Abstract

We propose machine learning (ML) models to predict the electron density — the fundamental unknown of a material’s ground state — across the composition space of concentrated alloys. From this, other physical properties can be inferred, enabling accelerated exploration. A significant challenge is that the number of descriptors and sampled compositions required for accurate prediction grows rapidly with species. To address this, we employ Bayesian Active Learning (AL), which minimizes training data requirements by leveraging uncertainty quantification capabilities of Bayesian Neural Networks. Compared to the strategic tessellation of the composition space, Bayesian-AL reduces the number of training data points by a factor of 2.5 for ternary (SiGeSn) and 1.7 for quaternary (CrFeCoNi) systems. We also introduce easy-to-optimize, body-attached-frame descriptors, which respect physical symmetries while keeping descriptor-vector size nearly constant as alloy complexity increases. Our ML models demonstrate high accuracy and generalizability in predicting both electron density and energy across composition space.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic structure calculations, based on Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KS-DFT)1,2,3, serve as the workhorse of computational materials science simulations. The fundamental unknown in KS-DFT calculations is the ground state electron density, from which a wealth of material information — including structural parameters, elastic constants, and material stability (e.g., phonon spectrum) — may be inferred. Compared to more elaborate wave-function-based quantum chemistry methods or simpler electronic structure techniques based on tight-binding, KS-DFT often offers a good balance between physical accuracy, transferability and computational efficiency, leading to its widespread use4.

In spite of its many successes, KS-DFT is often practically limited by its cubic scaling computational cost with respect to the number of simulated atoms. While calculations involving just a few atoms within the computational unit cell can be executed with ease — making high-throughput screening5,6,7 and large-scale materials data repositories possible (e.g., the Materials Project8,9) — larger calculations often need to employ extensive high-performance computing resources or specialized solution techniques10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Thus, routine calculations of a wide variety of important materials problems, e.g., the behavior of defects at realistic concentration17 and simulations of moirè superlattices18, continue to be far from routine, or altogether computationally infeasible, with state-of-the-art KS-DFT implementations. Along these lines, simulations of disordered solids19,20, specifically, multi-element concentrated alloys featuring chemical disorder, represent a significant challenge. Indeed, the computational unit cell required to simulate medium and high entropy alloys at generic compositions can get arbitrarily large, with the number of simulated atoms growing proportionally high. Thus, in spite of the technological relevance of such materials21, direct first-principles evaluation of their material properties over the entire composition space often remains computationally out of reach, unless approximations in KS-DFT calculations or special structural sampling techniques are used22,23,24,25.

Recently, electronic structure predictions using machine learning (ML) have gained a lot of attention and shown promise for various systems. The vast majority of such studies have focused on prediction of the electron density field26,27,28,29,30,31,32, although a number of studies have also carried out predictions of the single and two particle density matrices33,34,35,36. In essence, ML techniques for field prediction serve as surrogate models for KS-DFT, enabling inexpensive evaluation of the electron density and related fields37 from atomic configurations, once trained. The predicted density can be used to compute various other downstream quantities, including the system’s energy32, electronic band diagrams38 or properties of defects39. Some of these ML models use global system descriptors, e.g. strains commensurate with the system geometry37,38, and are trained on KS-DFT data generated using specialized symmetry-adapted simulation techniques40,41,42. The vast majority, however, employ descriptors of the local atomic environment and are trained on KS-DFT data from standard codes, e.g. ones based on plane-waves. The output of the ML model, i.e., the electron density itself, can be represented in different ways. One strategy involves expanding the density as a sum of atom-centered basis functions27,32,43,44,45,46, while another predicts the electron density at each grid point within a simulation cell27,29,47,48,49,50,51. The first strategy is efficient but can be less accurate, as complex electron densities may not always be representable with a small number of basis functions. The second strategy is accurate but computationally expensive, as it requires ML model evaluation over a fine mesh of the simulation cell. However, it is amenable to easy parallelization based on domain decomposition and the evaluation process scales linearly with the system size30,47. Yet another recent approach52 predicts the entirety of the electron density field, using superposition of the atomic densities (SAD) as the input. This approach is efficient, since it can use a convolutional model to predict the electron density over a volume, avoiding tedious grid point-wise inference. This approach is also accurate as it incorporates materials physics through the SAD. However, this method does not inherently accommodate the system’s rotational symmetries, and integrating uncertainty quantification (UQ) features presents a challenge — both aspects that are more readily addressed by the other approaches. Finally, equivariant graph neural networks offer an elegant, end-to-end alternative that learns symmetry-preserving representations directly on atomistic graphs, and have been used for a variety of computational tasks, including electron density27,53 and phonon-spectrum prediction54. In graph-based models, the descriptors are not specified a priori but are learned during training. This flexibility often entails higher inference cost per structure — particularly in high-throughput settings55,56.

While previous studies have carried out ML-based electron density predictions for various molecular systems, pure bulk metals, and some specific alloys26,28,29,30,47,52,57,58, the issue of electron density prediction for arbitrary compositions of concentrated multi-element alloys has not yet been addressed. Indeed, ML techniques have been applied to a variety of other properties of such systems59,60,61,62,63,64, but the ability to predict their electron density, i.e., the fundamental unknown of the material’s ground state, remains an attractive unattained goal. Such predictive capabilities, if realized, may help overcome the aforementioned limitations of KS-DFT in simulating medium and high entropy alloys, and in turn, help accelerate exploration of new materials, e.g., alloys for next-generation microelectronics and novel magnetic storage systems65,66. The key challenge to predicting fields such as the electron density for concentrated multi-element alloy systems is that, due to combinatorial reasons, the number of compositions that need to be sampled for the development of accurate ML models can be very high. Hence, the cost of data generation for developing ML models that work equally well across the composition space also tends to be very high. Therefore, an open question is whether it is possible to produce accurate predictions for the entire composition space of multi-element alloys while limiting the data required to train the ML model. Indeed, compared to low-dimensional material parameters, such as elastic moduli or thermal expansion coefficients67, these data-related challenges can be far more severe for predicting fields.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in using machine learning for high entropy alloys (HEAs), particularly with the aid of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs)68,69. Many of these studies rely on highly exhaustive sets of training data70,71,72. Although these works present accurate MLIPs, the extensive training data required to achieve such accuracy is a limitation. For instance, the Mo-Nb-Ta-V-W training data set from ref. 70 includes single isolated atoms, dimers, pure elements, binary to quinary bcc alloys, equiatomic HEAs, and ordered/disordered structures. Additionally, the dataset covers liquid alloys, vacancies, and interstitial atoms. In71, data for quaternary MoNbTaW is generated via ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) for random alloy compositions at 500 K, 1000 K, and 1500 K, with 2% variation in lattice parameters, and single point calculations involve random alloys with 2% variation in volume and lattice angles. Along the same lines, in ref. 72, in order to develop an interatomic potential for Lithium lanthanum zirconium oxide (LLZO) systems, the training set consisted of three components: (1) elemental materials and scaled structures for Li, La, Zr, and O; (2) structures from first-principles molecular dynamics simulations of LLZO crystals and amorphous phases at various temperatures; and (3) a two-body potential to constrain interatomic distances during molecular dynamics simulations. These different examples serve to highlight the fact that although it is possible to develop accurate interatomic potentials for medium to high entropy alloys, the training set often requires a large amount of static KS-DFT and AIMD simulations. Our work aims at accurately predicting the electron density of HEAs across the composition space while limiting the number of KS-DFT/AIMD simulations required to generate the training data.

One major criticism of machine learning models is their lack of generalization, i.e., their inability to predict beyond the training data accurately. Indeed, the use of a large number of different configurations for generating training data of MLIPs as described above is also related to improving generalizability. In a recent work47, the authors demonstrated that the utilization of data generated at high temperatures and the ensemble averaging nature of Bayesian Neural Networks can enhance the generalization ability of ML-based electron density prediction. This approach yielded highly accurate predictions for bulk aluminum (Al) and silicon germanium (SiGe) systems. More importantly, it exhibited generalization capability by accurately predicting a variety of test systems with structural features not included in the training data, such as edge and screw dislocations, grain boundaries, and mono-vacancy and di-vacancy defects. This model was also shown to be capable of generalizing to systems significantly larger than those used for training and can reliably predict the electron density for multi-million-atom systems using only modest computational resources. The potential of this ML electron density model to generalize to arbitrary alloy compositions is explored in this work. As a starting point, we found that for the SiGe system, learning the binary alloy electron density at a fixed composition allows for reasonably accurate extrapolation to nearby compositions. This raises the question of whether such extrapolation applies to more complex systems, and if so, the minimum data needed to learn across composition space. We explore these questions here, in the context of ternary SiGeSn and quaternary CrFeCoNi systems.

Medium entropy alloy (MEA) and high entropy alloy (HEA) systems provide an opportunity to expose our models to a compositionally complex materials space. Thus, after investigating SiGe, it was a natural choice to extend to the ternary system SiGeSn. Group IV alloys in the Si-Ge-Sn system are of great interest to the optoelectronics industry, due to their utility for bandgap engineering. Notably, the addition of Sn is purported to lower the bandgap and produce an indirect-to-direct bandgap transition whose location is tunable within the SiGeSn composition space73,74. The primary challenge related to the implementation and usage of ternary SiGeSn is that it is difficult to synthesize many of the compositions experimentally75. The SiGe phase diagram shows that Si and Ge are fully soluble in each other76,77. In contrast, Sn is barely soluble in Si or Ge; it can be difficult to obtain compositions above a few percent. Despite this, recent research developments have continued to push the limit of Sn incorporation78. In light of the experimental progress towards synthesizing such systems, there is interest in predicting the composition windows to aim for with respect to obtaining desired property targets, and this continues to be an active area of research79,80 — thus motivating our choice. In addition to SiGeSn, we also wished to test how our methodology performs against a more challenging bulk metallic alloy system. Given the Cantor alloy’s status as the most well-studied HEA to date, we selected a quaternary Cantor alloy variant CrFeCoNi, and explored it across composition space. We also investigated a more traditional quinary HEA, AlCrFeCoNi, near equiatomic composition, for the sake of completeness. The quaternary alloy system is much easier to experimentally synthesize, as it forms solid solution phases more readily. Its mechanical properties — notably the high ductility and fracture toughness — have led to a large volume of research studies focusing on this system81. Furthermore, CrFeCoNi has also received interest in the field of nuclear materials for its high damage tolerance under irradiation; for instance, defect growth in CrFeCoNi is over 40 times slower compared to pure Ni82. Interestingly, despite the vast quantity of HEA research, the overwhelming majority of studies have tended to solely focus on equiatomic compositions (such as Cr0.25Fe0.25Co0.25Ni0.25). This is a bit surprising, considering that the idea of exploiting the high degree of freedom in compositional space for improved property design has been around since the beginning of the field. Yet, as case studies have emerged demonstrating that improved mechanical properties can be obtained with non-equiatomic HEA systems, interest in this direction has grown. Currently, there exists a great deal of research momentum towards moving beyond equiatomic compositions and exploring material property maps across composition space, ultimately motivating our choice of this alloy system.

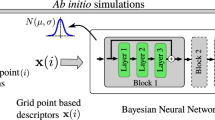

To address these complex alloy systems, we employed the following three key strategies to achieve highly accurate and reliable predictions across composition space while minimizing the required training data. The schematics of our proposed ML model is shown in Fig. 1.

The process begins with calculating atomic neighborhood descriptors D(i) at each grid point, i, for the provided atomic configuration snapshot in the training data. A Bayesian Neural Network is trained to provide a probabilistic map from the atomic neighborhood descriptors D(i) to the electronic charge density and corresponding uncertainty measure at grid point, i. Application of the trained model to generate charge density predictions for a given new query configuration requires: descriptor generation for the query configuration, forward propagation through the Bayesian Neural Network, and aggregation of the point-wise charge density predictions ρ(i) and uncertainty values to obtain the charge density field ρ and uncertainty field, respectively.

First, we developed an uncertainty quantification (UQ)-based Active Learning (AL) approach for the electron density to select the most informative compositions and add them to the training data in each iteration, aiming to minimize the overall training data. The UQ capability of the Bayesian Neural Network is utilized to efficiently quantify uncertainty; hence, this AL approach is referred to as Bayesian Active Learning (Bayesian-AL). The compositions corresponding to the highest uncertainty are considered the most informative for the next iteration of AL.

Second, we introduced novel descriptors for which the descriptor-vector size does not increase significantly with the number of alloy elements. The sizes of many existing descriptors rapidly increase with the number of distinct chemical elements in the system, which is a key challenge for multi-element alloy systems83,84. Our descriptors are position vectors in a body-attached frame and incorporate species information through the atomic number. Thus, they do not depend on the number of distinct chemical elements that may be present, for a fixed number of atoms in the neighborhood. Furthermore, our descriptors also facilitate the selection of the optimal set of descriptors.

Third, we trained our model on the difference between total densities and atomic densities, rather than solely on total densities. Observing that a model trained just on the superposition of atomic densities (SAD) can obtain nearly 85% accuracy in density prediction52, we presumed that using the difference between total densities and atomic densities would allow for a higher resolution description of the chemical bonding in our model. In other words, if the complexity of the quantum-mechanical chemical bonding environment contributes about only about 15% accuracy overall, then training the model on the difference between total and atomic densities should help to improve its sensitivity to the fundamental chemistry present in a given system. In light of this, we have trained a separate ML model to predict the difference between the electron density and the SAD, which we refer to as the δρ ML model. This model is found to be more accurate in energy predictions for CrFeCoNi systems (which involve elements with hard pseudopotentials and semi-core states), in line with the above reasoning.

These three methodological innovations ultimately resulted in highly accurate ML models, generalizable across the full composition space of the respective alloy systems, as demonstrated in the following Results section. Additional results involving a high entropy quinary system (AlCrFeCoNi) are presented in the Supplementary Materials. We also note that our contribution is quite exhaustive, in that a whole plethora of ML models — involving different materials systems (i.e., binary, ternary, and quaternary alloys), different levels of Bayesian Active Learning, different levels of tessellation-based training, and different predicted quantities (i.e., ρ and δρ based models) — were carefully developed and extensively tested. The high-quality predictions obtained by our ML models give us confidence that the techniques described above can be easily extended to other bulk high-entropy materials, or emergent low-dimensional functional materials featuring chemical complexity and disorder, e.g., high entropy MXenes85,86 and high entropy 2D transition metal dichalcogenides87.

Finally, when required, we accelerated the data generation process by judiciously integrating ML interatomic potentials with KS-DFT calculations, in lieu of full ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. This further accelerates the development of our ML models.

Results

This section evaluates the accuracy of the proposed machine learning (ML) model in comparison to the ground-truth, i.e., KS-DFT. Since the focus of this work is on electron density prediction for alloys, three systems have been considered as prototypical examples: a binary alloy — SixGe1−x, a medium entropy ternary alloy — SixGeySn1−x−y, and a high entropy quaternary alloy — CrxFeyCozNi1−x−y−z. Though the developed ML framework should be applicable to any alloy with any number of elemental species, we present results for the aforementioned technologically important alloys73,75,76,78,81,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98. The error in electron density prediction is measured using two metrics: Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) and relative L1 error (% L1)28 (see Supplementary Material for further details).

At the onset, we made an attempt to develop an ML model that is accurate for all compositions of a binary alloy. It is found that a model trained with equiatomic SiGe (SixGe1−x with x = 0.5) achieves high accuracy in the vicinity of the training composition (x = 0.5), as illustrated in Fig. 2a. However, the error grows as the distance between the training and testing compositions increases in the composition space. If only two compositions that have the highest error are added to the training data the accuracy increases across the entire composition space, as shown in Fig. 2b. This experiment demonstrates that retraining the ML model with the addition of a few compositions with the highest error enables accurate prediction across the entire composition space. However, as the number of alloying elements increases, the number of possible compositions in the composition space grows rapidly, making it challenging to simulate all compositions through KS-DFT. Therefore, the errors for all compositions will not be available to identify the most erroneous compositions to include in the next round of training. To address the aforementioned challenge, we propose two systematic iterative training approaches for selecting optimal compositions for training the model: (i) an Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)-based Active Learning technique (referred to as Bayesian Active Learning) and (ii) a Tessellation-based iterative training technique.

a Error in ρ prediction for SixGe1−x, where the model was trained using only x = 0.50 and tested on all x ≠ 0.50. b Error in ρ prediction for SixGe1−x, where the model was trained using x = 0, 0.50, 1.00 and tested at other compositions. The error across the entire composition space reduces significantly with the addition of only two extra training compositions.  : Training,

: Training,  : Testing.

: Testing.

Minimizing the training data: Bayesian active learning and tessellation

In this section, we compare the performance of the Bayesian Active Learning approach and the Tessellation-based iterative training approach. The Tessellation approach involves a systematic, progressively refined discretization of the composition space to obtain training compositions. In contrast, the Bayesian Active Learning uses uncertainty measures to identify the most informative training compositions, thereby bypassing the need for knowledge of errors at all compositions.

The training compositions obtained through progressively refined tessellation-based discretization of the composition space are shown in Fig. 3. For the tessellation-based ML models, T1, T2, and T4 contain 3, 6, and 15 training compositions for ternary (e.g., SiGeSn) systems, and 4, 11, and 34 training compositions for quaternary (e.g., CrFeCoNi) systems, respectively.

The red dots show training compositions. The top row shows compositions for the ternary (SiGeSn) system and the bottom row shows compositions for the quaternary (CrFeCoNi) system. Note that we train the model T4 with the 4th iteration of tessellation, because the training compositions in the third iteration exclude available training compositions from the second iteration. The star depicts an additional point considered in the quaternary T2 model to capture information in the center, approximating the octahedron in the second tessellation of the tetrahedron.

In the case of Bayesian Active Learning, we iteratively add alloy compositions to the training set. For the ternary system, Bayesian AL starts with three training compositions as shown by white circles in Fig. 4a. This model is referred to as AL1, and the errors in the ρ and energy for model AL1 are shown in Fig. 4a, b. Based on the Uncertainty measure, shown in Fig. 4c, three additional training compositions corresponding to the highest uncertainty are chosen and are added to the training set. The model trained with these six training compositions, is referred to as AL2 and the errors in the ρ and energy for model AL2 are shown in Fig. 4d, e. Further details on these errors are given in Fig. S6d, e of the Supplementary Material. Similarly, for the quaternary system, the training compositions used in Bayesian Active Learning models AL1, AL2, and AL3 are shown in Fig. 5. Note that the errors in the electron density are computed for all compositions to illustrate the variation across the composition space. Although all compositions are simulated for error calculation, only a fraction of them are used for training, as shown in Figs. 3 and 5. Detailed explanations of both the Bayesian Active Learning and Tessellation approaches can be found in the Methods section.

a NRMSE across the composition space after 1st iteration of Active Learning, termed as AL1, trained using only 3 pure compositions shown using white circles. b Energy prediction error for model AL1 with 3 pure compositions. c Epistemic Uncertainty in ρ prediction across composition space after prediction with model AL1. Query points (additional training points) for the next iteration of Bayesian Active Learning are selected based on the highest uncertainty regions shown in f. d NRMSE across the composition space after the 2nd iteration of Active Learning. 3 additional training points are added as per the uncertainty contour in subfigure, c. This model is termed as AL2. We observe that the NRMSE is low and consistent across the composition space, showing the effectiveness of query point selection through uncertainty. e Error in energy prediction across composition space. The unit of energy error is Ha/atom. The energy error is within chemical accuracy across the composition space. f Epistemic Uncertainty in ρ prediction across composition space after prediction with model AL2. This figure uses the same colorbars for AL1 and AL2 models. Refer to Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Material for figure with distinct colorbars.

Left: 4 training compositions used for model AL1, Middle: 10 training compositions used for model AL2, Right: 20 training compositions used for model AL3. Black spheres indicate compositions on the vertex, blue spheres indicate compositions on edges, green spheres indicate compositions on faces, and red spheres indicate compositions inside the tetrahedron.

For the ternary SiGeSn alloy, errors in the electron density across the composition space for each iteration of both approaches are presented in Fig. 6. The initial iteration for both the Bayesian Active Learning (AL1) and Tessellation (T1) approaches is identical, as they each begin with 3 training compositions containing the pure elements silicon, germanium, and tin. Bayesian Active Learning requires only 6 training compositions (in AL2) to achieve slightly greater accuracy compared to the 15 needed by the Tessellation approach (in T4). The Tessellation approach performs well, requiring only 15 compositions to accurately predict across the composition space. However, the AL approach demonstrates superior efficiency compared to the systematic Tessellation method. The error in energy for each iteration of both approaches is shown in Fig. 7. The Bayesian Active Learning based model trained on 6 compositions (AL2) is enough to obtain chemically accurate energy predictions. Thus, for the ternary system, Bayesian Active Learning achieves a reduction by a factor of 2.5 in the cost of data generation compared to Tessellation.

Right side plots are a magnified version of the left side plots. The magnified region is indicated by a black dashed line in the left plot. The training compositions for Tessellation models are shown in Fig. 3. The training compositions for Active Learning models of SiGeSn are shown in Fig. 4. The training compositions for Active Learning models of CrFeCoNi are shown in Fig. 5.  : Maximum NRMSE (AL),

: Maximum NRMSE (AL),  : Average NRMSE (AL),

: Average NRMSE (AL),  : Maximum NRMSE (T),

: Maximum NRMSE (T),  : Average NRMSE (T).

: Average NRMSE (T).

Top left: Bulk 64-atom SiGeSn results across composition space, logarithmic scale to emphasize the order of magnitude. Top right: Magnified version of the SiGeSn results, linear scale to emphasize the specific values. Bottom left: Bulk 32-atom CrFeCoNi results across composition space, logarithmic scale. Bottom right: Magnified version of the CrFeCoNi results, linear scale. The dashed lines are present to illustrate the magnification of the magnified plots. Standard deviation bars are shown in each of the plots. The training compositions for Tessellation models are shown in Fig. 3. The training compositions for Active Learning models of SiGeSn are shown in Fig. 4. The training compositions for Active Learning models of CrFeCoNi are shown in Fig. 5. : Maximum Error (AL),

: Maximum Error (AL),  : Average Error (AL),

: Average Error (AL),  : Maximum Error (T),

: Maximum Error (T),  : Average Error (T).

: Average Error (T).

Similarly, the results for the quaternary alloy, CrFeCoNi, are shown in Fig. 6. The initial iteration for both the Bayesian Active Learning (AL1) and Tessellation (T1) approaches is identical, as they each begin with 4 training compositions containing the pure elements chromium, iron, cobalt, and nickel. Bayesian Active Learning requires only 20 training compositions (in AL3) to achieve much better accuracy compared to the 34 needed by the Tessellation approach (in T4). The error in energy for each iteration of both approaches is shown in Fig. 7. For Bayesian Active Learning, 20 compositions (AL3) are sufficient to achieve energy predictions as accurate as those obtained with the Tessellation approach using 34 compositions (T4). These results for the quaternary system further demonstrate that while Tessellation is a reasonable approach, Bayesian Active Learning offers a significant advantage, reducing the cost of data generation by a factor of 1.7 compared to Tessellation. Even though only 34 out of 69 points are on the boundary, the training points in AL2 and AL3 for the quaternary system are mostly positioned on the boundary of the composition space, with the exception of one point, see Fig. 5. This suggests that the points on the boundaries contain more valuable information for the ML model to learn from.

Generalization

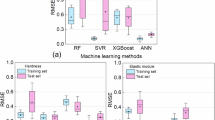

To showcase the generalization capabilities of the model, we tested the model on various test cases that are not used in the training and often significantly different from the training data, including (i) systems with compositions not used in training, (ii) systems with vacancy defects, (iii) ‘checkerboard’ systems with clusters of atoms from the same species. For all these test systems, we assess the error in density prediction, as well as the error in energy obtained by postprocessing the predicted densities. Relative L1 errors in the prediction of ρ for these testing cases are shown in Fig. 8 for both ternary and quaternary alloys. For the ternary alloy, the model was trained on 64-atom systems, whereas for the quaternary alloy, the model was trained on 32-atom systems.

a NRMSE in electron density for the pristine 32-atom CrFeCoNi data set for the AL2 model trained on δρ. Note that the order of magnitude of the colorbar is 10−2. b Corresponding average error in energy at test compositions for the pristine 32-atom CrFeCoNi data set, in terms of Ha/atom. Note that the order of magnitude of the colorbar is 10−3.

Generalization across composition space

The prime objective of the ML model is to accurately predict electron density across the composition space while using only a small fraction of compositions for training. If successful, this approach would allow for the estimation of any property of interest for a given alloy at any composition. By leveraging fast ML inference, the vast composition space of multi-principal element alloys can be explored much more quickly than with conventional KS-DFT methods.

To demonstrate the generalizability of the model beyond the training composition, the electron density for a 64-atom SiGeSn system is predicted across 45 distinct compositions spanning the entire composition space. The AL2 model uses only 6 out of these 45 SiGeSn compositions for training. The prediction errors for the 64-atom system are shown in Figs. 4 and S6 of the Supplementary Material). For better readability, the values of the density and energy errors are shown for each composition in Fig. S10 of the Supplementary Material. The average energy error is 4.3 × 10−4 Ha/atom, which is well within chemical accuracy. To evaluate compositions that are not feasible to simulate with the 64-atom system, additional test compositions were generated using a 216-atom SiGeSn system, as shown in Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material. The errors in the electron density and energy for the 216-atom SiGeSn system are presented in Fig. S4 of the Supplementary Material. The energy errors for these systems too are well within chemical accuracy, on average. Additionally, the errors in the electron density and energy for these 216-atom systems are of the same magnitude as those for the 64-atom systems, indicating generalizability to systems of larger size.

The generalizability of the ML model beyond training compositions is also tested for the quaternary system, CrFeCoNi, by evaluating the error in electron density predictions across the composition space, as shown in Fig. 9(a). Note that the AL2 model uses only 10 out of these 69 CrFeCoNi compositions for training. The error in the energy obtained from the predicted electron density for CrFeCoNi system across the composition space are shown in Fig. 9(b). The AL3 model displays further improvement; for better readability, the values for energy errors are shown in Fig. S11 of the Supplementary Material. The average energy errors (2.3 × 10−3 Ha/atom) are very close to chemical accuracy, and “worst case” predictions (3.5 × 10−3 Ha/atom) are only slightly worse. A visualization of the difference between the KS-DFT-calculated and ML-predicted electron densities for the SiGeSn and CrFeCoNi systems are shown in Fig. 10.

Top: Accuracy in charge density predictions, in terms of relative L1. Middle: Accuracy in energy predictions obtained from post-processing the charge densities, in terms of Hartree/atom. Bottom: Accuracy in energy predictions, presented in terms of Hartree/electron. Note that Middle and Bottom plots have logarithmic scale. The SAD baseline and AlCrFeCoNi system are discussed in Supplementary Material. Top:  : Maximum Error,

: Maximum Error,  : Average Error. Middle:

: Average Error. Middle:  : Maximum Error,

: Maximum Error,  : Average Error,

: Average Error,  : 1 × 10−2,

: 1 × 10−2,  : 1 × 10−3,

: 1 × 10−3,  : 1 × 10−4. Bottom:

: 1 × 10−4. Bottom:  : Maximum Error,

: Maximum Error,  : Average Error,

: Average Error,  : 1 × 10−2,

: 1 × 10−2,  : 1 × 10−3,

: 1 × 10−3,  : 1 × 10−4.

: 1 × 10−4.

Electron densities (a, d) calculated by KS-DFT and b, e predicted by ML, and the Error (absolute difference) between them (c, f) for SiGeSn (a–c) and CrFeCoNi (d–f), using the AL2 model. Subplots (a–c) correspond to a 64-atom Si12.5Ge37.5Sn50 simulation cell at 2400K. Subplots (d–f) are a 32-atom simulation cell at 5000K corresponding to Cr25Fe25Ni25Co25δρ model, respectively. The values below the snapshots refer to the iso-surface values. The visualization is done with the VESTA147 software.

The aggregated electron density and energy errors for the SiGeSn and CrFeCoNi systems are shown in Fig. 8. On average, the errors in energy per atom for the quaternary systems are somewhat higher compared to the predictions of the ternary alloy cases. However, the atoms involved in the ternary system also have significantly more electrons per atom. Upon normalizing the energy errors in terms of the number of electrons in the simulation, the energy errors for the quaternary system (ρ − SAD or δρ model) is found to be comparable to the errors for ternary systems (of the order of 10−4 Ha/electron, on average), as shown in Fig. 8. Overall, the low errors in prediction of electron density and energy for binary, ternary and quaternary alloy across the entire composition space demonstrate the generalization capacity of the proposed ML model.

Generalization to systems with defects

We assess the performance of the ML model on systems containing localized defects, such as mono-vacancies and di-vacancies, even though the training was conducted exclusively on defect-free systems. The electron density fields predicted by the ML model match remarkably well with the KS-DFT calculations, with error magnitudes for defective systems comparable to those for pristine systems, as shown in Fig. 8. Further details on the match between the ML-predicted and KS-DFT-obtained ρ fields are provided in Fig. S7 of the Supplementary Material. In addition to accurately predicting electron density, the energy errors remain within chemical accuracy. Note that for these systems, the atomic configurations away from the defects are quite close to the equilibrium configuration (see Fig. S7 of the Supplementary Material), resulting in very low errors in the ML predictions away from the defects. Consequently, the overall error remains low.

Generalization to handcrafted systems featuring species segregation

In multi-element alloys, species segregation naturally occurs, leading to the formation of element-enriched regions within the alloy75,99. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the model for these systems. Towards this, handcrafted systems featuring species segregation are created. Cubic simulation cells of 64 and 216 atoms occupying diamond lattice sites are divided up into smaller cubic sub-regions, i.e. either 8 bins (2 × 2 × 2) for the 64-atom and 216-atom cells, or 27 bins (3 × 3 × 3) for the 216-atom cell. Elemental labels are then assigned to each bin, such that no two neighboring bins contain the atoms of the same element, with periodic boundaries taken into consideration as well. In the 8-bin case, three compositions were considered: \({{\rm{Si}}}_{0.25}{{\rm{Ge}}}_{0.375}{{\rm{Sn}}}_{0.375}\), \({{\rm{Si}}}_{0.375}{{\rm{Ge}}}_{0.25}{{\rm{Sn}}}_{0.375}\), and \({{\rm{Si}}}_{0.375}{{\rm{Ge}}}_{0.375}{{\rm{Sn}}}_{0.25}\). In the 27-bin case, just the equiatomic SiGeSn case was considered (e.g. \({{\rm{Si}}}_{0.33}{{\rm{Ge}}}_{0.33}{{\rm{Sn}}}_{0.33}\)). The errors in electron density predicted by the ML model as well as in the corresponding energy for these handcrafted systems featuring species segregation, are shown in Fig. 8, i.e., ‘checkerboard SiGeSn’. The errors for these unseen systems featuring species segregation are quite low, asserting the generalizability of the ML model.

Comparison of ML Models Trained on ρ and δ ρ

The performance of the ML model on the CrFeCoNi system lagged behind that of the SiGeSn system in terms of energy predictions as shown in Fig. 8 (middle and bottom). In order to address that, we trained a separate ML model, only for the quaternary system CrFeCoNi. This model predicts the δρ, which is the difference between the electron density ρ and the superposition of atomic densities (SAD), denoted ρSAD, i.e., δρ = ρ − ρSAD. We refer to this ML model as the ‘δρ ML model’ to distinguish it from the ML model described previously. To obtain the ρ while using the δρ model, the ρSAD needs to be added to its prediction. The energy computation through post-processing of ρ remains the same. The δρ ML model performs better than the ML model for both the density and energy predictions, as shown in Fig. 8. The error in the energy predicted by the δρ ML model is presented in Fig. 9 for various compositions of the CrFeCoNi system. The δρ ML model reduced the maximum error in energy by a factor of two, compared to the ρ ML model.

In the following, we explain the superior performance of the δρ ML model for the CrFeCoNi system. In contrast to the quadrivalent, softer Si, Ge, and Sn pseudopotentials that were used in producing the electron density data of the SiGeSn systems, the pseudopotentials for Cr, Fe, Co, and Ni all included semi-core states and were significantly harder. Each pseudoatom of the elements involved in the CrFeCoNi system involved 14 or more electrons, and CrFeCoNi calculations generally involved a mesh that was twice as fine as the SiGeSn systems. Unlike the valence electrons, the semi-core states are not as active in bonding, yet the individual densities of these atoms have large contributions from their semi-core states. Thus, even in the presence of chemical bonding, as it happens in the alloy, the electron density field tends to concentrate around the nuclei, due to which it can be well approximated in terms of the superposition of the atomic densities, i.e., ρSAD. Hence, by training the ML model on the difference, i.e., δρ = ρ − ρSAD, better accuracy can be achieved. These issues pertaining to semi-core states can become particularly important while computing energies from the electron density. The ground-state KS-DFT energy has a large contribution from the electrostatic interactions100, and the δρ ML model captures the contribution to this energy from the atomic sites much more accurately, since the atomic densities are better represented, particularly when semi-core states are present. This claim is further supported by Fig. 11 where we compared the electrostatic energy field \({\mathcal{E}}=(\rho +b)\phi\), as calculated from the (ρ-based) ML model and the δρ ML model for a CrFeCoNi system. Here, b denotes the nuclear pseudo charge field and ϕ is the electrostatic potential that includes electron-electron, electron-nucleus, and nucleus-nucleus interactions. The δρ ML model is seen to perform significantly better in terms of the error in the electrostatic energy field, particularly near the nuclei.

a Electrostatic energy field \({\mathcal{E}}=(\rho +b)\phi\) for the KS-DFT calculation. Here ρ is the electron density, b denotes the nuclear pseudo charge field and ϕ is the electrostatic potential that includes electron-electron, electron-nucleus and nucleus-nucleus interactions. b The errors in the calculated electrostatic energy predicted field obtained through the (ρ-based) ML model. c The errors in the calculated electrostatic energy predicted field obtained through the δρ ML model. Most errors are seen to be concentrated around the atomic nuclei and are significantly reduced in the case of the δρ ML model. ML predictions are carried out using the AL2 model.

Discussion

We have presented a machine learning (ML) framework that accurately predicts electron density for high entropy alloys at any composition. The model demonstrates strong generalization capabilities to various unseen configurations. It efficiently represents the chemical neighborhood, increasing modeling efficiency, and trains on an optimal set of the most informative compositions to reduce the amount of data required for training. The electron density predicted by ML can be postprocessed to obtain energy and other physical properties of interest. Currently, a generally accepted rule-of-thumb for quantum mechanical calculations is to aim for chemical accuracy, i.e., a prediction error of 1.6 mHa/atom (1 kcal/mole) or less, in the total energies101,102,103,104,105. This is often crucial for making realistic chemical predictions, especially regarding thermochemical properties like ionization potentials and formation enthalpies. On average, for all the alloy systems studied here, our ML model demonstrated accuracies that met or were very close to achieving this threshold (see Fig. 8), thus making them accurate enough for the subsequent tasks they were applied to. Thus, the proposed ML model allows for the accelerated exploration of the complex composition space of high entropy alloys. Further improving the energy predictions of our model to enable routine calculations of quantities such as phonon spectra, which require more accurate energies106 remains the scope of future work. We also note that this appears to be an open area of research across a variety of ML-based atomistic calculation models107.

The ML model employs a Bayesian neural network (BNN) to map atomic neighborhood descriptors of atomic configurations to electron densities. A key challenge for multi-element alloys is that the size of the descriptor vector increases rapidly with the number of alloying elements, necessitating more training data and larger ML models for accurate prediction. To address this, we propose body-attached frame descriptors that maintain approximately the same descriptor-vector size, regardless of the number of alloying elements. These proposed descriptors are a key enabler of our work. Moreover, they are easy to compute and inherently satisfy translational, rotational, and permutational invariances, eliminating the need for any handcrafting. Furthermore, obtaining the optimal number of descriptors required is simpler for these descriptors compared to the few proposed earlier in the literature.

The composition space of multi-element alloys encompasses a vast number of compositions, demanding extensive ab initio simulation data to develop an ML model that is accurate across the entire space. To address this challenge, we developed a Bayesian Active Learning approach to select a minimal number of training compositions sufficient for achieving high accuracy throughout the composition space. This approach leverages the uncertainty quantification (UQ) capability of a Bayesian Neural Network, generating data only at the compositions where the model has the greatest uncertainty, thereby minimizing the cost of data generation.

We generate first principles data at various high temperatures, as thermalization helps produce data with a wide variety of atomic configurations for a given composition, enhancing the generalizability of the ML model beyond equilibrium configurations. Additionally, the Bayesian Neural Network enhances generalization through ensemble averaging of its stochastic parameters. The generalization capability of the ML model is demonstrated by its ability to accurately predict properties for systems not included in the training set, such as unseen alloy compositions, systems with localized defects, and systems with species segregation. The errors in energy for all test systems remain well within or close to chemical accuracy.

The proposed model demonstrates remarkable accuracy for binary, ternary, and quaternary alloys, including SiGe, SiGeSn, and CrFeCoNi, all of which are of technical importance. However, the proposed framework can be applied to any alloys containing a large number of constituent elements. Although our examples involved bulk systems, the models also extend to low-dimensional materials featuring chemical complexity and disorder. Furthermore, the model can be applied to predict other electronic fields. For the quaternary alloy, we develop a separate ML model to learn ρ − ρSAD instead of ρ, enabling a more accurate representation of the density of semi-core states and significantly enhancing the overall accuracy of ρ and energy predictions.

Overall, the proposed model serves as a highly efficient tool for navigating the complex composition space of high entropy alloys and obtaining ground-state electron density at any composition. From this ground-state electron density, various physical properties of interest can be derived, making the model a powerful resource for identifying optimal material compositions tailored to specific target properties. Future work could focus on developing a universal ML framework that utilizes the proposed descriptors and functions accurately across diverse molecular structures and chemical spaces.

Methods

The methodology implemented in this work can be divided into six subsections: (1) the training data and test data generation; (2) the machine learning map for charge density prediction; (3) the atomic neighborhood descriptors; (4) the implemented Bayesian Neural Network; (5) Bayesian optimization and uncertainty quantification; (6) postprocessing and materials property analysis. In the following section, our methodology choices for each area are thoroughly discussed.

Data generation

To generate the electron density data, we use SPARC (Simulation Package for Ab-initio Real-space Calculations), which is an open-source finite difference-based ab initio simulation package100,108,109,110. We use the optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt (ONCV) pseudo-potentials111 for all the elements. For Si, Ge, and Sn pseudopotentials only the valence electrons are included, while for Cr, Fe, Ni, and Co semi-core states are also included. We use the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA) as the exchange-correlation functional112.

Real-space meshes of 0.4 Bohr and 0.2 Bohr were used for the SiGeSn and CrFeCoNi systems, respectively. These values were obtained after performing convergence testing on the bulk systems, and guaranteed convergence of the total energy to within 10−4 Ha/atom. Periodic-Pulay mixing113 was employed for self-consistent field (SCF) convergence acceleration, and a tolerance of 10−6 was used. Only the gamma point in reciprocal space was sampled, as is common practice for large-scale condensed matter systems. Fermi-Dirac smearing with an electronic temperature of 631.554 Kelvin was used for all the simulations.

The atomic coordinate configurations that were fed into SPARC were obtained via sampling from high-temperature molecular dynamics trajectories — either ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) calculations or classical molecular dynamics (MD) using state-of-the-art machine learning interatomic potentials. To ensure comprehensive coverage of local atomic environments and to improve model generalizability, simulations were performed at elevated temperatures, consistent with our prior observations47. For each composition, atomic species labels were randomly assigned to lattice sites consistent with the target stoichiometry, and multiple distinct seeds (orderings) were used as starting points for AIMD/MD trajectories. This procedure yields ensembles that, for the datasets used in this work, correspond to fully chemically disordered alloys. Additionally, we generated targeted “hand-crafted” configurations featuring, for example, species segregation and defects which were used in generalizability tests (described in detail in the Supplementary Materials).

For the SiGeSn system, AIMD was performed, as per the methodology of our previous work47. However, AIMD simulations can be time-consuming as one has to perform an electronic minimization at each MD step. The increased number of electrons required to model the CrFeCoNi system motivated an alternative approach. In order to alleviate the computational burden of configurational sampling for the CrFeCoNi system, we leveraged classical molecular dynamics (MD) instead of AIMD. The interatomic potential selected for the MD runs is the Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet), a universal machine-learned potential implemented in the (Materials Graph Library) MatGL python package114,115. The MD simulations are run through the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) interface built into MatGL. After extracting snapshots from the MD trajectory, a single electronic minimization step is performed to obtain the electron densities. MD with machine learned interatomic potentials is orders of magnitude cheaper compared to AIMD, and the subsequent electronic minimization tasks (for given system snapshots) can be conveniently parallelized. This approach facilitates rapid data generation for various configurations without any quality loss for the electron density training data.

The compositions for which data was generated are shown in Fig. S1 for the SiGeSn system and in Fig. S2 for the CrFeCoNi system. For more details regarding the data generation, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

Machine learning map for charge density prediction

Our ML model maps the atom coordinates \({\{{{\bf{R}}}_{I}\}}_{I = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{a}}}}\) and species (with atomic numbers \({\{{{\bf{Z}}}_{I}\}}_{I = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{a}}}}\)) of the atoms, and a set of grid points \({\{{{\bf{r}}}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{grid}}}}\) in a computational domain, to the electron density values at those grid points. Here, Na and Ngrid refer to the number of atoms and the number of grid points, within the computational domain, respectively. We compute the aforementioned map in two steps. First, given the atomic coordinates and species information, we calculate atomic neighborhood descriptors for each grid point. Second, a Bayesian Neural Network is used to map the descriptors to the electron density at each grid point. These two steps are discussed in more detail subsequently.

Atomic neighborhood descriptors

One major challenge in predicting electron density for multi-element systems is the rapid increase in the number of descriptors as the number of species grows, which hampers both efficiency and accuracy. For example, the scalar product descriptors developed in ref. 47 increases rapidly with the number of species. Additionally, descriptors should be simple, easy to compute and optimize, and avoid manual adjustments like selecting basis functions. To address these issues, we propose a novel descriptor that utilizes position vectors to atoms represented in body-attached reference frames. The proposed descriptor overcomes the scaling issue faced by the scalar product47, tensor invariant based29, and SNAP116 descriptors, since the number of position vectors needed depends only on the number of atoms in the atomic-neighborhood but is independent of the number of species.

We encode the local atomic neighborhood using descriptors \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{i}\). Descriptors are obtained for each grid point \({\{{{\bf{r}}}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{N}_{{\rm{grid}}}}\) in the computational domain. Following the nearsightedness principle28,117,118, we collect M number of nearest atoms to the grid point i to compute the descriptors for grid point i. This is analogous to setting a cutoff radius for obtaining the local atomic neighborhood. The descriptors for the grid point i are denoted as \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4M}\). For the jth atom, descriptors are given as:

where (r10, r20, r30) are the coordinates of the position vector r of atom j with respect to a global reference frame at the grid point i. j varies from 1 to M. The basis vectors for the global reference frame are denoted as \({{\bf{e}}}_{1}^{0},{{\bf{e}}}_{2}^{0},{{\bf{e}}}_{3}^{0}\).

The above descriptors are not frame invariant and hence would change under rotation of the computational domain. Since the electron density is equivariant with respect to the given atomic arrangement, it is imperative to maintain equivariance. To address this issue, we propose to determine a unique local frame of reference for the atomic neighborhood and express these coordinates in that local reference frame. In previous works, such a local frame of reference is constructed using two119 or three32 nearest atoms. However, as mentioned in ref. 119, these local frame descriptors exhibit non-smooth behavior when the order of nearest neighbors is altered or when there is a change in the nearest neighbors themselves. To address this issue, in this work, we obtain the local frame of reference using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of an atomic neighborhood consisting of M atoms. We apply PCA to position vectors of these atoms and obtain principal directions, which yield an orthonormal basis set e1, e2, e3. We represent the components of the position vectors of the atoms with respect to this new basis set. Thus, the p-th component of the position vector of atom j with respect to a new reference frame at the grid point i is given by \({r_p}=\left({\bf{e_p}}\cdot {\bf{e_q^{0}}}\right){r_q^{0}}\). The Einstein summation convention is used; repeated indices have the range of 1, 2, 3. The components of r in the new reference frame are denoted by (r1, r2, r3) in the following.

In order to handle systems with multiple chemical species, species information needs to be encoded in the descriptors. One strategy proposed in previous work is to compute descriptors for individual species and concatenate the descriptors29. Another strategy is to encode chemical species through a one-hot vector119. In this work, we encode the species information using the atomic number of the species. The atomic number of the j-th atom is denoted as Zj. Incorporating the species information, the updated descriptors are \({{\mathcal{D}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{5M}\) are given as,

Therefore, the number of proposed descriptors does not increase with the number of species present in the alloy, for a fixed M.

The computational time required to calculate the proposed descriptors is about twice the time required by scalar product descriptors38 and approximately the same as SNAP descriptors120,121.

Selection of the optimal set of descriptor

The nearsightedness principle117,118 and screening effects122 imply that electron density at a given grid point is minimally influenced by atoms far away. This suggests that only descriptors from atoms close to a grid point are necessary for the ML model. However, the optimal set of descriptors for accuracy are not known a priori and can be computationally expensive to determine through a grid search123.

Using an excessive number of descriptors can increase the computational cost of descriptor calculation, model training, and inference. It can also lead to issues like the curse of dimensionality, reducing the model’s prediction performance124,125,126,127, or may necessitate a larger neural network to learn effectively. Conversely, using too few descriptors results in an incomplete representation of atomic environments, leading to an inaccurate model.

Selection of an optimal set of descriptors has been explored in prior works, particularly for Behler-Parinello symmetry functions128,129 or widely used Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP)130 descriptors123. These systematic procedures for descriptor selection eliminate the trial-and-error approach often used when finalizing a descriptor set. In ref. 129, the authors demonstrated that an optimized set of descriptors can enhance the efficiency of ML models. Therefore, selecting an optimal set of descriptors for a given atomic system is crucial for balancing computational cost and prediction accuracy. Let M (M ≤ Na) be a set of nearest neighboring atoms for grid points. We compute the descriptors for various M and the corresponding errors in an ML model’s prediction. The optimal value of M is the one that minimizes the error. Figure 12 shows the error in the ML model’s prediction for different values of M for the SiGeSn system, showing that the optimum value of M is near 55. Computation of error in the ML model’s prediction for each M involves descriptor computation, training of the neural network, and testing, and therefore is computationally expensive. Given that a neural network needs to be trained for each selected M, descriptor optimization is challenging. In our previous work47, we demonstrated descriptor convergence; it required training of 25 neural networks to obtain the optimal number of descriptors for Aluminum. In this work, because of the proposed descriptors, descriptor convergence requires training of only 7 neural networks. Most existing approaches to descriptor convergence involve optimizing the cutoff radius (analogous to the number of nearest atoms) and the number of basis functions29,129. In contrast, the proposed descriptors in this work require optimization with respect to only one variable, M, the number of nearest atoms. This significantly reduces the time needed to identify the optimal set of descriptors. Once optimized, we used the same value of M across binary, ternary, and quaternary alloys. Our results show errors of similar magnitude across all these systems, giving us confidence in our choice.

Equivariance through invariant descriptors

The proposed descriptors are invariant to rotation and translation, as the position vectors are represented through a unique body-attached reference frame at the grid point. Additionally, invariance to the permutation of atomic indices is maintained, since the position vectors are sorted based on their distance from the origin. Given that the predicted electron density is a scalar-valued variable, the invariance of the input features is sufficient to ensure the equivariance of the predicted electron density under rotation, translation, and permutation of atomic indices, as noted in references47,53,131.

Bayesian neural network

Bayesian Neural Networks are the stochastic counterparts of the traditional deterministic neural networks with advantages such as better generalization and robust uncertainty quantification. We train a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) to predict the probability distribution, P(ρ∣x, D), of the output electron density (ρ), given a set of training data, \(D={\{{{\bf{x}}}_{i},{\rho }_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{N}_{d}}\), and an input descriptor \({\bf{x}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{N}_{{\rm{desc}}}}\). In BNNs, this is achieved by learning stochastic network parameters in contrast to the deterministic parameters learned in a traditional deep neural network. By assuming prior distribution P(w) for the network parameters w ∈ Ωw, the posterior distribution P(w∣D) is obtained from the Bayes’ rule as P(w∣D) = P(D∣w)P(w)/P(D). Here w ∈ Ωw is the set of parameters of the network and P(D∣w) is the likelihood of the data.

However, the term P(D) – known as the model evidence – is intractable, since it involves a high dimensional integral which in turn results in an intractable posterior distribution P(w∣D). Therefore, the posterior distribution is approximated by variational inference132,133,134,135,136. In variational inference, the intractable posterior P(w∣D) is approximated by a tractable distribution, called the variational posterior (q(w∣θ)), from a known family of distributions such as the Gaussian. The parameters (θ) of the distribution q(w∣θ) are optimized such that the statistical dissimilarity between the variational posterior and the true posterior is minimized. If the dissimilarity metric is taken as the KL divergence, we get the following optimization problem:

This leads to the following loss function for BNN that has to be minimized:

Once the posterior distribution of the parameters are approximated by variational inference, the probability distribution for the output can be evaluated by marginalizing over w as:

This marginalization helps in improving generalization, as it is equivalent to learning an ensemble of deterministic networks with different parameters w. Furthermore, the variance of this distribution P(ρ∣x, D) is a measure of model uncertainty in the predictions.

Uncertainty quantification

Bayesian Neural Networks provide a natural way to quantify uncertainties, since they predict a probability distribution for outputs. The uncertainties in the prediction can be classified as ‘aleatoric’ and ‘epistemic’ uncertainties. Aleatoric uncertainty stems from the natural variability in the system, such as noise in the training data. Whereas, epistemic uncertainties are a result of model uncertainties, such as the uncertainty in the parameters of the model.

Variance in the output distribution P(ρ∣x, D) is a measure of uncertainty in the model prediction. The variance of this distribution is given as:

To evaluate this variance, a jth sample for each parameter is drawn following the learned posterior distributions q(w∣θ) for the parameters of the network. The network is then evaluated for this sample to predict the output, \({\widehat{\rho }}_{j}(x)\), for a given input. This process is repeated for a total of Ns samples. This enables us to evaluate the epistemic uncertainty, which is the second term of Eq. (7). Next, σ(x) – which is a heterogeneous noise parameter representing the aleatoric uncertainty – can be predicted by the network along with the output ρ. For a Gaussian likelihood, the noise σ(x) can be learned through the likelihood term of the loss function Eq. (4) following ref. 137 as:

Here, Nd is the size of the training data set.

In a well-calibrated model, the predictive distribution of the output closely resembles the empirical distribution of the data. However, it is to be noted that the uncertainties presented in this work are uncalibrated. While calibration can provide better estimates of uncertainties, only the ordering of the uncertainty estimates among different compositions matters for the active learning framework employed here. Since calibration methods such as the ones presented in138,139 do not affect this ordering, recalibration was not performed in this work.

Bayesian active learning

The number of possible stoichiometric compositions in ternary and quaternary alloys is very large. Thus KS-DFT calculations on all of these compositions to create a ML model are quite expensive. There might be an optimal subset of compositions that contains sufficient information to train a ML model. However, such subsets are not known a priori. We utilize the Active Learning technique to identify such an optimal subset of compositions to reduce the cost of data generation through KS-DFT.

Active learning is a machine learning algorithm that can query data points that need to be labeled to learn a surrogate model. Active learning is primarily used when the computational cost associated with generating the training labels is high. A schematic of Bayesian active learning is shown in Fig. 13. In the first step, an initial set of training data is generated by ab initio calculations and a Bayesian Neural Network model is trained on this initial training set. The second step involves optimizing an acquisition function. In active learning, an acquisition function explores the input space to find the next input point that is most informative to learn the input-output relationship. In this work, we hypothesize that the composition (or the set of compositions) with the highest epistemic uncertainty in the predictions contains the most information to learn the surrogate model. Therefore, the epistemic uncertainty in the predictions obtained by the Bayesian Neural Network as explained in the previous section is used as the acquisition function. Optimization of this acquisition function is achieved by evaluating the test compositions using the Bayesian network to obtain the ones with high uncertainties in their predictions. As a third step of the active learning framework, ab initio calculation needs to be performed for the compositions with high uncertainties found by optimizing the acquisition function. As a final step, this new data is appended to the training set, and the first, second, and third steps are repeated until a satisfactory model is learned. In our present study, once a composition was identified for appending to the dataset, all the configuration snapshots (of varying atomic arrangements) associated with that composition were included in the next batch of training data.

To get a sense of the baseline errors while predicting across composition space, and to demonstrate the advantage of the Bayesian AL technique over the random selection of compositions, we have compared the errors from these two approaches in Fig. 14. Both approaches used the same number (20) of compositions and the same amount of data. The advantage of the Bayesian AL technique is evident from the plot. Three different sets of randomly chosen compositions were used to develop three ML models and the error bars indicate the range of maximum NRMSE values observed across these models.

This figure compares the maximum NRMSE across the composition space of the CrFeCoNi quaternary system using two different sampling strategies. The first bar shows the result from a model trained with 20 compositions selected via Bayesian Active Learning. The second bar corresponds to one of three models trained on 20 randomly selected compositions; the error bars indicate the range of maximum NRMSE values observed across the three models. All models were trained using the same number of data points, demonstrating the improved accuracy achieved through Bayesian Active Learning.

Tessellation-based Iterative Training

In Tessellation-based Iterative Training, we iteratively train the ML model on progressively larger subsets of compositions. We select the subsets by progressively refining the tessellation of the composition spaces. We tessellate the triangular and tetrahedral spaces of ternary and quaternary compositions using regular triangles and tetrahedrons. Successive levels of refinement are shown in Fig. 3. The training compositions are chosen at the vertices of these triangles and tetrahedrons. The four triangular tessellations are denoted as T1, T2, T3, and T4, corresponding to 3, 6, 9, and 15 training points, respectively. However, the edge points of T3 do not include the edge points of T2. Therefore, we skip the T3 iteration and use T4 directly as the next iteration after T2 to ensure that no training data is discarded. For the quaternary system, tessellation iterations T1, T2, and T4, using regular tetrahedrons yields 4, 10, and 34 vertex points, respectively. The second level of refinement includes all 10 compositions on the edges or vertices of the tetrahedrons and, therefore, does not have any composition that includes more than two elements. It has an octahedral space in the middle of the smaller tetrahedrons (see Fig. 1 of ref. 140 and Fig. 3). We choose to use the midpoint of the octahedron as an additional training composition, leading to a total of 11 training compositions for the second level of refinement.

Postprocessing

Since much of the utility of predicting charge densities lies in the physical parameters that can be obtained from them, it is prudent to verify how well our model predicts downstream quantities. Here, we focus on computing the total ground state energy as a postprocessing step to validate the predictions of our model. Further material properties of interest, e.g., defect formation energies, etc., can be calculated from these computed energies. The postprocessing step is accomplished as follows. First, the predicted electron densities are rescaled by the total number of electrons:

where Ω is the periodic supercell used in the calculations, and Ne is the number of electrons in the system. This step serves to ensure that the total system charge is accurately preserved by the ML predictions; this has been found to be important for obtaining high-quality predictions in the energy38,141. Next, the scaled densities are input to the same real-space electronic structure calculation framework, as used for data generation100,108,109,110,142,143. The same calculation settings (e.g., real space mesh size, pseudopotentials, exchange-correlation functional, etc.) are chosen for the post-processing steps, which involve setting up of the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian using the scaled electron density, diagonalization of the Hamiltonian, and subsequent calculation of the Harris-Foulkes energy144,145:

Here, the first term and the last term on the right hand side denote the electronic band-structure energy (Eband) and the electronic entropy contributions (Eelec−entropy), respectively. These terms are directly dependent on the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, while the remaining right-hand terms are calculated readily from electron densities. The terms Exc and EVxc denote contributions from the exchange correlation energy and its potential, respectively. The term Eelectrostatics arises from electrostatic interactions and includes electron-electron, electron-ion, and ion-ion contributions, as well as corrections from pseudocharge self-interactions and overlaps100,110. The specific forms of each of the terms on the right-hand, as well as their implementation within the SPARC electronic structure code used in this work, are available in100,110. Notably, the Harris-Foulkes energy is chosen since it is known to be less sensitive to self-consistency errors, and is therefore known to give a better estimate of the true Kohn-Sham ground-state energy146.

The total energy errors for the systems considered in this work are summarized in Fig. 8. Additionally, Figs. S10–S11 in the Supplementary Material display the energy errors across the individual compositions considered. Performing this postprocessing step is an important component of the work, allowing us to observe the extent to which subtle errors in charge density predictions could propagate to downstream system properties.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at Hoffman2 High-Performance Compute Cluster at UCLA’s Institute for Digital Research and Education (IDRE) and National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Computer codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Codes supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Martin, R. M. Electronic Structure: Basic Theory and Practical Methods (Cambridge University Press, 2004), first edn.

Hafner, J., Wolverton, C. & Ceder, G. Toward computational materials design: the impact of density functional theory on materials research. MRS Bull 31, 659–668 (2006).

Saal, J. E., Kirklin, S., Aykol, M., Meredig, B. & Wolverton, C. Materials design and discovery with high-throughput density functional theory: the open quantum materials database (oqmd). Jom 65, 1501–1509 (2013).

Emery, A. A. & Wolverton, C. High-throughput DFT calculations of formation energy, stability and oxygen vacancy formation energy of ABO3 perovskites. Sci. Data 4, 1–10 (2017).

Choudhary, K. et al. High-throughput density functional perturbation theory and machine learning predictions of infrared, piezoelectric, and dielectric responses. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 64 (2020).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Jain, A. et al. The materials project: Accelerating materials design through theory-driven data and tools. Handb. Mater. Model.: Methods: Theory Model. 1751–1784 (2020).

Gavini, V. et al. Roadmap on electronic structure codes in the exascale era. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 31, 063301 (2023).

Goedecker, S. Linear scaling electronic structure methods. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, 1085 (1999).

Banerjee, A. S., Lin, L., Hu, W., Yang, C. & Pask, J. E. Chebyshev polynomial filtered subspace iteration in the discontinuous Galerkin method for large-scale electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 154101 (2016).

Banerjee, A. S., Lin, L., Suryanarayana, P., Yang, C. & Pask, J. E. Two-level Chebyshev filter based complementary subspace method: pushing the envelope of large-scale electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 2930–2946 (2018).

Motamarri, P. & Gavini, V. Subquadratic-scaling subspace projection method for large-scale Kohn-Sham density functional theory calculations using spectral finite-element discretization. Phys. Rev. B 90, 115127 (2014).

Lin, L., García, A., Huhs, G. & Yang, C. SIESTA-PEXSI: Massively parallel method for efficient and accurate ab initio materials simulation without matrix diagonalization. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 26, 305503 (2014).

Dogan, M., Liou, K.-H. & Chelikowsky, J. R. Real-space solution to the electronic structure problem for nearly a million electrons. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 244114 (2023).

Gavini, V., Bhattacharya, K. & Ortiz, M. Vacancy clustering and prismatic dislocation loop formation in aluminum. Phys. Rev. B 76, 180101 (2007).

Carr, S., Fang, S. & Kaxiras, E. Electronic-structure methods for twisted moiré layers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 748–763 (2020).

Jaros, M. Electronic properties of semiconductor alloy systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 48, 1091 (1985).

Wei, S.-H., Ferreira, L., Bernard, J. E. & Zunger, A. Electronic properties of random alloys: Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. B 42, 9622 (1990).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Comparison of two calculation models for high entropy alloys: Virtual crystal approximation and special quasi-random structure. Mater. Lett. 282, 128754 (2021).

Tian, F., Varga, L. K., Shen, J. & Vitos, L. Calculating elastic constants in high-entropy alloys using the coherent potential approximation: Current issues and errors. Comput. Mater. Sci. 111, 350–358 (2016).

Karabin, M. et al. Ab initio approaches to high-entropy alloys: a comparison of cpa, SQS, and supercell methods. J. Mater. Sci. 57, 10677–10690 (2022).

Gao, M. C., Niu, C., Jiang, C. & Irving, D. L. Applications of special quasi-random structures to high-entropy alloys. High-entropy Alloys: Fundam. Appl. 333–368 (2016).

Lewis, A. M., Grisafi, A., Ceriotti, M. & Rossi, M. Learning electron densities in the condensed phase. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 7203–7214 (2021).

Jørgensen, P. B. & Bhowmik, A. Equivariant graph neural networks for fast electron density estimation of molecules, liquids, and solids. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 183 (2022).

Zepeda-Núñez, L. et al. Deep density: circumventing the Kohn-Sham equations via symmetry preserving neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 443, 110523 (2021).

Chandrasekaran, A. et al. Solving the electronic structure problem with machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 22 (2019).

Fiedler, L. et al. Predicting electronic structures at any length scale with machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 115 (2023).

Brockherde, F. et al. Bypassing the kohn-sham equations with machine learning. Nat. Commun. 8, 872 (2017).

del Rio, B. G., Phan, B. & Ramprasad, R. A deep learning framework to emulate density functional theory. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 158 (2023).

Tang, Z. et al. Improving density matrix electronic structure method by deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.17561 (2024).

Shao, X., Paetow, L., Tuckerman, M. E. & Pavanello, M. Machine learning electronic structure methods based on the one-electron reduced density matrix. Nat. Commun. 14, 6281 (2023).

Hazra, S., Patil, U. & Sanvito, S. Predicting the one-particle density matrix with machine learning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. (2024).