Abstract

We present mumax+, an extensible GPU-accelerated micromagnetic simulator with a Python user interface, to address the challenges posed by current magnetism research into systems with complex magnetic ordering and interfaces. It is a general solver for the space- and time-dependent evolution of the magnetization and related vector quantities, using finite difference discretization. Here, we present its design and application and discuss features not available in mumax3, such as the modeling of antiferromagnets with magnetoelastic coupling. As an illustration of its capabilities, we use mumax+ to simulate state-of-the-art magnetic systems. Specifically, we demonstrate the current-induced domain wall motion in a polycrystalline antiferromagnet, we simulate the working principle of a strain-driven antiferromagnetic racetrack memory and we reproduce experimentally observed domain structures in a non-collinear antiferromagnet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Micromagnetic calculations have been an indispensable tool for the development of the field of modern magnetism. Especially the availability of open-source1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and GPU-accelerated software packages5,8,9,10,12,13,14,15,16,17 boosted research by enabling efficient numerical studies of nano- and micrometer-sized magnetic systems, complementary to experimental investigations. More recently, research efforts have shifted to more complex magnetic systems such as antiferromagnets18 and 2D magnetic heterostructures (Van der Waals systems)19. Different ways of manipulating the magnetization are being explored as well, e.g., by applying strain20 or electric fields21.

In order to model these materials, software tools must go beyond the standard micromagnetic theory of ferromagnets; preferably, they should be easily extensible to include other physical phenomena of interest. With this in mind, we designed mumax+, a versatile GPU-accelerated simulation package. It calculates the space- and time-evolution of nano- to microscale magnets using a finite difference scheme. The software has been designed from scratch, independently of mumax3 5 and features a Python-based22 user interface. This allows users to directly use common packages such as NumPy23, SciPy24 and Matplotlib25 to process and view their data directly. The Python module wraps the main part of the code, which is written in C++26 and CUDA27. The latter allows calculations to be performed in parallel on a GPU, reducing simulation time compared to CPU-based codes.

The extensible framework of mumax+ stands in stark contrast to the design of mumax3. This extensibility provides a plethora of new possibilities, many of which have been brought together in the implementation of (non-collinear) antiferromagnets with full support for magnetoelastic interactions. Therefore, in this paper, we will present the design and application of these two features, emphasizing their practical importance for the current research field of magnetism.

We provide a brief description of the design of the software package along with an overview of the implemented physics. Next, we examine the domain wall motion in a polycrystalline antiferromagnet under the influence of an applied current. Furthermore, we show the working principle of a strain-driven magnetic racetrack in NiO and, lastly, reproduce nitrogen-vacancy magnetometry images of the non-collinear antiferromagnet \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\).

The development of mumax+ is motivated by the “plus” mindset, i.e., versatility and extensibility, combined with user-friendliness, in favor of performance and speed. Our intention is not to replace mumax3, but rather to offer a platform where additional functionalities can easily be developed and used.

All capabilities of the code have been tested with the μMAG micromagnetic standard problems28, mumax3 5 and analytical results. These tests will not be repeated here, but can be found freely in the test folder in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/mumax/plus), along with the complete open-source code under the GPLv3 license. The repository also contains the Python input scripts to generate the figures from this paper. These can be found under the paper2025 tag. Details about dependencies and installation instructions can also be found in the repository. These, along with some examples and tutorial scripts, can also be found on the website (https://mumax.github.io/plus/). Here we outline the physics included in mumax+ with an emphasis on the differences compared to mumax3. A more detailed description of the different functionalities and features can be found in the API on the website.

Results

Micromagnetism

For each ferromagnet defined in the simulation world, mumax+ solves the dynamic equation

where m is the magnetization normalized with respect to the saturation magnetization MS and τ is the sum of the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) torque29 and any additional spin-transfer torques as formulated by Zhang and Li30 or Slonczewski31, which are implemented in the same way as in mumax3 5. The LLG torque is given by

with γ the gyromagnetic ratio and α the dimensionless Gilbert damping constant29,32. The different field terms which play a role and add up to the effective field Beff are calculated based on the current magnetization state m ≡ m(r, t). These fields include an external field, the uniaxial or cubic anisotropy field, the exchange field, a demagnetizing field, stray fields from other magnets, the field induced by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI), a thermal field and the magnetoelastic field. Of these, the external field, anisotropy fields and thermal field for ferromagnets33 are implemented in the same way as in mumax3. Their details will not be repeated here, and we refer the interested reader to their thorough description in Ref. 5.

A micromagnetic theory of ferromagnets assumes that the magnetization field can be described by a mesoscopic continuous function of space and time34, essentially coarse-graining the atomistic structure of a magnetic material. Each simulation cell in that sense contains one macrospin which is the result of the averaging of spins within multiple crystal unit cells. This continuum picture is only valid under the so-called small-angle approximation when considering the exchange interaction between neighboring cells5,35. When extending this formalism to antiferromagnets, we consider two sublattices, meaning each simulation cell contains two macrospins instead of only one15,36,37 and the LLG equation (1) is solved for each one simultaneously. These are exchange-coupled to each other and to each of the neighboring spins. Here, the same small-angle approximation remains satisfied when considering spins from the same sublattice. Additionally, neighboring spins which are antiferromagnetically coupled (i.e., from different sublattices) must also adhere to a small-angle approximation in the sense that the deviation from a relative 180∘ angle must be small.

The remainder of this section highlights features and implementations that differ from those present in mumax3. While our focus is on ferromagnets and collinear antiferromagnets, the underlying formalism naturally generalizes to ferrimagnets and non-collinear antiferromagnets. The former is achieved by considering two different sublattices in an antiferromagnet, while the latter can be simulated by adding a third sublattice with the same interaction terms as the first two.

The exchange field present in an antiferromagnet acting on sublattice s under the influence of the other sublattice \(s^{\prime}\) is described in Refs. 36,37 and is given by

The first term in Eq. (3) accounts for the standard ferromagnetic exchange interaction. This is the only term present when simulating ferromagnetic systems and is implemented as in mumax3 5. The second term contains the inhomogeneous exchange stiffness constant A12 < 0 J/m and describes a similar antiferromagnetic exchange interaction between sublattices. The last term accounts for the homogeneous exchange interaction between antiferromagnetically coupled spins within the same simulation cell. This interaction is described by a homogeneous exchange constant A0 < 0 J/m and a lattice parameter a.

The last term in Eq. (3) must not adhere to the small-angle approximation mentioned above, since it describes the interaction between spins of two different sublattices at the same point in space. The functional form of the first two field terms, however, assumes this approximation5,35,36. A derivation of these nearest-neighbor interaction terms is given in Ref. 36 and provides an exchange length which is a minimal length scale at which spin modulations manifest. The antiferromagnetic exchange interaction term is of the same form as the ferromagnetic one5,36, meaning the exchange length can be calculated analogously. Following this, the exchange length corresponding to the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic exchange interactions can be calculated as

respectively. Here, μ0 denotes the vacuum permeability. In order to be able to resolve spin modulations in any micromagnetic simulation, the cell size should be chosen to be smaller than the (smallest) exchange length.

In mumax+, the user can set the individual components of the antisymmetric rank-3 tensor Dijk of the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI), which encompasses the DMI strengths and chiral properties of the considered lattice. Since the DMI tensor is determined by the crystallographic and magnetic symmetries of the material, each sublattice in an antiferromagnet can have its own crystallographic environment and thus its own DMI tensor. Furthermore, a third DMI tensor is used to describe the intersublattice interaction.

Generally, the energy density due to DMI in an antiferromagnet can be written as38,39

where \((s,{s}^{{\prime} })\) denote the different sublattices, the indices (i, j, k) indicate spatial components and it is assumed that the intersublattice DMI is symmetric in the sublattices, meaning \({D}_{ijk}^{(s,{s}^{{\prime} })}={D}_{ijk}^{({s}^{{\prime} },s)}\). The ferromagnetic expression is obtained by considering \(s={s}^{{\prime} }\).

The tensorial character of the DMI also comes into play when calculating the Neumann boundary conditions. Given the structure of the exchange field in Eq. (3), the boundary conditions for a sublattice s in an antiferromagnet are given by37,38

where n is the surface normal and a term proportional to the inhomogeneous exchange constant A12 takes the interaction with the other sublattice into account. This term is not present when considering ferromagnets.

The Neumann boundary conditions as given in Eq. (6) are the default in mumax+. Alternatively, open (∂nm = 0) or periodic boundary conditions can be used. The chosen boundary conditions will not only affect the DMI field calculations, but also the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic inhomogeneous exchange calculations. Periodic boundary conditions also affect the calculation of the magnetostatic fields.

Apart from the inhomogeneous interaction described by Eq. (5), mumax+ also considers a homogeneous DMI between spins within the same simulation cell, given by the energy density40,41

where s and \({s}^{{\prime} }\) denote two distinct sublattices and d is the DMI vector. The latter lies parallel to the principal axis of the material40.

The random thermal field to include finite temperatures in antiferromagnets is implemented with each sublattice having its own effective field, as if it were an independent ferromagnetic lattice, in the same way it is done in Boris15. To validate this approach, one can consider a thought experiment with two sublattices with uniaxial anisotropy, a positive homogeneous exchange coupling between them and no demagnetizing field. The anisotropy results in two energy minima, with uniform magnetization, separated by an energy barrier. The spins can switch from one minimum to the other under the influence of a thermal field. The analytical expression of this switching rate for the case of ferromagnets is well-known5,42. In the limit of low exchange coupling, each sublattice is expected to have the same switching time as a ferromagnet with the same saturation magnetization MS and uniaxial anisotropy constant Ku1 as either sublattice, since each sublattice acts independently as a single ferromagnetic lattice. In the limit of high coupling, the sublattice moments within a simulation cell must behave collectively, effectively doubling the magnetic moment. This can be compared with a ferromagnet with double the value for MS and double the value for Ku1 to keep the anisotropic energy per moment constant. We simulate an ensemble of spins with uniaxial anisotropy at 400 K for a range of coupling constants using mumax+, the results of which are shown in Fig. 1. In the limit of low exchange coupling, the sublattices behave as a ferromagnet with the same MS and Ku1. In the limit of high coupling, the datapoints coincide with the switching time of a ferromagnet with 2MS and 2Ku1, confirming the validity of this approach. Following the same argument, this thought experiment can be repeated in the case of a non-collinear antiferromagnet. The resulting switching times in Fig. 1 again show excellent agreement with the switching time of the corresponding ferromagnet.

Elasticity

Apart from the magnetodynamic equation (1), mumax+ can also solve the second order elastodynamic equation43,44

or, equivalently, the two first order differential equations

with u the elastic displacement, v the velocity, ρ the mass density and the total body force density ftot = fd + fext + fmel + fel. The latter contains a damping force fd = − η v with a phenomenological damping parameter η, an external force fext set by the user, the magnetoelastic body force fmel described in the next section, and the elastic body force \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{el}}}=\nabla \cdot \hat{\sigma }\). The second order mechanical stress tensor \(\hat{\sigma }\) is given by Hooke’s law \(\hat{\sigma }=\hat{{\bf{c}}}:\hat{\varepsilon }\), where \(\hat{{\bf{c}}}\) is the fourth order stiffness tensor and \(\hat{\varepsilon }=\frac{1}{2}\left({\mathbf{\nabla }}{\bf{u}}+{\left({\mathbf{\nabla }}{\bf{u}}\right)}^{\top }\right)\) is the symmetric second order strain tensor43,44.

Viscous damping can be added to the stress \(\hat{\sigma }\) via an extra term \({\hat{\sigma }}_{{\rm{d}}}=\hat{\eta }:\partial \hat{\varepsilon }/\partial t\), which is proportional to the strain rate45,46,47. The fourth order viscosity tensor \(\hat{\eta }\) is usually set to be proportional to the stiffness tensor \(\hat{{\bf{c}}}\). This tends to dampen high frequency oscillations48.

Both first order equations (9) are solved simultaneously using one of the available Runge-Kutta methods in Table 1. Each body force is implemented for cubic crystal symmetries and is based on a previous extension of mumax3 49, with the exceptions of the additional viscous stress \({\hat{\sigma }}_{{\rm{d}}}\) and the fact that fel does not utilize second order differences of the elastic displacement. Rather, it is computed as the numeric divergence of the stress \(\hat{\sigma }\), while the strain is calculated with the numeric gradient of the displacement. In this way, traction and traction-free boundary conditions50 are easily implemented. These impose \(\hat{\sigma }\cdot {\bf{n}}={\bf{t}}\) at the boundary, where n is the normal to the boundary and t is the applied traction as force per unit area. Both spatial derivative calculations utilize a fourth order accurate central difference scheme51 in the bulk material. Lower order schemes are used close to and at the boundaries.

Magnetoelasticity

Magnetoelasticity for ferromagnets with cubic crystal symmetry is implemented in the same way as described in Ref. 49. The magnetoelastic energy density, given by52,53

gives rise to magnetostriction and the Villari effect or inverse magnetostriction54. Here, the summation indices indicate spatial components, B1 and B2 are the magnetoelastic coupling constants and \(\hat{\varepsilon }\) is the strain tensor. In the case of magnetostriction the magnetization affects the elastic displacement by applying a magnetoelastic force given by

while for the Villari effect the elastic strain affects the magnetization by generating an effective field given by

For antiferromagnets, magnetoelasticity is implemented as it is reported in Ref. 55. Both sublattices have a shared elastic displacement, velocity, stiffness, strain and total body force, while each ferromagnetic sublattice s has its own magnetoelastic coupling constants \({B}_{1}^{(s)}\) and \({B}_{2}^{(s)}\), magnetization \({{\bf{m}}}^{(s)}\) and saturation magnetization \({M}_{\,\text{S}\,}^{(s)}\). Each sublattice then creates a magnetoelastic body force \({{\bf{f}}}_{\,\text{mel}\,}^{(s)}\). Conversely, each sublattice magnetization is affected by a unique magnetoelastic field \({{\bf{B}}}_{\,\text{mel}\,}^{(s)}\) created by its own magnetization \({{\bf{m}}}^{(s)}\) and the shared strain.

Demonstration 1: Current-driven domain wall mobility in a polycrystalline antiferromagnetic strip

Understanding the mobility properties of magnetic solitons like domain walls and skyrmions in various materials has been an important field of study for the development of future spintronic devices18,56,57,58. We can use mumax+ to investigate such dynamics in antiferromagnets. To this end, we base our antiferromagnetic system on the one described in Ref. 37 and illustrate how the current-induced motion of a domain wall can be studied in an antiferromagnetic strip with polycrystalline structure. The domain wall is stabilized by interfacial DMI and can be moved by applying a spin-polarized current in the direction of the strip, effectively causing a spin transfer torque as formulated by Slonczewski31. Following mumax3, we are able to define multi-grain geometries inside a material by generating a Voronoi tessellation59. The ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic exchange constants are then reduced at the different grain boundaries60.

We simulate a strip with a width of 200 nm and a thickness of 10 nm. The strip is discretized into cells of size 2 × 2 × 10 nm3 and we define grains with an average diameter of 10 nm. This simulation setup is illustrated in Fig. 2a and described in more detail in the caption of Fig. 2.

The panels show the simulation setup (a) and mobility curves (b). Each sublattice has a uniaxial out-of-plane anisotropy with a strength of 64 kJ/m3, a saturation magnetization of 400 kA/m, interfacial DMI strength of 0.11 mJ/m2 and a damping constant of 0.137. The homogeneous antiferromagnetic exchange constant is set at -50 pJ/m. The top panel in (a) shows the relaxed Néel vector of a polycrystalline antiferromagnetic strip. The domain wall, in which the Néel vector lies along the positive x direction, separates two out-of-plane domains. The ferromagnetic and inhomogeneous antiferromagnetic exchange constants, 10 pJ/m and -10 pJ/m respectively, are reduced by 75 % at the grain boundaries. The bottom panel in (a) shows the different grains inside the material, generated using a Voronoi tessellation59 with an average grain diameter of 10 nm. Panel (b) shows the simulated domain wall velocity in an antiferromagnetic strip under the influence of an applied current density, with each curve corresponding to a different percentage reduction in exchange constants at the grain boundaries. The dashed curve shows the analytical model derived in Ref. 37 for the monocrystalline case.

We monitor the velocity of the domain wall in a time frame of 0.5 ns for different values of the current density and for different reductions of the exchange constants at the various grain boundaries. Results can be found in Fig. 2b. We see a distinct decrease in the slope of the velocity curves for decreasing values of the intergrain exchange along with a stronger domain wall pinning at lower current densities. These results are very similar to those reported in Refs. 59,60, where similar simulations based on permalloy have been performed. The dashed curve in Fig. 2b represents the model derived in Ref. 37 for the ideal case without grains. Our simulation data for a 0% reduction of the exchange constants, effectively disregarding any grain boundaries, agree very well with this model, with the maximal deviation being about 1%.

Demonstration 2: Strain-driven antiferromagnetic racetrack memory

Previous studies have demonstrated the possibility to move domain walls in both ferromagnets and antiferromagnets through the application of surface acoustic waves or strain gradients61,62,63. Building on this concept, we use mumax+ to investigate the controlled movement of domain walls in antiferromagnetic NiO under the influence of strain caused by the application of traction. The simulation consists of 512 × 128 × 1 cubic cells with a side length of 3 nm. The magnet has an easy anisotropy axis along the length axis of the magnet and an interfacial DMI which can be produced by placing NiO in contact with a heavy metal64. This stabilizes two out-of-plane domain walls, separating domains in which the Néel vector lies along the easy axis. Four small notches are introduced from 300 nm onward with 150 nm spacing, which serve as pinning sites for the domain walls. The material parameters used in the simulation can be found in Table 2.

Initially, two domain walls are placed on the first and third notch. In order to move both domain walls one notch along the strip, we generate an elastic shear pulse by applying one period of a sinusoidal out-of-plane traction oscillation with a frequency of 8 GHz and an amplitude of 0.3 GPa at a boundary. The resulting dynamics are shown in Fig. 3. The induced strain, approximately 0.14% in amplitude, detaches the domain wall from the first notch via the Villari effect54 and transports it along the length axis of the magnet. The elastic pulse, traveling with a velocity of about 4 km/s, overtakes the domain wall which gets pinned at the second notch. The pulse then detaches the second domain wall which is transported to the final notch in the same manner. This effectively simulates the underlying working principle of a traction-driven magnetic racetrack65. This concept can be extended to various domains with varying sizes in a single antiferromagnetic strip where each domain corresponds to a series of 0 or 1 bits. The domain walls can be shifted one notch at a time by the controlled application of traction pulses.

This pulse mobilizes the domain walls, which are initially pinned at the notches at 300 nm and 600 nm, as discussed in demonstration 2. The top row shows the out-of-plane elastic displacement, while the bottom row shows the Néel vector of the antiferromagnet. The in-plane domains, oriented in the directions indicated by the arrows, are separated by out-of-plane domain walls, shown in black or white, whose Néel vectors lie into, and out of the plane of the film, respectively. Different snapshots after the introduction of the pulse at t = 0 ns are shown. The domain walls have moved to the second and fourth notches at 450 nm and 750 nm, respectively, after passage of the pulse.

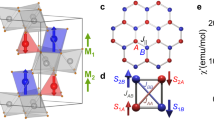

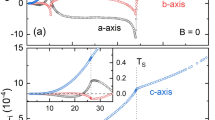

Demonstration 3: Stray field imaging of the non-collinear antiferromagnet \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\)

The non-collinear antiferromagnet \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\) is a prototypical material in the research field of antiferromagnetic spintronics66,67,68,69. Owing to the interplay between exchange, DMI and magnetocrystalline anisotropy, it exhibits a small net magnetic moment67,69, which makes direct imaging of magnetic structures more evident than in collinear antiferromagnets70,71,72.

Li et al.71 imaged magnetic domain structures using nitrogen-vacancy (NV) magnetometry measurements of \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\) films. Here, we demonstrate the simulation of the measured magnetostatic field using mumax+ by considering an antiferromagnet with three exchange-coupled sublattices. We define a square 500 × 500 × 30 nm3 non-collinear antiferromagnetic film discretized into cells of size 1 × 1 × 30 nm3. Grains with an average diameter of 40 nm are generated using a Voronoi tessellation59. Each grain has an easy axis which lies either out-of-plane, perpendicular to the film’s surface, or in a random in-plane direction71. Furthermore, the exchange coupling between neighboring grains is reduced to 10% of the intragrain value. To reproduce the NV scans shown in Ref. 71, we let the non-collinear antiferromagnet relax to an energy minimum starting from a random state. We then calculate the out-of-plane component of the magnet’s stray field in a grid which lies 60 nm above the film’s surface. The results, along with the simulation parameters, can be found in Fig. 4. The qualitative agreement between Figures 4a and 4b, along with the order of magnitude of the stray field showcases the ability of mumax+ to simulate non-collinear antiferromagnetic systems.

Panel (a) shows the calculated field using mumax+ after letting a non-collinear antiferromagnet relax from a random state. Each sublattice has a saturation magnetization of 1 MA/m, uniaxial anisotropy constant of 5 MJ/m2 (based on Ref. 67), a Gilbert damping constant of 0.01 and a typical lattice constant of 3.5 Å. The ferromagnetic, inhomogeneous and homogeneous antiferromagnetic exchange constants are set at 10 pJ/m, -15 pJ/m and -25 pJ/m respectively. The homogeneous DMI vector is set at 10 MJ/m3 in the direction perpendicular to the film, while the interfacial DMI has a set value of 3.5 mJ/m2 84. Panel (b) shows an NV measurement image of a \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\) thin film with a thickness of 30 nm, measured ~ 60 nm above the film’s surface. The scale bar denotes 0.5 μm. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Li, S. et al. (2023). Nanoscale Magnetic Domains in Polycrystalline \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\) Films Imaged by a Scanning Single-Spin Magnetometer. Nano Letters, 23(11), 5326–5333. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c01523. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society.

Performance and memory usage

The object-oriented design of mumax+ allows for great flexibility, versatility and transparency, both in the source code and in an input script. The downside of this framework, along with the Python wrapper, is a performance loss as compared to mumax3. To illustrate this, Fig. 5 compares the throughput of mumax+ and mumax3, which is a measure for the amount of cells that can be processed per second5, as well as the peak GPU memory usage. The data in Fig. 5 shows that the ratio of the throughput of mumax3 and mumax+ (32-bit) is approximately 2.5 in the rising regime and 1.6 in the constant regime. The latter ratio is about 3 in the case of 64-bit precision. The throughput of antiferromagnetic simulations is 2 to 3 times lower than that of equally sized ferromagnetic simulations using mumax+, depending on the grid size. Before saturation, part of the performance decrease can be explained by the two magnetization vectors per finite difference cell which have to be accounted for. In the saturated regime where the performance no longer depends directly on the grid size (or the number of magnetization vectors per simulation cell), the difference shows the overhead cost of the increased number of exchange and magnetostatic interactions.

The peak GPU memory usage, also shown in Fig. 5, indicates that the object-oriented framework also comes at a memory cost when compared to mumax3. However, it exhibits an overhead for small grid sizes which is independent of the used software package or simulation. The actual grid size becomes a relevant factor at about 100 thousand cells.

Accuracy

A prototypical test of the numerical accuracy of a micromagnetic solver is the μMAG standard problem 428. Here, we compare the simulation results obtained with mumax+ and mumax3 5 to the ones obtained with OOMMF1. Figure 6 shows the deviation of the y-component of the average magnetization between the two simulations. The other two components are not shown and have a maximal deviation which is about 5 times smaller. The data in Fig. 6 shows that the deviation between mumax+ and OOMMF is smaller than that between OOMMF and mumax3, meaning the implementation of mumax+ is adequate for this benchmarking test.

Discussion

We presented the micromagnetic package mumax+ and highlighted the key differences from mumax3. These advancements include a Python-based interface, support for calculations involving (non-collinear) antiferromagnets and ferrimagnets, and the integration of magnetoelasticity across all magnet types in the package.

As a demonstration of the capabilities of mumax+ that are not present in mumax3, we first presented the current-driven domain wall mobility in a polycrystalline antiferromagnet. Furthermore, the addition of magnetoelastics has provided a way to simulate the working principle of a racetrack memory in NiO driven by strain through the application of traction. Finally, we were able to reproduce nitrogen-vacancy magnetometry images in the non-collinear antiferromagnet \({{\rm{Mn}}}_{3}{\rm{Sn}}\).

The development of mumax+ is ongoing and more functionalities are expected to be added in future releases. Some possibilities include adaptive time stepping appropriate for magnetoelastic simulations, a more general stiffness tensor and piezoelectric coupling. Since mumax+ is open-source and built with an object-oriented design for easy extensibility, anyone can fork the repository (https://github.com/mumax/plus) and enhance the module with additional features.

Methods

The mumax+ module is written in C++ and CUDA for GPU support and can be compiled using either single or double precision. The module is wrapped in Python, allowing it to be imported in a Python script like any other package. The object-oriented character of Python and C++ allows for a very flexible and transparent use of classes and accompanying instances. For example, each magnetic instance has its own set of material parameters and multiple magnets from different magnet classes can simultaneously coexist. This contrasts with mumax3, where the user has to resort to defining a limited number of regions in order to create inhomogeneities in material parameters5. Other advantages of the use of a Python-based interface are prominent, like the use of NumPy’s23 intuitive array indexing logic to set material parameters in different subsets of cells. These benefits are illustrated in the various examples in the Github repository and the website.

Magnetostatic field

The calculation of the magnetostatic field is similar to the method used in OOMMF1. It is done by using the analytical result73 below a certain cutoff radius and the asymptotic result74 above that radius, as the latter is numerically more accurate at large distances. In the case of antiferromagnets, the vector sum of the spins within a simulation cell is computed prior to evaluating the resulting field. Similar to mumax3, periodic boundary conditions for the magnetostatic field are implemented using a macro geometry approach5,6,75.

Time integration

Several embedded Runge–Kutta methods are available for time integration, as listed in Table 1, with the option to use adaptive time stepping76,77,78,79,80.

Data availability

The GitHub repository (https://github.com/mumax/plus) contains the Python input scripts necessary to generate the data and figures from this paper. These can be found under the \(\mathtt{paper2025}\) tag.

Code availability

The complete open-source code of mumax+ can be found freely, under the GPLv3 license, in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/mumax/plus). Details about dependencies and installation instructions can also be found in the repository. These, along with some examples and tutorial scripts, can also be found on the website (https://mumax.github.io/plus/).

References

Donahue, M. OOMMF User’s Guide, Version 1.0 (1999).

Vansteenkiste, A. & Van de Wiele, B. MuMax: a new high-performance micromagnetic simulation tool. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 323, 2585–2591 (2011).

Vansteenkiste, A., Van de Wiele, B., Dvornik, M., Lassalle-Balier, R. & Rowlands, G. mumax2. https://github.com/mumax/2 (2012).

Scholz, W. et al. Scalable parallel micromagnetic solvers for magnetic nanostructures. Comput. Mater. Sci. 28, 366–383 (2003).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of mumax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Fischbacher, T., Franchin, M., Bordignon, G. & Fangohr, H. A systematic approach to multiphysics extensions of finite-element-based micromagnetic simulations: Nmag. IEEE Trans. Magn. 43, 2896–2898 (2007).

MicroMagnetics Team. Magnum.fe: Finite-element micromagnetic simulation. https://github.com/micromagnetics/magnum.fe (2024). Accessed: 2024-12-04.

Bjørk, R., Poulsen, E. B., Nielsen, K. K. & Insinga, A. R. Magtense: a micromagnetic framework using the analytical demagnetization tensor. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 535, 168057 (2021).

Caiyq & Ijin08. Neuralmag: Initial release v1.0.0 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13736224 (2024).

Bruckner, F., Koraltan, S., Abert, C. & Suess, D. magnum.np: a Pytorch based GPU enhanced finite difference micromagnetic simulation framework for high level development and inverse design. Sci. Rep. 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39192-5 (2023).

Bisotti, M.-A. et al. Fidimag—a finite difference atomistic and micromagnetic simulation package. J. Open Res. Softw. 6, 22 (2018).

Wang, W., Lyu, B., Kong, L., Fangohr, H. & Du, H. Micromagnetic.JL: A Julia package for micromagnetic and atomistic simulations with gpu support. Chin. Phys. B 33, 107508 (2024).

Chang, R., Li, S., Lubarda, M. V., Livshitz, B. & Lomakin, V. FastMag: fast micromagnetic simulator for complex magnetic structures (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 109, 07D358 (2011).

Kakay, A., Westphal, E. & Hertel, R. Speedup of FEM micromagnetic simulations with graphical processing units. IEEE Trans. Magn. 46, 2303–2306 (2010).

Lepadatu, S. Boris computational spintronics-High performance multi-mesh magnetic and spin transport modeling software. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 243902 (2020).

Drews, A., Selke, G., Krueger, B., Abert, C. & Gerhardt, T. Micromagnum: Micromagnetic simulation framework. https://github.com/MicroMagnum/MicroMagnum (2024). Accessed: 2024-12-04.

MicroMagnum Team. Magnum.fd: Finite-difference micromagnetic simulation. https://github.com/micromagnetics/magnum.fd (2024). Forked from MicroMagnum, Accessed: 2024-12-04.

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Geim, A. K. & Grigorieva, I. V. Van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 499, 419–425 (2013).

Bandyopadhyay, S. Perspective: There is plenty of room for magnetic straintronics in the analog domain. npj Spintron. 2, 1–15 (2024).

Bandyopadhyay, S., Atulasimha, J. & Barman, A. Magnetic straintronics: manipulating the magnetization of magnetostrictive nanomagnets with strain for energy-efficient applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 041323 (2021).

Van Rossum, G. & Drake, F. L. Python 3 Reference Manual (CreateSpace, Scotts Valley, CA, 2009).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2d graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

ISO/IEC. Iso/iec 14882:2024 - programming languages – C++. ISO/IEC Standard. https://www.iso.org/standard/83626.html (2020).

NVIDIA Corporation. NVIDIA CUDA C programming guide (2024). Version 12.6.

μMAG organization. μ mag micromagnetic modeling activity group (2021). https://www.ctcms.nist.gov/~rdm/mumag.org.html (2021).

Landau, L. & Lifshitz, E. On the Theory of the Dispersion of Magnetic Permeability in Ferromagnetic Bodies. Reproduced in Collected Papers of Ld Landau (Pergamon, New York, 1935).

Zhang, S. & Li, Z. Roles of nonequilibrium conduction electrons on the magnetization dynamics of ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 127204 (2004).

Slonczewski, J. Current-driven excitation of magnetic multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 159, L1–L7 (1996).

Gilbert, T. L. A Lagrangian formulation of the gyromagnetic equation of the magnetization field. Phys. Rev. 100, 1243 (1955).

Leliaert, J. et al. Adaptively time stepping the stochastic Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation at nonzero temperature: implementation and validation in mumax3. AIP Adv. 7, 125010 (2017).

Coey, J. M. Magnetism and Magnetic Materials (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010).

Donahue, M. & Porter, D. Exchange energy formulations for 3d micromagnetics. Phys. B Condens. Matter 343, 177–183 (2004).

Ntallis, N. & Efthimiadis, K. Micromagnetic simulation of an antiferromagnetic particle. Comput. Mater. Sci. 97, 42–47 (2015).

Sánchez-Tejerina, L., Puliafito, V., Khalili Amiri, P., Carpentieri, M. & Finocchio, G. Dynamics of domain-wall motion driven by spin-orbit torque in antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 101, 014433 (2020).

Hals, K. M. D. & Everschor-Sitte, K. New boundary-driven twist states in systems with broken spatial inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 127203 (2017).

Mahfouzi, F. & Kioussis, N. Bulk generalized Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in \({\mathcal{PT}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 106, L220404 (2022).

Gorobets, O. Y. & Gorobets, Y. I. 3d analytical model of skyrmion-like structures in an antiferromagnet with DMI. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 507, 166800 (2020).

Khoshlahni, R., Qaiumzadeh, A., Bergman, A. & Brataas, A. Ultrafast generation and dynamics of isolated skyrmions in antiferromagnetic insulators. Phys. Rev. B 99, 054423 (2019).

Breth, L. et al. Thermal switching field distribution of a single domain particle for field-dependent attempt frequency. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 023903 (2012).

Graff, K. F. Wave Motion in Elastic Solids (Courier Corporation, North Chelmsford, 2012).

Achenbach, J. D. Wave Propagation in Elastic Solids (North-Holland Publishing Company/American Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1973).

Wineman, A. S. & Rajagopal, K. R. Mechanical Response of Polymers: An Introduction (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000).

Rajagopal, K. R. A note on a reappraisal and generalization of the Kelvin-Voigt model. Mech. Res. Commun. 36, 232–235 (2009).

Stachurski, Z. H. Mechanical behavior of materials. Mater. Today 12, 44 (2009).

Semblat, J. Rheological interpretation of Rayleigh damping. J. Sound Vib. 206, 741–744 (1997).

Vanderveken, F. et al. Finite difference magnetoelastic simulator. Open Research Europe 1, 35 (2021).

Barber, J. Elasticity. Solid Mechanics and Its Applications (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2012).

Sauer, T. & Sauer, T. Numerical analysis. Always Learning (Pearson, London, 2012).

Gurevich, A. & Melkov, G. Magnetization Oscillations and Waves (Taylor & Francis, London, 1996).

Tucker, J. W. & Rampton, V. W. Microwave Ultrasonics in Solid State Physics (Amsterdam: North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1972).

Chikazumi, S. Physics of Ferromagnetism. International Series of Monographs on Physics (OUP Oxford, Oxford, 2009).

Barra, A., Domann, J., Kim, K. W. & Carman, G. Voltage control of antiferromagnetic phases at near-Terahertz frequencies. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 034017 (2018).

Allwood, D. A. et al. Magnetic domain-wall logic. Science 309, 1688–1692 (2005).

Nomoto, T. & Arita, R. Cluster multipole dynamics in noncollinear antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 012045 (2020).

Leliaert, J. et al. Influence of material defects on current-driven vortex domain wall mobility. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064419 (2014).

Leliaert, J. et al. Current-driven domain wall mobility in polycrystalline permalloy nanowires: a numerical study. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 233903 (2014).

Leliaert, J. et al. A numerical approach to incorporate intrinsic material defects in micromagnetic simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 17D102 (2014).

Chen, F. et al. Strain-induced megahertz oscillation and stable velocity of an antiferromagnetic domain wall. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 014030 (2021).

Yu, G. et al. Strain-driven magnetic domain wall dynamics controlled by voltage in multiferroic heterostructures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 552, 169229 (2022).

Yu, G. et al. Dynamics of domain wall induced by voltage-controlled strain-field gradient. AIP Adv. 12, 035036 (2022).

Akanda, M. R. K., Park, I. J. & Lake, R. K. Interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction of antiferromagnetic materials. Phys. Rev. B 102, 224414 (2020).

Parkin, S., Hayashi, M. & Thomas, L. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory. Science 320, 190–4 (2008).

Wang, X. et al. Noncollinear mn3sn for antiferromagnetic spintronics 28, 100878. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2542529322002760.

Lee, W.-B. et al. Spin-torque-driven gigahertz magnetization dynamics in the non-collinear antiferromagnet mn3sn 20, 487–493. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41565-025-01859-7.

Park, P. et al. Magnetic excitations in non-collinear antiferromagnetic Weyl semimetal mn3sn 3, 1–8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41535-018-0137-9.

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature 527, 212–215. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature15723.

Reichlova, H. et al. Imaging and writing magnetic domains in the non-collinear antiferromagnet mn3sn 10, 5459. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-13391-z.

Li, S. et al. Nanoscale magnetic domains in polycrystalline mn3sn films imaged by a scanning single-spin magnetometer 23, 5326–5333. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c01523.

Higo, T. et al. Large magneto-optical Kerr effect and imaging of magnetic octupole domains in an antiferromagnetic metal 12, 73–78. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41566-017-0086-z.

Newell, A. J., Williams, W. & Dunlop, D. J. A generalization of the demagnetizing tensor for nonuniform magnetization. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 98, 9551–9555 (1993).

Donahue, M. Accurate computation of the demagnetization tensor. 6th International Symposium on Hysteresis Modeling and Micromagnetics (2007). https://math.nist.gov/~MDonahue/talks.html. Accessed 2024-11-25.

Fangohr, H. et al. A new approach to (quasi) periodic boundary conditions in micromagnetics: the macrogeometry. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 07D529 (2009).

Leader, J. Numerical Analysis and Scientific Computation (Pearson Addison Wesley, Edinburgh, 2004).

Bogacki, P. & Shampine, L. A 3(2) pair of Runge–Kutta formulas. Appl. Math. Lett. 2, 321–325 (1989).

Cash, J. R. & Karp, A. H. A variable order Runge–Kutta method for initial value problems with rapidly varying right-hand sides. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 16, 201–222 (1990).

Fehlberg, E. & Center, G. C. M. S. F. Low-order Classical Runge-Kutta Formulas with Stepsize Control and Their Application to Some Heat Transfer Problems. NASA technical report (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, 1969).

Dormand, J. & Prince, P. A family of embedded Runge–Kutta formulae. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 6, 19–26 (1980).

Ködderitzsch, D. et al. Exchange interactions in NIO and at the NIO(100) surface. Phys. Rev. B 66, 064434 (2002).

Kampfrath, T. et al. Coherent terahertz control of antiferromagnetic spin waves. Nat. Photonics 5, 31–34 (2010).

Azovtsev, A. V. & Pertsev, N. A. Thz and sub-thz antiferromagnetic magnons via magnetoacoustic resonances excited by picosecond strain pulses in nio. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 044404 (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Spin-orbit torque-driven chiral domain wall motion in mn3sn 127, 072402. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0275467.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Oleh Kozynets for his software engineering additions to the code. I.L., D.D.G., J. Maes, M. V. M. and B.V.W. acknowledge financial support from the ShapeME project (EOS ID 400077525) from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) and F.R.S.-FNRS under the Excellence of Science (EOS) program. M. V. M., B.V.W. and J. Mulkers acknowledge financial support from the FWO project No. G098917N. J.L. was supported by FWO with postdoctoral fellowship No. 12W7622N and the Ghent University special research fund (BOF.BAF.2024.0264.01 and BOF.BAF.2025.0052.01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.M.: software, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization; I.L.: software, validation, writing—original draft, writing - review & editing, visualization; D.D.G.: software, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization; J.Mulkers: conceptualization, software, validation; J. Maes: writing–review & editing, visualization; M.V.M.: conceptualization, writing - review & editing, funding acquisition; J.L.: conceptualization, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration; B.V.W.: conceptualization, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moreels, L., Lateur, I., De Gusem, D. et al. mumax+: extensible GPU-accelerated micromagnetics and beyond. npj Comput Mater 12, 71 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01893-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01893-y