∞Vib4, which employ first-, second-, and fourth-order Taylor expansions of the phonon free energy, requiring only two, three, and five phonon calculations at different volumes, respectively. A concise overview of these methods is provided in the Supplementary Note 1, Summary of Approximations and Acronyms, for clarity.

To evaluate their accuracy, we applied these methods to 12 materials spanning diverse space groups, from cubic to monoclinic structures. Using v-ZSISA as the reference, we found that a quadratic expansion (using three phonon calculations) yields highly accurate results with an error below 1%, for our tested materials below 800 K, while a fourth-order expansion (five phonon calculations) closely matches the v-ZSISA reference. This highlights the effectiveness of our approach in significantly reducing computational costs while preserving high precision in volumetric thermal expansion predictions.

Accordingly, in the present work, we adopt a second-order Taylor expansion as a reliable approximation for the vibrational free energy. We extend the E∞Vib2 method to anisotropic systems and introduce the ZSISA-E∞Vib2 approach. This method applies a multidimensional Taylor expansion to the vibrational free energy, incorporating the system lattice degrees of freedom. A key advancement of our method is the introduction of gradient-based optimization for anisotropic lattice parameters, which significantly accelerates the computational process compared to existing gradient-free techniques. This innovation enables efficient exploration of lattice configurations with fewer phonon and band structure calculations, without compromising accuracy. By reducing the number of required phonon calculations compared to a full multi-dimensional mesh, it maintains accuracy while significantly lowering computational costs. The approach determines thermal stress using finite differences and optimizes the Born-Oppenheimer energy self-consistently to eliminate thermal stress at a given pressure. Once the equilibrium structure is identified at each temperature and pressure, second derivatives of the BO energy, obtained through DFPT, and the vibrational free energy, computed using finite differences, allow for the calculation of thermal expansion coefficients and elastic constants.

The validity of the proposed method is assessed by applying it to determine the anisotropic thermal expansion and elastic constants of materials with different crystallographic symmetries. The study includes cubic MgO, hexagonal ZnO, AlN, and GaN, trigonal CaCO3 and Al2O3, tetragonal SnO2, orthorhombic YAlO3, monoclinic ZrO2, HfO2, and MgP4, and triclinic Al2SiO5. For the uniaxial cases, our method exhibits excellent agreement with ZSISA. For crystals with even lower symmetries, a direct comparison is not performed with ZSISA, as it is too expensive. However, our predicted anisotropic thermal expansion aligns well with experimental data for such cases, whereas v-ZSISA fails to capture these trends. In some instances, v-ZSISA even predicts an opposite trend, further emphasizing the advantage of our method in describing anisotropic effects.

The structure of this paper is as follows: “Results“ presents our results, followed by the discussions in “Discussion“. “Methods” details the methodology, covering the definition of free energy, the quasiharmonic approximation (QHA), ZSISA, and v-ZSISA, approximations for the vibrational free energy, thermal stress, determination of lattice parameters at finite temperature and external pressure, thermal expansion, and elastic constants. It also presents the equations for specific crystallographic cases, including monoclinic structure and the computational details, and the materials studied.

Results

The proposed method was tested on various materials representing a wide range of crystallographic structures, from cubic to triclinic. For cubic structures, applying this thermal expansion method using thermal stress does not offer significant advantages over the v-ZSISA-E∞Vib2 approach introduced in our previous work43. In fact, the computational effort may exceed that of the previous method. However, the current approach proves beneficial for computing elastic constants at finite temperatures and pressures, requiring only five phonon spectra calculations to determine the three independent elastic constants (two more than for the volume only). To illustrate this, we used MgO as a representative cubic material for elastic constant calculations.

For uniaxial systems, including hexagonal, trigonal, and tetragonal structures, we computed thermal expansion for several compounds. These include ZnO, GaN, and AlN in the wurtzite structure (space group P63mc), CaCO3 and Al2O3 in the rhombohedral structure (space group \(R\bar{3}c\)), and SnO2 in the tetragonal structure (space group P42/mnm), as summarized in Table 1.

Orthorhombic YAlO3 was selected as a representative material for orthorhombic structures. In the monoclinic category, we examined ZrO2, HfO2, and MgP4, all with space group P21/c. Finally, Al2SiO5 (space group \(P\bar{1}\)) was chosen as a representative of triclinic symmetry. The number of atoms in the primitive unit cell for each structure is also provided in Table 1. The reference structure includes base strains of \({\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}={\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}}={\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}}=0.005\) and \({\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}={\varepsilon }_{yz}^{{\rm{BO}}}={\varepsilon }_{xy}^{{\rm{BO}}}=0\), consistent with the positive thermal expansion behavior of our materials. In our calculations, [RBO] is chosen as the relaxed BO configuration at zero strain and zero pressure, serving as the reference point for all deformation calculations. We used a total of 20 temperature points to obtain our results, employing an adaptive step size strategy to balance precision and efficiency. From 0 K to 200 K, where thermal behavior changes more rapidly, a finer step size of 25 K was chosen. Between 200 K and 500 K, a step size of 50 K was used, while for temperatures above 500 K up to 1000 K, a larger step size of 100 K was sufficient due to the smoother thermal response at higher temperatures.

We did not generate QHA results for all materials due to their significant computational expense and resource demands. As an initial test of the proposed approximations, we applied the full ZSISA method to ZnO as a representative uniaxial system.

For materials with more than two lattice degrees of freedom, the computational cost of phonon spectra calculations increases considerably, even when accounting for symmetry reductions. Consequently, testing the ZSISA method for lower-symmetry systems was not undertaken.

For these cases, we nevertheless performed an internal check within the E∞Vib2 method, comparing the thermal stress approach with the results obtained from fitting the high-dimensional free energy. For monoclinic ZrO2, which has four degrees of freedom, we constructed a 4D surface of free energies. This required 625 BO energy evaluations for E∞, while the second-degree Taylor expansion for the phonon free energy relied on 15 phonon spectra calculations for FV ib2. The results were consistent between both approaches, demonstrating high accuracy. These results emphasize the practicality and reliability of the method for systems with complex anisotropic properties.

In the main text, we present detailed results for MgO, ZnO, and ZrO2. The results for the remaining materials are included in Supplementary Figs. 2–19 in the Supplementary Information (SI)44.

MgO

MgO, with its cubic structure, has a lattice constant of a = 4.214 Å in our computational setup. For thermal expansion calculations, only one degree of freedom governs the lattice, making the process equivalent to the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method from our previous work. This approach simplifies the procedure by interpolating the total energy at different volumes with selected EBO values to fit an equation of state (EOS), eliminating the need for a complete workflow to determine EBO. In contrast, computing elastic constants requires treating the cubic primitive cell as monoclinic to capture all necessary distortions and determine each non-zero element of the elastic constants tensor. There are important differences when applying monoclinic deformations to cubic systems. Due to symmetry, the deformations along the εxx, εyy, and εzz directions are equivalent, as are the shear strains εxy, εxz, and εyz. This symmetry reduces the number of required deformations. Furthermore, since the first derivative of the free energy, and consequently the stress, is zero for non-orthogonal directions (xz, xy, yz), it is possible to use orthorhombic equations for computing [R(T, Pext)], simplifying the overall process.

However, to compute C44, one additional equation is necessary to find the second derivative \({\partial }^{2}{F}_{{\rm{vib}}}/\partial {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO2}}}\). Unlike the monoclinic case, where symmetric deformations \(\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\) are used, cubic symmetry necessitates applying both \(\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\) and \(2\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\). This distinction arises from the equivalence of symmetric strain variations due to the zero derivative of Fvib in the xz direction and is further explained in the Supplementary Note 3, Accurate Second Derivative Calculation, where the unique deformation requirements for cubic and uniaxial systems are discussed. The applied strains for elastic constant calculations were [εBO•], \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]+\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), and \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]+2\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\) with δεBO = 0.005.

Figure 1 presents the thermal expansion and elastic constants of MgO as a function of temperature at different external pressures. The top panel compares the thermal expansion obtained using the v-ZSISA method (dashed lines) with the proposed orthorhombic approach (solid lines with markers) for three external pressures: 0, 4, and 8 GPa. Experimental data at zero pressure are shown as discrete points for validation. In the v-ZSISA method, thermal expansion is derived from calculations at eight different volumes, ranging from 0.94 to 1.08 times the equilibrium BO volume, with increments of 0.02. The data are fitted using the Vinet equation of state45.

a Thermal expansion at external pressures Pext = 0, 4, and 8 GPa, computed using v-ZSISA (dashed lines) and the proposed orthorhombic approach (solid lines with markers). Experimental data73 at Pext = 0 GPa are shown as discrete points for comparison. b Temperature dependence of the elastic constants C11, C12, and C44 at Pext = 0 GPa (solid lines), 4 GPa (dashed lines), and 8 GPa (dotted lines with markers). Experimental values74 at Pext = 0 GPa are represented by discrete points.

The results indicate that the temperature dependence of thermal expansion predicted by v-ZSISA and the orthorhombic v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method is in good agreement, with minor discrepancies attributed to numerical errors. However, neither theoretical approach fully matches experimental values due to anharmonic effects in MgO, which are not captured within QHA. Nonetheless, since the objective of this study is to evaluate QHA-based methods, the results remain valid in temperature ranges where QHA is applicable.

The bottom panel illustrates the temperature dependence of the elastic constants C11, C12, and C44 for Pext=0 GPa (solid lines with markers), 4 GPa (dashed lines with markers), and 8 GPa (dotted lines with markers). Experimental values at Pext=0 GPa are included for comparison. The computed elastic constants exhibit a decreasing trend with temperature and an increasing trend with pressure, consistent with experimental data. However, even at 0 K, the discrepancy between theoretical elastic constants and experimental ones (at 0 GPa) is on the order of a few percent, due to the exchange-correlation functional inaccuracy.

ZnO

For ZnO in the wurtzite structure, the optimized lattice parameters are a = 3.227 Å, and c = 5.206 Å. The planewave kinetic energy cutoff (ecut) is set to 42 Ha, and a k-grid and q-grid of 6 × 6 × 4 is used for Brillouin zone sampling. For all calculations, the internal degrees of freedom of the atomic positions are fully optimized to minimize forces on the atoms. ZnO in the wurtzite structure can be analyzed using either hexagonal symmetry or lower-symmetry configurations involving three or more degrees of freedom. For hexagonal symmetry with three DOF, the relevant strain components are εxx, εyy, and εzz, analogous to the orthorhombic case. However, in the hexagonal system, symmetry constraints reduce the independent strain components, with εxx = εyy simplifying the equations to a 2DOF model.

The 2DOF approach offers substantial computational advantages for two main reasons. First, it reduces the number of required deformations from 7 to 6, streamlining the overall calculation process. More importantly, it preserves hexagonal symmetry in all deformations, whereas the 3DOF approach breaks this symmetry, resulting in lower-symmetry configurations that demand more computational resources. Since phonon spectra calculations are significantly faster for higher-symmetry structures, adopting the 2DOF treatment not only reduces the number of deformations but also lowers the computational cost for each deformation.

Different strain configurations are required for thermal expansion and elastic constant calculations to account for the symmetry constraints involved in each process. The strain patterns used for thermal expansion are \([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]+\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}+\delta {\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\).

For combined elastic constant and thermal expansion calculations, the following strain patterns are applied \([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]+\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), and \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]+2\delta {\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}})\) where the magnitude of strain increment is set to δεBO = 0.005.

To systematically validate the new method, we compare its results with those of ZSISA and v-ZSISA. In the v-ZSISA approach, thermal expansion is determined from calculations at seven distinct volumes, ranging from 0.96 to 1.08 times the equilibrium BO volume, in increments of 0.02. For ZSISA, the lattice parameters a and c are systematically varied over a 25-point strain mesh (five points in each direction) spanning [−0.005, 0.015] relative to the BO lattice. A third-order (cubic) two-dimensional surface is then fitted to the computed free energy values, and the equilibrium lattice parameters at each temperature are obtained by minimizing this surface.

Figure 2 illustrates the temperature dependence of the lattice parameters and thermal expansion. The results show strong agreement between ZSISA and v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2, confirming the consistency of the methodology. However, ZSISA and v-ZSISA yield different final results of anisotropic thermal expansion and lattice parameters, while their volumetric thermal expansion predictions remain consistent. Experimental data indicate distinct thermal expansion coefficients for a and c, whereas v-ZSISA predicts nearly identical values, failing to capture the experimental anisotropy. In contrast, v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 matches experimental observations, effectively reproducing the anisotropic thermal expansion of ZnO. Nevertheless, the accuracy of the results remains sensitive to the choice of the exchange-correlation functional. Volumetric thermal expansion results are in agreement in v-ZSISA and ZSISA methods.

a Temperature dependence of the lattice parameters a and c of ZnO, calculated using the v-ZSISA approach (solid lines) and the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method (dashed-dotted lines). b Thermal expansion coefficients of a and c axes (αa and αc) as a function of temperature, obtained from ZSISA (dotted line), v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 (solid line), and v-ZSISA (dashed line). Experimental data75 points at zero pressure, are included for validation.

Figure 3 presents the temperature dependence of the anisotropic thermal expansion and elastic constants of ZnO under varying pressure conditions, as obtained from the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method. Panels (a) and (b) show the thermal expansion of the lattice parameters a and c at pressures of 0, 4, and 8 GPa, respectively. Panels (c) and (d) display the corresponding elastic constants at 0 GPa and 8 GPa, highlighting the effect of pressure on the mechanical properties of ZnO.

ZrO2

ZrO2 adopts a monoclinic structure at temperatures below approximately 1443 K. In our calculations, the optimized BO lattice parameters are a = 5.126 Å, b = 5.209 Å, c = 5.295 Å, with a monoclinic angle β = 99.59. The strain configurations applied for the monoclinic case in determining both thermal expansion and elastic constants differ by only three additional strains required for elastic constants. Specifically, 15 strain patterns are sufficient for thermal expansion calculations, while 18 strains are needed when computing elastic constants. The complete set of these strain configurations is provided in the Supplementary Table 1,

Figure 4 illustrates the temperature dependence of the lattice parameters and angle of monoclinic ZrO2 at zero pressure. Panels (a) and (b) show the lattice parameters and the angle β, respectively, calculated using the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 approach (solid lines) and the v-ZSISA method (dashed-dotted lines). Experimental data points are included for direct comparison. Panel (c) presents the thermal expansion coefficient as a function of temperature, with results from the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method (solid line) and the v-ZSISA approach (dashed-dotted line), with the experimental thermal expansion data shown by the dashed lines for reference.

Temperature dependence of a the lattice parameters and b the angle of ZrO2, calculated using the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 approach (solid lines) and the v-ZSISA method (dashed-dotted lines). Experimental data46 points are shown as markers. c Thermal expansion coefficient as a function of temperature, with results from the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method (solid line) and the v-ZSISA approach (dashed-dotted line). Experimental thermal expansion data are provided by the dashed lines for comparison.

The v-ZSISA method is based on calculations at seven volumes, ranging from 0.96% to 1.08% of the BO volume, with a step size of 0.02%. The experimental thermal expansion is computed by fitting a line to the lattice data points at different temperatures and differentiating the fitted curve.

A noteworthy difference between the v-ZSISA and ZSISA - E∞Vib2 methods is the temperature dependence of the angle. Experimental results46 show a decrease in the β angle with increasing temperature. The v-ZSISA method predicts an opposite trend, where the angle increases with temperature. In contrast, the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 method correctly captures the direction of the angle decrease, although the predicted values are slightly different. This discrepancy is due to the exchange-correlation functional. Modifying the functional could potentially lead to a better agreement with experimental results. The thermal expansion predictions from the v - ZSISA - E∞Vib2 show a better agreement with the experimental data compared to the v-ZSISA approach.

Figure 5 illustrates the temperature dependence of the 13 elastic constants of monoclinic structure, emphasizing their temperature-induced variations.

Discussion

In this work, we introduce a novel method for determining the anisotropic thermal expansion and elastic constants of materials with arbitrary crystal structures, achieving accuracy comparable to the quasiharmonic approximation with zero static internal stress (ZSISA). While ZSISA is highly accurate for weakly anharmonic crystals, it is computationally expensive due to the need for numerous phonon spectrum calculations. Specifically, for systems with n lattice degrees of freedom, traditional methods require an impractically large number of lattice mesh points, often exceeding 5n for high-accuracy thermal expansion predictions. This makes the direct application of ZSISA computationally intensive for systems with more than three lattice degrees of freedom. Our method addresses this limitation by reducing the number of required calculations, making it applicable to a wider range of systems while preserving a sufficient precision up to about 800 K.

Building on prior work43, where we demonstrated that truncating the vibrational free energy expansion to second order provides results comparable to the full quasiharmonic treatment, we extend this approach by employing a Taylor series expansion of the vibrational free energy up to the second derivative to calculate the Gibbs free energy in the multidimensional space of degrees of freedom. This method incorporates self-consistent optimization of lattice parameters and atomic positions, taking into account thermal stresses and using the accurate Born-Oppenheimer energy to ensure precise thermal properties.

By significantly reducing the computational demands, our approach provides a practical and efficient alternative to ZSISA, especially for materials with complex crystal symmetries, such as monoclinic and triclinic structures. For instance, in the case of a triclinic system, we achieve accurate predictions of both thermal expansion and elastic constants with only 28 phonon spectrum calculations-three orders of magnitude reduction compared to more than 15,625 calculations required by ZSISA.

Our results demonstrate that the new method can replicate ZSISA with high accuracy, making it a viable alternative whenever ZSISA is not applicable. We successfully apply this method to 10 materials with a variety of crystal structures, from cubic to monoclinic and triclinic forms, further validating its utility and versatility.

Methods

The free energy

Consider the crystallographic parameters, including lattice constants, cell angles, and internal atomic positions, represented by Cγ, with γ ranging from 1 to NC. In a scenario where symmetries are ignored, NC is given by 6 + 3Nat − 3. Here, 6 represents the macroscopic crystallographic parameters, and Nat stands for the number of atoms within the primitive cell. The remaining 3Nat − 3 parameters arise from the internal degrees of freedom, excluding the overall translational motion of the crystal. However, symmetry considerations reduce the number of truly independent crystallographic parameters significantly. Additionally, this framework can be expanded to include magnetic variables as part of the crystallographic parameters, utilizing techniques such as constrained-DFT47,48. The entire set of parameters Cγ can be summarized as a vector \(\underline{C}\), and the temperature-dependent behavior of these parameters, Cγ(T) or \(\underline{C}(T)\), is the focus of this study.

Although lattice constants and angles are well-defined macroscopic quantities, internal atomic positions represent average values over a large ensemble of cells that make up the solid. In this context, it is assumed that atomic position fluctuations within each cell occur around a single average value, excluding cases where multiple local configurations with similar (or nearly similar) energies are present, causing the system to transition between these configurations over time. Additionally, it is assumed that these crystallographic parameters can be continuously altered through the application of external stresses and internal forces within a computational framework, where the latter are applied uniformly across a sublattice associated with a specific average atomic position.

To determine the temperature-dependent crystallographic parameters Cγ(T) at zero pressure, the Helmholtz free energy F[Cγ, T] must be minimized according to the following:

The temperature dependence of the parameters Cγ(T) is therefore determined implicitly through the minimization condition given in Eq. (1), which leads to:

The free energy, \(F(\underline{C},T)\), is composed of several components: the Born-Oppenheimer internal energy at absolute zero (0 K), which is independent of temperature; the vibrational (phonon) contribution to the free energy; and additional corrections such as electronic entropy and interactions between electrons and phonons. These corrections might be relevant for metals at very low temperatures but are generally negligible for insulators. Therefore, the Helmholtz free energy can be approximated as:

In this study, we assume that the BO energy, EBO(Cγ), can be computed quickly from first principles, especially compared to the time required to calculate the vibrational free energy, Fvib(Cγ, T), which is also derived from first principles. However, it is important to note that the gradients of Fvib(Cγ, T) with respect to the parameters Cγ are not directly available. They can, however, be estimated using finite difference methods. Each calculation of Fvib(Cγ, T) for a different set of Cγ needs to be meticulously planned.

By substituting Eq. (4) into Eq. (3), we obtain a more explicit condition for determining \(\underline{C}(T)\):

The right side of Eq. (5) is referred to as the thermal gradient at the point \(\underline{C}(T)\). If γ corresponds to a cell parameter, then ∂Fvib/∂Cγ represents a stress. If γ corresponds to an atomic position, it represents a generalized or collective force.

Since F reaches a minimum at Cγ(T), it follows from Eq. (3) that, for any γ and T,

Applying the chain rule to obtain the total derivative of this expression gives

Consequently, \(\frac{d{C}_{\gamma }}{dT}{| }_{T}\) can be obtained using the inverse of the second derivative matrix of the free energy, expressed as follows

where \(S=-\frac{\partial F}{\partial T}\) represents the entropy.

The Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QHA)

In the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation, we treat atomic vibrations as harmonic, but we allow the vibrational frequencies to change depending on the crystallographic parameters and the positions of atoms within the structure. To make this dependency clear, we express the frequencies as \({\omega }_{{\bf{q}}\nu }(\underline{C})\), where q represents the phonon wavevector with ν the phonon branch index. Such calculations are well-defined within a first-principles approach: the interatomic force constants are derived from the second-order derivatives of the BO energy, supposing that the \(\underline{C}(T)\) parameters are those for which Eq. (5) is fulfilled at that temperature, namely, supposing that the BO gradient is canceled by the thermal gradient.

The vibrational free energy is then calculated using Bose-Einstein statistics, \({n}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }(\underline{C},T)\), which gives the occupation number for each phonon mode. This also includes the contribution from zero-point motion. Specifically, the vibrational free energy per unit cell is

and the entropy per unit cell is given by

where, ΩBZ represents the Brillouin zone volume, related to the primitive cell volume Ω0 by \({\Omega }_{{\rm{BZ}}}=\frac{{(2\pi )}^{3}}{{\Omega }_{0}}\). It is important to note that the phonon frequencies ωqν do not depend directly on temperature, in contrast to the phonon occupation numbers nqν that are given by Bose-Einstein statistics

ZSISA and v-ZSISA

ZSISA and v-ZSISA are approximations of the full QHA. In the ZSISA method, crystallographic parameters can be divided into external and internal strains. The internal strains are those associated with the internal degrees of freedom, explicitly, the atomic positions within the unit cell, while the external strains refer to parameters like lattice constants, angles, or volume. The approximation involves optimizing the internal strains by adjusting atomic positions, while the external strains, such as lattice constants, are held constant. This approach simplifies the problem by considering internal strains as a function of external strains.

If the external strain is limited to changes in volume only, this approach is known as the v-ZSISA approximation. In this approach, the free energy defined in Eq. (4) is minimized at a fixed volume to determine the values of the remaining degrees of freedom, such as lattice parameters, angles, and internal atomic positions.

When considering a constant external pressure Pext, the Gibbs free energy \(G([R(T,\,{P}_{\mathrm{ext}})],\, {T}, \, {P}_{\text{ext}})\) is given by

Note that like in Eq.(Equ1), the usual thermodynamic potential \(G(T,\,{P}_{\text{ext}})\) is found by minimizing \(G([R(T,\,{P}_{\text{ext}})],\, T,\,{P}_{\text{ext}})\) over [R]. At a given temperature T and equilibrium volume V(T, Pext), the derivative of the free energy with respect to volume, which corresponds to the pressure, is zero. This condition can be expressed as

where the PBO and Pvib denote Born-Oppenheimer pressure and the vibrational (thermal) pressure, respectively. At the equilibrium volume for a specific temperature, these pressures, also including Pext, must cancel each other, so that

In more general scenarios, where ZSISA is applied to external strains affecting lattice constants or angles, all components of the stress tensor must vanish. This condition is expressed as

where σij and εij are the ijth components of the stress and strain tensors, respectively. σBO and σvib represent BO and vibrational (thermal) stresses and δij is the Kronecker delta. The set of lattice vectors [R(T, Pext)] is defined as

The temperature dependence of the vectors and their components has been omitted for the sake of compactness. Thus, the volume V is simply obtained as the determinant of the lattice matrix [R].

Subsequently, at equilibrium, the BO and vibrational stresses, also including Pext, must cancel each other, so that:

All this might be trivially generalized to the case of anisotropic external stress (not developed in this work, though).

The temperature-dependent internal strains (or atomic positions) are determined by minimizing the BO energy with respect to the atomic coordinates, which is equivalent to setting the BO forces to zero:

where \({{\mathcal{F}}}_{\kappa \alpha }^{{\rm{BO}}}\) denotes the BO force acting on atom κ along the Cartesian direction α, and tκα are the internal atomic positions. These positions might be relaxed while the external strains are held fixed. Thus, they become dependent on temperature and pressure implicitly, inheriting such dependence from the lattice parameter one. In practice, Eqs. (18) and (19) are enforced simultaneously, as in usual DFT geometry optimization. This determination of internal atomic coordinates from the vanishing derivative of the Born-Oppenheimer energy (not the temperature-dependent free energy) for a given external strain is a key step in the ZSISA-based methods.

In both v-ZSISA and ZSISA methods, the interpolation of free energies necessitates phonon spectra calculations at multiple volumes, with the number of calculations determined by the degrees of freedom (DOF) of the lattice. This process can be computationally demanding. For the case where only the volume is considered, or in the case of a cubic system with a single DOF for the lattice constant, at least five phonon spectra calculations are required to adequately fit an equation of state (EOS).

In systems with two DOFs, such as hexagonal, trigonal, or tetragonal lattices, a grid of 5 × 5 points (five for each DOF) is needed to interpolate a parabola to determine the free energy. As the number of DOFs increases, as in orthorhombic (3 DOFs), monoclinic (4 DOFs), and triclinic (6 DOFs) lattices, the number of necessary phonon calculations grows exponentially, scaling as 53, 54, and 56, respectively. Although these calculations are significantly fewer compared to the full QHA, they still pose substantial computational challenges for many systems.

To address this issue, various approximations can be employed to achieve comparable accuracy while reducing the computational cost of these calculations. In our previous work, we proposed approximations for v-ZSISA that utilize a Taylor expansion of Fvib to reduce the number of required phonon band structure calculations, while preserving the BO energies at multiple volumes. In that study, we examined the accuracy of the Taylor expansion approximation for the vibrational free energy and determined the necessary expansion order. Results indicated that, for most materials, including terms up to the second derivative, with three phonon band structure calculations, is sufficient to reproduce the results of the QHA. We referred to this approach as E∞Vib2 approximation. This finding provides a foundation for extending the advantages of E∞Vib2 to complex crystallographic systems with higher lattice degrees of freedom. In this work, we propose a new approximation method designed to accommodate systems with any number of degrees of freedom, from uniaxial to triclinic crystals.

Approximation of the vibrational free energy

In ZSISA, the lattice vectors correspond to the external strains, and the internal atomic coordinates, which minimize the atomic forces, are functions of these strains. To account for the vibrational contributions, the phonon free energy is expanded around a reference crystallographic lattice configuration [R•] using a Taylor series in terms of the strain deviation, stopping at second order.

According to the E∞Vib2 approximation, to derive the free energy from Eq. (12), the expression for EBO([R(T)]) is preserved without any approximations. To incorporate vibrational contributions, the phonon free energy Fvib is expanded around a reference crystallographic lattice configuration using a Taylor series in terms of strain deviation, stopped at the second order.

To facilitate the analysis, we define the strain matrix [εBO] as follows:

Here, \({\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\) are the normal strains along the x, y, and z directions, respectively, while the off-diagonal terms \({\varepsilon }_{xy}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{yz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\) represent shear strains.

Consider [RBO], the lattice vectors of the structure at the minimized BO energy. The deformed lattice vectors under applied strains can be defined as:

This matrix transformation captures how the lattice vectors deform under the influence of strain. In this formulation, the independent parameters are the strain components, allowing the equation to be expressed in terms of these strains.

The phonon free energy is then expressed as a Taylor series expansion around a reference lattice configuration [R•], that might be equal to the BO configuration or not, which is defined by the strain [εBO•]. The expansion is written in terms of the strain deviation, Δ•[εBO] = [εBO] − [εBO•], and is truncated at the second order:

where γ represents the indices {xx, yy, zz, xy, xz, yz}, corresponding to the non-zero components of \({\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}\).

With n representing the number of lattice degrees of freedom, the minimum number of configurations required to compute the Taylor expansion is 1 + 2n + n(n − 1)/2 = (n + 1)(n + 2)/2.

To compute the diagonal second derivatives \({\partial }^{2}{F}_{{\rm{vib}}}/{\partial ({\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}})}^{2}\) at the reference configuration [εBO•], three points are required for each value of γ: one at the central configuration [εBO•], and two additional configurations corresponding to deformations \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}})\). This results in a total of 1 + 2n configurations.

For the mixed second derivative \({\partial }^{2}{F}_{{\rm{vib}}}/\partial {\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}\partial {\varepsilon }_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), four points are typically needed in a simple approach corresponding to \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}\pm \delta {\varepsilon }_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), which are symmetrically distributed around [εBO•]. Instead, to minimize the number of required calculations, we arrange the points as follows: [εBO•], \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}})\), \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{BO}}})\), and \(([{\varepsilon }^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }]-\delta {\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}-\delta {\varepsilon }_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{BO}}})\). Three of these points overlap with those used to compute \({\partial }^{2}{F}_{{\rm{vib}}}/\partial {({\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}})}^{2}\) and \({\partial }^{2}{F}_{{\rm{vib}}}/\partial {({\varepsilon }_{{\gamma }^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{BO}}})}^{2}\), so only one additional configuration is required for each unique pair of γ and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\). This results in a total of n(n − 1)/2 extra points.

The choice of the reference lattice configuration [R•] plays an important role in ensuring accurate results. If [R•] falls within the expected range of lattice parameters across different temperatures and pressures, the calculations yield more reliable predictions. In our previous work on the v-ZSISA approach, we demonstrated that for materials with positive thermal expansion, shifting the reference structure away from the BO lattice in the direction of expansion improves accuracy. A similar strategy is applied here, where [R•] is adjusted based on the anticipated thermal expansion and pressure effects. When external pressure is applied, materials typically exhibit positive thermal expansion, yet their lattice parameters at zero temperature become smaller than the BO configuration at zero pressure. Therefore, selecting an appropriate [R•] that accounts for both thermal and pressure-induced effects is crucial for achieving precise results. In the present work, since we are considering low-pressure conditions, we focus primarily on the thermal expansion behavior. Accordingly, we introduce a positive shift in [R•] to ensure that our calculations yield the expected positive thermal expansion of the studied materials. However, at high pressures, an alternative approach is to define the BO structure as the lattice relaxed at that pressure, rather than at zero pressure. In this case, applying a positive shift in the direction of thermal expansion remains an effective strategy for accurately capturing the material’s behavior.

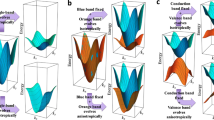

Figure 6 presents the points where phonon spectra calculations are performed for systems with 1, 2, and 3 degrees of freedom. The central blue point is the reference calculation [εBO•], while red points indicate the additional calculation needed to obtain finite difference data up to second degree for each degree of freedom \({\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}\), including cross derivatives. For 1, 2, and 3 DOF, the total number of calculations is 3, 6, and 10, respectively. Additionally, for systems with 4 and 6 DOF, 15 and 28 calculations are required. In Table 2, the number of degrees of freedom and the corresponding required number of phonon spectra calculations for various crystal structures are listed.

Representation of the points where phonon spectra calculations are performed, for configurations with a 1 DOF, b 2 DOF, and c 3 DOF. The blue point denotes the center of calculations (indicated by [εBO•]), while the red points represent the deformations required for each degree of freedom \({\varepsilon }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{BO}}}\). The total number of phonon spectra calculations for 1, 2, and 3 DOF is 3, 6, and 10, respectively.

At this stage, the vibrational contribution to \({F}_{{E}_{\infty }{\rm{V\; ib}}2}([R],T)\) from Eq. (12), is obtained by quadratic extrapolation over the n-dimensional surface. We are left with the BO contribution evaluation. If we perform a fit of the n-dimensional BO energy and determine the lattice parameters by minimizing the free energy, as expressed in Eq. (2), we face still a problem with the explosion of the number of such BO calculations. For example, using five interpolation points along each DOF to obtain a multidimensional BO grid, leads to a total number of configurations scaling as 5n, which grows exponentially with the number of DOF. For each of these 5n configurations, the BO energy must also satisfy the ZSISA condition, requiring full atomic position relaxation which is a computationally intensive process. In such an approach, one does not take benefit from the well-known easy computation of forces and stresses for the DFT BO calculation. To overcome this challenge, we propose an alternative approach based on thermal stress, which bypasses the need to fit an n-dimensional surface.

Thermal stress

Once Fvib is determined, Eq. (22), its derivatives can be evaluated directly as:

The thermal stress \({\sigma }_{\gamma }^{{\rm{vib}}}([R(T,{P}_{{\rm{ext}}})],T)\) is then obtained by:

where ε is the strain referenced specifically to the structure at which the derivative is performed, here, [R(T, Pext)], rather than the reference structure [RBO] used for εBO. The scaling factor dεBO/dε is necessary to ensure that strain is always derived from the specific structure under consideration. In Eq. (21), [R] is defined as a strain applied to RBO. However, this definition is not unique and the strain can be defined with respect to other configurations as well. In particular, the stress definition is the derivative evaluated at a state where the strain is zero. Therefore, this scaling is essential to maintain consistency.

To obtain the conversion factor, we define the applied strain [ε], by expressing [R] with respect to [R(T, Pext)]:

By substituting this relation into Eq. (21), we arrive at the following expression:

Differentiating with respect to [ε], we obtain for all values of k:

In the special case where [R] = [R(T, Pext)], the strain [ε] becomes zero. Let εBO(T, Pext) denote the strain corresponding to [R(T, Pext)]. Substituting this into the equation, the strain derivative simplifies to:

Using these thermal stresses, the BO stress can be evaluated via Eq. (18). Knowing the BO stress, the optimized BO configuration can be found by enforcing a constraint to maintain the correct stress.

The optimization of a geometric structure in order to have zero net atomic force and zero stress is common in all electronic structure packages. It is usually also possible to optimize a geometric structure under a given external pressure. The relaxation under an arbitrary external anisotropic stress might not be so common. This is an advanced feature implemented in ABINIT for a long time. One can relax both the lattice and atomic positions with a specified external stress tensor and specified atomic forces, using the usual algorithms49,50,51 for geometric relaxation. This is quite efficient and well-tested, and the computational effort is much lower than the computation of a full phonon band structure.

Due to symmetry constraints in various crystallographic structures, certain components of the strain matrix [ε] are inherently zero, meaning that not all stresses need to be computed. Table 2 lists the non-zero components of the strain matrix for different primitive cell structures, showing how these symmetry restrictions reduce the number of independent degrees of freedom in each configuration. In all crystals except monoclinic, triclinic, and anisotropic slab with 3 DOFs only normal (diagonal) strains are non-zero, with shear strains absent. For cubic crystals, all diagonal strains are equal, while in hexagonal, trigonal, and tetragonal crystals, two diagonal strains (εxx and εyy) are equal, allowing εzz to vary independently. The number of deformations required to determine the stress components follows the same approach discussed in the previous section.

After determining the thermal stress at a given temperature, the next step is to solve Eq. (18) self-consistently to obtain the final lattice configuration and corresponding properties.

Finding lattice parameters at T and P ext

The process of finding the optimal lattice parameters at a specified temperature T and external pressure Pext involves several iterative steps. We begin by generating deformations from an initial configuration εBO•, applying strains consistent with the system symmetries. From these, we determine the vibrational free energy and thermal stress, which provide the basis for identifying the optimal volume and lattice parameters.

The first step in this process is to obtain an initial guess for the lattice configuration [R]. Using this guess, we compute the thermal stress. Since this [R] does not necessarily correspond to the minimum free energy at temperature T, the condition in Eq. (18) is not satisfied initially.

To address this, we define a target stress as follows:

The value of \({\sigma }_{ij}^{{\rm{vib}}}([R],T)\) is determined from the quadratic approximation, so without doing any recomputation of the phonon band structure. The goal is to find a lattice configuration [R(T, Pext)] such that the target stress \({\sigma }_{ij}^{{\rm{target}}}([R(T,{P}_{{\rm{ext}}})],T,{P}_{{\rm{ext}}})\) matches the BO stress \({\sigma }_{ij}^{{\rm{BO}}}([R(T)])\). While the BO stress may differ for the initial guess, we can solve this self-consistently.

Using our initial guess, we compute the target stress. With this target stress, we relax the lattice and atomic positions by minimizing forces while imposing the constraint that the target stress is achieved, following the ZSISA approach. This relaxation step alters the lattice until the stress target is met.

After each relaxation, we recompute the thermal stress for the updated lattice and adjust the target stress accordingly. For each temperature, and (possibly) each external applied pressure, the process is repeated iteratively until the system converges, ensuring that the thermal stress and the BO stress match. The calculation flow for finding the lattice parameters [R(T, Pext)] is depicted in Fig. 7.

The process begins with an initial guess for the lattice configuration [R], followed by the computation of thermal and BO stresses. A target stress is defined based on thermal stress and Pext, and the lattice and atomic positions are relaxed iteratively until the target stress matches the BO stress and the BO forces are zeroed, ensuring convergence to the optimal lattice configuration.

Thermal expansion

Once the lattice parameters are obtained at each temperature and pressure, the thermal expansion of different lattice dimensions and angles can be computed using a finite-difference method. However, due to minor computational errors introduced by DFT or DFPT calculations, using a standard finite difference method or polynomial interpolation may result in noise in the computed thermal expansion.

To address this, an alternative approach based on Eqs. (8) and (10) can be employed to obtain thermal expansion with improved accuracy. By substituting Eqs. (4) and (22) into Eq. (8) with Eq. (10), we can express:

The first term, which represents the second derivative of the BO energy, can be computed using DFPT calculations of the elasticity tensor52. The elasticity tensor has 6 by 6 elements defined as:

Consequently, we can express:

where γ and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) denote the strain components under consideration, specifically {xx, yy, zz, yz, xz, xy}.

The second term, representing the second derivative of Fvib at the reference configuration [R(T, Pext)], is computed using finite difference methods applied to non-zero strain components. The third term corresponds to the second derivative of the volume with respect to strain components at [R(T, Pext)]. For off-diagonal components (\(\gamma\, \ne \,{\gamma }^{{\prime} }\), where γ and \({\gamma }^{{\prime} }\) are in {xx, yy, zz}), this term equals V(T, Pext), while all other terms are zero. Svib is determined from Eq. (10) on the same set of points as for the vibrational free energy. This allows its quadratic interpolation as a function of the strain tensor, and hence the computation of its derivative with respect to the strain tensor.

Thus, after determining [R[T, Pext]], a single DFPT calculation at the Γ point is sufficient to obtain the thermal expansion at each T and Pext.

Elastic constants

In addition to thermal expansion, the elastic constants at different temperatures and pressures can also be derived. The elastic constants are defined as:

We can express the free energy as a sum of the vibrational and BO energies:

Considering the symmetry constraints discussed in earlier sections, second derivatives of the vibrational free energy are omitted in cases where the first derivatives vanish. However, to determine the complete set of thermal elastic constants, additional calculations are necessary to account for all non-zero elements of the elastic tensor. To achieve this, additional deformations and phonon spectra calculations must be performed. Moreover, the deformations required for thermal expansion may differ from those needed to determine elastic constants. The distinction lies in the fact that, for thermal expansion, the use of crystal symmetries allows for a significant reduction in the number of required phonon spectra calculations.

For cubic and uniaxial structures, thermal expansion can be treated as a one- or two-dimensional problem, requiring only 3 and 6 deformations, respectively. In contrast, determining elastic constants necessitates treating 3 DOFs, similar to orthorhombic crystals, to fully evaluate the elastic tensor for xx, yy, zz components. Despite this, the number of calculations remains lower than that for orthorhombic structures due to symmetry considerations. Specifically, the 10 deformations needed for orthorhombic systems reduce to 4 and 7 for cubic and uniaxial crystals, respectively.

If the objective is to determine thermal expansion alongside elastic constants, the deformations required for elastic constants should be employed from the beginning. Table 3 summarizes the non-zero elastic constants for various crystal systems and the number of deformations required to compute them.

Monoclinic case

In the present subsection, we detail the equations for the monoclinic case. The equations for the remaining crystal and slab structures, as listed in Table 2, are provided in the Supplementary Note 2, Equations for Different Crystallographic Systems.

For sake of compactness, in this subsection, the Pext dependence of the components of the lattice vectors is not explicitly indicated, unlike their temperature dependence. For the monoclinic case, to simplify the calculations and corresponding implementation, we use a standardized definition of the primitive cell. In this standardized definition, the lattice has four degrees of freedom: \({\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), \({\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\), and \({\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}}\). Correspondingly, the lattice vectors for a simple monoclinic primitive cell can be defined as follows:

Therefore, the strain components for a monoclinic structure can be defined as:

and we can obtain the thermal stress as follows:

Computational details

The calculations for ground-state energies were performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT), while phonon frequencies were determined via Density-Functional Perturbation Theory (DFPT). Spin-orbit interactions were not included in these simulations. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials53 carefully validated against all-electron full-potential methods54,55 were sourced from the Pseudo-Dojo project56, and the exchange-correlation effects were described using the GGA-PBEsol functional57. Lattice parameters and atomic positions were optimized iteratively until forces on atoms were less than 10−5 Hartree/Bohr3 and stress components were below 10−8 Hartree/Bohr3. To produce smooth energy-volume curves, an energy cutoff smearing parameter of 1.0 Ha was applied58. Brillouin zone integrations were carried out with carefully chosen wavevector grids ensuring that errors in total energy remained under 1 meV per atom. The specific parameters used for each material are listed in Table 1. All computations were executed using the ABINIT software suite (version 9.10.3)59,60,61. The phonon density of states (PHDOS) was calculated through a Gaussian broadening approach with a smearing value of 1 cm−1 (approximately 4.5 × 10−6 Hartree), which is the default value for ABINIT versions above v9.10.

The reference structure, [R•] where a uniform strain shift is applied to the diagonal components. Specifically, the strain components are set as \({\varepsilon }_{xx}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }={\varepsilon }_{yy}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }={\varepsilon }_{zz}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }=0.005\). However, no shift is applied to the off-diagonal strain components (\({\varepsilon }_{xy}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet },{\varepsilon }_{xz}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet },{\varepsilon }_{yz}^{{\rm{BO}}\bullet }\)) since their thermal variation is not well understood. These components are related to changes in lattice angles rather than direct expansion or contraction, making it uncertain how they should be adjusted for thermal expansion.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. A publicly available implementation of the ZSISA method employed in this work is provided as part of the AbiPy packageat https://github.com/abinit/abipy.The repository includes Python scripts and a dedicated workflow for computing anisotropic, temperature-dependent properties from first principles. A fully documented example at https://abinit.github.io/abipy/flow_gallery/run_qha_zsisa.html for performing ZSISA calculations is included in the flow gallery section of the package, along with tools for automated post-processing and visualization.

Code availability

A publicly available implementation of the ZSISA method employed in this work is provided as part of the AbiPy package at https://github.com/abinit/abipy. The repository includes Python scripts and a dedicated workflow for computing anisotropic, temperature-dependent properties from first principles. A fully documented example for performing ZSISA calculations is included in the flow gallery section of the package, along with tools for automated post-processing and visualization. The workflow supports DFPT calculations of phonons, Born effective charges, dielectric tensors, and elastic constants, and incorporates recent developments in dynamical quadrupole calculations62, which enhance the accuracy of the Fourier interpolation of the dynamical matrix.

References

Barrera, G., Bruno, J., Barron, T. & Allan, N. Negative thermal expansion. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 17, R217 (2005).

Karunarathne, A. et al. Anisotropic elasticity drives negative thermal expansion in monocrystalline snse. Phys. Rev. B 103, 054108 (2021).

Lee, C.-H., Lin, C.-Y. & Chen, G.-Y. Uniaxial zero thermal expansion in low-cost Mn2Obo3 from 3.5 to 1250 k. Mater. Today Phys. 51, 101650 (2025).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Dove, M. T. Introduction to Lattice Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Lazzeri, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Ab initio study of Be (0001) surface thermal expansion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2096–2099 (1998).

Carrier, P., Wentzcovitch, R. & Tsuchiya, J. First-principles prediction of crystal structures at high temperatures using the quasiharmonic approximation. Phys. Rev. B 76, 064116 (2007).

Allen, P. B. Theory of thermal expansion: Quasi-harmonic approximation and corrections from quasi-particle renormalization. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 34, 2050025 (2020).

Mathis, M. A. et al. The generalized quasiharmonic approximation via space group irreducible derivatives. Phys. Rev. B 106, 014314 (2022).

Mathis, M. A. & Marianetti, C. A. Ab initio elasticity at finite temperature and stress in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. B 110, L140101 (2024).

Gong, X. & Dal Corso, A. High-temperature and high-pressure thermoelasticity of hcp metals from ab initio quasiharmonic free energy calculations: The Beryllium case. Phys. Rev. B 110, 094109 (2024).

Baroni, S., Giannozzi, P. & Testa, A. Green’s-function approach to linear response in solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1861–1864 (1987).

Gonze, X. First-principles responses of solids to atomic displacements and homogeneous electric fields: Implementation of a conjugate-gradient algorithm. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10337–10354 (1997).

Baroni, S., de Gironcoli, S., Corso, A. D. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Gonze, X., Rignanese, G. M. & Caracas, R. First-principle studies of the lattice dynamics of crystals, and related properties. Z. Kristallogr. 220, 458–472 (2005).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1 (2015).

Masuki, R., Nomoto, T., Arita, R. & Tadano, T. Ab-initio structural optimization at finite temperatures based on anharmonic phonon theory: Application to the structural phase transitions of batio3. Phys. Rev. B 106, 224104 (2022).

Allen, P. B. Anharmonic phonon quasiparticle theory of zero-point and thermal shifts in insulators: Heat capacity, bulk modulus, and thermal expansion. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064106 (2015).

Masuki, R., Nomoto, T., Arita, R. & Tadano, T. Anharmonic grüneisen theory based on self-consistent phonon theory: Impact of phonon-phonon interaction neglected in the quasiharmonic theory. Phys. Rev. B 105, 064112 (2022).

Allan, N. L., Barron, T. H. K. & Bruno, J. A. O. The zero static internal stress approximation in lattice dynamics, and the calculation of isotope effects on molar volumes. J. Chem. Phys. 105, 8300 (1996).

Taylor, M. B., Barrera, G. D., Allan, N. L. & Barron, T. H. K. Free-energy derivatives and structure optimization within quasiharmonic lattice dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 56, 14380 (1997).

Taylor, M. B., Sims, C. E., Barrera, G. D., Allan, N. L. & Mackrodt, W. C. Quasiharmonic free energy and derivatives for slabs: Oxide surfaces at elevated temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 59, 6742 (1999).

Liu, J. & Allen, P. Internal and external thermal expansions of wurtzite ZnO from first principles. Comput. Mater. Sci. 154, 251 (2018).

Masuki, R., Nomoto, T., Arita, R. & Tadano, T. Full optimization of quasiharmonic free energy with an anharmonic lattice model: Application to thermal expansion and pyroelectricity of wurtzite GaN and ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 107, 134119 (2023).

Lichtenstein, A. I., Jones, R. O., de Gironcoli, S. & Baroni, S. Anisotropic thermal expansion in silicates: A density functional study of beta-eucryptite and related materials. Phys. Rev. B 62, 11487 (2000).

Mounet, N. & Marzari, N. First-principles determination of the structural, vibrational and thermodynamic properties of diamond, graphite, and derivatives. Phys. Rev. B 71, 205214 (2005).

Palumbo, M. & Corso, A. D. Lattice dynamics and thermophysical properties of h.c.p. re and tc from the quasi-harmonic approximation. Phys. Status Solidi B 254, 1700101 (2017).

Liu, J. & Pantelides, S. T. Mechanisms of pyroelectricity in three- and two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207602 (2018).

Ritz, E. T. & Benedek, N. A. Interplay between phonons and anisotropic elasticity drives negative thermal expansion in pbtio3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 255901 (2018).

Ritz, E. T., Li, S. J. & Benedek, N. A. Thermal expansion in insulating solids from first principles. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 171102 (2019).

Li, Y., Hood, Z. D. & Holzwarth, N. A. W. Computational study of Li3BO3 and Li3BN2 II: Stability analysis of pure phases and of model interfaces with li anodes. Phys. Rev. Mat. 5, 085403 (2021).

Brousseau-Couture, V., Godbout, E., Côté, M. & Gonze, X. Zero-point lattice expansion and band gap renormalization: Grüneisen approach versus free energy minimization. Phys. Rev. B 106, 085137 (2022).

Skelton, J. M. et al. Influence of the exchange-correlation functional on the quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics of II-VI semiconductors. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 064710 (2015).

Nath, P. et al. High-throughput prediction of finite-temperature properties using the quasi-harmonic approximation. Comput. Mat. Sci. 125, 82 (2016).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tanaka, I. & Hug, G. First-principles phonon calculations of thermal expansion in Ti3SiC2, Ti3AlC2, and Ti3GeC2. Phys. Rev. B 81, 174301 (2010).

de-la Roza, A. O. & Luana, V. Treatment of first-principles data for predictive quasiharmonic thermodynamics of solids: The case of MgO. Phys. Rev. B 84, 024109 (2011).

de-la Roza, A. O. & Luana, V. Equations of state and thermodynamics of solids using empirical corrections in the quasiharmonic approximation. Phys. Rev. B 84, 184103 (2011).

Li, C. W. et al. Structural relationship between negative thermal expansion and quartic anharmonicity of cubic scf3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 195504 (2011).

Gupta, M. K., Mittal, R. & Chaplot, S. L. Negative thermal expansion in cubic ZrW2O8: Role of phonons in the entire Brillouin zone from ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 88, 014303 (2013).

Abraham, N. S. & Shirts, M. R. Thermal gradient approach for the quasi-harmonic approximation and its application to improved treatment of anisotropic expansion. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 5904 (2018).

Grüneisen, E. Theorie des festen zustandes einatomiger elemente. Ann. Phys. 344, 257–306 (1912).

Rostami, S. & Gonze, X. Approximations in first-principles volumetric thermal expansion determination. Phys. Rev. B 110, 014103 (2024).

See the Supplementary Information for additional information.

Vinet, P., Ferrante, J., Rose, J. H. & Smith, J. R. Compressibility of solids. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 92, 9319–9325 (1987).

Haggerty, R. P., Sarin, P., Apostolov, Z. D., Driemeyer, P. E. & Kriven, W. M. Thermal expansion of HFO2 and ZrO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 97, 2213–2222 (2014).

Dederichs, P. H., Blugel, S., Zeller, R. & Akai, H. Ground states of constrained systems: Application to cerium impurities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 2512 (1984).

Gonze, X., Seddon, B., Elliott, J., Tantardini, C. & Shapeev, A. Constrained density functional theory: A potential-based self-consistency approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 6099 (2022).

Schlegel, H. B. Optimization of equilibrium geometries and transition structures. J. Comput. Chem. 3, 214–218 (1982).

Bitzek, E., Koskinen, P., Gähler, F., Moseler, M. & Gumbsch, P. Structural relaxation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170201 (2006).

Nocedal, J. Updating quasi-newton matrices with limited storage. Math. Comput. 35, 773 (1980).

Hamann, D. R., Wu, X., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Metric tensor formulation of strain in density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035117 (2005).

Hamann, D. R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Lejaeghere, K. et al. Reproducibility in density functional theory calculations of solids. Science 351, aad3000 (2016).

Bosoni, E. et al. How to verify the precision of density-functional-theory implementations via reproducible and universal workflows. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 45–58 (2023).

van Setten, M. et al. The pseudodojo: Training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Comm. 226, 39–54 (2018).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Laflamme Janssen, J. et al. Precise effective masses from density functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 93, 205147 (2016).

Gonze, X. et al. First-principles computation of material properties: The abinit software project. Comput. Mat. Sci. 25, 478–492 (2002).

Gonze, X. et al. The abinit project: Impact, environment and recent developments. Comput. Phys. Comm. 248, 107042 (2020).

Romero, A. H. et al. Abinit: Overview, and focus on selected capabilities. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 124102 (2020).

Royo, M. & Stengel, M. Erratum: First-principles theory of spatial dispersion: Dynamical quadrupoles and flexoelectricity [phys. rev. x 9, 021050 (2019)]. Phys. Rev. X 12, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.12.019903 (2022).

Li, B., Woody, K. & Kung, J. Elasticity of mgo to 11 gpa with an independent absolute pressure scale: Implications for pressure calibration. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 111, B11206 (2006).

Karzel, H. et al. Lattice dynamics and hyperfine interactions in ZnO and ZnSe at high external pressures. Phys. Rev. B 53, 11425–11438 (1996).

Schulz, H. & Thiemann, K. Crystal structure refinement of Aln and GaN. Solid State Commun. 23, 815–819 (1977).

Wang, M., Shi, G., Qin, J. & Bai, Q. Thermal behaviour of calcite-structure carbonates: a powder X-ray diffraction study between 83 and 618 k. Eur. J. Mineral. 30, 939–949 (2018).

Grabowski, G., Lach, R., Pedzich, Z., Swierczek, K. & Wojteczko, A. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 18, 188–197 (2018).

Haines, J. & Léger, J. M. X-ray diffraction study of the phase transitions and structural evolution of tin dioxide at high pressure:ffrelationships between structure types and implications for other rutile-type dioxides. Phys. Rev. B 55, 11144–11154 (1997).

Aggarwal, R. L., Ripin, D. J., Ochoa, J. R. & Fan, T. Y. Measurement of thermo-optic properties of Y3Al5O12, Lu3Al5O12, YaiO3, LiYF4, LiLuF4, Ba2F8, KGD (Wo4)2, and Ky (Wo4)2 laser crystals in the 80–300k temperature range. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 103514 (2005).

McCullough, J. D. & Trueblood, K. N. The crystal structure of baddeleyite (monoclinic ZrO2). Acta Crystallogr. 12, 507–511 (1959).

El Maslout, A., Zanne, M., Jeannot, F. & Gleitzer, C. Préparation et structure d’un polyphosphure de magnesium: Mgp4. J. Solid State Chem. 14, 85–90 (1975).

Fortes, A. D. Thermal expansion of the Al2SiO5 polymorphs, kyanite, andalusite and sillimanite, between 10 and 1573 k determined using time-of-flight neutron powder diffraction. Phys. Chem. Miner. 46, 687–704 (2019).

Dubrovinsky, L. S. & Saxena, S. K. Thermal expansion of periclase (MgO) and tungsten (W) to melting temperatures. Phys. Chem. Miner. 24, 547–550 (1997).

Sumino, Y., Anderson, O. L. & Suzuki, I. Temperature coefficients of elastic constants of single crystal mgo between 80 and 1, 300 k. Phys. Chem. Miner. 9, 38–47 (1983).

Ibach, H. Thermal expansion of silicon and zinc oxide (ii). Phys. Status Solidi (b) 33, 257–265 (1969).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS, Belgium) through the PdR Grant no. T.0103.19 – ALPS. It is an outcome of the Shapeable 2D magnetoelectronics by design project (SHAPEme, EOS Project No. 560400077525) that has received funding from the FWO and FRS-FNRS under the Belgian Excellence of Science (EOS) program. Computational resources have been provided by the supercomputing facilities of the Université catholique de Louvain (CISM/UCL) and the Consortium des Equipements de Calcul Intensif en Fédération Wallonie Bruxelles (CECI), funded by the FRS-FNRS under Grant no. 2.5020.11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions