Abstract

Generative models show great promise for the inverse design of molecules and inorganic crystals, but remain largely ineffective within more complex structures such as amorphous materials. Here, we present a diffusion model that reliably generates amorphous structures up to 3 orders of magnitude times faster than conventional simulations across processing conditions, compositions, and data sources. Generated structures recovered the short- and medium-range order, sampling diversity, and macroscopic properties of silica glass, as validated by simulations and an information-theoretical strategy. Conditional generation allowed sampling large structures at low cooling rates of 10−2 K/ps to uncover a ductile-to-brittle transition and mesoporous silica structures. Extension to metallic glassy systems accurately reproduced local structures and properties from both computational and experimental datasets, demonstrating how synthetic data can be generated from characterization results. Our methods provide a roadmap for the design and simulation of amorphous materials previously inaccessible to computational methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solving the inverse design of materials is one of the most coveted goals of computational materials science,1 but sampling the space of materials exhibiting outstanding structures and properties remains challenging. In recent years, deep generative models provided an effective framework for sampling data points conditioned on labels.2 Diffusion models, in particular, excel at learning the joint probability distributions of complex data and labels, denoising random inputs into high-fidelity samples, such as images, text, and more3,4. Within materials science, diffusion models have been shown to produce novel inorganic crystal structures conditioned on properties, symmetries, compositions, and other constraints, in an encouraging step for the inverse design of crystalline materials.5,6,7,8

Many technologically relevant solids, however, are not crystalline, but amorphous. Polymers, metallic glasses, battery electrolytes, and phase-change memory alloys are examples of materials lacking the long-range order that makes inorganic crystalline systems comparatively simpler to represent and, in many cases, generate.9,10 Furthermore, the rugged, high-dimensional energy landscapes of amorphous structures demand very long molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo simulations to achieve adequate convergence11. Thus, modeling synthesis-structure-property relationships that can enable the inverse design of amorphous materials remains challenging. Several works have attempted to use generative models, including variational autoencoders, generative adversarial networks, or diffusion models, to produce amorphous configurations12,13,14,15,16,17. However, comparisons between generated and simulated structures show that most models fail to either produce physically correct samples12 or sample structures well outside the training set14,18. Even when structures are reasonable, there is limited evidence that generated samples exhibit the correct macroscopic properties,17 severely limiting the applicability of generative models in computational studies (Supplementary Text, Sec. S1.1).

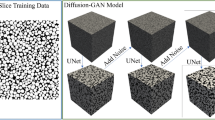

Here, we show that a graph neural network (GNN)-based diffusion model can faithfully generate amorphous structures across diverse compositions, densities, processing conditions, and data sources (Fig. 1). Following a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) framework3 for atomistic systems,19 the GNNs are trained to denoise atomic environments added to known amorphous structures (Fig. 1a, b, Methods). Later, trained models are used to sample new amorphous configurations from random distributions of atoms (Fig. 1a, c). Generated amorphous structures recover short- and medium-range order, create distributions of outputs nearly indistinguishable from simulated structures, exhibit elastic and plastic behaviors compatible with their simulated counterparts, and can be conditioned on processing parameters, such as cooling rates (Fig. 1d). The methods are demonstrated with applications on amorphous silica (a-SiO2), one simulated metallic glass, and one experimentally determined amorphous nanoparticle. The capabilities are used to generate large simulation cells, create processing-property relationships, produce porous structures, and augment experimental characterization data with synthetic results, enabling computational studies previously expensive or impractical (Fig. 1e). These results provide a step toward the inverse design of amorphous materials and an efficient tool for sampling their vast configurational space.

a Forward diffusion and reverse denoising process for amorphous materials. The structure and partial pair distribution functions (PDF) for SiO2 are provided as an example. In the forward process, noise is progressively added to atomic positions until the structure becomes random. In the reverse (generative) direction, the model gradually denoises the positions of randomly sampled positions and creates physically meaningful amorphous structures. b The denoiser model is trained to predict the displacement added to the amorphous structures. Displacements ϵ are sampled from Gaussian distributions, and added at train time to the training structures. Structure-level labels, such as cooling rates are embedded to the training set with a Gaussian basis set. c To generate new structures, the model is provided with a random input structure and a target cooling rate. The structure is denoised over multiple time steps following a noise schedule similar to the denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) framework3. d Figures of merit used to validate generated amorphous structures include short range order, medium range order, network connectivity, mechanical properties, and information entropy. e In this work, the generative models for amorphous materials were used across multiple applications, including generating glassy structures conditioned to very slow cooling rate, large scales, pores, or reproducing the phase space of simulated and experimental metallic glasses.

Results

Generating valid and novel amorphous materials

As a first case study, we trained a GNN-based diffusion model to generate a-SiO2 structures sampled with MD simulations at a constant cooling rate of 1 K/ps (Methods). Then, we verified whether generated structures displayed the correct short- and medium-range order for these materials. Fig. 2 shows that generated structures exhibited excellent structural agreement with their simulated counterparts adopted as ground-truth. Generated structures captured the short-range order characteristics of a-SiO2, with partial PDFs and bond angle distributions (BADs) reproducing peak positions and intensities of the reference data (Fig. 2a). At the medium range, Fig. 2c shows that generated structures reproduced ring distributions (Methods) with excellent accuracy, and only slightly overestimated the number of 6-membered rings. Beyond structural distributions, which can average out outliers, macroscopic quantities, such as mechanical properties are highly sensitive to unphysical environments, as they often lead to large variations in energy (see Supplementary Text, Section S1.2 and Tab. S1). Thus, reproducing properties is a rigorous test to validate generative models, but have been largely underutilized within amorphous materials. To enable this test, we calculated the stiffness tensor of simulated and generated structures according to the ground-truth potential used to produce the training data (see Methods for details). Fig. 2d shows that the elastic properties computed for the generated silica structures, including bulk modulus (K), shear modulus (G), Young’s modulus (E), and Poisson’s ratio (ν), are statistically indistinguishable from their simulated counterparts. In contrast with methods, such as reverse Monte Carlo, where structural features are well-reproduced but properties can be severely wrong20,21, our models produced structures in excellent agreement with reference simulation data across all relevant figures of merit.

a Comparison between the partial pair distribution functions (PDFs) of simulated (solid lines) and generated (dashed lines) shows that generated structures are quite similar to simulated ones. This close agreement is also seen in other structural metrics, including b distributions of Si-O-Si and O-Si-O bond angles and c ring size distributions. In (c), the error bar is the standard deviation of across six simulated or generated samples. d Elastic properties of generated structures are indistinguishable from the simulated ones. The properties computed here include the bulk modulus (K), shear modulus (G), Young’s modulus (E), and Poisson’s ratio (ν). e Generated structures follow the expected distribution of amorphous environments, as quantified by an information-theoretical strategy.22 The overlap between generated (Gen) and simulated (Sim) distributions of environments (black) is nearly equal to the overlap between simulated and simulated (blue) distributions. In (d and e), the thicker line, box, and whiskers depict the median, interquartile range, and range of the distribution, respectively. f Structures generated without a large external noise schedule cannot reproduce the information content of the reference structures, instead leading to structures with a high number of outlier environments (high entropy). On the other hand, a denoising process that includes an external noise schedule is able to generate more realistic structures.

As generative models learn a distribution of input data points, they are not only assessed according to the validity of samples, but also according to their novelty, thus verifying whether the model exhibits “mode collapse”2. However, in contrast to crystalline structures or molecular graphs, novelty is challenging to define in the amorphous space (see Sec. S1.3 in the Supplementary Text for a complete discussion). We computed a probability distribution over environments for amorphous structures following an information-theoretical strategy,22 and quantified the overlap between distributions. This comparison between distributions resembles the Fréchet Inception Distance23, which accounts for novelty in terms of distribution statistics rather than point-wise metrics. Fig. 2e shows that the distribution of overlap scores between different structure pairs is nearly identical (see detailed scores in Fig. S11). Generated structures exhibited as much overlap with simulated structures as the overlap between two simulated structures, ruling out the existence of mode collapse across the system when a large external noise is used to generate structures. On the other hand, Fig. 2f shows that the information entropy of generated samples is unreasonably large if no external noise is used during the denoising process (see Supplementary Text, Sec. S1.4, and Figs. S2–S5). These results demonstrate that our diffusion model generates valid structures according to structural features12,17,18 and property distributions, as well as novel structures, as quantified by their sampling distributions.

Generating amorphous structures conditioned on processing parameters

Controlling processing conditions, such as cooling rates in glassy materials is essential to model and design amorphous structures and their resulting properties24,25,26. Given the cost of performing long MD simulations, cooling rates in computational models typically revolve around 1012 K/s (or 1 K/ps), exceeding typical experimental cooling rates (1–100 K/s) by several orders of magnitude. Thus, learning to sample structures at very low cooling rates can unlock the ability to produce increasingly realistic models for amorphous systems. We trained our generative model on a-SiO2 structures simulated with cooling rates between 10−1 and 102 K/ps (Methods), then used an input to the GNN that conditioned the generation of amorphous structures to a target cooling rate (Fig. 1c). Fig. 3a demonstrates that structures generated with higher cooling rate targets exhibited higher information entropy even at constant density, reproducing known relationships between configurational entropy and cooling rates in glasses (see Sec. S1.5 and Fig. S6).27 Moreover, Fig. 3b shows that the dependence of average Si-O-Si angles with respect to the thermal history are reasonably captured in the generated a-SiO2 structures, in agreement with simulated counterparts and the literature.24,25,26 Beyond structural features, Fig. 3c shows the Young’s modulus (E) for simulated and generated a-SiO2 structures across different cooling rates. The values of Young’s moduli remain consistent across cooling rates for both simulated and generated a-SiO2 structures, ranging between 85–100 GPa. This agreement is also true for all other elastic properties, including bulk modulus, shear modulus, and Poisson’s ratio (Figs. S7–S10), confirming our ability to conditionally generate structures across cooling rates while reproducing their property distributions (see Sec. S1.6 in the Supplementary Text for an extended analysis).

a The diffusion models capture the correct trends in information entropy for amorphous structures generated under different cooling rates and densities. Faster rates often lead to structures with more outlier environments and thus higher information entropy. b Trends in bond angle distributions are reasonably captured when a single diffusion model is used to generate structures across different cooling rates. The models continue to exhibit the correct trends even in regimes outside of the training domain (10−2 and 103 K/ps) c Young’s modulus (E) of generated a-SiO2 structures across different cooling rates. The moduli are highly sensitive to outliers, yet the denoiser is able to generate structures with accurate Young’s modulus compared to simulations. In (b and c), the horizontal line, box, and whiskers depict the median, interquartile range, and range of the distribution, respectively. The single data point in b (10−2 K/ps) represents an outlier, which is away from the median by at least 1.5 times the interquartile range. d The computational cost (in GPU-h) of simulating a-SiO2 within the melt-quench process drastically increases with lower cooling rate, whereas the generative model has constant inference time. At very low cooling rates (10−2 K/ps), the difference in computational wall time can reach three orders of magnitude.

Remarkably, the trends in Fig. 3b, c generalize to both faster (103 K/ps) and slower (10−2 K/ps) cooling rates beyond the training regime (see Fig. S11 for more examples), which can be used to generate structures at low cooling rates that are expensive for traditional simulations. To illustrate the impact of this observation, Fig. 3d compares the estimated computational cost (in GPU-h) for simulating amorphous structures with 3000 atoms across cooling rates compared to the time required to evaluate the generative model (see Methods for hardware details). As slow cooling rates can only be simulated by longer MD simulations, the computational cost of simulating realistic glasses follows a power law with the cooling rate, while the generative model produces structures at constant time. At slow cooling rates, such as 0.01 K/ps, the diffusion model produces a-SiO2 structures at least 2400 times faster (in GPU-h) than MD simulations (Fig. 3d) for a system with 3000 atoms using the Jakse potential28. Performing melt-quench simulations for the largest system in this work (112,848 atoms) at 0.01 K/ps would require about 34,746 GPU-h using MD in our hardware (Methods), a substantial investment of computational resources. The generative process drastically improves the effectiveness of sampling amorphous structures at low cooling rates and large sizes, demonstrating that the correct processing-structure-property relationships can be captured with the model.

Fracture tests with large and slow-cooled amorphous silica

As our generative model samples structures for any input size or shape and for a range of cooling rates, we investigated the fracture behavior of generated a-SiO2 structures for different length scales and processing conditions. Experimental observations have shown that a-SiO2 exhibited a brittle-to-ductile transition at the nanoscopic regime29,30 while computational studies were typically limited by small sizes and fast cooling rates.24,25,31 We used our diffusion model to generate a-SiO2 with different sizes and cooling rates, and performed fracture test simulations for each of them (Methods). Fig. 4a shows the stress-strain curves obtained for a-SiO2 structures generated with a fixed aspect ratio of Lz/Lx = 1.4, as z being the direction of the tensile strain, and Lx varying from 3.5 nm (3735 atoms) to 10.9 nm (112,848 atoms). Generated structures reproduced the increasingly brittle behavior of amorphous silica at large length scales, while smaller simulation lengths (Lx < 6 nm) were more ductile (Supplementary Text, Sec. S1.7). The influence of low cooling rate effects on fracture, however, is often not studied at large length scales due to its associated computational cost25,32. On the other hand, our generative model allows sampling these large, slow-cooled structures at minimal computational cost. Fig. 4b compares the behavior of slow- and fast-cooled structures for a-SiO2 structures generated at large sizes (Lz/Lx = 1.4, Lx = 9.4 nm) and different target cooling rates. The results show that lower cooling rates decreased the ductility of the amorphous material,33 but up to a certain limit. The fracture strain for samples generated with cooling rates of 0.1 and 0.01 K/ps are nearly identical even though the structures are slightly different (Fig. 3b), showing how the fracture behavior converges at very low cooling rates. This contrasts with the continuous trend observed in simulated glasses at much smaller system sizes of 3000 atoms, for which the ductility was drastically overestimated and continued to decrease at low cooling rates (Figs. S12, S13).

a Stress-strain curves show that generated a-SiO2 structures recover the right behavior of elastic and plastic deformation behavior across length scales, with more ductile fracture at smaller length scales while maintaining a constant ultimate tensile strength at fixed aspect ratio (Lz/Lx = 1.4). b Stress-strain curves from generated a-SiO2 structures of the same shape and size (Lz/Lx = 1.4, Lx = 9.4 nm) under conditional cooling rates show that slower cooling rate leads to a more brittle behavior for amorphous silica. c The model successfully generates mesoporous a-SiO2 structures despite not being trained on surfaces or porous structures. Partial pair distribution functions (PDFs) indicate that the structure remains amorphous despite the presence of surfaces and pores. Interestingly, the pore surface reproduces the experimental concentrations of non-bridging oxygens, holding promise to modeling silanol defects and other interfacial behavior of amorphous mesoporous silica.

Generating mesoporous amorphous structures

Mesoporous silica particles exhibiting pores with diameters between 2–50 nanometers are ubiquitous in many applications ranging from catalysis and separation to drug delivery34,35. Despite their wide use in experiments, computational sampling of mesoporous silica structures remains challenging. Traditional melt-quench methods fail to preserve hollow porous architectures, requiring a “pore drilling" approach that often produces incorrect surface configurations.36 Moreover, accurately representing surface silanol groups, which are critical for many applications, requires simultaneously maintaining structural stability while correctly terminating Si-O bonds at pore surfaces36,37. We used our generative approach to produce a porous a-SiO2 structure by denoising a structure from atoms sampled in a hexagonal lattice with a cylindrical pore (Methods, Fig. 4c). Despite never been trained on surfaces or porous structures, our diffusion model generated excellent amorphous surfaces and a wall that exhibited the right short-range ordering. Interestingly, generated porous structures correctly captured the atomic structure at the pore surface, comprised mostly of pristine SiO4 tetrahedra and non-bridging oxygens (NBO). The concentrations of NBOs were also in agreement with typical ranges of 2-4 NBOs/nm2 from experimental data38,39, and were a function of the initial wall density used as starting configuration for the denoiser. At higher densities, the pore tended to shrink and form more densed NBOs at the pore wall, while low-density walls tended to form less NBOs at the surface (Fig. S14). As NBOs are responsible for a variety of properties of mesoporous silica in the presence of hydrogen, such as catalytic or hydrophobicity, obtaining these substructures directly from the generative approach can drastically accelerate computational modeling in these fields.

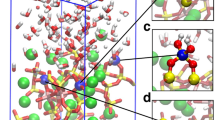

Generating metallic glasses

To extend our generative approach beyond a-SiO2, we tested our methodology against Cu-Zr metallic glass structures and properties, a non-covalent amorphous system with a challenging potential energy surface. Amorphous Cu-Zr structures with a fixed composition of Cu50Zr50 and 5000 atoms were obtained from ref. 40 to train a diffusion model without conditional targets. Then, given a box with randomly sampled atoms at a chosen composition and density, we used the diffusion model to generate the structure of the metallic glass, which can be followed by a short, post-denoising MD equilibration (Methods). Figure 5a shows that the partial PDFs between simulated and generated Cu50Zr50 glasses are in excellent agreement with each other, with generated structures showing near-perfect peak positions and only slightly lower intensities compared to the reference structures. This is true even for long-range peaks around 7 and 9 Å, which were outside of the cutoff of the GNN (5 Å), but were treated indirectly by the message-passing layers. The atomic volume in Fig. 5b and fractions of Voronoi indices in Fig. 5c for simulated and generated Cu50Zr50 also show good agreement with each other and only underestimated 〈0, 0, 12, 0〉 icosahedral motifs in generated samples. Given the sensitivity of Voronoi polyhedra to the structural fidelity, the ability of the model to correctly recover these trends is remarkable. Furthermore, Fig. 5d shows that the elastic and plastic regimes of the generated amorphous Cu-Zr structures (six independent samples) are also compatible with the reference curves (two samples). Though the yield stress is slightly underestimated in the generated structures, mirroring the results in Fig. S13, the strength curves of both metallic glasses are within good agreement with each other, especially when considering the sensitivity of stress-strain curves from these metallic glasses depending on the sample preparation41 and the limited training data used for the denoiser model. This proves that the generative model is not limited to amorphous silica networks, but can also produce valid amorphous structures and properties for metallic glassy systems.

a Partial pair distribution functions (PDFs) g(r) of generated Cu50Zr50 structures (red lines) exhibit good agreement with PDFs of their simulated counterparts (blue lines), including capturing the shorter Cu-Cu pair interactions compared to Cu-Zr and Zr-Zr pairs. b Distributions of atomic volume exhibit great agreement between the coordinations and local environments of generated Cu50Zr50 structures (red) and their simulated, ground-truth counterparts (blue). c Generated Cu50Zr50 structures reproduce the fractions of major Voronoi polyhedra compared to their simulated counterparts, only under-representing 〈0, 0, 12, 0〉. Error bars for indices indicate the range of the distribution. d Stress-strain behavior of generated Cu50Zr50 structures (red, five samples) approach the ones from their simulated Cu50Zr50 counterparts (blue, 2 samples), with equivalent Young’s modulus and strength, despite slightly underestimated yield strength. e Beyond simulation data, the generative diffusion model can be trained on experimental data, such as the atomistic structure characterized by Yang et al.42 and generate synthetic counterparts to the experimental results. f Generated atomic structure using experimental data shows good agreement on polyhedral face fractions (red) compared to results from the experimental atomic model (blue). g Total PDFs and h partial PDFs show that generated structures correctly capture the pair interactions from the experimental three-component metallic glass, including the anomalous peak positions and intensities for the 3-3 pairs.

Augmenting experimental characterization data on amorphous structures

Given that characterization data on amorphous structures is challenging to obtain at high resolutions, generative models can be used to augment experimental datasets with realistic, synthetically generated data. We trained our model on the atomistic structure of a multi-component metallic glass from Yang et al.42 obtained using atomic electron tomography (AET) (Fig. 5e). The data contained a finite metallic glass nanoparticle with three different element classes denoted as types 1, 2, and 3. Generated structures reproduced the distribution of polyhedral faces (Fig. 5f) and Voronoi indices distribution (see Supplementary Text, Sec. S1.8 and Tab. S2) from the experimental data, indicating that the model captured the correct geometrical distribution of the data. Furthermore, Fig. 5g, h show that the diffusion model approximated the total PDF of the experimental data at realistic levels despite being trained on a single example of experimental structure. Discrepancies between the two PDFs in Fig. 5g, especially at longer ranges, are due to the mismatch between the radial data computed for a finite particle in the experimental data and the generated bulk structure represented with periodic boundary conditions. Nevertheless, the generated structure reproduced the experimental behavior observed in the medium-range, where certain substructures were shown to form crystal-like “superclusters” that created medium-range order for specific atom pairs, and atypical PDFs for specific atom pairs42. Fig. 5h illustrates that the model correctly captured the correct short-range ordering and pairwise distributions in the experimental data (see Fig. S15 for all partial PDFs). In typical pair distribution functions, such as that for 1–3 pairs in Fig. 5h, generated structures exhibited the right peak positions and their relative intensities of the PDF, including medium-range features between 5–6 Å. Remarkably, even for atypical partial PDFs, such as the ones for 3–3 pairs in the experimental data, the model captured the correct distribution of atomistic species, as demonstrated by the agreement in peak positions around 2.9, 3.8, and 4.8 Å, with the third peak being the most prominent one. At medium-range, the model also captured the shoulder in the PDF between 5.5–6.5 Å, and the longer-range peak around 7.3 Å. This shows that the generative model can quantitatively reproduce experimental datasets and can be used to produce synthetically generated structures that mimic the experimental results at arbitrary sizes and shapes, or assist in the development of atomistic models for structural characterization.

Discussion

Our generative diffusion model substantially advances computational modeling of amorphous materials, accurately producing physically realistic structures and properties across various compositions, data sources, and processing conditions. Unlike previous generative methods for amorphous materials, whose unphysical artifacts or constrained structural diversity limited their broad use in simulations, our model consistently replicates key short- and medium-range structural characteristics and mechanical properties, highlighting its robustness and reliability. Importantly, this framework offers efficient computational performance, drastically reducing the computational cost typically associated with MD simulations. Our work provides a roadmap not only for the training process of diffusion models for amorphous materials, but also how to quantitatively assess model quality in terms of structural novelty, properties, and applications.

As with any model, our approach exhibits limitations. Occasional outlier environments, although rare, require short MD simulations to refine the generated structure. Furthermore, though several properties are predicted with high accuracy, yield strengths are still slightly underestimated, showing this metric may be a good indicator of model quality within generative models for amorphous structures as the field progresses. Future research can extend this approach toward broader classes of complex materials, including metallic or semiconducting alloys or polymers. Additionally, integrating generative methods with experimental characterization can automate structural elucidation, particularly in fields where experimental data is scarce or costly to obtain. The adaptability and diversity of applications demonstrated here suggest that generative diffusion models can already be used in a range of computational materials science problems, accelerating their modeling and discovery.

Methods

Score-based denoiser for amorphous structures

To create a generative model for amorphous structures, we adapted the denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPM) approach to amorphous materials by learning a mapping between a random distribution of atoms and a physically meaningful amorphous structure using a GNN3,19. Figure 1a exemplifies the training and generative denoising processes for amorphous SiO2 (a-SiO2), with their partial pair distribution functions (PDFs) illustrating how short- and medium-range order varies across the system. The forward diffusion process (left to right in Fig. 1a) gradually introduces Gaussian noise to atomic positions from simulated amorphous structures until the final structure resembles a random distribution of particles. After training, the model is used to generate amorphous structures from randomly sampled particles with the denoising process (Fig. 1a, right to left). Given a target cooling rate and an initial configuration with fixed density and shape, the model sequentially denoises the configuration in a process that resembles “Langevin dynamics” with a learned score. This process adds an extra noise at each denoising step, which acts as an effective “temperature” for the system and escaping local minima in the learned score function (see Sec. S1.4 in the Supplementary Text). Within the DDPM, this extra noise follows a schedule and becomes progressively smaller throughout the denoising process3.

Mathematically, a generative model approximates the distribution p(x) over atomic structures x of the material system of interest. Under this DDPM strategy for atomistic structures, we train a model to approximate the distribution of atomic environments of amorphous configurations p(x) inferred from a dataset of known configurations. This approximation of p(x) is first performed by considering an input structure x0 and defining a Markov chain process such that

where T is the number of diffusion steps. This forward process is defined by a distribution q(xt∣xt−1), 1≤t≤T. For simplicity, the distribution q is often chosen as a Gaussian distribution, where

with (μt, σt) functions of the denoising timestep t and \({\mathbb{I}}\) the identity matrix. Within the diffusion model framework, given that the ground-truth distribution p is often intractable, a model pθ with parameters θ is trained to approximate, at each step t, the score function of the noise distribution q(xt∣xt−1),43

Within this notation, pθ(xt, t) is called the score model, and the expectation \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{{\bf{x}}}_{0} \sim {\mathcal{D}}}\) is performed over the dataset \({\mathcal{D}}\) of initial (training) structures x0.

When the distribution q is chosen to be Gaussian with μt = 0 and we define xt = xt−1 + σtϵ, \({\boldsymbol{\epsilon }} \sim {\mathcal{N}}({\bf{0}},{\mathbb{I}})\), its score can be written directly as

which defines a per-atom displacement εt that maps the noisy atomic positions xt to its previous, denoised state xt−1.3 By redefining the model pθ(xt, t) as ϵθ(xt, t) = − σtpθ(xt, t) and adopting a denoising score-matching loss,44 which simplifies the objective function of Eq. (3) to

Equation (5) indicates that a model ϵθ is given an input structure xt and is trained to predict the noise ϵ that maps from the denoised state xt−1 into xt given a noise schedule σt.

Model architecture and training

Following previous approaches19, the denoiser model uses a customized version of the E(3)-equivariant NequIP model45 to implement the training from in Eq. (5). The model utilizes an initial embedding layer that maps atomic species information onto an 8-dimensional scalar feature space (8 × 0e) for both node attributes and atomic numbers, with interactions truncated at the specified cutoff radius (5 Å). The network architecture consists of three convolution layers (num_convs = 3) within the message-passing framework. Hidden layer representations are configured as 64 scalar features and 32 vector (rotation-equivariant) features. Edge features are represented with 4 × 0e + 4 × 1o + 2 × 2e features encoding scalar, vector, and rank-2 tensor components. The radial basis functions are parameterized through a two-layer neural network with 16 and 64 neurons, respectively, to model distance-dependent interactions. The model considers up to 12 nearest neighbors per atom (num_neighbors = 12) and produces vector outputs, ensuring that the predicted noises are equivariant under rotations and translations while maintaining the fundamental symmetries of the physical system.

To incorporate cooling rate information into the model architecture, we implemented a Gaussian basis embedding module, which maps a scalar cooling rate value into a high-dimensional feature vector. Specifically, we project each cooling rate onto a set of 9 Gaussian basis functions with means distributed uniformly across the normalized cooling rate range in a \({\log }_{10}\) scale, thus mapping the interval of cooling rates from [10−2, 103] K/ps to [−2, 3]. Each basis function’s activation represents the similarity between the input cooling rate and that basis function’s mean value, effectively creating a smoothly varying representation. These activations are then processed through a two-layer neural network with a SoftPlus nonlinearity, producing a dense embedding vector that captures the cooling rate’s influence on structural properties. This embedding is summed to the hidden representation at each convolution layer of the GNN.

The model was trained on a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. The per-coordinate, per-atom noise perturbation ϵ was added at train time and sampled from a normal distribution \({\mathcal{N}}(0,\sigma^2 )\), where σ ranged from 0.001 to 0.75 Å based on the noise schedule. At train time, the schedule t is sampled from a uniform distribution, where 1 ≤ t ≤ T. Maximum displacement parameters were calibrated to approximately 50% of typical bond lengths, ensuring that the diffusion process leads to fully random or highly noised configurations. Cooling rates associated with individual training configurations were embedded using a Gaussian basis set, as details described in the above section. The conditional denoiser model was trained for 40,000 iterations with a batch size of 16 and learning rate of 2 × 10−4, with validation loss monitored to assess convergence. For unconditional denoiser models (CuZr and experimental nanoparticle systems), the number of training iterations was 20,000.

Inference and generative denoising process

The number of atoms and lattice parameters were selected as inputs based on desired density, lattice shape, and atom types. All atoms were initially sampled from a uniform distribution within the simulation cell, meaning each of their fractional coordinates (fx, fy, fz) was sampled from \({\mathcal{U}}(0,1)\). The denoiser model was applied to generate atomic structures from these initialized configurations with extra noise (Fig. 1c). The per-atom, per-coordinate extra noise is sampled from a normal distribution \({\mathcal{N}}(0,{\sigma }_{t}^2)\) with mean 0 and standard deviation σt represents the noise magnitude following a noise schedule dependent on the denoising step t. The noise magnitude was decreased linearly to zero over the extent of 2900 generation steps. Thus, each initial configuration underwent 2900 denoising steps with extra noise (with σt=0 = 1.0) followed by 100 denoising steps without extra noise. Despite being denoised from the same initial structure, adding “large” initial extra noise and using different random seeds ensures that generated structures are different from each other.

Generated configurations were subsequently refined using MD simulations consisting of 25 ps in the NVT ensemble followed by 25 ps in the NPT ensemble using the potential and settings for MD described below. This last-step MD refinement was performed for a-SiO2 and Cu50Zr50 systems but was omitted for structures used to reproduce experimental data.

For conditional denoising based on different cooling rates, simulation boxes are kept constant during the denoising process, but the cooling rate is known to influence the density. To account for this fact, we extracted densities from simulated structures across different cooling rates and identified a reasonably linear correlation between a-SiO2 density and the logarithm of the cooling rate (see Fig. S16 and Supplementary Text, Sec. S1.6) within the ranges of interest24,25. Thus, when selecting the targeted cooling rate, we fix the density of the initial, randomly sampled configuration using a linear regression model valid within the range of cooling rates of interest. Future work can focus on sampling amorphous structures with variable densities throughout the denoising process.

To create an amorphous a-SiO2 structure, we performed the denoising process described above with a different initial condition, where atoms were sampled according to a non-uniform distribution throughout the lattice. Atoms were sampled from a random distribution over a hexagonal lattice with predefined wall density, number of atoms, and lattice length. However, an excluded volume in the shape of a cylinder prevented atoms from being sampled within the “pore”, thus mimicking a uniform atomic distribution of atoms for all regions outside the pore (Fig. 4c). Then, the porous structure was denoised following the exact same procedure described above, with a target cooling rate of 1 K/ps.

MD simulations

All MD simulations were performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) software46 (v. 17 Apr 2024). A fixed integration timestep of 1.0 fs was used throughout all simulations.

To generate training data for the SiO2 systems, we conducted MD simulations of amorphous silica comprised of 3000 atoms across multiple cooling rates. We executed six independent simulations at each cooling rate, maintaining the same settings while varying initial configurations. We adopt the Jakse interatomic potential28, parametrized from ab initio calculations, to model a-SiO2. Short-range interactions are calculated with an 8.0 Å cutoff. Coulomb interactions are calculated by adopting the Fennell damped shifted force model with a damping parameter of 0.25 Å−1 and a global cutoff of 8.0 Å. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions during MD simulations.

All a-SiO2 samples were prepared via conventional melt-quench method. Initial structures were generated by randomly placing SiO2 molecules in cubic boxes using PACKMOL (v. 20.13.0)47, enforcing a 2.0 Å minimum separation between molecules to prevent unphysical overlaps. Following energy minimization, configurations underwent sequential 50 ps relaxations in the canonical (NVT) and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles at 300 K. Complete melting was achieved with a 50 ps-long NPT equilibration at 5000 K and zero pressure, eliminating the “memory” of the initial configuration. Subsequently, liquid systems were cooled from 5000 to 300 K under zero pressure NPT conditions at rates of 10−1, 100, 101, and 102 K/ps. The obtained glass structures are further relaxed one last time at 300 K for 100 ps in the NPT ensemble. This process follows the standards from previous work26 shown to reproduce multiple experimental features from a-SiO2 glasses.

We adopted the published dataset from Wang et al.40, which used a set of optimized embedded-atom method (EAM) potentials to simulate CuZr metallic glass models48. Specifically, we used two of their Cu50Zr50 configurations, each containing 5000 atoms, to train our denoiser model. The potential from Cheng et al.48 was later used to perform the short MD refinement and the fracture test (described below) for generated CuZr structures. The post-denoising MD simulation was 25 ps-long at the NVT ensemble, followed by a 25 ps-long simulation at the NPT ensemble, both at 300 K.

Computation of elastic properties and fracture test

The stiffness tensor Cij of the equilibrated glasses is computed by performing a series of six deformations (i.e., three axial and three shear deformations along the three axes) and calculating the curvature of the potential energy U:

where V is the glass volume, e is the strain, and i, j are the indices corresponding to each Cartesian direction. All simulated configurations exhibited near-complete isotropy. Bulk modulus (K), shear modulus (G), Young’s modulus (E), and Poisson’s ratio (ν) are then calculated from the stiffness tensors.

Fracture simulations are performed on different starting bulk configurations by deforming the structures along a single direction during an MD simulation. Uniaxial deformation is achieved by imposing a constant strain rate of 109 s−1 along the z direction while allowing lateral dimensions (x and y) to relax freely under zero lateral pressure, approximating realistic uniaxial tension conditions. The deformation process is controlled using an NPT ensemble maintained at 300 K and 1 bar. True stress is calculated from the negative z-component of the stress tensor.

Computational cost estimates

We used a single NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU to compare the computational cost of MD simulations and denoiser inference for an a-SiO2 system of 3000 atoms, as shown in Fig. 3d. The entire MD simulation process includes initialization, melting, cooling and relaxation parts as detailed above, where only the cooling part is affected by the choice of cooling rate. Note that, the choice of potential, simulation size, and other aspects can affect the computational time for MD simulation. The LAMMPS package was compiled with Kokkos to perform the GPU-accelerated simulations49. The denoising process (inference) consists of a total of 3000 denoising steps (2900 steps with extra noise and 100 steps without extra noise).

To estimate the computational cost of traditional melt-quench MD simulations for large systems at slow cooling rates, we benchmarked structures at target sizes for 25 ps. All simulations include fixed computational overhead include 50 ps NVT initialization, 50 ps NPT initialization, 50 ps NPT melting, and 100 ps NPT relaxation (250 ps total). The quenching process duration varies with cooling rate, requiring 47, 470, 4,700, 47,000 and 470,000 ps for 102, 101, 100, 10−1, and 10−2 K/ps, respectively. Total computational cost is calculated by multiplying the average time per step obtained for a 10 ps MD simulation by the total number of steps to perform the simulation. For the large system estimate, the cost of performing a 10 ps MD simulation of 112,848 atoms within a-SiO2 and the simulation settings described above is 0.74 GPU-h. This results on the total estimated cost of 34,746 GPU-h for the same size under 0.01 K/ps cooling rate described in the main text.

We also used a single CPU core of Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2650 v4 @ 2.20 GHz from UCLA’s Hoffman2 Cluster to estimate the computational cost of MD simulation and denoiser generation on CPU. The simulate and generation process are the same as described above, and the results are shown in Fig. S17.

Analysis of amorphous structures

All structural features of simulated a-SiO2 structures were performed with six independent samples of 3000 atoms each. Samples are obtained either through the traditional melt-quench process, or using the generative models. All structural properties reported in the main text (e.g., Figs. 2, 3) are reported as either averages over these six samples (e.g., structural features in Fig. 2a–c) or distributions (e.g., mechanical properties in Fig. 2d). This allows us to perform statistically relevant comparisons between generated and simulated structures by accounting for the distribution of structures and properties in amorphous materials.

Short-range structural ordering was characterized through pair distribution function (PDF) analysis. All PDFs were calculated using OVITO50 with 100 bins between 0 and 8 Å. The medium-range order structure of amorphous silica was characterized through ring size distribution analysis. These calculations were performed using the RINGS package,51 with Si-O bonds defined using a 2.0 Å cutoff distance for ring identification within the network structure, which is in agreement with the partial PDF for Si-O pairs in Fig. 2a.

We quantified the concentration of non-bridging oxygens (NBOs) on generated mesoporous silica surfaces by calculating the ratio of NBO atoms to the estimated surface area of the pore. As described in the main text, the pore morphology exhibits density-dependent shape and distortions from ideal cylindrical structures, as illustrated in Fig. S14. To address this non-ideal geometry, we analyzed the radial distribution of Si and O atoms relative to the central simulation axis. The effective pore radius was estimated as the distance at which the density of Si and O atoms plateaus, indicating the boundary between pore space and silica framework. Whereas our generation has been performed only for the SiO2 composition, NBOs are of high relevance to applications of mesoporous silica, where they can become silanol groups in the presence of hydrogen.

We employed Voronoi analysis in OVITO50 to compute the atomic volumes of CuZr structures. Particle radii of 1.35 Å for Cu and 1.55 Å for Zr atoms are applied for analysis, with relative face area threshold set to 1%. Voronoi indices for CuZr structures were also computed using OVITO using the same particle radii. For Voronoi indices, surface atoms occupying less than 1% of the total surface area were excluded to minimize effect from experimental measurement and structural reconstruction errors. Voronoi indices are represented using reduced Schlaefli notation, 〈n3, n4, n5, n6〉, where ni denotes the number of polyhedral faces containing i edges. The polyhedral face distribution quantifies the frequency of faces with varying edge numbers. We adopted the analysis functions published by Yang et al.42 to analyze Voronoi tessellation of atomic structures for both experimental and generated nanoparticles for consistency with that work. Surface atoms occupying less than 1% of the total surface area were excluded to minimize effect from experimental measurement and structural reconstruction errors.

Information entropy and QUESTS method

The representation of atomic environments was computed as described in our previous work22. In summary, a number of k = 32 neighbors was used to represent the atomic environment, with a cutoff of 5 Å. No distinction was made between element types, which is implicitly recovered based on the coordination environments, and thus captured in the information entropy of the system.

The information entropy of descriptor distributions was computed as described before.22 Given a set of feature vectors {X}, their information entropy is computed as follows:

where our choice of the kernel Kh is the Gaussian kernel,

with a constant bandwidth h = 0.015 Å−1, as studied before.22

We define the differential entropy \(\delta {\mathcal{H}}\) of a data point Y with respect to a reference dataset {X} as

Throughout this work, the natural logarithm was used for the entropy in Eq. (7), which scales the information to natural units (nats).

From the definition of \(\delta {\mathcal{H}}\), the overlap between two discrete distributions of atomic environments {Y} and {X} is the fraction of environments Yi ∈ {Y} with \(\delta {\mathcal{H}}({{\bf{Y}}}_{i}| \{{\bf{X}}\})\le 0\). Therefore, a zero overlap between two distributions indicates that the distributions have disjoint supports, whereas a 100% overlap indicates that the two distributions have the same support, even when the point-wise probabilities are different. Within the context of generative models described in the main text, a high overlap indicates that the generated structures follow the same distribution of atomic environments, while a low overlap suggests that the structures do not share the same environments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated in this work are available at https://github.com/digital-synthesis-lab/2025-dm2-data. The datasets of metallic glasses were obtained from the original source at: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Heterogeneous_thermal_activation_energy_in_Cu-Zr_metallic_glasses/12485795. The datasets of the experimental nanoparticle was obtained from the original source at: https://github.com/AET-MetallicGlass/Supplementary-Data-Codes.

Code availability

The code, trained models and demos for training and denoising are available at https://github.com/digital-synthesis-lab/DM2. This work was based on the code from Hsu et al.,19 available at https://github.com/LLNL/graphite. The code for computing Voronoi indices of amorphous nanoparticles was from Yang et al.,42 available at https://github.com/AET-MetallicGlass/Supplementary-Data-Codes. The information theoretical analysis was performed with the QUESTS package from Schwalbe-Koda et al.,22 available at https://github.com/dskoda/quests. A webpage demonstrating this work with interactive visualizations can be accessed at https://kaiyang1010.github.io/DM2/.

References

Zunger, A. Inverse design in search of materials with target functionalities. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 0121 (2018).

Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N. & Weinberger, K. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 27 (NIPS, 2014).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Diffusion models: A comprehensive survey of methods and applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 1–39 (2023).

Xie, T., Fu, X., Ganea, O.-E., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. S. Crystal diffusion variational autoencoder for periodic material generation. In International Conference on Learning Representationshttps://openreview.net/forum?id=03RLpj-tc_ (ICLR, 2022).

Zeni, C. et al. A generative model for inorganic materials design. Nature 639, 624–632 (2025).

Guo, G. et al. Ab initio structure solutions from nanocrystalline powder diffraction data via diffusion models. Nat. Mater.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02220-y (2025).

Zhong, P., Dai, X., Deng, B., Ceder, G. & Persson, K. A. Practical approaches for crystal structure predictions with inpainting generation and universal interatomic potentials. Mater. Horiz. 12, 9669−9678 (2025).

Schwalbe-Koda, D. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Generative models for automatic chemical design. In Machine Learning Meets Quantum Physics, 445–467 (Springer, 2020).

Liu, Y., Madanchi, A., Anker, A. S., Simine, L. & Deringer, V. L. The amorphous state as a frontier in computational materials design. Nat. Rev. Mater. 10, 228–241 (2024).

Urata, S., Bertani, M. & Pedone, A. Applications of machine-learning interatomic potentials for modeling ceramics, glass, and electrolytes: A review. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 107, 7665–7691 (2024).

Comin, M. & Lewis, L. J. Deep-learning approach to the structure of amorphous silicon. Phys. Rev. B 100, 094107 (2019).

Kilgour, M., Gastellu, N., Hui, D. Y., Bengio, Y. & Simine, L. Generating multiscale amorphous molecular structures using deep learning: a study in 2d. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 8532–8537 (2020).

Chen, Q., Annamareddy, A., Li, Y.-F., Morgan, D. & Wang, B. Physical regularized hierarchical generative model for metallic glass structural generation and energy prediction. arXiv:2505.09977 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Conditional generative modeling for amorphous multi-element materials. arXiv:2503.07043 (2025).

Xu, X. & Hu, J. A generative adversarial networks (GAN) based efficient sampling method for inverse design of metallic glasses. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 613, 122378 (2023).

Kwon, H. et al. Spectroscopy-guided discovery of three-dimensional structures of disordered materials with diffusion models. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 5, 045037 (2024).

Yong, A. X. B., Su, T. & Ertekin, E. Dismai-Bench: benchmarking and designing generative models using disordered materials and interfaces. Digit. Discov. 3, 1889–1909 (2024).

Hsu, T. et al. Score-based denoising for atomic structure identification. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 155 (2024).

McGreevy, R. L. Reverse monte carlo modelling. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 13, R877 (2001).

Maffettone, P. M. et al. When can we trust structural models derived from pair distribution function measurements? Faraday Discuss. 255, 311–324 (2025).

Schwalbe-Koda, D., Hamel, S., Sadigh, B., Zhou, F. & Lordi, V. Model-free estimation of completeness, uncertainties, and outliers in atomistic machine learning using information theory. Nat. Commun. 16, 4014 (2025).

Heusel, M., Ramsauer, H., Unterthiner, T., Nessler, B. & Hochreiter, S. GANs trained by a two time-scale update rule converge to a local nash equilibrium. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 6629–6640 (2017).

Vollmayr, K., Kob, W. & Binder, K. Cooling-rate effects in amorphous silica: a computer-simulation study. Phys. Rev. B 54, 15808 (1996).

Lane, J. M. D. Cooling rate and stress relaxation in silica melts and glasses via microsecond molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 92, 012320 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Cooling rate effects in sodium silicate glasses: bridging the gap between molecular dynamics simulations and experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 074501 (2017).

Berthier, L., Ozawa, M. & Scalliet, C. Configurational entropy of glass-forming liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 160902 (2019).

Bouhadja, M., Jakse, N. & Pasturel, A. Structural and dynamic properties of calcium aluminosilicate melts: a molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 224510 (2013).

Célarié, F. et al. Glass breaks like metal, but at the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 075504 (2003).

Luo, J. et al. Size-dependent brittle-to-ductile transition in silica glass nanofibers. Nano Lett. 16, 105–113 (2016).

Yuan, F. & Huang, L. Molecular dynamics simulation of amorphous silica under uniaxial tension: From bulk to nanowire. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 358, 3481–3487 (2012).

Zhang, Z., Ispas, S. & Kob, W. The critical role of the interaction potential and simulation protocol for the structural and mechanical properties of sodosilicate glasses. J. Non-Crystal. Solids 532, 119895 (2020).

Fan, M. et al. Effects of cooling rate on particle rearrangement statistics: rapidly cooled glasses are more ductile and less reversible. Phys. Rev. E 95, 022611 (2017).

Kresge, aC., Leonowicz, M. E., Roth, W. J., Vartuli, J. & Beck, J. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism. Nature 359, 710–712 (1992).

Tang, F., Li, L. & Chen, D. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, biocompatibility and drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 24, 1504–1534 (2012).

Calderon V, S., Ribeiro, T., Farinha, J. P. S., Baleizão, C. & Ferreira, P. J. On the structure of amorphous mesoporous silica nanoparticles by aberration-corrected STEM. Small 14, 1802180 (2018).

Fought, E. L. et al. Modeling of linear nanopores in a-SiO2 tuning pore surface structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 341, 112077 (2022).

Zhao, X. S., Lu, G., Whittaker, A., Millar, G. & Zhu, H. Comprehensive study of surface chemistry of MCM-41 using 29Si CP/MAS NMR, FTIR, pyridine-TPD, and TGA. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 6525–6531 (1997).

Kozlova, S. A. & Kirik, S. D. Post-synthetic activation of silanol covering in the mesostructured silicate materials MCM-41 and SBA-15. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 133, 124–133 (2010).

Wang, Q. et al. Predicting the propensity for thermally activated β events in metallic glasses via interpretable machine learning. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 194 (2020).

Nawano, A., Jin, W., Schroers, J., Shattuck, M. D. & O’Hern, C. S. Characterizing the mechanical response of metallic glasses to uniaxial tension using a spring network model. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 073605 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid. Nature 592, 60–64 (2021).

Hyvärinen, A. Estimation of non-normalized statistical models by score matching. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 6, 695–709 (2005).

Vincent, P. A connection between score matching and denoising autoencoders. Neural Comput. 23, 1661–1674 (2011).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comp. Phys. Comm. 271, 108171 (2022).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Cheng, Y., Ma, E. & Sheng, H. Atomic level structure in multicomponent bulk metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 245501 (2009).

Trott, C. R. et al. Kokkos 3: programming model extensions for the exascale era. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 33, 805–817 (2022).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010).

Le Roux, S. & Jund, P. Ring statistics analysis of topological networks: new approach and application to amorphous GeS2 and SiO2 systems. Comput. Mater. Sci. 49, 70–83 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Toyota Research Institute under the Synthesis Advanced Research Challenge. This work used computational and storage services associated with the Hoffman2 Shared Cluster provided by UCLA Office of Advanced Research Computing’s Research Technology Group. The authors thank Linda Hung, Amalie Trewartha, Steven Torrisi, Fei Zhou, Jiawei Guo, and Long Qi for discussions and suggestions regarding this work. The authors also thank Jianwei (John) Miao and his group for making the experimental dataset available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S.-K. conceived the research. K.Y. and D.S.-K. conducted the investigations, developed the methodology, and performed the formal analysis. K.Y. curated the data, developed the software, and validated the results. Both authors contributed to the visualizations and manuscript writing. D.S.-K. supervised the research and was responsible for funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, K., Schwalbe-Koda, D. A generative diffusion model for amorphous materials. npj Comput Mater 12, 29 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01901-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01901-1