Abstract

The discovery of fluorescence materials with an inverted singlet-triplet (IST) energy gap, where the singlet excited state (S1) lies below the triplet excited state (T1), mark a transformative advancement in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) technology. However, designing the potential IST emitters are greatly challenging, and their IST energy gap, arising from double electron excitation, can only be accurately described by time-consuming post-Hartree-Fock (HF) methods, which blocks large-scale high-throughput screening speed. Here, we develop a four-orbital model to elucidate detailly the roles of double excitations in the IST formation, and establish two molecular descriptors (KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\)) based on exchange integral and molecular orbital energy. By these descriptors, we rapidly identify 41 IST candidates out of 3,486 molecules. The descriptors-aided approach achieves a screening success rate of 90% and reduces computational costs by 13 times compared to full post-HF calculations. Importantly, we predicted a series of excellent non-traditional near-infrared IST emitters from a dataset of 1028 compounds with emission wavelengths ranging from 852.2 to 1002.3 nm, which open new avenues for designing highly efficient near-infrared OLED materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) are widely used as light sources in smartphone and TV displays, as well as in lighting panels1. A major challenge in the development of OLEDs is to increase the internal quantum efficiency (IQE) to achieve brighter devices2. In traditional fluorescent OLEDs, only 25% of singlet excitons emit light due to spin statistics, while 75% of triplet excitons are wasted3. To enhance IQE, thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) has emerged. In TADF systems, triplet excitons are efficiently upconverted from the lowest triplet state (T1) to the lowest excited singlet state (S1) by a reverse intersystem crossing (rISC) process, resulting in a maximum IQE of close to 100%4. Nevertheless, TADF-OLEDs suffer from severe efficiency roll-off, such as triplet-triplet annihilation and triplet-polaron annihilation5,6. Thus, an ideal scenario would be thermodynamically favorable down-conversion with a negative singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔEST), accelerating the rISC process without requiring thermal activation, and effectively overcoming roll-off issues. Recently, azaphenalenes have gained considerable attention in the field of organic electronic materials because they exhibit an inverted singlet-triplet (IST) energy gap (a violation of Hund’s rule)7,8,9,10,11. And their high stability and color tunability make them ideal candidates for applications in organic light-emitting diodes, as recently demonstrated in experimental implementations12. The discovery and development of IST materials mark a transformative advancement in OLED technology. By enabling efficient rISC, these materials pave the way for next-generation displays and lighting solutions with unprecedented efficiency and performance.

Recently, many theoretical studies13,14,15,16,17 indicated that the participation of double electron excitation plays a necessary role in predicting Hund’s rule violations, resulting in that the time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT), a popular method for calculating the excited states, miserably failed in describing IST energy gap due to a lack of capturing double excitations. Thus, more accurate but expensive methods were adopted to predict negative ΔEST, such as spin-component-scaled coupled cluster doubles (SCS-CC2), equation-of-motion coupled cluster singles and doubles (EOM-CCSD), algebraic diagrammatic construction at the second order (ADC(2)), complete active space perturbation theory of second order (CASPT2), or n-electron valence-state perturbation theory of second order (NEVPT2)18,19,20,21,22. Although many accurate electronic structure calculations have been made, the mechanism of violations of Hund’s rule is still being explored and unclear. Moreover, expensive and time-consuming calculations severely decrease the large-scale high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) speed for discovering IST materials. Therefore, it is imperative to develop a fundamental model to disclose the mechanism of violations of Hund’s rule, and construct key molecular descriptors to characterize this property, in order to realize HTVS from a large-scale chemical space.

Here, we have developed a four-orbital model (FOM) with single and double electron excitations to elucidate the roles of double excitations, energy levels, and exchange integrals of involved orbitals in the formation mechanism of IST energy gap. And the IST mechanism is revealed that the ultra-small HOMO-LUMO orbital overlaps and the significantly large energy differences between orbitals involved in double excitation synergistically induce negative ΔEST. Based on this mechanism, two molecular descriptors (KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\)) are built to figure out the conditions for the occurrence of IST energy gap in azaphenalene derivatives. Using the two descriptors, 41 IST cores are rapidly screened from a chemical space of 3,486 cores. Relative to expensive post-HF calculations, the period of screening has been shortened by 13 times while the success rate of screening is as high as 90%. Importantly, a series of potential non-traditional near-infrared IST materials from a dataset of 1028 compounds are predicted with significantly intersystem crossing rate from T1 to S1 and radiative rates, compared to the systems that have been discovered so far. This research also marks the first time that IST materials have been predicted and proposed as near-infrared OLED emitters.

Results and discussion

Four-orbital model for IST molecules

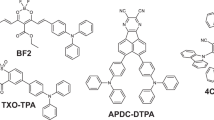

Firstly, eight typical molecules (1-8) with IST energy gap reported in the literatures7,8,9,19 and four common molecules (9-12) with normal positive singlet-triplet (PST) energy gap are selected as computational models to dissect the nature of electron transitions, as shown in Scheme 1. The geometries of 12 molecules are optimized at B3LYP/cc-pVDZ level in the S0 state, and their excited-state properties in the S1 and T1 states are analyzed by ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ method which was adopted in refs. 9,11,18 (more details are found in Supplementary Information). The resultant vertical excitation energy, ΔEST, and electronic transition properties of the S1 and T1 states are shown in Tables S1-S4. From Table S1, it is expectedly seen that the ΔEST values of molecules 1-8 are negative while those of molecules 9-12 are positive. As stated in the references7, the components of double excitation in both S1 and T1 states is very large with the values of around 10% for molecules 1-8, while its component is very small in the T1 state for molecules 9-12 (Table S2), which lead to their differences in ΔEST. For molecules 1-8, the single electron excitations mainly happen between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) with proportions larger than 80%, and the double excitations involve more orbitals, primarily including HOMO-2, HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, LUMO + 1 and LUMO + 2 (Tables S3 and S4). Further checking the properties of orbitals, it is found that HOMO-2 and HOMO-1, LUMO + 2 and LUMO + 1 are degenerate in energy, respectively; while the energy gaps between HOMO-1 and HOMO, LUMO + 1 and LUMO are significantly large, respectively, as seen in Table S5. Thus, for simplification, it is reasonable to extract the four orbitals, HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO + 1 from the multiple orbitals (Fig. 1a) to explore the mechanism of IST energy gap.

Then, a four-orbital model is constructed, including HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO, and LUMO + 1 (Fig. 1a). The single and double electron excitation processes and their wave functions in the FOM are given in Fig. 1b. Only one single excitation between HOMO and LUMO is considered in both S1 and T1 states based on the discussion above, and their wave functions are denoted as \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\) and\(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\), respectively. There take into account eight sets of double excitations, \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L}\rangle\), \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L+1,L+1}\rangle\),\(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H-1}^{L,L}\rangle\),\(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H-1}^{L+1,L+1}\rangle\),\(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L+1}\rangle\),\(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H-1}^{L,L+1}\rangle\), \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H-1}^{L,L}\rangle\) and \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H-1}^{L+1,L+1}\rangle\) for the S1 state, and four sets of double excitations \(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L+1}\rangle\), \(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H-1}^{L,L+1}\rangle\),\(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H-1}^{L,L+1}\rangle\) and \(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H-1,H}^{L+1,L+1}\rangle\) for the T1 state (see Fig. 1b).

Under the framework of HF theory, the wave functions (\(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\) and\(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\)) of the S1 and T1 states by single excitation configuration interaction (CIS) can be expressed, and their energy difference is solved as \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}=2{K}_{{\rm{HL}}}\) (the expression of the wave functions and the solution of the excited state energy are described in the “Methods” section), the \({K}_{{\rm{HL}}}\) is the exchange integral \((HL|LH)\) between the HOMO and LUMO, which is a non-negative number. Under the HF and double excitation configuration interaction (CID) approximation, the energies of S1 and T1 states are solved, denoted as \({E}_{1,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{2,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{3,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{4,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{5,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{6,{\rm{S}}}\), \({E}_{7,{\rm{S}}}\) and \({E}_{8,{\rm{S}}}\), and \({E}_{1,{\rm{T}}}\), \({E}_{2,{\rm{T}}}\), \({E}_{3,{\rm{T}}}\), and \({E}_{4,{\rm{T}}}\) corresponding to the order of states written above, respectively. And the 32 ΔEST are obtained in CID approximation (\(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\)) by combining these S1 and T1 states. Here, the energy gap \(\Delta {E}_{1,1}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) between \({E}_{1,{\rm{S}}}\) and \({E}_{1,{\rm{T}}}\) taken as an example in 32 \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), their wave functions \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L}\rangle\) and \(|{{3}\atop}\varPsi _{H,H}^{L,L+1}\rangle\) are expressed see “Methods” section, and the corresponding \({E}_{1,{\rm{S}}}\) and \({E}_{1,{\rm{T}}}\) are obtained as:

where \(\varepsilon\), \(J\) and \(K\) are energy, coulomb integral \((ii|aa)\), and exchange integral \((ia|ai)\) of orbitals, respectively. Then the energy difference \(\Delta {E}_{1,1}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) between \({E}_{1,{\rm{S}}}\) and \({E}_{1,{\rm{T}}}\) can be equal as:

the expression of the \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,1}\), \(\Delta {J}_{1,1}\) and \(\Delta {K}_{1,1}\) can be seen in Supplementary Information (SI). For other cases, the derivatives of wave functions and energies of the S1 and T1 states, and their energy gap \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) values are displayed in SI. The resultant \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) can be a positive or negative number. Therefore, the total energy gap (\(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{tot}}}\)) is the sum of \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), and whether its value is negative mainly depends on \(\varepsilon\), \(J\) and \(K\) of involved orbitals, as known from Eqs. 1–3 (Fig. 1a).

The inversion mechanism of IST molecules and molecular descriptors

The molecular \(\varepsilon\), \(J\), \(K\), \({E}_{{n},{\rm{S}},1\le {n}\le 8}\) and \({E}_{{n},{\rm{T}},1\le {n}\le 4}\) for molecules 1-12 are calculated at HF level (computational details seen in SI) and their values are summarized in Tables S6–S10. And the resultant \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}^{\mathrm{CIS}}\) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}^{\mathrm{CID}}\) are shown in Figs. 2a–c and S14–S25. From Fig. 2a, it is clearly seen that \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}\) values of molecules 1-8 (0.242 to 0.828 eV) are much lower than those of molecules 9-12 (1.220 to 3.471 eV), which is mainly caused by the KHL given in Table S8 due to \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}=2{K}_{{\rm{HL}}}\). The KHL is determined by the spatial overlap of the HOMO and LUMO. As shown in Fig. S13, the HOMO and LUMO are well-separated in space in molecules 1-8, whereas exhibiting significant overlap in molecules 9-12. These indicate that a small KHL or slight HOMO-LUMO overlap facilitates the formation of IST energy gap. Therefore, KHL is regarded as a descriptor for screening IST molecules, labeled as KS in this work. The validity of this descriptor has been demonstrated in reference10.

a The singlet excitation singlet-triplet gaps \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}\) of molecules 1-12. b, c 32 sets of double excitation singlet-triplet gaps modes for molecule 6 and 11. d–f The energy decomposition \(\Delta \varepsilon\) (\(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{5,2}\)), \(\Delta J\)(\(\Delta {J}_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {J}_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {J}_{5,2}\)) and \(\Delta K\) (\(\Delta {K}_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {K}_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {K}_{5,2}\)) of \(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{1,4}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{5,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\).

Let us move to double electron excitation properties, which is key to generate the IST. From Figs. S14-S25, it is found that in molecule 1-8, among 32 sets of \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), many values such as \(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) (−8.421 to −5.049 eV), \(\Delta {E}_{1,4}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) (–7.242 to −3.702 eV), and \(\Delta {E}_{5,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) (−6.002 to −0.132 eV), are negative, which are beneficial for the occurrence of IST energy gap. However, in molecules 9-12, there are only a few negative values and their values are more than −3.045 eV, which makes it difficult to nurture IST energy gap. For example, molecule 6 has not only eleven highly negative \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) modes with the lowest \(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) of -6.206 eV, but also a very small \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}\) of 0.244 eV, which is a typical IST molecule (Fig. 2b). In contrast, molecule 11 has four negative \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) modes (\(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{1,3}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{1,4}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{2,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\)) with the smallest \(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) value of -1.128 eV, and a large \(\Delta {E}_{{\rm{ST}}}^{{\rm{CIS}}}\) of 1.220 eV, making it a common PST molecule. To better illustrate all of this, we further analyze the \(\Delta {E}_{1,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), \(\Delta {E}_{1,4}^{{\rm{CID}}}\), and \(\Delta {E}_{5,2}^{{\rm{CID}}}\) with the lowest negative values, and display their components \(\Delta \varepsilon\) (\(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{5,2}\)), \(\Delta J\) (\(\Delta {J}_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {J}_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {J}_{5,2}\)) and \(\Delta K\)(\(\Delta {K}_{1,2}\), \(\Delta {K}_{1,4}\), \(\Delta {K}_{5,2}\)) in Figs. 2d-2f and Table S11-S13. It is found that the \(\Delta J\) and \(\Delta K\) are similar in molecules 1-12, with their values mainly ranging from −2.000 to 2.000 eV. Differently, the \(\Delta \varepsilon\) varies within a large range of −10.000–0.000 eV. It is very low in IST molecules (mostly below −4.000 eV), while it is much higher in PST molecules with values more than ca. -3.500 eV. Based on these results, it can be concluded that \(\Delta \varepsilon\) is the most critical factor in generating the IST energy gap. Look into the definition of \(\Delta \varepsilon\) given in the SI, they are \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,2}={\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}+1}+2({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}-1}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}})\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,4}=2({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}+1})+{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}-1}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}}\), \(\Delta {\varepsilon }_{5,2}=2({\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}-1}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}})\). Trigged from these, we come up with\({O}_{{\rm{D}}}={\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{L}}+1}+{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}-1}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{H}}}\) as the other molecular descriptor for screening IST molecules.

So far, two molecular descriptors KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\), which are related to single electron and double electron excitations respectively, have been established for screening IST molecules. The competition between the exchange integral between orbitals in single excitation (positive value) and the energy gap between orbitals in double excitation (negative value) determines the occurrence of IST molecules. In addition, the python code for computing KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) is provided in SI, all parameters of KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) are calculated at HF level.

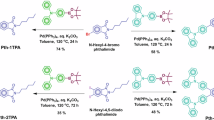

High-throughput virtual screening using these descriptors

From the above discussion, it can be known that small HOMO-LUMO exchange integral and double excitation are profit to induce the inversion of singlet and triplet states in energy. Heterocyclic triazene derivatives were reported to exhibit well-separated HOMO and LUMO and character of double excitations, which are the candidates for thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials23,24. Therefore, nine triazene cores are selected here to generate 3468 molecular cores by substituting different atoms in the ring (see Fig. 3a) using RDKit25. Then the high-throughput virtual screening is performed using KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) descriptors, and confirmed by post-HF methods, and the workflow is shown in Fig. 3b. Step I is the establishment of database. All the initial structures generated from 3486 SMILES strings are optimized and their frequencies are analyzed at B3LYP/cc-pVDZ level, and the unstable structures with imaginary frequencies are removed, 3156 stable structures are preserved. Step II is the molecular screening by molecular descriptors. The orbital energies of 3156 molecules are extracted and the descriptors KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) are calculated, and the 338 molecules are screened as potential IST candidates when they meet KS < 0.400 eV and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\,\)< −3.000 eV. Step III is the verification of results. The S1 and T1 vertical excitation energy \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1), \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)T1) and vertical ∆EST are computed by using EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ and SC-NEVPT2(8,8)/cc-pVDZ methods to identify the final IST molecules. Finally, the emission properties of the winners are investigated.

Firstly, we analyze the KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) of 35 IST molecules reported in the literature and identify the conditions required to generate the IST energy gap (Figs. S26–S27). The results in Fig. S27 indicate that the values of KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) are almost always less than 0.400 eV and −3.000 eV, respectively, for all molecules. Therefore, KS\(\, <\)0.400 eV and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}} <\)−3.000 eV are used as the criteria for identifying IST molecules. According to these conditions, 338 molecules are screened from a total of 3156, as shown in Fig. 4a. Subsequently, the EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ method is adopted to calculate the vertical excitation energies of the S1 and T1 states and their differences ∆EST at the optimized S0-geometry for these 338 molecules, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. From Fig. 4b, it is evident that 72 out of the 338 candidates exhibit negative ∆EST and are identified as IST molecules. Furthermore, the multireference SC-NEVPT2 (8,8)/cc-pVDZ method is used to refine the selection, resulting in 41 IST molecules from these 72 candidates (Fig. 4c). Due to limitations in computational resources, the choice of the SC-NEVPT2 (8,8) active space represents a balanced compromise between computational cost and accuracy. This descriptor-assisted screening method (DASM) takes a total of 2.8 × 103 h to screen 41 IST molecules from a combined pool of 3156 molecules.

a The KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\) values of 3156 candidates. b The \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) values of 338 candidates at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level. c The \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) values of 72 candidates at SC-NEVPT2 (8,8)/cc-pVDZ level. d The \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) values of 3156 candidates at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level. e The \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) values of 117 IST candidates at SC-NEVPT2(8,8)/cc-pVDZ level. f The CPU times consumed by the DASM and the FCSM.

To validate the accuracy and efficiency of the descriptors KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\), the EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ method is directly applied to calculate the \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) for all 3156 molecules. Among these, 117 molecules (S36-S152 in Fig. S28) are identified with negative \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) (Fig. 4d). The values of the \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1), \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)T1) and ∆EST for these 117 molecules are listed in Table S14. As illustrated in Table S14, the \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) ranges from 0.521 to 4.161 eV, and the \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)T1) varies between 0.551 and 4.609 eV, resulting in \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) ranging from -1.427 to -0.0002 eV. Similarly, the SC-NEVPT2(8,8) method is employed to further refine the selection, yielding 46 IST molecules from these 117 molecules (Fig. 4e and Table S15). To check the impact of the active space, the SC-NEVPT2(12,12) is also used for M1-M46, and the results (Table S16) are similar to those of SC-NEVPT2 (8,8). The molecular structures and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) energies at the SC-NEVPT2(8,8)/cc-pVDZ level for these 46 IST molecules (M1-M46) are shown in Scheme 2. This full-calculation screening method (FCSM) takes a total of 3.6 × 104 h to screen 46 IST molecules from the pool of 3156 molecules, which is 13 times longer than the time required for the DASM described above. If the results of 46 IST molecules identified by FCSM are regarded as the standard, the success rate of DASM is close to 90%. These findings confirm that the DASM is both reliable and highly efficient.

For practical applications of IST molecules in OLEDs, their emissive properties are further investigated. The geometric structures of the S1 and T1 states are optimized at TD-B3LYP/cc-pVDZ level, and the emission energy (\(\Delta E\)(S1\(\to\)S0)), oscillator strength (f(S1\(\to\)S0)), and adiabatic \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) are calculated at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level for the 46 IST molecules. The results are given in Table S17 and Fig. S29. It is seen that the adiabatic \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) of all molecules are negative, expect for M43, the \(\Delta E\)(S1→S0) ranges from 0.160 to 1.316 eV, and the f(S1\(\to\)S0) varies from 0.0000 to 0.0019. Among these, M3 is a potential IST core with \(\Delta E\)(S1\(\to\)S0) of 1.041 eV and f(S1\(\to\)S0) up to 0.0019. Based on M3, 1,028 candidate molecules with fewer than 28 atoms are generated by introducing 42 substituents at different positions (Fig. 5a and S30). The S0-geometries are optimized at B3LYP/cc-pVDZ level, and the corresponding vertical excitation energies \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1), \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)T1) and \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) are calculated at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level, as depicted in Fig. 5b. There appear 794 molecules with negative ΔEST. Herein, 476 molecules with \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1)≥ 1.5 eV are extracted for further calculations of emission energy and oscillator strength (Fig. 5c). As clearly shown in Fig. 5c, compared to M3, the f(S1\(\to\)S0) values are promoted by an order of magnitude, up to 0.0178, which is a high value reported for near-infrared IST molecules in the references.

a Molecular structures of 1028 candidates based on M3 cores. b The vertical \(\Delta {E}_{\mathrm{ST}}\) values and \(\Delta E\)(S0\(\to\)S1) of 1028 candidates at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level. c The oscillator strength and \(\Delta E\)(S1\(\to\)S0) of 476 IST molecules at EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level. d Schematic diagram of the excited-state processes and the photophysical parameters of I9. e The photoluminescence spectra of molecules I1-I9.

Furthermore, the luminescence properties of molecules I1-I9 (Fig. S31) with the highest f(S1\(\to\)S0) are investigated. The related energies, spin-orbit couplings, the rate constants of excited-state decays, and prompt and delayed photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY) are summarized Tables S18-S21 and Fig. 5d. And the emissive spectra are plotted in Fig. 5e with the assignments of some typical peaks in Fig. S32. Their emissive spectra of these candidates are localized in the range from 862.4 to 1002.2 nm, and the spectral broad shapes mainly stem from the synergistic vibronic progressions of multiple modes. Their radiative rate constants kr range from 1.0\(\times\)106 s-1 to 9.7\(\times\)106 s-1, which is the largest ones for IST systems. Their nonradiative rate constant from S1 to S0 state knr varies from 1.0\(\times\)107 s-1 to 6.0\(\times\)108 s-1, which is considerably small for near-infrared systems with so narrow energy gaps. As expected, their intersystem crossing rate constants from T1 to S1 (\({k}_{{{\rm{T}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{S}}}_{1}}\)) always overwhelms the corresponding \({k}_{{{\rm{S}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{T}}}_{1}}\), which reflect the advantages of IST molecules. As a result, they exhibit high PLQYs. More surprisingly, among the similar IST molecules, there appear prompt and delayed fluorescence in I4 and I9 while there is only prompt fluorescence in the others. Among these compounds, I9 has the highest PLQY of 3.5%, in which the prompt and delayed PLQY are 2.5% and 1.0%, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5d. Overall, a series of potential non-traditional near-infrared IST emitters are predicted, and their quantum efficiencies are satisfactory compared with traditional near-infrared systems.

Summary

In this work, we have devised a four-orbital model (FOM) to elucidate in detail the roles of single and double excitations in the IST formation in azaphenalene derivatives. Importantly, under this model we have constructed two descriptors (KS and \({O}_{{\rm{D}}}\)) based on molecular frontier orbital energy and exchange integral, which can be easily obtained by simple quantum chemistry calculation for molecules in the ground state. Out of a dataset of 3,486 molecules, 41 IST molecular cores are identified using the descriptor-assisted screening method, and verified with the state-of-the-art methods. Compared with the results of the full-calculation screening method, the accuracy of descriptor-assisted method is 90% with a speed nearly 13 times faster. Furthermore, starting from the IST molecular core with the largest oscillator strength, 1028 candidate molecules are generated by introducing 42 substituents, and their photophysical properties are investigated by combining post-HF method and thermal vibration correlation function rate theory. And a series of potential near-infrared IST emitters are predicted with emission wavelength ranging from 852.2 to 1002.3 nm and the highest PLQY of 3.5% at 880.7 nm, which can match and outperform the currently reported traditional near-infrared fluorescence systems in quantum efficiencies. This work provides a deeper understanding of the origin of energy inversion in IST molecules, and offers valuable insights for future molecular design. This work not only marks the first time that IST materials have been predicted and proposed as near-infrared OLED emitters but also paves the way for practical applications in areas such as biomedicine and component determination. However, these descriptors would limit to triangulene-based systems, and not suitable for other types of IST systems. In the future, we will develop general descriptors and machine learning models for high-throughput screening IST candidates in more diverse datasets.

Methods

The wave functions and excitation energy expression

The wave functions \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\) and \(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H}^{L}\rangle\) of the S1 and T1 states by CIS theory can be expressed as:

Here, the \(\bar{H}\), \(\bar{L}\) and \(H\), \(L\) indicate orbitals with α and β spin components, respectively. The corresponding energies of singlet and triplet states can be calculated as:

And their energy difference is:

The wave functions \(|{{1}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L}\rangle\) and \(|{{3}\atop}\Psi _{H,H}^{L,L+1}\rangle\) of the S1 and T1 states by CID theory can be expressed as:

For the detailed expression of \(\Delta {E}_{1,1}^{\mathrm{CID}}=\Delta {\varepsilon }_{1,1}+\Delta {J}_{1,1}+\Delta {K}_{1,1}\) as:

Electronic structure calculation

The geometries of all molecules in their S0, S1 and T1 states are optimized at the (TD) B3LYP/cc-pVDZ level using the Gaussian 16 program package26. The vertical excitation energies and the configurations of single and double excitations for molecules 1-12 in both S1 and T1 states are determined using the ADC(2)/cc-pVDZ method within the Q-Chem 5.2 software27, the energy calculation at the EOM-CCSD/cc-pVDZ level is also performed on Q-Chem 5.2. The SC-NEVPT2/cc-pVDZ method utilizing CASSCF calculations based on MP2 natural orbitals in ORCA 6.0.1 software package28, the SOC matrix elements based on T1-geometries are computed at SC-NEVPT2/cc-pVDZ level using ORCA 6.0.1 package. Additionally, the Coulomb and exchange integrals for all molecules are analyzed at the HF/cc-pVDZ level, based on B3LYP-optimized geometries, employing the Multiwfn program29. We carry out the reorganization energy analysis between the S0 and S1 states at S1-geometries using the molecular material property prediction package MOMAP 2022B30,31,32. The computational system of the server is based on the CPU model: Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8160 processor.

Photophysical properties calculation

The photoluminescence quantum yields of the prompt and delayed components (Φp and Φd) are given by33:

Here \({{\boldsymbol{\Phi }}}_{{{\rm{S}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{T}}}_{1}}\) and\({{\boldsymbol{\Phi }}}_{{{\rm{T}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{S}}}_{1}}\) are the quantum efficiencies for ISC and reverse ISC, respectively. The radiative decay \({k}_{{\rm{r}}}\) from S1 to S0 state is computed using \({k}_{{\rm{r}}}=f\Delta {E}^{2}/1.499\)34, in which f and \(\Delta E\) are the oscillator strength and emission energy in cm-1, respectively. The non-radiative decay \({k}_{{\rm{nr}}}\) from S1 to S0 state, \({k}_{{{\rm{S}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{T}}}_{1}}\) from S1 to T1 state and \({k}_{{{\rm{T}}}_{1}\to {{\rm{S}}}_{1}}\) from T1 to S1 state, and the emissive spectra are evaluated via the thermal vibration correlation function (TVCF) method in MOMAP 2022B.

Data availability

The authors declare that the necessary data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper (and its Supplementary Information files). All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The Python code for calculating molecular descriptor is available at Supplementary information.

Code availability

The Python code for calculating molecular descriptor is available at Supplementary information.

References

Hong, G. et al. Brief history of OLEDs-Emitter development and industry milestones. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005630 (2021).

Gu, G. et al. High-external-quantum-efficiency organic light-emitting devices. Opt. Lett. 22, 396–398 (1997).

Shuai, Z. & Peng, Q. Organic light-emitting diodes: theoretical understanding of highly efficient materials and development of computational methodology. Natl. Sci. Rev. 4, 224–239 (2017).

Uoyama, H. et al. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Li, P., Feng, L., Li, G. & Bai, Q. Effects of electron donating ability of substituents and molecular conjugation on the electronic structures of organic radicals. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 39, 202–207 (2023).

Murawski, C., Leo, K. & Gather, M. C. Efficiency roll-off in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 25, 6801–6827 (2013).

de Silva, P. Inverted singlet-triplet gaps and their relevance to thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 5674–5679 (2019).

Ehrmaier, J. et al. Singlet-triplet inversion in heptazine and in polymeric carbon nitrides. J. Phys. Chem. A 123, 8099–8108 (2019).

Pollice, R., Friederich, P., Lavigne, C., Gomes, G. D. P. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Organic molecules with inverted gaps between first excited singlet and triplet states and appreciable fluorescence rates. Matter 4, 1654–1682 (2021).

Omar, O. H., Xie, X., Troisi, A. & Padula, D. Identification of unknown inverted singlet-triplet cores by high-throughput virtual screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19790–19799 (2023).

Pollice, R., Ding, B. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Rational design of organic molecules with inverted gaps between the first excited singlet and triplet. Matter 7, 1161–1186 (2024).

Aizawa, N. et al. Delayed fluorescence from inverted singlet and triplet excited states. Nature 609, 502–506 (2022).

Sancho-García, J. C. et al. Violation of Hund’s rule in molecules: predicting the excited-state energy inversion by TD-DFT with double-hybrid methods. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 034105 (2022).

Drwal, D. et al. Role of spin polarization and dynamic correlation in singlet-triplet gap inversion of heptazine derivatives. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 7606–7616 (2023).

Ghosh, S. & Bhattacharyya, K. Origin of the failure of density functional theories in predicting inverted singlet-triplet gaps. J. Phys. Chem. A 126, 1378–1385 (2022).

Blaskovits, J. T., Corminboeuf, C. & Garner, M. H. Excited-state Hund’s rule violations in bridged [10]- and [14] annulene perimeters. J. Phys. Chem. A 128, 10404–10412 (2024).

Bedogni, M., Giavazzi, D., Maiolo, F. D. & Painelli, A. Shining light on inverted singlet-triplet emitters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 902–913 (2024).

Sobolewski, A. L. & Domcke, W. Are heptazine-based organic light-emitting diode chromophores thermally activated delayed fluorescence or inverted singlet-triplet systems?. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 6852–6860 (2021).

Ricci, G., Sancho-García, J.-C. & Olivier, Y. Establishing design strategies for emissive materials with an inverted singlet-triplet energy gap (INVEST): a computational perspective on how symmetry rules the interplay between triplet harvesting and light emission. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 12680–12698 (2022).

Blaskovits, J. T., Garner, M. H. & Corminboeuf, C. Symmetry-induced singlet-triplet inversions in non-alternant hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202218156 (2023).

Jorner, K., Pollice, R., Lavigne, C. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Ultrafast computational screening of molecules with inverted singlet-triplet energy gaps using the Pariser-Parr-Pople semiempirical quantum chemistry method. J. Phys. Chem. A 128, 2445–2456 (2024).

Loos, P. F., Lipparini, F. & Jacquemin, D. Heptazine, cyclazine, and related compounds: chemically-accurate estimates of the inverted singlet-triplet gap. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 11069–11075 (2023).

Hatakeyama, T. et al. Ultrapure blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: efficient HOMO-LUMO separation by the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 28, 2777–2781 (2016).

Suresh, S. M., Hall, D., Beljonne, D., Olivier, Y. & Zysman-Colman, E. Multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters based on heteroatom-doped nanographenes: recent advances and prospects for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908677 (2020).

RDKit. https://github.com/rdkit/rdkit.

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2016).

Shao, Y. et al. Advances in molecular quantum chemistry contained in the Q-Chem 4 program package. Mol. Phys. 113, 184–215 (2015).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system-version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Peng, Q., Yi, Y., Shuai, Z. & Shao, J. Toward quantitative prediction of molecular fluorescence quantum efficiency: role of Duschinsky rotation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9333–9339 (2007).

Peng, Q. et al. Theoretical predictions of red and near-infrared strongly emitting X-annulated rylenes. J. Chem. Phys. 134, 074510 (2011).

Shuai, Z. Thermal vibration correlation function formalism for molecular excited state decay rates. Chin. J. Chem. 38, 1223–1232 (2020).

Goushi, K., Yoshida, K., Sato, K. & Adachi, C. Organic light-emitting diodes employing efficient reverse intersystem crossing for triplet-to-singlet state conversion. Nat. Photonics 6, 253–258 (2012).

Hilborn, R. C. Einstein coefficients, cross sections, f values, dipole moments, and all that. Am. J. Phys. 50, 982–986 (1982).

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply indebted to Prof. Sergey Bokarev, Prof. Wolfgang Domcke, and Xuexiao Yang for valuable discussions and acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 22325305 and 22273105), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Sciences (XDB0520103), National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFB3614300) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant Nos. E2E40307X2 and E2ET0309X2). We gratefully acknowledge WQ & UCAS Research Academy Intelligent Computing Center (WRA-ICC) for providing computation facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.P. designed the research program and analyzed the computational data. Y.P. implemented the computational program, derived the initial theoretical results, and wrote the original manuscript. J.W. and J.Y. provided some software support. Q.P. and Y.P. reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, Y., Wang, J., Yang, J. et al. Molecular descriptors for high-throughput virtual screening of fluorescence emitters with inverted singlet-triplet energy gaps. npj Comput Mater 11, 310 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01792-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01792-2