Abstract

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) have attracted increasing attention due to their unique structural and functional properties. In the study of HEAs, thermodynamic properties and phase stability play a crucial role, making phase diagram calculations significantly important. However, phase diagram calculations with conventional CALPHAD assessments based on experimental or ab-initio data can be expensive. With the emergence of machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs), we have developed a program named PhaseForge, which integrates MLIPs into the Alloy Theoretic Automated Toolkit (ATAT) framework using our MLIP calculation library, MaterialsFramework, to enable efficient exploration of alloy phase diagrams. Moreover, our workflow can also serve as a benchmarking tool for evaluating the quality of different MLIPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-entropy alloys (HEAs) have attracted intense research interest because their vast compositional space offers unprecedented combinations of strength, ductility, and thermal stability1,2. A primary requirement for alloy discovery is phase-stability prediction—knowing which phases are thermodynamically favored as functions of composition, temperature, and pressure. Phase-diagram computations are therefore central to modern alloy design. Although high-throughput, first-principles-based phase-diagram workflows have grown rapidly in recent years3, accurate and efficient prediction of multicomponent phase stability remains a cornerstone challenge in materials science.

Classical CALPHAD assessments4 provide formal, reproducible, and rigorous routes to thermodynamic databases for binary and ternary systems, with higher-order behavior inferred by extrapolation. Yet, fewer than ~3500 ternary phase diagrams have been experimentally determined out of roughly 1.3 × 105 possible ternaries, meaning that only about 3% of all ternary systems are even partially characterized5. However, the weeks to months of expert parameter optimization they require limit the scalability and predictive power in unexplored chemical spaces, particularly those relevant to HEAs and other compositionally complex materials. To overcome these limitations, researchers are increasingly using (1) density functional theory on special quasirandom structures (SQS) to approximate random atomic configurations6,7,8,9; (2) large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to capture temperature-dependent thermodynamic properties10,11; and (3) cluster expansion Hamiltonians fitted to ab-initio data to model configurational contributions to alloy energetics12,13. While such workflows are capable of facilitating the exploration of thermodynamic spaces that have yet to be explored experimentally, their computational cost still scales combinatorially with element count, underscoring the need for faster yet equally reliable surrogates for multicomponent phase-diagram prediction.

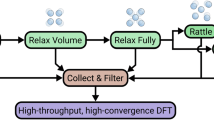

Recent advances in machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) offer a promising alternative to accelerate phase diagram calculations by bridging quantum-mechanical accuracy with the efficiency required for large-scale thermodynamic modeling14. In our previous work15, we introduced a benchmarking framework that demonstrated the potential of MLIPs to predict formation energies and phase stability in alloy systems with high fidelity. Although this study highlighted the feasibility of MLIP-based phase diagram computation, the methodology remained limited in scope and flexibility. In this work, we present an expanded and fully automated computational workflow that integrates MLIPs with our MaterialsFramework library into the phase diagram calculation pipeline with the Alloy-Theoretic Automated Toolkit (ATAT)7,16. Our newly developed code, named PhaseForge, introduces several key features, including support for multiple MLIP frameworks, automated structure sampling, vibrational free energy estimation, MD calculations of liquid phase, and compatibility with CALPHAD-style database generation. These capabilities enable high-throughput phase diagram predictions across a wide range of alloy systems, including those lacking prior thermodynamic assessments. In Fig. 1, we present the workflow of our framework.

We validate our workflow through three examples—the Ni-Re binary system, the Cr-Ni binary system, and the Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V quinary system. The Ni-Re system contains FCC, HCP, and liquid phases, and two intermetallic compound phases with multi-sublattices are predicted. The results of several MLIPs are compared with ab-initio calculations and experimental reports, illustrating how our framework can be used to benchmark the MLIPs from a thermodynamics perspective. The Cr-Ni binary system contains mechanically unstable FCC Cr and BCC Ni phases and some mechanically unstable SQS’s. This example shows how PhaseForge addresses mechanical instability in CALPHAD modeling. For the Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V HEA system, we include all the binary and ternary sub-systems and demonstrate the effectiveness in capturing phase stability trends in both stable and metastable regions of the phase diagram.

Our approach highlights the growing contribution of machine learning to materials science—enabling data-driven alloy design and accelerating the exploration of previously inaccessible materials spaces. Conversely, constructing phase diagrams with various MLIPs using our workflow offers materials science a way to give back—by providing a practical and application-oriented framework for evaluating the effectiveness of MLIPs.

Results

Ni-Re binary system

Ni-Re alloys are widely used in aerospace engineering owing to their robust strength under high-temperature conditions. Levy et al. predicted several novel intermetallic compounds in Re-based alloys, including two potential new phases in the Ni-Re system - the D019 NiRe3 phase and the D1a Ni4Re phase. In our previous work9, we used ATAT in combination with VASP to investigate potential intermetallic compound phases. A phase diagram including the FCC_A1, HCP_A3, D019, D1a, and liquid phases was constructed. In this work, we apply the new MLIP-based framework to reproduce the phase diagram with improved efficiency. The detailed workflow is presented below:

-

Construct the SQS of D019 and D1a phases;

-

Generate Ni-Re SQS of various phases and compositions with ATAT;

-

Optimize the structures and calculate energies at 0 K using MLIP;

-

Perform MD simulations on liquid phase of different compositions (with ternary search);

-

Fit all the energies with CALPHAD modeling using ATAT;

-

Construct the phase diagram with Pandat.

A terms.in

1,0 2,0

is applied for the FCC_A1, HCP_A3 and liquid phases to include the binary interactions to the level 0, while a terms.in

1,0:1,0 2,0:1,0

is applied to include only the binary interactions on a single sub-lattice to the level 0, for the D019 and the D1a phases. Vibrational contributions are not included in our calculations, as some MLIPs may exhibit insufficient precision in forces and stresses calculations. In Fig. 2a, we illustrate the phase diagram calculated with VASP (in dashed blue lines) and Grace (with Grace-2L-OMAT model, in red solid lines), with some results from experiments previously reported17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. The result calculated with Grace captures most of the topology successfully and shows good agreements with VASP result, in spite of more stability of the intermetallic compounds, and a lower peritectic temperature of FCC_A1 and HCP_A3 (2044 °C from VASP and 1631 °C from Grace). In addition, the allotropic transition for pure Re at high temperature, which is an artifact of using a simple harmonic model for the phonon free energy, disappears in Grace results, since no vibrational contributions are considered. It should be noted that, although the Grace result appears to show better agreement with experimental data, this does not indicate a higher accuracy compared with VASP. MLIPs are trained on energies from ab-initio calculations, and the apparent match in this case may result from a coincidental cancellation of errors arising from the MLIP modeling, the energy database, the ATAT workflow, and the CALPHAD modeling. It is also worth noting that, although PhaseForge and the Grace MLIP do not directly support spin-polarized calculations, MLIPs are generally trained on datasets derived from spin-polarized DFT. Consequently, the predictions by PhaseForge and MLIPs implicitly incorporate spin-polarization effects and can successfully reproduce the Ni-Re phase diagram, in which Ni is ferromagnetic at room temperature.

a Phase diagram of Ni-Re system with FCC_A1, HCP_A3, D019, D1a, and liquid phases, calculated with VASP and Grace; b True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) regions of D1a phase calculated with VASP and Grace; c Phase diagram calculated with SevenNet. SevenNet gradually overestimates the stability of intermetallic compounds, especially the D019 phase; d Phase diagram calculated with CHGNet. Large errors in the calculated energies result in an incorrect topology of the phase diagram. All phase diagrams are plotted with Pandat.

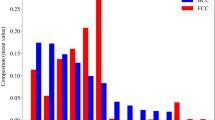

Inspired by ref. 25, we use the ZPF lines as classifiers for the phases to apply a classification evaluation. In Fig. 2b, we show the True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), and False Negative (FN) regions of D1a phase field calculated with VASP and Grace. The D1a phase field enclosed by the ZPF lines is colored red for VASP and blue for Grace, and the overlapped purple region stands for the True Positive. In Fig. 2c, d, we illustrate the phase diagram calculated with SevenNet (version SevenNet-MF-ompa) and CHGNet (version 0.3.0). The SevenNet gradually overestimates the stability of intermetallic compounds, especially the D019 phase. For CHGNet, the energies are calculated with large errors; therefore, the phase diagram is largely inconsistent with thermodynamic expectations. In Table 1, we illustrate classification error metrics for Grace, SevenNet, and CHGNet across different phases, with VASP results as ground truth. Most of the error metrics for Grace are better than the others, suggesting that the Grace model is relatively more reliable and accurate in this context. This example shows how phase diagram computations with our workflow may serve as an effective tool to assess and compare the quality of different MLIPs from a thermodynamic perspective, efficiently, quantitatively, and accurately.

Cr-Ni binary system

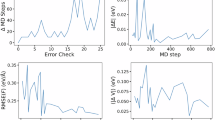

In the Cr-Ni binary system, the ground state of Cr is BCC, and the ground state of Ni is FCC. FCC structures on the Cr-rich side and BCC structures on the Ni-rich side are mechanically unstable. In this example, we generate SQS structures of both BCC and FCC up to level 5 and relax them using Grace-2L-OMAT. The relaxation magnitude is evaluated with the checkrelax command in ATAT and plotted in Fig. 3a. For the end members, no supercells are used in relaxation, and the symmetry is constrained. We adapt the VASP-calculated data and inflection-detection results reported in Table S2. For unstable SQSs, using the default relaxation magnitude cutoff of 0.05, we retain the energies within the mechanically stable region and omit those in the unstable region.

a Relaxation magnitude of BCC and FCC SQSs. Mechanically stable regions are defined by a cutoff of 0.05; b Formation enthalpies of Cr-Ni FCC SQSs and polynomial CALPHAD fittings with various strategies using different sets of data points; c Cr-Ni binary phase diagram calculated with PhaseForge and Grace MLIP, incorporating VASP inflection-detection results of pure elements and excluding mechanically unstable SQSs in the CALPHAD fitting. The phase diagram is plotted with Pandat.

Figure 3b illustrates the formation enthalpies of Cr-Ni SQSs, referenced to the VASP inflection-detection energy of FCC Cr and the VASP energy of FCC Ni. Blue crosses denote the formation enthalpies of relaxed SQSs computed with Grace MLIP, while pink circles indicate the VASP inflection-detection energies. In ATAT, a conventional approach to polynomial CALPHAD modeling of the FCC phase uses all mechanically stable SQS data (blue crosses) along with the inflection-detection energies (pink circles), including FCC Cr, to obtain the polynomial fit to level 2 (denoted as Fit 1), which we treat as the ground-truth reference. In PhaseForge, by applying a relaxation magnitude cutoff of 0.05, the fit (Fit 2) uses only the mechanically stable SQS data and the pre-calculated VASP inflection-detection energy of FCC Cr. Fit 2 shows excellent agreement with Fit 1, demonstrating the reliability of the PhaseForge simplified workflow.

For contrast, we also perform polynomial fits using all SQS energies, including those with large distortions during relaxations in the mechanically unstable region. The fit, including VASP inflection-detection FCC Cr is labeled Fit 3, while the one using symmetry-constrained FCC Cr (the PhaseForge default output when no VASP inflection-detection results are supplied) is Fit 4. We notice that the energies of mechanically unstable SQSs toward the BCC Cr ground state (marked by a blue asterisk) rather than FCC Cr, and the resulting fits deviate significantly from the data points and ground-truth Fit 1. This highlights that the energies of mechanically unstable SQSs obtained by simple relaxation, without inflection detection, should be excluded from fitting.

Fit 5 represents another common CALPHAD practice, where extrapolation is applied using only stable region data points. In this case, FCC Cr is predicted with a higher energy, and the polynomial fit shows poor agreement with Fit 1. Moreover, such extrapolation can introduce inconsistencies in multicomponent systems; for instance, FCC Cr extrapolated from the Cr-Ni and Cr-Fe directions may differ, leading to discrepancies in CALPHAD modeling of the Cr-Ni-Fe ternary system. In contrast, PhaseForge Fit 2 shows that simply including the pre-calculated VASP inflection-detection energy of mechanically unstable FCC Cr not only avoids the mismatch between extrapolations from different binary directions but also gradually improves the polynomial fitting compared with the ground-truth Fit 1. The Cr-Ni binary phase diagram obtained with PhaseForge and Grace MLIP is shown in Fig. 3c, where pre-calculated VASP inflection-detection results of pure elements are included, and all mechanically unstable SQS are excluded from the fitting of CALPHAD modeling.

It is worth mentioning that the ATAT + VASP + inflection-detection Fit 1, which requires VASP inflection-detection calculations for SQSs can be highly expensive. For example, a single 32-atom FCC SQS requires more than 50 CPU hours on 8 cores, even with ENCUT reduced to 300 eV. By comparison, PhaseForge completes the entire workflow, including relaxation, data selection, and polynomial fitting, for the FCC Cr-Ni system in 15 min on a single CPU, with only a small error, and does not require MLIP force or stress prediction accuracy.

Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V HEA System

HEA systems based on the Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V are attracting increasing attention, and several previous studies have explored their thermodynamic properties both experimentally and computationally26,27,28. However, experimental studies can be costly, and some computational approaches rely on thermodynamic databases and expensive ab-initio calculations (compared to MLIP-based methods). In the calculation, we only consider the FCC_A1, BCC_A2, HCP_A3 solid phases and the liquid phase. No intermetallic compounds are taken into account as that would mess the phase diagram with multi-elements. All the SQS’s are previously generated and employed in ATAT. For all the structure relaxations and energy calculations on SQS, we use the Grace-2L-OMAT model29 for MLIP calculations, with the force convergence criterion f_max = 0.001. For liquid phase, we use the ternary search methods from range 0.7 to 1.0 with a target of 0.02. MD simulations of the liquid phase are performed with ASE using the Grace-2L-OMAT model, with an NVT ensemble for each structure in ternary search for 2 ps. First-principles results of pure elements in all solid phases are adapted from our database and shown in Table S2. Mechanically unstable phases, including FCC-Cr, BCC-Co, BCC-Ni, and FCC-V have energy and vibrational entropy calculated with inflection detection method with VASP and previously added in our database. The thermodynamic data for these four phases with mechanical instability from SGTE database are excluded by creating an exfromsgte.in file. To fit all the thermodynamic data, we use a terms.in

1,0 2,1 3,0

to include the binary interactions to the level 1 and the ternary interactions to the level 0 for solid phases. For liquid phase, we only consider binary interactions to the level 0 (regular solution model). Short-range ordering corrections are included for all the solid phases. With the TDB file created with our method, we use Pandat30 to plot the phase diagrams.

In Fig. 4, we present all 10 binary phase diagrams. Compared with previously reported experimental and computational results31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, most of our predicted phase diagrams show good agreement. Despite the omission of intermetallic compounds in our analysis, the overall topology of most phase diagrams is successfully captured by our method. However, there are some issues to note. First, the HCP phase appears to be overstabilized, particularly in systems containing Cr. To verify the HCP phase energies, we take the Co-Cr system as an example. We examined the relaxed SQS structures and their energies for all three solid phases. For Co0.25Cr0.75 at 0 K, the energies are −8.8017 eV/atom for HCP, −8.7986 eV/atom for FCC, and −8.7949 eV/atom for BCC. The energy difference is smaller than 0.007 eV/atom, or about 675 J/mol. The small energy difference at 0 K indicates that the instability of HCP phase at high temperature is due to the vibrational entropy. Since HCP Cr is mechanically unstable40, we use the inflection-detection method with VASP to compute its energy and vibrational entropy. For all phonon contributions, we calculate only the pure end members and approximate intermediate compositions using linear interpolation, in order to reduce computational cost and simplify the model. In other words, for SQS such as HCP Co0.25Cr0.75, the energy is obtained from MLIP calculations of HCP, while the vibrational entropy is derived from a linear combination of those for HCP Co and inflection point of Cr, which may contribute to the observed discrepancies with experiments39. Besides, we do not consider intermetallic compounds like the σ phase in Co-Cr system, which is observed in experiments and may potentially conceal the existence of HCP. The similar issue also arises in the Co-Ni phase diagram31, where a single phase region of BCC wrongly appears at high temperature between x(Ni) = 0.4 to x(Ni) = 0.6, as both BCC Co and Ni are mechanically unstable, and we used inflection detection method for the energy and vibrational contributions. Careful inflection-detection and vibrational entropy calculations on each SQS could resolve this issue, but they require significantly more computational time and demand high accuracy of the MLIP model-not only for energies, but also for forces and stresses. Figure 5 presents all the ternary phase diagrams at temperature of 1400 K generated by our workflow within the quinary system.

a Co-Cr; b Co-Fe; c Co-Ni; d Co-V; e Cr-Fe; f Cr-Ni; g Cr-V; h Fe-Ni; i Fe-V; j Ni-V. Most of our predicted phase diagrams show good agreement with previously reported experimental results. The HCP phase is overstabilized in some cases, with a small energy difference from the real ground-state FCC or BCC phase. Intermetallic compounds are not considered in this example. All phase diagrams are plotted with Pandat.

For a reference of time cost, the relaxation and energy calculation on a SQS (from 32 atoms to 48 atoms for all the phases) takes 1 to 4 minutes calculation on a single CPU core. The ternary search of MD calculations for one structure (with 32 to 48 atoms depending on the composition) takes about 2–3 h on a single CPU core. In total we have 70 solid SQS for each solid phase and 75 liquid structures; therefore the whole process takes less than 10 h for only the solid phases, and takes about 200 h for all the calculations including the liquid phase, all on a single CPU core. For contrast, relaxation and energy calculations on one SQS using VASP would take from several hours to tens of hours on a single node with 8 cores, which is thousands of the CPU time of our method.

Disscussion

In this work, we introduce our code PhaseForge and MaterialsFramework for exploring phase diagrams through CALPHAD modeling, integrating ATAT and MLIPs. Several novel features are implemented and introduced in detail, including energy fitting that combines data from ab-initio calculations, MLIP predictions, and the SGTE database, the treatment of mechanically unstable structures, and liquid phase fitting using molecular dynamics with MLIPs. Classification evaluation method is also introduced to objectively and quantitatively evaluate phase diagrams generated with PhaseForge and benchmark MLIPs from a thermodynamic perspective. In addition, we present the Ni-Re system, the Cr-Ni system and the Co-Cr-Fe-Ni-V HEA system as case studies.

Compared to phase diagram studies based on experiments or ab-initio calculations, our method is significantly more efficient – typical phase diagram calculations using the ATAT-VASP workflow may require thousands of times more CPU time than our approach. On the other hand, compared to calculations based on existing thermodynamic databases, our method enables users to investigate thermodynamic properties of potential new phases or multi-element interactions that are not yet included in existing databases. Our method can be applied to high-throughput calculations of HEA phase diagrams, benefiting from its wide applicability and high efficiency. In future work, UMAP-based visualization of single-phase regions could also be applied to our computational results. The thermodynamic results can also be implemented as an initial guess or reference for active learning frameworks, and be iteratively refined with data from experiments and other calculations41,42,43.

Nonetheless, our method represents a trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy. Due to possible inaccuracies in the MLIP-predicted energies, stresses, and forces, the predicted phase diagram topology, particularly at high temperatures-may deviate from reality. Therefore, it is important to carefully examine the phase energies in the generated TDB file.

However, the existence of inaccuracy is not always a drawback. Generating phase diagrams with various MLIPs using our framework and comparing the inaccuracy offers a new perspective for evaluating the performance of MLIPs. In materials science, it is often the energy differences, rather than the absolute energy values, that determine the phase stability and carry greater significance. Traditional evaluations by machine learning researchers typically involve comparing predicted energies, forces and stresses with reference databases to assess accuracy. In contrast, our method enables the construction of phase diagrams, allowing even an MLIP that exhibits systematic bias in absolute energies to demonstrate its usefulness-if it can still produce correct phase stability and topology. Conversely, we might also lower our assessment of MLIPs that fail to correctly predict phase diagrams. While such models may accurately reproduce absolute energy values, they can misrepresent the relative ordering of phase energies, leading to incorrect predictions of phase stability-and thus may be of limited value in materials science applications. In addition, the impact of inaccuracies in force and stress predictions from MLIPs—highly nonlinear and black-box-like in ATAT workflow—can be efficiently and concisely interpreted through PhaseForge phase-diagram predictions and subsequently used to benchmark MLIPs. This highlights a more application-driven criterion for evaluating MLIPs in materials science.

Methods

Compound energy formalism

Phase diagrams are constructed with the compound energy formalism (CEF)44 and exported as standard TDB files that downstream CALPHAD software can read without modification. In the ATAT workflow, we first generate SQSs for each disordered phase and evaluate their total energies with MLIPs; ordered phases are handled with fully relaxed stoichiometric cells. Every mixing or formation energy is referenced to the Gibbs free energies of the corresponding unary reference phases (e.g., FCC Ni, HCP Co, BCC V) provided by the SGTE database45.

Preserving these SGTE reference states is necessary as even a small shift would mis-rank the relative stabilities of competing phases, rendering the resulting TDB file CALPHAD-incompatible and undermining subsequent extrapolation to higher-order systems. By anchoring MLIP energies to the SGTE scale, our workflow guarantees that all derived interaction parameters remain thermodynamically consistent and immediately usable in conventional CALPHAD assessments and databases.

For the basic model, we assume that the Gibbs free energy contains an ideal configurational entropy of mixing with a potentially non-ideal enthalpy of mixing7:

where E and G denote, respectively, the per-atom internal energy and Gibbs free energy. We include only the ideal configurational entropy of mixing, Sid. The symbols αi represent the unary reference phases for element i (e.g., BCC, FCC, HCP), while β designates the multicomponent phase under consideration. The vector y collects the site fractions of each constituent in phase β; xi is the overall atomic fraction of element i in the alloy. Pressure-volume (PV) work is neglected because all phases treated here are condensed and experience only negligible volume changes within the temperature range of interest.

For improved accuracy, one can add phonon contributions to the modeling for the end members of each ordered phase; in other words, we have phonon contributions that are configuration independent. The free energy is given by:

with yj the vector of site fractions of an end member j, and wj denotes the weights of each end member in y – \(\sum _{j}{w}^{j}{y}^{j}=y\). The GML are the Gibbs free energy calculated with machine learning potentials, with energy and phonon contributions.

For maximum accuracy, configuration-dependent phonon contributions can also be included. In that case, the Gibbs free energy is written as

where the subscript “nc” indicates free energies with no configurational entropy contributions.

Molecular dynamics for the liquid phase

Reliable phase-diagram predictions require an accurate description of the liquid state, because the liquid sets the upper limit of thermodynamic stability at extreme operating temperatures and governs many alloy-processing routes (e.g. casting, welding, additive manufacturing). To obtain these properties, we perform MD simulations to evaluate the average free energy of the liquid phase, using the ASE framework46 with Nos-Hoover ensembles47. Although temperature-dependent liquid free energies of pure elements are available from the SGTE database, MD calculations on liquid-alloy SQS are still required to obtain the mixing free energies. These alloy MD data place the liquid phase on the same thermodynamic footing as the solid phases, eliminating systematic bias in subsequent solidus and liquidus predictions.

For pure elements, we set the temperature T0 = Tm + ΔT, with Tm the melting point and ΔT = 50 K by default. For alloy systems, the temperature is set as linear-combination of melting points of compositions:

The liquid SQS configurations is pre-generated in ATAT at various compositions. As the MD simulation with NPT ensemble may converge slowly under the ASE framework by our experience, we offer two options in our code to obtain the MD energy.

An option is the ternary search in the ASE framework. To obtain the energy at equilibrium, it is necessary to optimize the volume at which the total energy reaches its minimum. The total energy is expected to decrease monotonically with increasing volume until it reaches a minimum, after which it increases monotonically. We define a scaling factor c = l/l0, where l and l0 are the box length of the liquid structure in MD simulation and SQS, respectively. Within a range of scaling factor \(\left[{c}_{L},{c}_{R}\right]\) containing the equilibrium one (typically 0.7 to 1.0 from our experience), for each iteration, we pick c1 = 2cL/3 + cR/3 and c2 = cL/3 + 2cR/3, performing MD simulation with scaling factor c1 and c2, and comparing the total energies. If E(c1) > E(c2), we search for the equilibrium structure within [c1, cR] for the next iteration; otherwise, we search within [cL, c2]. After approximately six iterations, the search range of the scaling factor can be narrowed to within 0.02, with the total energy difference reduced to less than 30 meV/atom based on our calculations. The whole process takes about 2 to 3 hours for SQS with 32 atoms on a single CPU core, depending on the MLIP used in the calculation.

Another option we implemented in our framework is to apply the MLIP to LAMMPS48,49. For each structure, we generate a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of the SQS in ATAT and run MD with the NPT ensemble at P = 0 for 30 ps, following with an NVT ensemble for another 30 s. The final energy is derived from the average of NVT total energies in each step.

Phonon and mechanical instabilities

For phonon calculations, we apply the Born von Karman spring model by fitting the reaction forces from supercells with imposed atomic displacements50, which is applied in the fitfc code in ATAT51.

Mechanical instabilities-manifested as negative elastic constants or imaginary phonon modes-are common in solid systems. By contrast, CALPHAD assessments assume that every phase possesses a single, composition-continuous Gibbs-energy surface across the whole alloy space. A common remedy is to extrapolate the Gibbs energy from the mechanically stable region into the unstable composition range, yet extrapolations taken along different paths need not coincide and can even fall below the energy of the true stable phase. In the Co-Nb-V ternary, for example, the BCC Gibbs energy of pure Co obtained by extrapolating the Nb-Co binary differs from that obtained via the V-Co binary, occasionally yielding an unrealistically low value for BCC Co.

To eliminate such ambiguities, we adopt the inflection detection (ID) procedure implemented in ATAT40. ID locates the composition where the Gibbs energy curvature changes sign, the mechanical stability limit, and uses that state as a consistent thermodynamic reference, thereby avoiding ad hoc extrapolations. The ID option is disabled by default but can be activated with the -id flag. We also provide pre-computed ID-corrected unary data for 31 common metallic elements in BCC, FCC, and HCP structures, which users may import directly into their CALPHAD workflows.

Considering that some SQS structures can be mechanically unstable, their relaxation may cause significant distortions that break symmetry and artificially lower the energy. In ATAT, the magnitude of relaxation is defined as the square root of the sum of each element of the strain tensor squared, where the strain tensor is the one that needs to be applied to the unit cell of unrelaxed structure to get the unit cell of relaxed structure, neglecting isotropic scaling and rigid rotations. Since MLIP-based inflection detection can be unreliable due to limited accuracy in force and stress predictions, PhaseForge enables users to exclude any SQS with relaxations larger than a user-defined cutoff (recommended values: 0.05-0.1). Nevertheless, for pure elements, inflection detection still needs to be applied to avoid errors when extrapolating energetic data into mechanically unstable regions.

Database for pure elements with ab-initio calculations

The phonon computations and the inflection detection method require very accurate calculations of forces and stresses. Thus far, most MLIPs have shown good agreement with energies, but perform poorly in reproducing forces and stresses compared to ab-initio results. Therefore, based on ab-initio calculations, we construct a database for several common metallic elements in BCC, FCC, and HCP lattices, containing energies and vibrational entropies, including those obtained via inflection-detection for mechanically unstable phases. The ab-initio calculations are performed with Vienna Ab-inito Simulation Package (VASP)52,53,54,55, using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange and correlation functional at level of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)56. The cutoff energy is set as 1.3 times the ENMAX in the pseudopotential files in the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method57. K-points per reciprocal atom is set as 8000 for all calculations. The data can be used to replace for \({E}_{\,\text{ML}\,}^{{\alpha }_{i}}\) in Eq. (1), \({G}_{\,\text{ML}\,}^{{\alpha }_{i}}\left(T\right)\) in Eq. (2), or \({G}_{\,\text{ML,nc}\,}^{{\alpha }_{i}}\left(T\right)\) in Eq. (3).

In addition, for some thermodynamically stable phases with phonon instabilities under harmonic approximation, the “dynamical stabilization”, such as hopping between local minima, guarantees the stability at a macroscopic level. One prime example would be BCC β titanium, which is stable above 880 °C. We recommend the recent Piecewise Polynomial Potential Partitioning (P4) method58,59 for free energy calculations. The calculations should be performed separately and manually re-visit the energy file. A database with energies and vibrational entropies of 31 common metallic elements is constructed and illustrated in Supplementary Section C. The mechanical instability information of the phases is adopted from ref. 40, and the energies and vibrational entropies are compared with data from40,60.

Other modeling considerations

As provided in ATAT, short-range order can be accounted for by adding an extra free-energy term GSRO calculated with the Cluster Variation Method (CVM)61. In our workflow, this correction is applied only to single-sublattice phases, where it offsets the over-stabilisation of a fully disordered solid solution. For multi-sublattice phases, the long-range ordering is treated explicitly, and an additional SRO term would spuriously lower the energy7. The SRO correction is therefore off by default and can be enabled with the -sro flag.

By default, the unary end-member references are the thermodynamic data in the SGTE database. One can exclude the data from the SGTE database of particular phases by creating a file exfromsgte.in. For example, for BCC Al which is mechanically unstable, we may add SGTE_BCC_A2_AL to the exfromsgte.in to exclude the SGTE data, and the \({G}^{{\rm{BCC}}}\left(T\right)\) would be denoted as

instead of \({G}_{\,\text{SGTE}}^{\text{BCC}\,}\left(T\right)\), where the “calc” denotes the free energies calculated with MLIPs, or obtained from our database calculated with ab-initio. This would be useful for phases that are mechanically unstable and where inflection detection is implemented, as it may lead to a discrepancy between SGTE data and calculations.

Classification evaluation and MLIP benchmarking

The evaluation of MLIP performance for phase diagram prediction is nontrivial, as it cannot be reduced to the prediction of scalar or even tensorial quantities. In our previous work15, we illustrated some examples evaluating phase diagrams by comparing the highest temperature of miscibility gaps and the topology agreements. To objectively and quantitatively evaluating the performance of MLIPs in phase diagram prediction, we adapt the classification evaluation method in this work.

In a binary phase diagram-or in a two-dimensional projection of a multicomponent system-a zero phase fraction (ZPF) line denotes the locus where a given phase disappears, i.e., where its fraction becomes zero62. This idea extends naturally to higher dimensions, where ZPF hypersurfaces mark the limits of thermodynamic stability for each phase. Collectively, the ensemble of ZPF lines (or hypersurfaces) defines the full phase diagram. Because each ZPF line separates regions where a phase is stable from those where it is absent, they can be viewed as phase-specific decision boundaries. This binary character invites a machine learning analogy: a ZPF line functions as a classifier for the stability of a single phase, regardless of whether it is obtained via CALPHAD, first-principles methods, or MLIPs. In fact, Morral and Gupta anticipated this idea decades ago by proposing figures-of-merit for phase diagram predictions based on ZPF analysis63.

Within this framework, the predictive ability of an MLIP as a phase diagram generator can be evaluated using standard classification metrics. Comparing MLIP-predicted regions to ground-truth boundaries (from experiment or VASP calculations) allows each point in composition-temperature space to be categorized as True Positive (TP), True Negative (TN), False Positive (FP), or False Negative (FN). From these, conventional error metrics can be defined as follows:

Accuracy measures the overall fraction of correctly classified areas among all samples, providing a general sense of correctness. Precision quantifies the fraction of predicted positive cases that are truly positive, reflecting the reliability of positive predictions. Recall measures the proportion of actual positive cases that are correctly identified, indicating the ability to capture all relevant cases. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, serving as a balanced metric when both false positives and false negatives are important to consider. These metrics can be effectively used to conduct a thorough evaluation of the phase diagram predictions and thereby benchmark the MLIPs.

Overall workflow and a quick inline command for phase diagram calculation

The overall workflow of phase diagram calculation using ATAT and PhaseForge would be:

-

(i)

(Optional) Incorporate the MLIP within PhaseForge (or use the MLIPs pre-integrated);

-

(ii)

(Optional) Construct SQS for phases/levels not included in ATAT database;

-

(iii)

Choose the desired elements and phases;

-

(iv)

Calculating the relaxed energies (and vibrational free energies if needed) of each structure using MLIP;

-

(v)

(Optional) Perform molecular dynamics for the liquid phase using MLIP;

-

(vi)

Fit a CALPHAD model (TDB file) for the system.

For the following, replace the text within brackets [] with appropriate user input, excluding the brackets themselves. In PhaseForge, we provide a quick inline command:

sqscal -e [Element1, Element2, ...] -l [Lattice1, Lattice2] -lv [Level] -mlip [MLIP] -model [MLIP model version] [-vib] [-sro] -checkrelax [relaxation magnitude cutoff]

where [Element1, Element2,-] is the list of element symbols in the system (the element should be included in the MLIP), the [Lattice1, Lattice2] are the standard CALPHAD crystal structure names (e.g. FCC_A1, BCC_A2), [Level] is the fineness of composition grid, [MLIP] is the machine-learning interatomic potential used in the calculation, and [MLIP model version] indicates the specific model version. [-vib] option indicates the vibrational contribution is calculated (for endmembers), and the [-sro] option indicates the short-range order correction is applied. The [-checkrelax] indicates the relaxation magnitude cutoff for mechanically unstable SQS. In this command, a ternary-search is applied for liquid with a temperature offset of 50 K, and binary interactions to the level 1 for each phase are included by default. One can modify the source code or follow the step-by-step workflow if modifications to the default parameters are needed.

Incorporate MLIP within MaterialsFramework

We achieved the integration of MLIP into our workflow using MaterialsFramework. The framework’s modular infrastructure enabled us to incorporate a selected MLIP directly into the computational pipeline with ease. Although we used a single MLIP model for all example calculations in this study, the design of MaterialsFramework makes it straightforward to substitute different MLIPs without altering the core workflow. This flexibility is a powerful feature, allowing future users to efficiently benchmark and compare MLIPs or tailor potential selection to specific alloy systems and property prediction goals.

MaterialsFramework supports a broad suite of state-of-the-art MLIPs-including GRACE, Eqv2, ORB, eSEN, and others- that have demonstrated strong performance in predicting structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties across diverse alloy systems. Table 2 lists the currently available models in MaterialsFramework along with their respective default versions. A more comprehensive list of all available versions for each model is provided in Supplementary Section A. These models are integrated via pre-configured calculators that seamlessly interface with our SQS-based pipeline, enabling efficient energy and force evaluations without the computational cost of ab-initio methods for structure relaxation, vibrational entropy calculations, and MD simulations. This modular design ensures that MLIP benchmarking and substitution can be conducted with minimal overhead, encouraging comparative analysis.

Construct special quasirandom structures

The ATAT database includes over 30 common crystal structures and their SQS (including the initial structure of liquid phase for the molecular dynamics). To generate SQS for structures not included in ATAT, or generate SQS with different level or size, we use the mcsqs module in ATAT51. First we create a folder atat/data/sqsdb/[Lattice_name] for the structure we need. Two input files are required: a rndstr.skel file that defines the structure, and a sqsgen.in file that specifies the levels and compositions on each sublattice. An example for D019 structure is in Supplementary Section B.

With the two input files, we use command

sqs2tdb -mk

to create a series of folders for each SQS, with a file named rndstr.in in each folder. In each folder, using the corrdump command in ATAT:

corrdump -l=rndstr.in -ro -noe -nop -clus -2=... -3=...

we can generate the clusters within the given range of pairs, triplets, etc. in a file named clusters.out. Then we use

mcsqs -n=[Number of atoms]

to start the Monte Carlo process searching for the SQS. The number of atoms in the supercell SQS should be a multiple of atomic sites in the primitive cell (we suggest that an SQS with 30 to 50 atoms per cell would be suitable). The mcsqs code stops if it finds a perfect match in bestsqs.out for all the correlations. Sometimes the perfect match may not exist, as we have too many clusters or the supercell is not large enough. In this case, we can manually stop the code by touch stopsqs and the bestsqs.out contains the best matched structure found currently. When the best SQS’s are constructed in each folder under atat/data/sqsdb/[Lattice_name], we are prepared for the next step.

Structures and elements selection

With MLIP and SQS prepared, we can use the sqs2tdb command in ATAT for calculation. The first step is copying the SQS from the ATAT database (or generated in Section 4.9):

sqs2tdb -cp -sp=[Element1, Element2, ...] -l=[Lattice_name] -lv=[Level]

It creates a folder with the lattice name and a file named species.in in the folder. After confirming the elements, retype the same command to create a series of folders named sqsdb_lev=[Level]_[sublattice_a]_[Element_A]=[Concentration of A in sublattice a]... for each SQS. In each folder, we have a structure file str.out in ATAT format.

Relaxed energies calculations using MLIP

To relax the structure and calculate the free energy of each SQS, first we need to generate an empty dummy vasp.wrap file in the top folder, which is required by ATAT. Use the command:

runstruct_vasp -nr

we can get the standard VASP input files INCAR, POSCAR, POTCAR, and KPOINTS. It may give error information for the missing pseudopotentials for VASP, and we can just neglect it, as we only need the POSCAR file for MLIP calculations. To relax the structure, we use

MLIPrelax -mlip=[MLIP] -model=[MLIP model version]

It generates a Python script MLIPrelax.py and launches it for the structural relaxation and calculations of energy, forces, and stresses. By using the extract_MLIP command after it, the relaxed structure is in CONTCAR and converted to the ATAT format in str_relax.out. The energy, stress, and forces are in energy, stress.out and force.out, respectively.

To make it more convenient, use command runstruct_mlip -mlip=[MLIP name] -model=[MLIP model version], which does the following:

runstruct_vasp -nr MLIPrelax -mlip=[MLIP] -model=[MLIP model version] extract_mlip

Inflection detection for mechanically unstable phases

For mechanically unstable phases, we follow “robust relax" process with “inflection-detection" method applied in ATAT. We provide a command robustrelax_mlip like the robustrelax_vasp in ATAT. A recommanded usage of the command is:

robustrelax_mlip -id -c=0.05 -mlip=[MLIP] -model=[MLIP model version]

which means relaxing the structure and using inflection-detection method with a criteria relaxation magnitude cutoff as 0.05. We can use it to replace the command runstruct_mlip in Section 4.11.

The inflection-detection process requires not only the accurate energies, but also the forces and stresses of the calculations. It might fail or find the wrong inflection point with poor accuracy in forces and stresses with the MLIP. To overcome this, we provide a pure metallic elements database in Supplementary Section C, with some common metallic elements in BCC, FCC, and HCP. Inflection detections are done with VASP, with the energies and vibrational entropies pre-calculated and saved in the database.

Vibrational entropy calculations

We use the fitfc module in ATAT to calculate the vibrational entropy. After generating an empty dummy vaspf.wrap file, one can do:

foreachfile endmem pwd 7D2 fitfc -si=str_relax.out -ernn=4 -ns=1 -nrr foreachfile -d 3 wait 7D2 runstruct_vasp -lu -w vaspf.wrap -nr foreachfile -d 3 wait 7D2 MLIPcalc -mlip=[MLIP] -model=[MLIP model version] foreachfile endmem pwd 7D2 fitfc -si=str_relax.out -f -frnn=1.5 foreachfile endmem pwd 7D2 robustrelax_vasp -vib

for the calculation of the vibrational entropy for each end member at high temperature limit in svib_ht, in units of Bolzmann constants.

Sometimes we might have negative frequencies, and the fitfc code aborts with the error information:

Unstable modes found. Aborting...

If you see the warning:

Warning: p... is an unstable mode.

Then the structure is certainly unstable. Otherwise, it could be an artifact of the fitting procedure. Several ways to deal with the issue:

-

Use fitfc -fu to find and check the unstable mode. It generates a file unstable.out under folder vol_0. The unstable modes are outputed in form of: u [index] [nb_atom] [kpoint] [branch] [frequency] [displacements...]. If the file only contains nb_atoms as too_large, you need to increase the -mau option. Otherwise, you can pick one of the unstable modes and do fitfc -gu=[unstable mode index] to generate the unstable mode. Run the single-point calculation with MLIPcalc in the generated subdirectory (named vol_0/p_uns_* and rerun fitfc -f -fr=.... Repeat the process until the error message disappear or a truly unstable mode is found.

-

Use a larger supercell for the calculation;

-

Decrease the -frnn;

-

If the structure is mechanically unstable, follow the steps in Section “Inflection detection for mechanically unstable phases” for inflection detection;

-

If one believe the structure is mechanically stable, use the option -fn in fitfc -si=str_relax.out -f -frnn=2 -fn to force the fitfc code to calculate the vibrational entropy.

The vibrational contribution calculations require accurate forces from the calculations. When the MLIP you use are poor in forces and stresses calculations, we recommand using the pure metallic elements database introduced in Section 4.12 and Supplementary Section C if available.

Molecular dynamics calculations for liquid phase

For the liquid phase, we use molecular dynamics to calculate the free energies at different concentrations. Use the command:

sqs2tdb -cp -sp=[Element1, Element2, ...] -l=LIQUID -lv=[Level]

to generate initial liquid “SQS" for MD calculations. With an empty dummy vasp.wrap file, in each folder, use the command:

runstruct_vasp -nr MLIPliquid -mlip=[MLIP] -model=[MLIP model version] -dT=[Temperature offset, default=50] [-LAMMPS]

It first calculates the temperature for MD, which is the linear combination of the melting points of all the elements in the structure, plus the offset temperature passing by the argument, which guarantees the final temperature is above melting point and we get a liquid structure in MD. The code performs a ternary search for the equilibrium volume and calculates the energy, or alternatively computes it using LAMMPS with the [-LAMMPS] option. A sample LAMMPS input script for MD is provided in Supplementary Section D.

Fitting into a CALPHAD model

With all the energies of SQS’s and vibrational entropies (if needed) calculated, we can use ATAT to fit the data into a CALPHAD model. For each phase, we use the command:

sqs2tdb -fit

It will generate a file named terms.in, containing the levels of interactions included in the TDB file. It is in the format:

order,level: order,level:... ...

The order is 1 for the linear combination term, 2 for binary interaction, 3 for ternary interaction, etc., and the level indicates the level of polynomials included for that order of interaction. Starting from order=1, the order,level pairs should be included in the terms.in, with the same order in each line, and separated by colons for each sublattice. For

-

order=1, we can only have level=0;

-

order=2, the binary interaction contribution to the free energy is \(\mathop{\sum }\limits_{l=0}^{L}{G}_{AB;l}{X}_{A}{X}_{B}{\left({X}_{B}-{X}_{A}\right)}^{l}\), where the L is the level of polynomial;

-

order=3,level=0 indicates a single term in form of GABCXAXBXC, while higher levels contain extra terms \({G}_{ABC;1}{X}_{A}{X}_{B}{X}_{C}\left({V}_{A}{X}_{A}+{V}_{B}{X}_{B}+{V}_{C}{X}_{C}\right)\);

-

order>3, we only have level=0.

With the terms.in file set properly, retype the command

sqs2tdb -fit [-sro]

to perform the fitting process, with the -sro optional, which includes the short-range-order contribution to the model. There would be an output file named lattice_name.tdb in the folder. After the fitting of each lattice is completed, we can combine the results of all the TDB files, together with SGTE elemental data, with a command in the base folder:

sqs2tdb -tdb [-oc]

It generates a TDB file named [ELEMENT_ELEMENT_...].tdb, which can be imported into thermodynamic packages using Calphad modeling, such as Thermo-Calc64,65, Pandat30, FactSage66, OpenCalphad67, etc. to plot phase diagrams. The [oc] option is the Open Calphad option for a more portable TDB file.

Data availability

All data used in the examples presented in this paper are openly available in the examples directory of the repository at https://github.com/dogusariturk/PhaseForge (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15730911).

Code availability

The PhaseForge code is publicly available at https://github.com/dogusariturk/PhaseForge(https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15730911), and the MaterialsFramework code is publicly available at https://github.com/dogusariturk/MaterialsFramework(https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15731044).

Change history

19 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01913-x

References

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Senkov, O., Wilks, G., Miracle, D., Chuang, C. & Liaw, P. Refractory high-entropy alloys. Intermetallics 18, 1758–1765 (2010).

Li, R., Xie, L., Wang, W. Y., Liaw, P. K. & Zhang, Y. High-throughput calculations for high-entropy alloys: a brief review. Front. Mater. 7, 290 (2020).

Lukas, H., Fries, S. G. & Sundman, B.Computational Thermodynamics: The Calphad Method (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Villars, P. Handbook of ternary alloy phase diagrams. ASM Int. 7, 8754–8755 (1995).

Zunger, A., Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353 (1990).

van de Walle, A., Sun, R., Hong, Q.-J. & Kadkhodaei, S. Software tools for high-throughput CALPHAD from first-principles data. Calphad 58, 70–81 (2017).

Samanta, S. & van de Walle, A. Software tools for integrating special quasirandom structures and the cluster variation method into the CALPHAD formalism. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 45, 1116–1129 (2024).

Zhu, S. & van de Walle, A. Computational assessment of novel predicted compounds in Ni-Re alloy system. J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 42, 315–320 (2021).

Broughton, J. & Li, X. Phase diagram of silicon by molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 35, 9120 (1987).

Bai, K. et al. Short-range ordering heredity in eutectic high entropy alloys: a new model based on pseudo-ternary eutectics. Acta Mater. 243, 118512 (2023).

Zhu, S. et al. Probing phase stability in crmonbv using cluster expansion method, CALPHAD calculations and experiments. Acta Mater. 255, 119062 (2023).

Nataraj, C., Borda, E. J. L., van de Walle, A. & Samanta, A. A systematic analysis of phase stability in refractory high entropy alloys utilizing linear and non-linear cluster expansion models. Acta Mater. 220, 117269 (2021).

Rosenbrock, C. W. et al. Machine-learned interatomic potentials for alloys and alloy phase diagrams. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 24 (2021).

Zhu, S., Sarítürk, D. & Arróyave, R. Accelerating CALPHAD-based phase diagram predictions in complex alloys using universal machine learning potentials: opportunities and challenges. Acta Mater. 286, 120747 (2025).

Van De Walle, A., Asta, M. & Ceder, G. The alloy theoretic automated toolkit: a user guide. Calphad 26, 539–553 (2002).

Yaqoob, K. & Joubert, J.-M. Experimental determination and thermodynamic modeling of the ni–re binary system. J. Solid State Chem. 196, 320–325 (2012).

Pogodin, S. & Skryabina, M. Nickel-rhenium system. Isz Sekt. Fiz. Khim Anal. 25, 81–88 (1954).

Savitskii, E., Tylkina, M. & Povarova, K. Rhenium-based alloys. Izd. Nauka Moskva 335 (1965).

Savitskii, E., Burkhanov, G., Savitskii, E. & Burkhanov, G. Alloys of refractory metals. Phys. Metal. Refractory Metals Alloys 191–234 (1970).

Neubauer, C., Mari, D. & Dunand, D. Diffusion in the nickel-rhenium system. Scr. Metall. Mater. 31, 99–104 (1994).

Saito, S., Kurokawa, K., Hayashi, S., Takashima, T. & Narita, T. Phase equilibria and tie-lined compositions in a ternary ni-al-re system at 1423 k. J. Jpn. Inst. Met. 71, 793–800 (2007).

Okamoto, H. Ni-re (nickel-rhenium). J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 33, 346–346 (2012).

Narita, S. Master’s thesis. Graduate School of Hokkaido University, as quoted in [66] and [67] (2003).

Hardcastle, C., O’Mullan, R., Arroyave, R. & Vela, B. Physics-informed Gaussian process classification for constraint-aware alloy design. Digit. Discovery. 4, 1884-1900 (2025).

Choi, W.-M. et al. A thermodynamic description of the co-cr-fe-ni-v system for high-entropy alloy design. Calphad 66, 101624 (2019).

He, F. et al. Solid solution island of the co-cr-fe-ni high entropy alloy system. Scr. Mater. 131, 42–46 (2017).

Ding, J. et al. High entropy effect on structure and properties of (Fe, Co, Ni, cr)-b amorphous alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 696, 345–352 (2017).

Bochkarev, A., Lysogorskiy, Y. & Drautz, R. Graph atomic cluster expansion for semilocal interactions beyond equivariant message passing. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021036 (2024).

Chen, S.-L. et al. The PANDAT software package and its applications. Calphad 26, 175–188 (2002).

Nishizawa, T. & Ishida, K. The Co-Ni (cbalt-nickel) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 4, 390–395 (1983).

Smith, J., Carlson, O. & Nash, P. The Ni-V (nickel- vanadium) system. Bull. Alloy Phase Diagr. 3, 342–348 (1982).

Okamoto, H. Fe-V (iron-vanadium). J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 27, 542 (2006).

Swartzendruber, L., Itkin, V. & Alcock, C. The Fe-Ni (iron-nickel) system. J. Phase Equilibria 12, 288–312 (1991).

Ghosh, G. Thermodynamic and kinetic modeling of the Cr-Ti-V system. J. Phase Equilibria 23, 310 (2002).

Byeong-Joo, L. Revision of thermodynamic descriptions of the Fe-Cr & Fe-Ni liquid phases. Calphad 17, 251–268 (1993).

Okamoto, H. Co-V (cobalt-vanadium). J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 28, 314–314 (2007).

Ohnuma, I. et al. Phase equilibria in the Fe-Co binary system. Acta Mater. 50, 379–393 (2002).

Okamoto, H. Co-Cr (cobalt-chromium). J. Phase Equilibria 24, 377–378 (2003).

van de Walle, A. Reconciling SGTE and ab initio enthalpies of the elements. Calphad 60, 1–6 (2018).

Kusne, A. G. et al. On-the-fly closed-loop materials discovery via Bayesian active learning. Nat. Commun. 11, 5966 (2020).

Ament, S. et al. Autonomous materials synthesis via hierarchical active learning of nonequilibrium phase diagrams. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg4930 (2021).

Dai, C. & Glotzer, S. C. Efficient phase diagram sampling by active learning. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 1275–1284 (2020).

Hillert, M. The compound energy formalism. J. Alloy. Compd. 320, 161–176 (2001).

Dinsdale, A. T. SGTE data for pure elements. Calphad 15, 317–425 (1991).

Larsen, A. H. et al. The atomic simulation environment-a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Melchionna, S., Ciccotti, G. & Lee Holian, B. Hoover NPT dynamics for systems varying in shape and size. Mol. Phys. 78, 533–544 (1993).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

van de Walle, A. & Ceder, G. Automating first-principles phase diagram calculations. J. Phase Equilibria 23, 348 (2002).

Van De Walle, A. Multicomponent multisublattice alloys, nonconfigurational entropy and other additions to the alloy theoretic automated toolkit. Calphad 33, 266–278 (2009).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Kadkhodaei, S., Hong, Q.-J. & Van De Walle, A. Free energy calculation of mechanically unstable but dynamically stabilized bcc titanium. Phys. Rev. B 95, 064101 (2017).

Kadkhodaei, S. & van de Walle, A. Software tools for thermodynamic calculation of mechanically unstable phases from first-principles data. Comput. Phys. Commun. 246, 106712 (2020).

Chen, H., Hong, Q.-J., Navrotsky, A. & van de Walle, A. A computational free energy reference for mechanically unstable phases. Calphad 91, 5236216 (2025).

Kikuchi, R. A theory of cooperative phenomena. Phys. Rev. 81, 988 (1951).

Morral, J. & Gupta, H. Phase boundary, zpf, and topological lines on phase diagrams. Scr. Metall. Mater. 25, 1393–1396 (1991).

Morral, J. & Gupta, H. A figure of merit for predicted phase diagrams. J. Phase Equilibria 13, 373–376 (1992).

Sundman, B., Jansson, B. & Andersson, J.-O. The thermo-calc databank system. Calphad 9, 153–190 (1985).

Andersson, J.-O., Helander, T., Höglund, L., Shi, P. & Sundman, B. Thermo-calc & DICTRA, computational tools for materials science. Calphad 26, 273–312 (2002).

Bale, C. et al. Reprint of: FactSage thermochemical software and databases, 2010-2016. Calphad 55, 1–19 (2016).

Sundman, B., Kattner, U. R., Palumbo, M. & Fries, S. G. OpenCalphad-a free thermodynamic software. Int. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 4, 1–15 (2015).

Choudhary, K. & DeCost, B. Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network for improved materials property predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 1–8 (2021).

Choudhary, K. et al. Unified graph neural network force-field for the periodic table: solid state applications. Digital Discov. 2, 346–355 (2023).

Yin, B. et al. AlphaNet: scaling up local-frame-based atomistic interatomic potential. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.07155 (2025).

Deng, B. et al. CHGNet: pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modeling. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.14231 (2023).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & E, W. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Zeng, J. et al. DeePMD-kit v2: a software package for deep potential models. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 054801 (2023).

Zeng, J. et al. DeePMD-kit v3: a multiple-backend framework for machine learning potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 21, 9, 4375–4385 (2025)

Barroso-Luque, L. et al. Open materials 2024 (OMat24) inorganic materials dataset and models. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.12771 (2024).

Fu, X. et al. Learning smooth and expressive interatomic potentials for physical property prediction. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12147 (2025).

Xie, F., Lu, T., Meng, S. & Liu, M. GPTFF: A high-accuracy out-of-the-box universal AI force field for arbitrary inorganic materials. Sci. Bull. 69, 3525–3532 (2024).

Yan, K. et al. A materials foundation model via hybrid invariant-equivariant architectures. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.05771 (2025).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Batatia, I. et al. A foundation model for atomistic materials chemistry. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.00096 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. MatterSim: a deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.04967 (2024).

Haghighatlari, M. et al. NewtonNet: a Newtonian message passing network for deep learning of interatomic potentials and forces. Digital Discov. 1, 333–343 (2022).

Neumann, M. et al. Orb: a fast, scalable neural network potential. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.22570 (2024).

Rhodes, B. et al. Orb-v3: atomistic simulation at scale. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.06231 (2025).

Mazitov, A. et al. PET-MAD, a universal interatomic potential for advanced materials modeling https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.14118 (2025).

IBM Research. pos-egnn: position-based equivariant graph neural network for chemistry and materials. https://huggingface.co/ibm-research/materials.pos-egnn (2025).

Park, Y., Kim, J., Hwang, S. & Han, S. Scalable parallel algorithm for graph neural network interatomic potentials in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 4857–4868 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Data-efficient multifidelity training for high-fidelity machine learning interatomic potentials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 1042–1054 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation through Grant No. 2119103. We also acknowledge the support from the Army Research Office through Grant No. W911NF-22-2-0117. Calculations were carried out at Texas A&M High-Performance Research Computing (HPRC) Facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. wrote the main manuscript, developed the PhaseForge code, and prepared the examples and all the figures. D.S. wrote the subsection Incorporate MLIP within MaterialsFramework, Supplementary Section A and D, developed the Materials framework code, assisted in preparing the examples. R.A. supervised the project, contributed to the conceptual development, and provided guidance on technical details. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, S., Sarıtürk, D. & Arróyave, R. Machine learning potentials for alloys: a detailed workflow to predict phase diagrams and benchmark accuracy. npj Comput Mater 11, 340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01814-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01814-z