Abstract

Machine learning (ML) offers considerable promise for the design of new molecules and materials. In real-world applications, the design problem is often domain-specific, and suffers from insufficient data, particularly labeled data, for ML training. In this study, we report a data-efficient, deep-learning framework for molecular discovery that integrates a coarse-grained functional-group representation with a self-attention mechanism to capture intricate chemical interactions. Our approach exploits group-contribution concepts to create a graph-based intermediate representation of molecules, serving as a low-dimensional embedding that substantially reduces the data demands typically required for training. Using a self-attention mechanism to learn the subtle but highly relevant chemical context of functional groups, the method proposed here consistently outperforms existing approaches for predictions of multiple thermophysical properties. In a case study focused on adhesive polymer monomers, we train on a limited dataset comprising only 6,000 unlabeled and 600 labeled monomers. The resulting chemistry prediction model achieves over 92% accuracy in forecasting properties directly from SMILES strings, exceeding the performance of current state-of-the-art techniques. Furthermore, the latent molecular embedding is invertible, enabling the design pipeline to automatically generate new monomers from the learned chemical subspace. We illustrate this functionality by targeting several properties, including high and low glass transition temperatures (Tg), and demonstrate that our model can identify new candidates with values that surpass those in the training set. The ease with which the proposed framework navigates both chemical diversity and data scarcity offers a promising route to accelerate and broaden the search for functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular design is at the core of modern science and engineering1, with wide applications that range from the development of new drugs2,3,4,5,6 to the discovery of new functional and sustainable materials7,8,9,10,11. Although considerable progress has been made over decades of sustained effort, it continues to be a daunting endeavor. The construction of a molecule with specific target properties involves a combinatorial problem that consists of selecting the correct atoms and connecting them in an appropriate manner. The available chemical space for molecular design grows exponentially with the molecular size12. However, relevant candidates only populate a very small portion of that space. To identify optimal choices, two crucial questions must be addressed: the relationship between different molecular structures and the dependence of molecular properties on them. This presents the inherent challenge of exploring chemical space, further exacerbating the curse of dimensionality that pervades molecular design.

Molecular embedding13,14,15,16 can facilitate the navigation of chemical space. By evaluating a selection of molecular features, we can encode a molecule M by its corresponding feature vector h, denoted as:

This mapping creates a mathematical realization of the chemical space, where the differences between molecules can be quantified via the distance ∥hi − hj∥, and molecular properties can be inferred from a function y = f (h). A good molecular embedding should satisfy the two following requirements. First, it must be chemically meaningful. Molecules with similar chemistry should be arranged close to each other, so that primarily relevant regions can be explored. Second, it should be informative. The feature vector should contain key information for the prediction of molecular properties, which in turn can provide guidance for the optimization of molecular structure.

Molecular fingerprints17,18 are often used in traditional cheminformatics. They are prescribed descriptors that record the statistics of the different chemical groups in a molecule. This type of embedding organizes molecules in chemical space based on their local structures, which play a key role in determining molecular properties. Hence, if a new molecule with a new set of properties was sought, new candidates could be sampled from existing molecules simply by replacing chemical groups and then screening the proposed constructs using chemistry prediction models, such as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSARs)19,20. However, such an approach is limited to the exploration of the space in the near vicinity of individual known molecules, which is what local modifications allow. Furthermore, the quality of the resulting designs can be compromised by artifacts resulting from the interplay between chemical groups, especially their interconnectivity, which is disregarded by molecular fingerprints.

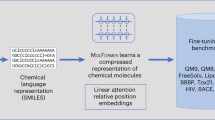

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) have enabled the extraction of molecular embedding from data21,22,23,24,25. A widely adopted ML scheme relies on an autoencoder26,27 architecture, where an encoder maps molecules to a continuous latent space, and a consecutive decoder tries to reconstruct them28,29. The schematic in Fig. 1 provides a simple description of the key concepts.

After being trained, an autoencoder can produce latent vectors that represent the global structure of a molecule. This embedding enables for coherent nonlocal modifications of molecules. Due to the continuity of the latent space, interpolations can be made between different molecules to acquire combined properties, and directed optimization can be performed through gradient descent. However, since this embedding is primarily designed for molecular reconstruction, it does not necessarily correlate well with molecular properties. Molecular reconstruction focuses on the connectivity of atoms or chemical groups within a molecule, whereas molecular chemistry is also influenced by the interactions between different molecules. To enhance such correlations, the autoencoder should be jointly trained with an additional chemistry prediction model that maps latent vectors onto properties of interest. Doing so would require a large amount of labeled data, which is typically unavailable. In real-world applications, the design problem is often domain-specific; there is a preferred class of molecules, and the subset for which properties have been measured or are available is very limited.

In this work, we introduce a machine-learning pipeline for domain-specific molecular design, anchored by a functional-group-based coarse-graining strategy. The pipeline consists of a hierarchical coarse-grained graph autoencoder to generate relevant candidates, and a chemistry prediction model to efficiently screen the proposed structures and select optimal choices. A key innovation here is the integration of a self-attention mechanism, inspired by natural language processing, where tokens in a sequence can have long-range dependencies, into the realm of macromolecules, whose functional groups exhibit similarly intricate spatial and chemical interactions. We anticipate broad applicability of this framework wherever faithful molecular generation is essential, from pharmaceutical discovery, where scaffold and functional-group placements critically affect bioactivity, to materials science, where chain-like and branched architectures frequently govern mechanical and thermal properties. Crucially, by focusing on coarse graining based on functional groups, our hierarchical approach remains data-efficient, allowing robust design and analysis even under data-scarce conditions.

The encoder \({\mathcal{E}}\) maps discrete molecules to a continuous latent space, capturing global structural and chemical features. The decoder \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{-1}\) reconstructs the molecular graph from the latent space. This latent embedding enables the prediction of molecular properties via a learned function f, and gradients ∇ f can be exploited for property-driven molecular optimization. The continuity of the latent space allows for smooth interpolations and nonlocal molecular transformations.

Results

Coarse-grained graph autoencoder

Depending on the choice of molecular representation, there are two popular ways to create an autoencoder. By representing a molecule as a SMILES30 string, we can treat molecular embedding as a natural language processing problem and build an autoencoder using a sequence model28. However, because of the one-dimensional nature of a text string, special tricks are always needed to account for the three-dimensional topology of a molecule, especially for features like rings, branches, and stereoisomerism. This poses unnecessary obstacles to the application of string-based autoencoders. Alternatively, by representing a molecule as a graph of atoms, we can naturally preserve molecular topology and embed molecules using graph neural networks. Several autoencoder frameworks29,31,32 have been developed in this context. While these atom-graph-based autoencoders have established important foundations, they face well-recognized challenges: low chemical validity rates due to unconstrained decoding, sensitivity to graph isomorphism, and scalability issues as molecular size increases33.

The construction of molecules using structural motifs provides an effective means for the design of large molecules having a complex topology. Researchers have identified ~100 functional groups, which are local structures that underlie the key chemical properties of molecules. Notably, most synthesizable molecules can be deconstructed into these structural motifs. Thus, this small set of common functional groups (as shown in Fig. 2a) can serve as a standard vocabulary for molecular design. Compared with atoms, they enable a coarse-grained and chemically meaningful representation of a molecule, which simplifies the design process.

By identifying “elementary" functional groups, we can construct a hierarchical representation of a molecule, with an atom graph at the finer level and a motif graph at the coarser level. a Vocabulary of functional groups. The vocabulary is composed of 50 key chemical groups selected on the basis of group contribution theory, as well as all the ring structures that appear in the known molecules of interest. b Coarse-grained graph autoencoder. Graph neural networks are applied to both the atom and motif graphs to encode the local environment of individual nodes, which contains the nodes themselves and their neighbors. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) is introduced between two graphs to integrate the encoded information at the atom level into functional groups at the motif level. A variational connection is added to ensure the continuity of the latent space. Note that the decoder operates in an autoregressive manner. It reconstructs the molecule by iteratively generating a new motif and connecting it to the partial molecule built thus far. At each step, it needs an encoder to refresh the embedding of atoms and functional groups based on the current molecular structure. c Chemically meaningful embeddings from our autoencoder. This visualization demonstrates the capability of our autoencoder to categorize 6000 adhesive monomers into four clusters corresponding to their chemical classes: Methyl Methacrylate, Methacrylamide, Methyl Acrylate, and Acrylamide. For illustrative purposes, we use t-SNE to map ten-dimensional embeddings into a two-dimensional space. Even though the types of monomers were not provided during training, our autoencoder can automatically create embeddings that show clear separations based on inherent chemical properties. d Invertible embeddings across different representations. A comparison of our proposed functional-group-based autoencoder to SMILES- and atom-level graph-based approaches shows that molecules used in domain-specific materials often feature extended chains and fewer rings compared to small-molecule drugs. While our coarse-grained model can maintain a 95% reconstruction accuracy under these conditions, SMILES and atom-graph methods achieve around 60% or lower.

Expanding upon recent advances in hierarchical encoder-decoder34 architectures for molecular graphs, we constructed our functional-group-based autoencoder around a multi-level representation of molecular structures. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, a molecule M can be represented with two levels of description: at the fine level, it forms an atom graph \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)\) composed of atoms ai and bonds bij; at the coarse level, it is also a motif graph \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)\) composed of functional groups Fu and their interconnectivity Euv; in between is the hierarchical mapping from each functional group Fu towards the corresponding atomic subgraph \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})\), which is easily accessible via the cheminformatics software RDKit35. Details are summarized below: (Throughout the paper, superscripts and subscripts are used to denote the hierarchical level and the node index within a graph, respectively.)

Coarse-graining graph representation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Motif level | \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)=\left({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M),{{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)\right)\) | \({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)=\left\{{F}_{u}\,| \,{F}_{u}\in M\right\}\) | \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)=\left\{{E}_{uv}\,| \,{E}_{uv}\in M\right\}\) |

Motif → Atom | \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})=\left({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u}),{{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})\right)\) | \({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})=\left\{{a}_{i}\,| \,{a}_{i}\in {F}_{u}\right\}\) | \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})=\left\{{b}_{ij}\,| \,{b}_{ij}\in {F}_{u}\right\}\) |

Atom level | \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)=\left({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M),{{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)\right)\) | \({{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)=\left\{{a}_{i}\,| \,{a}_{i}\in M\right\}\) | \({{\mathcal{E}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)=\left\{{b}_{ij}\,| \,{b}_{ij}\in M\right\}\) |

Molecular embedding is introduced by treating the generation of molecules as a Bayesian inference:

P(hm) is a prior distribution of the embedding hm. In the following text, we will explain in more detail how to build an encoder to estimate the posterior distribution P(hm∣M) and a decoder to derive the conditional probability of reconstructing the same molecule P(M∣hm).

The encoder analyzes a molecule from the bottom up. First, a message-passing network (MPN) is used to encode the atom graph:

Here the features of individual atoms and bonds, for instance, \({{\bf{x}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}=\) (atom type, valence, formal charge) and \({{\bf{x}}}_{ij}^{{\rm{a}}}=\) (bond type, stereo-chemistry) are taken as inputs and shared with their neighbors through the message passing mechanism on the graph \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}\). Then the embeddings of the atoms and bonds are derived to encode their local environment, denoted as \({{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}\) and \({{\bf{h}}}_{ij}^{{\rm{a}}}\), which include their own properties and those of their neighbors, as well as the way in which they connect with each other. Second, we assemble the feature vectors of functional groups using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP):

which consists of the type of embedding of the functional group x(Fu) and the graph embedding of its atomic components \(\left\{{{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}\,| \,i\in {{\mathcal{V}}}^{{\rm{a}}}({F}_{u})\right\}\). Third, we employ another MPN to encode the motif graph:

where \({{\bf{h}}}_{u}^{{\rm{f}}}\) and \({{\bf{h}}}_{uv}^{{\rm{f}}}\) are the embeddings of individual functional groups. Lastly, a molecular embedding hm is sampled in a probabilistic manner:

where \({{\bf{h}}}_{0}^{{\rm{f}}}\) denotes the embedding of the root motif, a functional-group node assigned during graph construction. This assignment is deterministic for each molecule, ensuring reproducibility, but varies across molecules depending on their graph structure. Because the encoder is trained end-to-end, the latent distribution does not depend on the specific identity of the root motif, thereby avoiding systematic bias. The functions μ( ⋅ ) and σ( ⋅ ) map \({{\bf{h}}}_{0}^{{\rm{f}}}\) to the mean and log-variance of the Gaussian distribution, and the reparameterization trick enables a continuous, differentiable latent space.

Once molecular embedding is achieved, the decoder can reconstruct the same molecule motif-by-motif. We model this as an auto-regressive progress by factorizing the conditional probability in Eq. (2) into:

where M≤u−1 = ⋃v≤u−1Fv and M≤u = ⋃v≤uFv denote the molecule before and after adding functional group Fu, respectively. At each step, the decoder only needs to predict which functional group Fu to choose and which bond bij to form for its attachment onto the partial molecule M≤u−1:

To quantify the condition, we apply the same encoder to analyze M≤u−1. Assuming that the useful information on the partial molecule for the prediction of the next motif is localized near its growing end, we use the embedding of the last motif \({{\bf{h}}}_{u-1}^{{\rm{f}}}\) to represent M≤u−1. The probability of choosing functional group Fu as the next motif can then be estimated as

Similarly, for the prediction of the attachment bond, the atom embeddings \(\left\{{{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}\,| \,{a}_{i}\in {F}_{u}\right\}\) and \(\left\{{{\bf{h}}}_{j}^{{\rm{a}}}\,| \,{a}_{j}\in {F}_{u-1}\right\}\) are used to represent the condition in both Fu and M≤u−1. Then we estimate the probability of choosing bond bij as

Since Fu is not yet attached to M≤u−1, here the embedding \({{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}\) is obtained by applying the encoder to Fu alone.

We train our model by minimizing its evidence lower bound (ELBO), a common loss function for a variational autoencoder. It contains two parts \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{ELBO}}}={{\mathcal{L}}}_{1}+\lambda {{\mathcal{L}}}_{2}\), namely a reconstruction loss that quantifies the cross-entropy between the encoder and the decoder

and a regularizer that measures the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the prior and posterior distributions of molecular embedding to avoid overfitting

where we postulate the prior distribution \(P({{\bf{h}}}^{{\rm{m}}})={\mathcal{N}}({\bf{0}},\,{\bf{I}})\), and where the probability estimates by the encoder and the decoder, P(hm∣M) and P(M∣ hm), are computed using Eqs. (6)–(7).

To highlight the capability of handling domain-specific data, we tested the autoencoder on acrylate-based adhesive materials obtained from experiments. This dataset comprises 6,000 known monomers drawn from four different monomer classes. Because the autoencoder is an unsupervised method, no molecular properties or labels are required. Nonetheless, the t-SNE projection of the learned latent space \({\mathcal{S}}({{\bf{h}}}^{{\rm{m}}})\) presents a clear clustering of monomers according to their chemical types, as shown in Fig. 2c. Such automatic grouping of monomers underscores the practical utility of our model in guiding targeted molecule design for industrial adhesive applications.

Besides furnishing a chemically meaningful representation, our molecular embedding also remains fully invertible–a vital feature for generative tasks. Specifically, Using the embedding of a molecule produced by the encoder, the decoder can reconstruct the same molecule with an accuracy of ~95%, substantially surpassing string-based and atom-graph-based autoencoders28,36 trained under comparable conditions (Table S1). Although previous studies29,34 reported reasonable reconstruction rates on broader chemical libraries, those architectures were tailored to relatively diverse molecules in which rings are prevalent. Here, in contrast, we seek to capture the richer chain- and branch-dominated chemistry of polymeric adhesives, where ring motifs are relatively scarce. In such data-limited domain-specific settings, we observed that traditional decomposition schemes, which often mine ring and branch substructures based purely on the frequency of occurrence, induce an unbalanced motif vocabulary heavily biased toward rings. This bias not only hampers the model’s ability to reconstruct chain-like polymers accurately, but also leads to less chemically interpretable embeddings as shown in Fig. S1.

Our approach addresses this bottleneck by deliberately constructing a motif vocabulary from functional groups, building on the established principles of group contribution. This strategy provides two main advantages. First, it limits our dictionary to functional groups that comprehensively span typical polymeric architectures, mitigating the overfitting to ring motifs. Second, by focusing on functional groups rather than purely structural motifs, the model inherently encodes information relevant to reactivity and physical properties, resulting in embeddings that more closely align with chemical intuition. The net effect is markedly superior reconstruction fidelity, particularly for the class of polymeric monomers under study. Such a design aligns well with the aims of a data-scarce, domain-focused molecular design, wherein the capture of specialized chemistries can be more important than achieving broad coverage of all possible small-molecule scaffolds. Consequently, the strong reconstruction accuracy reflects the capacity of our model to handle polymer-like structures with minimal data, highlighting the promise of coarse graining based on functional groups for improved generative performance.

Attention-aided chemistry prediction model

Our autoencoder imposes a relationship between different molecular structures by mapping them into a continuous latent space, where they are organized in a chemically meaningful manner. This allows for efficient sampling of chemically relevant candidates. To achieve directed design, an efficient approach is still needed to evaluate the candidate properties. Although high-throughput experiments or simulations can consider hundreds of molecular species at a reasonable cost, they are limited in terms of scalability. To address this challenge, we propose a chemistry prediction model capable of directly deriving thermophysical properties from molecular structures by using the self-attention mechanism.

The model is built on the same coarse-grained graph representation of a molecule, shown in Fig. 3a. Instead of being a simple readout of the molecular embedding, it analyzes the embedding of individual atoms and functional groups. Compared with the global structure of a molecule, the variation of those local structures is much more constrained. Therefore, training a regression model on the latter is more data-efficient. This is particularly useful for domain-specific design, where labeled data is limited.

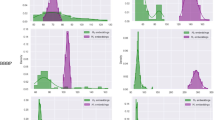

a Chemistry-oriented molecular embedding. Instead of using the latent vector for molecular reconstruction, we develop another molecular embedding focused on chemical properties. It has the same architecture as the encoder mentioned above. The key difference lies in the use of global pooling to reduce graph size and extract molecular embedding with fixed length, rather than using the embedding of the root motif. Two types of pooling are employed here. A direct graph pooling with sigmoid rectification is used to summarize the contributions of individual nodes. A pooling layer with a self-attention mechanism is also used to summarize the contributions of node-node interactions. The chemistry-oriented molecule embedding is the concatenation of individual and interaction embeddings at both the atom and motif levels. We can then use the final embedding to predict molecular properties of interest. b Prediction performance. We apply this model to learn the dependence of monomer properties on their molecular structures. Six properties relevant to the design of adhesive materials are considered and obtained using automated molecular dynamics simulations. The model is trained on 450 labeled monomers (yellow dots) and tested on another, unseen 150 monomers (other colored dots). Except for glass transition temperature, all other properties can be predicted with high accuracy R2 > 0.92.

We first estimate the contributions of individual atoms and functional groups to molecular properties, by applying the following equation to the corresponding level of the graph hierarchy:

where \(\hat{{\bf{c}}}({{\bf{h}}}_{i})\) represents the contribution of node i alone, while \(\tilde{{\bf{c}}}({{\bf{h}}}_{i},{{\bf{h}}}_{j})\) represents the contribution of the interaction between node i and node j that can be weighted by a learnable coefficient, aij. Nodes can refer to either atoms or functional groups depending on the level of the graph, with \({{\bf{h}}}_{i}={{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{a}}}\,{\rm{or}}\,{{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{{\rm{f}}}\).

In bulk materials, the likelihood of two local structures interacting with each other is determined by their affinity. To capture this relationship, we introduce the weight coefficient, aij, defined by using the multi-head attention mechanism37:

The attention weights aij are computed using the query, key, and value projections derived from the node representation hi. In this context, the query q(hi) represents the features that node i requests from its interaction counterparts, while the key k(hj) represents the features that node j possesses and can match. The dimension of the keys is denoted by dk. The affinity score between nodes i and j is obtained by performing a dot product of their characteristics, which is then scaled by \(1/\sqrt{{d}_{k}}\) to stabilize the gradients during training. This scaled dot-product is transformed into attention by applying the softmax function to normalize the influence of each interaction. Finally, the resulting attention weight aij can be interpreted as the probability of node i interacting with node j, taking into account all other nodes in the graph.

We can then derive the molecular properties from the contributions of individual atoms and functional groups, denoted as ca and cf in the equation below:

Here, we use a graph pooling operation with a weighted sum to generate chemical embeddings for the same molecule at both the atom and motif levels, represented by the two expressions enclosed in parentheses. The weights, σ( ⋅ ) and ϕ( ⋅ ), which are the sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent functions respectively, act as gating mechanisms. These functions evaluate the significance of a local structure for the molecular properties of interest. Additionally, we incorporate an MLP structure to introduce more nonlinearity and enhance the model’s expressivity for regression. This improves the model’s ability to capture complex relationships and predict molecular properties more accurately.

Although our model is inspired by the group contribution theory, it goes beyond it. First, instead of disregarding the interconnectivity of local structures, it accounts for the influence of neighboring environments on individual atoms and functional groups, by taking their graph embeddings as input. This is particularly important for properties such as the partial charge of an atom and ionization of a functional group, which vary significantly with the local environment. Second, our model is more expressive. The contribution analysis of local structures by Eq. (13)–(14) does not rely on a simple quadratic expansion. Instead, q( ⋅ ), k( ⋅ ), \(\hat{{\bf{c}}}(\cdot )\) and \(\tilde{{\bf{c}}}(\cdot )\) are all modeled by neural networks, providing the capability to represent contributions up to any form of two-body interactions. Third, the self-attention mechanism in our design allows for non-reciprocity in the interaction, meaning that aij ≠ aji. This avoids the need to construct a non-reciprocal interaction energy Uij ≠ Uji, which is often used in models such as the UNIFAC method, but is difficult to justify from the perspective of physical interactions.

To evaluate the performance of our model, we first validate it on the standard QM9 dataset38, which contains ~130,000 molecules labeled with quantum-chemical properties. Our framework demonstrates outstanding data efficiency: when trained on only 5% of the dataset (6,000 molecules), it achieves R2 ≈ 0.97 in predicting HOMO and LUMO energies (Fig. S2). This performance, obtained with 6k samples, is comparable to or better than baseline models trained on over 100k samples39,40. Beyond frontier orbital energies, we further benchmarked the model on additional QM9 targets–including isotropic polarizability, electronic spatial extent, and heat capacity at 298 K–and consistently obtained high predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.98-0.99; Fig. S3). These results confirm both the robustness and generality of our functional-group-based representation, even under data-limited conditions.

To test our model in domain-specific applications, we evaluated a dataset of 600 monomer species relevant to adhesive polymeric materials. For each monomer, thermophysical properties were determined from all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, including cohesive energy (Ecoh), heat of vaporization (ΔHvap), isothermal compressibility (β), bulk density (ρ), radius of gyration (Rg), and glass transition temperature (Tg). We trained the model on 450 randomly selected monomers and tested on the remaining ones. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, the model achieves high predictive accuracy across nearly all properties, with R2 values above 0.92. For Tg, the accuracy remains significant but lower than for other properties, reflecting the intrinsic difficulty of generating reliable Tg labels from simulations.

To further probe the design of our architecture and verify the contribution of key component, we conducted ablation studies using Ecoh as a representative property (Figs. S4–S5). Removing the attention mechanism reduces the predictive accuracy, indicating that attention improves the model’s ability to emphasize chemically important motifs and higher-order interactions. Excluding atom-level contributions results in a further decrease in performance, demonstrating that fine-grained atomic detail is indispensable for capturing local polarity, bonding environments, and substituent effects. Together, these results confirm that both motif-level and atom-level information, combined with attention-based weighting, are critical to achieving state-of-the-art accuracy.

While our model performs strongly on single-property prediction, polymer design often requires optimizing multiple thermophysical properties simultaneously. This task is challenging because different properties, such as cohesive energy and glass transition temperature, are governed by distinct molecular factors and are rarely modeled together in existing approaches. To test this capability, we trained a multi-property model to predict both Ecoh and Tg jointly. As shown in Fig. S6, the model maintains high accuracy (R2 = 0.90 for Ecoh and R2 = 0.84 for Tg), with only a modest decrease compared to single-property models.> These results demonstrate that the hierarchical representation is sufficiently expressive to capture distinct yet correlated molecular determinants governing different physical targets. This capability is particularly important for real-world polymer design, where simultaneous control of multiple properties is essential. The ability to extend seamlessly from single- to multi-property prediction underscores the framework’s robustness and positions it as a practical tool for multi-objective molecular discovery.

Finally, we analyzed prediction robustness for Tg, the most challenging property in our dataset. As shown in Fig. S7, the RMSE of model predictions is comparable to the uncertainty of replicate MD simulations, indicating that the main limitation arises from the intrinsic noise in the training data rather than the model itself. This conclusion is further supported by variability analysis across five random train/test splits (Table S2), where we observe stable performance. Together, these results highlight the reliability of the framework and its suitability for practical molecular design tasks in polymeric materials.

Automated pipeline for molecular design

Our chemistry prediction model can process up to 104 molecules in about an hour, producing property estimates that closely match those of the actual atomistic simulations. This speed and accuracy facilitate broad and cost-effective high-throughput screening across extensive molecular databases. Using the model as an initial filter to pinpoint promising candidates, we can then rely on MD simulations to further refine these selections (Fig. 4a). Here, as a case study, we demonstrate the generative power of the model by discovering new monomers with a target glass transition temperature (Tg), a cornerstone of polymer physics that governs whether a polymer behaves as a rigid solid or as a flexible material. Despite its importance for mechanical performance and processing, Tg remains notoriously difficult to predict due to the intricate interplay of molecular interactions, chain conformation, and packing or free volume considerations; designing polymers with a prescribed Tg is even more challenging, as there is no simple structure-property rule. Our pipeline addresses this gap by learning the underlying molecular chemistry, achieving high predictive accuracy, and enabling targeted molecular design.

a We integrate a hierarchical graph autoencoder with a self-attention-based chemistry prediction model to form an autonomous pipeline. The autoencoder employs a coarse-grained functional-group vocabulary to generate chemically valid and structurally diverse candidates, while the chemistry model screens these new molecules based on predicted properties. This division of roles reduces data requirements and increases design flexibility, enabling the pipeline to selectively propose novel compounds aligned with target performance criteria. b As a proof of concept, we apply this pipeline to optimize the glass transition temperature (Tg). The successful identification of new molecules with Tg values beyond the limits of the training data demonstrates the pipeline’s potential for extrapolation and highlights its effectiveness in guiding data-efficient molecular discovery.

Central to our strategy is a latent-space generative model, which explores new polymer architectures beyond the training database. To expand the molecular search space, we sample molecular embeddings from the prior distribution \(P({{\bf{h}}}^{{\rm{m}}})={\mathcal{N}}({\bf{0}},{\bf{I}})\). Concretely, we draw random vectors from this standard normal distribution and feed them into the decoder, which converts these latent representations into valid molecular structures biased toward desired property ranges. To highlight the scope of this generative capability, in this fully automated pipeline (Fig. 4a), we restricted the chemical building blocks to the acrylate functionalities and sampled 50,000 unique candidates not present in the original database, well above simple enumeration of known compounds. Instead of a brute-force approach, the latent-space model systematically navigates chemical space in a manner that favors valid, nonduplicative structures and spans a broad range, rather than merely generating random permutations.

We next applied our chemistry-prediction model to all 50,000 generated acrylates, finding that the predicted Tg values spanned and extended beyond the range of the training set. This broad exploration highlights that the model does not rely on random ‘lucky’ hits; rather, it learns molecular motifs associated with Tg. After using our property predictor to screen for particularly high or low Tg values, we selected 100 representative candidates for validation via MD simulations. The “Screening" box in Fig. 4a illustrates the screening workflow, in which the newly generated structures pass through our chemistry prediction model, and then MD simulations validate a subset of particularly high- or low Tg candidates. As shown in Fig. 4b, the predicted Tg values for these candidates are in close agreement with the simulated results, demonstrating our model’s accuracy. For clearer visualization, we randomly selected half of both the training and test datasets to display, along with 20 random examples from the 100 newly generated molecules that were validated by simulation. In particular, some of the newly generated molecules exhibit Tg that exceed the low and high limits of the training set. This indicates that the generative model can explore regions of chemical space beyond those directly represented in the original data, rather than merely reproducing existing structures. Moreover, the Screening step in Fig. 4a reveals that these new candidates feature diverse molecular backbones and functional groups that would be difficult to conceive based on chemical intuition alone. This underscores how large-scale sampling and rapid property evaluation can facilitate the discovery of promising novel designs in polymer science.

So far, Tg has served as a critical proof-of-concept target: its sensitivity to both local chemical environments and long-range relaxation processes poses a stringent test for any materials-design model. Importantly, our approach is not confined to this single property and can be readily applied to others. As an other example (see Supplementary Information), we used the same pipeline to design materials with high cohesive energy density, as illustrated in Fig. S8, where newly generated candidates outperformed those found in the original database. Together, these two cases demonstrate the model’s ability to autonomously explore chemical space and discover promising structures beyond the training distribution. Building on this foundation, our framework naturally generalizes to multi-property optimization, enabling the concurrent pursuit of multiple requirements vital to industrial practice.>Since the predictor has already demonstrated reliable joint accuracy for \({{E}_{\rm{coh}}}\) and \({{T}_{g}}\), the same generative pipeline can be adapted to propose molecules that optimize both properties simultaneously. This extension transforms the current workflow into a scalable, multi-objective design engine. By systematically integrating generative exploration, high-throughput property prediction, and targeted simulation validation, this foundation provides a robust strategy for AI-guided molecular discovery and paves the way for accelerated innovation in materials design.

Discussion

Our approach to molecular design is based on the emerging paradigm of digitizing the chemical space and then directing molecular generation through property prediction models. However, it deviates from conventional strategies that rely on a single embedding vector to represent an entire molecule in an end-to-end framework. Instead, a hierarchical scheme is adopted in which local atomic details, coarse-grained functional groups, and global molecular embeddings each play distinct roles. This architecture not only mitigates the information loss often associated with autoencoders, but also ensures that relevant chemical features are extracted and leveraged when needed, akin to the multiscale design principles used in UNet-like image processing models41.

In our pipeline, the decoder incrementally assembles new molecules by predicting structural motifs and the specific bonds connecting them, guided by both local embeddings (atoms and functional groups) and a global molecular embedding that orchestrates the overall design. The subsequent screening employs a self-attention-based chemistry prediction model, which capitalizes on the same hierarchical representations to evaluate molecular properties. By shifting the main burden of chemical interpretation to local embeddings, the framework remains data efficient: The task of learning chemically meaningful representations at the atomic or group level is considerably more tractable than requiring a single global embedding to capture every subtlety of an entire molecule. This design choice proved to be critical to achieving high accuracy with limited training data.

A key innovation underlying this efficiency is our use of functional groups as a coarse-grained vocabulary for both generation and prediction. The group contribution theory approach identifies < 100 groups that recapitulate the most relevant chemistries, offering three significant advantages. First, it confines the combinatorial explosion of possible motifs, avoiding large data-biased dictionaries. Second, it delegates atom-level connectivity to established cheminformatics toolkits such as RDKit35, alleviating the need for the autoencoder to learn this low-level connectivity from scratch. Finally, we embed these functional groups into a self-attention model that unites domain-specific chemical insights with the flexibility of modern neural networks. As a result, the chemistry prediction model achieves near-simulation-level accuracy while being trained on only a few hundred labeled molecules.

Our demonstration of targeted polymer design through this hierarchical framework showcases its potential to guide molecular discovery efficiently, even in sparse-data regimes. While the glass transition temperature served as a stringent proof-of-concept target, we also demonstrated successful generative design for other properties. Moreover, we have shown that our model can be naturally extended to optimize multiple properties concurrently. In this way, the synergy of coarse-grained functional groups and a self-attention-based architecture can be broadly harnessed for designing biomolecules, polymeric materials, and other hybrid chemical systems. We anticipate that the principles detailed in this work will serve as a useful foundation for the community to build ever more sophisticated machine learning pipelines that illuminate vast expanses of previously unexplored chemical space and drive rapid innovation in materials science.

Methods

Our method consists of three components: a coarse-grained graph autoencoder for latent molecular representation, an attention-aided model for property prediction, and an automated pipeline for functional-group-driven molecular design. Together, they enable interpretable and controllable generation of valid molecular structures from coarse motifs.

Model architecture

Molecular Representation and Functional Group Encoding: Molecules M are represented as atom-level graphs \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{a}}}(M)\), where nodes correspond to atoms with features such as type, valence, and formal charge, and edges represent chemical bonds. Functional groups were identified and grouped hierarchically into coarse-grained graphs \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{f}}}(M)\), where nodes correspond to functional groups and meta-bonds denote inter-group connectivity. Ring systems (e.g., benzene, pyridine, substituted aromatics) are treated as self-contained motifs within the functional-group vocabulary, ensuring that aromaticity and conjugation are preserved consistently rather than being fragmented across smaller units.

Atom embeddings \(\{{{\bf{h}}}_{i}^{a}\}\) and bond embeddings \(\{{{\bf{h}}}_{ij}^{a}\}\) are learned through a message-passing network (MPN) as in Eq. (3). Functional group embeddings are then constructed via aggregation of atom-level features followed by a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), as in Eq. (4). These are subsequently processed by a second MPN to encode the motif-level graph \({{\mathcal{G}}}^{{\rm{f}}}\), as in Eq. (5).

Coarse-Grained Graph Autoencoder: We formulate molecular generation as variational inference over a latent embedding hm, with the generative model expressed as

as in Eq. (2). The encoder produces a posterior distribution P(hm∣M) from the final graph representation, approximated as a normal distribution over \({{\bf{h}}}_{0}^{{\rm{f}}}\) in Eq. (6). The decoder reconstructs molecules autoregressively by adding functional groups Fu to a partial graph M≤u−1, following Eqs. (7)–(10).

The choice of the next functional group is predicted by:

as in Eq. (9), while the attachment bond bij is selected using atom-level features in Eq. (10). The model is trained by minimizing the ELBO:

with \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{1}\) the reconstruction cross-entropy (Eq. 11) and \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{2}\) the KL divergence regularizer (Eq. 12).

Attention-Aided Property Prediction: To enable property-guided molecular design, we implemented an auxiliary prediction head over hm. A multi-head attention mechanism aggregates context from functional group embeddings, followed by global pooling and regression. This module predicts molecular properties such as HOMO-LUMO gaps and is trained jointly with the generative pipeline in a multi-task setting.

Automated Pipeline for Molecular Design: We constructed an automated pipeline that integrates (1) functional group extraction, (2) coarse-grained graph construction, (3) latent encoding, (4) functional group-wise generation, and (5) optional property conditioning. This setup allows both latent sampling and gradient-based optimization in embedding space to steer generation toward property targets.

Data sources

We used the publicly available QM9 dataset, which consists of ~134,000 small organic molecules with DFT-optimized geometries and associated quantum chemical properties. For domain-specific tasks, we additionally adopted a dataset consistent with prior work42. Molecules were preprocessed using RDKit to ensure valency consistency and canonical SMILES formatting.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using GROMACS 2022 with the OPLS-AA force field. Simulation protocols and parameters largely followed previous studies42,43. Each system was first energy-minimized to remove steric clashes and ensure stable starting configurations. The minimized structures were then equilibrated in the NPT ensemble at 250 K and 1 bar for 10 ns with a 1 fs timestep, employing a Langevin thermostat (friction constant = 1 ps−1). Subsequently, the systems were gradually heated to 500 K at a rate of 0.01 K ps−1, equilibrated at this elevated temperature, and then cooled to 100 K using the same rate. Glass-transition behavior was determined from the density-temperature profiles obtained during heating and cooling cycles. To reduce artifacts from quench history, snapshots collected along the cooling trajectory were subjected to an additional 1 ns NPT equilibration before entering production runs. Final production simulations were carried out for 25 ns in both the NPT and NVT ensembles at selected temperatures, and trajectories were analyzed to extract thermophysical properties. Three independent replicates were performed with randomized seeds.

Additional details are provided in the Supplementary Information, including descriptions of model architecture, hyperparameter settings, evaluation protocols, and implementation details. The Supplement also contains extended results and supporting analyses that further validate the robustness and generalizability of our approach across different molecular design tasks.

Data availability

The main data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in 10.5281/zenodo.13147126. Other data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Sanchez-Lengeling, B. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 361, 360–365 (2018).

Patani, G. A. & LaVoie, E. J. Bioisosterism: a rational approach in drug design. Chem. Rev. 96, 3147–3176 (1996).

Anderson, A. C. The process of structure-based drug design. Chem. Biol. 10, 787–797 (2003).

Vamathevan, J. et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 463–477 (2019).

Stokes, J. M. et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell 180, 688–702 (2020).

Nigam, A. et al. Tartarus: A benchmarking platform for realistic and practical inverse molecular design. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 36, 3263–3306 (2023).

Beaujuge, P. M. & Fréchet, J. M. Molecular design and ordering effects in π-functional materials for transistor and solar cell applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20009–20029 (2011).

Butler, K. T., Davies, D. W., Cartwright, H., Isayev, O. & Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 559, 547–555 (2018).

Merchant, A. et al. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 624, 80–85 (2023).

Yao, Z. et al. Machine learning for a sustainable energy future. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 202–215 (2023).

Gurnani, R. et al. AI-assisted discovery of high-temperature dielectrics for energy storage. Nat. Commun. 15, 6107 (2024).

Hansen, K. et al. Machine learning predictions of molecular properties: accurate many-body potentials and nonlocality in chemical space. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 2326–2331 (2015).

Cereto-Massagué, A. et al. Molecular fingerprint similarity search in virtual screening. Methods 71, 58–63 (2015).

Duvenaud, D. K. et al. Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints. In Proc. 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2224−2232 (NIPS, 2015).

Coley, C. W., Barzilay, R., Green, W. H., Jaakkola, T. S. & Jensen, K. F. Convolutional embedding of attributed molecular graphs for physical property prediction. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 57, 1757–1772 (2017).

Tshitoyan, V. et al. Unsupervised word embeddings capture latent knowledge from materials science literature. Nature 571, 95–98 (2019).

Morgan, H. L. The generation of a unique machine description for chemical structures-a technique developed at Chemical Abstracts Service. J. Chem. Document. 5, 107–113 (1965).

Glen, R. C. et al. Circular fingerprints: flexible molecular descriptors with applications from physical chemistry to ADMET. IDrugs 9, 199 (2006).

Nantasenamat, C., Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, C., Naenna, T. & Prachayasittikul, V. A practical overview of quantitative structure-activity relationship. EXCLI J. 8, 74–88 (2009).

Khan, A. U. et al. Descriptors and their selection methods in qsar analysis: paradigm for drug design. Drug Discov. Today 21, 1291–1302 (2016).

Elton, D. C., Boukouvalas, Z., Fuge, M. D. & Chung, P. W. Deep learning for molecular design-a review of the state of the art. Mol. Syst. Design Eng. 4, 828–849 (2019).

David, L., Thakkar, A., Mercado, R. & Engkvist, O. Molecular representations in AI-driven drug discovery: a review and practical guide. J. Cheminform. 12, 56 (2020).

Walters, W. P. & Barzilay, R. Applications of deep learning in molecule generation and molecular property prediction. Accounts Chem. Res. 54, 263–270 (2020).

Wigh, D. S., Goodman, J. M. & Lapkin, A. A. A review of molecular representation in the age of machine learning. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 12, e1603 (2022).

Li, Z., Jiang, M., Wang, S. & Zhang, S. Deep learning methods for molecular representation and property prediction. Drug Discov. Today 27, 103373 (2022).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2014).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Gómez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules. ACS Central Sci. 4, 268–276 (2018).

Jin, W., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Junction tree variational autoencoder for molecular graph generation. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2323–2332 (PMLR, 2018).

Weininger, D. Smiles, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inform. Comput. Sci. 28, 31–36 (1988).

Simonovsky, M. & Komodakis, N. Graphvae: Towards generation of small graphs using variational autoencoders. In International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, 412–422 (Springer, 2018).

Serratosa, F. Graph regression based on autoencoders and graph autoencoders. In International Conference on Pattern Recognition, 345–360 (Springer, 2024).

Reiser, P. et al. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 3, 93 (2022).

Jin, W., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Hierarchical generation of molecular graphs using structural motifs. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 4839–4848 (PMLR, 2020).

RDKit. RDKit : Open-Source Cheminformatics. http://www.rdkit.org (2025).

Liu, Q., Allamanis, M., Brockschmidt, M. & Gaunt, A. Constrained graph variational autoencoders for molecule design. In Proceedings of the 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 7806−7815 (NeurIPS, 2018).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS, 2017).

Ramakrishnan, R., Dral, P. O., Rupp, M. & Von Lilienfeld, O. A. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci. Data 1, 1–7 (2014).

Faber, F. A. et al. Machine learning prediction errors are better than DFT accuracy. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 5255–5264 (2017).

Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O. & Dahl, G. E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In Int. Conference on Machine Learning, 1263–1272 (PMLR, 2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Schneider, L. et al. In silico active learning for small molecule properties. Mol. Syst. Design Eng. 7, 1611–1621 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Water-mediated ion transport in an anion exchange membrane. Nat. Commun. 16, 1099 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.d.P. conceived the project. M.H. and G.S. designed the model architecture. M.H. and G.S. performed model training and simulations. P.F.N. designed the ablation study experiments. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, M., Sun, G., Nealey, P.F. et al. Attention-based functional-group coarse-graining: a deep learning framework for molecular prediction and design. npj Comput Mater 11, 355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01836-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01836-7