Abstract

A coarse-grained neuroevolution potential (CGNEP) for multilayered graphene based on an ab initio accuracy dataset is developed for mesoscale molecular dynamics simulations. The information loss in coarsening process is discussed and divided into intralayer part and interlayer part. The CGNEP describes the interlayer shear introduced by van der Waals interactions well by modifying the descriptor of NEP. The mechanical properties and vibration frequencies of structures of different sizes are well predicted via CGNEP. Compared with the traditional empirical CG potential, the CGNEP possesses interlayer properties of the structure of graphene and maintains the ability for higher mapping ratio coarsening. The frequencies of a 12-layer graphene membrane with a length and width of 1 μm are directly calculated via the CGNEP with a 64:1 mapping ratio and compared with the experimental results. The proposed CGNEP may be further used for other multilayered CG 2D materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are widely used in thermo, electronic, and mechanical research fields and have been proven to be reliable1,2. The ab initio MD (AIMD) simulation has high accuracy but is too time-consuming. The empirical force field MD (EFFMD) simulation has a relatively high calculation speed, but the accuracy is relatively insufficient. To address these limitations, Behler and Parrinello proposed a neural-network representation for a high-dimensional potential energy surface (PES)3. By representing the system energy as a sum of atomic contributions and representing the local atomic environment by the descriptor, the application of machine learning potentials (MLPs) for arbitrary size system is paved. In recent years, the machine learning method has been widely used to fit the PES constructed via ab initio calculations4,5,6,7,8, which has shown a strong fitting ability. The MLP calculation has a comparable accuracy to the AIMD and has the same calculation time complexity as EFFMD9, which enables a larger scale and longer time period calculation with ab initio accuracy. However, in micrometer-scale calculations or microsecond-scale calculations, the existing all-atom MD simulation methods are still too time-consuming and expensive.

To overcome the restriction of the simulation scale, coarse-grained MD (CGMD) method was proposed and used to investigate large system properties10,11,12,13. CGMD is a multiscale approach in which groups of atoms are clustered into coarse-grained (CG) beads that interact through CG potentials. CGMD accelerates the calculation by significantly reducing the degree of freedom of the system while maintaining certain system features14,15,16. The CG potential construction methods can be divided into three categories: bottom-up approaches, top-down approaches and hybrid approaches17. The CG potential constructed via the bottom-up approach is also called the potential of mean force (PMF), which is constructed from the atomistic simulation to reproduce the thermodynamic and structural properties. The force-matching method is a practical bottom-up approach that was first proposed to construct the all-atom potential18,19 and was subsequently used to obtain a multiscale CG potential14,20. The force-matching method is naturally suitable for MLPs due to their similar optimization procedure for constructing the energy surface21,22,23,24,25,26. Compared with the complex and time-consuming traditional CG potential construction method, the dataset-based MLP method is relatively easy and fast.

Graphene is a classical two-dimensional van der Waals material with a single-layer atomically thick hexatomic ring structure, which has attracted extensive attention due to its outstanding mechanical properties in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) and nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS)27,28,29,30,31,32. The vibration frequencies of a micro-nano structure in MEMS/NEMS can be obtained by performing the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on the sampled time-displacement information in MD simulation. For the large-sized structure, the nature frequency is lower and needs a longer sampling time in MD simulation to obtain a higher frequency resolution, which further demands for the computational speed. However, the sizes of MEMSs and some NEMSs are too large for all-atom MD simulations. To overcome the difficulty in calculating scales, a modified mechanical continuum model33,34,35,36 and mesoscale CGMD calculation methods37,38 have been proposed, both of which aim to reduce the calculation complexity of the system and accelerate the calculation. The combination of the accuracy of MLP and the fast calculation speed of CG method holds great potential for mesoscale problems. GPUMD is an open-source MD package for highly efficient all-atom simulations that uses the neuroevolution potential (NEP) to generate a neural-network-based MLP4,39. It is completely implemented in graphic processing units (GPUs) and thus realizes a high computation speed40, which is suitable for CGMD calculations.

In this work, by combining the computational advantages of the CG method and GPUMD, the coarse-grained neuroevolution potential (CGNEP) based on bottom-up approach is proposed. Multiscale CGMD research based on an ab initio accuracy dataset for multilayered CG graphene via CGNEP is carried out. CGNEP maintains the interlayer shear properties of the structure of multilayered graphene after the CG process, which can be further coarsened with a higher mapping ratio for micrometer-scale calculations. The CGNEP construction process using the force-matching method is first demonstrated. The intralayer and interlayer information loss induced training noise is discussed. The static and dynamic properties of CG graphene are then presented. Additionally, the higher mapping ratio CGNEP and the calculation speed are discussed, the experimental scale direct CGMD calculation is performed and compared with experiment results.

Results

CGNEP construction

The basic coarsening mapping ratio for graphene is chosen to be 4:1, which means that each CG bead represents 4 carbon atoms of the original all-atom graphene, as shown in Fig. 1. The orange atoms denote the all-atom graphene, and the gray beads denote the CG graphene. After the CG process, the atoms a, b, c and d in all-atom graphene are mapped to the CG bead i in CG graphene, and the position of CG bead i is close to the position of atom a. The mass of the CG bead is the total mass of the 4 carbon atoms. The position of the CG bead is the center of mass of the 4 carbon atoms. Thus, the force acting on the CG bead is the accumulation of forces acting on the 4 carbon atoms14. Through the coarsening method mentioned above, consider a three-dimensional all-atom configuration r that containing N atoms with the atomic forces F(r). The CG configuration is derived from the all-atom configuration by mapping N atoms to n beads:

where x is the CG configuration with n beads, \({\boldsymbol{\Xi }}\) is the mapping symbol used to map atoms to beads, and N = 4n for the 4:1 mapping ratio. The CG force FCG on bead j in the CG configuration x is

where i represents the atoms corresponding to bead j. For those molecules with non-uniform atomic mass distribution, the atomic positions that contribute to the CG positions are mass-weighted. The atomic forces that contribute to the CG forces are still simple accumulations under certain conditions14,20.

In the CG mapping process, in addition to several different all-atom configurations mapped to the same CG configuration, the same all-atom configuration mapped to several different CG configurations also exist, which was not mentioned in previous works. A bilayer graphene is considered, as shown in Fig. 2a, the upper graphene sheet moves in the armchair direction. The mapped CG graphene stacking order and the corresponding all-atom graphene stacking order varies with the upper sheet graphene movement, as shown in Fig. 2b. By moving the upper sheet graphene along the zigzag direction a certain distance and then moving along the armchair direction, the other stacks of mapped CG graphene are shown in Fig. 2c. However, the mapped CG graphene stacking order variation cycle is 8.4 Å, which is twice the variation cycle of all-atom graphene stack varies because the bond length of CG graphene is twice the bond length of all-atom graphene. Taking the all-atom graphene and CG graphene in Fig. 2b as an example, for all-atom graphene, the first 3 stacking orders are the same with the second 3 stacking orders and these 6 stacking orders form 2 variation cycles of stacking order for all-atom graphene. However, after CG process, the mapped first 3 CG graphene stacking orders are different with the second 3 stacking orders for CG graphene, because the 6 stacking orders together form 1 variation cycle for CG graphene stacking orders. This phenomenon shows that for bilayer graphene with periodic boundaries, the same all-atom configuration may be mapped to several different CG configurations, which makes accurate describing of the interlayer interaction for CG graphene with multiple layers difficult. For the graphene with more than two layers, the cutoff region of the descriptor in an MLP will include more layers and makes the same all-atom configuration mapped to more different CG configurations. This phenomenon is the interlayer information loss induced by interlayer shear and stacking orders in CG graphene. For situations with a higher mapping ratio, the cutoff radius is even larger, which includes much more layers and causes the same all-atom configuration to be mapped to more CG configurations.

a Double-layered all-atom graphene, with the upper sheet moving in the armchair direction. b The all-atom stacks and the mapped CG stacks. The blue and red hexagons denote the upper and lower sheets of graphene, respectively. The upper sheet of all-atom graphene moves in the armchair direction a bond length each time, and the upper sheet of mapped CG graphene moves the same distance as all-atom graphene. c The other stacks of all-atom graphene and mapped stacks of CG graphene after moving the upper sheet along the zigzag direction a certain distance.

Theoretically, the only distinction between coarse-grained machine learning potential (CGMLP) training and all-atom MLP training is that in CGMLP training, only the force information is used. However, when the original NEP framework is applied to train the CG potential for multilayered graphene, it is found difficult to determine the interlayer interaction well. Thus, by constraining the cutoff regions of the descriptor components to reduce the interlayer information loss, the CGNEP framework is obtained. The CGNEP framework is constructed based on the fourth-generation neuroevolution potential (NEP4)41 framework. The GPUMD package version 3.9.4 is used for training the potential and performing the CGMD calculations. In the NEP framework, the local atomic environment is described by the descriptor, which is an abstract vector with two sets of components: radial descriptor components and angular descriptor components, and each set of components has a cutoff radius39,40. The radial descriptor components include only distance information, which is the summation of the functions of the distances between all the neighboring atoms and the central atom. Similarly, the angular descriptor components include both distance information and angular information, which are the summation of the functions of distances and angles between all the neighboring atoms and the central atom. The number of descriptor components is related to the parameters set before the training process. The descriptor vector contains the local atomic environment information of the central atom, and it is the input of the fitting network, which predicts the system energy.

Considering the multilayered all-atom graphene shown in Fig. 3a, for a NEP, the radial and angular descriptor components cutoff regions are spherical regions, which are determined by the radial cutoff radius and the angular cutoff radius, as shown in Fig. 3b. The radial descriptor components are usually used to capture relative long-range interactions, and the angular descriptor components are usually used to capture intermediate-range interactions. As shown in Fig. 3c, in a CGNEP, in addition to the radial and angular cutoff radii, another parameter Z is used, which constrains the original spherical cutoff region to the drum-like cutoff region in the out-of-plane direction (z direction). The parameter Zradial constrains the radial descriptor components cutoff region, and the parameter Zangular constrains the angular descriptor components cutoff region. Here, Zradial is set as 10 Å, and Zangular is set as 4 Å to ensure that the radial descriptor components consider only the adjacent layers and neglect the remaining layers in the z direction, and the angular descriptor components consider only the single layer where the current central bead is located, as shown in Fig. 3c.

a Multilayered all-atom graphene model. The out-of-plane direction is the z direction. b The radial descriptor components and angular descriptor components cutoff regions of the NEP. The orange region denotes the descriptor cutoff region of NEP for the central atom. c The radial descriptor components and angular descriptor components cutoff regions of CGNEP, in which the out-of-plane direction (z direction) is constrained to avoid considering too many layers. Here, Zradial is set as 10 Å, and Zangular is set as 4 Å. The orange region denotes the modified descriptor cutoff region of CGNEP for the central bead.

The only distinction between the NEP framework and CGNEP framework is the cutoff region of the descriptor components. This approach further accelerates the CGMD calculation speed and makes higher mapping ratio CGNEP training possible because the higher the mapping ratio, the larger the cutoff radius. The more beads and layers to be considered by the descriptor, the more CG configurations an all-atom configuration is mapped to, and the interlayer interaction becomes much more complicated with increased interlayer information loss. However, no matter how large the cutoff radius is, only the adjacent layers are considered at most for CGNEP.

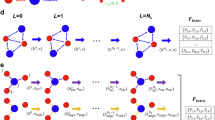

If not specifically stated, all-atom calculations and samplings in this work are performed by using the NEP-C-PBE + D342. The NEP trained for CG calculations from training datasets generated from NEP-C-PBE + D3 is represented by the NEP-CG, in which the descriptor remains unmodified. Thus, the only distinction between NEP-CG and an all-atom NEP is the used training dataset, and the only difference between NEP-CG and CGNEP is the descriptor. The schematic overview of CGNEP framework training and calculation combined with GPUMD is shown in Fig. 4. The all-atom trajectories and forces are first obtained from all-atom MD calculations, then according to the chosen CG mapping ratio, the all-atom configurations are directly mapped to CG configurations to construct the CG training dataset. After the CG training dataset is generated, the CGNEP can be constructed by using the modified descriptor.

The all-atom trajectories and forces are first obtained from all-atom MD calculations, then the CG mapping ratio is chosen. According to the decided mapping ratio, the all-atom configurations are directly mapped to CG configurations to construct the CG training dataset. After the CG training dataset is generated, the CGNEP can be constructed by modifying descriptors and used for CGMD calculations.

Training results and information loss analysis

The mentioned CGNEP and NEP-CG are all constructed based on the training dataset generated from the NEP-C-PBE + D3, with CGNEP employing the Zradial = 10 Å and Zangular = 4 Å, if not specifically stated.

The training force root mean square errors (RMSEs) during training for CGNEP, NEP-CG, and an all-atom NEP are shown in Fig. 5a, d, f, respectively. The all-atom NEP is trained only for illustrating the difference between CG training and all-atom training. The all-atom training dataset is generated using Tersoff potential with LJ potential describing interlayer interaction of multilayered graphene. The same as CG training, only the force information is used in the all-atom training. However, different from all-atom training, the force RMSE of CG training converges to a nonzero constant, as shown in Fig. 5a, d. This phenomenon is caused by the CG noise23, which is induced by the information loss.

a, d, f are the force RMSEs of CGNEP, NEP-CG and all-atom NEP in the training process, respectively. The all-atom NEP trained here is only for illustrating the difference between CG training and all-atom training. b, e, g are the CGNEP, NEP-CG and the trained all-atom NEP predicted forces compared with the forces in training datasets, respectively. The blue, orange and yellow dots denote the forces in the x, y and z directions, respectively. c Red and blue hexagons denote CG and all-atom graphene, respectively. Atoms a, b, c and d are the atoms being mapped to CG bead i. For the 2 situations, CG beads i1 and i2 have the same coordinates but different external forces act on them.

The reason for the noises in Fig. 5a, d is the reduction of the degree of freedom, although the CG configurations mapped from different all-atom configurations are the same, the external forces acting on these mapped CG configurations are different from those of the original all-atom configurations. More specifically, the information loss in CG mapping process for graphene can be divided into 2 parts, intralayer information loss and interlayer information loss.

For the intralayer information loss, consider the 4 atoms a, b, c, and d belong to all-atom graphene in Fig. 5c, the 4 atoms are mapped to CG bead i after the CG process. The red hexagons denote CG graphene, and the blue hexagons denote all-atom graphene. Consider that there are 2 situations, in which only the coordinates of atoms a1, b1, c1 and d1 are different from those of a2, b2, c2 and d2, the remaining atoms in the 2 situations have the same coordinates. Suppose that in the 2 situations, CG beads i1 and i2 have the same coordinates after the CG process. Thus, all the CG beads in the 2 situations have the same coordinates. For both situations, the total external forces of the 4 atoms are different. Thus, after coarsening, the forces of the CG beads i1 and i2 are different. Thus, the CG configurations to which CG beads i1 and i2 belong are completely the same, and the CG beads i1 and i2 have the same coordinates but different forces. This phenomenon leads to several different all-atom configurations being mapped to the same CG configuration during the CG process, which is the intralayer information loss during the CG process for graphene. In general, the intralayer information loss, as shown in Fig. 5c, is related with the intralayer wrinkle and causes several different all-atom configurations mapped to the same CG configuration.

The interlayer information loss, as shown in Fig. 2 and discussed in Section “CGNEP construction”, is related to the interlayer shear and the resulting stacking order variation. This phenomenon causes the same all-atom configuration mapped to several different CG configurations.

In conclusion, the force predicted by the trained NEP-CG or the CGNEP is a mean force, which is the average value of all the same CG configurations because of the intralayer and interlayer information loss.

As shown in Fig. 5b, e, the detailed mapped CG forces in the training dataset and the CG forces predicted by CGNEP and NEP-CG are compared. In a well-trained all-atom MLP for all-atom MD calculation, the predicted forces of the configurations strictly correspond to the forces in the training dataset, as shown in Fig. 5g. Thus, the points are distributed almost exactly on the diagonal line. However, the points shift horizontally away from the diagonal line for the CG situation, as shown in Fig. 5b, e. Taking Fig. 5b as an example, the reason is that the predicted CG force of the CG configuration is a mean force, corresponding to a certain value on the vertical axis. However, the all-atom forces of the all-atom configurations to be mapped to the CG forces of the CG configuration are a series of instantaneous forces, which correspond to multiple points distributed along the horizontal axis around the mean force. The vertical coordinates of the intersection of the three horizontal purple lines and the diagonal line are the mean CG forces, and the three forces are predicted by the CGNEP for the three certain CG configurations. The corresponding CG instantaneous forces are the points distributed on the three horizontal purple lines. The intersection value of the horizontal purple line and the diagonal line is the mean force of the instantaneous CG forces.

The information loss induces non-one-to-one correspondence between the CG configurations and the CG forces in the training datasets, which is the underlying reason for the noises in Fig. 5a, b, d, e. In an all-atom NEP training procedure, one certain configuration corresponds to a certain force, as shown in Fig. 5g. Thus, the force shift does not exist in an all-atom MLP training, and the training loss is able to converge to zero. In addition, the noise in Fig. 5a is slightly smaller than the noise in Fig. 5d. This is because the CGNEP considers a smaller cutoff region than the NEP.

Although the comparisons of the training forces and prediction forces seem similar in Fig. 5, the CGNEP and the NEP-CG still give completely different predictions in MD simulations for multilayered graphene. This phenomenon is another difference between all-atom MLP training and CGMLP training. The trained CGMLP sometimes cannot be directly evaluated by force RMSE analysis or force comparisons but needs further MD calculations.

Uniaxial tensile calculation with CGNEP and NEP

The stress‒strain curves are shown in Fig. 6a, b. Young’s moduli in the armchair direction given by CGNEP, NEP-C-PBE + D3 and NEP-CG are 886.2 GPa, 883.6 GPa and 923.2 GPa, respectively. Young’s moduli in the zigzag direction given by CGNEP, NEP-C-PBE + D3, and NEP-CG are 880.5 GPa, 891.3 GPa, and 915.9 GPa, respectively. The CGNEP and NEP-CG both predict Young’s moduli well compared with all-atom calculations, which indicates that the tensioned structures in the training dataset have effectively expanded the configuration space.

Interlayer shear calculation with CGNEP and NEP

The interlayer shear introduced by van der Waals interactions affects the frequency of multilayered graphene35,43. Shear simulations are carried out to calculate the interlayer shear modulus by modifying the coordinates of bilayer graphene. The shear modulus can be calculated from the energy‒strain relationship. The energy‒strain curves obtained from the all-atom calculations compared to those from CG calculations using CGNEP and NEP-CG are shown in Fig. 7a, b, respectively. The shear modulus G can be calculated by

where a, b, and h are the length, width and thickness of the model, respectively. U is the total system potential energy, and γ is the shear strain. By fitting the energy‒strain curves in Fig. 7a, b, the interlayer shear moduli of the all-atom graphene produced by all-atom calculations in the armchair and zigzag directions are 1.434 GPa and 1.816 GPa, respectively. The corresponding values given by CGNEP are 1.457 and 1.392 GPa, while those from NEP-CG are 8.565 and 9.081 GPa. Compared with NEP-CG, the CGNEP gives the interlayer shear modulus closer to the all-atom calculation result.

a Interlayer shear energy‒strain comparisons between all-atom potential NEP-C-PBE + D3 and CGNEP calculations. The black square points and black upright triangular points joined by solid lines denote all-atom results in armchair direction and zigzag direction, respectively. The red circular points and red inverted triangular points joined by solid lines denote CG results in armchair direction and zigzag direction, respectively. b Interlayer shear energy‒strain comparisons between all-atom potential NEP-C-PBE + D3 and NEP-CG calculations.

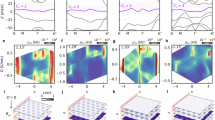

The contour plots of the total system energy distributions of NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP and NEP-CG for bilayer graphene are shown in Fig. 8a, c, e, respectively. The CG cell sizes in Fig. 8c, e are twice that of the all-atom cell in Fig. 8a, because the cell of CG graphene is twice the cell of all-atom graphene, consistent with the 4:1 mapping ratio. AB stack (stack 2) in Fig. 8a, c, e is located at the low-energy state, which is the same as all-atom calculation. The results indicate that NEP-CG and CGNEP both capture the stable AB stack of the hexagonal structure of graphene.

a, c, e are the system energy contour plots of the all-atom NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP, and NEP-CG calculations predicted interlayer energy distributions, respectively. The white dots 1 and 2 denote the AA stack and AB stack of graphene, respectively. The X and Y coordinates denote the shear displacement of the upper sheet graphene in the armchair direction and zigzag direction, respectively. b, d, f are the system energies predicted by all-atom, CGNEP and NEP-CG calculations in the deep blue rectangular boxes in (a, c, e) with constant Y coordinates, respectively.

Figure 8b, d, f show the system energy during interlayer shear deformation along the armchair direction given by the all-atom, CGNEP and NEP-CG calculations, respectively. The insets show the detailed strain-energy relationship of the AB stack. Although NEP-CG exhibits a similar interlayer energy tendency with CGNEP for the region near the AB stack, the interlayer shear modulus of NEP-CG is quite different from that of CGNEP and all-atom calculation, as shown in Fig. 7. This phenomenon may be caused by the multiple layers considered by the angular descriptor components in NEP-CG, which is discussed later by the dynamics analysis.

Interlayer shear calculation with empirical CG potential

To assess the interlayer shear property of CG graphene given by the existing empirical CG potential, the interlayer energy distributions of bilayer graphene given by the empirical all-atom potential and empirical CG potential TersoffCG44 with CGLJ37,44 are shown in Fig. 9. The CGLJ potential is the LJ potential using parameters for CG graphene. The interlayer energy distribution of CG graphene in Fig. 9c is different from the distribution given by the all-atom simulation in Fig. 9a. Different from the case of all-atom graphene, the AB stack (stack 4) in Fig. 9c is a high-energy state and is a nonstable stack for the CGLJ potential. When shearing along the armchair direction (x direction) or the zigzag direction (y direction), the energy of the AB stack system given by empirical CGLJ potential decreases. According to Eq. (3), the shear modulus is negative. Negative shear moduli in the x and y directions mean that the structure is unstable and leads to the buckling of the structure because of the unbalanced interlayer interactions. However, the interlayer shear modulus for AB stack given by all-atom calculation is positive, which means that the AB stack is still a stable configuration.

a, c are the system energy contour plots of the all-atom and CG empirical potential calculations predicted graphene interlayer energy distributions, respectively. The white dots in the contour plot denote the stacking orders. The X coordinate and Y coordinate denote the shear displacement of the upper sheet graphene in the armchair direction and zigzag direction, respectively. b, d are the all-atom and CG system energy variations in the deep blue rectangular box in (a, c) with constant Y coordinates, respectively.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 9c, the empirical CGLJ potential yields 3 relatively stable stacks 1, 2, and 3 for CG graphene. The interlayer shear of stack 1 in Fig. 9c is weak in the y direction and relatively strong in the x direction, which indicates that the interlayer shear near stack 1 is anisotropic. The interlayer shear of stack 2 in Fig. 9c is weak in the 30° direction and relatively strong in the −60° direction, which means that the interlayer shear near stack 2 is also anisotropic. The interlayer energy surface of stack 3 in Fig. 9c is a saddle-shaped surface, which means that the interlayer shear here is positive in the x direction but negative in the y direction. Thus, the interlayer shear near stack 3 is also anisotropic. However, these three stacks are all unstable stacks for all-atom graphene. As shown in Fig. 9a, for all-atom graphene, AB stack is the only stable stack.

In summary, for multilayered CG graphene, the CGLJ potential used by the empirical CG potential alters the interlayer energy distribution. AB stack is stable in all-atom graphene but unstable in CG graphene given by CGLJ potential. The 3 relatively stable stacks in Fig. 9c given by CGLJ potential are unstable stacks for all-atom graphene, and show strong anisotropic interlayer shear. The altered interlayer shear by the empirical CGLJ potential may affect the accuracy of the CG graphene vibration calculations. In contrast, the CGNEP predicts the interlayer shear more accurately, yielding closer results to the all-atom potential.

Vibration calculation with CGNEP and NEP

To further illustrate the difference between NEP-CG and CGNEP, the vibration frequencies are obtained from thermal vibration simulations. The frequencies of rectangular graphene membranes from single layer to 12 layers predicted by NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP, and NEP-CG calculations are compared in Fig. 10a, b. As the number of layers increases, the deviation of the frequencies predicted by NEP-CG continues to rise, whereas the frequencies given by CGNEP remain close to the results given by all-atom calculations. The used rectangular CG graphene membrane model and the corresponding first 3 order vibration mode shapes are shown in Fig. 10c. The blue region of CG graphene membrane model denotes the fixed beads to simulate the clamped boundary condition, the red region denotes the free beads. The first-order frequency error of CGNEP and NEP-CG compared with all-atom calculation is shown in Fig. 10d. The reason for the much higher frequencies given by NEP-CG is the much higher interlayer shear modulus given by NEP-CG, as shown in Fig. 7b. The frequency of the multilayered graphene increases rapidly as the interlayer shear modulus increases35,43. In contrast, the interlayer shear modulus given by CGNEP is close to that of all-atom graphene, thus the frequencies match better. As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, the frequencies of circular graphene with different sizes predicted by the all-atom, CGNEP and NEP-CG calculations are also compared. The results are similar with the rectangular graphene. In conclusion, the NEP-CG predicts a much stronger interlayer shear compared with CGNEP and all-atom calculations, which induces a much higher frequency.

a The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for single layer, bilayer, and 3 layers graphene membranes. The black square points, red circular points and blue triangular points joined by solid lines denote results obtained via NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP, and NEP-CG calculations. b The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for 4, 6, and 12 layers graphene membranes. c Rectangular CG graphene membrane model and the first 3 order vibration mode shapes of the rectangular model. The blue region in the membrane model denotes the fixed beads to simulate the clamped boundary condition, the red region in the membrane model denotes the free beads. d The first-order frequency error of CGNEP (black) and NEP-CG (wine red) compared with all-atom calculation.

a The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for single layer, bilayer and 3 layers CG graphene membranes. The black square points, red circular points and blue triangular points joined by solid lines denote results obtained via NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP, and NEP-CG calculations. b The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for 4 layers, 6 layers, and 12 layers CG graphene membranes. c Circular CG graphene membrane model and the first 3 order vibration mode shapes of the circular model. The blue region in the membrane model denotes the fixed beads to simulate the clamped boundary condition, the red region in the membrane model denotes the free beads. d The first-order frequency error of CGNEP (black) and NEP-CG (wine red) compared with all-atom calculation.

a The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for single layer, bilayer, and 3 layers CG graphene membranes. The black square points, red circular points, and blue triangular points joined by solid lines denote results obtained via NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP, and NEP-CG calculations. b The first 3 order frequencies comparisons for 4 layers, 6 layers, and 12 layers CG graphene membranes. c Circular CG graphene membrane model and the first 3 order vibration mode shapes of the circular model. The blue region in the membrane model denotes the fixed beads to simulate the clamped boundary condition, the red region in the membrane model denotes the free beads. d The first-order frequency error of CGNEP (black) and NEP-CG (wine red) compared with all-atom calculation.

The only distinction between CGNEP and NEP-CG is the used descriptor cutoff region, the descriptor in NEP-CG considers more layers. To further investigate the reason for the overestimated interlayer shear induced high frequency given by NEP-CG, another CGNEP by setting the Zangular in Fig. 3c as 10 Å is trained here to assess the influence of descriptor. The newly trained CGNEP is named CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å), and the original CGNEP is named CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å). If not specifically indicated, all the other CGNEPs mentioned in this work are CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å).

As mentioned in Section “CGNEP construction” and Fig. 3, the CGNEP framework is constructed by constraining the descriptor components cutoff regions of the NEP. In CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å), by setting the Zradial as 10 Å and the Zangular as 4 Å, the radial descriptor components consider only the adjacent layers and neglect the remaining layers, and the angular descriptor components are restricted to the intralayer environment. In CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å), by setting the Zradial and Zangular as 10 Å, both the radial and angular descriptor components consider the adjacent layers.

Compared with CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å), CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) consider adjacent layers in angular descriptor components. Compared with NEP-CG, CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) considers only the adjacent layers in both radial and angular descriptor components, neglects the remaining layers.

As shown in Fig. 13, the first-order vibrational frequencies of the rectangular and circular graphene model with different numbers of layers are compared. For single-layer cases in Fig. 13a, b, the frequencies predicted by CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) agree well with those by all-atom calculations. The agreement indicates that the intralayer properties of CG graphene are also well described by CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å).

a The predicted first-order frequencies of rectangular and b circular graphene membranes with different number of layers. The black square points, red circular points, blue upright triangular points and purple inverted triangular points joined by solid lines denote results obtained via all-atom, CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å), NEP-CG and CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) calculations, respectively. In CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å), both angular and radial descriptor components consider adjacent CG graphene layers. In CGNEP(Zang = 4 Å), radial descriptor components consider adjacent CG graphene layers, and angular descriptor components only consider the single CG graphene layer and neglect the rest CG graphene layers.

For multilayered cases in Fig. 13a, b, the frequencies given by CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) and NEP-CG are similar, but still deviate significantly from the results given by all-atom calculations and CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å). For CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) and NEP-CG, the radial and angular descriptor components in NEP-CG consider more layers than CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å), but the frequencies given by them are still similar. Thus, the overestimated frequency is not mainly induced by the further layers other than the adjacent layers considered by the descriptor. For CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å) and CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å), only the angular descriptor components cutoff regions are not the same, and the frequencies given by them are significantly different. Thus, the overestimated frequency is mainly induced by the angular descriptor components cutoff regions considering adjacent layers.

For multilayered graphene, the intralayer properties and interlayer shear modulus are the key influencing factors for vibration frequency. The intralayer properties are proven to be successfully captured, and interlayer shear is not captured by NEP-CG as shown in Fig. 7. Meanwhile, for 2-layer graphene case, CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) is the same with NEP-CG. Thus, CGNEP (Zang = 10 Å) and NEP-CG both give overestimated interlayer shear modulus and give similar results for multilayered cases in Fig. 13. From the discussions above, for multilayered CG graphene, the angular descriptor components considering adjacent layers overestimate interlayer shear modulus, thus overestimate vibration frequencies. Meanwhile, frequencies predicted by CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å) agree well with all-atom calculations, because CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å) successfully captures both intralayer and interlayer properties.

Vibration calculation with CGNEP and empirical CG potential

To further elaborate the reliability of the proposed CGNEP framework, a CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ based on the training dataset sampled from the all-atom empirical potential Tersoff+LJ is trained and compared with the empirical TersoffCG+CGLJ potential. In CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ, Zradial = 10 Å and Zangular = 4 Å, the same as CGNEP (Zang = 4 Å).

As shown in Fig. 14, the vibration frequencies and vibration modes of the 10-nm-diameter 4-layer graphene circular model obtained from the all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation, CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculation and empirical TersoffCG with CGLJ calculation are compared. Panels in Fig. 14a show the frequency spectrums and mode shapes of AB stack graphene predicted via the all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation, the relatively stable stack 1, stack 2, and stack 3 CG graphene predicted via the empirical CG potential, and the AB stack CG graphene predicted via the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ. As shown in Fig. 9c, the AB stack given by CGLJ potential is unstable. Thus, the AB stack CG graphene buckles in MD simulation using CGLJ potential, and the results are not shown in Fig. 14a. As shown by the blue rectangles in Fig. 14a, the second-order mode shapes are similar with the third mode shapes for stack 1, 2 and 3, and they both are similar with the second-order mode shape of AB stack given by all-atom MD calculation and CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculation. This phenomenon is the modal splitting for a circular model with rotational symmetry, the phenomenon shows there exist obvious mechanical anisotropy for the all 3 stacks of the multilayered CG graphene membrane calculated via the empirical CG potential. However, the in-plane property of CG graphene given by TersoffCG potential shows transversely isotropic from the mode shapes shown in Fig. 14b. The vibration frequencies and the corresponding mode shapes of the single layer circular graphene membrane obtained from the all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation, CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculation and TersoffCG potential calculation are similar, and the modal splitting phenomenon is not observed. The results show that both the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ and the TersoffCG potential can predict relatively accurate frequencies and transversely isotropic properties for single-layer graphene, which means the anisotropic vibration mode shapes of multilayered CG graphene are induced by the CGLJ potential used in the empirical CGMD. Further, as shown in the first and last panel of Fig. 14a, the multilayer all-atom graphene and the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculated multilayer CG graphene are also transversely isotropic, and the frequencies match well as shown in Fig. 14c. Thus, the anisotropy shown in the second to the fourth panel of Fig. 14a for the empirical CG potential is induced by anisotropic interlayer shear, which is introduced by the CGLJ potential used in the empirical CGMD simulation. The CGLJ potential changes the interlayer shear properties, leads to anisotropic vibration modes for multilayered CG graphene. Meanwhile, the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ successfully reproduces the interlayer shear properties of the all-atom graphene given by the all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential.

a Frequency spectrums and corresponding mode shapes of AB stack given by all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation, the 3 relatively stable stacks given by empirical CG potential calculation, and AB stack given by CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculation. b The first 3 order frequencies and mode shapes of single layer graphene calculated by Tersoff potential (black square points), CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ (red circular points) and TersoffCG potential (blue triangular points). c Comparison between the first 4 order frequencies given by all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation (black square points) and CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ calculation (red circular points) for the AB stack 4 layers circular graphene membrane with a diameter of 10 nm.

As discussed in Section “Interlayer shear calculation with empirical CG potential”, AB stack (stack 4) is a form of nonstable stack for the empirical CG potential, which buckled in the CGMD simulation. The interlayer shear of the remaining three relatively stable low-energy stacks given by the empirical CG potential is anisotropic. The reason for vibration frequencies given by empirical CG potential in Fig. 14a appear anisotropic is that the interlayer shear properties of the 3 stacks are anisotropic. For stack 1, the second-order mode shape is vertical, and the third-order mode shape is horizontal due to the strong anisotropy in both directions. The reason for the frequency of the mode shape in the y direction (third-order mode shape) being lower than that in the x direction (second-order mode shape) for stack 1 is that the interlayer shear in the y direction is weaker than that in the x direction, as shown in Fig. 9c. If the interlayer shear of stack 1 is isotropic, the second- and third-order mode shapes in the second panel of Fig. 14a will have the same order mode shape, as the modal splitting phenomenon vanishes. The frequency of stack 2 corresponding to the mode shape in the third panel of Fig. 14a along the 30° direction is lower, and the frequency corresponding to the mode shape along the −60° direction is higher. This is because the interlayer shear of stack 2 is weak in the 30° direction and relatively strong in the −60° direction, as shown in Fig. 9c. Compared with stacks 1 and 2, the frequency of the second-order mode shape of stack 3 is much lower than that of the third-order mode shape in the fourth panel of Fig. 14a, because the interlayer energy surface of stack 3 in Fig. 9c is a saddle surface, which means that the interlayer shear here is positive in the x direction but negative in the y direction. Thus, the interlayer shear anisotropy of stack 3 is stronger than that of stacks 1 and 2. Thus, the second-order frequency of stack 3 is lower than that of stack 1, because the interlayer shear in the y direction is lower. Similarly, the third-order frequency of stack 3 is higher than that of stack 1, because the interlayer shear in the x direction is higher. For multilayered CG graphene, the CGLJ potential used in empirical CG potential changes the interlayer energy distribution and causes anisotropic interlayer shear, which leads to anisotropic vibration frequency modes. Compared with the empirical CG potential, the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ predicts the interlayer shear better, thus, the frequencies predicted by the CGNEP-Tersoff+LJ fit better with the all-atom Tersoff and LJ potential calculation as shown in Fig. 14c. In general, the results illustrate that based on the training dataset generated using another all-atom potential, the proposed CGNEP framework can also capture the intralayer and interlayer properties of the graphene described by the other all-atom potential.

Larger mapping ratio coarse-graining of CGNEP

By coarsening 4 carbon atoms of the original all-atom graphene as 1 CG bead in CGNEP framework, the hexagonal lattice is retained and has the ability for larger mapping ratio coarsening. The 16 atoms can be coarse-grained as 1 bead to generate the CG training dataset, meanwhile, the hexagonal lattice is still retained. A larger mapping ratio (16:1 or higher) represents a longer bond length between CG beads but remains a relatively small interlayer distance, which may lead to the intersection between adjacent graphene layers38 for the classical empirical CG potential. Thus, the larger mapping ratio CG for the classical empirical CG potential results in the coarsening of multiple layers as a single layer38. Because the CGNEP framework calculates forces acting on a bead according to the local environment in the cutoff region of the central bead, the disadvantage of the high mapping ratio in the empirical CG potential mentioned above may be overcome. CGNEP-4:1 denotes the CGNEP framework in the previous sections. Additionally, CGNEP-16:1 with a mapping ratio of 16:1 and CGNEP-64:1 with a mapping ratio of 64:1 without coarsening several layers as a single layer, are trained here. The frequencies given by NEP-C-PBE + D3, CGNEP-4:1, CGNEP-16:1 and CGNEP-64:1 for a 4-layer model and a 6-layer model with a diameter of 50 nm are shown in Fig. 15. The results obtained via CGNEP-4:1 and CGNEP-16:1 match relatively well with the all-atom calculations using NEP-C-PBE + D3. There is a certain degree of deviation for the results obtained via CGNEP-64:1, because the mapping ratio is relatively large for this situation and the information loss is relatively high.

a Frequencies of 4-layer model and b 6-layer model with a diameter of 50 nm given by all-atom NEP-C-PBE + D3 (black square points), CGNEP-4:1 (red circular points), CGNEP-16:1 (blue upright triangular points) and CGNEP-64:1 (green inverted triangular points), respectively. The training datasets of the different mapping ratio CGNEPs are directly mapped from the all-atom configurations according to the chosen mapping ratio.

Further, a 12-layer mesoscale graphene with a length and width of 1 μm is calculated via the trained CGNEP-64:1 for direct comparison with the experimental results45. The CG graphene square model contains 7,144,512 CG beads with a length of 1002.38 nm and a width of 1003.16 nm, which is equivalent to 457,248,768 carbon atoms, which is the same size with one unit cell of the experiment device. The model is calculated via 2 Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 GPU cards, and the whole calculation for 26.4 ns took 174.1 h. The CGNEP calculated first 3 mode shapes are shown in Fig. 16a. The model for calculation is also shown in the subfigure of Fig. 16a. The blue regions denote the fixed beads to simulate the fixed boundaries, and the red region denotes the free CG beads. Notably, 4 boundaries of the square model are fixed boundaries with widths of 4 nm, which are too thin to be shown in the blue regions in the subfigure of Fig. 16a. The first three order frequencies of the model predicted by CGNEP are 166.67 MHz, 333.33 MHz and 500.00 MHz, and the frequency resolution is 41.67 MHz. The frequency resolution can be further enhanced by increasing the total number of steps of the calculation, which is enough here to separate the first-order frequency and the second-order frequency and plot the corresponding mode shapes. It can be adjusted as needed to balance the frequency accuracy and the total calculation time. The first three order frequencies given by the experiment45 are approximately 90, 190, and 320 MHz. A comparison between the experimental results and the CGNEP-64:1 calculation results is shown in Fig. 16b. Although CGNEP-64:1 overestimates the frequencies compared with the results of the experiment, the trends and the order of magnitude of the frequencies are still captured. Furthermore, the feasibility for micrometer-scale large mapping ratio CGMD calculation is verified here by the CGNEP-64:1. Notably, the stable calculation timestep can be set as a higher value up to 22 fs. In addition, not only a long calculation time but also a large amount of memory is needed to calculate the mesoscale structures for all-atom MD calculations. The proposed CGNEP-64:1 can largely reduce memory consumption, and a 12-layer model with a length and width of 1 μm can be deployed on a single Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 GPU card with a memory of 24 GB. Benefiting from the optimization for GPU parallel computing of GPUMD, the calculation can be further accelerated using more GPU cards, making memory-consuming large mesoscale model calculations possible.

a Vibration frequency spectrum of 1 μm CG graphene. The subfigure denotes the mesoscale 1 μm graphene CG model containing more than 7 million CG beads, which is equivalent to over 450 million carbon atoms. The blue region denotes the fixed CG beads used to simulate the clamped boundary, and the orange region denotes the free CG beads. b Comparison of the first 3 order frequencies between the experimental result45 (black square points) and the CGNEP-64:1 calculation result (red circular points).

The computational speeds of the NEP, the Tersoff potential with the LJ potential, the CGNEP, and the TersoffCG potential with the LJ potential are discussed. The unit for calculation speed is usually atom-step per second, for the different CG mapping ratios and calculation timesteps used in CG potentials, the unit for calculation speed here is atom-femtosecond per second. For example, for an all-atom potential with a calculation speed of 1 × 107 atom-fs/s, the calculation speed of the ideal corresponding CG potential with a 4:1 mapping ratio and a 5 fs timestep is 2 × 108 atom-fs/s. The empirical MD calculations are performed via LAMMPS with 56 Intel Xeon-Gold 6258R CPU cores (1 node with 56 cores), and the NEP and CGNEP are performed via GPUMD with 1 Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 GPU card. Notably, the CPU and GPU resources used for comparison here are of comparable price. The simulation model for CGNEP-64:1 is a 6-layer graphene with a diameter of 100 nm, which contains 49,152 beads. The simulation model for the comparison of the remaining potentials is 6 layers of graphene with a diameter of 50 nm. The all-atom graphene model contains 786,432 atoms, the CG graphene model with a mapping ratio of 4:1 contains 196,608 beads, and the CG graphene model with a mapping ratio of 16:1 contains 49,152 beads. The timesteps used in CGMD simulations with CGNEP-4:1, CGNEP-16:1 and CGNEP-64:1 are 8 fs, 15 fs and 22 fs, respectively. The timestep used in empirical CGMD simulations with TersoffCG potential is 7 fs. The timesteps used in the all-atom MD simulations with the Tersoff potential and NEP are both 1 fs. As shown in Fig. 17a, the calculation speeds of Tersoff+LJ, TersoffCG+LJ, NEP, CGNEP-4:1, CGNEP-16:1 and CGNEP 64:1 reach 1.180 × 107, 6.062 × 108, 1.186 × 107, 5.089 × 108, 3.511 × 109 and 1.549 × 1010 atom-fs/s, respectively. Compared with the empirical CG potential TersoffCG with the LJ potential, the proposed CGNEP-4:1 achieves a near calculation speed, CGNEP-16:1 and CGNEP-64:1 achieve nearly 6 times faster and 25.5 times faster calculation speeds. Compared with all-atom calculation, the calculation speeds of CGNEP-4:1, CGNEP-16:1 and CGNEP-64:1 can reach 42.9 times faster, 296 times faster and 1306 times faster, respectively. Theoretically, the calculation speed of CGNEP-4:1 should be 32 times faster but not 42.9 times faster than that of NEP when the mapping ratio is 4:1 and the timestep is 8 fs. However, because the cutoff regions of descriptor components in CGNEP are constrained, the number of beads in the cutoff region with the same cutoff distance is less than the NEP. Thus, CGNEP-4:1 can reach a higher calculation speed than the NEP by more than 32 times. Similarly, CGNEP-16:1 can reach a higher calculation speed over 240 times faster than NEP. Although the training datasets of the three CGNEPs with different mapping ratios are all constructed using all-atom calculations, the three CGNEPs have different application situations. As shown in Fig. 17b, the higher mapping ratio CGNEP focuses on large scale calculation, and the reliability is validated by comparing with the frequency predicted by the lower mapping ratio CGNEP. The higher mapping ratio CGNEP sometimes cannot be validated directly by comparing with the frequency predicted by all-atom calculation, because the calculation speed of all-atom calculation is limited for the large size model. Meanwhile, the higher mapping ratio CGNEP has a minimum model size limit for the high discrete property of the CG model, thus, the small size model frequency of all-atom calculation and high mapping ratio CGNEP calculation sometimes cannot be directly compared either. In a sense, a bridge from the nanometer scale to mesoscopic scale to micrometer scale is established successively by the low mapping ratio CGNEP to high mapping ratio CGNEP.

a Computational speeds comparison for the six layers graphene between all-atom NEP (black square point), CGNEP with mapping ratio of 4:1, 16:1, and 64:1 (wine red circular points), all-atom empirical Tersoff with the LJ potential (orange inverted triangular point), TersoffCG potential with the LJ potential using parameters for CG graphene (blue upright triangular point). The mapping ratio of 1:1 denotes the potential for all-atom graphene. b Speed and size application scope of ab initio MD to CGNEP-64:1 MD calculation.

Discussion

The utility of machine learning in periodic complex-interlayer-structured material is explored in this work. A CGNEP for multilayer coarse-grained graphene is obtained by constraining the cutoff regions of descriptor components. The information loss in coarsening process is discussed and divided into intralayer information loss and interlayer information loss. The phenomenon of the same all-atom configuration mapped to several different CG configurations is investigated, which occurs in the CG process of multilayered graphene and is not mentioned in the previous investigations. For multilayered graphene, although the CG process keeps the structure of CG graphene periodic and regular, the information loss is still complex for the new stacking orders induced by the decrease of degree of freedom. Although to some extent the CG graphene is a new material compared with all-atom graphene, the interlayer shear properties from the complex interlayer structures of multilayered CG graphene is still captured by the CGNEP. The statics and dynamics properties of CG graphene predicted by CGNEP match well with all-atom MD calculations. Furthermore, the empirical two-body potential used to describe the interlayer properties of CG graphene is proved to introduce strong anisotropic interlayer shear and alter the interlayer properties. The CGNEP can realize different mapping ratios, preserve the interlayer shear properties and reduce information loss while maintaining high calculation speed compared with empirical CG potentials. Therefore, it is suitable for calculating multilayered mesoscale graphene. The CGNEP accelerates the calculation speed by maximumly more than 1306 times compared with the all-atom NEP by using 1 Nvidia GeForce RTX 4090 GPU card and verifies the feasibility for direct MD calculations of mesoscale models in experiments. The calculation speed can be further accelerated by using multiple GPU cards for parallel computing. A preliminary bridge from the nanometer scale to micrometer scale is established successively by CGNEP with different mapping ratios.

Although the feasibility of larger-mapping-ratio CGNEP is verified, there are still some difficulties in larger-mapping-ratio CGNEP training. The configurations in the training dataset of CGNEP need to be sampled from the MD calculations to ensure that the sampled configurations retain latent mean forces. As the mapping ratio increases, the sampled configurations become much larger, resulting in a reduction in the interlayer displacement for multilayered graphene. Furthermore, the increase in the mapping ratio leads to a lack of structural information, making it much harder to describe the interlayer shear accurately. Although the CG training datasets are mapped directly form all-atom configurations according to the chosen mapping ratios, the high mapping ratio CGNEP still needs to be validated by a lower mapping ratio CGNEP. Therefore, when applying CGNEP for mesoscale problems, several CGNEPs with different mapping ratios still need to be constructed and validated to successively transmit to microscopic scale. The proposed CGNEP focuses on the mechanical properties for the vibration of regular graphene materials, such as multilayered graphene. Thus, the minor deformation of large size graphene membrane cases is mainly considered by the proposed CGNEP. For the non-linear deformation problems, such as non-linear bending problems and fracture problems, there still exist limitations. The vibration frequency of the large-size graphene membrane is dominated by Young’s modulus and interlayer shear modulus but not bending rigidity. Thus, the bending problems and properties are not taken into account for the CGNEP construction, and the limitations do not affect the conclusions presented in this work. For fracture problem, one of the challenges is that the cracks in fractured all-atom configurations are hard to map to CG configurations. Thus, it may be possible for CGNEP to reproduce the fracture strain, but still hard to reproduce the crack behaviors. The non-linear deformation problems need to be investigated in future works. Additionally, because of the proposed CGNEP mainly focuses on the large-scale regular and uniform graphene membrane calculation, the non-periodic boundaries and irregular cases are not considered here. Thus, problems such as behaviors of graphene sheet assembled with intercalated gaps are still unable for CGNEP to reproduce at present. Compared with the empirical CG potential, irregular systems, such as graphene aerogel and buckled graphene, are still a challenge and difficulty for machine learning based CG potential. This problem may be overcome by using CGNEP to describe the intralayer properties and using a proper empirical potential with explicit formula to describe the interlayer properties, which needs further investigations in future works. Furthermore, the temperature influence is not addressed here. The CGNEP is constructed for the room temperature condition, based on the configurations with mean forces under the same temperature in CG training dataset. The effect of configurations under different temperature on thermodynamic consistency and mechanical properties remains an open question. The temperature influence will be taken into consideration in future works.

Finally, noticing that the descriptor types used may affect the prediction accuracy of multilayered CG graphene, the angular descriptor components may need further investigation for the abnormal high interlayer shear modulus in multilayered CG graphene prediction. Except for multilayered graphene, the CGNEP may be used for the coarse-graining of more complexed 2D materials like hexagonal boron nitride and molybdenum disulfide, which may be considered in future works. In practice, the single layer molybdenum disulfide is composed of three atom layers, which significantly affects the computational speed in all-atom MD calculations, the CG molybdenum disulfide may provide much higher computational speed acceleration effect.

Methods

Machine learning in force matching

The force matching method was first proposed to construct all-atom potential from ab initio MD simulations18. This method was later used to build CG potential via the multiscale CG (MS-CG) method20, in which the atomistic-level forces propagate upward in scale to the CG level. However, owing to the decrease in degrees of freedom, several all-atom configurations may be mapped to the same CG configuration, thus making it impossible to obtain a zero error in the force-matching procedure23. Although a nonzero error is inevitable, the mean force of these all-atom configurations can be derived to map with the CG configuration. The final CG potential constructed from the force-matching procedure was proven to be a PMF and is thermodynamically consistent with the original all-atom potential under certain conditions14. Therefore, learning from a set of instantaneous atomic forces act on the instantaneous all-atom configurations to construct a thermodynamically consistent CGMLP can be realized.

The construction of the all-atom MLP involves fitting the PES by minimizing the loss function to predict the potential energy for the given configuration. The negative derivative of the potential energy function U is calculated to obtain the forces. In the all-atom MLP, the simplified loss function Lef, which considers only the energy and force, is written as

where z is the set of trainable parameters, λe and λf are the weights of the energy and force in the loss function, Ncnf is the number of configurations in a batch, and N is the total number of atoms in the configurations. \({{U}}^{{\rm{MLP}}}(k,{\bf{z}})\) is the predicted energy of the MLP with the set of trainable parameters z for the kth configuration, \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{i}^{{\rm{MLP}}}({\bf{z}})\) is the predicted force for the ith atom, Utar(k) is the target energy for the kth configuration in the training dataset, and \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{i}^{{\rm{tar}}}\) is the target force for the ith atom in the training dataset.

For the CGMLP, because of the decrease in the degree of freedom, the CG potential energy is, in fact, a free energy and cannot be mapped directly with the all-atom configuration potential21,23. Compared with the training procedure of the all-atom MLP, the CGMLP needs to predict the energy surface by only using the force information in the dataset. Inspired by the force matching method, the loss function in the CGMLP training procedure is

where vector \({{\bf{z}}}^{*}\) is the set of trainable parameters of CGMLP and NCG is the total number of beads in these CG configurations. \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{i}^{{\rm{CGMLP}}}({{\bf{z}}}^{*})\) is the predicted mean force for the ith CG bead and \({{\boldsymbol{F}}}_{i}^{{\rm{CGtar}}}\) is the target instantaneous CG force for the ith CG bead in the training dataset.

In a CGMLP, the energy surface is completely trained from the force data, which means that the energy surface is built from the mapped forces from the all-atom configurations. The predicted CG forces are subsequently calculated from the negative derivative of the energy function U. The loss function is computed from the predicted CG forces for CG configurations and the mapped CG forces from all-atom configurations. Finally, the energy function U is adjusted via back propagation. Although the training data for the CGMLP are instantaneous forces and instantaneous configurations, the training process finally converges to the mean CG force for the mapped CG configuration because the loss function needs to be minimized.

Training dataset generation

Owing to the decrease in degrees of freedom, the information loss is inevitable, which makes it impossible to obtain a zero error in the force-matching procedure. The CGNEP is actually a PMF. Therefore, the training process is different from the training of the NEP for all-atom calculation purpose. The traditional atomic NEP training requires a relatively small and extensive training dataset to acquire fast training speed to obtain the first NEP. MD simulations are performed via the trained NEP, more configurations are sampled from the MD simulations. Then, the sampled configurations are used to perform single-point DFT calculations to enrich the training dataset. Furthermore, the perturbation method and active learning can be used to further explore the configuration space. In CGNEP training, the training dataset needs to be physical and extensive and should be completely sampled from balanced MD simulations14. Because the perturbation method manually alters the atom position and the cell, it cannot be used to explore the configuration space in CGNEP training because the thermodynamic distribution of the perturbed configuration is not persisted. The active learning in CGNEP needs inverse mapping from the CG configuration to a set of all-atom configurations. Meanwhile, the all-atom configurations need maintaining thermodynamic consistency and a balanced distribution. However, because the existence of information loss, inverse mapping is still a worthy research problem.

CGNEP training details

The original NEP for CG purpose (NEP-CG) and the CGNEP are both trained using the same CG training dataset generated from all-atom calculations for comparison. The radial cutoff radius and angular cutoff radius are set to 10 Å and 8 Å, respectively. The training weight of force is set to 1, and the training weights of energy and virial are both set to 0. The number of neurons in the hidden layer is 150, the batch size is 500, and the total training step is 300,000. To avoid nonphysical status, the Ziegler–Biersack–Littmark (ZBL) potential cutoff radii in both NEP46 and CGNEP are set as 2.5 Å. The ZBL potential is a repulsive two-body potential that can introduce a repulsion force when two beads are too close. The total site energy on central atom i consists of the ZBL potential energy and the NEP potential energy together when the distance between two beads is lower than the ZBL potential cutoff radius but higher than the half of the ZBL potential cutoff radius. The interaction between two beads is completely described by the ZBL potential when the distance between two beads is lower than the half of the ZBL potential cutoff radius. In most cases, the ZBL potential does not work. Adding the ZBL potential here is an empirical choice because the CG configuration sampling from balanced all-atom MD sometimes cannot cover all the possible configurations in CGMD simulations. The remaining input parameters remain at the default values.

MD simulation details

The TersoffCG44 and the corresponding LJ potential using parameters for CG graphene37,44 are used for the empirical potential simulations of CG graphene. The Tersoff potential47 and LJ potential are used for the empirical potential simulations of all-atom graphene. The empirical potential calculations are performed via LAMMPS software package1. The CGNEP and NEP calculations are performed via GPUMD software package4.

The training dataset used to train CGNEP is generated via GPUMD version 3.9.4 with the all-atom potential NEP-C-PBE + D342. All the sampled datasets are obtained from MD simulations at a temperature of 300 K and a timestep of 1 fs, which contain relaxed structures under periodic boundary conditions and tensioned structures. The structures contain graphene from monolayer to 8 layers with vacuum layers in the out-of-plane direction. The relaxed periodic boundary condition structures are first relaxed for 500,000 steps via the NPT ensemble controlling the in-plane pressure near 0 GPa. The structures are then relaxed for 500,000 steps via the NVT ensemble, in which the Nosé‒Hoover thermostat is utilized. The all-atom trajectories and forces are sampled every 10,000 steps and then mapped to CG trajectories and forces. The tensioned structures are first relaxed for 500,000 steps via the NPT ensemble controlling the in-plane pressure near 0 GPa. The structures are then tensioned slowly along the zigzag or armchair direction via the NPT ensemble. The all-atom trajectories and forces during the tension procedures are sampled every 10,000 steps and then mapped to CG trajectories and forces.

For uniaxial tensile simulations in all-atom MD and CGMD calculations, graphene with 6 layers is used to simulate uniaxial tension in the armchair direction and zigzag direction. Tension simulations with the NPT ensemble are carried out to calculate Young’s modulus. A strain rate of \(2\times {10}^{-5}\) ps−1 is set and simulated for 0.5 ns. Young’s modulus can be calculated by fitting the stress‒strain relationship.

For thermal vibration calculations in all-atom MD simulations and CGMD simulations using CGNEP-4:1, energy minimization is first performed with the boundary atoms or beads of the structures fixed to simulate the clamped boundary condition. The remaining free atoms or beads form rectangular regions or circular regions with certain diameters in the middle of the rectangular model. The structures are relaxed for 0.5 ns in the NPT ensemble with a temperature of 300 K and then relaxed for 0.5 ns in the NVT ensemble. Later, the displacements in the out-of-plane direction of the atoms or beads in the top layer are uniformly sampled every 100 fs in the next 1 ns. The vibration modes can be then derived to identify the natural frequency and high-order frequencies.

For thermal vibration calculations in CGMD simulations using CGNEP-64:1, the boundary of the model is fixed to maintain the same as that in the experiment. The timestep for this calculation is set as 20 fs. The model is first relaxed in the NPT ensemble for 60,000 steps and then relaxed in the NVT ensemble for 60,000 steps. The atom displacements are sampled in the next 1,200,000 steps to calculate the frequencies and mode shapes of the model.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Github repository, https://github.com/lmqnuaa/CGNEP.git. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code and training datasets for this study are available in the Github repository and can be accessed via this link https://github.com/lmqnuaa/CGNEP.git.

References

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

Fan, Z. Y., Chen, W., Vierimaa, V. & Harju, A. Efficient molecular dynamics simulations with many-body potentials on graphics processing units. Comput. Phys. Commun. 218, 10–16 (2017).

Wang, H., Zhang, L. F., Han, J. Q. & E, W. N. DeePMD-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Schütt, K. T., Sauceda, H. E., Kindermans, P. J., Tkatchenko, A. & Müller, K. R. SchNet - A deep learning architecture for molecules and materials. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241722 (2018).

Noé, F., Tkatchenko, A., Müller, K. R. & Clementi, C. Machine learning for molecular simulation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 71, 361–390 (2020).

Behler, J. Four generations of high-dimensional neural network potentials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10037–10072 (2021).

Zhang, L. F., Han, J. Q., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. N. Deep potential molecular dynamics: a scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

Schiotz, J. & Jacobsen, K. W. A maximum in the strength of nanocrystalline copper. Science 301, 1357–1359 (2003).

Marrink, S. J., Risselada, H. J., Yefimov, S., Tieleman, D. P. & de Vries, A. H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 7812–7824 (2007).

Zhu, Y. T., Liao, X. Z. & Wu, X. L. Deformation twinning in nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 57, 1–62 (2012).

Lee, B. H., Larentzos, J. P., Brennan, J. K. & Strachan, A. Graph neural network coarse-grain force field for the molecular crystal RDX. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 208 (2024).

Noid, W. G. et al. The multiscale coarse-graining method. I. A rigorous bridge between atomistic and coarse-grained models. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 244114 (2008).

Noid, W. G. et al. The multiscale coarse-graining method. II. Numerical implementation for coarse-grained molecular models. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 244115 (2008).

Campos-Villalobos, G., Subert, R., Giunta, G. & Dijkstra, M. Machine-learned coarse-grained potentials for particles with anisotropic shapes and interactions. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 228 (2024).

Joshi, S. Y. & Deshmukh, S. A. A review of advancements in coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Simul. 47, 786–803 (2020).

Ercolessi, F. & Adams, J. B. Interatomic potentials from first-principles calculations: the force-matching method. Europhys. Lett. 26, 583–588 (1994).

Izvekov, S., Parrinello, M., Burnham, C. J. & Voth, G. A. Effective force fields for condensed phase systems from ab initio molecular dynamics simulation: a new method for force-matching. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 10896–10913 (2004).

Izvekov, S. & Voth, G. A. A multiscale coarse-graining method for biomolecular systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 2469–2473 (2005).

Zhang, L. F., Han, J. Q., Wang, H., Car, R. & E, W. N. DeePCG: constructing coarse-grained models via deep neural networks. J. Chem. Phys. 149, 034101 (2018).

Wang, W. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Coarse-graining auto-encoders for molecular dynamics. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 125 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Machine learning of coarse-grained molecular dynamics force fields. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 755–767 (2019).

Husic, B. E. et al. Coarse graining molecular dynamics with graph neural networks. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 194101 (2020).

Zhang, Z. J. et al. Learning coarse-grained force fields for fibrogenesis modeling. Comput. Phys. Commun. 295, 108964 (2024).

Duschatko, B. R., Vandermause, J., Molinari, N. & Kozinsky, B. Uncertainty driven active learning of coarse grained free energy models. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 9 (2024).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. A roadmap for graphene. Nature 490, 192–200 (2012).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Graphene mechanical oscillators with tunable frequency. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 923–927 (2013).

Smith, A. D. et al. Electromechanical piezoresistive sensing in suspended graphene membranes. Nano Lett. 13, 3237–3242 (2013).

Liang, H. Y., Bu, Y. F., Zhang, J. Y., Cao, Z. Y. & Liang, A. M. Graphene oxide film as solid lubricant. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 6369–6375 (2013).

Dolleman, R. J., Davidovikj, D., Cartamil-Bueno, S. J., van der Zant, H. S. J. & Steeneken, P. G. Graphene squeeze-film pressure sensors. Nano Lett. 16, 568–571 (2016).

Fan, X. G. et al. Graphene MEMS and NEMS. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 154 (2024).

Liu, J. Z., Zheng, Q. S. & Jiang, Q. Effect of a rippling mode on resonances of carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4843–4846 (2001).

Liu, R. M. & Wang, L. F. Nonlinear forced vibration of bilayer van der Waals materials drum resonator. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 145105 (2020).

Zhang, J. C., Liu, R. M. & Wang, L. F. Negative interlayer shear effect on a double-layered van der Waals material resonator. Phys. Rev. B 104, 085437 (2021).

Naskar, S., Shingare, K. B., Mondal, S. & Mukhopadhyay, T. Flexoelectricity and surface effects on coupled electromechanical responses of graphene reinforced functionally graded nanocomposites: a unified size-dependent semi-analytical framework. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 169, 108757 (2022).

Ruiz, L., Xia, W. J., Meng, Z. X. & Keten, S. A coarse-grained model for the mechanical behavior of multi-layer graphene. Carbon 82, 103–115 (2015).

Liu, S. H., Duan, K., Li, L., Wang, X. L. & Hu, Y. J. A multilayer coarse-grained molecular dynamics model for mechanical analysis of mesoscale graphene structures. Carbon 178, 528–539 (2021).

Fan, Z. Y. et al. Neuroevolution machine learning potentials: combining high accuracy and low cost in atomistic simulations and application to heat transport. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104309 (2021).

Fan, Z. Y. et al. GPUMD: a package for constructing accurate machine-learned potentials and performing highly efficient atomistic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 114801 (2022).

Song, K. K. et al. General-purpose machine-learned potential for 16 elemental metals and their alloys. Nat. Commun. 15, 10208 (2024).

Eriksson, F., Fransson, E., Linderalv, C., Fan, Z. Y. & Erhart, P. Tuning the through-plane lattice thermal conductivity in van der Waals structures through rotational (dis)ordering. ACS Nano 17, 25565–25574 (2023).

Liu, Y. L., Xu, Z. P. & Zheng, Q. S. The interlayer shear effect on graphene multilayer resonators. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 59, 1613–1622 (2011).

Shang, J. J., Yang, Q. S. & Liu, X. New coarse-grained model and its implementation in simulations of graphene assemblies. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 3706–3714 (2017).

Zhang, Q. H. et al. Graphene-based nanoelectromechanical periodic array with tunable frequency. Nano Lett. 21, 8571–8578 (2021).

Liu, J. H., Byggmästar, J., Fan, Z. Y., Qian, P. & Su, Y. J. Large-scale machine-learning molecular dynamics simulation of primary radiation damage in tungsten. Phys. Rev. B 108, 054312 (2023).

Tersoff, J. Empirical interatomic potential for carbon, with application to amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2879–2882 (1988).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. U2341230 and 12472016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Q.L.: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing original draft, review, and editing. L.F.W.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, review, and editing. Z.Q.Z.: Formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, validation, review, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions