Abstract

The accurate description of in-gap states of point defects in semiconductors with significant multideterminant character presents a long-standing challenge for density functional theory (DFT) methods. In this study, we devise an ab initio methodology based on wavefunction theory (WFT) as a competing alternative approach. Specifically, we apply perturbation theory (NEVPT2) on top of a defect-localized many-body wavefunction (CASSCF). This quantum chemistry methodology, exemplified for the NV− center in diamond, is not only used for the calculation of energies and properties, but also for state-specific geometry optimization. By relaxing cluster models of increasing size and investigating convergence behavior, we accurately computed (i) the energy levels of NV− electronic states involved in the polarization cycle, (ii) the effect of Jahn-Teller distortion on measurable properties, (iii) the fine structure of ground and excited states, and (iv) the pressure dependence of zero-phonon lines. In addition, we predict hitherto uncharacterized high-lying excited states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their unique magneto-optical properties, point-like defects in crystals that act as individual color centers have become famous with the advance of quantum technologies. In the last decade, such solid-state color centers have been applied as high-resolution atomic-scale sensors1,2 thanks to their sensitivity to external electromagnetic fields, strain, and temperature. Furthermore, a large variety of single-photon emitters3,4,5 have been revealed in defected wide-bandgap semiconductors by now, which is an integral component in quantum computation6 and quantum communication7. Moreover, paramagnetic defects that enable spin-selective decay pathways could be used to create quantum bits8,9, which can be controlled using the optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) technique10.

From a theoretical point of view, point defects hosted in wide-bandgap semiconductors behave like atoms featuring localized states in a screening medium of bulk electrons. Spin-qubit applications relying on ODMR processes necessitate a complete understanding of the magneto-optical properties of the defect centers, where strongly correlated singlet many-body states can play a vital role11. Therefore, the proper models of these color centers require simultaneous high-level treatment of both static and dynamic correlation effects corresponding to the defect and the embedding solid, respectively12,13,14,15.

In the first place, numerical exploration of crystalline structures with point defects5 is typically performed using methods based on density functional theory (DFT)16. This approach enables the computation of many relevant properties of color centers, such as formation energies, charge transition levels, spin states, hyperfine tensors, zero-phonon lines (ZPLs), and photoluminescence spectra, albeit with varying accuracy, as reviewed in refs. 5,11,17,18. However, widely applied DFT is an inherently single-determinant method for ground state calculations, and it has limitations in describing states of strongly multideterminantal nature (also referred to as “multireference” or “multiconfigurational” character in the literature)19,20. Thus, despite the tremendous theoretical progress in recent decades in studying correlated electronic states with DFT21, the quantitative description of solid-state color centers still poses challenges22,23.

To further improve the model of spin-active defects, there is a great need for the development of a universally applicable wavefunction theory (WFT)-based protocol that can accurately handle multiconfigurational problems. In fact, the defect community has already begun exploring post-DFT and post-Hartree–Fock methods for this purpose. Without attempting to provide an exhaustive list, we mention several common methods, including time-dependent DFT24,25,26,27, variational DFT28, and GW approximations29,30 as post-DFT approaches, as well as complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF)31,32, multireference configuration interaction31, Monte Carlo configuration interaction (MCCI, FCIQMC)33,34, density matrix renormalization group35, and equation of motion coupled cluster theory36 as wavefunction-based so-called post-HF protocols. In addition, various embedding schemes have also been suggested, including configuration interaction - constrained random phase approximation (CI-cRPA)12,13,15,37, density matrix embedding theory (DMET)34,38, and quantum defect embedding theory (QDET) based on Green’s function39. These methods have mainly been benchmarked on the negatively charged nitrogen vacancy (NV−) center in diamond, which is the most relevant and extensively studied optically active spin defect to date11. The NV center in diamond comprises a substitutional nitrogen atom paired with an adjacent vacancy. In its negative charge state, it manifests a triplet ground state characterized by C3v point group symmetry11. While the distinct models concluded a largely consistent overall picture of the NV− vertical electronic structure, satisfactory quantitative agreement between theory and experiment could only be achieved by unconventional combinations of many-body Hamiltonian and DFT on supercells30,37,38 or by pure many-body WFT on small clusters32,40. Furthermore, the proper description of magneto-optical properties, taking into account geometry relaxation effects that are important for a detailed understanding of a defect center, has not been fully addressed within high-level WFT approaches.

In this work, we take a step forward in the direction of WFT modeling of qubits by presenting a novel computational strategy based entirely on quantum chemical wavefunction approaches readily available in commonly used codes. First, we highlight the critical importance of properly representing the host crystalline solid within finite cluster models passivated by hydrogen atoms. The appropriate model size is determined on the basis of careful convergence tests. By applying the CASSCF approach to the defect orbitals, we relax each electronic state of interest individually. The corresponding CASSCF electronic structure of the equilibrium geometry is improved by the energy correction resulting from the second-order n-electron valence state perturbation theory (NEVPT2), which incorporates the dynamic correlation effects of the surrounding lattice. In this paper, we demonstrate the performance of this methodology by a comprehensive modeling of the NV− center in diamond, aligning closely with the most established experimental observations in the research field.

Results

Active space of the NV− center

The proper choice of the active space for the CASSCF method is not always straightforward in computational chemistry41. Nevertheless, point defects in crystals typically yield a few localized defect orbitals, which define a chemically intuitive CAS. Note that these defect-localized MOs lie inside and/or in the close vicinity of a large bandgap, fundamentally shaping the low-energy excitations. In the case of the NV center in diamond22, four relevant defect orbitals can be identified at the single-determinant (Hartree–Fock) level, specifically those that originate from the dangling bonds of the three carbon atoms and the nitrogen atom adjacent to the vacancy (Fig. 1, left). Specifically, a1 is a bonding orbital shared between the three carbon and nitrogen atoms, while \({a}_{1}^{* }\) is its anti-bonding pair. The degenerate highest-lying orbitals of ex and ey, which are responsible for the spin-density distribution in the ground triplet state of NV−, are centered exclusively on the carbon atoms. (For more details on orbital characteristics, consult Supplementary Note 2.)

a Energy order and shape of NV− defect orbitals. In the schematic energy plot, the valence and conduction bands of diamond are visualized in blue. In the orbital plots, for the sake of visibility, only atoms of the innermost shell around the vacancy are shown. Carbon and nitrogen atoms are distinguished by color, gray and blue, respectively. The vacancy site is highlighted in black. b Summary of defect orbital configurations used for the expansion of the CASSCF(6e,4o) many-body states. Configurations are tabulated corresponding to their C3v symmetry representation and spin. Within a given block, they are also labeled according to energy.

The aforementioned orbitals are altogether occupied by six electrons (accounting for one unpaired electron for each C atom, a lone electron pair for N and the local negative charge), which implies a CASSCF(6e,4o) procedure. The conceivable 6 triplet and 10 singlet electron configurations, determined through group theoretical considerations42, are presented in the lower part of Fig. 1 along with their nomenclature used in this work.

Although the spin-polarization loop of NV− is known43 to proceed through the six lowest-lying electronic states of (1)3A2, (1)3Ex, (1)3Ey, (1)1Ex, (1)1Ey, and (1)1A1, higher-lying states are also worth studying, as they possess significant effects on observables through state mixing. We emphasize here that the degree of state mixing, i.e., the multireference character, cannot be quantitatively predicted by group theory. Our many-body WFT-based protocol takes the multireference character into account by construction. The many-body eigenstates, which arise as a linear combination of group-theory states in a CASSCF calculation, will be indicated by an overline in the following. For example, \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) denotes a CASSCF wavefunction which contains the pure (1)1A1 as a dominant component, but also other Slater determinants shown in Fig. 1.

The CASSCF approach is suitable for studying not only the ground state, but also the many-body excitations, as multiple solutions of the active-space FCI problem (referred to as “roots” in CASSCF terminology) can be requested. The orbitals are optimized for either an ensemble of target electronic states in a state-averaged manner (SA-CASSCF) or for one selected state (root) in a state-specific manner (SS-CASSCF).

In this work, both SS- and SA-CASSCF calculations were performed. For equilibrium geometries, which are peculiar to one well-defined electronic state, we applied the state-specific CASSCF approach to describe the state of interest as accurately as possible. On the other hand, for single-point calculations that address quantities involving multiple electronic states (such as excitation energies or transition matrix elements), a compromise must be found among the orthogonal roots during the orbital optimization process, which can be achieved by state-averaging. In the latter case, all studied electronic states were involved with equal weights in all calculations, in order to directly compare the resulting CASSCF-NEVPT2 energies.

For the SA-CASSCF procedure, we requested five triplet and eight singlet roots. Even though the maximal number of eigenstates is 6 triplets and 10 singlets, the convergence behavior of this setup (with respect to model size) is not completely satisfactory. This can presumably be traced back to the intensive mixing of the highest-lying states (with energy comparable to the diamond bandgap of 5.5 eV) with valence-band and conduction-band orbitals. By discarding them from the CAS construction, the remaining 5+8 roots provide a convergent in-gap spectrum. We also note that requesting a high number of roots (in contrast to the previously applied 3+3 setup40) also guarantees the stability of the active space against geometry distortions.

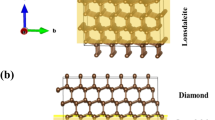

Cluster model of the color center

In our molecular investigation, we employ quantum chemical models to simulate the NV center embedded within nanodiamonds terminated with hydrogen at the surface. By progressively scaling up the cluster size, our objective is to accurately replicate the essential characteristics of the defected crystal. Large-scale bulk calculations, e.g., ref. 44, indicate clearly that the defect center perturbs the perfect diamond crystal structure only in its close vicinity. Thus, to reflect the observed stiffness of the surrounding solid in our cluster models, we optimized atomic positions only near the vacancy, while enforcing the perfect diamond structure in the outer shells of the cluster. In the following, we discuss this scheme, depicted in Fig. 2, in more detail. It is to be noted here that the N-V axis of the models is aligned with the magnetic axis.

In the diagram, the steps related to geometry construction/relaxation are colored brown, the active space selection, the CASSCF-NEVPT2 and CASSCF-QDPT calculations are marked in distinct shades of blue, while the final results are in green. In the structures, C, N, and H atoms are denoted by gray, blue, and white, respectively. The vacancy site is highlighted in black. Recall that in MODEL-n, the inner n + 2 coordination spheres around the vacancy were selected (as visualized for n = 1 in the plot), carbons of shell n + 2 were replaced by hydrogens to terminate the bonds as discussed in the main text. In the constrained geometry optimization, only the inner n coordination spheres were relaxed while the position of the carbons in shell n + 1 and the terminal hydrogens in shell n + 2 were kept fixed. MODEL-4, which is already large enough to provide a convergent model for the NV center, is highlighted in red.

Initially, a sizeable pristine diamond with a cubic crystal structure was formed with C–C bond distances, corresponding to the experimentally measured value of 1.54 Å. In the supercell, we created an NV center by removing a carbon atom and replacing one of its adjacent carbons with a nitrogen atom. Surrounding carbon atoms were divided into “shells” according to their position relative to the vacancy: atoms at n bond distance were assigned to the nth shell.

In our most compact defected cluster model, denoted as MODEL-1, we consider a three-shelled diamond structure, among which the outermost third shell of carbons is replaced by hydrogens to saturate all carbon valencies. Motivated by hybrid theories45 and by preserving the diamond structure, we opt to adjust the length of these C–H capping bonds to the conventional value of 1.09 Å. During constrained geometry optimization, the positions of the covering hydrogens and the outer (second) carbon shell were kept fixed, and we only allowed the relaxation of the inner atoms of the cluster. The general MODEL-n can be constructed analogously: only the innermost n shells around the vacancy were optimized by constraining the position of the carbon atoms of shell n + 1 and the terminating hydrogens of shell n + 2. In this work, we studied n = 1–4 cases, which correspond to C15H36N−, C39H60N−, C81H108N−, and C145H148N− clusters.

Constraining the position of the outer atoms gives the opportunity to perform WFT-level geometry optimization for all states of interest because of the relatively limited number of atoms to be relaxed. While the accurate modeling of transition energies requires the comprehensive treatment of correlation effects, the state-specific geometry optimization, which involves bond-stretching processes, can be readily performed by capturing merely the static correlations. Therefore, we applied the CASSCF approach for the constrained relaxation of the cluster models. These calculations were feasible in practice since in MODEL-1, 2, 3, and 4, one only has to optimize the position of 4, 16, 40, and 82 atoms, respectively.

Convergence analysis of the cluster model

A sufficiently accurate description of the NV− center by CASSCF-NEVPT2 is only expected if convergence is reached with respect to the model size. Apart from this, the finite number of Gaussian basis functions and the limited number of active orbitals also affect the CASSCF-NEVPT2 results, the magnitude of which must be investigated. Thus, we ran test calculations to confirm that our choice of cc-pVDZ basis set, MODEL-4 size, and 4 active orbitals (occupied by six electrons) reasonably approaches the limits of the CASSCF-NEVPT2 level. Numerical data for this analysis can be found in Supplementary Note 3, the results are also visualized in Fig. 3.

Energies of the \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\), \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\), and \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) states obtained for different choices of active space and basis set are visualized in (a–c), respectively, based on data from Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The CASSCF-level and the NEVPT2 corrected results for the (6e,4o) active space are presented in blue and red, respectively. The symbol and the hue vary with the choice of basis set (cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ, as well as CBS extrapolation based on cc-pV{D,T}Z data); the colored lines serve as a guide to the eye. The results for the (12e,7o) and (10e,6o) alternative active spaces of MODEL-3, discussed in Supplementary Note 3, are in green and orange, respectively. (The color code is the same for all subplots.) Shaded areas demonstrate a 0.1 eV energy tolerance around CASSCF(6,4)-based MODEL-4 results estimated at the CBS limit. Vertical black dashed lines indicate the position of MODEL-1, 2, 3, and 4 in the inverse system size scale.

We began our investigations in this direction by observing the model size dependence of vertical excited-state energy levels at the cc-pVDZ basis set. When increasing the size from MODEL-1 to MODEL-2, both the CASSCF energies and the NEVPT2 corrections show considerable alterations, which can even exceed 0.5 eV at the top of the energy spectrum. In the next step, when switching to MODEL-3, the CASSCF energies remain practically unchanged (within 0.1 eV relative to MODEL-2 results for all states), but the dynamic correlation at the NEVPT2 level has a significant effect, exceeding 0.5 eV for the highest energy states. (In general, the smaller models tend to overestimate the energy levels relative to the ground state.) Finally, when increasing the size from MODEL-3 to MODEL-4, both CASSCF and NEVPT2 show signs of convergence, as MODEL-4 reproduces the MODEL-3 energy levels within 0.05 eV for all electronic states (with a sole exception of a high-lying singlet). We note that in line with these observations on the convergence of energies, we also found that the defect orbitals have marginal weight at the artifact terminating hydrogens for MODEL-3 and 4, contrary to the smaller cluster models (see Supplementary Note 2).

Next, we performed a detailed analysis on basis dependence (see Supplementary Note 3), studying cc-pVnZ basis sets46 with n = D, T, Q, 5, and 6 cardinal numbers. We found a systematic overestimation of excitation energies arising from the basis set truncation, which, however, continuously decreases with increasing cluster model size. Specifically, cc-pVDZ practically recovers the basis set limit (determined by extrapolation to complete basis set (CBS)47,48) starting from MODEL-3: the discrepancy is below 0.1 eV for the lower-lying (<3 eV) excited states. Therefore, the choice of the moderate cc-pVDZ basis set is already reasonable, given that the convergence of energies and properties with respect to model size can be obtained.

Altogether, the convergence analysis with respect to model size and basis set size indicates that the CASSCF-NEVPT2 results, presented for MODEL-4 and cc-pVDZ basis, are expected to contain negligible errors that stem from finite-size effects.

For completeness, we also provide here the convergence properties of other parameters of interest (geometry relaxation, Jahn–Teller behavior, fine structure—see the corresponding subsections of “Results” for details). The largest difference between MODEL-3 and MODEL-4 results—which defines the error margin deriving from finite model and basis size—was found to be 0.015 Å for bond distances in equilibrium geometries (see Supplementary Notes 4 and 5), 2 meV for Jahn–Teller stabilization energies and barriers (Supplementary Table 8), and 0.03–0.01 GHz for zero-field spitting parameters (D tensor of ground triplet state, Des and Δ tensors of the first excited state; see Supplementary Table 9). The only quantities of significant uncertainty were the spin-orbit coupling parameters (λ⊥, pλz) with ~1–2 GHz of alteration between MODEL-3 and MODEL-4, which slow convergence trend in line with previous findings49.

Finally, we examined the effects of active space extension beyond the commonly applied four-orbital CAS model of the NV− defect. Although state-averaged active space selection based on first-order perturbation theory (ASS1ST)50 did not reveal clear indications of the need for extra orbitals, previous studies found that augmenting the common CAS either with valence-band51 or with conduction-band orbitals32 might improve the CAS-level theory. Thus, we also ran test calculations on particular extended active spaces (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the detailed description of the added orbitals). Our results indicate that the WFT energy spectrum of our models (including dynamic correlation corrections) is not significantly altered by the extra orbitals beyond the aforementioned four. In addition, we even observed the error cancellation effects, i.e., a larger active space increases, while a larger basis set decreases the gaps. We emphasize, however, that both errors are in the order of magnitude of 0.1 eV, which corresponds to the expected error bar of CASSCF-NEVPT252. Other key defect properties, such as spin-orbit and spin-spin couplings, also turned out to be rather robust to the choice of active space (≈25% relative deviation in average; see Supplementary Table 3), even though current NEVPT2 implementations only correct energies, and other properties are obtained only on the CASSCF level. In order to decrease the uncertainty of matrix elements and to provide a genuinely consistent model of the electronic structure, the implementation of NEVPT2-level wavefunction evaluation is highly desired in the future.

Low-lying vertical electronic excitations of the spin-polarization loop

The CASSCF-NEVPT2 level vertical spectrum, obtained at the ground-state geometry (i.e., \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) for triplets, \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) for singlets), is visualized in Fig. 4. We note that the initial relaxation to ground-state geometries was performed using C3v symmetry constraints.

In the plot, computational results of MODEL-4 are presented at SA(5+8)-CASSCF(6e,4o)-NEVPT2/cc-pVDZ level of theory at the geometry of the ground state (\({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) for triplets and singlets, respectively). Red arrows indicate experimentally characterized transitions. Red numbers by their side are the calculated vertical energy differences, while in parentheses are the experimental ones; the starred values are adiabatic. Black frames show the composition of electronic states, expressed in the basis of pure (group-theory) configurations presented in Fig. 1. Determinants with weights over 1% in the CASSCF wavefunction are provided, and the most simple wavefunction representations are shown, taking into account that a1 and \({a}_{1}^{* }\) molecular orbitals can be arbitrarily combined at C3v symmetry.

Firstly, we examine the lowest-lying states \(\left({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\right.\), \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\), \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) and \(\left.{(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\right)\) which are known to give rise to the ODMR signal of NV−. The top of the spectrum will be discussed in the next section.

We summarize the composition of the obtained CASSCF eigenstates, indicated by overlined capital letters, in the basis of group-theory configurations—see black frames in Fig. 4. The low-lying triplet states, denoted as \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\), \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\), are clearly of single reference, which means that they can be effectively described by a single electron configuration. However, the singlet states arise as a mixture of configurations of different electron excitations, which cannot be treated by conventional single-reference DFT methods. In particular, the \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) CASSCF eigenstate contains not only the dominant (1)1A1 configuration (77%) but also the (2)1A1 state with an empty \({a}_{1}^{* }\) orbital (23%). Furthermore, the \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) CASSCF eigenstates admix the (2)1E configurations, which represent \({a}_{1}^{* }\to e\) excitations, with a weight of 18% to the pure group-theoretic states (1)1E (82%).

Now, we turn our focus to the discussion of the vertical excitation energies shown in Fig. 4. Analyzing the computational data, we observed that the application of the NEVPT2 correction on top of the CASSCF theory had a large impact by reducing the raw CASSCF gaps by up to 1.5 eV; see Supplementary Table 1 for details. Overall, the resulting CASSCF-NEVPT2 energy spectrum for MODEL-4 is in fair agreement with the experimentally observed vertical transition energies, which can be estimated based on the position of the highest peak in the phonon sideband of the absorption spectra. Specifically, we predict 2.18 and 1.04 eV for the lowest vertical triplet and singlet optical gaps (calculated at the C3v symmetrical geometries of \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) using cc-pVDZ basis, respectively). In order to estimate the energies in the CBS limit, we extrapolated energies as discussed in Supplementary Table 2, which gave slightly lower 2.11 and 0.96 eV gaps, respectively. Our theoretical results reasonably reproduce the observed peak positions53,54 of 2.18 eV for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\to {(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) and 1.26 eV for \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\to {(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\), given that the dynamic correlation was treated at a perturbative level. In addition, since relaxation effects, which are discussed in detail in the corresponding section below, are expected to be relatively low in the crystal, the vertical gaps already closely approach the optical ZPLs of 1.95 and 1.19 eV, respectively.

As structural relaxation was often neglected in previous theoretical studies on the energy spectrum of NV−, it is interesting to compare our vertical energy values of the lowest-energy states with the results of the literature summarized in Table 1. Herein, we also provide the singlet energy levels \(\left({(1)}^{1}\bar{E},\,{(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\right)\) at ground state triplet geometry to be consistent with previous reports and to gain insight into the relative position of singlet and triplet sectors.

In previous works, the gap between \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) and \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) was obtained with reasonable accuracy even by pure DFT, as only single-reference electronic states are involved. For example, energy differences of 1.90–1.91 eV were calculated using the BP86 and PZ81 functionals, applied to a cluster model and a supercell, respectively33,55 while supercell HSE06 calculation resulted in 2.21 eV56. Post-DFT methods, e.g., CI-cRPA: 2.02 eV12, beyond-RPA: 2.00 eV37, GW: 2.1–2.3 eV29,30, approach the experimental energy difference better, albeit the deviation from pure DFT is rather marginal. Among wavefunction-based results, the CASSCF results with an extended active space (six electrons on six orbitals, i.e., two local virtual orbitals added to (6e,4o)) are particularly noteworthy: \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) energy levels of 2.1–2.3 eV were obtained without dynamic correlation treatment, depending on the way of state-averaging and the cluster size (34–86 heavy atoms)32,40. CASPT2 on top of the latter CASSCF(6e,6o) wavefunctions resulted in a gap of 2.22 eV32,40. Recently developed embedding methods, such as QDET (ΔE = 2.15 eV39) and DMET using NEVPT2 (NEVPT2-DMET; ΔE = 2.31 eV38), also provided similar values. Altogether, our CASSCF-NEVPT2 result of 2.18 eV is consistent with multiple versatile methodologies.

In contrast to the triplet gap, the energy levels of the singlet states show remarkable method dependence. For example, QDET39 and GW+BSE29 provide outstandingly low energies for \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\), which results in underestimated singlet gaps of 0.81 and 0.59 eV, respectively. On the other hand, some other approaches—such as DFT-BP86 and MCCI-based calculation on small cluster33—tend to place \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) over \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\), which contradicts the experimentally observed facile triplet-to-singlet intersystem crossing. Importantly, our CASSCF-NEVPT2 methodology does not produce any of the latter erroneous results and gives a \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) energy level of 1.60 eV (relative to \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) at the geometry of the latter), in reasonable agreement with closely related methods (CASPT2: 1.57 eV40, NEVPT2-DMET: 1.52 eV38). Although certain methods reproduce the experimental gap of 1.26 eV more closely (such as beyond-RPA37 with 1.20 eV, SA-CASSCF(6e,6o)40 with 1.30 eV, and variational DFT-r2SCAN28 with 1.18 eV), the CASSCF-NEVPT2 energy difference between singlets still has a tolerable error.

Vertical electronic excitations beyond the polarization cycle

In the following, we discuss the in-gap states above the polarization cycle of higher excitation energy (>2.5 eV), which were detected recently for the first time57. The energy and CASSCF wavefunction composition of the excitations are collected in Fig. 4, while the underlying basis configurations are given in Fig. 1.

Among the additional high-energy defect-localized states, \({(2)}^{1}\bar{E}\) and \({(2)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) contain only electron excitations of \({a}_{1}^{* }\to e\) and leave the nitrogen-localized lower a1 orbital doubly occupied, similarly to the states of the polarization cycle. In \({(2)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(3)}^{1}\bar{E}\), on the other hand, a hole is formed on the nitrogen-centered a1 orbital. Clearly, the previous conclusion on the single-reference character of triplets and multireference character of singlets remains: \({(2)}^{1}\bar{E},{(3)}^{1}\bar{E}\) and \({(2)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) carry the Slater determinants of the lowest-lying singlet state, although the degree of mixing is moderate (8–13%).

Based on the computed energy levels of Fig. 4, we can identify the transitions that were observed in recent transient absorption spectroscopy experiments57. Specifically, the measured absorption ZPL peak excited at 2.38 eV from \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) is closely matched by the 2.20 eV excitation energy of the \({(2)}^{3}\bar{E}\) state. Furthermore, the three ZPL excitations from \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) observed at 1.75, 2.79, and 2.85 eV might correspond to our predicted \({(2)}^{1}\bar{E}\), \({(3)}^{1}\bar{E}\), and \({(2)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) states of energy 1.70, 2.23, and 2.74 eV, respectively, albeit the difference between the intermediate values (observed: 2.79 eV, calculated: 2.23 eV) is suspiciously large. A follow-up investigation on the spectra of extended active spaces, which could be the subject of future work, might reveal an alternative assignment.

Note that our vertical energies, determined at 3\({\bar{A}}_{2}\) geometry without state-specific relaxation, in strict terms, are not comparable to the aforementioned ZPL measurements. Nevertheless, the expected low relaxation effects of the solid-state environment and the lack of any additional localized near-band-gap orbitals apart from ex, ey, \({a}_{1}^{* }\) and a1 strongly suggest that our assignment of the absorption peaks is valid. It should also be noted that in the case of the higher-energy states, the deviation of CASSCF-NEVPT2 excitation energies from the experimental ZPLs might partially derive from error accumulation: that is, CASSCF excited states are computed as orthogonal vectors to all lower states, the numerical uncertainties of which might accumulate to a higher and higher extent with the increasing number of the required roots.

Relaxed electronic spectrum

To determine the adiabatic excitation energies that correspond to the experimental ZPLs, we also studied the geometry relaxation effects at the CASSCF level for the low-lying six electronic states of the spin-polarization cycle. Correspondingly, we refined the NEVPT2-corrected vertical energy of each excitation of interest by the reorganization energy, the result of which is shown in Fig. 5. Recall, in practice, the atomic configurations of all electronic states were optimized at SS-CASSCF(6e,4o)/cc-pVDZ level of theory, and SA-CASSCF-NEVPT2 single-point calculations were performed on the resulting equilibrium geometries.

In the plot, the computational results of MODEL-4 are presented at CASSCF(6e,4o)-NEVPT2/cc-pVDZ level of theory. Vertical red arrows indicate experimentally characterized optical transitions54,58, where the computational data can be directly compared to measurements. Horizontal red arrow denotes singlet-triplet gaps, which were estimated experimentally based on population dynamics of excited states60. Red numbers are the calculated energy differences, while the numbers in parentheses are the experimental ones.

We note here that a complete analysis of geometry relaxation effects would also account for the state dependence of vibrational energy levels. Nevertheless, the frequency calculations required for this correction are expensive and are not expected to alter the results by more than a few meVs56. Davies and Hamer, for instance, deduced a zero-point energy (ZPE) value of 35 meV54, and the difference between the two ZPE values is expected to be even smaller. Therefore, the shift of energy levels related to vibrations will be ignored in the following.

The optimized geometry for each electronic state, characterized by the C–C distances adjacent to the vacancy, is summarized in Supplementary Table 5. Furthermore, a detailed description of the calculation of relative energy levels and their model size dependence is provided in Supplementary Note 4. Concerning the state-specific equilibrium geometries, we find that the states of A1 and A2 irreducible representations conserve the C3v symmetry even after the relaxation procedure. Nevertheless, the C–C distances adjacent to the vacancy depend on the electronic structure; in the \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) excited singlet state, the carbon atoms are ≈0.1 Å further from each other than in the \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) ground state.

For the \(\bar{E}\) states, we clearly observe the expected Jahn–Teller distortion, which lowers the symmetry to C1h. This splits the double degeneracies observed in the vertical energy spectrum and forms \({\bar{A}}^{\prime}\) and \({\bar{A}}^{\prime\prime}\) states of slightly different geometries and consequently energy levels (Fig. 5, black arrows). In the former case, one inner C–C distance elongates relative to the other two, but the system remains close to C3v symmetry, and only 0.02–0.03 Å deviations were observed. In the latter case, elongation occurs and the two longer C–C distances exceed the short C–C side by 0.09–0.14 Å. Importantly, the energy difference between the \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime} }\) and \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) states falls in the range of tens of meVs, which foreshadows that a dynamic Jahn–Teller effect might be present. A more sophisticated discussion of JT energy levels and dynamic JT behavior can be found in the next section.

Next, we evaluate the relative energy levels of the electronic states, which are now directly comparable to experimental ZPLs54,58. In the triplet spin sector (Fig. 5, left), the well-known characteristic ZPL of NV− (1.95 eV energy change corresponding to 637 nm emission) is reproduced as a 1.80 eV energy difference between \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\). As for the singlet states (Fig. 5, right), the optical transition belonging to the infrared emission of NV− (1.19 eV, 1042 nm) is also sufficiently modeled by CASSCF-NEVPT2, and a 1.02 eV energy gap is obtained after relaxation of the involved electronic states. To further analyze the relaxation effects, we also computed the characteristic spectroscopic parameters of the latter two optical transitions, and compared them to DFT-based results and measurements. These data are provided in Table 2.

Using our CASSCF-NEVPT2 methodology, Franck–Condon shifts (ΔEFC) can be calculated as the reorganization energy of the ground/excited state (for emission/absorption) relative to the geometry of the opposite electronic state, while the total Stokes shift can be predicted as the sum of the two ΔEFC values. Furthermore, after determining the mass-weighted displacement of coordinates (Q) between initial and final states, we can also calculate the energy of the effective phonon (hνeff) as

based on which the Huang-Rhys factor (S) and the Debye–Waller factor (wZPL) can be determined as

and

In the case of the \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\leftrightarrow {(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) transition, we found a Franck–Condon shift of 0.17 and 0.38 eV in the direction of emission and absorption, respectively (accounting for the JT minimum for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\)). This corresponds to a total Stokes shift of 0.55 eV. The results are in line with experiments (ΔEFC = 0.19 eV/0.24 eV; 0.45 eV Stokes shift54,59), albeit the absorption shift is overestimated by more than 0.1 eV. This can presumably be traced back to the slight deviation of CASSCF and CASSCF-NEVPT2 level equilibrium geometries, the latter of which is not yet available due to the prohibitively expensive numerical gradients. Nevertheless, if implemented in the future, a full CASSCF-NEVPT2 level relaxation will improve these results. (Another factor might be the ambiguous treatment of E ⊗ e type Jahn–Teller systems; for example, under C3v symmetry constraints for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\), we obtain ΔEFC = 0.33 eV for absorption.) Regarding the Huang-Rhys factors and the Debye–Waller factors, the computed values of S = 2.9–4.0 and wZPL = 1.8–5.4%, respectively (depending on the direction), also well reflect the experimental observations of phonon-sideband dominated spectra (S = 3.2–3.7; wZPL = 2.4–4.1%54,59).

In the singlet sector \(\left({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\leftrightarrow {(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\right)\), significantly lower Franck–Condon shifts of 0.00 eV (emission) and 0.16 eV (absorption) were found, where the latter value comes primarily from the Jahn–Teller distortion to C1h symmetry. (Related to this result, we note that the vertical energy of \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\)—given as 1.04 eV relative to \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) in Fig. 4—increases to 1.18 eV when calculated at the JT distorted geometry of \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\to A^{\prime\prime}\).) Again, a definite qualitative agreement to the experimental data (0.04 eV/0.07 eV53,58) was reached, with errors below 0.1 eV, which is presumably caused by the aforementioned geometry bias between levels of WFT. The spectrum of singlet optical transitions is dominated by the ZPL, as shown by both the calculations (S = 0–1.8, wZPL = 16–100%) and the experiments (S ≈ 1 and wZPL ≈ 50% for both directions53,58).

Comparing our HR factors and DW factors with previously reported DFT-based analyzes26 (see the corresponding column of Table 2), it can be said that the deviation of DFT and WFT from experiments is generally similar. For example, the mismatch in the number of emitted phonons is in the range of 0.5–1.5. The most noticeable difference is the above-mentioned overestimation of the relaxation effect by WFT (ΔEFC = 0.38 eV) in the absorption process among triplets, which does not appear in DFT calculations (ΔEFC = 0.19–0.26 eV, depending on the DFT method); nevertheless, this result is not surprising, as a well-parametrized density functional is expected to outperform NEVPT2 for single-reference systems, where the latter simplifies to MP2. However, we emphasize that DFT protocols often fail for multireference systems, in contrast to our generally applicable protocol. Besides, the error arising from dynamic correlation-free CASSCF-level optimization, found to be in the range of 0.1 eV in our calculations, does not possess a significant influence on the characterization of defect states.

Regarding the relative energy levels of the two different spin sectors, the estimated energy difference between \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) available in the literature varies in the range of 0.32–0.41 eV. The latter data were determined by fitting intersystem crossing rate equations to the observed population dynamics of NV− excited states. Based on these numbers and the ZPL of 1.19 eV between singlets, the energy level of \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) is estimated to be 0.35–0.44 eV above the ground state60. At the CASSCF-NEVPT2 level of theory, we obtain 0.26 eV for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\)-\({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\) and 0.52 eV for \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\)-\({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\), which slightly under- and overestimates, respectively, the two aforementioned ranges. Therefore, the discrepancy of our methodology (<0.08 eV deviation from the experimental predictions) is remarkably small.

Altogether, our CASSCF-NEVPT2 methodology accurately reproduced the relative energy levels of the common states of the polarization cycle. The absolute error of CASSCF-NEVPT2 results, compared to ZPL energies of experimentally observable optical transitions, was approximately 0.15 eV. Furthermore, the experimentally estimated singlet-triplet gaps are also reliably predicted by our calculations within 0.1 eV. The computed geometry shifts reasonably describe the relaxation effects, as confirmed by the comparison of characteristic Franck–Condon shifts (mean absolute error: 0.07 eV) and Huang-Rhys factors (mean absolute error: 1.0) to measurements. Thus, the assembled relaxed energy level diagram shown in Fig. 5 properly reflects the relative position of NV− electronic states.

Pressure dependence of ZPL

The NV center has potential in quantum metrology applications due to its sensitivity to external fields and surrounding conditions, e.g., temperature and pressure. In particular, the ZPL between the lowest triplets was shown to vary linearly with respect to hydrostatic pressure61,62. Here, we aimed to reproduce the experimental observations in order to demonstrate the general applicability of our proposed molecular modeling scheme. In order to simulate the effect of the hydrostatic stress in our cluster model, we repeated the geometry construction procedure discussed above (see Fig. 2) for various lattice constants, considering the numerical pressure-density63 and the trivial density-bond length relationships. In practice, we studied the \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) states of MODEL-3, whose geometry was initialized by rescaling the atomic coordinates corresponding to pressure, and it was optimized keeping the two outermost atomic shells frozen. Then, we calculated the ZPL at each pressure value studied as the CASSCF-NEVPT2 energy difference between the two triplet states, taking geometry relaxation into account.

The pressure-dependent ZPL data, visualized in Fig. 6, were calculated in the 0-50 GPa pressure range. Applying linear fitting to the numerical data, we obtain a 5.21 ± 0.55 meV/GPa gradient, which is in good agreement with the experimental findings61,62 of 5.5–5.75 meV/GPa. This result gives further evidence for the validity of the cluster-based modeling with constrained geometry optimization.

Jahn–Teller behavior of E states

When studying the Jahn–Teller distorted 3\(\bar{E}\) and 1\(\bar{E}\) states, it is of fundamental interest whether the system is trapped in a single potential energy valley corresponding to an energetically highly favorable \(A^{\prime\prime}\) or \({A}^{{\prime} }\) structure (static Jahn–Teller effect), or continuously oscillates among three spatially degenerate minima (dynamic Jahn–Teller effect). Namely, in the latter case, the system appears to have high (C3v) symmetry in experiments, even if the energetically most favorable geometry is distorted. In this section, the JT behavior of the low-energy \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) states will be discussed.

Static and dynamic Jahn–Teller systems can be distinguished by comparing the Jahn–Teller barrier (δJT) to the ZPE level of the two distortion-driving e vibrational modes (hνe). Here, δJT refers to the energy difference between the two C1h symmetrical configurations, i.e., \(A^{\prime\prime}\) and \(A^{\prime}\) (one of them appears as an energy minimum, while the other acts as a transition state in Jahn–Teller oscillation). The criterion for a static JT effect is δJT > hνe; in the opposite case, the energy of the vibration is large enough to form a dynamic JT system64. As visualized in Fig. 7, δJT can be calculated as the difference between \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) and \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime} }\) minimal energies.

The plots illustrate the vicinity of the minimum-energy crossing point (MECPs) between \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) states (a) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) states (b). The relative energy levels of \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime} }\), \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime\prime} }\) and MECP structures were calculated at SS-CASSCF(6e,4o)-NEVPT2 level. Jahn–Teller parameters (EJT, δJT) were obtained from energy differences, as shown. Parameter hνe was calculated as an effective phonon energy between \({\bar{A}}^{\prime}\) and \({\bar{A}}^{\prime\prime}\) minima, using a 50–50% weighing for the two degenerate \(\bar{E}\) states. In the structure plots, the carbon atoms neighboring the vacancy are presented, N-V axis is out of plane.

For further investigation, we searched for the minimum-energy crossing point (MECP) between \(\bar{E}\) states. This can be done by (i) locating the crossing point of \({\bar{A}^{{\prime\prime} }}\) and \({\bar{A}}^{{\prime} }\) surfaces along the reaction coordinate connecting the two JT distorted geometries (see Supplementary Note 5 for details), or (ii) by a state-average geometry optimization, setting the weight of both JT states to 50%. According to our experience, these two methods converge to practically identical nuclear configurations. The resulting MECP (geometry for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) is depicted in Fig. 7, see black frames) is the most stable geometry where the \({\bar{E}}_{x}\) and \({\bar{E}}_{y}\) are degenerate, which is only possible at C3v symmetry. As indicated in Fig. 7, the energy difference between MECP and the bottom of the lowest-energy valley corresponds to the Jahn–Teller stabilization energy (EJT), whose role in the modeling is discussed below.

We find that the order of \({\bar{A}}^{\prime\prime}\) and \({\bar{A}}^{\prime}\) energy levels at the CASSCF-NEVPT2 level depend on the electronic state: \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) favor the \(A^{\prime}\) and the A″ irreducible representation, respectively. We note that this result is in line with previous DFT-based investigations on the Jahn–Teller surface shapes40,49. As for the numerical data, we obtain δJT = 14 and 43 meV for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\), respectively (see detailed discussion and convergence behavior with respect to model size in Supplementary Note 5). To determine the nature of the JT effect, these values should be compared to the energy of the effective e phonon65 that connects \({\bar{A}^{\prime}}\) and \(\bar{A}^{\prime\prime}\) minima. By fitting the JT phonon energy to the obtained potential energy surfaces (see Supplementary Note 5 for the mathematical derivation), hνe = 77 meV and 63 meV were found for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\), respectively. Therefore, both \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\) will be considered as dynamic JT systems in the following.

In dynamic JT, the strength of the vibronic coupling, defined as the proportion of the Jahn–Teller stabilization energy (EJT) and the Jahn–Teller phonon energy (hνe), characterizes the behavior of the system; it determines how the observed properties, such as the fine structure (vide infra), are altered compared to the Born-Oppenheimer picture. Here, EJT refers to the energy that is released upon symmetry breaking (C3v → C1h). It is equal to the energy level of MECP relative to the JT minimum. At CASSCF-NEVPT2 level, we found EJT = 51 and 62 meV for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) and \({(1)}^{1}\bar{E}\), respectively. Putting these data together, both systems turn out to be strongly coupled, as hνe and EJT are commensurable.

Spin-orbit and spin-spin couplings, fine structure of triplet states

By introducing spin-orbit coupled (SOC) and SSC to CASSCF(6e,4o) eigenstates in the framework of quasi-degenerate perturbation theory (QDPT), we determined the fine structure of the spin-triplet states. The data presented for the \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) and \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) states were calculated for the equilibrium geometry of the ground state and for the corresponding MECP geometry, respectively, at the SA(5+8)-CASSCF-NEVPT2 level. By this post-process treatment of the SOC and SSC couplings, we extracted the relevant parameters (D, λz, Des, Δ) from the energy differences between QDPT eigenstates as summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 8. For more details and model-size-dependent numerical data, consult Supplementary Note 6.

The D tensor of the \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) state was obtained as the energy difference between the QDPT ground state (corresponding to \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\), mS = 0) and the two lowest excited states \(\left({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2},{m}_{S}\pm 1\right)\). As shown in the upper row of Table 3, our theoretical prediction of D = 2.86 GHz perfectly reproduces the experimental data of 2.88 GHz66. Thus, the CASSCF theory turned out to be comparable to the spin-decontaminated DFT, which gives D = 2.72 GHz67. We note that the SSC effects completely determine the zero-field splitting (ZFS) of the \({(1)}^{3}{\bar{A}}_{2}\) ground state, as SOC does not lift the degeneracy of states with zero angular momentum42.

Next, we investigated the fine structure of the \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) electronic states. In the C3v symmetry of the MECP geometry, two orbitally degenerate states are split into six spin sublevels by SOC and SSC, the relative energy levels of which can be characterized by three parameters: λz, Des, and Δ, see Fig. 8 for a visual explanation. However, modeling of this splitting is more complicated than simply extracting the raw QDPT energies, as the dynamic Jahn–Teller instability of the \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) states attenuates the bare λz and Δ splitting parameters by the so-called Ham reduction factors68.

The damping of λz by the dynamic JT effect, denoted as p reduction factor, simplifies to p = 0 if EJT ≫ hνe holds, while it can be expressed as \(p={e}^{-4{E}_{{\rm{JT}}}/h{\nu }_{e}}\) in the opposite extreme case (EJT ≪ hνe). If the JT stabilization energy and the JT phonon energy are comparable, which is the case for \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) according to our calculations, the empirical formula of

can be used. We note that this formula of Ham assumes pure linear electron-phonon coupling, i.e., Mexican hat potential energy surface with δJT = 0, therefore, we substituted \({E}_{{\rm{JT}}}-\frac{1}{2}{\delta }_{{\rm{JT}}}\) to the numerator of the exponential expression. The damping factor for Δ, dubbed as q reduction factor, derives from p as

regardless of the range of EJT/hνe. In our calculations, the corresponding multiplicators were found to be p = 0.24 and q = 0.62.

In order to validate the above approximation of Ham factors, we also solved the E ⊗ e dynamic Jahn–Teller Hamiltonian explicitly. The obtained Jahn–Teller parameters (EJT, δJT, hνe) determine the full adiabatic potential energy surface (APES), based on which we computed the electron-phonon coupling coefficients and derived the reduction factors. The mathematical formalism is described in detail in ref. 49. In this way, we calculate p = 0.25 and q = 0.63, which negligibly deviates from the above estimation based on Ham’s formulae.

Having the proper prefactors at hand, the damped SOC elements pλz and qΔ can readily be compared to the available experimental data69 as summarized in Table 3. Although raw λz is more than five times larger than the experimental value, the Ham-reduced result (pλz = 6.5 GHz) is in reasonable agreement with the measurements (5.3 GHz). Furthermore, our result is also qualitatively similar to the previously reported DFT-based analysis of this spin-orbit coupling49, where λz = 15.8 GHz, p = 0.3 and pλz = 4.8 GHz was found, albeit CASSCF-NEVPT2 gives slightly higher coupling but lower p factor, which indicates error cancellation to some extent. Importantly, the ab initio reproduction of this parameter is especially challenging due to the exponentialized \(\frac{{E}_{{\rm{JT}}}}{h{\nu }_{e}}\) term in the reduction factor, which easily introduces considerable errors. (Similarly, the explicit computation by using the dynamic JT Hamiltonian is also sensitive to the JT surface parameters.) This characteristic of the ZFS calculations is also manifested in the slow convergence of pλz with respect to the size of the model (Supplementary Table 9), compared to the smooth convergence of all other energies and properties presented in this study. Namely, we found more than 1 GHz difference between the respective values computed for MODEL-3 and MODEL-4. On the other hand, both λz and the JT parameters required for p (such as EJT, δJT, hνe) show definite signs of convergence. Therefore, we attribute the apparent model size effect to the unfortunate propagation of small numerical uncertainties and consider the value of 6.5 GHz as the converged spin-orbit coupling parameter.

As for the spin-spin coupling-related ZFS parameters, the experimental Δ splitting of 1.55 GHz is exactly reproduced by our calculations after taking into account the q reduction factor. The Des tensor, which is not affected by the DJT effect, was calculated to be 1.58 GHz, slightly overestimating the experimental value of 1.42 GHz69.

In the case of \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\), another important SOC parameter to consider is its coupling to the singlet state of \({(1)}^{1}{\bar{A}}_{1}\). We analyzed the coupling parameter of the SOC+SSC level eigenstates of the \({(1)}^{3}\bar{E}\) manifold, which split to four sublevels as shown in Fig. 8. We found that only the A1 state has finite coupling in agreement with group theory considerations60. Namely, at first order, the matrix element of

determines the rate of the intersystem crossing step that gives rise to the ODMR signal of NV−. We note that the prefactor of \(1/\sqrt{2}\) was added for consistency with the conventional definition of λ⊥49,51,60. Our result is in agreement with the 6.75 GHz value reported by Ping et al.40 but lies significantly below 29.4 GHz reported by Galli et al.51. Thus, we hereby confirm that the previously observed low CASSCF-level SOC matrix elements40 are not the consequences of small cluster models; namely, our MODEL-4 containing 145 carbon atoms gives equal coupling. We further note that the λ⊥ matrix element—in contrast to λz—cannot be measured directly. Therefore, its “experimental” value of 21.1 GHz is a result of estimations made by connecting pλz and λ⊥ via the assumptions of p ≈ 0.349 and λz/λ⊥ ≈ 1.260,70, neither of which has unequivocal experimental evidence. Consequently, the accuracy of this experimental estimate is somewhat uncertain.

Concerning the deviations of the calculated parameters pλz and λ⊥ from the measured and/or DFT-level computed values, an important aspect of our modeling is to be noted. That is to say, the current level of theory does not capture the dynamic correlation effects, as the available NEVPT2 implementations only correct the CASSCF energies (but not the corresponding CASSCF wavefunctions). We expect that either the to-be-implemented NEVPT2 wavefunction correction or a systematic extension of the active space, treated by approximate CI solvers, would improve the quality of the predictions.

Discussion

In this theoretical study, our aim was to devise a wavefunction-only computational protocol that enables the complete characterization of future quantum bit candidates implemented by point defects in semiconductors. The proposed methodology was benchmarked on the NV− center in diamond, where we were able to reproduce all the available experimental data with a tolerable error margin.

Our molecular-cluster-based framework accounts for static electron correlation at the CASSCF level, placing the chemically relevant defect orbitals in the active space. The dynamic correlation of the environment was obtained at the NEVPT2 level of theory, which provides a perturbative correction. The cluster geometries were optimized at the CASSCF level of theory, considering the stiffness of the hosting crystal. We investigated the results for a set of cluster models of increasing size, up to 300 atoms, to confirm the convergence of our predictions.

We demonstrate that all parameters related to the excited state spectrum of the NV center can be obtained using a single WFT-based method and a freely available quantum chemistry code, without requiring post-processing or cross-method developments. The calculations are detailed and thoroughly discussed, including error margins, to encourage widespread adoption of the methodology presented in our work. Based on our demonstrative results, we believe that the presented methodology is broadly applicable to point defects with correlated excited states. We anticipate that it can be routinely applied with similar accuracy to color centers in wide-band-gap crystals.

Methods

Static correlation (CASSCF)

The CASSCF method71,72,73 captures the full range of correlation effects within a specific set ("active space”) of molecular orbitals. In the CASSCF approach, a two-step procedure (full configuration interaction (FCI) approach accompanied by the Hartree–Fock orbital optimization) is repeated until convergence is reached. Here, FCI is used to determine the many-body states for a given orbital set, and the Hartree–Fock method mixes orbitals to minimize the energy.

Thus, this method is capable of providing a practically exact solution in case all orbitals with non-negligible correlation effects are included in the active space. Unfortunately, owing to the exponential scaling of the approach with respect to the number of active orbitals, only a handful of orbitals (up to 20) can be set to active without further approximations. The remaining orbitals are kept frozen on the Hartree–Fock level during the solution of the configuration interaction problem, and only influence the correlation energy through some orbital mixing during the orbital optimization procedure.

Overall, the method provides a highly accurate description of the static correlation, i.e., the mixing of electronic states of different orbital occupation patterns, but it fails to assess the dynamic correlation effect of the inactive, doubly occupied, and virtual, unoccupied orbitals. The resulting CASSCF wavefunction is qualitatively correct and, hence, was used for geometry optimization and vibrational analysis. However, neglecting the dynamic correlation generally results in large errors in energy differences between different electronic states.

Dynamic correlation (NEVPT2)

If transitions between different electronic states are investigated, it is essential to take into account dynamic correlation on top of the CASSCF wavefunction74. Without this correction, the theory might not reproduce the excitation energies quantitatively75.

In the literature, various concepts have been developed to provide correction a posteriori to the CASSCF solution. Building on our previous work on point defects in hexagonal boron-nitride layers76,77, we employ the second-order n-electron valence state perturbation theory (NEVPT2)78,79,80. This method, a type of multireference perturbative approach, is an extension of the second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory81 to multireference problems. Owing to the construction of the zero-order Dyall Hamiltonian82 and to the choice of perturbers, the NEVPT2 can provide a size-consistent theory on top of the CASSCF reference that is free of intruder states and spin-contamination issues. Recent technical developments83,84,85 have allowed the routine treatment of molecular systems with thousands of perturbing orbitals86.

Fine structure and spin properties

The calculation of ZFS parameters requires SOC and spin-spin coupled (SSC) states and their energy levels. In computational quantum chemistry approaches, the SOC and SSC effects are typically introduced in a post-process manner. Here, their contribution is obtained on the basis of the CASSCF states within the framework of QDPT87. The QDPT treatment assembles a SOC+SSC matrix from the non-relativistic Born-Oppenheimer (BO) CASSCF states (\({\Psi }_{I}^{SM}\)) as

where the indices I/J, \(S/S^{\prime}\), and \(M/M^{\prime}\) refer to the number of the CASSCF root, its spin state, and spin sublevel, respectively. The diagonal electronic energy, \({E}_{I}^{S}\), is taken into account at the WFT level corrected for dynamic correlation, herein NEVPT2. In our study, the \(\langle {\Psi }_{I}^{SM}| {\hat{H}}_{{\rm{SOC}}}+{\hat{H}}_{{\rm{SSC}}}| {\Psi }_{J}^{S^{\prime} M^{\prime}}\rangle\) matrix elements are calculated between the previously obtained CASSCF roots using the spin-orbit mean-field approximation88. The spin sublevel dependence, which does not appear explicitly in non-relativistic CASSCF wavefunctions, can be introduced by means of the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients, in accordance with the Wigner-Eckart theorem89.

The diagonalization of the QDPT matrix yields the coupled states as eigenvectors and the respective energy levels as eigenvalues, from which the ZFS parameters can be extracted as energy differences. Importantly, since CASSCF implementations work in the restricted open-shell formalism (that is, the orbitals of α and β spin channels are equal), the spin-contamination issues of ZFS calculations, commonly observed for DFT67, are avoided by construction.

Technical details

In this study, we applied the quantum chemical program package ORCA90 (version 5.0.3) for all computations. For the sake of reproducibility, typical ORCA input files can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

The geometries for the conceivable electronic states of NV− (see Fig. 1, bottom) were optimized at state-specific CASSCF(6e,4o)/cc-pVDZ level. In these calculations, we assumed C1h point group as it allows the Jahn–Teller distortion of \(\bar{E}\) states (\(\bar{A}\) states maintain the C3v symmetry, regardless of the symmetry constraints). Furthermore, both the Jahn–Teller barrier and the Jahn–Teller minimum can be located in a straightforward manner by selecting either \(A^{\prime}\) or \(A^{{\prime}{\prime}}\) or irreducible representation for the state-specific geometry optimization.

On the obtained equilibrium geometries, SA-CASSCF-NEVPT2 single-point calculations were performed, which provided the energies and properties described in the main text. Five triplet and eight singlet roots were included in the state-average treatment.

The CASSCF-NEVPT2 framework was tested on the cluster models using both the strongly contracted (SC) and the fully internally contracted (FIC) implementation of the ORCA suite91, as well as the domain-based local pair natural orbitals (DLPNO) based approximation of the latter85. Unfortunately, the computationally less demanding FIC and DLPNO-FIC methods yielded problematic negative eigenvalues for the Koopmans matrix in several cases, even for low-energy excited states. Hence, the results discussed in the main text were computed using the SC-NEVPT2 approach, as it shows numerical stability and robustness against intruder states.

To speed up calculations, we took advantage of the resolution of identity approximation (RI). The construction of Coulomb and exchange integrals was carried out using the RIJCOSX92 method with the def2/J93 auxiliary basis set. Furthermore, RI-approximated integrals appearing in orbital gradients and Hessians for CASSCF and NEVPT2 were calculated using the cc-pVDZ/C94 auxiliary basis set.

An overview of the computational demands is given in Supplementary Note 7.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Further numerical data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Aslam, N. et al. Quantum sensors for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 157–169 (2023).

Chunnilall, C. J., Degiovanni, I. P., Kück, S., Müller, I. & Sinclair, A. G. Metrology of single-photon sources and detectors: a review. Opt. Eng. 53, 081910 (2014).

Aharonovich, I., Englund, D. & Toth, M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nat. Photonics 10, 631–641 (2016).

Zhang, G., Cheng, Y., Chou, J.-P. & Gali, A. Material platforms for defect qubits and single-photon emitters. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 031308 (2020).

Aspuru-Guzik, A. & Walther, P. Photonic quantum simulators. Nat. Phys. 8, 285–291 (2012).

Lo, H.-K., Curty, M. & Tamaki, K. Secure quantum key distribution. Nat. Photonics 8, 595–604 (2014).

Ladd, T. D. et al. Quantum computers. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010).

Awschalom, D. D., Bassett, L. C., Dzurak, A. S., Hu, E. L. & Petta, J. R. Quantum spintronics: engineering and manipulating atom-like spins in semiconductors. Science 339, 1174–1179 (2013).

Suter, D. Optical detection of magnetic resonance. J. Magn. Reson 1, 115–139 (2020).

Gali, A. Ab initio theory of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Nanophotonics 8, 1907–1943 (2019).

Bockstedte, M., Schütz, F., Garratt, T., Ivády, V. & Gali, A. Ab initio description of highly correlated states in defects for realizing quantum bits. npj Quantum Mater. 3, 31 (2018).

Ma, H., Sheng, N., Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Quantum embedding theory for strongly correlated states in materials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 2116–2125 (2021).

Pfäffle, W., Antonov, D., Wrachtrup, J. & Bester, G. Screened configuration interaction method for open-shell excited states applied to nv centers. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104105 (2021).

Muechler, L. et al. Quantum embedding methods for correlated excited states of point defects: case studies and challenges. Phys. Rev. B 105, 235104 (2022).

Jones, R. O. Density functional theory: Its origins, rise to prominence, and future. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 897–923 (2015).

Freysoldt, C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 253–305 (2014).

Dreyer, C. E., Alkauskas, A., Lyons, J. L., Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. First-principles calculations of point defects for quantum technologies. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48, 1–26 (2018).

Cohen, A. J., Mori-Sánchez, P. & Yang, W. Challenges for density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 112, 289–320 (2012).

Verma, P. & Truhlar, D. G. Status and challenges of density functional theory. Trends Chem. 2, 302–318 (2020).

Makkar, P. & Ghosh, N. N. A review on the use of DFT for the prediction of the properties of nanomaterials. RSC Adv. 11, 27897–27924 (2021).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Gali, A. Recent advances in the ab initio theory of solid-state defect qubits. Nanophotonics 12, 359–397 (2023).

Raghavachari, K., Ricci, D. & Pacchioni, G. Optical properties of point defects in SiO2 from time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 825–831 (2002).

Gali, A. Time-dependent density functional study on the excitation spectrum of point defects in semiconductors. Phys. status solidi (b) 248, 1337–1346 (2011).

Jin, Y., Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Vibrationally resolved optical excitations of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 238 (2022).

Jin, Y., Yu, V. W.-z, Govoni, M., Xu, A. C. & Galli, G. Excited state properties of point defects in semiconductors and insulators investigated with time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 8689–8705 (2023).

Ivanov, A. V., Schmerwitz, Y. L. A., Levi, G. & Jónsson, H. Electronic excitations of the charged nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond obtained using time-independent variational density functional calculations. SciPost Phys. 15, 009 (2023).

Ma, Y., Rohlfing, M. & Gali, A. Excited states of the negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy color center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 81, 041204 (2010).

Choi, S., Jain, M. & Louie, S. G. Mechanism for optical initialization of spin in NV− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 86, 041202 (2012).

Zyubin, A. S., Mebel, A. M., Hayashi, M., Chang, H. C. & Lin, S. H. Quantum chemical modeling of photoadsorption properties of the nitrogen-vacancy point defect in diamond. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 119–131 (2009).

Bhandari, C., Wysocki, A. L., Economou, S. E., Dev, P. & Park, K. Multiconfigurational study of the negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014115 (2021).

Delaney, P., Greer, J. C. & Larsson, J. A. Spin-polarization mechanisms of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Nano Lett. 10, 610–614 (2010).

Chen, Y. et al. Multiconfigurational nature of electron correlation within nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 108, 045111 (2023).

Barcza, G. et al. DMRG on top of plane-wave Kohn-Sham orbitals: a case study of defected boron nitride. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 1143–1154 (2021).

Li, M., Kobayashi, R., Amos, R. D., Ford, M. J. & Reimers, J. R. Density functionals with asymptotic-potential corrections are required for the simulation of spectroscopic properties of materials. Chem. Sci. 13, 1492–1503 (2022).

Ma, H., Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Quantum simulations of materials on near-term quantum computers. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 85 (2020).

Haldar, S., Mitra, A., Hermes, M. R. & Gagliardi, L. Local excitations of a charged nitrogen vacancy in diamond with multireference density matrix embedding theory. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 4273–4280 (2023).

Sheng, N., Vorwerk, C., Govoni, M. & Galli, G. Green’s function formulation of quantum defect embedding theory. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 3512–3522 (2022).

Li, K. et al. Excited-state dynamics and optically detected magnetic resonance of solid-state spin defects from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 110, 184302 (2024).

Tóth, Z. & Pulay, P. Comparison of methods for active orbital selection in multiconfigurational calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 7328–7341 (2020).

Maze, J. R. et al. Properties of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: the group theoretic approach. New J. Phys. 13, 025025 (2011).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Theory of the optical spin-polarization loop of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085207 (2018).

Takács, I. & Ivády, V. Accurate hyperfine tensors for solid state quantum applications: case of the NV center in diamond. Commun Phys. 7, 178 (2024).

Dapprich, S., Komáromi, I., Byun, K., Morokuma, K. & Frisch, M. J. A new oniom implementation in Gaussian98. Part i. The calculation of energies, gradients, vibrational frequencies and electric field derivatives1dedicated to Professor Keiji Morokuma in celebration of his 65th birthday1. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 461–462, 1–21 (1999).

Dunning, T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023 (1989).

Helgaker, T., Klopper, W., Koch, H. & Noga, J. Basis-set convergence of correlated calculations on water. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 9639–9646 (1997).

Pansini, F. N. N., Neto, A. C. & Varandas, A. J. C. Extrapolation of Hartree-Fock and multiconfiguration self-consistent-field energies to the complete basis set limit. Theor. Chem. Acc. 135, 261 (2016).

Thiering, G. & Gali, A. Ab initio calculation of spin-orbit coupling for an NV center in diamond exhibiting dynamic Jahn-Teller effect. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081115 (2017).

Khedkar, A. & Roemelt, M. Extending the ass1st active space selection scheme to large molecules and excited states. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 16, 4993–5005 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. First-principles framework for the prediction of intersystem crossing rates in spin defects: the role of electron correlation. Phys. Rev. Lett 135, 036401 (2025).

Sarkar, R., Loos, P.-F., Boggio-Pasqua, M. & Jacquemin, D. Assessing the performances of CASPT2 AND NEVPT2 for vertical excitation energies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 2418–2436 (2022).

Kehayias, P. et al. Infrared absorption band and vibronic structure of the nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 88, 165202 (2013).

Davies, G., Hamer, M. F. & Price, W. C. Optical studies of the 1.945 eV vibronic band in diamond. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 348, 285–298 (1976).

Gali, A., Fyta, M. & Kaxiras, E. Ab initio supercell calculations on nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond: electronic structure and hyperfine tensors. Phys. Rev. B 77, 155206 (2008).

Gali, A., Janzén, E., Deák, P., Kresse, G. & Kaxiras, E. Theory of spin-conserving excitation of the N-V− center in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 186404 (2009).

Luu, M. T., Younesi, A. T. & Ulbricht, R. Nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: discovery of additional electronic states. Mater. Quantum Technol. 4, 035201 (2024).

Rogers, L. J., Armstrong, S., Sellars, M. J. & Manson, N. B. Infrared emission of the NV centre in diamond: Zeeman and uniaxial stress studies. New J. Phys. 10, 103024 (2008).

Davies, G. Vibronic spectra in diamond. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 7, 3797 (1974).

Goldman, M. L. et al. Phonon-induced population dynamics and intersystem crossing in nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 145502 (2015).

Kobayashi, M. & Nisida, Y. High pressure effects on photoluminescence spectra of color centers in diamond. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 32, 279 (1993).

Doherty, M. W. et al. Electronic properties and metrology applications of the diamond NV− center under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 047601 (2014).

Guler, E. & Güler, M. Elastic and mechanical properties of cubic diamond under pressure. Chin. J. Phys. 53, 195–205 (2015).

Bersuker, I.The Jahn-Teller Effect (University of Texas, 2006).

Alkauskas, A., Yan, Q. & Van de Walle, C. G. First-principles theory of nonradiative carrier capture via multiphonon emission. Phys. Rev. B 90, 075202 (2014).

Loubser, J. H. N. & van Wyk, J. A. Electron spin resonance in the study of diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 41, 1201 (1978).

Biktagirov, T., Schmidt, W. G. & Gerstmann, U. Spin decontamination for magnetic dipolar coupling calculations: application to high-spin molecules and solid-state spin qubits. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 022024 (2020).

Ham, F. S. Effect of linear Jahn-Teller coupling on paramagnetic resonance in a 2e state. Phys. Rev. 166, 307–321 (1968).

Batalov, A. et al. Low temperature studies of the excited-state structure of negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy color centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 195506 (2009).

Goldman, M. L. et al. Erratum: State-selective intersystem crossing in nitrogen-vacancy centers [Phys. Rev. B 91, 165201 (2015)]. Phys. Rev. B 96, 039905 (2017).

Siegbahn, P., Heiberg, A., Roos, B. & Levy, B. A comparison of the super-ci and the Newton-Raphson scheme in the complete active space SCF method. Phys. Scr. 21, 323 (1980).

Roos, B. O., Taylor, P. R. & Sigbahn, P. E. A complete active space SCF method (CASCF) using a density matrix formulated super-ci approach. Chem. Phys. 48, 157–173 (1980).

Siegbahn, P. E. M., Almlöf, J., Heiberg, A. & Roos, B. O. The complete active space SCF (CASSCF) method in a Newton-Raphson formulation with application to the HNO molecule. J. Chem. Phys. 74, 2384–2396 (1981).

Schapiro, I., Sivalingam, K. & Neese, F. Assessment of n-electron valence state perturbation theory for vertical excitation energies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 3567–3580 (2013).

Helmich-Paris, B. Benchmarks for electronically excited states with CASSCF methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 4170–4179 (2019).

Babar, R. et al. Low-symmetry vacancy-related spin qubit in hexagonal boron nitride. npj Comput Mater 10, 184 (2024).

Benedek, Z. et al. Symmetric carbon tetramers forming spin qubits in hexagonal boron nitride. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 187 (2023).

Angeli, C., Cimiraglia, R., Evangelisti, S., Leininger, T. & Malrieu, J.-P. Introduction of n-electron valence states for multireference perturbation theory. J. Chem. Phys. 114, 10252–10264 (2001).

Angeli, C., Cimiraglia, R. & Malrieu, J.-P. n-electron valence state perturbation theory: a spinless formulation and an efficient implementation of the strongly contracted and of the partially contracted variants. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 9138–9153 (2002).

Angeli, C., Pastore, M. & Cimiraglia, R. New perspectives in multireference perturbation theory: the n-electron valence state approach. Theor. Chem. Acc. 117, 743–754 (2007).

Møller, C. & Plesset, M. S. Note on an approximation treatment for many-electron systems. Phys. Rev. 46, 618–622 (1934).

Dyall, K. G. The choice of a zeroth-order Hamiltonian for second-order perturbation theory with a complete active space self-consistent-field reference function. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 4909–4918 (1995).

Guo, Y., Sivalingam, K. & Neese, F. Approximations of density matrices in N-electron valence state second-order perturbation theory (NEVPT2). I. Revisiting the NEVPT2 construction. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 214111 (2021).

Kollmar, C., Sivalingam, K., Guo, Y. & Neese, F. An efficient implementation of the NEVPT2 and CASPT2 methods avoiding higher-order density matrices. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 234104 (2021).

Guo, Y., Sivalingam, K., Valeev, E. F. & Neese, F. SparseMaps—a systematic infrastructure for reduced-scaling electronic structure methods. III. linear-scaling multireference domain-based pair natural orbital n-electron valence perturbation theory. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 094111 (2016).

Guo, Y. et al. SparseMaps—a systematic infrastructure for reduced-scaling electronic structure methods. VI. Linear-scaling explicitly correlated n-electron valence state perturbation theory with pair natural orbital. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 124120 (2023).

Roemelt, M., Maganas, D., DeBeer, S. & Neese, F. A combined DFT and restricted open-shell configuration interaction method including spin-orbit coupling: application to transition metal L-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 204101 (2013).

Neese, F. Efficient and accurate approximations to the molecular spin-orbit coupling operator and their use in molecular g-tensor calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 034107 (2005).

Neese, F. & Solomon, E. I. Calculation of zero-field splittings, g-values, and the relativistic nephelauxetic effect in transition metal complexes. application to high-spin ferric complexes. Inorg. Chem. 37, 6568–6582 (1998).