Abstract

Surrogate modeling techniques have become indispensable in accelerating the discovery and optimization of high-entropy alloys (HEAs), especially when integrating computational predictions with sparse experimental observations. This study systematically evaluates the training and testing performance of four prominent surrogate models—conventional Gaussian processes (cGP), Deep Gaussian processes (DGP), encoder-decoder neural networks for multi-output regression and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—applied to a hybrid dataset of experimental and computational properties of the 8-component HEA system Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V. We specifically assess their capabilities in predicting correlated material properties, including yield strength, hardness, modulus, ultimate tensile strength, elongation, and average hardness under dynamic/quasi-static conditions, alongside auxiliary computational properties. The comparison highlights the strengths of hierarchical deep modeling approaches in handling heteroscedastic, heterotopic, and incomplete data commonly encountered in materials science. Our findings illustrate that combined surrogate models such as DGPs infused with machine-learned priors outperform other surrogates by effectively capturing inter-property correlations and by assimilating prior knowledge. This enhanced predictive accuracy positions the combined surrogate models as powerful tools for robust and data-efficient materials design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) are multicomponent alloys with five or more principal elements in high concentrations that offer a vast compositional design space and often exhibit exceptional mechanical properties1,2. The exploration of this space is challenged by limited experimental data and complex composition-property relationships1,3. Accordingly, data-driven surrogate models have become invaluable in accelerating HEA discovery by predicting material properties3,4,5,6.

Surrogate models serve as computationally efficient approximations of complex structure-property relationships and are widely used to accelerate materials discovery. Gaussian processes (GPs) provide calibrated uncertainty estimates, making them effective for sparse, high-fidelity datasets7, while multi-task extensions and co-kriging allow for correlated output modeling8. Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs) extend this capability to hierarchical, nonlinear functions9, offering a potential advantage in capturing complex material behavior. In contrast, tree-based methods like eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)10 or encoder-decoder mapping of inputs to outputs11 are often easier to scale and tune but lack native uncertainty quantification unless modified. As a result, model selection should be guided by data availability, dimensionality, and the need for uncertainty modeling in the optimization loop. Hybrid modeling strategies that combine the strengths of neural networks (for representation learning) and probabilistic models (for uncertainty quantification) offer a promising path forward–leveraging expressive power while retaining decision-making confidence in sparse-data regimes.

Recent studies have combined machine learning with high-throughput calculations and experiments to identify novel alloys with targeted properties12. In particular, Bayesian optimization (BO) frameworks for materials design rely on accurate surrogate models to guide experiments toward optimal candidates13. In our previous work, we addressed the discovery of HEAs with specific properties by using advanced GP models (conventional Gaussian process (cGP), multi-task Gaussian process (MTGP), and DGP) within a BO loop14. We also explored DGP surrogates in that context, which—along with MTGPs—were able to capture the coupled trends in bulk modulus and coefficient of thermal expansion, while also accelerating the search for promising alloy compositions in Fe-Cr-Ni-Co-Cu HEA space. In particular, Khatamsaz et al.15 employed a MTGP approach to jointly model the yield strength (YS), the Pugh ratio and the Cauchy pressure in a simulated Mo-Ti-Nb-V-W alloy system, enabling efficient multi-objective optimization for high strength and ductility. Building on the successes of these optimization-focused studies, we now shift our attention toward a detailed evaluation of surrogate modeling techniques. Moving beyond optimization, the present work assesses how well different models fit a hybrid data set consisting of both experimental measurements and computational predictions. In particular, we compare multiple modeling approaches, conventional single-layer cGPs, DGPs, a custom encoder-decoder neural network for multi-output regression, and XGBoost, on their ability to learn the composition-property relationships in the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V HEA system. DGPs are a hierarchical extension of GPs that can capture complex, nonlinear mappings by composing multiple GP layers9, and we hypothesize that this added depth enables DGPs to model heteroscedastic and nonstationary behavior often observed in materials data better than a standard cGP. The encoder-decoder model, on the other hand, represents a deterministic deep learning approach: it “encodes” alloy compositions into a learned feature representation and “decodes” this latent vector to simultaneously predict multiple properties16.

As a baseline, we include a conventional XGBoost model for each property to illustrate the limitations of ignoring inter-property correlations and data uncertainty. The material data set used in this study spans the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V composition space, an 8-element HEA system of interest for its high configurational entropy and the potential for exceptional mechanical performance. This data set is assembled from disparate sources, having experimentally calculated properties as “main tasks” and some additional computationally estimated properties as “auxiliary tasks”. The inclusion of these additional “tasks” provides additional information that can be used by multiple output models to improve predictions of the main experimental properties, analogous to multifidelity or multisource learning in other contexts17,18.

Given the diverse origins of this dataset, not every alloy composition has a complete set of measurements; some samples have missing experimental values, while corresponding computational predictions may exist, and vice versa. This reflects a common situation in materials science, where gathering a complete set of property data for every sample is infeasible, and one must utilize incomplete and noisy information from various sources. Consequently, the challenges posed by this HEA dataset underscore the need for surrogate models capable of handling correlated output, heteroscedastic uncertainties, and missing data. Moreover, many of the mechanical properties in HEAs are interdependent—for example, hardness and YS are often correlated since they both relate to underlying strengthening mechanisms. A multi-output model can exploit such correlations to improve the prediction accuracy for each task, especially when one property has abundant data and another is data sparse8,16.

In addition to the challenges of missing data, noise levels, and predictive difficulties can vary between properties. Experimental measurements like elongation may have higher uncertainty or variability than, say, valence electron concentration (VEC, which is deterministically computed), leading to heteroscedastic behavior. The sources and treatment of uncertainty differ across the various properties considered in this work. For experimentally measured properties–such as hardness, modulus, or elongation–uncertainty is quantified using the standard deviation across three replicate measurements per alloy, capturing variability due to factors like local microstructural differences and measurement noise. These properties can exhibit heteroscedasticity across the dataset as their variance may depend on composition or processing conditions. In contrast, some descriptors used in this study are computed rather than experimentally measured, and have different uncertainty profiles. For example, VEC is computed deterministically using a rule-of-mixtures approach, scaled by a factor of 100 prior to modeling for numerical stability, and currently does not include an associated uncertainty estimate in our framework. However, we recognize that VEC, like any empirical descriptor, has model-form uncertainty based on its simplifying assumptions. Similarly, stacking fault energy (SFE) values used in this study were generated using a machine learning model trained on density functional theory (DFT) data, as described by Khan et al.19, while YS estimates were computed using the Curtin–Varvenne solid solution strengthening model20. Both of these computed descriptors inherit uncertainty from their underlying models and training data, although explicit uncertainty quantification was not included. To support future use and analysis, we plan to release uncertainty estimates alongside the dataset–including statistical uncertainties for experimental data and model-based estimates for computed properties–to enable more robust uncertainty-aware modeling and optimization across the HEA design space. Traditional single-task cGPs can struggle in this setting because they assume a single noise variance per task and cannot borrow strength from related tasks. In contrast, co-regionalized DGP frameworks can naturally handle task-specific noise and allow information transfer across properties21. Likewise, DGPs can effectively model input-dependent noise by virtue of their layered construction—the output of one GP layer (with its own variance) feeds into the next, allowing the model to represent variability that changes with composition22. Finally, neural networks can also accommodate heteroscedasticity by learning complex nonlinear interactions, though they typically require larger datasets to generalize well and often treat noise implicitly (e.g., through regularization techniques). Importantly, both the DGP and the encoder-decoder model can handle missing outputs during training, as they are trained with a loss (or likelihood) that includes only observed data for each task, enabling the use of all available partial information.

Despite the advances in surrogate modeling and optimization for HEAs, a notable gap remains: while numerous studies have demonstrated the successful application of individual surrogate models for property prediction and optimization, a robust, non-parametric, multi-property model being able to predict uncertainty as well on a unified, multi-property alloy dataset is lacking3,4,5,6. In this paper, our aim is to fill this gap by systematically benchmarking DGPs, DGPs with encoder-decoder prior, encoder-decoder multi-output architectures, cGPs, and XGBoost on the BIRDSHOT dataset. Through this comparison, we evaluate the ability of each method to fit the complex property landscape of HEAs and faithfully capture property correlations and uncertainties. The insights from this study provide guidance on selecting surrogate models for future materials informatics efforts, especially in scenarios with sparse, noisy, and multisource data. We show that appropriately accounting for task correlations and data heterogeneity—via advanced models like DGPs—can markedly improve predictive performance, thereby enabling more reliable downstream tasks such as Bayesian alloy design and multiobjective optimization.

Results

BIRDSHOT data

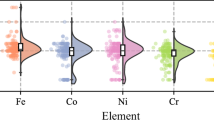

The BIRDSHOT dataset is a comprehensive, high-fidelity collection of mechanical, structural, and compositional data covering over 100 distinct high-entropy alloy (HEA) compositions in the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V system23,24—see Fig. 1. It is the product of two complementary experimental campaigns—the first campaign has already been thoroughly described in ref. 23—each targeting slightly different regions of the compositional space and emphasizing different mechanical performance metrics. The first campaign focused on a six-element FCC HEA system (Al-Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V), while the second campaign expanded the design space to include Mn and Cu. Together, these efforts explored a filtered design space consisting of tens of thousands of feasible alloys, ultimately selecting and synthesizing more than 100 unique compositions. These alloys were chosen to span a broad and representative portion of the chemically complex HEA landscape, under multiple design constraints related to phase stability, thermal, and mechanical properties.

The dataset results from a multi-institutional effort combining alloy synthesis, mechanical testing across various strain rates (including nanoindentation, strain rate jump tests, small punch tests, and SHPB), and structural and compositional verification (EBSD, XRD, SEM-EDS). This integrated workflow ensures fidelity and consistency across the high-dimensional alloy space explored.

Alloys in the dataset were synthesized using vacuum arc melting (VAM) under strictly controlled and standardized protocols23. Each 30–35 g ingot was produced from high-purity elements, flipped and remelted multiple times to ensure chemical homogeneity, and subjected to homogenization followed by mechanical working (hot forging or cold rolling and recrystallization). These protocols were applied uniformly across both campaigns, ensuring consistency in processing history. Compositional accuracy was confirmed via SEM-EDS with average deviations from targets below 1%, while structural phase verification was carried out using XRD and EBSD. This uniformity enables direct comparison of properties across compositions without the confounding effects of processing variability.

Each alloy underwent a suite of structural and mechanical characterizations, with properties measured from subsamples taken from the same physical ingot. This eliminates ambiguity often introduced when comparing properties measured on nominally identical but independently prepared samples. As a result, the dataset provides true cross-property, multimodal measurements–such as YS, ultimate tensile strength (UTS), hardness, strain-rate sensitivity, and modulus–directly coupled to each alloy’s verified composition and microstructure.

Mechanical behavior was characterized across a wide range of strain rates. Miniaturized tensile tests were conducted to extract yield and ultimate strengths and strain hardening ratios. High-strain-rate nanoindentation, including strain rate jump tests, was used to determine rate-sensitive hardness and modulus. Dynamic performance was further evaluated via small punch tests, split Hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) compression testing, and Laser-Induced Projectile Impact Testing (LIPIT), enabling mechanical assessment from 10−4 to 107 s−1. Microstructural analyses using SEM, EBSD, and XRD verified single-phase FCC stability and ruled out the presence of deleterious secondary phases.

A key innovation of the BIRDSHOT effort lies in its use of a Bayesian discovery framework25 to guide experimental exploration. This closed-loop approach integrates machine learning, physical modeling, and experimental data to iteratively select the most informative alloy compositions. At each iteration, a surrogate model–typically a cGP–is trained on prior experimental data to predict material properties across the compositional space, along with associated uncertainty. An acquisition function, such as Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI), is used to rank candidate alloys by their potential to improve the Pareto front defined by multiple objectives. A batch of promising compositions is selected, synthesized, tested, and then fed back into the model for the next iteration. This strategy balances exploration of under-sampled regions with exploitation of high-performing areas and led to the discovery of a robust multi-objective Pareto set while sampling less than 0.2% of the filtered design space23.

The two campaigns established a rigorously curated, multi-modal, and multi-objective dataset that not only provides broad coverage of a chemically rich compositional space, but also captures cross-property correlations at an unprecedented level of fidelity. This makes the BIRDSHOT dataset a valuable resource for both mechanistic understanding and data-driven modeling of complex alloy systems—in this specific case, the FCC HEA space.

In addition to experimental data, the dataset includes a suite of simulation-derived descriptors computed for each alloy composition. VEC was calculated using a rule-of-mixtures approximation, based on atomic fractions of constituent elements, and subsequently scaled by a factor of 100 prior to model training for numerical stability. YS estimates were obtained using the Curtin–Varvenne model20, which computes solid solution strengthening based on atomic size and modulus mismatch among elements. SFE values were predicted using a machine learning model trained on DFT data, developed by Khan et al. 19, providing composition-sensitive estimates of SFE across the HEA design space.

Depth of penetration, representing a measure of ballistic resistance, was predicted through finite element simulations using ABAQUS. These simulations modeled the impact of a spherical alumina projectile onto a cylindrical HEA target traveling at 500 m/s. Each alloy was modeled using a Cowper-Symonds viscoplasticity framework, calibrated with experimental stress-strain data from quasi-static tensile and SHPB experiments. While descriptors such as VEC, SFE, and predicted YS are available for all alloy compositions in the dataset, depth of penetration is currently available for a subset of alloys tested for SHPB tests.

Effect of elemental composition on experimental properties

The BIRDSHOT dataset24 currently contains detailed information on 147 non-equimolar Cantor HEAs, focusing on their composition, processing parameters, and mechanical properties. Each alloy is characterized by its elemental fractions (Al, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, V) and evaluated for key properties such as YS, UTS, tension elongation, and hardness. The dataset also includes computationally derived parameters such as SFE, VEC, and Varvenne YS providing insights into the alloys’ mechanical behavior and stability. For example, the YS of the alloys ranges from 310 to 537 MPa, while tension elongation varies from 18.3% to 25.7%. First-order statistics for this dataset is summarized in Table 1.

The dataset contains 22 features, capturing both experimental and computational results, and is suitable for developing predictive models, investigating structure-property relationships, and advancing the discovery of novel high-performance alloys. Despite its comprehensive nature, the dataset includes minor missing data across key properties. Measured properties like YS and UTS have 141 complete entries (~96%), while computed parameters such as SFE and VEC; and nano-indentation hardness are available for 131 samples (~89%). Feature complexity was calculated as the sum of the absolute skewness and the absolute excess kurtosis (∣skewness∣ + ∣kurtosis − 3∣) for each feature.

The experimental data set contains data points scattered throughout the composition space. The selection strategy of the data points is based on BO of two campaigns, as mentioned in the methods section. The available data points are described in the above-mentioned Table 1.

To further investigate correlations among properties, we report pairwise plots in Fig. 2. Our goal is to demonstrate that considering correlation among the properties yields a better fit for the surrogates. The pairplot reveals strong positive correlations between YS, hardness, and UTS, emphasizing their interdependent nature. Ductility (Elong_T) shows a clear inverse relationship with these strength-related properties, highlighting the common strength-ductility trade-off observed in HEAs1.

These visual analyses establish the foundational understanding of the underlying correlations and elemental influences critical to interpreting the surrogate modeling performance discussed subsequently.

Comparison of model performances

In this study, we systematically evaluated seven distinct surrogate modeling approaches to accurately predict material properties within the Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V HEA space Fig. 3. The methods assessed include: (i) DGP incorporating priors trained on all tasks (ii) DGP incorporating priors trained on only main objectives, (iii) DGP without priors utilizing all tasks, (iv) DGP without priors trained solely on main objectives, (v) cGP with no correlated kernel, (vi) XGBoost and (vii) encoder-decoder model used for regression tasks11.

A unique aspect of our modeling approach involves incorporating prior knowledge derived from a previously trained encoder-decoder neural regression model. We fixed the train-test split between the two models (DGP and encoder-decoder) for the cases where DGPs use encoder-decoder as prior. This prevents data leakage, ensuring that our test set is totally unseen by the DGP models during training.

This prior was injected into the DGP models by subtracting predicted prior values from the training data outputs, thereby focusing the DGP on modeling residuals, i.e., delta learning. After the prediction phase, the priors were re-added to generate the final predictions, which were then visualized and evaluated. This technique leverages existing domain knowledge and has the potential to significantly enhance predictive performance, especially in sparse and noisy data environments16,26.

To comprehensively evaluate model performance, we utilized multiple standard regression metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean squared error (RMSE), symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE), and mean averaged error (MAE). Additionally, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was computed to assess the consistency of predicted rankings relative to actual data, providing insights into the models’ abilities to preserve order, which is critical for practical materials selection scenarios.

Table 2 final reported metrics were obtained by averaging results from five different randomized train-test splits to ensure robust and reliable performance evaluation. Specifically, an 80-20 train-test split was employed for the DGP, GP, XGBoost models, and encoder-decoder model. For the DGP models, the optimal reduction parameter identified during the hyperparameter tuning stage was consistently applied across these evaluations.The values of the metrics reported in Table 3 contain the mean and the standard deviation over the five train-test splits in the form of “mean ± standard deviation”.

In the following section, we will provide detailed comparisons and discussions of the performance metrics across the seven evaluated surrogate models, elucidating the strengths, limitations, and practical implications of each approach for multi-task prediction in HEAy datasets.

The comparative analysis across surrogate models, as detailed in Table 3, provides valuable insights into the efficacy and suitability of different modeling strategies within HEA surrogate modeling. Among the evaluated models–XGBoost, cGP, DGP variations (HDGP NP-All, HDGP NP-Main, HDGP P-All, HDGP P-Main), and the encoder-decoder neural network–the HDGP models incorporating prior knowledge (HDGP P-Main, HDGP P-All) consistently exhibited superior performance across the majority of tasks of primary experimental interest.

Specifically, the HDGP-P-Main and HDGP-P-All models showed marked improvements in prediction accuracy, reflected by the lowest RMSE and SMAPE values, alongside the highest R2 and Spearman rank correlation coefficients for critical experimental properties such as YS, UTS, elongation, hardness, and average hardness under dynamic/quasi-static conditions. Both of these models have mostly similar performance. For depth of penetration, modulus, hardness, elongation, YS, and SFE, HDGP-P-All performed best. For UTS/YS, UTS and avg HDYN/HQS HDGP-P-Main performed better. We note that HDGP-P-All had encoder-decoder priors for all tasks except Varveillien YS, SFE, and VEC. The HDGP-P-All surpassed the performance of HDGP-P-Main in most of the tasks and it can possibly be attributed to the addition of auxiliary tasks. Auxiliary task may help the DGP generalize better by giving information about the correlation between tasks14. The exceptional performance of HDGP P-All and HDGP-P-Main over non-prior models can be primarily attributed to the integration of encoder-decoder model as informative priors in the training process11. Any GP-based model without prior defaults to constant mean in unseen region. The addition of prior makes the model converge to the prior at a specific input compositions rather than one constant value at all compositions26. This makes the predictions more robust for out-of-distribution points. It also helps in leveraging expert knowledge or other parametric ML models, like encoder-decoder in our case. This is also illustrated in Fig. 4 for the case of hardness in HDGP-NP-All and HDGP-P-All. For points inside the red circle, in the model with prior(b), the predictions don’t default to a constant value in far-away regions. Thus, they are close to the actual values. Whereas in the model without prior(a), the mean tend to move toward a constant value, making the predictions defer from the actual values.

Interestingly, the performance of prior-based models was followed by encoder-decoder, HDGP-NP-Main, and HDGP-NP-All, having intermediate performance. They performed better than XGBoost and cGP but performed worse than DGP models having priors. In between these two DGPs, HDGP-NP-All was the better one for most of the tasks. It had Varveillien YS, SFE, and VEC as auxiliary tasks. Due to the hierarchical and deep structure of DGPs, the HDGP model effectively leveraged these auxiliary tasks, exploiting inter-task correlations to enhance predictive accuracy for main tasks compared to HDGP-NP-Main. This multi-task learning capability, intrinsic to DGP frameworks, allows the model to extract valuable latent information from auxiliary properties, thus significantly improving prediction robustness in sparse and noisy experimental settings9,22. Encoder-decoder model performed better than HDGP-NP-Main and HDGP-NP-All, but it does not have the capacity of uncertainty quantification, so may not be useful in materials design or discovery campaigns on its own. Moreover, the encoder-decoder neural network model, while theoretically capable of capturing complex nonlinearities, exhibited poorer generalization performance compared to DGPs with prior. This underperformance likely stems from its deterministic and parametric nature, sensitivity to hyperparameter settings, and susceptibility to overfitting when trained on smaller datasets16. Also, the encoder-decoder model had much larger number parameters, making it prone to overfitting for a small dataset like ours.

Contrastingly, the cGP and XGBoost models demonstrated several limitations despite their frequent use in regression tasks. Although XGBoost delivered competitive performance in specific auxiliary tasks (e.g., VarvYS), it notably lacked the flexibility and uncertainty quantification capabilities inherent to GP-based methods. XGBoost, being a parametric, tree-based ensemble model, can easily overfit limited datasets, reducing its generalizability in complex materials design problems10. Similarly, cGP, despite their nonparametric Bayesian framework and robust uncertainty quantification, failed to match the performance of HDGP variants due to their inability to explicitly model inter-task correlations and input-dependent uncertainty through hierarchical structures. cGP assumes independence among outputs, limiting its ability to transfer knowledge effectively across related properties7.

This trend in performance is also visible in train set metrics as attached in the Supplementary File. Although XGBoost had the best training metric mostly, it was very closely followed by HDGP-P-All and HDGP-P-Main. These two DGP models performed better than cGP and encoder-decoder model in fitting the train data as well, affirming their superior generalization capability.

It is important to contextualize our modeling approach within the framework of BO for materials discovery, as this fundamentally differs from traditional machine learning paradigms that emphasize broad generalization. The 147-composition BIRDSHOT dataset, while appearing modest in size, is entirely typical for BO-driven materials discovery campaigns where each experimental data point represents substantial synthesis and characterization investment27,28. In BO applications, surrogate models serve not as standalone predictive tools but as acquisition function components that guide sequential experimental design to efficiently navigate complex design spaces29. For this purpose, the model’s ability to correctly rank candidate materials by their predicted performance and associated uncertainty–quantified through Spearman rank correlation–is far more critical than absolute predictive accuracy30. Our results demonstrate Spearman correlations consistently above 0.8-0.9 for critical properties, indicating excellent ranking performance suitable for guiding experimental campaigns. Similar BO studies in materials science routinely operate with comparable dataset sizes, as the methodology explicitly prioritizes efficient exploration over comprehensive coverage31,32. Rather than claiming broad extrapolative generalization across the entire 8-component HEA space, our approach demonstrates effective interpolative prediction within the explored compositional region, combined with well-calibrated uncertainty estimates that naturally increase for compositions distant from training data. This represents the standard operating paradigm for automated experimentation and self-driving laboratory applications, where datasets of 100-200 samples are typical33.

To address the interpretability of our best-performing HDGP-P-All model and understand the underlying relationships between elemental composition and material properties, we conducted a comprehensive feature importance analysis using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)34. SHAP values provide a unified framework for interpreting machine learning model predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature to individual predictions, thereby offering insights into the model’s decision-making process. Figure 5 presents SHAP summary plots for all predicted properties in our HEA system, where each point represents a single prediction, with the x-axis showing the SHAP value (impact on model output) and the color indicating the feature value magnitude. Positive SHAP values increase the predicted property value, while negative values decrease it. We used a model-agnostic KernelSHAP estimator on the trained HDGP-P-ALL posterior for each target,

The figures illustrate SHAP values for (a) varveillian yield strength, (b) SFE, (c) average VEC, (d) YS, (e) UTS, (f) UTS/YS ratio, (g) elongation, (h) hardness, (i) modulus, (j) average HDYN/HQS and (k) depth of penetration. Each dot represents a single prediction, with the x-axis showing the SHAP value (impact on model output) and color indicating feature value magnitude (red = high, blue = low). Features are ordered by importance (sum of absolute SHAP values).

Across nearly all mechanical targets, Al and V exhibit the largest absolute SHAP magnitudes, indicating they are primary drivers of model outputs. Cr and Cu frequently contribute negatively to strength-related metrics but can aid ductility-related ones (e.g., Elongation). UTS/YS is negatively influenced by higher Al and V, but positively by Fe. Ni, Co, and Mn play secondary yet property-dependent roles, often modulating predictions in narrower bands. Collectively, these patterns align with metallurgical intuition: strong solid-solution strengtheners (e.g., V, Al) raise yield/ultimate strengths, whereas elements that reduce SFE (e.g., Cu, Cr) can trade off strength for ductility and hardness. These SHAP analyses (i) validate that HDGP-P-ALL captures physically plausible element-property relationships and (ii) offer actionable guidance for alloy design (e.g., increasing V/Al to boost strength while monitoring Cr/Cu levels to balance ductility).

In summary, HDGP P-All emerges as the optimal modeling choice for predicting correlated material properties within HEA datasets, efficiently addressing common challenges of sparsity, noise, and missing data. Its hierarchical, Bayesian nature ensures robust uncertainty quantification and superior predictive performance, making it particularly suitable for guiding experimental design in materials informatics. It utilizes auxiliary tasks to generalize better. Also, it leverages the knowledge of encoder-decoder model as prior to perform better, providing promise as a hybrid model capable of uncertainty estimation and better generalization. Moreover, Fig. 6 illustrates the parity plots and relevant test metrics for one specific train-test split in the case of HDGP-P-All model, showing excellent accuracy. It is to be noted that the error bars in the plots are representative of the standard deviation as predicted by the model. The parity plots for all the other models and tables of train metrics are provided in the Supplementary File.

Discussion

In this work, we systematically evaluated several surrogate modeling techniques, including cGP, DGP, encoder-decoder neural networks, and XGBoost, to predict multiple correlated material properties in the complex Al-Co-Cr-Cu-Fe-Mn-Ni-V HEA system. Our analysis demonstrated that the hierarchical DGP model, which incorporates informative priors and is trained across both main and auxiliary tasks (HDGP P-All), consistently outperformed other models in key mechanical properties, such as YS, UTS, elongation, hardness, modulus, and dynamic/quasistatic hardness ratios.

The superior performance of HDGP P-All can be primarily attributed to its hierarchical architecture and effective leverage of inter-task correlations, as well as the strategic integration of prior knowledge derived from a pre-trained encoder-decoder model. This combination enabled the model to robustly address common challenges inherent in materials informatics datasets, including heteroscedastic uncertainties, heterotopic observations, and missing data. In contrast, cGP, XGBoost, and deterministic encoder-decoder networks exhibited notable limitations, primarily due to their inability to explicitly quantify uncertainties, susceptibility to overfitting, and limited capacity for modeling correlations among multiple outputs.

In general, our findings strongly advocate the adoption of advanced hierarchical surrogate models with uncertainty-awareness, such as DGP in materials discovery and optimization campaigns. These models provide substantial advantages by effectively capturing complex property interdependencies, robustly managing uncertainty, and maximizing predictive accuracy even with sparse and heterogeneous data sets. Future research should further optimize the integration of domain-specific prior knowledge and enhance computational efficiency to facilitate broader applications of these advanced methods in accelerated materials development.

Methods

Conventional Gaussian processes (cGP)

cGPs provide a flexible Bayesian framework widely used for regression tasks due to their ability to explicitly quantify predictive uncertainty7. Given a set of observations \({\mathcal{D}}=\{{{\bf{X}}}_{N},{{\bf{y}}}_{N}\}\), where XN = (x1, x2, …, xN) are the input points and yN = (y1, y2, …, yN) are their corresponding outputs, a GP is fully defined by its mean function μ(x) and the covariance function \(k({\bf{x}},{{\bf{x}}}^{{\prime} })\). For an unseen input point x*, the GP posterior prediction is given by:

with predictive mean and variance:

Here, K(XN, XN) denotes the covariance matrix computed from the kernel k for the training inputs, k(x*, XN) is the covariance vector between the test point x* and the training inputs, and \({\sigma }_{n}^{2}\) represents the observation noise variance. A commonly adopted kernel is the squared exponential (RBF) kernel:

which characterizes the similarity between input points based on their Euclidean distance, with ℓ controlling the length scale. This description of conventional GPs lays the foundational groundwork for understanding more complex modeling approaches.

Deep Gaussian processes (DGP)

Building directly on the fundamental concepts introduced above, DGPs extend conventional GPs by incorporating a hierarchical structure. This hierarchical arrangement enables the modeling of more intricate, non-linear relationships and input-dependent uncertainties, thereby addressing challenges that arise in complex datasets9,22. In a DGP with L hidden layers, the generative model is described by:

Each function f(i) is modeled as a GP with its own covariance structure, effectively capturing different levels of abstraction from the input data. Given the increased computational complexity of DGPs, training often involves variational inference techniques. Specifically, the model is optimized by maximizing the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO):

where Q represents the variational distribution that approximates the true posterior. Gradient-based optimization methods are typically employed to balance model fit and complexity22,35. This progression from conventional to deep GP structures demonstrates the evolution from simple probabilistic modeling to a framework capable of handling greater nonlinearity and uncertainty.

Isotopic vs. Heterotopic data

Continuing from the dataset description, we now address a key data structuring concern relevant to the modeling techniques presented earlier. In multi-output GP modeling, distinguishing between isotopic and heterotopic data is essential due to its implications on model performance and uncertainty quantification21.

Isotopic data, where all tasks are observed at the same set of input points, provides a straightforward scenario:

where T is the number of tasks. Conversely, heterotopic data arises when tasks are observed at different input points:

leading to sparsely and partially missing observations for some tasks. This characteristic is particularly common in materials informatics due to the varying feasibility or cost of data collection for different properties17,18.

By incorporating the capability to handle heterotopic data, DGP models offer a significant advantage. Their ability to leverage inter-task correlations not only maximizes information utility from incomplete datasets but also enhances predictive accuracy and uncertainty quantification—key factors for accelerating materials discovery. The clear delineation between isotopic and heterotopic data thus bridges the theoretical modeling framework with the practical challenges encountered in experimental datasets.

The DGP models implemented in this work consist of two-layered variational GPs, each configured with 10 latent GPs and implemented using BoTorch36. To ensure numerical stability and consistent predictions, all input and output variables were scaled prior to model fitting and subsequently descaled to original units during result visualization.

A critical hyperparameter specific to the DGP architectures evaluated is the reduction parameter, illustrated schematically in Fig. 7. The reduction parameter dictates the dimensionality reduction performed between the first and second layers of the DGP, calculated as the number of tasks minus a chosen integer. Selecting an optimal reduction parameter is essential, as it influences the capacity of the DGP to capture inter-task correlations and the complexity of latent representations. We systematically explored different values of this hyperparameter by fitting models with varying reduction parameters and selected the best-performing value based on cross-validation accuracy metrics. We plotted the Spearman rank coefficient and RMSE over different reduction parameters and chose the reduction parameter that yielded the highest Spearman rank coefficient and lowest RMSE value. The results for HDGP-P-All are reported in Fig. 8. The plot shows that a reduction parameter of 5 achieves the lowest RMSE and highest Spearman's rank co-efficient over the test set on average over all tasks. So, reduction parameter of 5 was chosen for the model. The other relevant hyperparameters of the DGP models include kernels, the optimizer used for training and the number of latent GPs in each layer. We used RBF kernel for the first layer and a Matern kernel for the second layer. 10 latent GPs were used in each layer. We used the Adam optimizer with 0.01 learning rate for training. The models were trained using NVIDIA A100 GPU. Training of each instance of the DGP models takes roughly 5 min with CUDA acceleration.

Encoder-decoder model for tabular data learning

The encoder-decoder framework is a powerful approach for learning complex input-output relationships in regression tasks and has shown competitive performance compared to tree-based methods on small datasets11. Its performance improves with larger datasets, enabling the model to capture more nuanced patterns and generalize better to unseen inputs. Although the BIRDSHOT dataset is relatively small, we used the encoder-decoder model to benchmark its performance against deep GPs, as both are capable of modeling non-linear mappings and uncertainty in high-dimensional spaces. Training involves minimizing the difference between the predicted and actual values using a loss function, typically optimized with gradient-based methods. After training, the model can generalize to new inputs and produce corresponding predictions. Although the model offers strong predictive performance, its internal representations are often not interpretable. However, explainability can be improved using attention mechanisms, feature attribution methods, and visualization tools. Different neural architectures, including but not limited to dense networks, disjunctive normal form networks (DNF-Nets), and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can be used at the core of the encoder and decoder. These architectures can enhance accuracy by capturing detailed patterns and filtering noise. In this study, we used regularized dense networks, also known as feedforward networks. Non-linear activation functions like ReLU or sigmoid introduced flexibility and regularization methods such as L2 penalties were used to reduce overfitting.

Data availability

The code and data supporting the results of this study can be found in the following GitHub repository as a Google Colaboratory notebook. The encoder-decoder model for tabular learning and regression tasks can be found in https://github.com/vahid2364/DataScribe_DeepTabularLearningThe DGP and other models can be found inhttps://github.com/sheikhahnaf/DGP_with_EncoderDecoderPrior.

Code availability

The code and data supporting the results of this study can be found in the following GitHub repository as a Google Colaboratory notebook. The encoder-decoder model for tabular learning and regression tasks can be found in https://github.com/vahid2364/DataScribe_DeepTabularLearningThe other models can be found in https://github.com/sheikhahnaf/DGP_with_EncoderDecoderPrior.

References

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Elkatatny, S., Abd-Elaziem, W., Sebaey, T. A., Darwish, M. A. & Hamada, A. Machine-learning synergy in high-entropy alloys: a review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 33, 3976–3997 (2024).

Wen, C. et al. Machine learning assisted design of high entropy alloys with desired property. Acta Mater. 170, 109–117 (2019).

Wang, J., Kwon, H., Kim, H. S. & Lee, B.-J. A neural network model for high entropy alloy design. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 60 (2023).

Gao, T., Gao, J., Yang, S. & Zhang, L. Data-driven design of novel lightweight refractory high-entropy alloys with superb hardness and corrosion resistance. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 256 (2024).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K.Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (MIT Press, 2006).

Bonilla, E. V., Chai, K. M. & Williams, C. Multi-task Gaussian process prediction. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 20 (ACM, 2008).

Damianou, A. & Lawrence, N. D. Deep Gaussian processes. In Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, 207–215 (2013).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: a scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (ACM, 2016).

Attari, V. & Arroyave, R. Decoding non-linearity and complexity: deep tabular learning approaches for materials science. Digit. Discov. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5DD00166H (2025).

Rao, Z. et al. Machine learning–enabled high-entropy alloy discovery. Science 378, 78–85 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Multi-objective Bayesian optimization for materials design and discovery. J. Mater. Res. 35, 900–920 (2020).

Alvi, S. M. A. A. et al. Hierarchical Gaussian process-based Bayesian optimization for materials discovery in high entropy alloy spaces. Acta Mater. 289, 120908 (2025).

Khatamsaz, D., Vela, B. & Arroyave, R. Multi-objective Bayesian alloy design using multi-task Gaussian processes. Mater. Lett. 351, 135067 (2023).

Ban, Y., Hou, J., Wang, X. & Zhao, G. An effective multitask neural networks for predicting mechanical properties of steel. Mater. Lett. 353, 135236 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.135236 (2023).

Khatamsaz, D. et al. Efficiently exploiting process-structure-property relationships in material design by multi-information source fusion. Acta Mater. 206, 116619 (2021).

Ghoreishi, S. F., Molkeri, A., Arroyave, R., Allaire, D. & Srivastava, A. Efficient use of multiple information sources in material design. Acta Mater. 180, 260–271 (2019).

Khan, T. Z. et al. Towards stacking fault energy engineering in FCC high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 224, 117472 (2022).

Varvenne, P., Luque, A. & Curtin, W. A. Theory of strengthening in FCC high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 118, 164–176 (2016).

Álvarez, M. A., Rosasco, L. & Lawrence, N. D. Kernels for vector-valued functions: a review. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 4, 195–266 (2012).

Salimbeni, H. & Deisenroth, M. Doubly stochastic variational inference for deep Gaussian processes. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4591–4602 (ACM, 2017).

Hastings, T. et al. Accelerated multi-objective alloy discovery through efficient Bayesian methods: application to the FCC high entropy alloy space. Acta Mater. 297, 121173 (2025).

Mulukutla, M. et al. Illustrating an effective workflow for accelerated materials discovery. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 13, 453–473 (2024).

Arroyave, R. et al. A perspective on Bayesian methods applied to materials discovery and design. MRS Commun. 12, 1037–1049 (2022).

Vela, B., Khatamsaz, D., Acemi, C., Karaman, I. & Arróyave, R. Data-augmented modeling for yield strength of refractory high entropy alloys: a Bayesian approach. Acta Mater. 261, 119351 (2023).

Frazier, P. I. A tutorial on Bayesian optimization. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.02811 (2018).

Shahriari, B., Swersky, K., Wang, Z., Adams, R. P. & De Freitas, N. Taking the human out of the loop: a review of Bayesian optimization. Proc. IEEE 104, 148–175 (2016).

Garnett, R. Bayesian Optimization (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

Jones, D. R., Schonlau, M. & Welch, W. J. Efficient global optimization of expensive black-box functions. J. Glob. Optim. 13, 455–492 (1998).

Ling, J., Hutchinson, M., Antono, E., Paradiso, S. & Meredig, B. High-dimensional materials and process optimization using data-driven experimental design with well-calibrated uncertainty estimates. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 6, 207–217 (2017).

Xue, D. et al. Accelerated search for materials with targeted properties by adaptive design. Nat. Commun. 7, 11241 (2016).

Häse, F., Roch, L. M. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Next-generation experimentation with self-driving laboratories. Trends Chem. 1, 282–291 (2019).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777(ACM, 2017).

Hensman, J., Fusi, N. & Lawrence, N. D. Gaussian processes for big data. In Proc. Twenty-Ninth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence 282–290 (ACM, 2013).

Balandat, M. et al. Botorch: a framework for efficient Monte-Carlo Bayesian optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 33, 21524–21538 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This material is based on work supported by the Texas A&M University System National Laboratories Office of the Texas A&M University System and Los Alamos National Laboratory as part of the Joint Research Collaboration Program. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Los Alamos National Laboratory or The Texas A&M University System. The authors acknowledge the support from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) ARPA-E CHADWICK Program through Project DE‐AR0001988. JJ acknowledges support from the Los Alamos National Laboratory Laboratory (LANL) Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program under project number 20220815PRD4. LANL is operated by Triad National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy (Contract No. 89233218CNA000001). Original data were generated within the BIRDSHOT Center (https://birdshot.tamu.edu), supported by the Army Research Laboratory under Cooperative Agreement (CA) NumberW911NF-22-2-0106 (MM, DK, DA, VA and RA acknowledge partial support from this CA). NF acknowledges support from AFRL through a subcontract with ARCTOS, TOPS VI (165852-19F5830-19-02-C1). Calculations were carried out at Texas A&M High-Performance Research Computing (HPRC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. worked on the conceptualization, all model training, testing, and manuscript text. M.M., N.F., D.K., and V.A. worked on the encoder-decoder model training-testing, data collection, and manuscript writing. J.J., D.P., D.A., V.A., and R.A. worked on model conceptualizations, ideation, supervision, manuscript writing, and reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alvi, S.M.A.A., Mulukutla, M., Flores, N. et al. Accurate and uncertainty-aware multi-task prediction of HEA properties using prior-guided deep Gaussian processes. npj Comput Mater 11, 306 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01811-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01811-2

This article is cited by

-

Deep Gaussian process-based cost-aware batch Bayesian optimization for complex materials design campaigns

npj Computational Materials (2026)